CHAPTER 32 Sensory abilities

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the position and structure of each sense organ

• Describe the physiology of taste, smell, sight and hearing

• Describe the factors affecting sensory functions in the sense organs

• Describe the major manifestations of disorders of the eye and ear

• Describe diagnostic tests that may be used to assess eye and ear function

• Plan and implement nursing care for the client with altered sensory function

The sensory abilities of taste, smell, touch, sight and hearing enable the client to ‘sense’ changes in their external and internal environments. This is an essential requirement for maintaining homeostasis so we can interact with the world around us. Perception of stimuli has its origin in the five special sense organs, which are adapted to receive specific stimuli: tongue (taste); nose (smell); skin (touch); eyes (sight); and ears (hearing and maintenance of balance). Receptors in the sensory organs pick up stimuli from the environment and transmit information to the brain via pathways in the nervous system. In the brain the information is processed and interpreted. A person’s senses are essential for growth, development and survival. A person can initiate protective reflexes only if they can see or sense a change or danger. Sensory stimuli give meaning to events in the environment. Alterations in sensory function may lead to dysfunctions of sight, hearing, smell, taste, balance or coordination.

As the eyes and ears are the two major structures by which an individual receives information about the external environment, this chapter focuses on the care of these two organs. The eye is the means by which light is reflected from objects and travels to the retina so that an image is formed. Nerve endings in the retina transmit electrical impulses along the optic nerve to the brain for interpretation. The ear is the means by which soundwaves are collected and amplified. Nerve endings in the inner ear transmit electrical impulses along the auditory pathways to the brain for interpretation. The auditory system is also responsible for maintenance of balance.

I would be walking to the kitchen, and would feel dizzy, then I would feel like the floor was moving, the only way I could stay on my feet was to feel my way along using the wall. It was a scary feeling and would just happen.

Sometimes I would feel an uncontrollable wave of nausea pass over me, these would come and go without any warning.

As these symptoms became more frequent I thought it was something dreadful, so when my doctor told me it was Ménière’s syndrome, at first, until he explained it to me, I was very concerned I would have to live with these symptoms for the rest of my days. But by taking medication my symptoms completely disappeared.

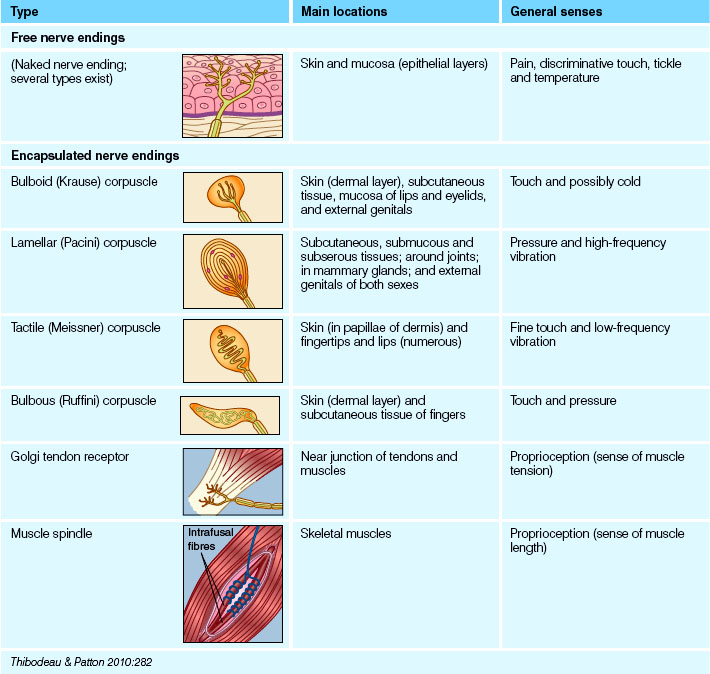

CLASSIFICATION OF SENSE ORGANS

Sense organs can be classified as special and general sense organs. Special sense organs such as the eye and the ear are characterised by being large and complex organs, or having localised groups of special receptors for specific and specialised detection of stimuli. The general sense organs are for detecting stimuli such as pain and touch. They have microscopic receptors and are distributed throughout the entire body. An example of a general sense organ is the skin (see Table 32.1).

Receptors in general sense organs, for example, the skin, are scattered over almost the entire body. The skin over different parts of the body will respond differently because of the differing numbers of touch receptors. Touch receptors are distributed closely together over the fingertips and far apart across the back and torso. Stimulation of some receptors will lead to the sensation of vibration, while others give the sensation of pressure, of pain (pain receptors) or of temperature (thermoreceptors).

Many general receptors are present in deep tissue; there are stretch receptors in your stomach that signal when it is full. There are important chemoreceptors in the aorta that detect changes in blood pH and carbon dioxide levels.

Special sense organs

The taste receptors

The chemical receptors (chemoreceptors) that generate the nervous impulses that result in the sense of taste are called the taste buds. Taste buds are scattered in the oral cavity, with most concentrated over the surface of the tongue (Fig 32.1) and a few found on the soft palate and the inner surface of the cheeks. These chemoreceptors respond to substances present in food and generate nerve impulses that are transmitted to the brain for interpretation. The upper surface of the tongue is covered with small projections (papillae), some of which contain a taste bud. Each taste bud consists of sensory and supporting cells situated in the epithelium and opening into the surface through a small gustatory pore.

Between the cells of the taste bud lie the endings of afferent nerve fibres derived from several cranial nerves. Taste buds on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue connect with fibres of the facial (seventh cranial) nerve. Taste buds on the posterior one-third of the tongue are associated with the fibres of the glossopharyngeal (ninth cranial) nerve, while pharyngeal taste buds send impulses to the brain via the vagus (tenth cranial) nerve.

These taste buds can differentiate among sweet, salty, sour and bitter stimuli. The tip of the tongue is the most sensitive to sweet and salty substances; the edges of the tongue are most sensitive to bitter substances. Substances must be in solution (saliva) so that they can reach every opening in a taste bud and stimulate the nerve ending. Molecules pass into solution on the surface of the tongue and combine with the surface membranes of the receptor cells. Transmitter substances are released, which evoke action potentials on the sensory nerve fibres. Fibres from the seventh, ninth and tenth cranial nerves carry the taste impulses via the brainstem to an area of the cerebral cortex where the taste is experienced.

The sense of taste is intricately linked with the sense of smell, and the sense of taste depends on stimulation of the olfactory receptors. Both senses have a protective function; for example, in detecting substances that may be harmful. Interruption of the transmission of taste stimuli to the brain may cause taste abnormalities. Taste abnormalities may result from trauma, infection, vitamin or mineral deficiencies, neurological or oral disorders and the effects of drugs. Because tastes are most accurately perceived in a fluid medium, mouth dryness may interfere with taste. Alterations in taste may include ageusia (a complete loss of taste), hypogeusia (a partial loss of taste), dysgeusia (a distorted sense of taste) and cacogeusia (an unpleasant taste).

The smell receptors

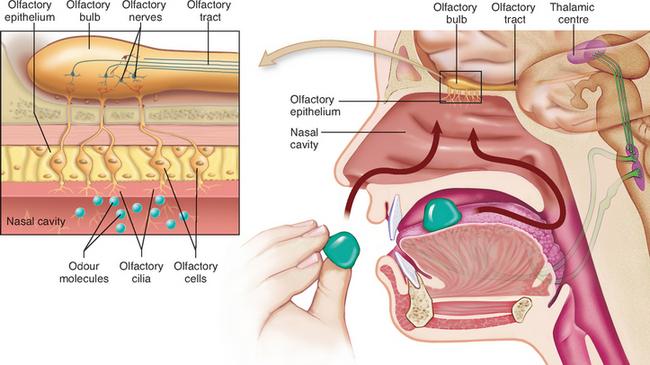

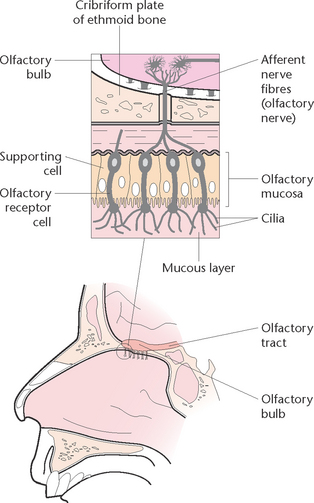

The chemoreceptors responsible for the sense of smell are located in a small area of epithelial tissue in the upper part of the nasal cavity (Fig 32.2). These chemoreceptors are known as the olfactory receptors. They respond to airborne chemicals and generate impulses that are transmitted to the brain for interpretation.

When these receptors are stimulated by chemicals they transmit impulses along the olfactory nerve to the brain. These receptors adapt quickly when exposed to an unchanging stimulus, which means that the client can become accustomed to an odour when constantly exposed to it.

Permanent alterations in the sense usually result when the olfactory neuroepithelium or part of the olfactory nerve is destroyed. Permanent or temporary loss can occur from inhaling irritants such as acid fumes that paralyse nasal cilia. Conditions such as ageing, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease may alter the sense of smell. Alterations in smell include anosmia (a total loss of sense of smell), hyposmia (an impaired sense of smell) and parosmia (an abnormal sense of smell).

There is a close relationship between the sense of smell and the sense of taste, and therefore they are not always distinguishable. The sensations of smell and taste play an important part in stimulating the secretions of digestive juices.

The nurse plays an important role in promoting the sense of taste and stimulating the sense of smell when caring for a client with altered sensory function. Client education regarding good oral hygiene practices will enhance taste perception. Discuss with the client which foods are the most taste appealing. If taste perception is improved, food intake and appetite will also improve. Taste perception is increased when food is seasoned. The client’s sense of smell can be stimulated by pleasant aromas such as flowers, perfumes and food.

THE EYE

Structure of the eye

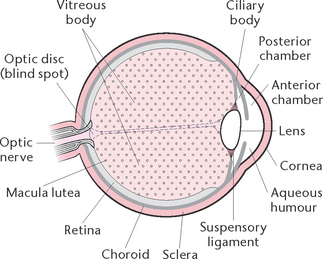

The eye is a spherical structure (Fig 32.3) about 2.5 cm in diameter, consisting of three principal layers.

The outer layer

The outer fibrous layer consists of the sclera and the cornea, which is a transparent structure continuous with the sclera. About five-sixths of the outer surface is made up of a tough white opaque fibrous layer (sclera), while the cornea comprises the anterior one-sixth. Both the sclera and the cornea consist of layers of collagen fibres. In the cornea the fibres are regular in size and arrangement, which accounts for its transparency. The cornea functions as a refracting and protective layer through which light rays pass en route to the brain.

The middle layer

The middle pigmented vascular layer is composed of three structures: the choroid, the iris and the ciliary body. The choroid is a layer of tissue that lies between the sclera and the retina. It is composed largely of blood vessels, and contains highly pigmented cells that absorb light and prevent it from being reflected within the eyeball.

The iris is a pigmented circular membrane between the cornea and the lens, and gives the eye its colour. Sphincter and dilator muscles within the iris regulate the central aperture (the pupil). By either dilation or constriction of the pupil, the amount of light entering the eye is regulated. The pupil appears black because light rays entering the eye are absorbed by the choroid and are not reflected.

The ciliary body is a thickened area of the choroid, lying anterior to the choroid extending to the root of the iris. A circular array of fibres stretches from the ciliary body to the lens to hold it in place. The ciliary body controls focusing of the lens and contains glands that secrete aqueous humour.

The innermost layer

The innermost lays is a thin structure called the retina. The retina lines the inner wall of the posterior portion of the eyeball and is comprised of a number of layers. The two main layers are the pigmented layer (the outermost layer of the retina, lying next to the choroid, and whose cells contain melanin) and the rod and cone layer, which lies next to the pigmented layer and is highly sensitive to light.

Rods and cones (specialised nerve endings) are distributed as a tightly packed mass throughout the retina, except at a point where the ganglionic fibres converge to form the optic nerve. This area, which is about 1.5 mm in diameter, is termed the optic disc. Since it possesses no photosensitive cells it is also known as the ‘blind spot’. The prime function of rods and cones is to absorb light. Rods can be stimulated by dim light and allow perception of shapes and movement in dim light. Rods also provide far peripheral vision. Cones are specialised for fine visual discrimination of colour perception. There are three types of cones: one type responds mostly to blue light, another to red light and the third type responds to green light.

In the centre of the retina is an oval yellowish area, the macula lutea, and in the centre of the macula lutea is a small depression, the fovea centralis. Because the photosensitive cells are more exposed to light here than over the rest of the retina, visual acuity is at its highest here.

Extraocular structure—accessory structures

Extraocular, or accessory, structures of the eye are portions of the eye outside the eyeball. These structures consist of the eyebrows, eyelids, eyelashes and lacrimal apparatus. The eyeball is anchored into position by several structures, including the extraocular muscles, the conjunctiva and the eyelids. The eyeball is surrounded and protected by a bony orbit, the eyebrow ridge and some fatty tissue. The eyeball is lubricated by the lacrimal glands.

The extraocular muscles bring about rotational movements of the eyeball. The muscles arise from the orbit and consist of four rectus muscles, which are attached to the sclera, and two oblique muscles. The oblique muscles are arranged so that for part of their length they lie around the circumference of the eyeball. The eyebrows and eyelashes are short coarse hairs that shade the eyes and protect the eyes from dust and sweat. The eyelids consist of connective tissue covered by skin and lined with mucous membrane. The lining is reflected over the eyeballs, and is called the conjunctiva. The eyelids protect the eye from foreign bodies and excessive light, as well as distributing tears by blinking.

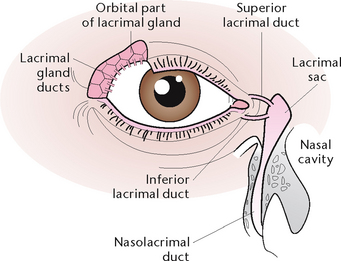

The lacrimal apparatus consists of the lacrimal gland, which is situated over the eye at the upper outer corner and secretes tears, which constantly wash over the conjunctiva (Fig 32.4). Tears leave the gland via several small ducts, and pass over the front of the eye eventually draining into the lacrimal sac, which is the expanded end of the nasolacrimal duct. Tears are secreted on to the anterior surface of the eyeball and are spread over it by the blinking movements of the eyelids. An antimicrobial substance in tears protects the eyes against microorganisms. Excess tears drain down the nasal cavity. The lacrimal glands are stimulated in response to chemical and mechanical irritants, thus producing tears to wash away irritants. Tears may also be produced as a result of emotion such as sadness or happiness.

The refractive media

The refractive media are the transparent parts of the eye, and have the ability to bend light rays at the surfaces of two transparent media. The refractive media are the cornea, the lens, the aqueous humour and the vitreous humour. The cornea functions as a refracting and protective layer through which light rays pass en route to the brain.

The lens is a transparent, biconvex encapsulated structure suspended from the ciliary body posterior to the iris. The lens is an elastic structure and this allows its shape to change when the eye is focused. The function of the lens is to refract (bend) light rays and to focus them on the retina.

Aqueous humour is a clear watery fluid that fills the cavities around the lens. These cavities are called the anterior and posterior chambers. Aqueous humour is derived from the plasma in the capillaries of the ciliary body, and passes into the posterior chamber. It then passes forwards through the pupil to the anterior chamber, where it is absorbed into the ciliary veins. The rate of secretion and re-absorption is balanced so that intraocular pressure is regulated. Aqueous humour serves as a refractory medium and provides nutrients to the lens and cornea.

Vitreous humour is a clear jelly-like substance that fills the intraocular space from the posterior lens to the retina. Because it does not regenerate, any significant loss of vitreous humour—for example, as a result of injury to the eye—may distort other ocular structures. Vitreous humour helps to maintain the shape of the eyeball, helps keep the retina in position and helps with the refraction of light rays.

The physiology of sight

Light travels from its source to various objects, where it undergoes reflection. This reflected light can then travel towards the eye, where it passes through the cornea, aqueous humour, the lens and the vitreous humour, before forming an image on the retina. Nerve endings in the retina transmit electrical impulses along the optic nerve to the brain. A coordinated process of refraction, accommodation, regulation of pupil size and convergence makes normal binocular vision possible.

Refraction

Refraction, or bending of light rays, occurs as the light waves pass through the cornea, aqueous humour, the lens and the vitreous humour. At the lens the light is bent so that it converges at a single point on the retina.

Accommodation

Accommodation is the process whereby the curvature of the lens is altered to that the eye is able to focus light from objects at different distances. As an object moves closer to the eye the curvature of the lens increases so that the image remains in focus on the retina.

Regulation of pupil size

The diameter of the pupil influences image formation, and the muscles of the iris respond to changes in light intensity. An increase in light intensity initiates constriction of the pupil, whereas a decrease in light intensity causes dilation of the pupil. Adjustment of pupil size therefore regulates the amount of light entering the eyes. Too much light may damage the retina, and too little fails to stimulate it.

Convergence

Convergence is the medial movements of the two eyeballs so that they are both directed towards the object being viewed. Convergence allows light rays to fall and stimulate two identical spots on the retinas, resulting in the perception of a single image.

After an image has been formed on the retina by the processes of refraction, accommodation, regulation of pupil size and convergence, light impulses are converted into nerve impulses by the rods and cones. The light breaks down the photosensitive chemical in either rods or cones, which stimulates electrical impulses to the brain for interpretation.

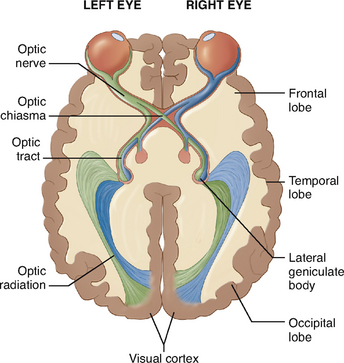

Nerve impulses travel from the retina along the optic nerve. The optic nerve emerges from the back of the eyeball and passes to the optic chiasma, an area at the base of the brain.

The fibres then form the left and right optic tracts, which continue to the visual areas of the brain in the occipital lobes. Here, further processing occurs so that the image is given meaning.

THE EAR

Hearing is a special sense that allows individuals to experience the world in which we live by providing a pathway for sounds to reach the brain. The ear is specially adapted as the organ of hearing but it is also concerned with the sense of position, balance and equilibrium. Hearing is a complex mechanism in which the ears receive sound waves and convert them into nerve impulses. The nerve impulses are transmitted by the acoustic nerve to the brain where they are interpreted. The externally visible portion of each ear is located on the lateral surface of the head on each side. The remaining parts of each ear are embedded in the bone of the skull.

Structure of the ears

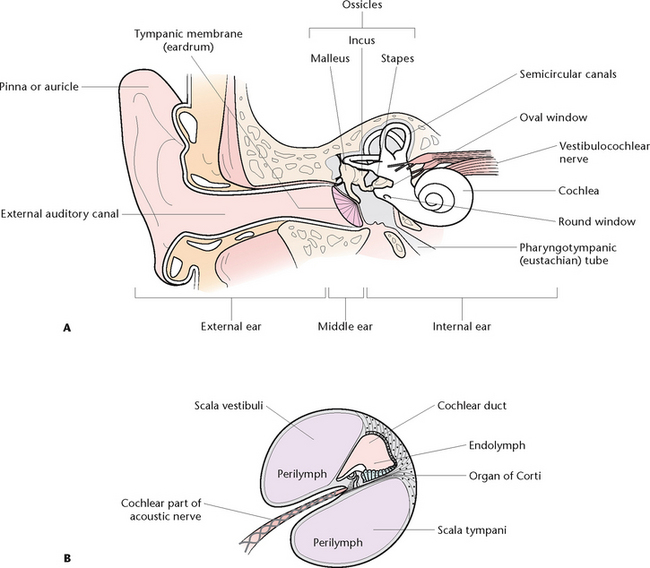

Each ear can be divided into three areas: the external, the middle and the inner ear (Fig 32.5).

Figure 32.5 The ear A: The parts of the ear B: A section of membranous cochlea showing the organ of Corti

The external ear

The external ear consists of the auricle (pinna) and the external auditory canal. The auricle consists of a piece of elastic cartilage with a number of associated ligaments and muscles, and has a small amount of adipose tissue in the earlobe. The skin of the auricle is covered with fine hairs and is continuous with the skin lining the external auditory canal. The external auditory canal is an S-shaped canal about 2.5 cm long. It extends from the auricle to the tympanic membrane (eardrum). The skin lining the canal contains glands that produce cerumen (wax) that protects the lining from damage and keeps dust particles away from the eardrum. The tympanic membrane lies between the external ear and the middle ear. It is a semi-transparent sheet consisting of three layers. The outermost layer consists of hairless skin, the middle layer is connective tissue and the innermost layer is continuous with the mucous membrane lining of the ear.

The middle ear

The middle ear, or tympanic cavity, is a small chamber within the temporal bone. Three small bones, or ossicles, lying in the middle ear transmit sound from the tympanic membrane to the oval window. Because of their shapes, the bones are named the malleus (mallot), the incus (the anvil) and the stapes (the stirrup). The malleus is attached to the tympanic membrane; the stapes is attached to the oval window; and the incus articulates with the other two ossicles. The three ossicles are attached to the wall of the middle ear by ligaments. The auditory tube (or eustachian tube) connects the middle ear with air from the nasopharynx. It is about 3–6 cm long and is lined with mucous membrane. Normally the tube is flattened and closed at the pharyngeal orifice, but swallowing or yawning opens it briefly.

The inner ear

The inner ear consists of a bony cavity within the temporal bone known as the osseous labyrinth. It is lined with periosteum and filled with a fluid called perilymph. The three divisions of the osseous labyrinth are the cochlea, the vestibule and the semicircular canals. The cochlea is a spiralling bony cavity, which resembles the shell of a snail. It houses the organ of Corti, the receptor organ of hearing. The vestibule lies between the cochlea and the semicircular canals. It contains structures responsible for maintaining equilibrium during movement of the head. The semicircular canals consist of three canals (in each ear), arranged at right angles to each other. They are filled with endolymph (the fluid inside the membranous labyrinth at the ear) and contain specialised nerve endings that are stimulated by the movement of the endolymph. The semicircular canals assist the body to adjust to changes of direction. The movement of fluid in this area can cause the client to experience a feeling of dizziness.

The membranous labyrinth is a membrane consisting of three layers, and lies within the osseous labyrinth. In the areas where it is not attached to the osseous labyrinth it is surrounded by perilymph. The fluid contained within the membranous labyrinth is known as endolymph. Part of the membranous labyrinth is concerned with hearing and part is concerned with the position of the head in space. The ear is responsible for hearing and maintenance of equilibrium.

The physiology of hearing

Hearing is a sense that enables sound to be perceived. Sound waves are collected and directed by the auricle into the external auditory canal, where they pass through and cause the tympanic membrane to vibrate. They then pass through the middle ear by vibration of the ossicles, and into the internal ear. From the internal ear sound waves are transmitted to the brain, via the acoustic nerve, for interpretation. Perception of sound involves interpretation of pitch and intensity. The entire process of hearing involves the following steps:

• Movement of air molecules causes a sound wave to form

• The sound wave travels through the air to the auricle, which directs it into the external auditory canal

• The sound wave enters the auditory canal and comes in contact with the tympanic membrane, causing it to vibrate

• The vibrations are transferred to the ossicles, which begin to vibrate, and the sound wave is transmitted across the middle-ear cavity to the oval window and into the fluid-filled internal ear

• The sound waves set the cochlear fluids into motion. The receptor cells are stimulated, and the sound waves are transmitted along the acoustic nerve to the temporal lobe of the brain for interpretation.

Two qualities of sound, pitch and intensity, are important in the interpretation of sound. Pitch is related to the frequency of the sound wave. A high-frequency sound stimulates the neurons supplying the cells near the base of the cochlea. Low-frequency sounds stimulate neurons nearer the apex of the cochlea. Intensity is related to the loudness of sound and is measured in decibels (dB). A loud sound causes the nerve endings to be stimulated at a greater rate than does a softer sound. The intensity of normal conversational speech is about 60 dB, and a decibel level of 160 can cause bursting of the tympanic membrane.

Maintenance of equilibrium (balance)

Two structures within the internal ear, the semicircular canals and the vestibule, work together to help the individual maintain balance and equilibrium. Components of the semicircular canals alert the brain to rotational movement, and components of the vestibule alert the brain to gravitational movement. Movement of fluid in the canals gives a constant flow of information about body position and the speed and direction of any body movement. This information is used to coordinate movements and to maintain balance.

Sensory alterations

People become accustomed to certain sensory stimuli and when these change, the individual may experience discomfort. Factors that contribute to alterations in behaviour are as follows.

Sensory deprivation

Sensory deprivation is thought of as a decrease or lack of meaningful stimuli. Because of reduced stimulation, a person becomes more acutely aware of the remaining stimuli and often perceives these in a distorted manner. The individual often experiences alterations in perception, cognition and emotion (Clinical Interest Box 32.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.1 Clinical signs of sensory deprivation

• Excessive yawning, drowsiness and sleeping

• Decreased attention span, difficulty concentrating, decreased problem-solving ability

• Periodic disorientation, general confusion or nocturnal confusion

• Preoccupation with somatic complaints such as palpitations

Sensory overload

Sensory overload generally occurs when a person is unable to process or manage the amount or intensity of sensory stimuli. Factors that can contribute to sensory overload are:

Sensory overload can prevent the brain from ignoring or responding to specific stimuli. The clinical signs of sensory overload are listed in Clinical Interest Box 32.2.

Sensory deficits

A sensory deficit is impaired reception, perception, or both, of one or more of the senses. Impaired hearing and sight are sensory deficits. When only one sense is affected, other senses may become more acute to compensate for the loss. However, sudden loss of eyesight can result in disorientation. When there is a gradual loss of sensory function, people often develop behaviours to compensate for the loss; for example, a person with gradual hearing loss in the right ear may unconsciously turn the left ear towards the speaker. Clients with sensory deficits are at risk of both sensory deprivation and sensory overload (Berman et al 2012).

Factors affecting sensory function

A range of factors affect the amount and quality of sensory stimulation, including a person’s developmental stage, culture, level of stress, medications, illness and lifestyle. These are outlined in Clinical Interest Boxes 32.3 and 32.4; an interview is required to assess a client’s sensory-perceptual functioning.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.3 Factors that influence sensory function

Age

• Infants are unable to discriminate sensory stimuli. Nerve pathways are immature

• Visual changes during adulthood include presbyopia (inability to focus on near objects) and the need for glasses for reading (usually occurring from age 40–50)

• Hearing changes, which begin at age 30, include decreased hearing acuity, speech intelligibility, pitch discrimination and hearing threshold. Tinnitus often accompanies a hearing loss as a side effect of drugs. Older adults hear low-pitched sounds the best but have difficulty hearing conversation over background noise

• Older adults have reduced visual fields, increased glare sensitivity, impaired night vision, reduced accommodation and depth perception and reduced colour discrimination

• Older adults have difficulty discriminating the consonants (f, s, th, ch). Speech sounds are garbled and there is a delayed reception and reaction to speech

• Gustatory and olfactory changes include a decrease in the number of taste buds in later years and reduction of olfactory nerve fibres by age 50. Reduced taste discrimination and reduced sensitivity to odours are common

• Proprioceptive changes after age 60 include increased difficulty with balance, spatial orientation and coordination

• Older adults experience tactile changes, including declining sensitivity to pain, pressure and temperature

Environment

• Excessive environmental stimuli (e.g. equipment noise and staff conversation in an intensive care unit) can result in sensory overload, marked by confusion, disorientation and the inability to make decisions. Restricted environmental stimulation (e.g. with protective isolation) can lead to sensory deprivation. Poor-quality environmental stimuli (e.g. reduced lighting, narrow walkways, background noise) can worsen sensory impairment

Preexisting illness

• Peripheral vascular disease can cause reduced sensation in the extremities and impaired cognition. Chronic diabetes mellitus can lead to reduced vision, blindness or peripheral neuropathy. Strokes often produce loss of speech. Some neurological disorders impair motor function and sensory reception

(adapted from Potter & Perry 2008)

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.4 Cultural considerations affecting sensory function

An individual’s culture often determines the amount of stimulation that a person considers normal. The normal amount of stimulation associated with ethnic origin, religious affiliation and income level also affects the amount of stimulation an individual desires and believes to be meaningful.

It is important for nurses to be sensitive to what stimulation is culturally acceptable to each individual, e.g. in some cultures touching is comforting, whereas in others it is offensive.

Assessing sensory function

Nursing assessment of sensory-perceptual functioning includes:

• Nursing history: Clinical Interest Box 32.5 gives some examples of interview questions to elicit data about the client’s sensory-perceptual functioning

• Mental status, including level of consciousness, orientation, memory and attention span.

• Physical examination: the client’s specific visual and hearing abilities; perception of heat, cold, light touch and pain in the limbs; and awareness of the position of body parts

• The client’s environment: assess for quantity, quality and type of stimuli

• Social support network: the degree of isolation a person feels is significantly influenced by the quality and quantity of support from family and friends (Berman et al 2012).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.5 Interview to assess a client’s sensory-perceptual functioning

Visual

• How would you rate your vision (excellent, good, fair or poor)?

• Do you wear glasses or contact lenses?

• Describe any recent changes in your vision.

• Do you have any difficulty seeing near or far objects?

• Do you have any difficulty seeing at night?

• Have you ever experienced blurred vision, double vision, spots moving in front of your eyes, blind spots, light sensitivity, flashing lights or halos around objects?

Auditory

• How would you rate your hearing (excellent, good, fair or poor)?

• Describe any recent changes in your hearing.

• Can you locate the direction of sounds and distinguish various voices?

• Do you experience any dizziness or vertigo?

• Do you experience any ringing, buzzing, humming or crackling noises or fullness in the ears?

Olfactory

• Have you experienced any changes in your sense of smell?

• Do things (foods, flowers, perfumes, etc) smell the same as previously?

• Can you distinguish foods by their odours and tell when something is burning?

• Have you experienced any changes in appetite? (Changes in appetite may be related to an impaired sense of smell.)

DISORDERS OF THE EYE

Healthy vision requires three processes:

Normal eye function can be altered by a malfunction of any of these processes. Some of the pathophysiological causes of disruption of eye function can be congenital, degenerative, infectious, neoplastic or traumatic. The effects may be mild and temporary, severe or permanent. Disorders of vision include alterations in visual acuity, ocular movement, accommodation, refraction and colour vision.

Refraction disorders

Focusing a clear image of the retina is essential for good vision. In the normal eye, light rays enter the eye and are focused into a clear, upside-down image on the retina. The brain rights the image in our conscious perception but cannot correct an image that is not sharply focused. If the eyeballs are elongated, the image focuses in front of the retina, giving the retina a fuzzy image; this is known as myopia or nearsightedness. This can be corrected by refractive eye surgery or by using contact lenses or glasses.

If our eyeballs are shorter than normal, the image focuses behind the retina, also producing a fuzzy image; this condition is known as hyperopia or farsightedness. This can also be corrected by eye surgery or glasses (Thibodeau & Patton 2010).

As we age we develop an inability to focus the lens properly; this is known as presbyopia, and is the reason most people once they pass through middle age require reading glasses. The lens becomes firm and loses its elasticity; the ageing lens loses its ability to focus light rays and near objects appear blurred. People may also state that they are experiencing ‘halos’ which are coloured rings encircling bright lights, caused by alteration in the ocular media. Small moving spots or flecks seen before the eyes are commonly called floaters, and may be due to the ageing process as the vitreous material degenerates. Floaters may also be caused by retinal laceration, diabetic neuropathy or hypertension. Visual changes also include double vision, or diplopia. Photophobia may be caused by inflammation of the cornea or the iris and ciliary bodies.

An irregular, uneven curvature of the cornea or lens, astigmatism, can also be corrected by glasses.

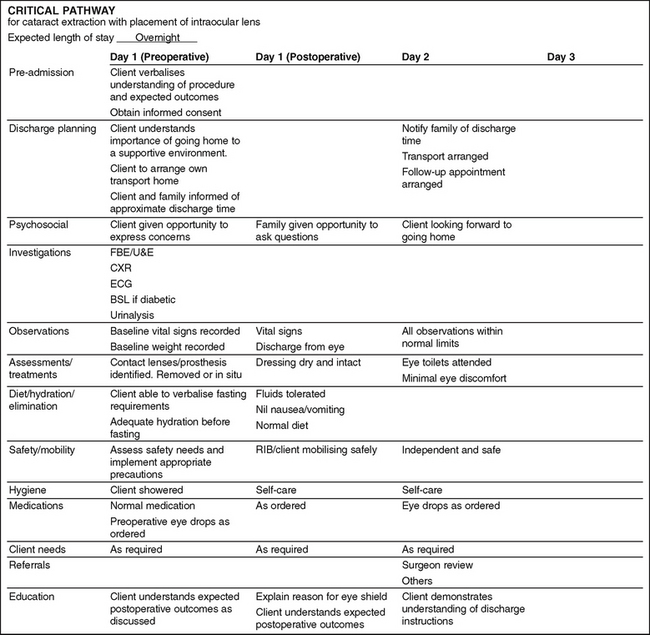

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye. Cataracts generally develop bilaterally, with each progressing independently, with the exception of congenital and traumatic cataracts. Causes include the ageing process, inflammation, malignancy, metabolic factors, toxins, heredity and trauma. Manifestations generally begin with a decrease in visual acuity. The client complains of not being able to see clearly. They may also complain of blurred vision, glare and a decrease in colour perception. As the cataract progresses, the pupil appears milky white. Surgical removal of the cataract from the lens is indicated when activities of daily living are affected. Figure 32.6 outlines a sample critical pathway for a client having a cataract extraction.

Infectious disorders

Infections of the eye and its associated structures also have the potential to impair vision, sometimes permanently.

Stye

A hordeolum (stye) is a localised staphylococcal infection of a sebaceous gland of the eyelid. This gland is the base of a hair follicle or eyelash. Manifestations include localised inflammation, swelling and pain.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis is inflammation of the eyelid margins. It may be caused by bacterial infection or an allergic reaction to smoke, dust or chemical. Seborrhoea, a disorder of the sebaceous gland, may also cause blepharitis. Manifestations include itching, burning, redness of the eyelid margins, chronic conjunctivitis and yellow purulent discharge crusts on the lashes.

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is the inflammation of the conjunctiva and may be caused by excessive exposure to wind, sun, heat, cold, allergens or chemicals, or by bacterial, viral or fungal infection. Manifestations include itching, burning, excessive tearing and pain. Allergic conjunctivitis may cause considerable swelling.

Trachoma

Trachoma is a chronic form of kerato-conjunctivitis that causes permanent damage to the cornea which, if untreated, can result in blindness. The condition results from infection by Chlamydia trachomatis and is associated with poor personal and community hygiene and lack of available clean water. There is a high incidence of trachoma among Australian Indigenous people. Manifestations, which may not become apparent for years, are similar to those for severe conjunctivitis. There is corneal inflammation and scarring, due to the eyelids turning inwards, which causes the lashes to rub against the cornea. Severe corneal scarring may result in blindness.

Keratitis

Keratitis is inflammation of the cornea and is frequently caused by trauma or infection. It usually affects only one eye, and frequently presents as a secondary infection to an upper respiratory tract infection involving cold cores (herpes simplex infection). Manifestations include opacity of the cornea, irritation, excessive tearing, blurred vision, redness and photophobia.

Orbital cellulitis

Orbital cellulitis is an acute infection of the orbital tissues and eyelids that does not involve the eyeball. The condition is generally secondary to infection of nearby structures. If orbital cellulitis is not treated, the infection may spread to the sinuses and meninges. Manifestations include unilateral eyelid oedema, inflammation of the orbital tissues and eyelids, pain, impaired eye movement and purulent discharge from indurated areas.

Disorders of the retina

Damage to the retina impairs vision because even a well-focused image cannot be perceived if some or all of the light receptors do not function properly, for example, in retinal detachment when part of the retina falls away from the tissue supporting it. The condition can result from normal ageing, eye tumours or a sudden blow to the head. Common warning signs are:

If left untreated the retina may detach completely and can cause total blindness (Thibodeau & Patton 2010).

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetes mellitus may cause a condition known as diabetic retinopathy which causes small haemorrhages in retinal blood vessels to disrupt the oxygen supply to the photoreceptors. The eye responds by building new, but abnormal, vessels that block vision and which may cause detachment of the retina.

Glaucoma

Another common condition that can damage the retina is glaucoma. This is excessive intraocular pressure caused by abnormal accumulation of aqueous humour. As fluid pressure against the retina increases, blood flow to the retina slows. The reduced blood flow cases degeneration of the retina and thus a loss of vision. There are various forms of glaucoma: primary open-angle, primary closed-angle, secondary, congenital and absolute. Generally speaking, glaucoma progresses slowly and may or may not be symptomatic. It rarely affects clients under 40 years of age. The condition may be caused by over-production of aqueous humour or obstruction to the outflow of aqueous humour, both of which result in accumulation of fluid and a rise in intraocular pressure. Manifestations of primary open-angle glaucoma are gradual and progressive; the client is unable to perceive changes in colour and experiences blurred vision and persistent aching eyes. Manifestations of primary closed-angle glaucoma occur suddenly. The client experiences intense pain, loss of vision, nausea and vomiting. The affected eye appears red, and the pupil is fixed, dilated and unresponsive.

The manifestations of secondary glaucoma are similar to those of the primary form depending on the cause. Congenital glaucoma is a rare disorder generally associated with other abnormalities, and manifests as a large-diameter cornea. Absolute glaucoma is the end result of any uncontrolled glaucoma resulting in blindness. Clinical Interest Box 32.6 provides information on glaucoma prevention and preservation of sight.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.6 Glaucoma prevention and preservation of sight

Routine eye screenings are recommended for early detection of glaucoma. Although it cannot at this time be predicted, prevented or cured, in most cases glaucoma can be controlled and vision preserved by early diagnosis. The client needs to be aware that certain prescription and over-the-counter medications can cause increased intraocular pressure and should not be taken without consulting their doctor. The client who has experienced an episode of acute angle-closure glaucoma is taught about the risks, warning signs and management of future attacks. Clients need to understand the importance of lifetime therapy and periodic eye examinations with intraocular measurement in controlling the disease and preventing blindness. The nurse should assess the client’s compliance with routine health screening.

Degenerative diseases of the retina

Degeneration of the retina can cause difficulty in seeing at night or in dim light. This condition, nyctalopia or night blindness, can be caused by a deficiency in vitamin A. Vitamin A is needed to make photo pigment in rod cells. Photo pigment is a light-sensitive chemical that triggers stimulation of the visual nerve pathway. A lack of vitamin A may result in a lack of photo pigment in rods, a condition that impairs dim-light vision (Thibodeau & Patton 2010).

Macular degeneration is degeneration of the central part of the retina, which is the area most essential to good vision. The exact cause of the degeneration is unknown, but the risk of developing this condition increases with age after reaching 50 years. Other risk factors are cigarette smoking and a family history of the disorder.

The most common cause of the degeneration is ageing. This disease is the leading cause of visual impairment in clients aged 50 years and over. Manifestations include loss of central vision, and activities that require fine detailed vision becoming impossible. The disease usually develops slowly and painlessly; and both eyes are generally affected. Vision may be improved in some cases by laser surgery. Generally blindness does not occur.

Disorders of the visual pathway

Damage or degeneration in the optic nerve, the brain or any part of the visual pathway (Fig 32.7) can impair vision. Damage to the visual pathway does not always result in total loss of vision; depending on where the damage has occurred, only part of the visual field may be affected.

SPECIFIC DISORDERS OF THE EYE

Congenital disorders

Strabismus

Strabismus is a condition of eye deviation in which the eyes fail to look in the same direction at the same time. The eyes may have uncoordinated appearance and the person may experience diplopia. Congenital strabismus is an anomaly in which there is a defect in the position and fusion ability of the two eyes. The condition is usually easily observed and, in addition to crossed eyes, the client may squint, tilt the head or close one eye to improve vision.

Ptosis

Ptosis, drooping of the upper eyelid, may be unilateral or bilateral. Congenital ptosis results from the failure of the levator muscle in the upper eyelid to develop. Manifestations are usually very obvious; the lid appears smooth and flat, and the client may tilt the head back to compensate if the lid droops over the pupil.

Neoplastic disorders

Benign or malignant tumours may arise in the tissues surrounding the eye, but neoplasms of the eyeball are rare.

Choroidal melanoma

A choroidal melanoma is a malignant tumour of the middle of the eyeball. The major symptom is visual distortion. There is generally no pain unless glaucoma develops.

Retinoblastoma

Retinoblastoma is a congenital hereditary neoplasm that develops from retinal germ cells. It is the most common malignancy of the eye in childhood. Manifestations include diminished vision, strabismus, retinal detachment and an abnormal papillary reflex. The tumour grows rapidly and may invade the brain and metastasise to distant sites.

Traumatic disorders

Abrasions

Abrasions are superficial scratches on the eyelid, conjunctiva or cornea. Corneal abrasions may be caused by foreign bodies or over-wearing of contact lenses. Manifestations include excessive tearing, pain, a sensation of something in the eye and photophobia.

Lacerations

Lacerations may involve the eyelids or the eyeball. Lacerations of the eyeball may lead to intraocular infection, cataract formation of loss of vision. Manifestations of a lacerated eyeball include severe pain and shock.

Contusions

Contusions of the eyeball involve a bruising injury in which intraocular damage occurs. The injury may result in bleeding into the anterior chamber (hyphema) or into the vitreous of surrounding tissues. Contusions generally result from a severe blow to the eye, such as from a fist, golf or squash ball. Manifestations include impaired vision, pain, bruising of the tissues surrounding the eye and blood in the anterior chamber.

Foreign bodies

Foreign bodies may enter the conjunctiva or cornea, or they may penetrate and perforate the eyeball. Examples of foreign bodies that gain entry include eyelashes, dirt and small particles of metal, dust and glass. Manifestations include irritation, pain, excessive tearing and photophobia.

Burns

Burns to the eye may result from exposure to a chemical, radiant energy or high temperatures. The extent of damage to the eye depends on the duration of exposure and the causative agent. Manifestations include extreme pain, excessive tearing, photophobia, inflammation or destruction of tissue and visual impairment.

Health promotion

The nurse is in a key position to educate clients and their families about the ways by which eyesight can be protected and preserved in children. For adults, screening of visual function is imperative to detect problems early. Regular eye examinations are important, especially for clients with a family history of eye disorders and for clients who are more vulnerable to ocular complications such as diabetes mellitus. Recommended screening guidelines are structured on the basis of age. People under 40 years of age should have periodic eye checks as required. Those aged 40–64 should have a complete eye examination every 2 years, and those aged 65 years and over should have a complete eye examination every year. Examination of the eyes is also recommended if a client experiences any disturbances of vision, pain, sudden appearance of floaters, photophobia, purulent discharge, trauma to the eye or pupil irregularities. Prevention of eye infection includes washing the hands before touching the eyes, and not sharing eye make-up, eye drops or ointment.

Education is particularly important for clients involved in high-risk occupations and activities. Client education should focus on strategies for prevention and first aid measures. Teach clients what immediate care to give to prevent permanent loss of sight, such as immediately flushing the eye with copious amounts of water if a chemical splash occurs. Prevention of injury includes wearing eye protection when working with chemicals or when the eyes may be exposed to dust, wood, metal or glass fragments. Protective eye wear should also be worn during recreational or sporting activities in which sticks or balls may contact the eye, such as squash. Excessive exposure to strong sunlight or sunlamps should be avoided, as these may damage the eyes. A common form of cataract, which can result from frequent exposure to intense sunlight, can largely be prevented if sun hats and good quality sunglasses are worn.

Prevention of eye fatigue includes using adequate illumination when reading or writing, resting the eyes often during prolonged use and reducing screen glare when using a visual display unit such as a computer screen. The nurse needs to inform the client and family of the importance of follow-up treatment and stress the importance of complying with prescribed activity restriction to prevent further eye damage, and of safe and careful application and correct storage of prescribed eye drops or ointments.

Diagnostic tests

Tests used to diagnose eye disorders may be classified as subjective, objective or special procedures. Subjective test require oral responses from the client that must be interpreted by the examiner. Objective tests are those in which the examiner obtains precise measurements or directly visualises the interior of the eyes.

Subjective eye tests

A visual acuity test evaluates the client’s ability to distinguish the form and detail of an object. Visual acuity is measured by the use of a Snellen chart. The client is required to read letters on this chart from a distance of 6 metres. Generally, the smaller the symbol the client can identify the sharper their visual acuity.

Colour vision tests evaluate the client’s ability to recognise differences in colour. The most common colour vision tests use plates made up of patterns of dots of primary colours, superimposed on backgrounds of randomly mixed colours. A client with normal colour vision can identify the patterns.

Accommodation tests evaluate the ability of the eyes to adjust to the curvature of the lenses. The examiner may perform this test by questioning the client concerning their visual acuity, while placing trial lenses before their eyes. Alternatively the test can be performed using an ophthalmoscope.

Visual field tests evaluate the functions of the retina, optic nerve and optic pathways. The client’s peripheral and central visual fields are assessed when the examiner moves an object from outside the field into the field, on a radial line, until the client states that they can see the object. Tangent screen examinations detect visual field loss. In this examination, a screen is used and test objects from 1–50 mm in size are placed on the screen. Each eye is individually tested for visualisation of the objects.

Objective eye tests

Intraocular pressure is assessed using a tonometer. A topical anaesthetic is instilled and the examiner places the tonometer on the apex of the cornea to determine pressure in the eye. An alternative method involves the use of an ‘air-puff’ tonometer that does not contact the eye. Tonometry serves as a valuable screening test for early detection of glaucoma.

Ophthalmoscopic examination involves the use of an ophthalmoscope to view the interior structures of the eye. The ophthalmoscope examines the fundus, or interior aspect, of the eye, allowing magnified examination of the optic disc, retinal vessels, macula and retina.

Slit-lamp examination allows the examiner to visualise in detail the anterior segment of the eye. Before the examination, dilating eye drops (mydriatics) may be instilled. The client sits with their chin on a rest and their forehead against a bar attached to the lamp. Slit-lamp examination helps determine corneal abrasions, dermatitis and cataracts.

Fluorescein staining is a technique in which staining the eye’s surface with dye provides a better view of the anterior portion of the eye. The test is generally performed when the conjunctival or corneal abrasions are suspected. Surface defects absorb more dye than normal areas.

Special procedures for assessing the eye

Fluorescein angiography involves rapid-sequence photographs of the fundus after intravenous injection of a contrast medium. Fluorescein angiography records the appearance of blood vessels inside the eye.

A culture to determine the microorganism causing ocular infection may be obtained by passing a sterile swab over the conjunctival surface.

Computerised tomography (CT) of the orbit may be used to detect abnormalities such as intraocular foreign bodies or retinoblastoma. Contrast dye is injected and the eyeball scanned.

Ocular ultrasonography involves the transmission of high-frequency sound waves through the eye, and measurement of their reflection forms the ocular structures.

Vetrasonography can identify abnormalities that are undetectable through ophthalmoscopy, and may be used to locate intraocular foreign bodies.

Care of the client with an eye disorder

While the general care of the client with a disorder of the eye is directed towards helping them to meet their needs, the three main aspects of care are:

Maintaining a safe environment

Any visual impairment or loss renders the client susceptible to injury; therefore the nurse has a responsibility to protect the client from environmental hazards. These hazards may include such things as low levels of lighting, poor colour contrast or badly positioned furniture. The nurse should describe the layout of the room to the client. If the client is ambulant, the nurse should encourage them to locate the various pieces of furniture so that they become familiar with their position in the room. Leave furniture and personal belongings in the same position in the room. Ensure that any doors are either fully closed or open, as a visually impaired client can easily by injured if a door is left ajar.

Nurses can foster independence in the hospitalised visually impaired client by encouraging self-sufficiency in completing activities of daily living, and improving self-esteem as the client attempts and masters activities.

Client education

Education involves assisting the client to adjust to a visual impairment. The nurse should initially describe to the client with the alteration to visual function what has occurred. The client who is experiencing visual loss that is either temporary or permanent needs assistance to adjust to the physical and psychosocial implications. Care of the client includes encouraging the client to express reactions and feelings to their visual loss. The visually impaired client may lose the ability to observe body language and the reading and writing components of communication. It is important for the client to be able to interact with people whom they encounter. Communication methods may also be taught to family members and significant others. Clinical Interest Box 32.7 provides information on preventive screening for children.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 32.7 Childhood preventive screening

The most common visual problem during childhood is refractive error, such as nearsightedness. In early childhood, parents may be alerted to a visual problem by reduced eye contact from their infant or the infant’s failure to react to light. Recommended screening guidelines are usually structured on the basis of age, and preventive screening occurs in pre-school-age children (ages 4–5 years), where the nurse’s role is one of detection and referral.

At school entry (age around 5 years):

• Examine eyes and observe for fixation, following, nystagmus, strabismus

• Test hearing; perform otoscopy on children failing audiometry to determine appropriate action

For more information visit Department of Education and Early Childhood Development: www.education.vic.gov.au/edulibrary/public/stuman/wellbeing/hwsfdp.pdf

Key aspects related to assisting the visually impaired client

• Encourage as much self-care as possible. The client who is experiencing recent visual impairment may need assistance until they adjust to their condition. A client who has been visually impaired for some time will probably have developed considerable self-reliance. The nurse should always consult the client when uncertain whether assistance is required.

• Address the client by name and identify yourself, visitors or others in the room. This avoids frightening the client and assists them in knowing who is in the room. It is also important to knock before entering and to inform them when you are about to leave the room.

• Speak to the client in the same manner as you would a fully sighted person. The nurse must suppress the urge to speak more loudly than usual, which people often do when conversing with a visually impaired client. There is no need to exclude words such as ‘look’ and ‘see’ from normal conversation.

• Any visual aids that the client uses should be kept in close proximity (Table 32.2). The client should have easy accessibility to the call bell if required.

• Encourage the client to maintain an interest in the outside environment through listening to the radio or television and discussing newspaper items.

• Provide full descriptions of people, places and things.

• Provide items that can compensate for diminished vision, such as bright non-glare lighting, large-print books, talking books, telephones with enlarged buttons and a clock with numbers and hands that can be felt.

• At mealtimes it may be necessary for the nurse to describe the position of foods on the plate (such as, peas are at 9 o’clock, potatoes at 12 o’clock, pumpkin at 3 o’clock and chicken at 6 o’clock).

• It is of particular importance to thoroughly explain any procedure or treatment before it is started. Whenever possible, if it will not affect sterility, the client should be allowed to feel any items used during a procedure.

• Provide contrasting colours; for example, non-white crockery and brightly coloured telephones, handles, borders or edges allow familiar objects to become more visible. Coloured tape, paint or nail polish can be used to colour-code appliance dials.

• Painting the edge of stairs with bright paint can help the client distinguish the edge of the step more clearly.

• Inform the client when they are approaching stairs or steps, remembering to let them know whether they are up or down.

• When walking with the client, the nurse should walk slightly ahead and let the client take their elbow. This technique ensures that client senses the direction they are walking towards. The nurse should encourage the use of handrails while ambulating and warn the client of any hazards as they are approached.

• Cultural aspects of care should always be taken into account when caring for a client who has impaired vision.

• On discharge, review specific hazards in the home with the client and family. Assessment must be made of both indoor and outdoor living arrangements. The client’s living quarters should not be altered after they have become familiar with placement of furniture.

• Inform the client and family that progress will be slow and that they will need to seek support from outside agencies. Encourage families to explore community resources available to clients with partial or total loss of vision, and the rehabilitation programs available to them. Some of these include: Association for the Blind; State and Territory Guide Dog Associations and Seeing Eye Dogs Australia; Australian Braille Authority; Vision Australia; Blind Welfare Australia; and Blind Citizens Australia. All coordinate services for the blind and visually impaired.

Table 32.2 Aids for the visually impaired

| Aid | Description |

|---|---|

| Magnifers | Hand-held or standing magnifers can be used to enlarge print, or for fne detail |

| Enlarged print | Large-print books, magazines and newspapers may be borrowed from the local library |

| Talking books | Tapes of books may be available on loan from agencies for the blind or from public libraries |

| Telephone aids | Special dials are available for telephones in both large print and braille |

| Braille | The braille system of writing and printing uses tangible points or dots, which the individual feels and ‘reads’ with the fingertips |

| Optical-to-tactile converters | Consist of devices that convert vision into tactile sensation, by reproducing the outline of a letter on a tactile screen |

| Canes | A variety of canes is available (e.g. a white or collapsible cane) which helps the individual to locate obstacles in the environment. Laser canes also locate objects and can identify changes in the region from as far away as 6 metres |

| Guide dogs | Trained dogs allow greater mobility and independence for the visually impaired person. The individual holds a U-shaped handle, which is attached to a harness on the dog. Communication between the two takes place through the movements of the harness. When a guide dog is working (i.e. when it is in harness) other people should not approach or pat the dog without the handler’s permission, as the dog may become distracted |

Local eye care

Various nursing procedures involving the eye should be performed in accordance with the policies of the healthcare institution. General principles that should be followed in all ophthalmic procedures include:

• Explain what you are going to do

• Ensure that the client is sitting or lying with their head well supported

• Ensure that there is adequate lighting; lights should never be allowed to shine directly into the client’s eyes

• Wash hands thoroughly before and after the procedure and wear disposable gloves to prevent cross-infection

• Use gentle unhurried movements and refrain from exerting any pressure on the eye

• Avoid touching the cornea with the fingers or equipment, to prevent corneal damage

• Use aseptic technique. When only one eye is infected or inflamed, the unaffected eye must receive attention first to prevent cross-infection

• Ensure that, if an eye pad is to be applied, the eyelid is closed firmly to avoid corneal abrasion.

Application of eye pads

A light eye pad may be applied to prevent further injury after trauma to the eye or to avoid eye damage after administration of a local anaesthetic. Before the eye pad is applied the client is asked to close their eyelid firmly. The pad should be applied so that the eyelid cannot be opened. Pressure should not be applied, unless a medical officer has prescribed it. The eye pad is secured into position using hypoallergenic tape, placing the tape diagonally from forehead to cheek.

Cleansing the eyelids

It may be necessary to cleanse the eyelids before: applying a compress; removing or inserting an artificial eye; instilling drops or ointment; removing discharge from the margins of the eyelids. A suggested technique for eyelid cleansing is outlined in Procedural Guideline 32.1. The equipment required includes:

• Extra sterile soft gauze squares

• Sterile solution (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride or sterile water, warmed to body temperature)

Procedural Guideline 32.1 Cleansing the eyelids

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Explain the procedure and ensure privacy | Reduces anxiety |

| Starting with the less affected eye, assist the client into a recumbent position, with the head tilted towards the side | Minimises the risk of accidental infection from the other eye. Facilitates performance of the procedure |

| Place the equipment in a convenient location and ensure adequate lighting | Facilitates performance |

| Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Place a towel under a kidney dish beside the client’s cheek. Observe eyelid for abnormalities | Provides a receiver for excess lotion and used swabs |

| Using sterile technique, open sterile pack and add sterile solution and extra gauze swabs | Reduces risk of infection |

| Perform procedural hand wash and don gloves | Reduces risk of cross-infection |

| Beginning with the less affected eye, ask the client to close the eye | Reduces the risk of solution entering the lacrimal duct or contaminating the other eye |

| Moisten gauze swabs and cleanse eyelids, from inner canthus to outer canthus, using each swab once only. Use swabs to gently dry the eyelids | Prevents cross-infection |

| If necessary, cleanse the lid of the other eye, after repositioning the head | Both eyes may need treatment |

| Assist the client into a comfortable position | Promotes comfort |

| Remove and attend to the equipment appropriately | |

| Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report and document the procedure | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

Eye irrigation

Irrigation is a technique performed to flush secretions, chemicals or foreign bodies from the conjunctival sac. Chemical injuries to the eye require flushing of the conjunctival sac with copious amounts of solution. It may be necessary to cleanse the eyelids before irrigation; for example, if there is excessive discharge or crusting. A suggested technique for eye irrigation is outlined in Procedural Guideline 32.2.

Procedural Guideline 32.2 Eye irrigation

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Explain the procedure and ensure privacy | Reduces anxiety |

| Assist the client into a recumbent position, with the head tilted towards the affected side | Prevents the solution running either over the cheek into the other eye or out of the affected eye and down the side of the nose |

| Place a towel under the head on the affected side and across the neck. Place a kidney dish against the client’s cheek and ask the client to hold it in position | Prevents solution from fowing down the neck |

| Perform hand hygiene and put on gloves | Prevents cross-infection |

| Pour irrigating solution into the undine or open the container of eye wash. Gently hold the eyelid open with one hand | The client will instinctively try to close the eye |

| Hold the spout of the undine or the container 2.5 cm away from the eye | If the undine is held too high, fluid will flow at increased pressure, causing discomfort and possible damage to the eye |

| Pour a little solution over the cheek first | Accustoms the client to the feel of the solution |

| Direct the flow of solution from the nasal corner outwards | Because the head is tilted, the stream of irrigating solution will flow over the eyeball and prevent contamination of the other eye |

| Avoid directing the stream forcefully onto the eyeball, and avoid touching the eye’s structures | Prevents discomfort and damage to the eye |

| Ask the client to look up and down and to either side while irrigating | Ensures that the whole area is washed |

| When the eye has been thoroughly irrigated, ask the client to close the eyes, and use a new gauze swab to dry the lids | Promotes comfort |

| Make the client comfortable | Promotes comfort |

| Remove and attend to the equipment appropriately. Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report and document the procedure | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

Instillation of drops or ointment

Eye drops or ointment that may be prescribed include those that combat infection, dilate or constrict the pupil, act as a local anaesthetic, stain the cornea, reduce inflammation or reduce intraocular pressure. Eye drops or ointment are instilled only when they have been prescribed by a medical officer, and the nurse who is instilling them must follow the regulations and policies regarding the administration of medications. Key aspects regarding the use of ophthalmic medications include:

• Checking the name, strength and amount of drops or ointment to be instilled. The nurse must also check the time and frequency of administration and into which eye the medication is to be instilled. The expiry date on the container must also be checked, and the medication discarded if the expiry date has passed

• Ensuring that a separate container for drops or ointment is supplied for each individual. Single-dose packaging is preferred, as contamination of the medication is likely to occur if the container is used repeatedly

• Using the container correctly. To prevent cross-infection, eye drops are supplied in a squeeze bottle with a nozzle top through which the drops are delivered.

Eye prostheses

Two types of eye prosthesis are contact lenses and the artificial eye.

Contact lenses: a contact lens is a small plastic disc that is positioned on the cornea and held in place by surface tension. A client who has a refractive error, for example astigmatism, may wear contact lenses in place of glasses. A variety of lenses is available including hard, soft, gas permeable, extended wear, daily wear, coloured and disposable. It is important to know that all lenses require care and must be removed periodically to prevent corneal damage and eye infection. Client education is required regarding proper lens care; for example, daily wear lenses should be removed overnight for cleaning and disinfection. Only the recommended solutions should be used for cleaning, soaking and storing lenses. Wetting lenses with contact lens solution before insertion minimises discomfort. The hands should be washed and dried before insertion or removing lenses (see Procedural Guideline 32.3).

Procedural Guideline 32.3 Inserting and removing a contact lens

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Insertion | Removal |

|---|---|

| Perform hand hygiene | Perform hand hygiene |

| Place the lens on the tip of an index finger | With the individual looking up, the lens is slid down off the pupil with an index finger |

| The lids are held apart with the other hand | The lens is gently squeezed with the thumb and index finger and lifted off the eye |

| With the individual looking straight ahead, the lens is placed over the cornea | Alternatively, the lens is removed using a small rubber suction extractor |

| Releasing both eyelids, the individual blinks to centre the lens over the pupil |

Artificial eyes: An artificial eye may be inserted after surgical removal of an eye. Clients with artificial eyes have had enucleation of an entire eyeball. An artificial eye may be removed from the socket, cleaned and replaced. Alternatively, the prosthesis may remain in the socket permanently. Most clients prefer to care for their own eyes but there may be times when assistance from the nurse is required. When a prosthesis is removed from the socket it is placed in warm normal saline for cleansing (see Procedural Guideline 32.4).

Procedural Guideline 32.4 Inserting and removing an artificial eye

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Insertion | Removal |

|---|---|

| Perform hand hygiene | Perform hand hygiene |

| The socket is cleansed with warm sodium chloride 0.9% solution | The individual assumes a comfortable sitting or lying position |

| The prosthesis is moistened | With the individual looking up, the lower lid is gently drawn down. The lower lid is depressed with an index finger to raise the edge of the prosthesis |

| With the individual looking up, the prosthesis is inserted under the upper lid | With the individual looking down, the prosthesis is expelled from beneath the upper lid |

| The lower lid is pulled down until the prosthesis slips in behind the lid to rest in the lower fornix | The prosthesis is grasped between the thumb and index finger, and lifted out |

| The individual blinks gently, and a check is made to ensure correct position of the prosthesis |

Eye surgery

Laser eye surgery is commonly performed to correct refractive errors such as myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism. A laser is used to permanently change the shape of the cornea, and in most cases the need to use corrective lenses is reduced or eliminated. Several surgical procedures are now available:

• Laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK)

• Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK)

These procedures reshape the cornea using laser technology to remove a thin layer of epithelial cells or to shrink and reshape the cornea. Candidates for laser vision-correction should be in good health and must have adequate corneal thickness to ensure that the risk of perforation does not occur.

Following surgery, clients may experience a temporary loss of contrast sharpness (images do not appear crisp as with corrective lenses), over- or under-correction of visual acuity, dry eyes or temporarily decreased night vision with halos, glare and starbursts (LeMone et al 2011).

Corneal transplant: Once the cornea has become scarred and opaque, no treatment can restore clarity. The first successful corneal transplant was performed in 1906. Corneas are harvested from cadavers of uninfected adults who were under the age of 65 and who die as a result of acute trauma or illness. Corneal transplantation is usually an elective procedure, although emergency transplantation may be required for perforation of the cornea (LeMone et al 2011).

DISORDERS OF THE EAR

Factors affecting sensory function

Normal function of the ear can be altered by a variety of pathophysiological factors including those that are congenital, degenerative, infectious, obstructive, neoplastic or traumatic.

Congenital factors

Congenital alteration, which may be either hereditary or acquired, include structural malformations that can lead to hearing loss or deafness, disorders resulting from maternal infection during pregnancy or trauma incurred during pregnancy or delivery or before maturity.

Degenerative factors

Degenerative changes in the bones and joints of the ossicles can result in conductive hearing loss, while narrowing of blood vessels to the inner ear can result in tinnitus, vertigo or hearing loss. Gradual sensorineural hearing loss can result from a decrease in the number of hair cells and nerve fibres in the auditory system as a consequence of the ageing process.

Infectious factors

Microorganisms can cause external, middle or inner ear infections, all of which result in pain and varying degrees of conductive hearing loss.

Obstructive factors

Obstruction of the auditory system, which may result in conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, includes impacted cerumen, foreign bodies, oedema and neoplasms. An obstruction can impede the passage of sound waves causing an imbalance of pressure on either side of the tympanic membrane or it may disrupt the transmission of sound to the inner ear.

Neoplastic factors

Neoplasms, which may be benign or malignant, can affect the external middle or inner ear. The effects of a neoplasm include pain, discharge, vertigo, tinnitus and hearing loss.

Traumatic factors

Trauma to the external ear includes bruising, lacerations and frostbite. Trauma to the head can result in fractures of the temporal bone, dislocation of the ossicles, rupture of the tympanic membrane and damage to the auditory nerve. Trauma can lead to vertigo, tinnitus, nystagmus, pain, bleeding and hearing loss. Hearing loss can also result from sudden exposure to a loud explosive sound or from continued exposure to loud noise.

Major manifestations of ear disorders

The major manifestations of ear disorders are pain, discharge, tinnitus, vertigo, nystagmus and hearing loss.

Pain

Earache (otalgia) is a common manifestation of many ear disorders. Middle ear pain associated with otitis media is often described as deep seated and throbbing. If the external ear is infected and inflamed, the client may experience pain and tenderness. Earache may also be referred from other parts of the body via various cervical or cranial nerves, as occurs with tonsillitis.

Discharge

Discharge from the ear (otorrhoea) is generally associated with infections of the middle ear. Purulent or haemo-purulent discharge may drain from the middle ear through a perforated tympanic membrane. Otitis externa may be accompanied by profuse discharge and irritation of the pinna.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus, which may be constant or intermittent, describes a noise in the inner ear. Noises such as ringing, buzzing, hissing or roaring are due to irritation of hair cells in the organ of Corti. Causes include pressure from cerumen on the tympanic membrane, pharyngotympanic tube obstruction, otitis media, otosclerosis, Ménière’s syndrome and tumours.

Vertigo

Vertigo is a sensation of spinning. The person may feel as if their head is spinning or as if the room is spinning around them. Causes of vertigo include trauma, tumours, inflammation, degeneration of the maculae in the inner ear, Ménière’s syndrome and pharyngotympanic tube obstruction.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is involuntary rhythmic movements of the eyes. The movements may be horizontal, vertical, rotary or mixed. Jerking nystagmus, characterised by faster movements in one direction than the opposite direction, may be a manifestation of certain disorders of the inner ear, although it can be caused by other factors such as neurological disorders. Nystagmus may also be induced by introducing cold or warm water into the external auditory canal.

Hearing loss

Impaired hearing or deafness may be conductive, sensorineural or a combination of both these types.

Conductive hearing loss results from disturbances of the sound transmission mechanism of the external or middle ear, which prevents sound waves from reaching the inner ear. Conductive hearing loss or deafness can result from impacted cerumen, foreign body in the ear canal, middle ear infection, ruptured tympanic membrane, otosclerosis, pharyngotympanic tube obstruction, neoplasms or barotraumas (injury due to pressure).

Sensorineural (perceptive or nerve) hearing loss results from disturbances of the inner ear neural structures, or nerve pathways leading to the brainstem. Sensorineural hearing loss or deafness can result from hereditary or de novo genetic factors, acoustic trauma, infection, neoplasms such as acoustic neuroma, advanced otosclerosis, haemorrhage or thrombosis of the cochlear vessels and Ménière’s syndrome.

Mixed hearing loss combines aspects of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

Specific disorders of the ear

Disorders of the ear and auditory system may be classified as congenital, degenerative, infectious, neoplastic, traumatic or resulting from multiple causes.

Congenital disorders

Congenital disorders may be caused by a genetic defect or may result from prenatal trauma or toxicity. Some of the disorders affect the cosmetic appearance only, while others result in varying degrees of hearing loss. Congenital disorders include partial or total absence of the external ear (auricle), protruding ears, fused or absent ossicles and malformation of the cochlea.

Degenerative disorders