Loss

The material in this chapter will help you to:

understand that loss is a central component of experience of many patients and their families

understand that loss is a central component of experience of many patients and their families

identify the wide range of losses patients can experience

identify the wide range of losses patients can experience

recognise common reactions to loss

recognise common reactions to loss

respond appropriately and supportively to grieving patients and their families

respond appropriately and supportively to grieving patients and their families

assess when grief may be complicated and requires more advanced support and assistance.

assess when grief may be complicated and requires more advanced support and assistance.

Introduction

Mourning is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as fatherland, liberty, an ideal and so on … It is well worth notice that, although grief involves grave departures from the normal attitude to life, it never occurs to us to regard it as a morbid condition and hand the mourner over to medical treatment. We rest assured that after a lapse of time it will be overcome and we look upon any interference with it as inadvisable or even harmful.

(Freud 1917 pp 243–244)

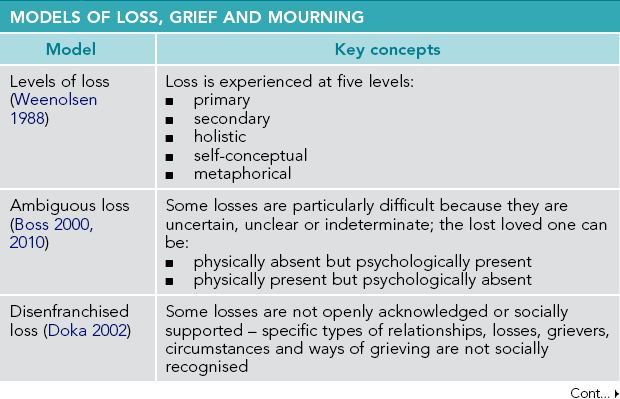

With these words almost a century ago, Freud laid the foundation for understanding the psychological elements of loss, grief and mourning. Indeed, he began to explore the link between grief and healthcare responses. Since then, descriptions of how people grieve and what helps those who experience loss have evolved and expanded. This chapter will explore a range of key theories, models and constructions related to loss, grief, mourning and responses to grief (see Table 11.1), with specific reference to ideas considered relevant to those working in healthcare. Suggestions for helping responses will be discussed. In this chapter, the term ‘health professional’ or ‘helping professional’ refers to those from a wide range of disciplines who work in healthcare settings. For simplicity, the term ‘patient’ is used for those who receive services from and are cared for by health professionals.1

Defining loss

Loss, in one form or another, will affect all of us – whether we are patients or practitioners. Because loss is a universal experience, defining it may seem unnecessary. However, establishing a common description of loss is probably useful. Loss, write Harvey and Weber (1999 p 320), involves ‘a reduction in a person’s resources, whether personal, material, or symbolic, to which the person was emotionally attached’. Weenolsen (1988 p 19) succinctly defines loss as ‘anything that destroys some aspect, whether macroscopic or microscopic, of life and self’. Loss involves the separation from something – maybe large, maybe small – that has meaning to us and to which we feel strongly connected.

Types of loss

The range of possible losses is almost limitless. How can we attempt to understand the diverse types of losses? Weenolsen (1988) proposes the following classification:

Major versus minor loss – We frequently focus on major losses, such as the death of a family member or the devastation of a bushfire. However, seemingly minor losses can have major significance. Weenolsen describes minor losses as ‘the many small deaths of life’ (1988 p 21) that can affect us profoundly because they represent larger losses. For example, older people can experience the termination of their driver's licence as the loss of capabilities, mobility and independence, leading to a strong sense of grief.

Major versus minor loss – We frequently focus on major losses, such as the death of a family member or the devastation of a bushfire. However, seemingly minor losses can have major significance. Weenolsen describes minor losses as ‘the many small deaths of life’ (1988 p 21) that can affect us profoundly because they represent larger losses. For example, older people can experience the termination of their driver's licence as the loss of capabilities, mobility and independence, leading to a strong sense of grief.

Primary versus secondary loss – While primary losses usually are identified easily, secondary or derivative losses may not be recognised and can be more painful. A major illness, such as chronic fatigue or heart disease, can lead to secondary losses of unemployment, significant financial loss, family stress and reduced life choices. Healthcare practitioners are challenged to recognise the range of secondary losses experienced by their patients in order to respond holistically to loss-related needs.

Primary versus secondary loss – While primary losses usually are identified easily, secondary or derivative losses may not be recognised and can be more painful. A major illness, such as chronic fatigue or heart disease, can lead to secondary losses of unemployment, significant financial loss, family stress and reduced life choices. Healthcare practitioners are challenged to recognise the range of secondary losses experienced by their patients in order to respond holistically to loss-related needs.

Actual versus threatened loss – A loss need not actually occur for a grief response to be generated. Weenolsen notes that a threat to safety, self-identity or health can result in a sense of loss – ‘a biopsy may be negative but the self is not the same afterward’ (1988 p 22). Threatened loss is similar to Hockley's (1985) description of deprivation loss, where grief is experienced for something the person never had. Couples undergoing in vitro fertilisation treatment can experience a powerful sense of loss each time a treatment is unsuccessful, complicated by the prospect of childlessness that is threatened if a pregnancy never eventuates.

Actual versus threatened loss – A loss need not actually occur for a grief response to be generated. Weenolsen notes that a threat to safety, self-identity or health can result in a sense of loss – ‘a biopsy may be negative but the self is not the same afterward’ (1988 p 22). Threatened loss is similar to Hockley's (1985) description of deprivation loss, where grief is experienced for something the person never had. Couples undergoing in vitro fertilisation treatment can experience a powerful sense of loss each time a treatment is unsuccessful, complicated by the prospect of childlessness that is threatened if a pregnancy never eventuates.

Internal versus external loss – Weenolsen (1988) argues that all losses have an external and internal element. External losses frequently will involve the associated loss of an internalised self-ideal or societal ideal. This type of loss is common after such health-related experiences as mastectomy, amputation, acquired brain injury, burns or chemotherapy-related hair loss. These external losses can challenge the internalised social constructions about appearance, body image, beauty or gender, leading to potentially profound grief reactions.

Internal versus external loss – Weenolsen (1988) argues that all losses have an external and internal element. External losses frequently will involve the associated loss of an internalised self-ideal or societal ideal. This type of loss is common after such health-related experiences as mastectomy, amputation, acquired brain injury, burns or chemotherapy-related hair loss. These external losses can challenge the internalised social constructions about appearance, body image, beauty or gender, leading to potentially profound grief reactions.

Chosen versus imposed loss – Losses can result from both chosen and imposed life events. For example, migration as a refugee is imposed by persecution or dislocation, leading to the loss of family connections, freedom and financial security. However, choosing to migrate, while often involving positives such as new opportunities, also can involve associated grief. Those who migrate voluntarily can still experience a sense of loss of homeland, national identity, connections to their past, shared experiences with family ‘back home’ and continuity of cultural practices. Other life choices, such as to not marry or have children, can result in a strong sense of regret and grief about what ‘might have been’, even though the loss was chosen.

Chosen versus imposed loss – Losses can result from both chosen and imposed life events. For example, migration as a refugee is imposed by persecution or dislocation, leading to the loss of family connections, freedom and financial security. However, choosing to migrate, while often involving positives such as new opportunities, also can involve associated grief. Those who migrate voluntarily can still experience a sense of loss of homeland, national identity, connections to their past, shared experiences with family ‘back home’ and continuity of cultural practices. Other life choices, such as to not marry or have children, can result in a strong sense of regret and grief about what ‘might have been’, even though the loss was chosen.

Direct versus indirect loss – Weenolsen (1988) describes how loss can occur through the experiences of another person. She notes, for example, the grief that parents can experience through the losses affecting their children, such as serious illness, school difficulties, failed relationships or family problems.

Direct versus indirect loss – Weenolsen (1988) describes how loss can occur through the experiences of another person. She notes, for example, the grief that parents can experience through the losses affecting their children, such as serious illness, school difficulties, failed relationships or family problems.

Levels of loss

Weenolsen also describes five levels of loss, a framework that is particularly useful for understanding the full impact of loss situations:

The primary level of loss – This level of loss is most evident and generally dominates people's perception of a loss situation.

The primary level of loss – This level of loss is most evident and generally dominates people's perception of a loss situation.

The secondary level of loss – This level is about the derivative, concrete losses that follow directly from, usually with some immediacy after, a primary loss. For example, the primary loss of a diagnosis of childhood leukaemia can lead to such secondary losses as financial pressure due to medical expenses, work time lost due to demands of doctors' appointments, and disruption of school attendance and performance due to treatment side effects.

The secondary level of loss – This level is about the derivative, concrete losses that follow directly from, usually with some immediacy after, a primary loss. For example, the primary loss of a diagnosis of childhood leukaemia can lead to such secondary losses as financial pressure due to medical expenses, work time lost due to demands of doctors' appointments, and disruption of school attendance and performance due to treatment side effects.

The holistic level of loss – This level relates to the more abstract losses associated with primary and secondary losses, such as loss of future, dreams, status and security. Childhood leukaemia can result in the loss of hopes for the person's child, loss of safety as the child's life is threatened and loss of family security as the future of a family member becomes uncertain.

The holistic level of loss – This level relates to the more abstract losses associated with primary and secondary losses, such as loss of future, dreams, status and security. Childhood leukaemia can result in the loss of hopes for the person's child, loss of safety as the child's life is threatened and loss of family security as the future of a family member becomes uncertain.

The self-conceptual level of loss – A primary loss can lead to changes in how a person sees themselves because part of the self is perceived to be lost. A child with leukaemia may now see herself as ‘sick’, ‘different’, ‘less competent’ in school and a ‘burden’ on the family's emotional and financial resources.

The self-conceptual level of loss – A primary loss can lead to changes in how a person sees themselves because part of the self is perceived to be lost. A child with leukaemia may now see herself as ‘sick’, ‘different’, ‘less competent’ in school and a ‘burden’ on the family's emotional and financial resources.

The metaphorical level of loss – This level recognises the idiosyncratic meaning that a loss has because the person's beliefs are challenged. A significant loss can lead to questioning of values, beliefs and a person's philosophical views. Childhood leukaemia, for example, may challenge assumptions that children will outlive their parents, that parents are able to protect their children from harm or that God will not allow children to suffer.

The metaphorical level of loss – This level recognises the idiosyncratic meaning that a loss has because the person's beliefs are challenged. A significant loss can lead to questioning of values, beliefs and a person's philosophical views. Childhood leukaemia, for example, may challenge assumptions that children will outlive their parents, that parents are able to protect their children from harm or that God will not allow children to suffer.

There are some important implications from Weenolsen's five-level framework. As Weenolsen (1991 p 56) writes, acknowledging the levels ‘helps us understand better why loss affects us so deeply’. When we see patients who are grieving, we often witness intense and pervasive reactions. Awareness that they are grieving at several levels can help us make sense of these responses. Second, Weenolsen's model demonstrates how grief ‘unfolds’ through the levels and is not static or one-dimensional. Third, this framework provides a guide for more comprehensive support and intervention with grieving people. The responses of helping professionals need to consider and address all levels of loss, rather than focus only on the primary loss.

Ambiguous loss

Ambiguous loss has been described as the most devastating of all losses in personal relationships due to the uncertain, unclear and indeterminate nature of the loss (Bocknek et al 2009, Boss 2000, 2010). Boss describes two types of ambiguous loss. The first type occurs when a loved one is perceived as physically absent but psychologically present. Such loss relates to situations such as missing soldiers, lost or kidnapped children, family members separated by divorce, and relinquishment through adoption. The second type of ambiguous loss is experienced when a loved one is perceived as physically present but psychologically absent. Health-related conditions such as dementia, addictions, mental illnesses and brain injury involve this type of ambiguous loss. The physically present–psychologically absent dilemma also occurs in palliative care if others treat the dying person as if they are already dead (social death) or if the patient lacks consciousness of existence (psychological death) (Kalish 1966 in Doka 2002, Sudnow 1967). Boss anticipates that, as medical advances keep dying patients alive longer, more families will experience the stress associated with ambiguous loss.

Lack of control makes coping with ambiguous loss so difficult. Five factors can interfere with coping:

people are confused by the indefinite nature of the loss and become immobilised

people are confused by the indefinite nature of the loss and become immobilised

the uncertainty prevents adjustment and results in ‘frozen’ relationships with the ambiguously lost person

the uncertainty prevents adjustment and results in ‘frozen’ relationships with the ambiguously lost person

the ambiguous loss is not recognised by the community, with little validation and no rituals

the ambiguous loss is not recognised by the community, with little validation and no rituals

ambiguous losses are more confronting, reminding people that life is not always rational or just (this reality can cause potential supports to withdraw)

ambiguous losses are more confronting, reminding people that life is not always rational or just (this reality can cause potential supports to withdraw)

because ambiguous loss can be prolonged, those who experience it become physically and emotionally exhausted (Boss 2000, 2010).

because ambiguous loss can be prolonged, those who experience it become physically and emotionally exhausted (Boss 2000, 2010).

To help people deal with ambiguous loss, Boss emphasises sharing information with families, including clinical and technical information. She states that ‘clinicians need to realize that by sharing knowledge they are empowering families to take control of their situation even when ambiguity exists’ (Boss 2000 p 23). In Bull's (1998) study of families of people with Alzheimer's, respondents listed receiving information as the most helpful thing for dealing with dementia in the family. Information assists in constructing a reality amid the ambiguity. Meeting others who have experienced such a loss further increases a family's information and support base.

Ambiguous loss also can be traumatising, with symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Boss 2000, 2010). Like an experience of trauma (Harris & Gorman 2011, Herman 2001), ambiguous loss is outside the realm of usual human experience and often involves a threat to the life or physical safety of a loved one. Trauma often relates to a single traumatising event. However, ambiguous loss usually involves a series of psychological ups and downs, with hopes repeatedly dashed so that continuing to try to cope seems futile and learned helplessness can develop. Boss highlights the importance of allowing those experiencing ambiguous loss to tell their story, to receive validation and to have someone help them make sense of what they are experiencing.

Disenfranchised loss and grief

A concept that has significantly expanded awareness about the nature and impact of loss is disenfranchised grief. Kenneth Doka (2002 p 4) defined disenfranchised grief as ‘the grief that persons experience when they incur a loss that is not or cannot be openly acknowledged, publicly mourned, or socially supported’. Losses are disenfranchised by the dominant societal norms or ‘rules’ that define acceptable feeling, thinking and spiritual expression when loss occurs (Doka 2002, Doka & Tucci 2009). Loss experiences that fall outside these rules are not recognised. Doka's work has effectively integrated the psychological and the social elements of loss and grieving by acknowledging that a person's experience of grief is often affected by factors external to the griever.

Doka has proposed the following typology of losses that are disenfranchised:

the relationship is not recognised (e.g. friends, ex-partners, professional helpers, internet relationships, gay partners, companion animals)

the relationship is not recognised (e.g. friends, ex-partners, professional helpers, internet relationships, gay partners, companion animals)

the loss is not acknowledged (e.g. abortion, miscarriage, infertility, secondary losses, non-death losses, loss of connection to land)

the loss is not acknowledged (e.g. abortion, miscarriage, infertility, secondary losses, non-death losses, loss of connection to land)

the griever is excluded (e.g. children, the aged, people with intellectual disabilities)

the griever is excluded (e.g. children, the aged, people with intellectual disabilities)

circumstances of the death (e.g. AIDS-related deaths, suicides, murders)

circumstances of the death (e.g. AIDS-related deaths, suicides, murders)

ways people grieve (e.g. different styles of grieving, cultural differences in grieving).

ways people grieve (e.g. different styles of grieving, cultural differences in grieving).

Health professionals should consider the concept of disenfranchised grief for several reasons. First, we have all been exposed to social norms about ‘acceptable’ loss and grieving and need to be aware of how these norms may influence our professional thinking and practices, possibly resulting in disenfranchising attitudes and behaviours. Second, as noted in Doka's typology above, there are many health-related losses that are not acknowledged. For example, Corr (2002 p 43) maintains that ‘until quite recently and perhaps still today in many segments of society, perinatal deaths, losses associated with elective abortion, or losses of body parts have frequently been disenfranchised’.

Third, health professions, by their nature, can sometimes contribute to disenfranchising processes. The primary focus of healthcare is necessarily on treatment, cure, rehabilitation and recovery. Losses may not fit within such a perspective as they may be perceived as healthcare ‘failures’. Our professional language may be disenfranchising. For example, an amputee rehabilitation setting may describe its work in terms of ‘replacement’ (through a prosthesis), ‘recovery of function’ (through physical and occupational therapies), ‘adjustment’ and ‘progress’. Such language may limit acknowledgement of the patient's deep sense of bodily impairment, of frustration, of lost possibilities and hopes, and of nothing ever being the same again. Similarly, the focus of health professionals is often on symptomatology. Corr argues that referring to grief symptoms disenfranchises grief by failing to recognise the essentially natural and healthy responses to loss found in many grieving behaviours. Speaking about the signs, manifestations or expressions of grief avoids disenfranchising and even pathologising the wide range of appropriate responses to loss (Corr 2002).

Finally, the grief of health professionals may be disenfranchised (Spidell et al 2011). Such professionals may not be considered as ‘legitimate’ grievers when, for example, a patient dies. The health professional–patient relationship may not be recognised as one in which the helper's grief is appropriate. Indeed the concept of ‘being a professional’ often promotes emotional distance between the helper and the patient, resulting in professionals potentially disenfranchising their own grief. For example, after a patient has died nurses are often expected to carry out protocols for managing a dead body and preparing the deceased patient's bed as quickly as possible for the next admission. Frequently little recognition is given by the hospital system, by senior staff and by the nurses themselves to the nurse as a griever.

Nonfinite loss and chronic sorrow

Another concept of particular relevance to the field of healthcare is nonfinite loss. Bruce and Schultz (2001) developed this term through their clinical and research encounters with families of children with developmental disabilities. They recognised that these parents experienced ongoing loss and grief as the impact of their child's disability unfolded throughout the lifespan. Nonfinite loss is contingent on three elements: lifestage development, passage of time and a lack of synchrony between lived experience and hopes and expectations. The loss is often not identified or named until the person reflects back and realises what did not happen in life in comparison to ‘what should have been’ (Bruce & Schultz 2001 p 8).

Nonfinite loss has been associated with situations such as: congenital or acquired disabilities; traumatic injury; ongoing or degenerative illnesses such as dementia; adoption; infertility; separation and divorce; and sexual abuse. These experiences can challenge, even shatter, preconceived ideas of what the world should be like, leading to ongoing, nonfinite loss and grief (Bruce & Schultz 2001). Parents of a child with a disability can be repeatedly reminded of what their child has not been able to achieve in comparison to the hopes and dreams they had for that child (Ray & Street 2007). Indeed, Bruce (2000) reported that approximately 20% of mothers experience symptoms of PTSD after the birth of a child with a disability and that their grief is often disenfranchised. Five cycles of nonfinite grief can be experienced, involving themes of shock, protest/demand, defiance, resignation/despair and integration (Bruce & Schultz 2001). The nonfinite nature of the grieving means these cycles recur: ‘The cycles are not linear, have no end-point and are prone to recycling again and again’ (Bruce & Schultz 2001 p 163).

Similar to nonfinite loss and grief is chronic sorrow. Olshansky (1962) first described chronic sorrow as the intense, pervasive and recurring sadness observed in parents of children with an intellectual disability. Other studies have examined chronic sorrow among parents of children with chronic illness (Bettle & Latimer 2009, Gordon 2009) and female victims of child abuse (Slaughter Smith 2009). Chronic sorrow, while often continuing through a person's life, is considered ‘a normal reaction to the significant loss of normality in the affected individual or the caregiver’ (Burke et al 1992 p 232). Burke et al, writing from a nursing perspective, argue that it is important to recognise the difference between the normality of chronic sorrow and complicated grief or depression. This caution is an important one for health professionals whose culture characteristically seeks to diagnose and treat pathology. Many patients and families with long-term illnesses will be experiencing nonfinite loss and chronic sorrow (e.g. see Bowes et al's 2009 discussion regarding chronic sorrow in parents of children with type 1 diabetes). By missing or mislabelling their patients' grief, health professionals run the risk of disenfranchising patients' losses or responding inappropriately. Chronic sorrow is best treated through recognition of the family's recurrent experiences of grief and supportive responses to their sadness.

Responses to loss

Since Freud's early writing about grief, health professionals have been trying to understand how people respond to loss. Freud's notion that mourning occurred over a period of time has been accepted and this time element of mourning has been described as the grief process.

The grief process

The grief process has been conceptualised in various ways. One approach has been to identify phases or stages in grieving. Erich Lindemann (1944), a pioneer in the study of grief, outlined three phases in the grief process: emancipation from bondage to the deceased, readjustment to the environment without the deceased and the formation of new relationships. Parkes (1972, 1988) and later Bowlby (1980) referred to four phases associated with grieving – numbness, yearning to recover the lost person, disorganisation and despair and reorganisation. Sanders' (1999) model proposed five phases in the mourning process: shock, awareness of loss, conservation-withdrawal, healing and renewal. In her work with terminally ill patients, Kübler-Ross (1969) identified five psychological stages in the dying process. Her staged model of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance has been used to describe the grieving process. However, Kübler-Ross' work was not intended to describe mourning and has limitations as a grief model (Corr 1993, Worden 2010).

The phase/stage view of grief has been criticised for inferring that the grieving process is essentially passive. Attig (1991 p 386) argues that the phase/stage concept frames ‘grieving as yet another thing that happens to bereaved persons, a process into which they are thrust against their will … (with) little choice of paths through the process’. Attig also cautions against any medical conceptualisations of grief, as these too imply that grief is a kind of illness that happens to people and over which people have no choice once a major bereavement occurs. Instead, Attig sees grieving as an active process through which the griever relearns their world.

Tasks of mourning

Psychologist William Worden also argued for a more active view of grieving and developed a widely accepted task model of mourning. Worden (2010) states that a task model fits better with the concept of ‘grief work’ as described by Freud and Lindemann; that is, grievers need to act to move through the grief process. The task model is also seen as consistent with the psychological concept of developmental tasks associated with all human growth. Finally, Worden sees the task model as more useful for practitioners, as ‘the approach implies that mourning can be influenced by intervention from the outside’ (2010 p 26). Both the griever and the helping professional can approach their grief-related work with a greater sense of agency and mastery. Indeed, this author frequently uses, in his own grief-related practice, the terms ‘grieving’ (rather than ‘grief’) and ‘work’ with clients to communicate the active process in which they are observed to be engaging and to acknowledge the often intense effort (work) that they expend in doing their grieving.

Worden's four tasks of mourning set out specific foci for grievers' actions:

1. To accept the reality of the loss. ‘The first task of grieving is to come full face with the reality that the person is dead, that the person is gone and will not return’ (Worden 2010 p 27). This task addresses the numbness, shock and denial noted in phase models. Denial most often involves the facts of the loss, the meaning of the loss or the irreversibility of the loss. Full denial of a loss may be rare but degrees of denial are not uncommon. As a recognised defence mechanism (Goldstein 1995, Grossberg 2008), denial serves to protect us from the anxiety that may overwhelm us. So we face experiences in smaller parts to deal with what we feel ready to face. Sometimes grievers are described by others as ‘being in denial’; health professionals should be aware of not doing this in a way that is dismissive or disenfranchising of patients' or families' grief.

Funerals and other rituals are useful in providing structure and procedures for gradually facing the reality of a loss. Worden states that both intellectual and emotional acceptance of a loss is necessary; less experienced practitioners can overlook emotional acceptance. This task is more difficult for grievers who have experienced a sudden, unexpected death, especially if the body is not seen. If Weenolsen's levels of loss are also considered, the complexity of this task is further evident. As the levels of loss unfold, the reality of the loss keeps changing, requiring this task to be revisited.

2. To work through the pain of grief. Sadness, guilt, anger, loneliness and depressive feelings are often involved in grieving. The intensity of grievers' emotional pain can go beyond what they have previously experienced and they may wonder if they are ‘going crazy’. Because experiencing intense grief pain is so difficult, some people will try to avoid working on this task through stopping painful thoughts, numbing feelings through alcohol or drugs, distracting themselves through work or other activities, or evading painful thoughts and feelings by the ‘geographic cure’ of moving from place to place (Worden 2010 p 31). Some people are afraid of ‘breaking down’, stating ‘If I allow myself to start feeling (e.g. crying), I'm afraid I will never stop!'. McKissock and McKissock (2012) also describe the ‘pharmacological’ effects of major loss, as the griever's biochemistry works to numb the immediate emotional reactions. Further emotional distress can be experienced as the numbing wears off in the weeks following the loss. Family and friends do not like to see their loved ones hurting and may feel helpless about how to respond. As a result, they (and helping professionals) can do or say things that give the message ‘We don’t really want to see your pain’. This is one way that grief responses can be disenfranchised, as discussed above.

3. To adjust to an environment in which the lost person/thing is missing. Worden (2010) identifies three types of adjustment: external adjustments, internal adjustments and spiritual adjustments. External adjustments refer to the many functional changes that occur after the death of a loved one. New skills, roles and knowledge – such as cooking meals, driving the family car, parenting without a partner or managing finances – have to be developed. This process can be a challenge both practically and emotionally as many grievers find their energy levels low, their cognitive abilities taxed and their willingness to face more change limited. Internal adjustments relate to changes in the griever's sense of self. These adjustments often will depend on the nature of the relationship and the attachment with the lost person/thing. For example, a relationship that is highly dependent (i.e. one person depends on another to meet their own needs) can lead to significant internal adjustment difficulties. Loss could activate latent self-images (Berzoff 2011, Horowitz et al 1980). Such self-images may be negative, for example, for a woman who experienced childhood sexual abuse before finding some security in the marriage with her now-deceased husband. Alternatively, reactivated self-images may be positive, for example, for a woman who can now pursue career goals that her husband discouraged. Spiritual adjustments involve making sense of or finding meaning in the loss, similar to Weenolsen's idiosyncratic loss discussed above. Basic assumptions such as ‘the world is a good place’, ‘the world makes sense’ and ‘I am a worthy person’ can be replaced by ideas that ‘the world sucks!’, ‘life is not fair!’ and ‘I must have done something bad for this to happen!’ (Janoff-Bulman 1992, Worden 2010).

4. To emotionally relocate the lost person/thing and move on with life. This task focuses on the importance of grievers ‘finding a place’ for the loss in their life while still moving ahead. Worden originally expressed this task as ‘withdrawing emotional energy from the deceased and reinvesting it in another relationship’ (2010 p 35). However, bereaved people subsequently told Worden that withdrawing was not what they did in their grieving; they tried to stay connected to their loved one. Worden therefore revised this task. Grievers, sometimes with the help of a caring professional, seek to find an appropriate place for the dead in their emotional lives – a place that will enable them to go on living effectively in the world’ (Worden 2010 p 36). The importance of staying connected is evident in the not uncommon stories grievers tell about how upsetting it is when others do not talk about the deceased person, acting as if the dead person never existed. White (1988) also describes the psychological conflict grievers experience when they feel the need, or are expected, to ‘say goodbye’. He proposes that helping grievers to ‘say hello’ to their dead loved one both releases them from the inappropriate expectation of leaving their loved one behind and empowers them to establish an ongoing connection with the deceased.

Continuing bonds

The importance of ‘staying connected’ has been reinforced in the work on continuing bonds. Klass et al (1996) present the findings of various theorists and researchers that support the value for grievers in sustaining their relationship with the lost person. They too question the usefulness of grievers having to ‘let go’:

We propose that it is normative for mourners to maintain a presence and connection with the deceased … We cannot look at bereavement as a psychological state that ends and from which one recovers. The intensity of feelings may lessen and the mourner become more future- rather than past-oriented; however, a concept of closure, requiring a determination of when the bereavement process ends, does not seem compatible with the model suggested by these findings. We propose that rather than emphasizing letting go, the emphasis should be on negotiating and renegotiating the meaning of the loss over time.

(Silverman & Klass 1996 pp 18–19)

The ways in which grievers achieve continuing bonds are creative and fascinating. They reflect the individualised meanings that connecting practices have for the grievers and their families. One family whose daughter died with cancer established a memorial fund at her primary school to cover the costs of their daughter's class cohort for an annual excursion. However, the family realised that this memorial was meaningful primarily to their daughter's classmates and so the funding was maintained only until her class had graduated from their final year of primary school. This memorial provided a continuing bond for both the family and their daughter's school friends.

Marwit and Klass (1996), in their study of 71 university students, identified four ways an important person can play a continuing role after their death. These were:

Role model – someone with whom the student could identify, for example, ‘I remember him as the ideal dad; someone I would like to imitate as a parent’.

Role model – someone with whom the student could identify, for example, ‘I remember him as the ideal dad; someone I would like to imitate as a parent’.

Situation-specific guidance – situations in which the deceased helps the living with a specific situation, for example, ‘I always think about her when I'm trying to make a decision on some big event in my life. I think, What would she do?'

Situation-specific guidance – situations in which the deceased helps the living with a specific situation, for example, ‘I always think about her when I'm trying to make a decision on some big event in my life. I think, What would she do?'

Values clarification – choosing for or against a moral position identified with the deceased, for example, ‘Rick is sort of a motivation for me to continue being sensitive and patient with people’.

Values clarification – choosing for or against a moral position identified with the deceased, for example, ‘Rick is sort of a motivation for me to continue being sensitive and patient with people’.

Remembrance formation – remembering the deceased without that person performing any active function, for example, ‘Now my dad is someone we enjoy reminiscing about … We wonder what he would be like 12 years older and what he would be doing’ (Marwit & Klass 1996 pp 300–301).

Remembrance formation – remembering the deceased without that person performing any active function, for example, ‘Now my dad is someone we enjoy reminiscing about … We wonder what he would be like 12 years older and what he would be doing’ (Marwit & Klass 1996 pp 300–301).

These four ways of continuing bonds can play a significant ongoing function, even when high levels of grief resolution are reported.

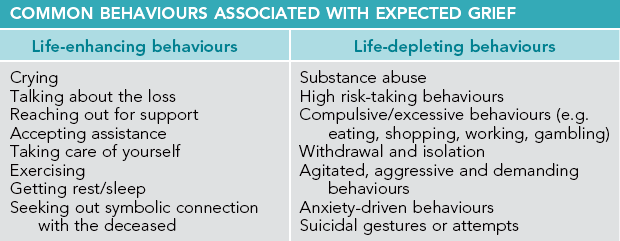

The dual process model

Another perspective on how people respond to loss is presented in the dual process model. Stroebe & Schut (1999, 2008) have argued that the concept of ‘grief work’ does not capture the complexity of activity involved in the process of grieving. They maintain that grief work focuses too much on the need to confront the personal, intrapsychic loss of the loved one without recognising the interpersonal processes that support mourning, the diversity of stressors that grievers need to deal with (in addition to the lost relationship), and the fluctuating nature of grief that can involve swings between the confrontation and avoidance of changes and stressors.

Consequently, the dual process model is constructed around two realms: loss-oriented and restoration-oriented coping (see Fig 11.1). Loss-orientation ‘refers to the concentration on and dealing with, processing of some aspect of the loss experienced itself, most particularly, with respect to the deceased person’ (Stroebe & Schut 1999 p 212). This orientation includes the traditional view of grief work, with its focus on relationship or bonds to the deceased person and the ruminations about the deceased, life together, circumstances surrounding the death and yearning for the deceased. Loss-orientation is usually more evident in early bereavement, although it can dominate the griever's attention periodically over time.

Figure 11.1 The dual process model Source: Stroebe M, Schut H 1999 The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Studies Vol 23, p 197–224

Restoration-orientation addresses the additional stressors associated with a major loss, such as those found in Weenolsen's levels of loss. These stressors include undertaking new tasks, organising one's life without the deceased person, developing a new identity and constructing some meaning in one's new world. A central element of the dual process model is oscillation: the alternation between loss- and restoration-oriented coping. Stroebe and Schut view oscillation as a dynamic, back-and-forth process that allows the griever to alternatively confront or avoid the loss, depending on various ongoing psychological, social and practical demands. This alternation is seen as having major mental and physical health benefits. The griever may choose to take ‘time off’ from grieving, to avoid feelings experienced as too painful at a given point and indeed to use denial in a beneficial way. Stroebe and Schut, citing findings about the severe detrimental psychological and physical effects of unremitting avoidance of grief, argue that the dual process model acknowledges the coping value of the oscillation between confrontation and avoidance. The model's flexibility is seen as accommodating such variables as gender, social and cultural differences in grieving styles and methods (Stroebe & Schut 1999, 2008). Overall, the dual process model effectively expresses the unpredictable, vacillating and ongoing complexities of the grief experience.

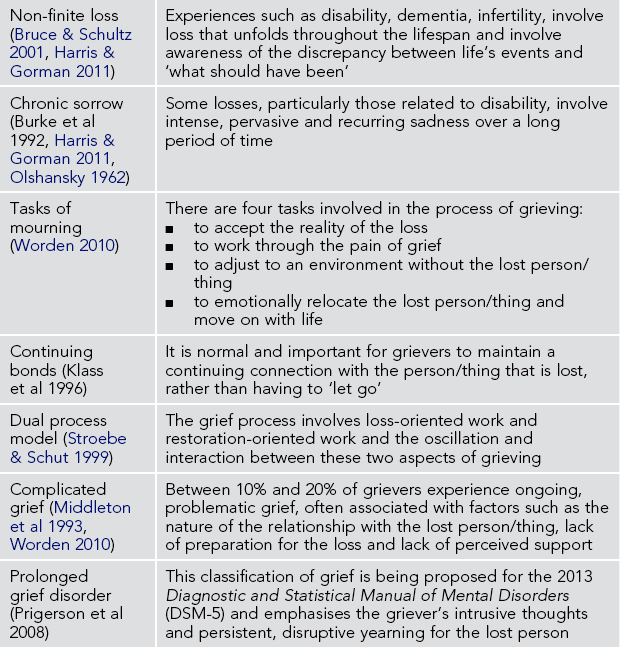

Four elements of grief responses

Worden (2010) has identified four categories of grief responses – feelings, physical sensations, cognitions and behaviours – that usefully capture the wide range of reactions seen in those experiencing uncomplicated grief.

Feelings

Feelings most commonly include shock, sadness, anger, guilt, anxiety, loneliness, helplessness, yearning, despair, depression, emancipation and relief – sometimes even a lack of feeling (anhedonia) (Stroebe et al 2001, Worden 2010). Particularly difficult to accept and manage can be feelings of anger and guilt. Anger ‘is at the root of many problems in the grieving process’ (Worden 2010 p 12). Anger can be directed at the person who died, family members, a seemingly insensitive friend, or God/the world. Health professionals can find themselves the target of such anger. It is important to recognise that this anger almost invariably is not intended as a personal attack. It generally comes from the frustration that nothing could prevent the death/loss and the anxiety that results from ‘being left’ on one's own. Grievers also frequently are able to identify something that should, or should not, have been done in relation to the loss, resulting in feelings of guilt. Anxiety can range from insecurity to anxiety or panic attacks, even phobias in complicated grief reactions. Bereaved people can feel positively about being freed from controlling or abusive relationships or relieved that physical and emotional pain is ended with the death of a suffering loved one.

Physical reactions

Lindemann (1944) is credited with first describing the physical reactions of grief. Such physical sensations as fatigue, hollowness in the stomach, shortness of breath, muscle weakness, oversensitivity to noise and a sense of depersonalisation can exist (Worden 2010). Grievers will sometimes report having the physical symptoms of the person who died (Stroebe et al 2001). Many grievers may not recognise the link between their physical reactions and their grief. It is important therefore for health professionals to be able to identify the physiological elements of grieving and assist grievers in receiving both medical care and grief support.

Cognitive reactions

Cognitive reactions to loss can include disbelief, confusion, problems with memory and concentration, lowered self-esteem, hopelessness, sense of unreality, preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased, sense of presence and hallucinations (Stroebe et al 2001, Worden 2010). It is not unusual for grievers to find their thinking dominated by images and ruminations about the person who died and experiences associated with the death. Some thoughts can be reassuring, such as positive memories about times spent with the deceased loved one, while other thoughts can be distressing. For example, an adult bereaved son reported how the image of his dying father kept appearing over and over again, like a video replaying repeatedly. Thought disturbances are the adjustment required to ‘re-think’ the world in which the lost person or thing is gone.

The cognitive gap or incongruence that results from the absence of a loved one can take some time to be resolved. Preoccupation, sense of presence and hallucinations represent some of the powerful thoughts that occur in grievers' efforts to stay connected to the lost person, while cognitively adjusting to life without that person. Worden (2010) is clear that cognitive processes such as visual and auditory hallucinations belong in a list of normal responses to major loss. Kauffman (2002 p 72) supports this view, stating that ‘the hallucinatory power of the image of the deceased functions to mitigate and integrate death loss’. Hallucinations reflect the strong desire to keep alive what is lost because the person is adjusting to the reality of life with that loss. While some grievers may be disconcerted, fearful or ashamed of hallucinatory thoughts, many find them reassuring, with some even seeking them out through those who claim they can make contact with the dead. Kauffman (2002) argues that if such processes as sense of presence or hallucinations are ignored, suppressed or discouraged by self or others, important grief work is disenfranchised and possibly blocked.

Behavioural reactions

Grievers may engage in a range of behavioural reactions. Common behaviours include agitation, crying, social withdrawal, sleep disturbances, appetite changes, absent-minded behaviour, avoiding reminders of the deceased, searching and calling out, sighing, restless overactivity and visiting places or carrying objects that remind them of the deceased (Stroebe et al 2001, Worden 2010). Behavioural changes will usually correct themselves over time (Worden 2010) as the griever gradually integrates the impact and meaning of the loss. As behaviours are often the visible expressions of feelings and thoughts, it is important that helping professionals know how to interpret such behaviours. Pomeroy and Garcia (2008 p 52) distinguish between life-depleting and life-enhancing behaviours (see Table 11.2). These authors note that behaviours can be life-enhancing at one point and life-depleting at another. For example, crying can be a life-enhancing expression of sadness but prolonged and excessive crying can lead to exhaustion and disruption to activities of daily living. Similarly, while exercising can enhance the griever's physical health, compulsive exercising may serve to avoid dealing with painful feelings.

Cultural considerations

In considering the ideas presented in this chapter, it is worth noting that many of the concepts about loss and grief have come from, and arguably have been dominated by, what might broadly be called Western culture (Allan & Harms 2010, Merritt 2011). Yet, the context of health care is becoming increasingly multicultural. Consequently ‘healthcare professionals need to understand the part that may be played by cultural mourning practices in an individual’s overall grief experience if they are to provide culturally sensitive care to their patients … When assessing a person’s response to the death of a loved one, clinicians should identify and appreciate what is expected or required by the person’s culture’ (National Cancer Institute 2012 p 7). The literature on cultural sensitivity emphasises that culture ‘creates, influences, shapes, limits, and defines grieving, sometimes profoundly’ (Rosenblatt 2008 p 208).

Efforts to understand how a patient or family from any given culture might grieve run the risk of being simplistic and therefore unhelpful (Rosenblatt 2008). However, existing guidelines can make such efforts more productive. The following five questions have been highlighted as particularly important to ask those coping with the death of a loved one:

What are the culturally prescribed rituals for managing the dying process, the body of the deceased, the disposal of the body, and commemoration of the death?

What are the culturally prescribed rituals for managing the dying process, the body of the deceased, the disposal of the body, and commemoration of the death?

What are the family's beliefs about what happens after death?

What are the family's beliefs about what happens after death?

What does the family consider an appropriate emotional expression and integration of the loss?

What does the family consider an appropriate emotional expression and integration of the loss?

What does the family consider to be the gender rules for handling the death?

What does the family consider to be the gender rules for handling the death?

Do certain deaths carry a stigma (e.g. suicide), or are certain types of death especially traumatic for that cultural group (e.g. death of a child)? (McGoldrick et al 2004, National Cancer Institute 2012).

Do certain deaths carry a stigma (e.g. suicide), or are certain types of death especially traumatic for that cultural group (e.g. death of a child)? (McGoldrick et al 2004, National Cancer Institute 2012).

Although detailed examination of grief-related cultural beliefs and practices is not possible here, examples of cultural beliefs and practices include the following:

In some cultures, bereaved people ‘somaticize grief, so that a grieving person often feels physically ill’ (Rosenblatt 2008 p 212).

In some cultures, bereaved people ‘somaticize grief, so that a grieving person often feels physically ill’ (Rosenblatt 2008 p 212).

Some immigrants to Australia may explain child and maternal death as the result of the life aura of the mother and baby being imbalanced, the mother behaving badly towards her parents, or the mother having an encounter with a malevolent spirit (Rice 2000).

Some immigrants to Australia may explain child and maternal death as the result of the life aura of the mother and baby being imbalanced, the mother behaving badly towards her parents, or the mother having an encounter with a malevolent spirit (Rice 2000).

The Japanese practice of ancestor worship (Kaneko 1990, Klass 1996, Valentine 2009) involves an elaborate set of rituals and enables the living to maintain personal, emotional bonds with relatives who have died over a period of 35–50 years. A focal point for ancestor worship is an altar in the home. Interestingly, in Western societies (that lack the rich memorial/connecting rituals of other cultures) efforts by grieving families to create spaces for remembering can lead to such disparaging and disenfranchising comments as, ‘They have turned that place into a shrine!’

The Japanese practice of ancestor worship (Kaneko 1990, Klass 1996, Valentine 2009) involves an elaborate set of rituals and enables the living to maintain personal, emotional bonds with relatives who have died over a period of 35–50 years. A focal point for ancestor worship is an altar in the home. Interestingly, in Western societies (that lack the rich memorial/connecting rituals of other cultures) efforts by grieving families to create spaces for remembering can lead to such disparaging and disenfranchising comments as, ‘They have turned that place into a shrine!’

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people view the loss of land and identity as continuing pervasive losses that influence and interact with their current losses, resulting in what has been described as ‘malignant grief’ (Merritt 2011).

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people view the loss of land and identity as continuing pervasive losses that influence and interact with their current losses, resulting in what has been described as ‘malignant grief’ (Merritt 2011).

Health professionals clearly cannot be ‘experts’ in the various cultures of their patients. However, by making a commitment to cultural sensitivity, they can develop practice that is ‘genuinely open, curious, and free of assumptions’ (Gunaratnam 1997) and allows them to learn from and work with patients to provide culturally appropriate grief support and care.

Responding to those who are grieving

All health professionals will encounter patients or clients who have experienced significant losses. Most deaths occur in healthcare facilities, particularly hospitals, nursing homes and hospice/palliative care settings. In a Scottish study Stephen et al (2009) found that health professionals were generally the first point of engagement for bereaved individuals and families. It is essential therefore that such professionals are able to recognise their patients' grief and respond in appropriate and helpful ways.

Efforts to determine what kinds of assistance are effective with grievers have identified three levels of intervention. The first level, described as primary preventive intervention (Neimeyer & Currier 2009), would offer assistance to all grievers experiencing uncomplicated grief. Apart from the costs of such a universal approach, there is evidence that primary prevention is not needed by everyone (Worden 2010) and that it generally is not effective (Jordan & Neimeyer 2003, Larson & Hoyt 2007, Neimeyer 2000). Secondary preventive interventions focus on people who are at risk of complications in their grieving and may result in beneficial outcomes, at least in the short term (Schut et al 2001). A third level of intervention involves those who experience complicated grief and research indicates that such intervention reliably achieves positive outcomes for the griever (Boelen et al 2011, Jacobs & Prigerson 2000, Neimeyer 2000).

What works and doesn't work in assisting those who are bereaved remains an area of ongoing debate. The author's clinical experience suggests that grief support and counselling can be beneficial to a wide range of grievers and that we should be cautious about assuming that ‘normal’ grief does not benefit from supportive intervention. The appreciation that grievers express for the concern, care and support shown by others during times of significant loss clearly indicates there is benefit from such helping actions. For this reason health professionals need to be willing to offer support to grieving patients and families while being respectful of those who do not wish assistance.

The scope of this chapter does not allow a comprehensive discussion of intervention methods. However, Worden (2010 p 52) sets out four useful goals for grief support and counselling, based on his tasks of mourning:

to increase the reality of the loss

to increase the reality of the loss

to help grievers deal with their feelings

to help grievers deal with their feelings

to help the griever overcome obstacles to readjustment after the loss

to help the griever overcome obstacles to readjustment after the loss

to help the griever find a way to remember the deceased/lost object while being prepared to reinvest in life.

to help the griever find a way to remember the deceased/lost object while being prepared to reinvest in life.

Box 11.1 summarises guidelines that health professionals can consider in supporting those who are grieving.

Complicated grief

Within the loss and grief field, perhaps one of the most enduring and challenging questions has been: ‘When is a person’s grieving not normal?’ The difficulty in understanding ‘not-normal’ grief is illustrated by the variety of terms that have been used to describe such a phenomenon including absent, abnormal, distorted, morbid, maladaptive, truncated, atypical, pathological, prolonged, unresolved, neurotic, dysfunctional, chronic, exaggerated, masked and delayed grief (Currier et al 2009, Lobb et al 2006, Middleton et al 1993). The preferred term today is complicated grief. It is estimated 10% to 20% of people experience a prolonged, painful grieving process in which the loss is not integrated into their life (Prigerson & Jacobs 2001a, Shear & Shair 2005).

In the first few months after a loss, distinguishing uncomplicated grief from complicated grief is generally difficult due to the intensity of grief in its early acute period. However, after six months, more complicated grief is evident through such indicators as suicidal thoughts and gestures, depressive disorders, post-traumatic reactions and persistent grief reactions (Ray & Prigerson 2006). One of the difficulties in identifying complicated grief has been the lack of valid and reliable measurements of grief. Several grief inventories and questionnaires have been developed; however, the usefulness of many has been questioned (Neimeyer & Hogan 2001). A shortlist of recommended grief measurement instruments includes the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG) (Faschingbauer et al 1987), the Grief Experience Inventory (GEI) (Sanders et al 1985) and the Core Bereavement Items (CBI) (Burnett et al 1997), the last developed in Australia. However, such scales are appropriate for identifying complicated grief only if there is a point at which the line between uncomplicated and complicated grief can be determined and more work is needed in this regard.

Another approach has sought to isolate the specific factors and reactions that are particular to complicated grief. Since the 1990s, two groups of researchers have independently been working on a description and measure of complicated grief (Horowitz et al 1997, Prigerson et al 1997). The goal has been to develop criteria for complicated grief that would be accepted within the mental health field, and therefore included in the next Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), scheduled for publication in May 2013. The DSM is an international reference for diagnosing psychiatric disorders and the current DSM-IV does not categorise complicated grief. The concern was that complicated grief has been inappropriately associated with depressive, anxiety or post-trauma reactions and therefore requires a diagnostic category of its own.

Over time, various diagnostic terms have been suggested by the researchers, including complicated grief disorder (Horowitz et al 1997), traumatic grief (Prigerson et al 1997, Prigerson & Jacobs 2001b) and prolonged grief disorder (Prigerson et al 2008). As a result of this work, the DSM-5 Task Force of the American Psychiatric Association has proposed a new diagnosis, persistent complex bereavement-related disorder, in Section III of DSM-5. The task force acknowledges the significant distress and functional impairment identified in research on the two constructs ‘complicated grief’ and ‘prolonged grief’. However, they see important differences between these constructs and have placed persistent complex bereavement-related disorder in an appendix, with the expectation that further research will occur ‘to develop the best empirically-based set of symptoms to characterize individuals with bereavement-related disorders’ (APA 2012).

Similar to other disorders in DSM, persistent complex bereavement-related disorder has various criteria (Criterion A to E), all of which must be met for a diagnosis to be made. The death must have occurred at least 12 months before, suggesting that complicated grief is more accurately diagnosed beyond the early months of bereavement. The criteria build on the work of researchers such as Prigerson by including: persistent yearning and preoccupation; difficulty accepting the death; and feelings of anger, isolation and meaningless. Notable is the mention of how criteria should be adapted for bereaved children, and reference to specific factors associated with traumatic bereavement, that is, following a death that occurred in traumatic circumstances, such as by suicide, homicide or in a disaster. The criteria also note the importance of determining whether bereavement reactions are outside accepted religious and cultural norms. Overall, the criteria for persistent complex bereavement-related disorder seek to provide guidelines for determining whether grief reactions are problematic based on their frequency, severity and level of impairment to daily functioning. It will be interesting to see how continuing research on complicated grief influences future classification of this disorder.

Theorists and researchers for some time have explored factors that contribute to complicated grief (Middleton et al 1993). Is it due to the griever's personality, previous life experiences, lack of social support or the nature of the loss? Interestingly, recent work proposes that complicated grief be viewed as an attachment disorder (Prigerson et al 2008, Ray & Prigerson 2006). Previously, Bowlby (1982) conceptualised grief as a response to separation and argued that difficulties grieving as an adult were related to disruptions in a person's childhood attachments with parents or other significant carers. Three pathological attachment patterns were identified:

An anxious attachment to parents would result in insecure attachments to significant others in adulthood, overdependence and chronic grief following a major loss.

An anxious attachment to parents would result in insecure attachments to significant others in adulthood, overdependence and chronic grief following a major loss.

A child who was reluctant to accept care and was highly self-sufficient was described as compulsively self-reliant and therefore likely to deny loss and experience delayed grief.

A child who was reluctant to accept care and was highly self-sufficient was described as compulsively self-reliant and therefore likely to deny loss and experience delayed grief.

Chronic grief also was likely to be experienced by a compulsive caregiver, someone whose role as a child was one of giver rather that receiver of care.

Chronic grief also was likely to be experienced by a compulsive caregiver, someone whose role as a child was one of giver rather that receiver of care.

Prigerson's research group (Ray & Prigerson 2006) suggests that attachment-related risk factors for complicated grief include:

the closeness of the relationship with the deceased

the closeness of the relationship with the deceased

dependent, confiding, close relationships – these lead to poorest bereavement adjustment, whereas conflicted relationships result in lower rates of bereavement disorders

dependent, confiding, close relationships – these lead to poorest bereavement adjustment, whereas conflicted relationships result in lower rates of bereavement disorders

damaged sense of security due to childhood abuse or severe neglect

damaged sense of security due to childhood abuse or severe neglect

Two other risk factors are the griever's perception of being unsupported and lack of preparation for the death. This latter factor, among others, makes suicide deaths particularly difficult to deal with. Loss through suicide has been identified as a specific risk factor for complicated grief (as noted above in relation to traumatic bereavement in DSM-5). For further information about helping those bereaved through suicide see Clark and Goldney (2002), Hawton and Simkin (2008) or Maple et al (2010).

Significant negative health outcomes have been associated with complicated grief, including cancer risk, hypertension, suicidal ideation, hospitalisations, alcohol/cigarette consumption and depressive symptoms (Buckley et al 2009, Ray & Prigerson 2006). For example, people experiencing complicated grief at six months post-loss are 16 times more likely to have changes in smoking at 13 months post-loss, seven times more likely to experience changes in eating, and almost three times more likely to experience depression (Zhang et al 2006 p 1195).

The proposed DSM-5 model arguably is current best practice in distinguishing between normal and complicated grief and is expected to play a key role in establishing a ‘gold standard’ for reliably identifying complicated grief as a specific disorder. The benefits of such a consensus about complicated grief include: more accurate assessment/diagnosis of complicated grief; increased consistency of practice within the loss and grief field; and greater access to appropriate services by those experiencing complicated grief. Establishing complicated grief as a specific disorder could, for example, enable grievers to more readily access mental health services under Medicare funding. On the other hand, including complicated grief in the DSM potentially stigmatises grievers, as can happen to others with mental health problems. A possible response to this argument is that complicated grief is currently disenfranchised by not being accurately recognised by practitioners and health policymakers and that situating complicated grief among depressive and post-trauma reactions is already stigmatising.

Conclusion

This chapter highlights the importance that experiences of loss and grief reactions can play in the lives of those with whom we work as health professionals. Losses and grief reactions need to be incorporated into health assessments and appropriate supportive responses included in healthcare plans. If this does not happen we run the risk of further disenfranchising the grief of our patients and missing opportunities to assist them in their grief work. Health professionals from all disciplines are positioned to play a key role in the identification, assessment and support of grief reactions. It is hoped that readers of this chapter will consider how they can take up this challenge in their practice.

Dickenson D., Johnson M., Katz J., eds. Death, dying and bereavement. London: Sage, 2000.

Doka K., ed. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges and strategies for practice. Champaign: Research Press, 2002.

McKissock, M., McKissock, D. Coping with grief, fourth ed. Sydney: ABC Books; 2012.

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., Stroebe, W. Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet. 2007; 370:1960–1973.

Worden, W. Grief counselling and grief therapy: a handbook for the mental health practitioner, fourth ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement

This website for the Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement (Melbourne) links to an extensive list of related websites, provides information on the peer-reviewed journal Grief Matters: The Journal of Grief and Bereavement and describes continuing education events. Look under ‘Resources’ for weblinks and podcasts of conference presentations.

Australian Child & Adolescent Trauma, Loss & Grief Network

www.earlytraumagrief.anu.edu.au

Affiliated with the Australian National University, this network brings together evidence-based resources and research to make them more accessible to those working with, or interested in, children and young people who have been affected by trauma and grief. Check the section on ‘Grief & loss’ for a range of resources.

This website for the Bereavement Care Centre in Sydney includes a useful section on ‘Resources’. In particular, look at the Health Care Report under ‘Articles’ (in the ‘Resources’ section) for a discussion debunking some myths about bereavement and grief.

This website of the British Medical Journal includes many articles and news items about grief associated with healthcare-related experiences. Click on the ‘Search’ window and use ‘grief’ or ‘loss’ as key words.

References

Allan, J., Harms, L. ‘Power and prejudice’: thinking differently about grief. Grief Matters. 2010; 13(3):72–75.

Attig, T. The importance of conceiving of grief as an active process. Death Studies. 1991; 15:385–393.

Berzoff, J. The transformative nature of grief. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2011; 39:262–269.

Bettle, A., Latimer, M. Maternal coping and adaptation: a case study examination of chronic sorrow in caring for an adolescent with a progressive neurodegenerative disease. Canadian Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2009; 31(4):15–21.

Bocknek, E., Sanderson, J., Broitner, P. Ambiguous loss and posttraumatic stress in school-aged children of prisoners. Journal of Child Family Studies. 2009; 18:323–333.

Boelen, P., deKeijser, J., van den Hout, A., et al. Factors associated with outcomes of cognitive-behavioural therapy for complicated grief: a preliminary study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2011; 18:284–291.

Boss, P. Ambiguous loss: learning to live with unresolved grief. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2000.

Boss, P. The trauma and complicated grief of ambiguous loss. Pastoral Psychology. 2010; 59:137–145.

Bowes, S., Lowes, L., Warner, J., et al. Chronic sorrow in parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009; 65(5):992–1000.

Bowlby, J. Loss: sadness and depression, Vol 3: Attachment and loss. London: Penguin Press; 1980.

Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982; 52:664–678.

Bruce, E. Grief, trauma and parenting children with disability: cycles of disenfranchisement. Grief Matters. 2000; 3(2):27–31.

Bruce, E., Schultz, C. Nonfinite loss and grief: a psychoeducational approach. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes; 2001.

Buckley, T., Bartrop, R., McKinley, S., et al. Prospective study of early bereavement on psychological and behavioural cardiac risk. Internal Medicine Journal. 2009; 39:370–378.

Bull, M.A. Losses in families affected by dementia: strategies and service issues. Journal of Family Studies. 1998; 4:187–199.

Burke, M., Hainsworth, M., Eakes, G., et al. Current knowledge and research on chronic sorrow: a foundation for inquiry. Death Studies. 1992; 16:231–245.

Burnett, P., Middleton, W., Raphael, B., et al. Measuring core bereavement phenomena. Psychological Medicine. 1997; 27:49–57.

Carnelley, K., Wortman, C., Bolger, N., et al. The time course of grief reactions to spousal loss: Evidence from a national probability sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006; 91(3):476–492.

Clark, S., Goldney, R. The impact of suicide on relatives and friends. In: Hawton K., van Heeringen K., eds. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Chichester: Wiley, 2002.

Corr, C. Coping with dying: lessons that we should and should not learn from the work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Death Studies. 1993; 17:69–83.

Corr, C. Revisiting the concept of disenfranchised grief. In: Doka K., ed. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges and strategies for practice. Champaign: Research Press, 2002.

Currier, J., Holland, J., Neimeyer, R. Assumptive worldviews and problematic reactions to bereavement. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress and Coping. 2009; 14(3):181–195.

Doka, K., Tucci, A. Living with grief: diversity and end of life care. Washington: Hospice Foundation of America; 2009.

Doka K., ed. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges and strategies for practice. Champaign: Research Press, 2002.

Faschingbauer, T., Zisook, S., DeVaul, R. The Texas revised inventory of grief. In: Zisook S., ed. Biopsychosocial aspects of bereavement. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1987.

Freud, S. 1917. Mourning and melancholia. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, volume XIV (1914–1916): on the history of the psycho-analytic movement. Papers on metapsychology and other works, 237–258.

Goldstein, E. Ego psychology and social work practice, second ed. New York: Free Press; 1995.

Gordon, J. An evidence-based approach for supporting parents experiencing chronic sorrow. Paediatric Nursing. 2009; 35(2):115–119.

Grossberg, R. Psychoanalytic contributions to the care of medically fragile children. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2008; 14(5):307–311.

Gunaratnam, Y. Culture is not enough: a critique of multi-culturalism in palliative care. In: Field D., Hockey J.L., Small N., eds. Death, gender, and ethnicity. London: Routledge, 1997.

Harvey, J., Weber, A. Why there must be a psychology of loss. In: Harvey J., ed. 1999. Perspectives on loss: a sourcebook. Philadelphia: Bruner/Mazel, 1999.

Harris, E., Gorman, D. Grief from a broader perspective: non finite loss, ambiguous loss and chronic sorrow, Ch 1 in D. Harris Reflecting on change loss and transitions in everyday life. New York: Routledge; 2011.

Hawton, K., Simkin, S. Help is at hand: a resource for people bereaved by suicide and other sudden, traumatic death. The Centre for Suicide Research, University of Oxford. Online Available http://cebmh.warne.ox.ac.uk/csr/linksbereaved.html, 2008. [10 Sep 2012].

Herman, J. Trauma and recovery: from domestic abuse to political terror. London: Pandora; 2001.

Hockley, R. The precipitants of grief. In: National Association for Loss and Grief, The family and grief, Proceedings of the Fourth National Conference. Sydney: National Association for Loss and Grief; 1985:45–56.

Horowitz, M.J., Siegel, B., Holen, A., et al. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997; 154:904–910.

Horowitz, M.J., Wilner, N., Marmar, C., et al. Pathological grief and the activation of latent self images. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980; 137(10):1157–1162.

Jacobs, S., Prigerson, H. Psychotherapy of traumatic grief: a review of evidence for psychotherapeutic treatments. Death Studies. 2000; 24:479–495.

Janoff-Bulman, R. Shattered assumptions: towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press; 1992.

Jordan, J., Neimeyer, R. Does grief counselling work? Death Studies. 2003; 27:765–786.

Kalish, R. A continuum of subjectively perceived death. The Gerontologist. 1966; 6:73–76.

Kaneko, S. Dimensions of religiosity among believers in Japanese folk religion. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990; 29(1):1–18.

Kauffman, J. The psychology of disenfranchised grief: liberation, shame and self-disenfranchisement. In: Doka K., ed. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges and strategies for practice. Champaign: Research Press, 2002.

Klass, D. Grief in an Eastern culture: Japanese ancestor worship. In: Klass D., Silverman P., Nickman S., eds. Continuing bonds: new understandings of grief. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis, 1996.

Klass D., Silverman P., Nickman S., eds. Continuing bonds: new understandings of grief. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis, 1996.

Kübler-Ross, E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan; 1969.

Larson, D., Hoyt, W. What has become of grief counselling? An evaluation of the empirical foundations of the new pessimism. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007; 38(7):347–355.

Lindemann, E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1944; 101:141–148.

Lobb, E., Kristjanson, L., Auon, S., et al. An overview of complicated grief terminology and diagnostic criteria. Grief Matters. 2006; 9(2):28–32.

Maple, M., Edwards, H., Plummer, D., et al. Silenced voices: hearing the stories of parents bereaved through the suicide death of a young adult child. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2010; 18(3):241–248.

Marwit, S., Klass, D. Grief and the role of the inner presentation of the deceased. In: Klass D., Silverman P., Nickman S., eds. Continuing bonds: new understandings of grief. Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis, 1996.

McGoldrick M., Schlesinger J., Lee E., et al, eds. Living beyond loss: death in the family. New York: WW Norton, 2004.

McKissock, M., McKissock, D. Coping with grief, fourth ed. Sydney: ABC Books; 2012.

Merritt, S. First Nations Australians – surviving through adversities and malignant grief. Grief Matters. 2011; 14(3):74–77.

Middleton, W., Raphael, B., Martinek, N., et al. Pathological grief reactions. In: Stroebe M., Stroebe W., Hanssen R., eds. Handbook of bereavement: theory, research and intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

National Cancer Institute. Cross-cultural responses to grief and mourning. Online Available http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportive-care/bereavement/HealthProfessional/page7, 2012. [10 Sep 2012].

Neimeyer, R. Lessons of loss: a guide to coping. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998.

Neimeyer, R. Searching for the meaning of meaning: grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Studies. 2000; 24:531–558.

Neimeyer, R. Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2007.

Neimeyer, R., Currier, J. Grief therapy: evidence of efficacy and emerging directions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009; 18(6):352–356.

Neimeyer, R., Hogan, N. Quantitative or qualitative? Measurement issues in the study of grief. In: Stroebe M., Hansson R., Stroebe W., et al, eds. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 2001.

Nikcevic, A., Kuczmierczyk, A., Nicolaides, K. The influence of medical and psychological interventions on women's distress after miscarriage. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007; 63(3):283–290.

Olshansky, S. Chronic sorrow: a response to having a mentally defective child. Social Casework. 1962; 43:191–193.

Parkes, C.M. Bereavement: studies of grief in adult life. London: Tavistock; 1972.

Parkes, C.M. Bereavement as a psychosocial transition: process of adaptation to change. Journal of Social Issues. 1988; 44:53–65.

Pomeroy, E., Garcia, R. The grief assessment and intervention workbook: a strengths perspective. Belmont: Brooks/Cole; 2008.

Prigerson, H.G., Bierhals, A.J., Kasl, S.V., et al. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997; 154:616–623.

Prigerson, H., Jacobs, S. Caring for bereaved patients: all the doctors just suddenly go. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001; 286:1369–1376.

Prigerson, H.G., Jacobs, S.C. Diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief: a rationale, consensus criteria, and preliminary empirical test. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.