Bacterial Infections of the Oral Cavity

Certain bacteria, viruses and fungi produce diseases, which are manifested in or about the oral cavity. Some of these diseases or lesions are of the specific nature and are produced by a specific microorganism. Others are clinically specific, but may be caused by any of the broad group of microorganisms. This microbial specificity or nonspecificity is characteristic of infectious diseases wherever they may occur in the body, and is necessarily confined to those of the oral cavity.

Scarlet Fever (Scarlatina)

Scarlet fever is a contagious systemic infection occur ring predominantly in children, caused by β-hemolytic streptococci, Streptococcus pyogenes which produces a pyrogenic exotoxin. It is similar in many respects to acute tonsillitis and pharyngitis caused by streptococci, paralleling the occurrence of these conditions in its epidemiology. It is regarded as a separate entity because of the nature of the toxin. A number of different strains of streptococci may produce the disease. The rash occurs because of three exotoxins, A, B, C; previously described as erythrogenic or scarlet fever toxin. These organisms produce clear hemolysis around colonies in blood agar plates. Local erythematous reaction occurs in susceptible individuals injected with exotoxin, but no such reaction was found in those with specific immunity. Various studies suggest that development of scarlet fever may reflect a hypersensitivity reaction requiring prior exposure to the toxin.

Clinical Features

Scarlet fever is common in children. After the entry of the microorganisms into the body, which is believed to occur usually through the pharynx, there is an incubation period of three to five days; after which the patient exhibits severe pharyngitis and tonsillitis, headache, chills, fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Accompanying these symptoms may be enlargement and tenderness of the regional cervical lymph nodes. The diagnosis of scarlet fever is frequently not established until the characteristic diffused, bright, scarlet-skin rash appears on the second or third day of illness. This rash, which is particularly prominent in the areas of the skin folds, is a result of the toxic injury to the endothelium which produces dilatation of the small vessels and consequent hyperemia. These rashes blanch on pressure and typically begin first on the upper trunk, spreading to involve extremities but sparing the palms and soles. Small papules of normal color erupt through these rashes giving a characteristic ‘sandpaper’ feel to the skin. This rash that is particularly prominent in the areas of skin folds is called ‘pastia lines.’ The rash subsides after six or seven days followed by the desquamation of palms and soles. The color of the rash varies from scarlet to dusky-red.

Oral Manifestations

The chief oral manifestations of scarlet fever have been referred to as stomatitis scarlatina. Small punctate red macules may appear on the hard and soft palate and uvula. These are called Forchheimer spots; however, these are not diagnostic since they may be present in other infectious conditions like rubella, roseola, infectious mononucleosis, and septicemia. The palate and the throat are often fiery red. The tonsils and faucial pillars are usually swollen and sometimes covered with a grayish exudate.

More important are the changes occurring in the tongue. Early in the course of the disease, the tongue exhibits a white coating and the fungiform papillae are edematous and hyperemic, projecting above the surface as small red knobs. This phenomenon has been described clinically as ‘strawberry tongue’. The coating of the tongue is soon lost; beginning at the tip and lateral margins, and this organ becomes deep red, glistening and smooth except for the swollen, hyperemic papillae. The tongue in this phase has been termed as the ‘raspberry tongue’. In severe cases, ulceration of the buccal mucosa and palate has been reported, but this appears to be due to secondary infection. Signaling the clinical termination of the disease is the desquamation of the skin, which usually occurs within a week or 10 days. Soon after, the tongue and the remainder of the mucosa assume a normal appearance. Scarlet fever should be differentiated from the other exanthematous diseases like measles and other viral exanthemas, Kawasaki disease, toxic shock syndrome, drug eruptions, and the like.

Complications

Occasional complications may arise referable to local or generalized bacterial dissemination or to hypersensitivity reactions to the bacterial toxins. These may include peritonsillar abscess, rhinitis and sinusitis, otitis media and mastoiditis, meningitis, pneumonia, glomerulonephritis, rheumatic fever, and arthritis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings. Routine blood examination shows marked leukocytosis with increased neutrophilia. There is an elevation of ESR and C-reactive protein. Culturing the flora of intraoral lesions, pharynx, and saliva can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

There are no available methods for the prevention of scarlet fever. The administra tion of antibiotics like penicillin, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin will ameliorate the disease and also helps in controlling possible complications. Local applications like mupirocin topical ointment also can be used to relieve discomfort.

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is an acute, life-threatening, infectious, and communicable disease of the skin and mucous membrane caused by toxemic strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, an anaerobic gram-positive organism. It is characterized by local inflammation and the formation of a grayish adherent pseudomembrane, which bleeds on removal. It occurs in the months of winter in temperate zones and throughout the year in the tropical region. Historically, it was described as Egyptian or Syrian ulcer in the second century.

It is a disease of the children. Humans are the principal reservoirs and the organisms may persist in discharges from the nose, throat, eye, and skin lesions for two to six weeks after infection. It is transmitted mainly by respiratory droplets, direct skin contact and from the skin to the respira tory tract through hands. In some instances carriers of the disease are responsible for dissemination of the microorganisms. Exposure to the diphtheria bacillus, particularly in the adult, may result in a subclinical infection, which is usually sufficient to establish immunity through the development of circulating antitoxins. Infection is most common in groups living in crowded conditions. It can occur in both immunized and partially immunized individuals.

Since 1990, this epidemic has occurred throughout the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Thailand, and Laos. These epidemics are largely due to decreasing immunization coverage among infants, waning immunity in adults, large-scale movement of population, and irregular supply of vaccine. Available data indicate a declining trend of diphtheria in India, due to increasing coverage of child population by immunization. Schick test surveys in India have shown that about 70% of children over the age of three and 99% over the age of five are already immune to diphtheria. Recent diphtheria outbreaks in a number of countries have demonstrated a shift in age distribution of cases to adults and old age people. The outbreaks warrant the need of booster immunization.

Pathogenesis

C. diphtheriae has an air-borne mode of transmission and localizes in the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract. It also invades open skin lesions resulting from insect bites or trauma. Diphtheria is, in fact, a toxemia, since the bacillus remaining at the site of entry multiplies and liberates toxins. These toxins induce initial edema and hyperemia followed by epithelial necrosis and acute inflammation.

Coagulation of the fibrin and purulent exudates produce pseudomembrane and the inflammatory reaction accompanied by vascular congestion extends into the underlying tissues. Thus the pseudomembrane consists of dead cells, leukocytes, erythrocytes, and bacteria. Systemically the toxin produces myocarditis, neuritis, and focal necrosis in various organs including kidneys, liver, and adrenal glands. Cutaneous diphtheria is caused by nontoxemic strains of diphtheria.

Clinical Features

Patients with C. diphtheriae in the respiratory tract are classified as diphtheria cases if the pseudomembrane is present and as diphtheria carriers if the pseudomembrane is absent. The pseudomembrane is seen on the tonsils. It is wash-leather, elevated grayish-green membrane with a well-defined edge surrounded by acute inflammation. The incubation periods for respiratory diphtheria are two to five days and rarely up to eight days. Cutaneous diphtheria is a secondary infection on pre-existing skin lesions, which develops at an average of seven days after the appearance of primary lesions. Various clinical types of diphtheria, classified by the location of the pseudomembrane are tonsillar, pharyngeal, laryngeal, tracheal, nasal, conjunctival, cutaneous, and genital. There may be swelling of the neck (bull neck) and tender enlargement of the lymph nodes.

Onset is gradual. It manifests as fever, sore throat, weakness, dysphagia, headache, and change of voice. Patients without toxicity exhibit discomfort and malaise associated with local infection whereas toxic patients develop restless ness, pallor, and tachycardia and rapidly progressed to vascular collapse. Multiple sites may involve other than the primary site. The spread of infection from one site either upward or downward is common.

Initial findings include erythema of the posterior pharyngeal wall followed by white or gray spots that coalesce to form a thin veil-like membrane, which thickens and becomes gray. The larynx and trachea may be involved primarily or by extension from the pharynx and nose. It manifests as hoarseness of voice, respiratory stridor, and dyspnea, which may progress to severe respiratory obstruction and death in young children owing to the small airway size. Cutaneous manifestations include deep punched-out ulcers with a leathery discharge. Most lesions occur on the extremities but trunk and genital may also be affected.

Oral Manifestations

There is formation of a patchy ‘diphtheritic membrane’ which often begins on the tonsils and enlarges, becoming confluent over the surface. This false membrane is grayish-green, thick, and fibrinous, and is composed of dead cells, leukocytes and bacteria overlying necrotic, ulcerated areas of the mucosa tends to be adherent and leaves a bleeding surface if stripped away. The membrane is asymmetric and extends to involve the tonsil, soft palate and tongue, lips, gingiva, buccal mucosa and site of erupting teeth. Its advancing border is reddened and bleeding occurs on scraping the membrane. The submandibular and anterior cervical nodes are enlarged with soft tissue edema. Severely affected patients will give a bull neck appearance.

In the oral cavity, it appears as nonspecific ulcer. The soft palate may become temporarily paralyzed, usually during the third to fifth weeks of the disease. These patients have a peculiar twang, and may exhibit nasal regurgitation of liquids during drinking. The paralysis usually disappears in a few weeks or a few months at the most. If the infection spreads unchecked in the respiratory tract, the larynx may become edematous and covered by the pseudomembrane which results in a husky voice. This is especially serious because it produces a mechanical respiratory obstruction and the typical cough or diphtheritic croup. If the airway is not cleared, suffocation may result.

Complications

During or after this disease complications frequently arise in the cardiovascular and nervous systems as a result of toxemia. Thus both myocarditis and polyneuritis may develop, but usually there is complete recovery. Kidney lesions, particularly acute interstitial nephritis, are also possible serious sequelae. Obstruction of the airway, acute circulatory failure, post diphtheria paralysis, pneumonia, bleeding and otitis media are other complications.

The mortality rate is still of such proportions that diphtheria should be considered a serious disease. In the past this disease was a leading cause for death in children and was referred to as ‘the strangling angel of children’. It should be differentiated from other conditions including streptococcal pharyngitis, Vincent’s angina, Ludwig’s angina, retropharyngeal and peritonsillar abscess, infectious mononucleosis, candidiasis, leukemia, and agranulocytosis.

Diagnosis is mainly based on clinical signs and symptoms but definite diagnosis is arrived by the isolation of organisms from the affected sites. Material should be obtained beneath the membrane or a portion of the membrane itself can be submitted for culture. Various media include Pai agar and cystine-tellurite agar and special stains like Albert’s stain, Ponder’s stain or Neisser’s stains to demonstrate metachromatic granules.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a specific infectious granulomatous disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It remains a major health problem in most developing countries. It commonly affects lungs but also affects the intestines, meninges, bones, joints, lymph glands, skin, and other tissues of the body. The disease also affects animals like cattle and is known as bovine tuberculosis; and is sometimes communicated to man.

Etiology

M. tuberculosis is a facultative intracellular parasite. Human strains are responsible for many cases, but the bovine strain may also produce illness through the ingestion of unpasteurized cow’s milk. Rarely atypical or opportunistic mycobacteria can cause pulmonary or generalized infection in immunocompromised individuals.

M. tuberculosis is a rod-shaped, nonspore forming, and thin aerobic bacteria called acid-fast bacilli, due to the fact that once stained, it cannot be decolorized by acid alcohol. Its acid-fastness is due to the high content of mycolic acids, long chain cross-linked fatty acids and other cell wall lipids. Males are more affected than females in India though it affects all ages, from an average of 1% in the under-five age group.

Epidemiology

Developed countries have achieved spectacular results in the control of tuberculosis. Incidence has steadily declined in developing countries as well. This is due to early and accurate diagnosis of the disease through various tools and improved socioeconomic conditions. In developing countries, the Southeast region, the Western Pacific, and Africa accounts for 95% cases of TB. Among the world population, the Southeast Asian region carries a disproportionate 88% of the world’s burden of TB.

India accounts for nearly one fifth (20%) of the global burden of TB. Every year 1.8 million persons develop tuberculosis of which about 0.8 million are new smear-positive highly infectious cases and about 0.32 million people die of TB every year. The vulnerability to TB in developing countries results from poverty, economic recession and malnutrition. Many new patients have multidrug resistance to TB. People with HIV infection are much more likely to develop TB. An increase in HIV prevalence represents a serious threat to TB control in India. WHO has launched a strategy for controlling TB called DOTS or Directly Observed Therapy Short-term, a community based treatment protocol. Today in India it is recognized as fastest expanding program.

Pathogenesis

The interaction of the bacilli and the host begins when droplet nuclei from infectious patients are inhaled. The majority of the bacilli are trapped and exhaled by ciliary action and a fraction less than 10% enters alveoli.

In the initial stage of the host-bacterial interaction, either host’s macrophages control the multiplication of the bacteria or the bacteria grow and kill the macrophages. Nonactivated monocytes attracted from blood stream to the site by various chemotactic factors ingest the bacilli released from the lysed macrophages. Initial stages are asymptomatic; about 2–4 weeks after infection tissue damaging and macrophage activating responses develop. With the development of specific immunity and accumulation of a large number of activated macrophages at the site of primary lesion, granulomatous reaction or tubercles are formed. The hard tubercle consists of epithelioid cells, Langhans giant cells, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. These lesions develop when host resistance is high. Due to cell-mediated immunity in the majority of individuals, local macrophages are activated and lymphokines are released, which neutralize the bacilli and prevent further tissue destruction. The central part of the lesion contains caseous, soft, and cheesy necrotic material (caseous necrosis). This necrotic material may undergo calcification at a later stage called Ranne complex, in the lung parenchyma and hilar lymph nodes in few cases. Caseous necrotic material undergoes liquefaction and discharges into the lungs leading to the formation of a cavity. Spontaneous healing of the cavity occurs either by fibrosis or collapse. Calcification of the cavities may occur in which bacteria persist.

In early stages, the spread of infection is mainly by macrophages to lymph nodes, other tissues, and organs. However, in children with poor immunity, hematogenous spread results in fatal military TB or tuberculous meningitis.

Clinical Features

The signs and symptoms of tuberculosis are often remarkably inconspicuous. The patient may suffer episodic fever and chills, but easy fatigability and malaise are often the chief early features of the disease. There may be gradual loss of weight accompanied by a persistent cough with or without associated hemoptysis.

Tuberculosis is either pulmonary or extrapulmonary. Pulmonary TB may be primary, secondary, or miliary. Extrapulmonary sites include lymph nodes, pleura, genitourinary tract, bones, joints, meninges, and peritoneum. As a result of hematogenous dissemination in HIV infected individuals, the extrapulmonary type is seen more commonly.

Primary pulmonary TB is usually seen in children but may also occur in adults. In a majority of cases, it is asymptomatic. A few may be present with febrile illness and cough, which may be dry or productive.

Symptoms of post-primary TB or secondary TB include fever, cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis.

Symptoms of miliary TB in children include acute febrile illness but in adults it is more insidious with gradual develop ment of ill health, anorexia, loss of weight, and fever. Bilateral crackles on auscultation, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy may be present. Choroid tubercles are seen in children, but are rare in adults.

Tuberculous infection of submandibular and cervical lymph nodes, or scrofula, a tuberculous lymphadenitis, may progress to the formation of an actual abscess or remain as a typical granulomatous lesion. In either case, swelling of the nodes is obvious clinically. They are tender or painful, often show inflammation of the overlying skin, and when an actual abscess exists, typically perforate and discharge pus. It has been suggested that this specific form of tuberculosis probably arises as a result of lymphatic spread of organisms from a focus of infection in the oral cavity such as the tonsils. However, as Popowich and Heydt have stated, no published studies have confirmed the relationship between tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis and a primary source of infection else where. For example, in the series of 22 cases reported by Ord and Matz, there was no history or clinical evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in any patient. These investigators also emphasized that this disease can be caused by atypical mycobacteria and also that organisms frequently cannot be cultured from the lesions.

Primary tuberculosis of the skin or lupus vulgaris may occur either in children or adults and is a notoriously persistent disease. It appears as papular nodules, which frequently ulcerate. These are particularly common on the face, but may occur anywhere.

Oral Manifestations

Tuberculous lesions of the oral cavity do occur, but are relatively uncommon. Reported studies on incidence vary considerably. The studies of Farber and his associates indicated that less than 0.1% of the tuberculous patients whom they examined exhibited oral lesions. Katz on the other hand, found that approximately 20% of a series of 141 patients examined at autopsy manifested such lesions, the majority of which occurred on the base of the tongue and were not discovered clinically. The obscure location of the tuberculous lesions found by Katz might account for the disparity in incidence of occurrence in these studies.

There is general agreement that lesions of the oral mucosa are seldom primary, but rather secondary to pulmonary disease. Although the mechanism of inoculation has not been definitely established, it appears most likely that the organisms are carried in the sputum and enter the mucosal tissue through a small break in the surface. It is possible that the organisms may be carried to the oral tissues by a hematogenous route, to be deposited in the submucosa and subsequently to proliferate and ulcerate the overlying mucosa.

The possibility that the dentist may contract an infection from his contact with living tubercle bacilli in the mouth of patients who have pulmonary or oral tuberculosis is a problem of great clinical significance. It has been shown on numerous occasions that the viable acid-fast microorganisms may be recovered from swabs or washings of the oral cavities of tuberculous patients. Abbott and his associates reported that tubercle bacilli were cultured from 45% of 300 samples of water used to wash the teeth and gingiva of 111 tuberculous patients.

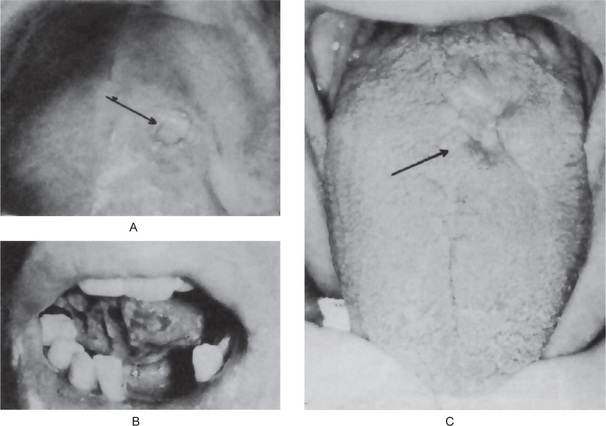

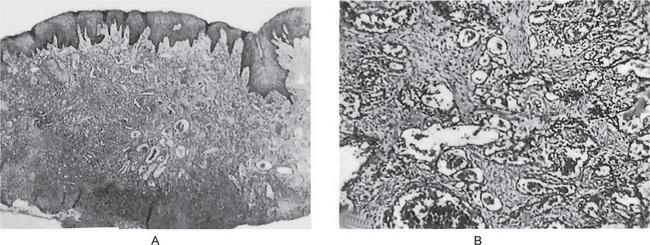

Lesions of secondary tuberculosis may occur at any site on the oral mucous membrane, but the tongue is most commonly affected, followed by the palate, lips, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and frenula. The usual presentation is an irregular, superficial or deep, painful ulcer which tends to increase slowly in size (Fig. 5-1A,B,C). It is frequently found in areas of trauma and may be mistaken clinically for a simple traumatic ulcer or even carcinoma. Occasional mucosal lesions show swelling, granular, nodular or fissured lesions, but no obvious clinical ulceration. Primary oral tuberculosis usually involves gingiva and is present as diffuse, hyperemic, nodular, or papillary proliferation of the gingival tissues (Figs. 5-2, 5-3). Primary oral tuberculosis is usually associated with regional lymphadenopathy.

Figure 5-2 Tuberculous gingivitis. The infection in (A) was restricted to the gingival tissues, but in (B) had extended to the palate and lip (B, Courtesy of Dr Cesar Lopez).

Figure 5-3 Primary tuberculous of gingiva. Source: Anisha CR, Sivapathasundharam B. Primary tuberculosis of gingiva. J Indian Dent Assoc, 2000, 71: 144–45.

Tuberculosis may also involve the bone of the maxilla or mandible. One common mode of entry for the microorganisms is into an area of periapical inflammation by way of the blood stream; an anachoretic effect that has been noted in the oral cavity under other circumstances. It is conceivable also that these microorganisms may enter the periapical tissues by direct immigration through the pulp chamber and root canal of a tooth with an open cavity. The lesion produced is essentially a tuberculous periapical granuloma or tuberculoma. These lesions were usually painful and sometimes involve a considerable amount of bone by relatively rapid extension.

Diffuse involvement of the maxilla or mandible may also occur, usually by hematogenous spread, but sometimes by direct extension or even after tooth extraction. Tuberculous osteomyelitis frequently occurs in the later stages of the disease and has an unfavorable prognosis.

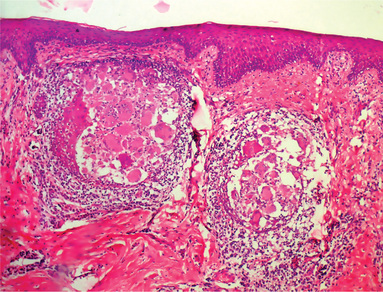

Histologic Features

Tuberculous lesions in the mouth do not differ microscopically from tuberculous lesions in other organs of the body. The characteristic histopathologic appearance is due to the cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Formation of granuloma exhibiting foci of caseous necrosis surrounded by epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, and occasional multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 5-4). Caseous necrosis is not inevitably present, however.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of active infection must be confirmed by demonstration of the organisms by special microbial stains and culture of the infected tissue or sputum. The presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in sputum smear is the gold standard for the diagnosis of TB. Imaging techniques like radiograph of the affected part like chest and tuberculin test are most useful in supplementing the diagnosis of TB.

CT scan is used to diagnose mediastinal or hilar lymph-adenopathy, cavities and intralesional calcification. Postcontrast peripheral enhancement of a lymph node is taken as indirect evidence of tuberculous etiology. A high resolution CT scan can be used to differentiate miliary TB and other diffuse forms of TB from other diffuse lung diseases. MRI is most useful for diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB.

Identification of Mycobacteria from Respiratory Specimens

The demonstration of tubercle bacilli in a respiratory specimen like sputum is a direct evidence of TB. WHO defines any patient whose sputum smear is positive for acid-fast bacilli as a case of pulmonary tuberculosis. Respiratory specimens can be subjected to smear and microscopy for acid-fast bacilli, as well as culture. The following respiratory specimens can be used to demonstrate Mycobacterium, sputum, spot samples collected early morning, laryngeal swab, bronchoalveolar lavage, transtracheal aspiration, or gastric contents aspirated by a nasogastric tube in children who swallow sputum.

Microscopical smears for acid-fast bacilli are stained by the following methods: Ziehl-Nielsen (Z-N) staining, Kinyoun’s cold staining methods, and rhodamine staining for fluorescent microscopy. A minimum of five acid-fast bacilli on fluorescent microscopy and three on Z-N stain ing is reported as positive. A sputum smear examination is less than 60% sensitive.

Mycobacterial Culture

Conventional Mycobacterium cultures are done on Lowenstein-Jensen medium or one of the agar based media like Middlebrook medium. It takes four to six weeks for the growth of M. tuberculosis.

Other faster methods of culture:

• Rapid slide culture technique involves growing Mycobacterium on slides examining microcultures under a microscope.

• Radiometric culture method is based on the detection of utilization of a radioisotope of carbon by mycobacteria.

Tuberculin test or the Mantoux test involves subcutaneous injection of 0.1 ml of 5 tuberculin units of purified protein derivative of Siebert stabilized with Tween 80 or 1 tuberculin unit of PPDRT 23 into the forearm. It is positive if induration is seen after 48–72 hours. The maximum diameter of the induration measured by palpation and not redness, is recorded and interpreted as follows: more than 15 mm or ulceration, strongly positive; more than 10mm, positive; 5–9 mm, indeterminate; and less than 5mm, negative.

The tuberculin skin test has greater value in excluding tuberculosis than in diagnosing it. A positive reaction indicates that a Mycobacterium has replicated in the tissues of the individual at some time but does not indicate an active disease. A strongly positive test may indicate recent infection. The test is positive in 85% of infected individuals but may be falsely negative in tuberculosis pleurisy, miliary tuberculosis, immuno suppressed conditions, and viral fevers. 10% of recent tuberculin converters may develop active disease in their life time and 5% do so within the first two years of infection.

Specific purified protein derivative (PPD) is available for the diagnosis of atypical mycobacterial strains. In HIV positive patients, when the CD4 count goes below 400, tuberculin energy is present and reflects the immune status of the host.

Newer methods of diagnosis of tuberculosis include radioimmunoassays (RIAs), soluble antigen fluorescent antibody (SAFA) test and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the bacterial DNA, and antibody assays to detect the release of interferon gamma in response to mycobacteria.

Treatment

Multiple drug therapy is often recommended as M. tuberculosis mutates and resists single drug therapy. Isoniazid (INH) combined with rifampicin for nine months or INH, rifampicin and pyrazinamide for two months followed by INH and rifampicin for four months. Other drugs used are streptomycin and ethambutol.

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease)

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae. It multiplies very slowly and the incubation period is about five years. It may take as long as 20 years for the symptoms to develop. The disease is only slightly contagious. It mainly affects skin, peripheral nerves, the upper respiratory tract, eyes, and testes, but also affects muscles, bones, and joints. When untreated, it results in characteristic deformities. Nowadays because of early diagnosis and induc tion of appropriate therapy, major complications can be prevented. Binford et al, have published the most thorough and concise review of this disease. Recent studies and reports indicate that the incidence and prevalence is reduced due to multidrug therapy.

Etiology

M. leprae is an obligate intracellular, gram-positive, acid-fast bacillus. It is the only bacterium to infect peripheral nerve. It is unique in exhibiting dopa oxidase activity and acid fastness. It grows best in cooler tissues like skin, peripheral nerves, upper respiratory tract, anterior chamber of the eye, and testes; sparing warmer areas like axilla, groin, scalp, and midline of back. Taking smears from the skin, nasal mucosa of the affected persons, and staining with the Ziehl and Nielsen method can demonstrate the presence of bacilli. Living leprosy bacillus appears as solid staining pink rod whereas non-living leprosy bacilli may be granular or fragmented. It can be grown well in mouse footpad and nine banded armadillo and grows at 30–33° C with a doubling time of 12 days. It can remain viable in the environment for 10 days.

Epidemiology

Leprosy is almost exclusively a disease of developing countries. It is common in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific. Africa has the highest disease prevalence and Asia has the most cases. More than 60% of the cases occur in India, China, Myanmar, Indonesia, Brazil, and Nigeria. Leprosy is still endemic in 28 countries. India accounts for 80% of the detection of leprosy cases in the world. The annual case detection rate in India is among the highest in the world (53 per 100,000).

In India prevalence is high in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and West Bengal. According to WHO, the official reports received from 109 countries and territories, the global registered prevalence of leprosy at the beginning of 2007 stood at 224,717 cases, while the number of new cases detected during 2006 were 259,017. Leprosy is very rare in infants and has a bimodal age distribu tion with peaks at 10–14 and 35–44 years. The mode of infec tion is not known but the probable spread could be through nasal secretion.

Pathogenesis

An immunologic and epidemiological study suggests most people develop a subclinical infection and very few develop infection. Once infected, both cell mediated and humoral responses are elicited by bacterial antigen DNA glycolipids. Lipoarabinomannan, a component of the cell membrane, induces immune suppression by inhibiting the interferon gamma mediated activation of macrophages.

The bacteria are taken by histiocytes in the skin and Schwann cells in the nerves. This usually results in an inflam matory response involving histiocytes and lymphocytes. It is clinically called indeterminate type represented as hypopigmented or erythematous macule. The clinical spectrum and ultimate outcome of disease depends upon the intensity of specific cell mediated immunity. Individuals prone to tuberculoid type have an intense cell mediated immune response and low bacillary load; whereas, patients with lepromatous type have low specific cell mediated immune response and a high bacillary load. These two different types are genetically controlled.

Clinical Features

Various types of clinical presentation occur in patients infected with this bacillus corresponding to patient’s immune response. Leprosy manifests in two polar forms, namely, tuberculoid type and lepromatous type. Host resist ance is high in tuberculoid type.

Between these two, the borderline and indeterminate forms occur depending upon the host response.

General features of leprosy are hypopigmented patches, partial or total loss of cutaneous sensation in the affected areas. The earliest sensation to be affected is usually light touch. The thickening of nerves and the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the skin or nasal smear are common. Tuberculoid lesions are characterized by single or multiple macular, erythematous eruptions, with dermal nerve and peripheral nerve trunk involvement resulting in the loss of sensation, often accompanied by the loss of sweating of the affected skin. The lepromatous lesions develop early erythematous macules or papules that subsequently lead to progressive thickening of the skin and characteristic nodules. These may develop in considerable numbers on any skin area and produce severe disfigurement.

Facial paralysis occurs with some frequency due to facial nerve involvement, and this has been discussed by Reichart et al. Features of advanced disease are nodules or lump in skin of the face and ears, plantar ulcers, loss of fingers and toes, nasal depression, foot drop, claw toe, and others. Although the disease is a crippling and disfiguring one, it runs a chronic course and seldom causes sudden death.

Oral Manifestations

The oral lesions that have been reported generally consist of small tumor like masses called lepromas, which develop on the tongue, lips, or hard palate. These nodules show a tendency to break down and ulcerate. Gingival hyperplasia with loosening of the teeth has also been described, but Reichart and his associates found that most of the gingival and periodontal changes occurring in a group of 30 leprosy patients were nonspecific.

Paralysis of facial and maxillary division of trigeminal nerve is reported. The dental manifestations are described as odontodysplasia leprosa. Premaxilla is affected in childhood due to granulomatous involvement. There will be a circumferential hypoplasia, shortening of roots, usually involving maxillary anterior teeth. Long standing lepromatous lesions may show granulomatous invasion of pulp and pinkish discoloration of crowns.

Histologic Features

The typical granulomatous nodule shows collections of epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in a fibrous stroma. Langhans type giant cells are variably present. Sheets of lymphocytes with vacuolated macrophages called lepra cells are scattered throughout the lesions. In tuberculoid pattern, there is a paucity of organisms and they can be demonstrated only with acid-fast stains in contrast to lepromatous type where there is an abundance of organisms.

Diagnosis is based mainly on clinical and bacteriological examination. Culturing of the organism is difficult. So far the organism has been grown in the footpads of mice and armadillos.

Nasal smears and scrapings stained with modified Ziehl-Nielsen method to detect lepra bacilli at a concentration greater than 1011 gm of tissue. The morphological index is a measure of the number of AFB in skin scrapping that stain uniformly bright correlated with viability.

The bacteriologic index, a logarithmic scaled measure of density of M. leprae in the dermis, may be as high as 4t-6t in untreated patients falling by one unit per year during effective therapy.

Other investigations are skin biopsy, nerve biopsy, and foot culture histamine test. Tests for humoral response are monoclonal antibodies, ELISA, PCR, etc. In children, the sweat function test is used.

Leprosy should be differentiated from sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, lupus vulgaris, lymphoma, syphilis, yaws, and other disorders having hypopigmentation.

Treatment

Specific long-term chemotherapy is initiated upon diagnosis. In 1981, WHO study group recommended multidrug therapy (MDT) and it consists of rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine. The widespread use of MDT dramatically reduces the disease burden. Rifampicin and dapsone for six months in case of tuberculoid type and rifampicin and dapsone along with clofazimine in case of lepromatous type is usually advocated. However, drug regimen evaluation is very difficult in certain situations. Once the infection is treated, the management is directed towards the reconstruction of the damage caused by this disease.

Actinomycosis

Actinomyces species are classified as anaerobic, gram positive and filamentous bacteria despite their fungal and bacterial characteristics. Actinomycosis is a chronic granulomatous suppurative and fibrosing disease caused by anaerobic or microaerophilic gram-positive nonacid fast, branched filamentous bacteria. They are a normal saprophytic component of oral flora, colon, and vagina and none are known to be recoverable from the environment.

Most of the species isolated from actinomycotic lesions have been identified as A israelii, A viscosus, A odontolyticus, A naeslundii or A meyeri. These microorganisms have been identified in dental plaque, dental calculus, necrotic pulp, and tonsils.

These microorganisms were believed to be fungi at one time. However, as our knowledge of their biochemical and serologic aspects evolved, it became apparent that they were actually bacteria, their filaments frequently breaking up into bacillary and coccoid forms.

The usual pattern of this disease is one characterized chiefly by the formation of abscesses that tend to drain by the formation of sinus tracts. If the pus from the abscesses is examined on a clean glass slide, it shows the typical ‘sulfur granules’ or colonies of organisms, which appear in the suppurative material as tiny, yellow grains. Another infection that produces this type of sulfur granules is botryomycosis. Actinomycosis is classified anatomically according to the location of the lesions, and thus we recognize:

It is well established that the actinomycete is a common inhabitant of the oral cavity even in the complete absence of any clinical manifestations of specific infection. Thus, the organisms may be cultured from carious teeth, nonvital root canals, tonsillar crypts, dental plaque, calculus, gingival sulcus, and periodontal pockets.

The pathogenesis of actinomycosis is not entirely known. lt appears to be an endogenous infection and not communicable. Furthermore, it does not appear to be an opportunistic infection in a situation of depressed cell-mediated immunity. Trauma seems to play a role in some cases by initiating a portal of entry for the organisms, since they are not highly invasive. Thus the extracted socket, periodontal pocket, nonvital tooth, or mucosal abrasion may act as the portal of entry for the infection.

Epidemiology

Infection occurs throughout the lifetime with peak incidence in the middle age. Males are more commonly affected than females. Incidence has decreased presently due to improved oral hygiene and antibiotics.

Pathogenesis

The disruption of the mucosal barrier is the main step in the invasion of bacteria. Initial acute inflammation is followed by a chronic indolent phase. Lesions usually appear as single or multiple indurations. Central fluctuance with pus containing neutrophils and sulphur granules is diagnostic of the disease. The fibrous walls are typically described as woody. It occurs in association with HIV infection, transplantation, chemotherapy, herpes, and cytomegaloviral ulcerative mucosal lesions. It is also reported in osteoradionecrosis and in patients with systemic illness.

Clinical Features

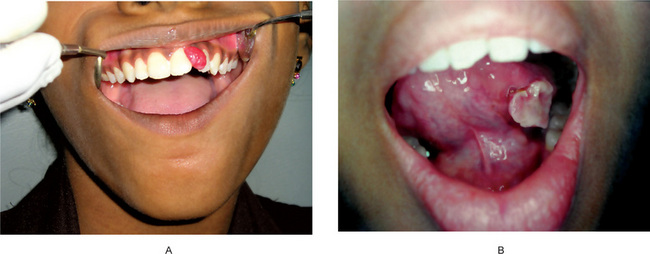

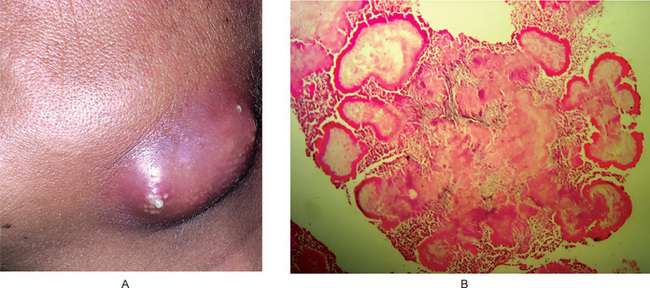

Cervicofacial actinomycosis is the most common form of this disease and is of the greatest interest to the dentist. It has been emphasized by Norman that two-thirds of all cases are of this type. Stenhouse and associates, who also emphasized the surprisingly high incidence of occurrence of Actinomyces in routine pathologic and bacteriologic specimens, have reported a series of 39 cases of cervicofacial and intraoral actinomycosis. The organisms may enter the tissues through the oral mucous membranes and may either remain localized in the subjacent soft tissues or spread to involve the salivary glands, tongue, very rarely gingiva, bone or even the skin of the face and neck, producing swelling and induration of the tissue. These soft tissue swellings eventually develop into one or more abscesses, which tend to discharge upon a skin surface, rarely a mucosal surface, liberating pus containing the typical ‘sulfur granules’ (Fig. 5-5 A). The skin overlying the abscess is purplish red, indurated and has the feel of wood or often fluctuant. It is common for the sinus through which the abscess has drained to heal, but because of the chronicity of the disease, new abscess develop and perforate the skin surface. Thus the patient, over a period of time, may show a great deal of scarring and disfigurement of the skin.

Figure 5-5 Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Clinical photograph (A) showing multiple graining abscess and photomicrograph (B) showing actinomycotic colony in a smear of the pus (Courtesy of Dr Leela Poonja, Dr G Sriram, Dr Vaishali Natu).

The infection of the soft tissues may extend to involve the mandible, or less commonly, the maxilla which results in actinomycotic osteomyelitis. If the bone of the maxilla is invaded, the ensuing specific osteomyelitis may eventually involve the cranium, meninges, or the brain itself. Once the infection reaches the bone, the destruction of the tissue may be extensive.

Such destructive lesions within the bone may occur or localize at the apex of one or more teeth and simulate a pulp-related infection such as a periapical granuloma or cyst. Such a case has been reported by Wesley and his colleagues, who noted 12 other similar cases in the literature.

Abdominal actinomycosis is an extremely serious form of the disease and carries a high mortality rate. In addition to general ized signs and symptoms of fever, chills, nausea and vomiting, intestinal manifestations develop, followed by symptoms of the involvement of other organs such as the liver and spleen.

Pulmonary actinomycosis produces similar findings of fever and chills accompanied by a productive cough and pleural pain. The organisms may spread beyond the lungs to involve adjacent structures.

Histologic Features

The typical lesion of actinomycosis, either in soft tissue or in bone, is essentially a granulomatous one showing central abscess formation within which may be seen the characteristic colonies of microorganisms. These colonies appear to be floating in a sea of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, often associated with multinucleated giant cells and macrophages particularly around the periphery of the lesion. The individual colony, which may appear round or lobulated, is made up of a meshwork of filaments that stains with hematoxylin, but shows eosinophilia of the peripheral club shaped ends of the filaments (Fig. 5-5 B). This peculiar appearance of the colonies, with the peripheral radiating filaments, is the basis for the often-used term ‘ray fungus.’ The tissue surrounding the lesion exhibits fibrosis. Methenamine silver stain can demonstrate the organisms better.

Diagnosis

It should be differentiated from osteomyelitis caused by other bacterial and fungal organisms and soft tissue infections caused by staphylococcus. The diagnosis of action-mycosis depends not only upon clinical findings in the patient and the demonstration of the organisms in the tissue section or smear, but also upon their culture. However, as Brown pointed out in his extensive review of 181 cases of actinomycosis, the organisms are difficult to culture. Of the 67 cases in which culture was attempted, the organism was isolated in only 16 instances. Various organisms isolated are A israelii, A. naeslundii, A. odontolyticus, A. viscosus, A. meyeri, A. gerencseriae, and Propionibacterium propionicum. They are established but are a less common cause of the disease. Most actinomycosis is polymicrobial. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Eikenella corrodens, Enterobacteriaceae and species of Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, Capnocytophaga, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are commonly isolated depending upon the site of infection.

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of this disease is difficult and has not been uniformly successful. Long standing fibrosis cases are treated by draining the abscess, excising the sinus tract with high doses of antibiotics. Long term high dose penicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin have been used most frequently, but the course of the disease is still often prolonged, In addition to this surgical drainage of the abscesses and excision of sinus tract is necessary to accelerate healing.

Botryomycosis (Bacterial actinophytosis, actinobacillosis)

Botryomycosis is a chronic granulomatous infection which was recognized over 130 years ago when it was first found to affect horses. Since that time, approximately more than 50 cases occurring in humans have been reported in literature, and the first case involving the oral cavity was reported by Small and Kobernick. There is some confusion as to the actual causative organ ism in this disease, although an Actinobacillus has been thought to be the one involved. Nevertheless, a variety of other types of organisms have been reported which may or may not represent secondary invaders. The Actinobacillus is often characterized as an ‘associate’ organism with the Actinomycetes, and some workers feel that the presence of Actinobacilli is necessary for the disease process of actinomycosis. However, actinomycosis is known to occur from a ‘pure culture’ of Actinomycetes. Whether ‘pure cultures’ of Actinobacilli can produce botryomycosis is not known, but many workers believe that a number of common bacteria such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Escherichia, Pseudomonas and probably many others may serve as etiologic agents of the disease.

Clinical Features

Human botryomycosis is usually a localized granulomatous infection of the skin or mucosa. It has been reported in patients with impaired immunity or with underlying systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cystic fibrosis or HIV infection. It may disseminate, involving the liver, lungs or kidneys, in which case the disease is usually fatal. The significance of this disease lies in the fact that the localized infection may closely mimic actinomycosis by producing a chronic granulomatous mass with multiple ulcers and sinuses. The oral case reported by Small and Kobernick involved the tongue and presented clinically as a firm, nodular infiltration of the body and base of the tongue. However, there were no sinuses present.

Differential diagnoses for botryomycosis include mycetoma, tuberculosis, nocardiosis, cat-scratch disease, and fungal infections.

Histologic Features

The chronic granulomatous nodules are characterized by the presence of suppurative foci which contain grains or granules that are recognized as forming around microorganisms in certain cases as apparently a nonspecific reaction between agent and host, possibly related to hypersensitivity. In the ordinary H and E stained section these granules may be indistinguishable from those of actino-mycosis. These grains or granules are eosinophilic and PAS negative and negative to methenamine silver. The eosinophilic, peripheral clubs formation typical of actinomycetes is usually not identifiable in this disease.

Treatment

The suggestion has been made that botryomycosis may be caused by a variety of different microorganisms of low virulence, and therefore, the pathogenesis may be related more to a modified host resistance or tissue hypersensitivity than to a specific microorganism. Therefore, treatment is nonspecific. However surgical intervention aids in cure.

Tularemia (Rabbit fever)

Tularemia is a disease caused by the gram-negative, non-motile, bacillus Francisella tularensis, also known as Bacterium tularensis and Pasteurella tularensis. This infection is contracted through contact with infected rodents and rabbits. This expo sure and subsequent infection may occur during skinning and dressing freshly killed infected animals, through ingestion of contaminated meat and water, or through the bite of an infected deer fly or tick. This disease is highly communicable from infected mammals to human. The organisms can persist for longer period of time in mud, water and decaying animal carcasses.

Clinical Features

Based on the site of infection tularemia has six characteristic clinical syndromes namely ulceroglandular (the most common type), glandular, oropharyngeal, pneumonic, oculoglandular and typhoidal. After a variable incubation period of upto seven days, the patient usually suffers a sudden headache, nausea, vomiting, chills, and fever. A single cut or sore on the skin develops into a suppurative ulcer. The lymphatic vessels become swollen and painful and the lymph nodes remarkably enlarged. This general sequel of events is the most common course of the disease and is called ulceroglandular tularemia. The eyes also become involved, with conjunctivitis developing through localization of the disease in the conjunctivital sac, oculoglandular tularemia. Tularemic pneumonia and pleuritis are complications of the disease, which may eventuate in gangrene and lung abscesses.

The disease occurs most frequently in adults. However, as Hughes has reported, children are sometimes affected and, in such cases, the correct diagnosis may be easily overlooked.

Oral Manifestations

The oral lesions account for 3–4% of all cases and are manifested as necrotic ulcers of the oral cavity or pharynx, usually accompanied by severe pain. In some cases it has been reported that a generalized stomatitis develops rather than isolated lesions; single nodular, masses eventually developing into abscesses have also been described. Regional lymphadenitis may arise in the submaxillary and the cervical groups of nodes.

Treatment

The disease responds well to antibiotic therapy. Streptomycin is the drug of choice. This disease also responds to adequate doses of gentamicin and tetracy cline. Before the availability of the newer antibiotics, the disease was considered a serious one and even today, in some persons, it may run such a fulminating course that death occurs despite all forms of therapy.

Melioidosis

Melioidosis is a specific infection in man and animals, caused by the bacillus Burkholderia pseudomallei, an aerobic, gramnegative nonacid-fast, and rod-shaped bacilli. This disease is endemic in certain areas of the far East, including Burma, Ceylon, India, Indochina, Malaysia, Thailand and Dutch East Indies. Military operations in that part of the world by United States Armed Forces have increased the significance of this disease, and cases have now been diag nosed in American servicemen who have returned from duty in Southeast Asia.

Clinical Features

There are two recognized forms of the disease, acute and chronic. In the acute form, the patients rapidly develop a high fever, evidence of acute pulmonary infection, diarrhea, and hemoptysis. There is widespread visceral involvement as a result of hematogenous dissemination of microorganisms. Death, as a result of fulminating septicemia may occur in a few days to weeks.

The chronic form of the disease usually develops in patients who have survived the acute form. It is of granuloma tous type, characterized by multiple, small, nonspecific abscesses occurring subcutaneously or in the viscera, lymph nodes or bones, which often develop draining sinus tracts. These may involve the cervicofacial area and mimic fungal infection or tuberculosis.

The most important risk factor for developing melioidosis is diabetes mellitus. Other risk factors include thalassemia and kidney disease. The mode of transmission is not from one man to another man or from contact with the affected animals or animal excretions. The causative organism is abundant in soil and stagnant water where the disease occurs. It is believed that most human infections occur through contamination of skin abrasions by the soil or water. Diagnosis is usually made by culturing the organism from any one of the clinical sample and the throat sample is most sensitive.

Tetanus (Lock-jaw)

Tetanus is an acute infection of the nervous system characterized by intense activity of motor neurons and results in severe muscle spasms. It is caused by the exotoxin of the anaerobic, gram-positive bacillus Clostridium tetani that is commensal in human and animal gastrointestinal tracts and soil. It acts at the synapse of the interneurons of inhibitory pathways and motor neurons to produce blockade of spinal inhibition. The organisms can enter the body through even the most trivial injury.

Epidemiology

Tetanus is now a comparatively rare disease in developed countries. It occurs sporadically and almost always affects nonimmunized persons, partially immunized and even, less often, fully immunized individuals. It is common in areas where the soil is cultivated, rural areas, warm climates, and during summer. It is more common in males than females. It usually occurs after acute injuries such as laceration or abrasion. It may be acquired during farming, gardening, etc. It may also occur in patients with abscesses, ulcers and gangrene. It is associated with burns, frostbite, middle ear infection, surgery, abortion, and childbirth. Neonatal tetanus is fatal with a mortality rate of 80–90%. However, in Asia, especially in China, Myanmar, Indonesia and India, the death rate due to neonatal tetanus is greatly reduced due to immunization coverage of pregnant woman with a protective dose of tetanus toxoid. Bhutan, Korea, the Maldives, Sri Lanka and Thailand have declared neonatal tetanus, elimination.

Pathogenesis

Under the suitable anaerobic conditions with low oxidation-reduction, potential spores of the Cl. tetani germinate and produce a potent neurotoxin (tetanospasmin) in the wounds. Once released it binds to the peripheral motor nerve terminal, enters the axon and is transported to the nerve cell body in the brainstem and spinal cord by retrograde intraneuronal transport. The toxin migrate across the synapse to presynaptic termina, where it blocks the release of glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Once the inhibitory action is diminished, the resting-fixing rate of locomotor neuron increases, producing rigidity. The length of the nerve travelled determines the time of ascent and explains why the disease manifests first in muscles supplied by the short cranial nerves.

Clinical Features

The incubation period ranges from 3 days to 4 weeks. However, it may be as short as one day or as long as months due to dormant spores in the wound. The prophylaxis against tetanus can also prolong the incubation period.

Generalized tetanus is characterized by lock-jaw or trismus due to spasm of masseter, which is the initial symptom and a dental surgeon is the first person often to be consulted.

Dysphagia, stiffness or pain in the neck, shoulder or back muscles appear concurrently. Marked rigidity interferes with the movement of chest and impairs cough and swallowing reflexes. Laryngeal spasms may lead to asphyxia. The involvement of various muscles produces rigid abdomen and stiff proximal limb muscles. Hands and feet are relatively spared and sustained contraction of facial muscles results in a grimace or sneer called as risus sardonicus. The contraction of muscles of the back produces an arched back called opisthotonus. The spasms occur repetitively or spontaneously or provoked by slight stimulation.

Local tetanus manifests as spasm of muscles near the wound and is uncommon. Cephalic tetanus characterized by trismus and facial palsy is rare one, and may occur after head injury or ear infection.

This disease, which has been reviewed in depth by Smith and Myall, is of significance to the dentist because of the acute trismus which may develop in these patients and simulate acute oral infection, trauma, temporomandibular dysfunction and even hysteria.

It should be differentiated from other inflammatory conditions of oral cavity, strychnine poisoning, drug-induced reactions, and hypocalcemic tetany.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to remove spores at the site of the wound, prevent toxin production, neutralize unbound toxins and prevent muscular spasms. Cardiopulmonary monitoring should be maintained continuously. Sedation, airway, and nutrition should be maintained. Antibiotics should be given to eradicate vegetative organisms or source of toxins. Penicillin 10–12 million units IV for 10 days, metronidazole 1 gm every 12 hours should be administered. Clindamycin or erythromycin is an alternative for penicillin allergic patients,

Antitoxin is injected to neutralize circulating toxin and unbound toxin.

Human tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) 3000–6000 units IM individual doses. Though the optimum dose is not known, a 500 unit dose is as effective as higher doses.

Syphilis (Lues)

Syphilis is a centuries-old infectious disease that has protean clinical features. The name was probably derived from a handsome and wealthy shepherd who was affected by the disease. It is said to have evolved from between 15,000 and 3,000 BC and transported to Asia by Portuguese sailors led by Vasco da Gama. It was an extremely common infection a few decades ago. Widespread use of antibiotics after World War II reduced the incidence of syphilis. However, within the past three decades there has been as astonishing upsurge in the incidence of the disease, much of it in teenagers. Its return is associated with the emerging HIV pandemic.

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a spirochete, and is characterized by episodes of active disease interrupted by the period of latency. This gram-positivea, motile, microaerophilic spirochete is pathogenic to humans, which may be best demonstrated by the dark field microscope, since it stains poorly except by silver impregnation. In 1998, the complete genetic sequence of T. pallidum was reported which might help in understanding the pathogenesis of syphilis.

The route of transmission of syphilis is usually by sexual contact, although there are examples of congenital syphilis via transmission from mother to child in utero.

Epidemiological studies demonstrate that sexually transmitted diseases including syphilis, and particularly genital ulcers associated with primary syphilis, are associated with an increased risk of HIV infection.

Acquired Syphilis

The acquired form of syphilis is contracted primarily as a venereal disease, after sexual intercourse with an infected partner, although persons, such as dentists, working on infected patients in a contagious stage, have innocently acquired it in many cases. The disease, if untreated, manifests three distinctive stages throughout its course, so that it is customary to speak of primary, secondary and tertiary lesion of acquired syphilis.

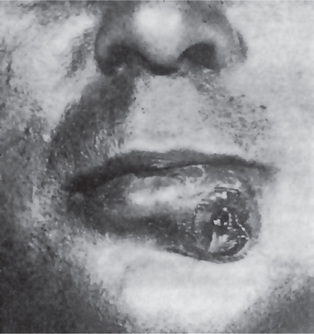

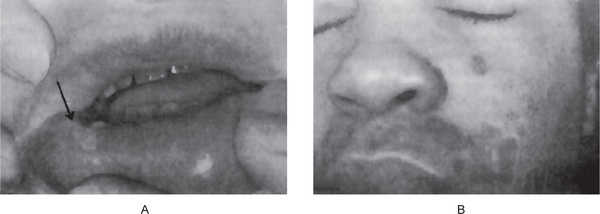

In the primary stage, a lesion known as chancre devel ops at the site of inoculation approximately 3–90 days after contact with the infection. Chancre is usually solitary but may be multiple at times. It most commonly occurs on the penile in the male and on the vulva or cervix in the female. About 95% of chancres occur on the genitalia, but they are also found in other areas. In recent years, there appears to have been an increase in the occurrence of extragenital syphilis as result of an increase in altered sexual activity and increased contact among infected male homosexuals. Of particular interest to the dentist are those lesions occurring on the lips, tongue, palate, gingiva, and tonsils. The chancre has been reported developing even at the site of a fresh extraction wound. The usual primary lesion is an elevated, ulcerated nodule showing local induration and producing regional lymphadenitis. Such a lesion on the lip may have a brownish, crusted appearance (Fig. 5-6). Very rarely, it appears vascular, mimicking a pyogenic granuloma.

The intraoral chancre is an ulcerated lesion covered by a grayish-white membrane, which may be painful because of secondary infection. The chancre abounds with spirochetes, easily demonstrable by dark field examination of a smear, and is highly infectious. The Treponema microdentium, which is found in many nonsyphilitic people, may be confused with T. pallidum on dark field examination. Therefore, lesions contaminated by saliva should not be diagnosed by dark field examination of the lesion, but by dark field examination of an affected regional lymph node. An enlarged lymph node is almost always found along the lymphatic draining of the area of the chancre.

The chancre appears microscopically as a superficial ulcer showing a rather intense inflammatory infiltrate. Plasma cells are particularly numerous. The microorganisms are present in the tissue and may be demonstrated by silver stain, although the diagnosis should not be established by this means but, rather, by any one of a variety of serologic tests. Of considerable importance is the fact that not every patient with a primary lesion exhibits a positive serologic reaction despite the presence of a spirochete. The chancre heals spontaneously in three weeks to two months.

The secondary or metastatic stage, usually commencing about six weeks after the primary lesion, is characterized by diffuse eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes. In contrast to the solitary lesion in the primary stage, lesions of the secondary stage are typically multiple. On the skin, the lesions often appear as macules or papules which are painless. The oral lesions, called ‘mucous patches,’ are usually multiple, painless, grayish-white plaques overlying an ulcerated surface (Fig. 5-7). They occur most frequently on the tongue, gingiva, or buccal mucosa. They are often ovoid or irregular in shape and are surrounded by an erythematous zone. Mucous patches are also highly infectious, since they contain vast numbers of microor ganisms. In the secondary stage the serologic reaction is always positive. The lesions of the secondary stage undergo sponta neous remission within a few weeks, but exacerbations may continue to occur for months or several years.

Figure 5-7 Secondary syphilis. (A) Mucous patch of lip in secondary syphilis. (B) Annular, circinate lesions of skin in secondary syphilis (Courtesy of Dr Edward V Zegarelli).

Secondary syphilis can be present as an explosive and widespread form known as lues maligna, characterized by fever, headache, and muscle pain followed by necrotic ulcerations involving the face and the scalp. This form is reported in patients with a compromised immune system, particularly acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

After second-stage patients are free from lesions and symptoms, they enter the latent stage which may last for 1–30 years till the next stage, tertiary syphilis, develops. Patients demonstrate reactive serological test for syphilis.

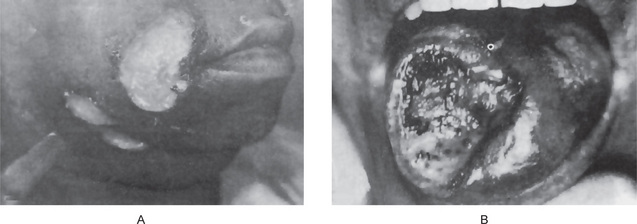

Tertiary syphilis, also called late syphilis, does not usually appear for several years and involves chiefly the cardiovascular system, the central nervous system, and certain other tissues and organs. Late syphilis is noninfectious. Classic lesion of the terti ary syphilis is gumma. It is the result of hypersensitivity reac tion between the host and the treponemes or their breakdown products. Gumma occurs most frequently in the skin and mucous membranes, liver, testes, and bone. It consists of a focal, granulomatous inflammatory process with central necrosis. The lesion may vary in size from a millimeter or less to several centimeters in diameter.

The intraoral gumma most commonly involves the tongue and palate. In either situation the lesion appears as a firm nodular mass in the tissue, which may subsequently ulcerate, to form a deep painless ulcer. Lesions of the palate cause perforation by sloughing of the necrotic mass of tissue. (Fig. 5-8). Such an occurrence frequently follows vigorous antibiotic therapy, a Herxheimer reaction.

Figure 5-8 Tertiary syphilis. (A) Gumma of skin. (B) Gumma of tongue (Courtesy of Dr Charles A Waldron).

Meyer and Shklar have reported oral manifestations in 81 cases of acquired syphilis, and have stressed that tertiary lesions are far more common than lesions in either primary or second ary syphilis. However this ratio is probably changing. Atrophic or interstitial glossitis is the most characteristic and important lesion of syphilis and is due to endarteritis obliterans.

In syphilitic glossitis, the surface of the tongue gets broken up by fissures due to atrophy and fibrosis of tongue musculature; and hyperkeratosis frequently follows. Syphilitic glossitis is found almost exclusively in males. The predilection for syphilitic glossitis to undergo carcinomatous transformation has been recognized for many years. The inci dence of such malignant transformation has been as high as 30% in various reported series. However, in the series of Meyer and Shklar, the development of epidermoid carcinoma in luetic glossitis occurred in only 19% of the cases. In a sepa rate study, the same authors reported that only 7.5% of the patients in a series of 210 cases of carcinoma of the tongue had a past history of syphilis. The prominent apparent decrease in the relationship between syphilis and lingual carcinoma was suggested to be related to the early and intensive treatment of the disease with antibiotics since 1940.

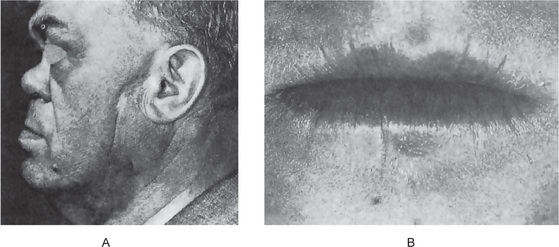

Congenital (Prenatal) Syphilis

Congenital syphilis is transmitted to the offspring only by an infected mother and is not inherited. Though congenital syphilis is totally preventable, it still continues to be a major problem in many countries. It is recognized that if treatment with antibiotics begins in infected pregnant women before their fourth month of pregnancy, approximately 95% of the offspring of these mothers will be free of the disease. It is to be noted that not all infected pregnant women deliver children with congenital syphilis. One-third of pregnancies result in abortion or stillbirth; one-third deliver normal children and the rest deliver children with congenital syphilis. Persons with congenital syphilis manifest a great variety of lesions, including frontal bossae (found in 87% of a series of 271 patients with congenital syphilis reported by Fiumaraand Lessell), short maxilla (in 84%), high palatal arch (in 76%). saddle nose(in 73%), mulberry molars (in 70%); Higoumenakis sign or irregular thickening of the sternoclavicular portion of the clavicle (in 39%), relative protuberance of mandible (in 26%), rhagades (in 7%), and saber shin (in 4%) (Fig. 5-9). Reportedly pathognomonic of the disease is the occurrence of Hutchinson’s triad: hypoplasia of the incisor and molar teeth, eighth nerve deafness, and interstitial keratitis (q.v.).

Figure 5-9 Congenital syphilis. Saddle nose (A) and rhagades or radiating fissures (B) of congenital syphilis (Courtesy of Dr Wilbur C Moorman and Dr Robert J Gorlin).

In the above reported series, 75% of the persons with congenital syphilis had one or more of the components of Hutchinson’s triad. It is unusual; however, for all features of this triad to occur simultaneously in the same person.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Wassermann test and Hinton test (based on flocculation) were considered to be effective tests for the diagnosis of syphilis, but the disadvantage is false positive results. The diagnosis can be made by examining the exudates of the active lesion under a dark field microscope for spirochaetes. Care should be taken to eliminate salivary contamination since false positive results are possible due the presence of T. microdentium, T. macrodentium, and mucosum. Specific and highly sensitive serological tests are fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption and T. pallidum. hemaggluti-nation assays.

Penicillin is the drug of choice. Erythromycin or tetracycline is used if the patient is allergic to penicillin. Surgical correction of the facial defects gives good esthetic results.

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is primarily a venereal disease affecting the male and female genitourinary tract and is transmitted by sexual intercourse. It is an infection of epithelium and commonly manifests as cervicitis, urethritis, prostatitis, and conjunctivi tis. It is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae a gram-negative, nonmotile, nonspore forming organism that grows in pairs (diplococci). The common age group affected is 15–29 years with about half in the adolescent age.

It is a significant cause of morbidity in developing countries and may play a role in the transmission of HIV. In India gonorrhea is more widely prevalent than syphilis and 80% of infected women are reported to be asymptomatic carriers. It predominantly affects young persons.

The incidence of gonorrhea has increased in developing countries, but the exact incidence is difficult to ascertain because of limited surveillance and variable diagnostic criteria. It is transmitted from males to females and vice versa. Oropharyngeal gonorrhea occurs in 20% of women who practice fellatio with infected partners. The incubation period is one to five days.

Clinical Features

Infection in males results in acute urethritis, dysuria and urethral discharge of a purulent nature. Some patients may have mucoid discharge. It may lead to epididymitis, chronic prostatitis, balanitis and posterior urethritis.

In females, it manifests as cervicitis with candidal or trichomonal vaginitis. Mostly they are symptomatic. Carrier symptoms include vaginal discharge, discomfort, and dysuria. It may affect the rectum, oropharynx, and the eye.

Oral Manifestations

Extragenital gonorrheal infection of oral cavity is being seen with increasing frequency, especially among but not confined to homosexuals, and occurs as a result of oral-genital contact or inoculation through infected hands. Transmission by fomites is rare. Schmidt and coworkers have reviewed the literature on gonococcal stomatitis and have pointed out the clinical similarity between the oral lesions of this disease and the oral lesions of erythema multiforme, erosive or bullous lichen planus, and herpetic stomati tis. Chue has also reviewed this disease, describing the various oral lesions in detail. The lips may develop acute painful ulceration, limiting motion; the gingiva may become erythe-matous, with or without necrosis; and the tongue may present red, dry ulcerations or become glazed and swollen with painful erosions, with similar lesions on the buccal mucosa and palate.

Gonococcal pharyngitis and tonsillitis are also well recognized lesions. These appear as vesicles or ulcers with a gray or white pseudomembrane. Oral lesions are commonly accompanied by fever and regional lymphadenopathy. Finally, gonococcal parotitis, presumably a result of an ascending infection from the duct to the gland, has been reported on numerous occasions.

Complications

Epididymitis, salpingitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and bartholinitis are the usual copmlications. Gonococcal bacteremia leads to dermatitis and arthritis. Joint involvement leads to arthritis or arthralgia with effusion. Patients with gonorrhea are at risk for additional sexually transmitted diseases, most commonly Chlamydia trachomatis.

Granuloma Inguinale (Granuloma venereum, donovanosis)

Granuloma inguinale was first recognized in India by McLeod in 1882. This disease is a progressive, chronic, infectious, granulomatous disease caused by microorganisms, probably bacilli, formerly designated as Donovania granulomatis and popularly called Donovan bodies, but now carrying the name Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. Their taxonomic status is uncertain. It is considered to be a venereal disease, but is only mildly contagious. Care should be exercised not to confuse granuloma inguinale with lymphogranuloma venereum, a venereal disease that is caused by strains of Chlamydia trachomatis, once designated as viruses but now morphologi cally classified as bacteria. The oral cavity is not notably involved in this latter disease.

Clinical Features

The disease is most prevalent in the tropical zones, but is found in the southern portion of the United States. It chiefly affects adult blacks of either gender, but may occur in any race. The primary lesions of granuloma inguinale appear on the external genitalia, anus, and in the inguinal region. They are manifested as papules or nodules, which ulcerate to form clean, granular lesions with rolled margins and which show a tendency for peripheral enlarge ment. Occasionally, verrucous, necrotic, or cicatricial lesions have been reported. Satellite lesions often arise through lymphatic extension. Inguinal ulceration is commonly secondary to the genital lesions and arises initially as a fluctu ant swelling known as a pseudobubo.

Extragenital lesions also may occur on the oral mucous membranes, usually through autoinoculation rather than as a primary infection, as well as in the pharynx, esophagus, and larynx. Finally, metastatic spread to bones and soft subcutaneous tissues has been, reported. Two separate investigators have reported an incidence of extragenital lesions of granu loma inguinale to be 6% and 1.5%, respectively.

Oral Manifestations

Oral lesions appear to be the most common extragenital form of granuloma inguinale. Ferro and Richter, who described additional cases, have reviewed the reported cases. The lesions of the oral cavity are usually secondary to active genital lesions and appear in a variable period of time after the primary lesion, frequently months to several years later. The definitive diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of Donovan bodies in tissue from the lesions. Lesions may occur in any oral location such as the lips, buccal mucosa, or palate, or they may diffusely involve the mucosal surfaces. The varied clinical appearance of the lesions is the basis for their classification into one of three types: ulcerative, exuberant, and cicatricial. Thus there may be painful ulcerated lesions, sometimes bleeding, suggestive but not pathognomonic of the disease. Or, in other instances, the lesions may appear as proliferative granular masses, with an intact epithelial covering. The mucous membrane generally may be inflamed and edematous. Cicatrization is one of the most characteristic of the oral manifestations of granuloma inguinale. Fibrous scar formation may become extensive, and if present in areas such as the cheek or lip, may also limit mouth opening as to necessitate surgical relief.

Histologic Features

The microscopic pattern of the various forms of granuloma inguinale is one of granulation tissue with infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and plasma cells. There is usually a marked overlying pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia. Pathognomonic of the disease is the presence of large mononuclear phagocytes, each containing intracytoplasmic cysts within which are found the Donovan bodies. These bodies are tiny, elongated, basophilic and argyrophilic rods and are present in profuse numbers within the macrophages. Differential diagnoses of oral lesions include all granulomatous lesions of the oral cavity. Where genital lesions are also present, other sexually transmitted disease must be considered in differential diagnosis.

Treatment

Tetracycline, chloramphenicol, streptomycin garamycin, and cotrimoxazole are effective in the treatment of this disease. Complete healing usually occurs within two to three weeks. It has been noted that, after treatment, improvement of the genital lesions is usually accompanied by improvement of the extragenital oral lesion; conversely, exac-erbation of genital lesions usually results in worsening of the oral condition.

Rhinoscleroma (Scleroma)

Rhinoscleroma is a chronic, slowly progressive, localized infectious, granulomatous disease caused by the bacillus Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis (Klebsiella type 3), a gram-negative non-motile bacillus. This etiologic agent has been discussed in detail by Hoffman. This disease has worldwide distribution and is endemic in countries such as China, India, Indonesia, Africa, South and Central America, and in central parts of Eastern Europe. The mode of transmission is through infected nasal exudate.

The granulomatous, nodular lesions that occur in rhinoscleroma are found chiefly in the upper respiratory tract, often originating in the nose, but involvement of the lacrimal glands, orbit, skin, paranasal sinuses, and intracranial invasion have also been described. The proliferative nasal masses may produce the configuration known as the ‘Hebra nose,’ which is typical of this disease.

Oral lesions appearing as proliferative granulomas are also known to occur. In addition, impairment of the sensation of taste, anesthesia of the soft palate and enlargement of the uvula and upper lip are described. Three cases of rhinoscleroma seen in a maxillofacial practice in Nigeria have been discussed by Edwards and associates, who have included an extensive bibliography of the disease.

Treatment of this disease consists of administration of tetracycline or ciprofloxacin. If left untreated the outcome will be fatal.

Noma (Cancrum oris, gangrenous stomatitis)