CHAPTER 29 Urinary elimination

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the transport mechanisms in the body related to the urinary system

• Explain homeostasis as related to the urinary system

• Name the parts of the urinary system and describe the structure and function of each part

• Identify the factors that affect urinary elimination, and associated problems throughout the life span

• Describe the different types of urinary incontinence and possible causes

• Describe the major manifestations of urinary system disorders

• State the diagnostic tests used to assess urinary system function

• Consider the psychosocial aspects of care from a person-centred and relationship care perspective

• Assist in planning and implementing nursing care for the client with a urinary system disorder

The urinary system is responsible for maintaining homeostasis and eliminating waste products of body metabolism through the excretion of urine. Many factors can affect the formation of urine and the subsequent excretion urine and this chapter provides an overview of the main issues. Nursing management of clients with urinary elimination disorders requires an informed understanding of factors impacting on an individual’s lifestyle and a care plan to adequately respond to these needs, as well the sensitivity to sustain the client’s sense of dignity and self-esteem throughout.

I was relieved when the tests came back clear after I had my prostate surgery. Initially I wasn’t worried about the dribbling of urine. Three months later though, the dribbling was still evident. I worried about the smell, about wetting the bed if I stayed away from home. I hated buying pads at the supermarket. It was not until I spoke to the nurse at my GP clinic did I gain more confidence with dealing with the side effects of the surgery.

THE URINARY SYSTEM

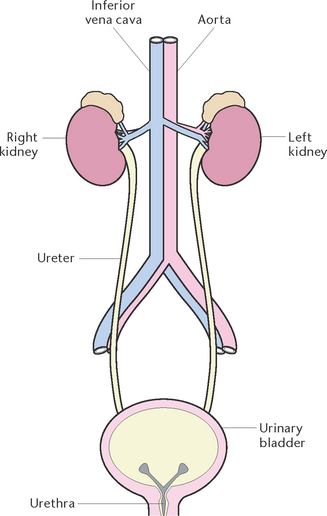

The urinary system (Fig 29.1) filters waste products from the blood and excretes them in the form of urine. The urinary system is also instrumental in regulating the rates of elimination of water and electrolytes from the body. By regulating the volume of the body fluid, the urinary system helps maintain blood pressure and the electrolyte content and pH of the blood. The urinary system consists of the kidneys, which filter blood; the ureters, which transport urine to the bladder; and the bladder, which stores the urine until it is excreted via the urethra.

The kidneys

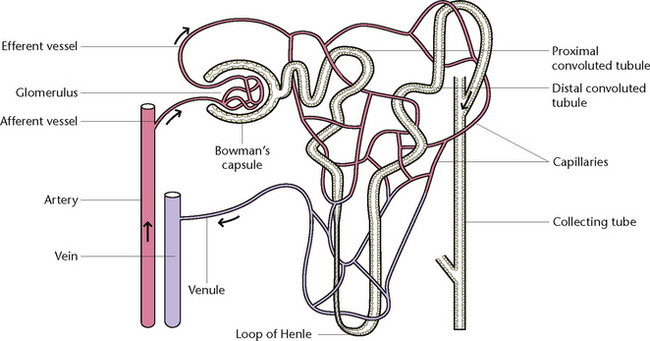

Each kidney contains at least 1 million nephrons, together with their collecting tubules or ducts. The nephron (Fig 29.2) is the functional unit of the kidney. Each nephron is composed of a vascular and tubular system that allows for the formation of urine. The nephrons are located in the renal tissue, with most in the cortex and some extending deep into the medulla of the kidney.

The adult kidney weighs 120–170 g, is 10–13 cm in length, 5–6 cm wide and 3–4 cm thick. The kidneys are protected and supported by renal fascia and by layers of perirenal fat. They are positioned at approximately vertebral level of T12 to L3, the right kidney usually slightly lower than the left.

The functions of the kidneys are to maintain homeostasis. Homeostasis is the process that controls the body’s internal environment. External variables may change such as heat, cold, fluid, diet and stress but to sustain the body in a state of equilibrium, receptors in the body identify if something is off balance and trigger a negative feedback. The urinary system maintains homeostasis by:

• Filtering the blood to maintain its normal composition, volume and pH

In carrying out these functions the kidneys excrete urine. Urine is made up of water and dissolved substances that are in excess of the body’s need to function, and includes byproducts of metabolism, such as urea. These substances are transported into the bloodstream, which enters the kidney via a branch of the renal artery. The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney. Each nephron is composed of a vascular and tubular system that allows for the formation of urine. The nephrons are located in the renal tissue, with most in the cortex and some extending deep into the medulla of the kidney. The blood is filtered from there through the glomerulus, where glucose, minerals, urea, other soluble substances and water pass through to the renal tubule.

Kidney function is controlled by both the nervous and the endocrine systems which in turn control:

• Adrenaline, secreted by the adrenal, or suprarenal, glands, which helps maintain the high level of blood pressure in the glomerulus

• Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), secreted by the pituitary gland, which controls the amount of water reabsorbed from the tubules

• Aldosterone, secreted by the suprarenal glands, which controls the tubules’ reabsorption of mineral salts.

The ureters

The ureters are two narrow, thick-walled muscular tubes, 25–30 cm long, which originate in the renal pelvis of each kidney. They pass down the posterior abdominal wall and into the pelvic cavity to enter the posterior base of the bladder. The ureters enter the bladder at an oblique angle so that, as the bladder fills and contracts, urine is not forced back towards the kidneys. The walls of the ureters consist of an outer fibrous coat that is continuous with the renal capsule, a middle coat of involuntary muscle and a lining of transitional epithelium. The function of the ureters is to carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder, by means of peristaltic action. The involuntary muscle layer in the walls of the ureters contract from 1–5 times per minute to force urine into the bladder.

The urinary bladder

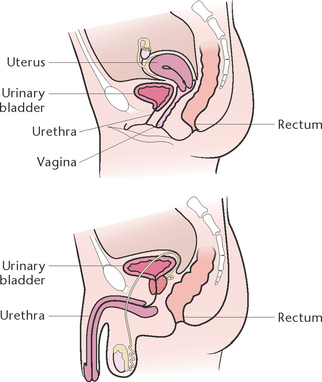

The urinary bladder is a hollow muscular organ that acts as a reservoir for urine and is supported by the detrusor muscle. The detrusor muscle is a layer of the urinary bladder wall made of smooth muscle fibres arranged in spiral, longitudinal and circular bundles; its competency is vital to maintaining continence. In the female it is in front of the uterus and in the male it sits in front of the rectum. The walls of the bladder consist of:

• A covering of peritoneum over the upper portion (the fundus)

• A layer of involuntary muscle

• A layer of connective tissue

• A layer comprised of mucous membranes which are formed into folds (rugae) which increase the surface areas of the bladder walls, enabling the bladder to expand when full and contract when empty.

The trigone of the bladder is a triangle formed by the two ureteric orifices, where the ureters enter the bladder, and the urethral orifice at the neck of the bladder. A band of the detrusor muscle encircles this opening to form the internal urethral sphincter; incompetence of this sphincter may have an impact on continence.

Micturition (or voiding) is the act of passing urine. While the normal capacity of the adult urinary bladder is about 450 mL, the bladder is capable of expanding to hold larger amounts. The bladder fills slowly over a period of time and, when it holds about 300–500 mL, a desire to empty the bladder is experienced. A reflex initiated by impulses from stretch receptors in the bladder wall regulates the process of micturition. The sensory neurons transmit the impulses to the spinal cord, where they are relayed to the brain, which in turn stimulates parasympathetic neurons that innervate the bladder wall. When a client is ready to pass urine, these impulses cause the bladder muscles to contract, the internal urethral sphincter relaxes and the desire to urinate is activated. The person is then able to voluntarily relax the external sphincter and void at an appropriate time and place. Urine is usually excreted in amounts of 1–2 L in 24 hours.

The urethra

The urethra (Fig 29.3) is a muscular tube extending from the neck of the bladder to the external meatus. In the female the urethra is about 2.5–4 cm long and opens at the external urethral orifice in front of the vaginal opening. The external sphincter guards this opening. In the male, the urethra is about 15–20 cm long and opens at the tip of the penis. The male urethra has a double function: it forms a passage for urine as well as semen. It is guarded by an external sphincter immediately below the prostatic portion of the urethra. The function of the urethra is to provide a passage for urine from the bladder, out of the body.

ALTERATIONS IN URINARY SYSTEM FUNCTIONING

The kidneys are essential in the maintenance of homeostasis, as they regulate the rates of elimination of water and electrolytes from the body and contribute to the maintenance of a constant blood pH and blood pressure. The kidneys also eliminate metabolic waste products and toxic substances. Therefore, any dysfunction in the formation or excretion of urine can have major adverse effects on homeostasis.

Changes in kidney structure

Atrophy of the kidneys because of destruction of the renal tissue can occur in many chronic renal diseases. Alternatively, the kidneys can become enlarged because of blockage of the ureters, enlargement of the prostate gland or from invasion of the kidneys by neoplastic cells. If there is an obstruction lower down in the urinary tract, the ureters may become enlarged in diameter as they fill with urine that cannot pass the obstruction.

Fluid and electrolyte imbalance

If the kidneys are unable to concentrate the urine by regulating reabsorption, the loss of a large amount of dilute urine may result in fluid imbalance. If they fail to excrete sufficient water, an increase in the total circulating fluid volume impedes cardiovascular function. Renal disease may result in abnormal retention or loss of sodium, potassium, calcium or phosphorus.

Elimination of wastes

Normal metabolism produces an excess of acids. To compensate, the kidneys excrete acids and return bicarbonate to the plasma and extracellular fluid. An acid–base imbalance (metabolic acidosis) will result if this function is impaired; that is, if there is an increased amount of acid or a decreased amount of base in the body. The kidneys must also continually filter and excrete nitrogenous wastes derived from protein metabolism.

Urine output

Alterations in urine output may be temporary or long term. Urine output may be decreased, as in obstruction of the ureter or acute or chronic renal failure, or it may be increased, as during the diuretic stage of acute renal failure. The passage of urine along the urinary tract may be impeded by an obstruction, such as a tumour or calculus.

MANIFESTATIONS OF URINARY SYSTEM DISORDERS

Disorders of the urinary system may produce signs and symptoms that vary according to the site and severity of the problem.

Pain

Pain is more common in acute, rather than chronic, disorders of the kidneys and urinary tract. Pain that originates from the kidneys is generally experienced as a dull ache in the lower back and may radiate to the lower abdominal area. Pain associated with renal colic is sudden and severe. It is felt in the lower back and may radiate to the groin area. Nausea and vomiting frequently accompany this type of pain.

Suprapubic pain may result from spasms or over-distension of the bladder, as in acute retention of urine. An infection of the lower urinary tract, such as cystitis, commonly causes pain and burning during and/or after voiding. Strangury is the term used to describe slow and painful spasmodic discharge of urine frequently associated with a ‘burning’ sensation.

Changes in voiding pattern

There may be an increase in the frequency of voiding, problems controlling the passage of urine, difficulty in initiating micturition or a sense of urgency associated with the need to void.

Changes in output

Changes in the output of urine include voiding increased or decreased amounts and cessation of the production or secretion of urine.

Changes in the urine

Abnormalities of the urine associated with urinary system disorders include changes in the normal colour, clarity or odour of urine. The urine may be blood stained or dark amber, cloudy or smoky in appearance. Chronic renal disease can result in pale, almost colourless urine. A foul smelling ‘fishy’ odour is commonly present when there is a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Other manifestations

A client with a lower UTI commonly experiences pyrexia, malaise, nausea and vomiting and pelvic and abdominal discomfort, whereas those with renal disease may experience hypertension, oedema, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, skin changes and neurological symptoms such as headache or altered consciousness (Berman et al 2012; Marieb & Hoehn 2010; McCance & Huether 2010).

CHANGES TO VOIDING PATTERNS

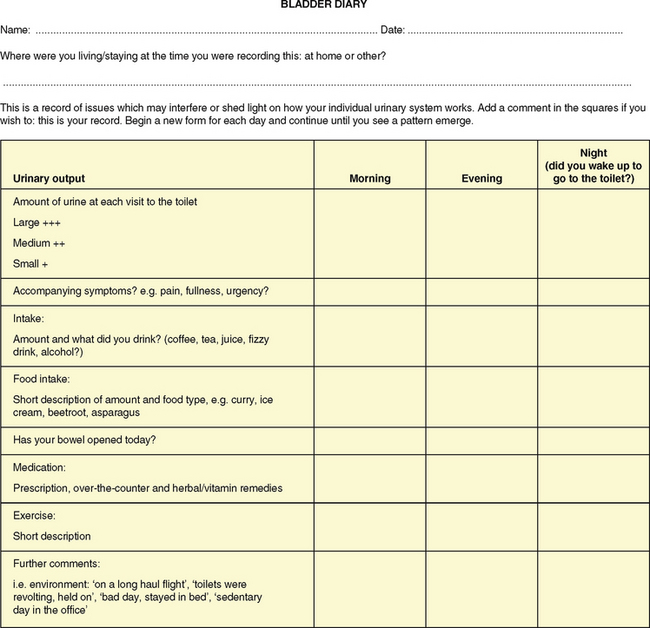

Any change to voiding patterns needs to be recorded to establish a history. There are various terms for changes, listed in Table 29.1, which are universally understood by health professionals but lay terms may need to be used when discussing the symptoms with the individual or their significant other. The use of a fluid balance chart to record and analyse intake and output is vital for assessment, as is a bladder diary (see example in Fig 29.4), which provides a more in-depth assessment, including activities and dietary and fluid intake, and gives a more holistic view of an individual’s voiding pattern (Brown 2007).

Table 29.1 Alterations in urinary elimination patterns

| Term | Defnition |

|---|---|

| Anuria | The absence of urine production, or a urinary output <100 mL/day (<30 mL/hour) |

| Dribbling | Dribbling of urine from the urethra despite voluntary control of micturition. It may be at the end of micturition or continuous |

| Dysuria | Pain and burning on micturition, usually as a result of an infection or obstruction |

| Frequency | Voiding at frequent intervals, i.e. <2-hourly |

| Haematuria | The presence of blood in the urine |

| Hesitancy | Difficulty starting micturition |

| Incontinence | The inability to control the passage of urine |

| Nocturia | Excessive or frequent urination at night |

| Oliguria | A decreased urine production resulting in an output <500 mL/day |

| Polyuria | The excretion of an abnormally large volume of urine |

| Retention | The accumulation of urine in the bladder as a result of being unable to empty the bladder completely |

| Residual urine | The volume of urine remaining after voiding |

| Urgency | The feeling of needing to void immediately |

Nursing interventions

When a client is experiencing altered voiding patterns, the cause must be identified and treated. Difficulty in passing urine may result from an obstruction to the outflow of urine but may also be caused by other factors such as:

• Anxiety, stress, nervousness or embarrassment associated with the need to use toilet aids

• The need to remain in a supine position when using toilet aids

• The effects of medications, anaesthesia or the acute stress of surgery

• Pain or a burning sensation which can lead to tension in the muscles controlling the urethral opening

Nursing actions that may be implemented to induce micturition include:

• Using standard precautions for dealing with body fluids

• Relieving pain. If a client is experiencing pain, the cause should be identified and treated. Nursing actions to relieve pain include ensuring that the client is positioned comfortably, checking any splints or dressings to detect whether they are causing the pain and checking for prescribed analgesia

• Ensuring adequate privacy and sufficient time for the client to void. If possible, the client should be left alone to use the toilet aids (e.g. commode, bedpan or urinal) as they may be self-conscious about the need to eliminate in the presence of others. Ensure the client’s safety and that the call bell is accessible

• Ensuring awareness of cultural differences in position and environment for voiding by communicating sensitively with the client

• Being alert for difficulties which may impede normal urination in time or environment; for example, coexisting conditions impairing physical or cognitive functioning

• Assisting the client to assume a natural voiding position. Whenever possible the client should be permitted to use the toilet but, if this is contraindicated, an upright position may assist. Males may find it easier to pass urine if allowed to stand

• Helping the client to relax. Unless contraindicated, a warm shower or bath, or the pouring of warm water over the genitalia of a female, may stimulate micturition. Further stimulation techniques may include the sound of running water (e.g. turning on a nearby tap)

• Encouraging the client to drink adequate amounts of fluids, unless this is contraindicated. The recommended fluid intake for adults is 1400–2000 mL per day

• Using clear signage to indicate the location of toilet facilities.

If these actions fail to induce micturition and the client is uncomfortable because of a distended bladder, it may be necessary to implement further actions, such as inserting a urinary catheter.

Screening and investigations

Urine tests

Various sources of information can be collected through the use of daily charts such as fluid balance charts, bladder diaries which record voiding patterns and which may note, for example, an interrupted stream or difficulties in voiding as well as a history of the client’s elimination pattern. As the body’s normal metabolism produces wastes that must be eliminated regularly to maintain effective body function, the observation of urine and the client’s ability to eliminate it provides the nurse with an objective assessment data. The elimination of urine, or voiding, should be voluntary and painless. The frequency with which urine is passed varies with each individual. Factors that affect the frequency of voiding and the volume of urine include fluid input, bladder capacity, response to the need to void and the availability of toilet facilities. The frequency of voiding, and often the amount of urine voided, can be increased by a large fluid input, fear or anxiety, exposure to a cold environment and some disease states and decreased by a low fluid input, exposure to a hot environment and some disease states.

Preparation

Standard precautions apply for all collection of body fluids. If urine is to be collected for a screening urinalysis, the client is requested to void into a clean bedpan or urinal or a suitable clean receptacle (Fig 29.5.). The urine should not be contaminated by faeces or menstrual blood, as a false assessment may result. The urine is transferred from the toilet utensil into a clean container for observation and analysis immediately after collection. Correct and ongoing identification of sample is of paramount importance.

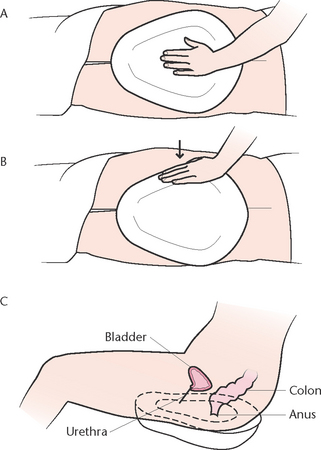

Figure 29.5 Positioning a bedpan A: Another method of placing a bedpan is used when the client is unable to help. The client lies on one side and the bedpan is placed firmly against the buttocks B: The nurse pushes down on the bedpan and towards the client C: The client is positioned on the bedpan so that the urethra and anus are directly over the opening

Observation

In health urine is clear, amber in colour and has a faint odour. Menstruation or any other vaginal discharge and certain medications, supplements or foods can alter the colour and odour of urine and certain diseases will vary the condition and clarity of the urine, so it is important to document what is observed and smelt. Further observations should note if the urine is cloudy or if there is sediment present (Table 29.2).

Table 29.2 Abnormalities of urine detected by observation

| Observation | Deviation from normal | Possible cause |

|---|---|---|

| Colour | Pale | |

| Dark or brown | Concentrated urine due to dehydration or presence of bile pigment, e.g. in liver or gallbladder disease, or indication of poor hydration | |

| Smoky | Presence of occult blood | |

| Red | Presence of frank blood | |

| Bright yellow, blue or green | Specifc medications | |

| Mucous plugs, viscous, thick | White blood cells, bacteria, pus or contaminants such as prostatic fluid or vaginal discharge may cause cloudy urine | |

| Odour | Ammonia | Decomposing urine |

| Foul-smelling ‘fshy’ odour | Infected urine | |

| Sweet smelling | Presence of glucose, e.g. in diabetes mellitus | |

| Foreign substances | Pus | Urinary tract infection |

| Stones, gravel | Calculi in urinary tract | |

| Amount | Higher than normal in 24 hours | High fluid intake, diuretic medications, diseases e.g. diabetes mellitus |

| Lower than normal in 24 hours |

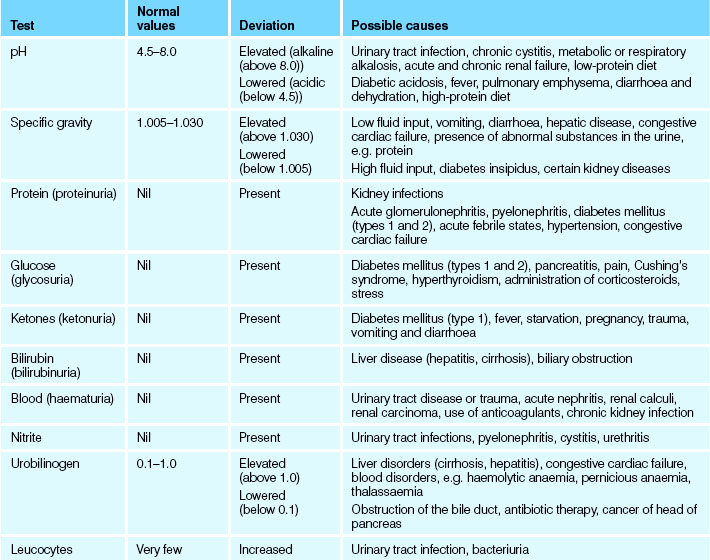

Urinalysis (routine)

Reagent strips are used to screen urine samples. Should the urine contain pigments, for example, from vitamin supplements (often bright yellow), they may affect the efficacy of the test. Check each container for ‘use-by date’, and ensure the strips are dry and that the container has an efficient closure. Each manufacturer may vary slightly in application of the test so check information as to how to read the strip and the time needed for a result before commencing the test. There are a large number of diseases which contribute to abnormal readings, many of which are not well known or will require a specialist response. Listed below are the common causes for abnormalities.

• The presence of leucocytes and nitrates may indicate the presence of bacteria

• The presence of protein indicates disease or trauma although, as a client ages, the kidneys become less efficient and protein may be detected

• The presence of acetone and glucose may indicate diabetes, although there are other reasons for their presence

• The presence of blood in urine—haematuria—may indicate contamination (e.g. menstrual blood), trauma or infection

• The presence of bilirubin suggests changes or infection to the liver and biliary system.

In health urine has a pH of between 4.5 and 8.0; that is, slightly acidic (average is 6.0). A value of 7.0 is neutral, below 7.0 is acid, and above 7.0 is alkaline. pH is frequently affected by what the client has ingested, for example, acid food or a vegetarian diet. The pH value will also be altered in the presence of bacteria or renal calculi and an incorrect result will be obtained if the urine has been left standing for some time.

In health a specific gravity of between 1.005 and 1.030 is usual. Specific gravity is a measure of the concentration of particles in the urine and reflects the ability of the kidneys to concentrate or dilute urine. It will be altered in over- or under-hydration.

Disposal of excreta is via the toilet or specified equipment in a ‘dirty utility’ space. Equipment is cleaned and sterilised according to facility policy. Standard precautions are maintained throughout the procedure.

Accurate data collection and recording is vital evidence for assessment and diagnosis.

Urinalysis (laboratory)

Abnormal findings from a routine urinalysis often require further investigation by a laboratory and this will be ordered by the client’s doctor or nurse practitioner.

Adequate information about the client and the specimen must be provided. The label on the specimen container must contain the client’s name, registration number, the date and time of collection and the method used to collect the specimen; for example, catheter specimen of urine. When a specimen is despatched for laboratory analysis it must be accompanied by the appropriate signed request form with type of collection and the specific laboratory tests to be performed.

Specimens must be sent to the laboratory as soon as possible after collection; if delay is anticipated the specimen must be refrigerated as soon as possible. Depending on ambient temperature, urine left for more than 2 hours without some form of preservation such as refrigeration is unlikely to produce an accurate result and should be discarded due to decomposition of the urine and increased microbial activity.

If the client is responsible for collecting the urine specimen, the nurse should provide the client with the information necessary to ensure that the collection is performed correctly.

All urine excreted during a timed collection, for example, during a 24-hour period, is collected and sent for laboratory analysis to measure the quantity of various substances present, such as specific hormones. Table 29.3 describes the results on urinalysis.

Mid-stream specimen

This method of collection is used to obtain a sample of urine that is not contaminated by microorganisms from outside the urinary tract and therefore must be collected in a sterile receptacle. The urine is sent to the laboratory to be tested for the presence of microorganisms and their sensitivity to antibiotics. The aim is to collect the middle portion of the stream of urine. A suggested method of collection is outlined in Procedural Guideline 29.1.

Procedural Guideline 29.1 Mid-stream urine collection

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Explain to client and/or family member reason specimen is needed, how client can assist (when applicable) and how to obtain a specimen that is free of tissue and stool | Promotes cooperation and client participation. Where appropriate client can collect clean-voided specimen independently |

| Give client or family member towel, clean dampened washcloth to cleanse perineum, or assist client (after application of clean gloves) with cleansing perineum Perform hand hygiene | Clients usually prefer to wash their own perineal area when possible. Prevents external microorganisms from contaminating the specimen |

| Using surgical asepsis, open outer package of commercial specimen kit | Maintains sterility of specimen container |

| Apply gloves | Prevents introduction of microorganisms into urine specimen from nurse’s hands |

| Client voids 30–60 mL of urine into the toilet or toilet utensil | Flushes any residual microorganisms out of the urethra |

| Collect the next 20–30 mL of urine in a sterile container, e.g. sterile kidney dish or, if dextrous, directly into specimen container | This is the middle stream of urine and is the portion sent for analysis |

| The person completes voiding into the toilet or toilet utensil | The remainder of the urine is not required for collection |

| Pour collected urine specimen into labelled sterile specimen container and remove gloves and perform hand hygiene Ensure client has facilities for their own hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Despatch specimen to the laboratory as soon as possible with the request form, or store specimen in refrigerator | Decomposition and cell growth occur if urine is left standing, and may provide a false result |

| The procedure should be documented | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

| Special note: Indicate on laboratory slip if client is menstruating |

Catheter specimen

A catheter specimen of urine is obtained from a client who has an indwelling catheter. The insertion of a catheter for the sole purpose of obtaining a urine specimen is generally avoided because of the risk of introducing microorganisms into the urinary tract. Collecting a specimen from the end of the catheter that is connected to the drainage tubing should be avoided and best results are achieved if urine is aspirated using a sterile syringe and needle through the sampling port.

Suprapubic bladder aspiration

The suprapubic bladder aspiration procedure is not commonly used but, when necessary, it is performed by a medical officer, using sterile equipment and aseptic technique. It involves the insertion of a needle through the skin over the suprapubic area into the bladder. A quantity of urine is aspirated, placed in a sterile container and despatched to the laboratory. After this procedure the nurse should observe the puncture site for bleeding, and the urine for the presence of blood.

Straining urine

Stones, or calculi, are insoluble substances formed of mineral salts that may develop in the kidneys. They can range in size from microscopic, to the size of grains of sand or gravel, to several centimetres in diameter. If it is known or suspected that a client has developed renal calculi, careful observation of the urine is achieved by straining it to detect the passage of stones. Any stones collected are sent for laboratory examination, which reveals their exact composition and helps to identify their cause. The urine is strained by pouring it through a fine substance such as gauze or filter paper.

Further diagnostic tests

Tests that may be performed to assist or confirm the diagnosis of urinary system disorders include the following.

Blood tests

Blood may be obtained and tested in the laboratory to assess renal function. The tests most often performed are:

• Serum creatinine measurements, which reflect the ability of the kidneys to excrete creatinine, the waste product of energy metabolism

• Blood urea nitrogen levels (BUN), which reflect the ability of the kidneys to excrete urea

• Uric acid levels, which may indicate renal dysfunction if elevated

• Measurement of haemoglobin and haematocrit levels, white blood cell counts, serum potassium and phosphorus levels.

Ultrasound and radiology diagnostic tests

Bladder scans can provide a noninvasive method of assessing residual urine in the bladder and reduce the frequency of catheterisation (Rigby & Housami 2009). These are often portable scans available for use by nurses and other medical personnel and may not require the client to visit a specialist department. More complex ultrasound can identify the size and position of the kidneys and if there are any swellings or cysts associated with them. It will show if there is any dilation (widening) of the tubes which may be the result of blockage. It does not show function.

An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) is an x-ray examination of the urinary tract in which an injection is given into a vein so that the function of the kidneys is shown by passage of the dye through the kidneys and down the tubes (ureters) that drain them to the bladder. A retrograde pyelogram involves the insertion of catheters into the ureters through a cystoscope. Contrast medium is introduced through the ureteric catheters into the pelvis or the kidneys, and x-ray films are taken.

Cystoscopy: the cystoscope is an endoscopic instrument which is passed into the bladder through the urethra in order to inspect its lining. The procedure is carried out either under a general anaesthetic with a rigid instrument or under regional anaesthesia with a flexible cystoscopy.

Computerised axial tomography (CAT) scan of the abdomen may be performed to identify kidney size or structural alterations within the urinary system. It may be done with or without contrast medium.

Renal biopsy

A biopsy of kidney tissue may be taken for microscopic tissue examination. After injection of local anaesthetic a special biopsy needle is inserted through the skin to obtain a sample from the cortex of the kidney. After a renal biopsy the client must be monitored closely for haematuria, rapid weak pulse, pallor or low blood pressure, as these may indicate haemorrhage from the biopsy site.

SPECIFIC DISORDERS OF THE URINARY SYSTEM

Disorders of the urinary system may be classified as congenital, infectious, immunological, degenerative, neoplastic, obstructive, traumatic or those resulting from multiple causes.

Congenital disorders

Certain disorders may be present at birth, although the manifestations may not become evident for some time. Vesico-ureteric reflux is a mechanical problem that may be congenital or acquired. Abnormal backflow of urine from the bladder to the ureter(s) increases the hydrostatic pressure in the ureters and kidneys. Reflux into the kidneys causes damage to the renal parenchyma and reflux nephropathy. In the congenital form the child is born with a short ureter, which often grows to normal size as the child develops and matures, so that the condition resolves. Acquired vesico-ureteric reflux may be caused by repeated UTIs, by inadequate functioning of the detrusor muscles in the bladder or from a high pressure within the bladder as a result of an obstruction (Hockenberry & Wilson 2010). Symptoms of the disorder generally appear only in the presence of a UTI and there may be no symptoms with chronic infection. The condition may not be diagnosed until signs of renal damage become evident.

Polycystic kidney disease is an inherited disorder characterised by grape-like clusters of fluid-filled cysts that enlarge the kidneys. There are two forms of this disorder; one affecting children and the other affecting adults. In its infantile form the disorder manifests as bilateral masses in the kidney areas, with symptoms of respiratory distress and cardiac failure. Adult polycystic disease is frequently asymptomatic until the client is about 40 years of age. Initial symptoms include hypertension, haematuria and low back pain. UTI is common and progression to renal failure is gradual.

Infectious disorders

Infection may occur in any part of the urinary tract, as urine provides an ideal medium for the growth of microorganisms. Most commonly they gain access to the urinary tract by ascending the urethra although, rarely, they may descend from the kidneys to the lower urinary tract.

Pyelonephritis is inflammation of the renal pelvis and may be an acute or chronic condition. Acute pyelonephritis results from bacterial infection of the kidneys, commonly as a consequence of a lower UTI. A client with acute pyelonephritis may experience severe pain or a continual dull ache in the kidney region, as well as pyrexia, nausea and vomiting and fatigue. Rigors may be present, and urination may be frequent and painful. The urine is generally cloudy, blood stained and offensive in odour. Chronic pyelonephritis can result in the formation of renal scar tissue, which may in turn lead to chronic renal failure. This condition most commonly occurs in clients who experience recurrent acute pyelonephritis as a result of a urinary tract obstruction or vesico-ureteric reflux.

Cystitis is inflammation of the urinary bladder, and is usually the result of bacterial contamination. Cystitis is more common in females than in males because of the short length and proximity of the urethra to the bowel and vagina. The urine is generally cloudy and offensive and may contain blood cells. Urethritis, inflammation of the urethra, may result from bacterial infection or traumatic irritation such as catheterisation.

Organisms responsible for infections are numerous: Escherichia coli is a common infective organism; altered hygiene habits, sexual activity or bowel disorders may contribute to the infective process. Other causative organisms may be transmitted sexually, such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea.

Symptoms of urinary tract infections may include dysuria and the presence of pus in the urine but often manifest differently in different age groups (Brown 2002). Table 29.4 outlines the age-related symptoms of UTI.

Table 29.4 Age-related symptoms of UTI

| Younger clients (symptoms tend to be specific) | Older clients (symptoms tend to be less specific) |

|---|---|

| Frequency/urge | May/may not be present |

| Continent | Episodes of incontinence |

| Pyrexia/chills | Not always present |

| Burning of micturition | Seldom present |

| Low back/low abdominal pain | Lower abdominal tenderness |

| Lethargy | Lethargy |

| Loss of appetite/nausea | Loss of appetite |

| Mentally alert | Altered mental state |

adapted from Brown 2002

Degenerative disorders

Degenerative disorders include disorders in which there are degenerative changes in the renal structure or changes in the blood vessels that supply the kidneys. Degeneration occurs over a long period, and the client may not experience any symptoms until significant damage has occurred. Nephrosclerosis is necrosis of the renal arterioles, resulting from untreated or uncontrolled hypertension that impairs the blood supply of the kidneys. Renal damage occurs from a combination of fibrosis of the blood vessels walls and the resulting ischaemia. The client presents with high blood pressure, headaches, visual disturbances and altered neurological functioning. The urine contains protein and blood. If untreated, this condition can lead to renal and cardiac failure.

Analgesic nephropathy results from chronic ingestion of substances containing phenacetin. Aspirin–paracetamol combinations have also been found to cause similar renal tubule damage. The client complains of low back pain, haematuria and the symptoms of uraemia (nausea, vomiting, pruritus, muscle cramps). If end-stage renal failure develops, dialysis or kidney transplantation will be necessary (Berman et al 2012).

Neoplastic disorders

Tumours that arise in the urinary system may be benign or malignant. Kidney tumours are generally malignant and usually well advanced before haematuria, the first and most common sign, appears. Later features include pain as the tumour enlarges and presses on adjacent structures, nausea and vomiting, loss of weight and metastatic symptoms such as bone pain. Wilms’ tumour is a rare malignant tumour of the kidneys that occurs primarily in children (Kidney Health Australia 2012).

Bladder tumours are generally malignant, and more common than kidney tumours. Most occur in men over age 50. Evidence shows that prolonged exposure to certain substances such as aniline dyes is associated with increased incidence of bladder cancer. A variety of other carcinogenic substances, such as artificial sweeteners, are linked to bladder cancer. The prime manifestation of a bladder tumour is intermittent haematuria.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer other than skin cancer in Australian men over the age of 50. Cancer of the prostate is commonly diagnosed through a screening blood test which indicates raised prostate specific antigen (PSA) (Andrology Australia 2011). As the tumour develops it causes the prostate gland to increase in size and causes difficulty in initiating micturition, a feeling that the bladder is not empty after voiding and dribbling of urine after micturition. Acute retention of urine may occur if the flow from the bladder is severely obstructed. Surgical intervention for conditions relating to the prostate can lead to erectile dysfunction and continence issues.

Obstructive disorders

Obstruction of the urinary tract may be caused by factors other than the presence of tumours and calculi.

Benign prostatomegaly (enlargement of the prostate gland surrounding the male urethra) may compress the urethra and cause urinary obstruction. The cause of hypertrophy of the prostate gland is not fully understood but is probably related to hormonal mechanisms. It is more common in men over age 50. The first sign that there may be prostate problems may be when a man experiences the urge to pass urine more frequently, experiencing hesitancy and/or an interrupted stream. Sexual dysfunction is often experienced as the prostate enlarges (Maliski et al 2008). Some men may experience pain at the base of the scrotum and penis (Andrology Australia 2011). A digital rectal examination performed by the client’s medical officer can ascertain if the prostate is enlarged.

Hydronephrosis, or dilation of the renal pelvis, may result from obstruction of the urinary tract. The build-up of pressure behind the area of obstruction eventually results in damage to the kidneys, and renal dysfunction. Causes of hydronephrosis include prostatomegaly, urethral stricture, calculi, congenital abnormalities and neurogenic bladder. The client usually presents with dull lower back pain and tenderness, decreased urine flow, dysuria and haematuria. Infection or renal failure can occur if the problem is not corrected.

Calculi are stones that form in the kidneys and urinary tract. Most stones form in the kidneys and pass down into the ureters or bladder. They are usually composed of calcium salts or uric acid. Multiple small calculi may remain in the renal pelvis or pass down the ureter, while a staghorn calculus remains in the kidneys. Although the precise cause is unknown, predisposing factors in the formation of calculi include some medications, dehydration, metabolic factors, infection, prolonged immobility and urinary stasis (Walton 2008).

The major symptom of calculi is pain, felt as a dull ache while the stone remains in the kidney. Stones which are localised to the kidneys may be treated with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). Stones which pass into the ureter may be treated with ESWL or, if lower down, may be removed using ureteroscopy.

If a stone passes into the ureter, the client may experience excruciating colicky pain that is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

Traumatic disorders

Injuries to the kidney or urinary tract can have serious consequences. Because the kidney receives a large amount of blood from the abdominal aorta via the renal arteries, even a small laceration can cause massive haemorrhage. Injuries to the kidney include contusion, haematoma and laceration. The renal artery or renal vein may be ruptured. Symptoms include haematuria, back and abdominal pain and symptoms of hypovolaemic shock if the injury is severe. Bladder trauma may be associated with pelvic fractures or result from a blunt or penetrating injury. Symptoms of bladder injury include haematuria, dysuria, decreased urinary output, suprapubic pain and tenderness. Scrotal or perineal swelling may occur if urine escapes from the damaged bladder into surrounding tissues.

Disorders of multiple cause

Chronic renal failure is the gradual loss of functional nephrons and may be due to several causes, including chronic kidney infections, polycystic kidneys, renal vascular disease, hypertension and obstructive diseases such as calculi, nephrotoxic agents and diabetic nephropathy. The condition produces major changes in all body systems.

Clinical Scenario Box 29.1

84-year-old Alfred has been to see his doctor for a routine examination. On questioning he revealed that he has been experiencing difficulty with ambulation due to joint pain in his hip. Blood tests show he has slightly elevated PSA and, on digital rectal examination, an enlarged prostate. A transurethral ultrasound (TRUS) and prostatic biopsy has been performed.

On questioning, Alfred admits to having urinary frequency and nocturia, explaining that he often has to get up to ‘spend a penny’ at night. Upon further questioning he explains that he has noticed increased difficulty with starting and stopping urination and when it does start it is very slow. This has happened over several months but he has been too embarrassed to seek medical advice. Alfred also describes symptoms of joint stiffness and discomfort which make it difficult to do many of the things he once used to do.

It consists of four phases: diminished renal reserve, renal insufficiency, renal failure and end-stage renal disease. During the first phase, renal damage occurs but the client may be asymptomatic. With renal insufficiency the kidneys still function, but urinary concentration is impaired and blood urea levels are elevated. The renal failure stage produces uraemia, metabolic acidosis, electrolyte imbalance and impaired urine dilution. In the end stage, renal function is severely impaired and most other body systems are affected. When renal function is impaired to such an extent that conservative treatment is no longer effective, dialysis therapy and/or kidney transplantation are necessary (Health Insite 2012).

INCONTINENCE

Continence can be defined as the ability to control excretion in a timely and appropriate manner. Incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine and can occur at any time. Causes for this distressing symptom can be as a result of infection, changes to the neurological or endocrine system, physiological, pharmacology or psychological changes and other idiopathic causes (Naish 2008). In children bedwetting (enuresis) is a relatively common occurrence which may resolve over time. Clients who experience involuntary leakage frequently lack self-esteem, and may experience physical discomfort and social isolation. Incontinence in adults is categorised into five main categories:

• Urge: the sudden desire to void resulting in involuntary leakage.

• Stress: the involuntary loss of urine when exercising, coughing or laughing

• Overflow: incomplete evacuation of urine from the bladder which results in a pool of urine remaining in the bladder. Not only is this a reservoir for bacteria but pressure can build up, resulting in overflow of urine being involuntarily released

• Transient: sudden onset of incontinence often associated with infection

• Reflex: loss of bladder control, often the result of neurological trauma or disease.

There can also be a mixed presentation of symptoms. Sensitive probing concerning the history of continence and accurate reporting aids assessment of appropriate initiatives.

Life span issues

Children: micturition is normally under voluntary control by about 2–3 years of age; however, children often experience enuresis into their school years. There are a variety of interventions to assist children experiencing this situation and effective data collection including incidence, external factors such as stress or emotional trauma, absence of infection, pharmacology or disease profiles is necessary. Children frequently outgrow the symptom but the psychosocial implications can have a long-term negative impact (Caldwell et al 2009; Cox 2009).

Adolescence: incontinence can be continuous throughout childhood as a result of infection, toilet avoidance, (especially at school), constipation or disease. This stage of development is also a time when some adolescents become sexually active and incontinence related to a bladder infection (cystitis) and associated vaginitis or epididymitis may be experienced. Some adolescents are often reluctant to seek help and the need for sensitivity in responding to this age group is vital (Weaver 2008).

Pregnancy and postpartum incontinence: the effectiveness of pelvic floor exercises in helping to improve the musculature of the pelvic region has long been acknowledged and use of these exercises has resulted in improvement in the post childbirth incidence of incontinence (Day & Goad 2010). During pregnancy, mechanical and hormonal factors cause changes in renal physiology, most commonly resulting in frequency of voiding and stress incontinence. Many postpartum changes, including damage to the pelvic floor during vaginal delivery, have long-term continence effects and these are less acknowledged, with many mothers assuming that involuntary loss of urine is normal after the birth of a baby. This condition has an adverse effect on the mother—from physiological, psychological and sexual perspectives (Kok et al 2008).

Menopause: urge and stress incontinence increases in women post menopause, and complications such as obesity and type 2 diabetes can exacerbate the symptoms (Mishra et al 2008).

Older adults: while continence issues in adolescents and adults is experienced mainly by women, prostatic enlargement in men and the resultant effects of surgery increase the incidence of incontinence in men. The increase in metabolic syndrome in men and women, obesity and neurological changes also contribute to incontinent events. There is frequently a mixed aetiology (causes) in this age group.

Nursing interventions

Interventions can only be effective when a thorough assessment has been completed. Incontinent issues are highly individualised and the nurse needs to respond to each individual client’s needs. Therefore, care plans must be initiated in consultation with the patient or their significant others (see Nursing care plan 29.1).

• Using standard precautions for dealing with body fluids

• Use accurate documentation and assessment to aid all health professionals in treatment

• Encourage client to consume fluids unless contraindicated; at least 1500 mL daily, as an inadequate fluid input may further decrease the functional capacity of the bladder

• Recommend weight reduction where applicable

• Establish and maintain Kegel exercise routine (Box 29.1)

• Use of the NeoControl® or similar chair—which creates therapeutic pulsed magnetic field to provide powerful stimulation of vital pelvic floor muscles—as an adjuvant to pelvic floor exercises. These chairs are being increasingly deployed in the community setting

• Be aware of the client’s physical and social environment, for example, wet clothing or bedclothes should be removed immediately and taken from the room to prevent offensive odours. The client should be provided with clean dry clothing and applicable continence aids. Air freshener should be available

• Provide easy access for ambulant clients to the toilet, which should be clearly marked and have suitable rails and/or equipment to assist them to void comfortably. Non-ambulant people should be provided with toilet utensils relevant to their need. Some clients may find it easier to use a commode and men often find it easier to void while standing. Any request for use of toilet facilities should be responded to promptly

• Keep the skin clean and dry as constant moisture on the skin may lead to excoriation and the development of decubitus ulcers. When the client is incontinent their skin should be washed with mild soap and water and gently dried. Particular attention is paid to the genital area, the groin and the crease between the buttocks

• Be aware of the various medications that may be prescribed in the management of incontinence, and their side effects; for example, antibiotics to treat a UTI

• Continue to screen urine for infection or underlying disease

• Ensure continence aids are suitable, affordable and adequate for the individual. The PadNavigator™ helps you find the right continence pad when a disposable absorbent product has been recommended following a continence assessment (see www.brightsky.com.au/ClinicalSupport.aspx)

• Where necessary provide a referral to a specialist continence nurse and more information such as from the Continence Foundation of Australia

• Assist in changes to lifestyle changes and planning, e.g. by use of the National Toilet Map.

Nursing care plan 29.1 A client with urinary incontinence

Assessment

Mrs Jones (80 years) had been admitted to the acute ward the previous evening following a fall. This morning the nurse noticed an odour of urine and felt the sheets were damp. Mrs Jones acknowledged she had difficulties getting to the toilet in time and was deeply traumatised by the event. She repeatedly asked the nurse not to tell anyone, and said that she managed well at home.

Goals

Client will report relief from urinary incontinence or a decrease in incidence

Client will gain confidence in ability to self-manage with education and management strategies

Client will maintain skin integrity and social hygiene effectively

Nursing interventions and rationales

Perform a complete urinalysis to determine underlying medical disorders

Maintain bladder diary for at least 72 hours to establish continence pattern

Review all medications in consultation with the medical officer to determine if any are thought to be contributing to the incontinence

Review client fluid intake and types of fluid consumed, as alcohol irritates the bladder and caffeine can cause urgency

Provide the client with information about the Continence Foundation of Australia or the New Zealand Continence Association to seek further support

Evaluation

Client reports urinary continence or reduced incidence of incontinence episodes

Client reports maintenance of pelvic floor exercises at least three times daily

Client’s fluid intake is at least 2 L per day (if not contraindicated by coexisting disease)

Client understands the role and function of the Continence Foundation of Australia or the New Zealand Continence Association

Box 29.1 Pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises

Exercise program for making pelvic floor muscles stronger:

• Check with a continence adviser or physiotherapist to ensure that exercises are being performed correctly

• Find the right muscles: when passing urine, stop the flow mid-stream. Then relax and finish passing urine. The muscles you tighten and pull upwards to stop the flow of urine are the pelvic floor muscles. Tighten the muscles around the anus by imagining that you are trying to stop passing wind

• Test your muscle strength: women—place one or two clean fingers in the vagina and tighten the pelvic floor muscles; men—press one finger on the area between the anus and scrotum; when the pelvic floor muscles are tightened, this area will move up and away from the finger

• To do the exercise, squeeze the muscle identified and hold for a count of 10 seconds. Relax for a count of 10 seconds. It may take 2 weeks to be able to hold for 10 seconds

• Do the exercise three times a day: 15 in the morning, 15 in the afternoon and 20 at night. Or for 10 minutes three times a day. Try to work up to 25 repetitions at one time. It will take about 2 weeks to notice a difference. Within a month of regular exercise, there should be a decrease in instances of incontinence

(adapted from deWit 2009)

Specific interventions

• Stress incontinence: encourage use of pelvic floor exercises

• Urge incontinence: implement planned bladder-retraining regimens to promote continence or to modify incontinence. These regimens often include timed intervals for toileting; for example, the regimen may start at 2-hourly periods and, if continence is achieved, then the timing is increased until a suitable pattern is attained. Kegel exercises may assist in maintaining continence

• Enuresis: use monitoring devices with an alarm system

• Consider a penal sheath (condom drainage) with tube and collection bag for those male clients suffering neurological damage to the bladder. Before any appliance is fitted, the penis must be cleaned and dried and observation made to ensure that the foreskin is not retracted. The appliance is placed over the penis and secured in position. A special adhesive tape is commonly used and care must be taken to ensure that it is not applied too tightly. The tubing from the appliance is connected to either a bedside collection bag or a leg bag. The penis should be observed for oedema and discolouration; if detected, the appliance is removed immediately and reapplied more loosely. At least every 24 hours the appliance is removed and the penis cleaned and dried before reapplication. Use of such appliances should be discontinued if there are signs of skin excoriation, persistent oedema of the penis or UTI. Refer to Procedural Guideline 29.2.

Procedural Guideline 29.2 Applying a condom catheter

(adapted from deWit 2009)

| A condom catheter is used for a male client who is incontinent but can void on his own |

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assess the need for and the client’s willingness to use a condom catheter | If the client is unwilling, he may detach the condom catheter |

| Assess the condition of the skin on the penis. Use measuring device for circumference of penis | Urine incontinence places the skin at risk for breakdown |

| Collect equipment: condom catheter; disposable gloves, adherent tape, basin, warm water, soap, washcloth, towel, urine collection bag with drainage tubing or leg bag and straps | Promotes work effciency |

| Explain the procedure to the client and maintain privacy | Reduces anxiety |

| Place the client in a supine position and cover the upper torso with a blanket, then fold the sheet down so it covers the legs and can be lowered to expose the genitalia | Provides comfort and prevents unnecessary exposure |

| Prepare the urinary drainage bag for easy attachment to the condom catheter. Roll the wider tip of the condom sheath towards the narrower tip | Prepares the system for use |

| Perform hand hygiene and don disposable gloves | Prevents transfer of microorganisms |

| Wash and dry the penis and surrounding skin | Cleanses the skin before application of the condom device |

| Apply the double-sided elastic tape in a spiral fashion from the base of the penis downwards (or as manufacturer indicates) | Provides a surface on which the condom catheter can be attached without impeding circulation in the penis. Some condom catheters attach with a velcro strip over the sheath |

| Grasp the penis along the shaft. Hold the condom sheath at the tip of the penis and smoothly roll the sheath onto the penis, leaving 2.5–5 cm of space between the tip of the penis and the drainage tube of the condom sheath | Positions the condom catheter on the penis. Allows free passage of urine into the collecting tube and drainage bag |

| Position the penis downwards and connect the drainage tube to the collection bag | Allows urine to flow into the collection bag |

| Return bed to the low position and make the client comfortable; place call bell within reach | Provides comfort and security |

| Check the penis after 30 minutes and then every 2 hours to ensure catheter is not twisted | Ensures that the catheter is not too tight and impairing circulation; twisting of the catheter impedes urine fow |

| Remove gloves and wash hands | Prevent cross-infection |

| Document the date, condition of the genital area, size and type of catheter applied, type of drainage collection attached to the catheter, amount, colour and character of urine obtained in bag, and the client’s tolerance of the procedure | Documents the use of condom catheter |

(adapted from deWit 2009)

CATHETERS

A catheter is a tube that is inserted into the bladder to drain urine. It is inserted through the urethra or, less commonly, through a small incision in the suprapubic area. A catheter may be inserted to empty the bladder then removed immediately, or it may be left in the bladder. A catheter that remains in the bladder may be either clamped and released at specified intervals, or connected to tubing and a bag to enable continuous drainage. A catheter that remains in the bladder is referred to as indwelling. A self-retaining catheter is used for this purpose. It has a small balloon which sits at the neck of the bladder to prevent the catheter falling out, and which is filled with sterile water after the catheter is inserted.

Catheters are graded according to the French scale, and the larger the number the larger the lumen of the catheter. Sizes range from 1 to 30 French gauge (Fg), and the size is selected to suit the client’s needs. The Catheter Compass™ helps you select the right catheter for a client when a urological or continence review has resulted in the recommendation of an intermittent or indwelling catheter (see www.brightsky.com.au/ClinicalSupport.aspx). It is important that a suitable size is selected to avoid leakage of urine around the catheter, or trauma to the urethra or bladder. Indwelling catheters are for single use only.

Reasons for catheterisation

One of the most common nosocomial infections in hospital is urinary tract infection and many of these can be attributed to catheterisation (De Jaeger 2011). As a result, catheterisation is now performed only when considered absolutely necessary, which may include when:

• Monitoring renal function and output hourly during a critical event

• Facilitating a bladder washout or instilling medication

• Acute/chronic retention occurs

• Using investigative procedures such as urodynamic studies.

Use the Bright Sky Catheter Compass™ to help you identify the type of catheter that best suits the client (see www.brightsky.com.au).

Insertion of a catheter

The procedure of catheter insertion is called catheterisation and is performed using sterile equipment and aseptic technique. Standard precautions are maintained by all personnel involved. As a catheter can cause trauma to the urethral or bladder mucosa and is a potential source of UTI, it is inserted only when absolutely necessary. The basic requirements are:

If the catheter is to be indwelling, you also need:

In addition to preparing the equipment, it is necessary to prepare the client by ensuring adequate lighting and privacy, placing the client in a supine position with legs extended and promoting comfort and privacy during the procedure. See Procedural Guidelines 29.2 and 29.3.

Procedural Guideline 29.3 Catheterisation of females

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ensure adequate lighting | Visualisation of the urethral meatus is essential |

| Place the client in the dorsal position, with knees flexed and separated, and feet slightly apart on the bed | Provides a clear view of the urethral meatus |

| Ensure that the client is adequately draped | Reduces embarrassment |

| Place all the equipment in a convenient location | Facilitates easy access to it throughout the procedure |

| Perform hand hygiene. Don gloves and goggles | Prevents cross-infection |

| Use sterile towels to create a sterile feld around the genital area | Reduces risk of equipment becoming contaminated during the procedure |

| Cleanse genital area and urethral meatus, wiping from front to back | Reduces risk of introducing microorganisms from the genital/anal area into the urinary tract |

| Before inserting a self-retaining catheter, infate and deflate the balloon to check for patency | Necessary to check balloon for leakage before insertion |

| With sterile forceps, hold the catheter about 7 cm from its tip or follow manufacturer’s instructions | Assists in controlling the direction of the catheter |

| Dip tip of catheter into the sterile water-based lubricant | Facilitates easier and more comfortable insertion |

| Place distal end of catheter into a sterile receptacle positioned between the client’s legs | Urine will flow into the receptacle, not onto the bed |

| Keeping the client’s labia separated, insert the catheter tip into the urethral orifce. Advance the catheter until 4–7 cm have been inserted | Length of catheter inserted must be in relation to the anatomical structure of the urethra. The average female urethra is about 3.8 cm long |

| If catheter is not to be left in, remove it gently when urine ceases to fow, or the required amount of urine has drained | Catheters are not left in any longer than necessary, and are removed gently to avoid discomfort |

| If a self-retaining catheter is being used, infate the balloon, having first ensured that the catheter is draining adequately according to manufacturer’s instructions | Infated balloon keeps the catheter in the bladder. Inadvertent infation with the balloon in the urethra causes trauma and pain |

| Connect the indwelling catheter to the drainage bag and support the bag in a holder at the side of the bed. Alternatively, a clamp is placed on the end of the catheter | Urine fows from catheter, along the tubing and into the bag. Intermittent drainage may be prescribed |

| Attach the catheter to the client’s inner thigh with hypoallergenic tape, and pass the catheter over the thigh | Prevents in–out movement of the catheter and prevents tension on the urethra |

| Position the tubing so that it is not obstructed by the client’s weight or by tight bedclothes | Avoids blocking the flow of urine through the tubing |

| Remove excess lubricant from the client’s genital area. Replace bedding and assist client into a comfortable position | Helps promote comfort |

| Remove and attend to the equipment in the appropriate manner. Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Document the procedure, including the amount of water instilled into the balloon and colour and characteristics of the urine | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented. When the catheter is to be removed, it is important that the water is first withdrawn and the balloon deflated to prevent trauma to the urethra |

Bladder irrigation

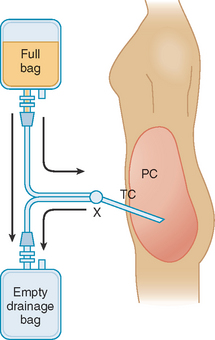

Bladder irrigation or washout may be performed to ensure patency of the catheter, to remove sediment or blood clots or to introduce an antibiotic or bacteriostatic agent. Bladder irrigation may be continuous or intermittent. To prevent urinary tract obstruction continuous irrigation may be necessary to flush out small blood clots that can form after prostate or bladder surgery. During bladder irrigation, sterile equipment and aseptic technique are used to avoid introducing microorganisms. A triple lumen catheter is needed to perform bladder irrigation. One lumen is used to introduce the irrigating solution into the bladder, a second lumen allows the fluid to drain out and the third lumen allows the instillation of fluid into the balloon that holds the catheter in the bladder.

For continuous irrigation, a container of irrigating solution is suspended on a stand and the tubing from the container is attached to the catheter. Drainage tubing from the catheter is attached to a urine collection bag positioned below the level of the client’s bladder. A clamp is used to regulate the rate at which the solution flows into the bladder. During irrigation the inflow and outflow tubing is checked to ensure the free flow of fluid. The outflowing fluid is checked for changes in the appearance and presence of blood clots. Both the inflowing and the outflowing fluid must be measured and documented and the collection bag emptied as necessary. The outflow volume should be greater than the inflow volume—allowing for urine production.

Intermittent irrigation involves the gentle introduction of small amounts of prescribed solution. Using a syringe, the solution is introduced into the distal end of the catheter. Small amounts, 30–50 mL for example, are introduced in succession and usually allowed to drain out by gravity. The technique is repeated until the prescribed amount of solution has been used, or until the return fluid is clear. The solution being introduced and returned is measured and documented, and the return fluid observed for changes in appearance or presence of blood clots.

Removal of a catheter

Depending on how long a catheter has been in position, the medical officer may prescribe bladder retraining before its removal. Bladder retraining involves clamping the catheter for specified periods, such as 2–4 hours, then releasing it to empty the bladder. This technique is repeated for several hours to help restore the bladder’s muscle tone. Removing a catheter requires aseptic technique. Key aspects related to the procedure and after care include:

• Obtaining a specimen of urine for laboratory analysis if necessary, before the catheter is removed

• Ensuring that all water from the balloon is withdrawn before removing the catheter

• Gently withdrawing the catheter from the urethra, using aseptic technique. If this appears to be difficult ask the patient to relax and gently cough. The catheter may also need a slight rotation to aid withdrawal

• Offering a bedpan or urinal immediately after the catheter is removed, as catheter removal often creates a desire to void

• Encouraging the intake of fluids to stimulate urine production, to dilute the urine and to help decrease any discomfort the client may experience on resuming voiding

• Observing and documenting urine output after the catheter is removed. If the client is voiding only small amounts, the bladder may not be emptying completely, and the medical officer should be informed

• Observing for and reporting any difficulty with voiding, incontinence, dribbling or bladder distension

• Documenting the date and time the catheter was removed and the client’s response to the procedure

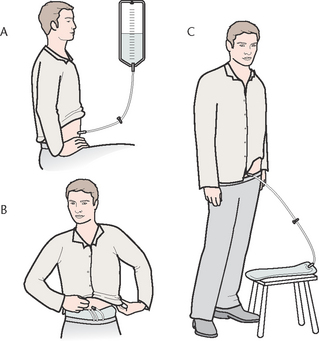

Intermittent catheterisation

Intermittent catheterisation is either a one-off procedure to assess the urine within the bladder or the insertion and removal of a catheter several times a day to empty the bladder. Intermittent catheterisation is widely used in neurogenic bladder dysfunction such as spinal cord injury, spina bifida, multiple sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Intermittent catheterisation reduces the incidence of UTI and improves quality of life and allows for self-catheterisation, giving greater independence to the client (Newman & Wilson 2011). Side effects can include bleeding, urethritis, stricture and the potential for UTI. Men may have difficulty inserting the catheter past the prostate while women may have difficulty identifying the urethra (Colpman 2010).

Nursing interventions

• Use standard precautions when addressing all catheter care needs

• Maintain accurate and frequent records of catheter care and status of output

• Use accurate documentation and assessment to aid all health professionals in treatment

• Support client in accessing further information: clients may find the changes to body image profoundly distressing and assistance may be required in areas of psychosocial and sexual support

• Encourage fluids if medically approved

• Encourage mobility where feasible

• Perform a routine urinalysis to screen for infection or for further underlying disease

• Ensure disposal of urine is via the toilet or as per facility protocol.

Nursing care after the insertion of an indwelling catheter is similar for both male and female clients and is planned and implemented to promote comfort, maintain the flow of urine and minimise the possibility of a UTI. The nurse needs to ascertain whether the catheter is to be clamped and released at specified intervals to provide intermittent drainage or if it is to be connected to a drainage bag for continuous drainage. If intermittent drainage has been prescribed, the end of the catheter is clamped. At specified intervals, for example, every 4 hours, the clamp is released to enable the urine that has accumulated in the bladder to drain. Aseptic technique should be used during this procedure to prevent the entry of microorganisms into the open catheter. An intermittent drainage regimen is commonly implemented before removal of an indwelling catheter, to promote and restore any lost bladder tone.

If continuous drainage has been prescribed, actions to promote free flow of urine and prevent stasis of urine include:

• Standard precautions to be observed at all times and constant awareness of increase for potential of infection in catheterised patents considered at all times

• Positioning the tubing so that it is not obstructed or kinked in any way (see Clinical Interest Box 29.1)

• Maintaining the tubing and drainage bag at a level below the client’s bladder

• Ensuring that the client has a fluid input of at least 2000 mL daily, unless this is contraindicated

• Taping the catheter to the inner thigh to reduce movement of the tube to prevent ascending infection. If continuous drainage is being used, the system should remain closed and sterile. If it is necessary to disconnect any part of the system, an aseptic technique must be used. To promote comfort and reduce the risk of ascending infection, the urethral meatus and catheter near the point of entry should be cleansed at least twice daily and whenever necessary, for example, after a bowel action. Cleansing should be performed by wiping in the direction away from the urethral meatus to avoid contaminating the urinary tract. An uncircumcised male’s foreskin should be retracted before cleansing, and replaced after cleansing

• Observing the urine at least 8-hourly and any deviations from normal reported immediately. Any inflammation of the urethral meatus, or pain or distension over the bladder area, should also be responded to swiftly. The nurse should observe for signs that urine is not bypassing or leaking around the catheter. This may be caused by bladder spasm, blockage of the catheter or tubing or insertion of a catheter of incorrect size. If leakage occurs it should be reported and documented. To test the patency of a catheter or to remove clots or sediment, a registered nurse may perform irrigation of the catheter or the bladder after review by a medical officer

• Taking care not to allow the urine to be drained too rapidly when a catheter is being used to drain urine from an over-distended bladder, for example, during acute retention of urine. Decompressing the bladder too quickly may result in bladder trauma or physiological shock; therefore, no more than 1000 mL should be released at any one time

• Using urine meters (burettes) in conjunction with drainage systems when precise measurements of urine output, such as hourly measurement, are required. A meter is commonly a rigid plastic container attached to the drainage system and is calibrated to measure small volumes

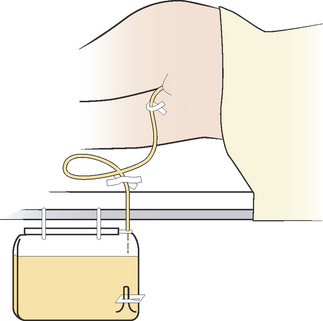

• Using disposable closed drainage sets consisting of tubing and a collection bag. The collection bag is emptied at specified intervals or when it is almost full, and the tubing left in position until the entire set is changed or removed (Fig 29.6). The bag is emptied by releasing the valve at the bottom of the bag, using aseptic technique to avoid introducing infection

• Observing the key steps related to emptying and changing collection bags as outlined in Procedural Guideline 29.4.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 29.1

If a client with an indwelling catheter reports that they have a feeling to void, ensure that you investigate this. The problem could be caused by the catheter being kinked, twisted or blocked.

Procedural Guideline 29.4 Emptying or changing collection bags

| To empty a bag: before commencing review manufacturer’s information and medical instructions |

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Swab the outlet valve on the collection bag with an alcohol swab | Reduces risk of introducing microorganisms |

| Place the jug below the valve and release valve | Allows urine to drain from the bag into the jug |

| When the bag is empty, tighten the valve | Prevents subsequent drainage of urine out of the bag |

| Swab the valve with an alcohol swab | Removes any traces of urine, and prevents cross-infection |

| Remove the jug, observe the urine and measure or test it if necessary | Assists in evaluating the client’s urinary status |

| Empty and clean the jug, remove gloves, perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report any deviations from normal and document accordingly | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

| To change a bag | |

| The first six steps are as for emptying a bag, as above | |

| Swab the connection site where the system is to be disrupted | Reduces risk of introducing microorganisms |

| Clamp the catheter and remove the bag, and/or bag and tubing. Connect the catheter or tubing to the new bag | Prevents leakage of urine during the change |

| Swab the connection site with an alcohol swab | Removes traces of urine and prevents cross-infection |

| Release the clamp and ensure that the tubing and bag are positioned correctly | Allows urine to fow |

| Observe the urine and measure or test it if necessary | Assists in evaluating the client’s urinary status |

| Remove the soiled articles and attend to them in the appropriate manner. Remove gloves, perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report any deviations from normal and document accordingly | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

SPECIALIST UROLOGY NURSING ACTIVITIES

The nurse may be required to assist in the preparation of a client before specific diagnostic procedures and to monitor their condition afterwards. Catheterisation may be necessary to obtain a specimen of urine or to treat acute urinary retention.

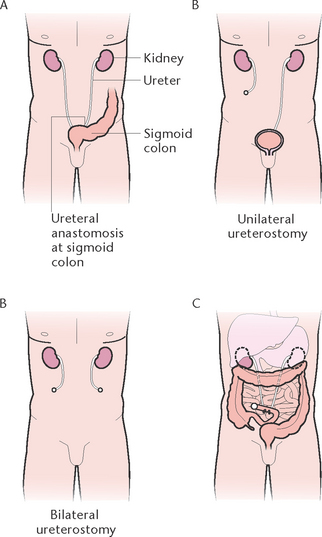

Urinary diversion

A client whose bladder has been removed, for example because of malignancy, will require urinary diversion. Various surgical techniques that divert the flow of urine are available (Fig 29.7):

• Ureterosigmoidostomy involves the implantation of the ureters into the sigmoid colon, resulting in urine being passed via the rectum

• Cutaneous ureterostomy involves bringing the ureters through the abdominal wall, with urine draining out through the stoma(s) into an ostomy appliance

• Ileal conduit involves resection of part of the ileum. Both ureters are implanted into the proximal end of the ileal segment, and the distal end of the ileum is brought through the abdominal wall to form a stoma. The urine then drains out through the stoma into an ostomy appliance. This particular surgical technique is generally considered to be the most satisfactory if urinary diversion is required.

Care of the client with a urinary stoma is similar to the care required by a client who has a stoma created for the passage of faeces. The main aspects of care are the selection and management of ostomy appliances, care of the stoma and surrounding skin and provision of psychological support.

Dialysis

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and dialysis treatment is a serious health issue requiring a multifaceted approach to treatment, including medication, monitoring of fluid and diet intake and a plan which incorporates the concerns and impact on family and carers (Bonner & Douglas 2008). Dialysis is a specialised nursing function which centres on delaying progression of disease and preventing further complications and administering and maintaining the dialysis program. It involves the transfer of solutes across a semi-permeable membrane, and the removal of waste products, excess salts and fluid from the blood. The method of dialysis is determined by the client’s condition and may be performed by the client at home if the facilities are available, in a specialised unit or a in mobile dialysis unit in rural and remote settings.

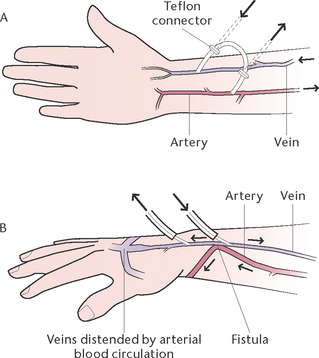

There are two types of dialysis: peritoneal dialysis (Figs 29.8 and 29.9) and haemodialysis.