5 Applications of gait analysis

The aim of this chapter is to provide a broad overview of some of the ways in which gait analysis is used, particularly in a clinical setting. It is not intended to transform the reader into an expert on the subject. Anyone planning to use gait analysis in clinical decision making should read all the texts listed at the end of this chapter, attend courses and training on the interpretation of gait analysis data, and if possible spend some time studying or working in a clinical gait laboratory. There are several national and international societies that specialise in such courses and training, such as the European Society of Movement Analysis for Adults and Children (ESMAC), the Gait and Clinical Movement Analysis Society (GCMAS) and the Clinical Movement Analysis Society (CMAS).

The applications of gait analysis are conveniently divided into two main categories: clinical gait assessment and gait research. Clinical gait assessment has the aim of helping individual patients directly, whereas gait research aims to improve our understanding of gait, either as an end in itself or in order to improve medical diagnosis or treatment in the future. There is obviously some overlap, in that many people performing clinical gait assessment use it as the basis for research studies. Indeed, this is the way that most progress in the use of clinical gait assessment is made.

Davis (1988) pointed out that there are considerable differences between the technical requirements for clinical gait assessment and those for gait research. For example, an intrusive measurement system and a cluttered laboratory environment might not worry a fit adult, who is acting as an experimental subject, but could cause significant changes in the gait of a child with cerebral palsy. In gait research, it might be acceptable to spend a whole day preparing the subject, making the measurements and processing the data, whereas in the clinical setting patients often tire easily and the results are usually needed as quickly as possible. The requirements for accuracy are generally not as great in the clinical setting as they are in the research laboratory, so long as the measurement errors are not large enough to cause a misinterpretation of the clinical condition. However, it is essential that those interpreting the data appreciate the possible magnitude of any such errors. Finally, the system must be able to cope with a wide variety of pathological gaits. It is much easier to make measurements on normal subjects than on those whose gait is very abnormal, which may explain why the literature of the subject is dominated by studies of normal individuals! A final and important point is that there is no value in using a complicated and expensive measurement system, unless it provides information which is useful and which cannot be obtained in an easier way.

Gait research may be divided into clinical and fundamental research, the former concentrating on disease processes and methods of treatment, the latter on methods of measurement and the advancement of knowledge in biomechanics, human performance and physiology.

Clinical gait assessment

Clinical gait assessment seeks to describe, on a particular occasion, the way in which a person walks. This may be all that is required, if the aim is simply to document their current status. Alternatively, it may be just one step in a continuing process, such as the planning of treatment or the monitoring of progress over a period of time.

Rose (1983) made a distinction between gait analysis and gait assessment. He regarded gait analysis as ‘data gathering’ and gait assessment as ‘the integration of this information with that from other sources for the purposes of clinical decision making’. This usage of the term ‘analysis’ differs from that in more technical fields, in which it means ‘the processing of data to derive new information’. However, Rose's use of the term is helpful, because it points out that gait assessment is simply one form of clinical assessment. Medical students are taught that clinical assessment is based on three components: history, physical examination and special investigations. In this context, gait analysis is simply a special investigation, the results of which will augment other investigations, such as X-ray reports and blood biochemistry, to provide a full clinical picture. The term ‘gait evaluation’ is sometimes used instead of gait analysis.

The simplest form of gait assessment is practised every day in physician offices, physiotherapy and rehabilitation clinics, orthotic and prosthetic clinics, sports centres, and many other settings throughout the world. Every time a clinician watches a client or patient walk up and down a room, they are performing an assessment of the patient's gait. However, such assessment is often unsystematic and the most that can be hoped for is to obtain a general impression of how well the patient walks, and perhaps some idea of one or two of the main problems. This could be termed an ‘informal’ gait assessment. To perform a ‘formal’ gait assessment requires a careful examination of the gait, using a systematic approach, if possible, augmented by objective measurements. Such a gait assessment will usually produce a written report and the discipline involved in preparing such a report is likely to result in a much more carefully conducted assessment.

The gait analysis techniques which are used in clinical gait assessment vary enormously, with the nature of the clinical condition, the skills and facilities available in the individual clinic or laboratory and the purpose for which the assessment is being conducted. In general, however, clinical gait assessment is performed for one of three possible reasons: it may form the basis of clinical decision making, it may help with the diagnosis of an abnormal gait, or it may be used to document a patient's condition. These will be considered in turn.

Clinical decision making

Both Rose (1983) and Gage (1983) suggested that clinical decision making in cases of gait abnormality should involve three clear stages.

1. Gait assessment:

this starts with a full clinical history, both from the patient and from any others involved, such as doctors, therapists or family members. Where a patient has previously had surgery, details of this should be obtained, if possible from the operative notes. History taking is followed by a physical examination, with particular emphasis on the neuromusculoskeletal system. In many laboratories, physical examinations are performed by both a doctor and a physiotherapist. Finally, a formal gait analysis is carried out.

2. Hypothesis formation:

the next stage is the development of a hypothesis regarding the cause or causes of the observed abnormalities. This hypothesis is often informed by the specific questions raised by the referring doctor. Time needs to be set aside to review the data, and consultation between colleagues, particularly those from different disciplines, is extremely valuable. Indeed, almost all of those using gait assessment as a clinical decision-making tool stress the value of this ‘team approach’. In forming a hypothesis as to the fundamental problem in a patient with a gait disorder, Rose (1983) emphasised that the patient's gait pattern is not entirely the direct result of the pathology, but is the net result of the original problem and the patient's ability to compensate for it. He observed that the worse the underlying problem, the easier it is to form a hypothesis, since the patient is less able to compensate.

3. Hypothesis testing:

this stage is sometimes omitted, when there is little doubt as to the cause of the abnormalities observed. However, where some doubt does exist, the hypothesis can be tested in two different ways – either by using a different method of measurement or by attempting in some way to modify the gait. Some laboratories routinely use a fairly complete ‘standard protocol’, including video recording, kinematic measurement, force platform measurements and surface electromyography (EMG). They will then add other measurements, such as fine wire EMG, where this is necessary to test a hypothesis. Other clinicians start the gait analysis using a simple method, such as video recording, and only add other techniques, such as EMG or the use of a force platform, where they would clearly be helpful. Rose (1983) opposed the use of a standard protocol for all patients, since some of the procedures turn out to be unnecessary and there is a risk of ending up with ‘an exhausted subject in pain’. The other method of testing a hypothesis is to re-examine the gait after attempting some form of modification, typically by the application of an orthosis to limit joint motion, a medication such as botulinum toxin to decrease spasticity, or by anaesthetising a muscle. The ultimate form of gait modification is the surgical operation, with retesting following recovery. However, this is a rather drastic form of ‘hypothesis testing’, which can be used only where there is a good reason to suppose that the operation will lead to a definite improvement.

Different types of gait analysis data may be useful for different aspects of the gait assessment. Information on foot timing may be useful to identify asymmetries and may indicate problems with balance, stability, pain etc. The general gait parameters give a guide to the degree of disability and may be used to monitor progress or deterioration with the passage of time. The kinematics of limb motion describe abnormal movements, but do not identify the ‘guilty’ muscles.

The most useful measures are probably the joint moments and joint powers, particularly if this information is supplemented by EMG data. Hemiparetic patients may show greater differences between the two sides in muscle power output than in any of the other measurable parameters, including EMG. Winter (1985) stressed the need to work backwards from the observed gait abnormalities to the underlying causes in terms of the ‘guilty’ motor patterns, using both the EMG and the moments about the hip, knee and ankle joints. He offered a method of charting gait abnormalities and a table giving the common gait disorders, their possible causes and the type of evidence which would confirm or refute them (Table 5.1). Although the next step, that of treatment, was not considered in detail, he suggested that once an accurate ‘diagnosis’ had been made, the therapist would be challenged to ‘alter or optimise the abnormal motor patterns’ which requires the understanding of the biomechanical cause–effect relationships necessary to improve gait.

Table 5.1 Common gait abnormalities, their possible causes and evidence required for confirmation

| Foot slap at heel contact | Below normal dorsiflexor activity at heel contact | Below normal tibialis anterior EMG or dorsiflexor moment at heel contact |

|---|---|---|

| Forefoot or flatfoot initial contact | (a) Hyperactive plantarflexor activity in late swing | (a) Above normal plantarflexor EMG in late swing |

| (b) Structural limitation in ankle range | (b) Decreased dorsiflexor range of motion | |

| (c) Short step length | (c) See (a–d) immediately below | |

| Short step | (a) Weak push off prior to swing | (a) Below normal plantarflexor moment or power generation or EMG during push off |

| (b) Weak hip flexors at toe off and early swing | (b) Below normal hip flexor moment or power or EMG during late push off and early swing | |

| (c) Excessive deceleration of leg in late swing | (c) Above normal hamstring EMG or knee flexor moment or power absorption late in swing | |

| (d) Above normal contralateral hip extensor activity during contralateral stance | (d) Hyperactivity in EMG of contralateral hip extensors | |

| Stiff-legged weightbearing | Above normal extensor activity at the ankle, knee or hip early in stance* | Above normal EMG activity or moments in hip extensors, knee extensors or plantarflexors early in stance |

| Stance phase with flexed but rigid knee | Above normal extensor activity in early and mid-stance at the ankle and hip, but with reduced knee extensor activity | Above normal EMG activity or moments in hip extensors and plantarflexors in early and mid-stance |

| Weak push off accompanied by observable pull off | Weak plantarflexor activity at push off. Normal, or above normal, hip flexor activity during late push off and early swing | Below normal plantarflexor EMG, moment or power during push off. Normal or above normal hip flexor EMG or moment or power during late push off and early swing |

| Hip hiking in swing (with or without circumduction of lower limb) | (a) Weak hip, knee or ankle dorsiflexor activity during swing | (a) Below normal tibialis anterior EMG or hip or knee flexors during swing |

| (b) Overactive extensor synergy during swing | (b) Above normal hip or knee extensor EMG or moment during swing | |

| Trendelenburg gait | (a) Weak hip abductors | (a) Below normal EMG in hip abductors: gluteus medius and minimus, tensor fascia lata |

| (b) Overactive hip adductors | (b) Above normal EMG in hip adductors, adductor longus, magnus and brevis, and gracilis |

* Note: there may be below normal extensor forces at one joint but only in the presence of abnormally high extensor forces at one or both of the other joints.

Reproduced with permission from Winter (1985).

Many others working in the field of clinical gait assessment have noted the difficulty of deducing the underlying cause from the observed gait abnormalities, because of the compensations which take place. A number of attempts have been made to simplify this process, by using a systematic approach. Computer-based expert systems are very suitable for this type of application and a number of such systems have been developed for clinical gait assessment. Since gait patterns are seldom clear-cut, such expert systems cannot generally use a fixed set of rules but rather need to learn to recognise patterns within complex sets of data. Techniques such as neural networks and fuzzy logic have been explored for this purpose (Chau, 2001). No doubt the number and quality of such systems will increase in the future. The following paragraphs describe how gait assessment is used for clinical decision making in a ‘typical’ laboratory. The details will, of course, differ from one laboratory to another, based on the skills and interests of the laboratory personnel, the facilities and equipment available, and the types of patient seen.

When the patient arrives at the facility informed consent is taken, a thorough history is then obtained and a physical examination is performed, by both a doctor, a physiotherapist, and sometimes others such as a prosthetist. Height, weight and a number of other measurements are made. The patient's gait is video-recorded, viewing the patient from both sides and from the front and back. The ‘technological’ element of the gait analysis is performed, using a television/computer kinematic system and one or more force platforms. The number of cameras used is dictated largely by economics. Ideally, at least six cameras should be used but three can give acceptable data, particularly if measurements are made from only one side of the body at a time. Most laboratories record surface EMG, either on muscles which are selected on a case-by-case basis or on a standard set, such as gluteus maximus, quadriceps (in particular rectus femoris), medial and lateral hamstrings, triceps surae, tibialis anterior and the hip adductors. Depending on the clinical condition, fine wire EMG of selected muscles may be recorded, either at the same time or later. For example, Gage et al. (1984) reported that where a hip flexion contracture is present, their laboratory routinely records fine wire EMG from the iliopsoas, however this is not common clinical practice. There is variation in the protocols used, with some facilities recording kinetic, kinematic and EMG data at the same time, whereas others find it more convenient to record EMG separately.

Since great variability may exist between one walk and another, any single walk may not be representative, particularly if the patient hesitates or momentarily loses their balance. For this reason, a number of walks are recorded and the results examined for consistency. Depending on the clinical status of the patient, walks may be made under a number of different conditions, for example with and without shoes, with or without an orthosis, or using different walking aids. Activities such as rising from a chair or walking up and down steps can also be studied, however, it may not be possible to obtain force plate data.

Once preliminary reports on the history and physical examination have been prepared, the data processed and charts printed, the ‘team’ meets to discuss the case. The composition of the team varies considerably from one facility to another, but it would commonly consist of a doctor, a physiotherapist and a kinaesiologist or bio-engineer, with the optional addition of other doctors, physiotherapists, prosthetists, orthotists and podiatrists. Indeed, anyone with an interest in providing the best possible care for the patient may be invited to join the team to discuss a particular patient. In many facilities, the team includes the orthopaedic surgeon who will ultimately perform any necessary surgery.

The assessment begins with a careful review of the patient's history and the physical examinations by the doctor and physiotherapist. The gait video recording is watched frame by frame and discussed and notes are made for inclusion in a final report. The general gait parameters are noted to determine the degree of disability and the effects of any changes in conditions, such as orthoses or walking aids. Different gait analysis systems provide different amounts of technical data on the patient's gait and examination of the ‘charts’ can be a long and painstaking process. One of the most important parts of the assessment is to identify deviations from normal in the joint angles and to determine the cause of such deviations. This process is easier if joint moments and powers are available. Joint moments indicate in general terms which structures in the region of a joint are coming under tension and the degree of tension in them. Joint powers may help to discriminate between concentric muscle contraction, eccentric muscle contraction and passive tension in soft tissues. They can also distinguish between powerful and weak muscle contractions. The EMG also contributes to this process by identifying which muscles are electrically active and are thus candidates for developing tension at different times during the gait cycle.

Very briefly, interpretation of the gait analysis charts may involve the following steps. Commonly a comparison of the left to right sides is made when doing this.

1. Joint angle:

what is the angle of a joint at a particular part of the gait cycle and in which direction is it moving?

2. Joint moment:

what is the internal moment acting about the joint? This will indicate what muscles or ligaments are under tension and to what degree.

3. Joint power:

what power generation or absorption is taking place? This would indicate concentric or eccentric contraction, or storage and release of energy by stretching elastic tissues.

4. EMG:

what is the muscle electrical activity and is it consistent with the kinematic data?

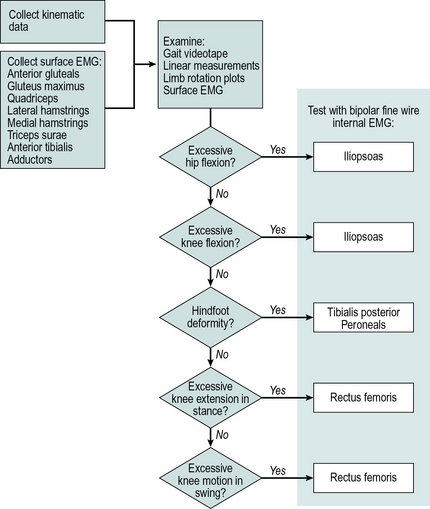

At this time, a hypothesis is formed as to the detailed cause of any gait abnormalities present. This may indicate a need for further data, such as fine wire EMG recordings from other muscles (Fig. 5.1), and the patient may be asked to return for further tests. Having made a detailed diagnosis of the patient's functional problems, the team decides on an appropriate form of treatment. This could involve treatment through physiotherapy, orthotics, surgery, drug treatment, or a combination of these. In such cases, the final stage of assessment would be an ‘examination under anaesthesia’ when appropriate, made just prior to the commencement of surgery. The muscle relaxant used with the anaesthetic abolishes spasticity and makes it possible to distinguish between structural abnormalities, such as contractures, and the effects of muscle tension. If the treatment selected involves drug treatment, physiotherapy or the use of an orthosis, the patient would be monitored during the course of such treatment, to determine whether the initial decisions were appropriate.

Fig. 5.1 • Gait assessment flowchart, used for selecting muscles for testing with fine wire EMG

(©1988 IEEE. Reprinted, with permission, from Davis RB, Clinical gait analysis. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine September: 35–40).

Once treatment has been carried out and after a suitable recovery period, a further gait assessment is often performed. The purpose of this is firstly to determine the success of the treatment and secondly to decide whether the patient would benefit from further surgery, physiotherapy or the prescription of an orthosis. It also gives the clinical team the opportunity to perform a critical review of the original diagnosis and treatment plan, to decide whether the correct decisions were made. If an error has been made, it is important to recognise it and to learn from it, to prevent it from happening again. There is usually no change in EMG postoperatively and the main criteria for determining the success (or otherwise) of treatment are the general gait parameters and the joint rotations. In subjects in whom it can be measured from the kinematic data, the estimated external work of walking (EEWW) may also be used as a measure of improvement. According to Gage, total body energy consumption is the best measure of the success of treatment whereas Perry (2010) uses three criteria to gauge success: walking speed, energy consumption and cosmesis.

Diagnosis of abnormal gait

Most patients undergoing gait assessment have already been diagnosed, as far as the principal disease or condition affecting them is concerned. In such cases, gait assessment is carried out to make a more detailed diagnosis, relating to the exact state of particular joints and muscles. On occasion, however, a patient is seen in whom the cause of an abnormal gait is not clear.

A number of apparently abnormal gait patterns are, in fact, habits rather than the result of underlying pathology and the techniques of gait analysis may be useful to identify them. Since any pathology affecting the locomotor system generally reduces a person's ability to alter their gait pattern, a variable gait may be suggestive of a habit pattern and a highly reproducible gait may suggest a pathological process. However, the assessment must take many other factors into account, including the possibility of a pathological process which includes an element of variability, such as ataxia or athetosis. One unusual application of gait analysis is to distinguish between a gait abnormality due to a genuine neuromuscular cause and one due to a psychogenic cause, such as may be seen in cases of malingering (Wesdock et al., 2003).

An example of the use of gait assessment to differentiate between pathological gaits and habit patterns is in the diagnosis of toe walking. Some children prefer to walk on their toes, rather than on the whole foot, in a pattern known as ‘idiopathic toe walking’. It is important, but also quite difficult, to be able to differentiate between this relatively harmless and self-limiting condition and more serious conditions, such as cerebral palsy. Hicks et al. (1988) stated that earlier attempts to establish the diagnosis, using EMG alone, had not been successful. In their study, they compared the gait kinematics of seven idiopathic toe walkers and seven children with mild spastic diplegia. There was a clear difference between the two groups in the pattern of sagittal plane knee and ankle motion. Both groups had initial contact either by the flat foot or by toe strike but in the case of the toe walkers, this was due to ankle plantarflexion, whereas in the children with cerebral palsy it was due to knee flexion. There were also other differences between the two groups, suggesting that gait assessment would be very helpful in making a differential diagnosis.

Documentation of a patient's condition

Although clinical decision making is the most direct way in which gait assessment may be used to help an individual patient, there are also instances when simply documenting the current state of a patient's gait may be of value. For some purposes, such documentation may be needed only on a single occasion, where the aim is to quantify a patient's disability. For other purposes, a series of gait assessments over a period of time may be used to monitor either progress or deterioration.

As part of the overall assessment of a patient with a disability, a clinician may require more detail about how well they walk. This type of gait assessment may be directly intended for use in clinical decision making, but it is sometimes performed speculatively, in case it should reveal a treatable cause for the patient's walking disorder.

Gait assessment is frequently used to document the progress of a patient undergoing some form of treatment. The results of the assessment may be used to identify areas where the treatment is ineffective or it may define an end point for stopping treatment, when progress appears to have ceased. Another use of this type of serial assessment is to convince the patient or their relatives that progress has been made, when they think it has not. An objective form of monitoring progress is particularly important for use in the evaluation of novel and controversial methods of treatment, where the enthusiasm of the investigators has been known to lead to errors of judgement!

Gait assessment may form part of the overall documentation of a number of medical conditions that involve the locomotor system. A deterioration in gait with the passage of time may be detected early, allowing remedial action to be taken. It may also identify clinical signs which should be looked for in other cases of the same condition, particularly if it is very uncommon.

Conditions benefiting from gait assessment

A large number of diseases affect the neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems and may thus lead to disorders of gait. Among the most important are:

While it is possible that gait assessment may benefit a person affected by any one of these conditions, it is clear that greater benefits are possible in some pathologies than in others. The next two chapters will consider neurological and musculoskeletal conditions for which there is good evidence that gait assessment is worthwhile.

Future developments

Advanced techniques to quantify deviation from normality

There has been a recent surge of interest in trying to meet the requirements of clinicians and clients/patients looking for simple measures of gait which encapsulate the rich information content of a gait analysis, as opposed to detailed and lengthy gait reports typically generated by gait laboratories. The two opposing sides of simplicity and complexity represent the two approaches to abnormal human gait. On one side the clinician's and patient's result-oriented approach is that they aim to make gait more normal and so their focus is on the overall quality of gait (Kelly et al., 1997). On the other side the gait analyst's approach is to search for the causes underlying gait deviations by analysing gait quantitatively. Interventions prescribed by clinicians are based on the findings of the quantitative approach but are ultimately aimed at improving the quality of gait and so there is an incompatibility between the questions oriented to gait quality, and the answers derived from quantitative data. This incompatibility, however, can be resolved considering that the quantitative representation of a gait abnormality inherently contains a measure of deviation from normality distributed across a large number of gait curves. Therefore we need an appropriate method to extract a measure of gait quality from the quantitative gait data.

Only a few methods have been described which may bridge the gap between the quantitative and qualitative approach to gait by calculating overall quality measures derived from quantitative data. The normalcy index (NI) (Schutte et al., 2000) is a single number representing the deviation between a subject's gait and an average normal profile, calculated from 16 discrete gait variables measured by routine clinical gait analysis (timing of foot off, walking speed, cadence, walking distance, mean and peak angles of the pelvis, hip, knee and ankle joints in selected planes). The Gillette gait index (GGI) (Romei et al., 2004, 2005; Theologis et al., 2005) based on Schutte and co-workers’ NI was shown to be a reliable method sensitive enough to separate different pathological gait patterns. The GGI has been extensively evaluated (Romei et al., 2004; Wren et al., 2007) and has been used in gait analysis research to test if an intervention leads to improved gait function (e.g. Gorton et al., 2009). A similar index described by Tingley et al. (2002) considers multiple joint angle curves simultaneously and produces a single score that enables the classification of children as normal, unusual or abnormal.

Gait indices quantify the deviation of gait from normal and so can be regarded as measures of gait quality. Their use, however, does not extend to identifying the causes of gait problems because the single score characterises the patient's gait as a whole and therefore it cannot be related to when the deviations occur in the gait cycle or to which of the joints were the source of the deviation. A recognised limitation of the GGI is that the choice of the 16 kinematic parameters used to calculate the index was based on the subjective judgement of clinicians and so may not be the best possible set of parameters for different pathologies. Indeed, several authors (Romei et al., 2004, 2005; Schutte et al., 2000; Theologis et al., 2005) suggested the inclusion of additional gait variables to the GGI to further improve its potential.

The above limitations of gait indices, that they contribute little to establishing the cause–effect links underlying gait problems and that they are based only on a subset of the gait data, have been addressed in the work of Barton et al. (2003, 2007), Schwartz and Rozumalski (2008) and Baker et al. (2009). Barton et al. (2003) described the use of a ‘self-organising neural network’ to quantify the quality of gait. This allows a set of kinematic and kinetic variables taken from normal gait to ‘train’ the network, resulting in an autonomous definition of normality. The neural network can then be used to describe how far a patient's gait is from normality. An advantage of this technique is that it allows deviations from normality to be calculated at all points in the gait cycle, and it determines which joints contribute most to the deviations. Schwartz and Rozumalski (2008) addressed the limitations of the GGI by developing a new and comprehensive measure of gait pathology. A set of 15 gait features were extracted from nine joint angle curves of a large number of patients and typically developing control children to define the full spectrum of normal and pathological gait. The distance of a patient from the mean of controls in the 15 dimensional gait feature space was termed the gait deviation index (GDI). Validation of the GDI showed good agreement with measures of movement function and sub-types of pathologies. Baker et al. (2009), inspired by the GDI, developed the gait profile score (GPS) which is the root mean square difference between a patient's data and the mean of controls, taken over several kinematic variables along the entire gait cycle. Through validation against the GGI, GDI, and measures of motor function in a large number of patients, the GPS was found to be a closely related alternative to the GDI.

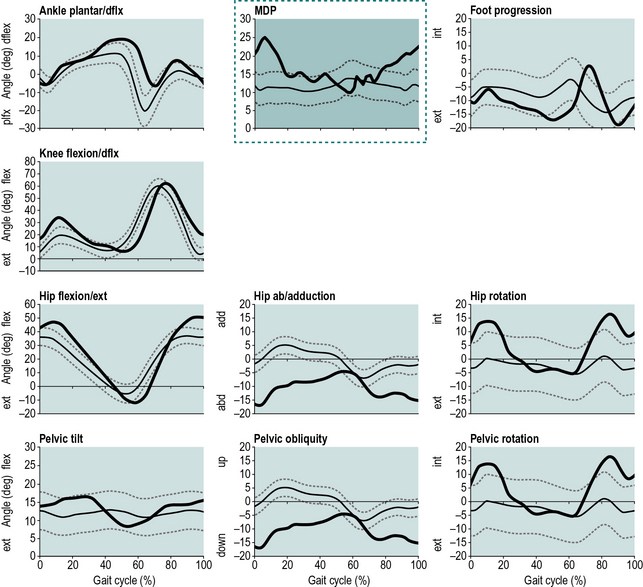

Barton et al. (2010) used artificial neural networks as an alternative to conventional analysis of large number of joint and moment patterns. Even without any knowledge of the pathological conditions in the population, the self-organising map (SOM) artificial neural network (Kohonen, 1988, 2001) was able to quantify the deviation from normality by calculating the distance between abnormal and normal patterns. Joint angles, recorded from typically developing children over one gait cycle, were used to train a SOM which then generated movement deviation profile (MDP) curves showing the deviation of patients’ gait from normality. The mean MDP over the gait cycle showed a high correlation (r2= 0.927) with the GDI, a statistically significant difference between groups of patients with a range of functional levels (Gillette functional assessment questionnaire walking scale 7–10) and a trend of increasing values for patients with cerebral palsy through hemiplegia I–IV, diplegia, triplegia and quadriplegia. Therefore the MDP can be regarded as an alternative method of processing complex biomechanical data, potentially supporting clinical interpretation. A stand-alone program which can be used to calculate the MDP from gait data is available as an electronic addendum accompanying the paper by Barton et al. (2010) in Human Movement Science and also from http://www.staff.ljmu.ac.uk/spsgbart/MDP.htm (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2 • The movement deviation profile (MDP) inserted in the conventional presentation of gait kinematics. Note that the axes and the presentation of a patient's MDP curve over the mean and SD of controls is identical to the other curves. The MDP chart (surrounded by a dotted line) summarises the other nine angle curves (bold curves) and shows the timing and extent of deviations from normality (thin curves) during the gait cycle (Barton et al., 2010).

Comprehending a full gait report may be too challenging but a single number gait index may hide details needed to find the cause of gait problems. A variety of related but different methods with firm theoretical justifications are now available, aiding the interpretation of gait data. Free software tools are accessible to calculate the GDI and GPS using Microsoft Excel, and the MDP with a stand-alone Windows program. Future research is now needed to identify the benefits and disadvantages of simplification through further validation against clinical criteria.

Modelling muscle forces and EMG-assisted models

Gait analysis has advanced significantly since joint moments and powers became routinely available. What would be of even more value, if it could be provided, would be knowledge of the forces in the different structures in and around the joints. The use of mathematical modelling permits estimates to be made of forces in tendons and ligaments and across articular surfaces. Unfortunately, a large number of unknown factors are involved, particularly the internal moments generated by different muscles and the extent of any co-contraction by antagonistic muscles. For this reason, such calculations can only be approximate but they may nonetheless be extremely valuable, particularly in clinical and biomechanical research. One example is Motek's Human Body Model, which calculates multiple muscle forces from three-dimensional (3D) kinematic data and dual force plates. The method uses inverse dynamics combined with optimisation performed by neural networks.

The output of mathematical models may be further refined using EMG. Most models offer a range of possible solutions, based on different combinations of active muscles. Even though it is not generally possible to convert EMG signals directly into muscle contraction force, the knowledge that a muscle is either inactive, contracting a little or contracting strongly may make it possible to eliminate at least some of the possible model solutions and thereby to improve the reliability of the results. These models try to account for changes in musculotendon length, velocity, and the amount of electrical activity for both concentric and eccentric contractions from multiple muscles, and correlate these with the joint moments. Results have varied considerably from joint to joint with the ankle showing the best correlations of up to 0.91 for normal walking (Lloyd and Besier, 2003; Bogey et al., 2005) and between 0.87 and 0.92 for stroke patients (Shao et al., 2009), however, as we consider the more proximal joints such as the knee and hip the correlations are lower. Most authors support the use of this approach to estimate muscle forces during gait, however research using such modelling techniques is still in the minority. This is mainly due to the fact that we do not always need to consider the internal forces in the tendinous and ligamentous structures as these are rarely the primary outcome measures in gait assessment.

Conclusion

Gait analysis has had a long history and for much of this time it has remained an academic discipline with little practical application. This situation has now changed and the value of the methodology has been unequivocally demonstrated in certain conditions, particularly cerebral palsy. We are seeing a decrease in the cost and improvements in the ease of use of an ever-increasing complexity of kinematic systems and an increasing acceptance by clinicians of the results of gait analysis. This trend will hopefully continue, so that the use of these techniques will increase, both in those conditions for which its value is already recognised and in a variety of other conditions.

Although the current text has focused on gait analysis, this type of measurement equipment may also be used for other purposes – a fact which may be relevant to those trying to obtain funds to set up a gait analysis laboratory! The use of force platforms and kinematic systems for balance and posture testing has been referred to, as has their use in studying performance in a wide range of sports. Clinical studies have also been made of people standing up, sitting down, starting and stopping walking, ascending and descending stairs. The equipment has been used to measure the movements of the back, not only in walking but also in the standing and sitting positions. It has also been used to monitor the movements of the upper limbs, both in athetoid patients and in ergonomic studies of reach. Walking is only one of many things which can be done by the musculoskeletal system. It is only sensible to broaden our horizons and to use the power of the modern measurement systems to study a wide range of other activities.

Baker R., McGinley J.L., Schwartz M.H., et al. The gait profile score and movement analysis profile. Gait Posture. 2009;30:265–269.

Barton G.J., Lees A., Lisboa P., et al. Visualisation of gait quality using self organising artificial neural networks. Gait Posture. 2003;18(Suppl. 2):119.

Barton G., Lisboa P., Lees A., et al. Gait quality assessment using self-organising artificial neural networks. Gait Posture. 2007;25:374–379.

(2010)Barton G.J., Hawken M.B., Scott M., et al. Movement deviation profile: a measure of distance from normality using a self organising neural network. Invited paper in Special Issue on Network Approaches in Complex Environments, Hum. Mov. Sci. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2010.06.003 (accessed 30.08.11.)

Bogey R.A., Perry J., Gitter A.J. An EMG-to-force processing approach for determining ankle muscle forces during normal human gait. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2005;13(3):302–310.

Chau T. A review of analytical techniques for gait data. Part 1: fuzzy, statistical and fractal methods. Gait Posture. 2001;13:49–66.

Davis R.B. Clinical gait analysis. September. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag.. 1988:35–40.

Gage J.R. Gait analysis for decision-making in cerebral palsy. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. Orthop. Inst.. 1983;43:147–163.

Gage J.R., Fabian D., Hicks R., et al. Pre- and postoperative gait analysis in patients with spastic diplegia: a preliminary report. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 1984;4:715–725.

Gorton G.E., 3rd., Abel M.F., Oeffinger D.J., et al. A prospective cohort study of the effects of lower extremity orthopaedic surgery on outcome measures in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 2009;29:903–909.

Hicks R., Durinick N., Gage J.R. Differentiation of idiopathic toe-walking and cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 1988;8:160–163.

Kelly I.P., O'Regan M., Jenkinson A., O'Brien T. The quality assessment of walking in cerebral palsy. Gait and Posture. 1997;5:70–74.

Kohonen T. Self-organisation and Associative Memory. Berlin: Springer; 1988.

Kohonen T. Self-organizing Maps. Berlin: Springer; 2001.

Lloyd D.G., Besier T.F. An EMG-driven musculoskeletal model to estimate muscle forces and knee joint moments in vivo. J. Biomech.. 2003;36:765–776.

Perry J. Gait analysis: Normal and pathological function. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Incorporated; 2010.

Romei M., Galli M., Motta F., et al. Use of the normalcy index for the evaluation of gait pathology. Gait Posture. 2004;19:85–90.

Romei M., Galli M., Motta F., et al. Reply to ‘Letter to the Editor’. Gait Posture. 2005;22:378.

Rose G.K. Clinical gait assessment: a personal view. J. Med. Eng. Technol.. 1983;7:273–279.

Schutte L.M., Narayanan U., Stout J.L., et al. An index for quantifying deviations from normal gait. Gait Posture. 2000;11:25–31.

Schwartz M.H., Rozumalski A. The gait deviation index: a new comprehensive index of gait pathology. Gait Posture. 2008;28:351–357.

Shao Q., Bassett D.N., Manal K., et al. An EMG-driven model to estimate muscle forces and joint moments in stroke patients. Comput. Biol. Med.. 2009;39(12):1083–1088.

Theologis T., Thompson N., Harrington M. Letter to the editor. Gait Posture. 2005;22:377.

Tingley M., Wilson C., Biden E., et al. An index to quantify normality of gait in young children. Gait Posture. 2002;16:149–158.

Wesdock K., Blair S., Masiello G., et al. Psychogenic gait: when it is and when it isn't – correlating the physical exam with dynamic gait data. Eighth Annual Meeting, Wilmington, Delaware, USA. Gait and Clinical Movement Analysis Society, 2003:279–280.

Winter D.A. Concerning the scientific basis for the diagnosis of pathological gait and for rehabilitation protocols. Physiother. Can.. 1985;37:245–252.

Wren T.A., Do K.P., Hara R., et al. Gillette Gait Index as a gait analysis summary measure: comparison with qualitative visual assessments of overall gait. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 2007;27:765–768.

Berchuck M., Andriacchi T.P., Bach B.R., et al. Gait adaptations by patients who have a deficient anterior cruciate ligament. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1990;72:871–877.

Cavanagh P.R., Hennig E.M., Rodgers M.M., et al. The measurement of pressure distribution on the plantar surface of diabetic feet. In: Whittle M., Harris D. Biomechanical Measurement in Orthopaedic Practice. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1985:159–166.

Davis R.B. Clinical gait analysis. September. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag.. 1988:35–40.

Harrington E.D., Lin R.S., Gage J.R. Use of the anterior floor reaction orthosis in patients with cerebral palsy. Orthotics and Prosthetics. 1984;37:34–42.

Hicks R., Tashman S., Cary J.M., et al. Swing phase control with knee friction in juvenile amputees. J. Orthop. Res.. 1985;3:198–201.

Jefferson R.J., Whittle M.W. Biomechanical assessment of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, total condylar arthroplasty and tibial osteotomy. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon). 1989;4:232–242.

Kohonen T. Self-organisation and Associative Memory. Berlin: Springer; 1988.

Kohonen T. Self-organizing Maps. Berlin: Springer; 2001.

Lehmann J.F., Condon S.M., Price R., et al. Gait abnormalities in hemiplegia: their correction by ankle-foot orthoses. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 1987;68:763–771.

Lord M., Reynolds D.P., Hughes J.R. Foot pressure measurement: a review of clinical findings. J. Biomed. Eng.. 1986;8:283–294.

Molloy M., McDowell B.C., Kerr C., et al. Further evidence of validity of the Gait Deviation Index. Gait Posture. 2010;31:479–482.

New York University. Lower Limb Orthotics. New York, NY: New York University Postgraduate Medical School; 1986.

Õunpuu S., Davis R.B., DeLuca P.A. Joint kinetics: methods, interpretation and treatment decision-making in children with cerebral palsy and myelomeningocele. Gait Posture. 1996;4:62–78.

Prodromos C.C., Andriacchi T.P., Galante J.O. A relationship between gait and clinical changes following high tibial osteotomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1985;67:1188–1194.

Roberts C.S., Rash G.S., Honaker J.T., et al. A deficient anterior cruciate ligament does not lead to quadriceps avoidance gait. Gait Posture. 1999;10:189–199.

Tashman S., Hicks R., Jendrzejczyk D.J. Evaluation of a prosthetic shank with variable inertial properties. Clinical Prosthetics and Orthotics. 1985;9:23–28.

Waters R.L., Garland D.E., Perry J., et al. Stiff-legged gait in hemiplegia: surgical correction. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1979;61:927–933.