Pharmacological behaviour management

Eduardo A Alcaino, Jane McDonald, Michael G Cooper and Simrit Malhi

Pain management for children

The proper treatment of pain in children is often inadequate and involves misconceptions that:

• Children experience less pain than adults.

• Neonates do not feel or remember pain.

• Pain is character-building for children.

• Opioids are addictive and too dangerous in terms of respiratory distress.

Development of pain pathways

Even premature neonates have the physiological pathways and mediators to feel pain. The statement that infants and children do not experience pain, either partially or completely, is not physiologically valid.

Measurement of pain in children

There are individual circumstances for each child that affect how they respond to pain and, subsequently, how that pain will be assessed. These include:

Observation of non-verbal cues and behaviour is important. A quiet, withdrawn child may be in severe pain. Simple measures are there to measure pain in children of all ages.

Methods for paediatric pain assessment include

• Observer-based techniques which are useful in pre-verbal children, i.e. scales that measure blood pressure, crying, movement, agitation and verbal expression/body language.

• Self-reporting of pain is valid in children over 4–5 years of age.

• Children with severe developmental delay can be extremely difficult to assess regarding pain, even by their regular carers. Unusual changes in behaviour from normal may represent an expression of pain.

Analgesia prior to procedures (pre-emptive analgesia)

• Poor analgesia for an initial procedure in children can diminish the efficacy of analgesia for subsequent similar procedures.

• Consideration should be given to ensure adequate systemic and/or local analgesia prior to the commencement of a procedure. Appropriate time for absorption and effect should be allowed.

• A stronger analgesic may be required for the procedure with regular simple analgesics for the postoperative period.

Routes of administration

• Oral analgesia is the preferred route of administration in children. Absorption for most analgesics is generally rapid – within 30 min.

• Attention to formulation suitable to the individual child can help greatly with compliance, i.e. liquid versus tablets in younger children, pleasant taste.

• The rectal route of administration can be valuable in a child not tolerating oral fluids. Doses and time to peak levels may vary compared with oral preparations and are usually much longer. Peak levels after rectal paracetamol may take 90–120 min. Adequate explanation should be given and consent should be obtained for the rectal administration of a drug. This route is not used in an immunocompromised child due to the risk of infection or fissure formation.

• Parenteral paracetamol is now available.

• Intranasal or sublingual administration of opioids has been described as an alternative to injection, which avoids first pass metabolism by the liver.

• Repeated intramuscular injection should be avoided in children, they will often tolerate pain rather than have a painful injection. A subcutaneous cannula, inserted after using topical local anaesthetic cream (EMLA) can be used for repeated parenteral opioid analgesia.

• In obese children, the dosage given should be based on ideal body weight, which can be estimated as the 50th centile on an appropriate weight-for-age percentile chart.

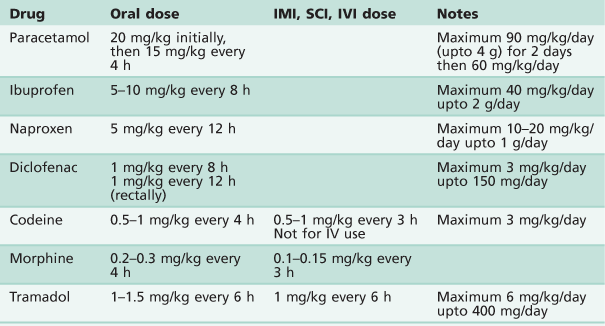

Analgesics

See Table 3.1.

Paracetamol

• Dosage 20 mg/kg orally, then 15 mg/kg every 4 h.

• 30 mg/kg rectally as a single dose.

• Maximum 24-hour dosage of 90 mg/kg (or 4 g) for 2 days, then 60 mg/kg per day by any route of administration.

• Useful as a pre-emptive analgesic.

• Intravenous paracetamol is available (10 mg/mL). The same dose is used and administered over 15 min.

• Take care with dosing, as many different strengths and preparations are available.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

• Effective alone after oral and dental procedures.

• May be used in conjunction with paracetamol.

• Have an opioid-sparing effect.

• Increased bleeding time due to inhibition of platelet aggregation.

• Useful analgesic once haemostasis has been achieved.

Tramadol

• Can be used for moderate pain in children over 12 years of age.

• A weak µ-opioid agonist and has two other analgesic mechanisms (increasing neuronal synaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine and inhibition of noradrenaline uptake).

• Avoid use in children with seizure disorders and those taking tricyclic or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants.

Discharge criteria

Many drugs that are used for combination sedation and analgesia in children have a long half-life of several hours. Discharge criteria should be used to assess that the child is well enough prior to discharge from a free-standing facility. Criteria should include:

Local anaesthesia

The use of local anaesthesia in paediatric dentistry varies significantly between countries and there are also individual preferences. Every clinician must be proficient at administering painless local anaesthesia. While it is the mainstay of our pain control for operative treatment, it also represents one of the greatest fears in our patients. Use of many of the non-pharmacological techniques described in the previous chapter may enable the dentist to deliver an injection without the child being aware. There are few patients, old or young, who are not genuinely afraid of injections, and there are obvious disadvantages in the physical size of the dental cartridge syringe.

Techniques and tips

• It makes sense NOT to hold the syringe in front of a young child to see. While it is essential not to lie to the child, distractions such as having the dental assistant talk, or use of the low velocity suction are useful.

• The use of topical anaesthetics is essential to create the optimal experience for the child. While a multitude of agents are available with different flavours and properties, newer anaesthetics such as EMLA® (Eutectic Mixture of Local Anaesthetic) penetrate deeper through the mucosa.

• Newer products such as electronic devices for slow injection techniques may replace more conventional techniques (The Wand®).

• The use of infiltration versus block injections in the mandible is also the subject of debate, and clinicians differ in their choice of technique. The approach of the needle to the mandibular foramen differs in younger children, as the angle of the mandible is more obtuse and a shorter needle (25 mm) may be sufficient. However, even with the best technique, a mandibular block injection may still be uncomfortable.

• Infiltration injections supplemented with intra-periodontal injection may be useful.

• Palatal anaesthesia is best achieved by slowly infiltrating through the inter-dental papilla after adequate labial or buccal anaesthesia to minimize discomfort to the child (Figure 3.1).

Need for local anaesthesia under sedation and general anaesthesia

Some form of pain control is required when invasive procedures are performed under any form of sedation (including inhalation sedation, oral sedation, etc.). However, the need for local anaesthetic under general anaesthesia is controversial. It is well recognized that a patient’s vital signs may change in response to painful stimuli (e.g. extraction), depending on the depth of anaesthesia. Local anaesthesia is not routinely used for extractions of primary teeth under general anaesthesia. Studies have observed that the child’s postoperative recovery is usually independent of the procedure performed, and preschool children waking after having a general anaesthetic can be more distressed by the sensation of numbness in the mouth. However, the use of local anaesthesia is recommended when removing permanent teeth, especially first permanent molars.

Complications with local anaesthesia

The most significant complication encountered is overdosage. Consequently, maximum doses (Table 3.2) need to be calculated according to weight and preferably written in the notes if more than just a short procedure is being performed. This clinical complication is highlighted in a paper that reviewed significant negative outcomes (death or neurological damage) in children due to local anaesthetic overdose (Goodson & Moore 1983).

Table 3.2

Maximum dosages for local anaesthetic solutions

| Anaesthetic agent | Maximum dose |

| 2% Lidocaine without vasoconstrictor | 3 mg/kg |

| 2% Lidocaine with 1 : 100 000 adrenaline | 7 mg/kg |

| 4% Prilocaine plain | 6 mg/kg |

| 4% Prilocaine with felypressin | 9 mg/kg |

| 0.5% Bupivacaine with 1 : 200 000 adrenaline | 2 mg/kg |

| 4% Articaine with adrenaline 1 : 100 000 (approximately 1.5 cartridge of 2.2 mL in 20 kg child) | 7 mg/kg |

Calculation of local anaesthetic dosage:

2% lidocaine = 20 mg/mL

2.2 mL/carpule = 44 mg/carpule

A 20 kg child (approximately 5 years old) can tolerate a maximum dose of 2% lidocaine with vasoconstrictor of:

7 mg/kg × 20 kg = 140 mg Equivalent of 3 carpules (6.6 mL)

Other complications include:

• Failure to adequately anaesthetize the area.

• Intravascular injection (inferior alveolar nerve blocks or, infiltration in the posterior maxillae, directly into the pterygoid venous plexus).

• Biting of the lower lip or tongue postoperatively.

• Facial nerve paralysis by injecting too far posteriorly into the parotid gland.

Consequently, adequate postoperative instructions to both children and parents are necessary to minimize these complications. In addition, inadequate local anaesthetic technique (inexperienced operator, fast delivery of solution and inadequate behaviour management) may jeopardize a successful outcome in an otherwise cooperative child. Allergic reactions to local anaesthetic solutions and needle breakage are rare in children.

The use of articaine with adrenaline has gained popularity recently. However, its safety and effectiveness in children under the age of 4 years has not been established. Finally, it is worth noting that there is significant evidence that inadequate local anaesthesia for initial procedures in young children may diminish the effect of adequate analgesia in subsequent procedures (Weisman et al. 1998).

Sedation in paediatric dentistry

The decision to sedate a child requires careful consideration by an experienced team. The choice of a particular technique, sedative agent and route of delivery should be made at a prior consultation appointment to determine the suitability of the child (and their parents) to a specific technique.

The use of any form of sedation in children presents added challenges to the clinician. During sedation, a child’s responses are more unpredictable than that of adults. Their proportionally smaller bodies are less tolerant to sedative agents and they may be easily over-sedated. Anatomically differences in the paediatric airways include:

• The vocal cords positioned higher and more anterior.

• The smallest portion of paediatric airway is at the level of the subglottis (below cords) at the level of the cricoid ring.

• Children have relatively larger tongue and epiglottis.

• Possible presence of large tonsillar/adenoid mass (Figure 3.2).

• Larger head to body size ratio in children.

• The mandible is less developed and retrognathic in younger children and infants.

• Children have smaller lung capacity and higher metabolic rate resulting in a smaller oxygen reserve. Hence children desaturate more quickly than adults.

Patient assessment

The preoperative assessment is among the most important factors when choosing a particular form of sedation. This assessment must include:

• A thorough medical and dental history (including current medications, previous hospitalization and past operations).

• Patient medical status (see ASA classification, below).

• History of recent respiratory illness or current infections.

• Assessment of the airway to determine suitability for conscious sedation or general anaesthesia (GA).

• Fasting requirements and the ability of the carer to comply with instructions.

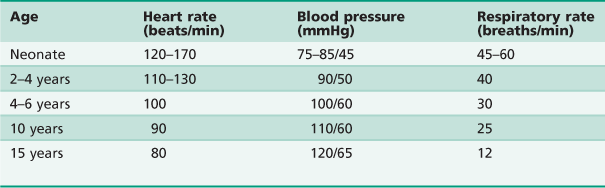

The clinician should be aware that children have resting vital signs that differ according to their age (Table 3.3).

The use of monitoring devices such as pulse oximetry is desirable for lighter sedation techniques and mandatory for moderate and deep sedation. While not currently mandated during relative analgesia, it is suggested that pulse oximetry should be used in all instances when a child is sedated. Sedation and anaesthesia is a continuum and any dentist who sedates children must be capable of resuscitating the patient from any level of sedation deeper than intended (Cote & Wilson 2006). Furthermore, regulations in each country, cultural and socioeconomic factors will determine which particular approach to sedation is chosen. Parental attitudes will also determine the appropriateness of a particular sedation technique.

Pharmacological agents may be administered in a number of ways but the more common routes of delivery include:

Inhalation sedation (relative analgesia or nitrous oxide sedation)

Nitrous oxide is a weak anaesthetic agent and is extremely useful in relieving anxiety. The use of nitrous oxide (N2O) offers the clinician a safe and relatively easy technique to use as an adjunct to clinical care. It can provide a gentle introduction to operative dentistry for the very anxious patient, or an ongoing aid for those who need assistance to accept routine operative dental care. It is effective for children who are anxious but cooperative. An uncooperative child will often not allow a mask or nasal hood to be placed over the nose. It also requires a child of sufficient maturity, age or understanding to help during the dental procedure. The acceptance of the mask is usually the biggest hurdle clinically, and often it is useful to lend the mask to the child prior to their treatment visit so they can practise and familiarize themselves with it. Alternatively, a trial appointment using inhalation sedation (IS) may be beneficial and help the clinician assess the correct concentrations to be used.

Contraindications

The only specific contraindication to IS in children is a blocked nose. The following conditions may significantly affect the efficacy of this technique and are best avoided:

Precautions in the use of nitrous oxide

Although nausea and vomiting may be a problem in some children, this is usually minimized with the routine use of rubber dam during restorative dentistry. Nausea is often brought about by fluctuating concentrations of N2O due to alternate mouth and nose breathing.

Administration of inhalation sedation

For the safe and effective use of inhalation sedation, it is necessary to have a complete understanding of the different stages of analgesia and anaesthesia with N2O, the delivery machine and circuits. This requires training in its administration and the careful monitoring of children. In particular, knowledge and training in emergency responses is also essential.

• The equipment must have the capacity to deliver 100% oxygen, and never less than 30% oxygen.

• Prior to commencing sedation with N2O, always carefully inspect the apparatus and circuit for any leaks. If the reservoir bag does not inflate, examine for a tear.

• A range of fragrant nasal masks is available and useful in making the child feel more comfortable and involves them in the process by offering some choice. Offer the child the mask to take home prior to the treatment appointment, so that he/she can gain familiarity in wearing it.

Procedures

• Recline the dental chair and place the mask on the child’s nose so that it fits properly. Once in place, check the mask sits comfortably on the child’s face in close proximity to the skin, and secure the mask so that it covers the nostrils completely and does not move unnecessarily during the procedure.

• Determine the minute volume of the child. Variable flow IS machines are essential for use in children.

• Start the procedure with 100% oxygen with active scavenging. Monitor the reservoir bag as the child breathes – it should move at the same rate as the child’s breathing with each inspiration and expiration.

• Constant monitoring is critical and the use of pulse oximetry is advised. Assess the child’s eyes, general responses and level of consciousness throughout the procedure.

• When using the ‘rapid induction technique’, administer the N2O quickly to 50% and then reduce to the appropriate level for that individual.

• When using a slow titration technique, the N2O is titrated in 10% intervals.

Sensations of analgesia

Children are very open to suggestion. Their thoughts and behaviours can be guided by the dentist. Describe (suggest) the sensations that the child will feel:

Determining levels of sedation

• Once local anaesthesia has been administered successfully, the N2O should be lowered to around 30% and maintained at this level. Repeatedly adjusting the levels can be quite disconcerting and so changes should be kept to a minimum.

• Once the procedure is complete, or near completion, the concentration of gas should be lowered, so that the child is maintained on 100% oxygen. This displaces nitrous oxide from the child’s body and lessens the risk post-procedural diffusion hypoxia.

• The level at which a patient will be comfortable under IS will be different for every child. Excessive amounts of N2O may put the child into the excitement stage of anaesthesia (Guedel Stage II) and may induce vomiting, a feeling of fear or excessive movement.

Give clear postoperative instructions to the parent. The child should rest for the remainder of the day and only engage in sedentary activities. Physical activity should be avoided and the child should remain under continuous supervision.

Conscious sedation

The term ‘conscious sedation’ has been used in the past to imply a patient who is awake, responsive and able to communicate. This verbal communication with the child is an indicator of an adequate level of consciousness and maintenance of protective reflexes. In clinical practice, however, sedation (conscious sedation, deep sedation and/or general anaesthesia) is a continuum. Any technique which depresses the CNS may result in a deeper sedation state than intended, and consequently, clinicians who sedate children require a much higher level of skill with a particular technique, the relevant training and experience and the proper qualifications with the relevant regulating authority.

Sedation of children for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures remains an area of rapid change in medicine and one of considerable controversy. Publications (Cote et al. 2000) have identified several features associated with adverse sedation-related events and poor outcomes, namely:

• Occur more frequently in a non-hospital-based facility.

• Inadequate resuscitation was more often associated with a non-hospital-based setting.

• Inadequate and inconsistent physiological monitoring.

• Often associated with drug overdoses and the use of multiple agents, especially when three or more drugs were used.

• Inadequate preoperative assessment.

Considerations for paediatric sedation in the dental setting

• Uniform, multidisciplinary-approved guidelines for monitoring children during sedation are essential.

• The same level of care should apply to hospital-based and non-hospital-based facilities (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 An intravenous (conscious) sedation clinic has a similar set up to a normal operating room environment with monitoring and resuscitation equipment.

• Pulse oximetry should be mandatory whenever a child is sedated, irrespective of the route of drug administration or the dosage.

• Age and size-appropriate equipment and medications for resuscitation should be immediately available in a designated ‘crash cart’, regardless of the location where the child is sedated.

• All healthcare providers who sedate children, regardless of practice venue, should have advanced airway management and resuscitation skills.

• Practitioners must carefully weigh the risks and the benefits of sedating children beyond the safety net of a hospital or hospital-like environment.

• Practitioners must understand that the absence of skilled back-up personnel could pose significant risks in the event of a medical emergency (Cote et al. 2000; Cravero & Blike 2006; Cote & Wilson 2006).

Oral sedation

Oral sedation is the most popular route used by paediatric dentists, due to the ease of administration for most children. There are a number of agents used for this technique including:

Midazolam has increased in popularity in the last decade due to its safety and short-acting nature, allowing a quick recovery and discharge of the patient. Oral dosage varies from 0.3–0.7 mg/kg, however a maximum ceiling dose (e.g. 10 mg) is usually determined for the older age groups. There are a number of studies that report on the use of oral midazolam, as a successful technique for children with the following selection criteria:

• Children of ages 24 months to 6–8 years of age (depending on individual characteristics, e.g. body weight).

• Short or simple procedures (<30 min).

• Parents who are ‘fit’ for the technique, that is, they are able to care adequately for the child after the procedure.

Although the technique is successful in the older age groups, it may be more difficult to deal with children of larger size, once sedated. Children over 6 years may become disinhibited and there is a higher frequency of paradoxical reactions in this age group. In addition, obese children may present added airway complications and issues with pharmacokinetics of the drug. Appropriate fasting for elective procedures is preferable.

The main disadvantage of the oral route is that the drugs given cannot be titrated accurately. As most drugs undergo hepatic metabolism, only a fraction of the original dose is active. This makes titration difficult and unreliable, unlike other techniques such as IS and IV sedation. Equally, an overdose cannot be easily reversed. Oral sedation requires enough cooperation of the child to be able to take the medication orally. A child may also spit out the medication. Never re-dose, as it is impossible to accurately determine how much of the drug was ingested.

In the pre-cooperative age group, a knee-to-knee position offers good access for the delivery of oral medications. This technique is also used to treat young children as it allows good control of the patient, easy restraint by the parent/carer and good vision into the mouth by the clinician.

Rectal sedation

Although used routinely in Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, this form of sedation is less common in Australasia, Asia, the UK and the USA, because of cultural sensitivities. It is, however, an excellent route for drug administration and provides a more reliable and controllable absorption than the oral route.

Intra-nasal sedation

This implies delivery of medication directly to the nasal mucosa by spray or drops. However, due to reported complications and a poorly understood mechanism of action (there is controversy as to whether the drug is absorbed directly from the blood stream or taken up directly to the CNS), this route is considered as an IV route and consequently requires a higher level of training and monitoring.

Intravenous sedation

This technique requires a highly trained team, including an experienced and appropriately qualified sedationist or specialist anaesthetist, medical nurses trained in this technique, and also a dentist trained in and familiar with the effects of sedation in clinical dentistry. Appropriate monitoring, adequate facilities and recovery options are mandatory for the safe delivery of intravenous drugs. The relevant regulating body in each country dictates these guidelines.

Intravenous sedation has the advantage of the procedure being controllable and may be readily reversible, but as most children are frightened of needles, it might seem an inappropriate form of drug administration in extremely anxious children. Although different drug combinations may be used under IV, in Australia, a combination of midazolam and an opioid analgesic (fentanyl) is often used. These drugs are readily reversible by flumazenil and naloxone, respectively.

Patients with the following criteria ARE considered suitable for IV sedation

• Child patients 8 years of age or older.

• Must have a degree of cooperation to allow injection and have adequate venous access (dorsum of hand or antecubital fossa).

• Obese children (where resuscitation procedures may be difficult and the airway more unpredictable).

• Children with significant respiratory disease such as cystic fibrosis, poorly controlled asthma or sleep apnoea.

• Dysphagia, liquid diet or thickened fluids, history of aspiration pneumonia.

• Poorly controlled epilepsy or reflux.

• Parents who may not provide adequate care to the child postoperatively.

Procedures usually NOT suitable for IV sedation

• 3–4 quadrants of dentistry (unless minor restorative).

• Extractions of permanent molars in each quadrant (invasive procedure and bleeding from all four quadrants make airway management more difficult).

• Obese children (where resuscitation procedures may be difficult and the airway more unpredictable).

• Parents who may not provide adequate care to the child postoperatively.

Intravenous sedation is usually performed in a hospital environment or in dental surgeries that have been duly accredited for the use of these more advanced sedation techniques.

Sedation protocols are strictly defined in many countries by regulations and guidelines. A comprehensive document (PS9) applies to several medical and dental colleges in Australia and New Zealand (PS9, 2010).

General anaesthesia

While it is the most expensive form of treatment, the use of general anaesthesia (GA) for dental treatment has increased globally. This is due to the increase in availability, safety, and an understanding that it is the most appropriate way in which to manage young children requiring extensive dental treatment. This is also in-line with the management of most other invasive medical procedures that are performed under anaesthesia around the world.

It is significant that mortality rates from anaesthesia have decreased around the world. In Australia, in 2005, deaths due to anaesthesia in all age groups was estimated to be 1 : 53 000. The mortality rate for children, although unable to be accurately quantified, was much lower than this, and is estimated to be 1 : 150 000. There are no available figures documenting morbidity in children arising from general anaesthesia.

Although most children will cope with dentistry in a normal setting, many may benefit from delivery of extensive dentistry in one session under GA. The decision to arrange general anaesthesia should not be taken lightly, as there are risks and although less frequent, more serious complications may arise from the anaesthetic. The clinician must make a decision balancing the need against the risk. Economic (public health access and private insurance) and cultural factors and access to anaesthetic facilities may also influence the use of GA. When deciding to place the child under general anaesthesia, the clinician must look at the whole picture.

Is the treatment absolutely necessary?

• Could the patient be managed more conservatively?

• Has the child undergone a period of familiarization?

• Has there been a history of emotional trauma associated with the dental environment?

Certain clinical situations automatically indicate the need for general anaesthesia:

Treatment planning under GA requires experience and careful consideration to avoid treatment failures or repeat GAs. Consequently, GA treatment in paediatric dentistry ideally should only be carried out by dentists with the appropriate postgraduate qualifications.

Consent for treatment

In many countries consent is dependent on the age of the child. For descriptive purposes only the age of consent has been described as it applies in Australia.

Consent for children younger than 14 years of age

In children under 14 years of age, a specific ‘Consent form’ is required. The parent or guardian must sign the form and a dentist must witness the signature.

Consent for children 14–16 years of age

Children aged 14–16 years must give their own consent for the treatment to be performed. Although a ‘responsible informed child’ can give this consent, the parent or guardian should also give consent and sign the form. The dentist should explain the procedure and witness the signatures.

Although there is no authoritative statement in statute law regarding consent for children younger than 16 years, common law (Australasia and the UK) dictates that:

… as a matter of law the parents’ right to determine whether or not their minor child below the age of 16 will have medical treatment terminates if and when their child achieves a sufficient understanding to enable him to understand fully what is proposed.

(Gillick v West Norfolk Area Health Authority [1986] AC 112, UK)

Consent over 16 years

A patient 16 years and over must consent for their own treatment.

Emergency treatment

In emergency situations, dental treatment may be performed without the consent of the child or parent or guardian if, in the opinion of the practitioner, the treatment is necessary and a matter of urgency in order to save the child’s life, or to prevent serious damage to the child’s health (Section 20B of the Children [Care and Protection] Act [1987] NSW, Australia). Fortunately, there are few situations where this will occur in the dental environment, although situations do arise for those working in hospital settings. The overriding point is to ‘do no harm’.

It is important that when possible, ‘informed consent’ be obtained. The clinician must carefully explain all the procedures planned using lay language as appropriate. All potential risks need to be mentioned, discussed and documented. When completing the sections on standard forms on the nature of the operation, be specific, do not use abbreviations and include all the procedures planned. Where appropriate, use simple terminology to describe the operation.

Pre-anaesthetic assessment for general anaesthesia

A medical history and examination by the anaesthetist is required prior to the procedure. If a patient has complex medical problems, a preoperative anaesthetic assessment may be required as a separate consultation prior to the day of surgery.

The anaesthetist will particularly want to be aware of:

• Behavioural issues, e.g. autism, developmental delay, extreme anxiety and needle phobia.

• Syndromes, e.g. Down syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome.

• Cardiac disease, heart murmurs, previous surgery for congenital defects.

• Respiratory disease, e.g. asthma.

• Airway problems, e.g. history of croup, cleft palate, micrognathia, previous tracheostomy, known history of intubation difficulties, sleep apnoea.

• Neurological disease, e.g. epilepsy, previous brain injuries, cerebral palsy.

• Endocrine and metabolic disorders, e.g. diabetes, genetic metabolic disorders.

• Gastrointestinal problems, e.g. reflux, difficulty swallowing or feeding.

• Haematological, e.g. haemophilia, thrombocytopenia, haemoglobinopathies.

Allergies must be noted, including latex allergy.

Medications must be documented. Most medications should be continued until the time of anaesthesia unless there is a clear reason to withhold (e.g. with anticoagulants or insulin). Consultation with the original prescriber should be made before warfarin or aspirin is ceased to make an assessment of the risk or benefit of ceasing these drugs. Management of diabetic patients will require consultation with the patient’s endocrinologist.

Upper respiratory tract infection

If a child presents with an upper respiratory tract infection on the day of surgery, it may be appropriate to delay elective anaesthesia for 2–3 weeks. This decision can be balanced against economic and social issues and patient factors such as the child’s age, urgency of treatment, severity of the infection and any other medical problems the child may have. Ultimately, the decision to cancel or proceed is up to the anaesthetist.

Fasting

Normally, the stomach is empty of clear fluids 2 hours after ingestion. Accepted practice for fasting for anaesthesia is:

Keeping fasting instructions close to these guidelines will cause the least distress for the patient. Unfortunately, difficulties with organizational factors often result in longer fasting times.

There is no evidence that oral medications taken during the time of fasting increases the risk of aspiration during anaesthesia.

Operating theatre environment

There is often a misconception that everything that happens in an operating room is sterile, and unless staff are familiar with dental procedures, the experience for many children and parents can be overly bureaucratic. While clinicians must follow the protocols of the individual institution under which they operate, it is essential that auxiliary staff appreciate the anxiety that our patients feel and why they are having their treatment performed under general anaesthesia. To reduce the child’s fear and anxiety, strategies should be used to help them to cope with the operating theatre environment. For example:

• Minimizing the waiting time prior to the procedure.

• Leaving them in their own clothes. It is not necessary to change into theatre attire for routine restorative procedures.

• Allowing a parent to stay with the child during induction of anaesthesia.

• Using topical local anaesthetic cream such as EMLA® if an intravenous induction is planned.

• Allowing a parent into the recovery area to be with the child as soon as they are awake and stable.

Premedication

Some children may require oral premedication prior to anaesthesia. Suggested regimens are paracetamol 15 mg/kg and midazolam 0.2–0.5 mg/kg.

Induction

Anxiety is minimized by allowing a parent to be with the child during induction. Anaesthesia induction may be intravenous or gaseous and will be the choice of the anaesthetist. Sevoflurane with nitrous oxide and oxygen can be given for a gaseous induction. It is not too unpleasant, and with skill, can be used with little distress to the patient. The use of topical local anaesthetic cream prior to insertion of a cannula into a vein alleviates some of the pain of obtaining intravenous access. Some extremely uncooperative children may require induction with intramuscular ketamine 2–3 mg/kg. These are usually older autistic or developmentally delayed children.

Sharing the airway (Figure 3.5)

• The anaesthetist and dentist must share the airway, so teamwork, and mutual understanding of each other’s needs, is necessary.

• Nasotracheal intubation with a nasal RAE (Ring-Adair-Elwyn) tube provides good access for the dentist and a secure airway for the anaesthetist. A throat pack is usually used and it is essential to ensure the removal of a throat pack at the end of the case.

• The throat pack should not be so bulky that the tongue is forced anteriorly limiting the access to the mouth for the dentist. In young children, reduce the size of an adult-sized pack to one-third (ribbon gauze of about 30 cm moistened with saline).

• An oral laryngeal mask airway or endotracheal tube provides a satisfactory airway for the anaesthetist, but may or may not give the dentist the access they require, as it encroaches on the work area. However, this is a useful technique for less extensive dental work, such as extractions of primary teeth after trauma or when a nasal tube is contraindicated. If a laryngeal mask airway is used, a flexible one is most appropriate, but it is a less secure airway than an endotracheal tube.

• A face-mask-only technique may be used for simple extractions. The mask is removed for a short time while the extraction is performed. However, the airway must be protected. This can be done by placing a gauze swab behind the teeth being extracted.

• During anaesthesia, it is important to protect the eyes from injury by taping them shut and possibly covering them with padding.

• Before waking the patient, all foreign material such as rolls, gauze and throat packs must be removed and accounted for.

Figure 3.5 Management under general anaesthesia. (A,B) Treatment under general anaesthesia must be conducted in a comfortable atmosphere. There must be cooperation between the anaesthetist and the operating dentist, both of whom need access to the oral cavity and the airway. Nasal intubation is invaluable. Note the anaesthetic machine in close proximity but out of the way of the operating surgeon and the dental assistant also has all the required equipment close at hand. Individual institutions’ protocols vary however, and it is not usually necessary to scrub for restorative procedures, as these are considered to be ‘non-sterile’. (C) Surgical procedures should be performed under sterile conditions.

Analgesia

Analgesia, as appropriate, should be given while the patient is anaesthetized. The use of intravenous opioids may be required. As mentioned earlier, local anaesthetics may be used, but often the feeling of numbness around the mouth causes even more distress than the discomfort of the procedure. NSAIDs such as ibuprofen 10 mg/kg 6-hourly, may be prescribed. Paracetamol 15 mg/kg 4-hourly may also be used. Occasionally, oral morphine or codeine phosphate may be required.

Emergence

Ideally, parents should be able to come into the recovery area once the child is awake and in a stable condition. Distress on waking is not uncommon, and can be due to emergence delirium. The child is quite likely to be upset by the unfamiliar environment, an unpleasant taste in the mouth or because their mouth feels different because of missing teeth or new crowns.

Categories of anaesthetic risk

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

Suitability for day-stay anaesthesia

Most children who are ASA 1 or 2 will be suitable for day-stay anaesthesia (Figure 3.6). However, children with more severe systemic disease may need peroperative and overnight hospital care to ensure that they are maintaining their airway, tolerating oral food and fluids, that any pain is satisfactorily managed and that there is no ongoing bleeding.

Ward instructions

Postoperative instructions and consultation notes in the medical file must be clear and legible. It is important for nursing staff to understand what procedures have been performed and by whom. They should also know whom to contact if complications arise.

Further reading

Pain control for children

1. Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Analgesic Version 5. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2007.

2. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. The paediatric patient In: NHMRC Acute pain management: scientific evidence. third ed Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine 2010; In: www.anzca.edu.au/publications/acutepain.htm; 2010.

3. Herschell AD, Calzada E, Eyberg SM, et al. Clinical issues with parent–child interaction therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;9:16–27.

4. Lamacraft G, Cooper MG, Cavalletto BP. Subcutaneous cannulae for morphine boluses in children: assessment of a technique. Journal of Pain Symptoms and Management. 1997;13:43–49.

5. NSW Health. Paracetamol use, 2006 PD2006_004 [policy directive]. In: www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2006/PD2006_004.html; 2006.

6. Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Paediatrics and Child Health Division Guideline statement: Management of procedure related pain in children and adolescents. In: www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2006/PD2006_004.html; 2005.

7. Weisman SJ, Berstein B, Schechter NL. Consequences of inadequate analgesia during painful procedures in children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152:147–149.

8. Williams DG, Hatch DJ, Howard RF. Codeine phosphate in paediatric medicine. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2001;86:413–421.

Sedation

1. Cote CJ, Wilson S. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures An update. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2587–2602.

2. Cote CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics A critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4):805–814.

3. Cote CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: Analysis of medications used for Sedation. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):633–644.

4. Cravero JP, Blike GT. Review of pediatric sedation. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2006;99(5):1355–1364.

5. European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD). Guidelines on sedation in paediatric dentistry. In: http://www.eapd.gr/dat/5CF03741/file.pdf;.

6. Goodson JM, Moore PA. Life-threatening reactions after pedodontic sedation: an assessment of narcotic, local anesthetic, and antiemetic drug interaction. Journal of the American Dental Association. 1983;107(2):239–245.

7. 2010. Guidelines on sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical, dental or surgical procedures. In: http://www.anzca.edu.au/resources/professional-documents/documents/professional-standards/pdf-files/PS9-2010.pdf; 2010.

8. Hosey MT. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry Managing anxious children: the use of conscious sedation in paediatric dentistry. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2002;12(5):359–372.

9. Houpt M. Project USAP, 2000 – use of sedative agents by pediatric dentists: a 15-year follow up survey. Pediatric Dentistry. 2002;24(4):289–294.

10. Kupietzky A, Houpt MI. Midazolam: a review of its use for conscious sedation of children. Pediatric Dentistry. 1993;15(4):237–241.

11. Lee JY, Vann WF, Roberts MW. A cost analysis of treating pediatric dental patients using general anesthesia versus conscious sedation. Pediatric Dentistry. 2000;22(1):27–32.

12. Primosch RE, Buzzi IM, Jerrell G. Effect of nitrous oxide-oxygen inhalation with scavenging on behavioral and physiological parameters during routine pediatric dental treatment. Pediatric Dentistry. 1999;21(7):417–420.

13. Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario, Canada. Guidelines: use of sedation and general anaesthesia in dental practice. In: http://www.rcdso.org/sedationAnaesthesia_pdf/Guidelines_sedation_06_09.pdf; 2009.

14. Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry. Standardised evaluation of conscious sedation practice for dentistry in the UK. In: http://www.saad.org.uk/files/documents/Standardised%20Evaluation%20of%20Conscious%20Sedation%20Practice%20for%20Dentistry%20in%20the%20UK.pdf; 2009.

15. Wilson S. Pharmacological management of the pediatric dental patient. Pediatric Dentistry. 2004;26(2):131–136.

16. Yagiela JA, Cote CJ, Notterman DA, et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1494.