Congenital disorders and diseases secondarily involving the urinary tract

Congenital urinary tract disorders

Introduction

Serious congenital disorders of the kidneys and urinary tract nearly all present at birth or in early childhood (see Ch. 51). The exception is polycystic kidney which presents more commonly in adulthood. Less common abnormalities of the upper tract may interfere with normal flow dynamics and predispose to infection, e.g. duplex systems or medullary sponge kidney. Asymptomatic abnormalities such as unilateral renal agenesis, renal cysts or horseshoe kidney may be discovered incidentally during investigation or during surgery. With advancing age, a large proportion of the population develops benign renal cysts; these are usually of no clinical consequence. A summary of congenital disorders that present after childhood is given in Table 39.1.

Adult polycystic kidney disease (PCKD) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by bilateral multiple cysts of renal parenchyma (see Fig. 39.1). The cysts slowly expand, compressing the parenchyma, and may disrupt local control of blood pressure and eventually impair renal function. Polycystic kidneys have three main variants:

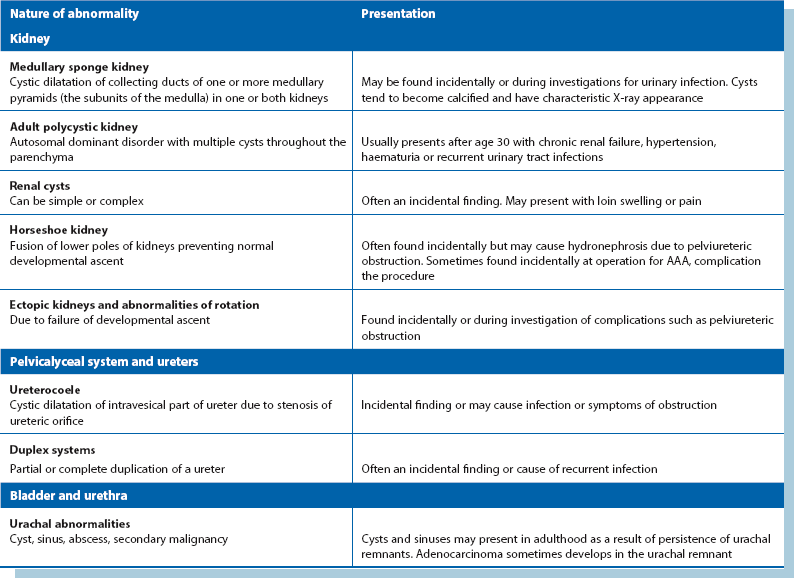

Fig. 39.1 Polycystic kidneys

IVU tomogram from a 52-year-old woman with hypertension and microscopic haematuria; both kidneys exhibit multiple lucent areas in the nephrogram representing cysts (arrowed) and the pelvicalyceal systems are slightly compressed

• A rare infantile form also affecting the liver; affected children often die young

• A serious adult form manifesting in middle age with hypertension or progressive renal failure. It is the commonest cause of inherited renal failure. Kidneys can appear normal on ultrasound scanning up to about the age of 20

• A less serious adult form usually found incidentally in later life with almost normal renal function. Patients are usually hypertensive

Thus, adult polycystic kidney may present with hypertension or progressive chronic renal failure. The enlarged kidneys may cause loin pain or be discovered incidentally on abdominal examination. These kidneys are vulnerable to even minor trauma, and haematuria and urinary tract infections are common presentations.

Some with polycystic disease also have multiple cysts in the liver and sometimes in the pancreas. They present with massive abdominal swelling due to gross liver enlargement. There is no specific treatment for polycystic kidney disease and despite good conservative management, about 50% will eventually require dialysis or renal transplantation.

Medullary sponge kidney

This is caused by cyst-like dilatation (ectasia) of the renal medulla collecting ducts and may affect one or both kidneys. Cysts tend to calcify, giving a characteristic radiographic appearance of streaky linear calcification of renal papillae (see Fig. 39.2). On excretion pyelography (IVU), tubular ectasia can be demonstrated as a ‘flare’ in the renal papilla. Marked degrees of medullary sponge kidney predispose to recurrent infection and stone formation because of intrarenal urine stasis but patients rarely present before adulthood. Minor degrees are often seen on IVU without causing symptoms.

Duplex systems

The urinary collecting system may be duplicated to a greater or lesser extent. Duplication is usually complete proximally but may be incomplete distally. Lesser duplications are usually asymptomatic and discovered by chance on imaging. Complete duplex ureter is relatively common and may result in renal damage from infection, reflux or obstruction (see Fig. 39.3). The ureter draining the upper renal pole (upper moiety) is often inserted ectopically into the urethra (or vagina), resulting in continuous incontinence. Otherwise it joins the bladder ectopically below the orifice of the lower pole ureter. The orifice is often tightly stenosed, causing obstruction. This causes back pressure on the kidney and sometimes distal ureter dilatation known as a ureterocoele.

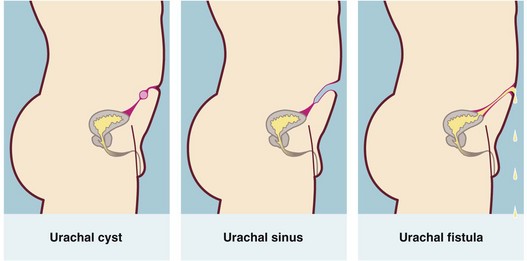

Fig. 39.3 Duplex systems

(a) Partial and total duplication. In a total duplex system (right), the ureter from the upper renal moiety may open into the urethra or vagina (i.e. wholly ectopic). Such an ectopic ureter causes continuous incontinence and presents early in life. Otherwise, it opens inferiorly in the bladder (centre). The orifice is often stenosed and a ureterocoele results (dilated lower end of ureter). Vesicoureteric reflux often occurs via the upper ureteric orifice back into the lower renal moiety.

(b) Duplication of the ureters on the right side; only one ureter can be seen passing as far as the bladder. The vesicoureteric junction is associated with a small, elongated ureterocoele (arrowed)

The ureter draining the lower moiety may have a defective distal antireflux mechanism, predisposing to infection and renal parenchymal damage. The typical IVU picture is of calyces that look like a ‘drooping daffodil’.

Renal cysts

Isolated renal parenchymal cysts are a common developmental abnormality and although rarely symptomatic, can be found in a fair proportion of the population in later life. They are usually recognised incidentally during imaging. Their importance lies in distinguishing them from solid tumours and hydatid cysts, which is usually easy with ultrasonography or CT scanning. Renal cysts can be simple or complex (containing blood, calcification or solid components). Occasionally simple cysts cause pain or swelling. For these, aspiration alone is of no value as the cysts rapidly refill. If intervention is required, cysts should be deroofed laparoscopically (in contrast to the treatment of polycystic disease).

Horseshoe kidney

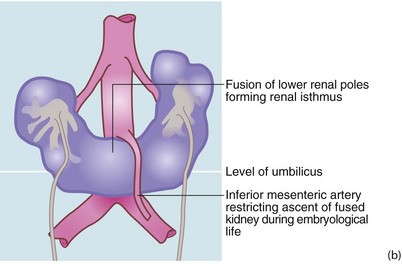

This abnormality is caused by embryological fusion of the two developing kidneys at their lower poles. Normal renal ascent in fetal life is prevented by the inferior mesenteric artery at the abdominal aorta, so the isthmus of the kidney comes to lie across the aorta at the third or fourth lumbar vertebral level. The condition is usually a chance finding on imaging (see Fig. 39.4) or else at abdominal aortic surgery, when it may cause serious operative difficulties. Horseshoe kidney is sometimes associated with pelviureteric junction obstruction, the symptoms of which may prompt the diagnosis. Occasionally, a horseshoe kidney first causes problems during pregnancy.

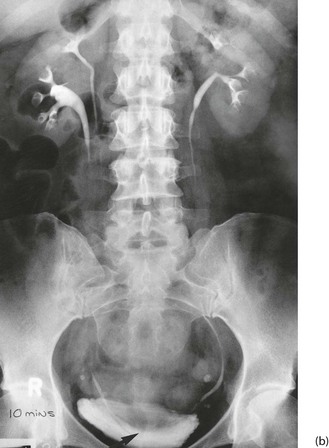

Fig. 39.4 Horseshoe kidney

Horseshoe kidney shown on IVU from a 51-year-old woman with recurrent urinary tract stones; the pelvicalyceal systems are oriented obliquely and converge inferiorly because the isthmus is stretched over the vertebral column. Each pelvis and ureter is more medially placed than normal and the whole renal mass lies much lower than would normal kidneys. The isthmus of a horseshoe kidney can rarely be demonstrated by IVU or ultrasound but can easily be imagined in this image

Renal ectopia and other renal abnormalities

Other renal abnormalities may be found incidentally. These include ectopic kidneys (see Fig. 39.5), rotational abnormalities, unilateral agenesis, aplasia or hyperplasia. These abnormalities may confuse the diagnosis and sometimes result in surgical mishap, e.g. excision of a pelvic kidney mistaken for an ovarian tumour. Note that transplanted kidneys are usually deliberately sited in the iliac fossa.

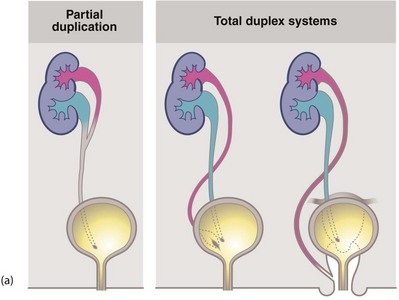

Fig. 39.5 Ectopic kidneys

(a) A 48-year-old woman with recurrent urinary tract infections; IVU shows abnormal pelvicalyceal systems P of bilateral pelvic kidneys.

(b) Right pelvic kidney discovered incidentally during arteriography for severe claudication. Its blood supply can be seen to arise from the distal aorta and iliac artery. The patient needed an aortofemoral bypass but when faced with the technical difficulties, agreed to conservative management of her claudication

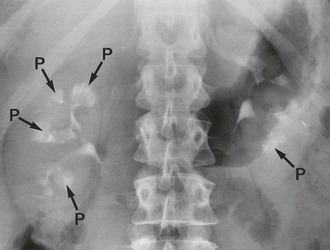

Urachal abnormalities (see Fig. 39.6)

During fetal development, the urogenital sinus communicates with the allantois via the urachus. Occasionally, this tract persists as a fistula between bladder and umbilicus. Sometimes the fistula does not open until adulthood. Similarly, a remnant may form a blind urachal sinus that opens at the umbilicus or result in a urachal cyst in the lower abdominal midline. These structural abnormalities may then become infected. Very rarely, an adenocarcinoma develops in a urachal remnant in the bladder vault or elsewhere.

Diseases secondarily involving the urinary tract

Introduction

Abdominal disorders such as tumours, inflammatory bowel disease, aneurysms and retroperitoneal fibrosis may secondarily involve the urinary tract, as may iatrogenic (surgical) damage. Any of these may affect the urinary tract by obstructing one or both ureters or occasionally by causing a fistula between bowel and urinary tract. Obstruction of one ureter alone may not be symptomatic although it may cause loin pain or predispose to infection; bilateral involvement usually presents with acute or chronic renal insufficiency.

Tumours and inflammatory causes

Of tumours outside the urinary tract, advanced carcinoma of the uterine cervix most commonly produces bilateral ureteric obstruction because of its close relationship to the ureters. This cancer may also ulcerate anteriorly into the bladder causing a vesico-vaginal fistula. This anatomical closeness also makes ureters vulnerable to trauma even at uncomplicated hysterectomy. Abdominal and particularly laparoscopic-assisted hysterectomy can be associated with damage to the ureter, causing stenosis and hydronephrosis or a uretero-vaginal fistula. An iatrogenic vesico-vaginal fistula can also be produced. Although carcinoma of the ascending or rectosigmoid colon rarely obstructs the right or left ureter respectively, most ureteric damage in relation to large bowel cancer results from colectomy operations.

Inflammatory disease that involves bowel serosa may extend to involve ureters and bladder and cause possible fistula formation. This is important in Crohn's disease and diverticular disease. A fistula between bowel and urinary tract presents as severe urinary infection, often with pneumaturia or faecuria.

An expanding abdominal mass can compress one or both ureters and cause symptoms from partial obstruction; sometimes aortoiliac aneurysms are responsible. An ‘inflammatory’ aneurysm near a ureter is likely to cause obstruction. This variant occurs in about 5% of aortic aneurysms. The cause is unknown but the effect is to produce retroperitoneal fibrosis across the anterior surface of the aneurysm. A much more common cause of ureteric dilatation is pregnancy, in which bilateral megaureter results from the effects of progestogens. The main significance of bilateral megaureter in pregnancy is predisposition to upper renal tract infection. Thus, significant bacteriuria in pregnancy, symptomatic or not, should be treated with antibiotics. Retention of urine can be caused by a pelvic mass such as a pregnancy of around 14 weeks or an ovarian lesion of similar size.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF)

This relatively rare and obscure condition is characterised by progressive, intense fibrosis of the connective tissue lying posterior to the peritoneal cavity. About 50% of cases are caused by retroperitoneal spread of malignant disease. In the remainder, the cause is unknown in many (i.e. idiopathic), but some rarely used drugs such as methysergide can induce the condition or it may be associated with an inflammatory aortic aneurysm. Retroperitoneal fibrosis sometimes causes hypertension via its effect on the kidneys.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis compresses both ureters, causing bilateral hydronephrosis and eventually renal failure. It can also be associated with inferior vena cava obstruction. Diagnosis is usually made on IVU or CT scanning which shows bilateral hydronephrosis (see Fig. 39.7). The fibrotic process also draws the ureters closer together in the midline. The ESR is characteristically elevated.

Fig. 39.7 Retroperitoneal fibrosis

This man of 62 presented with back pain. The IVU shows bilateral hydronephrosis due to ureteric compression; note how the ureters are tapered and characteristically drawn medially by the fibrotic process

Treatment usually involves a trial of high-dose steroids and insertion of double-J stents to maintain upper tract function whilst awaiting improvement. Surprisingly, ureters compressed by retroperitoneal fibrosis can usually be catheterised with ease. If medical treatment fails, the next step is usually dissection of the ureters from the retroperitoneal tissue (ureterolysis), which are resited within the peritoneal cavity in an attempt to prevent recurrent obstruction. A biopsy of the retroperitoneal tissue should be taken to exclude malignancy and confirm the diagnosis. If obstruction recurs, corticosteroid therapy may suppress the condition. Aortic grafting is indicated if a substantial aneurysm is present.