Introduction to Preliminary Diagnosis of Oral Lesions

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1 Define each of the terms in the vocabulary list for this chapter.

2 List and define the eight diagnostic categories that contribute to the diagnostic process.

3 Name a diagnostic category and give an example of a lesion, anomaly, or condition for which this category greatly contributes to the diagnosis.

4 Describe the clinical appearance of Fordyce granules (spots), torus palatinus, mandibular tori, and lingual varicosities and identify them in the clinical setting or on a clinical photograph.

5 Describe the radiographic appearance and historical data (including the age, sex, and race of the patient) that are relevant to periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma).

6 Define “variant of normal” and give three examples of these lesions involving the tongue.

7 List and describe the clinical characteristics and identify a clinical picture of median rhomboid glossitis, geographic tongue, ectopic geographic tongue, fissured tongue, and hairy tongue.

8 Describe the clinical and histologic differences between leukoedema and linea alba.

CLINICAL APPEARANCE OF SOFT TISSUE LESIONS

(adjective, bullous; plural, bullae) A circumscribed, elevated lesion that is more than 5 mm in diameter, usually contains serous fluid, and looks like a blister.

(adjective, lobulated) A segment or lobe that is a part of the whole; these lobes sometimes appear fused together (Figure 1-1).

An area that is usually distinguished by a color different from that of the surrounding tissue; it is flat and does not protrude above the surface of the normal tissue. A freckle is an example of a macule.

A small, circumscribed lesion usually less than 1 cm in diameter that is elevated or protrudes above the surface of normal surrounding tissue.

Attached by a stemlike or stalklike base similar to that of a mushroom (Figure 1-2).

Variously sized circumscribed elevations containing pus.

Describing the base of a lesion that is flat or broad instead of stemlike (Figure 1-3).

A small, elevated lesion less than 1 cm in diameter that contains serous fluid.

A palpable solid lesion up to 1 cm in diameter found in soft tissue; it can occur above, level with, or beneath the skin surface.

The evaluation of a lesion by feeling it with the fingers to determine the texture of the area; the descriptive terms for palpation are soft, firm, semifirm, and fluid filled; these terms also describe the consistency of a lesion.

Red, pink, salmon, white, blue-black, gray, brown, and black are the colors used most frequently to describe oral lesions; they can be used to identify specific lesions and may also be incorporated into general descriptions.

An abnormal redness of the mucosa or gingiva.

Paleness of the skin or mucosal tissues.

One hundredth of a meter; equivalent to a little less than ½ inch (0.393 of an inch) (Figure 1-4).

A ruler measuring centimeters is used to measure all specimens submitted for microscopic examination.

One thousandth of a meter (a meter is equivalent to 39.3 inches); the periodontal probe is of great assistance in documenting the size or diameter of a lesion that can be measured in millimeters (general terms such as small, medium, or large are sometimes used, but these terms are not as specific) (Figure 1-5).

Wrinkled.

A cleft or groove, normal or otherwise, showing prominent depth.

Resembling small, nipple-shaped projections or elevations found in clusters.

Terms used to describe the surface texture of a lesion.

RADIOGRAPHIC TERMS USED TO DESCRIBE LESIONS IN BONE

The process by which parts of a whole join together, or fuse, to make one.

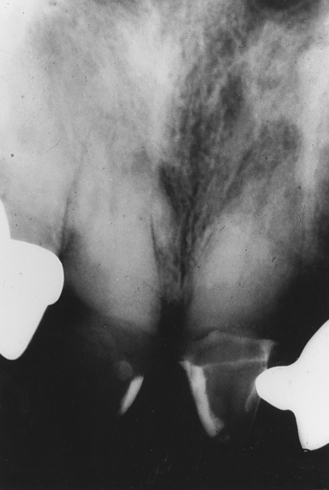

Describes a lesion with borders that are not well defined, making it impossible to detect the exact parameters of the lesion; this may make treatment more difficult and, depending on the biopsy results, more radical (Figure 1-6).

Squamous cell carcinoma of the hard palate showing diffuse borders. (Courtesy Drs. Paul Freedman and Stanley Kerpel.)

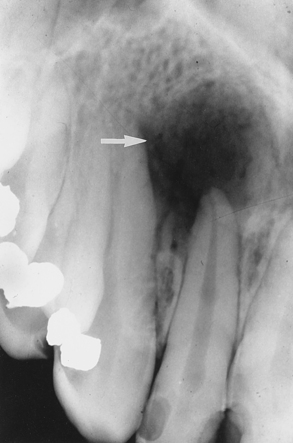

Describes a lesion that extends beyond the confines of one distinct area and is defined as many lobes or parts that are somewhat fused together, making up the entire lesion; a multilocular radiolucency is sometimes described as resembling soap bubbles; an odontogenic keratocyst often presents as a multilocular, radiolucent lesion (Figure 1-7).

Odontogenic keratocyst (arrow), illustrating a multilocular lesion. (Courtesy Dr. Victor M. Sternberg.)

Describes the black or dark areas on a radiograph; radiant energy can pass through these structures; less dense tissue such as the pulp is seen as a radiolucent structure (Figure 1-8).

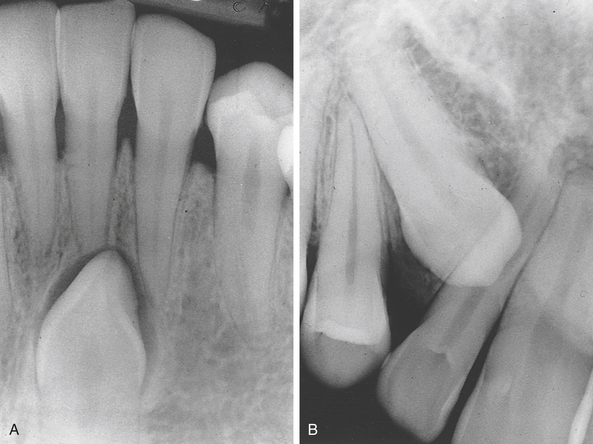

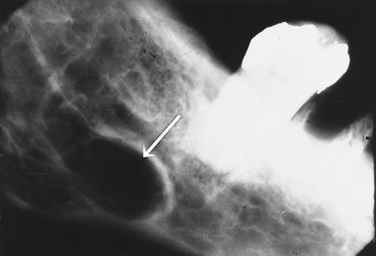

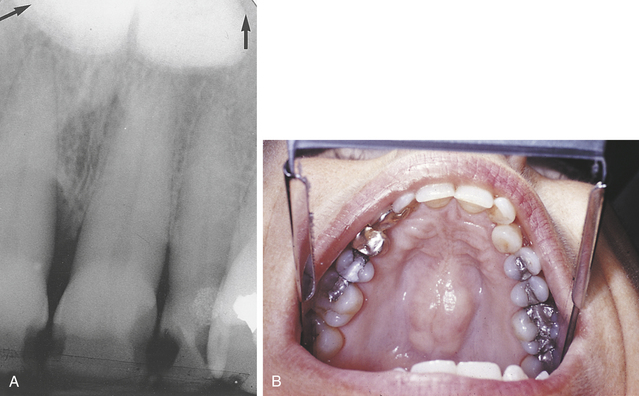

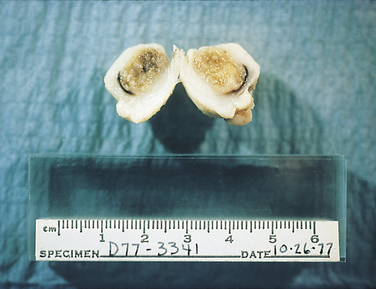

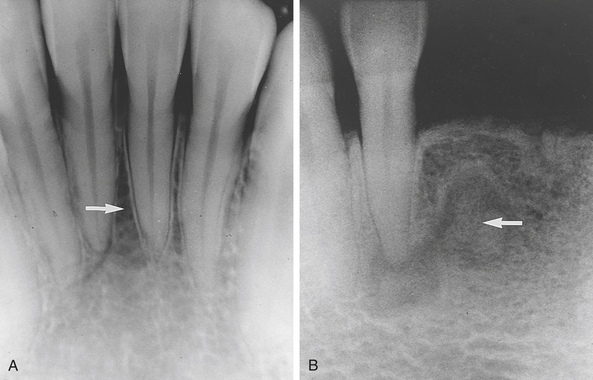

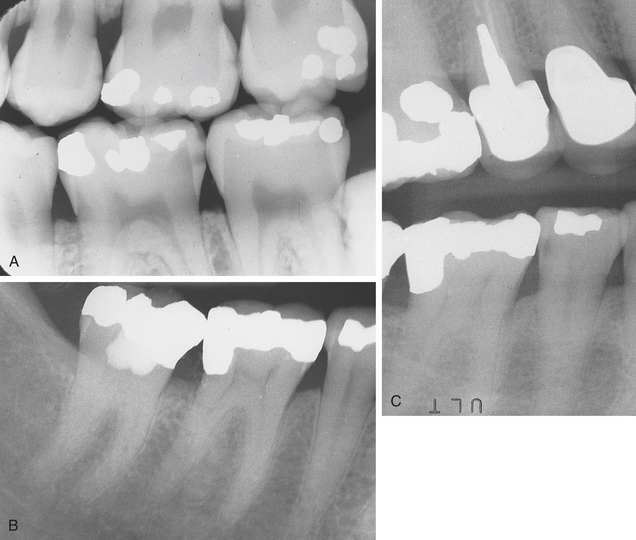

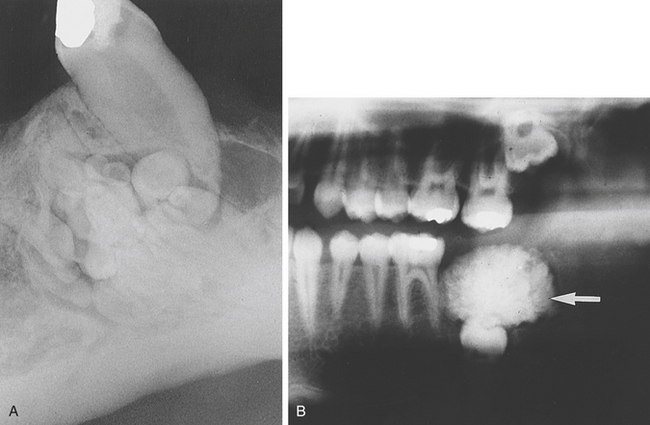

Terms used to describe a mixture of light and dark areas within a lesion, usually denoting a stage in the development of the lesion; for example, in a stage I periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma) (Figure 1-9, A), the lesion is radiolucent; in stage II it is radiolucent and radiopaque (Figure 1-9, B).

A, Stage I periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma). B, Stage II periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma).

Describes the light or white area on a radiograph that results from the inability of radiant energy to pass through the structure; the denser the structure, the lighter or whiter it appears on the radiograph; this is illustrated in Figure 1-10.

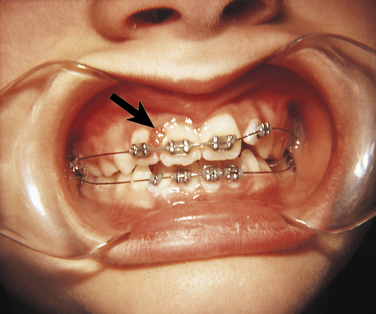

Observed radiographically when the apex of the tooth appears shortened or blunted and irregularly shaped; occurs as a response to stimuli, which can include a cyst, tumor, or trauma; Figure 1-11 illustrates resorption of the roots as a result of a rapid orthodontic procedure (see Figure 1-27); external resorption arises from tissues outside the tooth such as the periodontal ligament, whereas internal resorption is triggered by pulpal tissue reaction from within the tooth; in the latter the pulpal area can be seen as a diffuse radiolucency beyond the confines of the normal pulp area.

Resorption of the roots on maxillary anteriors as a result of rapid orthodontic movement.

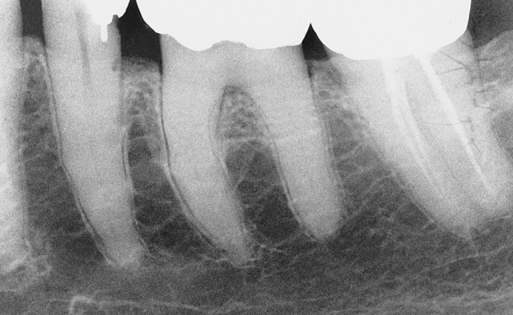

A radiolucent lesion that extends between the roots, as seen in a traumatic bone cyst; this lesion appears to extend up the periodontal ligament (Figure 1-12).

Having one compartment or unit that is well defined or outlined, as in a simple radicular cyst (Figure 1-13).

Radicular cyst at the apex of the maxillary lateral incisor, illustrating a unilocular lesion.

Term used to describe a lesion with borders that are specifically defined and in which one can clearly see the exact margins and extent (Figure 1-14).

To understand the material in this text, it is imperative that the reader approach it in a systematic manner. Significant time is spent in the dental hygiene curriculum identifying and describing normal structures. Before one can identify the abnormal condition, it is necessary to have a solid understanding of the basic and dental sciences such as human anatomy and physiology, histology, and dental anatomy. Once one has a solid understanding of normal structures and those that are variants of normal, findings that deviate from normal and pathologic conditions are recognized more easily. The preliminary evaluation and description of these lesions are within the scope of dental hygiene practice and are truly among the most challenging experiences in clinical practice.

In the first part of this chapter the definitions of commonly used terms that describe the clinical and radiographic features of a lesion, including terms used for normal, variants of normal, and pathologic conditions discussed throughout this text, are presented. The reader is encouraged to use these terms in the clinical setting so that they become part of an everyday professional vocabulary, thereby facilitating communication between the hygienist and other dental practitioners in the clinical setting.

The second part of this chapter focuses on the eight diagnostic categories that provide a systematic approach to the preliminary evaluation of oral lesions. Each area is described, and the strength of that area in the diagnostic process is illustrated using specific examples of lesions.

The final part of the chapter includes conditions that are considered variants of normal and those that are benign conditions of unknown cause. Most are diagnosed from their distinct clinical appearance and history.

MAKING A DIAGNOSIS

How is a diagnosis made? What are the essential components? The answers to these questions begin with data collection. The process of diagnosis requires gathering information that is relevant to the patient and the lesion being evaluated; this information comes from various sources.

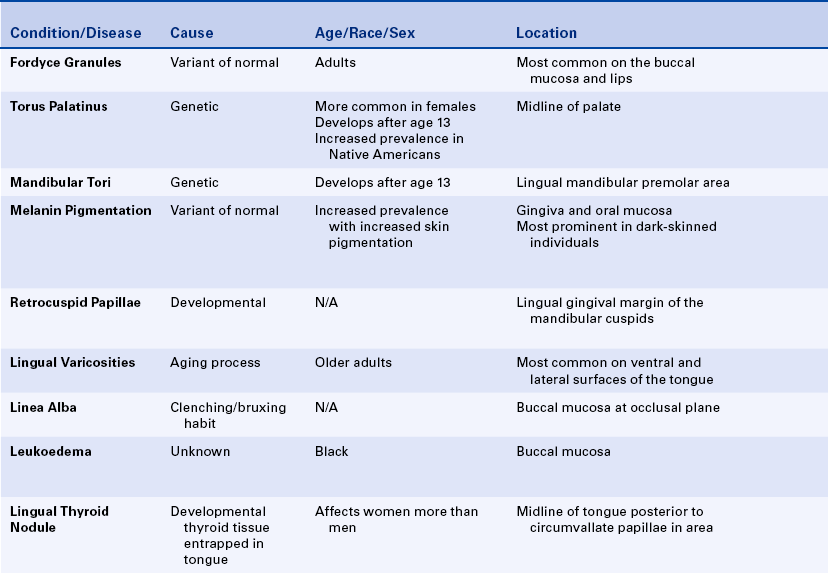

Certain distinct diagnostic categories should be thought of as pieces in a puzzle, with each piece playing a significant role in the final diagnosis. The eight categories that contribute segments of information leading to the definitive or final diagnosis are (1) clinical, (2) radiographic, (3) historical, (4) laboratory, (5) microscopic, (6) surgical, (7) therapeutic, and (8) differential findings. It is important to note that usually one area alone does not provide sufficient information to make a diagnosis; the strength of the diagnosis is often derived from one or two areas. As the reader becomes more aware of the diseases and conditions discussed in this text, it will be most helpful to use the diagnostic categories as a guide to the evaluation of a lesion.

Clinical Diagnosis

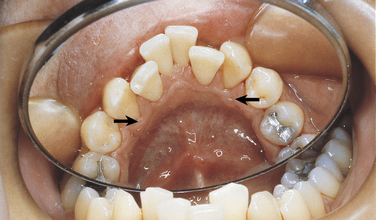

Clinical diagnosis suggests that the strength of the diagnosis comes from the clinical appearance of the lesion. By observing the area in a well-illuminated clinical setting and palpating it if necessary, the clinician can establish a diagnosis for some lesions on the basis of color, shape, location, and history of the lesion. When a diagnosis can be made on the basis of these unique clinical features, biopsy or surgical intervention is not necessary. Examples of lesions that can be clinically diagnosed are Fordyce granules (Figure 1-15), torus palatinus (Figure 1-16), mandibular tori (Figure 1-17), melanin pigmentation (Figure 1-18), retrocuspid papillae (Figure 1-19), and lingual varicosities. These lesions are described later in this chapter.

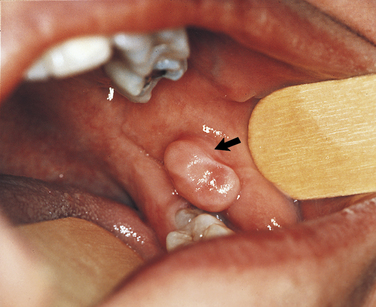

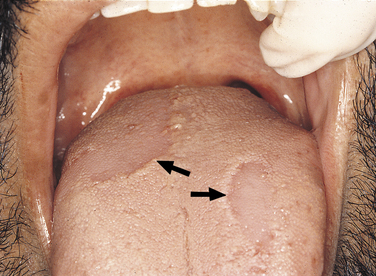

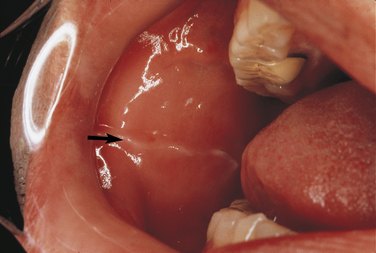

FIGURE 1-19 Arrows point to the retrocuspid papillae on the gingival margin of the lingual aspect of the mandibular cuspids.

Other benign conditions of unknown cause that are recognized by their distinct clinical appearance include fissured tongue (Figure 1-20), median rhomboid glossitis (Figure 1-21), geographic tongue (Figure 1-22), and hairy tongue (Figure 1-23). These conditions are also discussed later in this chapter.

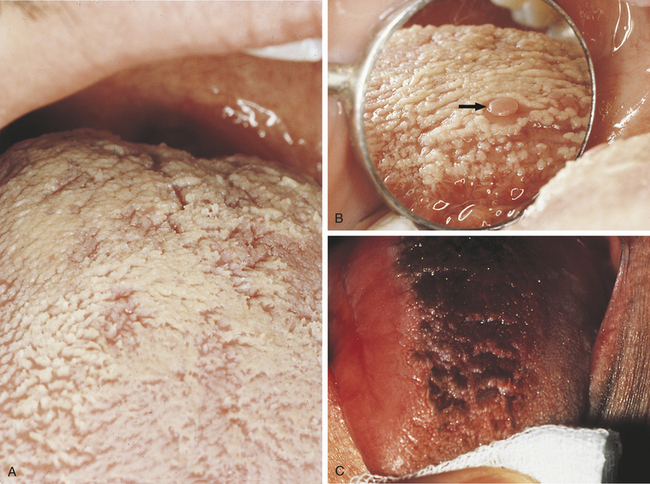

FIGURE 1-23 A, White hairy tongue. B, White hairy tongue showing a circumvallate papilla (arrow). C, Black hairy tongue.

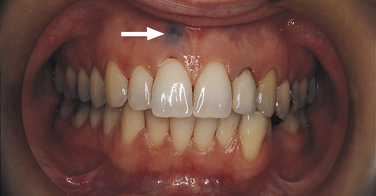

Sometimes the diagnostic process requires historical information in addition to the clinical findings. For example, an amalgam tattoo (focal argyrosis) can be observed as a blue-to-gray patch on the gingiva or mucosa where an amalgam restoration is or has been located (Figure 1-24). Although this condition is usually easily observed and a clinical diagnosis made, any history involving the area can still be very helpful in confirming the clinical impression. The patient in Figure 1-24 had root canal therapy and a retrograde amalgam on a deciduous tooth. The amalgam tattoo is observed in the apical area of the permanent central incisor; no evidence of an amalgam restoration exists in the entire anterior area. The history helped confirm the clinical diagnosis.

FIGURE 1-24 Arrow points to an amalgam tattoo at the apical area of the patient’s maxillary right central incisor. This patient had a root canal procedure on a deciduous tooth. No other amalgam restoration is in the area; therefore it was helpful to know the patient’s past dental history to confirm this diagnosis.

Radiographic Diagnosis

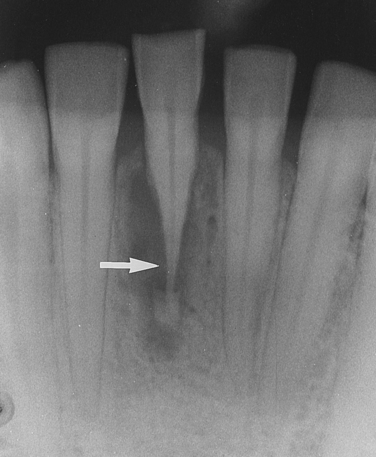

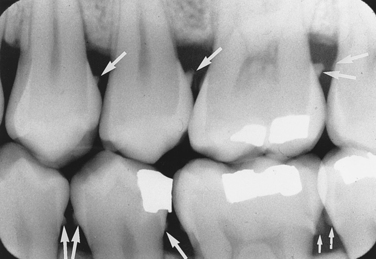

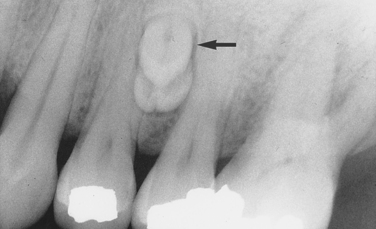

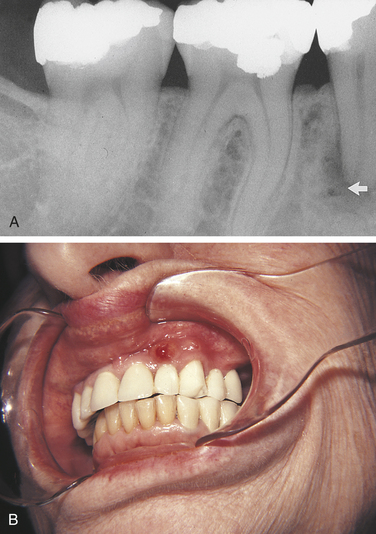

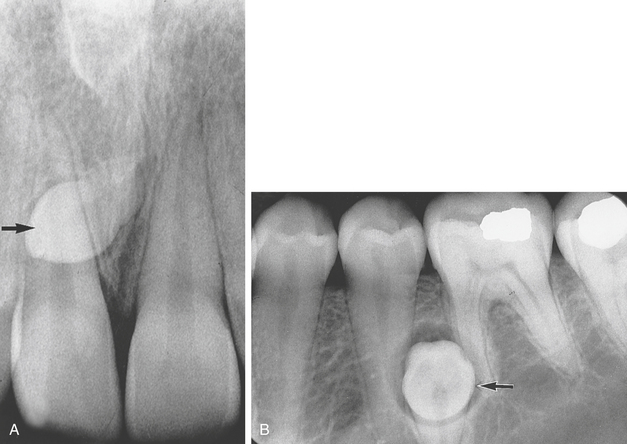

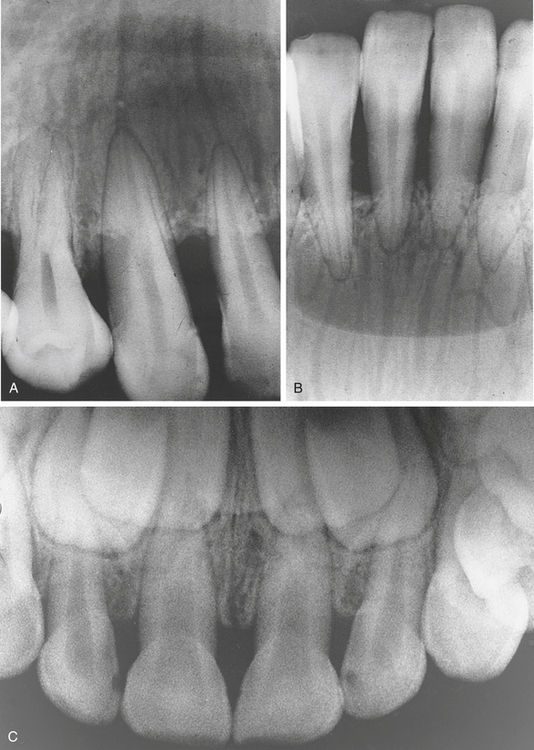

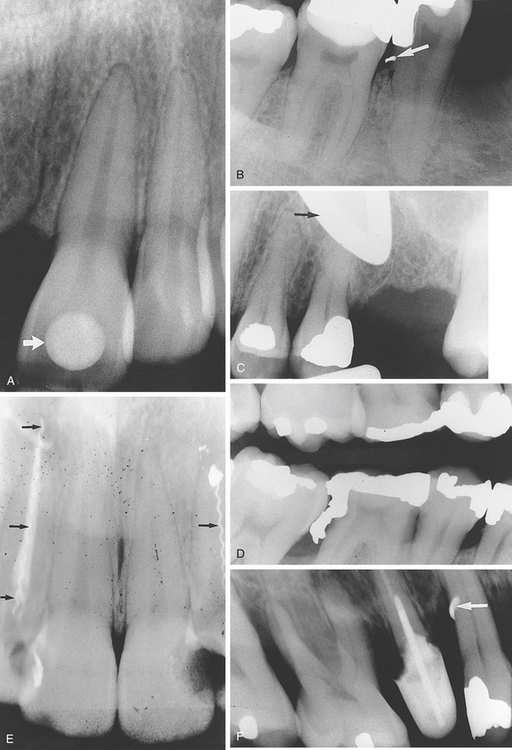

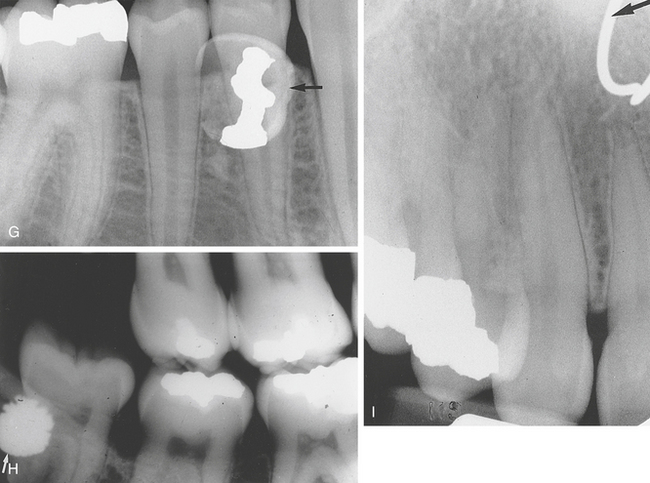

In a radiographic diagnosis the radiograph provides sufficient information to establish the diagnosis. Although additional clinical and historical information may contribute, the diagnosis is obtained from the radiograph. Conditions for which the radiograph provides the most significant information include periapical pathosis (Figure 1-25), internal resorption (Figure 1-26), external resorption (Figure 1-27), heavy interproximal calculus (Figure 1-28), dental caries (Figure 1-29), compound odontoma (Figure 1-30), complex odontoma (Figure 1-31), supernumerary teeth (Figure 1-32), impacted or unerupted teeth (Figure 1-33), and calcified pulp (Figure 1-34). Normal anatomic landmarks are also easily observed radiographically. In some cases the radiograph may show very distinct and well-defined structures such as the nutrient canals seen in Figure 1-35, A and B and the mixed dentition seen in Figure 1-35, C. Unusual radiographic findings are illustrated in Figure 1-36.

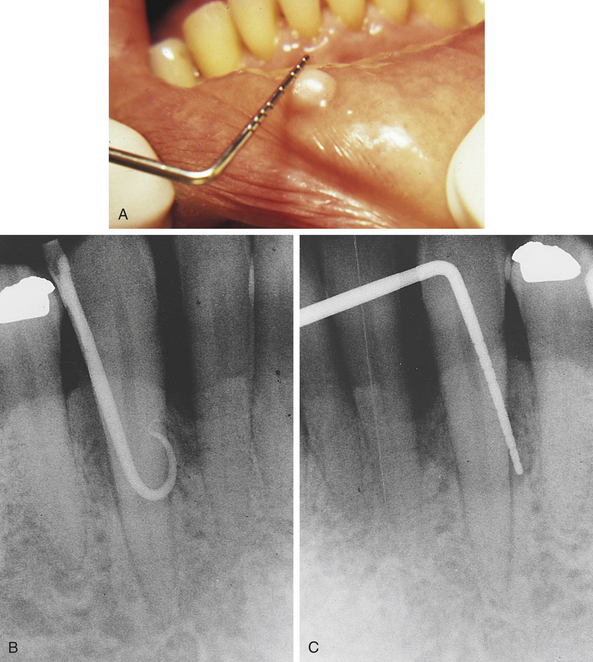

FIGURE 1-25 A, Periapical pathosis (PAP); a radiolucency is seen at the apex of the mandibular second premolar. B, In another patient a fistula is seen on the maxillary lateral incisor. A fistula is usually an indication of PAP. When a fistula is observed clinically, a radiograph is necessary for diagnostic and treatment purposes.

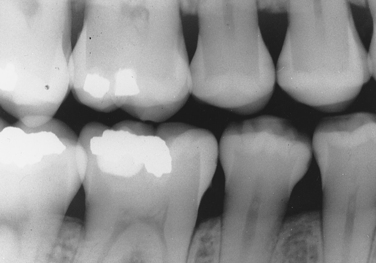

FIGURE 1-29 A, Dental caries. The reader should observe the interproximal radiolucencies. Clinical examination is necessary to confirm the involvement of some of the areas. B, Periapical radiograph taken September 1989. A subtle carious area can be seen on the distal aspect of the mandibular second premolar. C, The patient in B was seen in June 1990. During the scaling procedure a defect on the distal aspect of the mandibular second premolar was detected. This vertical bitewing radiograph was taken. The reader should note the definite radiolucent, carious area on the distal aspect of the mandibular second premolar. This example emphasizes the need for careful clinical and radiographic evaluation. (B and C courtesy Dr. Victor M. Sternberg.)

FIGURE 1-31 A, Complex odontoma rather easily diagnosed from the radiograph alone. B, Complex odontoma not diagnosed from the radiograph alone. (B courtesy Drs. Paul Freedman and Stanley Kerpel.)

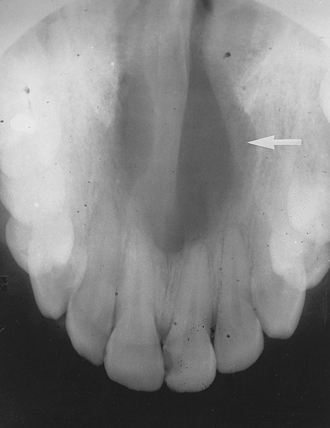

FIGURE 1-32 A, Mesiodens. A supernumerary tooth is located between the maxillary central incisors. B, A radiograph showing a supernumerary mandibular premolar (arrow) surrounded by a radiolucent area diagnosed as a dentigerous cyst. Clinically this area was thought to be a mandibular torus (until the radiograph was taken).

FIGURE 1-35 A, Nutrient canals in the anterior maxillary arch. B, Nutrient canals in the mandibular anterior area. C, The mixed dentition of a 5-year-old child is observed in this radiograph.

FIGURE 1-36 A, Arrow points to a 7-carat cubic zirconia (a round stone) that was glued to this patient’s maxillary left central incisor. B, The radiopaque area on the distal aspect of the mandibular second premolar (arrow) is an amalgam fragment. There was a subtle clinical amalgam tattoo in the interproximal papilla that was not detected or charted on initial examination, which included a full-mouth series of radiographs and incomplete scaling. When the radiographs were viewed after the patient was dismissed, the radiopaque area was thought to be the tip of a broken instrument. Further evaluation of the instruments used at that appointment ruled out the possibility of a broken instrument. When the patient returned for an additional appointment 2 weeks later, another radiograph, using the same long cone and precision Rinn instruments, was taken of the area. The radiopaque fragment remained in the exact same place. Clinically a very close look at the interproximal papilla in the area then revealed a subtle bluish-black area. The dentist surgically slit the papilla on the buccal aspect and revealed the amalgam particle. C, This patient wore wide-framed eyeglasses during the radiographic procedure. The arrow points to a U-shaped radiopacity from the eyeglass frame. D, This radiograph reveals an obvious radiopaque overhang from the amalgam restoration on the distal aspect of the mandibular first molar. E, Instruments from a root canal procedure were broken in these two maxillary lateral incisors (arrows). F, The broken tip of a curet (arrow) is observed as a radiopaque area on the distal aspect of the maxillary first premolar. G, Arrow points to a retained deciduous tooth with an amalgam restoration. H, Arrow points to a radiopaque area that identifies a retained shotgun pellet on the distal aspect of the mandibular third molar. I, Arrow points to a radiopaque circular area that is a nose ring. J, Periapical radiograph showing a radiopaque area at the apex of the mesial root of the mandibular second molar. This object was a retained piece of shrapnel. K, Panoramic radiograph of the same patient showing the same object. This radiograph gives a more accurate view of the location of the object. It was found to be in the soft tissue in the area and not within bone.

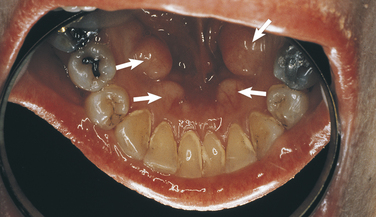

Historical Diagnosis

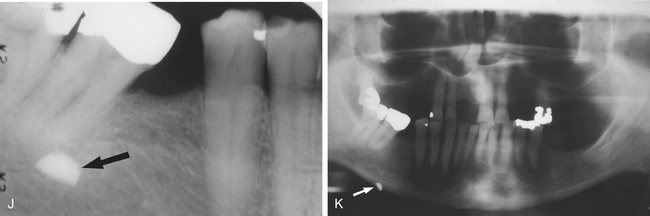

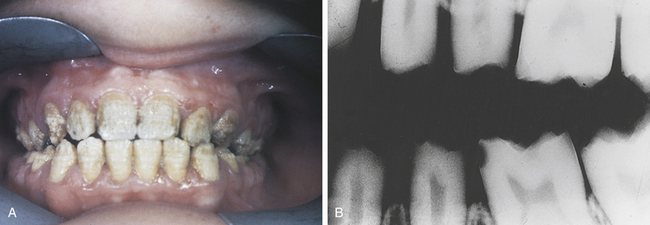

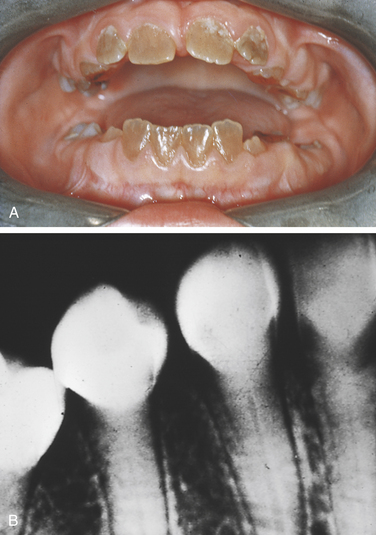

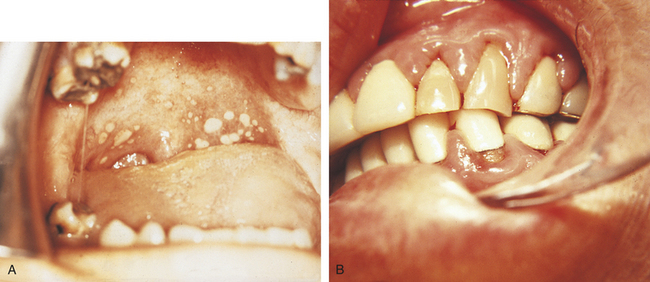

Historical data constitute an important component in every diagnosis; occasionally when historical data are combined with observation of the clinical appearance of the lesion, the historical information constitutes the most important contribution to the diagnostic process. Personal history, family history, past and present medical and dental histories, history of drug ingestion, and history of the presenting disease or lesion can provide information necessary for the final diagnosis. Thorough medical and dental histories must be a part of every patient’s permanent record. The clinician should review these documents carefully and update them with the patient at each visit. Pathologic conditions in which the family history contributes a significant role in the diagnosis include amelogenesis imperfecta (Figure 1-37), dentinogenesis imperfecta (Figure 1-38), and many other genetic disorders. In addition, clinical findings and radiographs also provide significant assistance to the diagnostic process of these conditions.

FIGURE 1-37 A, One of the clinical appearances of amelogenesis imperfecta. B, The radiographic aspect of amelogenesis imperfecta. (Courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

FIGURE 1-38 A, Clinical appearance of dentinogenesis imperfecta. B, Radiographic appearance of dentinogenesis imperfecta. (Courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

A patient’s medical or dental status, including drug history, can also contribute significant information to a diagnosis. For example, a history of ulcerative colitis may contribute to the diagnosis of oral ulcers (Figure 1-39, A), which could be related to this medical condition. Another example of the value of this type of information is the patient in Figure 1-39, B, who experienced gingival enlargement; drug history revealed that the patient was taking a calcium channel blocker.

FIGURE 1-39 A, Oral ulcers on the soft palate associated with ulcerative colitis. B, Gingival enlargement seen in a patient taking nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker. (A courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

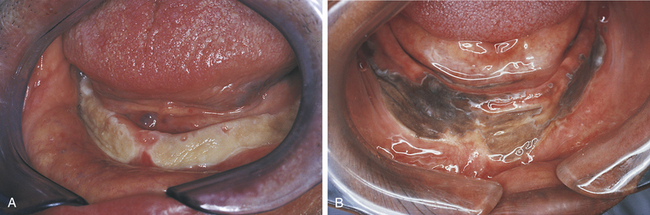

A history of a skin graft from the hip to the ridge and mucobuccal fold area in the anterior mandible in a patient can provide significant information relevant to the diagnosis of a white- or brown-pigmented area on the mandibular anterior ridge and vestibule (Figure 1-40).

FIGURE 1-40 Skin grafts performed to enhance the mandibular ridge in a white (A) and a black patient (B). Without the patients’ past medical and dental histories, it would be difficult to diagnose this anomaly of melanosis accurately.

Periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (cementoma) is another lesion in which the patient’s personal history contributes significantly. It is found most frequently in black women in the third decade of life. Other characteristics of the lesion reveal that it is asymptomatic and that the teeth involved are vital (see Figure 1-19).

Laboratory Diagnosis

Clinical laboratory tests, including blood chemistries and urinalysis, can provide information that contributes to a diagnosis. An elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level is significant in the diagnosis of Paget’s disease. This feature, in addition to a distinctive radiographic appearance that includes a “cotton-wool effect” (Figure 1-41) and hypercementosis, provides conclusive information for a definitive diagnosis. Laboratory cultures are also helpful in determining the diagnosis of oral infections.

Microscopic Diagnosis

Microscopic examination is of particular importance in the diagnostic process and therefore, although it is a form of laboratory diagnosis, it is discussed separately from laboratory diagnosis. The microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen taken from the lesion in question contributes significant information. This procedure is often the main component of the definitive diagnosis. However, the skill of the practitioner performing the biopsy is of equal importance. It is most important that an adequate tissue sample be removed for microscopic evaluation. If other diagnostic information such as clinical features or history of the lesion indicates the strong possibility of malignancy and the biopsy report does not concur, a second biopsy should be performed.

A procedure called the brush test can be used to obtain information from oral mucosal epithelium. This test was formerly referred to as a brush biopsy. This technique uses a circular brush to obtain cells from the full thickness of the epithelium, including cells from the keratin layer through the basal layer. Microscopic examination of the individual cells is used to assess whether normal, abnormal, or dysplastic cells are present. The results of this test may help determine if a scalpel biopsy is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis. Scalpel biopsy is considered the gold standard procedure used to provide the microscopic analysis that will establish the definitive diagnosis of a lesion.

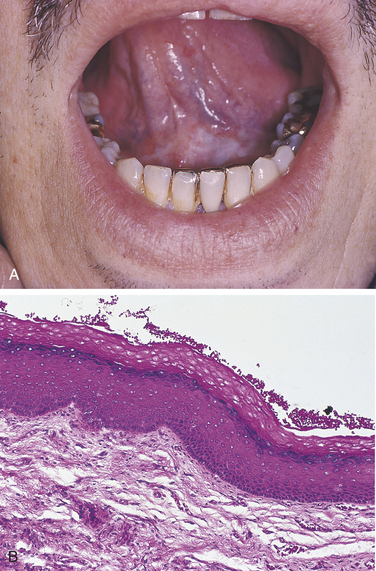

A white lesion (Figure 1-42, A) cannot be diagnosed based on its clinical appearance alone. The microscopic appearance of this type of white lesion can vary from a thickening of the epithelium or surface keratin layer to epithelial dysplasia, which can be premalignant (Figure 1-42, B).

Surgical Diagnosis

The strength of a surgical diagnosis comes from surgical intervention. Diagnosis is made using the information gained during the surgical procedure for the traumatic bone cyst (Figure 1-43). A traumatic or simple bone cyst will appear as a radiolucency that scallops around the roots. Surgical intervention provides conclusive evidence when the lesion is opened and an empty void within the bone is found. The void usually fills with bone and heals after the surgical procedure. Lingual mandibular bone concavity, also referred to as a static bone cyst or Stafne bone cyst (Figure 1-44), is a developmental anomaly that is often bilateral. The radiolucent area is oval or eliptical in shape and is found anterior to the angle of the ramus and inferior to the mandibular canal. A CT scan would further confirm the diagnosis showing the invagination of the lingual aspect of the mandible. However, if the radiolucency is not in the classic location, surgical examination and biopsy would be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. There is no treatment necessary for lingual mandibular bone concavity.

Therapeutic Diagnosis

Nutritional deficiencies are common conditions to be diagnosed by therapeutic means. Although angular cheilitis (Figure 1-45) may be associated with a deficiency of the B-complex vitamins, it is most commonly a fungal condition and responds to topical application of an antifungal cream or ointment such as nystatin. A thorough patient history should be obtained to rule out a contributory nutritional deficiency.

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) has distinct clinical features (Figure 1-46) and constitutional signs. It responds to hydrogen peroxide rinses because the anaerobic bacteria that cause NUG cannot survive in an oxygenated environment. Prescribing hydrogen peroxide rinses and observing the results without culturing the bacteria applies the principle of therapeutic diagnosis because it is based solely on clinical and historical information with confirmation by the response of the condition to therapy. Antibiotic therapy can also be used in the treatment of NUG.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is that point in the diagnostic process when the practitioner decides which test or procedure is required to rule out the conditions originally suspected and establish the definitive or final diagnosis. All the previously discussed components are applied to the differential diagnosis. The final diagnosis emerges from a thorough evaluation of the suspected lesions (Box 1-1).

To arrive at a diagnosis, the data collection included the patient’s medical and dental health histories, the history of the lesion in question, a clinical description and evaluation, and biopsy and microscopy reports. Box 1-1 illustrates the fact that arriving at a diagnosis involves a process. As stated previously, the diagnostic process can be thought of as a puzzle because the information from each diagnostic category becomes part of it. In the case presented in Box 1-1 the microscopic examination contributed most significantly to the definitive or final diagnosis. The differential diagnosis included three possible diagnoses; the biopsy and microscopic examinations provided conclusive information in the diagnostic process.

The hygienist can be effective in the preliminary evaluation of the lesion by calling it to the attention of the dentist and then gathering and preparing all the data for the clinician who will perform the biopsy. In addition, it is both challenging and stimulating to discuss diagnostic impressions with other professionals on the basis of the data available at the time.

FORDYCE GRANULES

Clusters of ectopic sebaceous glands are called Fordyce granules. They are most commonly observed on the lips and buccal mucosa. Clinically they appear as tiny yellow lobules in clusters and are usually distributed over the buccal mucosa or vermilion border of the involved lips. The surrounding tissue is normal. Because more than 80% of adults over 20 years of age have Fordyce granules, they are considered a variant of normal. Microscopically, Fordyce granules appear as normal sebaceous glands. They are asymptomatic and require no treatment (Figure 1-48).

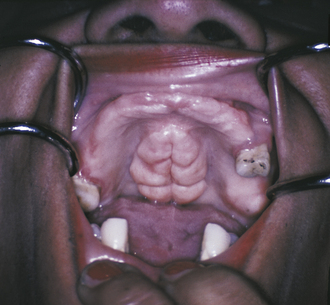

TORUS PALATINUS

Torus palatinus or palatal torus is an exophytic growth of normal compact bone. Palatal tori are inherited and occur more frequently in women. They are asymptomatic, develop gradually, and are observed clinically in the midline of the hard palate. Palatal tori may take on various shapes and sizes, may be lobulated, and are covered by normal soft tissue. It is not unusual for the palatal torus to be traumatized, which can cause discomfort and possible ulceration on the surface of the torus. When the lesion is large, it may be seen as a radiopaque mass on the radiograph. No treatment is indicated unless the torus interferes with speech, swallowing, or a prosthetic appliance (Figure 1-49).

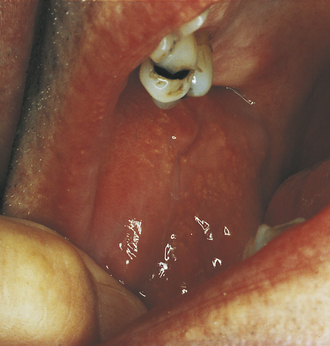

MANDIBULAR TORI

Outgrowths of normal dense bone found on the lingual aspect of the mandible in the area of the premolars above the mylohyoid ridge are mandibular tori. They are usually bilateral, often lobulated or nodular, can appear fused together, and have no predilection for either sex. Mandibular tori usually do not require treatment unless the patient needs a prosthodontic appliance (denture) and the tori interfere with proper fabrication and placement (Figure 1-50).

MELANIN PIGMENTATION

Melanin is the pigment that gives color to the skin, eyes, hair, mucosa, and gingiva. Melanin pigmentation of the oral mucosa or gingiva is most commonly observed in dark-skinned individuals (Figure 1-51; see Figure 1-18).

RETROCUSPID PAPILLA

A retrocuspid papilla is a sessile nodule on the gingival margin of the lingual aspect of the mandibular cuspids (see Figure 1-19).

LINGUAL VARICOSITIES

Prominent lingual veins, called lingual varicosities, are usually observed on the ventral and lateral surfaces of the tongue. Clinically, red-to-purple enlarged vessels or clusters are seen. They are not associated with other systemic diseases; however, a relationship between varicosities in the legs and prominent lingual veins has been reported. Lingual varices are most commonly observed in individuals older than 60 years of age and therefore are thought to be related to the aging process (Figure 1-52).

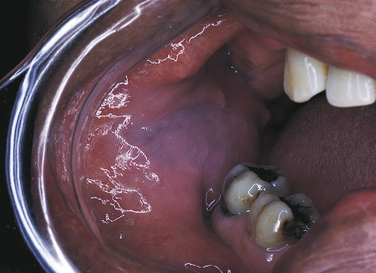

LINEA ALBA

Linea alba is a “white line” that extends anteroposteriorly on the buccal mucosa along the occlusal plane. It may be bilateral and can be more prominent in patients who have a clenching or bruxing habit (Figure 1-53).

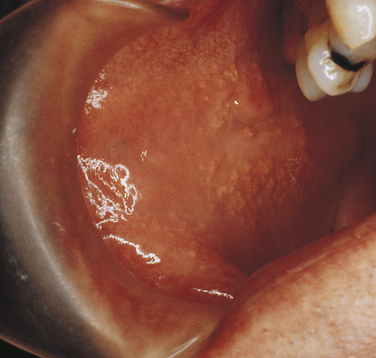

LEUKOEDEMA

A generalized opalescence is imparted to the buccal mucosa by leukoedema. It is most commonly observed in black adults (up to 85%), suggesting an ethnic predisposition. Leukoedema can also be seen in whites. Clinically a gray-white film is diffused throughout the buccal mucosa, giving the mucosa an opaque quality. If the mucosa is stretched, the opalescence becomes less prominent. The condition becomes more pronounced in smokers. The opalescence is an integral part of the buccal tissue and cannot be removed. Histologically significant intracellular edema in the spinous cells and acanthosis of the epithelium is seen. It is a benign anomaly that requires no treatment (Figure 1-54).

LINGUAL THYROID NODULE

The thyroid gland begins to develop during the first month of fetal life and is located initially in the area of the foramen cecum on the posterior tongue. In normal development the thyroid gland descends to its normal location in the neck. When thyroid tissue either does not descend or remnants become entrapped in the tissue that makes up the tongue, a developmental anomaly called a lingual thyroid nodule results. Research has indicated a high predilection in females, and studies have linked the emergence of the lingual thyroid nodule with hormonal changes because it appears to be associated with puberty, pregnancy, and menopause. Clinically a lingual thyroid nodule is observed as a mass in the midline of the dorsal surface of the tongue posterior to the circumvallate papillae in the area of the foramen cecum. The lesion usually has a sessile base and is 2 to 3 cm in width. On histologic examination normal thyroid tissue is found. Treatment requires careful evaluation of the patient to determine whether the thyroid gland is present in its normal location. Surgical intervention is not always required.

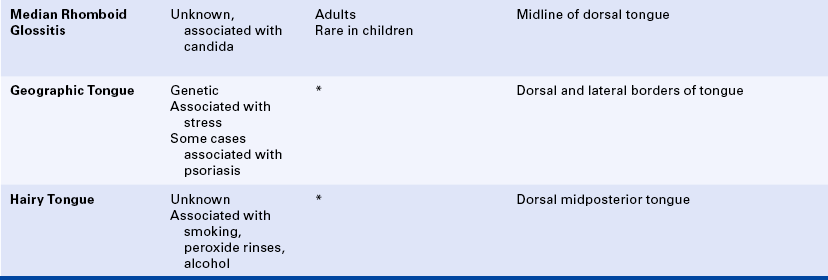

MEDIAN RHOMBOID GLOSSITIS

The cause of median rhomboid glossitis is not clear. Research has suggested that it may be associated with a chronic fungal infection by Candida albicans. Clinically median rhomboid glossitis appears as a flat or slightly raised oval or rectangular erythematous area in the midline of the dorsal surface of the tongue, beginning at the junction of the anterior and middle thirds and extending posterior to the circumvallate papillae. It is devoid of filiform papillae; therefore its texture is smooth. If the remaining surface of the tongue is coated, the area appears more prominent. No specific treatment exists; however, sometimes an antifungal agent is applied, and the lesion resolves, but this is not always the case. Occasionally the condition resolves with no specific treatment at all (Figure 1-55).

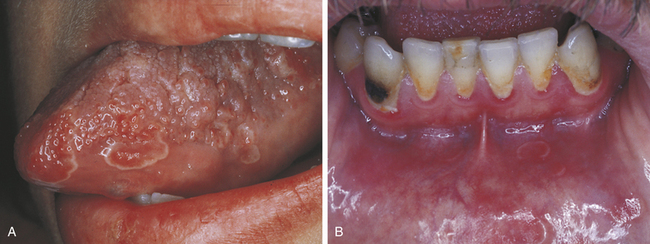

GEOGRAPHIC TONGUE

The cause of geographic tongue (erythema migrans, benign migratory glossitis) is not clear. The familial occurrence of geographic tongue suggests that genetic factors play a role. Some investigators suggest that it is exacerbated by stress, and studies exist that associate the histologic findings with those found in psoriasis. The clinical appearance involves the dorsal and lateral borders of the tongue. Diffuse areas devoid of filiform papillae can be observed. These areas appear as erythematous patches that are surrounded by a white or yellow perimeter. The fungiform papillae appear distinct within the erythematous patch. The condition does not remain static; remission and changes in the depapillated areas appear to occur. Occasionally a patient complains of a burning discomfort associated with geographic tongue. Usually no treatment is indicated (Figure 1-56, A).

FIGURE 1-56 A, Geographic tongue. B, Ectopic geographic tongue observed in the mandibular anterior mucosa.

Ectopic geographic tongue is the term used to describe the condition when it is found on mucosal surfaces other than the tongue. In Figure 1-56, B it is seen in the mandibular anterior mucobuccal fold.

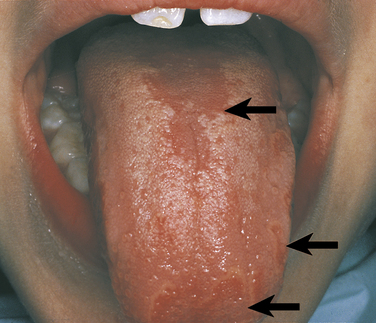

FISSURED TONGUE

The cause of fissured tongue is unknown. It is seen in about 5% of the population. Familial patterns of occurrence suggest that genetic factors are probably involved. Clinically the dorsal surface of the tongue appears to have deep fissures or grooves that may become irritated if food debris collects in them. No treatment is indicated for the condition. However, a patient with a fissured tongue may be advised to brush the tongue gently with a soft toothbrush to keep the fissures clean of debris and irritants (Figure 1-57; see Figure 1-20).

HAIRY TONGUE

Hairy tongue is a condition in which the patient has an increased accumulation of keratin on the filiform papillae that results in a white, “hairy” appearance. This may be the result of either an increase in keratin production or a decrease in normal desquamation. Unless otherwise pigmented, the elongated filiform papillae are white (Figure 1-58). In the condition known as black hairy tongue, the papillae are a brown-to-black color because of chromogenic bacteria (Figure 1-59). Tobacco and certain foods may also discolor the papillae. Although the cause is unknown, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, or chemical rinses have been suggested to stimulate the elongation of the filiform papillae that results in the appearance of hairy tongue.

Treatment involves directing the patient to brush the tongue gently with a toothbrush (wet with water only) to remove debris. The condition usually clears completely but may recur.

Darby, M.L. Mosby’s comprehensive review of dental hygiene, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby, 2006.

Neville, B.W., et al. Color atlas of clinical oral pathology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1991.

Neville, B.W., et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

Regezi, J.A., Sciubba, J.J. Oral pathology: clinical pathologic correlations, ed 5. St Louis: Saunders, 2008.

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary for the Dental Professions, Illustrated, 1st Edition. Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins, 2007.

Bouquot, J.E., Gundlach, K.K.H. Odd tongues: the prevalence of common tongue lesions in 23,616 white Americans over 35 years of age. Quintessence Int. 1986;17:719.

Brannon, R.B., Pousson, R.R. The retrocuspid papillae: a clinical evaluation of 51 cases. J Dent Hyg. 2003;77:180.

Chapnick, L. External root resorption: an experimental radiographic evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:578.

Comfort, M., Wu, P.C. The reliability of personal and family medical histories in the identification of hepatitis B carriers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:531.

Daley, T.D. Pathology of intraoral sebaceous glands. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:241.

Ibsen, O.A.C. Oral cancer: incidence, the diagnostic process, and screening techniques. Dimensions Dent Hyg. 2006;4(10):4.

Ibsen, O.A.C. Diagnosing smoking-related lesions. Dimensions Dent Hyg. 2004;2(9):32–35.

Ibsen, O.A.C. Putting the pieces together. Dimensions Dent Hyg. 2004;2(3):32–35.

Kalan, A., Tarig, M. Lingual thyroid gland: clinical evaluation and comprehensive management. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:340.

Kaugars, G.E., Miller, M.E., Abbey, L.M. Odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:2172.

Lydiatt, D.D., Hollins, R.R., Peterson, G.P. Multiple idiopathic root resorption: diagnostic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:208.

McCann, A.L., Wesley, R.K. A method for describing soft tissue lesions of the oral cavity. J Dent Hyg. 304, 1986.

Neupert, E.A., Wright, J.M. Regional odontodysplasia presenting as a soft tissue swelling. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:193.

Pogrel, M.A., Cram, D. Intraoral findings in patients with psoriasis with a special reference to ectopic geographic tongue (erythema circinata). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:184.

Rosen, D.J., et al. Traumatic bone cyst resembling apical periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1997;68:1019.

Suzuki, M., Sakae, T. A familial study of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1960;18:263.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. After arriving at a differential diagnosis, information from which one of the following categories will best establish a final or definitive diagnosis?

2. The descriptive term that would best be used for a freckle is a:

3. Which one of the following terms describes the base of a lesion that is stalklike?

4. Clinical diagnosis can be used to determine the final or definitive diagnosis of all of the following except:

5. Radiographic diagnosis would contribute to the definitive diagnosis of all of the following except:

6. To determine the presence of blood dyscrasias, which one of the following would provide the most definitive information?

7. When an antifungal ointment or cream is used to treat suspected angular cheilitis, which one of the following diagnostic categories is being used?

8. Yellow clusters of ectopic sebaceous glands commonly observed on the buccal mucosa and evaluated through clinical diagnosis are most likely:

9. A slow-growing, bony hard exophytic growth on the midline of the hard palate is developmental and hereditary in origin. The diagnosis is determined through clinical evaluation. You suspect:

10. The “white line” observed clinically on the buccal mucosa that extends from anterior to posterior along the occlusal plane is:

11. Which one of the following occurs as an erythematous area, is devoid of filiform papillae, is oval to rectangular in shape, and is on the midline of the dorsal surface of the tongue?

12. Which one of the following diagnostic categories would the dental hygienist most easily apply to the preliminary evaluation of oral lesions?

13. These examples of exostoses are found on the lingual aspect of the mandible in the area of the premolars. They are benign, bony hard, and require no treatment. Radiographically they appear as radiopaque areas and are often bilateral. You suspect:

14. Which one of the following terms is most often used when describing mandibular tori?

15. Which of the following conditions is a benign anomaly, has a diffuse gray-to-white opaque appearance on the buccal mucosa, and is most commonly seen in adult black individuals?

16. A patient has the clinical signs of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. The hygienist has the patient begin hydrogen peroxide rinses without culturing the bacterial flora. This action applies to which one of the following diagnostic categories?

17. A small circumscribed lesion usually less than 1 cm in diameter that is elevated and protrudes above the surface of normal surrounding tissue is called a:

18. The base of a sessile lesion is:

19. The identification of which one of the following is not determined by clinical diagnosis?

20. Another term for geographic tongue is:

21. The cause of supernumerary teeth is most likely:

22. Historical diagnosis can include the patient’s:

23. Which condition is most often seen on the buccal mucosa?

24. Which one of the following is not considered a variant of normal?

25. Which cyst is often described as a radiolucency that scallops around the roots of the teeth involved?