Communication in healthcare practice

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe basic interpersonal communication principles

describe basic interpersonal communication principles

understand the importance of person-centred communication

understand the importance of person-centred communication

identify the key skills of active listening to facilitate effective communication

identify the key skills of active listening to facilitate effective communication

identify important ethical communication issues

identify important ethical communication issues

understand the process of cultural safety and intercultural communication

understand the process of cultural safety and intercultural communication

understand the role of communication within a multidisciplinary team

understand the role of communication within a multidisciplinary team

identify communication issues between health professionals such as horizontal bullying

identify communication issues between health professionals such as horizontal bullying

understand the role of health professionals in health education and client advocacy.

understand the role of health professionals in health education and client advocacy.

Introduction

Communication is vital in all parts of healthcare interactions, but none more so than in the health professional–client relationship where it is a key requirement for safe and effective practice. Being able to communicate effectively will assist you in working together with the client, family and carers, supporting them in shared responsibility and decision making about their health and lifestyle. Effective communication is not just about being able to talk clearly; it is also about listening and understanding what has been communicated. Listening is critical when working with other people, and a health professional who can listen well will find people more willing to talk openly and honestly about their health issues.

Health psychologists are interested in knowing how health professionals communicate in practice and what can be done to improve this in order to enhance the relationship between all parties involved. This chapter will examine the fundamental aspects of communication in healthcare practice, focusing on the challenges and variables health professionals need to consider when working with other people in care delivery. In the next chapter the partnerships that can be developed from effective communication are examined.

Person-centred communication

Person-centred communication (PCC) is one of the most important dimensions of health professional–client communication. In the past, clients have often been seen as a ‘diagnosis’ (‘the broken leg in bed 1’) with a focus on assessment and symptom management. Lack of attention to other factors such as the social, psychological and behavioural aspects of the person's life has left the client without a context for their health issue and often feeling ‘unheard’. Research in a number of clinical settings has demonstrated that people who are provided client-centred care experience better health outcomes (Di Blasi et al 2001) and greater client satisfaction (Venetis et al 2009). Research in the United States and the United Kingdom also demonstrates a strong correlation between client satisfaction and the interpersonal skills of the health professional (Boudreaux et al 2004, Toma et al 2009), making it even more vital for health professionals to develop effective communication skills and behaviours in their daily practice. So with this in mind, what is PCC?

PCC is a collection of skills used by health professionals that are respectful and responsive to the individual's needs, values and preferences (Bertakis et al 2009, Levinson 2011). It is not always easy to define the exact level or type of communication required for each client because the variation in people's needs and experiences are unique and different for each individual. What is important is to remember that PCC is not limited to verbal communication but embraces all forms of communication that can affect client care such as written and non-verbal elements. Success is dependent on both parties (the client and the health professional) being able to speak, question and listen. It is a two-way process in which the language and meaning in the message is correctly understood by both, enabling an accurate exchange of information, thus enabling the client to participate in their own care (The Joint Commission 2010).

Skills of communication

In providing appropriate healthcare it is important for all health professionals to consider their own communication style by examining the skills they already possess and those they need to develop in order to communicate effectively with clients, families and other health/service providers. It also helps to have a personal awareness of the likely barriers of communication in practice because inadequate communication can cause distress for clients and their families. Confusion, uncertainty and being unsure of what's being said can leave clients feeling unclear of their illness, diagnosis, treatment or management plan.

The majority of communication textbooks focus on the process of communication or identify groups of different behaviours and qualities that are collectively known as communication skills. The essence of good communication lies within the skills required to deliver and receive the message effectively and include such skills as active listening, reflection, empathy, body language and vocal style. Some authors refer to these as attending behaviours (Ivey et al 2010) while others call them micro skills (Egan 2010). The key element of good communication is to extract the unique experiences and preferences of the client and respond appropriately and effectively.

Facilitating the interaction

Ways of encouraging the person to speak about their experience may vary. Ivey et al (2010) write about the importance of ‘open invitations to talk’ or open-ended questions in encouraging communication in comparison with closed questions. Open-ended questions provide emotional space and often encourage longer responses: ‘Tell me what it’s been like to have rheumatoid arthritis’; ‘Could you tell me …?’; ‘I'm wondering …'; ‘Some people have experienced … do you?’. Closed questions are often effective when requiring factual content and shorter responses: ‘How many years have you had rheumatoid arthritis?’; ‘What is your date of birth?’; ‘Do you have a regular doctor?’ Both have a place in healthcare but sometimes closed questions get in the way of two-way interaction and open-ended questions don't always yield clear information (Balzer Riley 2011). Of course, the response will also depend on the individual. It is not a satisfactory experience for the client to be asked repeated closed questions, with no other comments. There is also the danger that continued open-ended questions yield little concrete information and annoy the client. A variety of different types of questions and comments will often not only yield more in-depth responses, it will also help build rapport and encourages the client to be more cooperative (Balzer Riley 2011). Practise will help in developing these skills. Reflecting on your everyday communication, it may be surprising to find how often each of these kinds of questions are already used. The following are micro skills that facilitate effective communication:

Minimal encouragers

Minimal encouragers can indicate to the individual that the helper understands what they are saying. These can be non-verbal, such as the occasional eye contact, leaning forward or nodding the head, or verbal, such as: ‘Oh?’; ‘So?’; ‘Then?’; ‘And?’; ‘Uh-huh’, or a restatement of the same words spoken by the other person: ‘So you feel that the treatment was a waste of time …’. Sometimes silence is very effective, showing the client that you are listening and allowing the person to gather their thoughts and say more about a particular topic (Blonna et al 2011). It is useful to observe how other people show their interest in what someone is saying to them and how different behaviours encourage or discourage a conversation continuing. The important skill is to be aware of how the interaction is flowing and how the client is responding to what the health professional is saying. If the client seems anxious or annoyed, or showing other feelings, it is better to explore their feelings: ‘You seem a bit anxious. Are you happy to continue with the interview?’ This demonstrates concern and also helps build rapport. There are a variety of ways of showing clients that you understand what is being said and that also help you organise your own thoughts.

Empathy

An important aspect of communication is the use of empathy whereby the health professional lets the person know he or she is sensing the person's emotions. Rogers (1961) would consider it a quality inherent in the individual – the ability to feel with the other person in their situation. ‘Reflection of feeling can be taught as a cognitive skill … sensitive empathy, with all its intensity and personal involvement, cannot be so taught’ (Rogers 1987). It is true that there is a difference between a learned skill and an inherent quality and it is important to differentiate between them. A naturally empathic person will probably find that they gently reflect or ‘mirror’ the person's feelings back to them: ‘You seem really stressed at the moment’.

Reflection

As a beginning health professional, it is often helpful to practise reflection of feelings, that is, reflecting back the person's feelings and listening and responding to the emotions being expressed, not just the content of what they have said (Blonna et al 2011). The actual words used will vary, but it may simply mean repeating back what the other person has said such as, ‘So you were at that hospital for a week?’. Or, it might be more supportive to the client to say, ‘I get the feeling it was quite a frightening time for you’. Of course, while this can be supportive to clients, some may find it threatening because they might not wish to divulge their feelings. Another useful technique is paraphrasing. At intervals during the interaction it can help to sum up what has been said so far: ‘So you have had joint and muscle pain and you have had problems with your balance for 20 years.’

Summarising

At the end of the interview summarising can also be helpful. This is similar to paraphrasing but sums up the whole conversation. ‘So, if I've got it right, what you have been telling me is …'. Sometimes this can help clients review what they have told you and help health professionals check they have understood what the client said (Balzer Riley 2011). In a busy clinical environment summarising may take additional time, but it can frequently help improve your understanding of a situation and a client may appreciate it and feel their health issues have been understood accurately. It has been the writer's experience that international healthcare students, with English as a second language, often find summarising helpful because it provides a clarification tool to use when they aren't clear what the client has said.

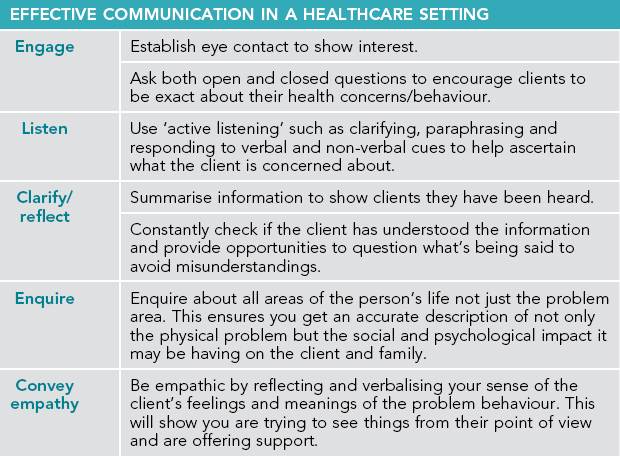

In conclusion, some common identified skills for effective communication in a healthcare setting between client and provider are noted by Maguire and Pitceathly (2002) in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION IN A HEALTHCARE SETTING

Adapted from Maguire P, Pitceathly C 2002 Key communication skills and how to acquire them. British Medical Journal Vol 325 No 7366, p 697–700

The importance of language

Words alone do not convey meaning or understanding. It is important to remember that a layperson may have less knowledge about basic anatomy and physiology than you might assume. Medical terminology that has become part of a health professional's everyday language is useless jargon if not understood by the listener. Therefore health professionals cannot assume that everyone with whom they engage will understand their meaning.

Language and culture

Language is a key part of a person's culture and helps them identify who they are as an individual and in society. Often a person's culture will influence the way they see and engage with the world, so it is useful for health professionals to reflect on their own culture and try to understand it in the context of their practice and communication skills. As culture is such a complex concept it should not be reduced to a particular behaviour or attribute in one particular population group but considered in light of all available information, including thoughts, beliefs, attitudes, behaviour, background, heritage and spirituality. As early as the 1900s, linguists and anthropologists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf proposed that words and language are strongly influenced by culture (Otto 2006).

Colloquial language or slang words and euphemisms may be used by people who are too embarrassed to speak about personal matters. Unless familiar with the terminology it may appear to the health professional that the client is speaking a whole new language. For instance, an elderly lady may ask to ‘spend a penny’ to describe her need to urinate or a child may say they have a ‘tummy bug’ to describe a recent virus they are recovering from. In some cultures there may be several words within the language that can be used to describe one concept, whereas in other languages the existence of even one word may not be present. Ultimately, what means one thing to one person may mean something entirely different to somebody else so it is up to the health professional to avoid language that can be misleading or ambiguous by clarifying all medical terminology. If they are uncertain about what is being said, health professionals should ask the client to explain. This ensures all parties have achieved a clear understanding.

Intercultural communication and cultural safety

There are three key elements to achieving cultural safety in healthcare practice: cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity and cultural safety (see Table 8.2). These concepts, though related, should be understood in their own right to ensure culturally safe communication with others (Eckermann et al 2009).

Table 8.2

KEY ELEMENTS TO ACHIEVING CULTURAL SAFETY IN HEALTHCARE PRACTICE

| Cultural awareness | Cultural sensitivity | Cultural safety |

| A beginning step towards understanding there is difference. Many people undergo courses designed to sensitise them to formal ritual and practice rather than the emotional, social, economic and political context in which people exist. | Alerts health professionals to the legitimacy of difference and begins a process of self-reflection on the powerful influences from their own life experiences that may impact on their interaction with others. | Achieved when the client perceives their healthcare was delivered in a manner that respected and preserved their cultural integrity. |

Ramsden IM: Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Unpublished PhD thesis, 2002, Victoria University of Wellington, available at www.culturalsafety.massey.ac.nz, 19 February 2008.

Strongly linked with cultural safety is the process of intercultural communication. Kiesling and Bratt Paulson (2004) define this as the ability to utilise a range of tools and skills to enhance the communication process with people who speak languages other than the dominant local language. Though English is the official language of Australia and New Zealand, it is not a first language for a significant number of Indigenous Australians, M ori or other citizens. Australia and New Zealand have a growing multicultural population with a huge diversity of first, second and subsequent generations who each may have distinctive cultural and linguistic needs, especially if they are from non-English-speaking backgrounds. Intercultural communication is an important aspect of maintaining cultural safety and if not addressed can contribute to a breakdown in communication and ultimately have a significant impact upon the effectiveness of healthcare. For instance, Australian research has identified ineffective communication as one of the main factors leading to poor health outcomes in Indigenous Australians (Cass et al 2002, Coulehan et al 2005, Lawrence et al 2009). To provide culturally safe clinical services, health professionals need to be aware of differences in intercultural communication and be able to identify factors that impede or enable communication in health service delivery, particularly for those living in rural and remote areas.

ori or other citizens. Australia and New Zealand have a growing multicultural population with a huge diversity of first, second and subsequent generations who each may have distinctive cultural and linguistic needs, especially if they are from non-English-speaking backgrounds. Intercultural communication is an important aspect of maintaining cultural safety and if not addressed can contribute to a breakdown in communication and ultimately have a significant impact upon the effectiveness of healthcare. For instance, Australian research has identified ineffective communication as one of the main factors leading to poor health outcomes in Indigenous Australians (Cass et al 2002, Coulehan et al 2005, Lawrence et al 2009). To provide culturally safe clinical services, health professionals need to be aware of differences in intercultural communication and be able to identify factors that impede or enable communication in health service delivery, particularly for those living in rural and remote areas.

Some areas to consider when engaging with people from culturally diverse backgrounds are as follows (ACT Health 2012):

Speak clearly and simply without being simplistic or patronising.

Speak clearly and simply without being simplistic or patronising.

Place yourself in the client's situation and think how you would like to be treated.

Place yourself in the client's situation and think how you would like to be treated.

Clarify meaning: both yours and others.

Clarify meaning: both yours and others.

Be aware of your own non-verbal behaviour and the way you interpret that of others.

Be aware of your own non-verbal behaviour and the way you interpret that of others.

Monitor your own style and the way you respond to difference.

Monitor your own style and the way you respond to difference.

Relate to others as individuals, recognising similarities rather than only differences.

Relate to others as individuals, recognising similarities rather than only differences.

Ensure you understand your clients' living arrangements, relationships and accessibility to health services.

Ensure you understand your clients' living arrangements, relationships and accessibility to health services.

Remember, it is a health professional's responsibility to recognise the unique differences in people. Cultural safety may be different for each person. Maintain cultural awareness and sensitivity to the client's needs and be willing to engage in dialogue to enhance culturally safe communication. Most health services now offer the use of interpreters and either Aboriginal liaison officers or M ori health liaison officers, so recognise when this would be beneficial to the communication process.

ori health liaison officers, so recognise when this would be beneficial to the communication process.

The health professional–client relationship

In identifying the skills needed for effective communication, it is easy to see them as mere lists made up of concrete, discrete behavioural actions without considering the importance of relationship development and the connection needed between clients and health professionals. The importance of caring and humanity is emphasised by Chochinov (2007) when he cites a seminal paper by Francis Peabody:

One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

(1927 cited in Chochinov 2007 p 187)

Similarly, Jean Watson, a pioneer in developing ‘caring theory’, identified several essential elements originally known as ‘carative factors’ but recently redefined as ‘caritas processes’ (Watson 2008). These elements support factors such as commitment, trust and continuity that are central to caring practice, communication and the healthcare relationship. Through the helping relationship, health professionals and clients may share a sense of two individuals working together – to have a sense of shared humanity that is essential to the spiritual, psychological and humanistic dimensions of the relationship (Stein-Parbury 2009). Although clinical skills and knowledge are very important in being a safe and competent health professional, it must never be forgotten that the tasks and procedures are being implemented on real people with real feelings of pain, fear and a wide range of other emotions and sensations. To be able to enter into their experiences is not simply a right for health professionals but a privilege that clients have given through their consent and trust.

Interpersonal relationships, ethics and communication

Interpersonal relationships can be both personal and professional, with interpersonal interactions being central to both (Balzer Riley 2011). Personal relationships may include friendships, intimate or romantic relationships, whereas a health professional–client relationship, though therapeutic, is a professional relationship established to meet the needs of the client. What, then, is the best way to relate to clients? How do they want health professionals to relate to them? You can begin by being sensitive to how a client behaves in interactions and modify responses in line with this. Sitting in different health professionals' waiting rooms you may observe the approaches of various receptionists to clients. Some vary their style depending on the client. They may address them using their first name or title; they know their clients and how to communicate with them. Others don't vary in their approach, always using the first name or a colloquial term such as ‘darl’ and it is interesting to see how some clients are quite relaxed about this, while others visibly bristle. Being an effective communicator means trying to ‘read’ clients and how they respond to what you say and do (Balzer Riley 2011). Of course, the task will often dictate the interaction; you might be assessing the individual's health status, taking a blood specimen or consulting them about their dietary needs, while at the same time engaging in a conversation about the weather or their interests outside the healthcare situation. Conversation may act as a means of lessening the client's (and sometimes the health professional's) anxiety or generally defusing the tension of a situation. Again, the focus should always be on the client and what their needs are.

Ethical behaviour is essential for delivering high-quality healthcare. As a health professional there are explicit ethical obligations related to communication that are fundamental to developing and maintaining a professional relationship (Duncan 2009). These can include informed consent, confidentiality and conflict to name a few. Each brings with it fresh challenges the health professional may face on a daily basis. Let's look at three common ethical issues of communication in more detail. These are power imbalance, professional boundaries and self-disclosure.

Power imbalance

When health professionals are consulted it is more often than not because they are seen as an expert in a particular area and the client is seeking help from someone who they deem has the skill and knowledge to help them. Though not necessarily perceived by the health professional, having the skills, knowledge, influence and authority that the client requires inadvertently leads to an inherent power disequilibrium between the two parties. The practitioner is in a position of power, while the client may feel vulnerable.

It is important for the client to feel comfortable in confiding their concerns or health issues with the health professional without feeling they are relinquishing their own responsibility and control over any decisions concerning them. A health professional who provides information encourages the client to be an active partner in the therapeutic alliance. Using micro skills during communication will go some way to alleviating this power imbalance, whereas a misuse of this power is considered abuse.

Professional boundaries

In today's healthcare environment, roles are much less differentiated than in previous years and health workers might now be more open and reveal more of their own personalities than before (Nelson & Gordon 2006). For example, in many public hospitals, doctors do not wear white coats; health professionals might wear more casual-looking clothes rather than formal white or green uniforms so a client might be confused about which role the person assisting them has. At a time when roles are more blurred and many express the need to be treated as equals, developing a relationship with the appropriate professional boundaries can be an uncertain road to navigate.

Ultimately, the relationships we form with clients differ from those we form with friends and family. At times it may be appropriate to be informal and engage in social conversation with some clients, but it is important to first be sensitive to the individual you are caring for and be prepared to work at establishing a helping relationship. For example, it might be preferable to address someone by their title and surname until it is established that the person is comfortable to be called by their first name.

While some boundaries are very clear and inviolable (e.g. physical, verbal or sexual abuse) others can be blurred (e.g. when the client asks about your marital status or invites you on a date), and require the health professional to be aware of when the professional relationship may be crossing the boundary or moving into a ‘grey’ area. This requires self-reflection, and the willingness to discuss the relationship dilemma with a manager or supervisor who will be able to consider the context of the relationship and offer advice. Remember it is the health professional's responsibility at all times to establish and maintain a professional relationship by setting clear boundaries regardless of how the client has behaved.

One particular ‘grey’ area to consider is the possibility of a dual relationship, which can become even more apparent in small communities, such as in rural and remote areas. Due to the population size, it may be that the health professional has both a personal and a professional relationship with the client; that is, they are a close friend as well as the practitioner caring for them. It is therefore of paramount importance that all aspects of the relationship such as role and boundary shifts are clarified by articulating what your role and responsibilities will include while working with the person as a health professional. Communicating in such a transparent manner helps protect client confidentiality and ensure the client's needs are a priority.

Self-disclosure

There are invisible boundaries that all individuals erect around themselves, depending on the situation. This impacts on who we choose to disclose personal information to. Self-disclosure (revealing personal information about our lives to others) is generally accepted as a valuable tool in personal relationships and can be just as valuable in a professional relationship if used appropriately and in moderation. While health professional to client self-disclosure is unacceptable in most contexts, it may be acceptable and appropriate in special circumstances. For example, a mother who has recently experienced a 28-week gestation pregnancy loss and is struggling to grieve for the child may find it useful to hear about what proved helpful in the grieving process from a health professional who has gone through a similar experience. This kind of select and limited disclosure may be judged helpful in meeting the therapeutic needs of the client.

It is never acceptable for a health professional to disclose information that is self-serving or intimate. To avoid blurring boundaries, the required skill is to know what is considered suitable personal information to discuss and to ask the question ‘Is it appropriate to do so?’, while remaining within the scope of the professional relationship. Therefore it is the responsibility of health professionals to direct their attention to their clients' needs as being first and foremost, rather than their own. In reflecting on this you can ask yourself the question: ‘Whose needs are being served by my self-disclosure?’

Other influences on communication in healthcare settings

Individual health professional and client interactions may not always be successful. Some health professionals, as well as clients, are not easy to work with and may behave in unreasonable ways, be uncooperative, or be physically or verbally aggressive at times. Particularly, but not just in large healthcare organisations, status can be an issue. Some health professionals within the service may be considered, or consider themselves, to have higher status than others. Furthermore, administrators you may not know or ever communicate with, make decisions affecting the work situation. This may give the feeling of a narrow span of control, which may in turn lead to a high level of informal communication or gossip between staff such as, ‘Did you hear about …?’

The diverse educational backgrounds of professionals and staff in a healthcare service may contribute to communication problems. Various disciplines may have jargon or specialised language that other health professionals (or clients) may not understand. Different staff will have varying qualifications, which can make for rivalry between the different disciplines. An individual may be an excellent health professional but have little or no administrative skills but, because of their seniority, may have leadership responsibilities. Decisions they make may not always be the right or popular ones.

A growing concern emerging in healthcare, and particularly in the nursing literature, is the issue of horizontal violence or bullying, sometimes called lateral violence. Though horizontal violence takes many forms, one of its common characteristics includes ‘overt and covert non physical hostility’ (Roy 2007). Such communication from one or more people towards an individual can be disrespectful, offensive or undermining, leading to feelings of helplessness, humiliation and being harassed or bullied. One group highlighted as frequently, but not exclusively, exposed to horizontal violence are new nursing graduates (Roy 2007), though the problem can manifest between any team members irrespective of gender, age, experience or discipline.

In the light of this issue and the others above, it is important to consider ways of dealing with challenging situations or trying to avoid them happening, and to promote better communication between all staff levels. Various ways of sharing decision making and promoting consultation are to be encouraged within organisations and teams. This should include ensuring there is provision for down–up as well as up–down communication between all areas of the hierarchy through regular meetings and social contact. Another way of enhancing staff-to-staff communication and providing for professional growth and development is to encourage and provide clinical supervision, support and mentoring. And finally, ideally, any organisation should also have a good mix of staff from a variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

Client education

Although much of a health professional's time centres on treatment, an important role in working with clients is that of providing information and health promotion to individuals and groups. Apart from professionals who work full time in health promotion, many health professionals may think their role in client education is limited to handing out a booklet or showing a DVD to a client before they are discharged. However, with increasingly short lengths of stay in hospital and people being more knowledgeable about health matters, it is an area of increasing importance in clinical practice and research. In spite of this, there is frequently little time allowed for this significant aspect of care (Leino-Kilpi et al 2005).

Various professional bodies emphasise the importance of educating clients about their health status. For example, the Australian Physiotherapy Council (APC) includes in its standards the importance of providing education to clients (APC 2008). For Australian nurses, client education is a core competency (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC) 2006). Education is important in helping clients gain knowledge and, therefore, empowerment in managing their problem (Chang & Kelly 2007). It will depend on whether a health professional is working in the community or in a hospital setting as to the approach taken. A healthcare worker in the community may work with individuals, groups, families or carers implementing planned and programmed education sessions, whereas in the hospital setting you are more likely to work with the individual client and their particular needs.

So what are the communication skills needed for successful client education? According to Chang and Kelly (2007), any education must be based on sound approaches with proper understanding of clients' requirements and ability and motivation to learn, including aspects of culture and literacy. You can first find out what the client already knows by asking questions such as, ‘What do you think is going on?’ and then move towards questions that address the gaps. It is useful to predict questions the client may ask or information they might wish to know. Questions such as, ‘What will happen to me?’, ‘Will it be painful?’ and ‘When will I know the results?’ are common to many areas in healthcare practice. Effective education takes time and patience on the part of health professionals. The skills of active listening once again become extremely important. The client may be anxious or fearful and unable to process any information being said, therefore the health professional will need to identify the cues to respond appropriately, whether it is a matter of reassuring the person's uncertainties or expanding their knowledge regarding the health issue. In such circumstances it can be helpful to also provide written information for the client. In other words, once the cognitive, behavioural and emotional needs of the client have been addressed and understanding is clear to all involved parties, then you can feel confident the client has learnt something. In this context not only has education occurred but also PCC.

Advocacy

The healthcare literature defines advocacy as protecting and promoting the rights of people who may be vulnerable and incapable of protecting their own interests, and though this is true it can also be argued that it has several dimensions from legal and ethical obligations to philosophical debates about the foundations of healthcare practice. For instance, it may be as straightforward as a professional representing a client by speaking to a senior health professional on behalf of a client who is too anxious to ask questions or unable to speak for themselves (Benner et al 2010). However, it may also mean different things, from counsellor to ‘whistleblower’ (a person who publicly exposes unsafe or illegal practices).

For the purpose of this chapter, we are interested in the more specific qualities and skills of being an advocate that enable health professionals to assure people in their care that they are the recipient of quality care, whether for the purpose of changing policy and legislation, accessing relevant health and social care information or supporting a person's decision making (Health Consumers Queensland 2010).

Various codes of conduct and professional standards underline the importance of advocacy when working with clients (Baldwin 2003). In her analysis of nursing literature Baldwin (2003) found that advocacy had three qualities: a therapeutic health professional–client relationship; the promotion and protection of the client's involvement in making decisions and informed consent; and being a mediator between clients and relatives or friends and healthcare providers, with communication being central to each. Therefore, for a health professional to act as a client advocate they must possess the skills and attributes needed for effective communication. Otherwise, how else can they ensure the client is in the position to make informed decisions about their care? The most common features of communication in the role of client advocate include the ability to involve people in all aspects of their own healthcare by listening, respecting, responding, sharing and supporting people's contributions, including their right to decline treatments (ANMC 2006, Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC) 2008).

In recognising the need for advocacy, you should also recognise that conflict may occur on some occasions. For example, possible disagreement within the team regarding a client's management plan, or the decisions made by the client and their family that conflict with those of the healthcare team may lead to differences of opinions emerging. It is essential at times like these for each party to define the area of disagreement in a safe manner and address any concerns. It may be that a resolution cannot be found but discussing the issue openly can go some way to at least helping understand each other's perspective. Remember, in such situations it is the health professional's responsibility to always keep the client's and family's best interests in mind rather than their own, while considering the consequences of how far you as a health professional might wish to take the issue.

Multidisciplinary teams

As a health professional, you may find yourself in a variety of healthcare settings, ranging from large institutions where communication passes down a hierarchy from an administration that has little to do with the everyday life of health professionals, to small teams where there may be a team leader who encourages shared or individual decision making. Up until now the chapter has focused mainly on the one-to-one relationship between a health professional and client. Yet healthcare frequently involves teamwork, requiring professionals to work effectively with each other using good communication and interpersonal skills. Having clear team communication processes enhances not only the team functioning but also an individual member's commitment to the team and its goals. However, this is not always an easy process. Teams do not suddenly start to work well together. They need to develop, grow and mature. The team dynamics will constantly change as new staff arrive and established members leave. As in any group of humans spending time together, the dynamics are often complicated, with potential for problems to arise, particularly in relation to communication between members. The more members there are in a team, the more opportunity for misunderstandings and errors being made in communication. In healthcare this can quite literally be a matter of life and death therefore the need for effective communication is critical.

Many of the problems in communication within a healthcare setting occur due to a breakdown in the listening process. Hearing and listening are distinctly different. Though a team member may hear what is being said, to truly listen requires that person to actively attend, interpret, evaluate and respond to both the verbal and non-verbal message being relayed. As previously discussed in this chapter, the use of active listening skills is important to let the sender know you are listening and understand everything being said. Repetition, clarification, paraphrasing and reflection are essential skills whether you are working with one individual or a team.

TeamSTEPPS is one of many team training programs offering structured communication tools to improve interpersonal communication between health professionals. It recommends various mnemonics to aid the communication process between team members. One such mnemonic is SBAR, which can deliver clear communication about a client's condition in a concise manner to other health professionals. SBAR stands for (TeamSTEPPS 2006):

Situation – what is happening to the client?

Situation – what is happening to the client?

Background – what is the clinical background?

Background – what is the clinical background?

Additional factors may also influence the ability to work and communicate as part of a health team. With the challenge of increased workloads, staff shortages, and the urgency of completing tasks or making decisions within a certain timeframe impacting on health professionals on a frequent if not daily basis, your ability to communicate effectively may become compromised. You may also be distracted by the tasks that need to be completed, begin to suffer stress-related behaviour, begin to question personal issues in terms of your own life and its meaning, or develop a sense of depersonalisation for both clients and staff. For example, the question: ‘Are the pathology results back for bed 16?’ treats the client as an object, not a person. All these factors contribute to poor communication and to treatment regimes that become focused on achieving completion of treatment in the time allowed, rather than on the client's needs.

Conclusion

Communication is a fundamental aspect of the health professional–client relationship. As a health professional, whether introducing yourself, assessing clients or working with them to achieve treatment or educational goals, combining effective communication skills with clinical skills and knowledge can help facilitate positive working relationships between you and your client. Furthermore, an efficient multidisciplinary healthcare team requires effective communication between its members. In summary, good communication skills are an essential part of being a competent health professional.

Bach, S., Grant, A. Communication and interpersonal skills for nurses. Transforming Nursing Practice. Exeter: Learning Matters; 2009.

Casey, A., Wallis, A. Effective communication: principles of nursing practice. Nursing Standard. 2011; 25(32):35–37.

Eubanks, R.L., McFarland, M.R. Chapter 4: Cross-cultural communication. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2010; 21(4):137–150.

Malloy, P., Virani, R., Kelly, K., et al. Beyond bad news: communication skills of nurses in palliative care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2010; 12:166–174.

McCray, J. Preparing for multi-professional practice. In: McCray J., ed. Nursing and multi-professional practice. London: Sage, 2009.

McLean, M., Cleland, J., Worrell, M., et al. ‘What am I going to say here?’ The experiences of doctors and nurses communicating with patients in a cancer unit. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011; 2(339):1–7.

Milan, F.B., Parish, S.J., Reichgott, M.J. Model for educational feedback based on clinical communication skills strategies: beyond the ‘feedback sandwich’. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2006; 18(1):42–47.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Cultural competency in health: a guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra: NHMRC; 2005.

Rosenberg, S., Gallo-Silver, L. Therapeutic communication skills and student nurses in the clinical setting. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2011; 6(1):2–8.

Shuang, L., Volvic, Z., Gallois, C. Introducing intercultural communication: global cultures and contexts. London: Sage; 2011.

TeamSTEPPS Clinical Handover Pilot Study. Safety and Quality Unit, Department of Health South Australia. Online Available http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/TeamSTEPPS.pdf, 2009.

Villagran, M., Goldsmith, J., Wittenberg-Lyles, E., et al. Communicating COMFORT: a communication-based model for breaking bad news in health care interactions. Communication Education. 2010; 59:220–234.

Webb, L. Nursing: communication skills in practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Communication for health in emergency contexts

www.chec.meu.medicine.unimelb.edu.au/resources/index.html

This site provides scenarios and information specifically related to an emergency department.

Communication skills for health professionals

www.oscehome.com/Communication-Skills

This site provides information to improve communication skills particularly related to client interviews.

Cultural connections for learning

www.intstudentsup.org/diversity/resources

This site provides international students and clinical staff valuable resources to promote resilience and effective working in the healthcare workforce.

Introduction to communication skills

http://www.oup.com/uk/orc/bin/9780199582723/webb_ch01.pdf

This site, by Lucy Webb, provides a useful resource to understand the underpinning theories of communication.

www.clinicalskillscentre.ac.uk

http://au.youtube.com/watch?v=22ckNruSnmg

These two sites have interesting written information, as well as numerous videos of healthcare students practising various clinical skills, including communication scenarios. The first is the general website, the second leads more specifically into communication skills.

Royal College of Surgeons (UK)

http://www.intercollegiatemrcs.org.uk/pdf/comms_guidance.pdf

This website contains the instructions for candidates for the Royal College of Surgeons’ communication exam. It provides a good opportunity to view a variety of possible scenarios and issues that are important for beginning health professionals to consider.

Therapeutic communication skills

http://au.youtube.com/watch?v=xpFkrD02t1A&feature=related

This video discusses the elements of basic communication and demonstrates various therapeutic communication skills.

References

ACT Health. Health information for professionals: cultural safety. Online Available http://www.health.act.gov.au/professionals/student-clinical-placements/cultural-safety, 2012. [13 Jan 2012].

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC). National competency standards for the registered nurse. Online Available www.anmc.org.au, 2006. [18 Jun 2012].

Australian Physiotherapy Council (APC). Australian standards for physiotherapy. Online Available http://www.physiocouncil.com.au/australian_standards_for_physiotherapy, 2008. [18 Jun 2012].

Baldwin, M. Patient advocacy: a concept analysis. Nursing Standard. 2003; 17(21):33–39.

Balzer Riley, J. Communication in nursing, seventh ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., et al. Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Bertakis, K.D., Franks, P., Epstein, R.M. Patient-centered communication in primary care: physician and patient gender and gender concordance. Journal of Women's Health. 2009; 18(4):539–545.

Blonna, R., Loschiavo, J., Watter, D. Health counseling: a microskills approach for counselors, educators, and school nurses, second ed. Burlington: Jones and Bartlett; 2011.

Boudreaux, E.D., Friedman, J., Chansky, M.E., et al. Emergency department patient satisfaction: examining the role of acuity. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004; 11:162–168.

Cass, A., Lowell, A., Christie, M., et al. Sharing true stories: improving communication between Aboriginal patients and healthcare workers. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2002; 176(10):466–470.

Chang, M., Kelly, A.E. Patient education: addressing cultural diversity and health literacy issues. Urology Nursing. 2007; 27(5):411–417.

Chochinov, H. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. British Medical Journal. 2007; 335:184–187.

Coulehan, K., Brown, I., Christie, M., et al. Sharing the true stories. Evaluating strategies to improve communication between health staff and Aboriginal patients, Stage 2 report. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2005.

Di Blasi, Z., Harkness, E., Ernst, E., et al. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. The Lancet. 2001; 357(9258):757–762.

Duncan, P. Values, ethics and healthcare. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009.

Egan, G. The skilled helper: a problem-management and opportunity-development approach to helping, ninth ed. Belmont: Thompson Brooks/Cole; 2010.

Health Consumers Queensland. Health advocacy framework. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2010.

Ivey, A.E., Ivey, M.B., Zalaquett, C.P. Intentional interviewing and counseling: facilitating client development in a multicultural society, seventh ed. Belmont: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning; 2010.

Kiesling S., Bratt Paulson C., eds. Intercultural discourse and communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Lawrence, M., Dodd, Z., Mohor, S., et al. Improving the patient journey: achieving positive outcomes for remote Aboriginal cardiac patients. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009.

Leino-Kilpi, H., Johanasson, K., Heikkinen, K., et al. Patient education and health-related quality of life: surgical hospital patients as a case in point. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2005; 20(4):307–331.

Levinson, W. Patient-centred communication: a sophisticated procedure. British Medical Journal – Quality and Safety. 2011; 20(10):823–825.

Maguire, P., Pitceathly, C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. British Medical Journal. 2002; 325(7366):697–700.

Nelson, S., Gordon, G. The complexities of care. Ithaca: ILR Press; 2006.

Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC). The code: standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. Online Available http://www.nmc-uk.org/Publications-/Standards1, 2008. [18 Jun 2012].

Otto, B. Language development in early childhood. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education; 2006.

Ramsden, I.M. Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. Unpublished PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. Online Available www.culturalsafety.massey.ac.nz, 2002. [19 Feb 2008].

Rogers, C. On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1961.

Rogers, C. Comments on the issue of equality in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 1987; 27(1):38–39.

Roy, J. Horizontal violence. ADVANCE for Nurses. Online Available http://nursing.advanceweb.com/editorial/content/editorial.aspx?cc=102740, 2007. [Jun 2012].

Stein-Parbury, J.M. Patient and person: developing interpersonal skills in nursing, fourth ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2009.

TeamSTEPPS. Pocket guide. Team strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

The Joint Commission. Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care: a roadmap for hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace: The Joint Commission; 2010.

Toma, G., Triner, W., McNutt, L.A. Patient satisfaction as a function of emergency department previsit expectations. Annals Emergency Medicine. 2009; 54(3):360–367.

Venetis, M.K., Robinson, J.D., Turkiewitz, K.L., et al. An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: a meta analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Education Counselling. 2009; 77:379–383.

Watson, J. The philosophy and science of caring, revised ed. Boulder: University Press of Colorado; 2008.