Antibiotic prophylaxis protocols for the prevention of infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is a rare and potentially life-threatening disease with a reported annual incidence of 0.3 per 100 000 children in Western countries, which has remained unchanged in the past 40 years. Despite the advent of antibiotics, infective endocarditis still has a high rate of mortality, up to 25%, and is associated with significant morbidity.

Approved antibiotic prophylaxis regimens are still recommended for potentially at-risk patients receiving dental treatment, as there is evidence, predominantly based on animal models, that suggests infective endocarditis may follow dental treatment in susceptible patients. Recommendations differ from one institution to another and vary in different countries, and therefore it is the responsibility of clinicians to determine which guideline is the most suitable to their individual patient.

Pathogenesis

• Characterized by inflammation of the inner surface of the heart (endocardium).

• Generally due to bacterial infection.

• Most commonly affecting the heart valves.

• May also involve non-valvular areas.

• Implanted cardiac mechanical devices also affected, such as prosthetic heart valves.

Three conditions need to be met for infective endocarditis to occur:

• Pre-existing damage to the heart valve surface.

• Bacteraemia, that is the introduction and circulation of bacteria in the bloodstream.

• Presence of bacteria of sufficient virulence to evade the body’s innate defences, to attach, colonize, invade and so cause infection of the damaged heart valve surface.

Epidemiology

The at-risk population principally consists of those with:

• Rheumatic fever. Previously, the commonest cause of heart valve damage was childhood rheumatic fever. Improved sanitation and living conditions and the availability of antibiotics has significantly reduced the incidence of rheumatic fever. In those areas with social and economic deprivation, rheumatic heart valve disease is still prevalent.

• Prosthetic aorto-pulmonary shunts.

• Patients with a previous history of endocarditis.

• Immunocompromised patients with long-term central venous lines.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

It has been long recognized that invasive dental procedures, typically extractions, cause an acute, substantive bacteraemia. However, there are increasing concerns regarding the cumulative bacteraemia associated with the activities of daily living, such as chewing or tooth brushing, particularly in the presence of chronic dental disease. In spite of this, infective endocarditis is uncommon.

In an attempt to reduce the significant mortality and morbidity rates seen with infective endocarditis, numerous protocols recommending the prophylactic use of antibiotics have been published. Two of the most authoritative bodies, namely, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) have recently published significantly revised protocols for antibiotic prophylaxis for susceptible patients.

Cardiac conditions associated with the highest risk of adverse outcome from endocarditis for which prophylaxis with dental procedures is recommended:

• Previous history of infective endocarditis.

• Prosthetic cardiac valve replacement.

• Cardiac transplant recipients who develop valvulopathy.

• Specified congenital heart disease involving the presence or placement of shunts or conduits:

• Unrepaired cyanotic shunts, including palliative shunts or conduits.

• Completely repaired congenital heart defects with prosthetic material or device for at least 6 months after the procedure.

• Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects or adjacent to a site of prosthetic patch or material.

At-risk dental procedures

Antibiotic prophylaxis is now indicated for any and all dental procedures that involve manipulation of the gingival, mucosal or periapical tissues that is likely to cause bleeding (i.e. extractions, scaling, root canal instrumentation beyond the apex). The following procedures and events do not need prophylaxis:

Guidelines for clinicians

Past and current medical history

It is essential that the patient’s medical status and history be assessed with respect to their cardiac problem. Consultation with the patient’s doctor or cardiologist is essential. Dentists should be prepared to discuss with the treating doctor any issues surrounding the dental care of their patient.

Considerations in selecting appropriate antibiotics

• Anaphylaxis must be considered a risk in all patients taking any antibiotic, but particularly with any of the penicillins.

• Does the patient have a convincing history of allergy to any of the recommended antibiotics?

• Is the patient on long-term antibiotics? Or have they recently been taking an antibiotic? Alternative agents should be used.

• Does the patient have impaired renal function that will necessitate dose modification?

• Is the patient able to accept oral medications? Is there a history of vomiting with oral antibiotics? If so, consider parenteral medication.

Treatment planning

• ‘Group’ together a number of invasive dental procedures to be done in the minimal number of appointments to reduce the need for repeated courses of antibiotics.

• The same antibiotic should not be prescribed within 14 days.

• Is a general anaesthetic indicated? Consideration should be given to completing all possible treatment in one appointment.

Recommendations for use of protocols for antibiotic prophylaxis

The authors do not make a recommendation about the efficacy of one particular protocol over another. There are problems associated with prophylaxis regimens in that no two sets of guidelines are the same. Less than 10% of patients with endocarditis have had a recent invasive dental procedure and there is no direct evidence in humans that antibiotic prophylaxis is effective. Currently, there is disagreement over the efficacy of different protocols as to which patients and what dental procedures should be covered. Please note that the current Australian Guidelines make special reference for the need to provide antibiotic prophylaxis for indigenous Australians who have a history of rheumatic fever. The AHA Guidelines still recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures in select patients thought to be at higher risk of infective endocarditis. In contrast, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) published revised guidelines for the UK in 2008. The major recommendation of this group is that antibiotic prophylaxis is NOT RECOMMENDED for patients at-risk of infective endocarditis, undergoing any type of dental procedures, including invasive dental procedures. The NICE guidelines contend that the greatest risk of infective endocarditis is from the cumulative, incidental daily bacteremia. In light of this, the NICE guidelines place greater emphasis on the provision and maintenance of optimal oral hygiene and dental health. Of interest, since the introduction of the revised guidelines, there has not been an increase in the incidence of infective endocarditis in the UK.

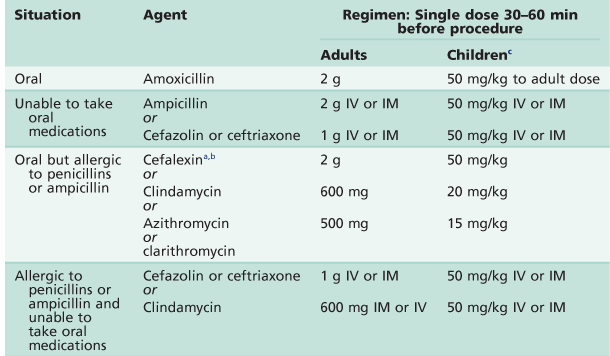

Table A.13

Current protocols for susceptible patients

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

aOr other first or second generation cephalosporin in equivalent adult or paediatric dose.

bCephalosporins should not be used in an individual with a history of anaphylaxis, angio-oedema or urticaria with penicillins or ampicillin.

cChild dose must not exceed adult dose.

After Wilson et al. 2007.

Other considerations

Further reading

1. Gould FK, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;57(6):1035–1042.

2. NICE. Clinical guideline 64 Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures. In: www.nice.org.uk/CG064; 2008.

3. Sroussi HY, Prabhu AR, Epstein JB. Which antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines for infective endocarditis should Canadian dentists follow? Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2007;73:401–405.

4. Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd. Oral and dental, Version 1. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2007; In: www.tg.com.au; 2007.

5. Thornhill MH, Dayer MJ, Forde JM, et al. Impact of the NICE guideline recommending cessation of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infective endocarditis: before and after study. British Medical Journal. 2011;342:d2392.

6. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis Guidelines from the American Heart Association Prevention of infective endocarditis: A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2007;138:739–760.