Epididymitis and Epididymo-orchitis

Introduction

The epididymis is elongated, tightly coiled duct of up to 4.5 meters in length situated at the posterior border of the testis. It provides for transit, maturation, and storage of spermatozoa which are formed in the testis. During passage through this length of the organ, differentiated sperm cells undergo maturation processes including motility and the potential to fertilize an egg.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Epididymitis, an inflammation of the epididymis, is common and responsible for a significant loss of time from work for men. It is often associated with infection of the testis; in that case the term “epididymo-orchitis” is used. However, some organisms tend to cause infection only of the epididymis. It has been reported that the incidence of epididymitis may range from one to four per 1000 men per year. The average duration that men with epididymitis are absent from work is 1 week.1 With increased understanding of the condition, a decrease in morbidity can be achieved. The peak incidence for epididymitis is between 20 and 29 years of age, but close monitoring is needed to capture any changes in epidemiology due to changes in sexual behavior with more and more boys becoming sexually active at a younger age.

Acute epididymitis is uncommon in infants and is usually associated with underlying genitourinary tract abnormalities. In prepubertal boys, the usual etiologic agents of epididymo-orchitis are coliforms, Pseudomonas, or mumps virus infections. In sexually active adolescents and men below the age of 35 years, epididymoorchitis is mostly due to sexually transmitted pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.2,3 Without the use of antibiotics, up to 30% of gonococcal urethritis may end up in acute epididymitis in this sexually active population. In older men (over 35 years of age), on the other hand, coliforms are more commonly implicated as a complication of urinary tract infection. In this older age group, the organisms commonly identified are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus, or Staphylococcus epidermidis. Increasingly, coliforms are responsible for the higher risk and increased frequency of acute epididymitis in men who have unprotected anal sex with men.4 In heterosexual men, coliforms more often cause epididymo-orchitis, if there has been recent catheterization or instrumentation.

Other causative organisms of epididymitis, secondary to systemic infections, include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Brucella spp., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Treponema pallidum. In post-mortem analyses, it would seem that cases of tuberculous epididymitis occur only if patients have prostatic, renal, or seminal vesicular involvement.5 Furthermore, tuberculous epididymitis tends to present with bilateral inflammation in most cases compared to the mostly unilateral manifestation of coliforms and sexually transmitted pathogens. A high index of suspicion needs to be kept for tuberculous epididymitis in settings of high HIV prevalence as tuberculosis becomes more common in men in such settings. In such patients as well as in post-transplant patients on immunosuppressive therapy, it is important to keep in mind other opportunistic infections known to cause epididymitis, such as histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis. Infection with Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, cytomegalovirus, and Haemophilus influenzae can also occur in these patients.

Clinical Presentation

Acute epididymitis may be sudden or gradual. Clinically, the patient complains of a painful swollen testis (Fig. 55.1), which is unilateral in about 10–30% of patients with a gonococcal infection.6 Men with epididymitis due to sexually transmitted pathogens, such as C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae, often have a history of urethral discharge or dysuria, although some may not show any urethral signs of the infection. History of a recent sexual exposure may be obtained and would be a useful pointer to diagnosis. Epididymitis occurs in either of the testicles with equal frequency. Fever is present in approximately 75% of the patients and chills are reported mostly in elderly patients.7 Pain may also be felt beyond the scrotum in the inguinal region or the abdominal flank on the affected side. Generally, younger patients below 35 years of age show less severe symptoms. The inflammatory process begins in the epididymal tail and extends to the rest of the tube and the testicle, although inflammation of the testis itself is rare. Examination reveals an enlarged and tender epididymis on the affected side with erythema of the overlying scrotal skin in the region of the epididymis (Fig. 55.1).

Fig. 55.1 Scrotal swelling with erythema on the surface due to chlamydial epididymitis. Patient had urethritis 8 days ago, received treatment only for gonorrhea, resulting into development of epididymitis due to untreated Chlamydia.

Simple examination during an acute infection may not easily distinguish between the testis and the epididymis as both structures may be inflamed. The spermatic cord may be swollen and tender. Careful examination of the urethra may reveal a discharge or microscopic urethritis on a Gram stain of a urethral smear. Occasionally, there maybe an accompanying inflammatory hydrocele.

Differential Diagnosis

Testicular torsion, caused by twisting of the spermatic cord, is the most important differential diagnosis of acute epididymitis as it rapidly leads to infarction of the testis. Testicular torsion has a short history of onset and the testis usually lies higher and transverse within the scrotum. This diagnosis is more frequent in prepubertal children. Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency and surgical exploration may need to be considered in this age group.

Tuberculous epididymitis is an unusual but important form of epididymitis, and this is of relatively greater importance in areas of high prevalence of tuberculosis.8 Clinically, it is usually bilateral, non-tender, and firm to palpation. In brucellosis, usually due to Brucella melitensis or Brucella abortus, an orchitis is likely to be clinically more evident than an epididymitis.

Mumps can also cause an acute orchitis and a history of recent mumps infection should be excluded. In this infection, testicular swelling usually develops within a week of parotid swelling.

The differential diagnosis should also include other noninfectious causes of testicular swelling. These include trauma and testicular malignancy. It is important to realize that the peak ages for epididymitis are similar to those for testicular tumors. Thus, whereas a painless testicular mass almost always indicates a tumor, the presence of pain does not necessarily rule out a tumor.

There have also been reports of epididymitis in patients with Behçet disease, polyarteritis nodosa, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura. Other conditions that may complicate a clear diagnosis of epididymitis are varicoceles, herniae, and spermatoceles.

Complications

The following are some of the encountered complications of acute epididymo-orchitis, and are usually a consequence of delayed treatment:

When the inflammation is due to coliforms, severe inflammation may lead to formation of an abscess, testicular infarction, and testicular atrophy.8 If not effectively treated, epididymitis can lead to decreased fertility. If patients present with bilateral epididymitis and bilateral occlusion of the vas deferens or epididymis, they may become totally infertile. Retrospective epidemiologic results also support an association between positive Chlamydia serology and male infertility. However, in most of such studies, the association does not reach the level of statistical significance due to small sample size.9 Chronic epididymitis presents with unilateral or bilateral scrotal pain, sometimes associated with chronic testicular pain (chronic orchalgia), either intermittent or persistent for three or more months in duration. The etiology can be associated with inflammatory, infectious, or obstructive factors but, in many cases, no identifiable etiology can be identified.10

Laboratory Diagnosis

Where laboratory investigation is possible, examination of the urine and urethral smear is a very helpful procedure in differentiating epididymitis from testicular torsion. Urine microscopy should be performed to detect pus cells. Torsion does not give rise to pyuria. A midstream urine sample, without centrifugation, can be useful to make a presumptive diagnosis of epididymitis, if bacteriuria is confirmed as in the case of coliforms and Pseudomonas infections. A midstream urine culture should be performed in all cases of suspected epididymitis. A Gram stain of a urethral smear may aid in the diagnosis of N. gonorrhoeae. Detection of C. trachomatis should also be attempted, where possible, as this pathogen can be the sole cause of epididymitis without N. gonorrhoeae or other pathogens.2 Culture of an epididymal aspirate has been tried to establish a diagnosis of epididymitis in special circumstances. This is not recommended in an out-patient consultation. Some of the special cases that warrant this procedure are recurrent epididymitis in which the etiologic agent cannot be established, failure to respond to effective antimicrobial treatment and epididymitis found on surgical exploration for suspected testicular torsion.

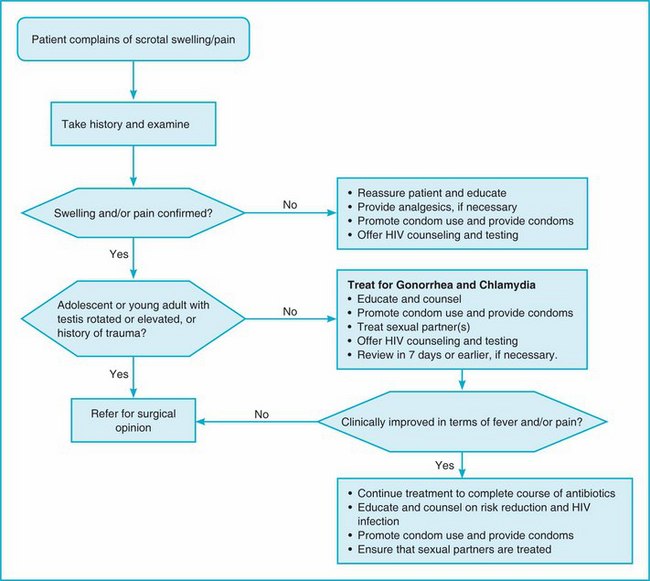

In many settings, however, a laboratory diagnosis cannot be performed for reasons of cost, lack of diagnostic equipment or lack of trained laboratory technicians. In such cases, a syndromic approach to the management of testicular pain and swelling should be followed.

Syndromic Management of Acute Scrotal Swelling

If history suggests it and a urethral discharge is detected then the epididymo-orchitis is most likely secondary to either or both of the sexually transmitted pathogens, N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. It should be remembered that the absence of a urethral discharge does not exclude the presence of STI—history is, therefore, of paramount importance in making the decision. For example, in a report of young military recruits with epididymitis, 16% had gonococcal infection, but only 50% of them with the infection had urethral discharge.11 Figure 55.2 shows a flow chart that can be used to assist in the syndromic management of a scrotal swelling or scrotal pain. If no laboratory diagnosis is possible, it is recommended that the patient be treated at the same time for the two pathogens (Fig. 55.2). Generally, the management of the patient includes bed rest, scrotal support and elevation, pain relief, and appropriate antibiotics. Elevation can be achieved by placing a towel, or some other such material, between the patient's legs while in the supine position. While lying down, scrotal support alone is not sufficient as the scrotum would be dependent and drainage will be delayed. Bed rest should be continued until tenderness has resolved. Pain relief can be provided by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Various other combinations have been tried and shown to hasten the disappearance of pain ahead of inflammatory resolution. Injection of the spermatic cord with xylocaine hydrochloride has been shown to relieve pain immediately and more effectively than the use of antibiotics alone.12

Syndromic treatment should be as follows:

• Effective therapy for uncomplicated gonorrhea plus effective therapy for Chlamydia. A possible syndromic regimen, after taking into account locally determined antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, may include:

ceftriaxone, 250 mg, IM, single dose for gonococcal infections PLUS

ceftriaxone, 250 mg, IM, single dose for gonococcal infections PLUS

doxycycline, 100 mg, orally, twice daily for 10 days or azithromycin 1 g orally as a single dose, for chlamydial infections.

doxycycline, 100 mg, orally, twice daily for 10 days or azithromycin 1 g orally as a single dose, for chlamydial infections.

• Patients in whom gonorrhea and/or Chlamydia are suspected to be the cause of the epididymitis, management of sexual partners must not be overlooked. Sexual partners should be treated for the same infections as the index patient.

• For acute epididymitis most likely caused by enteric organisms, appropriate antibiotics should be given. For example, ofloxacin, 400 mg orally, twice daily for 10 days or levofloxacin 500 mg once daily for 10 days. As E. coli and other coliforms are demonstrating increasing resistance to trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, this combination antibiotic should not be used without laboratory guidance in terms of susceptibility of the organism.

• For severe infections, consideration should be given to intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics directed against coliforms and P. aeruginosa.

Potentially epididymitis has serious consequences in young people. Therefore, more effort should be made to prevent it from occurring. Urethritis should be treated effectively and promptly at the first port of call for any patient. When epididymitis occurs treatment should be prompt. No justification can be made to withhold the use of antibiotics in suspected infectious epididymitis.

References

1. Baumgarten, H. Epididymitis in the workplace. J Fla Med Assoc. 1984; 71:21–22.

2. Berger, R.E., Alexander, E.R., Harnisch, J.P., et al. Etiology, manifestations and therapy of acute epididymitis: prospective study of 50 patients. J Urol. 1979; 121:750–754.

3. Hoosen, A.A., O'Farrell, N., van den Ende, J. Microbiology of acute epididymitis in a developing country. Genitourin Med. 1993; 69:361–363.

4. Berger, R.E., Kessler, D., Holmes, K.K. Etiology and manifestations of epididymitis in young men: correlations with sexual orientation. J Infect Dis. 1987; 155:1341–1343.

5. Medlar, E.M., Spain, D.M., Holliday, R.W. Post-mortem compared with clinical diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis in adult males. J Urol. 1949; 61:1078.

6. Pelouze, P.S. Epididymitis. In Pelouze P.S., ed.: Gonorrhea in the Male and Female, 11th, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1941.

7. Luzzi, G.A., O'Brien, T.S. Acute epididymitis. BJU Int. 2001; 87:747–755.

8. Mittemeyer, B.T., Lennox, K.W., Borski, A.A. Epididymitis: a review of 610 cases. J Urol. 1966; 95:390–392.

9. Ness, R.B., Markovic, N., Carlson, C.L., Coughlin, M.T. Do men become infertile after having sexually transmitted urethritis ? An epidemiologic examination. Fertil Steril. 1997; 68:205–213.

10. Nickel, J.C. Chronic epididymitis: a practical approach to understanding and managing a difficult urologic enigma. Rev Urol. 2003; 5:209–215.

11. Watson, R.A. Gonorrhea and acute epididymitis. Milit Med. 1979; 144:785–787.

12. Kamat, M.H., Del Gaizo, A., Seebode, J.J. Epididymitis: response to different modalities of treatment. J Med Soc NZ. 1970; 67:227–229.