Chapter 22 Older adulthood

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Describe common myths and stereotypes about older adults.

• Discuss the significance of nurses’ attitudes towards older adults.

• Describe the types of community-based and institutional healthcare services available to older adults.

• Describe some of the biological and psychosocial theories of ageing.

• Discuss common developmental tasks of older adults.

• Discuss common physiological changes of ageing.

• Discuss the common health issues experienced by older adults.

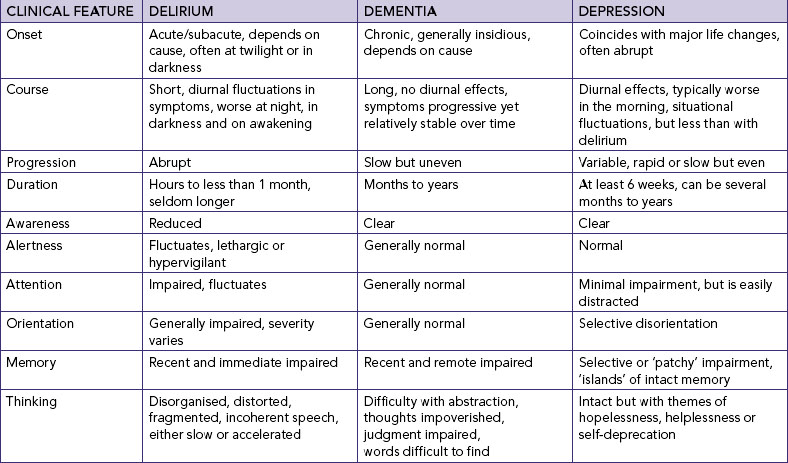

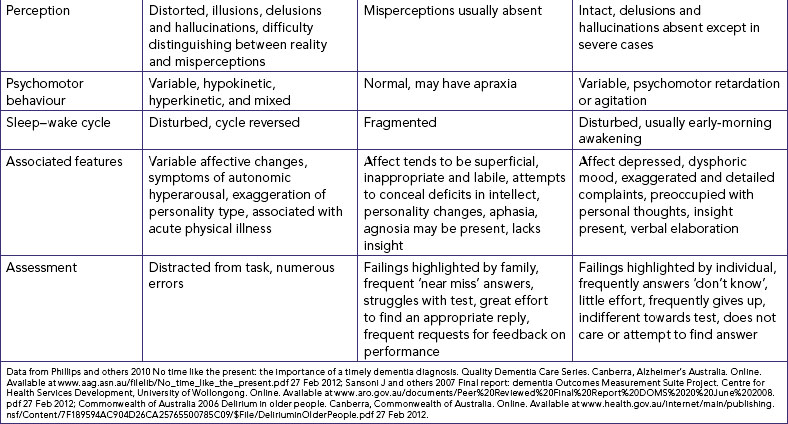

• Differentiate between delirium, dementia and depression.

• Discuss issues related to psychosocial changes of ageing.

• Identify nursing interventions related to the physiological, cognitive and psychosocial changes of ageing.

Unlike other life stages, it is not clear when older adulthood begins. Many people find themselves described as ‘older’ from 50 years, and travel and shopping concessions generally begin at 55 years. In the past, retirement from work has been used as a marker of older adulthood; traditionally at 65 years. However, being retired is not a useful indicator of older adulthood. With the introduction of superannuation schemes, many people have been able to retire at 55 years or earlier; while others, because of their good health and interest in their work, have delayed retirement. More recently, changes in world economics have resulted in a decrease in savings as well as anxiety that savings will not fund a lengthy aged period, causing many older adults to either stay within the workforce or return to part- or full-time work.

Both Australian and New Zealand planners use 65 years and over as a basis for planning health and welfare services. The population characteristics of both countries are changing, with more people living into older age. For some years there have been warnings that both countries will be challenged by the growing numbers of older people and their need for services, with public debate about how services should be funded. While the number of older people is growing as a proportion of the population of both countries, it is important to remember that the majority of older people have active and productive lives which are generally healthier than in previous generations (Figure 22-1).

The challenge for healthcare professionals is the scope of older adulthood, which can span 40-plus years and can include older people who are healthy and those who have high levels of disability. Consequently, the group of people known as ‘older adults’ in today’s Australian and New Zealand societies must be considered a heterogeneous group; it is very difficult to make generalisations about their needs. Family circumstances, physical abilities, economic circumstances and health and welfare service needs are likely to vary greatly among people of 65–90+ years. The need for welfare support and health services increase dramatically over the age of 85 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010).

Older adults are the recipients of care in all health-delivery settings: community care, rehabilitation, acute care, specialised outpatient clinics, residential aged care and palliative care. It is important, therefore, for healthcare professionals to understand the diversity of older people and their needs, and to work with older people to ensure that the services provided are appropriate. Given the increasing emphasis on quality and safety as part of service provision, it is also important that healthcare professionals are aware of the special needs of older adults and tailor their care accordingly.

Working with older adults—gerontology as a specialty area

While nursing of older adults is increasingly recognised as a specialty area, most nurses who work with older people identify themselves as working in a specific care context, for example rehabilitation, community care or residential aged care. Some nurses identify themselves as specialising in specific conditions common in older adults, for example dementia care or continence promotion. Knowledge of the most frequently used terms and their definitions clarifies the differences and improves communication.

Geriatrics is the branch of medicine dealing with the illness of old age; it is concerned with the physiological and psychological aspects of ageing and with diagnosis and treatment of diseases affecting older adults. Gerontology is the study of all aspects of the ageing process and its consequences. Gerontological nursing, a term frequently used in Australia and New Zealand, is concerned with assessment of the health and functional status of older adults; diagnosis, planning and implementing of healthcare and services to meet the identified needs; and evaluating the effectiveness of such care, and can encompass personal care, restorative and rehabilitation as well as end-of-life care. Gerontic nursing is a term often used in the international literature and interchangeably with gerontological nursing.

Increasingly there is acceptance that working with older adults is a challenging area of work that demands skilful and knowledgeable nurses. Given the age range and variability of issues that an older adult might experience, an understanding of how older people relate to society as well as knowledge of ageing and of the common health issues experienced by older people is necessary for clinical decision making.

Older adults as part of our population

Population ageing is a notable demographic characteristic of most developed countries. Both the Australian and the New Zealand populations are ageing numerically in that the numbers of older people are increasing, and structurally in that the proportion of people aged over 65 years is rising (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008; Statistics New Zealand, 2009). Consequently, the age composition of both countries is projected to change considerably as a result of population ageing. It is projected that by 2056 there will be a greater proportion of people aged 65 years and over and a lower proportion of people aged under 15 years in both Australia and New Zealand (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008; Statistics New Zealand, 2009). For example, it is projected that one in five New Zealanders will be aged 65+ years by 2031, compared with one in eight in 2009 (Statistics New Zealand, 2009).

The main factors affecting the ageing of Australia’s and New Zealand’s populations is the sustained low birth rates combined with low mortality rates, resulting in increasing life expectancy at birth. Improved living conditions and healthier lifestyles as well as medical advances over various forms of diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease, have greatly affected life expectancy (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). However, unlike New Zealand where life expectancy is reasonably uniform, life expectancy is not uniform across populations within Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a much lower life expectancy than the general Australian population. The estimated life expectancy for Indigenous males is about 12 years less than that of non-Indigenous males; for Indigenous females the gap is approximately 10 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011). In addition, the incidence of ill-health for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is higher than that of non-Indigenous people, for example higher levels of injury, diabetes, kidney disease and psychological distress (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011). Overall, those who are disadvantaged or are from lower socioeconomic groups will experience lower health status.

Both Australia and New Zealand have had active migration programs, and consequently the populations of both countries are diverse. Overseas-born people in both countries have a lower death rate in most of the major causes of death, and overall experience as good as, if not better, health than that of native-born people. In general, immigrant populations have a lower rate of death and hospitalisation as well as lower rates of disability. Known as the ‘healthy migrant effect’, it has been hypothesised that the general good health and the resulting longer life span of overseas-born people is a result of the selection processes for migration which favour people with good health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011). However, both Australia and New Zealand have accepted vulnerable people as refugees; the life expectancy of these people may prove to be not as high as other migrants.

Education, supportive personal and social environments, good medical care and superannuation entitlements all contribute to better life chances in old age and to the likelihood of maintaining good health into advanced age. Increasingly, there is an emphasis on older people continuing to be active members of their communities, with the health authorities of both New Zealand and Australia undertaking health-promotion campaigns focusing on healthy eating and the promotion of regular exercise, as well as encouraging being socially involved. Healthy ageing describes the ongoing activities and behaviours that each person undertakes to reduce the risk of illness and disease, with the result of an increase in physical, emotional and mental health. It also means combating illness and disease, resulting in a faster and more enduring recovery. Accessing healthcare, ‘navigating the system’ and participating in healthy ageing activities may be difficult for people with English as a second language.

There is a common misperception that older people are dependent and live in residential aged care. However, although the proportion of older people living in non-private dwellings increases with age, the reality is that the majority of older people live in private dwellings either with a partner or as part of a family household, or as a member of a group, or alone; only 8% of older people in Australia are estimated to live in non-private dwellings, including private hostels or hotels, guest houses and residential aged care. There is a similar picture in New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, 2009). The likelihood of living alone increases with age, with almost half of those aged 85 years and over living in lone-person households (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009; Statistics New Zealand, 2009). The policies of successive governments of both New Zealand and Australia have focused on community care, and increasingly older people with disability or impaired health are able to be supported in the community. Consequently, those living in residential aged care tend to be older, with the majority being over 75 years, and have a greater level of disability and ill-health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010; Statistics New Zealand, 2009).

The majority of older people continue to make valuable contributions to their families and to society. People aged 55 years and over provide a substantial proportion of volunteer hours (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009; Statistics New Zealand, 2009), and therefore contribute to the economic, political, social and cultural life of society. In addition, older people provide the majority of the informal caring for friends and family, including children, people with disabilities, and other older people (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). A recent phenomenon is the increasing number of grandparents who are taking on the parenting role. Because of family complications such as death, divorce, substance abuse, incarceration, abandonment, ill-health (for example AIDS) and child abuse, many grandparents are raising (parenting) their grandchildren.

Both in New Zealand and in Australia there are older people who use the time following retirement for travelling—the ‘Grey Nomads’—or to change their way of life and move to either the country or the coast and begin a new phase of their lives. Future ideas of old age and the role that older people play in society is probably about to change as we see increasing numbers of ‘Baby Boomers’—those born between 1946 and 1961—reach retirement age. It has been suggested that this group have seen what has been offered by society to their parents, and want something else for themselves (Hunt, 2007). This large cohort of people are said to have redefined a number of age stages as they have passed through them, and come with their own ideas as to what is acceptable in terms of access to services and attitudes of healthcare professionals. It is to be expected that they will also change how older age is defined.

Ageism

The introduction of the term ageism is attributed to Robert Butler, who first used the term in 1969 to describe the process of stereotyping and discriminating against people because they are old (Butler, 1969). The United Nations has identified three types of security needed in late life: human capital (health, work skills and self-knowledge); social capital (family and community networks); and economic capital (savings and pension plans). Programs to eradicate poverty, unemployment and social exclusion are needed to help people balance these resources, as well as access to financial services and safeguards from physical, mental and financial abuse (United Nations, 2010a). Ageism is seen as a barrier to these programs and, in the opinion of the United Nations, must be eradicated. Indicators of ageism in the broader community include myths, stereotyping and negative attitudes towards older people (Table 22-1).

TABLE 22-1 MYTHS ABOUT OLDER ADULTS

| MISCONCEPTION |

REALITY |

| All old people are senile |

Senility is an outdated term and is definitely not part of normal ageing

Memory problems are a feature of some disease processes e.g. Alzheimer’s disease

|

| Older people are preoccupied with dying |

Older people do think about mortality, as do people of all ages |

| Older people cannot learn new skills |

This is a variation on ‘you can’t teach an old dog new tricks’. Many older people enjoy learning, as testified to by the numbers of older people who enrol in university courses and local adult education activities. Older people are also among the ‘early adopters’ of new technology, particularly the use of the internet and communication devices such as Skype |

| Most older people live in nursing homes |

The majority of older people live in the community in private dwellings rather than in institutions |

| Older people are not interested in sex |

Many older people remain very interested in sex and seek ways to express their sensuality and sexuality. This remains a challenge to younger people and healthcare professionals who often do not wish to explore this area of healthcare |

| Older people are a burden on society |

The majority of older people lead productive, independent lives. They participate in all areas of society, including undertaking the bulk of volunteer work

Over half of older people aged 85+ years live alone, maintaining their own day-to-day care needs

|

Nay R, Garratt S 2009 Older people: issues and innovations in care, ed 3. Sydney, Churchill Livingstone; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2011 Australia’s welfare 2011, Cat. no. AUS 142. Canberra, AIHW. Online. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737420537 27 Feb 2012.

• CRITICAL THINKING

You may know older adults as members of their family—is the older adult disabled, or physically well? Would you consider them active members of their family, despite any disability?

Consider for a moment the last time you were working in a healthcare setting with a client who was an older person. Do your expectations of older people affect how you talk and interact with them?

Myths and stereotyping of older adults continue, despite ongoing research in the field of gerontology that continually shows the majority of older adults are not ill, disabled or dependent. For example, a common misconception is that older adults are not interested in sex and that any interest in sexual activities is abnormal and should be discouraged. Yet older adults report continued enjoyment of sexual relationships (Bauer and others, 2009) (Box 22-1). A study of sexuality and health among older adults illustrates that part of the problem for many older adults is their reluctance to discuss sexual issues with healthcare professionals, possibly because of a fear of disapproval (Lindua and others, 2007).

BOX 22-1 SEX AND SEXUALITY

• Research has consistently shown that sexual activity remains important for many older people.

• With reasonable health and a partner, sexual relations are possible into the 9th decade of life.

• Sexual drive varies with each person, and in each person, from time to time.

• Not all older people are heterosexual.

• Not all older people want to be sexually active and those that do may choose to express their sexuality in a range of ways.

• Denial of an individual’s sexuality is an infringement on that individual’s human rights.

• Sexual problems are frequent among older adults, but these problems are infrequently discussed with healthcare professionals.

Bauer M and others 2009 Sexuality and the reluctant health professional. In Nay R and Garratt S, editors, Older people issues and innovations in care, ed 3. Sydney, Churchill Livingstone; Lindua ST and others 2007 A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the US. N Engl J Med 357:762–74; United Nations 1948 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Geneva, United Nations. Online. Available at www.un.org/en/documents/udhr 27 Feb 2012.

Nurses have identified teaching an older adult how to manage their health concerns as an accepted part of their role (Kelley and Abraham, 2007). Although the process of learning may be affected by age-related changes in vision or hearing or by reduced energy and endurance, older adults are lifelong learners. Importantly, the benefit for an older adult in taking part in health-promotion activities is usually quite high. There is evidence that activities which encourage healthy eating, increased physical activity, smoking cessation and increased social inclusion are very successful with older adults (Haber, 2007). The nurse who understands older people will use teaching techniques that compensate for sensory changes, provide additional time for remembering and responding, and draw on the older adult’s past experiences. Like people of all ages, it is important to provide health-promotion messages that correspond to the identified interests of the older adult, rather than to the areas believed important by the healthcare professional.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Take a moment to consider the health-promotion activities that are currently on offer to older adults in the community in which you live. You may not be aware of all of them—many health-promotion activities are offered through the local bowling club, golf club or local art centre as well as the local community centre and public library.

What activities do you recommend to your older clients as part of their ongoing health promotion? Do you advise a varied set of activities?

The general perception of older adults in Australia and New Zealand and how much they are valued in society is mixed. On the one hand, older people are considered to be sources of valuable knowledge, experience and support. On the other hand, they are often considered invisible within the community. Older people tend to see age as a relative term. The main discriminators are the state of mind of the individual, their quality of life and their state of health.

Older people have expressed concerns about the use of unrealistic stereotypes in the media, with older people frequently depicted as frail, defenceless victims described in terms of dependency. These negative images portrayed by the media can undermine older people’s self-confidence and the confidence that younger people have in them. The United Nations has identified the media as being a principal agent for eradicating ageism by showing older people as being capable, rich in experience and history and independent in thought and action.

The attitudes held by healthcare professionals affect the type and standard of care provided to older adults. At times, institutional settings such as hospitals and residential aged-care facilities have treated older adults as objects to be acted on, rather than independent, dignified adults. The contemporary view is to involve older people in all decisions about their care. Nurses, because of the nature of their interactions with clients, are in a unique position to encourage and reinforce a positive self-image on behalf of an older person.

Abuse of the elderly

Abuse of the elderly—the poor behaviours of trusted people such as family members or caregivers towards an older person or their carers—is a significant social issue. Abuse of an older adult is often not recognised or acknowledged. Abuse may be directed towards an older person or the carer and can take different forms: physical, psychological, financial, sexual or neglect. It can include:

• physical and chemical restraint

• over-medication

• actions which show lack of respect

• hitting, slapping, pushing

• threats, humiliation, bullying

• swearing

• treating as a child

• name-calling

• denying right to money

• misappropriating money/valuables

• sexual teasing, innuendo or inappropriate/unwanted touching

• sexual assault

• failure to provide food/fluid/hygiene/personal care

• neglect/avoidance

• ignorance leading to mistreatment.

Abuse of an older adult is thought to be under-reported, and consequently the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that screening for abuse should be included in all areas of care delivery, particularly primary care (Perel-Levin, 2008). There may be many reasons for an older adult not to report abuse, including feelings of shame to admit that a person close to them mistreats them, or blaming themselves and thinking it is their fault. They may also be worried about what other people might think, or think that people might not believe them; they may also be frightened of what might happen to them if they tell someone about their situation. It is important to note that there is legislation in both Australia and New Zealand that makes abuse of any person illegal.

Care issues that have been found to increase the risk of abuse occurring are:

• social isolation of the older person or their carers

• language and cultural barriers

• a family member who is financially dependent on the older person

• a carer with addiction or mental illness

• a carer experiencing significant stress (Perel-Levin, 2008).

• CRITICAL THINKING

The WHO considers that abuse of older people is a common problem. In the care setting where you work, what cues could indicate that an older client might be experiencing abuse? Would you be alert to the potential?

There is a fine line between abuse and poor-quality care. The language used by healthcare professionals when working with older people can be a subtle expression of underlying attitudes, such as the use of child-like or demeaning language. Abuse of the elderly rarely has one cause. Ignorance about the ageing process, the needs of older people and a lack of skill on behalf of caregivers are among the factors that contribute to an abusive situation (O’Keefe and others, 2007).

Towards an understanding of how we age

Throughout history, people have been trying to understand the process of ageing—what causes it, what its purpose is. There is no single accepted theory of ageing; instead, a number of theories have been developed to explain the ageing process (Box 22-2). Biological theories seek to explain the anatomical and physiological changes that occur with ageing, and psychological theories attempt to explain the thought processes and behaviours of ageing people. It is important to remember that theories of ageing are hypotheses and are attempts to seek explanation or meaning for what is observed or experienced.

BOX 22-2 THEORIES OF AGEING

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES OF AGEING

STOCHASTIC THEORIES

Free-radical structure theory. Cellular structure is altered through parts breaking off, or from the loose electrons from these free parts attaching to other cells. Environmental pollutants are thought to promote free-radical activity. Foods that are thought to reduce free-radical activity are those rich in vitamins A, C and E.

Somatic mutation theory. Defective cellular structure and function structure as a result of DNA alteration, RNA mutations and protein or enzyme synthesis.

Cross-linked collagen theory. Collagen constitutes 25–30% of body protein and forms gelatine-like cell matrix. With age, collagen cross-links become more insoluble and rigid.

Wear and tear theory. Damage from external as well as internal sources leads to the progressive failure of the body to repair itself.

NON-STOCHASTIC THEORIES

Programmed cells theory. Cells are thought to be programmed to ‘age’ at specific times.

Run-out-of-program theory. This is an extension of the programmed cell theory—each organism is thought to have a specific number of cell divisions and specific life span.

Neuroendocrine theory. Efficiency of signals between body’s control mechanisms—pituitary and hypothalamus—is altered or lost.

Autoimmunne reactions. Immunological system loses capacity for self-regulation and begins perceiving normal or age-altered cells as foreign matter. System reacts by forming antibodies to destroy cell.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES OF AGEING

Disengagement theory. The foundation of this theory is that there is decreased interaction between the old and others within their environment, and that this is an inevitable and universal consequence of ageing. A significant argument is that the social withdrawal experienced by the elderly is due to their deprived situation rather than a consequence of ageing.

Activity theory. This theory emerged in the 1950s and essentially links keeping active with happiness and ‘successful’ ageing. Studies have demonstrated the relationship between physical activity and wellbeing.

Continuity (development) theory. This theory suggests that essential psychological patterns such as personality and basic patterns of behaviour are consistent throughout the life span. Concepts and patterns developed over a lifetime will determine whether individuals remain engaged and active or become disengaged and inactive.

From Bengston VL 2009 Handbook of theories of aging. New York, Springer.

Ageing can be defined in terms of biological age, or chronological age. However, there is no agreement as to the definition of human ageing, nor are there any precise measures of ageing. One of the difficulties with the study of ageing is the lack of biomarkers of ageing. A question that is often posed in the research literature is how or against what can we measure the rate of ageing—chronological age is the least useful method of defining ageing. Chronological age (age in years) and physiological age (functional capacity) do not always coincide. People can look younger or older than their chronological age: some people appear to age quickly, others slowly. The definitions of old age used for policy development, research or the provision of services are essentially socially constructed—they have a tenuous relationship to the biological ‘ageing’ of individuals. It is important to realise that ‘old age’ is generally defined in an arbitrary way.

What has puzzled researchers is why some older adults are active and vital at age 90 years while others are frail at age 60. Why is there so much variation in ageing? Biological theories have sought to answer these questions, and can be divided into two main groups: stochastic theories which propose that ageing is the accumulated effect of cellular and molecular errors or damage over time; and non-stochastic theories which propose that ageing is predetermined by the programmed mechanisms of the body. Psychological theories attempt to explain changes in behaviour, roles and relationships that occur as individuals age (Bengston and others, 2009).

Understanding normal ageing

Nursing care of older adults poses special challenges because of the great variation in their physiological, cognitive and psychosocial health status. Older adults also vary widely in their levels of functional ability.

Older people themselves tend to have a positive view of their health. The majority of Australians aged 65 years or older (68%) rated their health as good, very good or excellent (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009:89), with a positive view of the future and strong intergenerational relationships (Clarke and Warren, 2007).

Physiological changes

Normal physiological changes are expected in older adults (Table 22-2). These physiological changes are not pathological processes, but may make older adults vulnerable to some common clinical conditions. Some older adults experience all of these changes, and others experience only a few. The body changes continuously with age, but the effects depend on health, lifestyle, stressors and environmental conditions. The nurse should know about these normal changes to provide appropriate care for older adults and to help them adapt to the changes.

TABLE 22-2 NORMAL PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES OF AGEING

| SYSTEM |

NORMAL FINDINGS |

| Integument |

|

| Skin colour |

Spotty pigmentation in areas exposed to the sun; pallor even in absence of anaemia |

| Moisture |

Dry, scaly condition |

| Temperature |

Cooler extremities; decreased perspiration |

| Texture |

Decreased elasticity; wrinkles; folding, sagging condition |

| Fat distribution |

Decreased amount on extremities; increased amount on abdomen |

| Hair |

Thinning and greying on scalp; often, decreased amount of axillary and pubic hair and hair on extremities; decreased facial hair in men; possible chin and upper lip hair in women |

| Nails |

Decreased growth rate |

| Head and neck |

|

| Head |

Sharp and angular nasal and facial bones; loss of eyebrow hair in women; bushier eyebrows in men |

| Eyes |

Decreased visual acuity; decreased accommodation; reduced adaptation to darkness; sensitivity to glare |

| Ears |

Decreased pitch discrimination; diminished light reflex; diminished hearing acuity |

| Nose and sinuses |

Increased nasal hair; decreased sense of smell |

| Mouth and pharynx |

Use of bridges or dentures; decreased sense of taste; atrophy of papillae of lateral edges of tongue |

| Neck |

Nodular thyroid gland; slight tracheal deviation resulting from muscle atrophy |

| Thorax and lungs |

Increased anteroposterior diameter; increased chest rigidity; increased respiratory rate with decreased lung expansion; increased airway resistance |

| Heart and vascular system |

Significant increase in systolic pressure with slight increase in diastolic pressure; usually insignificant changes in heart rate at rest; common diastolic murmurs; easily palpated peripheral pulses; weaker pedal pulses and colder lower extremities, especially at night |

| Breasts |

Diminished breast tissue; pendulous, flabby condition |

| Gastrointestinal system |

Decreased salivary secretions, which may make swallowing more difficult; decreased peristalsis; decreased production of digestive enzymes, including hydrochloric acid, pepsin and pancreatic enzymes; constipation; reduced motility |

| Reproductive system |

|

| Female |

Decreased oestrogen; decreased uterine size; decreased secretions; atrophy of epithelial lining of vagina |

| Male |

Decreased levels of testosterone; decreased sperm count; decreased testicular size |

| Urinary system |

Decreased renal filtration and renal efficiency; subsequent loss of protein from kidney; nocturia; decreased bladder capacity; increased incontinence |

| Female |

Urgency and stress incontinence resulting from decrease in perineal muscle tone |

| Male |

Urinary frequency and retention resulting from prostatic enlargement |

| Musculoskeletal system |

Decreased muscle mass and strength; bone demineralisation (more pronounced in women); shortening of trunk as result of intervertebral space narrowing; decreased joint mobility; decreased range of joint motion; enhanced bony prominences |

| Neurological system |

Decreased rate of voluntary or automatic reflexes; decreased ability to respond to multiple stimuli; insomnia; shorter sleeping periods |

Data from Ebersole P and others 2005 Gerontological nursing and healthy aging, ed 2. St Louis, Mosby; Marieb EN 2009 Essentials of human anatomy and physiology. San Francisco, Pearson Education.

Integumentary system

The skin loses resilience and moisture in older adulthood. The epithelial layer thins, and elastic collagen fibres shrink and become rigid. Wrinkles of the face and neck reflect lifelong patterns of muscle activity and facial expressions, the pull of gravity on tissue, and diminished elasticity (Marieb, 2009).

Spots and lesions may also be present on the skin. Smooth, brown, irregularly shaped spots (age spots, or senile lentigo) initially appear on the backs of the hands and on forearms. Small, round, red or brown cherry angiomas may be found on the trunk (Marieb, 2009). Seborrhoeic lesions or keratoses may appear as irregular, round or oval, brown, watery lesions. Years of sun exposure contribute to the ageing of the skin and may lead to premalignant and malignant lesions. Examination of skin lesions must rule out three malignancies related to solar exposure: melanoma, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (McCance and Heuther, 2006).

Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers) are areas of skin breakdown that result from prolonged pressure on the skin by an external object, such as a bed or chair, usually over a bony prominence, for example the elbow or sacrum (Box 22-3). There is international support to rename pressure ulcers ‘pressure injuries’ to reflect that the majority of such ulcers can be prevented (Armstrong and others, 2008). Pressure ulcers are not part of normal ageing; however, older adults who are bed- or chair-bound are at risk of developing a pressure injury. There are clinical practice guidelines to assist nurses prevent and manage pressure injuries (see Research highlight overleaf).

BOX 22-3 RISK FACTORS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A PRESSURE INJURY

Immobility

Malnourishment

Loss of subcutaneous fat over bony prominences

Excessive moisture on skin surfaces or in skin folds

Urinary and/or faecal incontinence

Cardiovascular disease

Poor arteriole pressure

Cognitive impairment

Diminished sensory perception

Head and neck

The facial features of the older adult become more pronounced from loss of subcutaneous fat and skin elasticity (Marieb, 2009). Facial features may appear asymmetrical because of missing teeth or improperly fitting dentures. In addition, common vocal changes include a rise in pitch and a loss of power and range.

The older adult’s visual acuity declines. This may be the result of retinal damage, reduced pupil size, development of opacities in the lens or loss of lens elasticity. Presbyopia, a progressive decline in the ability of the eyes to accommodate for close, detailed work, is common. There is a reduced ability to see in darkness and to adapt to abrupt changes from dark areas to light areas (and the reverse). Older adults also have increased sensitivity to the effects of glare. Changes in colour vision and discolouration of the lens make it difficult to distinguish between blues and greens and among pastel shades (McCance and Heuther, 2006).

Auditory changes are often subtle. The earliest losses of hearing acuity may be ignored until compensatory attempts such as turning up the volume on televisions and radios are commented on by friends and family members. A common age-related change in auditory acuity is called presbycusis. Presbycusis affects the ability to hear high-pitched sounds and sibilant consonants such as s, sh and ch (McCance and Heuther, 2006). Before assuming presbycusis, inspect the external auditory canal for the presence of cerumen. Impacted cerumen is an easily treated cause of diminished hearing acuity.

Taste buds atrophy and lose sensitivity. The older adult is less able to discern salty, sweet, sour and bitter tastes. The sense of smell is also decreased, further reducing taste. Salivary secretion is reduced (McCance and Heuther, 2006).

Thorax and lungs

Because of changes in the musculoskeletal system, the configuration of the thorax sometimes changes (McCance and Heuther, 2006). After age 55 years, respiratory muscle strength begins to decrease. The anteroposterior diameter of the thorax increases. Vertebral changes due to osteoporosis, which involves the loss of minerals such as calcium more quickly than the body can replace them, lead to a loss of bone mass or density which in turn leads to dorsal kyphosis, the curvature of the thoracic spine sometimes called ‘dowager’s hump’ because of its increased incidence in older women. Calcification of the costal cartilage can cause decreased mobility of the ribs. The chest wall gradually becomes stiffer. Lung expansion decreases. If kyphosis or chronic obstructive lung disease is present, breath sounds are distant (Marieb, 2009).

Translating research into practice

Although the prevalence of venous leg ulcers in the community is not known, venous leg ulcers are a very common health problem in both Australia and New Zealand. Part of the problem for understanding exactly how common venous leg ulcers are is the lack of a consistent definition for a venous leg ulcer, including aetiology.

Venous leg ulcers affect the quality of life of the sufferer: they are painful, affect mobility and are difficult to heal. Venous leg ulcers are costly both to the individual—wound-care products are expensive and not covered entirely by the national health schemes of either Australia or New Zealand—and costly to the community. Community-dwelling older adults with a venous ulcer require a high level of domiciliary nursing services, and sufferers often require lengthy hospitalisations. The cost impact includes pathology, radiology investigations and pharmaceuticals as well as adjunct therapies.

Access to appropriate services for diagnosis and management of venous leg ulcers is not equal throughout New Zealand and Australia; rural areas in particular do not have sufficient resources.

The Australian Wound Management Association (AWMA) and the New Zealand Wound Care Society (NZWCS) sought to address the issue by developing a clinical practice guideline for the prevention and management of venous leg ulcers which would guide the practice of all healthcare professionals, with specific reference to the practice of nurses. A priority is to optimise the prevention, assessment and management of venous leg ulcers via the dissemination of best available evidence, and to simplify clinical decision-making processes for healthcare professionals.

The research

The development of a clinical practice guideline is an important step in the translation of research into practice. The development of the guideline required both organisations to work together, review the relevant literature and manage a consensus process with the experts of both countries. A rigorous approach must be taken which evaluates the available evidence. The guideline presents a comprehensive review of the assessment, diagnosis, management and prevention of venous leg ulcers within the Australian and New Zealand healthcare context, based on the best evidence available up to January 2011.

This guideline has been approved by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the New Zealand Guidelines Group.

Reference

Australian Wound Management Association, New Zealand Wound Care Society. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guideline for prevention and management of venous leg ulcers. Online. Available at www.awma.com.au/publications/2011_awma_vlug.pdf, 2011. 27 Feb 2012. Reproduced with permission of AWMA. All rights reserved.

Heart and vascular system

Decreased contractile strength of the myocardium results in a decreased cardiac output (Marieb, 2009). The decrease is significant when the older adult is stressed by anxiety, excitement, illness or strenuous activity. The body tries to compensate for decreased cardiac output by increasing the heart rate during exercise. However, after exercise, it takes longer for the older adult’s rate to return to baseline.

No significant rise in diastolic pressure occurs with ageing, but due to stiffening of the large arteries there is a gradual increase in systolic pressure (McCance and Heuther, 2006). Although common, hypertension is not a normal ageing change, but it predisposes an older adult to heart failure, stroke, renal failure, coronary heart disease and peripheral vascular disease.

Peripheral pulses are often weaker, although still palpable, in the lower extremities than in the upper extremities. Older adults may complain that their lower extremities are cold, particularly at night.

Breasts

Decreased muscle mass, tone and elasticity result in smaller breasts in older women (Marieb, 2009). In addition, the breasts sag. Atrophy of glandular tissue, coupled with more fat deposits, results in a slightly smaller, less dense and less nodular breast. Gynaecomastia, enlarged breasts in men, may be due to medication side effects, hormonal changes or obesity. Both older men and older women are at risk of breast cancer development (McCance and Heuther, 2006).

Gastrointestinal system and abdomen

Ageing leads to an increase in the amount of fatty tissue in the trunk. As a result, the abdomen increases in size. Because muscle tone and elasticity decrease, it also becomes more protuberant (Marieb, 2009). Gastrointestinal function changes include a slowing of peristalsis and alterations in secretions. The older adult may experience these changes as the development of intolerance to certain foods and discomfort due to delayed gastric emptying. Alterations in the lower gastrointestinal tract may lead to constipation, flatulence or diarrhoea.

Reproductive system

Changes in the structure and function of the reproductive system occur as the result of hormonal alterations. Female menopause is related to a reduced responsiveness of the ovaries to pituitary hormones and a resultant decrease in oestrogen and progesterone levels. In men, there is no definite cessation of fertility associated with ageing. Spermatogenesis begins to decline during the fourth decade but continues into the ninth (Marieb, 2009). The changes in reproductive structure and function, however, do not affect libido. Less-frequent sexual activity can result from illness, death of a sexual partner, decreased socialisation or loss of sexual interest.

Urinary system

While urinary incontinence is not a normal part of ageing, there are some changes which put older adults at risk of developing incontinence. The bladder capacity gradually declines so that it can hold less maximal volume and it is more prone to unstable contractions known as detrusor instability (Abrams and others, 2009). If these contractions are strong enough they may result in urinary incontinence. Stress incontinence is very common in women following childbirth.

Hypertrophy of the prostate gland may develop in older men. This hypertrophy enlarges the gland, which may cause pressure on the neck of the bladder. As a result, urinary retention, frequency, incontinence and urinary tract infections can occur. In addition, prostatic hypertrophy can result in difficulty initiating voiding and maintaining a urinary stream (Abrams and others, 2009).

Musculoskeletal system

With ageing, muscle fibres are reduced in size. Muscle strength diminishes in proportion to the decline in muscle mass. Bone mass also declines. Older adults who exercise regularly do not lose as much bone and muscle mass or muscle tone as those who are inactive. Postmenopausal women have a greater rate of bone demineralisation than older men, although osteoporosis is also a problem for older men (McCance and Heuther, 2006). Older men with poor nutrition and decreased mobility are at risk of bone demineralisation. Older adults who maintain calcium intake, coupled with vitamin D either as a supplement or through sun exposure, throughout life have less bone demineralisation than those who do not.

Neurological system

The number of neurons in the nervous system begins to decrease in the middle of the second decade, which can lead to functional changes (Marieb, 2009). The changes can affect the special senses described earlier. In addition, the older adult may experience a decreased sense of balance or uncoordinated motor responses.

Alterations in the quality and quantity of sleep are often reported by older adults. Reports include difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, difficulty falling asleep again after waking during the night, waking too early in the morning and excessive daytime napping. Age-related sleep changes are summarised in Box 22-4.

BOX 22-4 AGE-RELATED SLEEP CHANGES

• Ageing does not increase sleep disorders; however, approximately 50% of older adults complain of difficulty in sleeping.

• Older adults report sleeping on average 7 hours per night—the same or more than that reported by younger adults.

• Awakenings are frequent, increasing after age 50 years.

• Sleep is subjectively and objectively lighter (more stage I, less stage IV, more disruptions).

• A side effect of many medicines prescribed to older adults is changes to sleep.

• Sleep disturbances are associated with indications of poor health.

• Restless leg syndrome is more common in older adults.

• Insomnia—difficulty in falling or staying asleep—is often co-morbid with medical and psychiatric illness.

• Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB)—snoring through to sleep apnoea—is more prevalent in the older population. The main symptom of SDB is snoring.

• Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a useful treatment for SDB in older adults, with research showing that older adults are compliant with CPAP usage.

• Assessment of sleep problems should include a sleep history including unintentional napping, plus medical history, details of medication regimen, and food and alcohol consumption patterns.

Source: Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S 2010 Sleep disorders in the older adult—a mini-review. Gerontology 56(2):181–9.

Cognitive changes

A common misconception about ageing is that cognitive impairment is an inevitable consequence of ageing. Because of this misconception, older adults may fear that they are, or soon will be, cognitively impaired, and younger adults assume that older adults are confused and no longer able to handle their affairs. Disorientation, loss of language skills, loss of the ability to calculate, and poor judgment are not normal ageing changes. Structural and physiological changes within the brain, such as reduction in the number of cells, deposition of lipofuscin and amyloid in cells and change in neurotransmitter levels, are seen in older adults with and without cognitive impairment (McCance and Heuther, 2006).

Psychosocial changes

The psychosocial changes that occur with ageing involve changes in roles and relationships. Roles and relationships within the family change as parents become grandparents, adult children become caregivers for ageing parents, or spouses become widows or widowers. Group membership roles and relationships change as the older adult retires from work, moves from a familiar neighbourhood or stops attending social activities because of declining health.

Assessment of the older adult

Gerontological nursing offers creative approaches for maximising the potential of older adults. With a comprehensive assessment including the older adult’s strengths, resources and limitations, the nurse and the older adult identify needs and problems and select interventions that maintain the older adult’s physical abilities and create an environment for psychosocial and spiritual wellbeing. A thorough assessment requires the nurse to actively engage with the older adult and provide the older adult with enough time to share important information about their health.

Obtaining a comprehensive assessment of an older adult may take more time than the assessment of a younger adult because of the longer life and medical history and the potential complexity of that history. By planning to spend extra time for the assessment, the nurse and the older adult are less likely to feel rushed. During the assessment process, the nurse may find it necessary to allow rest periods or to conduct the assessment in several sessions because of the reduced energy and limited endurance experienced by some frail older adults.

Sensory changes may also affect data gathering. The nurse’s choices of communication techniques will be influenced by visual or hearing impairments in the older adult. If older adults are unable to understand the nurse’s visual or auditory cues, assessment data may be inaccurate or misleading. For example, if older adults have difficulty hearing the nurse’s questions, inappropriate responses may lead the nurse to believe that they are confused. Table 22-3 suggests techniques to use during the assessment of older adults with sensory problems.

TABLE 22-3 TECHNIQUES FOR ASSESSING OLDER ADULTS WITH SENSORY PROBLEMS

| SENSORY ALTERATION |

ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE |

| Visual disturbance |

Position self in full view of client

Provide diffuse, bright light; avoid glare

Make sure client’s glasses are worn and in good working order

Face client when speaking; do not cover mouth

|

| Hearing deficit |

Speak directly to client in clear, low tones at a moderate rate; do not cover mouth

Articulate consonants with special care

Re-state if client does not understand question initially

Speak towards ‘good’ ear

Reduce background noises

Make sure client’s hearing aid is worn and is working properly

|

Memory deficits affect the accuracy and completeness of the data collected. Information contributed by a family member or other caregiver may be needed to supplement the older adult’s recollection of past medical events and information such as allergies and immunisations. Tact must be used when involving another person in the assessment interview with the older adult. An additional person can supplement the answers of the older adult with the consent of the older adult, but the older adult should remain the focus of the interview.

Perception of wellbeing can define quality of life. Understanding the older adult’s perceptions about health status is essential for accurate assessment and development of clinically relevant interventions. Older adults’ ideas of health generally depend on personal perceptions of functional ability and their expectations of older age. Older adults engaged in activities of daily living (ADLs) usually consider themselves healthy, whereas those whose activities are limited by physical, emotional or social impairments may perceive themselves as unwell.

The nurse assesses the nature of the psychosocial changes facing an older adult and the adaptation of the older adult to those changes. Areas covered during the assessment include the family, intimate relationships, past and present occupation, finances, housing, social networks, activities and spirituality. Specific topics related to these areas include retirement, housing and environment, social isolation, sexuality and death.

Health issues experienced by older people

A number of health issues experienced by older people can have a profound effect on their functional ability, quality of life and ability to remain independent, and can precipitate admission into residential aged care.

Impaired cognition

Three common conditions affecting cognition are delirium, dementia and depression. Distinguishing between these three conditions is challenging, but essential (see Table 22-4, which compares the clinical features). It is not always easy to distinguish among these three conditions. Remember that these conditions are not mutually exclusive, and that individuals may have more than one condition at any one time. Appropriate nursing interventions are specific to the cause of the cognitive impairment.

Delirium

Delirium is a transient disorder characterised by impaired cognitive function and reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention. The disturbance develops over a short period of time. Some common causes include:

• medication—side effects, drug–drug interactions

• alcohol use

• infection, e.g. pneumonia, urinary tract infections

• malnourishment

• dehydration

• urinary retention

• cardiopulmonary disorders leading to anoxia or transient ischaemia

• disorder of metabolism

• central nervous system changes.

Delirium may occur in any setting; the onset of delirium is typically sudden, and there are rapid fluctuations in symptoms and severity. The presence of delirium requires prompt assessment and intervention. The cognitive impairment secondary to delirium is usually reversed once the cause is identified and treatment started. Being potentially reversible is one of the characteristics differentiating delirium from dementia. If delirium in the older adult is not recognised and treated promptly, the sufferer can become very unwell. Delirium is often not recognised, and consequently treatment can be delayed.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Reflect on the last time you worked with an older adult who had impaired cognition. Were the common causes of delirium excluded as the cause of the confusion? An older adult may have dementia, and delirium as an acute problem perhaps related to urinary retention.

Dementia

Dementia describes a collection of symptoms caused by disorders affecting the brain; it is not one specific disease. Dementia affects thinking, behaviour and the ability to perform everyday tasks. Brain function is affected enough to interfere with the person’s normal social or working life. Cognitive function deterioration leads to a decline in the ability to perform basic and instrumental ADLs. There is memory loss, impaired visual spatial skills, behaviour and personality changes—known as BPSD, behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia—and a decline in thinking ability. The progression of dementia in each individual is unique to that person. Clinical signs of depression may be present. The earliest symptoms of dementia may be very subtle and may be dismissed by the older adult’s family as insignificant. The older adult may attempt to conceal the effects of memory loss, to compensate for them or to deny them.

Unlike delirium, dementia is characterised by a gradual, progressive, irreversible cerebral dysfunction. Because of the close resemblance between delirium and dementia, the presence of delirium must be ruled out whenever dementia is suspected.

The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, named after Dr Alois Alzheimer who published the first description. Alzheimer’s disease, also called dementia of the Alzheimer type, is characterised by brain atrophy and the development of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral hemispheres. The cause of the disease is not known, and although several theories are being studied, none are definitive.

Vascular dementia, formerly referred to as multi-infarct dementia, is also very common. Vascular dementia results from interruptions in blood flow to the brain, as in cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease and haemorrhage (McCance and Heuther, 2006). The onset of vascular dementia is usually sudden, although the diagnosis may not be made until the cumulative effect of a series of small vascular events becomes clinically apparent. Although older adults with this form of dementia may display symptoms similar to dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, vascular dementia is distinguished by periods of remission, preservation of personality, insight and unstable emotions.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) accounts for almost 10% of dementia diagnoses. It is a form of dementia associated with the growth in the brain of intracellular bodies (Lewy bodies) that are not completely understood. It is characterised by fluctuating cognition, visual and auditory hallucinations and motor features in common with those of Parkinson’s disease, frequent falling, syncope, sensitivity to neuroleptic drugs, delusions and memory impairment.

Other forms of dementia include the dementias that occur in some individuals with Parkinson’s disease, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and Huntington’s chorea (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). Dementia may also follow head injury, as with dementia pugilistica, in which the injuries are sustained in the sport of boxing.

Dementia is increasingly recognised as a terminal illness. Nursing management of older adults with any form of dementia is complex. Interventions must reflect the needs of the older adult and the needs of the family. Pre-existing acute and chronic physical conditions, sensory impairments, depression and environmental stressors all affect a person living with dementia. Environmental stressors include unfamiliar environments, such as hospitals, and conditions within any environment, such as glare, excessive noise, hurried activities and unfamiliar people. The accident and emergency department of a public hospital, for example, can be a frightening and confusing place for someone with dementia and/or delirium.

Environmental stressors are poorly understood by the older adult with dementia. These misunderstandings lead to increased confusion and agitation. There is increasing emphasis on good environmental design to facilitate people with impaired cognition to live with the minimum of anxiety.

Depression

Delirium and depression, both reversible disorders, are often mistaken for irreversible dementia in the older adult because cerebral dysfunction and cognitive impairment occur with these conditions, as well as with dementia. Consequently, older adults with such disorders may not be appropriately assessed and treated. When dementia and depression occur together, the distress of the older adult and the family is increased.

There is chronic under-reporting of depression in all populations, but older people are most vulnerable. It is thought that one cause is the failure of healthcare professionals to recognise the symptoms, which can present or be described differently in older people.

Depression reduces happiness and wellbeing, contributes to physical and social limitations, complicates the treatment of concomitant medical conditions and increases the risk of suicide. Depression in older people is not always recognised, or treated. One reason for this is the false belief that depression in older people is normal. Contemporary gerontological practice is to treat depression in older people (Haralambous and others, 2009). Risk factors for depression in older adults include:

• being female

• recent bereavement

• living in a residential aged-care home

• multiple physical co-morbidities

• dementia

• medication regimen which includes antihypertensive, analgesics or hypoglycaemic agents

• social isolation

• prior history of depression.

Cognitive impairment related to alcohol abuse

Apart from a lifelong pattern of heavy drinking, alcohol abuse often arises in older age as a coping mechanism to deal with loss, anxiety, depression, boredom or to relieve pain. In addition to its physiological effects, alcohol abuse can affect cognitive functioning. As a result of normal physiological changes, older adults are susceptible to the effects of alcohol. A greater proportion of alcohol is delivered to the brain because of changes in the distribution of body fluids and the proportion of body fat to muscle.

Abuse of alcohol may be under-identified in older adults. The clues to alcohol abuse are subtle, and the assessment may be complicated by co-existing dementia or depression. Suspicion of alcohol abuse increases when there is a history of repeated falls and accidents, a change in behaviour or personality, social isolation, recurring episodes of memory loss and confusion, a history of skipping meals or non-compliance with a medication regimen and difficulty managing household tasks and finances. When abuse of alcohol is suspected, treatment includes age-specific approaches that acknowledge the stresses experienced by the older adult and encourage involvement in activities that match the older adult’s interests and boost feelings of self-worth. The identification and treatment of co-existing depression is also important.

Falls

Falls in people aged 65 years and over are of particular concern because of their frequency, associated morbidity and mortality and cost to the healthcare system and community. Falls are the leading cause of hospitalisation among people 65 years and over.

It is recognised that the cause of falls is multifactorial—a number of factors may be present which contribute to the risk of a fall. While an older adult’s physical aspects can contribute to a falls risk—stooped posture, bone and joint problems—so can the effects of medicines and environmental hazards such as rugs, electrical cords, slippery floors, poor lighting and unsafe shoes (see Box 22-5). Many people experience a fall getting up to use the toilet at night. Research evidence suggests that exercise, such as strength and balance training, is effective in reducing the risk of falls in older people. High-dose vitamin D with calcium has been found to be effective in reducing fractures of older adults living in residential aged care and in the community. In addition, hip protectors have been shown to dramatically reduce hip fractures in people in residential aged care. Evidence–based guidelines for falls prevention in acute care, the community and in residential aged care can be found on the website of the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care (see Online resources).

BOX 22-5 RISK FACTORS FOR FALLS

RESIDENTIAL AGED-CARE FACILITIES

INTRINSIC FACTORS

• Acute health status

• History of falls

• Wandering behaviour

• Cognitive impairment

• Maximal drop in postprandial systolic blood pressure

• Deterioration in performance of activities of daily living

• Reduced lower extremity strength or balance

• Unsteady gait/use of a mobility aid

• Use of antidepressants medication/polypharmacy

• Independent transfers/wheelchair mobility

EXTRINSIC FACTORS

• Relocation between settings

• Environmental hazards

ACUTE CARESETTINGS

INTRINSIC FACTORS

• Age (sharp rise over 60 years of age)

• Circulatory system disorders most likely, followed by nervous system, respiratory system, musculoskeletal and digestive system disorders

• Previous cerebrovascular accident

• History of falls

• Depression

• Cognitive impairment

• Incontinence of bowel or bladder

• Requiring assistance with walking/impaired balance

• Sensory deficits such as impaired vision and dizziness/vertigo

• Use of psychotropic medicines (with greatest risk for those taking more than two medicines)

EXTRINSIC FACTORS

• Hospitalisation for 19 days or more

• Environmental factors

From National Ageing Research Institute 2004 An analysis of research on preventing falls and falls injury in older people: community, residential aged care and acute settings. Online. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/5F45FC4A37A71E0BCA256F19000403C7/$File/falls_community.pdf 11 Jun 2012; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) 2009 Preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: best practice guidelines for community care. Online. Available at www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au/assets/pdf/Community_Care_Guidebook.pdf 7 Jun 2012.

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is a debilitating disorder, and can affect the sufferer physically, psychologically, socially and economically. Although urinary incontinence can affect all age groups, women, the elderly and the disabled are particularly vulnerable; and until fairly recently, little has been offered to those affected. The modern approach to this problem is one of the promotion of continence rather than the management of incontinence, or ‘mopping up’.

It is recognised that seeking treatment for incontinence is difficult for some people; many sufferers never seek treatment. Although it is not known how many sufferers could be cured, it is thought that a large percentage of those experiencing urinary incontinence could become dry. It would be easy to think that everyone living in a residential aged-care facility is incontinent. However, with good assessment and help with maintaining good bladder habits, many residents of aged-care facilities can be helped to become continent or have their incontinence minimised.

Although urinary incontinence is common in older people, ageing does not cause it—that is one of the myths about ageing. Damage and disease can cause incontinence, such as damage to the bladder, sphincters and pelvic floor, or diseases such as diabetes (McCance and Heuther, 2006), or trauma such as a cerebrovascular accident (stroke). In addition, one of the common problems that can aggravate urinary incontinence is constipation.

Urinary incontinence has been defined by the International Continence Society expert review as involuntary loss of urine that can be objectively demonstrated (Abrams and others, 2009). The main types of incontinence in older people are described in Box 22-6.

BOX 22-6 MAJOR TYPES OF INCONTINENCE

Functional incontinence—a condition that many older people living in an institution are described as having. It means that, because of functional decline, e.g. from immobility, impaired dexterity or impaired cognition, the person is unable to manage to use a toilet. It is also thought that there is no such condition as functional incontinence, merely a lack of appropriate help and support.

Nocturnal enuresis—the involuntary loss of urine occurring during sleep.

Post-micturition dribble—leakage of urine following voiding, common in older men.

Stress incontinence—the involuntary leakage of urine on effort or exertion, or on laughing, coughing or sneezing.

Urge incontinence—the involuntary leakage of urine accompanied by or immediately preceded by urgency.

Constipation and faecal incontinence

Faecal incontinence affects a relatively small number of people, although the numbers affected are not known. Predisposing factors include damage to pelvic floor muscles through childbirth, side effects of some medicines, and diseases such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. The most common cause among older and disabled people is constipation and impaction of faeces. Factors that contribute to constipation in older people include poor diet, particularly a diet low in fibre, poor fluid intake, limited exercise, and side effects of medicines. Like many clinical issues affecting older people, it is better to prevent the condition occurring than treat an established condition. Aspects of assessment are outlined in Box 22-7.

BOX 22-7 ASSESSMENT OF BOWEL AND BLADDER PROBLEMS IN THE OLDER ADULT

COMPLETE HISTORY

Resident’s perception of the problem

Date of onset

Nursing history

Medical history

Drug therapy

Previous surgery

Finances

Incontinence aids

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Mental awareness

Physical status

Mobility

Dexterity

Activity tolerance

Environment

Physical

Psychosocial

BLADDER/CONTINENCE CHART

Frequency

Volume

Urgency

Circumstances

DIAGNOSTIC INVESTIGATIONS

Urinalysis

Urodynamics

PLUS

Bowel chart

Fluid intake

Fibre intake

Medication review

From Hunt S 2001 Making sense of assessment data—continence charts, ACCNS J Comm Nurses 7(1):17; O’Connell B and others 2011 A suite of evidenced-based continence assessment tools for residential aged care. Australas J Ageing 30(10):27–32.

Adverse drug events

It has been well documented that the levels of total medicine use (prescribed and non-prescribed) are higher in older than in younger people (Hunt, 2007). Although ageing itself is not a disease process, as people age they tend to develop pathologies for which medicines are used to reduce the effects. The elderly, however, have a reduced ability to cope with medication, due to altered drug kinetics and responses, altered sensitivity to drugs and impaired compensatory mechanisms. This creates clinical dilemmas for the prescriber, for the carer and for the older adult (the consumer of healthcare). Although medicine use can do much to contribute to the quality of life of an older person, a large number of older people experience negative health outcomes directly related to medicine usage. For example, immobility and instability, falls, urinary incontinence and intellectual impairment including delirium and confusion have all been identified in the literature. Each of these clinical issues has implications for the quality of life of the sufferer and the cost of care provision, whether the older person involved is community-dwelling or living in residential care.

An adverse drug event might result from a medication prescribing error, a dispensing error, medication administration error, interaction between medicines or between food and medicines or as a result of polypharmacy. Box 22-8 lists the risk factors for an adverse drug event.

BOX 22-8 RISK FACTORS KNOWN TO PREDISPOSE OLDER PEOPLE TO MEDICATION-RELATED PROBLEMS

• Currently taking 5 or more regular medications

• Taking more than 12 doses of medication per day

• Significant changes in medication treatment regimen during the last 3 months

• Medication with a narrow therapeutic index and/or requiring therapeutic monitoring (e.g. warfarin, digoxin)

• Symptoms suggestive of an adverse drug reaction

• Poor response to treatment with medicines

• Suspected non-compliance or inability to manage medication-related therapeutic devices

• Literacy or language difficulties

• Dexterity problems

• Impaired sight

• Confusion/dementia or other cognitive difficulties

• Attending a number of different doctors, both general practitioners and specialists

• Recent discharge from an acute care facility (in the last 4 weeks)

Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) 2004 Domiciliary Medication Management Review. Canberra, DoHA. Online. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/medication_management_reviews.htm 27 Feb 2012; Therapeutic Goods Administration 2011 Adverse drug reactions: Australian Statistics on medicines 2010. Canberra, Department of Health and Ageing. Online. Available at www.tga.gov.au/pdf/medicines-statistics-2010.pdf 27 Feb 2012. Used by permission of the Australian Government.

Many healthcare organisations have a specific number which is considered to indicate polypharmacy, for example five or nine medicines. There is little research to support an arbitrary number; recognising that medicines help older people to have a healthy lifestyle, increasingly it is thought that it is ‘inappropriate polypharmacy’ that is the issue. After all an older person can have an adverse drug event from one medicine, and several medicines are needed to promote the health of an older person with hypertension and/or diabetes and/or arthritis—all common issues experienced by older people. It is important that all healthcare professionals have a watchful stance related to medicines, older people and the potential for adverse health outcomes. The key is in monitoring for expected effects as well as side effects, and to minimise the number of medicines an older person is either prescribed or administered.

Recent advances to assist the older adult manage their medicines are medication reviews undertaken by an accredited pharmacist, consumer medicines information provided by the supplying pharmacist on dispensing a medicine and the packaging of medicines in dose-administration aids. There is a distinct role for nurses to promote good-quality use of medicines in all clinical situations. Ensuring that older clients know and understand their medicines is the responsibility of all healthcare professionals.

Reducing adverse drug events or drug errors and maximising the effect of a medicine regimen is the goal. This is a high priority for institutionalised elderly people who are at particular risk of experiencing ill-health related to their medication regimen. A medication review enables a current relevant drug profile to be created for each person. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of that drug profile is essential. Nurses tend to be responsible for the administration of medication, or have an overseeing medication management role with this vulnerable group. Therefore, nurses have an important role in monitoring desired effects and the possible side effects of medicines, for example ensuring that adequate and appropriate pain, bowel or sleep assessment is undertaken to ensure that prescribed, prn (as needed) or nurse-initiated medicines or over-the-counter medicines are effective. Nurses should avoid pressuring medical practitioners to prescribe medicines, particularly for management of behaviours causing concern; many non-pharmacological options are very effective. It is important that nurses take opportunities to increase their understanding of clinical conditions and of the various drugs available and their effects on older people.

Successful ageing

With each stage of life come challenges, needs and adjustments, known as developmental tasks (Box 22-9). These tasks are considered part of an adult’s continual growth. Older adults face the necessity of adjustment to the physical changes that accompany ageing. The extent and timing of these changes vary from individual to individual, but as body systems age, changes in appearance and functioning occur. These changes are inevitable but are not associated with a disease. The presence of disease may alter the timing of the changes or their impact on daily life.

BOX 22-9 DEVELOPMENTAL TASKS OF THE OLDER ADULT

• Adjusting to decreasing health and physical strength

• Adjusting to retirement and reduced or fixed income

• Adjusting to death of a spouse

• Accepting self as ageing person

• Maintaining satisfactory living arrangements

• Redefining relationships with adult children

• Finding ways to maintain quality of life

Some older adults find it difficult to accept ageing. This is seen in benign behaviours, for example understating age. But some older adults deny their own ageing in ways that are potentially problematic, such as denying functional decline and/or refusing to ask for assistance with tasks that place their safety at great risk. Acceptance of personal ageing does not mean retirement into inactivity, but it does require a realistic review of strengths and limitations.

Older adults retired from employment outside the home are challenged to cope with the loss of that work role. Older adults who worked at home and the spouses of those who worked outside the home also face role changes as they age. Because retirement is usually anticipated, people can make financial plans and consider replacement activities. Many older adults welcome retirement as a time to pursue new interests and hobbies, to participate in volunteer activities, to continue their education, to start a new business career or to travel. Retirement plans for some older adults include changes of residence, such as moving to a different city or state or moving to a different type of housing within the same area.

Reasons other than retirement may also lead to changes of residence. For example, physical impairments may require relocation to a smaller, single-level home. Severe health problems may require the older adult to live with relatives or friends. A change in living arrangements for the older adult may require an extended period of adjustment during which assistance and support from healthcare professionals, friends and family members are needed.

A large number of older people have to adjust to the death of a spouse, friends or adult children and grandchildren. These deaths represent both losses and reminders of personal mortality. Coming to terms with these deaths can be difficult, and there is a role for nursing in helping with the grieving process.

The redefining of relationships with children that occurred as those children grew up and left home continues as older adults experience the challenges of ageing. A variety of issues may arise; including, but not limited to, role reversal, control of decision making, dependence, conflict, guilt and loss. How these issues surface in situations and how they are resolved depends in part on the past relationship between the older adult and the adult children. All the involved parties bring past experiences and powerful emotions to the situation. When adult children help the older adults of their family, they must find ways to balance the demands of their own children and their careers. As adult children and ageing parents go through these changed roles, nurses may act as counsellors to both the parents and the children. Nurses can help adult children by listening to them and helping them distinguish between changes and behaviours related to illness and those related to normal ageing, and taking account of their parents’ lifelong preferences and patterns of behaviour.