6 Model of human occupation

The Model of Human Occupation, or MOHO (Kielhofner, 1985, 1995, 2002, 2008) as it is well known, is the longest published model in occupational therapy. It developed out of the occupational behaviour tradition at the University of Southern California, USA. At the time it was first published, the major occupational therapy models available in North America were the occupational performance models. As they primarily focused on physical rehabilitation, MOHO was unique in that it addressed issues relevant to other areas of practice such as mental health and intellectual disability through its detailed description of volition and habituation. Perhaps owing to its broad scope, MOHO was very influential in both these specific areas as well as more broadly.

Main concepts and definitions of terms

As the name suggests, the Model of Human Occupation was established to explore, organize and make explicit the concept of human occupation, which was considered the foundation of occupational therapy. The model has undergone substantial changes since its original publications in the early 1980s and many of these changes are detailed in the historical description section of this chapter. This section discusses the major concepts as they were presented in the fourth edition of the major text (Kielhofner, 2008).

In the fourth edition, Kielhofner (2008) stated, “The vision for MOHO has been to support practice throughout the world that is occupation-focussed, client-centred, evidence-based, and complementary to practice based on other occupational therapy models and interdisciplinary theories.” (p. 1.) In some ways the model is difficult to describe, because it has evolved substantially in its concepts, since the first edition of the text in 1985, whilst keeping its original structural components.

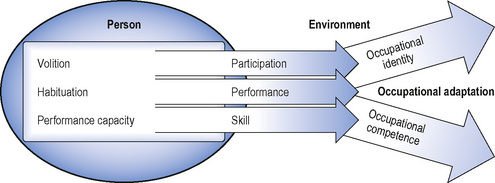

It is difficult to identify the overall purpose of MOHO in its current (and previous) edition as these latest writings have highlighted the model’s newest developments and changes, without necessarily making explicit the model’s purpose. However, to use the metaphor of the window through which one looks without making the process of looking out the window explicit, it may be that MOHO centres on the processes of occupational adaptation, without stating it overtly. The core concepts of the model were listed as “environmental impact, volition, habituation, performance capacity, participation, performance, skills, occupational identity, and occupational competence” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 145). Figure 6.1 shows how their relationships are organized, with all of the concepts leading to occupational adaptation. Therefore, occupational adaptation might be the overall focus of MOHO.

Figure 6.1 outlines how a person engages in human occupation within the context of the environment and this process results in occupational adaptation. Three concepts are considered to be internal to the person. These are volition, habituation and performance capacity and are concepts that have been associated with MOHO since its origins. Additionally, human occupation is conceptualized as having three dimensions. These are participation, performance and skill. When a person engages in occupation, it creates a change in occupational identity and occupational competence, both of which are conceptualized as the components of occupational adaptation. All of this occurs in the context of an environment that shapes and is shaped by all aspects of the process.

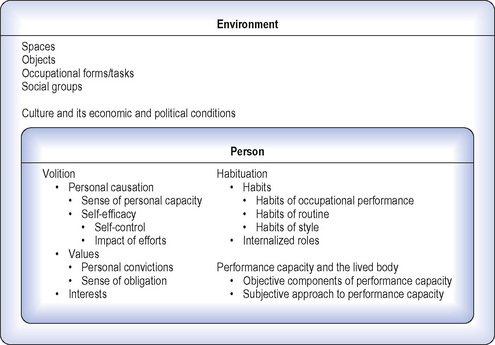

The first aspect of the model that we will describe is the original concepts associated with MOHO − volition, habituation, performance capacity and environment (Figure 6.2). Kielhofner (2008) stated that MOHO aims to provide a framework for conceptualizing how people “select, organize and undertake their occupations” (p. 12). An earlier version of the model described this aim as the parallel concern for how occupation is “motivated, patterned and performed” (Kielhofner, 2002, p. 13). The model attends to each of these aims through the concepts of volition, habituation and performance capacity, respectively. That is, volition explains why people select occupations, habituation outlines how they organize their occupations and performance capacity attends to the skills and abilities that enable them to perform their occupations. Human occupation is also conceptualized as existing within an environmental context that influences all aspects of occupation. These environments provide opportunities, as well as support, demand and constrain occupation. In discussing environment, the model details physical and social environments and uses the term occupational settings to refer to the overall context surrounding occupation.

Volition

The concept of volition is finely detailed in MOHO. This is one of the unique features of the model, as this level of detail about volition does not occur in any of the other models. The human need to act is presented as pervasive, intense and the basis for occupation. The model uses the term volition to refer to this impetus towards action. Kielhofner (2008) defined volition as “a pattern of thoughts and feelings about oneself as an actor in one’s world which occurs as one anticipates, chooses, experiences, and interprets what one does” (p. 16). MOHO presents volitional thoughts and feelings as including three components − personal causation, values and interests – and a volitional process that includes a cycle of anticipation, making choices, experience and interpretation. Each of the three components of volition is influenced by this volitional cycle, in which volition affects how people anticipate action, make choices about what action they will engage in, experience action and interpret or give meaning to their actions. Each of these components of volition also comprises other elements.

First, personal causation refers to “one’s sense of capacity and effectiveness” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 13). The term personal causation is used in the sense that people can experience themselves as being able to cause or make things happen, that is, to be able to act purposefully in the world and produce outcomes. Personal causation is conceptualized as comprising two elements, a sense of both personal capacity and self-efficacy. These refer respectively to people’s thoughts and feelings about what they are capable of and their sense of what kinds of outcomes they are able to control. It may be that people’s sense of personal capacity pertains to something that is within them (but affects how they operate within the world), whereas self-efficacy operates more overtly in their relationships with the world. While people can experience a sense of capacity, they can also encounter incapacity, which “is experienced as difficulty doing the things that matter in one’s life” (p. 37).

Self-efficacy requires both self-control and a sense of being able to bring about a desired outcome. It relates to specific spheres of life, in that people might feel they can control outcomes in some areas more than others (Kielhofner, 2008). Experiences contribute to the development of both personal capacity and self-efficacy in that people are more likely to persist or seek out opportunities in situations in which they feel capable or efficacious and to avoid situations that do not provide that kind of feedback or outcome. Often, the sudden or gradual loss of personal capacities leads to a reduced sense of self-efficacy, just as the contexts in which people conduct their lives can enhance or reduce their self-efficacy.

Second, MOHO presents values as contributing fundamentally to the volition for action. Values are the “beliefs and commitments” that people develop about “what is good, right, and important to do” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 39). The values that individuals hold are developed in relation to the broader culture in which they have grown up and live. Kielhofner suggested that, as values are developed from cultural norms, people develop a sense of belonging to the cultural group when acting in ways that are consistent with their values and experience guilt and shame when acting in contravention of those values.

MOHO associates two concepts with values. These are personal convictions and a sense of obligation. Respectively, these link values to the worldviews that people hold and the actions they are likely to take. Kielhofner (2008) defined personal convictions as “strongly held views of life that define what matters” (p. 40). Personal convictions are more than what people believe and include their worldviews and perspectives. That is, they are what persons believe to be important. Whereas some aspects of a worldview might be relatively easy to change, personal convictions about what matters are not. MOHO also emphasizes the connection between values and action. Kielhofner (2008) suggested that “values bind people to action” (p. 41) through a sense of obligation to act in ways that are consistent with their values. Therefore, self-esteem and sense of self-worth can be reduced when people’s ability to perform is not consistent with their values or those of the society (where those societal values matter to them). In addition, where enduring changes to people’s capacities occur (which change their ability to act in the world), the need for action and values to be consistent can prompt a process of revising one’s values.

The third aspect of volition is interests. This concept relates to those things that people find enjoyable or satisfying. As Kielhofner (2008) stated, “interests reveal themselves both as the enjoyment of doing something and as a preference for doing certain things over others” (p. 42). Enjoyment can derive from any constellation of factors including bodily pleasure, fulfilment from intellectual and artistic pleasures, the handling of materials and production of something pleasing, and fellowship with others. Kielhofner associated the attraction individuals might have to particular occupations with the concept of “flow” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). In flow experiences, people are engaged deeply in something and often experience a sense of timelessness. Flow experiences result when the demands of the activity or occupation optimally match the capacities of the individual. The implication is that enjoyment (and, therefore, interest) typically increases when individual capacities match activity demands.

Kielhofner also suggested that people develop a unique pattern of interests, which accumulates through experience. People make choices about occupation over time, according to their preferences, and these often develop into a pattern of choices. He suggested that the patterns of interests that people develop are “usually paralleled by a routine in which their interests are at least partially indulged” (p. 44). The concept of a pattern of interests forms a link to the next component of MOHO: habituation.

Habituation

MOHO proposes that the things that people do in their daily lives become routinized and taken for granted through a process of habituation. Habituation is defined as “an internalized readiness to exhibit consistent patterns of behaviour guided by habits and roles and fitted to the characteristics of routine temporal, physical and social environments” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 52). It serves the purpose of reducing the degree to which decisions about action have to be made consciously.

Habituation is assumed to require cooperation with the environment in order to support people’s routine action, in that, a degree of environmental stability is necessary for the development of habitual occupational performance. Using an image with broader application than to humans alone, Kielhofner stated, “The regularity in habituated behaviour depends on the reliability of habitats” (p. 52). The stability of habits relies on temporal patterns (e.g. daily, weekly, annual cycles), a stable social order and a consistency of physical places that an individual might inhabit.

Kielhofner (2008) presented two components of habituation. These are habits and internalized roles. Habits are patterns of behaviour that have a level of consistency about them and are often performed automatically. That is, the decision to engage in them and, often, to carry them out requires little thought. In addition, once commenced, habits require low levels of conscious effort, which frees up thought for other things while undertaking habitual activity. Habits rely on a familiarity with the environment that allows people to internalize rules for behaviour. When these rules have not been developed, often because the environment (or aspects of it) is novel, people are unable to respond in habitual ways.

The advantage of habits is both the freeing up of conscious thought for other things and, often, efficiency of response. For example, where habits have developed from action that has been modified over time within the same context, they can result in efficient and effective behavioural responses to that environment. Expertise in a particular area may be a result of this process, in that, experts often appear to know what to do and are able to act with little apparent thought (respond habitually). It is only when something about the situation presents itself as novel that experts seem to need to engage in problem solving and deciding the best course of action.

Kielhofner (2008) identified three types of habits. First, the term habits of occupational performance refers to how people habitually perform routine activities. People develop habitual ways of doing daily activities such as dressing and bathing, as well as other frequently performed activities such as cooking, eating, and working. Second, people develop habits of routine. This refers to how people use time and space and how these ways become routinized. These routines can apply to different periods of time. For example, they could be daily (or within the day), weekly such as routines related to activities such as work or school (i.e. when you are working/studying and when you are having time off), seasonal (e.g. farmers), annual and so forth. Third, people develop habits of style. This refers to one’s typical way of being in the world. Some examples that Kielhofner gave were whether a person typically attended to details or preferred to look at the broader picture, and whether they were prompt or procrastinating, quiet or talkative and trusting or cautious.

Over the course of the lifespan, habits can remain relatively stable or change. For example, some habits are considered socially acceptable at certain ages but not others. For an individual, some habits might serve an adaptive purpose at some times or in some circumstances and might gain an unwanted response in other situations. Some habits are the result of socialization and others are more related to the individual’s particular experiences and ways of living.

The second component of habituation is internalized roles. The social system surrounding a person influences the roles that the person might desire, choose, be expected to fulfil or be prevented from obtaining. Roles powerfully influence the way human occupation is performed. As Kielhofner (2008) suggested, the process of internalizing roles “means taking on an identity, an outlook, and actions that belong to that role. Consequently, an internalized role is the incorporation of a socially and/or personally defined status and a related cluster of attitudes and actions” (p. 59).

In MOHO, an important aspect of internalized roles is role identification. Roles contribute to a person’s self-identity. As Kielhofner (2008) stated, “identifying with any role means internalizing both what attributes society assigns to the role and one’s personal interpretation of that role” (p. 60). When people take on roles they gain feedback about both their own perceptions of how well they have fulfilled those roles and the perceptions of others in society. All of this feedback contributes to how people think and feel about themselves. Internalized roles also provide people with “an internalised script” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 60) that guides their behaviour by providing an understanding of the expectations of others and of themselves.

Kielhofner (2008) also proposed that roles organize occupations by: (1) influencing the style and content of people’s actions; (2) shaping what people do; and (3) giving organization to time and space (e.g. by being in a certain role at a certain time in a certain place). Roles change over time, as people grow and mature, change their interests and plans, and as the context in which they live changes or their abilities change. As roles change, people’s occupational engagement and performance will also change. An individual’s capacity for performance and his or her experience of performance contribute to his or her ability to carry out roles and are described in the following section.

Performance capacity and the lived body

In this third component of MOHO, the focus moves from the volition to act and the habits and roles that support and surround action to the action itself. In MOHO, action, referred to as performance, is discussed in terms of the capacity for performance and the embodied experience of performance. The phenomenological term “the lived body” is used to label this embodied experience.

Performance capacity refers to “the ability to do things” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 68) and is conceptualized as having objective and subjective components. Objective components of performance capacity include the capacities of body systems such as musculoskeletal, neurological and cardiopulmonary systems, amongst others, as well as cognitive abilities. Kielhofner (2008) identified that other occupational therapy conceptual practice models detail performance capacities in greater depth by providing “specific explanations of physical and mental components and their contribution to performance” (p. 18). Examples include motor control models, cognitive approaches, etc. In contrast, MOHO provides little detail about these objective performance components, but emphasizes that performance capacity has both objective and subjective aspects.

Subjective experience refers to how the individual experiences performance and is understood to shape that experience. Kielhofner (2008) viewed attention to subjective experience as a neglected aspect of performance in occupational therapy, claiming that “focusing on the subjective aspect of performance capacity is complementary to the traditional objective approach” (p. 69). He referred to objective approaches as viewing performance capacity “from the outside” and subjective experience of performance capacity as viewed from the “inside” (p. 69). However, he proposed that, when occupational therapists ask people about their subjective experiences, they are actually doing so in order to build “an objective picture of performance capacity” (p. 69).

In the fourth edition of MOHO, the concept of subjective aspects of performance capacity is mainly discussed in contrast to objective performance components without providing much detail about what subjective aspects of performance includes. Therefore, it is unclear whether the subjective experience of performance capacity is conceptualized as separate to or a part of the other concept related to this component of human occupation, “the lived body”.

The term lived body comes from phenomenology (a discipline of philosophy) and refers to the body as it is lived or experienced. It has been used in occupational therapy to refer to the embodied experience of performance (Mattingly & Fleming, 1994), that is, the fact that we live and move in a particular body, which shapes our experience of action. Subjective performance components might be conceptualized as part of the lived body. In explaining the concept of the lived body, Kielhofner (2008) made reference to the philosopher Merleau-Ponty: “unlike the objective approach which describes performance from a detached, objective perspective, he [Merleau-Ponty] emphasized a phenomenological approach that considered subjective experience as fundamental to understanding human perception, cognition, and action” (p. 70).

“The lived body” emphasizes that the body is the vehicle through which life is lived and performance is experienced. Therefore, the capacity for and carrying out of performance is dependent on each individual’s particular body. Phenomenology emphasizes that, in ordinary experience, the body forms the invisible background against which people attend to the occupations they are performing. The focus of attention is on the occupation rather than the body’s participation in it. When people acquire impairments or have changes to their capacities, the body often comes to the foreground and can become the focus of attention.

In explaining the implications of the lived body for understanding human occupation, Kielhofner (2008) stated, “the lived body concept underscores two fundamental ideas” (p. 70). These are that (1) from the lived body perspective, there is a unity of mind and body (in that we experience our body and mind in an integrated way, as part of our bodies) and that (2) subjective experience of performance is fundamental to performance (we experience our own action as a part of us rather than as something objective and separate). Kielhofner argued that insufficient attention has been paid in occupational therapy to the lived experience of human occupation compared to its objective components.

Environment

In MOHO, the term environment refers to “the particular physical and social, cultural, economic, and political features of one’s contexts that impact upon the motivation, organisation, and performance of occupation” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 86). As this definition emphasizes, the context within which an individual performs occupation shapes all three components of human performance − volition, habituation and performance − which motivate, organize and carry out occupation, respectively. Environments can provide opportunities and resources for occupation whilst also placing demands and constraints on it. In these ways, it is an important factor in shaping performance of occupation. Kielhofner referred to this process as “environmental impact” (p. 88).

Kielhofner (2008) presented a view of occupation in which a person is surrounded by four factors − spaces, objects, occupational forms or tasks, and social groups. Encompassing all of these are culture and its economic and political conditions. The person and the four factors surrounding the person are understood to be mutually influencing and the three conditions of the broader context influence all of the other factors.

Spaces refer to the physical contexts that shape behaviour. They have unique properties that influence what is done within them. These spaces could be man-made or part of the natural environment. Objects are “naturally occurring or fabricated things with which people interact and whose properties influence what they do with them” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 88). Different types of objects lend themselves to different types of manipulation. For example, raw materials might tend to encourage imaginative play in children, whereas other objects are designed for specific purposes and are likely to shape their use accordingly. Occupational forms and tasks is a reference to Nelson’s (1988) distinction between the things people do and the doing of them, which he called occupational form and performance, respectively. As Kielhofner (2008) stated, “the notion of form refers to the specific manner, actions, meanings, and so on that characterize doing something. When we perform, we go through or enact the form” (p. 92). He defined occupational forms/tasks as “conventionalised sequences of action that are at once coherent, oriented to a purpose, sustained in collective knowledge, culturally recognizable, and named” (p. 93). In discussing this definition he emphasized that occupational forms become conventionalized because there is usually a typical way to do them within a particular culture. Social groups provide the context within which much action occurs. They are influential in that they shape people’s values, beliefs, interests and behaviours. The interactions in which people engage can be formal and informal, may be as small as a dyad and can influence what each person does.

Surrounding and influencing the person and all four factors in the environment is the broader cultural context with its economic and political conditions. Kielhofner (2008) described culture as “a pervasive feature of the environment” (p. 95) in which beliefs, values, norms, customs and so forth are shared and passed on through generations. Societies have cultural and sub cultural values and individuals will internalize these values to different extents. As part of the ways that societies are organized, economic and political factors influence what people do through the opportunities and resources people have (or do not have) access to and the demands and expectations that are placed on them according to their position within the society.

Dimensions of doing

All of these factors, both those internal to the person − volition, habituation and performance capacity − and the environment in which people live, influence what people do and how they do it. MOHO identified three dimensions of doing, all of which are influenced by volition, habituation, personal capacity and environmental conditions (context). These are occupational participation, occupational performance and skill. First, occupational participation refers to “engaging in work, play, or activities of daily living that are part of one’s socio-cultural context and that are desired and/or necessary to one’s well-being” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 101). Occupational participation refers to broad categories of doing, includes both performance and its subjective experience and has both personal and social significance. Kielhofner (2008) emphasized that the way participation is understood in MOHO is consistent with how it is used in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF). The second dimension of doing is occupational performance. Using Nelson’s concepts of occupational form and performance, Kielhofner described occupational performance as “literally going through the form” (p. 103) of occupation, that is, doing an occupation. Third, the skill dimension refers to those skills that are required to perform the occupation. In MOHO these are categorized as motor skills (related to moving self or objects), process skills (logically sequencing actions over time) and communication and interaction skills (conveying needs and intentions and acting with others). As mentioned, volition, habituation, performance capacity and context impact upon all three dimensions of doing.

Lifespan perspective

MOHO also emphasizes that human occupation changes over time as age and circumstances change and that it needs to be understood from a whole-of-life perspective. Drawing upon narrative theory, Kielhofner et al. (2008) commented that, “people conduct and draw meaning from life by locating themselves in unfolding narratives that integrate their past, present, and future selves” (p. 110). Lives have a temporal dimension and people have a biographical history that shapes their interpretations and behaviours in the present. They also think, feel and act in the present according to their goals and aspirations for the future.

Kielhofner et al. (2008) presented plot and metaphor as elements of narrative that people use to integrate their lives as a whole and create meaning. Plot gives narrative its structure and provides the temporal linking of events into an integrated whole. The authors gave examples of different plots that might characterize a person’s life narrative, such as tragic plots (with a steep downward turn) and melodramatic plots (with a series of ups and downs). They provided three examples of the overall shape of a narrative, progressive (upward), regressive (downward) and stable (slight ups and downs around a middle point), that will influence a person’s interpretation of individual events. For example, if people’s life narratives are generally progressive or stable, they are more likely to interpret a particular event positively than someone with a regressive shape to their life narrative.

Metaphor is a figure of speech in which something familiar is used to substitute for something else. They are useful for conveying a depth of meaning that would be difficult to express using description alone. Often metaphors carry meanings that relate to the broader culture or society, so they are often imbued with shared meanings. Kielhofner et al. (2008) proposed that metaphors can be useful in making sense of difficulties and challenges and stated, “in pinpointing the essential nature of life’s problems, struggles, and dilemmas, they also imply how they can be solved or overcome” (p. 112).

Using the concept of a narrative organization of life, Kielhofner et al. (2008) used the term occupational narrative to refer to “a story (both told and enacted) that integrates across time one’s unfolding volition, habituation, performance capacity, and environments through plots and metaphors that sum up and assign meaning to these elements” (p. 113). Occupational narratives would be one part of a person’s life narrative that relates to what they do and how this impacts upon their occupational identity and sense of occupational competence.

The concept of occupational narrative emphasizes the temporal nature of human occupation. MOHO presents human occupation as a complex phenomenon with a range of dimensions. It results from the complex interaction between unique individuals − with their own particular motivations, interests and values (volition); habits, routines and internalized roles (habituation); and capabilities and experiences of themselves and their lives (performance capacity and the lived experience) – and their environments over time. These interactions can be relatively stable or marked by upward or downward trends over time.

The structure of MOHO differs greatly from many of the other occupational therapy models. It deals with the interaction between a person and his or her context when doing things. Like most occupational therapy models, it emphasizes the various ways that the context in which occupation is performed shapes that performance. However, the detailed analysis of volition and habituation, attention to the narrative aspects of occupational life and the relative lack of detail about performance sets it apart from many of the other occupational therapy models of practice. The section that follows discusses the historical development of the model, particularly in relation to its theoretical foundations.

Historical description of model’s development

MOHO is an occupational therapy model that has had a very long publication history. According to Kielhofner (2008), MOHO was first published in 1980 in a series of four articles in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy. He described the model as “the product of three occupational therapy practitioners attempting to articulate concepts that guided their practice” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 1). As a single volume, MOHO has been published in four editions, commencing in 1985 and spanning the intervening decades to 2008. It is a conceptual model that has influenced occupational therapy theory and practice over, possibly, the most sustained period of the profession’s history.

The Model of Human Occupation is an important model in occupational therapy because it was developed at a time when occupational therapy was very influenced by the ideas of the biomedical model of health. According to Madigan and Parent (1985), Mary Reilly, from the University of Southern California (USC), had been cautioning occupational therapy since the late 1950s that its alignment with medicine was too narrowing. Reilly’s argument had been that medicine’s focus was on the prevention and reduction of disease and illness, whereas occupational therapy dealt with the process of helping people to adapt their lives to develop and preserve life satisfaction “through work and social development” (Madigan & Parent, 1985, p. vii). Reilly’s theory of occupational behaviour guided research and teaching at USC for a number of decades and was an important influence in the development of MOHO.

In 1985, Madigan and Parent explained that the MOHO publication was “the latest compilation of many persons’ efforts to build and apply a theory unique to occupational therapy” (Madigan & Parent, 1985, p. vii). At that time, Kielhofner explained the need for a model by saying that the extensive development that occurred in the occupational behaviour tradition led to the development of many concepts. He stated, “Since the number of concepts grew to be large and somewhat cumbersome, it became necessary to develop models of practice which integrated these concepts into a workable format. The model of human occupation began as one such model which sought to build upon the existing occupational behaviour tradition” (Kielhofner, cited in Madigan & Parent, 1985, p. xviii).

It appears that, at the time of the 1985 publication, it was unclear whether Kielhofner’s MOHO was “an extension and further evolution of occupational behaviour theory” or whether it was a new direction in theory (Madigan & Parent, 1985, p. ix). While it was clear that the model flowed logically from occupational behaviour in terms of its major concepts of “role, interests, values, personal causation, intrinsic motivation, and environment, to name a few” (Madigan & Parent, 1985, p. ix), Reed was also cited as taking the position that MOHO was different from occupational behaviour theory (although clearly developed from it). Over time, as the model has been further developed, its difference from occupational behaviour theory has been demonstrated clearly.

In some ways, the model has changed enormously over time while its overall structure has remained similar. A major change has been the way its basis in systems theory has been described over time. A discussion of the particular aspects of systems theory that influenced the model in its first edition will make evident how the model came to be structured as it is, with the components of volition, habituation and performance capacity. Volition, habituation and performance were originally described as subsystems in 1985 and conceptualized as having a hierarchical relationship. However, in the second edition they are described as a heterarchy of subcomponents (explained later) and in the fourth edition (2008) they are called “interrelated components” (p. 12) and are conceptualized as non-hierarchical and mutually influencing.

In explaining the systems basis to the model, in all four editions Kielhofner contrasted it with a mechanistic perspective. In the third edition, Kielhofner (2002) explained that the model had originally been developed in response to the profession’s previous alignment with medicine, with its mechanistic understanding of health. (As explained in the introduction to this book, the adoption of systems theory in the area of health allowed for a broader understanding in Western countries of the factors that affect an individual’s health.)

The first two editions of MOHO explained various aspects of systems theory as the basis for its understanding of human occupation. In the first edition, the model was presented as based on open systems theory. In this edition, Kielhofner (1985) contrasted open and closed systems theory by showing that closed systems (e.g. machines) wear down with use (entropy) while open systems have the capacity to build up and become more complex (negative entropy). The implication in terms of occupation is that humans can develop and become more complex through doing.

The second edition of MOHO is based on dynamic systems theory. In the first edition, volition, habituation and performance were conceptualized as subsystems and understood to have a hierarchical relationship where the higher systems command the lower systems and the lower systems constrain the higher systems. Thus, for example, volition was considered the highest subsystem and thought to command, but be constrained by, the lower ones.

A major difference between dynamic and open systems theory is that, in dynamic systems, the organism is considered to have the capacity to reorganize itself. The way systems maintain themselves in optimal conditions is referred to as their “steady state” (Kielhofner 1985, p. 7). In an open systems view, systems maintain their structure. However, dynamic systems theory assumes that organisms are able to reorganize themselves and become more complex. Prigogine and Stengers (1984), in their book Order out of Chaos, used the example of water flowing in a stream to illustrate the assumption of the capacity to reorganize in dynamic systems theory. As water flows over rocks, it becomes increasingly destabilized and chaotic (splashes, etc.). However, as its steady state becomes more and more disturbed, it can reorganize itself, for example, into a whirlpool, which is organized differently from the currents in the original stream.

Consistent with this change from open systems theory to dynamic systems theory, the relationship between the subsystems of MOHO (volition, habituation and performance) in the second edition were no longer considered to be a hierarchy but a heterarchy. As Kielhofner (1995) explained, “The concept of heterarchy recognizes that systems arrange themselves according to the demands of situations in which they are performing, not according to a preordained or fixed structure” (p. 34).

The concept of heterarchy was applied to MOHO through the assumption of “dynamical assembly of behaviour” (Kielhofner, 1995, p. 14). When using a mechanistic metaphor (common in biomedicine) the assumption is that structure causes function. This suggests that behaviour can be predicted according to the structure of the organism. However, when applied to humans, structure is unable to explain their potential for behaviour and how humans select from all of these possible behaviours. As Kielhofner (1995) stated, “Humans perform in an almost infinite variety of emotional, cognitive, and physical circumstances” (p. 15) and he proposed that no two instances of performing the same activity are exactly the same because humans are able to assemble their behaviour differently as the circumstances demand. Just as the water flowing across rocks can reorganize itself to suit the surroundings, so too humans engage in “self-organisation” through occupation. As Kielhofner (1995) stated, “When we work, play, and perform the tasks of daily life, we are not merely engaging in occupational behaviour, we are organising ourselves. We use our bodies and minds in the contexts of occupations, organizing them accordingly. We create our motor abilities, our self-concepts, social identities in our occupations. Occupational behaviour is self-making.” (p. 22.)

The model’s basis in systems theory was discussed most overtly and in most detail in the first two editions. In the third and fourth editions, a systems perspective (as a general concept) is mentioned (rather than explained in detail) and is mainly contrasted with a mechanistic perspective (the main purpose appears to be distinguishing MOHO from the reductionist perspective of biomedicine). Three concepts of systems theory are emphasized in both later editions. These are heterarchy, emergence and control parameter.

First, heterarchy can be contrasted with hierarchy. As explained before, hierarchy refers to an organizational structure in which the higher levels command the lower levels and the lower levels constrain the higher levels. In contrast, heterarchy assumes a non-hierarchical organization in which the components function according to the needs of the whole. That is, components contribute to the whole according to their capacities and the relationship between different components is reorganized according to the requirements of the whole. In relation to MOHO, this means that the four components − volition, habituation, performance and environment − are assembled (or called upon) according to the occupational requirements in the situation. Second, Kielhofner (2008) defined emergence as “the principle that complex actions, thoughts, and feelings spontaneously arise out of the interactions of several components” (p. 25). This suggests that these actions, thoughts and feelings are not predetermined but emerge from the combination of volition, habituation, performance and environment (which will be uniquely assembled for each situation). Third, a control parameter is a factor that changes the whole dynamic when it changes. Kielhofner described it as a “critical change” that results in a “different emergent behaviour” (p. 26). What this means is that a change in any of volition, habituation, performance and/or the environment will result in the need for a different behavioural response.

The second way that MOHO has developed over its four editions relates to performance. In the first edition, performance was considered the lowest level in the hierarchy of subcomponents within the person. Therefore, it was initially conceptualized as commanded by volition and habituation and able to constrain both. In later editions, the performance component became labelled performance capacity and the lived experience. This relabelling shows a shift in attention to the capacity to perform and an emphasis on subjective experience of performance, both of which centre on the process of and potential for performing rather than just performance as an outcome. In including the concept of the lived experience, the MOHO developers appear to have been influenced by the work of Cheryl Mattingly, an anthropologist who introduced this concept to occupational therapy during her work on the AOTA clinical reasoning project in the 1980s (see Mattingly & Fleming, 1994). Mattingly discussed the concept of the lived experience when describing the work of the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty on phenomenology and embodied experience. Phenomenology distinguishes between an event and a person’s experience of that event and Merleau-Ponty further emphasized that a person experiences the world through his or her body. Thus, the capacity to perform and the individual’s experience of that capacity and of performing are important aspects of the later editions of MOHO.

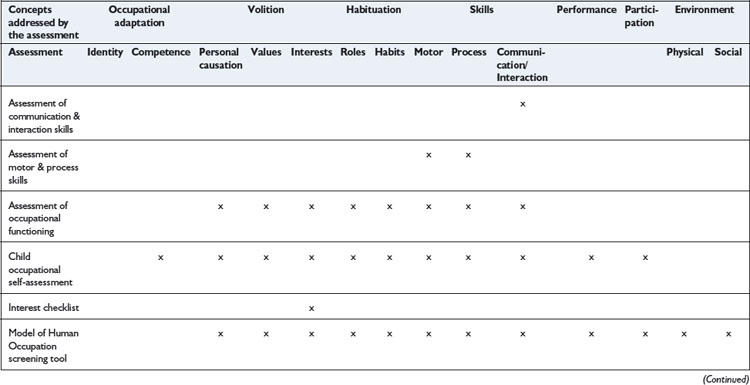

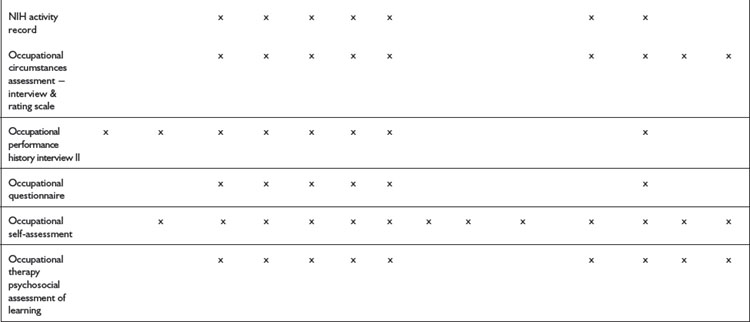

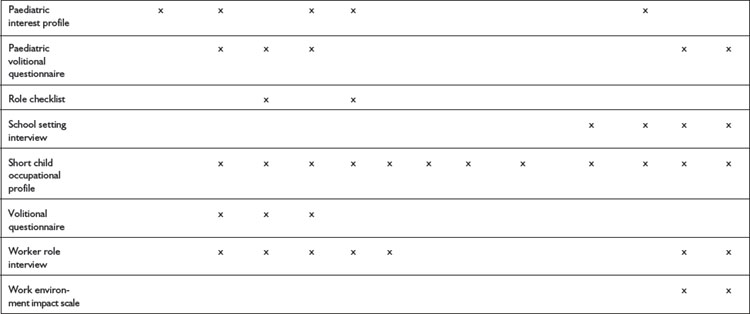

The third major way that MOHO has progressed over time is through the development of its tools to assist practice. While only a brief overview is provided here, readers are encouraged to refer to the fourth edition, which provides a variety of chapters discussing the occupational therapy process, assessment and intervention. First, Kielhofner and Forsyth (2008a) presented a six-step therapeutic reasoning process. This consisted of: (1) generating questions to guide information gathering; (2) gathering information on or with the client; (3) creating a conceptualization of the client that includes strengths and challenges; (4) identifying goals and plans for client engagement and therapeutic strategies; (5) implementing and reviewing therapy; and (6) collecting information to assess outcomes. Second, a variety of assessment tools have been developed to assist with the collecting of information about the important concepts within MOHO. Table 6.1 provides a list of assessment tools and the MOHO concepts they address. Assessments use the methods of observation, self-report and interview to collect information.

Third, regarding intervention, Kielhofner and Forsyth (2008b) provided nine types of client effort that could contribute to change in occupational engagement. They proposed that it is important for occupational therapists to consider these when working with clients. These are:

Kielhofner and Forsyth (2008c) also identified nine therapeutic strategies for enabling change. These were:

They proposed that these therapeutic strategies are used to influence occupational engagement and to complement the different types of effort that clients can contribute to the therapeutic encounter. They also emphasized that the strategies identified are based on MOHO theory, so occupational therapists using MOHO should be familiar with its theory.

In summary, MOHO has changed and developed over three decades. While some concepts have remained from the original edition (volition, habituation and performance), the theoretical assumptions about humans and their occupation have changed over that time. That is, humans were conceptualized initially as open systems, then as dynamic systems and then as having interrelated components. Over time, the model has increasingly emphasized the capacity for people to organize their component skills uniquely as the occupation and context requires.

Memory aid

See Box 6.1.

Adapted from Kielhofner, 2008, p. 148.

Conclusion

MOHO is the occupational therapy model of practice that has the longest continuous progress, with it being updated and developed for three decades to date. It was first created to provide organization to many of the concepts associated with the occupational behaviour tradition. The first two editions situated its conceptual basis within systems theory and focused on the person as comprised of subsystems that influenced performance. These subsystems were volition, habituation and performance. At the time of its early development, it was one of the few models of practice that attended to the motivational aspects of human occupation. Therefore, it was quite influential in contributing to an understanding of people’s occupation that went beyond a focus on the body and impairments to sensorimotor, cognitive and psycho- social functions.

The third and fourth editions of MOHO de-emphasized systems theory as a theoretical basis, and focused increasingly on the relationship between the person and the environment during occupation. While the concepts of volition, habituation and performance remained, they were no longer conceptualized as components of a system. Instead, they were used to understand how people “select, organise and undertake their occupations” (Kielhofner, 2008, p. 12). In these two editions, these three concepts were considered, along with the environment, as part of a set of four major concepts used to understand human occupation. These four concepts were also combined with participation, performance, skill, occupational identity, occupational competence and occupational adaptation in the later two editions.

A unique feature of MOHO is the substantial development of assessment tools that has taken place over time. No other model of practice has developed these types of tools to this extent. Consistent with the model’s focus on subjective experience, these assessments use observation, self-report and interview. The model also outlines processes to guide intervention.

Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, second ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, third ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, fourth ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Rowe, 1990.

Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, second ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, third ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application, fourth ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Kielhofner G., Forsyth K. Therapeutic reasoning: planning, implementing, and evaluating the outcomes of therapy. In: Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. fourth ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:143-154.

Kielhofner G., Forsyth K. Occupational engagement: How clients achieve change. In: Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. fourth ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:171-184.

Kielhofner G., Forsyth K. Therapeutic strategies for enabling change, fourth ed. Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008:185-203.

Kielhofner G., Borell L., Holzmuller R., et al. Crafting occupational life. In: Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. fourth ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:110-125.

Madigan M.J., Parent L.H. Preface. In: Kielhofner G., editor. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1985.

Mattingly C., Fleming M.H. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis, 1994.

Nelson D. Occupation: Form and performance. Am. J. Occup. Ther.. 1988;42(10):633-641.

Prigogine I., Stengers I. Order out of chaos: Man’s new dialogue with nature. Boulder, CO: New Science Library, 1984.