CHAPTER 43 Maternal and newborn care

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to:

• Describe the physiology of pregnancy

• Describe the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy

• Discuss the care of the pregnant woman during the pre/antenatal period

• Explain the postnatal care of the woman

• Identify activities that should be included in a daily care plan for a normal newborn

Maternity nursing involves the care of a woman during her pregnancy and labour, and the care of both the woman and her baby during and after birth. Although midwifery is a specialised profession, requiring the learner midwife to undertake a separate educational program, the nurse may be required to assist in the provision of maternity care. It is therefore important that the nurse has a basic knowledge of human growth and development, the processes of normal pregnancy and labour and an understanding of the immediate and subsequent care of the mother and the newborn infant. The actual work and scope of practice of the individual enrolled nurse is influenced by the employment setting, their level of competency and employer policy requirements.

When they told me it was time to push, I was so tired, but so ready to see my baby. It felt like I had been in labour forever. It was worth it, though, when they placed her up onto my chest and my partner was able to cut the cord. She was beautiful.

The birth of a baby follows a woman’s pregnancy and the process of labour. The first part of this chapter focuses on the physiology of pregnancy and the indicators and methods of confirming pregnancy and pregnancy care, which includes preparing for the birth. Later, the four stages of labour, and nursing measures for mother and baby during the postnatal period, are explained.

PREGNANCY

Pregnancy (the gestational process) comprises the growth and development, within a woman, of a new individual from conception to birth. The average duration of pregnancy is 266 days after fertilisation of the ovum, or 40 weeks from the first day of the last normal menstrual period.

Physiological changes

Pregnancy, which is a normal physiological function, produces changes in almost all the mother’s body systems. Most of these changes are temporary and most are the result of hormone actions. These changes prepare the mother’s body to protect the developing embryo and fetus, provide for the demands of the fetus and prepare to feed the baby when it is born. Profound endocrine changes occur that are essential for maintaining pregnancy, normal fetal growth and postpartum recovery. The hormonal factors involved in pregnancy are listed in Table 43.1.

Table 43.1 Hormonal factors in pregnancy

| Source | Hormone | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Ovary | Oestrogens and progesterone during the first few weeks of pregnancy | Oestrogens influence: |

| Placenta | Oestrogens and progesterone when the placenta is fully developed | |

| Placental lactogenic hormone | Promotes growth, stimulates development of the breasts and plays a role in maternal fat metabolism | |

| Relaxin | Has a relaxant effect, especially on connective tissue | |

| Pituitary | Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | Stimulates release of thyroxine to maintain increased metabolism |

| Oxytocin | Contraction of the uterus (at the end of pregnancy). Secretion of milk (after birth) | |

| Prolactin | Initiates and sustains lactation (after baby is born) | |

| Parathyroids | Parathormone | Maintains normal calcium ion concentration |

| Adrenals | Adrenal hormones (e.g. glucocorticoids and aldosterone) | Increased secretion maintains increased metabolism |

Pregnancy can be divided into three periods called trimesters, each lasting about 3 months (Blackburn 2007; Davidson et al 2010). The first trimester comprises the embryonic phase. The uterus continues to be a pelvic organ. Towards the end of the first trimester it is possible to record fetal heart tones by fetascope or ultrasound. The second trimester comprises the fetal phase of development. During this phase the uterus becomes an abdominal organ. A protective coating called vernix caseosa covers the fetus. Lanugo, fine downy hair, covers the body. At the end of the second trimester, the fetus resembles a small baby. During the last 3 months of pregnancy the fetus grows to approximately 50 cm and 3.2 to 3.4 kg (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The skin thickens, subcutaneous fat makes the fetus appear rounder and the lanugo begins to disappear. The normal fetus at this stage is ready to make the transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life

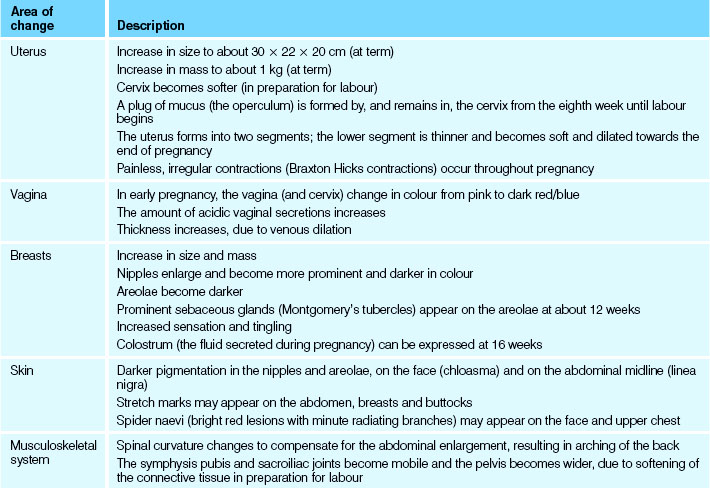

Adaptation to pregnancy involves all of a woman’s body systems. The mother’s physical response is assessed in relation to normal expected alterations. Women can experience varying signs that can signify pregnancy. The maternal physiological changes during pregnancy are listed in Table 43.2.

Table 43.2 Physiological changes in pregnancy

Psychological changes

During pregnancy a woman’s psychological status may alter; for example, she may experience anxiety and emotional lability. The pregnant woman’s psychological status depends on many factors, including her basic personality, whether the pregnancy was planned and is desired, the strength of her social and family support systems and her self-concept.

Confirmation of pregnancy

The signs of pregnancy are divided into three general groups: possible, probable and positive.

Possible indicators of pregnancy

Signs of possible pregnancy are those from which a definite diagnosis of pregnancy cannot be confirmed. Signs and symptoms during this stage can often be caused by other conditions. The indications of possible pregnancy are:

• Breast enlargement and tenderness

• Quickening (Perry et al 2010).

Amenorrhoea (the cessation of menses) in a sexually active healthy woman is often the first indication of pregnancy. However, other factors may cause amenorrhoea, such as eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia), excessive exercise or changes in metabolism and endocrine function.

The symptoms of nausea and vomiting, which can occur at any time of the day, are often referred to as morning sickness. Nausea often occurs between 6 and 14 weeks gestation and is believed to be a result of large quantities of placental hormones (progesterone, oestrogen, human chorionic gonadotrophin [hCG] and human placental lactogen).

Breast enlargement and tenderness are a result of the placental hormones stimulating the breast ductal system in preparation for breastfeeding. Some women experience similar symptoms premenstrually and pregnancy is often overlooked for this reason.

Increased pigmentation of the skin occurs over the face (chloasma), breasts (darkening of the areolae) and abdomen (linea nigra—a dark line extending from the umbilicus to the symphysis pubis).

Frequency of micturition occurs at the start of pregnancy and then again in the third trimester. In the first trimester the enlarging uterus competes for space in the pelvic cavity and exerts pressure on the urinary bladder. In the later stage of pregnancy the descending fetal part of the uterus moves into the pelvic cavity in preparation for birth.

Quickening is the result of fetal movement and is first perceived at 16–20 weeks gestation. The sensation is felt by the mother and described as gentle fluttering in the lower abdomen (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Leifer 2007).

Probable indicators of pregnancy

Abdominal uterine enlargement, the presence of Braxton Hicks contractions and a positive pregnancy test are indicators that a woman is probably pregnant. However, on very rare occasions there may be other conditions or factors (uterine tumours, medications or premature menopause) that cause these events.

Abdominal and uterine enlargement occurs around the 12th week of pregnancy. At this stage the fundus of the uterus can be located just above the symphysis pubis, and extends to the umbilicus between weeks 20 and 22.

Braxton Hicks contractions are irregular, painless uterine contractions that first occur in the second trimester. They are more pronounced in multiparas (women who have had more than one child) and can be mistaken for labour contractions.

A pregnancy test may be performed after the first missed menstrual cycle. Pregnancy tests use maternal blood or urine to determine the presence of the placental hormone human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). A positive result from a pregnancy test is considered an indicator of probable pregnancy. Provided that they are carried out precisely according to the given instructions, home pregnancy tests based on the amount of hCG in the urine are capable of greater than 97% accuracy.

Professional pregnancy tests based on urine or blood serum are even more reliably accurate. The most highly reliable test is the radioimmunoassay (RIA), a technique in radiology that can accurately identify pregnancy as early as 1 week after ovulation. While attributed with high levels of accuracy, pregnancy tests cannot be classed as absolutely certain indicators because there are factors that may interfere with the reliability of test results. These factors include premature menopause, the effects of taking some particular medications (anticonvulsants or anti-anxiety drugs) and the presence of a malignant tumour or haematuria (Leifer 2007).

Positive indicators of pregnancy

The most positive sign of pregnancy is a growing and developing baby (Perry et al 2010). The fetal heartbeat can be detected as early as 10 weeks gestation using equipment such as a tocograph pelvic ultrasound or Doppler device. This scan enables (allows) the examiner to detect and record the fetal heart rate and therefore confirm pregnancy. The Doppler can be used to listen to the baby’s heart rate from 18–20 weeks gestation onwards.

Fetal body parts can be felt by an educated examiner (medical officer, obstetrician or midwife) from the second trimester onwards. This gives the examiner an indication of the position of the fetus, which is vital during the third trimester when discussing birthing options.

Estimated date of delivery

The date when the baby is due (confinement date) may be calculated by dates or using ultrasound. Calculation by dates to determine the estimated due date is made by ascertaining the first day of the last known menstrual period and adding 9 months and 7 days. Calculation by ultrasound is made by using height frequency, short wavelength and soundwave reflections to visualise the size of the fetus.

Estimated date of delivery (EDD) may be calculated by using the date of the LNMP, an early dating ultrasound or a scan at 18–20 weeks. The EDD according to the LNMP (last normal menstrual period) is used if:

• The LNMP is reliable (the woman is certain of the first day of LNMP and she has a regular 28 or 35* day cycle)

• The early dating scan calculates the EDD to be within 5 days of a reliable LNMP due date.

The EDD according to the early dating ultrasound is used if:

• The LNMP is unreliable and/or

• The early dating scan calculates the EDD outside 5 days of a reliable LNMP due date

• Ultrasound performed prior to 14 weeks is more accurate for estimating gestation.

The 18–20-week scan should be used if:

• There was no dating scan performed and

• The LNMP is unreliable and/or

• The 18–20-week scan calculates the EDD outside 10 days of a reliable LNMP due date.

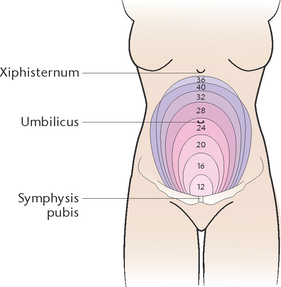

Fundal height is used to indirectly measure fetal growth in relation to gestational age. Fundal height, measured in centimetres, should equal the number of weeks of gestation plus or minus 2 cm (The Royal Women’s Hospital 2006).

Calculation by assessing the fundal height (Fig 43.1) is made by measuring the height of the uterine fundus from the symphysis pubis. As the uterus enlarges steadily and predictably, the date of confinement can be determined reasonably accurately. Fundal height is used to indirectly measure fetal growth in relation to gestational age. Fundal height, measured in centimetres, should equal the number of weeks of gestation plus or minus 2 cm.

Minor discomforts associated with pregnancy

The pregnant woman may experience one or a variety of minor disorders or discomforts, many of which are the result of increased secretion of hormones or pressure from the uterus and its contents on other body structures. Table 43.3 lists the potential discomforts and outlines guidelines that can be used to increase women’s levels of comfort.

Table 43.3 Client education: management of minor discomforts during pregnancy

| Discomfort | Management guidelines |

|---|---|

| Morning sickness | |

| Indigestion | |

| Constipation | |

| Fainting | |

| Backache | |

| Varicose veins | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Leg muscle cramps | |

| Haemorrhoids |

PRENATAL CARE AND PREPARATION

Prenatal (or antenatal) means before birth. The aims of prenatal care are to:

• Promote a healthy pregnancy and normal labour

• Promote the birth of a healthy, living baby

The initial consultation

The woman’s initial consultation concerning her pregnancy may be with her general practitioner, obstetrician or possibly, especially if she resides in a rural or remote area, a midwife. The first consultation involves obtaining a comprehensive health and social history, thorough physical examination, pelvic examination and discussion on selecting where the woman wishes to give birth (Perry et al 2010).

The physical examination includes checking the blood pressure, heart, lungs, palpating the abdomen and breasts and assessing weight, height, body build and skin colour. Samples of urine and blood are obtained and tested. Urine is tested to diagnose pregnancy and to detect the presence of abnormalities; for example, glucose or protein. Blood is tested to determine blood group and Rh factor status, haemoglobin level and the presence of rubella antibodies. It may also be tested to exclude certain disorders such as blood-borne viruses (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis) and sexually transmitted infections (e.g. syphilis).

The pelvic examination may involve bimanual and speculum examinations to assess uterine size; to observe the cervix, vagina and perineum; and to estimate the pelvic capacity. A cervical smear and/or cervical swabs may be obtained if the woman has not had regular Papanicolaou (Pap) smears or if infection is suspected. This may be delayed until the woman has her 6-week post-birth checkup.

If pregnancy is confirmed, the obstetrician will discuss with the woman possible options regarding the birth. The woman may choose to give birth in a hospital, or in a birthing centre; she may also choose not to continue with the pregnancy (Leifer 2007; Pairman et al 2010).

Prenatal education may be provided by the obstetrician, midwives or childbirth educators. The educational aspects of prenatal care are listed in Table 43.4.

Subsequent consultations

The frequency with which subsequent visits occur depends on the obstetrician and the needs of the woman, but the usual practice is to schedule visits every 4 weeks until 28 weeks, then every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, then weekly until birth.

The standard antenatal check provides the basis for routine biophysical screening, assessment, referral and education (Pairman et al 2010). Blood tests or other investigations, for example ultrasonic examination, may be performed as part of routine care or when other tests or physical symptoms indicate there is a need.

LABOUR

Labour is the process in which the woman has uterine contractions to assist with her baby’s birth. The process also includes the vaginal birth of the placenta and membranes. Normal labour occurs spontaneously at about 40 weeks of pregnancy and lasts for up to 24 hours after onset. Factors that cause the spontaneous onset of normal labour include changes in hormonal levels, uterine distension, fetal pressure and a sudden reduction of intrauterine pressure when the membranes rupture (Davidson et al 2010; Leifer 2007). Labour is divided into four stages; Table 43.5 lists the characteristics of each stage. During labour the uterus contracts rhythmically to dilate and efface (take up) the cervix and push the fetus through the birth canal. After the baby is born the uterus continues contracting to aid in birth of the placenta and membranes.

Labour and childbirth are normal events, accompanied by a variety of emotions, such as excitement, fear, anxiety and anticipation. As the management of, and attitudes towards, labour and birth differ widely among different cultures, expectant women, obstetricians and midwives, practices are adjusted according to individual needs, knowledge and experience. The following section addresses the general aspects of care and support throughout labour and birth.

The first stage

Latent stage

Latent stage refers to a period of time, not necessarily continuous, when the woman has painful contractions with some cervical change, including cervical effacement and dilatation up to 4 cm.

Active or established first stage

In this stage there are regular, painful contractions associated with progressive cervical dilatation from 4 cm.

Care during the first stage involves monitoring the progress of labour, monitoring the condition of the woman and unborn baby (fetus) and promoting physical and psychological comfort. Progress of labour is monitored by assessing the strength, frequency and duration of contractions, by palpating the abdomen to assess the position and descent of the fetus and by performing vaginal examinations only when deemed necessary to assess the degree of cervical dilatation and the position of the presenting part of the fetus. The condition of the woman and her response to labour are monitored by checking her vital signs, by observing urinary output and testing the urine for the presence of protein and ketones; and by observing her for the manifestations of fatigue, discomfort or pain.

The health of the unborn baby is monitored by assessing the fetal heart. As the fetal heart rate and rhythm is the main indicator of the baby’s health, the heartbeat is regularly assessed during labour. The heart rate should remain between 120 and 160 beats per minute and the beat should remain strong and regular. Assessment may be performed by listening to the heart through a stethoscope placed on the woman’s abdomen or by using a fetal monitoring device, such as electronic fetal monitoring, known as a cardiotocograph. Fetal monitoring devices provide an audible and/or visual record of the fetal heartbeat (Pairman et al 2010; Perry et al 2010).

Another way that the condition of the fetus is assessed is by observing the passage of ‘liquor’ draining from the woman’s vagina. Normally the liquor remains clear and straw coloured, while green-tinged liquor indicates the presence of meconium. The passage of meconium (the dark green tarry substance formed in the fetal bowel) by the fetus while still in the uterus indicates that the fetus is physically distressed because of a period of fetal oxygen deprivation.

Promoting comfort

Unless there are factors that may compromise the condition of the woman or her baby, the woman is encouraged to do whatever will contribute to her comfort. She may choose to walk around or may prefer to sit or lie down. The woman may like to engage in some form of activity, such as reading, watching television or listening to music. Some women find that frequent warm showers enhance their comfort, while others may prefer to have their partner or the midwife massage their abdomen and back.

During the first stage the woman may need to be encouraged and supported to use the relaxation techniques learnt in prenatal classes. She is encouraged to empty her bladder at least every 2 hours, as a full bladder can inhibit uterine action. The woman is also encouraged to consume frequent small amounts of clear fluids (e.g. 75 mL/h). Because the absorption of food is slowed down during labour and because there is the possibility that a general anaesthetic may be necessary, solid food is generally restricted during labour. The input and output of fluids are monitored to assess for the manifestations of the woman becoming dehydrated. Because the process of labour requires the expenditure of large amounts of energy, the woman may become fatigued. Fatigue is minimised by encouraging rest and relaxation and by relieving discomfort of pain.

Strong contractions may cause considerable discomfort, and the measures used to minimise and relieve discomfort will vary according to the needs and choices of each woman. Measures to relieve discomfort aim to reduce pain and tension without causing any harmful effects to the woman or baby. Measures include practising relaxation techniques, assuming the most comfortable position, back and abdominal massage, using music as a distraction and medications. Medications such as analgesics may be prescribed. Any medication administered must not cause harmful effects to the baby or retard the progress of labour. Analgesic medications may be administered by inhalation (e.g. nitrous oxide and oxygen), intramuscular injection (e.g. pethidine) or intrathecal injection of local anaesthetic solution into the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord, from which the nerves supplying the uterus or cervix arise (epidural analgesia).

Throughout the first stage the midwife should provide emotional support and encouragement, and do all that she can to ensure that the labour is not a distressing experience (Leifer 2007; Perry et al 2010).

The second stage

Traditionally, and currently, the definition of second stage labour commencement is described as when the cervix is fully dilated. The duration of second stage is therefore based on when the woman is diagnosed as being fully dilated by the midwifery or medical staff.

Although it may be accompanied by some anxiety, the second stage of labour signals the imminent birth of the baby. It concludes with the actual birth of the baby (Leifer 2007). Progress of labour and the condition of the unborn baby are monitored as in the first stage, but at more frequent intervals. During contractions the midwife and/or partner should offer encouragement. As the fetal head reaches the pelvic floor, most women experience the urge to push (Roberts & Hanson 2007). Automatically the woman will begin to exert pressure downwards by contracting her abdominal muscles while relaxing her pelvic floor. This bearing-down reflex is an involuntary reflex response to the pressure of the presenting part on stretch receptors of pelvic muscles. The midwife then encourages the woman to push when the urge to push is felt, rather than giving a long prolonged push on command.

Between contractions the woman may wish to have her lower back massaged, and should be encouraged to rest. Small sips of fluid or ice chips should be offered to moisten her mouth, and the woman may wish to have her face wiped at frequent intervals. Labour is often hard and tiring work. The woman is encouraged to adopt the position in which she feels the most comfortable for the birth. Physical support may be needed to maintain the woman in a suitable position. She may wish to have her back supported by pillows, depending upon the position she adopts (see Clinical Scenario Box 43.1).

Clinical Scenario Box 43.1

Mandy and Tom

Mandy had been in labour for 12 hours and was physically and emotionally exhausted. We both had been awake for more than 24 hours. I felt helpless and thought that there was nothing I could do. The midwife encouraged me to continue massaging Mandy’s back and thighs. Sometimes Mandy told me to stop and then to start massaging again. I kept thinking I must be doing something wrong. The midwife explained that this was normal behaviour and a woman’s needs change frequently towards the end of the first stage. I remembered from our antenatal classes that this meant that Mandy must nearly be fully dilated and would start pushing soon. I reminded Mandy of this and together we seemed to find extra energy, knowing that we would soon meet our beautiful baby.

The birth

The birth of the baby may take place with the mother lying down, standing, squatting or kneeling. Some maternity units and birth centres are equipped to accommodate the woman and her partner in a home-like environment, with some women choosing to have a water birth. During birth of the baby the obstetrician or midwife assists by gently controlling the emergence of the head to prevent perineal damage. In some instances an episiotomy (incision into the perineum to enlarge the vaginal opening) may be necessary. Sometimes the application of obstetric forceps to the fetal head may be necessary to assist in its passage through the birth canal.

During an uncomplicated birth, after the baby’s head has cleared the vagina, the shoulders and the rest of the baby’s body are gently pushed out. Immediately after birth, provided that everything is normal and as expected, the baby is generally placed on the mother’s abdomen. The umbilical cord is clamped in two places and cut between the clamps (Davidson et al 2010; Leifer 2007). Although about 95% of babies present head first, a small number are born buttocks first (breech presentation). A caesarean birth is the birth of the baby through a surgical abdominal incision. A caesarean section may be indicated for a variety of reasons, including maternal or fetal distress or failure to progress in labour.

The second stage is completed when the baby is born, which is an emotional time for everyone involved in the birth process. The baby is placed on the mother’s abdomen, and both she and her partner can look at and caress their infant. The obstetrician or midwife remains nearby so that the condition of both mother and baby can be monitored. It may be necessary to aspirate mucus from the baby’s mouth to prevent inhalation. The midwife encourages the mother to initiate skin-to-skin contact with her baby: the baby is placed at her breast and encouraged to suckle. This is thought to help establish the attachment process between mother and baby, and suckling promotes uterine contractions, necessary for expulsion of the placenta.

The third stage

During this stage the placenta and membranes are expelled. In most settings, oxytocic medications such as ergometrine or syntometrine are given to promote uterine contraction and reduce the risk of postpartum haemorrhage. After expulsion of the placenta the woman’s vulva and vagina are swabbed clean so that the areas can be inspected for any lacerations or tears. Any laceration or episiotomy is repaired. A sterile vulval pad is applied to collect the vaginal discharge. The woman is assessed for signs of haemorrhage and for any adverse effects of the birth. To assist with involution (decrease in size of the uterus), the midwife will massage the uterine fundus through the abdominal wall to promote contraction and retraction. The placenta and membranes are assessed to see if they are normal and complete. If they are incomplete, there may be fragments retained in the uterus, preventing uterine contraction and providing a focus for infection (Davidson et al 2010; Leifer 2007).

The fourth stage

The fourth stage of labour is the first 1–4 hours after birth of the placenta, or until the mother has regained physiological stability (Leifer 2007). During this time the midwife’s role includes monitoring the mother for her emotional health and wellbeing, levels of pain, bladder function, blood loss and recovery from anaesthesia. The midwife also provides the initial care for the new baby. The role also includes providing emotional support that may be necessary for the mother, family or significant others. It should be acknowledged that not all mothers will have partners, not all will have the family support they may desire and this may be a time when particular sensitivity is required.

Cultural influences on birthing practices

The needs and wishes of the woman during pregnancy, labour and the postnatal period may be influenced by her cultural background. This may be very different to that of the midwife, but must be understood and respected. Australia and New Zealand are multicultural societies, and providing for the many different cultural preferences of clients requires flexibility on the part of midwives and nurses. There are differing cultural beliefs of significant importance to clients concerning:

• Who should be present during the labour and birth

• Showering or bathing after birth

• What is considered an appropriate diet for a new mother

• How long and how much a woman should rest after the birth

• What should happen to the baby, e.g. when breastfeeding should begin, what clothing and adornments should be used

• Specific rituals and practices that promote healing of the body

Cultural attitudes vary enormously. For example, in over 50 known cultures, including Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean and Mexican, it is not the cultural norm for women to give infants colostrum, and breastfeeding is delayed until the milk has come in (Crisp & Taylor 2009). In most South-east Asian cultures it is seen as essential that the woman is not exposed to anything cold after the birth, as this is believed to risk the onset of arthritis and bladder problems. Many people of Vietnamese culture believe that showering and washing the hair too soon after giving birth leads to recurring headaches and hair dropping out quickly in old age. Many people in Hmong culture believe that when a person dies they must collect the person’s placenta (termed ‘black jacket’) and put it on the deceased so they can be allowed entry into heaven. For this reason a Hmong woman may be very anxious about what is happening to her placenta and may request that it be given to the family for burial at the woman’s home. Clinical Interest Box 43.1 provides examples of cultural preferences in women who are of Chinese and Samoan descent.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.1 Cultural preferences in women of Chinese and Samoan descent

Women who are of Chinese descent

Many Chinese people, when they are ill or pregnant, assume a ‘sick role’ in which they depend heavily on others for assistance. This means that some healthcare providers may be seen as uncaring because they encourage independence rather than catering directly to the wishes of the patient.

Pregnancy and especially childbirth are believed to disturb the balance of hot and cold required for good health. Because of this, various dietary and behavioural practices are customary to keep the mother and baby physically healthy including:

• Eating special soups and chicken/chicken broth

• Not eating lamb because of the belief that it may cause the baby to develop epilepsy

• Not eating pineapple because it is believed to cause miscarriage.

Many Chinese people believe that a woman should not cry out or scream during labour.

Women may experience distress if not given a choice between cultural traditions and western practices. Women may prefer sitting or squatting to give birth. Ideally, the labouring woman’s mother or mother-in-law attends childbirth, rather than the father of the child. This practice varies among communities.

Some women may observe a period of confinement after birth, during which they rest, dress warmly, limit showers and eat only foods classed as hot. Staff may need to discuss the option of exercises to avoid deep vein thrombosis while in bed (e.g. bending knees, moving legs).

According to some customs in Guandong and Hong Kong, postpartum women may not eat with other family members for up to 1 month due to the notion of pollution linked to lochial discharge. For the same reason, postpartum women may abstain from sexual relations.

Women are often expected to follow certain traditional practices advocated by older female relatives. However, practical constraints mean that many Chinese women opt for an approach to childrearing which combines practices from both Australian and Chinese culture.

Infants may be over-wrapped and slept in prone position. Many Chinese people believe that infants should not be dressed in used clothing as the baby may take on the characteristics of those that wore the clothes previously. Therefore, the family may bring new clothing for the baby instead of dressing the baby in hospital clothing. Disposable shirts may be acceptable. Infants may be separated from their mother for at least the first 24 hours. This tradition is practised to allow the postpartum woman to rest. The Australian practice of leaving infants with their mother should be discussed with women of Chinese background. Some women believe that if a newborn child is praised, bad spirits will take the infant away or the child will fall ill. Grandmothers, particularly the father’s mother, are often very involved with the new infant and the new mother’s recovery. They should be acknowledged when caring for the mother and during teaching sessions.

Colostrum may be considered stale or dirty and discarded. Staff may need to explain the benefits of colostrum feeding and encourage women to feed their infant. Babies may be fed with boiled rice water or formula instead of colostrum during the first 2 days.

Women who are of Samoan descent

Samoans often view pregnancy as a sickness. Pregnant women are cautioned against being alone in the house or going outside, especially after dark. Samoans believe that a lone pregnant woman can be hexed by evil spirits, causing abnormalities to the unborn child. A pregnant woman should always be accompanied by an elderly woman, even to the toilet. Samoans believe that pregnant women should avoid heavy work which may lead to the displacement of internal organs.

For their first delivery, Samoan women usually return to their mother’s home and after a confinement period, the new family returns home. This should be kept in mind since in Australia, Samoan women may have no parental support. Episiotomy is not considered a part of usual delivery-related procedures. Birth attendants usually perform a cut on the umbilical cord after it has stopped beating. After birth, the baby is massaged with blood from the placental part of the umbilical cord. Health professionals should be aware of this practice.

In Samoa, the placenta is usually expelled by pulling, while the abdomen is massaged. Sometimes the father is asked to apply force to facilitate expulsion. Care should be taken to ensure that the placenta is offered to the new parents. In Samoa the placenta is disposed of in various ways. It may be wrapped in a cloth and buried in the ground by close family members, burned in a hole dug in the ground or thrown into the sea. It may be believed that the newborn is at risk if anything happens to the placenta. In Samoa, after labour, the woman’s abdomen may be firmly bound with cloth to prevent the uterus from ‘falling down’. This remains in place for up to 1 month. After delivery, women traditionally receive abdominal and pelvic floor massage to correct any displacement that may have occurred during labour. They will then bathe. Sometimes, a bowl of steaming water is placed between a woman’s legs, so that the rising steam can cleanse the birth canal. In Australia, Samoan women could be asked if they would like a hot water bottle to replace this procedure.

Once postnatal procedures are complete, a woman may be given a bowl of sago cooked in coconut cream and flavoured with lemon leaves. According to Samoan practice, a woman should rest for a month after her first delivery. After subsequent deliveries, she should rest until the infant’s umbilical cord falls off. The benefits of early physical activity after birth should be discussed with Samoan women in Australia.

Samoan infants are usually bathed immediately after birth. A newborn is usually placed in cold water to make them breathe.

Samoan midwives may recommend that a woman breastfeed immediately after birth; others give boiled water only for up to 5 days. Samoan infants are fed on demand. Breastfeeding is considered to be a contraceptive

When nurses understand the beliefs behind particular cultural practices, the risk of confusion and conflict concerning what the woman chooses to do during and after the birth of her baby is reduced (Pairman et al 2010). However, care should be taken not to generalise about what happens in particular cultures because attitudes, values, beliefs and practices can vary significantly even within each cultural group (see Chs 8 and 9). In addition, the process of assimilation into a new culture may alter traditional beliefs and practices. Clinical Interest Box 43.2 provides examples of traditional birthing practices in the Indigenous populations of Australia and New Zealand.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.2 Cultural beliefs and childbirth of Indigenous people in Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Birth is seen very much as ‘women’s business’ in Aboriginal society. Education has been traditionally undertaken through observation and involvement in the life of the extended family, with elders imparting specific knowledge as required. Traditionally men have not been involved during the pregnancy or the birth and appeared to play a minor role in baby care and childraising.

Much of this is changing as Aboriginal people move in from the bush to town living, and family support systems shrink. Western ideas are being embraced as young Aboriginal people seek inclusion in the wider Australian way of life. Many Aboriginal women now give birth in hospitals, often far from family and friends. The traditional women’s business of childbearing seems to be breaking down in some places, as men accompany their partners during labour and birth in hospitals.

Traditionally Maāori women in Aotearoa enjoyed full control over their birthing processes. With the help of a tohunga (priest), midwives and whānau (family), women controlled conception, abortion, birth and parenting. They followed the strict protocols of karakia (incantations), tapu (spiritual powers) and noa (blessing). Most deliveries were in the squatting or standing position, with support if desired. There was no interference and, if problems arose, the most appropriate tohunga who specialised in that particular situation was called upon to resolve the problem. The placenta was buried by the appropriate person and when the pito (umbilical cord) had fallen off the infant, it too was appropriately buried or planted in a rock crevice or tree.

(Nga Maia; Pairman et al 2010; Queensland Health 2009)

POSTNATAL CARE

The postpartum period is called the puerperium. Sometimes called the fourth trimester of pregnancy, the puerperium begins after childbirth and continues for the following 6 weeks (Davidson et al 2010; Leifer 2007). This is the time during which the changes to the woman’s body brought about by the pregnancy gradually resolve. It is also a time of adjustment to changed responsibilities. Mothers generally return home within days of the birth, so it is important to provide as much help and education as possible before discharge. While this section focuses mostly on care in the birthing centre or hospital, the ongoing needs of the mother, baby and family should be considered so that support can be planned as necessary for the remainder of the puerperium.

After the third stage of labour is completed, the mother’s immediate comfort is promoted by ensuring that any wet or soiled clothing is replaced, and by offering her a drink and snack. She and her partner should be allowed to spend time together with the baby. If the mother is exhausted she may appreciate being left to rest or sleep.

Care of the mother

The degree of care required will depend on a variety of factors, such as where the birth occurred, how long the mother remains in the maternity unit or birth centre, whether the birth was full or preterm, if it was uncomplicated, whether there were multiple births and whether there are any postnatal discomforts or complications. In addition, care must be adapted to meet any specific cultural needs. Postnatal care is directed at promoting the health of both mother and baby. Aspects of care include promoting:

• Freedom from discomfort or pain

• The establishment of lactation and breastfeeding

• The mother’s confidence in caring for her baby (Perry et al 2010).

Assessment is made of the lochia, the vaginal discharge that occurs after birth. Lochia consists of blood and broken-down endometrium and is discharged for up to 3–4 weeks after birth. At first it is bright red in colour, then becomes pink and ultimately presents as a colourless or white discharge. Lochia should not have an offensive odour or contain any blood clots; the presence of either indicates the possibility that products of conception have been retained in the uterus. Observe for character, colour, odour and presence of clots. Clinical Interest Box 43.3 outlines the assessment of lochia.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.3 Changes in lochia that cause concern

• Inadequate uterine contractions that allow bleeding from vessels at the placental site.

• Inadequate uterine contractions; retained placental fragments; infection

Perineal care involves daily showering to cleanse the area, and frequent changing of vulval pads. If a perineal tear occurred or if an episiotomy was performed, care may be needed to reduce discomfort and prevent infection around the area. Local care may involve the application of cold packs to the area, or sitz baths to which salt has been added. A soft cushion to sit on or lying on the side to feed may help to relieve perineal soreness, and analgesic medications such as paracetamol may be prescribed. Observe for haematoma and oedema.

Fundal height is assessed by the midwife and documented each day to monitor involution of the uterus. It may be necessary to massage the fundus to promote uterine contraction. The height of the fundus decreases by about 1 cm each day until, by the 11th or 12th day it can no longer be palpated abdominally. The firmness, height and location are evaluated.

The breasts and nipples are assessed each day for any red areas, oedema, cracking or bleeding. Palpation of each breast detects any areas of hardness, which may indicate blocked milk ducts.

Vital signs are assessed with abnormalities reported. The extremities are evaluated for signs of thrombophlebitis. The bladder is observed for fullness, output, burning and pain. The bowels are assessed to determine passage of flatus and bowel sounds and for defecation.

Postnatal exercises are started on the first day. They are designed to strengthen the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles. An instruction sheet illustrating the exercises to be performed is generally given to the mother and explained by the midwife.

Evaluation of the woman’s emotional status involves observing family interaction and support and any signs of a depressive state. The woman should also be observed for interest in the newborn, eye contact, touch contact and the ability to respond to the infant’s cries (Davidson et al 2010).

A balanced diet, which provides adequate nutrients and fibre, is advised. In the hospital setting a dietitian may be responsible for accommodating special cultural needs in relation to diet but often family members will want to bring meals from home for the new mother. If the woman is breastfeeding, she should consume an extra 2500–4000 kJ/day above the requirements of pregnancy. This provides the extra energy required to produce milk. In addition to nutritional requirements, the lactating mother requires 3 L of fluid a day.

The lactating mother is advised to avoid consuming foods that may effect her lactation and can upset the baby. This is very individual and may include highly spiced foods. The woman who wishes to breastfeed should also be advised of the substances known to be excreted in the breast milk. Substances that should be avoided or taken sparingly include:

Minor postnatal discomforts

Some discomforts are associated with the postnatal period. These include after-pains, constipation, difficulty with passing urine and engorged breasts. After-pains are cramps that may occur for a few days after birth, as the uterine muscles contract during the process of involution. Mild pain-relief medication may be prescribed.

Constipation may result from inadequate fibre or fluid intake. The woman may also be afraid to go to the toilet post-birth as it may increase her levels of pain and discomfort. Increasing fibre in the diet and maintaining a high fluid intake is important and, if necessary, a stool-softening medication may be prescribed. Analgesia may also be given prior to the woman going to the toilet.

Difficulty in voiding may be experienced initially because of loss of bladder tone, bruising of the urethra or perineal soreness. Some women may find that voiding in a bowl or bath of warm water eases the soreness. If the woman finds that this helps, she should be advised, as a precaution against infection, to wash the perineal area gently after voiding.

Engorged breasts may occur a few days after the birth because of increased blood supply to the breasts in beginning lactation. The breasts may become full, distended, hard and uncomfortable. The midwife should advise mothers that this is not unusual and that wearing a supportive nursing bra, even during the night, will help, provided that it is not too tight. Breastfeeding the baby at frequent intervals (2–3 hours if necessary) helps and promotes engorgement to diminish naturally. A qualified midwife or lactation consultant should be contacted to assist women who are concerned about breast engorgement.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is the optimal method of feeding the baby. While most women will choose to breastfeed, there are others who, for a variety of reasons, will prefer not to. While it is important that a woman be advised of the benefits of breastfeeding, it is also important that she is not made to feel guilty if she chooses to bottle-feed.

Lactation

During pregnancy, placental hormones, oestrogen, progesterone, hCG and placental lactogenic hormone stimulate the development of glandular tissue and ducts in the breasts. Colostrum is the fluid secreted by the breasts during pregnancy and during the first few days after birth. It is a thin, yellow serous fluid consisting of water, protein, fat, carbohydrates and immunologically active substances. When the placenta is expelled after birth of the baby, the anterior pituitary gland releases prolactin, which activates the mammary cells to produce and release milk (Davidson et al 2010; Leifer 2007).

Lactation depends on the maintenance of milk production and on the ‘let-down’ reflex, whereby milk is ejected from the breasts. The let-down reflex is stimulated by a neurogenic reflex, with oxytocin released from the pituitary gland in response to suckling, forcing milk out of the alveoli in the breasts. The let-down reflex, which generally occurs a short time after the baby begins to suck on the nipple, can also be stimulated when the mother sees, hears or thinks about her baby. Conversely, the reflex can be inhibited by anxiety, fear or tension.

Breastfeeding has advantages for both the mother and the baby. Breast milk is free from microorganisms, is easily digested, contains all the essential nutrients necessary for the baby’s development and contains immunoglobulins and other substances that protect the infant from some infections while the immune system is underdeveloped. Breastfeeding aids involution of the uterus and is generally emotionally satisfying for the mother. Breastfeeding is also convenient and economical.

Management

The four basic principles to correct attachment are that the:

• Baby must be close to mother and facing her

• Baby’s mouth and mother’s nipple are in alignment

• Mother holds her breast in such a way that the baby can grasp a large mouthful of breast tissue

• Baby’s mouth is gaping wide with tongue forwards and down in order to be able to take a large amount of breast tissue into the mouth.

Attaching the baby

• Supports her breast with her free hand with her fingers well back from the nipple/areola

• Holds baby close enough to maintain chin contact with the breast.

After the mother has latched her baby to her breast, the baby is stimulated to start suckling when it feels the nipple touching the junction of the hard and soft palate.

Indications of good attachment

FEEL—a ‘drawing’ sensation may be felt by the mother. There may be some ‘nipple stretch’ soreness in the first few days (peaking days 3 to 6) of feeding. This usually occurs with the first sucks of the feed and eases after milk transfer is evident. The ‘let-down’ itself may or may not be felt by the mother

LOOK—the baby’s mouth is wide open and the chin is in contact with the breast. The tip of the nose may be touching or free of the breast. Baby’s head is tilted back slightly so that the chin is pushing into the breast

LISTEN—the baby’s swallows may be audible. There should be a change from short ‘suck/suck’ pattern to deeper ‘suck/swallow’ cycle.

Indications of faulty attachment

Indications of faulty attachment include:

• Pain after there has been a letdown of milk indicates trauma is occurring

• Baby is asleep, not suckling early in feed—nipple is not far enough into the mouth to stimulate a suck cycle.

• Mother indicates if pain persists after the baby starts swallowing. If so, the baby needs to be removed and reattached. Also there may be unusual noises during feeds if an inadequate seal is formed by the baby’s mouth with the breast e.g. clicking, lip smacking

• Breast distortion or movement during feeding—nipple slipping in and out of the baby’s mouth causing friction and damage

• Baby’s mouth not wide open—cannot take a big mouthful of breast tissue

• Chin not in contact with the breast—too far away from the mother

• Suckling action—suck/swallow pattern not seen. If there is no milk coming into the baby’s mouth there will be no swallowing

• Dimpling of baby’s cheeks—indicates the baby has only the nipple in his mouth, instead of adequate breast tissue

• Prolonged feeds—more than 40 minutes, baby not content after long feed—has not been able to take sufficient milk to satisfy hunger (The Royal Women’s Hospital 2004).

To detach the baby from the nipple, the mother should place a finger into the side of the baby’s mouth to let air in to break the suction. Gentle detachment helps to prevent the development of sore nipples.

After the feed the baby is checked to ensure that it is clean and comfortable, and should then be placed in its cot without too much handling. The mother should ensure that her nipples are clean and dried. Expressed breast milk is rubbed into the nipple after the feed then allowed to dry, to protect them against soreness or cracking.

The baby is fed when hungry (demand feeding). Each baby is an individual and some may require breastfeeding as frequently as every 2 hours, while others will be content if they are fed every 3–4 hours. The length of time the baby feeds also varies. The baby and mother establish their own feeding routine, and the mother’s milk supply adjusts according to demand.

Breast milk may be expressed, either manually or with a breast pump, if necessary. Expression may be necessary to relieve discomfort if the breasts are overfull, to help stimulate milk production or to put breast milk into a feeding bottle; for example, if the baby requires feeding when the mother is temporarily unavailable. Expressed breast milk can also be provided by the mother if the baby is premature or ill and is unable to feed at the breast.

Breastfeeding difficulties sometimes arise, for a variety of reasons:

• Maternal anxiety or frustration about breastfeeding

• Cracked nipples, which cause pain when the baby sucks

• Inverted nipples, which are difficult for the baby to grasp

• Breast engorgement, which prevents the milk from flowing readily

• Over-abundance of milk, which flows too quickly causing the baby to splutter and perhaps vomit

Management of breastfeeding difficulties depends on the cause, but with time, patience and encouragement, most can be overcome. Organisations such as the Australian Breastfeeding Association and La Leche League New Zealand provide support and advice on how to prevent and deal with breastfeeding difficulties.

Artificial bottle feeding is the method of infant feeding women choose if not breastfeeding their babies. Artificial feeds are generally based on cow’s milk, although other preparations are available, such as soy-based formulas. The formula selected will depend on the needs of the mother and the baby. Some formulas are expensive, others may not be readily available or the baby may require a special formula, such as soy-based or lactose-free. Whichever formula is selected, the mother must know how to make it up, how to store it and how to care for the bottles and teats. This information is given by the midwife during the mother’s stay in hospital.

As a response to the falling breastfeeding initiation and retention rates worldwide, UNICEF/WHO published the 10 Steps to Successful Breastfeeding in the early 1990s (see also Clinical Interest Box 43.4).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.4 Baby Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI)

1. Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all healthcare staff

2. Train all healthcare staff in the skills necessary to implement this policy

3. Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding

4. Place babies in skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately following birth for at least an hour and encourage mothers to recognise when their babies are ready to breastfeed, offering help if needed

5. Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants

6. Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breastmilk, unless medically indicated

7. Practise rooming-in: allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours a day

8. Encourage breastfeeding on demand

9. Give no artificial teats or dummies to breastfeeding infants

10. Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support and refer mothers on discharge from the facility

(BFHI nd)

Clinical Interest Box 43.5 looks at considerations for adolescents who are breastfeeding.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.5 Life span consideration: breastfeeding and the young woman

During adolescence, young women are coming to terms with their body image and sexuality. Both of these issues may conflict with the expectation and role of becoming a mother. Attitudes of the partner and those of her significant support people may have a considerable impact on feeding choice. For breastfeeding to be a realistic choice, activities to help deal with this pressure may be needed.

To maintain breastfeeding, early attention to breastfeeding problems is necessary and local supports are very important. Diet (as with all pregnant women) should be balanced and education towards improving food choices should be part of management strategies by staff.

Community support groups such as the Australian Breastfeeding Association play a valuable role in providing information, counselling and social support for all families. Encouraging mothers to contact these groups can improve the length of time the woman breastfeeds. This is especially important for mothers who do not have a positive, knowledgeable support network available. Genuine emotional support involving comfort, reassurance and praise has resulted in reduced feeding problems, higher exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks and less self-reported milk insufficiency.

Clinical Scenario Box 43.2

Angela, Brett and Alex

I had Alex 2 days ago. I had to have a caesarean delivery, as he was breech. I was worried that I wouldn’t get to bond with him, but as soon as he was delivered they quickly dried him and gave him to me for a cuddle for a few minutes before my husband Brett left with him and the midwife for the ward. I really hoped to be able to breastfeed, so once they told me I had to have a caesarean delivery, I was worried I would not be able to breastfeed so easily. When I told my midwife this, she reassured me that it would be okay and they even brought Alex back down to the recovery area once I was there so that I could try to breastfeed. With the midwives’ help, he went on first go. I couldn’t believe it! We are doing really well, and with help from the midwives, I have been able to get the hang of breastfeeding him. Now that I am up and about we are managing ourselves most of the time, but the midwives are available to help if I need them.

Angela, first time Mum, talking about breastfeeding her infant

Immediate care of the baby

Immediately after the birth the midwife or obstetrician checks that the baby’s airway is clear and that it is breathing normally. Ventilation is initiated in response to high blood carbon dioxide level, stimulating the respiratory centre in the medulla. In the first few breaths, air is drawn in to expand the alveoli in the lungs, thus oxygenating the blood. Because the newborn baby has a limited ability to regulate its body temperature in relation to the environment, care is taken to ensure that it does not become cold.

One minute after birth, and again at 5 minutes, the Apgar score estimation is performed. The Apgar scoring system gives an estimation of the baby’s condition and is an indicator of whether special resuscitation measures are required (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Table 43.6 illustrates the Apgar score chart. A total score of 10 indicates that the infant is in optimal condition; if the score is 6 or less the baby requires immediate attention. A score of 8–10 is normal, a score of 4–7 indicates that the infant’s condition is moderately depressed, while a score of 0–3 indicates a severely depressed condition.

In a healthcare setting such as a hospital or birth centre, an identification band is placed on the baby’s wrist or ankle for identification. This identification procedure must be performed before the baby is removed from the mother’s bed; this is essential to prevent any later confusion about which baby belongs to which mother. The baby is weighed and measured and the information documented (Perry et al 2010). It is recommended that every baby be given an intramuscular injection of vitamin K as a preventive measure against bleeding tendencies (see Clinical Interest Box 43.6).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.6 The role of vitamin K

Vitamin K is needed by humans to cause blood to clot. Without vitamin K small cuts can go on bleeding for a long time, small injuries can cause a lot of bruising and bleeding can occur in many parts of the body, including in the brain, causing a stroke.

Vitamin K is mostly made by bacteria in our gut because humans are unable to make vitamin K themselves.

All newborn babies have low levels of vitamin K. Only a little vitamin K goes through the placenta to the baby, and at birth a baby’s gut is sterile (there are no bacteria in the gut).

After birth there is little vitamin K in breast milk and breastfed babies can be low in vitamin K for several weeks until the gut bacteria start to make it.

Infant formula has added vitamin K, but formula fed babies have very low levels of vitamin K for several days.

It is recommended that all babies are given vitamin K at birth to prevent a bleeding problem called vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB). This bleeding is rare even when babies are not given extra vitamin K, but if it happens it can cause severe harm to a baby, including death or severe brain damage.

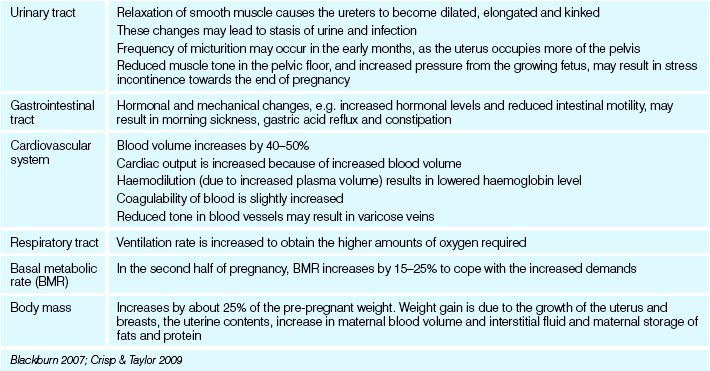

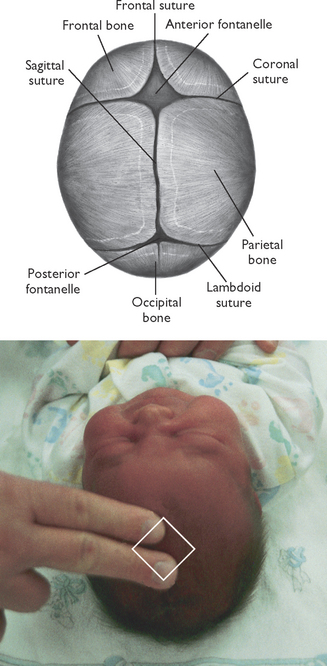

An initial examination of the baby is performed soon after the birth so that any abnormal findings can be acted on as soon as possible. Table 43.7 outlines the findings expected in a normal newborn. The examination assesses the baby’s ventilation, colour, muscle tone, reflexes, movement and the presence of any obvious abnormalities. Later a more thorough examination is performed. See also Figure 43.2.

| Anatomy | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Head | |

| Face | Nose and cheeks may have tiny white spots (milia) |

| Skin | |

| Eyes | |

| Thorax | |

| Abdomen | |

| Limbs | |

| Back | Spine straight, intact, easily flexed |

| Genitalia | |

| Anus | Patent |

Davidson et al 2010; Hockenberry & Wilson 2011

Subsequent care of the baby

Care of the baby in the period immediately after birth is directed towards keeping the baby adequately nourished, clean, warm and free from infection. Careful observation is necessary to detect any problems should they occur. In most healthcare agencies it is common practice for the baby to remain in the same room as the mother. This is termed rooming-in and enables the mother to care for the baby from the beginning (Fig 43.3). The mother gets to know, and gains confidence in caring for, her baby. The midwife is available to offer guidance and encouragement in all aspects of infant care.

Supporting thermoregulation

Maintenance of body temperature is vital. The core temperature of the term newborn is 36.5 to 37.5°C (Blackburn 2007). Hypothermia can cause problems such as hypoglycaemia, as the newborn uses glucose to generate heat and respiratory distress, because the metabolic rate is higher and consumes more oxygen. The first bath is not undertaken until the temperature is between 36.5°C and 37°C.

Obtaining vital signs

Respiratory rate: It is best to obtain this before disturbing the baby. Count the respirations for a minute. The rate can be auscultated with a stethoscope, or a hand can be placed lightly over the abdomen—watch for the rise and fall.

Heart rate: Assess using a stethoscope at the apex of the heart. Count for one minute.

Temperature: Axillary temperatures are most commonly used for the well newborn infant. A thermometer is placed in the axilla, parallel to the chest wall.

Table 43.8 gives the vital sign parameters for a healthy newborn.

Table 43.8 Newborn vital signs

| Vital sign | Normal range |

|---|---|

| Pulse | |

| Respirations | |

| Temperature |

Hygiene and skin care

Healthcare settings establish their own protocols for washing or bathing newborn babies (neonates). The baby is usually washed or bathed daily; a mild pure soap may be used. It is important that the infant’s skin is kept clean and dry, with special attention being paid to the scalp, skin folds and genitals. The buttocks and groin area are washed with plain water or cleansed with a mild lotion each time a wet or soiled nappy is removed. A protective cream or lotion may be applied. Disposable or cloth nappies may be used. The mother may need some advice on how to fold and apply napkins.

If the baby’s fingernails are long, the infant may scratch their face and the scratches may become infected. Mittens may be worn to prevent the infant from scratching.

The bath is a good time to observe the newborn for general wellbeing, activity and behaviour.

Umbilical cord care

Care is aimed at preventing infection. The remnant of the cord is observed every time a napkin is changed, until it has separated and the umbilicus has healed. It is kept clean and dry and observed for any bleeding or signs of infection. It becomes dry and brownish black as it dries. The cord remnant separates from the umbilicus by a process of dry necrosis on days 6–8. The parents are taught to report redness of the area or a moist or a foul smelling cord.

Elimination

After the first day (when the neonate may not urinate for as long as 24 hours) urine is passed about 10–12 times per day. Any unusual colouration or odour must be reported to the medical officer. The baby’s first bowel action consists of meconium, the dark green tarry substance formed in the intestinal tract during intrauterine life. Seventy per cent of newborns pass meconium in the first 12 hours (Davidson et al 2010). When the baby begins to take milk, there is a gradual transition to the normal yellow stools of the neonate. The stools gradually change during the first week. They become loose and are greenish yellow with mucus; this is called transitional stools. Breastfed babies pass stools that are yellow to pale brown, soft and unformed. There may be three to six stools a day. The stools of an artificially fed baby are yellow to pale green, firmer and have a distinctive odour. They are generally fewer in number.

Identification

Wristbands with pre-printed numbers are placed on the infant and the mother. If the infant is separated from the mother, the bands should be checked to ensure they match.

Nutrition

The baby is fed when hungry. Frequent feedings, for example every 2 hours, may be indicated if the baby shows signs of hypoglycaemia. Signs of hypoglycaemia in the newborn include: jitteriness, poor muscle tone, sweating, respiratory difficulty, low temperature, poor suck, high pitched cry, lethargy and seizures. A heel stick is performed when obtaining capillary blood for glucose screening.

Weighing and measuring

In healthcare settings the neonate is generally weighed every second day to assess weight gain or loss. More frequent weighing is indicated if the birth weight was low or if the baby is losing excessive weight. A loss of up to 10% of the birth weight is normal in the first 3–4 days; after this, the baby should begin to gain weight. It is expected that the baby will be back to its birth weight within 10–14 days (Pairman et al 2010).

The length and head circumference are routinely measured. Measurements are noted for gestational age assessment.

Infection control

Infections that are harmless to adults may be fatal to the newborn because of immaturity of their immune system. The baby is protected from infection by normal hygiene practices, the most important aspect of which is washing the hands thoroughly before attending to the baby. Anyone with an infection is advised to limit close contact with the baby.

Temperature control

As the neonate’s temperature-regulating centre is not fully functional, the baby must be protected from extremes of environmental temperature. Conduction, convection and radiation can be used to add heat to the body. This can be achieved by maintaining the room at an even, comfortable temperature, dressing the baby in suitable clothes and wrapping the infant in warm lightweight rugs.

Screening tests

Newborn screening refers to the process in which babies are given a simple blood test a few days after birth to see if they have a rare genetic or metabolic condition. The conditions tested for include phenylketonuria (PKU), congenital hypothyroidism, cystic fibrosis (CF), galactosaemia and a number of other extremely rare conditions. Some of these conditions can result in physical and/or intellectual problems if not treated promptly, and are often referred to as inborn errors of metabolism (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Pairman et al 2010).

Newborn screening (NBS) is a publicly funded system for testing newborn babies’ blood for about 30 rare conditions. All newborn babies are offered screening in Australia and New Zealand.

After the dried blood has been tested, it will be stored in the laboratory for varying periods in different states of Australia and in New Zealand.

Neonatal disorders

Only brief mentions of some of the disorders that can affect neonates are included here. For detailed information, the nurse should refer to a current paediatric text. Disorders may be minor and temporary, major and permanent or life threatening. They include:

Clinical Interest Box 43.7 outlines the procedure for assessing the newborn for jaundice. It describes Kramer’s Rule (Kramer 1969). This rule is based on the way the jaundice will tend to ‘migrate’ down the baby’s body, as the bilirubin levels rise. In essence, the baby’s body is categorised into 5 zones with an estimated bilirubin level for each zone. If the jaundice is believed to be between 200 and 250 μmol/L or more then transcutaneous bilirubinometry and a blood test will be used to estimate the exact bilirubin level.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 43.7 Assessing for jaundice

Observe skin in a well lit room

Press skin with thumb until the skin lightens Observe level of jaundice using Kramer’s Rule

| Zone | Baby’s body area | Approximate bilirubin level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Head and neck | 100 μmol/L |

| 2 | Upper body (chest) | 150 μmol/L |

| 3 | Lower body, below the belly button and upper thighs and arms | 200 μmol/L |

| 4 | Lower legs and forearms | 250 μmol/L |

| 5 | Hands and feet | Above 250 μmol/L |

Summary

The nurse may be required to assist qualified midwives in the care of mothers and their newborn babies. This chapter has briefly outlined the basic knowledge that is essential for the nurse who undertakes this role: the processes of normal pregnancy, labour and birth and the postnatal care of the mother and her baby. It is recommended that nurses gain an understanding of cultural differences in birthing beliefs and practices of the women they care for during and after the birth of their babies. It is also recommended that nurses access current paediatric textbooks to gain or enhance knowledge of neonatal care and disorders that may be encountered in the areas of maternal and child health nursing.

1. You are caring for Alexa, a 30-year-old woman who 3 days ago gave birth to her first baby. She tells you her breasts feel really heavy, tight and uncomfortable and the baby is not feeding properly.

2. With the supervision of the midwife, you are looking after a 20-year-old mother, Kate, and her 4-day-old infant, Ben, who is her first baby. She asks you how often he should feed and how she will know when he has had enough. What do you tell her?

3. You are caring for Hong, a young woman who came to Australia from China a year ago. She gave birth to her first baby earlier today. The midwife has instructed her to get up and go and have a shower. Hong is crying and distressed and tells you that ‘the midwife doesn’t understand’.

1. Describe the physiological changes of pregnancy.

2. What is the Baby Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI)?

3. Immediately after the birth of a baby an assessment is performed on the neonate. What is this called and what does it entail?

4. What are the findings expected in the normal newborn infant?

References and Recommended Reading

Baby Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI). (nd) Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Available: www.babyfriendly.org.au/about-bfhi/ten-steps-to-successful-breastfeeding/.

Blackburn S. Maternal, Fetal and Neonatal Physiology: A Clinical Perspective, 3rd edn. Sydney: WB Saunders, 2007.

Crisp J, Taylor C. Potter & Perry’s Fundamentals of Nursing, 3rd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

Davidson M, London M, Ladewig P. Old’s Maternal-Newborn Nursing and Women’s Health across the Lifespan, 9th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2010.

Goldman C. Vietnamese Cultural Profile. An Initiative of Qld Partners in Culturally Appropriate Care. Diversicare. Online. Available: www.diversicare.com.au/upl_files/file_210.pdf, 2009.

Hockenberry M, Wilson D. Wong’s Nursing Care of Infants and Children, 9th edn., St Louis: Mosby, 2011.

Johnson R, Taylor W. Skills for Midwifery Practice, 3rd edn. Elsevier, London: Churchill Livingstone, 2010.

Kean LH, Chan KL. Routine antenatal management at the booking clinic. Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. 2007;17(3):69–73.

Kramer LI. Advancement of dermal icterus in the jaundiced newborn. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1969;118:454–458.

Leifer G. Maternity Nursing: An Introductory Text, 10th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2007.

Leifer G. Introduction to Maternity & Pediatric Nursing, 6th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2010.

Liamputtong P, Watson L. The meanings and experiences of caesarean birth amongst Cambodian, Lao and Vietnamese immigrant mothers, Australia. Women & Health. 2006;43(3):63–81.

Lowdermilk DL, Perry SE, Cashion K, et al. Maternity & Women’s Health Care, 10th edn. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2012.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Cultural Competency in Health: A guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra: NHMRC, 2005.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Joint Statement and Recommendations on Vitamin K Administration to Newborn Infants to Prevent Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding in Infancy. Online. Available: www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ch39_joint_statement_vitamin_k_2010.pdf, 2010.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. London: RCOG Press, 2003.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Intrapartum Care: Care of Healthy Women and Their Babies during Childbirth. London: RCOG Press, 2007.

Pairman S, Tracy S, Thorogood C, et al. Midwifery: Preparation for Practice, 2nd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2010.

Perry SE, Hockenberry MJ, Lowdermilk D, et al. Maternal Child Nursing Care, 4th edn. St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

Queensland Health. Cultural Dimensions of Pregnancy, Birth and Postnatal Care. Available: www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural/health_workers/Chinese-preg-prof.pdf and www.health.qld.gov.au/multicultural/health_workers/Samoan-preg-prof.pdf, 2009.

Roberts J, Hanson L. Best practices in second stage labor care: maternal bearing down and positioning. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2007;52(3):238–245.

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Pre-pregnancy Counselling and Routine Antenatal Assessment in the Absence of Pregnancy Complications (C-Obs-3). Online. Available: www.ranzcog.edu.au/the-ranzcog/policies-and-guidelines/college-statements/283-pre-pregnancy-counselling-routine-antenatal-assessment-c-obs-3.html, 2009.

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Routine Intrapartum Care in the Absence of Pregnancy Complications (C-Obs-31). Online. Available: www.ranzcog.edu.au/the-ranzcog/policies-and-guidelines/college-statements/427-routine-intrapartum-care-in-the-absence-of-pregnancy-complications-c-obs-31-.html, 2010.

Sherblom Matteson P. Women’s Health During the Childbearing Years. A Community-Based Approach. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

The Royal Women’s Hospital (Victoria). Breastfeeding: Best Practice Guidelines. Online. Available: www.thewomens.org.au/uploads/downloads/HealthProfessionals/CPGs/Breastfeeding_Guidelines_2004.pdf, 2004.

The Royal Women’s Hospital (Victoria). Clinical Practice Guidelines: Standard Antenatal Check. Online. Available: www.thewomens.org.au/StandardAntenatalCheck, 2006.

Tracy S, Screening and assessment. Pairman S, Tracy S, Thorogood C, et al. Midwifery: Preparation for Practice, 2nd edn., Sydney: Elsevier, 2010.

Wickham S. Midwifery Best Practice. London: Elsevier Science, 2008.

About Paediatrics, www.pediatrics.about.com.

Active Birth Centre, www.activebirthcentre.com.

Australian Breastfeeding Association, www.breastfeeding.asn.au.

Australian College of Midwives, www.midwives.org.au.

Birth Psychology, www.birthpsychology.com.

Childbirth.Org www.childbirth.org.

Genetics, www.genetics.com.au.

KidsHealth, www.kidshealth.org.

La Leche League International, www.lalecheleague.org.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (UK), www.nice.org.uk.

Nga Maia (Māori midwives), www.ngamaia.co.nz.

Online Birth Center, www.moonlily.com/obc.

Queensland Health, www.health.qld.gov.au/maternity/publications.asp.

RANZCOG College Statements, www.ranzcog.edu.au/publications/collegestatements.

The Royal Women’s Hospital, www.thewomens.org.au/neonatalclinicalpracticegidelines.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov.