Fluid and electrolyte balance

Fluid and electrolyte replacement can be conveniently divided into:

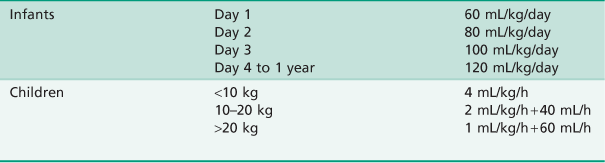

• Maintenance replacement – The fluid and electrolyte losses occur during a normal day. These values are modified by other factors such as patient and environmental temperatures, age weight and metabolic rate.

• Deficit replacement – To replace any existing or ongoing abnormal losses such as dehydration from vomiting or diarrhoea and blood loss.

Maintenance replacement

The need for water and electrolytes is a function of the metabolic rate as they are substrates for metabolism. Thus, the younger the child, the higher the metabolic rate on a weight basis and the higher the turnover of water and electrolytes.

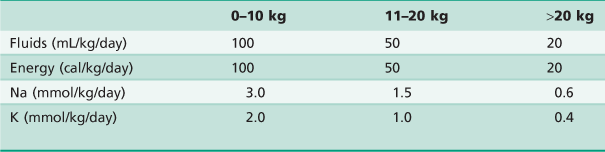

Electrolyte requirements

Normal electrolyte requirements are shown in Table A.9.

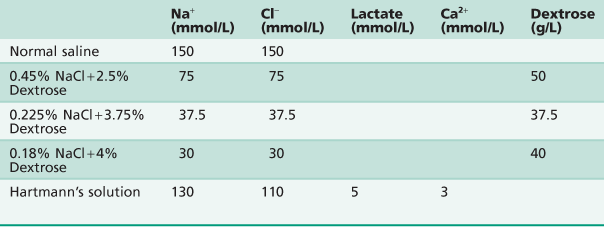

A total of 0.225% sodium chloride + 3.75% dextrose at normal maintenance rates will supply adequate sodium and chloride; potassium should only be added to intravenous fluids if replacement is to continue for more than 24 h and adequate urine output is present. However, 0.45% saline + 5% dextrose is now accepted as routine replacement fluid in many centres, as the risk of hyponatraemia is reduced in patients with stress related ADH release. Infants under 3 months of age will also require supplements of dextrose if they are to fast for longer than 4–6 h.

Fluid deficit

Fluid deficit is usually expressed as a percentage of body weight. This allows for easy calculation of replacement fluids. Fluid imbalance may be as a result of any of the following:

Assessment of deficit

Deficit assessment is difficult even for experienced paediatricians. Some idea of the deficit can be gained from the history of the abnormal loss. For example:

Dehydration is generally assessed by estimating weight loss.

Replacement of deficit

Usually the deficit is replaced with the fluid that most closely approximates the fluid that has been lost. Replacement therapy is aimed at restoring the fluid compartments in the following order. If there is significant loss of blood volume, then this must be replaced as rapidly as is safely possible to preserve brain, heart and kidney perfusion.

Calculation of deficit

Deficit (mL) = % dehydration × weight (kg) × 10.

Examples

Mild dehydration

Where there is no circulatory compromise, the loss will be water and electrolytes from all body compartments. This can be replaced with dextrose saline solution over many hours.

Severe dehydration

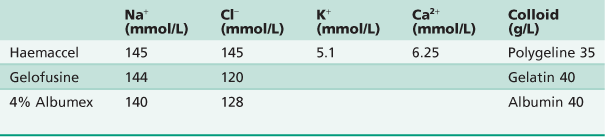

There is loss of intracellular, interstitial and most importantly, blood volume. The priority is to rapidly restore blood volume and with that, cardiac output with colloid or blood (10–20 mL/kg over 20–30 min) or saline solutions (20–40 mL/kg) to allow adequate vital organ perfusion. After this is achieved, electrolyte and water deficits should be replaced as calculated with dextrose saline solutions over a longer period of time (several hours to 24 h).

Severe blood loss

In cases of trauma or bleeding, there will initially be loss of blood volume. This is treated in the same way as above, i.e. restoring circulating blood volume with colloids or blood and reassessment of losses. If the blood loss is unknown, then initial therapy is to start with 20 mL/kg over 10–20 min and then reassess. If the blood pressure has returned to normal and fallen again or has not responded to this initial bolus, then a repeat of the initial bolus of fluid is indicated, followed by reassessment. The signs of adequate fluid replacement without the aid of central venous pressure or urine output measurement are the return to normal values of blood pressure and heart rate without the need for further boluses of fluid.

Notes on rehydration

The above guidelines apply to previously healthy children. Those children with cardiac disease or significant systemic disease require intensive intravascular monitoring in a paediatric intensive care unit.

• Constant reassessment of fluid therapy is essential throughout replacement.

• Measurement of electrolytes is essential in the replacement of greater than moderate deficits and applies especially to potassium.

• Measurement of acid–base status with arterial blood gases is often necessary, as fluid deficit causes organ hypoperfusion and subsequent metabolic acidosis. This will usually correct itself with correction of blood volume and cardiac output over many hours.

• Fluid balance and acid–base disturbances are often very complex and life-threatening; if there is any doubt as to management, then specialist paediatric or anaesthetic advice should be sought.