Child development, relationships and behaviour management

Richard P Widmer, Daniel W McNeil, Cheryl B McNeil and Linda Hayes-Cameron

Promoting positive behaviour among children, adolescents and their caregivers in the dental surgery

This section is a practical guide for specific modes of interacting in the dental environment which can help produce positive and adherent behaviours in child and adolescent patients, as well as their parents and other caregivers (e.g. grandparents). These guidelines are based on principles and research findings from behavioural dentistry, as well as behavioural, developmental, child and paediatric psychology.

It is probably true for most of us that the meaning of our lives is centred on our personal relationships. These are the source of our sense of personal identity; they are the source of our emotional security or insecurity that might define us; they are the source of our greatest joys, of our deepest comforts but, of course, they are also the source of our most bitter disappointments. However, without personal relationships life for most of us would be meaningless. We might dream of escape to the proverbial ‘Desert Island’ but we wouldn’t want to stay there for more than an hour or two or possibly a week, because we would soon realize that the lifeblood of our lives is in our relationships. That is where we get all the rich material for coping with life (Hugh MacKay, ABC radio 26 March 2010). So at home and at work, we need to nurture our relationships constantly. In dentistry, this is particularly relevant, as we are working intimately, not only with those we are caring for, but also with their carers and indeed the entire Dental Team. We spend a great deal of our waking hours ‘at work’, which we want to enjoy as much as possible and so our relationships become crucial and can be used to positively affect the behaviour of the child in the dental environment.

Much has been written about management of problem behaviour among children receiving oral healthcare, with a focus on the use of various techniques. This guide, however, emphasizes specific, simple methods that can be used with children and adolescents to enhance their comfort and cooperation. The general idea is to use finesse instead of trying to achieve absolute behavioural control. Since a sense of lack of control is one of the major components of anxiety and fear (along with a lack of predictability), using methods that are encouraging rather than demanding can go a long way in promoting comfort in the dental environment.

Dentists, dental hygienists and dental therapists are integral members of the healthcare team for children and adolescents and must have an awareness of practical methods of behaviour management that are based on knowledge of psychological principles and stages of growth and development. The adage that ‘children are not small adults’ promotes the idea of special knowledge and behaviours that are important in caring for younger dental patients. Oral health professionals must have a knowledge base in child and adolescent medicine, as well as in social, emotional and cultural factors affecting the health and behaviour of this age group.

It is imperative that dental appointments in infancy, childhood and adolescence are positive, as research clearly shows that early experiences have strong effects on whether dental advice and treatment is sought in adulthood. Having a rapport with the parents/caregivers (e.g. grandparents) is essential, as they typically are the most influential people in the child’s life.

Child behaviour and development

Working with children is, of course, different from working with adults, therefore, it is essential to be familiar with age-appropriate skills and functioning, and development. Infants, children and adolescents are undergoing progressive changes in cognitive, receptive and expressive language, fine and gross motor ability, and social/emotional development. Each child is unique and may develop at varying rates relative to their same-aged peers, For example, one child may present with strong motor skills but less well-developed language, while this may be the opposite for another same-age peer.

Developmental milestones and issues

There are two essential needs that remain constant from birth to adulthood: the desire to feel important and having an emotional connection with others. Oral health professionals who are aware of their patient’s age-appropriate development and needs can use that information to develop a rapport with the child and have appropriate expectations of the behaviour of that particular child in the dental setting.

General developmental milestones and child behaviour

Age 6–8 months

• By 6–8 months, infants are discovering new ways to share and express their curiosity, joy, frustration and fear within their world. Babies can shift their attention while keeping in mind the object on which they were focusing. They can look at a ‘teddy bear’ and be delighted by it, then turn to look at the parents to share those feelings.

• By 8 months, babies are beginning to crawl and discover their surroundings, learning to distinguish differences in their world and people.

• Mobility sets the stage for the first significant appearance of fear. Stranger awareness begins at this time.

• Understanding of spoken words and non-verbal communication (receptive language) develops at a much greater rate than expressive language.

• The infant learns to ‘social reference’, where he/she shows interest in an object or person and then turns to the parents for emotional feedback. The infant is able to read the parent’s/caregiver’s facial expression, tone of voice and words, to understand the concept of a particular danger or safety.

Dental implications

It is generally accepted that teething has the potential to cause local irritation, however, there is no accepted evidence connecting the systemic symptoms, such as diarrhoea, flushed cheeks and fever, to teething. It is important to seek medical advice if an infant has persistent febrile illness.

Age 9–12 months

• By 9 months, two-way conversations about feelings are now possible. Infants become aware of the possibility of others sharing their thoughts and feelings. Understanding and labelling the infant’s feelings and experiences can help with relationship building, acceptance and trust.

• Object constancy or permanence is developing in which infants begin to realize that objects and people still exist even when out of sight (e.g. repeatedly throwing the spoon off the high chair and it magically reappearing).

• Separation anxiety is a consequence of this stage and may continue in varying degrees until 18 months.

Dental implications

Children’s behaviour is a function of their learning and development, and so it is reasonable to expect that their behaviour in the dental environment will also vary.

• The child has limited ability to understand dental procedures. Nonetheless, with a sensitivity to the child’s normal emotional development and play expectations, even without cooperation, an oral examination and some treatment can often be accomplished without sedation.

• Good rapport with the parents is required, as the dentist can educate the parent in the importance of sending positive and appropriate feedback to the infant/child about the dental experience.

Age 1–3 years (Toddler years – egocentric)

• Infants begin to develop a sense of self and explore their autonomy. They may become non-compliant for the first time, as they practise asserting themselves, trying to establish themselves as independent and avoiding situations that make them feel out of control and with a limited sense of self.

• Language develops and ‘No’ becomes a favourite in their repertoire of words.

• Sharing and cooperative play is meaningless at this stage, as the ‘toddler rules of ownership’ outweigh all concepts, such as: If I see it it’s mine. If it’s yours and I want it, it’s mine. If it’s mine, it’s mine and mine only!

Dental implications

• In the dental room, the clinician may identify an object of particular ownership such as a doll or another toy, and praise the child for taking good care of it rather than trying to remove it.

• Giving toddlers lots of little choices (a choice of two at any time) will assist in enhancing their sense of self and importance, resulting in greater cooperation.

• Preferences for ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ objects is common at this age: many toddler boys show interest in cars, trains, the colour blue and other boys, while many toddler girls show interest in dolls, fairy dresses, the colour pink and other young girls, for example. Play remains solitary, however, and is ‘parallel play’ to their peers.

• The ability to communicate varies according to the level of vocabulary development, which is expected to be limited. Thus, the difficulty in communication puts the child in a ‘pre-cooperative’ stage.

• These children are too young to be reached by words alone, and shyness may mean that the child must be allowed to handle and touch objects to understand their meaning.

• Children of this age typically should be accompanied by a parent.

Age 3 years

• By this age, children are less egocentric and like to please adults.

• They have very active imaginations and like stories; back-and-forth communication is possible, and children at this age typically have the capacity for some reasoning.

• In times of stress, they will turn to a parent and not accept a stranger’s explanation. Typically, these children feel more secure if a parent is allowed to remain with them until they have become familiar with the dental professionals. Then a positive approach can be adopted.

Age 4–5 (early childhood years)

• By this age, children are exploring new environments and relationships in their world. They prefer one-on-one friendships, as more than one is difficult to manage. Once at school, however, they have to learn to sit quietly in groups and pay attention. Further development of social skills and regulation of emotions is occurring while mixing with their peers.

• These children listen with interest and respond well to verbal directions. They have lively minds and may be great talkers who are prone to exaggeration. In addition, they will participate well in small social groups.

• 4-year-old children are extremely creative, as fantasy and imaginary play allows them to work through confounding problems, emotions and the stressors of daily life. Therefore, pretend play can open the door to a young child’s thoughts and worries and provide the dentist with valuable information. Showing great interest, listening and reflecting back to the child what they just said or taking on the role of another toy in conversation with them, will encourage them to explore further.

Dental implications

• At this age, these children can be cooperative patients, but some may be defiant and try to impose their views and opinions. They are familiar with and respond well to ‘thank you’ and ‘please’.

• Promotion of autonomy and the development of self-esteem by allowing decision-making and choices in their treatment, and encouraging them to take responsibility for tasks such as manoeuvring the dental chair, is important.

• Children at this age usually have no fear of leaving their parents for a dental appointment because they have no fear of new experiences. They take pride in their possessions, and comments about clothing can be effectively used to establish communication and develop a rapport. By this age, children usually have relinquished comfort objects such as thumbs and ‘security blankets’.

Age 6–8 years

• By 6 years, children are established at school and are moving away from the security of the family.

• They are increasingly independent of parents and will play without their parents being in close proximity.

• For some children, this transition may cause considerable anxiety with outbursts of screaming, temper tantrums and even striking parents. Furthermore, some will exhibit marked increase in fear responses.

Dental implications

• This age may be an ideal time to help the child and parent/caregiver move from the parent/caregiver being in the surgery to the child being able to go back alone from the waiting room to the surgery.

• The increased tendency toward fearfulness prompts special care in working with children at this age, accepting that new fear(s) may develop, even if the child has been a prior patient who earlier was comfortable in the dental setting.

Age 8–12 years (the middle years)

• At this age, children are part of larger social groups and are strongly influenced by them. They notice who is accepted and who is excluded from groups. With this comes the growing concern of embarrassment, which they will avoid at all costs. While parents might wish for them to become leaders, they appropriately become followers, as this is perceived as healthier and safer.

• As a consequence, children learn to hide their feelings and thoughts at this time and adopt a ‘cool’ attitude.

• Intellect becomes more important as they develop cognitively and begin to reason. The pre-teenager becomes concerned with what is moral and just and becomes more literal (e.g., a parent asks: ‘Pick up your clothes’. The child picks them up and places them back down stating, ‘You didn’t tell me where to put them!’).

Dental implications

• Be cautious to not embarrass the child through criticism of his/her self-care (e.g. toothbrushing).

• Be patient in not expecting the child to freely share information without considerable rapport-building.

• Given the developing capacity to reason, children in this age range may respond well to explanations about the need to engage in toothbrushing and flossing on their own, without parental prompting.

Adolescence

• The adolescent is faced with solving major questions such as: Who am I? Who am I becoming? Whom should I be? With such tasks in mind, it is understandable that teenagers are often perceived as self-absorbed, excluding themselves from family and to some degree, their peers. Many interactions with the teenager tend to result in a narcissistic view of any situation.

• Adolescents are on a journey of self-discovery and, not unlike the toddler, are looking for greater autonomy, such as experimenting with new identities, realities and self-concepts, all of which are healthy. Experimentation and use of tobacco and other substances is common.

• Adolescents typically believe they are invulnerable, and that they will not encounter adverse results from their actions. They do not expect, for example, that negative health outcomes will result from tobacco use as ‘other people’ get addicted and only ‘old people’ have health problems.

• Appearance becomes increasingly important during the teenage years.

• Teenagers often feel that their experiences are unique, so listening with an open mind, providing independence as would be done with an adult and supporting them in reaching their goals (within safety limits), will earn trust and cooperation.

• Greater rapport is gained when the dentist adopts a non-judgemental, non-preaching and respectful approach towards the teenager.

Dental implications

• Treating the teenager as his or her own person, independent from the parent/caregiver, typically will be well received.

• Taking some time to talk about non-dental topics in an ‘adult’ way may be a good way to develop rapport.

• Emphasizing the importance of self-dental care to maintain their smile may be a way to ‘reach’ adolescents in terms of preventive behaviours.

Understanding child temperament

There has been a longstanding debate in the literature on child development about the degree to which a child’s development is influenced by ‘nature’ versus ‘nurture’. Studies suggest that children do indeed enter the world with a characteristic temperament or personality that stays with them to some degree, for the rest of their life. Thomas and Chess (1977) suggested that there are three basic temperaments that influence later personality:

Easy temperament

These children have a positive mood, regular bodily functions, are adaptable and flexible and have a positive approach to change or new situations.

Difficult temperament

These children are more irritable and intense. They have irregular body functions and take some time to develop feed, play, sleep patterns and routines. They have difficulty with new situations and adapting to change and tend to withdraw in social settings.

Slow to warm-up temperament

These children have a shy disposition and a low activity level. Initially, they are slower to adapt to new situations but once they are comfortable with their environment they begin to engage.

Approximately 65% of infants can fit into one of these three categories. The remainder have a mixture of traits.

Dental implications of child temperament

Dentists working with children must use different approaches and techniques, depending on the personality type of the child. Whereas an easy temperament child may be flexible enough to handle a quick change in plan, a slow to warm-up child may need to be given a longer time to adjust. Difficult children respond best to a dentist who provides a great deal of structure in a sensitive but confident manner. The slow to warm-up child is best served by dental personnel who are calm, patient and encouraging (without being demanding).

Use of verbal and non-verbal communication to promote positive behaviour in children

The following principles are some of the important considerations in positive communication with children and their families.

• Show respect for the child and his/her feelings and interests.

• Show interest in the child as an individual. Find our his/her preferred name (e.g., nickname if any) and use it frequently in speaking with the child (and caregiver).

• Share ‘free information’, as much as the child/caregiver seems to want and to be able to handle.

• Give well-stated instructions (e.g., ‘Please open your mouth now’, instead of questions, such as, ‘Would you like to open your mouth now?’). Tell the child kindly what he/she NEEDS TO DO, not what they should NOT do.

• Communicate at the child’s level, both physically (Figure 2.1) and cognitively/emotionally.

Figure 2.1 (A) Giving children control in the dental surgery. (B) It is essential to listen to your patient. A prearranged signal of a hand raised tells the clinician that the procedure is uncomfortable. This gives the child some control over what is happening without interfering with the procedure.

• Focus on the positive aspects of a child’s (and parent’s) behaviours. In most situations, ignore negative behaviours.

• Avoid stereotyping and making assumptions about children (e.g. that boys are interested only in sports; that young girls are interested in dolls).

Physical structuring and timing during the dental visit

Setting the stage for positive behaviour

In addition to communications from the dentist and dental staff, many aspects of the dental situation can be arranged in such a way that promote positive reactions in infants, children and adolescents. McNeil and Hembree-Kigin (2010) describe PRIDE skills, modified here for relevance to the dental situation, which is a conceptualization that can help prompt members of the dental team to structure their behaviour with children and teenagers. This approach is not to discourage spontaneity with youngsters, which can be so important in working positively with ‘kids’, but may provide a way for adults to think about including skills as part of their repertoire with children. In fact, the final point of the PRIDE skills is Enthusiasm, which speaks of communicating joy, spontaneous fun and action to youth.

PRIDE

• Praise: These ‘social reinforcers’ can be either ‘labelled’ or ‘unlabelled’. Labelled praises (e.g. ‘That’s a great job keeping your mouth open, Jane!’) typically are more effective at managing behaviour than unlabelled praises (e.g. ‘Well done, Jane!’).

• Reflection: Such phrases are a demonstration of the dentist listening to the child, and can involve a simple repeating of some of the child’s words, perhaps with embellishment.

• Inquire: These questions involve asking a child for information, or otherwise prompting him or her to reply (‘I’m wondering how you feel about coming to see me today?’). Open-ended questions typically produce more information and promote a more positive interview atmosphere, relative to closed-ended questions that can be answered with a Yes or No or a simple fact. Question-asking typically is greatly over-used by adults with children, and should instead be used judiciously.

• Describe: These statements focus on the child’s behaviour, and portraying the child’s actions, typically in a positive light (e.g. ‘Now you’re keeping your mouth open so nicely, and letting your feet and legs be still’.).

• Enthusiasm: There is a time for animation and play on the part of the dentist and dental team, and a time for more reserved professionalism. Particularly with younger children in a dental environment, enthusiasm on the part of the dentist and team is often needed to combat the negative images of dental care portrayed in the media, by peers and sometimes by parents and other caregivers.

Use of these PRIDE skills will be well received by children and youth, and can help make the dental appointment reinforcing and enjoyable. PRIDE skills, however, should not be used in some automaton fashion, but rather flexibly and in concert with the dental professional’s own personality and the procedures at hand. Not only are these interpersonal communication skills essential, but the physical and structural aspects of the dental appointment are also crucial.

Practical guidelines for physical and social aspects of the dental surgery

• Everyone in the surgery (dentist, auxiliary, parent) should transmit positive, comforting expectations to the patient.

• Use stimulating visual distracters in the surgery (child and adolescent-oriented posters).

• Have age-appropriate materials (safe toys, magazines) in the waiting room. Include materials for parents.

• Have toys available for younger children as distracters or tangible rewards.

• Greet the child in the waiting room without a mask and not wearing surgical garb. Use the child’s preferred name. Smile at the child! Depending on the child’s height and your height, you may wish to squat in greeting him/her, to be at eye level.

• Pace procedures during the appointment, based on how the patient is coping, so that they are neither rushed nor bored. Periodically ask how he or she is coping with the appointment, sometimes using closed-ended (e.g. ‘Are you doing OK?’) and sometimes open-ended questions.

• Inform and discuss with parent/caregiver before the appointment and at the end.

• Include children, and especially adolescents, in the decision-making and practicalities of treatment.

• Provide information in advance about the procedures to be performed at the next appointment so that the child and parent/caregiver are prepared.

• Allowing a child a visit to the ‘treasure chest’ to get a tangible reward at the end of an appointment, finding some positive behaviour to reinforce (even if much of the child’s behaviour was challenging), can leave a child with positive memories of the dental experience.

• Structuring what is remembered about a dental appointment has been shown to be an important issue in how children perceive dental care. The oral health professional may wish to provide a short summary statement after the ‘treasure chest’ visit, emphasizing certain (positive) parts of the dental visit (e.g. ‘Rickie, today you came in bravely and sat in the chair and kept your mouth open for a long time, even when you got a bit tired. Well done for keeping still for so long! Now, what was the best part of your visit today?’).

Presence or absence of family members in the surgery

• It is appropriate that a parent be present in the surgery to support their children during treatment, particularly in their younger years. Parents/caregivers can be coached by dental professionals regarding how to be most helpful during a visit.

• If a parent is unable or unwilling to provide appropriate support, then it may be more desirable for them to wait outside the surgery. It is important to note that parental access to their children should never be denied.

• When there are other siblings, who enjoy or readily cope with dental treatment, it often is helpful to use them as a model.

Transmission of emotion to the child or adolescent

• Children acquire some of their parents’ fear and anxiety about the dental treatment both in the dental environment and in the long term.

• Emotion is transferred from parents, siblings, dentist and auxiliaries to the child, whose emotional state also impacts on all of those persons. Dental staff who are calm and confident and use humour will promote positive experiences for their patients.

Physical proximity and touching

• Initially, work from the front, at eye level.

• Be aware of the child’s physical distance, i.e. ‘intimate zone’. This zone is approximately 45 cm, but varies in different cultures. By necessity, the dentist must ‘invade’ this space, but frequent stopping between procedures allows the child some time for coping.

• Touching the child can be used in non-private bodily regions, such as the lower arms and shoulders, to encourage, soothe or reward. The oral health professional should be attuned to the child’s reaction to such touching, however, and whether it is well received. There are wide cultural variations in the appropriateness of such touching, both in terms of the child’s background, as well as that of the oral health professional.

Stimulating and distracting objects and situations (Figure 2.2)

• Be aware of popular culture. In some settings, it is possible to have different areas of the surgery orientated to particular patient age ranges.

• One area might include puppets and pictures of colourful cartoon characters for children up to 8 years.

• For older children, have wall posters of pop groups.

• Adolescents, like adults, are best treated in a modern, friendly environment.

• In some settings, popular electronic games and videos are appropriate.

• Fish tanks provide interesting stimulation for children of all ages, as well as adults.

Greetings in the waiting room

• It is ideal, particularly in initial meetings, for the dentist to greet the child and parent/caregiver in the waiting area.

• An interview room or non-surgical environment is useful for new patients (Figures 2.3–2.5).

Talking with parents

It is helpful for the dentist to have a positive relationship with both children and their parents. Keep parents well informed. While asking personal information, always remember to involve the child in the discussion when appropriate. Be prepared to separate the child from the parent to discuss more sensitive issues if necessary. The chairside assistant can be asked to occupy the child during this discussion.

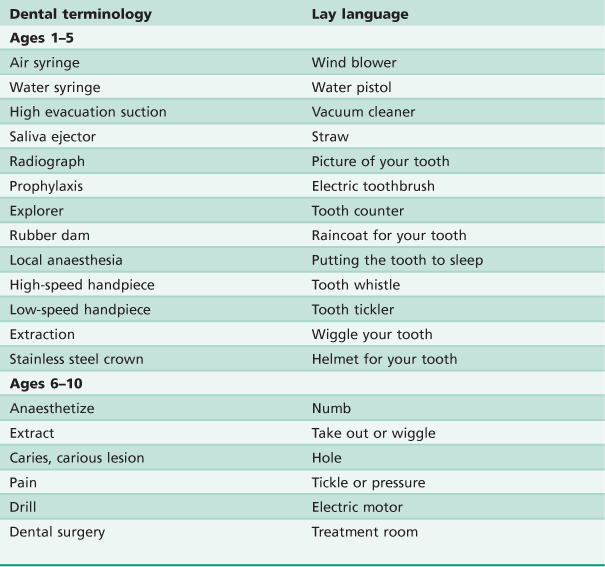

Talking with children and adolescents

Children, like adults, typically respond best if they are treated as individuals, somehow special to the provider. Consequently, using the child’s name to refer to him or her, and repeating it in conversation periodically during the dental appointment, is helpful in producing a positive environment and in capturing and maintaining the child’s attention. It usually helpful for the dentist and members of the dental team to speak with (not at) the child at the child’s level, both physically and psychologically. Dental jargon typically is best avoided with most patients, but particularly with children. Table 2.1 suggests terminology that might be used with younger patients. Of course, use of these terms should be at a developmentally appropriate level for the child. Some mid- and older adolescents, for example, may actually respond well to learning dental jargon, as it gives them a sense of being cognitively advanced.

Special arrangements for first-time dental visits

Certain steps are appropriate for an initial visit. In general, the pace of a first appointment is much slower.

• Use pre-appointment letters giving information about the visit that also includes photographs of the rooms and what might be expected of the child and parent.

The emphasis is on educating the child, promoting comfort and allowing the visit to be exciting and fun. Relatively simple and less invasive procedures are preferred. Introducing the child to the office, staff and equipment and pointing out posters and other materials of interest in the treatment room can be helpful.

Behavioural methods for reducing fear and pain sensitivity

Table 2.2 gives eight methods that can be used across a variety of situations with children and adolescents of all ages. The particular uses depend on the patient’s developmental age and personality, as well as on a variety of other factors such as the quality and depth of the dentist’s relationship with the child or adolescent.

Table 2.2

Behavioural methods for reducing anxiety

| Tell–show–do | Informing, then demonstrating, and finally performing part of a procedure |

| Playful humour | Using fun labels and suggesting use of imagination |

| Distraction | Ignoring and then directing attention away from a behaviour, thought or feeling, to something else |

| Positive reinforcement | Tangible or social reward in response to a desired behaviour |

| Modelling | Providing an example or demonstration about how to perform a behaviour |

| Shaping | Successive approximations to a desired behaviour |

| Fading | Providing external means to promote positive behaviour and then gradually removing the external control |

| Systematic desensitization | Reducing anxiety by first presenting an object or situation that evokes little fear, then progressively introducing stimuli that are more fear-provoking |

Integrating behavioural and pharmacotherapeutic approaches

The behavioural principles and methods described above are used routinely, many in virtually every encounter with a youngster in a dental setting. When medications are needed for pain and/or anxiety control, or for sedation, sensitive behavioural approaches on the part of the oral health professional are particularly important. Using both medication alongside behavioural approaches may be the most effective way to deal with many clinical scenarios. In fact, behavioural approaches can and should be used to prepare phobia patients, for example, prior to and after pharmacotherapy, as described by Milgrom and Heaton (2007).

Referring for possible mental health evaluation and care

When to refer

It is a role of the dental professional to refer a child or family when there seem to be significant emotional or psychological issues. Even when such problems do not interfere with dental treatment, it is the dentist’s role, as a member of the healthcare team, to identify possible psychopathologies and to refer for proper care. A sensitive conversation with the parents/caregivers regarding your concern for the child is essential prior to making the referral.

Common reasons for referring a child or adolescent for mental health concerns

• Evidence of abuse or neglect (e.g. bruises, broken teeth, cigarette burns, inappropriate clothing for weather, severe hygiene problems, untreated breaks or sprains).

• Extremes of behaviour, anxiety or emotion (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dental phobia).

• Neurological signs or symptoms (e.g., possible seizure activity, tics).

• Severe developmental or cognitive delay (e.g. possible learning disabilities, motor problems, feeding problems).

• Extremely poor parenting (e.g., sole use of excessive physical restraint and punishment).

Referral specialties

Referrals for mental health concerns should be made to psychologists, psychiatrists or social workers. In a hospital setting, it is possible to refer to one of the available departmental services. In a dentist’s private surgery, referrals can be made to professionals in private practice, community agencies or hospitals. The following guidelines are suggested when selecting a specialty for referral.

Psychologists

Refer in the case of abuse or neglect, extremes of behaviour, developmental or cognitive delay or extremely poor parenting. When there is a need for sophisticated cognitive, personality, neuropsychological and/or behavioural assessment, referral to a psychologist is best as standardized psychometric tests can be used. Psychologists also can provide individual child/adolescent, parent/child and/or family therapy to address problems in the child/adolescent and family system.

Psychiatrists

Refer when there are neurological signs or symptoms. When psychoactive medications may be needed, such as when a child demonstrates signs of psychosis, referral to a psychiatrist is most appropriate; similar to cases in which there are complicating medical factors.

Social workers

Refer for social problems, abuse or neglect. Referral to social workers is appropriate when there are existing social problems in the family that require mobilization of community resources. Social workers know about, and help patients to use available services in the community.

How to refer

It is acknowledged that suggesting mental healthcare to parents can be an anxiety-provoking task for the dentist. Nevertheless, it is essential that such referrals are made, because the dentist is in a unique role as a healthcare provider. If referrals are not made in a timely fashion, then a condition can progress and worsen.

• Speak to the parents/caregivers in a private setting, informing them of the signs or symptoms that are the cause for concern, without blaming or ascribing responsibility. When the parents understand the problems and your concern, referral to a specific professional or service can be made. It is often helpful to emphasize it is for the well-being of the child and the necessity to address the problem for their proper development.

• Ensure that the parents and the child or adolescent are aware of the referral and know the specialty of the referral. (It is not appropriate merely to describe the referral as ‘to a doctor who will help your child’.).

• Refer first to only one of the mental health specialties. If additional referral is necessary, it can be arranged by the first referral source. In making the referral, one can ask for feedback from the mental health professional after the appointment. If there is behavioural disruption in the surgery, the mental health professional may have recommendations for management once the child or family has been evaluated.

• Mental health concerns are considered private by many individuals. Given this desire for privacy, releases to exchange relevant information, signed by a parent or guardian and the child if of an age to understand it, are required. Such a form can be signed in the dental surgery and sent to the mental health professional, along with a request for feedback.

Further reading

1. McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin TL. Parent–child interaction therapy. second ed New York: Springer; 2010.

2. Milgrom P, Heaton LJ. Enhancing sedation treatment for the long term: Pre-treatment behavioural exposure. SAAD Digest. 2007;23:29–34.

3. Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. Oxford: Brunner/Mazel; 1977.