Systemic Diseases Manifested in the Jaws

Definition

Disorders of the endocrine system, bone metabolism, and other systemic diseases may have an effect on the form and function of bone and teeth. The function of bone not only includes support, protection, and an environment for hemopoiesis but also serves as a major reserve of calcium for the body. More than 99% of the total body calcium is contained within the skeletal structure. When the influence of systemic conditions on the jaws is considered, it is important to bear in mind that bone is constantly remodeling. Approximately 5% to 10% of the total bone mass is replaced each year. The turnover rate of trabecular bone is higher than for cortical bone; 20% of its mass is replaced per year compared with 5% for cortical bone. The effects of systemic diseases of bone are brought about by changes in the number and activity of osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes.

Radiographic Features

Because systemic disorders affect the entire body, the radiographic changes manifested in the jaws are generalized (Table 25-1). In most cases it is not possible to identify diseases on the basis of radiographic characteristics. The general changes include the following:

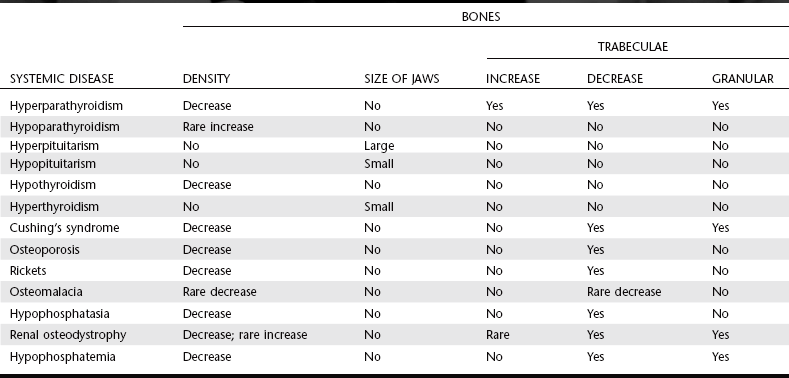

TABLE 25-1

Radiographic Changes in Bone Observed in Systemic Disease*

*This table summarizes the major radiographic changes to bone with endocrine and metabolic bone diseases. It does not include all the possible variable appearances.

1. A change in size and shape of the bone

2. A change in the number, size, and orientation of trabeculae

Changes in the first three elements can result in a decrease or increase in bone density.

Because many parameters in the production of a radiograph influence the density of the image, it may be difficult to detect genuine changes in the density of bone. Systemic conditions that result in a decrease in bone density do not affect mature teeth; therefore the image of the teeth may stand out with normal density against a generally radiolucent jaw. In severe cases the teeth may appear to be bereft of any bony support. Also, cortical structures appear thin, less defined, and occasionally disappear. On the other hand, a true increase in bone density may be detected by a loss of contrast of the inferior cortex of the mandible as the radiopacity of the cancellous bone approaches that of cortical bone. Often the inferior alveolar nerve canal appears more distinct in contrast to the surrounding dense bone.

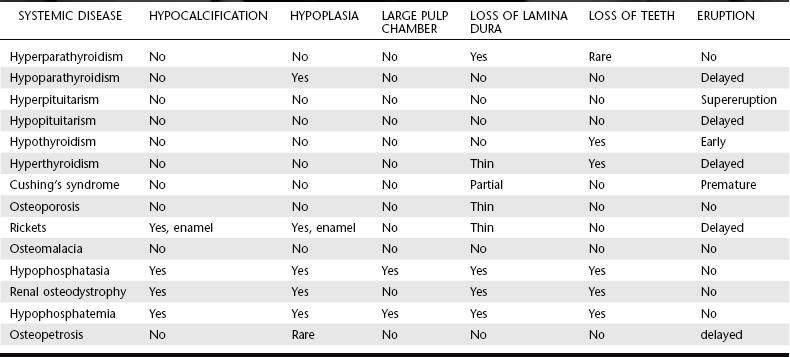

Some systemic diseases that occur during tooth formation may result in dental alterations. Lamina dura is part of the bone structure of the alveolar process, but because it is usually examined in conjunction with the periodontal membrane space and roots of teeth, it is included with the description of the dental structures (Table 25-2). Changes to teeth and associated structures include the following:

TABLE 25-2

Effects on Teeth and Associated Structures*

*This table summarizes the major radiographic changes that can occur to teeth and associated structures with endocrine and metabolic bone diseases. It does not include all the possible variable appearances.

Often bone and teeth exhibit no detectable radiographic changes associated with systemic diseases. However, on occasion the first symptoms of a disease may present as a dental problem.

Endocrine Disorders

Definition

Hyperparathyroidism is an endocrine abnormality in which there is an excess of circulating parathyroid hormone (PTH). An excess of serum PTH increases bone remodeling in preference of osteoclastic resorption, which mobilizes calcium from the skeleton. In addition, PTH increases renal tubular reabsorption of calcium and renal production of the active vitamin D metabolite 1,25(OH)2D. The net result of these functions is in an increase in serum calcium levels.

Primary hyperparathyroidism usually results from a benign tumor (adenoma) of one of the four parathyroid glands, resulting in the production of excess PTH. An abnormality named hyperparathyroidism–jaw tumor syndrome, which involves tumors of parathyroid glands, jaws, and kidneys, has been shown to have genetic basis. Less frequently, individuals may have hyperplastic parathyroid glands that secrete excess PTH. The combination of hypercalcemia and an elevated serum level of PTH is diagnostic of primary hyperparathyroidism. The incidence of primary hyperparathyroidism is about 0.1%.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism results from a compensatory increase in the output of PTH in response to hypocalcemia. The underlying hypocalcemia may result from an inadequate dietary intake or poor intestinal absorption of vitamin D or from deficient metabolism of vitamin D in the liver or kidney. This condition produces clinical and radiographic effects similar to those of primary hyperparathyroidism.

Clinical Features

Women are two to three times more commonly affected than men by primary hyperparathyroidism. The condition occurs mainly in those 30 to 60 years of age. Clinical manifestations of the disease cover a broad range, but most patients have renal calculi, peptic ulcers, psychiatric problems, or bone and joint pain. These clinical symptoms are mainly related to hypercalcemia. Gradual loosening, drifting, and loss of teeth may occur. Definite consistent hypercalcemia is virtually pathognomonic of primary hyperparathyroidism. (Rarely, multiple myeloma and metastatic tumors may produce the same serum alterations.) Because of daily fluctuations, the serum calcium level should be tested at different intervals. The serum alkaline phosphatase level, a reliable indicator of bone turnover, may also be elevated in hyperparathyroidism.

Radiographic Features

Only about one in five patients with hyperparathyroidism has radiographically observable bone changes.

General Radiographic Features.: The following are the major manifestations of hyperparathyroidism:

1. The earliest and most reliable changes of hyperparathyroidism are subtle erosions of bone from the subperiosteal surfaces of the phalanges of the hands.

2. Demineralization of the skeleton results in an unusual radiolucent appearance.

3. Osteitis fibrosa cystica are localized regions of bone loss produced by osteoclastic activity resulting in a loss of all apparent bone structure.

4. Brown tumors occur late in the disease and in about 10% of cases. These peripheral or central tumors of bone are radiolucent. The gross specimen has a brown or reddish-brown color.

5. Pathologic calcifications in soft tissues have a punctate or nodular appearance and occur in the kidneys and joints.

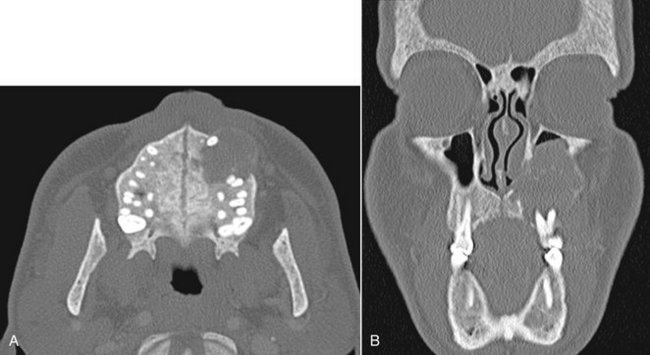

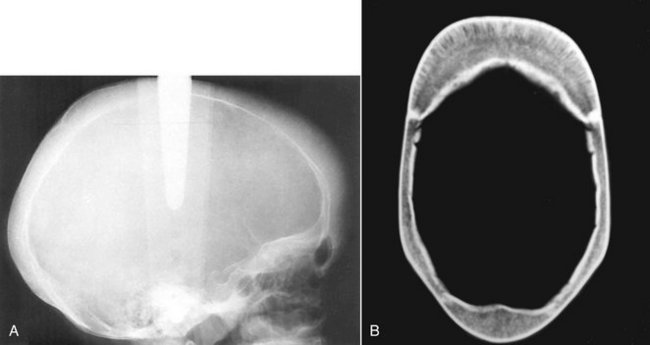

6. In prominent hyperparathyroidism, the entire calvarium has a granular appearance caused by the loss of central (diploic) trabeculae and thinning of the cortical tables (Fig. 25-1).

FIG. 25-1 A, Axial and, B, sagittal computed tomographic images with bone algorithm of a case of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Note the lack of normal cortical bone at the inner and outer tables of the skull, internal granular bone pattern, and generalized lack of defined outer cortical boundary of the osseous structures.

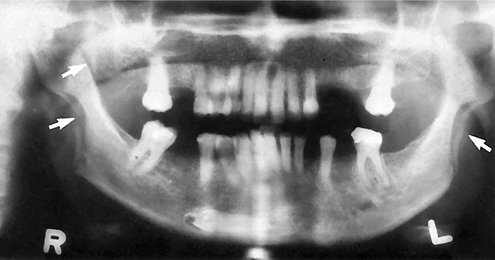

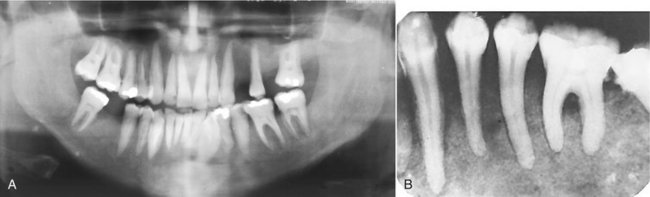

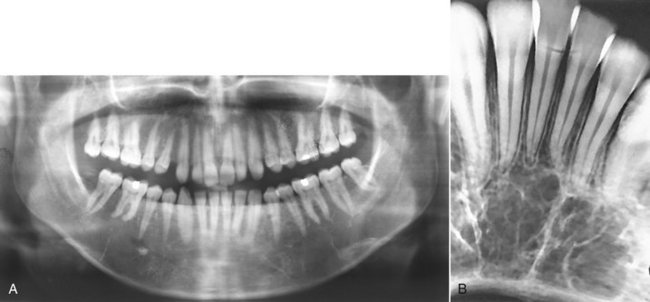

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: Demineralization and thinning of cortical boundaries often occur in the jaws in cortical boundaries such as the inferior border, mandibular canal, and the cortical outlines of the maxillary sinuses. The density of the jaws is decreased, resulting in a radiolucent appearance that contrasts with the density of the teeth. The teeth stand out in contrast to the radiolucent jaws (Fig. 25-2). A change in the normal trabecular pattern may occur, resulting in a ground-glass appearance of numerous, small, randomly oriented trabeculae.

FIG. 25-2 A, Panoramic image. The loss of bone in hyperparathyroidism results in the radiopaque teeth standing out in contrast to the radiolucent jaws. B, Note the loss of a distinct lamina dura and the granular texture of the bone pattern in this periapical film of a different case. (B courtesy H. G. Poyton, DDS, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism may appear in any bone but are frequently found in the facial bones and jaws, particularly in long-standing cases of the disease. These lesions may be multiple within a single bone. They have variably defined margins and may produce cortical expansion. If solitary, the tumor may resemble a central giant cell granuloma or an aneurysmal bone cyst (Fig. 25-3). It is interesting to note that the histologic appearance of the brown tumor is identical to that of the giant cell granuloma. Therefore if a giant cell granuloma occurs later than the second decade, the patient should be screened for an increase in serum calcium, PTH, and alkaline phosphatase levels.

FIG. 25-3 A, Axial and, B, coronal computed tomographic images with bone algorithm of a case of secondary hyperparathyroidism with a brown tumor involving the maxilla. This tumor has features of a central giant cell granuloma with a granular expanded cortex of the maxilla and very subtle and ill-defined internal septa.

Radiographic Features of the Teeth and Associated Structures.: Occasionally periapical radiographs reveal loss of the lamina dura in patients (only about 10%) with hyperparathyroidism. Depending on the duration and severity of the disease, loss of the lamina dura may occur around one tooth or all the remaining teeth (Fig. 25-4). The loss may be either complete or partial around a particular tooth. The result of lamina dura loss may give the root a tapered appearance because of loss of image contrast. Although PTH mobilizes minerals from the skeleton, mature teeth are immune to this systemic demineralizing process.

Management

After successful surgical removal of the causative parathyroid adenoma, almost all radiographic changes revert to normal. The only exception may be the site of a brown tumor, which often heals with bone that is radiographically more sclerotic than normal. Many people with this disease are being diagnosed earlier, resulting in fewer severe cases.

HYPOPARATHYROIDISM AND PSEUDOHYPOPARATHYROIDISM

Hypoparathyroidism is an uncommon condition in which insufficient secretion of PTH occurs. Several causes exist, but the most common is damage or removal of the parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery. In pseudohypoparathyroidism there is a defect in the response of the tissue target cells to normal levels of PTH.

Clinical Features

Both hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism produce hypocalcemia, which has a variety of clinical manifestations. Most often this includes sharp flexion (tetany) of the wrist and ankle joints (carpopedal spasm). Some patients have sensory abnormalities consisting of paresthesia of the hands, feet, or the area around the mouth. Neurologic changes may include anxiety and depression, epilepsy, parkinsonism, and chorea. Chronic forms may produce a reduction in intellectual capacity. Some patients show no changes at all. Patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism often have early closure of certain bony epiphyses and thus manifest short stature or extremity disproportions.

Radiographic Features

The principal radiographic change is calcification of the basal ganglia. On skull radiographs this calcification appears flocculent and paired within the cerebral hemispheres on the posteroanterior view. Radiographic examination of the jaws may reveal dental enamel hypoplasia, external root resorption, delayed eruption, or root dilaceration (Fig. 25-5).

HYPERPITUITARISM

Definition

Hyperpituitarism results from hyperfunction of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, which increases the production of growth hormone. An excess of growth hormone causes overgrowth of all tissues in the body still capable of growth. The usual cause of this problem is a benign functioning tumor of the acidophilic cells in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland.

Clinical Features

Hyperpituitarism in children involves generalized overgrowth of most hard and soft tissues, a condition termed giantism. Active growth occurs in those bones in which the epiphyses have not united with the bone shafts. Throughout adolescence, generalized skeletal growth is excessive and may be prolonged. Those affected may ultimately attain heights of 7 to 8 feet or more, yet exhibit remarkably normal proportions. The eyes and other parts of the central nervous system do not enlarge, except in rare cases in which the condition is manifested in infancy.

Adult hyperpituitarism, called acromegaly, has an insidious clinical course, quite different from the clinical profile seen in the childhood disease. In adults the clinical effects of a pituitary adenoma develop quite slowly because many types of tissues have lost the capacity for growth. This is true of much of the skeleton; however, an excess of growth hormone can stimulate the mandible and the phalanges of the hand. Mandibular condylar growth may be very prominent. Also, the supraorbital ridges and the underlying frontal sinus may be enlarged. Excess growth hormone in adults may also produce hypertrophy of some soft tissues. The lips, tongue, nose, and soft tissues of the hands and feet typically overgrow in adults with acromegaly, sometimes to a striking degree.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: The pituitary tumor responsible for hyperpituitarism often produces enlargement (“ballooning”) of the sella turcica (Fig 25-6, B). It is important to note that in some examples the sella may not expand at all. Skull radiographs characteristically reveal enlargement of the paranasal sinuses (especially the frontal sinus). These air sinuses are more prominent in acromegaly than in pituitary giantism because sinus growth in giantism tends to be more in step with the generalized enlargement of the facial bones. Hyperpituitarism in adults also produces diffuse thickening of the outer table of the skull.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: Hyperpituitarism causes enlargement of the jaws, most notably the mandible (Fig. 25-6, A). The increase in the length of the dental arches results in spacing of the teeth. In acromegaly the angle between the ramus and body of the mandible may increase. This, in combination with enlargement of the tongue (macroglossia), may result in anterior flaring of the teeth and the development of an anterior open bite. The sign of incisor flaring is a helpful point of differentiation between acromegalic prognathism and inherited prognathism. In acromegaly the most profound growth occurs in the condyle and ramus, often resulting in a class III skeletal relationship between the jaws. The thickness and height of the alveolar processes may also increase.

Radiographic Changes Associated with the Teeth.: The tooth crowns are usually normal in size, although the roots of posterior teeth often enlarge as a result of hypercementosis. This hypercementosis may be the result of functional and structural demands on teeth instead of a secondary hormonal effect. Supereruption of the posterior teeth may occur in an attempt to compensate for the growth of the mandible.

HYPOPITUITARISM

Clinical Features

Individuals with this condition show dwarfism but have relatively well-proportioned bodies. One study reported a marked failure of development of the maxilla and the mandible. The dimensions of these bones in adults with this disorder were approximately those of normal children 5 to 7 years of age.

Radiographic Features

Eruption of the primary dentition occurs at the normal time, but exfoliation is delayed by several years. The crowns of the permanent teeth form normally, but their eruption is delayed several years. The third molar buds may be completely absent. In hypopituitarism the jaws, especially the mandible, are small, which results in crowding and malocclusion.

HYPERTHYROIDISM

Definition

Hyperthyroidism is a syndrome that involves excessive production of thyroxin in the thyroid gland. This condition occurs most commonly with diffuse toxic goiter (Graves’ disease) and less frequently with toxic nodular goiter or toxic adenoma, a benign tumor of the thyroid gland. Each of these conditions results in increased levels of circulating thyroxine. Excessive thyroxine causes a generalized increase in the metabolic rate of all body tissues, resulting in tachycardia, increased blood pressure, sensitivity to heat, and irritability. Hyperthyroidism is more common in females.

HYPOTHYROIDISM

Definition

Hypothyroidism usually results from insufficient secretion of thyroxine by the thyroid glands despite the presence of thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Clinical Features

In children, hypothyroidism may result in retarded mental and physical development. The base of the skull shows delayed ossification, and the paranasal sinuses only partially pneumatize. Dental development is delayed, and the primary teeth are slow to exfoliate.

Hypothyroidism in the adult results in myxedematous swelling but not the dental or skeletal changes seen in children. Adult symptoms may range from lethargy, poor memory, inability to concentrate, constipation, and cold intolerance to the more florid clinical picture of dull and expressionless face, periorbital edema, large tongue, sparse hair, and skin that feels “doughy” to the touch.

Radiographic Features

Radiographic features in children include delayed closing of the epiphyses and skull sutures with the production of numerous wormian bones (accessory bones in the sutures). Effects on the teeth include delayed eruption, short roots, and thinning of the lamina dura. The maxilla and mandible are relatively small. Patients with adult hypothyroidism may show periodontal disease, loss of teeth, separation of teeth as a result of enlargement of the tongue, and external root resorption.

DIABETES MELLITUS

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder that has two primary forms. Type I, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (previously known as juvenile-onset diabetes), results from an absence or insufficiency of insulin, a hormone normally produced by the beta cells of the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Type II, non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, results from insulin resistance. Patients with type I diabetes have virtually no β cells (in the islets), whereas patients with type II diabetes have approximately half the normal number. A shortage of insulin adversely affects carbohydrate metabolism. The principal clinical laboratory signs of the disease are hyperglycemia and glycosuria, both reflecting a complex biochemical imbalance between tissue demand for glucose and the release of this nutrient by the liver.

Clinical Features

Untreated diabetes may manifest classic symptoms and signs such as polydipsia (excessive intake of fluids), polyuria (excessive urination), and, in more severe cases, acetone present in the urine and on the breath. This metabolic disorder, if not adequately treated, lowers the resistance of the body to infection. Diabetes may demonstrate a number of adverse effects in the oral cavity. Most prominently, uncontrolled diabetes acts as a continuing factor that predisposes to, aggravates, and accelerates periodontal disease. Patients with controlled diabetes do not appear to have more periodontal problems than do persons without diabetes. Some children with uncontrolled diabetes have an increased likelihood of caries activity because of a high-carbohydrate diet. Another occasional oral complication of diabetes mellitus is xerostomia resulting from a reduced salivary flow (about one third of normal). Recently diabetes has been documented as a risk factor in the development of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis.

CUSHING’S SYNDROME

Cushing’s syndrome arises from an excess of secretion of glucocorticoids by the adrenal glands. This may result from any of the following:

3. Adrenal hyperplasia (usually bilateral)

4. A basophilic adenoma of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland (Cushing’s disease), producing excess adrenocorticotropic hormone

The increased level of glucocorticoid results in a loss of bone mass from reduced osteoblastic function and either directly or indirectly increased osteoclastic function.

Clinical Features

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome often show obesity (which spares the extremities), kyphosis of the thoracic spine (“buffalo hump”), weakness, hypertension, striae, or concurrent diabetes. This condition affects females three to five times as frequently as males. Onset may occur at any age but is usually seen in the third or fourth decade.

Radiographic Features

The primary radiographic feature of Cushing’s syndrome is generalized osteoporosis, which may have a granular bone pattern. This demineralization may result in pathologic fractures. The skull can show diffuse thinning accompanied by a mottled appearance. The teeth may erupt prematurely, and partial loss of the lamina dura may occur (Fig. 25-7).

Metabolic Bone Diseases

Definition

Osteoporosis is a generalized decrease in bone mass in which the histologic appearance of bone is normal. An imbalance occurs in bone resorption and formation. Decrease in bone formation results in changes in trabecular architecture, the volume of trabecular bone, and the size and thickness of individual trabeculae.

Osteoporosis occurs with the aging process of bone and can be considered a variation of normal (primary osteoporosis). Bone mass normally increases from infancy to about 30 years of age. At this time there begins a gradual and progressive decline, occurring at the rate of about 8% per decade in women and 3% per decade in men. The loss of bone mass with age is so gradual that it is virtually imperceptible until it reaches significant proportions.

Secondary osteoporosis may result from nutritional deficiencies, hormonal imbalance, inactivity, or corticosteroid or heparin therapy.

Clinical Features

The most important clinical manifestation of osteoporosis is fracture. The most common locations are the distal radius, proximal femur, ribs, and vertebrae. Patients may have bone pain. The population most at risk is postmenopausal women.

Radiographic Features

Osteoporosis results in an overall reduction in the density of bone. This reduction may be observed in the jaws by using the unaltered density of teeth as a comparison. There may be evidence of a reduced density and thinning of cortical boundaries such as the inferior mandibular cortex (Fig. 25-8). Reduction in the volume of cancellous bone is more difficult to assess, although new techniques to analyze the trabecular pattern in intraoral films are being developed. Reduction in the number of trabeculae is least evident in the alveolar process, possibly because of the constant stress applied to this region of bone by the teeth. On occasion the lamina dura may appear thinner than normal. In other regions of the mandible a reduction in the number of trabeculae may be evident. Accurate assessment of bone mass loss is difficult but may be done with sophisticated techniques such as dual-energy photon absorption or quantitative computed tomography programs.

RICKETS AND OSTEOMALACIA

Rickets and osteomalacia result from inadequate serum and extracellular levels of calcium and phosphate, minerals required for the normal calcification of bone and teeth. Both abnormalities result from a defect in the normal activity of the metabolites of vitamin D, especially 1,25(OH)2D, required for resorption of calcium in the intestine. Failure of normal mineralization is seen histologically as wide uncalcified osteoid (new bone matrix) seams. The term rickets is usually applied when the disease affects the growing skeleton in infants and children. The term osteomalacia is used when this disease affects the mature skeleton in adults.

Failure of normal activity of vitamin D may occur as a result of the following:

1. Lack of vitamin D in the diet

2. Lack of absorption of vitamin D resulting from various gastrointestinal malabsorption problems

3. Lack of metabolism of the active metabolite 1,25(OH)2D, which is required for intestinal absorption of calcium

Interference may occur anywhere along the metabolic pathway for 1,25(OH)2D:

1. Lack of exposure to ultraviolet light required for conversion of provitamin D3

2. Lack of conversion of vitamin D3 to 25(OH)D in the liver because of liver disease

3. Lack of metabolism of 25(OH)D2 to 1,25(OH)2D by the kidney because of kidney diseases

4. A defect in the intestinal target cell response to 1,25(OH)2D or inadequate calcium supply

Clinical Features

Rickets.: In the first 6 months of life, tetany or convulsions are the most common clinical problems resulting from the hypocalcemia of rickets. Later in infancy the skeletal effects of the disease may be more clinically prominent. Craniotabes, a softening of the posterior of the parietal bones, may be the initial sign of the disease. The wrists and ankles typically swell. Children with rickets usually have short stature and deformity of the extremities. Development of the dentition is delayed, and the eruption rate of the teeth is retarded.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: In rickets the earliest and most prominent radiographic manifestation is a widening and fraying of the epiphyses of the long bones. The soft weight-bearing bones such as the femur and tibia undergo a characteristic bowing. Greenstick fractures (an incomplete fracture) occur in many patients with rickets.

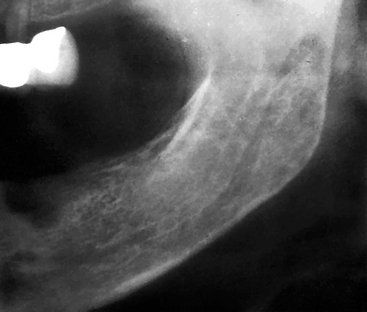

In osteomalacia the cortex of bone may be thin. Pseudofractures, which are poorly calcified ribbonlike zones extending into bone at approximate right angles to the margin of the bone, may also be present. Pseudofractures occur most commonly in the ribs, pelvis, and weight-bearing bones and rarely in the mandible.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: In rickets, jaw cortical structures such as the inferior mandibular border or the walls of the mandibular canal may thin. Changes in the jaws generally occur after changes in the ribs and long bones. Within the cancellous portion of the jaws, the trabeculae become reduced in density, number, and thickness. In severe cases, the jaws appear so radiolucent that the teeth appear to be bereft of bony support.

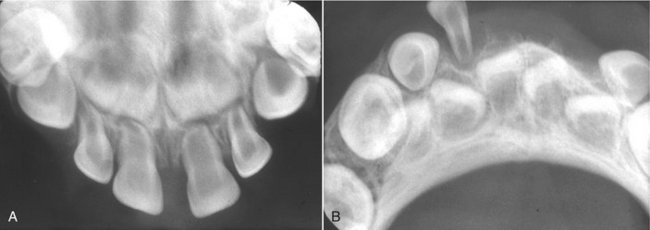

Most cases of osteomalacia produce no radiographic manifestations in the jaws. However, when radiographic manifestations are present, there may be an overall radiolucent appearance and sparse trabeculae.

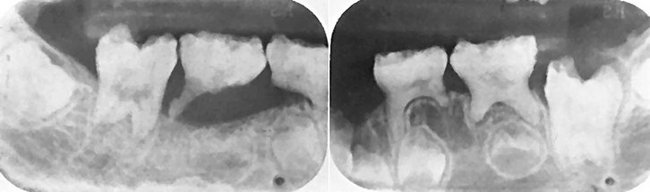

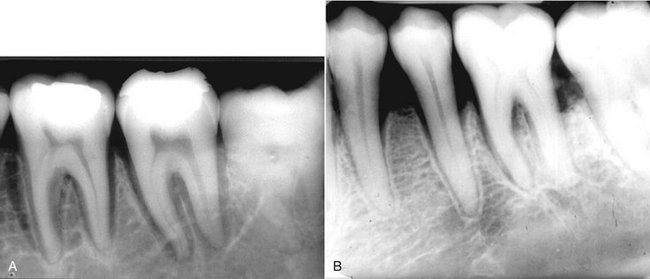

Radiographic Changes Associated with the Teeth.: Rickets in infancy or early childhood may result in hypoplasia of developing dental enamel (Fig. 25-9). If the disease occurs before the age of 3 years, such enamel hypoplasia is fairly common. Radiographs may reveal this early manifestation of rickets in unerupted and erupted teeth. Radiographs may also document retarded tooth eruption in early rickets. The lamina dura and the cortical boundary of tooth follicles may be thin or missing.

FIG. 25-9 Rickets may cause thinning (hypoplasia) or decreased mineralization (hypocalcification) of the enamel as seen in this bitewing view. (Courtesy H. G. Poyton, DDS, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Osteomalacia does not alter the teeth because they are fully developed before the onset of the disease. The lamina dura may be especially thin in individuals with long-standing or severe osteomalacia.

HYPOPHOSPHATASIA

Hypophosphatasia is a rare inherited disorder that is caused by either a reduced production or a defective function of alkaline phosphatase. This enzyme is required for normal mineralization of osteoid. Patients have a low level of serum alkaline phosphatase activity and elevated urinary excretion of phosphoethanolamine. The usual pattern of inheritance is an autosomal dominant mode of disease transmission, although an autosomal recessive pattern exists.

Clinical Features

The disease in individuals with homozygous involvement usually begins in utero, and affected patients often die within the first year. These infants demonstrate bowed limb bones and a marked deficiency of skull ossification. Individuals with heterozygous disease show the biochemical defects but a milder disease clinically. These children show poor growth, fractures, and deformities similar to those of rickets. A history may exist of fractures, delayed walking, or ricketslike deformities that heal spontaneously. About 85% of these children show premature loss of the primary teeth, particularly the incisors, and delayed eruption of the permanent dentition. This is often the first clinical sign of hypophosphatasia.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: In young children with hypophosphatasia, the long bones show irregular defects in the epiphysis, and the skull is poorly calcified. In older children with premature closure of the skull sutures, multiple lucent areas of the calvarium may exist, called gyral or convolutional markings. These markings resemble hammered copper. The skull may assume a brachycephalic shape. A generalized reduction in bone density may occur in adults.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: A generalized radiolucency of the mandible and maxilla is evident. The cortical bone and lamina dura are thin, and the alveolar bone is poorly calcified and may appear deficient.

Radiographic Changes Associated with the Teeth.: Both primary and permanent teeth have a thin enamel layer and large pulp chambers and root canals (Fig. 25-10). The teeth may also be hypoplastic and may be lost prematurely.

RENAL OSTEODYSTROPHY

Definition

In renal osteodystrophy, bone changes result from chronic renal failure. The kidney disease interferes with the hydroxylation of 25(OH)D into 1,25(OH)2D, which normally occurs in the kidney. The vitamin D metabolite 1,25(OH)2D is responsible for the active transport of calcium in the duodenum and upper jejunum. Affected patients often have hypocalcemia as a result of impaired calcium absorption and hyperphosphatemia resulting from reduction in renal phosphorus excretion. A prolonged low serum level of calcium stimulates the parathyroid glands to produce PTH. The result is a secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of renal osteodystrophy are those of chronic renal failure. In children, growth retardation and frequent bone fractures may occur. Adults may have a gradual softening and bowing of the bones.

Radiographic Features

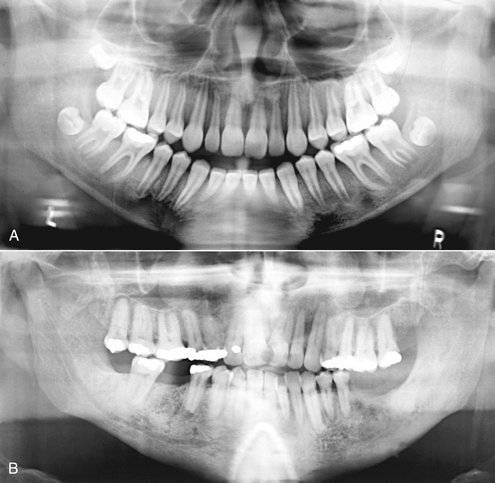

General Radiographic Features.: The radiographic features of renal osteodystrophy are quite variable. Some changes of the skeleton resemble those seen in rickets, and other changes are consistent with hyperparathyroidism, including generalized loss of bone density and thinning of bony cortices. Of interest is the occasional finding of an increase in bone density (Fig. 25-11). There may be brown tumors, similar to those seen in primary hyperthyroidism, but these are less frequent. Also, jaw enlargement has been reported in patients with renal disease who were treated with renal dialysis. The size increase is due to enlargement of the cancellous bone component that has a dense granular trabecular pattern.

FIG. 25-11 Two cases of renal osteodystrophy. A, This panoramic image reveals areas of radiolucency corresponding to loss of bone mass, loss of distinct lamina dura, and a sclerotic bone pattern around the roots of the teeth. B, This panoramic image reveals a diffuse sclerotic (radiopaque) bone pattern throughout the jaws. Note the loss of a distinct inferior cortex of the mandible resulting from an increase in the radiopacity of the internal aspect of the bone.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: In renal osteodystrophy the density of the mandible and maxilla may be less than normal and occasionally may be greater than normal. Manifestations include a decrease or an increase in the number of internal trabeculae, and the trabecular bone pattern may be granular. The cortical boundaries may be thinner or less apparent. It is important to note that these bone changes may persist after a successful renal transplant because of hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands, resulting in a continued elevation of PTH.

HYPOPHOSPHATEMIA

Definition

Hypophosphatemia represents a group of inherited conditions that produce renal tubular disorders resulting in excessive loss of phosphorus. There is a failure to reabsorb phosphorus in the distal renal tubules, resulting in a decrease in serum phosphorus (hypophosphatemia). Normal calcification of the osseous structures requires the correct amount and ratio of serum calcium and phosphorus. Multiple myeloma may induce hypophosphatemia as a result of secondary damage to the kidneys.

Clinical Features

Children with hypophosphatemia show reduced growth and ricketslike bony changes. These include bowing of the legs, enlarged epiphyses, and skull changes. Adults have bone pain, muscle weakness, and vertebral fractures.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: In children with hypophosphatemia, radiographic findings are indistinguishable from those of rickets. In adults the long bones may show persistent deformity, fractures, or pseudofractures.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: The jaws are usually osteoporotic and in extreme cases are remarkably radiolucent. Cortical boundaries may be unusually radiolucent or not apparent (Fig. 25-12).

FIG. 25-12 A, A panoramic image of hypophosphatemia. Note the radiolucent appearance of the jaws and hence the lack of bone density and the large pulp chambers. B and C, These periapical films of a different case of hypophosphatemia demonstrate apparent bone loss around the teeth, a granular bone pattern, large pulp chambers, and external root resorption.

Other possibilities include fewer visible trabeculae and a granular trabecular pattern.

Radiographic Features Associated with the Teeth.: The teeth may be poorly formed, with thin enamel caps and large pulp chambers and root canals (Fig. 25-12, B and C). In addition, periapical and periodontal abscesses occur frequently. The occurrence of periapical rarefying osteitis without an etiology may be a result of large pulp chambers and defects in the formation of dentin. This may allow for the ingress of oral microorganisms and subsequent pulp necrosis. If the disease is severe, the patient has premature loss of the teeth. The lamina dura may become sparse, and cortical boundaries around tooth crypts may be thin or entirely absent.

OSTEOPETROSIS

Definition

Osteopetrosis is a disorder of bone that results from a defect in the differentiation and function of osteoclasts. The lack of normally functioning osteoclasts results in abnormal formation of the primary skeleton and a generalized increase in bone mass. The failure of normal bone remodeling results in dense, fragile bones that are susceptible to fracture and infection. Obliteration of the marrow compromises hematopoiesis and compresses cranial nerves. This disorder is inherited as an autosomal recessive type (osteopetrosis congenita) and autosomal dominant type (osteopetrosis tarda).

Clinical Features

The more severe, recessive form of osteopetrosis is seen in infants and young children, and the more benign, dominant form appears later. The severe form is invariably fatal early in life. The patient has progressive loss of the bone marrow and its cellular products and a severe increase in bone density. The narrowing of bony canals results in hydrocephalus, blindness, deafness, vestibular nerve dysfunction, and facial nerve paralysis. The benign dominant form is milder and may be entirely asymptomatic. It may be discovered any time from childhood into adulthood. The disease may be found as an incidental finding or appear as a pathologic fracture of a bone. In some of the more chronic cases, bone pain and cranial nerve palsies caused by neural compression may be clinical problems. Osteomyelitis may complicate this disease because of the relative lack of vascularity of the dense bone. This problem is more common in the mandible, whereas osteomyelitis is usually a result of dental or periodontal disease.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: In the classic radiographic presentation of osteopetrosis, all bones show greatly increased density, which is bilaterally symmetric. The increased density throughout the skeleton is homogeneous and diffuse (Fig. 25-13). The internal aspect of the involved bone may be so dense or radiopaque that the trabecular patterns of the medullary cavity may not be visible. The internal radiopacity also reduces the contrast between the outer cortical border and the cancellous portion of the bone. The entire bone may be mildly enlarged.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: The increased radiopacity of the jaws may be so great that the radiographic image may fail to reveal any internal structure and even the roots of the teeth may not be apparent. The increased bone density and relatively poor vascularity results in a susceptibility of the mandible to osteomyelitis, usually from odontogenic inflammatory lesions (Fig. 25-14).

Radiographic Features Associated with the Teeth.: Effects on teeth may include delayed eruption, early tooth loss, missing teeth, malformed roots and crowns, and teeth that are poorly calcified and prone to caries. The normal eruption pattern of the primary and secondary dentition may be delayed as a result of bone density or ankylosis. The lamina dura and cortical borders may appear thicker than normal.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other sclerosing bone dysplasias such as sclerosteosis, infantile cortical hyperostosis, pyknodysostosis, craniometaphyseal dysplasia, diaphyseal dysplasia, melorheostosis, and osteopathia striata. Osteosclerosis from fluoride poisoning and secondary hyperparathyroidism from renal disease also may have a general sclerotic appearance.

Treatment

Treatment of osteopetrosis consists of bone marrow transplants to attempt to stimulate the formation of functional osteoclasts and systemic steroids for the hematologic component. The osteomyelitis is difficult to treat, and a combination of antibiotics and hyperbaric oxygen therapy is used. It is imperative that affected patients avoid odontogenic inflammatory disease.

Other Systemic Diseases

PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Definition

Progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) is a generalized connective tissue disease that causes excessive collagen deposition resulting in hardening (sclerosis) of the skin and other tissues. The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, heart, lungs, and kidneys usually results in more serious complications. The cause of the disease is unknown.

Clinical Features

PSS is a disease of middle age, with the greatest incidence between the ages of 30 and 50 years. It is seen rarely in adolescence or in the elderly. Women are affected about three times as often as men.

In most patients with moderate to severe PSS, the involved skin has a thickened, leathery quality. The skin is not mobile over the underlying soft tissues, and involvement of the facial region may inhibit normal mandibular opening. Patients with diffuse disease are also likely to have xerostomia; increased numbers of decayed, missing, or filled teeth; and carious lesions. Further, patients with systemic disease are more likely to have deeper periodontal pockets and higher gingivitis scores. Patients with cardiac and pulmonary problems may have varying degrees of heart failure and respiratory insufficiencies. Renal involvement usually leads to some degree of uremia, with or without hypertension.

Radiographic Features

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: A radiographic feature in some cases of PSS is an unusual pattern of mandibular erosions at regions of muscle attachment such as the angles, coronoid process, digastric region, or condyles (Fig. 25-15). This type of resorption is typically bilateral and fairly symmetric. Most of these erosive borders are smooth and sharply defined. This resorption may be progressive with the disease.

Radiographic Changes Associated with the Teeth.: The most common oral radiographic manifestation of PSS is an increase in the width of the periodontal ligament (PDL) spaces around the teeth (Fig. 25-16). Approximately two thirds of patients with PSS show this change. The PDL spaces affected by PSS usually are at least twice as thick as normal and both anterior and posterior teeth are affected, although it is more pronounced around the posterior teeth. The lamina dura remains normal. Despite the widening of the PDL spaces, the clinician finds that involved teeth are often not mobile and their gingival attachments are usually intact. Almost half the patients with PDL space thickening also have some mandibular erosive bone changes.

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of widening of the periodontal membrane space include tooth mobility, orthodontic tooth movement, intermaxillary fixation with arch bars, and invasion of the PDL by malignant neoplasms. Widening of the PDL space with malignant neoplasia differs in destruction of the lamina dura and irregular widening.

Management

The aforementioned thickening of PDL spaces does not seem to present any clinical difficulties. The progressive loss of bone in the region of the mandibular angle, however, is more serious because of potential fracture. It is reasonable to obtain initial and periodic panoramic radiographs in all patients with PSS to assess mandibular integrity.

SICKLE CELL ANEMIA

Sickle cell anemia is an autosomal recessive, chronic hemolytic blood disorder. Patients with this disorder have abnormal hemoglobin (deoxygenated hemoglobins), which under low oxygen tension results in sickling of the red blood cells. These blood cells have a reduced capacity to carry oxygen to the tissues and, because of damage to their membrane lipids and proteins, adhere to vascular endothelium and obstruct capillaries. The spleen traps and readily destroys these abnormal red blood cells. The hematopoietic system responds to the resultant anemia by increasing the production of red blood cells, which requires compensatory hyperplasia of the bone marrow.

Clinical Features

The homozygous form of sickle cell anemia occurs in approximately one in every 400 African-Americans. Although the gene is present in the heterozygous state in about 6% to 8% of African-Americans, those who manifest this form of the sickle cell trait do not show related clinical findings.

Although symptoms and signs vary considerably, most patients with the disease normally manifest mild, chronic features. Long quiet spells of hemolytic latency occur, occasionally punctuated by exacerbations known as sickle cell crises. During the crisis state, patients often have severe abdominal, muscle, and joint pain and a high temperature and may even undergo circulatory collapse. During milder periods the patient may complain of fatigability, weakness, shortness of breath, and muscle and joint pain. As in the other chronic anemias, the heart is usually enlarged and a murmur may be present. The disease occurs mostly in children and adolescents. It is compatible with a normal life span, although many patients die of complications of the disease before the age of 40 years.

Radiographic Features

The hyperplasia of the bone marrow at the expense of cancellous bone is the primary reason for the radiographic manifestations of sickle cell anemia. The extent of bone changes in sickle cell anemia relates to the degree of this hyperplasia.

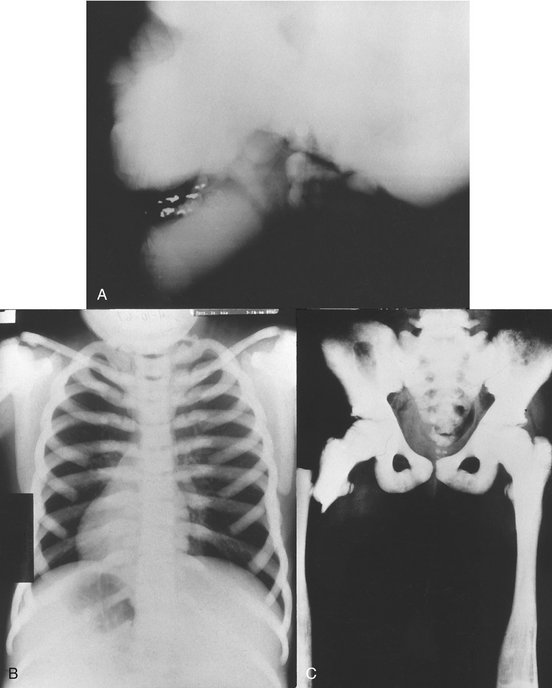

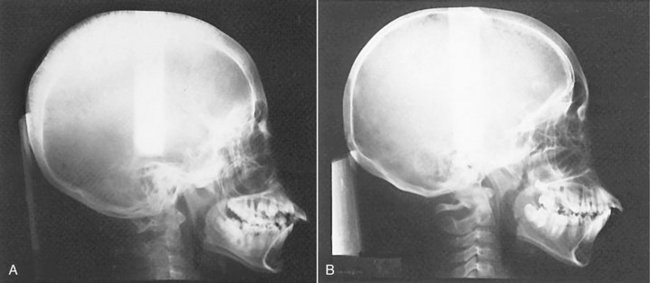

General Radiographic Features.: The thinning of individual cancellous trabeculae and cortices is most common in the vertebral bodies, long bones, skull, and jaws. The skull may have widening of the diploic space and thinning of the inner and outer tables (Fig. 25-17). In extreme cases (5%) the outer table of the skull will not be apparent and a hair-on-end appearance may occur. Small areas of infarction may be present within bones after blockage of the microvasculature; these are seen radiographically as areas of localized bone sclerosis.

FIG. 25-17 A, Radiograph of a patient with sickle cell anemia showing a thickened diploic space and thinning of the skull cortex. B, Normal skull for comparison. C, Skull showing the hair-on-end bone pattern. (B courtesy Dr. B. Sarnat, Los Angeles, Calif.; C courtesy H. G. Poyton, DDS, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Osteomyelitis may complicate sickle cell anemia if infection begins in an area of pronounced hypovascularity. There may also be retardation of generalized bone growth.

Radiographic Features of the Jaws.: The radiographic manifestations of sickle cell anemia in the jaws include general osteoporosis. This occurs because of a decrease in the volume of trabecular bone and, to a lesser extent, thinning of the cortical plates. In most cases the change is mild or moderate, with extreme radiographic manifestations being unusual. The bone pattern may be altered to one with fewer but coarser trabeculae. Radiographs of the jaws of children with sickle cell anemia have been reported to show a high frequency of severe osteoporosis. Rarely, bone marrow hyperplasia may cause enlargement and protrusion of the maxillary alveolar ridge.

THALASSEMIA

Definition

Thalassemia is a hereditary disorder that results in a defect in hemoglobin synthesis. This defect may involve either the a α- or β-globulin genes. The resultant red blood cells have reduced hemoglobin content, are thin, and have a shortened life span. The heterozygous form of the disease (thalassemia minor) is mild. The homozygous form (thalassemia major) may be severe. A less severe form, thalassemia intermedia, also occurs.

Clinical Features

In the severe form of the disease, the onset is in infancy and the survival time may be short. The face develops prominent cheekbones and a protrusive premaxilla, resulting in a “rodentlike” face. The milder form of the disease occurs in adults.

Radiographic Features

General Radiographic Features.: Similar to sickle cell anemia, the radiographic features of thalassemia generally result from hyperplasia of the ineffective bone marrow and its subsequent failure to produce normal red blood cells. However, these changes are usually more severe than with other anemias. There is a generalized radiolucency of the long bones with cortical thinning. In the skull the diploic space exhibits marked thickening, especially in the frontal region. The skull shows a generalized granular appearance (Fig. 25-18), and occasionally a hair-on-end effect may develop.

FIG. 25-18 A, A skull radiograph of a patient with thalassemia showing a granular appearance of the skull and thickening of the diploic space. B, An axial CT image of the skull of a patient with thalassemia; note the thickened diploic space and that there is hint linear orientation of the trabeculae, especially in the frontal bone. (A courtesy H. G. Poyton, DDS, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Radiographic Appearance of the Jaws.: Severe bone marrow hyperplasia prevents pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses, especially the maxillary sinus, and causes an expansion of the maxilla that results in malocclusion (Fig. 25-19, A). The jaws appear radiolucent, with thinning of the cortical borders and enlargement of the marrow spaces. The trabeculae are large and coarse (Fig. 25-19, B). The lamina dura is thin, and the roots of the teeth may be short.

FIG. 25-19 A, A panoramic film of a patient with thalassemia; note the thickened body of the mandible and the sparse trabeculae and lack of maxillary antra. B, Radiograph of a different patient with thalassemia with thick trabeculae and large bone marrow spaces. (Courtesy H. G. Poyton, DDS, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.)

Adler, C. Bone diseases: macroscopic, histological and radiological diagnosis of structural changes in the skeleton. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2000.

Paterson, CR. Metabolic disorders of bone. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1974.

Trapnell, DH, Boweman, JE. Dental manifestation of systemic disease. London: Butterworth; 1973.

Collin, HL, Niskanen, L, Uusitupa, M, et al. Oral symptoms and signs in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A focus on diabetic neuropathy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:299–305.

Lamey, PJ, Darwazeh, AM, Frier, BM. Oral disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Med. 1992;9:410–416.

Murrah, VA. Diabetes mellitus and associated oral manifestations: a review. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:271–281.

Aldred, MJ, Talacko, AA, Savarirayan, R, et al. Dental findings in a family with hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome and a novel HRPT2 gene mutation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:212–218.

Bilezikian, JP. Hyper- and hypoparathyroidism. In: Rakel R, ed. Conn’s current therapy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985.

Daniels, JM. Primary hyperparathryroidism presenting as a palatal brown tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:409–413.

Rosenberg, EH, Guralnick, W. Hyperparathyroidism: a review of 220 proved cases with special emphasis on findings in the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15(2 Suppl):84–94.

Frensilli, J, Stoner, R, Hinrichs, E. Dental changes of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism: report of three cases. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:727–731.

Glynne, A, Hunter, I, Thomson, J. Pseudohypoparathyroidism with paradoxical increase in hypocalcemic seizures due to long-term anticonvulsant therapy. Postgrad Med J. 1972;48:632.

Eastman, JR, Bixler, D. Clinical, laboratory, and genetic investigations of hypophosphatasia: support for autosomal dominant inheritance with homozygous lethality. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 1983;3:213–234.

Jedrychowski, JR, Duperon, D. Childhood hypophosphatasia with oral manifestations. J Oral Med. 1979;34:18–22.

Macfarlane, JD, Swart, JGN. Dental aspects of hypophosphatasia: a case report, family study, and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:521–526.

Conley, H, Steflik, DE, Singh, B, et al. Clinical and histologic findings of the dentition in a hypopituitary patient: report of case. ASDC J Dent Child. 1990;57:376–379.

Edler, RJ. Dental and skeletal ages in hypopituitary patients. J Dent Res. 1977;56:1145–1153.

Kosowicz, J, Rzymski, K. Abnormalities of tooth development in pituitary dwarfism. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:853–863.

Myllarniemi, S, Lenko, HL, Perheentupa, J. Dental maturity in hypopituitarism, and dental response to substitution treatment. Scand J Dent Res. 1978;86:307–312.

Lee, BD, White, SC. Age and trabecular features of alveolar bone associated with osteoporosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:92–98.

Mohammad, AR, Alder, M, McNally, MA. A pilot study of panoramic film density at selected sites in the mandible to predict osteoporosis. Int J Prosthodont. 1996;9:290–294.

Taguchi, A, Suei, Y, Ohtsuka, M, et al. Usefulness of panoramic radiography in the diagnosis of postmenopausal osteoporosis in women: width and morphology of inferior cortex of the mandible. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1996;25:263–267.

White, SC. Oral radiographic predictors of osteoporosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002;31:84–92.

Barry, CP, Ryan, CD, Stassen, LF. Osteomyelitis of the maxilla secondary to osteopetrosis: a report of 2 cases in sisters. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:144–147.

Ruprecht, A, Wagner, H, Engel, H. Osteopetrosis: report of a case and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:674–679.

Waguespack, SG, Hui, SL, Dimeglio, LA, et al. Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis: clinical severity and natural history of 94 subjects with a chloride channel 7 gene mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:771–778.

Younai, F, Eisenbud, L, Sciubba, JJ. Osteopetrosis: a case report including gross and microscopic findings in the mandible at autopsy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:214–221.

PROGRESSIVE SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Alexandridis, C, White, SC. Periodontal ligament changes in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:113–118.

Auluck, A, Pai, KM, Shetty, C, et al. Mandibular resorption in progressive systemic sclerosis: a report of three cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2005;34:384–386.

Rout, PG, Hamburger, J, Potts, AJ. Orofacial radiological manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1996;25:193–196.

Wood, RE, Lee, P. Analysis of the oral manifestations of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:172–178.

Damm, DD, Neville, BW, McKenna, S, et al. Macrognathia of renal osteodystrophy in dialysis patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:489–495.

Hata, T, Irei, I, Tanaka, K, et al. Macrognathia secondary to dialysis-related renal osteodystrophy treated successfully by parathyroidectomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:378–382.

Proctor, R, Kumar, N, Stein, A, et al. Oral and dental aspects of chronic renal failure. J Dent Res. 2005;84:199–208.

Scutellari, PN, Orzincolo, C, Bedani, PL, et al. Radiographic manifestations in teeth and jaws in chronic kidney insufficiency. Radiol Med (Torino). 1996;92:415–420.

Harris, R, Sullivan, HR. Dental sequelae in deciduous dentition in vitamin-D resistant rickets: case report. Aust Dent J. 1960;5:200–203.

Marks, SC, Lindahl, RL, Bawden, JW. Dental and cephalometric findings in vitamin D resistant rickets. J Dent Child. 1965;32:259.

Brown, DL, Sebes, JI. Sickle cell gnathopathy: radiologic assessment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:653–656.

Ejindu, VC, Hine, AL, Mashayeckhi, M, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations of sickle cell disease. Radiographics. 2007;27:1005–1021.

Lawrenz, DR. Sickle cell disease: a review and update of current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:171–178.

Sears, RS, Nazif, MM, Zullo, T. The effects of sickle-cell disease on dental and skeletal maturation. ASDC J Dent Child. 1981;48:275–277.

White, SC, Cohen, JM, Mourshed, FA. Digital analysis of trabecular pattern in jaws of patients with sickle cell anemia. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2000;29:119–124.