Lower Gastrointestinal System

Radiographic Anatomy

Digestive System

The first five parts of the alimentary canal (through the stomach and first part of the small intestine, the duodenum) are described in Chapter 12.

This chapter continues with the alimentary canal of the digestive system beyond the stomach, beginning with the small intestine (small bowel). If the entire small intestine were removed from the body at autopsy, separated from its mesenteric attachment, uncoiled, and stretched out, it would average 7 m (23 feet) in length. During life, with good muscle tone, the actual length of the small intestine is shorter, measuring 4.5 to 5.5 m (15 to 18 feet). However, tremendous individual variation exists. In one series of 100 autopsies, the small bowel ranged in length from 15 to 31 feet. The diameter varies from 3.8 cm (1.5 inches) at the proximal aspect to about 2.5 cm (1 inch) at the distal end.

The large intestine (large bowel) begins in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) with its connection to the small intestine. The large intestine extends around the periphery of the abdominal cavity to end at the anus. The large intestine is about 1.5 m (5 feet) long and about 6 cm (2.5 inches) in diameter.

Common Radiographic Procedures

Two common radiographic procedures involving the lower gastrointestinal system are presented in this chapter. Both procedures involve administration of a contrast medium.

Small Bowel Series—Study of Small Intestine

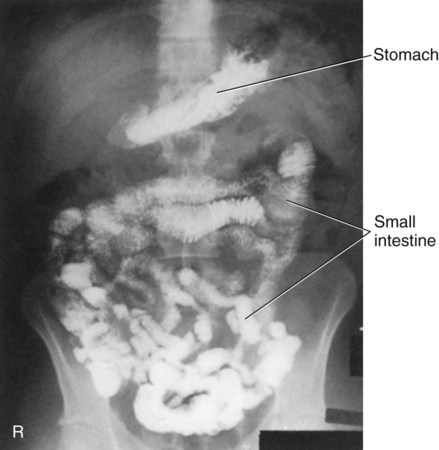

Radiographic examination specifically of the small intestine is called a small bowel series (SBS). This examination often is combined with an upper GI series and under these conditions may be termed a small bowel follow-through. A radiograph of the barium-filled small bowel is shown in Fig. 13-2.

Barium Enema (Lower GI Series, Colon)—Study of Large Intestine

The radiographic procedure designed to study the large intestine is most commonly termed a barium enema. Alternative designations include BE, BaE, and lower GI series. Fig. 13-3 shows a large bowel or colon filled with a combination of air and barium, referred to as a double-contrast barium enema. Note: This patient has situs inversus, in which abdominal and thoracic organs are reversed from their normal orientation within the body.

Small Intestine

Beginning at the pyloric valve of the stomach, the three parts of the small intestine, in order, are the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The relative location of the three parts of the small intestine in relation to the four abdominal quadrants (right upper quadrant [RUQ], RLQ, left upper quadrant [LUQ], left lower quadrant [LLQ]) is demonstrated.

Duodenum (RUQ and LUQ)

The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine, as described in detail in Chapter 12. It is the shortest, widest, and most fixed portion of the small bowel. It is located primarily in the RUQ. It also extends into the LUQ, where it joins the jejunum at a point called the duodenojejunal flexure. It represents the shortest aspect of the small intestine and averages 20 to 25 cm in length.*

Jejunum (LUQ and LLQ)

The jejunum is located primarily to the left of midline in the LUQ and LLQ, making up about two-fifths of the remaining aspect of the small intestine. Its inner diameter is approximately 2.5 cm. The jejunum contains numerous mucosal folds (plicae circulares), which increase the surface area to aid with absorption of nutrients. These numerous mucosal folds produce the “feathery appearance of the jejunum.”*

The jejunum begins at the site of the duodenojejunal flexure, slightly to the left of midline in the LUQ (under the transverse colon as seen in Fig. 13-4). This relatively fixed site of the small bowel may become a radiographic reference point during a small bowel study.

Ileum (RLQ and LLQ)

The ileum is located primarily in the RUQ, RLQ, and LLQ. The ileum makes up the distal three-fifths of the remaining aspect of the small intestine and is the longest portion of the small intestine. The terminal ileum joins the large intestine at the ileocecal valve (sphincter or fold) in the RLQ, as shown in Fig. 13-4. Although it is longer than the jejunum, the ileum possesses a thinner wall and has fewer mucosal folds (plicae circulares). At the point of the ileocecal valve (sphincter), the inner lumen of the ileum is nearly smooth.*

Sectional Differences

Various sections of the small intestine can be identified radiographically by their location and by their appearance. The C-shaped duodenum is fairly fixed in position immediately distal to the stomach and is recognized easily on radiographs. The internal lining of the second and third (descending and horizontal) portions of the duodenum is gathered into tight circular folds formed by the mucosa of the small intestine, which contains numerous small, finger-like projections termed villi, resulting in a “feathery” appearance when filled with barium.

The mucosal folds of the distal duodenum are found in the jejunum as well. Although there is no abrupt end to the circular feathery folds, the ileum tends not to have this appearance. This difference in appearance between the jejunum and the ileum can be seen in the barium-filled small bowel radiograph in Fig. 13-5 and the coronal abdominal CT (computed tomography) scan in Fig. 13-6.

A CT axial or cross-sectional image through the level of the second portion of the duodenum is seen in Fig. 13-7. This image shows the relative positions of the stomach and duodenum in relation to the head of the pancreas. A portion of jejunal loops is also shown on the patient's left, along with a small aspect of the left colic flexure seen lateral to the stomach.

Large Intestine

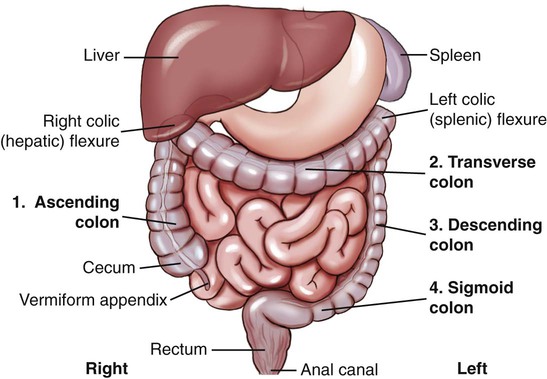

The large intestine begins in the RLQ, just lateral to the ileocecal valve. The large intestine consists of four major parts: cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal (see Fig. 13-8).

The final segment of the large intestine is the rectum. The distal rectum contains the anal canal, which ends at the anus.

Colon Versus Large Intestine

Large intestine and colon are not synonyms, although many technologists use these terms interchangeably. The colon consists of four sections and two flexures and does not include the cecum and rectum. The four sections of the colon are (1) the ascending colon, (2) the transverse colon, (3) the descending colon, and (4) the sigmoid colon. The right (hepatic) and left (splenic) colic flexures also are included as part of the colon.

The transverse colon has a wide range of motion and normally loops down farther than is shown on this drawing.

Cecum

At the proximal end of the large intestine is the cecum, a large blind pouch located inferior to the level of the ileocecal valve. The vermiform appendix (commonly referred to as just the appendix) is attached to the cecum. The internal appearance of the cecum and terminal ileum is shown in Fig. 13-9. The most distal part of the small intestine, the ileum, joins the cecum at the ileocecal valve. The ileocecal valve consists of two lips that extend into the large bowel.

The ileocecal valve acts as a sphincter to prevent the contents of the ileum from passing too quickly into the cecum. A second function of the ileocecal valve is to prevent reflux, or a backward flow of large intestine contents, into the ileum. The ileocecal valve does only a fair job of preventing reflux because some barium can almost always be refluxed into the terminal ileum when a barium enema is performed. The cecum, the widest portion of the large intestine, is fairly free to move about in the RLQ.

The vermiform appendix (appendix) is a long (2 to 20 cm), narrow, worm-shaped tube that extends from the cecum. The term vermiform means “wormlike.” The appendix usually is attached to the posteromedial aspect of the cecum and commonly extends toward the pelvis. However, it may pass posterior to the cecum. Because the appendix has a blind ending, infectious agents may enter the appendix, which cannot empty itself. Also, obstruction of the opening into the vermiform appendix caused by a small fecal mass may lead to narrowing of the blood vessels that feed it. The result is an inflamed appendix, or appendicitis. Appendicitis may require surgical removal, which is termed an appendectomy, before the diseased structure ruptures, causing peritonitis. Acute appendicitis accounts for about 50% of all emergency abdominal surgeries and is 1.5 times more common in men than in women.

Occasionally, fecal matter or barium sulfate from a gastrointestinal tract study may fill the appendix and remain there indefinitely.

Large Intestine—barium-Filled

The radiograph shown in Fig. 13-10 demonstrates the barium-filled vermiform appendix; the four parts of the colon—ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid; and the two flexures—the right colic (hepatic) flexure and the left colic (splenic) flexure. The remaining three parts of the large intestine—cecum, rectum, and anal canal—are also shown. As is shown by this radiograph, these various parts are not as neatly arranged around the periphery of the abdomen as they are on drawings. There is a wide range of structural locations and relative sizes for these various portions of the large intestine, depending on the individual body habitus and contents of the intestine.

Rectum and Anal Canal

The rectum extends from the sigmoid colon to the anus. The rectum begins at the level of S3 (third sacral segment) and is about 12 cm ( inches) long. The final 2.5 to 4 cm (1 to

inches) long. The final 2.5 to 4 cm (1 to  inches) of large intestine is constricted to form the anal canal. The anal canal terminates as an opening to the exterior, the anus. The rectum closely follows the sacrococcygeal curve, as demonstrated in the lateral view in Fig. 13-11.

inches) of large intestine is constricted to form the anal canal. The anal canal terminates as an opening to the exterior, the anus. The rectum closely follows the sacrococcygeal curve, as demonstrated in the lateral view in Fig. 13-11.

The rectal ampulla is a dilated portion of the rectum located anterior to the coccyx. The initial direction of the rectum along the sacrum is inferior and posterior. However, in the region of the rectal ampulla, the direction changes to inferior and anterior. A second abrupt change in direction occurs in the region of the anal canal, which is directed again inferiorly and posteriorly. Therefore, the rectum presents two anteroposterior curves. This fact must be remembered when a rectal tube or enema tip is inserted into the lower gastrointestinal tract by the technologist for a barium enema procedure. Serious injury can occur if the enema tip is forced at the wrong angle into the anus and anal canal.

Large Versus Small Intestine

Three characteristics readily differentiate the large intestine from the small intestine.

1. The internal diameter of the large intestine is usually greater than the diameter of the small bowel.

2. The muscular portion of the intestinal wall contains three external bands of longitudinal muscle fibers of the large bowel that form three bands of muscle called taeniae coli, which tend to pull the large intestine into pouches. Each of these pouches, or sacculations, is termed a haustrum. Most of the large intestine except for the rectum possesses haustra. Therefore, a second primary identifying characteristic of the large bowel is the presence of multiple haustra. This characteristic can be seen in the enlarged drawing of the proximal large intestine in Fig. 13-12.

3. The third differentiation is the relative positions of the two structures. The large intestine extends around the periphery of the abdominal cavity, whereas the small intestine is more centrally located.

Relative Locations of Air and Barium in Large Intestine

The distribution of air and barium is influenced most often by the location of each portion of the large intestine in relation to the peritoneum. Aspects of the large intestine are more anterior or more posterior in relation to the peritoneum. The cecum, transverse colon, and sigmoid colon are more anterior than other aspects of the large intestine.

The simplified drawings in Fig. 13-13 represent the large intestine in supine and prone positions. If the large intestine contained both air and barium sulfate, the air would tend to rise and the barium would tend to sink because of gravity. Displacement and the ultimate location of air are shown as black, and displacement and the ultimate location of the barium are shown as white.

When a person is supine, air rises to fill the structures that are most anterior—that is, the transverse colon and loops of the sigmoid colon. The barium sinks to fill primarily the ascending and descending colon and aspects of the sigmoid colon.

When a patient is prone, barium and air reverse positions. The drawing on the right illustrates the prone position—air has risen to fill the rectum, ascending colon, and descending colon.

Recognizing these spatial relationships is important during fluoroscopy and during radiography when barium enema examinations are performed.

Anatomy Review

Small Bowel Radiographs

Three parts of the small bowel can be seen in these 30-minute and 2-hour small bowel radiographs, taken 30 minutes and 2 hours after ingestion of barium (Figs. 13-14 to 13-16). Note the characteristic “feathery” sections of duodenum (A) and jejunum (C). The smoother appearance of the ileum is also evident (D).

The terminal portion of the ileum (D), the ileocecal valve (E), and the cecum of the large intestine are best shown on a spot film of this area (Fig. 13-14). A spot image of the ileocecal valve area such as this, obtained with a compression cone, frequently is taken at the end of a small bowel series to visualize this region best. These figures illustrate the following labeled parts of the small intestine:

Barium Enema

Anteroposterior (AP), lateral rectum, and left anterior oblique (LAO) radiographs of a barium enema examination (Figs. 13-17 to 13-19) illustrate the key anatomy of the large intestine, labeled as follows:

Digestive Functions

Digestive Functions of the Intestines

The following four primary digestive functions are accomplished largely by the small and large intestines:

1. Digestion (chemical and mechanical)

3. Reabsorption of water, inorganic salts, vitamin K, and amino acids

Most digestion and absorption take place within the small intestine. Also, most salts and approximately 95% of water are reabsorbed in the small intestine. Minimal reabsorption of water and inorganic salts occurs in the large intestine, as does the elimination of unused or unnecessary materials.

The primary function of the large intestine is the elimination of feces (defecation). Feces consist normally of 65% water and 35% solid matter, such as food residues, digestive secretions, and bacteria. Other specific functions of the large intestine include absorption of water, inorganic salt, vitamin K, and certain amino acids. These vitamins and amino acids are produced by a large collection of naturally occurring microorganisms (bacteria) found in the large intestine.

The last stage of digestion occurs in the large intestine through bacterial action, which converts the remaining proteins into amino acids. Some vitamins, such as B and K, are synthesized by bacteria and absorbed by the large intestine. A by-product of this bacterial action is the release of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane gas. These gases, called flatus (fla′-tus), help to break down remaining proteins to amino acids.

Movements of Digestive Tract

Of the various digestive functions of the intestine, digestive movements, sometimes referred to as mechanical digestion, are best demonstrated and evident on radiographic studies.

Digestive movements throughout the length of the small bowel consist of (1) peristalsis (per″-i-stal′-sis) and (2) rhythmic segmentation. Peristalsis describes wavelike contractions that propel food from the stomach through the small and large intestines and eventually expel it from the body. Barium sulfate enters the stomach and reaches the ileocecal valve 2 to 3 hours after ingestion.

Rhythmic segmentation describes localized contractions in areas or regions that contain food. For example, food within a specific aspect of the small intestine is contracted to produce segments of a particular column of food. Through rhythmic segmentation, digestion and reabsorption of select nutrients are more effective.

In the large intestine, digestive movements continue as (1) peristalsis, (2) haustral (haws′-tral) churning, (3) mass peristalsis, and (4) defecation (def″-e-ka′-shun). Haustral churning produces movement of material within the large intestine. During this process, a particular group of haustra (bands of muscle) remains relaxed and distended while the bands are filling up with material. When distention reaches a certain level, the intestinal walls contract or “churn” to squeeze the contents into the next group of haustra. Mass peristalsis tends to move the entire large bowel contents into the sigmoid colon and rectum, usually once every 24 hours. Defecation is a so-called bowel movement, or emptying of the rectum.

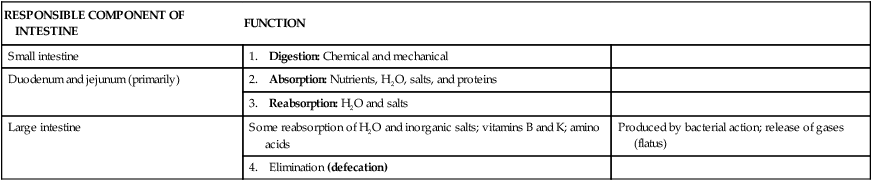

SUMMARY OF LOWER DIGESTIVE SYSTEM FUNCTIONS

| RESPONSIBLE COMPONENT OF INTESTINE | FUNCTION | |

| Small intestine | 1. Digestion: Chemical and mechanical | |

| Duodenum and jejunum (primarily) | 2. Absorption: Nutrients, H2O, salts, and proteins | |

| 3. Reabsorption: H2O and salts | ||

| Large intestine | Some reabsorption of H2O and inorganic salts; vitamins B and K; amino acids | Produced by bacterial action; release of gases (flatus) |

| 4. Elimination (defecation) |

Radiographic Procedures

Small Bowel Series

The plain abdominal radiograph (KUB) shown in Fig. 13-20 is from a healthy, ambulatory adult. The many meters of small intestine are generally not visible in the central portion of the abdomen. In the average ambulatory adult, a large collection of gas in the small intestine is considered abnormal. With no gas present, the small bowel simply blends in with other soft tissue structures. Therefore, radiographic examination of the alimentary canal requires the introduction of contrast media for visualization.

Definition

A radiographic study specifically of the small intestine is termed a small bowel series. Upper GI and small bowel series are frequently combined. Under these circumstances, the small bowel portion of the examination may be called a small bowel follow-through. Radiopaque contrast media are required for this study.

Purpose

The purposes of the small bowel series are to study the form and function of the three components of the small bowel and to detect any abnormal conditions.

Because this study also examines function of the small bowel, the procedure must be timed. The time when the patient has ingested a substantial amount (at least 8 oz) of contrast medium should be noted.

Contraindications

Two strict contraindications to contrast media studies of the intestinal tract are known.

First, presurgical patients and patients suspected to have a perforated hollow viscus (intestine or organ) should not receive barium sulfate. Water-soluble, iodinated contrast media should be used instead. With young or dehydrated patients, care must be taken when a water-soluble contrast medium is used. Because of the hypertonic nature of these patients, water tends to be drawn into the bowel, leading to increased dehydration.

Second, barium sulfate by mouth is contraindicated in patients with a possible large bowel obstruction. An obstructed large bowel should be ruled out first with an acute abdominal series and a barium enema.

Clinical Indications

Common clinical indications for a small bowel series include the following.

Enteritis (en″-ter-i′-tis) describes inflammation of the intestine, primarily of the small intestine. Enteritis may be caused by bacterial or protozoan organisms and other environmental factors. When the stomach is also involved, the condition is known as gastroenteritis. Chronic irritation may cause the lumen of the intestine to become thickened, irregular, and narrowed.

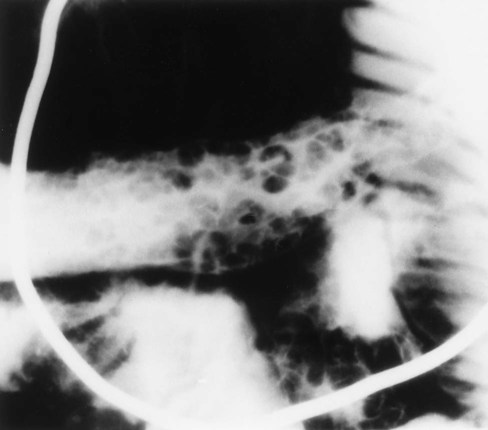

Regional enteritis (segmental enteritis or Crohn's disease) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease of unknown origin, involving any part of the gastrointestinal tract but commonly involving the terminal ileum. This condition leads to scarring and thickening of the bowel wall. This scarring produces the “cobblestone” appearance visible during a small bowel series, or enteroclysis. Radiographically, these lesions resemble gastric erosions or ulcers seen in barium studies as minor variations in barium coating (Fig. 13-21). In advanced cases, segments of the intestine become narrowed as the result of chronic spasm, producing the “string sign” evident during a small bowel series. Regional enteritis frequently leads to intestinal obstruction, fistula, and abscess formation. This disorder also has a high rate of recurrence after treatment.

Giardiasis (je″-ahr-di′-a-sis) is a common infection of the lumen of the small intestine that is caused by the flagellate protozoan (Giardia lamblia). It is often spread by contaminated food and water. It can also be spread via person-to-person contact. Symptoms of giardiasis include nonspecific gastrointestinal discomfort, mild to profuse diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, and weight loss. The presence of this organism usually affects the duodenum and jejunum with spasms, irritability, and increased secretions. A small bowel series typically demonstrates giardiasis as dilation of the intestine, with thickening of the circular folds. Laboratory analysis of a stool specimen can confirm the presence of the Giardia organism.

Ileus (il′-e-us) is an obstruction of the small intestine, as shown in Fig. 13-23, wherein the proximal jejunum is markedly expanded with air. Two types of ileus have been identified: (1) adynamic, or paralytic, and (2) mechanical.

Adynamic, or paralytic, ileus is due to the cessation of peristalsis. Without these involuntary, wavelike contractions, the bowel is flaccid and is unable to propel its contents forward. Causes for adynamic ileus include infection, such as peritonitis or appendicitis; the use of certain drugs; and postsurgical complications. Adynamic ileus usually involves the entire gastrointestinal tract. With adynamic ileus, usually no fluid levels are demonstrated on the erect abdomen projection. However, the intestine is distended with a thin bowel wall.

A mechanical obstruction is a physical blockage of the bowel that may be caused by tumors, adhesions, or hernia. The loops of intestine proximal to the site of obstruction are markedly dilated with gas. This dilation produces the radiographic sign commonly called the “circular staircase” or “herringbone” pattern, which is evident on an erect or decubitus abdomen projection. Air-fluid levels usually are present, as can be seen on these projections.

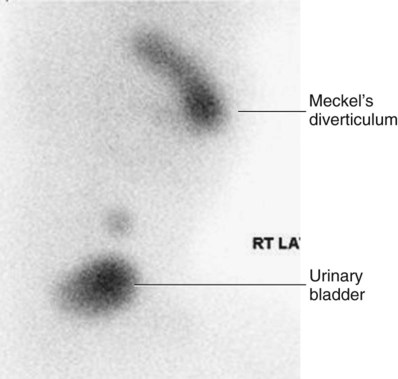

Meckel's diverticulum* is a common birth defect caused by the persistence of the yolk sac (umbilical vesicle) resulting in a saclike outpouching of the intestinal wall. This outpouching is seen in the ileum of the small bowel. It may measure 10 to 12 cm in diameter and is usually 50 to 100 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. Meckel's diverticulum is found incidentally in approximately 3% of adults. The condition does not typically cause symptoms unless inflammation (diverticulitis) or bowel obstruction develops. Pain may mimic acute appendicitis. Surgical removal is often recommended to prevent possible diverticulitis, obstruction, or blood loss. Meckel's diverticulum is rarely seen on barium studies of the small bowel because of rapid emptying during a barium study. It is best diagnosed with a radionuclide (nuclear medicine) scan (Fig. 13-24).

Neoplasm (ne′-o-plazm) is a term that means “new growth.” This growth may be benign or malignant (cancerous). Common benign tumors of the small intestine include adenomas and leiomyomas. Most benign tumors are found in the jejunum and ileum.

Carcinoid tumors, the most common tumors of the small bowel, have a benign appearance, although they have the potential to become malignant. These small lesions tend to grow submucosally and frequently are missed radiographically.

Lymphoma and adenocarcinoma are malignant tumors of the small intestine. Lymphomas are demonstrated during a small bowel series as the “stacked coin” sign. This sign is caused by thickening, coarsening, and possible hemorrhage of the mucosal wall. Other segments of the intestine may become narrowed and ulcerative. Adenocarcinomas produce short and sharp “napkin-ring” defects within the lumen, which may lead to complete obstruction. These radiographic signs of neoplasm are demonstrated during a barium enema procedure. The most frequent sites for adenocarcinoma are the duodenum and the proximal jejunum.

The small bowel series, or enteroclysis, may demonstrate stricture or blockage caused by the neoplasm. CT of the abdomen may further ascertain the location and size of the tumor.

Sprue (spru) and malabsorption syndromes* are conditions in which the gastrointestinal tract is unable to process and absorb certain nutrients. Sprue consists of a group of intestinal malabsorption diseases that involve an inability to absorb certain proteins and dietary fat. The malabsorption may be due to an intraluminal (digestive) defect, a mucosal abnormality, or a lymphatic obstruction. Malabsorption syndrome is often experienced by patients with lactose and sucrose sensitivities. Deficiency syndromes may result from excessive loss of vitamins, electrolytes, iron, or calcium. During a small bowel series, the mucosa may appear thickened as a result of constant irritation.

Celiac disease is a form of sprue or malabsorption disease that affects the proximal small bowel, especially the proximal duodenum. It commonly involves the insoluble protein (gluten) found in cereal grains.

Whipple's disease* is a rare disorder of the proximal small bowel whose cause is unknown. Symptoms include dilation of the intestine, edema, malabsorption, deposits of fat in the bowel wall, and mesenteric nodules. Whipple's disease is best diagnosed with a small bowel series, which shows distorted loops of small intestine.

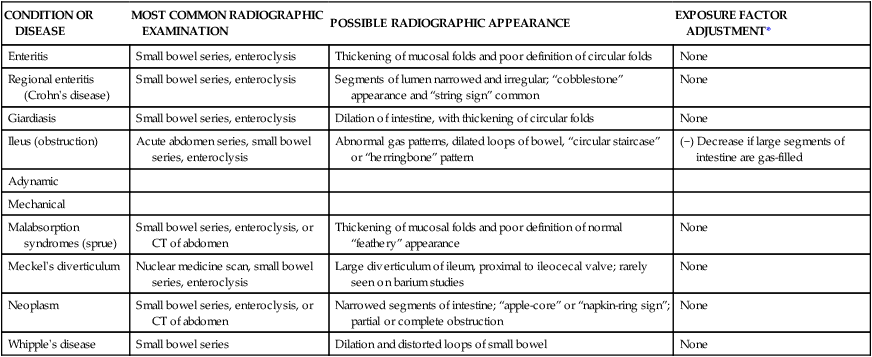

SMALL INTESTINE—SUMMARY OF CLINICAL INDICATIONS

| CONDITION OR DISEASE | MOST COMMON RADIOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION | POSSIBLE RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE | EXPOSURE FACTOR ADJUSTMENT* |

| Enteritis | Small bowel series, enteroclysis | Thickening of mucosal folds and poor definition of circular folds | None |

| Regional enteritis (Crohn's disease) | Small bowel series, enteroclysis | Segments of lumen narrowed and irregular; “cobblestone” appearance and “string sign” common | None |

| Giardiasis | Small bowel series, enteroclysis | Dilation of intestine, with thickening of circular folds | None |

| Ileus (obstruction) | Acute abdomen series, small bowel series, enteroclysis | Abnormal gas patterns, dilated loops of bowel, “circular staircase” or “herringbone” pattern | (−) Decrease if large segments of intestine are gas-filled |

| Adynamic | |||

| Mechanical | |||

| Malabsorption syndromes (sprue) | Small bowel series, enteroclysis, or CT of abdomen | Thickening of mucosal folds and poor definition of normal “feathery” appearance | None |

| Meckel's diverticulum | Nuclear medicine scan, small bowel series, enteroclysis | Large diverticulum of ileum, proximal to ileocecal valve; rarely seen on barium studies | None |

| Neoplasm | Small bowel series, enteroclysis, or CT of abdomen | Narrowed segments of intestine; “apple-core” or “napkin-ring sign”; partial or complete obstruction | None |

| Whipple's disease | Small bowel series | Dilation and distorted loops of small bowel | None |

*Dependent on stage or severity of disease or condition.

Small Bowel Procedures

Four methods are used to study the small intestine radiographically. Methods 1 and 2 are the more common methods. Methods 3 and 4 are special small bowel studies that are performed only when methods 1 and 2 are unsatisfactory or contraindicated.

Contrast Media

A thin mixture of barium sulfate is used for most small bowel series. When perforated bowel is suspected or when surgery is scheduled to follow the small bowel series, a water-soluble, iodinated contrast medium may be given. If the patient exhibits hypomotility of the bowel, ice water or another stimulant may be provided to promote the transit of barium. Also, water-soluble, iodinated contrast medium can be added to the barium to increase peristalsis and transit time of contrast media through the small intestine.

Upper Gi–small Bowel Combination

For an upper GI–small bowel combination procedure, a routine upper GI series is performed first. After the routine stomach study is completed, progress of the barium is followed through the entire small bowel. During a routine upper GI series, the patient generally should ingest one full cup, or 8 oz, of barium sulfate mixture. For any small bowel examination, the time the patient ingested this barium should be noted for timing of sequential radiographs. However, some departments begin timing after ingestion of the second cup.

After completion of fluoroscopy and routine radiography of the stomach, the patient is given 1 additional cup of barium to ingest. The time this is finished should be noted. A posteroanterior PA radiograph of the proximal small bowel is obtained 30 minutes following the initial barium ingestion. The PA projection is preferred over the AP to allow for compression of abdomen, which will produce some separation of the loops of intestine. This first radiograph of the small bowel series (marked “30 minutes”) is commonly obtained about 15 minutes after the upper GI series has been completed.

Radiographs are obtained at specific intervals throughout the small bowel series until the barium sulfate column passes through the ileocecal valve and progresses into the ascending colon. For the first 2 hours in the small bowel series, radiographs are usually obtained at 15-minute to 30-minute intervals. If the examination needs to be continued beyond the 2-hour time frame, radiographs are usually obtained every hour until barium passes through the ileocecal valve. (See Procedure Summary on upper right.)

The region of the terminal ileum and the ileocecal valve generally is studied fluoroscopically. Spot filming of the terminal ileum usually indicates completion of the examination.

The patient shown in Fig. 13-25 is in position under the compression cone, which, when lowered against the abdomen, spreads out loops of ileum to visualize the ileocecal valve better.

Small Bowel–only Series

The second possibility for study of the small intestine is the small bowel–only series, as summarized on the right. For every contrast medium examination, including the small bowel series, a radiograph of the abdomen should be obtained before the contrast medium is introduced.

For the small bowel–only series, the patient generally ingests two cups (16 oz) of barium, and the time is noted. Depending on departmental protocol, the first radiograph is taken 15 minutes or 30 minutes after completion of barium ingestion. This first radiograph requires high centering to include the diaphragm. From this point on, the examination is exactly the same as the follow-up series of the upper GI. Radiographs generally are taken every half-hour for 2 hours followed by radiographs every hour thereafter until barium reaches the cecum or ascending colon.

NOTES: Some routines may include continuous half-hour imaging until the barium reaches the cecum.

In the routine small bowel series, regular barium sulfate ordinarily reaches the large intestine within 2 or 3 hours, but this time varies greatly among patients.

Fluoroscopy with spot imaging and use of a compression cone may provide options for better visualization of the ileocecal valve.

Enteroclysis—double-Contrast Small Bowel Procedure

A third method of small bowel study is the enteroclysis (en″-ter-ok′-li-sis) procedure, which is a double-contrast method that is used to evaluate the small bowel.

Enteroclysis describes the injection of a nutrient or medicinal liquid into the bowel. In the context of a radiographic small bowel procedure, it refers to a study wherein the patient is intubated under fluoroscopic control with a special enteroclysis catheter. This catheter is passed through the stomach into the duodenojejunal junction (ligament of Treitz). With fluoroscopy guidance, a duodenojejunal tube is placed into the terminal duodenum.

First, a high-density suspension of barium is injected through this catheter at a rate of 100 mL/min. Fluoroscopic and conventional radiographs may be taken at this time. Air or methylcellulose is injected into the bowel to distend it, which provides a double-contrast effect. Methylcellulose is preferred because it adheres to the bowel while distending it. This double-contrast effect dilates the loops of small bowel, while enhancing visibility of the mucosa. This action leads to increased accuracy of the study.

Disadvantages of enteroclysis include increased patient discomfort and the possibility of bowel perforation during catheter placement.

Enteroclysis is indicated for patients with clinical histories of small bowel ileus, regional enteritis (Crohn's disease), or malabsorption syndrome.

When the small bowel has been successfully filled with contrast medium, the radiologist typically takes fluoroscopy spot images. The technologist may be asked to produce various projections of the small bowel, including AP, PA, oblique, and possibly erect projections.

When the procedure has been completed, the catheter is removed, and the patient is encouraged to increase his or her water intake for the day. Laxatives may also be recommended to promote evacuation of the barium sulfate.

The radiograph seen in Fig. 13-26 is an example of an enteroclysis. The end of the catheter (small arrows) is seen in the distal duodenum, not yet reaching the duodenojejunal junction (ligament of Treitz; large upper arrow). The introduction of methylcellulose dilates the lumen of the bowel, and barium coats the mucosa.

Many departments perform a dual-modality procedure in which the duodenojejunal tube is inserted and contrast medium is instilled under fluoroscopic guidance. After the initial fluoroscopy has been performed, the patient undergoes a CT scan of the gastrointestinal tract to detect any obstructions or adhesions (Fig. 13-27).

Intubation Method—single-Contrast Study

The fourth and final method of small bowel study is gastrointestinal intubation (in″-tu-ba′-shun), sometimes referred to as a small bowel enema. With this technique, a nasogastric tube is passed through the patient's nose, through the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, and into the jejunum (Fig. 13-28). This radiograph shows the end of the tube (small arrows) still looped in the lower part of the stomach, having not yet passed into the duodenum. The distended air-filled loops of small bowel demonstrating air-fluid levels indicate some type of small bowel obstruction.

This procedure is performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The diagnostic intubation procedure may be referred to as a small bowel enema. A single-lumen tube is passed into the proximal jejunum. Placing the patient into a right anterior oblique (RAO) position may aid in passage of the tube from the stomach into the duodenum by gastric peristaltic action. A water-soluble iodinated agent or a thin barium sulfate suspension is injected through the tube. Radiographs are taken at timed intervals similar to in a standard small bowel series.

The therapeutic intubation procedure is performed often to relieve postoperative distention or to decompress a small bowel obstruction. A double-lumen catheter, termed a Miller-Abbott (M-A) tube, is advanced into the stomach. Radiopaque materials often are incorporated into the design of the catheter to assist during fluoroscopy-guided placement. Through peristalsis, the catheter is advanced into the jejunum. The technologist may be asked to take radiographs at timed intervals to determine whether the catheter is advancing. Gas and excessive fluids can be withdrawn through the catheter.

An optional part of this study may include fluoroscopy, whereby the tube can be guided into the duodenum through the use of compression and manual manipulation.

Patient Preparation

Patient preparation for a small bowel series is identical to preparation for an upper GI series. The most common method of small bowel study consists of a combination of the two examinations into one long examination, with the small bowel series following the upper GI series.

The goal of patient preparation for the upper GI series or the small bowel series is an empty stomach. Food and fluid must be withheld for at least 8 hours before these examinations are performed. Ideally, the patient should be on a low-residue diet 48 hours before the small bowel series is conducted. In addition, the patient should not smoke cigarettes or chew gum during the NPO period. Before the procedure is performed, the patient should be asked to void, so as not to cause displacement of the ileum secondary to a distended bladder.

Pregnancy Precautions

If the patient is female, a menstrual history must be obtained. Irradiation of an early pregnancy is one of the most hazardous situations in diagnostic radiography. X-ray examinations such as the small bowel series or the barium enema that include the pelvis and uterus in the primary beam should not be performed on pregnant women unless absolutely necessary. If the patient is unsure whether she may be pregnant, the technologist should bring this to the attention of the radiologist. A pregnancy test may be ordered before the procedure.

Method of Imaging

Image receptor (IR) of 35 × 43 cm (14 × 17 inch) is commonly used to visualize as much of the small intestine as possible on “overhead” radiographs. Spot imaging of selected portions of the small bowel may use smaller IRs.

The prone position is most appropriate for a small bowel series unless the patient is unable to assume that position. The prone position allows abdominal compression to separate the various loops of bowel, creating a higher degree of visibility. Asthenic patients may be placed in the Trendelenburg position to separate overlapping loops of ileum.

For the 30-minute image, the IR is placed high enough to include the stomach on the radiograph. This placement often requires longitudinal centering to the duodenal bulb and side-to-side centering to the midsagittal plane. Approximately three-fourths of the IR should extend above the iliac crest. Because most of the barium is in the stomach and proximal small bowel, a high-kV (100 to 125 kV) technique should be used on this initial radiograph.

All radiographs after the initial 30-minute exposure should be centered to the iliac crest. For the 1-hour and later radiographs, 85 to 95 kV settings may be used because the barium is spread through more of the alimentary canal and is not concentrated in the stomach. Fluoroscopic spot imaging of the terminal ileum usually completes the examination.

Barium Enema (Lower GI Series)

Contraindications

The two strict contraindications for the barium enema are similar to the contraindications described for the small bowel series. These have been described as a possible perforated hollow viscus and a possible large bowel obstruction. These patients should not be given barium as a contrast medium. Although not as radiopaque as barium sulfate, water-soluble contrast media can be used for these conditions.

Careful review of the patient's chart and clinical history may help to prevent problems during the procedure. The radiologist should be informed of any conditions or disease processes noted in the patient's chart. This information may dictate the type of study performed.

It is also important to review the patient's chart to determine whether the patient has had a recent sigmoidoscopy or a colonoscopy before undergoing the barium enema. If a biopsy of the colon was performed during these procedures, the involved section of the colon wall may be weakened. This may lead to perforation during the barium enema. The radiologist must be informed of this situation before beginning the procedure.

Clinical Indications for Barium Enema

Common clinical indications for barium enema include the following.

Colitis (ko-li′-tis) is an inflammatory condition of the large intestine that may be caused by many factors, including bacterial infection, diet, stress, and other environmental conditions. The intestinal mucosa may appear rigid and thick and lack haustral markings along the involved segment. Because of chronic inflammation and spasm, the intestinal wall has a “saw-tooth” or jagged appearance.

Ulcerative colitis is a severe form of colitis that is most common among young adults. It is a chronic condition that often leads to development of coinlike ulcers within the mucosal wall. Along with Crohn's disease, it is one of the most common forms of inflammatory bowel disease. These ulcers may be seen during a barium enema as multiple ring-shaped filling defects that create a “cobblestone” appearance along the mucosa. Patients with long-term bouts of ulcerative colitis may develop “stovepipe” colon, in which haustral markings and flexures are absent.

A diverticulum (di″-ver-tik′-u-lum) is an outpouching of the mucosal wall that may result from herniation of the inner wall of the colon. Although this is a relatively benign condition, it may become widespread throughout the colon, specifically the sigmoid colon. It is most common among adults older than 40 years of age.

The condition of having numerous diverticula is termed diverticulosis. If these diverticula become infected, the condition is referred to as diverticulitis. Inflamed diverticula may become a source of bleeding, in which case surgical removal may be necessary. A patient may develop peritonitis if a diverticulum perforates the mucosal wall permitting fecal matter to escape.

Diverticula appear as small, barium-filled, circular defects that project outward from the colon wall during a barium enema (see small arrows in Fig. 13-31). The double-contrast barium enema provides an excellent view of the intestinal mucosa, revealing small diverticula. Double-contrast barium enema clearly demonstrates the presence of most diverticula.

Intussusception (in″-ta-sa-sep′-shan) is a telescoping or invagination of one part of the intestine into another. It is most common in infants younger than 2 years of age but can occur in adults. A barium enema or an air/gas enema may play a therapeutic role in re-expanding the involved bowel. Radiographically, progression of the barium through the colon terminates at a “mushroom-shaped” dilation. Very little barium/gas, if any, passes beyond this area. The dilation marks the point of obstruction. Intussusception must be resolved quickly so that it does not lead to obstruction and necrosis of the bowel (see Chapter 16). If the condition recurs, surgery may be necessary.

Neoplasms are common in the large intestine. Although benign tumors do occur, carcinoma of the large intestine is a leading cause of death among both men and women. Most carcinomas of the large intestine occur in the rectum and sigmoid colon. These cancerous tumors often encircle the lumen of the colon, producing an irregular channel through it. The radiographic appearance of these tumors, as demonstrated during a barium enema, has led to the use of descriptive terms such as “apple-core” or “napkin-ring” lesions. Both benign and malignant tumors may begin as polyps.

Annular carcinoma (adenocarcinoma), one of the most typical forms of colon cancer, may form an “apple-core” or “napkin-ring” appearance as the tumor grows and infiltrates the bowel walls. It frequently results in large bowel obstruction.

Polyps are saclike projections similar to diverticula except that they project inward into the lumen rather than outward, as do diverticula. Similar to diverticula, polyps can become inflamed and may be a source of bleeding. In this case, they may have to be surgically removed. Barium enema, endoscopy, and CT colonography are the most effective modalities used to demonstrate neoplasms in the large intestine.

Volvulus (vol′-vu-lus) is a twisting of a portion of the intestine on its own mesentery, leading to a mechanical type of obstruction. Blood supply to the twisted portion is compromised, leading to obstruction and localized death of tissue. A volvulus may be found in portions of the jejunum or ileum. This can also occur in the cecum and sigmoid colon. Volvulus is more likely to occur in men than in women and is most common in adults 20 to 50 years old. The classic sign is a “beak” sign—a tapered narrowing at the volvulus site as demonstrated during a barium enema. A volvulus produces an air-fluid level, which is well demonstrated on an erect abdomen projection.

Cecal volvulus describes the ascending colon and the cecum as having a long mesentery, which makes them more susceptible to a volvulus.

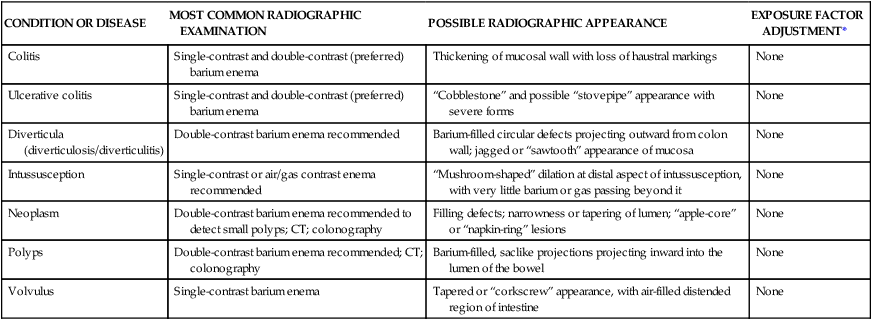

LARGE INTESTINE—SUMMARY OF CLINICAL INDICATIONS

| CONDITION OR DISEASE | MOST COMMON RADIOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION | POSSIBLE RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE | EXPOSURE FACTOR ADJUSTMENT* |

| Colitis | Single-contrast and double-contrast (preferred) barium enema | Thickening of mucosal wall with loss of haustral markings | None |

| Ulcerative colitis | Single-contrast and double-contrast (preferred) barium enema | “Cobblestone” and possible “stovepipe” appearance with severe forms | None |

| Diverticula (diverticulosis/diverticulitis) | Double-contrast barium enema recommended | Barium-filled circular defects projecting outward from colon wall; jagged or “sawtooth” appearance of mucosa | None |

| Intussusception | Single-contrast or air/gas contrast enema recommended | “Mushroom-shaped” dilation at distal aspect of intussusception, with very little barium or gas passing beyond it | None |

| Neoplasm | Double-contrast barium enema recommended to detect small polyps; CT; colonography | Filling defects; narrowness or tapering of lumen; “apple-core” or “napkin-ring” lesions | None |

| Polyps | Double-contrast barium enema recommended; CT; colonography | Barium-filled, saclike projections projecting inward into the lumen of the bowel | None |

| Volvulus | Single-contrast barium enema | Tapered or “corkscrew” appearance, with air-filled distended region of intestine | None |

*Dependent on stage or severity of disease or condition.

Barium Enema Procedure

Patient Preparation

Preparation of the patient for a barium enema is more involved than preparation of the stomach and small bowel. However, the final objective is the same. The section of alimentary canal to be examined must be empty. Thorough cleansing of the entire large bowel is of paramount importance for a satisfactory contrast media study of the large intestine.

Contraindications to Laxatives (Cathartics)

Certain conditions contraindicate the use of very effective cathartics or purgatives needed to cleanse the large bowel thoroughly. These conditions include (1) gross bleeding, (2) severe diarrhea, (3) obstruction, and (4) inflammatory conditions such as appendicitis.

A laxative is a substance that produces frequent soft or liquid bowel movements. These substances increase peristalsis in the large bowel and occasionally in the small bowel as well by irritating sensory nerve endings in the intestinal mucosa. This increased peristalsis dramatically accelerates the passage of intestinal contents through the digestive system.

Two Classes of Laxatives

Two different classes of laxatives may be prescribed. First are irritant laxatives, such as castor oil; second are saline laxatives, such as magnesium citrate or magnesium sulfate. The use of irritant laxatives is rare today. For best results, bowel-cleansing procedures should be specified on patient instruction sheets for both inpatients and outpatients. The technologist should be completely familiar with the type of preparation used in each radiology department. The importance of a clean large intestine for a barium enema, especially for a double-contrast barium enema, cannot be overstated. Any retained fecal matter may obscure the normal anatomy or may yield false diagnostic information, leading to rescheduling of the procedure after the large intestine has been properly cleaned.

Radiographic Room Preparation

The radiographic room should be prepared in advance of the patient's arrival. The fluoroscopy room and the examination table should be clean and tidy for each patient. The control panel should be set for fluoroscopy, with the appropriate technical factors selected. The fluoroscopy timer may be set up to its maximum time, which is usually 5 minutes. If conventional fluoroscopy is used, the photo-spot mechanism should be in proper working order, and a supply of spot film cassettes should be handy. The anticipated number of needed IRs for postprocedure “overhead” images should be set aside. Protective lead aprons and lead gloves should be available for the radiologist, and lead aprons should be available for all other personnel present in the room. The fluoroscopic table should be placed in the horizontal position, with waterproof backing or disposable pads placed on the tabletop. Waterproof protection is essential in cases of premature evacuation of the contrast material.

The Bucky tray must be positioned at the foot end of the table, if the fluoroscopy tube is located beneath the tabletop. This expands the Bucky slot shield, reducing gonadal dose to the fluoroscopist, as described in Chapter 12 (see Fig. 12-59). The radiation foot control switch should be placed appropriately for the radiologist, or the remote control area should be prepared. Tissues, towels, replacement linen, bedpan, extra gowns, a room air freshener, and a waste receptacle should be readily available. The appropriate contrast medium or media, container, tubing, and enema tip should be prepared. A proper lubricant should be provided for the enema tip. The type of barium sulfate used and the concentration of the mixture vary considerably, depending on radiologist preferences and the type of examination to be performed.

Equipment and Supplies

A closed-system enema container is used to administer barium sulfate or an air and barium sulfate combination during the barium enema (Fig. 13-36). This closed-type, disposable barium enema bag system has replaced the older open-type system for convenience and for reducing the risk of cross-infection.

This system, which is shown in the photograph, includes the disposable enema bag with a premeasured amount of barium sulfate. Once mixed, the suspension travels down its own connective tubing. Flow is controlled by a plastic stopcock. An enema tip is placed on the end of the tubing and is inserted into the patient's rectum.

After the examination has been completed, much of the barium can be drained back into the bag by lowering the system to below tabletop level. The entire bag and tubing are disposed of after a single use.

Various types and sizes of enema tips are available (Fig. 13-37). The three most common enema tips are (A) plastic disposable, (B) rectal retention, and (C) air-contrast retention enema tips. All are considered single-use, disposable enema tips.

Rectal disposable retention tips (B and C), sometimes called retention catheters, are used on patients who have relaxed anal sphincters or who cannot for whatever reason retain the contrast material. Rectal retention catheters consist of a double-lumen tube with a thin rubber balloon at the distal end. After rectal insertion, this balloon is carefully inflated with air through a small tube to assist the patient in retaining the barium enema. These retention catheters should be fully inflated only under fluoroscopic guidance provided by the radiologist because of the potential danger of intestinal rupture. To prevent discomfort for the patient, the balloon should not be fully inflated until the fluoroscopic procedure begins.

A special type of rectal tip (C) is needed to inject air through a separate tube into the colon. The air mixes with the barium to produce a double-contrast barium enema examination.

Latex Allergies

Today, most products are primarily latex-free, but identifying whether the patient is sensitive to natural latex products is still important. Patients with sensitivity to latex experience anaphylactoid-type reactions that include sneezing, redness, rash, difficulty in breathing, and even death.

If the patient has a history of latex sensitivity, the technologist must ensure the enema tip, tubing, and gloves are latex-free. Even dust produced from removal of latex gloves can introduce latex protein into the air, which may be inhaled by the patient.

Technologists with latex sensitivity must be keenly aware of the types of gloves, catheters, and other latex devices found in the department. If a rash develops while the technologist is wearing gloves or handling certain objects, he or she should consult a physician to explore the possibility of latex sensitivity.

Contrast Media

Barium sulfate is the most common type of positive-contrast medium used for the barium enema. The concentration of the barium sulfate suspension varies according to the study performed. A standard mixture used for single-contrast barium enemas is between 15% and 25% weight-to-volume (w/v). The thicker barium used for double-contrast barium enemas has a weight-to-volume concentration between 75% and 95% or greater. The barium sulfate solution introduced during a CT scan of the large intestine possesses a low w/v to prevent artifacts that may obscure anatomy from being produced. The evacuative proctogram (see p. 508) requires a contrast medium with a minimum w/v of 100%.

The double-contrast study uses numerous negative-contrast agents, in addition to barium sulfate. Room air, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide are the most common forms of negative-contrast media used. Carbon dioxide is gaining wide use because it is well tolerated by the large intestine and is absorbed rapidly after the procedure. Carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas are stored in a small tank and can be introduced into the rectum through an air-contrast retention enema tip.

An iodinated, water-soluble contrast medium may be used in the case of a perforated or lacerated intestinal wall. It may also be used when the patient is scheduled for surgery after the imaging procedure. An 85 to 95 kVp range should be used with a water-soluble, negative-contrast agent.

The mixing instructions as supplied by the manufacturer should be followed precisely.

A debate has evolved over the temperature of the water used to prepare the barium sulfate suspension. Some experts recommend the use of cold water (40°F to 45°F) in the preparation of contrast media. Cold water is reported to have an anesthetic effect on the colon and to increase the retention of contrast media. Critics have stated that the use of cold water may lead to colonic spasm.

Room-temperature water (85°F to 90°F) is recommended by most experts for completion of a more successful examination with maximal patient comfort. The technologist should never use hot water to prepare contrast media. Hot water may scald the mucosal lining of the colon.

Because barium sulfate produces a colloidal suspension, shaking the enema bag before tip insertion is important for preventing separation of barium sulfate from water.

Spasm during the barium enema is a common side effect. Patient anxiety, overexpansion of the intestinal wall, discomfort, and related disease processes all may lead to colonic spasm. To minimize the possibility of spasm, a topical anesthetic such as lidocaine may be added to the contrast medium. If spasm does occur during the study, glucagon can be given intravenously and should be kept in the department for these situations.

Procedure Preparation

A patient undergoing a barium enema should be dressed in an appropriate hospital gown. A cotton gown with the opening and ties in the back is preferable. The type of gown that must be pulled over the patient's head for removal should never be used. Sometimes the gown becomes soiled during the examination and must be changed. An outpatient should be instructed to remove all clothing, including shoes and socks or pantyhose. Disposable slippers should be provided in case some barium is lost on the way to the restroom.

After the fluoroscopic room and the contrast media have been completely prepared, the patient is escorted to the examination room. First, the patient history should be taken, and the examination should be carefully explained. Because complete cooperation is essential and this examination can be embarrassing, extra effort should be made to communicate thoroughly with the patient at every stage of the examination.

Previous radiographs should be made available to the radiologist. The patient is placed in Sims' position before the enema tip is inserted.

Sims' position is shown in Fig. 13-39. The patient is asked to roll onto the left side and lean forward. The right leg is flexed at the knee and hip and is placed in front of the left leg. The left knee is comfortably flexed. Sims' position relaxes the abdominal muscles and decreases pressure within the abdomen.

Each phase of the rectal tube insertion must be explained to the patient. Before insertion, the barium sulfate solution should be well mixed and a little of the barium mixture run into a waste receptacle to ensure no air remains in the tubing or enema tip.

Preparation for Rectal Tip Insertion

The technologist must don protective gloves. The rectal tip is well lubricated with a water-soluble lubricant.

Before the rectal tip is inserted, the patient should be instructed (1) not to push the tip out of the rectum by bearing down once the tip is inserted, (2) to relax the abdominal muscles to prevent increased intra-abdominal pressure, and (3) to concentrate on breathing by mouth to reduce spasms and cramping. The patient must be assured that the barium flow will be stopped if cramping occurs.

Enema Tip Insertion

Before the enema tip is inserted, the opening in the back of the patient's gown should be adjusted to expose only the anal region. The rest of the patient should be well covered when the rectal tube is inserted. The patient's modesty should be protected in every way possible during the barium enema examination. The right buttock should be raised to open the gluteal fold and expose the anus. The patient should take in a few deep breaths before actual insertion of the enema tip. If the tip will not enter with gentle pressure, the patient should be asked to relax and assist if possible. The tip should never be forced in a manner that could cause injury to the patient. Because the abdominal muscles relax on expiration, the tip should be inserted during the exhalation phase of respiration.

The rectum and anal canal present a double curvature; the tube is inserted first in a forward direction approximately 2.5 to 4 cm (1 to  inches). This initial insertion should be aimed toward the umbilicus. After the initial insertion, the rectal tube is directed superiorly and slightly anteriorly to follow the normal curvature of the rectum. The total insertion of the tip should not exceed 3 to 4 cm (

inches). This initial insertion should be aimed toward the umbilicus. After the initial insertion, the rectal tube is directed superiorly and slightly anteriorly to follow the normal curvature of the rectum. The total insertion of the tip should not exceed 3 to 4 cm ( to

to  inches) to prevent possible injury to the wall of the rectum. The rectal tube may be taped in place or held to prevent it from slipping out while the patient turns back into a supine position for the start of fluoroscopy. This position is usually supine but may be prone, depending on the preference of the radiologist.

inches) to prevent possible injury to the wall of the rectum. The rectal tube may be taped in place or held to prevent it from slipping out while the patient turns back into a supine position for the start of fluoroscopy. This position is usually supine but may be prone, depending on the preference of the radiologist.

If the retention-type tip is necessary, most departments allow the technologist to instill one or two puffs of air into the balloon end to help hold it in place. However, the bulb should be filled to its maximum only under fluoroscopic control as the fluoroscopy procedure begins. As the procedure begins, the intravenous pole supporting the enema bag should be no higher than 60 cm (24 inches) above the radiographic table.

Fluoroscopy Routine

NOTE: The following routine may differ for countries or facilities in which the expanded scope of technologists includes barium enema fluoroscopy.

The fluoroscopist is summoned to the radiographic room after all room and patient preparations have been completed. Following introduction of the physician and the patient, the patient's history and the reason for the examination are discussed.

During barium enema fluoroscopy, the general duties of the technologist are to follow the radiologist's instructions, assist the patient as needed, and expedite the procedure in any way possible. The technologist also must control the flow of barium or air and must change fluoroscopy spot cassettes (when used). The flow of barium is started and stopped several times during the barium enema. Each time the fluoroscopist asks the flow be started, the technologist should say “barium on” after the clamp or hemostat is released. Each time the fluoroscopist requests that the flow be stopped, the technologist should say “barium off” after the tubing is clamped.

Many changes in patient position are made during fluoroscopy. These positional changes are made to visualize superimposed sections of bowel better and aid in advancement of the barium column. The technologist may have to assist the patient with positional moves and ensure the tubing is not kinked or accidentally pulled out during the examination.

The fluoroscopic procedure begins with a general survey of the patient's abdomen and chest. For some departmental routines, if the retention-type enema tip is required, the air balloon may be inflated under fluoroscopic control at this point.

Various spot radiographs of selected portions of the large intestine are obtained as the barium column proceeds in retrograde fashion from rectum to cecum. At the end of the fluoroscopic procedure, a little barium is refluxed through the ileocecal valve, and fluoroscopy images of that area are obtained. Moderate discomfort usually is experienced when the large bowel is totally filled, so the examination must be concluded as rapidly as possible.

Routine “overhead” radiographs may be requested with the bowel filled.

Single-Contrast Barium Enema Procedure

The single-contrast barium enema is a procedure in which only positive-contrast media are used. In most cases, the contrast material is barium sulfate in a thin mixture. Occasionally, the contrast media must be a water-soluble contrast material. For example, if the patient is scheduled for surgery after undergoing the single-contrast enema procedure, a water-soluble contrast medium must be used.

An example of a single-contrast barium enema in which barium sulfate was used as the contrast medium is shown in Fig. 13-42.

Double-Contrast Barium Enema Procedure

A second common type of barium enema procedure is the double-contrast type. Double-contrast studies are more effective in demonstrating polyps and diverticula than single-contrast studies. Radiographic and fluoroscopic procedures for a double-contrast barium enema are different in that both air and barium must be introduced into the large bowel. Fig. 13-43 shows a double-contrast barium enema radiograph taken in the left lateral decubitus position. An absolutely clean large bowel is essential for a double-contrast study, and a much thicker barium mixture is required. Although exact ratios depend on the commercial preparations used, the ratio approaches a 1:1 mix, so that the final product is like heavy cream.

One preferred method used to coat the bowel is a two-stage, double-contrast procedure. Initially, the thick barium is allowed to fill the left side of the intestine, including the left colic flexure. (The purpose of the thick barium mixture is to facilitate adherence to the mucosal lining.) Air is instilled into the bowel, pushing the barium through to the right side. At this time, the radiologist may ask that the enema bag be lowered below the table to allow any excess barium to be drained from the large intestine to provide better visualization of the intestinal mucosa.

The second stage consists of inflation of the bowel with a large amount of air/gas. This air/gas moves the main bolus of barium forward, leaving behind only the barium adhering to the mucosal wall. These steps are carried out under fluoroscopic control because the air bolus should not be pushed in front of the barium bolus.

This procedure demonstrates neoplasms or polyps that may be forming on the inner surface of the bowel and projecting into the lumen or opening of the bowel. These formations generally would not be visible during a single-contrast barium enema study.

A single-stage, double-contrast procedure, wherein barium and air are instilled in a single procedure that reduces time and radiation exposure to the patient, also may be used. With this method, high-density barium is instilled into the rectum first with the patient in a slight Trendelenburg position. The barium tube is then clamped. With the table in a horizontal position, the patient is placed into various oblique and lateral positions after various amounts of air are added through the double-contrast procedure.

With digital fluoroscopy, these “spot” images are obtained digitally rather than with separate IRs. Images taken during the study are stored in the memory of the computer. Once the images have undergone quality assurance, they are transferred to the PACS (picture archiving and communications system) for interpretation. The radiologist can review all recorded images and print only the images that have diagnostic importance. With PACS, images can be reviewed, read, and stored within the database system without the need for hard-copy prints.

After fluoroscopy and before the patient is permitted to empty the large bowel, additional radiographs of the filled intestine may be obtained. The standard enema tip can be removed before these radiographs are taken when removal promotes retention of the contrast material, although some department protocols are to keep the enema tip in during the “overhead” imaging. The retention-type tip is generally not removed until the large bowel is ready to be emptied and the patient is placed on a bedpan or sent to the commode.

Fig. 13-44 demonstrates the most common position for a routine barium enema. This is the PA projection with a full-sized 35 × 43-cm (14 × 17-inch) IR centered to the iliac crest. The PA projection with the patient in a prone position is preferred over the AP projection in a supine position because compression of the abdomen in the prone position results in more uniform radiographic density of the entire abdomen.

The IR should be centered to include the rectal ampulla on the bottom of the image. This positioning usually includes the entire large intestine with the exception of the left colic flexure. Clipping the left colic flexure off the radiographs may be acceptable if this area is well demonstrated on a previously obtained spot film. However, some departmental routines may include a second image centered higher to include this area on larger patients, or two images, with IR placed crosswise.

Other projections are also obtained before evacuation of the barium. Double-contrast procedures generally require right and left lateral decubitus AP or PA projections, with a horizontal x-ray beam to demonstrate better the upside or air-filled portions of the large intestine.

NOTE: Because of the vast difference in density between the air-filled and barium-filled aspects of the large intestine, a tendency to overexpose the air-filled region may be noted. The recommendation is that the technologist consider using a compensating filter for the decubitus and ventral lateral projections taken during an air-contrast study. One version of a compensating filter that works well attaches to the face of the collimator with two small magnetic disks. The disks can be adjusted to place the filter over the air-filled portion of the large intestine.

All postfluoroscopy radiographs must be obtained as quickly as possible because the patient may have difficulty retaining the barium.

After the routine pre-evacuation radiographs and any supplemental radiographs have been obtained, the patient is allowed to expel the barium. For the patient who has had the enema tip removed, a quick trip to a nearby restroom is necessary. For the patient who cannot make such a trip, a bedpan should be provided. For the patient who is still connected to a closed system, simple lowering of the plastic bag to floor level to allow most of the barium to drain back into the bag is helpful. Department protocol determines how a retention tip should be removed. One way is first to clamp off the retention tip and then disconnect it from the enema tubing and container. When the patient is safely on a bedpan or commode, air is released from the bulb and the tip is removed.

After most of the barium has been expelled, a postevacuation radiograph is obtained. The postevacuation radiograph usually is taken in the prone position but may be taken supine if needed. Most of the barium should have been evacuated. If too much barium is retained, the patient is given more time for evacuation, and a second postevacuation image is obtained.

Postprocedure instructions to patients should include increased fluid intake and a high-fiber diet because of the possibility of constipation from the barium (most important for geriatric patients).

Evacuative Proctography—defecography

A third, less common type of radiographic study involving the lower gastrointestinal tract is evacuative proctography, sometimes called defecography. This study is a more specialized procedure that is performed in some departments, especially on children or younger adult patients.

Clinical indications for evacuative proctography include rectoceles, rectal intussusception, and prolapse of the rectum. A rectocele, a common form of the pathologic process, is a blind pouch of the rectum that is caused by weakening of the anterior or posterior wall. Rectoceles may retain fecal material even after evacuation.

A special commode is required for this study (Fig. 13-47). It consists of a toilet seat built onto a frame that contains a waste receptacle or a disposable plastic bag (A). The commode shown has wheels or casters (B) so that it can be rolled into position over the extended footboard and platform (C) attached to the tabletop (D). The entire commode with the patient can be raised or lowered by raising the tabletop with the attached footboard and commode during the procedure (arrows). Clamps (not shown in these photographs) should be used to secure the commode to the footboard platform for stability during the procedure. These clamps allow the commode to be attached to the footboard and raised as needed for use of the Bucky table and fluoroscopy unit. The seat often is cushioned (E) for patient comfort. The filters found beneath the seat (not shown) compensate for tissue differences and help maintain acceptable levels of density and contrast.

To study the process of evacuation, a very high-density barium sulfate mixture is required. Some departments produce their own contrast media by mixing barium sulfate with potato starch or commercially produced additives. The potato starch thickens the barium sulfate to produce a mashed potato consistency. The normal barium sulfate suspension evacuates too quickly to detect any pathologic processes.

A ready-to-use contrast medium, Anatrast, is available (Fig. 13-49). This contrast medium is premixed and packaged in a single-use tube. Some departments also introduce thick liquid barium, such as Polibar Plus or EZ-HD, before using Anatrast to evaluate the sigmoid colon and the rectum.

The mechanical applicator (Fig. 13-49) resembles a caulking gun used in the building industry. The premixed and prepackaged tube of Anatrast is inserted into the applicator, and a flexible tube with an enema tip is attached to the opened tip of the tube (B-1).

The thick liquid barium is drawn into a syringe and is inserted through a rectal tube and tip. In this example, an inner plastic tube (C) is being used after insertion into an outer rectal tube (D), to which the enema tip is attached. The syringe is used to instill the thick liquid contrast medium. The inner plastic tube is attached to the syringe filled with the liquid Polibar Plus or equivalent and is inserted within the rectal tube, to which is attached a standard enema tip for insertion into the rectum.

Labeled parts (Fig. 13-49) are as follows:

Evacuative Proctogram Procedure

With the patient in a lateral recumbent position on a cart, the contrast medium is instilled into the rectum with the applicator. A nipple marker (small BB) may be placed at the anal orifice.

The patient is quickly placed on the commode for filming during defecation. Lateral fluoroscopy images and standard radiographic projections are taken during the study. The lateral rectum position usually is preferred by most radiologists (Fig. 13-50).

The anorectal angle or junction must be demonstrated during the procedure. This angle represents alignment between the anus and the rectum that shifts between the rest and evacuation phases. The radiologist measures this angle during these phases to determine whether any abnormalities exist.

A lateral recumbent postevacuation radiograph is taken as the final part of this procedure (Fig. 13-51).

Summary of Evacuative Proctogram Procedure

1. Place radiographic table vertical and attach commode with clamps.

2. Prepare the appropriate contrast media according to department specifications.

3. Set up imaging equipment (fluoroscopy or digital recorder), or use digital fluoroscopy.

4. Ask patient to remove all clothing and change into a hospital gown.

5. Take a scout image using a conventional x-ray tube. (Scout image must include the region of the anorectal angle.)

6. Place patient in a lateral recumbent position on a cart and instill contrast media.

7. Position patient on the commode and take radiographs in the rest and strain phases, with patient in a lateral position.

8. Using fluoroscopy imaging devices or digital recorder, image patient during defecation.

Colostomy Barium Enema

A colostomy (ka-los′-ta-me) is the surgical formation of an artificial or surgical connection between two portions of the large intestine.

In the case of disease, tumor, or inflammatory processes, a section of the large intestine may have been removed or altered. Often, because of a tumor in the sigmoid colon or rectum, this part of the lower intestine is removed. The terminal end of the intestine is brought to the anterior surface of the abdomen, where an artificial opening is created. This artificial opening is termed a stoma.

In some cases, a temporary colostomy is performed to allow healing of the involved section of large intestine. The involved region is bypassed through the use of the colostomy. Once healing is complete, the two sections of the large intestine are reconnected. Fecal matter is discharged from the body via the stoma into a special appliance bag that is attached to the skin over the stoma. When healing is complete, an anastomosis (reconnection) of the two sections of the large intestine is performed surgically. For select patients, the colostomy is permanent because of the amount of large intestine removed or other factors.

Clinical Indications and Purpose

The clinical indication or purpose for the colostomy barium enema is to assess for proper healing, obstruction, or leakage or to perform a presurgical evaluation. Sometimes, in addition to the colostomy barium enema, another enema may be given rectally at the same time. This type of study evaluates the terminal large intestine before it is reconnected surgically.

Special Supplies for Colostomy Barium Enema

Ready-to-use colostomy barium enema kits (Fig. 13-52) are available that contain stoma tips, tubing, a premeasured barium enema bag, adhesive disks, lubricant, and gauze. Because the stoma has no sphincter with which to retain the barium, a tapered irrigation tip is inserted into the stoma. Once the irrigation tip has been inserted, a special adhesive pad holds it in place. The enema bag tubing is attached directly to the irrigation tip.

Small balloon retention catheters (Fig. 13-53) can be used instead of the tapered irrigation tip. Care must be taken during insertion and inflation of these catheters. The stoma is delicate and can be perforated if too much pressure is applied. Most departments require the radiologist to perform this task.

Patient Preparation

If the barium enema is used for nonacute reasons, the patient is asked to irrigate the ostomy before undergoing the procedure. The patient may be asked to bring an irrigation device and additional appliance bags. The patient should follow the same dietary restrictions required for the standard barium enema.

Procedure