Chapter 9 Ethics and professional practice

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Discuss the key terms listed and their relevance to guiding ethical professional conduct in nursing domains.

• Discuss the importance of ethics to, and in, the profession and practice of nursing.

• Critically examine what constitutes ethical professional practice.

• Discuss the notions of moral accountability and responsibility.

• Identify different moral theories that may guide ethical professional conduct.

• Examine the nature and authority of nursing codes of ethics.

• Outline 10 moral problems that may arise in nursing and healthcare contexts.

• Discuss how moral problems can be distinguished from non-moral problems.

• Discuss five steps that may be taken to identify and deal with moral problems arising in practice contexts.

• Apply one systematic model of moral decision making to a clinical situation.

• Discuss critically at least six ethical issues of importance to the nursing profession.

When people enter the nursing profession they are required to make a commitment to upholding exemplary standards of ethical conduct—that is, standards that are above what would normally be expected of the ‘ordinary person in the street’. The ethical standards that nurses are expected to uphold are prescribed in various codes of ethics, codes of conduct, and competency standards which have been developed and published by recognised professional nursing organisations. Some examples can be found in the codes of ethics and codes of conduct published respectively by the International Council of Nurses (ICN, 2006), the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008a, 2008b), the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO, 2010), the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ, 2009) and other similar bodies (Box 9-1).

BOX 9-1 WEBSITE ADDRESSES FOR LOCATING NURSING CODES OF ETHICS AND CODES OF CONDUCT

AHPRA NURSING AND MIDWIFERY BOARD OF AUSTRALIA (ANMC)

www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/codes-and-guidelines.aspx

ANMC (2008) Code of ethics for nurses in Australia

ANMC (2008) Code of professional conduct for nurses in Australia

ANMC (2006) National competency standards for the registered nurse

ANMC and NCNZ (2010) A nurse’s guide to professional boundaries

In addition to being expected to uphold exemplary standards of ethical professional conduct, nurses are required to also be able to identify and respond effectively to a wide range of ethical issues that may, and do, arise in nursing care and related healthcare contexts. How well nurses are able to respond to these requirements, however, will depend on their knowledge and understanding of what ethics is and how it can best be practised in a culturally, socially and geographically diverse world. Consider the case scenario in the clinical example below.

Both the Code of ethics for nurses in Australia (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008a) and the NZNO (2010) Code of ethics explicitly require nurses to respect the needs, values, culture and vulnerability of people in the provision of nursing care and to ensure that the care provided to patients is culturally informed, safe and appropriate. However, the Codes also require nurses to ‘accept the rights of individuals to make informed choices in relation to their care’. In Mr G’s case it seems that these two requirements clash, raising the important question of what the right thing to do is in this and similar scenarios (see also Johnstone, 2011a). When, if ever, should a family’s pleas be taken into consideration in determining when (if at all), where, how and by whom a cancer diagnosis and poor prognosis should be disclosed to a client? How are nurses and other members of the healthcare team to decide these things? Moreover, do they have the cultural competence necessary to enable them to engage in moral decision-making processes in a safe and effective way? In the case of the NZNO Code of ethics another ethical dimension is added, since this Code also prescribes that nurses must recognise that many sociocultural groups ‘place the importance of the collective on a par with the needs and rights of the individual’ and that the rights of ‘both the individual and the collective must be respected’ (New Zealand Nurses Organisation, 2010:12).

THE CASE OF ‘MR G’

‘Mr G’, a 69-year-old Greek-born man who had migrated to Australia from rural Greece and who spoke little English, was admitted to a major metropolitan hospital for follow-up assessment and treatment of a cancer-related illness. Unfortunately, test results revealed that his condition had unexpectedly worsened, that his prognosis was poor and that palliative care was his best option. Upon learning of this bad news, Mr G’s family pleaded with the attending doctor not to tell their father that his medical condition had worsened and that his prognosis was poor. Mr G’s eldest daughter explained to the doctor that were he to tell Mr G that his cancer had spread, ‘this would destroy his hope and affect his quality of life’. She further explained that, in their Greek culture, ‘it was wrong to tell someone they had terminal cancer’. The doctor objected to the daughter’s request, however, arguing that the matter was ‘not about culture, but about ethics’ and that her father ‘had a right to know’. (Johnstone, 2009a, 2011a)

Being able to respond to this and other kinds of case scenarios in a morally just, responsible and competent way requires nurses to have at least a working knowledge and understanding of:

• key terms and concepts commonly used in discussions on ethical issues in nursing practice

• the importance of ethics to the profession and practice of nursing

• what constitutes ethical professional practice

• notions of moral accountability and responsibility

• reliable guides to ethical professional conduct

• key moral theories that are commonly used to guide ethical decision making and practice in nursing (including cross-cultural ethics)

• the nature and authority of nursing codes of ethics

• the kinds of moral problems that can and do arise in nursing and healthcare domains

• how moral problems can be distinguished from other kinds of problems (e.g. legal problems)

• processes for identifying and dealing with moral problems arising in practice contexts

• moral decision making in practice contexts

• bioethical issues of importance to the nursing profession.

Without the requisite knowledge and understanding of these things, it would be very easy for nurses to ‘rush to judgment’ when engaged in moral decision making and, as a consequence, make moral mistakes. If moral mistakes are made, this can result in morally significant harm to patients, their loved ones and also to healthcare providers. It is for this reason that nurses must make every effort, individually and collectively, to ensure that they are adequately prepared to deal with the moral complexities and quandaries that are likely to arise in their practice and places of work.

Terms and concepts

To be able to discuss ethical issues in nursing in a meaningful way, it is important to have an understanding of such key terms and concepts as ethics, morality, bioethics, nursing ethics, moral principles, moral rules, moral rights and moral duties.

Ethics and morality

Ethics (which may be used interchangeably with the term ‘moral’) is a general term used for referring to various ways of understanding and examining the ‘moral life’ (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009). More specifically, ethics involves thinking critically about and engaging in a systematic examination of what constitutes right and wrong/good and bad behaviour, and the bases upon which we might justify our judgments that an action or decision is ‘morally right or wrong’, all things considered. For example, a nurse may make the moral judgment that abortion is wrong and conscientiously object to assisting with an abortion procedure. Whether conscientious objection ought to be permitted, however, requires a critical examination of the bases on which the nurse has made that judgment, and the provision of sound (moral) justifications (reasons) for the action taken. Ethics, then, is concerned not just with giving values to certain things (e.g. abortion is right/wrong, good/bad), but also with justifying the bases on which judgments about these things might be made (Johnstone, 2009a; Kerridge and others, 2009; LaFollette, 2007).

It is important to clarify the use of the term ‘morality’ in discussions on ethics. In some nursing texts, the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’ are treated as though they refer to different things. This use, however, is not correct. There is, in fact, no philosophically significant difference between the terms ‘ethics’ and ‘morality’, and hence they may be used interchangeably. The only distinction that may be drawn with validity between these two terms is that the word ‘ethics’ comes from the Greek ethikos (originally meaning custom or habit), and ‘morality’ from the Latin moralitas (also originally meaning custom or habit) (Johnstone, 2009a). Of course, today these terms refer to something much more sophisticated than merely custom or habit, as this chapter will show.

Bioethics

The term bioethics (from the Greek bios meaning life, and ethikos, ithiki meaning ethics)—literally, ethics in the realm of life—is a relatively new term that first found its way into public use in the early 1970s in the United States (Reich, 1994). Although the term was originally defined to include environmental concerns, as it is used today its main focus is on (Reich, 1995):

• the rights and duties of clients and healthcare professionals

• the rights and duties of research participants and researchers

• the formulation of public policy guidelines for clinical care and biomedical research.

Although originating in the United States, bioethics has developed as a discipline in its own right in countries around the world; it has also developed as a major international movement of popular interest to professionals and laypersons alike. Today, issues most commonly the subject of bioethics debate in professional journals, as well as in the mass circulation media, include:

• euthanasia and medically assisted suicide

• reproductive technology (including in vitro fertilisation, genetic engineering, surrogacy, embryonic and stem cell research)

• clients’ rights to privacy and confidentiality

• the economic rationalisation of healthcare

• research ethics (see Jecker and others, 2011; Jonsen and others, 2010).

Nursing ethics

Contemporary nursing ethics has been profoundly influenced by the modern bioethics movement and, in several respects, could even be described as a subcategory of bioethics; that is, nursing bioethics. Despite this modern influence, it is important to acknowledge that the nursing profession has its own rich and distinctive history of identifying and responding effectively to ethical issues in nursing and healthcare. In addition to having its own distinctive history of professional ethics, nursing can be said to have developed its own distinctive (nursing) ethics. This development not only has been necessary, but also was inevitable. It has been necessary because ‘a profession without its own distinctive moral convictions has nothing to profess’ and will be left vulnerable to the corrupting influences of whatever forces are more powerful (be they social, political, legal or other in nature) (Churchill, 1989). Furthermore, as Churchill (1989) has asserted in his classic article on the subject, ‘Professionals without an ethic are merely technicians who know how to perform work, but who have no capacity to say why their work has any larger meaning.’ Without meaning, there is little or no motivation to perform well.

What, then, is nursing ethics? Nursing ethics can be defined broadly as the examination of all kinds of ethical and bioethical issues from the perspective of nursing theory and practice, which in turn rest on the agreed core concepts of nursing, namely person, culture, care, health, healing, environment and nursing itself (or, more to the point, its end good), all of which have been comprehensively articulated in the nursing literature. In this regard, then, nursing ethics is not synonymous with, and indeed is greater than, an ethic of care, although an ethic of care has an important place in the general scheme of things encompassing nursing and nursing ethics.

Unlike other approaches to professional and healthcare ethics, nursing ethics recognises the ‘distinctive voices’ that are nurses, and emphasises the importance of collecting and recording nursing ‘stories from the field’. Like other approaches to ethics, however, nursing ethics recognises the importance of providing practical guidance on how to decide and act morally. Drawing on a variety of ethical considerations, nursing ethics, at its most basic, could thus also be described as a nursing practice discipline which aims to provide guidance to nurses on how to decide and act morally in the contexts in which they work.

Moral principles

General standards of conduct that make up an ethical system are known as moral principles. To say that a principle is moral is merely to assert that it is a behaviour guide that entails particular imperatives or obligations; that is, to do or to refrain from something that may have a morally significant outcome. It is generally accepted that moral principles function by specifying that some type of action or conduct is prohibited, required or permitted in certain circumstances (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009; Johnstone, 2009a). By this view, an action or behaviour is generally considered morally right or good if it accords with a given moral principle, and morally bad or wrong when it does not.

Moral principles commonly referred to in healthcare ethics include those of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice (see section on moral theories, below). To illustrate how moral principles work, consider the principle of autonomy. The principle of autonomy demands respect for individuals as self-determining choosers and is widely accepted as a general standard of moral conduct. Given this principle, conduct which respects an individual’s self-determining choices (e.g. a client’s competent decision not to accept a recommended medical treatment) could be appraised as having accorded with the principle of autonomy and therefore as being morally ‘right’ and justified. Conversely, conduct which is disrespectful of an individual’s choices (e.g. a competent client’s decision to refuse medical treatment is rejected and overridden by a professional caregiver) could be appraised as having violated the principle of autonomy and therefore as being morally ‘wrong’. Moral principles thus not only guide conduct, but they can also be appealed to for justifying the conduct in question.

Moral rules

Like moral principles, moral rules also have a place in making up a system or scheme for guiding moral action. And like moral principles, moral rules also function by specifying that some type of conduct is prohibited, required or permitted (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009; Johnstone, 2009a). What distinguishes a moral rule from a moral principle, however, is its nature and force. Moral principles, for example, tend to be general in nature (e.g. do no harm; promote good). Moral rules, in contrast, are both derivative of, and justified by, parent principles and are very specific in their focus (e.g. do not kill others; do not tell a lie). It can be seen, then, that moral rules have a different force, sanctioning power, condition of existence, scope of application and level of concreteness from moral principles. In application, they are generally regarded as having less force than principles.

Rights

Common to discussions on nursing ethics is the notion of rights—including moral rights, human rights and clients’ rights. An understanding of these key terms is, therefore, warranted.

Moral rights

These are to be distinguished here from other kinds of rights, such as civil rights, legal rights, institutional rights and the like. Moral rights generally entail a claim about some special entitlement or interest which ought, for moral reasons, to be protected. For example, people commonly claim rights to such special interests as life, freedom, fair treatment, bodily integrity, health, and so on. The language used in asserting rights typically involves expressions like ‘I have a right to …’, ‘You have a right to …’, and so on.

Human rights

In contrast, human rights refer to a set of special interests that human beings (as opposed to non-human beings, such as animals) are entitled to claim by virtue of being human. Human rights can include moral rights, legal rights, civil rights and so on. A good example of human rights statements can be found in the United Nations (1948) Declaration of Human Rights. This declaration has influenced the development of nursing codes of ethics, not least the ICN’s (2006) revised Code of Ethics for Nurses, the NMBA’s Code of ethics for nurses in Australia (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008a) and, to some extent, the NZNO’s (2010) Code of ethics, which although not overtly informed by a human rights framework, nonetheless contains statements that prescribe the protection of client rights (see Box 9-1).

Clients’ rights

These can be described as a subcategory of human rights. Statements of clients’ rights tend to entail statements about particular moral interests that a person might have in healthcare contexts and that require special protection when that person assumes the role of a client. Clients’ rights that might be commonly claimed include the right to healthcare, the right to make informed decisions, the right to confidentiality and the right to dignity and to be treated with respect.

Moral duties

A moral duty (to be distinguished from a legal duty, a civic duty and so on) is an action which a person is bound, for moral reasons, to perform. Language used in identifying duties typically involves expressions such as ‘I have a duty …’, ‘You have a duty …’, and so on. In a rights view of ethics, someone claiming a valid right supplies a moral reason for why another must act morally towards them. Indeed, moral duties are sometimes described as being correlative; that is, in relation to another’s rights claims. To put this in another way, if one person claims a right, this may entail another having a correlative duty to respect and respond to that right. For example, if a client claims the right to make an informed decision regarding nursing care, then an attending nurse could be said to have a correlative duty to respect and uphold that right. Moral reasons can also be supplied by an appeal to ethical principles. For example, adoption of the principle of autonomy would impose on decision makers a duty to uphold its prescriptions; namely, to respect people as self-determining choosers.

A critical task for decision makers is deciding just what their duties are in given situations. Making the correct decision depends on determining what counts as an overriding moral reason for doing something (bearing in mind that moral reasons are generally regarded as being stronger or more pressing than other kinds of reasons, such as personal preferences, civic duty and group membership). For example, in the case of a rights claim being made, whether or not another has a corresponding duty will depend on whether the right being claimed is genuine, whether the entity has moral rights at all and whether an agent does in fact have a duty correlative to the rights claim being made.

Sometimes people confuse rights with duties, and vice versa. A useful way to guide an understanding of the distinction between rights and duties is to consider that when people claim a right they are making a claim with respect to their own interests; in contrast, when people claim a duty they are making a claim with respect to the interests of another or others.

The importance of ethics

Nursing has a profound ethical dimension. Its practice never occurs in a moral vacuum and is never free of moral risk (Johnstone, 2009a). Even the smallest of nursing actions (e.g. giving an aspirin tablet) could, potentially, result in significant moral consequences—bad as well as good. Moreover, as long as nurses work with and care for other people, they will never be able to avoid the moral problems and issues that will invariably arise during the course of their practice.

During their everyday practice, nurses will often be confronted by such questions as: What should I do in this situation? How do I know I’m doing the right thing? What are my moral obligations in this case? The case of ‘Ms Winnow’, a competent patient with a health history of diabetes, obesity and large areas of skin breakdown who refused nursing care, helps to illustrate this point (Dudzinski and Shannon, 2006). The cares which Ms Winnow initially refused included being turned, having wound care for her decubitus ulcers and undergoing incontinence management. Ms Winnow’s refusals left attending nurses confronted with the dilemma of on the one hand wanting to respect her wishes and yet, on the other, knowing that respecting her wishes would place her at further risk of harm and suffering—including further breakdown of her ulcerated skin. In this case, provocative questions arise: What should her attending nurses do? What are their moral obligations to Ms Winnow? And how are they to know that, whatever they decide and do, they have done the right thing, all things considered?

When encountering an ethical problem in the workplace, nurses often worry about whether the moral decisions they make are ‘correct’; nurses are also known to experience moral perplexity and distress when—for various reasons—they did not ‘get it right’ or were unable to carry out what they had carefully and conscientiously thought was the right thing to do. It is for these kinds of reasons that ethics has assumed paramount importance in nursing.

Moral conduct in nursing

Nurses face many complex and varied moral problems during the course of their practice, which cannot be ignored. In fact, there are stated expectations in nursing standards of conduct that nurses not only must be able to identify and respond appropriately and effectively to a range of ethical problems and issues in nursing and healthcare contexts, but also must demonstrate moral competence in regard to these things.

Moral/ethical competence can be defined in terms analogous to clinical competence as the up-to-date knowledge and skills, and soundness of judgment, required of a profession as well as the demonstrated ability ‘to achieve desired outcomes through the performance of defined skills’ (Jormsri and others, 2005). In Australia, the specific moral competencies expected of registered nurses are outlined in the NMBA’s National competency standards for the registered nurse (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2006). This document makes clear that, in keeping with their ethical responsibilities as competent professionals, registered nurses must demonstrate ‘a satisfactory knowledge base’ as well as accountability for practice in regard to the protection of individual and group rights. The particular moral competencies expected of a registered nurse are listed under Standard 2: Practises within a professional and ethical nursing framework, and include:

• Practises in accordance with the nursing profession’s codes of ethics and conduct

• Practises in a way that acknowledges the dignity, culture, values, beliefs and rights of individuals/groups

• Advocates for individuals/groups and their rights for nursing and healthcare within organisational and management structures.

These competencies, in turn, are clarified to include the capabilities to:

• give due consideration to the nurse’s ethical responsibilities in all aspects of practice

• maintain an effective process of care when confronted by differing values, beliefs and biases

• recognise the rights of others and ensure that one’s own personal values and attitudes are not unjustly imposed on others

• provide care to individuals and groups that is informed about, sensitive to and respectful of their race, ethnicity, culture, language, religion, age, gender, sexuality, physical or mental status, and other distinguishing characteristics

• identify and adhere to strategies aimed at promoting the rights of individuals/groups in the healthcare setting

• act to ensure the rights of individuals/groups are not compromised

• protect the rights of individuals and groups in regard to informed decision making

• protect the rights of individuals and groups in regard to privacy and confidentiality

• question and/or clarify with members of the healthcare team any interventions that might seem inappropriate

• engage in morally responsible and accountable nursing practice.

In New Zealand, the specific moral competencies expected of registered nurses are outlined in the NCNZ’s (2009b) Competencies standards for registered nurses. These standards require registered nurses to be able to demonstrate knowledge and judgment and be ‘accountable for own actions and decisions, while promoting an environment that maximises client safety, independence, quality of life and health’. The particular moral competencies (and related indicators) expected of a registered nurse are variously listed under Domain 1: Professional responsibility and Domain 2: Management of nursing care, and include:

• Accepts responsibility for ensuring that his/her nursing practice and conduct meet the standards of the professional, ethical and relevant legislated requirements.

• Maintains clear, concise, timely, accurate and current client records within a legal and ethical framework.

• Discusses ethical issues related to health care/nursing practice (for example: informed consent, privacy, refusal of treatment and rights of formal and informal clients).

• Promotes a quality practice environment that supports nurses’ abilities to provide safe, effective and ethical nursing practice.

Moral accountability and responsibility

In identifying and responding effectively to moral problems in the workplace and, indeed, when practising in a professional capacity generally, nurses are morally accountable and responsible for their actions (Johnstone, 2009a). Thus, when a nurse breaches the agreed ethical standards of the nursing profession, there is an expectation that they will be made to account for and, ultimately, be held responsible for their conduct. Moral accountability and responsibility, however, do not reside only in individual nurses. The nursing profession as a whole, and those charged with the responsibility of regulating it, are also morally accountable and responsible for their actions. This is an important point, since it has a significant bearing on the kinds of strategies that might otherwise be used to respond effectively to situations in which the agreed ethical standards of the profession are at risk of being or have already been breached.

Understanding the nature and moral implications of professional accountability and responsibility in nursing requires a commensurate understanding of moral theories of accountability and responsibility. For instance, in the philosophical literature, accountability has classically been taken to mean:

[being] obliged to give satisfactory reasons for one’s actions, to be capable of giving an explanation for one’s actions, to be responsible for one’s conduct, to be made to pay for one’s conduct, or to reckon with the consequences of one’s actions. (Fry-Revere, 1992)

In turn, the notion of responsibility (of which accountability is a form) has been taken broadly to include not only one’s ‘intentional conduct’ (i.e. a person’s deliberate acts and omissions), but also:

anything with which one is seen to have a causal relationship (whether this perception is justified or not), including moral character, physical and psychological characteristics, salvation, and even unintentional effects on one’s own life or the lives of others. (Fry-Revere, 1992)

Drawing on both of the above accounts, moral theories of accountability hold that:

a person X, is accountable for his or her actions if X acted freely or intentionally and X’s action or inaction is causally related to the outcome for which X is being held accountable. (Fry-Revere, 1992)

Theories of moral accountability tend to emphasise accountability to oneself or to a superior entity. Either way, claims of moral accountability tend to assume that:

Human beings are free to act and cause events for which they are directly responsible and that some form of internal mechanism of accountability, whether based on conscience or belief, is essential to human interaction. (Fry-Revere, 1992)

As well, some form of external mechanism (e.g. an ethics complaints committee) is also essential to human interaction (Spencer and others, 2000).

It can be seen, then, that the issues of moral accountability and responsibility have important implications for nurses. For instance, an ongoing problem facing the nursing profession is that although nurses have enormous responsibilities as healthcare providers, they often lack the lawful authority they need in order to be able to fulfil these responsibilities in a safe and effective way (Johnstone, 1994, 2009a).

Guides to ethical professional conduct

As has previously been considered, when making moral judgments and decisions in nursing care domains, nurses are often faced with such perplexing questions as ‘What should I do and what is the right thing to do in such-and-such situation?’, ‘Are my judgments and decisions morally correct, all things considered?’, ‘How should I decide?’ and ‘Have I done (am I doing) the right thing?’ These and similar questions become even more pressing when considered against the backdrop of stringent moral accountabilities and responsibilities otherwise expected of registered nurses.

Possible answers to these and related questions can be sought by appealing to moral theories and/or nursing codes of conduct; noting, however, that neither of these is without some difficulties with respect to their moral authority and capacity to guide and justify particular actions in specific contexts. As Beauchamp and Childress (2009) explain, ‘Many practical questions would remain unanswered even if a fully satisfactory general ethical theory were available.’

Moral theories

It is generally accepted that moral theory is crucial, not just for the purposes of guiding moral decision makers in their thoughts and actions, but also for providing sound justifications for the decisions made and actions taken.

Moral problems arise frequently in healthcare contexts. This is not surprising given the culturally diverse range and complexity of the moral values that are operating and expressed in healthcare domains. Indeed, healthcare practice is profoundly value-laden in a morally significant sense, and hence it is inevitable that some moral conflicts and disagreements will arise. Further, given the complexity of the values that operate in healthcare domains, it is inevitable that sometimes the choices made (by nurses as well as others) will be problematic, insofar as they may express moral values, beliefs and evaluations which are not shared by others or with which others do not agree.

When experiencing situations involving moral problems and disagreement, it is tempting for decision makers to rely on their own ways of thinking and personal preferences to sustain the points of view they are advocating. Sometimes, however, a person’s ways of thinking and personal preferences may not be reliable or worthy action guides because these can result from prejudice, self-interest or ignorance. Thus, decision makers need to look elsewhere to justify their moral choices and actions. Ethical/moral theory is commonly regarded as a reliable source from which such justifications can be sought.

There are a number of different moral theories that can be appealed to for guiding and justifying moral decision making and conduct, all of which, to varying degrees, have both formed the basis of and influenced the development and practice of nursing ethics. Notable among these are deontological ethics, teleological or consequentialist ethics, ethical principlism, moral rights theory, virtue ethics and cross-cultural ethics. A brief summary of each of these theories is outlined below.

Deontological ethics

According to deontological ethics, duty is the basis of all moral action. Taken at its most basic, deontology asserts that some acts are obligatory (duty bound) regardless of their consequences. For example, a deontologist might assert that one has a duty to always tell the truth. By this view, the deontologist is duty bound to always tell the truth even when doing so might have horrible consequences. An important question to ask here is: How do we know what our duty is?

One possible answer to this question can be found in classical deontological theory that derives from religious ethics and what is otherwise known as ‘divine command theory’. According to this view, it is God’s command that determines our moral duties. If, for example, God commands ‘Thou shalt not kill’, ‘Thou shalt not steal’ and the like, then conduct that accords with (obeys) these commands is morally praiseworthy (right and justified). Conduct that contradicts God’s commands, in contrast, warrants condemnation (as wrong and unjustified). This is because and only because it is God’s command (Morriston, 2009; Wainwright, 2005).

There are many examples of deontological ethics influencing decision making in healthcare domains. For example, Jehovah’s Witnesses refuse life-saving blood transfusions on the grounds that to accept such treatment would be tantamount to violating God’s command that prohibits taking blood. Another example can be found in a deontological adherence by some doctors and surgeons to the preservation of ‘medically hopeless’ human life whatever the costs (read ‘consequences’), resulting in the administration of ‘futile’ medical treatment to clients sometimes even against their will (Schneiderman and Jecker, 2011).

Another answer can be found in what is otherwise known as ethical rationalism. This view dates back to the work of the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who held that the supreme principle of morality was reason, whose ultimate end is goodwill. According to a 1972 translation, Kant stated that reason is free (autonomous) to formulate moral law and to determine just what is to count as being an overriding moral duty. Kant held duty to be that which is done for its own sake, and ‘not for the results it attains or seeks to attain’ (Kant, 1972). Kant further believed that moral considerations (duties) were always overriding in nature—in other words, should take precedence over other considerations.

In terms of determining what one’s actual duty is, Kant suggested that this can be done by appealing to some formal (reasoned) principle or maxim. In choosing such a maxim, however, Kant warned that we must take care not to choose something that would privilege our interests over the interests of others. Kant’s solution to this problem was to establish a universally valid law called the ‘categorical imperative’. This law states: ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become universal law’ (Kant, 1972). In other words, we should act only on maxims that we are prepared to accept as holding for everybody (including ourselves) throughout space and time. A variation of Kant’s law can be found in what is popularly known as the Golden Rule: ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’

Teleological ethics

According to teleological theory (also known as consequentialism), actions can be judged right and/or good only on the basis of the consequences they produce. In this respect, teleology denies everything that deontology asserts.

The most popularly known teleological theory of ethics is utilitarianism, which has as its central concern the general welfare of people as a whole, rather than of individuals. In short, utilitarianism views the world not in terms of certain individual rights which people may or may not claim, but in terms of the collective and overall welfare and interests of people generally (a consequentially ‘good outcome’). The perspective of utilitarianism is persuasive in that it promotes a universal point of view; namely, that one person’s interests cannot count as being superior to the interests of another just because they are personal interests (Rosen, 2003). To put this in another way, I cannot claim that my interests are more deserving than your interests are, just because they are my interests.

Classical utilitarianism, first advanced by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and later modified by the work of the British philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806–73), holds roughly that moral agents have a duty to ‘maximise the greatest happiness/good for the greatest number’ (Bentham, 1962; Mill, 1962). This view has resulted in classical utilitarianism being dubbed the ‘greatest happiness principle’. Because of difficulties associated with calculating both individual and collective happiness and unhappiness, and the problem of individual interests being sacrificed for the collective whole, classical utilitarianism theory has been largely abandoned in favour of recent utilitarian theory. Of particular note is ‘preference utilitarianism’, which views the maximisation of individual preferences as being of intrinsic value rather than the maximisation of happiness per se. This is because, as Beauchamp and Childress (1989) have classically explained, ‘what is intrinsically valuable is what individuals prefer to obtain, and utility is thus translated into the satisfaction of those needs and desires that individuals choose to satisfy.’

Preference utilitarianism is also considered more plausible because it is relatively easy to calculate what people’s preferences are—all we have to do is to ask people what it is they prefer. And where their preferences are at odds with ethical conduct, we have no obligation to respect them. This position, however, rests on assumptions about the ‘use’ of utility and its supposed intrinsic value, which some contend it does not have (Millgram, 2000).

Ethical principlism

One of the most popular ethical theories used today when considering ethical issues in nursing and healthcare is the theory of ethical principlism. Ethical principlism is the view that ethical decision making and problem solving are best undertaken by appealing to sound moral principles (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009). The principles most commonly used are those of autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice.

Autonomy

As a concept, autonomy refers to a person’s self-contained and independent ability to decide. As a principle, autonomy prescribes that people ought to be respected as self-determining choosers and that it is wrong to violate a person’s considered and autonomous choices. This is so even if we do not agree with another’s choices and regard them as foolish, provided they do not interfere significantly with the moral interests of others. Applied in nursing and healthcare contexts, the principle of autonomy imposes on healthcare professionals a moral obligation to respect clients’ choices regarding recommended medical treatment and associated care. Further, this obligation holds even if attending healthcare professionals do not agree with the choices that clients make.

Non-maleficence

Maleficence refers to harm or hurt, so non-maleficence means to avoid harm or hurt. Simply stated, the principle of non-maleficence prescribes ‘do no harm’. Applied in nursing and healthcare contexts, the principle of non-maleficence would provide justification for condemning any act that unjustly injures a person or causes a person to suffer an otherwise avoidable harm. Harm, in this instance, may be broadly taken as involving the invasion, violation, thwarting or ‘setting back’ of a person’s significant welfare interests to the detriment of that person’s wellbeing (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009).

Beneficence

The principle of beneficence, similar in meaning to the word ‘benefit’, entails a positive obligation to ‘act for the benefit of others’; that is, to promote their welfare and wellbeing (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009). Thus it prescribes ‘do good’. Beneficent acts can include such virtuous actions as care, compassion, empathy, sympathy, altruism, kindness, mercy, love, friendship and charity (Johnstone, 2009), all of which stand to find ready application in nursing and healthcare contexts.

Justice

The principle of justice can be conceptualised in a variety of ways. For instance, justice can be interpreted as involving retribution (retributive justice, e.g. ‘an eye for an eye’), an equal distribution of benefits and burdens (distributive justice), justice as mercy, justice as harmony, justice as equality (‘equals must be treated equally, and unequals unequally’), justice as fairness, justice as what is deserved (‘just desserts’), and justice as inclusiveness, fellowship, compassion and respect (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009; Nussbaum, 2006; Sen, 2009). More recently, justice has also been conceptualised as a basic human need (Johnstone, 2011b; Taylor, 2006). The conceptualisations of justice most commonly used in healthcare are those of justice as fairness (an intuitive sense of justice) and as an equal distribution of benefits and burdens (a rationalistic sense of justice). For example, on the basis of both an intuitive and a rational appeal to the principle of justice, it might be concluded that it is manifestly unfair and disproportionately burdensome to withhold life-saving treatment (e.g. cardiac surgery) from those who cannot afford to pay for such treatment. Such an action stands as being burdensome since it places the poor in a disadvantaged position in relation to the rich—the poor stand to suffer a burden of compromised life expectancy (which the rich do not) on account of their inability to pay. At an intuitive level, such a situation does not feel right in that it feels ‘unfair’.

Although vulnerable to criticism on a variety of accounts, ethical principlism has increasingly come to replace more classical theoretical approaches to identifying and resolving moral problems in healthcare contexts. Since ethical principlism is widely appealed to in the healthcare and related ethics literature, it is important that nurses have at least a working knowledge and understanding of this approach. It is necessary for nurses to be aware, however, that principlism is not without its limitations. As the cases of ‘Mr G’ and ‘Ms Winnow’ considered earlier have demonstrated, applying these principles in practice can be very difficult.

Moral rights theory

Another popular and commonly used moral theory is that of moral rights theory, a form of deontological ethics. Moral rights have been particularly influential in the development of discourses on clients’ rights and the development of various codes and charters outlining clients’ rights in healthcare (Weller, 2006). As discussed earlier, a moral right is a special interest that a person may have and which ought to be protected and upheld for moral reasons.

There is no simple thesis of moral rights (Campbell, 2006; Dyck, 2005). Indeed, there are a number of bases on which an entity could validly claim moral rights, including natural law, common humanity, rationality and interests.

Natural law

By this view, rights are the product of the laws of nature and apply equally to everybody; thus everybody is subject to them, just as they are to the laws of nature (e.g. gravity).

Common humanity

All human beings have rights equally, just by virtue of being human. This is because being human is not something over which human beings have control.

Rationality

Only people who are capable of rational, autonomous thought are entitled to claim rights. This means, controversially, that entities such as babies, unconscious people, people with severe brain injuries and the like are excluded from having rights.

Interests

In order to have rights, an entity must have interests; and in order to have interests, an entity must have the capacity to be benefited or harmed; which, in turn, presupposes sentience (the capacity to experience pleasure and/or pain) (Feinberg, 1979). This classic view is commonly seen as being among the most tenable theses of moral rights, since it is more inclusive than the other theories; for example, it includes both the rational and the non-rational, and other species besides human beings.

Virtue ethics

In recent times there has been a resurgence of virtue theory in ethics and a re-examination of the importance of ‘characterological excellence’ in determining ethical conduct (Oakley, 2006; Van Hooft, 2006). This is made manifest by the expression of such moral virtues as care, compassion, kindness, empathy, sympathy, altruism, generosity, respectfulness, trustworthiness, personal integrity, wisdom, courage and fairness. Virtue theorists claim that without the characterological excellence of virtue, ‘a person could, robot-like, obey every moral rule and lead the perfectly moral life’ but in doing so would be acting more like ‘a perfectly programmed computer’ than a morally responsible human being (Pence, 1991). There is a sense in which being moral involves much more than merely following rules; the missing link, claim virtue theorists, is character. On this point, Pence (1991) writes:

we need to know much more about the outer shell of behaviour to make such judgments, that is, we need to know what kind of person is involved, how the person thinks of other people, how he or she thinks of his or her own character, how the person feels about past actions, and also how the person feels about the actions not done.

Virtue ethics is particularly relevant to nursing and to nursing ethics since virtuous conduct is intricately linked to therapeutic healing behaviours and the promotion of human health and wellbeing.

The nursing profession’s well-articulated ethic of care (regarded by many influential nurse theorists as the moral foundation, essence, ideal and imperative of nursing) is consistent with a virtue theory of ethics (see the classic works of the following nurse theorists: Benner and Wrubel, 1989; Gaut, 1991; Gaut and Leininger, 1991; Leininger, 1988, 1990; Roach, 1987; Watson, 1985a, 1985b). Significantly, an ethic of care is enjoying a renaissance in the nursing ethics literature—particularly in regard to the issue of caring for vulnerable and marginalised groups of people at risk of being treated as ‘different’ and as ‘others’ by healthcare providers (Myhrvold, 2006; Nussbaum, 2006).

Cross-cultural ethics

As highlighted by the ‘Mr G’ case discussed in the opening paragraphs to this chapter, another perspective on ethics and bioethics that warrants consideration by nurses is cross-cultural ethics. The basic assumptions of cross-cultural ethics reflect the views that:

• ethics is very much a product of the culture, society and history from which it has emerged

• all cultures have a moral system, but what this system is and how it is applied will vary across, and sometimes even within, different cultures

• there is no such thing as a universal ethic; that is, one ultimate standard of moral conduct which applies to all people equally regardless of their individual circumstances, context and culture—in other words, a ‘one size fits all’ approach to ethics (Johnstone, 2009a, 2011a).

In any culturally diverse society it is imperative that a culturally informed, knowledgeable and sensitive approach to healthcare is taken (Fry and Johnstone, 2008; Johnstone, 2011a; Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2008). One reason for this is that a failure to adopt such an approach can result in otherwise serious moral harm being caused to people. Cross-cultural ethics, therefore, goes far beyond merely considering and critiquing the nature and content of mainstream ethical theories; it also involves a systematic examination of the moral implications of cultural and linguistic diversity in healthcare domains, for example the extent to which clients of non-English-speaking and diverse cultural backgrounds suffer unnecessarily on account of the cultural and language differences between them and their professional carers (see, for example, Divi and others, 2007; Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2006, 2009a).

Nurses and other healthcare workers have a stringent moral responsibility to avoid and/or prevent the otherwise avoidable moral harms that can result from a failure to take into account the language and cultural needs of their clientele (Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2006, 2008, 2009a). The harmful aftermath of racism in healthcare is a particular example of this. Racism in nursing and healthcare is a problem that has not been formally recognised as an important ethical professional issue (Johnstone and Kanitsaki, 2009b, 2010). A cross-cultural approach to ethics would not only help identify the existence of racism in nursing and healthcare contexts, but also guide an effective response for dealing with it and, if not successful in eradicating it, at least minimise its harmful consequences to client health.

Nursing codes of ethics

Nursing codes of ethics have long featured as guides to ethical professional conduct in nursing. Just what they are, however, and how they function has not always been clearly understood.

As discussed extensively elsewhere (Johnstone, 2009a), a code may be defined as a conventional set of rules or expectations devised for a select purpose. By this view, a code of professional ethics could be described as a document laying out a set of moral rules and/or expectations devised for the purposes of guiding ethical professional conduct. Although codes of ethics are not fully developed systematic theories of ethics, they nevertheless tend to reflect a rich set of moral values that have been expressed and explained through a process of extensive consultation, debate, refinement, evaluation and review by practitioners over time.

Codes can be either prescriptive or aspirational in nature. In the case of prescriptive codes, provisions are ‘duty-directed, stating specific duties of members’ (Skene, 1996). In contrast, aspirational codes are ‘virtue-directed, stating desirable aims while acknowledging that in some circumstances conduct short of the ideal may be justified’ (Skene, 1996). Either way, codes of ethics have as their main concern directing ‘what professionals ought and ought not to do, how they ought to comport themselves, what they, or the profession as a whole, ought to aim at’ (Lichtenberg, 1996).

In Australia, for example, the NMBA’s Code of ethics for nurses in Australia (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008a) and Code of professional conduct for nurses in Australia (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008b) make explicit the ethical standards that Australian nurses are expected to uphold in the interests of promoting and protecting the moral interests and welfare of consumers, and the actions that must be taken against nurses if these agreed standards are breached; similarly, the NZNO’s (2010) Code of ethics and the NCNZ’s (2009) Code of conduct for nurses (see Box 9-1).

Historically, the professional–client relationship has been a special one in which certain privileges have been accorded to the attending professionals in return for the special (read ‘expert and often essential’) services they provide to their clients in the community at large. The professional–client relationship has also tended to be an unequal relationship, with the professional usually holding the balance of power. This imbalance of power has been implicated in both potential and actual vulnerability of clients when seeking and receiving professional services. Although the nature of the professional–client relationship has changed dramatically in recent decades, it nevertheless remains characterised by an imbalance of power involving, among other things, an imbalance of knowledge and legitimated authority to use knowledge.

This imbalance of power has helped to create a demand and given rise to an expectation among members of the community that professionals ought to, and will, submit to a system of rules imposing a greater constraint on their professional conduct than would otherwise be imposed on the conduct of ordinary (lay) people. All in all, there has emerged a general expectation that professionals will act in a supremely ethical manner when rendering services to clients.

Over the past several decades, recognition of the responsibility of professionals to act in an ethically exemplary manner has seen considerable attention being given to devising and agreeing to a system of rules to govern both personal and professional conduct (Coady and Bloch, 1996; Kerridge and others, 2009). A code of ethics serves this purpose by providing a clear and singular guide to conduct.

Codes of ethics serve a variety of functions. Key among them are to maintain ethical standards of conduct and to help the regulation of ethical professional conduct. These outcomes are thought to be achieved by the direct and the indirect value of codes in fostering and maintaining the standards of ethical professional conduct by cultivating moral character, by articulating certain characteristics and ideals of a profession, by facilitating the internalisation of these values and ideals by members of the professional group in question, and by prescribing and proscribing conduct that is otherwise not amenable to legislation, by specifying rules of conduct; for example, ‘Nurses will keep in confidence information gained in the professional–client relationship’ (Coady and Bloch, 1996; Johnstone, 2009a).

A characteristic feature of codes of ethics is their voluntariness. What this means is that persons subscribing to or upholding the terms of a given code of ethics do so free from any coercive or manipulative influences. In other words, compliance is and ought to be both autonomous and voluntary.

Like other moral action guides, however, codes are not without their limits. Problems include their having limited moral authority (being mostly a statement of rules, codes cannot override the demands of a more systematic and reflective system of moral principles and standards) and limited practical application (e.g. codes may offer very little practical guidance on how to make sound moral decisions when dealing with complex ethical issues and/or particular situations). The case of Mr G, referred to in the opening paragraphs of this chapter, underscores this point.

Despite these limits, codes of ethics and, of relevance to this discussion, nursing codes of ethics have an important role to play in regard to:

• advising the public of the values and ideals it can expect of nurses when delivering care to clients

• informing nurses of the values and ideals they are expected to uphold upon becoming members of the broader nursing profession

• providing standards against which nurses’ conduct can be measured and, if found to be in breach of these standards, censured via the lawful processes of disciplinary action.

Moral problems in nursing

When delivering nursing care to clients, nurses will encounter a range of moral problems. These problems range from the relatively simple to the extraordinarily complex, and can cause varying degrees of perplexity and distress in those who encounter them. Nurses, like other healthcare professionals, have a fundamental and unavoidable moral responsibility to be able to identify and respond effectively to the moral problems they encounter—which includes self-care (Johnstone, 2009a).

The ability of nurses to deal effectively with the problems they encounter will depend on a range of variables, including:

• their ability to correctly identify a given moral problem

• the level to which they are prepared educationally, psychologically and emotionally to be able to respond to various moral problems as they arise and are identified

• the extent to which institutional norms and practices are supportive of the moral authority and experience of nurses to deal with moral problems in the workplace

• the extent to which other legal processes recognise and are responsive to the moral authority of nurses and the ethical standards of the nursing profession generally.

Nursing point of view

When moral problems arise in healthcare contexts, the nurse’s observations and considered judgments (the ‘nursing point of view’) can play a vital role in the correct identification and mitigation of the problems at hand. Since nurses may be involved in very intimate physical acts with clients, such as bathing, feeding and special procedures, information that is not generally solicited by other attending healthcare workers, including doctors and social workers, is often revealed to nurses by clients and their families. Details about family life at home, information about coping styles or personal preferences and details about fears and insecurities may come out during nursing interventions. Such information can be vital to ensuring sound moral decision making concerning client care.

On the other hand, it is important for nurses to remember that care of any one client has become multidisciplinary and fragmented. The nursing point of view is part of a larger picture that is best built by all members of the healthcare team, including the client and family. Managers and administrators from different professional backgrounds may also contribute to ‘moral conversations’, as they are able to bring knowledge of systems, allocation of resources, financial possibilities or constraints to the decision-making process.

Wherever moral problems arise, the nursing point of view is valuable and often essential. It is both an obligation and a privilege for the professional nurse to accumulate information on the issues, examine personally held moral values and beliefs, and share knowledge with clients and with colleagues in an effort to overcome the difficult issues that often underlie and/or constitute moral problems in healthcare.

Distinguishing moral problems from other kinds of problems

Being able to identify and respond effectively to moral problems in professional practice requires an understanding of what a moral problem is and how it might be distinguished from other kinds of problems, for example a legal problem or a clinical problem.

It is generally accepted that a moral problem has as its central concerns:

• the promotion and protection of people’s genuine wellbeing and welfare, including their interests in not suffering unnecessarily

• responding justly to the genuine needs and significant moral interests of different people

• determining and justifying what constitutes right and wrong conduct in a given situation (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009; Johnstone, 2009a; Kerridge and others, 2009).

Nurses are fundamentally involved with promoting and protecting people’s genuine wellbeing and welfare and, in achieving these ends, responding justly to the genuine needs and interests of different people. And so long as nurses work and interact with people in a professional capacity, they will continue to be involved in the promotion and achievement of these moral ends.

Moral problems (also called ethical issues) fall roughly into three categories:

1. those that involve procedural difficulties associated with the actual identification and satisfactory resolution of moral problems in nursing and healthcare contexts, such as unethical conduct, moral impairment, moral incompetence, moral disagreement and ethical dilemmas

2. those that involve everyday ethical issues that arise in face-to-face ‘hands-on’ encounters with clients and co-workers

3. the more ‘exotic’ issues of applied ethics involving a range of bioethical issues, such as clients’ rights to informed consent, confidentiality or euthanasia/assisted suicide.

Identifying and responding effectively to moral problems in nursing

All nurses are expected to be able to identify correctly and respond effectively to moral problems in the workplace. The kinds of problems that may be encountered are summarised below.

Moral unpreparedness

A person is not adequately prepared educationally, psychologically or emotionally to deal with a presenting moral problem. When faced with a moral problem, a morally unprepared nurse may not take appropriate action to remedy a troubling situation on the grounds of ‘I did not know what to do’.

Moral blindness

A nurse (or other member of the healthcare team) is blind to the ethical dimensions of a presenting problem; for example, they may wrongly regard the problem at hand as a clinical or technical problem requiring only a clinical solution, not a moral one. By analogy, like a colour-blind person who cannot see certain colours, a morally blind person cannot see the moral dimensions of a given situation or problem. Take, for example, a medical decision not to resuscitate a client. This may be construed as simply ‘good medical practice’ and, as such, outside the concerns of ethics, regardless of the fact that such a decision may have been based firmly on quality-of-life considerations and made without the client’s knowledge or consent.

Moral indifference

A nurse (or other member of the healthcare team) is largely unconcerned about the demands of ethical professional conduct. A nurse who is morally indifferent may, for example, demonstrate a lack of interest in or concern about a client’s wellbeing and/or welfare. The morally indifferent nurse might refrain from engaging in any discussions or activities aimed at client advocacy, or disregard a client’s pain and discomfort.

Amorality

A nurse or other member of the healthcare team literally has no morality. As the word itself suggests, there is an absence of morality in these people.

Immorality/unethical conduct

A nurse or other member of the healthcare team accepts ethical standards of conduct, but nevertheless deliberately violates them. An example is the case of a nurse who steals money from an elderly client or fraudulently uses her credit card.

Moral complacency

A nurse or other member of the healthcare team is unwilling to accept that their moral beliefs and viewpoints may be mistaken. Such a nurse is reluctant to accept that their point of view is often just one among many that deserves to be considered, compared and contrasted. For example, a morally complacent nurse may hold firmly to the view that it is morally wrong to perform resuscitation on people over the age of 75 (regardless of the person’s wishes to the contrary), since they are already old, at the end of their lives and should not be troubled by having to decide such burdensome issues.

Moral fanaticism

A nurse or other member of the healthcare team uncritically holds extreme moral views. For example, a nurse might uncritically and fanatically uphold the view that, irrespective of their stated cultural values and beliefs and expressed wishes, people diagnosed with cancer should be told their cancer diagnosis by an attending doctor. Moreover, such information should be communicated ‘directly’ and ‘frankly’ to the person by the doctor, regardless of the person’s or the family’s wishes in regard to what information should be given, when, where, how and by whom. Such a nurse might further hold the view that ‘Even if this information may result in causing the patient otherwise preventable distress, they should still be told directly whether they wish it or not, whether the family is there or not, because “they have a right to know”. And this is just the way it should be’.

Moral disagreement

Nurses or other members of the healthcare team may disagree about the morally correct course of action to take in a given case. Disputing parties may share and subscribe to common moral standards, but disagree as to:

• when one set of standards should override another set, for example whether the principle of autonomy is stronger than the principle of non-maleficence in a situation involving the disclosure of a poor diagnosis to a client

• what should count as acceptable exceptions and limitations to applying the standards in question, for example a nurse might be willing to act as a client’s advocate but only so long as their own significant moral interests are not compromised; another nurse might not subscribe to this limitation

• whether a given set of standards should be chosen at all, for example two nurses might disagree that the moral principle of autonomy ought to be given consideration in the euthanasia debate.

Moral disagreement may also arise when disputing parties do not agree on any ethical standards at all.

Moral dilemmas

Nurses or other members of the healthcare team may find themselves between what is colloquially referred to as ‘a rock and a hard place’. Broadly speaking, a moral dilemma may be described as a situation involving choice between what seem to be two equally undesirable alternatives. Moral dilemmas commonly take one of three forms:

1. Where there exists a logical incompatibility between two or more moral principles; for example, in the context of informed decision making, where the information being disclosed is potentially harmful it may not be possible to uphold both the principle of autonomy (i.e. respect a client as a self-determining chooser) and the principle of non-maleficence (i.e. protect the client from otherwise avoidable harm) (refer to the case of Ms Winnow, discussed earlier).

2. When competing moral duties exist and a nurse cannot fulfil both, they must choose which duty to fulfil; for example, in a life-and-death situation, a nurse might feel duty bound to protect both a client and the chosen carers from the harm of suffering associated with the crisis at issue. That might not be possible and no matter what strategies the nurse uses, someone is going to suffer. Here the nurse might ask: ‘Which duty ought I to fulfil?’

3. When competing and conflicting interests exist; for example, two clients may have equally deserving rights claims and a nurse may be in a position to respond to only one of these claims at a time. Abortion is a good example here, especially in cases where the rights of the mother might compete with the rights of a fetus and/or the father. Here the nurse might ask: ‘Whose interests ought I to uphold?’

Moral stress, distress and moral perplexity

A nurse or other member of the healthcare team may suffer stress, distress and perplexity on account of having identified a given moral problem but been largely unsuccessful in resolving it. These states can manifest as emotional turbulence, indignation, incredulity, rage and outrage, anger, despair and an overwhelming and paralysing sense of hopelessness. If not resolved, this problem can lead to burnout and nurses resigning from their jobs.

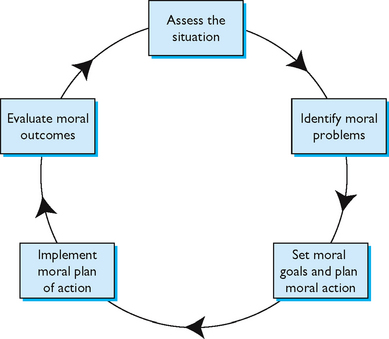

Processes of moral decision making

Moral problems, like other kinds of problems, can be approached using a systematic decision-making process. Like the nursing process, identifying and resolving moral problems in healthcare contexts involves at least five steps:

1. Assessing the situation. Every effort is made to obtain all the relevant information pertaining to the case to enable a proper assessment of the nature of the problem and whether, indeed, it is a moral problem at all. Sometimes what seems like a moral problem may, in reality, be a legal problem or a clinical problem or a problem of some other practical non-moral nature.

2. Diagnosing or identifying the moral problem. The information collected is appraised and a judgment made on the nature of the problem at hand. It might be concluded on the basis of the information collected that the moral problem at hand involves a case of, for example, unethical conduct or a full-blown ethical dilemma; conversely, the problem at hand may be shown to involve little more than a breakdown in communication, hence not requiring a moral remedy per se.

3. Setting moral goals and planning an appropriate course of action. A specific plan of action is devised to resolve the moral problem(s) identified. If the problem involves a moral dilemma or a moral disagreement, then the plan of action will have as its focus, for example, an attempt to resolve the impasse that has arisen and to find a satisfactory solution; that is, one that has just and defensible moral outcomes.

4. Implementing the plan of action. The decision maker engages in the implementation of the plan of action; that is, sets the wheels in motion, as it were. Depending on the problem(s) identified, this could involve a range of actions, including reporting the matter to a supervisor or manager, and even seeking the involvement of an institutional ethics committee for advice.

5. Evaluation of moral outcomes of the actions taken. An assessment is made with respect to whether the desired moral outcomes of the actions taken were achieved. If the evaluation proves negative, then the whole situation needs to be reappraised using the same systematic process.

This model of moral decision making (see Figure 9-1) is by no means the only model that might be used to approach moral problems. Nevertheless, it is a very useful model and one that is relatively easy to use. It does, however, presuppose that decision makers have at least a working knowledge and understanding of ethics and the ability to think critically when applying ethics to and in professional practice. It would be useful at this point to briefly demonstrate how the model might be used (see Box 9-2, then read the clinical example overleaf before studying steps 1 to 5 of the discussion; consider also applying this process to the cases of Mr G and Ms Winnow, presented earlier in this chapter).

FIGURE 9-1 Moral decision making.

From Johnstone M-J 2009 Bioethics: a nursing perspective, ed 5. Sydney, Churchill Livingstone.

BOX 9-2 HOW TO PROCESS A MORAL PROBLEM

Step 1. Assess the situation and gather all the information relevant to the case; ask: What are the relevant facts of the case?

Step 2. Diagnose the moral problem; ask: What is the nature of the problem in this case?

Step 3. Set moral goals and plan a course of action aimed at achieving a morally just outcome; ask: How best can the client’s best interests (wellbeing and welfare) be maximised in this case?

Step 4. Implement the plan of action.

Step 5. Evaluate the outcome of the plan of action implemented; ask: Has the desired moral outcome been achieved in this case?

On your ward, a 35-year-old woman has been hospitalised in the final stages of a struggle with brain cancer. She is a single mother, with two young children at home. Despite treatment, the tumour continues to grow and the medical team has agreed that further treatment would be futile. You have cared for this client during past admissions, and during one especially open discussion, she expressed wishes to explore ‘do not resuscitate’ (DNR) directives. During the current admission, her medical consultant is out of town. The attending on-call doctor does not know the client personally, but he has spent some time with her. He has reviewed the clinical data and agrees that the client is entering advanced stages of her disease. In his opinion, however, the client is not ready to discuss end-of-life issues. In fact, he states that on being offered the option to discuss DNR, the client declined. You have asked him to convene a family conference to discuss DNR directives but he refuses to do so.

Clinical example discussion

STEP 1—ASSESS THE SITUATION AND ASK: WHAT ARE THE RELEVANT FACTS OF THIS CASE?

What may at first appear to be a question of ethics may not be such at all, and may be resolved by clarifying one’s knowledge base about clinical facts and reviewing policy and procedure, standards of care and so on. When it can be shown, however, that perplexing questions remain about the client’s genuine wellbeing and welfare (including her interests in not suffering unnecessarily), that the genuine needs and significant moral interests of different people are at stake and in need of protection, and that assistance is required in determining and justifying what constitutes right and wrong conduct in the situation at hand, then it is evident that a moral problem exists. The next step is to ascertain what kind of moral problem exists. This is crucial to the moral decision-making process, since unless the type of moral problem is diagnosed, any plan of action implemented risks failing to achieve a satisfactory moral outcome.

Further review of scientific data will probably not contribute to a resolution of the problem, but it is important to review the data carefully to make this determination. It is evident that there is disagreement, but this does not revolve around whether the client is in a seriously ill state, so further clinical information will not change the basic question: Should the client have an opportunity to discuss the ‘do not resuscitate’ (DNR) directive at this time? The question is perplexing. Basically, two professional team members disagree on an assessment of a client’s readiness to confront the very difficult issues around dying. The answer to the question concerning the client’s readiness has important implications for her wellbeing and welfare. If she is not ready, then raising the issues may cause anguish and fear in the client and her family. If she is ready, and the team avoids discussion, she may suffer unnecessarily in silence. If she is very close to death, then the lack of a DNR directive will necessitate the application of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) that could also result in harmful moral consequences. Knowing that CPR can cause pain and can carry devastating risks, not least the accidental rupture of internal organs, its application in a situation where further life is unlikely could prolong suffering and reduce dignity.

In assessing the situation at hand, it is necessary for the nurse to gather as much relevant information as possible. Since resolution of moral problems may arise from unlikely sources, it is helpful to incorporate as much knowledge as possible at every step of the process. At this point, the information could include looking at laboratory and test results, the clinical state of the client in question and perhaps current literature about the diagnosis or condition of the client. It may include careful investigation of the psychosocial concerns of the client and of the client’s significant others. A client’s cultural, religious and family orientation is part of the nurse’s assessment.

In this scenario, all the clinical information pertinent to the case would be obtained. It might be helpful to determine if the client retains most cognitive functions, even though her brain tumour is aggressive. A review with the attending medical consultant might result in agreement that she is fully competent, but definitely afraid and overwhelmed by the prognosis. Since the problem seems to exist because two professionals do not agree on a client’s state of mind, it may be helpful to reassess the client, or even to request that an independent person assess the client’s readiness to discuss end-of-life issues. Sometimes, family members or significant other people in the client’s life will hold important clues to a client’s state of mind and also how best to approach a given situation in a culturally informed and appropriate manner. In addition to this, the moral standards that are guiding the decision making should be clarified. What might be at issue in this case is a moral disagreement about the appropriateness of appealing to and applying the respective moral principles of autonomy and non-maleficence. Thus, what might initially look like a disagreement in professional opinion may in fact be much more than that—it may also involve a fundamental disagreement in moral viewpoint, or moral disagreement.

STEP 2—DIAGNOSE THE MORAL PROBLEM

Once the nurse is satisfied that the problem is a moral problem rather than some other kind of problem, for example a disagreement about the client’s health status which could be clarified by appeal to the clinical facts of the case, then it becomes necessary to make a more definitive moral diagnosis. The possibilities, as have been shown above, can include one or more of the following:

The clinical example meets the criteria for a moral problem. However, a more definitive moral diagnosis is needed. One possibility is that this case exemplifies a moral disagreement, since both doctor and nurse share a common moral commitment to preventing harm to the client but disagree on how this harm-prevention might be achieved—the doctor believes that imposing unwanted information (though crucial to informed decision making) on the client could result in her being caused unnecessary harm, whereas the nurse believes that withholding the information could likewise result in her being caused unnecessary harm. This situation could also be said to pose an ethical dilemma, since both doctor and nurse are situated between ‘a rock and a hard place’ and confronted by the question, ‘What ought I to do?’ Further information about the case might result in still other moral diagnoses being made.

STEP 3—SETTING MORAL GOALS AND PLANNING ACTION

Once all the relevant information has been gathered and a correct moral diagnosis made, attention can then shift to more specific questions such as: Should this client discuss the DNR directive at this time? What are the benefits and what constitute the risks of a DNR order at this time? An important question also seems to involve the client’s current state of mind: Is she afraid to speak? Is she feeling cut off from her normal network, including her medical consultant? Are these feelings contributing to confusion about DNR decisions? Has she been approached in a culturally informed and appropriate (culturally competent) manner?