CHAPTER 20 Infection prevention and control

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• Discuss the nature of infection

• Explain the links in the chain of infection

• Describe the body’s normal defences against infection

• Identify factors that increase susceptibility to infection

• Differentiate between and discuss standard and transmission-based precautions

• Explain nursing responsibilities in relation to preventing transmission of infection

• Identify interventions to reduce risks for infection

• Name the sequence for donning and doffing PPE

• Identify measures that break the chain of infection

• Explain the National Hand Hygiene Initiative ‘The 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene’

• Define the concepts of standard and surgical asepsis

• Demonstrate recommended and approved infection control techniques when carrying out nursing activities

• Describe the steps to take in the event of a blood-borne pathogen exposure

Effective infection prevention and control is essential to providing high quality healthcare for clients and a safe working environment for those who work in and visit the healthcare setting. Infection prevention and control is everybody’s business. Knowledge and understanding of the modes of transmission of infectious organisms and when to apply the basic principles of infection prevention and control is critical to the success of any evidence-based infection control program.

Infectious diseases have not disappeared with advances in drug and medical therapy, and in some cases microorganisms have developed drug-resistant strains. Control and prevention of infection is an essential component of every nursing activity. Nurses require knowledge about microorganisms, the infectious process and the application of infection control principles to their daily activities to prevent the spread of microorganisms. This knowledge helps nurses to minimise the incidence of infection and the spread of infection between clients, and to protect themselves and other healthcare workers from contact with infectious material or exposure to communicable diseases. Nurses are also in a prime position to educate their clients about activities that increase personal resistance to infection, modes of transmission and prevention methods to assist in controlling the spread of infection in the home as well as in the healthcare facility.

Clients in healthcare settings are at risk of acquiring infections because of lowered resistance and increased exposure to disease-causing microorganisms, and invasive procedures. Sources of infecting microorganisms can be people or environmental objects, such as medical or nursing equipment that has become contaminated.

Recently during a hand hygiene education session I was shocked to see how badly I had washed my hands. I was asked to rub a special cream into my hands; once it was all soaked in, I was then asked to wash my hands with soap and water using the same technique that I would use for a social wash. On completion of this my hands were looked at under a black light. I was shocked to see that all around my nails and the backs of my fingers were glowing white. I bite my nails and I was able to actually see potentially how dirty my fingers and nails are when I put them in my mouth after having washed them. I am never going to bite my nails again. Now I see why hand hygiene technique is so important.

HEALTHCARE-ASSOCIATED INFECTION IS PREVENTABLE

There are about 200 000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in Australian acute healthcare facilities each year. Healthcare-associated infections (‘nosocomial’) are classified as infections that are associated with the delivery of healthcare services in a healthcare facility or healthcare interventions (‘iatrogenic’). The infection can occur during admission or may manifest after discharge. As well as causing unnecessary pain and suffering to clients and their families, these adverse events prolong hospital stays and are costly to the health system. The most common settings where HAIs develop are hospital surgical or medical intensive care units. However, HAIs can occur in any healthcare facility and all healthcare workers have a duty of care to take all reasonable steps to safeguard clients, staff and the general public from infection. The microorganisms that cause hospital-acquired infections can originate from the client themselves (an endogenous infection) or from the hospital environment, personnel or from other clients via the hands of healthcare workers (exogenous infection).

NATURE OF INFECTION

An infection is a state that exists when microorganisms have gained entry and have multiplied in the tissues of a host, causing damage to cells or tissues, resulting in either localised or systemic injury. The microorganisms that are capable of causing disease are referred to as pathogens. The presence of a pathogen does not always result in an infection.

If the infectious agent fails to cause injury and the client has no signs and symptoms of infection the infection is said to be asymptomatic. If the pathogens multiply and cause clinical signs and symptoms, such as pain, high temperature or lethargy, the infection is said to be symptomatic. If the infectious pathogen can be transmitted to an individual by direct or indirect contact or as an airborne infection, the resulting condition is known as a communicable disease. Virulence is a term used to describe the pathogenicity of an organism or, in other words, the extent to which it is capable of causing disease. The potential for microorganisms to cause disease depends on virulence, a sufficient number of organisms being present and their ability to enter and survive in the host. An opportunistic pathogen causes disease only in a susceptible individual. Infectious diseases are a major cause of death worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) is the major regulatory body at an international level. In Australia, the Communicable Disease Network Australia (CDNA) provides national public health leadership and coordination on communicable disease surveillance, prevention and control. It also provides strategic advice to government and other key bodies on public health actions.

MICROOGANISMS

Microorganisms are forms of animal or plant life too small to be seen without the aid of a microscope. One of three events occurs when microorganisms invade the body. They are destroyed by the body’s immune defence mechanisms, they stay within the body without causing disease or they cause infection or infectious disease.

Distribution of microorganisms

Microorganisms are found in every situation where it is possible for life to exist. Microorganisms are present in air, water, soil, dust, in and on food, on every surface and in and on the bodies of living organisms, including human beings. Microorganisms may be pathogenic or non-pathogenic. Non-pathogenic microorganisms do not cause disease under normal circumstances or when in their normal environment. Those that normally reside on or in the human body and cause no harm are termed the body’s normal flora. Normal flora defends the body by curbing invasion by pathogenic microorganisms. For example, Escherichia coli bacteria are microorganisms that normally reside in the human gastrointestinal tract and under normal circumstances cause no ill effects.

Clinical note: Following a course of broad spectrum antibiotics the Escherichia coli numbers are reduced; this then gives Clostridium difficile bacteria the chance to become prolific causing the client severe diarrhoea. If this microorganism is transferred to another area of the body, for example to the renal system, it will cause a urinary tract or kidney infection.

Normal flora is found on the skin, on the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract, in the intestines and in the vagina. Infective pathogens are the organisms that are able to overcome the normal defences of the body, invade the tissues, multiply and produce poisonous substances such as toxins that damage the tissues and cause disease (see Table 20.1).

Table 20.1 Distribution of common residual microorganisms (flora)

| Body areas | Microorganisms | |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | ||

| Nasal passages | Corynebacterium zerosis | |

| Oropharynx | ||

| Mouth | ||

Types of infection

Infections can be localised or systemic. A local infection is limited to a specific part of the body where the microorganisms remain. If and when the microorganisms spread and damage other parts of the body it is known as a systemic infection. A bacteraemia occurs when a blood culture reveals the presence of a microorganism in the blood. When a bacteraemia results in systemic infection, it is referred to as sepsis.

There are also acute and chronic infections. Acute infections generally appear suddenly or last a short time, whereas a chronic infection may occur slowly, over a long period of time, and may last months or years.

Colonisation is the process whereby the microorganisms become resident flora. In this state, the microorganisms may grow and multiply but do not cause any harm or disease to the client. Infection or disease occurs when the microorganisms invade parts of the host’s body where the defence mechanisms are ineffective and cause tissue damage.

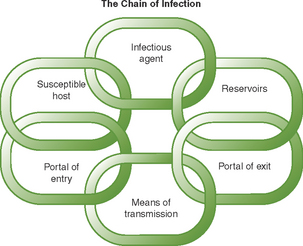

Chain of infection

The development of infection can be thought of as a chain of events. Each event is a link in the chain and must occur sequentially for an infection to develop. The presence of all the following elements is necessary for an infection to occur:

• Pathogenic organisms in sufficient numbers (causative/infectious agent)

• Reservoir where pathogens can reside

• Portal of exit from the reservoir (an escape route)

• Mode of transmission (vehicle to transport to new destination)

• Portal of entry to the new host

• A susceptible new host (See Fig 20.1 and Table 20.2.)

Figure 20.1 The chain of infection. Infection prevention and control is directed towards breaking the links in the chain of infection

(Courtesy of Teresa Lewis)

Table 20.2 Interrupting the chain of infection

| Link in the chain | Objective | Infection control nursing interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Reservoir: | ||

| Portal of exit—body fluids, excreta or other secretions | Prevent contamination | |

| Route of transmission: | Prevent cross-contamination; eliminate vectors | |

| Portal of entry: | Prevent entry of microorganisms into a host | |

| Susceptible host | Improve client resistance to infection; prevent infection |

(Adapted from deWit 2009)

Types of microorganisms/causative pathogenic agent

The major groups of microorganisms are classified according to size, structure and method of reproduction. Microorganisms include bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Bacteria are by far the most common infection-causing microorganism. They are single-celled microscopic organisms without a nucleus that have the capacity to reproduce rapidly. Bacteria make up the largest group of pathogens and are often treated with antibiotics. The advent of antibiotics in the 1940s provided a powerful weapon to treat bacterial infections; however, because bacteria continually mutate as they divide, some had natural resistance to the effects of antibiotics and have developed into resistant strains. These pathogens may include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and multi-resistant gram-negative (MRGN) microorganisms, such as Acinetobacter species. These multi-drug-resistant organisms are dangerous threats, and emphasise the need for nurses and all healthcare workers to practise effective infection prevention and control measures.

Viruses are specialised microorganisms with a number of distinctive characteristics:

• Most are ultramicroscopic, meaning that they are too small to be seen with a light microscope and can be viewed only with an electron microscope

• They have no cell structure and they lack a rigid cell wall

• They are intracellular parasites, meaning that they can grow and reproduce only when living within a host cell, and cannot be cultured on dead or artificial media.

Some of the common viral diseases of concern within the healthcare setting are herpes simplex, hepatitis (A, B and C viruses), influenza and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Fungi are tiny organisms such as moulds and yeasts that belong to the world of plants but contain no chlorophyll. Fungi are present in the soil, air and water and they multiply by producing various kinds of spores. Candida albicans is considered normal flora in the human vagina.

Parasites live on other living organisms. They include Protozoa, which are single-cell organisms of the animal kingdom. The route of entry is usually by ingestion of contaminated water or food, which commonly results in severe diarrhoea. Some protozoans are transmitted by insects (vectors) to man; for example, the plasmodium species, which is carried by mosquitoes and causes malaria. Helminths are parasitic worms, or flukes—multicellular animals that are pathogenic to humans. They are not common in Australia and New Zealand.

Reservoirs (sources) of infection

A reservoir is a place where a pathogen can survive but may or may not multiply. Common reservoirs of pathogenic microorganisms are other humans, the clients’ own microorganisms, animal or inanimate sources. The presence of microorganisms does not always cause a person to be ill. In humans, microorganisms can thrive in reservoirs such as open wounds, blood, nasal passages and skin crevices.

Most organisms that infect humans are acquired from human sources. The entrance of a foreign object or organism into a sterile site leads to a high risk of infection. Endogenous infection occurs when normal flora cause infection by being transferred from their normal place of residence to a different site in the same host. Cross-infection may occur when organisms from one person are transferred to another person; for example, when organisms on a nurse’s hands are transferred to a client’s wound.

Portals of exit from reservoir

If microorganisms are to enter another host and cause disease, they must first find a portal of exit, and then a new site in which to reside. When the human body provides the reservoir, microorganisms can exit through a variety of sites (see Table 20.3).

Table 20.3 Common infectious microorganisms and their portals of exit

| Body area/Reservoir | Examples of common infectious organisms | Portals of exit |

|---|---|---|

| Skin or tissue | Drainage from wound or cut/break in skin | |

| Blood | Needle puncture sites, open wounds, non-intact skin or mucous membrane surfaces | |

| Respiratory tract | Nose or mouth through breathing, coughing, laughing, sneezing or talking | |

| Gastrointestinal tract | ||

| Urinary tract | Urethral meatus |

Modes of transmission

Microorganisms move from a reservoir to a new host in a variety of ways. In a healthcare setting, the main modes of transmission of infectious agents are: contact (including blood-borne), droplet and airborne. In some cases the same organisms can be transmitted by more than one route.

Clinical note: the varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox, can be acquired through inhalation of infected airborne particles (airborne transmission) as well as through contact (contact transmission) with infected fluid leaking from skin lesions.

Contact transmission

Contact is the most common mode of transmission; it may be direct or indirect.

Direct transmission occurs when there is transfer of the infectious agent from one person to another; for example, a client’s blood entering the healthcare worker’s body through a needlestick injury.

Indirect transmission involves the transfer of infectious agent through a contaminated object or person; for example, a healthcare worker’s hands touching an infected body site on one client and the worker not performing hand hygiene before touching another client, or when a healthcare worker comes in contact with fomites (e.g. bedding of a client with scabies).

Clinical note: Some examples of infectious agents transmitted by the contact mode include multi-resistant organisms (MROs), norovirus, Clostridium difficile and highly contagious skin infections such as impetigo and scabies.

Droplet transmission

Droplet transmission occurs when the infected person coughs, talks, sneezes, laughs or during certain procedures. Droplet particles are larger than 5 microns in size. Distribution is limited by the force of expulsion from the infected person and is usually 1 metre. The droplet particles transmit infection when they travel directly from the infected person to a susceptible mucosal surface (nasal, conjunctivae or oral) of another person. However, droplets can be transmitted indirectly to mucosal surfaces (e.g. contaminated hands rubbing eyes or inserted into mouth).

Clinical note: Some examples of infectious agents that are transmitted via the droplet mode include influenza virus, pertussis and meningococcus.

Airborne transmission

Airborne dissemination may occur via tiny particle aerosols created during breathing, coughing, talking or sneezing containing infectious agents that remain infective over time and distance. Certain procedures, such as airway suctioning, endotracheal intubation, diagnostic sputum induction, positive pressure ventilation via face mask and bronchoscopy, can promote airborne transmission. The infective aerosols can be dispersed over long distances by air currents (e.g. ventilation or airconditioning systems) and inhaled by susceptible individuals who have had no contact at all with the infectious person.

Clinical note: Some infectious agents that are transmitted via the airborne mode include varicella virus (chickenpox), Mycobacterium tuberculosis and measles (rubeola).

Other modes of transmission

Transmission of infection can also occur via ingestion of contaminated food, water, medications or other common sources such as contaminated devices or equipment.

Clinical note: It is of great importance that nursing staff be aware of food being brought in to healthcare settings for clients by friends and family. If foods are not maintained at the correct temperature, the risk of food poisoning is very high. Foods of high risk include seafood, shellfish, soft cheeses and meat dishes. Facilities should have policies in place to help manage this (see Box 20.1).

Box 20.1 Bringing food in for clients

Families and friends sometimes bring in food for clients. There can be a risk of food poisoning when food is not properly prepared, transported or stored. This can have serious consequences for the client.

Foods that are safe to bring in to clients

Dry biscuits (Salada, savoy, rice crackers, water crackers …)

Sweet biscuits (Scotch finger, butternut, fruit biscuits …)

Baked products (bread, muffins, bagels, scones, plain cakes …)

Foods that are extremely unsafe and therefore are NOT recommended to bring in for clients. Any foods that can spoil if not refrigerated

Cooked or raw fish, shellfish, oysters

Soft cheeses, deli meats and pâtés

Salads and other items containing dairy products or creamy dressings e.g. coleslaw, potato salad

Sweet dishes and cakes, which contain custard cream or are made from uncooked eggs

Sandwiches with potentially hazardous food fillings (meat, fish, poultry, cheese)

If you are unsure about what food is safe or wish to bring in any of the listed items, please speak to the nursing staff or contact the Food Services Department.

Safe food guidelines

All potentially unsafe food must be properly transported during the journey to protect from contamination. If the food is served chilled or is to be reheated it should be kept cold during transport in an esky or other cooler type container.

If the food is being transported hot, you must ensure that it is kept hot. Hot food is difficult to keep hot and is best avoided if you are travelling long distances. It is best to chill the food overnight and reheat before eating.

Nursing staff must be informed of any food brought in for client consumption.

Any food which is not going to be consumed immediately must be covered, labelled with the client’s name, room number, date and time the food was brought into the hospital and refrigerated within 15 minutes of arriving onto the ward.

Hospital staff will discard all potentially unsafe food that is stored in the fridge and not consumed within 24 hours of being brought into the hospital.

It is essential that clients who are on special diets are not provided with food that has not been approved by the dietitian, nursing or food service management.

Always wash hands thoroughly before preparation and prior to handling food.

Reheat food until it is steaming hot throughout.

Food reheated to above 75°C for two minutes will kill most foodborne bacteria or viruses that can cause illness.

Never reheat food that has been reheated previously.

Please do not offer to share food with other clients.

I have read, understood and accept the risk associated with consuming food brought into this hospital from an external source.

For more information visit NSW Food Authority http://www.foodauthority.nsw.gov.au

Variant Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease (vCJD) is a disease that emerged in the UK in the 1990s. vCJD is linked to the consumption of meat products from cattle infected with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or ‘mad cow disease’). Variant CJD is a separate disease to classical Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (CJD) although some of the symptoms are similar. vCJD typically affects people at about age 30. The link between vCJD and ingestion of infected meat was discovered when 23 people living in Britain contracted CJD in the mid-1990s, about 10 years after the epidemic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy that occurred in the country from 1984 to 1986. No cases of variant CJD have been identified in Australia or New Zealand to date. Australian and New Zealand cattle remain free of BSE.

Vector-borne transmission (via mosquitoes, flies, rats and other animals) as a health concern is not as significant in Australia and New Zealand as it is in other parts of the world. However, in recent times there has been some increase in concern about transmission of Murray Valley encephalitis (MVE) and dengue fever in Victoria, western New South Wales and Far North Queensland. Examples of microorganisms spread by this mode in other parts of the world are Plasmodium falciparum (malaria) and Yersinia pestis (plague).

Portals of entry

Before a person can become infected, microorganisms must enter the body. Microorganisms can enter the body through the same routes they use for exiting:

• Inhalation into the respiratory tract

• Ingestion through the mouth into the alimentary canal

• Inoculation through the skin or mucous membrane, which can occur when the skin becomes cracked or when tissue integrity is disturbed during injury, surgical procedures, injections, bites or stings

• Transplacental entry occurs when organisms from a pregnant woman cross the placenta to enter the fetal circulation (e.g. toxoplasmosis).

Clinical note: Measures that control the exit of microorganisms also control the entrance of pathogens, for example:

• Maintaining skin and mucous-membrane integrity

• Correct handling of urinary catheters and drainage sets

• Cleansing the genital area in a direction away from the urinary meatus to the rectum

• Implementing aseptic techniques, using sterile equipment during invasive procedures

• Cleansing wounds outwards from the wound site, to prevent the entrance of microorganisms.

Host susceptibility

Susceptibility is the degree of resistance an individual has to invading pathogens. Whether a person acquires an infection depends on their susceptibility to the infectious agent. A susceptible host is the last link in the chain of infection.

Clinical note: Factors which increase susceptibility of a person to infection are: age (the very young or old), clients receiving immunosuppressive treatment for cancer, chronic illness or following an organ transplant, and those with immune deficiency conditions. Susceptibility to infection can be reduced by lifestyle practices that boost resistance, such as healthy nutrition, adequate exercise, rest and sleep, stress-management activities and effective hygiene practices (see Clinical Interest Box 20.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 20.1 General factors increasing susceptibility to infection

Resistance to infection

The body has certain natural resources that give a degree of resistance against infection. It has two main lines of resistance to infection: non-specific defences and a specific immune response. Non-specific defences are those that defend naturally against any invading organism or foreign matter. Such defence is also known as innate immunity, present at birth. It does not recognise specific microbes; it fights off all invading organisms in the same way. It provides us with rapid responses to protect against disease. These defences can be divided into two categories, external and internal. External physical barriers include intact skin, mucous membranes, normal body flora and some body secretions, for example, sweat, sebum, saliva and tears. Internal defences are the automatic protective actions of the inflammatory process, phagocytic cells, ‘natural killer’ cells and protective proteins. Inflammation is a localised and non-specific response of the tissues to an injury or infectious agent. It helps prevent further spread of injury, dilutes or destroys the injuring agent and promotes healing and repair of the injured tissues. It is characterised by five signs: pain, swelling, redness, heat and impaired function of the body part if injury is severe.

Specific defences defend against specific foreign agents or antigens, such as a specific bacterium, virus, pollen or toxins, once it has broken through the innate immunity defences. This defence is also known as adaptive immunity. Having immunity means being resistant to, or being unaffected by, a particular infectious disease. It means that a specific antibody has been produced to defend the body against a specific pathogen or the toxin it produces (the antigen). The body’s immune responses are under the control of the lymphatic system. It is a highly efficient system that responds very specifically to the threat of infection. It is made up of lymph, lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, red bone marrow, the thymus gland, spleen and tonsils.

Lymphocytes are the most significant cells in the body’s immune responses. There are two categories of lymphocytes involved in the specific immune response: T-lymphocytes (T-cells) and B-lymphocytes (B-cells).

To function effectively in defending the body from invading organisms, these defence responses must be able to distinguish between the body’s own cells and foreign agents. Malfunction of a person’s immune system can cause a failure to recognise cells that belong to the self. This results in damage or destruction of ‘self’ cells. An attack on the body’s own cells is the basis of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile-onset (type 1) diabetes mellitus, pernicious anaemia, multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus (see Table 20.4).

| Type | Antigen or antibody source | Duration of immunity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Active | Antibodies are produced by the body in response to an antigen | Long |

| a Natural | Antibodies are formed in the presence of active infection in body | Lifelong |

| b Artificial | Antigens (vaccines or toxoids) are administered to stimulate antibody production. | Many years but may need to be boosted |

| 2 Passive | Antibodies are produced by another source, animal or human | Short |

| a Natural | Antibodies transferred naturally from mother to baby (placenta) | 6–12 months |

| b Artificial | Immune serum from another animal or human is injected | 2–3 weeks |

Factors influencing susceptibility to infection

In a healthcare setting there are several factors that influence the individual’s outcome after exposure to a pathogenic organism:

• Their immune status at time of exposure

• Age (neonates and the elderly are more susceptible) (See Table 20.5 and Clinical Interest Box 20.2.) (Clinical note: First-line defence consists of intact skin, mucous membranes and their secretions. Skin becomes very fragile with age; care must be taken to protect the aged client. Naturally acquired passive immunity involves the natural transfer of antibodies from a mother to her baby. These antibodies are transferred via the placenta or the mother’s milk, especially the first milk, called colostrum. This immunity lasts only a few weeks or months, covering the baby until its immune system matures. An example of this is if the mother is immune to polio or rubella the baby is also. Care must be taken to protect the neonate from exposure to infection.)

• Health status, history or comorbidities (Clinical note: Diabetes can slow the body’s ability to fight infection.)

• Nutritional status (poor nutrition can slow the body’s ability to fight infection)

• Wounds, indwelling devices and length of stay in healthcare facility

Table 20.5 Factors that increase susceptibility to infection in older adults

| The normal changes of ageing means that older adults are at higher risk of infection than younger adults. Any illness experienced by an older adult increases the risk because it places increased demands on the body and a strain on its natural defence mechanisms. Nursing interventions aim to decrease this risk. |

Adapted from deWit 2009

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 20.2 Older adults and infection

• Older adults should be immunised annually against influenza

• Circulatory changes related to congestive heart failure and calcified mitral and aortic valves mean that older adults with these conditions are prone to pneumonia and bacterial endocarditis

• Older adults or other clients who are cognitively impaired often need special help with infection control measures (e.g. prompting to wash their hands at appropriate times)

• Symptoms of infections in older adults are often manifested as increased confusion or other changes in behaviour such as tearfulness or irritability. They may no longer have the ability to communicate their discomfort or to tell you about their symptoms verbally

An important component of nursing practice is assessing every client for existing infection or the potential for contracting an infection. There are some medical and drug therapies, such as corticosteroid medications or chemotherapy, which compromise immunity to infection. Nursing assessment of the client’s history to determine if there is an increased susceptibility to infection related to any medications or treatments is important. Clinical Interest Box 20.3 illustrates several questions that could be considered.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 20.3 Nursing assessment of client on admission

• What infections have you had in the past and how were they treated?

• Have any of these infections reoccurred?

• Are you currently taking or recently taken any antibiotics, anti-inflammatory, anti-coagulant medications?

• What past surgeries have you had?

• Did you have any complications following your last surgery?

• How would you describe your eating habits?

• Do you have any wounds or broken skin?

• Have you had any recent diagnostic procedures or therapy through your skin or a body cavity?

• Have you had any recent admissions in a healthcare facility and how long were you in hospital?

• Have you recently experienced any loss of energy, loss of appetite, nausea or vomiting?

Infection prevention and control through staff health and safety

Not only do we concern ourselves with minimising the risk of acquiring infection for our clients we must also protect the staff. In the course of their duties, healthcare workers can be exposed to infectious agents (through direct contact with infectious client, visitors or colleagues, or indirectly with contaminated surfaces and equipment, as well as through the result of a sharps injury). Healthcare workers can also place clients at risk of transmission of infection if they have an infectious condition that is capable of being transmitted to the client as they perform their duties.

All employers and employees have a responsibility in relation to infection prevention and control and occupational health and safety. While the organisation has a duty of care to healthcare workers, staff members also have a responsibility to protect themselves and to not put others at risk.

As part of the infection control and prevention program each facility should develop, implement and document effective policies and procedures related to staff health and safety, including strategies to prevent occupational exposures to infectious hazards, chemical safety, and staff immunisation programs. Employers should take all reasonable steps to ensure that staff are protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. The most recent edition of The Australian Immunisation Handbook (NHMRC 2008) provides detailed information on immunisation schedules and vaccines. Table 20.6 has been adapted from the Australian Immunisation Handbook (2008).

Table 20.6 Recommended vaccination for all healthcare workers

| All healthcare workers directly involved in client care or the handling of human tissues | |

| All healthcare workers who work with remote Indigenous communities in NT, QLD, SA and WA; medical, dental and nursing undergraduates (in some jurisdictions) | |

| Healthcare workers who may be at high risk of exposure to drug-resistant cases of tuberculosis |

INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL IN PRACTICE

The risk of transmitting healthcare-associated infections or infectious disease among clients is high. When a client has a suspected or known infection, healthcare workers follow infection control practices. However, there are many situations where the healthcare worker is not aware that clients have infections, as the majority of healthcare-associated infections are found in the colonised blood and body fluids of clients.

In 1996, the Infection Control Working Party of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia recommended adoption of the term ‘standard precautions’ as the minimum requirement in work practices to promote infection control and prevention. ‘Additional precautions’, now known as ‘transmission-based precautions’, are advised where standard precautions are not sufficient on their own to prevent transmission of infection. This two-tiered approach reflects disease transmission and is how infection prevention and control principles should be viewed. The Ministry of Health in New Zealand adopts this same two-tiered approach to infection control and prevention (see Table 20.7).

Table 20.7 Standard and transmission-based precautions for infection control: main points

| Transmission-based precautions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of transmission | Protection | Example |

| Airborne | Negative pressure room or private room with door closed; use of P2 or N95 mask, surgical mask for client if transported. Gloves and gowns as per standard precautions. Restrict visitor numbers and precautions as for staff. | Varicella (chickenpox), measles, TB, SARS |

| Droplet | Private room or cohort; use of surgical mask; mask for client if transported. Gloves and gowns as per standard precautions. | Influenza, rubella, pertussis, mumps, norovirus, meningococcus, respiratory syncytial virus |

| Contact | Private room or cohort; gloves for direct client or environmental contact; gowns for direct contact or splashing. Surgical mask required if infectious agent is isolated in sputum. Eye protection as required per standard precautions | MROs, Clostridium difflcile, Shigella, acute diarrhoea, scabies, highly contagious skin infections |

Standard precautions and transmission-based precautions

The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare (NHMRC 2010) are the national guidelines for infection control and prevention for healthcare settings. Standard precautions are the basic recommended work practices to be implemented in the treatment and care of all clients regardless of diagnosis or perceived infectious risk. Standard precautions are the first tier in a two-tiered approach to infection control. It is a first-line approach, a primary strategy that minimises the risk of transmission of infectious agents from person to person, even in high-risk situations.

Tier 1: standard precautions

Standard precautions relate to:

• Personal hygiene practices, particularly effective hand hygiene, before and after every episode of client contact

• Use of personal protective equipment such as gloves, gowns, plastic aprons, masks/face-shields or eye protection when appropriate

• Appropriate handling and disposal of sharps

• Implementation of environmental controls including cleaning and spills management

• Appropriate reprocessing of reusable equipment and instruments

Standard precautions should be used in the safe handling of blood (including dried blood) and all other body substances, secretions and excretions (excluding sweat) regardless of whether or not they contain visible blood, and the safe handling of non-intact skin and mucous membranes.

Standard precautions are all that is required for clients with blood-borne viruses such as HIV, hepatitis B or hepatitis C unless other factors indicate it necessary, such as the presence of an additional highly transmissible disorder, for example, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB).

Implementing standard precautions

In applying standard and transmission-based precautions as part of day-to-day practice, healthcare workers should ensure that their clients understand why certain practices are being undertaken, and that these practices are in place to protect everyone from the risk of infection. Clients and visitors should also be aware of their role in minimising risks by following basic hand hygiene, cough etiquette and respiratory hygiene, and informing staff about aspects of their history if necessary (e.g. known MRSA colonisation).

Standard precautions involve evidence-based activities aimed at interrupting the chain of infection. These include hand hygiene measures and use of a range of protective devices.

Standard precautions: hand hygiene

Handwashing with soap and water has been used to improve personal hygiene for centuries; however, the link between handwashing and the spread of disease was only established in the mid-nineteenth century. An Austrian medical officer, Ignaz Semmelweis, is considered to be the first person who recognised that hospital-acquired infection was directly transmitted via the hands of healthcare workers. Since then many further investigations have confirmed the important role that contaminated hands play in the transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens. Hand hygiene remains the cornerstone of infection prevention and control. Yet even though we know that proper use of hand hygiene is critical to the prevention of infection, compliance among healthcare workers is often below 40%.

Therefore, poor hand hygiene practice among healthcare workers is strongly linked with healthcare-associated infection transmission and is a major factor in the spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens within healthcare facilities. Despite this, efforts to improve the rate of hand hygiene compliance have historically been ineffective or poorly sustained. Numerous barriers to appropriate hand hygiene compliance have been reported (Whitby et al 2006) including:

• Hand hygiene products cause skin irritation and dryness

• Client needs perceived to take priority over hand hygiene

• Handwashing sinks/basins inconveniently located and/or not available

• The perception that glove use dispenses with the need for hand hygiene

• Insufficient time for hand hygiene, due to high workload and understaffing

• Poor knowledge of guidelines or protocols for hand hygiene

• Lack of positive role models

• Lack of recognition or understanding of the risk of cross-transmission of microbial pathogens

• Until recently, the lack of scientific information showing the definitive impact of improved hand hygiene on lowering healthcare-associated infection rates.

The introduction of the alcohol-based hand rub as well as an increase in hand hygiene compliance has shown a reduction in healthcare-associated infection in recent hospital-based studies. Since 2002, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) guidelines defined alcohol-based hand rub, where available, as the standard of care for hand hygiene practices in healthcare settings, whereas handwashing is reserved for particular situations only. WHO (2009) developed a culture change program which would improve hand hygiene compliance by all healthcare workers. It is known as ‘The 5 Moments of Hand Hygiene’.

National Hand Hygiene Initiative

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) has instigated the National Hand Hygiene Initiative (NHHI) and assigned the responsibility of its delivery and rollout to Hand Hygiene Australia (HHA 2010). The key aim of the national initiative is to improve hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers, and to reduce the transmission of infection in healthcare services throughout Australia. This involves a multi-faceted culture-change program to improve hand hygiene compliance through the increased use of alcohol-based hand rubs.

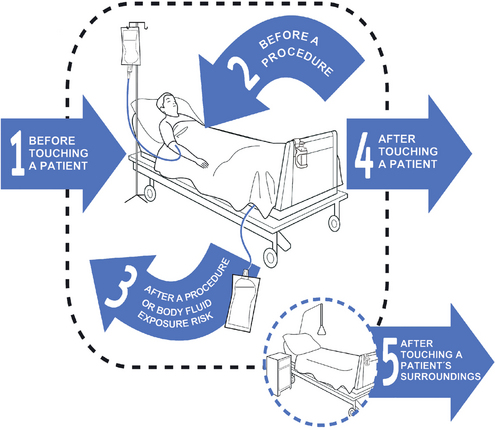

‘The 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene’ developed by WHO (2009) and adopted by Hand Hygiene Australia (Grayson et al 2009):

• protects clients against acquiring infections from the hands of the healthcare workers

• helps to protect clients from infectious agents (including their own) entering their bodies during procedures

• protects healthcare workers and the healthcare environment from acquiring clients’ infectious agents (Fig 20.2).

Figure 20.2 The ‘5 Moments for Hand Hygiene’ tool is based on evidence. It identifies when hand hygiene should be performed. That is, hand hygiene should be practised before every episode of client contact, including between different clients and between different care activities for the same client, and after any client activity or contact. The message for every healthcare worker is, perform hand hygiene before and after each patient contact or contact with the client environment

(© World Health Organization 2009. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Hand Hygiene Australia)

The 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene

Moment 1: Hand hygiene must be performed before touching a client

Moment 2: Hand hygiene must be performed immediately before a procedure

Moment 3: Hand hygiene must be performed following a procedure or potential body fluid exposure

Moment 4: Hand hygiene must be performed after touching a client

Moment 5: Hand hygiene must be performed after touching the client’s environment, without touching the client.

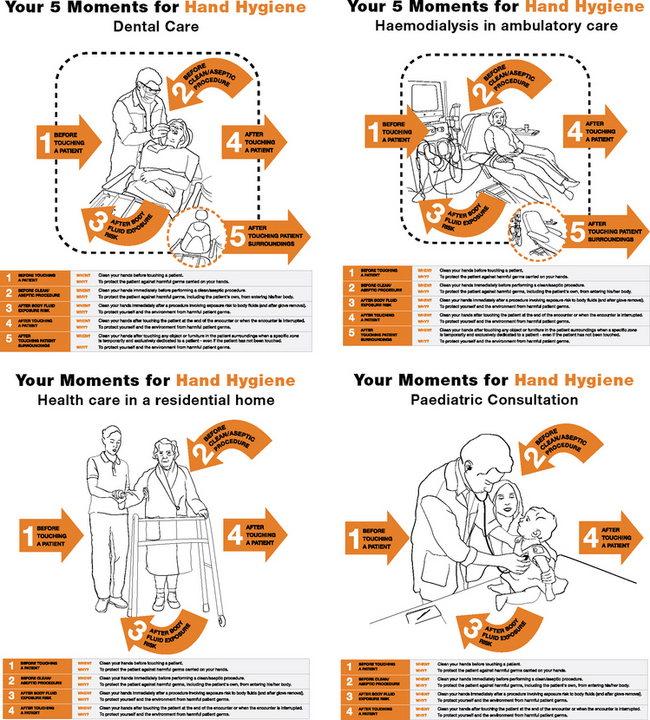

For ‘The 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene’ initiative to be effective, alcohol-based hand rub needs to be situated at point of use, for example, the end of the bed. Sustained, successful implementation of the initiative within the healthcare facility requires commitment and understanding from management, committed role models and champions throughout the facility, a team approach which should include not only the nursing sector but the medical practitioners as well and, most importantly, it requires understanding of the reason for the initiative and ownership of prevention of transmission of healthcare-associated infections by each stakeholder (Fig 20.3).

Figure 20.3 The 5 moments for hand hygiene can be applied in any healthcare setting, including the acute, day only, dental surgery, dialysis unit, nursery and clinic setting. The key emphasis is to perform hand hygiene before and after every episode of client contact, before and after any procedure and also after contact with the client’s environment. Hand hygiene must also be performed after the removal of gloves

(© World Health Organization 2009. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Hand Hygiene Australia)

Technique: is it important?

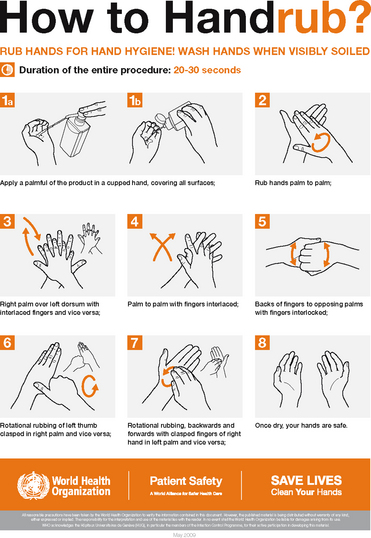

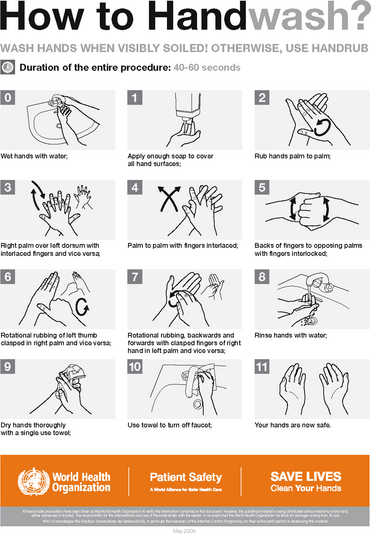

There are two recognised techniques for performing hand hygiene: hand hygiene with an alcohol-based hand rub and handwashing with soap and water (Figs 20.4 and 20.5).

Figure 20.4 How to use alcohol-based hand rub 1 Apply the amount recommended by the manufacturer onto dry hands 2 Rub hands together so that the solution comes in contact with all surfaces of the hand, paying attention to the tips of the fingers, the thumbs and the webbing between the fingers 3 Continue rubbing until the solution has evaporated and the hands are dry. Clinical note: This is of great importance when then donning gloves, because if hands are not dry, manipulation of gloves is very difficult and it may cause reactive dermatitis

(© World Health Organization 2009. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Hand Hygiene Australia)

Figure 20.5 How to handwash using soap (including antimicrobial soap) and water 1 Wet hands under running water and apply the recommended amount of liquid soap 2 Rub hands together for a minimum of 15 seconds so that the solution comes in contact with all surfaces of the hand, paying attention to the tips of the fingers, the thumbs and the webbing between the fingers (these areas are often missed during hand hygiene) 3 Rinse hands thoroughly under running water, and then pat dry with single-use towels. Moist skin becomes chapped readily

(© World Health Organization 2009. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Hand Hygiene Australia)

Clinical note: Effective hand hygiene relies on appropriate technique as much as on the selection of the correct product. If the technique is not appropriate this leads to failure of hand hygiene removing or killing microorganisms on the hands, despite the appearance of having complied with hand hygiene requirements.

Which product should be used?

Existing guidelines agree that hand hygiene using alcohol-based hand rubs is more effective against the majority of common infectious agents on hands than hand hygiene using plain or antiseptic soap and water. Such rubs can also be placed at point of use, are faster to use and the evidence shows they have better skin tolerability. The alcohol-based hand rub product must have Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approval for skin antisepsis and meet the requirements of EN 1500 testing standard for bactericidal effect.

Does improved hand hygiene make any difference?

Recent evidence of improved hand hygiene has been associated with:

• Sustained decreases in the incidence of infection caused by MRSA and VRE (Pittet & Boyce 2001)

• Reduction in healthcare-associated infections of up to 45% in a range of healthcare settings (Fendler et al 2002)

• Greater than 50% reduction in the rates of nosocomial disease associated with MRSA and other multi-resistant organisms, after 1–2 years (Grayson et al 2009).

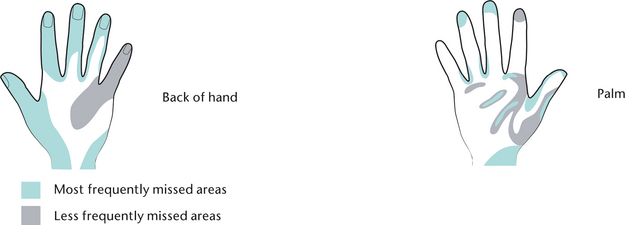

Hand hygiene practice alone is not sufficient to prevent and control infection and needs to be part of a multifaceted model to infection control. Figure 20.6 identifies the areas of the hands most often neglected during washing.

Other aspects of hand hygiene

As intact skin is the first line of defence against infection, cuts and abrasions are a possible source of entry for infectious agents and reduce the effectiveness of hand hygiene practices. To reduce the risk of cross-transmission of infectious agents, cuts and abrasions should be covered with waterproof dressings.

An emollient hand cream provided for use at the healthcare facility should be used regularly, such as after performing hand hygiene before a break or going off duty. This assists in maintaining skin integrity. The effectiveness of hand hygiene can be impacted by the type and length of fingernails (Boyce & Pittet 2002; Lin et al 2003). Artificial nails have been associated with higher levels of microorganisms, especially gram-negative bacilli and yeasts than natural nails (Boszczowski et al 2005; Gupta et al 2004; Moolenaar et al 2000). It is recommended, therefore, that fingernails should be kept short, that is, the length of the finger pad, and dirt free, and artificial nails should not be worn. Studies have shown that chipped nail polish may support the growth of organisms on the fingernails (Grayson et al 2009) it is therefore good practice not to wear nail polish.

Although there is less evidence involving the impact of jewellery on the effectiveness of hand hygiene, rings can interfere with the technique used to perform hand hygiene, resulting in higher total bacterial counts (Boyce & Pittet 2002). Hand contamination with infectious agents is increased with ring wearing (Trick et al 2003). The consensus is to discourage the wearing of watches, rings or other jewellery during client care.

The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Health Care (NHMRC 2010) suggest that each healthcare facility should develop policies about the wearing of jewellery (including body piercings), artificial nails or nail polish by employees. It is recommended that policies take into account the risks of transmission of infection to clients and healthcare workers, rather than cultural preferences.

Healthcare workers must also involve the clients and the visitors to the healthcare facility in hand hygiene. It is important that the clients’ hands as well as the nurses’ hands be cleansed before eating, after using the bedpan or toilet and after the hands have come into contact with any body substances, such as sputum or drainage from a wound. Strategically placed alcohol-based hand rub will assist with this.

Standard precautions: use of personal protective equipment

Any infectious agent transmitted by the contact or droplet route can potentially be transmitted by contamination of healthcare workers’ hands, skin or clothing. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is used to protect mucous membranes, airways, skin and clothing. PPE used as part of standard precautions includes gloves, gowns, aprons, surgical masks, protective eyewear or face shields and, in some circumstances, foot and hair coverings.

In determining the type of PPE to use, the nurse should consider the probability of exposure to blood and body substances, the type of client interaction and the likely route of transmission. All PPE must meet the relevant TGA criteria for listing on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ATGA) and should be used in accordance with manufacturer’s guidelines.

Aprons and gowns

International guidelines recommend that protective clothing (apron/gown) be worn by healthcare workers when:

• Close contact with the client, materials or equipment may lead to contamination of skin, uniforms or other clothing with infectious agents

• There is a risk of contamination with blood, body substances, secretions or excretion (except sweat) (Pratt et al 2007).

Clean, single-use, impervious, non-sterile, sterile, disposable, long or short sleeved? The type of gown or apron needed depends on the degree of risk and must be changed between clients.

Clinical note: Aprons and gowns must be removed before leaving the client-care area to prevent contamination of the environment outside the client’s room. Uniforms should be washed daily, even if aprons and gowns have been used.

Face and eye protection

As discussed earlier, the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose and eyes are portals of entry for infectious agents. Face and eye protection reduces the risk of exposure of healthcare workers to splashes or sprays of blood and body substances and is an important part of standard precautions.

Surgical masks are loose fitting, single-use items that cover the mouth and nose. They protect the person wearing them from splashes or sprays reaching the nose and mouth. Goggles provide reliable eye protection from splashes, sprays and respiratory droplets from multiple angles. Face shields provide protection to other parts of the face as well as the eyes.

Clinical note: Personal prescription glasses and contact lenses are not considered adequate eye protection. Newer styles of goggles are now available, that fit adequately over prescription glasses with minimal gaps.

Gloves

Gloves can protect both clients and healthcare workers from exposure to infectious agents that may be carried on hands. Hand hygiene should be performed before putting on gloves and after removal of gloves. Gloves are single-use items and should not be washed, but discarded. Gloves must be changed between clients and after every episode in individual client care. They should be put on immediately before a procedure and removed as soon as the procedure is completed. When removing gloves, care should be taken not to contaminate the hands. Gloves should be worn for each invasive procedure, for contact with sterile sites and non-intact skin or mucous membrane and for any activity that has been assessed as carrying a risk of exposure to blood, body substances, secretions and excretions. Glove use does not replace hand hygiene. Hand hygiene must always be performed after removal of gloves because gloves may have tiny defects and because hand contamination may take place during removal. Hands should be dry before donning gloves as skin reactions have been known to occur if hands are not dry under gloves.

Clinical note: Consideration of the task at hand and whether glove use is required is important, as latex sensitisation of healthcare workers is a risk. General research studies show a prevalence of 8–30% latex allergy among healthcare personnel worldwide (Manori 2010). Use of unpowdered latex gloves or latex free gloves may reduce the risk of increasing latex sensitisation. Figure 20.7 illustrates the correct method of removing contaminated gloves.

Figure 20.7 Removing contaminated gloves A: Removing the right glove. Take hold of the cuff on the glove on the right hand and slide it from the hand, folding the inside of the glove over the outside. This encloses the contaminated outside area. Avoid touching the skin of the right wrist or hand with the fingers of the contaminated glove on the left hand, as to do so would enable microorganisms to be transferred. B: Removing the left glove. Grasp the glove that has been removed from the right hand in the palm of the left gloved hand. Slip two fingers from the ungloved right hand under the band of the second glove at the wrist. Roll the glove off, turning it inside out, over the first glove. This action ensures that exposure of the contaminated surfaces on both gloves is minimal, reducing the risk of transferring microorganisms. C: Safe method of holding contaminated gloves. Ensuring that you hold and touch only the inside surface of the left-hand glove, drop the rolled up gloves into the appropriate receptacle for rubbish. The gloves should be disposed of in this way immediately after removal. This reduces the risk of spreading infection. Wash your hands promptly because there is no guarantee that gloves provide 100% protection. This also reduces the risk of developing an allergy to the latex in the gloves. Nurses who are left-handed may prefer to reverse this process.

(Courtesy of Teresa Lewis)

Hair covers

An elasticised paper cap is the most common hair covering. It is used whenever there is a risk of the hair becoming contaminated or if microorganisms from the hair might endanger the client. Nurses wear caps in the operating room environment and kitchen staff wear hair nets to prevent contamination of food.

Shoe covers

Disposable paper covers are worn over shoes whenever there is a risk of body substances splashing onto shoes during procedures. The covers are removed before leaving the room, to prevent pathogens being carried away from the area. Over-shoe cloth or paper covers are used in the operating room environment to contain any microorganisms that might be on the shoes of operating room staff.

To reduce the risk of transmission of infectious agents or contamination of self, PPE must be used appropriately. The sequence for putting on and taking off PPE is:

• Doffing PPE (Fig 20.8)

Figure 20.8 Sequence for removing PPE following airborne precautions. 1 Remove gloves (A & B) 2 Perform hand hygiene (C) 3 Remove eye protection (D) 4 Perform hand hygiene (E) 5 Remove long-sleeved gown, being careful not to contaminate uniform (F, G, H, I) 6 Dispose of gown (J) 7 Perform hand hygiene (K) 8 Step outside room and close door. Gently and carefully remove N95 mask (duck-bill mask) 9 Dispose of mask appropriately as in (J) 10 Perform hand hygiene (M)

(Courtesy of Teresa Lewis)

Standard precautions: safe handling and disposal of sharps

Sharp instruments represent the major cause of accidents involving potential exposure to blood-borne disease. Sharps must not be passed by hand between workers and handling should be kept to a minimum. Needles or any other sharp implement should not be recapped, bent or disconnected from syringes but instead disposed of intact. All sharp instruments and needles must be disposed of immediately after use by placing them into a special puncture-proof sharps container which conforms to Australian Standards AS 4031 or AS/NZ 4261. The container should be available as close as practicable to the place the sharp is used. The person using the sharp should be the person to dispose of it into the container. If a sharp is dropped onto the floor or bed it should be picked up and placed into the container using forceps. Sharp containers must not be filled above the mark that indicates the bin is three-quarters full.

Healthcare workers face the risk of injury and potential exposure to blood-borne infectious agents, including hepatitis B and C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from needles and other sharp instruments during many routine procedures. Hollow-bore needles are of particular concern, especially those used for blood collection or intravascular catheter insertion. This is because they are likely to contain residual blood and are associated with increased risk for blood-borne virus transmission. Training and education in the risks associated with procedures and the use of equipment used in the facility, safe working practices and correct handling and disposal procedures, including not overfilling containers, should be mandatory.

Sharps injury

If a sharps injury is sustained, how do you reduce the risk?

• Seek care or first aid if an injury is sustained

• If the skin has been penetrated, wash the affected area immediately with soap and water

• Alcohol-based hand rub can be utilised if soap and water is not available

• Do not squeeze the affected area

• Report the incident to your supervisor immediately

• Complete an incident or accident report, include date and time of exposure, how the incident happened and the name of the source (if known)

• Obtain informed consent from source if possible (if known) for serology to check for hepatitis B and C virus and human immunodeficiency virus

• Seek counselling. Ask about follow-up care, including postexposure prophylaxis (which is most effective if given soon after the exposure). Knowing your immune status to at least hepatitis B will help alleviate some anxiety.

If a sharps injury happens to you, you can be reassured that only a small proportion of accidental exposures result in infection. Taking immediate action will lower the risks even further.

Clinical note: Client insulin pens brought into the healthcare facility pose a great risk to staff. Where possible, the client should self-administer their own insulin and remove and discard the used needle. If this is not possible, the facility should have policies in place which state the staff should administer the insulin from an insulin vial using a single-use insulin syringe instead of the insulin pen. (There are tools on the market which are designed to assist the client to remove the needle from the pen; however, they are not designed as a risk-reducing tool for staff use.) There have also been many reported incidents of injury to staff when retrieving the insulin pen from the bedside drawer, due to the insulin pen being placed back in the drawer with used exposed needle still in situ.

Standard precautions: implementing environmental controls

Infectious agents can be widely found in healthcare settings and there is clinical evidence suggesting a connection between poor environmental hygiene and the transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings (Dancer 1999; NHMRC 2010).

General surfaces can be divided into two groups: those with minimal hand contact (e.g. floors and ceilings) and those with frequent skin contact (e.g. frequently touched surfaces such as doorknobs, light switches and bedrails etc). The recommendation for cleaning should be based on the risk of transmission of infection within a particular healthcare facility. All organisations should have a documented cleaning schedule that outlines clear responsibilities of staff, a roster of duties, the frequency of cleaning and the products required to clean specific areas (NHMRC 2010).

A detergent solution designed for general purpose cleaning is adequate for cleaning general surfaces as well as surfaces in close proximity to the client, unless there is uncertainty about the nature of the soiling on the surface, or there is presence of a multi-resistant organism or other infectious agent requiring transmission-based precautions. Many facilities have introduced detergent-impregnated wipes which may be used to clean equipment in between client use and small surface areas.

Floors are generally damp mopped in preference to dry mopping. Carpets in public areas and in general client-care areas should be vacuumed daily with well-maintained equipment fitted with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters to prevent dust being released into the air. In the case of a spill, clean up the excess as much as possible then the carpet should be cleaned using the hot water extraction method which is recognised by AS/NZ 3733:1995, to minimise chemical and soil residue.

Spillages of blood or any other body fluid in general areas should be contained and confined. Remove visible organic matter with absorbent material such as disposable paper towels, remove any broken glass or sharp material with forceps and soak up excess fluid using an absorbent clumping agent. The area should then be cleaned with a detergent solution, followed by a hypochlorite solution or a hospital-grade chemical disinfectant in accordance with the routine infection control policies and practices of the healthcare facility. A spill kit should be available in all clinical areas. It should contain a scoop and scraper, single-use gloves, protective apron, surgical mask and eye protection, absorbent agent, clinical waste bags and ties and detergent. All components should be disposable to prevent cross contamination. Cleaning is generally a non-nursing duty, but nurses have a responsibility to ensure that cleaning is carried out effectively and in line with infection control policies. Healthcare facilities use a variety of systems to ensure that cleaning standards are met. These include checklists, colour coding of cleaning equipment to reduce the risk of cross-infection, cleaning manuals, infection control guidance and monitoring strategies such as audits. Auditing is mostly done through visual checking; however, just because it looks clean does not necessarily mean it is free of infectious agents.

Clinical note: At the time of writing, more objective methods of assessing cleanliness and benchmarking (such as black spot auditing and detection of bacterial load using ATP tests) are being investigated.

Nurses also have a responsibility to ensure that linen is handled carefully; for example, bedclothes should not be carried up against the healthcare worker’s uniform, flicked or shaken, as these actions liberate dust and microorganisms which contaminate the uniform and the environment. Soiled linen should be rolled up or folded and placed immediately into the appropriate receptacle. All healthcare workers should wear clean washable clothing that is changed daily. If linen is heavily soiled with blood or other body substances, the linen should be placed into a leakproof bag before placing it into the appropriate receptacle.

Actions should be taken to keep all areas free from the possibility of vector transmission (flies, other insects and animals) by placing rubbish and soiled linen immediately into the appropriate containers, by disposing of food scraps correctly, by keeping any food or fluid covered and by emptying toilet utensils (bedpans and urinals) immediately.

Rubbish containers should be equipped with close-fitting lids and must be emptied frequently and never left with material overflowing from them.

Standard precautions: reprocessing of reusable instruments and equipment

Disposable single-use equipment must be disposed of immediately after use and should not be reprocessed. Non-disposable instruments and equipment must be reprocessed according to their intended use and manufacturers’ guidelines and instructions. Reprocessing protocols are implemented in order to reduce or eliminate microorganisms. Reprocessing of instruments and equipment includes general cleaning, disinfection (by heat and water, or chemical disinfectants) and/or sterilisation. The level of reprocessing that is necessary depends on the body site where specific items are used, and therefore the level of contamination risk involved. The Spaulding system was devised over 30 years ago; it has been retained and refined and is still widely used by infection control professionals and others when planning methods for disinfection or sterilisation (Rutala, Weber & HICPAC 2008). The levels of risk are:

• Critical: the instruments are used to enter or penetrate into sterile tissue or body cavities or into the blood stream. These items must be cleaned thoroughly as soon as possible after using and then sterilised

• Semi-critical: these items come into contact with mucous membranes or non-intact skin. These items must be cleaned thoroughly as soon as possible after using and then undergo steam sterilisation. If the item will not tolerate steam, high-level chemical or thermal disinfection is required

• Non-critical: these items come into contact with intact skin. Thorough cleaning with a detergent solution is required. In the case where the item has been used on a client requiring transmission-based precautions decontamination may be necessary using a low or intermediate level TGA-registered disinfectant after cleaning.

Routine cleaning of instruments

Cleaning is an essential factor in preventing cross-infection. Cleaning is the removal from items of all foreign material, such as soil and organic material. Detergent and water is generally sufficient for routine cleaning. All reusable instruments and equipment should be cleaned as soon as possible after use, regardless of risk level and any other infection control measures required. If items are not thoroughly cleaned they cannot later be effectively disinfected or sterilised. If an item cannot be cleaned it cannot be disinfected or sterilised (NHMRC 2010). A plastic apron, general purpose utility gloves and protective face and eyewear should be worn when cleaning equipment that may be contaminated with material such as blood, mucus, pus, sputum or faeces. For checking effectiveness of cleaning, Australian Standard (AS 2945:2002) outlines specific test methods to verify manual and automated processes.

Disinfection

The first links in the chain of infection, the infectious agent and the reservoir, are interrupted by the use of antiseptics and disinfectants. Disinfection is not a sterilising process. It is a process intended to destroy pathogenic microorganisms (with the exception of spores) or render them inert, using either thermal (using heat and water, at temperatures that destroy infectious agents) or chemical means. Examples of disinfectants are alcohols, chlorine and chlorine compounds, formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, phenolics and quaternary ammonium compounds; they are used on inanimate objects. Disinfectants can be caustic and toxic to tissues. An antiseptic is a chemical preparation used on skin or tissue. Both disinfectants and antiseptics are said to have bactericidal or bacteriostatic properties. A bactericidal preparation destroys bacteria, whereas a bacteriostatic preparation prevents the growth and reproduction of bacteria. Different grades of disinfectants are used for different purposes. Spore-forming bacteria such as Clostridium difficile may be inhibited by only a few of the agents normally effective against other forms of bacteria. Each healthcare institution should have its own policy in relation to disinfection techniques.

Sterilisation

Sterilisation is a process that is intended to destroy all types of microorganisms, including bacterial spores and viruses. Four commonly used methods of sterilisation are moist heat, gas, boiling water and radiation. A sterile article is one that is totally free from all microorganisms. Sterility is an all-or-none state, because a single living cell renders an article unsterile.

Records of sterilisation must be kept to verify that an appropriate reprocessing system is in place according to state and federal legislation. Details of documentation required can be found in Australia Standards AS/NZ 4187 and AS/NZ 4815.

Storage and maintenance of sterile items

All sterile or high-level disinfected items must be stored in a way that maintains their level of reprocessing. Dry, sterile, packaged instruments and equipment should be stored in a clean, dry environment and protected from sharp objects that may damage the packaging. It is the nurse’s responsibility to check that the packaging of the sterile item about to be used has not been compromised.

Standard precautions: aseptic non-touch technique

Asepsis and infection prevention and control

Terminology historically has generated an inaccurate and confusing paradigm based on the terms sterile, aseptic and clean techniques.

Sterile: ‘Free from micro-organisms’ (Weller 1997).

Due to the large number of organisms in the atmosphere it is not possible to achieve a sterile technique in a typical healthcare setting. Near-sterile techniques can only be achieved in controlled environments such as laminar air flow cabinets or theatres. The commonly used term ‘sterile technique’, the instruction to maintain sterility of equipment exposed to air, is not possible and is often applied incorrectly.

Asepsis: ‘Freedom from infection or infectious (pathogenic) material’ (Weller 1997). It is defined as the absence of infectious agents that may produce disease.

Aseptic technique refers to practices used by healthcare workers to reduce the number of infectious agents; prevent or reduce the likelihood of transmission of infectious agents from one person or place to another; and render and maintain objects and areas as free as possible from infectious agents. It protects clients during invasive clinical procedures.

Clean: ‘Free from dirt, marks or stains’ (McLeod 1991).

Techniques used to maintain asepsis can be categorised into clean (medical asepsis) and sterile techniques (surgical asepsis).

Aseptic techniques are measures to lower the risk of infection by minimising the number of infection-producing microorganisms. The practices are classified as follows:

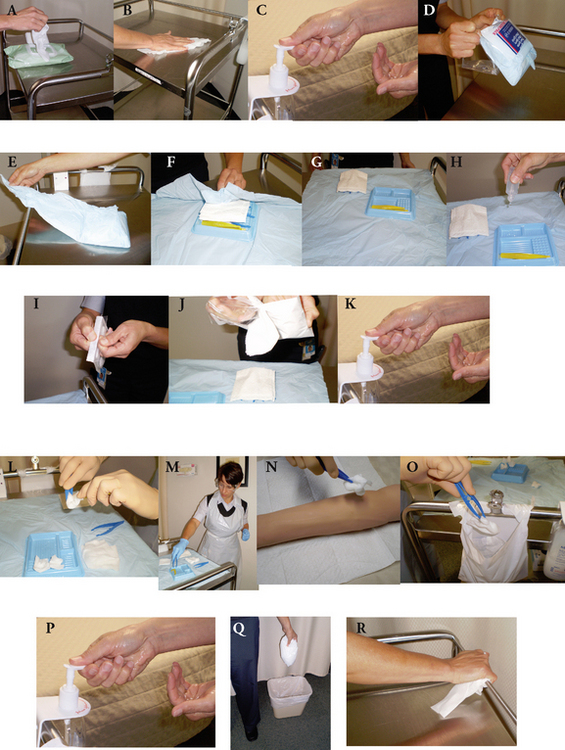

A clean/standard aseptic non-touch technique refers to routine work practices that reduce the numbers of infectious agents. Routine practices include hand hygiene, the use of barriers and environmental controls (no bed making or clients using commodes in the near vicinity) to reduce transmission of infectious agents, and the reprocessing of equipment between client use. Procedures requiring standard aseptic non-touch technique will characteristically be technically simple and short in duration (usually less than 20 minutes). They require a general aseptic field and non-sterile gloves. Examples are a simple wound dressing, insertion of a peripheral line and removing an endotracheal tube, sutures or drains (Fig 20.9).

Figure 20.9 Standard aseptic technique. To be used for a simple dressing. Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions. 1 Using neutral detergent: wipe down the dressing trolley/flat surface used to set up the aseptic dressing field (A & B) 2 Perform hand hygiene (C) 3 Open up commercially packaged sterile dressing pack (D) 4 Open the outer flap of the sterile package away from you (E) 5 Open the side flaps, one at a time, followed by the flap closest to you. Using this last flap gently manipulate the sterile tray and empty contents onto the field (F, G) 6 Open a commercially prepared sterile package (e.g. gauze). Hold the outer wrapping tightly, empty contents onto the sterile field. Take care not to contaminate the contents or aseptic field. (I, J) 7 Add sterile solutions to the aseptic field. Lean across the field over the shortest distance. Hold the container at a height to prevent splashing. Pour/squeeze from a single patient use container; discard any unused solution to prevent cross infection 8 Perform procedural hand hygiene (K) 9 Don PPE as per standard precautions 10 Using sterile tongs premoisten and squeeze out excess fluid from gauze (L, M) 11 Using tongs clean wound. Clean from inside out if possible, to prevent cross infection (N) 12 Have a waste receptacle at point of use (O) 13 Upon completion of dressing remove PPE and perform hand hygiene (P) 14 Dispose of PPE in waste receptacle (Q) 15 Wipe down the dressing trolley or surface that the sterile field has been set up on (R) 16 Perform hand hygiene (K)

(Courtesy of Teresa Lewis)

A sterile/surgical aseptic non-touch technique involves practices designed to eliminate the introduction of microorganisms into surgical incisions, tissues or wounds (e.g. use of sterile instruments, dressing materials and gloves, skin antisepsis and creation of a sterile field within which to operate). Procedures requiring surgical aseptic non-touch technique are technically complex, and involve extended periods of time. They are most often practised in the operating room, obstetric areas and major diagnostic or special treatment areas such as a burns unit or an intensive care unit. In the operating room, nurses follow a process to ensure that asepsis is maintained. A surgical aseptic technique may also be used by the nurse in a general medical or surgical unit or in a client’s home; for example, when performing a urinary catheterisation or redressing wounds. On these occasions it is not always necessary for the nurse to follow the above process in full, depending on the level of expertise and experience; for example, often only sterile gloves, a mask and a sterile field are needed, provided that the principles of surgical asepsis are maintained. To reduce the risk of microorganisms being transmitted via the respiratory route, talking by the nurse conducting any sterile procedure is kept to the absolute minimum.

Principles of surgical asepsis

Principles of surgical asepsis are applied when nurses create a sterile field, add supplies or liquids to a sterile field or don sterile gloves. The principles of surgical asepsis are that:

• Sterility is preserved by touching a sterile item only with another one that is sterile (e.g. picking up a sterile dressing with sterile forceps)

• Only sterile objects may be placed on a sterile field

• Once a sterile item touches something that is not sterile it is contaminated (e.g. if the nurse touches a sterile dressing with an ungloved hand)

• A sterile object held out of the range of vision or below a person’s waist is considered contaminated

• Prolonged exposure to air leads to contamination of a sterile field or object

• The edges of a sterile field are considered to be contaminated

• If a sterile field becomes wet it is considered contaminated

• Whenever there is the slightest doubt about an article being sterile it is considered unsterile and discarded.

Creating a sterile field for a standard or surgical aseptic non-touch technique

The nurse creates a sterile field by using the inner surface of the cloth or wrapper that contains the sterile items as a work surface. This area is where the nurse places sterile equipment. The nurse must not contaminate the inner area. Before undertaking a procedure that needs a sterile field the nurse should:

• Remove objects from the area to be used

• Assemble all equipment needed

• Check the date or sterilisation indicator tape on all sterile packages to be used.

Sterile items that have been packaged commercially are generally designed so that the outer paper or plastic wrapper can be torn away simply without contaminating the inner contents. The outer wrapper should be removed by tearing away from the body. Items sterilised within the facility may have an outer wrapper of thick strong paper or cloth. To open these items the nurse follows this procedure:

• Place the package in the centre of a flat surface at or above waist level

• Remove tape that seals the item

• Position the package so that the outermost (distal) triangular flap can be moved away from the front of the body

• Touch no more than 2.5 cm of the edge of the wrapper

• Smoothly open the first triangular side flaps, keeping the arms flat and away from the inner sterile area. Ensure the opened flap lays flat on the working surface

• Standing away from the package, take hold of the outside surface of the last flap, pull the flap back towards the body, allowing it to fall flat on the working surface.

Adding sterile items to a sterile field