Chapter 18 Caring for families

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Discuss the diversity in family structure and characteristics in Australian and New Zealand society.

• Explore theoretical approaches to the study of families.

• Begin to explore approaches to family nursing care.

• Explore your own values and beliefs about families.

• Recognise the benefits and challenges in working with diverse families.

• Discuss strategies that you can use to manage your own responses to working with families.

Families are both universal and diverse. While we were all born into a family, the perceptions of ‘family’ vary greatly between people from different social and cultural backgrounds. Although Australian and New Zealand families have become smaller and more diverse in structure in recent decades, family continues to fulfil important social roles and functions. In this chapter, you will explore the current situation of families in the Australian and New Zealand context, and begin to think about families in healthcare.

What is a family?

Well, it depends on who you are asking, where you are, and even which time in history that the question is asked! Many people may initially respond with a description of their own family. But as we think about families more deeply, we soon start to see that there is more variation to family structure than that by which we define our own family. There is significant diversity in terms of biological, legal or socially constructed relationships, marital status, relationships with extended family and social networks, and more. For some people, family would only include those people related to them by birth or marriage. For others, family may included long-term friends, household members or pets. While as individuals we may have a strong sense of family, organisations and legal statutes can have different definitions to our own. These legally or organisational constructed definitions can determine access to resources and information—such as taxation, superannuation and access to social welfare benefits.

As you would expect, then, there is no single universal definition of a family, especially as family can vary so much in structure. One example of a definition is provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2009):

Two or more persons, one of whom is aged 15 years or over, who are related by blood, marriage (registered or de facto), adoption, step or fostering; and who are usually resident in the same household.

FIGURE 18-1 Family celebrations and traditions strengthen the role of the family.

Image: iStockphoto/Mark Bowden.

TABLE 18-1 KEY THEORIES AND MODELS INFLUENCING FAMILY NURSING

| THEORY | FOCUS |

|---|---|

| Family systems theory | Interactions among members of the family or between the family and their environment, which may result in either functional or dysfunctional outcomes |

| Developmental theory | The life cycle of families; stages of family development |

| Family cycle of health and illness | Cyclical model that describes common patterns of stress, reaction and adaptation to families when members become ill |

| Structural functional theory | Families as an institution; how they function to maintain family and social networks |

| Family stress theory | Analysis of how families experience and cope with stressful life events |

Adapted from Kaakinen JR and others 2010 Family health care nursing. Theory, practice and research, ed 4. Philadelphia, F.A. Davis.

Note that the ABS definition includes residence in the same household as one of the boundaries for defining family. For many people, family includes people who may reside in another household, so it is important to bear in mind when reviewing census data that information on families is based on the household composition, rather than on who the individual person considers to be their family (Cotterell and others, 2008).

In addition to considering what structure a family might take, it is important to think about what it is that families do. Most families have some shared core functions, including maintaining wellbeing and a sense of belonging to individuals in the family group, raising children, establishing group values, sharing financial and material resources and passing on knowledge of the culture and values of the group to the next generation (Families Commission, 2008; Kaakinen and others, 2010). Importantly for nurses, families often function as healthcare providers. Family members will often provide direct care to other members, and families have values and beliefs about lifestyle that may enhance or endanger health. Although these functions may be common to many families, the extent to which functions are seen as important and what is considered successful family functioning varies according to the cultural background of the family and their shared values and beliefs. It is also important to consider that not all families fulfil these roles and expectations.

Trends in family structure and function in Australia and New Zealand

Now that we have clarified that families vary according to individual, organisational, social and legal contexts, it is useful to consider the patterns of family groups that are present in our society (see Box 18-1 and Working with diversity). We would probably agree that the traditional structure of the predominantly white Anglo-Saxon populations in Australian and New Zealand families has been the nuclear family—consisting of a married couple with children. As the population has aged, social values regarding relationships and marriage have changed and migration has increased, and there is greater diversity in family structure and household composition than before. The range of family structures now includes couples living with or without children, single parents, separated parents who share care of their children across two households, blended families, same-sex couples with or without children, single people living alone or in groups, and extended families who may live in one or more households (Australian Government, 2008; Families Commission, 2008). At an international level, migration has influenced the structure of families and has contributed to a much more diverse and multicultural society. This change has implications for both family structure and the social expectations of families (de Vaus, 2005).

BOX 18-1 KEY CONCEPTS: DIVERSITY IN FAMILY STRUCTURES

EXTENDED FAMILY

The extended family includes relatives (aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins) in addition to the nuclear family.

SINGLE-PARENT FAMILY

The single-parent family is formed when one parent leaves the nuclear family because of death, divorce or desertion, or when a single person decides to have or adopt a child.

BLENDED FAMILY

The blended family is formed when parents bring unrelated children from prior or foster-parenting relationships into a new, joint-living situation.

ALTERNATIVE PATTERNS OF RELATIONSHIPS

These relationships include group households, ‘skip-generation’ families (grandparents caring for grandchildren), communal groups with children, ‘non-families’ (adults living alone), related individuals residing in the same household, but not in a couple or parent–child relationship, cohabitating partners, and same-sex couples.

In addition to the social changes that may take place, the structure of a family will vary as circumstances change during the lifespan of individuals. In recent decades, the structure of New Zealand and Australian families has become more variable as the aged population increases, in addition to the change in relationship formation (Australian Government, 2008; Families Commission, 2008). Relationship changes are more likely to affect living arrangements, family size is getting smaller, marriage is less frequent and more people live alone (particularly the elderly). Even so, most children are still born into and grow up in a family with two resident parents, most people will marry and most stay married to their first partner (Australian Government, 2008).

Single households are the fastest-growing household type. In Australia and New Zealand the number of people living alone has increased to nearly 23% (Australian Government, 2008; Statistics New Zealand, 2006). This increase is a function of both an ageing population and a falling birth rate. Men and women are living longer, children are staying at home longer, couples are marrying later, and women are delaying childbirth or not having children at all.

The fastest-growing age group is 65 years of age and older, and the ageing population has had a significant impact on family life. Many more middle-aged people are balancing the need to raise their own children while caring for ageing parents. Likewise, grandparents are often involved in the care of grandchildren to enable both parents to return to the workforce (Breheny and Stephens, 2007). However, both Australian and New Zealand Indigenous populations have a shorter life span than the population average (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006; Statistics New Zealand, 2006). As a result, Indigenous families may have less social support from their elders than other families. Furthermore, migrant families are often separated from their extended family members and thus have diminished sources of social support.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

New Zealand readers will be familiar with the word Whaānau, a Māri word often used to describe family, including immediate and extended family. However, the word Whaānau can have different meaning and interpretations (Cunningham and others, 2005; Walker, 2006). For example, whakapapa Whaānau refers to people related through shared ancestry, and therefore encompasses more than just immediate and extended family members. In recent times, Whaānau has also been used to describe a group of people joined together through a common bond or shared purpose (kaupapa Whaānau) (Cunningham and others, 2005).

A recent New Zealand strategy to improve healthcare has been through Whaānau ora, a philosophy of care that recognises the importance of family in health. Whaānau ora interventions have been developed to provide support to families, particularly those with chronic physical or mental health illness. For example, some Māri healthcare providers have begun to employ Whaānau ora workers to support families with chronic physical or mental health illnesses (Boulton and others, 2009; Kidd and others, 2010).

Whaānau services have been established at some hospitals in New Zealand. These services provide social and practical support such as accommodation, and usually operate under Māri tikanga (protocol).

Boulton AF and others 2009 Realising whanau ora through community action: the role of Maori community health workers. Educ Health 22(2):188; Cunningham C and others 2005 Analysis of the characteristics of Whaānau in Aotearoa. Wellington, Research Centre for Māri Health and Development at Massey University. Online. Available at www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/33494/characteristics-of-whanau-31-may-2005-final.pdf 3 Mar 2011; Kidd J and others 2010 A whanau ora approach to health care for Maori. J Primary Health Care 2(2):163–4; Walker T 2006 Whaānau is Whaānau. Wellington, Families Commission/Ko–mihana a– Whaānau. Online. Available at www.nzfamilies.org.nz/sites/default/files/downloads/BS-whanau-is-whanau.pdf 3 Mar 2011.

The fertility rate has increased slightly in recent years to almost two babies per woman (Australian Government, 2008; Statistics New Zealand, 2006). However, the median age of childbearing has increased to approximately 30 years of age and approximately one in five women may not have children (Australian Government, 2008). In general, women from lower socioeconomic areas and Indigenous women are likely to have more children and at a younger age than others (Australian Government, 2008; Cotterell and others, 2008). While the rate of adolescent pregnancy has declined, Australia and New Zealand continue to have relatively high rates of teen pregnancy compared with other developed countries (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2008).

Couple relationships have changed as the social circumstances for women have changed and social views of sexuality have broadened. Most women with dependent children have employment outside the home, and this has meant that more children require care outside the family (Australian Government, 2008; Families Commission, 2008). As families with children have become increasingly dependent on two incomes, the role of fathers in Western developed nations has changed. More fathers now take leave when their child is born, and more are caring for their child(ren) while the mother is working (Featherstone, 2009; Hosking and others, 2010). Although fathers are increasingly involved in childcare, working and non-working women with children still carry a significantly higher burden of responsibility for household work than fathers (Craig and Mullan, 2010; Craig and others, 2010). Although homosexual couples are still unable to marry by law, many couples form family households through cohabitation. Some homosexual families have children through adoption, fostering, assisted reproduction techniques or from previous relationships. Furthermore, an increasingly diverse and multicultural population means that there is considerable variation in the beliefs regarding parenting, expectations of child behaviour and child-rearing practices (Wise and da Silva, 2007).

As the rate of separation and divorce has increased over the last 40 years, the number of single-parent households has increased. As at 2006, 11% of all families in Australia and 10% of households in New Zealand were single-parent families (Australian Government, 2008; Families Commission, 2008). The majority of single-parent families are headed by women (Australian Government, 2008; Families Commission, 2008). Single-parent families face economic challenges. Although one-parent families represent approximately 7% of all households in Australia, they represent about 17% of the lowest-wealth households, are more likely to be reliant on government-funded pensions for income and are more likely to be unemployed (Australian Government, 2008). Even when single parents do work, they are more likely to have worse economic outcomes, primarily due to the lack of a second household income (Australian Government, 2008).

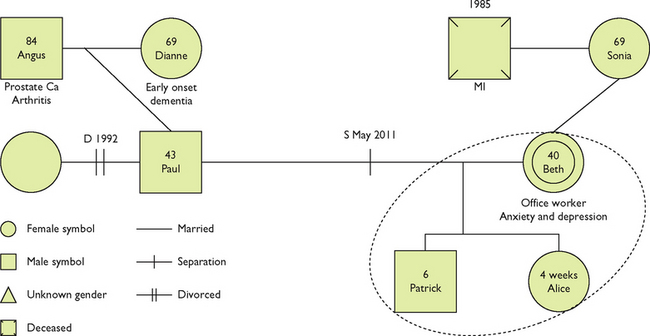

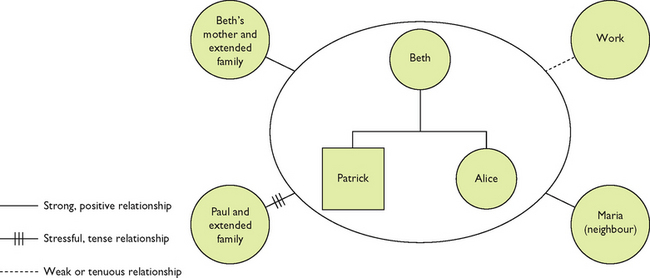

Family theory and models

Family theories and models can give us a better understanding of different aspects, views or contexts of families in health and illness. Family theories have their origin in the social sciences field but have often been applied to family nursing practice and research. There is no single theory that has universal application—rather, each is a way of looking at families from a particular viewpoint. While drawing on a range of theories to explain family responses to health and illness provides us with a rich basis for research and practice, the myriad of different theories and models can make theoretical concepts of family very confusing for students. For clarity, the focus in this chapter will be limited to an introduction to three key family theories or models—family systems theory, family developmental theory, and the family cycle of health and illness model—that you might be asked to review as part of your studies or which may be useful to your nursing practice. As you review each theory or model, you will see that the concepts can be similar.

Family systems theory

Systems theory has been a significant influence in social sciences and family therapy. A systems approach means that we view the family as a whole system, or as individuals within a system who interact and are interdependent (Kaakinen and others, 2010; Wright and Leahey, 2009). An important premise of family systems theory is that the system (family) strives for balance and stability, either through adaptive or maladaptive methods. This approach allows healthcare professionals to visualise individual members of the family as participants in the family group; however, the emphasis when using family systems theory is still on achieving stability in the system, rather than on the needs of the individual.

Several key concepts underpin family systems theory (Kaakinen and others, 2010; Wright and Leahey, 2009). All parts of the system (family) are interconnected. So if one family member is unwell, this has implications for all family members. The family as a whole is composed of more than the sum of its parts. All families have some forms of boundaries between them and the environment. These boundaries may be open or closed to the environment (or community). Finally, systems can be subdivided into subsystems, so healthcare professionals may focus on subsystems within a family (such as mother to child or partner to partner relations).

Family developmental theory

Family developmental theory describes how the role and structure of families change throughout the life span. Similarly to life-span developmental theories, as families develop they need to achieve certain ‘milestones’ before they can move on to the next stage. The original developmental theory was developed by Duvall (1977, 1985, cited by Kaakinen and others, 2010). Subsequently the model was expanded by Carter and McGoldrick (1999) in recognition of the social changes that families were experiencing, particularly from heterosexual marriage-based relationships to greater diversity in the formation and legal recognition of couple relationships.

Key concepts underpin family developmental theory (Kaakinen and others, 2010). Families experience change over time. These changes are often related to the changing social roles as families change, are fairly predictable and bring similar stresses. For example, the role changes from being a couple to becoming parents. Families experience transitions from one stage to another, and these transitions can result in stress and redefining of relationships and understanding of what family is (Carter and McGoldrick, 1999).

Family cycle of health and illness model

The family cycle of health and illness model was initially developed to help clarify family experience with health and illness over time, and as an organiser for family and health literature (Doherty, 1991; Kaakinen and others, 2010). It includes a number of phases that relate to illness within families, including health promotion and risk reduction, vulnerability and symptom experience, sick role and family appraisal, medical contact and diagnosis, adjustment and reorganisation. Interestingly, the phases of the model are linked to family systems theory and family developmental theory, as well as to others. For example, the phase of health promotion and risk reduction draws on family systems theory and family developmental theory. Family systems theory can help to explain why lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise become part of family patterns of behaviour, while family development theory helps to explain why families adopt different approaches to managing stress as their social roles change (Doherty, 1991; Kaakinen and others, 2010).

Family theory and models: how does this link to nursing?

As you have read through this section, you may have started to get some idea of how these concepts might be used as frameworks for nursing assessment, intervention with families or for research to explain family responses to illness or for organising nursing practice. Family systems theory is often used to guide nursing practice in the organisation of nursing care to include families, and in research that explores how the family interacts with other systems, such as a hospital. For example, family systems theory has been used as a framework for research into parental needs and expertise in caring for a child with a chronic illness in a hospital setting (Balling and McCubbin, 2001). Developmental family theories are often used as frameworks for the study and practice of healthcare for families at different life stages, such as transition to parenting and adjustment to illness across the life span. For example, in a study of distress and perception of illness intrusion for parents of young people with juvenile rheumatic diseases, family life cycle was used as a model to explain family adjustment to childhood chronic diseases as children reached different ages (Andrews and others, 2009).

Family-centred care

The importance of family has been increasingly acknowledged in the development of healthcare services across all disciplines. The recognition of family as important has led to the development of models of care. Patient-centred care and family-centred care are terms that have been used to encompass multidisciplinary models of care or service delivery that focus on the family. In the past the patient- and family-centred care approach has been used predominantly in child healthcare; however, more recently the principles have been adapted and applied more widely, and the terminology of patient-centred care has been added to the mix. As a result, there is some confusion around the terms and what they mean to people in different contexts. For the purposes of clarity, the focus in this chapter will be on the principles of family-centred care.

There are a number of definitions of family-centred care. Many have been adapted to best suit the context in which family-centred care operates. A broad definition that focuses on a system-wide approach to patient- and family-centred care is provided by the US-based Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (2010):

an approach to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care that is grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among health care providers, patients, and families … that shapes policies, programs, facility design, and staff day-to-day interactions.

Family-centred care recognises that the healthcare of a patient happens within the context of their family, and that therefore the family is a key stakeholder in healthcare (Kaakinen and others, 2010; Shields and others, 2007). In a healthcare service that is family-centred, the focus on families extends through every facet of the work that the services undertakes—from the way in which healthcare professionals work in partnership with families, to the building itself! If you think that sounds good in theory but potentially challenging to achieve in reality, you are right. As a result, the feasibility and outcomes of family-centred care remain controversial, and to date most research has been limited to developed Western countries (Foster and others, 2010; Shields, 2010; Shields and others, 2007).

The interest in family-centred care first developed in relation to the care of children in hospitals. Changing social values in relation to children, and research into the effects of separation, led to increased involvement of families in the care of children in hospital (Jolley and Shields, 2009). Over time, it has become widely accepted that the benefits of involving families in healthcare can be applied to people of all ages, not just children. Young people, adults and elderly people have greater autonomy in healthcare than children do, and therefore the term ‘patient-centred’ is used to make the role of patients more explicit while also ensuring that families are still included in the design and delivery of healthcare (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, 2010).

FIGURE 18-2 Observing family interactions between individuals within families assists in understanding family functioning.

Image: Joki/Science Photo Library.

Additionally, there are situations where family circumstances may detract from the health and wellbeing of an individual. A common example is that of a child who has been abused (Wilson and others, 2004). In such circumstances, the focus on a patient-centred approach to maintain the safety of the child, rather than family-centred care, may be more appropriate in the first instance.

There are four key principles that underpin a patient- and family-centred approach to care (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, 2010):

1. Respect and dignity. Healthcare practitioners listen to and honour patient and family perspectives and choices. Patient and family knowledge, values, beliefs and cultural backgrounds are incorporated into the planning and delivery of care.

2. Information sharing. Healthcare practitioners communicate and share complete and unbiased information with patients and families in ways that are affirming and useful. Patients and families receive timely, complete, and accurate information in order to effectively participate in care and decision making.

3. Participation. Patients and families are encouraged and supported in participating in care and decision making at the level they choose.

4. Collaboration. Patients and families are also included on an institution-wide basis. Healthcare leaders collaborate with patients and families in policy and program development, implementation and evaluation; in healthcare facility design; and in professional education, as well as in the delivery of care.

The research highlight below reports a systematic review of the best evidence related to positive relationships between aged-care residents, families and staff members. You might notice that the findings from the study have similarities with the four key principles of family-centred care!

TABLE 18-2 THE FAMILY LIFE CYCLE

Adapted from Carter EA, McGoldrick M 1999 The expanded family life cycle: individual, family and social perspectives. Boston, Allyn & Bacon.

Research focus

Working with clients and their families is a critical element of aged-care nursing practice. This paper provides evidence of ways in which positive staff and family relationships can be achieved in aged-care settings.

Method

The purpose of this systematic review was to present the most recent and best evidence of factors related to staff–family relationships in institutional aged care. Studies were included in the review if their participants included residents or patients within acute, subacute, rehabilitation and residential settings who were aged over 65 years, their relatives and staff members of the facility. Intervention studies were included if they used strategies and practices within the facility to promote constructive relationships and organisational characteristics. Outcome measures of interest for the review included perceptions of staff–family relationships, staff outcomes (e.g. stress, relationship and job satisfaction, retention), and family and resident satisfaction. Searches of relevant electronic databases using key search terms were performed. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were obtained and reviewed. Data were extracted using standardised tools. Quantitative data were not appropriate for meta-analysis; therefore the studies were reported in narrative. Thematic analysis of the interpretive and critical papers were performed. Results were categorised and then aggregated to produce final results.

Results

A total of 50 studies were reviewed, including 35 from the earlier review and 15 from the updated review. The majority of studies that were included were qualitative. In-depth interviews were the most common method of data collection, and thematic or content analysis was most commonly used for analysis. The updated review supported findings from the first review. In addition, the updated review highlighted that factors important to effective relationships included monitoring of care, involving families in decision making, upholding the uniqueness of the individual older person, promotion of trust, the multidisciplinary team and family dynamics.

Evidence-based practice

• There are a range of contextual, organisational and individual factors that influence staff–family relationships in aged-care settings.

• Individual characteristics that are most important to the development of positive staff–family relationships are respect, trust, familiarity and empathy.

• Interventions that promote positive staff–family relationships are those that promote collaboration in care planning and decision making; promote effective communication skills; have a clear process; and involve the multidisciplinary team.

• Organisational and management support for these interventions is essential for their success.