CHAPTER 16 Documentation and reporting skills

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Define the purpose of nurse documentation and reporting

• Discuss the legal and ethical considerations associated with documentation

• Describe guidelines for documenting client information

• Identify the types of documentation formats in use

• Review case management and critical pathway systems

• Determine the principles for reporting client information

• Develop and practise the skills of verbal and written reporting and recording in the delivery of client care

The term documentation refers to any written or electronically generated information about a client or client group that describes the care or service provided to that client or client group. Health records include paper documents or electronic documents such as faxes, emails, audio or images (including video or digital images).

Several types of records may be used to communicate information about the client; these include, but are not limited to, integrated progress notes, nursing admission formats, observation charts, incident reports, fluid balance charts, medication charts and care pathways.

I was involved in the care of a young girl who had surgery for a brain tumour. Everything went well at first and she recovered quickly while in the paediatric intensive care. She was discharged to the ward and within 24 hours she went downhill. She was rushed to the operating theatre to undergo further surgery. It did not go well and the family filed for damages. It was a very stressful time for all involved, giving statements and being on call to give evidence, and although everyone involved agreed that there was no wrongdoing on any one’s part, the court ruled in favour of the family. This finding was completely founded on the basis of the absence of documentation; because there was no documentation in the progress notes from when the client had left the paediatric ICU to go to the ward, there was no evidence that any action had been taken and thus there was no evidence to prove what happened—not documented, not done!

PURPOSE OF DOCUMENTATION

The primary purpose of documentation is to communicate information to the healthcare team caring for the client. Nurses provide 24-hour care; therefore, information exchange whether verbal or documented is a significant part of nurse activity and must be reliable (Joanna Briggs Institute 2011). Through documentation nurses communicate to other nurses and the healthcare team their assessment of the status of clients, nursing interventions that are carried out and the outcome of these interventions.

There are a number of other purposes of nursing documentation; these include professional accountability, legislative requirements, quality improvement, research and resource management and funding.

Professional accountability

In discussing the importance of nursing documentation, Jefferies and colleagues (2010a:113) state that ‘not only is nursing documentation a repository of knowledge about the client, it is also verifiable evidence showing how decisions are made and records the results of those decisions’. Documentation demonstrates nurse accountability and records professional practice. It may be used to determine responsibility of care providers and to resolve questions or concerns in relation to care required. The nurse’s documentation may be used in relation to performance management, internal organisational inquiries and/or legal proceedings (such as civil lawsuits or coronial inquests).

Legislative requirements

Nurses are required to document in accordance with standards of practice of their profession and organisational policy and procedure. The enrolled nurse competency standards for Australia and New Zealand reflect the minimum standard for documentation and reporting. These standards are used to assess the performance of students to determine if the student has met the standards to gain a licence to practise. These standards are also used to assess the ongoing performance of an enrolled nurse in professional practice, specifically in complaint investigation of a professional practice matter.

Legislation may further identify and require specific information and content to be recorded and maintained. Failure to keep and maintain certain documentation records as required, falsifying documentation, incomplete or inaccurate documentation, signing or issuing a document that the person knows or suspects to be false or misleading, may be found to constitute unprofessional conduct by a regulatory authority. For an outline of Australian and New Zealand competency standards that relate to documentation see Clinical Interest Boxes 16.1 and 16.2.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.1 Competencies for the enrolled nurse scope of practice

Competency 2.2: Contributes to nursing assessments by collecting and reporting information to the registered nurse

Competency 2.3: Recognises and reports changes in health and functional status to the registered nurse or directing health professional.

Competency 2.5: Ensures documentation is accurate and maintains confidentiality of information.

Competency 3.2: Communicates effectively as part of the healthcare team.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.2 National competency standards for the enrolled nurse

These standards relate directly to documentation and reporting

Competency element 6.1: Accurately collects and reports data regarding the health and functional status of individuals and groups.

Competency element 7.2: Recognises and reports changes in the health and functional status of individuals/groups to the registered nurse.

Competency element 7.3: Ensures communication, reporting and documentation are timely and accurate.

Quality improvement and research

Documentation is used by organisations to evaluate professional practice as part of quality improvement processes, including performance reviews, audits, organisational accreditation processes and incident investigations. In addition, health records provide valuable information for medical research in relation to clinical interventions, evaluation of patient outcomes and client care.

Resource management and funding

Governments are progressively moving towards systems of activity-based funding, which means that health services are funded on the basis of their expected activity. In residential care, the activity is counted per day. In most hospital models, activity is counted by ‘episode of care’, which refers to the whole time a client is in hospital from admission to discharge. The Royal College of Nursing Australia (2011) has raised concerns that ‘current models of activity-based funding do not capture the unit price and characteristics of nursing services, and casemix classifications that are predominantly medically based fail to reflect nursing sensitive information’. Nevertheless, nursing documentation will be of growing importance because it will help to determine the most appropriate level of service delivery for the provision of care. Nurses must document the elements of a quality assessment, monitor findings and respond appropriately.

LEGAL AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The promise of confidentiality encourages open communication between the client and healthcare team. The nurse has a legislative, professional and ethical obligation to protect client confidentiality. In New Zealand and some states in Australia there are legislative provisions to protect client privacy and confidentiality. The nurse needs to understand the application of the law in the jurisdiction they practise in. Principles common across all jurisdictions include:

• Descriptions of which health information is collected and why

For example, the nurse needs to be aware that the healthcare agency owns the healthcare record and the law provides provisions for the client to access their healthcare record and also provides provisions for the restriction of access in specific circumstances to the client.

The provisions of legislation to protect client privacy and confidentiality also apply to client records that are stored electronically. Health services and departments of health install systems to monitor, protect and recover data that is stored electronically. The nurse assists in this process by using personal passwords to enter and sign off from electronic records, not sharing passwords with others, never leaving computers unattended when logged on, ensuring that screens displaying client information are not visible to the public and knowing the health service policy for protecting and reporting potential breaches of confidentiality.

Matters of privacy, confidentiality and consent must be a consideration by nurses, students and organisations when using exemplars of practice and journalling of practice experience. As New Zealand and rural Australia have small populations, which can result in contextual descriptions along with the location of the author(s) enabling identification of person(s) involved in the exemplar, the Kleinman approach to protect the anonymity of clients and practitioners is recommended (New Zealand Nurses Organisation 2005):

I have removed or changed certain information that might identify them. When I have made such changes, I have drawn on information from clients with similar problems to make the alteration valid in the light of the experiences of the client group as a whole.

It is recommended that the nurse obtain consent from those involved in the situation described when using exemplars or journals. This means talking with the client and staff involved and sharing the story with them and letting them know how it would be used.

DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES AND PRINCIPLES

Documentation in the healthcare record is recorded in the format of date and time. Date is recorded in the format of dd/mm/yyyy and times are recorded using the 24-hour clock. In this format, rather than time being recorded as 1 pm, it is written as 13:00 hours. Documentation in this manner reduces the risks of time error through misinterpretation of morning or afternoon timelines. Figure 16.1 illustrates the 24-hour clock.

Effective nursing documentation

Jefferies and colleagues (2010a) identify seven critical themes for effective nursing documentation:

Theme 1

Nursing documentation should be client centred. This means that the client’s own perception of their condition and their response to care should be the basis of nursing documentation.

Theme 2

Nursing documentation must contain the actual work of nurses, including education and psychosocial support; for example, the nurse ‘supervised client performing blood sugar level check. Client continues to require instruction to clean finger prior to finger stick’.

Theme 3

Nursing documentation is written to reflect the objective clinical judgment of the nurse; for example, do not write ‘the client appears to be asleep’, write ‘when observed the client was asleep’. Nurses working in rehabilitation and aged care, when documenting functional activities, should also document the burden of care (Hentschke 2009). (See Clinical Interest Box 16.3.) The nurse should accurately describe how nursing care has contributed to the outcome for the client; use of the following words can aid in demonstrating the relevance of nursing care:

• Assist can be used when the client is unable to perform a task independently

• Instruct can be used when a client is able, but not knowledgeable and needs to be taught how to do something

• Monitor/supervise can be used for a client who is impulsive in undertaking a task that is not safe for them to undertake independently.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.3 Examples of documentation of delivery of care in rehabilitation practice

‘Nurse provided instruction to client to ambulate in room to increase activity tolerance.’

‘Client instructed to call for assistance if feels weak/unbalanced.’

‘As recommended by physiotherapist, nurse instructed and supervised client in using walker to facilitate and promote independence.’

‘Nurse instructed client to place feet flat on the ground before attempting transfer.’

‘To maintain skin integrity, the client/family require assistance with turning for pressure relief.’

‘Client complains of fatigue after therapy and has difficulty removing pants independently. Nurse instructed client to use the electric bed to sit up and the reacher device to facilitate reaching lower legs. With these instructions, client can remove clothing, but it takes him a little longer than normal.’

Theme 5

Nursing documentation should be written as events occur; this is described as contemporaneous documentation. Documenting events as they occur guarantees that important information about the client’s condition and care is not forgotten as subsequent events take place. In the event of a deposition or trial, your testimony should be based on primarily on the information provided in the client’s health record (see Clinical Scenario Box 16.1). You may testify regarding undocumented care provided, but your credibility can be compromised if what you did or said you did is not accurately documented in the client’s health record.

Clinical Scenario Box 16.1

Coroner’s investigation into the death of Keiran Daragah Watmore, Albany 2009

‘At about 2 am his oxygen saturation rate was 88% on room air. As this was low, I put him on oxygen through nasal prongs and later mentioned I had done so to one of the registered nurses. About half an hour after I had connected up the oxygen, I checked his oxygen saturation level and it was up to 98%’.

In evidence Nurse F was asked to which of the registered nurses she had mentioned the low oxygen saturation level. She stated that she could not recall which one it was and that it might have been both of them. Nurse F was asked whether or not the nurse she spoke to had said anything to her in response, to which she said, ‘I can’t recall them saying anything, no’. She stated that she did not make any entry in the notes recording this conversation or recording the observations which she claimed indicated that the oxygen saturation level had gone up to 98%. Coroner Hope states that ‘in my view Nurse F’s account in respect of this matter was inconsistent and unconvincing.’

Theme 7

Nursing documentation should fulfil legal requirements. Documentation demonstrates that the nurse has applied nursing knowledge, skills and judgment in their care of the client or client group. The nurse’s documentation may be used in evidence in coroners’ investigations, disciplinary hearings and lawsuits. A summary of the legal requirements that might be necessary for nursing documentation is outlined in Clinical Interest Box 16.4.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.4 Nurse practice guideline: legal requirements

Nursing documentation meets legal requirements when the following are present:

• Correctly identifiable with the client’s details: full name, date of birth and gender

• Facts recorded, i.e. what you observe, hear, smell and touch

• Charted in chronological order, using the 24-hour clock

• The signature, name and designation of the nurse included in the episode of care

• Incorrect records are not be obliterated. A line is drawn through the entry and the entry is initialled by the nurse, before the nurse continues. The use of items like corrective fluid to obliterate an entry diminishes the credibility of the record

• Only care that has been personally delivered is documented, except in an emergency situation such as cardiac arrest, in which case a designated recorder of all treatment is identified

• Use of abbreviations is minimised and only those abbreviations authorised by the organisation are used

• Gaps within text are filled with a single line, to prevent additional information being added later

• Late entry of pertinent information is prefixed by the words ‘late entry’ and includes the date and time of the entry, as well as the date and time of the information it is referring to

• The organisation’s policy for maintaining accountability in the healthcare records is observed by countersigning unregistered healthcare workers’ or student nurse entries

• Incidents are factually documented in the healthcare record.

Documentation formats

The various types of records that may be used by a healthcare agency include:

• Nursing and medical admission histories

• Progress notes/integrated notes

• Laboratory/diagnostic test reports

• Preoperative anaesthetic records and postoperative surgical reports

The nurse is most likely to be regularly involved in recording information on client interview forms, nursing care plans, various flow charts and progress notes.

Narrative documentation

For a narrative report the nurse charts in chronological order the events that occur, including the gathering of information. The format is generally story-like, and is often repetitive and long.

There are a number of other methodologies that the nurse may apply to construct a logical order to documentation.

Subjective data, Objective data, Assessment and Plan

SOAP is an acronym for Subjective data, Objective data, Assessment and Plan; however, some nurses use an amended format of SOAPIE in which Implementation and Evaluation have been added.

Assessment, Plan, Implementation and Evaluation (APIE)

APIE is a method in which the nurse will document Assessment, Plan, Implementation and Evaluation. The subjective and objective data have been combined in Assessment, while combining what nurses do with the expected outcomes of client care forms the Plan component.

Problems, Intervention and Evaluation (PIE)

PIE is an acronym for Problems, Intervention and Evaluation of nursing care. When the nursing assessment is undertaken, a client problem list is developed with each client problem being allocated a number. The charting is documented using the numbering system, by client Problem, followed by the nursing Intervention that is delivered in relation to the identified problem and the Evaluation of nursing care to resolve or improve the client problem.

Flow sheets

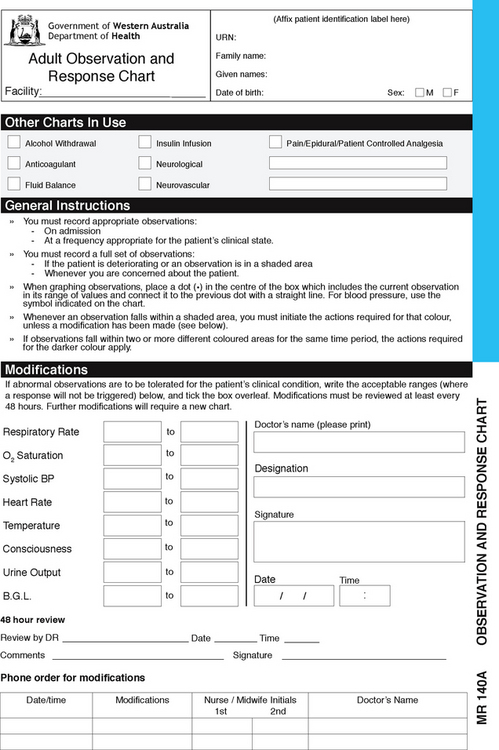

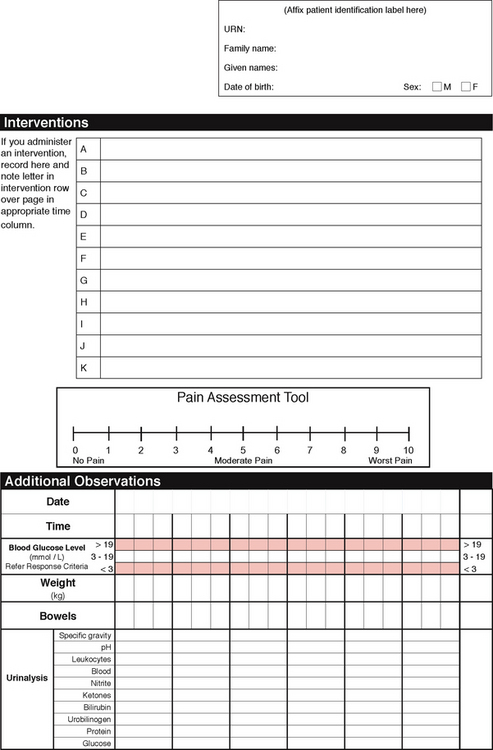

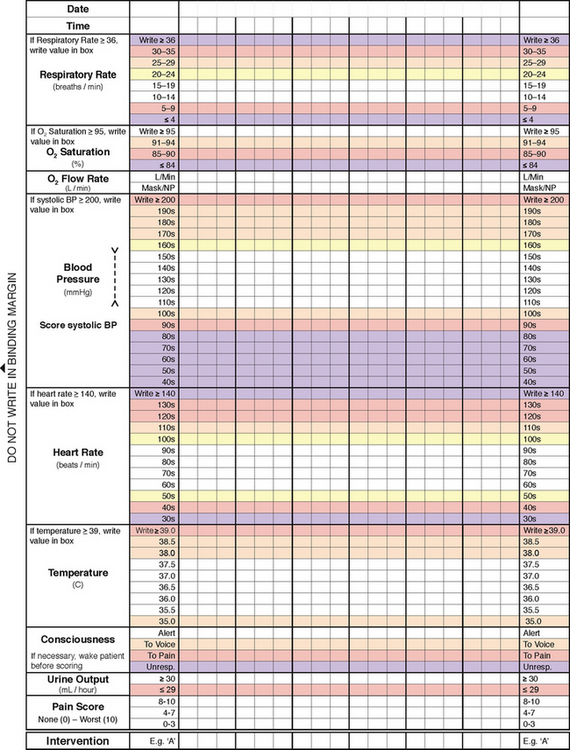

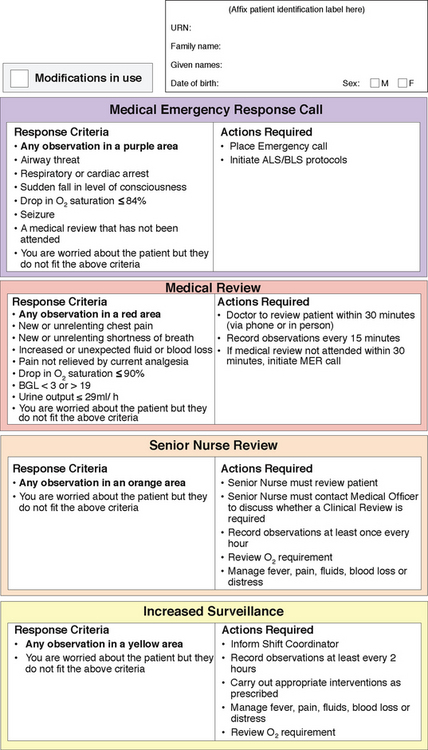

Flow sheets are graphical records to reflect the client’s condition. They enable the nurse to document routine care such as the client’s vital signs, medications, fluid intake and output. More recently, flow charts have evolved for physiological monitoring into ‘track and trigger’ charts. These charts prompt the nurse to graphically chart the client’s observations (track) and when abnormal parameters are reached, a prescribed response or escalation plan is documented and expected of the nurse (trigger) (see Fig 16.2).

Focus charting

Focus charting is used when a patient-centred problem is identified. The identified problem will be commented on during each shift until incorporated into routine management. The method of organising the narrative in focus charting is the principle: Data, Action and Response (DAR). Data reflects a combination of subjective (what the client states) and objective (what the nurse observes), Action is the documentation reflecting what nursing actions were taken to address the problem and Response is the client’s response to the nursing action (see Clinical Interest Box 16.5).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.5 Focus reporting

Nursing 20/01/2013 11:30 hours

Mobility: Client found sitting up on floor against bedside locker by myself at 11:10 hours. Client stated she climbed over the bed rails and fell on the floor, hitting head on bedside table. Client disorientated to time and place (normal for client). Swelling to left temporal area of skull, skin remains intact. Painful to touch, client complaining of headache rated at 3/10. Vital signs within normal parameters. Client not complaining of pain elsewhere. Client returned to bed by staff, bed rails down. Resident medical officer contacted at 11:20 hours to review client, instructed to commence 4/24 full neurological observations. Falls risk management tool completed. Falls prevention strategies implemented as per nursing care plan. Braden Score reassessed at 15, all strategies implemented and charted as per pressure ulcer risk assessment and minimisation. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) 14. Signature, designation and print surname.

Nursing 20/01/2013 17:00 hours

Observations: GCS 12, client agitated, confused and incontinent of urine. Resident medical officer informed, full neurological observations now 30 minutely as instructed. After hours nurse manager contacted at 16:45 hours. Behavioural observation form commenced and client care assistant companion now in place. Client awaiting cranial CT. Family notified. Signature, designation and print surname.

Care pathways

A care pathway is a document outlining a standardised, evidence-based multidisciplinary management plan, which identifies the appropriate sequence of clinical interventions, timeframes, milestones and expected outcomes for a common client group. Care pathways identify the expected course of events for the majority of clients (approximately 70%). As there will always be exceptions, the pathway should be followed in accordance with the nurse’s assessment of each individual case. A process for charting by exception should be in place. Charting by exception involves the nurse charting only significant findings or exceptions to the standards or norms of the predicted care pathway for the client.

Computerised documentation and charting

Computerised documentation is data entry of client information onto a computerised system. This may occur through keyboard, touch screen or voice-activated data entry. The advantages of computerised documentation include:

• information is always legible

• abbreviations can be restricted to agency-approved abbreviations

• each field of a form needs to be completed before the nurse can progress to the next

• client identifying information is automatically generated with each page

• the addition of drop-down boxes creates standardisation and can reduce data entry time for the nurse

• automatic storing of access numbers to individual staff and logging of date and times assists with information integrity.

To ensure contemporaneous recording of information bedside data entry options are essential, which may be fixed or computers on wheels (COW). Additional confidentiality considerations include orientating the computer screens away from public view; use of automatic timed screen savers and logout mechanisms; assigning individual access numbers and passwords; restricting levels of client data to authorised groups of staff; automatic storing of date, time and access numbers when client records are accessed; and encrypting client information transmitted through the internet.

REPORTING

The two main uses of verbal reporting are when a nurse transfers care to another healthcare provider and when the nurse recognises and responds to changes in the health and functional status of the client.

Transfer of care

Reporting when transferring care is commonly called handover. It is at this time that the nurse provides a summary of the client’s condition, care plan, interventions and response to interventions for the purpose of transferring the accountability of care for the client to another healthcare provider. Handover record formats can vary slightly, depending on the context of practice.

Bedside nursing handover

Bedside nursing handover involves the nursing team and the client and/or their family. Nurses have recognised that bedside handover facilitates more accurate information exchange and provides nurses with the opportunity to work in partnership with their clients (Chaboyer et al 2008). Not only has the introduction of bedside handover not extended the time taken for handover (a commonly cited barrier to implemenatation), it has improved the comprehensiveness, visualisation and identification of care priorities.

Legitimate concerns relating to client privacy and confidentiality are managed through organisational policy, which outlines what information is to be conveyed at the bedside handover—particularly important in shared rooms.

Client groups that may not participate in handover include those who are:

Sensitive information that may be shared away from the bedside includes blood tests of a diagnostic nature (e.g. HIV positive, pregnancy); communicable disease information (e.g. hepatitis); psychiatric issues (e.g. thoughts of self-harm, ethanol abuse); not for resuscitation orders; some family issues (e.g. conflicts, domestic violence); other information the client may wish to be held in confidence.

Clinical Interest Box 16.6 is a sample of a standard operating protocol for implementing bedside handover in nursing.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.6 Bedside handover

(Chaboyer et al 2008:15–16)

(Chaboyer et al 2008:15–16)

Reporting changes in client condition

The mechanism for nurses to report changes in the health and functional status of the client will be determined by the:

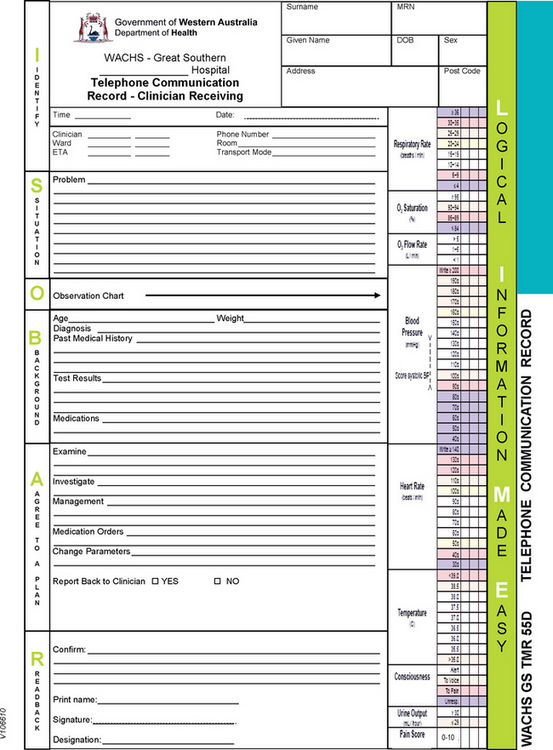

Telephone reports

Nurses are required to communicate client information through telephone reporting in a variety of contexts, from conveying a laboratory result to a hospital doctor to conveying complex assessment and treatment information to a medical officer at a remote site. The minimum data set for client handover includes identification of the nurse and client, situation and status of the client, observations, background and history, assessment and actions and responsibility and risk management (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2009) (see Fig 16.3).

Figure 16.3 Telephone communication record

(Sample chart. Telephone Communication Record: Medical Emergency Response Call. WA Country Health Service)

Most organisational policy and procedure will include the requirement for the nurse to read back and confirm the therapy or plan prescribed by the medical officer. When medications are ordered, this may include a repeating of the medication order to a second nurse, who will also be required to read back to confirm the order.

Incident reporting

Healthcare facilities have policies in place that require nurses to complete an incident form following a near miss or an incident such as a medication error or fall. These incident reports are confidential documents and are filed separately from the client’s health record. Regardless of whether incident reports are used, nurses have a professional accountability to document the facts of the care provided to the client and the outcome for the client (see Clinical Interest Box 16.7).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 16.7 Reporting a clinical incident in the client’s health record

A medical officer prescribes morphine 10 mg orally and you mistakenly administer 15 mg. Your medical record documentation should read like this:

08/01/2013 1430 hours. Administered morphine 15 mg orally at 13:00 hours for abdominal pain, which the client rated at 7/10. Dr Smith notified of above dose at 13:15 hours and gave no additional orders. Client’s observations increased in frequency to every 30 minutes for 4 hours, vital signs have remained within normal parameters at time of report. Client rates pain as 1/10. Name of Nurse, Nurse Designation.

Computer-assisted documentation

Computer-assisted documentation includes the implementation of advanced speech-recognition technology (voice recognition programs) to increase the quality and accuracy of transcribed documents and reduce the turnaround for clinical notes and the cost of medical transcription processes (Rozmus 2010). In nursing services voice recognition programs may improve efficiency and access to records, particularly in nurse-led clinic environments and emergency departments when timely discharge information is required.

Summary

Nurses provide 24-hour care; therefore, information exchange, whether verbal or documented, is a significant part of nurse activity and must be reliable. Through documentation the nurse communicates to other nurses and the healthcare team their assessment of the status of the client, the nursing interventions that were carried out and the outcome of these interventions.

Client records are kept for a number of purposes, including communication, research and quality activities, funding arrangements, legal documentation and healthcare analysis.

The two main uses of verbal reporting by a nurse are when a nurse is transferring care to another healthcare provider and when the nurse recognises and responds to changes in the health and functional status of the client.

The healthcare record is a legal document; it includes paper documents or electronic documents such as faxes, emails, audio or images (including video or digital images). Legislation governs the privacy and confidentiality of the healthcare record.

All information relating to the client’s healthcare is gathered by subjective or objective methods. Any change in a client’s condition requires immediate documentation of the nurse assessment, nurse actions and the client’s response to the nursing interventions.

1. Mrs K is a 76-year-old female admitted with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Vital signs are as follows: blood pressure 90/60 mmHg; pulse rate 48 beats per minute; respirations 24 breaths per minute; temperature 38ºC.

During your initial assessment she complains of feeling breathless and dizzy with the smallest amount of exertion. Her lungs have crackles in both bases and she has peripheral oedema. Mrs K normally takes a beta-blocker for hypertension. Differentiate between the objective and subjective data.

2. Mr Z had a right hemicolectomy for cancer of the ascending colon today. He returned to the ward with oxygen 6 L/min via simple mask maintaining oxygen saturations at 98%. Intravenous 1 L 0.9% sodium chloride infusing at 80 mL/hr. Tolerating ice only orally. Client controlled analgesia in situ. Indwelling urinary catheter output 50 mL/hr. Varivac × 1 in situ with 100 mL of haemoserous fluid drained. Dressing intact, clean and dry. Vital signs: blood pressure 120/84 mmHg; respiratory rate 14 breaths per minute; heart rate 88 beats per minute. Use this information to write a nursing progress note using the following formats: SOAPIE, PIE, DAR.

3. Mr S is a 76-year-old man admitted with chest pain. You have responded to his call bell in which he states that he has severe chest pain, radiating down his left arm. The pain began after he returned from the toilet. Vital signs: blood pressure 170/90 mmHg; respiratory rate 26 breaths per minute; heart rate 109 beats per minute; pain score 8/10; oxygen saturations 98% on room air. Document the observations on the observation chart, document your interventions based on the action plan and document what verbal report you would provide to the medical officer.

References and Recommended Reading

Austin S. Ladies & gentleman of the jury, I present … the nursing documentation. Nursing. 2006;36(1):56–63. Online. Available: www.nursingcenter.com/prodev/ce_article.asp?tid=622257

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. The OSSIE Guide to Clinical Handover Improvement. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2009.

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council. National Competency Standards for the Enrolled Nurse. Australia: ANMC, ACT, 2002.

Blair W, Smith B. Nursing documentation: frameworks and barriers. Contemporary Nurse. 41(2), 2012. Online Available: www.contemporarynurse.com/archives/references/4549

Chaboyer W, McMurray A, Wallis M, et al. Standard Operating Protocol for Implementing Bedside Handover in Nursing. Brisbane: Griffith University, 2008.

Corexcel. (nd) The Best Defense Is a Good Documentation Offense. Online. Available: www.corexcel.com/courses/documentation.title.htm.

Gagan MJ. The SOAP format enhances communication: the SOAP format provides a clear and concise way of documenting client information, Life and Health Library. Online. Available: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb4839/is_5_15/ai_n32108005/, 2009.

Gjevjon ER, Helleso R. The quality of home care nurses’ documentation in new electronic client records. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:100–108.

Hentschke P. 24-hour rehabilitation nursing: the proof is in the documentation. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2009;34(3):128–132.

ImpactEDnurse.com. A Nursing Documentation Template. Online. Available: www.impactednurse.com/?p=1363, 2009.

Jefferies D, Johnson M, Griffiths R. A meta-study of the essentials of quality nursing documentation. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2010;16:112–124.

Jefferies D, Johnson M, Griffiths R, et al. Engaging clinicians in evidence-based policy development: The case of nursing documentation. Contemporary Nurse. 2010;35(2):254–264.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Evidence Summaries—Nursing Record Systems/Documentation. Adelaide: JBI, 2011.

McGain F, Cretikos MA, Jones D, et al. Documentation of clinical review and vital signs after major surgery. Medical Journal of Australia. 2008;189(7):380–383.

New Zealand Nurses Organisation. Guidelines for Nurses and Midwives, Privacy, Confidentiality and Consent in the Use of Exemplars of Practice and Journaling. Online. Available: www.nzno.org.nz/services/resources/publications, 2005.

New Zealand Nurses Organisation. Documentation. Online. Available: www.nzno.org.nz/Portals/0/publications/Documentation,%202010(final).pdf, 2010.

Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ). Competencies for the Enrolled Nurse Scope of Practice. Wellington: NCNZ, 2010.

Porteous JM, Stewart-Wayne EG, Connolly M, et al. ISoBAR—a concept and handover checklist: the National Clinical Handover Initiative. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009;190(11):S152–S156.

Royal College of Nursing Australia (2011) Nursing services not to be lost in rhetoric. Media release, 14 February.

Rozmus M. Transcription makeover. Health Management Technology. 2010;31(8):20–21.