CHAPTER 30 Bowel elimination

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the anatomical position and structure of the digestive system

• Describe the physiological functions of the various areas of the digestive system

• Explain how the presence of bile influences the colour of faeces

• Describe normal faeces and the defecation process

• Identify the factors that affect bowel elimination

• Apply appropriate principles when implementing nursing actions to assist the individual to meet their bowel elimination needs

• Perform procedures described in this chapter, accurately and safely, including the observation, collection and testing of faeces, and assisting clients with bowel elimination

• Briefly describe the specific disorders of the digestive system

• Describe the diagnostic tests that may be performed to assess digestive system function

• Consider the psychosocial aspects of care from a person-centred and relationship care perspective

• Employ critical thinking to provide care for clients with alterations in bowel elimination

The digestive process enables consumed food and fluids to be broken down into nutrients and electrolytes that can be absorbed by the body for cell energy and function. The variety of factors that influence normal bowel elimination are explored in this chapter. Observation of the individual’s ability to eliminate faeces, together with observation of the faeces, provides the nurse with an objective assessment of the client’s bowel elimination status. As a result, nursing care may be planned and implemented in conjunction with the individual and other healthcare providers to meet bowel elimination needs in a dignified and appropriate manner.

I have suffered with constipation all my adult life. I never had breakfast as I was often dashing off to work and then drank coffee during most of my working day. Laxatives brought temporary relief but sometimes led to me being caught in embarrassing situations! I now realise that changes to my diet and eating habits, exercising more and altering and increasing what I drank have had a positive impact on my bowel health.

THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

The digestive process enables consumed food and fluids to be broken down into nutrients and electrolytes that can be absorbed by the body for cell energy and function. This process produces waste products that must be eliminated regularly. Healthy bowel function is maintained by routine elimination habits, a nutritional diet with the recommended amount of fibre and fluid intake and daily mild exercise to stimulate colonic motility. The multiplicities of factors which can affect normal bowel elimination are explored in this chapter. Observation of the individual’s ability to eliminate faeces, together with observation of the faeces, provides the nurse with an objective assessment of the client’s bowel elimination status.

Every cell in the body requires energy to carry out its normal functions. Cellular energy is produced when nutrients in food are broken down and absorbed. Solid wastes that accumulate during the digestive process must be eliminated. The digestive system is the means by which food is ingested, digested and eliminated. In the digestive tract, food is digested to its elemental components: nutrients, fluid and electrolytes. The digested elements are absorbed into the bloodstream for transport to all body cells, and the solid wastes that accumulate during digestion are excreted from the body.

Anatomy

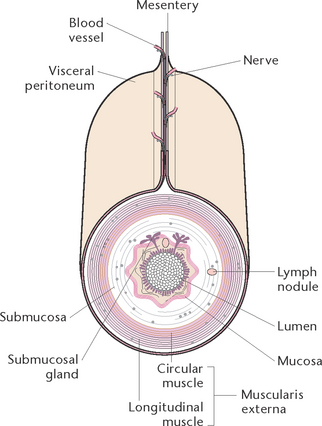

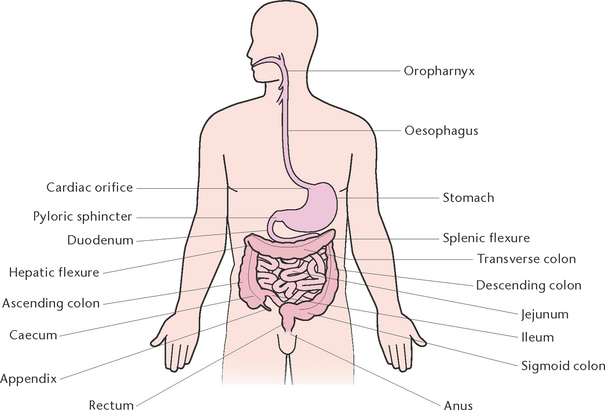

The digestive system is comprised of the gastrointestinal (GI) or alimentary tract and the accessory organs of digestion which include salivary glands, liver, pancreas and gallbladder (Berman et al 2012). The GI tract is a muscular tube about 9–10 m in length, which extends from the mouth to the anus (Fig 30.1). The structure of the GI tract is similar for most of its length and consists of an outer covering, middle layers of involuntary muscle and connective tissue and an inner mucous membrane lining (Fig 30.2).

The outer covering of the GI tract consists of fibrous tissue (the serosa) or, in the abdomen, the peritoneum. The peritoneum is a double-layer serous membrane that secretes serous fluid to prevent friction between the abdominal organs. The two layers of the peritoneum are kept proximate and separated by peritoneal fluid. The peritoneum forms a lining for the abdominal cavity (parietal layer) and a covering for most of the abdominal organs (visceral layer). The mesentery, which is formed by the peritoneum, covers the intestines and attaches them to the posterior abdominal wall.

The innermost layer of the GI tract is composed of connective tissue (the submucosa), which contains many large blood and lymph vessels, and an inner lining of mucous membrane (the mucosa), which secretes mucus into the digestive tract.

The organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, the oropharynx, the oesophagus, the stomach, the small intestine and the large intestine.

The mouth

The mouth, or oral cavity, has boundaries of muscle and bone and is lined by mucous membrane. The lips protect its anterior opening, the cheeks form the lateral walls, the hard palate forms its anterior roof and the soft palate forms its posterior roof. It also contains the uvula which is a finger-like muscular projection hanging down from the midline of the soft palate.

Components of the mouth

The mouth contains the tongue, the teeth and the salivary glands. The tongue consists of a mass of voluntary muscle and is covered by squamous epithelium. On the upper surface of the tongue there are many small projections called papillae, which contain taste buds, the sensory endings of the nerve that perceives taste. The tongue is a very mobile organ which is important in the chewing (mastication) of food, assists in swallowing and is essential for speech.

The teeth are embedded in the maxillae and the mandible. All teeth have the same basic structural organisation but differ in shape and size. Each tooth is made up of an ivory-like substance called dentine; a central pulp cavity containing blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves and connective tissue; and a thin layer of enamel covering the crown. In children there are 20 deciduous (milk) teeth, consisting of 10 in each jaw; in adults there are 16 permanent teeth in each jaw. In each jaw there are four incisors, used for biting; two canines, used for tearing; four premolars, used for crushing; and six molars, used for grinding. A wisdom tooth is the third molar tooth and it is the last tooth to erupt. Wisdom teeth usually erupt from ages 18 to 25 years.

The salivary glands, of which there are three pairs, pour their secretions into the mouth and are accessory digestive organs.

The oropharynx

The oropharynx is the muscular canal forming the passage between the oral cavity and the major parts of the GI tract. Lined by mucous membrane, it is a tube about 13 cm long and is continuous with the nasopharynx above and the oesophagus below. Through the act of swallowing, masticated food formed into a bolus is pushed into the oesophagus by the muscles of the pharynx. Together with the other two sections of the pharynx, it forms part of the respiratory tract. The tonsils are situated in the palatine arches of the pharynx.

The laryngopharynx

The laryngopharynx is a common passageway for both food and air. At the base of the laryngopharynx is the oesophagus which controls swallowing from breathing. Swallowing air can lead to belching and discomfort and inhaling food or liquid causes coughing and, in severe cases, respiratory distress.

The oesophagus

The oesophagus is a muscular tube about 20–25 cm long, extending from the pharynx above to the stomach below. It lies behind the larynx and trachea, in the midline through the neck and thorax, and passes through the diaphragm to join the stomach. The oesophagus has an outer layer of fibrous tissue, a layer of involuntary muscle, a layer of connective tissue and a lining of mucous membrane. The function of the oesophagus is to carry food to the stomach by means of peristaltic action.

Peristalsis is a wave-like progression of alternate contraction and relaxation of the muscle fibres of the oesophagus or intestines, by which contents are propelled along the GI tract. At rest, the opening between the oesophagus and pharynx (oesophageal sphincter) is closed. During swallowing the muscles contract causing the sphincter to open; allowing the bolus of food to pass down into the oesophagus. A wave of contraction in the circular muscle layer then propels the bolus down to the stomach. The bottom end of the oesophagus acts as a functional sphincter, as the peristaltic wave approaches the sphincter; the muscle relaxes and allows food to enter the stomach. The sphincter then closes again and prevents regurgitation of gastric contents back into the oesophagus.

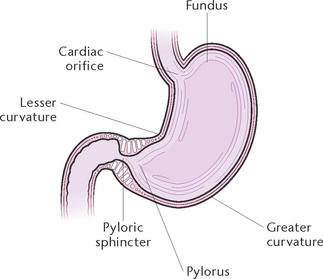

The stomach

The stomach (Fig 30.3) is commonly described as being ‘J shaped’, but the size and shape of the stomach varies according to its contents. The stomach is divided into four areas: the fundus (the upper portion); the cardia, where the oesophagus joins the stomach; the body, or main part of the stomach; and the pylorus (the narrowed lower portion).

The opening of the oesophagus into the stomach is called the cardiac orifice, and is surrounded by a functional sphincter called the cardiac sphincter. The pyloric orifice is the opening between the stomach and the small intestine and is surrounded by the pyloric sphincter, which consists of a thickened layer of circular muscle and is normally partly open. Peristaltic waves in the stomach push parts of the gastric contents through the orifice and into the duodenum and then closes the orifice.

The stomach acts as a temporary reservoir for food, allowing the digestive enzymes time to act, breaks up the food into a liquid state by rhythmic muscular contraction of its walls, and produces gastric juice, which contains:

• Hydrochloric acid, which is released in response to the hormone gastrin, and activates pepsins, providing an optimal pH for pepsin activity, and destroys bacteria

• Intrinsic factor, which is vital for the absorption of vitamin B12 from the diet, which is needed for the development of erythrocytes

• Mucus, which is secreted by the surface cells of the stomach mucosa and forms a lining that protects the mucosal cells from the gastric contents

• Gastric enzymes (pepsinogens), which are inactive until exposed to hydrochloric acid, when the active pepsins are released. Pepsins act as a catalyst in the chemical breakdown of protein, forming polypeptides and free amino acids

The small intestine

The small intestine is a coiled muscular tube about 5–6 m in length, extending from the pyloric end of the stomach to the large intestine. The small intestine is divided into several anatomically recognisable areas: the duodenum; the proximal section, which is the widest section and is about 20 cm long and curved; the jejunum, which is the middle section and is about 2.5 m long; and the ileum, which is the distal section and is about 4 m in length.

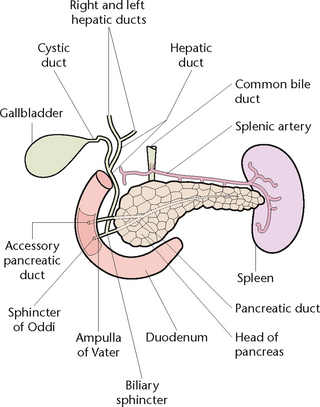

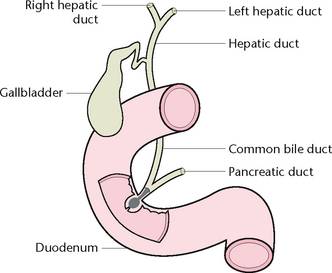

Intestinal glands in the mucous membrane secrete an intestinal juice containing enzymes to complete the digestion of food. An opening in the duodenum (ampulla of Vater) allows for the entry of the common bile duct, carrying bile from the liver, and the pancreatic duct, carrying pancreatic juice. At the junction of the ileum and the caecum of the large intestine is the ileocaecal valve, which prevents a backward flow of contents from the large to the small intestine.

The functions of the small intestine are the secretion of intestinal juice, completion of chemical digestion of food and absorption of digested food.

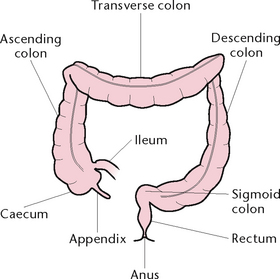

The large intestine

The large intestine is a muscular tube about 1.5 m in length and 6 cm in diameter, which extends from the end of the ileum to the anus (Fig 30.4). Lying in the abdominal and pelvic cavities, the large intestine may be divided into regions that are distinguished by their anatomical structure and position:

• The caecum, a blind-ended sac about 6 cm long and 7.5 cm in diameter, leads into the ascending colon and has the appendix attached. Studies suggest that the appendix is part of the immune system within the body (Duke University Medical Center 2007)

• The ascending colon, which is about 15 cm long and passes up the right side of the abdominal cavity to the lower surface of the liver

• The transverse colon, which is about 50 cm long and crosses the upper abdomen from right to left then curves in the vicinity of the spleen

• The descending colon, which is about 25 cm long and passes down the left side of the abdomen to the left iliac region

• The sigmoid colon, which is variable in length and is the S-shaped continuation of the descending colon and lies in the pelvic cavity

• The rectum, a straight tube about 12 cm long that forms the last section of the large intestine

• The anal canal, the terminal part of the rectum, about 4 cm in length. The canal opens on to the external skin at the anus. The anal canal contains the internal and the external anal sphincters. The sphincters seal off the end of the alimentary canal and are normally constricted.

The four functions of the large intestine are:

1. The absorption of large amounts of water and some mineral salts

2. Production of microorganisms (mainly bacteria) that are necessary for the normal functioning of lymphatic tissue in the large intestine and thus resistance to infection. These bacteria also synthesise vitamins B and K. The gut contains a mixture of organisms in health referred to as the normal flora

3. Transformation of the intestinal contents into semi-solid faeces, and storage of faeces until they are excreted

The accessory digestive organs

The accessory organs secrete enzymes into the GI tract, secretions (enzymes) that are actively involved in the process of digestion. An enzyme is a substance, usually protein in nature, that initiates and accelerates a chemical reaction. The accessory organs are the salivary glands, the pancreas, the liver and the biliary tract.

The salivary glands

There are three pairs of salivary glands that secrete saliva into the mouth. Saliva is a watery fluid containing ions, mucin and the digestive enzyme salivary amylase. Salivation is largely initiated by sensory stimulation, including the presence of food in the mouth, and by taste and smell. Salivation may also be induced by the presence of irritating substances in the stomach or small intestine. Saliva has the following functions:

The pancreas

The pancreas is a soft gland, lying across the abdominal cavity behind the stomach. It is divided into a head, which fits into the curve of the duodenum; a central portion, or body; and a tail, which extends out to the spleen. The pancreatic duct runs centrally through the length of the pancreas, while smaller ducts carry the pancreatic juice secreted by the pancreas into the central duct. The pancreatic duct joins the common bile duct from the liver, to enter the duodenum (Fig 30.5).

The bulk of the tissue in the pancreas is composed of exocrine cells, which produce pancreatic juice. The pancreas secretes about 1200 mL of pancreatic juice daily. The overall function of pancreatic juice is the digestion of nutrients. Scattered among the exocrine tissue are groups of hormone-secreting cells, the islets of Langerhans, which contain four distinct cells of which the beta cells are crucial to the production of insulin.

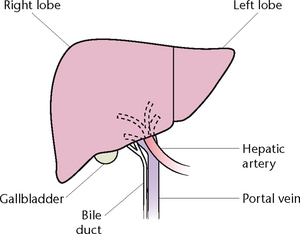

The liver

The liver is an organ situated in the upper part of the abdominal cavity, immediately beneath the diaphragm. The greater part of the liver lies in the right upper abdomen but the organ extends across to the left upper abdomen (Fig 30.6). The liver is divided into two parts, a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe.

The liver converts any glucose not needed immediately into glycogen for storage. It converts excess protein to glucose to be used as an energy source, and changes the nitrogenous part of excess protein to urea, which is excreted. The liver also converts fats into a form that can be used by the tissues and manufactures bile to aid digestion.

The biliary tract, which transports bile from the liver to the duodenum, consists of the left and right hepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct, the cystic duct, the gallbladder and the common bile duct (Fig 30.7).

The gallbladder

The gallbladder is a small muscular sac that lies on the inferior surface beneath the right lobe of the liver.

Functions of the liver and gallbladder include:

• Secretion of bile, a watery fluid containing a variety of organic and inorganic substances, but no enzymes. As much as 1 L of bile may be secreted by the liver per day, and stored in the gallbladder before its release into the duodenum. Bile contains bile salts and bile pigments which emulsify fats in preparation for the action of enzymes

• Stimulates peristalsis in the intestine

• Colours and deodorises faeces

• Helps in the absorption of fats and vitamin K from the small intestine.

Bile not needed immediately travels from the common hepatic duct into the cystic duct and passes into the gallbladder for storage.

Physiology of digestion

During the process of digestion, food is reduced to its simplest chemical form so that it can be absorbed into the bloodstream and used by the tissues. Digestion occurs through both mechanical and chemical actions. Mechanical action involves the physical process of liquefying the food, mixing it with digestive juices and moving it through the GI tract. Chemical action occurs when the digestive juices mix with the food, resulting in complex chemical substances being split into simple substances. Digestion begins in the mouth, the action of chewing softening the food and the presence of food in the mouth, together with its taste and smell, stimulates the secretion of saliva, gastric and pancreatic juices and bile.

Digestion in the stomach

The stomach stores the food and later releases it at a rate that is optimal for digestion. Food is mixed with gastric juice, thereby changing its consistency so that it will be more easily transported along the alimentary canal. When the stomach muscles are stretched by swallowed food, peristaltic contractions are stimulated, which results in a churning movement. When the food is mixed with gastric juice it develops a pasty consistency and becomes known as chyme. The rate of emptying of the stomach depends on the:

• Degree of opening of the pyloric orifice

• Force of the peristaltic contractions

• Type of food in the stomach (fats tend to delay emptying, while carbohydrates are usually emptied quickly).

The average time for the stomach to empty after a meal is 4–6 hours. The gastrocolic reflex is a physiological reflex controlling peristalsis; it involves an increase in motility of the colon in response to fullness in the stomach and digestion in the small intestine. This reflex is responsible for the urge to defecate following a meal.

Digestion in the small intestine

After it leaves the stomach, chyme is mixed with intestinal secretions as well as with bile and pancreatic juice. Digestion is completed and the products are absorbed through the villi of the intestinal wall. The wall of the small intestine is capable of several different types of movement:

• Peristalsis, which ensures an onward movement of the contents of the intestine

• Segmentation, which ensures mixing of the intestinal contents. Segmentation contractions occur regularly, causing the chyme to be broken up into segments. Chyme enters the caecum through the ileocaecal valve, which is normally closed but opens briefly to allow a small amount of chyme through with each peristaltic wave.

Digestion in the large intestine

The formation of faeces begins in the large intestine. Though absorption of water takes place in the large intestine, water still remains and makes up 60–70% of the weight of faeces. The forming faeces also contain fibre, indigestible cellular plant and animal matter, dead and live microbes, digestive enzymes, epithelial cells from the walls of the gastrointestinal tract together with the mucus they secrete, fatty acids and bile pigments. Faeces also contain dead cells shed from the intestinal lining as well as waste products like bile pigments and toxic substances.

Faecal matter and defecation

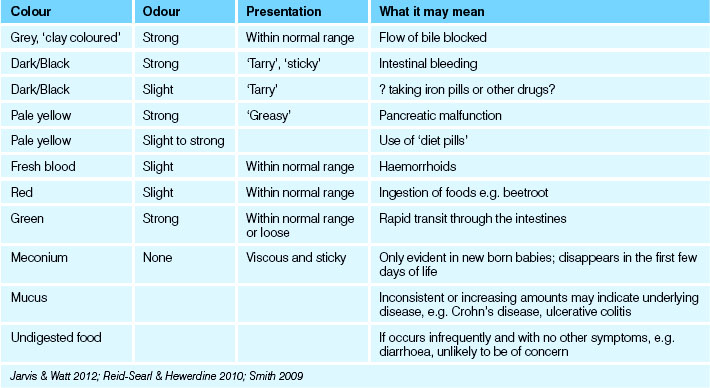

Faecal matter varies significantly in appearance, depending on diet and health. It is usually brown in colour which results from a combination of bile and bilirubin.

Most of the time the rectum is empty of faeces; however, when a mass movement forces faeces into the rectum the desire to defecate is initiated. Faeces collect in the sigmoid colon before entering the rectum. As the faecal mass enters the rectum the defecation reflex and the desire to defecate are initiated. If it is not convenient, defecation can be delayed temporarily, as within a few seconds the reflex contractions cease and the rectal walls relax (Berman et al 2012; Marieb & Hoehn 2010; McCance & Huether 2010).

Meeting elimination needs

The client’s elimination status is assessed by obtaining information about elimination practices and bowel actions. The nurse should enquire about the client’s usual pattern of defecation and whether they have experienced any recent alterations to this pattern (see Clinical Interest Box 30.1). Information should also be obtained about the client’s usual fluid and dietary intake so that, whenever possible, it can be maintained or improved to facilitate normal elimination. The nurse should identify early signs of any problems associated with elimination so that appropriate care can be implemented to assist the client to meet their elimination needs. The nurse should also be aware of the numerous factors that affect bowel elimination:

• Age: developmental changes affect bowel elimination throughout life. As the body develops and changes, so do the size of the small and large intestines, amount of secretions and rate of peristalsis. Infants have developing digestive tracts, so complex foods are poorly digested, peristalsis is rapid and control of the bowel is not coordinated by the neuromuscular system until 2–3 years of age. During adolescence, the rate of gastric secretions increase and as ageing increases the rate of peristalsis is reduced. The slowing of nerve impulses delays the sensation to defecate and can lead to constipation

• Cultural influences: the use of different toilet equipment, where and when defecation is deemed to be appropriate, as well as dietary input all impact on the client’s ability to maintain their usual elimination pattern. Changes to environment plus the challenges and/or anxieties associated with assimilating into a new or different culture may similarly alter the elimination patterns. Adherence to fasting practices will also affect elimination patterns

• Privacy: ensuring adequate privacy and sufficient time for the client to pass faeces. If possible, the client should be left alone to use the toilet aids (e.g. commode, bedpan or urinal) as they are generally self-conscious about the need to eliminate in the presence of others. Ensure the client’s safety and that the call bell is accessible

• Position: any interference from the usual body position (e.g. due to surgery or changed environment) can lead to difficulty defecating. Children, older people or those with a disability may require special needs

• Routine: changes to normal routine can cause an interruption to the client’s normal gastrocolic reflex

• Diet and fluid intake: any changes to diet will affect elimination. An inadequate fluid intake can result in hardening of the stool contents and discomfort when defecation occurs. The recommended fluid intake for adults is 1400–2000 mL/day. This may be contraindicated in clients with cardiac and renal disorders

• Physical activity: physical activity promotes peristalsis, while inactivity reduces motility of the bowel. It is recommended that all individuals perform regular mild exercise to promote regular bowel elimination

• Infection: the infection process can directly affect the protective lining of the gastrointestinal tract

• Pain: pain on defecation may be due to the presence of lesions such as haemorrhoids or anal fissures. Tenesmus is the term used to describe persistent ineffectual spasms of the rectum accompanied by the desire to empty the bowel; it may be associated with disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease

• Psychological state: the psychological state of a person influences the motility and secretions of the gastrointestinal tract. If a person is angry, anxious or stressed, the secretions and motility of the bowel are increased and can lead to diarrhoea. Alternatively, a person who is depressed will have reduced secretions and motility of the bowel, which could lead to constipation

• Pregnancy: as the fetus develops in size through pregnancy, the pressure it exerts on the bowel is increased, impeding the movement of faecal matter through the bowel

• Medication: laxatives are used to soften the stool to ease the discomfort in defecating. Excessive or chronic use of laxatives leads to reduced bowel muscle tone and less responsiveness to the normal stimulation of defecation. There are also numerous medications which affect the bowel and careful scrutiny of drug regimens is required

• Surgery and anaesthetics: anaesthetics stop bowel peristalsis. Direct and prolonged surgery and nerve damage to the bowel can lead to a prolonged period of reduced peristalsis.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 30.1 Clinical consideration when assessing bowel patterns

Some clients may be embarrassed when nurses ask them about their bowel functioning. Therefore it is important to ensure that questioning is conducted in an appropriate way, place and time. Nurses should adapt their use of terminology to the client they are dealing with. For example, the nurse may ask a child ‘Have you had a poo today?’ instead of ‘Have you used your bowels today?’

Promoting a healthy bowel elimination program

A program to promote bowel elimination is an important part of the nursing care plan for a client. The goal of a bowel management program is to assist the client to evacuate the bowel comfortably and completely at a determined time without laxative support, by promoting privacy, regular mild exercise, high-fibre foods and an adequate fluid intake. The client’s overall lifestyle becomes healthier, and general wellness and outlook improve (see Clinical Interest Box 30.2).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 30.2 Nursing assessment relating to bowel problems

Diet

The role of diet is pivotal for a functioning digestive system and the individual’s overall health. While a high fibre diet is indicated with constipation, a low fibre diet is required in the presence of diarrhoea. Specialised diets are often required such as gluten- or diary-free diets and the potential for poor nutritional intake is increased if bloating, pain or nausea is present. Adequate fluid is also required, particularly in the presence of certain drugs, but fluids known to increase constipation such as alcohol and coffee should be used judiciously. Diet is complex, due to not only the disease process but also as a result of cultural norms, the individual’s age and the normal likes and dislikes we all experience. While it is difficult to meet all individuals’ needs, an effort to ensure adequate nutrition is of paramount importance for health and wellbeing (LeMone et al 2011).

Monitoring elimination

Daily bowel charts recording the bowel movement within a 24-hour period and analysis of a pattern over a week or month will demonstrate any changes. Use of a bowel diary which adds further information such as fluid and diet as well as activities and changes to lifestyle will allow the individual to identify issues which may impact on their elimination changes or habits (Brown 2007).

Examining faeces

To detect and identify abnormalities, faeces are examined by observation (see Table 30.1 and the Bristol Stool Chart (The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne nd)), by chemical testing in the workplace or by analysis in the laboratory. Laboratory analysis of faeces provides information about the condition and functioning of the digestive system. Testing the faeces for abnormalities involves analysing the specimen for the presence of blood, parasites and/or their ova, bile, fat, pathogenic microorganisms or pancreatic enzymes (Lewis & Heaton 1997).

Environment

Evacuation is for most adults an intensely private function, preferably done away from people listening. Infants of every culture instinctively adopt a squatting position to evacuate faeces and this was the manner for centuries for most peoples and is still the preferred method in many parts of the world. The invention of indoor plumbing altered this for the much of the developed world, and the porcelain toilet is now considered the norm in most places in Australia and New Zealand. The individual’s sitting position on the toilet may need investigation to optimise a relaxed and natural posture to aid elimination.

Common problems associated with elimination of faeces

Constipation

Constipation is the infrequent passage of dry hard stools and is often the result of some deficiency in the three elements necessary for normal bowel activity: dietary fibre, adequate fluid input and sufficient physical activity. It can occur any time during the life span but commonly during pregnancy and childbirth, the second half of a menstrual cycle, in those clients suffering eating disorders, following an operation and in those clients suffering depression and/or dementia (Foxley & Vosloo 2008). Anatomical problems include rectocele, haemorrhoids, Hirshsprung’s disease, spinal injury and endocrine and neurological disorders (Foxley & Vosloo 2008). When constipation occurs, the individual often strains to produce hard dry stools, and straining may aggravate preexisting rectal conditions such as haemorrhoids. Constipation is often accompanied by abdominal distension and discomfort, nausea, headache and diminished appetite. Natural measures to prevent constipation include:

• Sufficient dietary fibre: foods such as wholegrain cereals, fruit and vegetables contribute bulk and induce peristalsis

• Adequate fluid input: at least 1500 mL/day is necessary to help keep the intestinal contents in a semi-solid state for easy passage and excretion

• Responding to the desire to empty the bowel as soon as practicable

• Maintaining a regular time for bowel movement

• Maintaining regular exercise

• Relaxing and assuming a natural position when having a bowel action. Some people find the use of a small footstool to promote thigh flexion helpful

• Avoiding undue anxiety about bowel habits. While some people have a bowel action every day, it is quite normal for others to have a 2- to 3-day interval between bowel actions

Other measures to assist elimination from the bowel may be necessary, including:

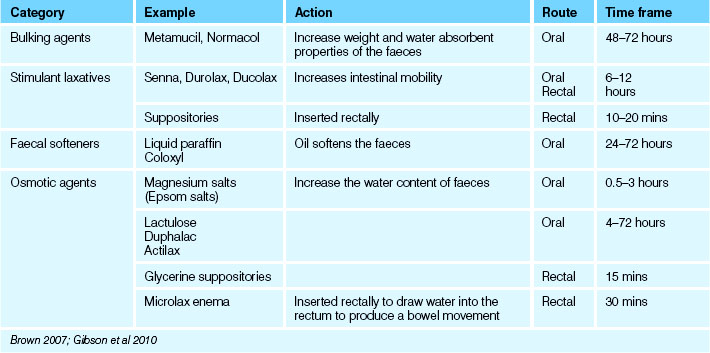

• Laxatives: substances taken orally that promote evacuation of the bowel by increasing bulk, softening the faeces or lubricating the walls of the colon (see Table 30.2)

• Suppositories: small solid masses medically ordered and inserted into the rectum to promote the evacuation of faeces

• Enemas: the introduction of fluid through the anus into the lower colon to promote the evacuation of faeces.

Clinical Scenario Box 30.1

Joan, 86, is admitted with severe constipation. While you are interviewing Joan she states that she has managed her constipation in the past with laxatives, and that she restricts her fluid intake because she suffers with urinary incontinence. She has not been as mobile since her right knee replacement 1 month ago.

Impaction

Impaction occurs when the faeces remain in the rectum for a long time and a large hardened mass develops that is difficult and often painful to expel; the term impacted is used to describe this condition. It can cause confusion on initial investigation as faecal overflow may occur around the obstruction, which can be assessed by abdominal percussion and/or rectal examination. Often faecal incontinence coexists with urinary incontinence.

Flatulence

Excessive formation of gas in the stomach and intestines is called flatulence. If the gas is not expelled, the intestines become distended and the person may experience abdominal discomfort and swelling. Flatus is the term used for gas in the intestine that is expelled through the anus. Flatulence may result from swallowed air, the consumption of gas-forming food or liquid or bacterial action within the intestines.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is the discharge of frequent, loose unformed stools resulting from the rapid passage of contents through the intestines. The person with diarrhoea may be exhausted from frequent defecation and the presence of accompanying abdominal distension and pain. If diarrhoea is prolonged, the absorption of nutrients and fluids is impaired and the person begins to show signs of fluid and electrolyte loss. Diarrhoea is a symptom of various conditions, including:

• Irritation or inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract; for example, due to pathogenic infection, highly spiced foods or medications that increase intestinal motility

• Disorders of digestion or absorption

• Disorders that affect secretion and function of bile or pancreatic juice, such as in obstructive jaundice

Diarrhoea should be assessed in terms of the frequency of defecation and the characteristics of the faeces. The cause of diarrhoea must be investigated and treated. Key aspects related to the care of a client with diarrhoea include:

• Reducing intestinal peristalsis: dietary management of an adult client involves the withholding of food until the diarrhoea diminishes, then the gradual resumption of food. Foods low in fibre may be provided initially to reduce stimulation of the intestines

• Administering any prescribed medications: antidiarrhoeal medications may be prescribed, as may antispasmodic preparations, to reduce abdominal cramps and pains

• Maintaining fluid input to replace lost fluids and to prevent dehydration. Oral fluids are given if tolerated, or fluids may be administered intravenously. Input and output should be observed and documented as part of the client’s fluid balance assessment

• Ensuring that the client has adequate privacy whenever toilet facilities are being used, and that used toilet utensils are removed from the room immediately

• Ensuring that the client’s hygiene needs are met: after each bowel action the anal area and buttocks should be cleansed with a mild soap and thoroughly dried. A protective cream may be applied to reduce discomfort, and the area should be observed for signs of excoriation

• When using a bedpan or commode chair, the client may be embarrassed by the odours associated with diarrhoea, so measures to eliminate odours should be taken. Any soiled linen should be changed and removed from the room immediately. The room should be well ventilated, and room deodorants may be used with discretion

• Implementing isolation precautions should be considered until diagnosis of the cause, e.g. pathogenic infection, to prevent cross-infection.

Faecal incontinence

Faecal incontinence (encopresis) is the inability to control the excretion of faeces, and may occur in pregnancy, cardiac illness, congenital anorectal malformation, as a result of rectal surgery, brain or spinal cord injury, impaired consciousness or awareness or various other factors. Management includes continence pads, lifestyle modification, anal plugs, pelvic floor training and drug therapy. Surgical intervention is an option in some cases (Sharpe & Read 2010). The cause must be identified and treated, the person’s hygiene needs attended to, as well as measures taken to maintain dignity and self-esteem. Recent studies suggest one in five women in Australia has experienced faecal incontinence (Boldero et al 2011).

Artificial openings into the intestine

As a result of certain disorders such as obstruction or tumours in the bowel, the passage of faeces through the rectum and anus may not be possible. In these instances, the surgical creation of an artificial opening from the colon to the surface of the abdomen may become necessary. For the latest information and research findings on this subject, see the Australian Council of Stoma Associations website: www.australianstoma.org.au

Nursing interventions

Clients with bowel elimination disorders may require various forms of nursing intervention:

• Standard precautions when dealing with body fluids

• Accurate documentation and assessment of bowel habits

• Support of privacy, cultural and/or personal customs as well as emotional and dignity issues

• Ensuring environment is clean, fresh and appropriate to age and ability of the client

• Use of air fresheners and care of intimate hygiene and skin integrity

• Disposable pads or specific items to deal with overflow or leakage

• Enabling individuals through education and environmental and emotional support to effectively evacuate their bowels.

Suppositories

Suppositories may be ordered and inserted into the rectum to promote the evacuation of faeces or to facilitate rectal administration of a drug (see Procedural Guideline 30.1). The required equipment consists of:

• Prescribed suppository/suppositories

• Receptacle for used articles

Procedural Guideline 30.1 Inserting a rectal suppository

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Explain the procedure | Reduces anxiety |

| Assemble the equipment and follow the nursing policies related to checking medications | The correct type, size and quantity must be administered |

| Ensure adequate privacy | Reduces embarrassment |

| Place the individual in a left lateral position | Anatomical site of the lower colon: this position is the most effective for the introduction and retention of suppositories |

| Ensure that the person is adequately covered, with only the buttocks exposed | Promotes warmth, comfort and dignity |

| Perform hand hygiene and put on disposable gloves | Prevents cross-infection |

| Lubricate finger of glove and suppository | Facilitates insertion of suppository |

| Gently insert the suppository by directing it with the finger, through the anus about 3.5 cm into the rectum | Suppository must pass the internal anal sphincter and come in contact with rectal mucosa |

| During insertion, encourage the client to take deep breaths through the mouth | Helps relax the anal sphincters |

| Encourage the client to retain the suppository for the correct length of time. A suppository administered to cause a bowel action should (usually) be retained for at least 20 minutes | Client must be aware of whether the suppository is to be retained to allow any medication to be dissipated, or whether to expect a bowel action. Suppositories to promote a bowel action must be retained long enough to be effective |

| Reduces anxiety related to accidental expulsion of the suppository or faeces | |

| Dispose of used equipment appropriately; perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| If a bowel action results, the faeces are observed and the observations reported and documented | Helps in assessing the effectiveness of the treatment and detects any abnormalities |

| Attend to the client’s hygiene and skin integrity | Helps promote comfort |

| Report and document the procedure | Appropriate care may be planned and implemented |

Suppositories prescribed to promote a bowel action are composed of various substances, such as glycerine. Evacuant suppositories act by softening and lubricating the faeces to facilitate easy passage and excretion, or by increasing peristalsis through the irritation of intestinal sensory nerve endings. The nurse must be aware of the different types of suppositories available and work within the scope of practice regarding the checking and administration of drugs. Types of medications that may be administered rectally by suppository include those that relieve nausea, relieve bronchospasm during an asthma attack or provide anti-inflammatory action to minimise gastric irritation.

Enemas

To give an enema is to introduce a solution into the rectum and sigmoid colon (see Procedural Guideline 30.2). Most commonly it is ordered and administered to promote the evacuation of faeces and alleviate constipation, to administer a drug rectally, to prepare a bowel for diagnostic procedures or surgery or to begin a bowel training program.

Procedural Guideline 30.2 Administering a disposable enema

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Check the medical offcer’s order. Explain the enema procedure to the client; follow the nursing policies related to checking medications | Ensures that a medical order has been written. Informs the client |

| Collect all equipment: disposable enema, bed pan, bedside commode, underpad/bluey, water soluble lubricant, disposable gloves, paper towel and toilet tissue. Ensure that there is a bedpan or bedside commode by the bed or appropriate resources in place to collect expelled faeces. | Facilitates access during procedure |

| If possible, place the client onto left side and drape with a blanket or sheet. Place the underpad/bluey under the buttocks. Ensure privacy and dignity | Solution travels up the colon more easily when the client is lying on the left side. The underpad/bluey protects the bed clothes from moisture or soiling |

| Perform hand hygiene and put on disposable gloves | Prevents cross-infection |

| Apply lubricant to the tip of the disposable enema. Gently insert the tip into the anal opening, about 10 cm in an adult. Gently squeeze the container and roll it up from the bottom as the contents enter the bowel. Squeeze as much of the fluid into the rectum as possible. Remove the tip slowly and hold the buttocks together | Slow instillation of an enema achieves the best result. The client should retain the solution for about 20 minutes to 2 hours so that it will soften the stool |

| Assist the client onto the bed pan or bedside commode. If the client uses the toilet, request to see the result before fushing. If a bed pan is used, raise the head of the bed to a sitting position, if this is not contraindicated. Place call bell and toilet paper within reach | Provides an opportunity to observe the characteristics of the stool expelled |

| When the bowel contents have been expelled, assist the client in cleaning the anal area, observe the results of the enema, noting the colour, amount and consistency of the stool. Remove and clean the bed pan or bedside commode. Perform hand hygiene | Results of the enema are judged by the stool expelled |

| Restore the client’s area, lower the bed, replace the side rails (if being used) and place the call bell within reach | Provides safety |

| Document the date, time, type of enema and amount of fluid instilled. Describe the result and how the client tolerated the procedure | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

Treating impacted faeces

The term faecal impaction refers to the presence of a large, hard dry mass of faeces in the lower colon. When the condition occurs it is a result of prolonged constipation, poor bowel habits, inactivity, dehydration, use of constipation-inducing drugs or incomplete bowel cleansing after a barium swallow or enema. If measures to promote a bowel action, such as a suppository or enema, are ineffectual, surgical removal of the mass may be prescribed. If medically approved, encourage fluids and exercise once evacuation is complete and the client is rested (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Jarvis & Watt 2012).

DISORDERS OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Specific disorders

Any changes to the nutritional status of the client will impact on their elimination process and may be ongoing, depending on the nature of the disease process. There are many and varied disorders of the alimentary tract but the following are some of the disorders commonly encountered in practice.

Stomatitis

Stomatitis is a term that refers to inflammation of the mouth. It may be a primary condition or a symptom of another disease. Inflammation may affect the lips, tongue, gums, mucous membranes or palate. Stomatitis is characterised by pain, bleeding, swelling, ulceration and halitosis and can often be managed with good oral hygiene and by treating the underlying disorders that are contributing to the condition, such as vitamin deficiencies.

Parotitis

Parotitis is inflammation of the parotid glands, which may also be related to poor oral hygiene, dryness of the mouth or infection. Infectious parotitis (mumps) is an acute viral disease. Parotitis may also result from a calculus in the parotid gland.

Dry mouth

Dry mouth can result from dehydration, medical conditions such as diabetes and stroke and is a common side effect of many drugs including antihistamines, diuretics and sedatives. The condition can be associated with thrush, a condition caused by the Candida fungus, and which is a common complaint in children and older clients.

Sialorrhoea

Sialorrhoea is a condition manifested by the secretion of drool in the resting state. Excessive saliva occasionally occurs in pregnancy, may be present following a stroke or can be experienced by those clients suffering Parkinson’s disease. Infectious conditions and neoplasm can also cause the condition and treatment is dependent on the underlying cause.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) occurs when gastric acid refluxes back into the oesophagus. Symptoms include persistent heartburn and acid regurgitation, dry cough, halitosis and nausea. In severe cases the symptoms include weight loss and severe chest pain. A hiatus (diaphragmatic) hernia, the herniation of the stomach through the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity, may be one cause of GORD. Changes to diet and lifestyle may aid the client; certain prescription medication, changes to diet and in some cases surgical intervention may be required (Selby 2010).

Gastritis

Gastritis is inflammation of the gastric mucosa and may be acute or chronic. Acute gastritis is associated with irritation of the mucosa related to the ingestion of irritating foods, alcohol, caffeine or certain medications. Acute gastritis may also be caused by food poisoning, microorganisms or psychological stress. Chronic gastritis is commonly associated with an underlying disorder such as gastric ulcer, chronic alcohol abuse or malignancy. Many people with chronic gastritis have no symptoms, while others experience anorexia, a feeling of fullness, eructation (burping) and vague epigastric pain. The same symptoms appear in acute gastritis, and the individual may also experience abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Haemorrhage may occur, presenting as haematemesis (vomited blood), and/or occult blood in the faeces or melaena. A common cause of gastric ulcers is the infection caused by Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Investigations for H. pylori include breath tests, as well as blood and stool tests (Edwards 2008).

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is inflammation of the stomach and intestines. It is an acute disorder characterised by diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal cramps. Gastroenteritis has many causes, including the ingestion of bacteria, amoebae, parasites, viruses, toxins or food allergens; and drug reactions. The symptoms vary according to the cause, the extent to which the digestive tract is involved and the age of the individual. Infants, older adults and debilitated clients are more vulnerable to the rapid loss of fluid and electrolytes that occurs with the condition.

Haemorrhage

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage may occur as a result of a variety of disorders. Common causes of bleeding from the upper digestive tract are peptic ulcer disease, oesophageal varices, malignancy and erosive gastritis. Causes of bleeding from the lower digestive tract include haemorrhoids, fissures, inflammatory bowel disease, polyps, diverticular disease and malignancy. Gastrointestinal bleeding is sometimes associated with disorders of the blood, such as leukaemia. Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage may be accompanied by haematemesis, melaena or occult blood in the faeces. Haemorrhage from the lower intestinal tract may present as bright-red blood excreted through the anus, or as occult blood present in the faeces. If blood loss is severe, the signs and symptoms of hypovolaemic shock will be evident.

Peptic ulcer

A peptic ulcer is a localised area of erosion occurring in the stomach or duodenal (the beginning of the small intestine) lining. The most common cause of peptic ulcer is a stomach infection associated with the H. pylori bacteria but a small percentage are caused by anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Malignancy may also be a cause of perforation into the lining of the stomach or duodenum. Symptoms vary in each client but may include nausea, vomiting, haematemesis, epigastric pain, loss of appetite and weight loss (Edwards 2008).

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the gallbladder and is commonly associated with impaction of a gallstone in the cystic duct. The gallbladder becomes dilated and filled with bile, pus and blood. Cholelithiasis is the term used to describe the presence of stones or calculi in the gallbladder. Choledocholithiasis is the presence of gallstones in the common bile duct. Major manifestations of cholecystitis are intense pain and tenderness in the right upper abdominal quadrant, nausea and vomiting. If a stone obstructs the common bile duct, jaundice may be evident. Women are more prone to developing gallstones due to hormonal changes in pregnancy and often present with symptoms in the middle and later years (Kuhn 2011).

Hepatitis

Hepatitis, which is inflammation of the liver, may be viral or non-viral in origin. Viral hepatitis is classified as infection with hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis D (HDV) or hepatitis E (HEV).

Hepatitis B, C and D usually occur as a result of parenteral contact with infected body fluids and hepatitis A and E are typically caused by ingestion of contaminated food or water (World Health Organization (WHO) 2011). Healthcare workers are at risk and standard precautions must be scrupulously adhered to at all times.

Hepatitis A is a viral infection of the liver generally spread via the faecal–oral route. The individual may have few symptoms or may experience headaches, fatigue, anorexia, pyrexia, dark urine, pale faeces, liver enlargement, jaundice and pruritus. The course of the infection is usually short term and a vaccination against hepatitis A is available.

Hepatitis B (serum hepatitis) is generally transmitted parentally by contact with infected blood. The virus may also be spread via contact with body secretions such as saliva, vaginal secretions, menstrual blood and semen and from infected mother to her baby, during passage through the birth canal or via breast milk. The incidence of hepatitis B is higher in people who receive blood or blood products, use or share contaminated needles or engage in unprotected sexual practices. The infection may persist for a long time, resulting in chronic liver failure and cirrhosis but the majority of people with hepatitis B will recover. Adult vaccination against hepatitis B involves three doses given over 6 months.

Hepatitis C is a virus that causes liver inflammation and liver disease. It is spread through blood-to-blood contact such as blood transfusions, shared needle, application of tattoos etc. There is no vaccination currently available for hepatitis C (WHO 2011).

Hepatitis D is most commonly seen in developing countries and is caused through a defective virus that needs the hepatitis B virus to exist. Vaccination against HBV is usually effective (WHO 2011).

Hepatitis E is a viral disease more common in developing countries. The highest rates of hepatitis E infection occur in regions where there is poor sanitation and sewage management that promotes the transmission of the virus. For example, hepatitis E is common in Central and South-east Asia, North and West Africa and Mexico. In most cases it will resolve (Hepatitis Australia 2010).

Non-viral hepatitis generally results from exposure to certain toxins and medication and excessive use of alcohol. Manifestations of the disorder are similar to those of viral hepatitis.

Diverticular disease

Diverticular disease (diverticulosis) is the presence of bulging pouches (diverticula) in the intestinal mucosa and can occur anywhere along the intestinal tract except the rectum; however, the diverticula are most common in the sigmoid colon. Faecal matter becomes trapped in the pouches and the resulting inflammation is called diverticulitis. Diverticulitis causes mild to severe abdominal pain, some nausea and altered bowel habits. In severe cases, the diverticula can rupture, producing abscesses or peritonitis. It increases in incidence with ageing and there is no gender bias in presentation but cultural factors are thought to impact on the disease process as a result of the highly refined diet found in the developed world (LeMone et al 2011).

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) manifests with bowel dysfunction, often accompanied by abdominal pain and bloating (Woods et al 2008). The condition is thought to result from food intolerance, psychological distress or in the presence of increased gastrin levels and affects more women in the developed world than men. Treatment may involve the use of antispasmodics, antidepressants, lifestyle coaching, an increased intake of probiotics and altered dietary intake (Heitkemper & Jarrett 2008).

Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is an abnormal response by the immune system to gluten, causing small bowel damage. Symptoms include diarrhoea and malabsorption which prevents uptake of essential nutrients. Treatment requires a continuing gluten-free diet to resolve the symptoms (LeMone et al 2011).

Hernia

A hernia is the protrusion of an organ or the fascia of an organ through the wall of the cavity that normally contains it. Various types of hernias are named according to their location: umbilical, inguinal, femoral, intestinal and incisional; the last occurs at the site of an abdominal incision. The major complication of an intestinal hernia is strangulation, when the blood flow to the protruding loop of bowel may be so obstructed that necrosis occurs.

Bowel obstruction

Bowel obstruction is a mechanical or functional obstruction of the intestines, preventing the normal digestion process. Obstructions include tumours, chronic diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease and, as recently reported, complications of enteral feeding through a jejunostomy tube (De Brabandere et al 2010). If the obstruction is at the distal end of the intestine, vomiting may occur, and the vomitus has a faecal odour caused by bacterial overgrowth in the intestinal tract. The individual generally experiences abdominal pain, distension and vomiting, and is usually unable to pass flatus or faeces. Further manifestations of bowel obstruction may include fluid and electrolyte imbalance because of progressive dehydration and plasma loss. Complications of intestinal obstruction include peritonitis, ischaemia and necrosis of the bowel.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are distended veins in the anal area, and can be internal or external. Internal haemorrhoids commonly present with prolapse or painless rectal bleeding. External haemorrhoids cause bleeding and can cause acute pain if thrombosed. Haemorrhoids commonly result from increased pressure in the anal area related to constipation, straining to defecate, obesity, pregnancy and prolonged sitting or standing. The individual commonly experiences pain in, and bleeding from, the anus, particularly during defecation. Pruritus of the anal area may occur in the presence of external haemorrhoids and topical creams are available to alleviate this symptom. Surgery may be an option in severe cases (Mounsey et al 2011).

Anal fissure

An anal fissure is a crack in the lining of the anus and, like haemorrhoids, is associated with increased pressure in the anal area. Sudden occurrence is characterised by a tearing or burning pain during or immediately after defecation, and by the appearance of a few drops of blood. An anal fissure may heal spontaneously or it may partially heal and recur. A chronic fissure produces scar tissue, which may impede normal defecation (LeMone et al 2011).

Rectal prolapse

Rectal prolapse is the protrusion of one or more layers of the mucous membrane of the rectum through the anus. Prolapse may be partial, or complete—with displacement of the anal sphincter and rectum. Rectal prolapse is associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure from straining to defecate or malignancy, for example. It may also result from weak rectal sphincters or muscles. Protrusion of tissue from the rectum is evident, and the individual may experience a sensation of rectal fullness, bleeding and pain due to ulceration of the exposed tissues (Jarvis & Watt 2012).

Inflammatory and infectious disorders

Inflammatory and/or infectious disorders of the digestive system may be related to internal or external irritation or to the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is the acute inflammation of the vermiform appendix. The client typically presents with acute abdominal pain starting in the mid-abdomen, later localising to the right lower quadrant. Symptoms may include fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and elevation of the neutrophil count. The condition commonly results from an obstruction of the lumen of the appendix, for example, by a faecal mass, or as a result of inflammation and oedema due to a viral infection. The obstruction causes inflammation, which can lead to infection, necrosis and perforation. If the appendix perforates, the contents spill into the abdominal cavity, causing peritonitis (BMJ Best Practice 2011).

Peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the peritoneum and may be associated with many conditions. Causes of peritonitis include end-stage liver disease, ruptured appendix and abdominal trauma. It may be associated with the replacement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes (Taheri et al 2011). The peritoneum becomes inflamed and oedematous, which generally results in decreased intestinal motility and intestinal obstruction. The onset of peritonitis may be acute, or slow and progressive. The inflammatory process causes accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity, leading to abdominal distension and rigidity, severe pain, nausea and vomiting. As a result of loss of fluid and electrolytes into the abdominal cavity, the individual displays signs of hypovolaemic shock. Abdominal distension can result in upward displacement of the diaphragm and, typically, the individual’s ventilations become shallow.

Pilonidal sinus

Pilonidal sinus is a chronic discharging sinus or an acute abscess occurring in the sacrococcygeal area; it causes pain and infective symptoms and often requires a surgical incision with drainage. The condition is exacerbated by friction, warmth and moisture. Nursing care includes keeping the area dry and clean and ensuring the client routinely removes hair from the area (LeMone et al 2011).

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease is the term generally used to describe ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, both of which are chronic and recurrent disorders. Although the precise cause of inflammatory bowel disease is unknown, factors that have been implicated include a familial tendency, infection, autoimmune reactions and psychological stress. The effect of the disease causes altered mobility and fatigue, as well as changes to perception of body image and alteration in quality of life (Woods et al 2008). Recent work in this area discusses the relationship between the disease profile and the client’s perfectionist personality. As a result, cognitive behavioural therapy is increasingly used in the treatment modalities (Flett et al 2011).

Ulcerative colitis primarily affects the superficial mucosal layers of large areas of the colon. The inflammation associated with the disorder destroys tissue, causing ulceration and necrosis. Symptoms may be intermittent or continuous and include abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The faeces are generally watery and may contain blood and mucus. Complications of ulcerative colitis include haemorrhage, formation of abscesses or fistulas and bowel obstruction.

Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis) affects all layers of the ileum and/or the colon. Sometimes the regional lymph nodes and the mesentery are also involved. Symptoms vary according to the site and extent of the lesions and, in acute episodes, the individual experiences lower right abdominal pain and cramps, flatulence, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting, and pyrexia. The faeces may contain large quantities of blood and mucus. Complications of Crohn’s disease are similar to those of ulcerative colitis. Chronic or prolonged episodes of inflammatory bowel disease lead to nutritional imbalances and marked weight loss (Crohn’s and Colitis Australia (CCA) 2011).

Neoplastic disorders

Neoplasms of the digestive system may be benign or malignant. Obstruction of part of the digestive tract, such as the small intestine, may occur as an acute or chronic disorder.

Polyps are projections of the mucosal surface of an organ and may develop in the stomach or intestine. Polyps may be benign or malignant and the most common form is adenoma. An adenomatous polyp may begin in the benign form and later undergo malignant changes. Polyps may be asymptomatic or they may cause diarrhoea, haemorrhage or the manifestations of intestinal obstruction. Familial colonic polyposis is a hereditary disorder characterised by numerous polyps, and has a high association with colonic malignancy.

Cancer may develop in the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, intestines, rectum, liver or pancreas. The manifestations of cancer of the digestive system vary according to the site. The risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer by, for example, the age of 85 years is 1 in 10 for men and 1 in 14 for women. It is one of the most commonly occurring cancers, and the second most common cause of cancer-related death, after lung cancer, in European and Asian populations (World Cancer Research Fund 2011). It can develop with few, if any, early warning symptoms. Symptoms of bowel cancer include:

• Bleeding from the anus or any sign of blood after a bowel motion

• A recent and persistent change in bowel habit; for example, looser bowel motions, severe constipation and/or needing to go to the toilet more than usual

• Unexplained tiredness (a symptom of anaemia) and weight loss

• Abdominal pain, especially of recent onset (CCA 2011).

Screening tests for occult blood assist in early diagnosis of colorectal cancers (National Bowel Cancer Screening Program 2011).

Traumatic disorders

Trauma to parts of the digestive system may be related to injury or to irritation, such as the ingestion of a corrosive substance. Abdominal trauma may be localised or it may involve more than one abdominal structure. When a part of the digestive system is damaged the processes of digestion, absorption and elimination may be impaired. As a consequence, alterations in nutritional, electrolyte and fluid status occur. Depending on the type and extent of injury, the manifestations include external bruising, abdominal distension, pain, altered bowel sounds and haemorrhage, either internal and concealed, or presenting as haematemesis and/or melaena. Complications of trauma to the digestive system include haemorrhage, shock, infection, peritonitis and obstruction (Berman et al 2012; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Jarvis & Watt 2012).

End-of-life care

Management of constipation and incontinence in end-of-life care is a priority. Lack of appetite, inadequate intake and high opioid usage contribute to constipation and potential discomfort (Kyle 2010). Abdominal massage and fluid management adaptive to the client’s altered needs may assist, as well as appropriate continence aids to ensure the client is comfortable and maintains their dignity.

Diagnostic tests

Certain tests may be performed to assist or confirm the diagnosis of digestive system disorders.

Digital rectal examination

A digital examination is done with a gloved finger placed into the anorectal region to identify any physical abnormalities or constipation. This is an invasive and uncomfortable procedure and the client needs privacy and reassurance.

Screening

Screening is recognised as one method in the early detection of bowel cancer (Wood 2010). Clients are now able to screen for unseen blood in their stool which may be an indicator of a disease process. Faecal occult blood test (FOBT) involves placing small samples of stool on special cards and sending them to a pathology laboratory for analysis. The results are then sent back to the client and their designated doctor (CCA 2011).

Laboratory tests

Specimens that may be obtained from the client for laboratory analysis include blood, faeces, gastric or peritoneal fluid, urine and samples of tissue. Laboratory tests include:

• Histology, microbiology and cytology of stools

• The blood may be tested to determine haemoglobin level, haematocrit, leucocyte count, serum electrolytes, bilirubin levels, glucose levels or pancreatic enzyme levels

• The faeces may be tested to identify bleeding disorders, biliary obstruction, infections and disorders of digestion or absorption

• Gastric fluid analysis involves examination of gastric secretions, and may be performed by examining a specimen of vomitus or by testing a sample of the gastric contents aspirated via a nasogastric tube

• Peritoneal fluid analysis assesses a sample of peritoneal fluid obtained by abdominal paracentesis. The test may be performed when bleeding or infection is suspected by a medical officer. Abdominal paracentesis involves the insertion of a trocar and cannula through the abdominal wall to aspirate a quantity of peritoneal fluid

• The urine may be tested to detect the presence of any abnormal substance (e.g. bilirubin) which may be excreted in the urine as a result of a digestive system disorder

• Biopsy: specimens of tissue may be obtained during endoscopic examinations or surgery. The specimens are examined microscopically for changes in cellular structure, to confirm diagnosis or to determine the cause of a disease (e.g. malignancy) (Berman et al 2012; CCA 2011; Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Radiological examination

Several different types of radiological investigation may be performed:

• Plain x-rays may be taken to aid in the diagnosis of abdominal masses, bowel obstruction, trauma to abdominal organs and ascites

• Computerised tomography (CT) scanning involves the direction of a narrow x-ray beam at parts of the body, from various angles. Contrast medium is often administered intravenously to enhance visualisation. A computer reconstructs the information as a three-dimensional image on a screen

• Ultrasound involves the use of soundwaves to visualise body structures. A transducer is passed over the area, such as the abdomen, and receives echoes, which are bounced off body structures. The echoes are converted into electrical impulses, which may be viewed on a screen or photographed

• Fluoroscopy (visualisation with motion) involves use of a contrast agent (e.g. barium sulfate) which can be visualised as it passes through and outlines structures in the digestive tract. Fluoroscopic examination of the digestive tract includes barium swallow, barium meal and barium enema

• Defecating proctogram is an x-ray of the rectal region during defecation. A simulated stool is an oral contrast agent, composed of barium and a liquid, starchy substance and the client is required to pass this agent.

• Endoscopy is the visual examination of part of the digestive tract using a flexible fibreoptic endoscope. The endoscope also provides a channel for the introduction of instruments for the purpose of obtaining a sample of tissue for microscopic examination. The various forms of endoscopy derive their names from the part of the body being examined:

Care of the individual with a digestive system disorder

Although specific nursing actions and medical management may vary depending on the disorder, the main aims of care are to:

• Maintain standard precautions

• Monitor and maintain accurate bowel frequency and stool form scale

• Ensure accurate documentation and assessment to aid all health professionals in treatment

• Ensure hygiene needs are met, for example, that hand wash or sanitisers following bowel action are available

• Maintain skin integrity and appropriate personal hygiene

• Ensure environment is clean, fresh and appropriate to age and ability of the client

• Encourage appropriate fluids and diet

• Encourage appropriate and realistic exercise

• Ensure the client is in partnership with the health team in care planning and support client in accessing further information

• Investigate culturally sensitive issues specific to the lifestyle of the individual

• Maintain client dignity and support self-image deficits through exploration of potential for altered relationships both physical and emotional with significant others. Consider the issues such as teasing, bullying, altered physical relationships and carer expectations and stress.

Specific nursing activities include implementing measures to assist elimination from the bowel, observing and collecting excreta, and care of an individual with a stoma.

Care of client with a stoma

Specific disorders of the digestive tract may require surgical treatment involving the creation of an artificial opening on the abdominal wall. Part of the intestine is brought through this opening to form a stoma. A colostomy involves the creation of an artificial opening into a section of the colon, which is brought out through an opening in the abdomen. An ileostomy involves the creation of an artificial opening into part of the ileum, usually the terminal ileum, also brought out through an opening in the abdomen. As a result of both surgical procedures, faecal elimination occurs through the stoma, which may be created as a temporary or a permanent measure.

A temporary colostomy is created to divert faecal contents, for example, to allow healing of an incision in the distal colon or rectum. A permanent colostomy is indicated principally in colorectal cancer after a partial or total colectomy has been performed. A temporary ileostomy is created to rest the bowel, as in ulcerative colitis. A permanent ileostomy may be formed after total colectomy in the management of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. The site is selected according to which part of the bowel is affected and with consideration of the client’s physique, clothing, occupation and any other factors that may influence the client’s ability to successfully manage the care of the stoma.

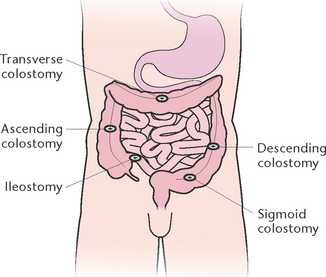

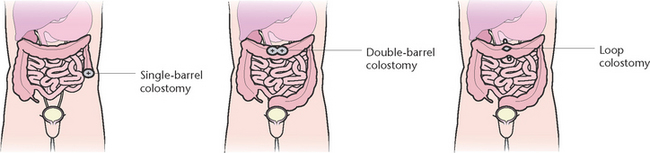

In many healthcare institutions a stoma therapist liaises with the client and surgeon to select the most appropriate site. The site of the stoma (Fig 30.8) will determine the consistency of the faecal matter excreted through it. The closer the stoma is to the small intestine, the more liquid the faeces will be. Faeces excreted through an ileostomy are liquid to paste-like, whereas faeces excreted through a sigmoid colostomy are semi-formed to solid. Figure 30.9 illustrates the types of colostomy or ileostomy that may be created.

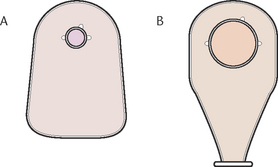

Care of the client with a stoma includes the selection and management of appliances (Fig 30.10), care of the stoma and surrounding skin, colostomy irrigation, meeting nutritional needs and providing psychological support. A stoma therapist may be available to assist in the preparation of the client and their significant others before the operation and also plays a major role in providing support and education after the operation. Dietary changes are necessary and are made in partnership with the client, stoma therapy nurse and dietitian.

When planning care considerations concerning the individual’s altered body image and/or the impact on intimate relationships the client’s questions need to be responded to in a sensitive, private and dignified manner (see Procedural Guideline 30.3). When sexual dysfunction as a result of altered body image, depression or illness impacts on the client and their partner they may need referral to a professional.

Procedural Guideline 30.3 Changing an ostomy appliance

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Explain the procedure to the client and provide privacy | Reduces anxiety and embarrassment |

| Place the equipment in a convenient location | Facilitates performance of the procedure in an organised manner |

| Perform hand hygiene and put on gloves | Prevents contamination |

| Remove the old appliance gently and place it in a plastic bag. Remove the skin barrier (if applicable) | Avoids damage to surrounding skin surface |

| Wipe the stoma and surrounding skin, using swabs and warm water. Pat dry | Cleanses the skin of mucus and faecal drainage |

| Inspect the stoma and surrounding skin. The stoma should be pink or red, and free from excoriation | Deviations from normal must be reported immediately so that appropriate action can be planned |

| Apply the skin barrier to the surrounding skin | Protects the skin |

| Remove the adhesive backing and place the new appliance over the stoma. Ensure that it is secured frmly in position with no gaps exposing the skin around the base of the stoma | Prevents leakage of faeces |

| Assist the client into a comfortable position and attend to their needs | Promotes comfort |

| Remove the equipment and attend to it in the appropriate manner. Perform hand hygiene | Prevents odour and cross-contamination |

| Document and report the procedure | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

Summary

The functions of the digestive system are to ingest and digest foods so that nutrients can be absorbed into the bloodstream, and to eliminate wastes from the body. Normal functioning may be impaired as a result of alterations in swallowing, secretory function, motility, digestion, absorption or elimination. Disorders of the digestive system can be classified as those occurring from multiple causes, from inflammation or infection, as a result of neoplasms, obstruction or as a result of injury. Diagnostic tests used to assess digestive system function include laboratory analysis of body fluids, excretions or tissue; radiological examinations; and endoscopy. Care of the client with a digestive system disorder includes preventing and managing altered elimination, promoting comfort, maintaining skin and mucous membrane integrity and maintaining nutritional and fluid status. These tasks need to be balanced by supporting the client through often undignified and embarrassing procedures. Maintaining their self-esteem and encouraging a team approach from all healthcare providers to ensure an optimum lifestyle for the individual is crucial for satisfactory patient-centred outcomes.

1. Maria has arrived in ER pointing to her epigastric region and moaning in pain. Her ECG is normal. What would be your first considerations in preparing her for investigations?

2. John, 22 years of age, returned with long-term diarrhoea from a 6-month stint volunteering in a developing country. What are the nursing implications of this and how would you help him?

3. Lee has end-stage dementia and is under a palliative care plan. What aspects of her bowel elimination care need considering?

4. Francine, an elderly client, is admitted with a history of 3 days of diarrhoea. What are the possible causes of diarrhoea? What is your primary concern for this client? What key information should be charted regarding the bowel actions?

5. Julianne, 28, has been diagnosed with IBS. What are the classic symptoms affiliated with IBS? What client education points can you cover with Julianne to assist her in managing IBS?

6. John, 50, is admitted for a colonoscopy because of a family history of bowel cancer and because he has had intermittent presence of blood in his bowel actions. What education can you provide John about this procedure?

1. Describe the digestion process in the large intestine.

2. Consider the psychosocial impact of bowel disease on the client and their family.

3. Describe the different types of hepatitis.

4. Describe how assessment of faeces assists in the application of laxatives.

5. Identify the factors that affect bowel elimination.

6. Outline five (5) causes for the onset of diarrhoea in a client.

References and Recommended Reading

Berman A, Snyder S, Kozier B, et al. Kozier and Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 2nd edn. Pearson, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 2012.

Boldero R, Bell RJ, Urquhart D, et al. Prevalence of faecal incontinence and its relationship with urinary incontinence with women living in the community. Menopause. 2011;18(6):685–689.

British Medical Journal Best Practice. Acute appendicitis. Online. Available http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/290/treatment.html, 2011.

Brown S. Health and Illness in Older Adults. Pearson, Frenchs Forest NSW, 2007.