3 Understanding your context: preparing for change

Introduction

We live in rapidly changing times, particularly for those involved in providing and receiving health care. The health sector primarily aims to meet the needs of service users. There are various levels of ‘user’ within the health service environment. For example, within contemporary maternity services there is the woman, who has specific expectations of the obstetrician and/or midwife; the obstetrician, who has specific expectations of the women and the midwives; the midwife, who has specific expectations of the obstetrician; and the maternity manager, who in turn has expectations of the hospital management to provide certain levels of resources in a timely way to support the service they manage. When planning change it is useful to identify these ’users’ and find out:

In making change to meet the needs of one set of these service ‘users’, it is likely that the change will also impact on others within this service as the system is interdependent. Sometimes this is detrimental and brings unanticipated consequences. When the service extends into the community (as is the case in maternity care), the relationships become even more complex. Many groups of service users are influenced by the setting up of a midwifery continuity of care program or project and it is important to be aware of these considerations and the connections between them.

This chapter is designed to explore the use of a process called ‘contextual scanning’ as a tool for mapping the territory to identify these service interconnections and co-dependencies; maximise ownership of the change process; and increase the likelihood that the change will have a positive impact on the majority. I will use examples from my practice as a maternity service development midwife in New Zealand to illustrate the usefulness of this tool as a framework for mapping the territory, clarifying issues and identifying potential strategising processes, and collective decision making in maternity service development.

Most of us who have worked in the health system long enough will have experienced the introduction of a new service or service enhancement that requires considerable change to the way people work. It is clear that where there has been little consideration of whether the context of the change, namely, the environment, is conducive to the change, success is likely to be more challenging. Introducing a model of care based on midwifery continuity of care and a named midwife (particularly if making the transition from traditional ward-based care) will have a profound impact on layers of service users. Those who can predict the risk of service chaos best are the people at the ‘coal-face’, in the ward or delivery suite. They are also most likely to be able to identify actions to mitigate the risk since they are also the ones most likely to be affected by the change. Contextual scanning acknowledges their wisdom and uses it to inform the change process.

This chapter tells the story of how contextual scanning was used during a process of consultation that I undertook in New Zealand. It is my story and so I have written much of the experience in the first person. I hope my story gives others the confidence to embark upon a similar process in their own setting using the principles and approach that I took.

The New Zealand midwifery continuity of care context

From 1990 onwards, individual midwives in New Zealand were able to directly access public health funding for the provision of midwifery care to women. This achievement saw a steady rise in the number of midwives moving out of hospital employment and into community-based continuity of care practices in a self-employed capacity. In recognition of this, and to have some control over the development of these services, the government (Health Funding Authority 1996) established a framework for service provision and payment based on a modular system in 1996. This required the identification of one maternity practitioner, either a midwife or a doctor, as the Lead Maternity Carer (LMC). Once registering with the woman as her LMC, the practitioner would be required to take personal responsibility for provision of maternity care (even when the woman is in hospital) 24 hours a day until 6 weeks following the birth.

This resulted in profound changes to maternity services, particularly in the way that midwives constructed their practices and developed relationships with obstetricians and with maternity hospitals. The changes to other services required to accommodate the ‘continuity of care’ model seemed endless. In gaining this professional autonomy, that is, no longer needing to receive authority from another profession but being accountable for their own actions and decision making, midwives needed access to:

It is difficult to quantify the changes that resulted from the simultaneous national introduction of continuity of maternity care because of the inextricable links within the health sector as a whole. As a midwife manager at the time, this experience forced me to acknowledge the influence of the community outside of the hospital on the construct of maternity services for the future.

Background

After a 20-year career in clinical practice, initially as a nurse then as a midwife, I moved into the area of maternity service development and planning. Over the past 10 years I have been involved in a variety of roles, such as health service auditing, service redesign and strategic planning. I am currently managing the implementation of a district wide Maternity Services Strategic Plan for a District Health Board and am also Executive Director of the Midwifery and Maternity Provider Organisation (MMPO), which provides practice management services for about 700 Lead Maternity Carer midwives throughout the country. It is through the experience of working with and within a variety of different organisations in a number of different localities that the complexities associated with ‘change’ became an interest of mine.

Research into the evolution of maternity services in different localities in New Zealand following the introduction of the LMC model of maternity care (Hendry 2003) led me to believe that the ‘context’ of a service influences the unique characteristics of each maternity service. These contexts include the geographic location, the demographics of the catchment population, the local health service staff mix, proximity to hospitals and specialists, and the traditional roles of medical practitioners in maternity care. Furthermore, the description of these services is influenced by the positioning and knowledge of the person describing the service. Their perception will be based on their relationships with or within the service, their previous experiences and their current role. For example, pregnant women are likely to describe their maternity service differently from a midwife, and midwives will describe the service in another way to the doctor. Midwives in a labour ward are likely to feel they already provide continuity of care to women, if they have a named midwife assigned to each labouring woman on admission. How would you justify the establishment of a ‘midwifery continuity of care’ model to these midwives?

As it became increasingly clear to me that the ‘context’ of service provision had a profound impact on the understanding by midwives and doctors of the maternity care that women received, it occurred to me that service changes should be approached with caution and with a good level of local knowledge and ‘buy in’. Change to a maternity or midwifery service deemed successful in one locality may not be as effective or even appropriate within another. I was keen to explore this more, but needed to find a tool to enable this process.

Environmental scanning

The process of developing appropriate services led me to investigate the concept of environmental scanning, which was created initially by the disciplines of architecture and town planning (Beal 2000). Historically, service planning activities have tended to rely on traditional discipline-specific knowledge rather than new knowledge. Environmental scanning was developed to obtain a snapshot or construct a map of the current situation. This method recognises that:

The use of scanning as a tool to map the territory values a number of individual perspectives of the situation in order to collectively identify current and potential trends, as well as threats and opportunities, which contribute constructively to strategic planning and evaluation (Beal 2000, Boehm & Litwin 1999). Scanning also provides a useful benchmarking method by comparing earlier scans with more recent ones in order to identify and plot change and/or the impact of change (Hatch & Pearson 1998).

The most attractive aspect of this tool is that it enables the capture and analysis of a broad range of data over a short period of time. The inwardly-focused methods of traditional long-range planning models, which relied heavily on historical data analysed by ‘experts’ away from the context of the service, did not encourage decision makers to anticipate environmental changes and assess their impact on the organisation as a whole (Morrison 2000). Scanning is particularly useful when the organisation under investigation is quite complex and interfaces with a number of others. The short time frame for data collection and analysis enables results to be produced and decisions for action made before the contextual or environmental determinants change too much. A long time lag between a scanning ‘picture’ of the services and agreed action could render those actions ineffective or dangerous because of a shift or reconfiguration of the context in the meantime (Choo 2001).

I applied the principles of environmental scanning to a method I describe as ‘contextual scanning’ (Hendry 2003). This method has the capacity to map out both the internal and the external contexts of a health service by positioning it within the community it services. This involves a staged process of systematically analysing information on both the community and the health service through the active engagement of a number of informants from within both the service and the community. This process enables the information to be triangulated in order to construct a multi-dimensional ‘picture’ of the service from the perspective of as many participants as possible, highlighting key issues that impact on service potential, thus providing a collective focus for change.

It has always been a concern to me that well-intentioned and seemingly logical service changes, such as the introduction of new midwifery continuity of care models that have not previously been successfully introduced, profoundly increase resistance to change in that service. In some circumstances I have known service relocation as the only way to introduce change in services that have been subjected to numerous attempts to change the model of care.

Contextual scanning process

Initial development of this method was explored while I was lecturing in a postgraduate midwifery program. I developed a half-day workshop for students using a standardised contextual scanning tool I had constructed (described later) with the object of identifying the similarities and differences in maternity services within the various regions the students came from. I was keen to see how these midwives made sense of any patterns that emerged.

While I first honed the contextual scan as a reflective tool for postgraduate midwife students to examine the organisation of their hospital or practice within the context of the community, I subsequently developed this during my doctoral research (Hendry 2003). I used this process to explore the way midwives had developed rural maternity services and the aspects of this service that they felt made these services vulnerable.

In my role with the Maternity and Midwifery Provider Organisation, I have developed a version of this process for use by individual midwifery practices. This enables them to reflect on their practice development and identify areas that need to be addressed. The process enables midwives to view their services more objectively and holistically through appreciation of others’ perspectives and publicly available information. I have also included consumers, community representatives and health managers in this process to analyse district-wide maternity services as an initial step in the development of a strategic maternity services plan for a whole geographic region. This process forms a critical first step in service analysis prior to implementing change.

Phases of the contextual scan

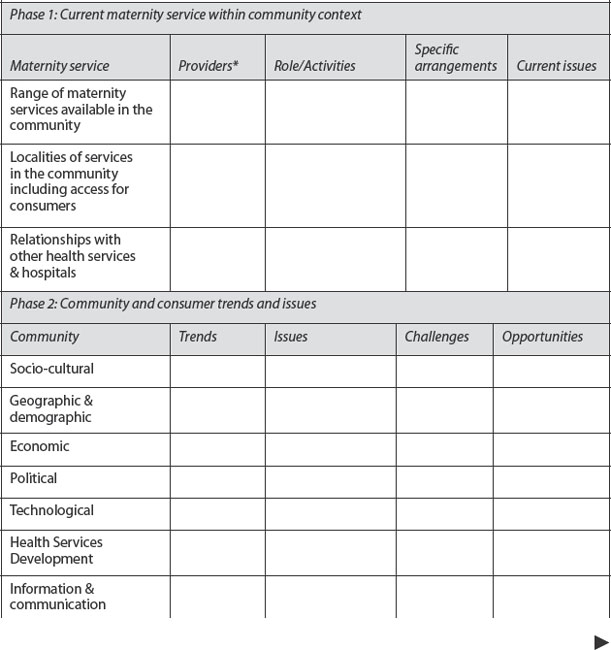

Contextual scanning was developed as a stepped process, which allows participants to systematically map out their service and the context in which it is situated. Recognising that individuals are likely to view the same situation differently, based on their history, knowledge and role in the service or practice, there are no right answers to any of the questions in the scan. In fact part of the process involves a negotiated consensus-driven view of the situation and the service. In a way it could also be viewed as a therapeutic experience. An overview of the four key phases is summarised in Box 1.

Box 1 Key phases of contextual scanning multi-dimensional

The natural progression from here is a desire for action (change) by participants and from then on a shared ownership of the change process.

The process can be completed by a questionnaire sent to a variety of informants or, more interestingly and productively, by using a group process.

Contextual scanning using a group process

The process outlined here can be undertaken with a group of 10–20 participants over a full day. Participants can be divided into smaller subsets for work on each phase. At the end of each phase there is a focussed review of findings within the large group and construction of a shared or consensus response, picture or map.

Each phase of the process is timed, with a set of key questions placed on an overhead or distributed to the groups as a prompt. Each group is given a set of blank overhead transparencies or large pieces of paper on which to place their responses and descriptions. When working on site with a group, I generally allow about one hour for each phase, which includes at least 15–20 minutes feedback to the larger group. To shorten the time, questions can be distributed prior to the session with the group sessions focussing on a collation of agreed responses. A consensus process is fostered by the facilitator during the workshop.

Phase 1: The current maternity service within its community context

A brief overview of the maternity services provided in the locality is requested. This is a natural place to start when inquiring about maternity services within a community. It is also a safe place to start for participants who may not have worked together as a group before. Informants are asked to identify themselves and their relationship to the service. A systematic description of the maternity–midwifery service and its components are necessary to position the participants. This includes:

Participants can also be given the option of drawing a map of these services to demonstrate the links. Box 2 provides an example of how this works in practice.

Box 2 An example of using a group process in conceptual mapping—Phase 1

My experience in the use of this method with a large group of midwives illustrated the different perspective hospital-based midwives had of the ‘maternity service’ compared with community-based midwives. I separated the hospital midwives and community (LMC) midwives into different groups. The hospital-based midwives drew a map of the hospital with their unit highlighted and the connections they had with the rest of the hospital. In comparison, the community-based midwives drew a map of the city with women’s houses, laboratories, doctors’ surgeries, hospitals and their home to describe maternity services in the city.

This difference in perception of ‘maternity services’ between the two groups of midwives demonstrated important challenges that needed to be addressed and articulated the need for change in the service.

In this situation I used the whole group session at the end of Phase 1 to draw up a more holistic maternity service that both groups of midwives agreed to.

The overall aim of this phase is to arrive at a shared description of ‘maternity services’ with local variations identified. Once the service is ‘defined’ the process of contextualising it within the community can begin.

Phase 2: Community trends and issues that actually and/or potentially impact on your service/practice/workplace

This next phase requires participants to focus on their community. The value of a group is appreciated at this point, because the deficits in individual knowledge of their community will often surprise the midwives, particularly those working in the hospital. The differences in response between urban and rural, young and older, hospital- and community-based midwives will become evident during this stage. To assist with this process, an assortment of information on local demographics, census and workforce data is useful. This phase generally highlights how little the participants really know about the demographic characteristics of their own practice environment.

Phase 2 enables the community influences on maternity services to be highlighted. When working with a group of midwives from different localities, the idiosyncrasies of their maternity service can often be linked to some unique features of their community: they can see the service has developed in response to these specific needs. In some situations the ‘disconnect’ between the service and its community can become obvious.

A framework to assist with this process might include:

Box 3 provides an example of how Phase 2 actually works in practice.

Box 3 Focussing on the community—an example of Phase 2

The midwives working in the local maternity hospital could not understand why—even though they had a similar population size to another town in the district—they had less than half the births of the other town. When the community profiles were developed, the differences were glaring. One town was predominantly populated by tourists and tourism focussed businesses. The population was very transient, even though there were more women of childbearing age in that community. The other town was predominantly rurally-based with generations of the same families living close by. On reflection, it seemed that women in the rurally-based town wanted to give birth where they had been born. These women also wanted to give birth close to their families just like the women in the tourist town, who left the tourist town to have their babies closer to their families.

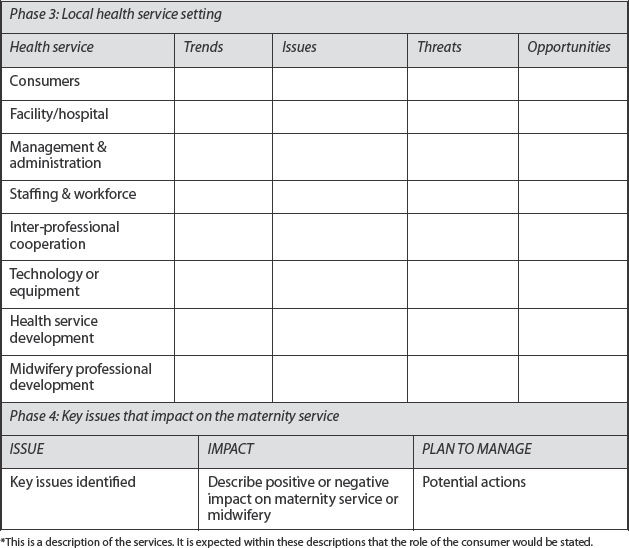

Phase 3: Trends and issues within the local health service setting as a whole that actually and/or potentially impact on your service/practice/workplace

In this phase, participants are asked to assess the trends and issues as well as the threats and opportunities that they believe have the potential to influence their practice and the need for their services within the local maternity setting. The participants are also asked to outline how these aspects influence positively and/or negatively on the quality of the maternity services provided and how they may inhibit midwifery practice. The following headings can be used to facilitate Phase 3.

Phase 3 of the scan requires participants to refocus back onto their local maternity service. This phase is expected to enable them to revisit their service with the hindsight of information on the community context gained in the previous phases of the scan. They may have a clearer understanding of why their service or practice has some features that differ from others. An unexpected by-product of this process for some participants is that they now view their service in a way they have never seen it before. The participants tend to exhibit less parochialism by this stage of the scan as they start to focus on the scan process from shared understandings, and valuing others’ opinions and suggestions.

Box 4 An example of how Phase 3 works in practice

Using the earlier example of the midwives from the two different towns, in this phase of the scan the midwives started to reflect on the service they provided. The midwives in the tourist town did many more pregnancy tests and gave advice and care in early pregnancy, but the women moved out before birth. In the other town, the local midwives were able to provide continuity of care for the whole pregnancy, birth and postnatal period. When each group of midwives looked at their relationship with other health professionals, the midwives in the rural town had a close relationship with the local medical practice, as they referred women there following completion of care. In the tourist town, the midwives felt isolated because they did not really have much communication with the medical practice, which was focussed on the provision of accident and emergency services and transient contact with consumers similar to other medical services in New Zealand tourist towns.

Phase 4: Identifying and prioritising key issues that impact on your service, practice or workplace

This stage of the process requires the participants to use the previous information more strategically. For many midwives this is an unfamiliar activity. It requires an overview of the significant findings of the scan (in the view of the informants) and then agreement (consensus) on areas that are of greatest risk or potential for:

The next step for the midwives and participants is to develop an action plan of some description, either for them as individuals or as a group for their regional service to work on collectively. The desire for change then becomes more real and the direction clearer.

Mapping the territory: preparation for change

On completion of the four phases, a collection of written information is obtained on transparencies or large pieces of paper. As the facilitator, I transcribe these onto a template (Box 5), and arrange a further meeting with the participants to review the ‘map’ and develop strategies for change. The urgency of the process dictates the timing of the next meeting. In some cases, I have reviewed the information overnight to present at a workshop the next day.

The systematic transfer of findings onto these templates provides a useful map of the service and its community. It is clear that the more groups providing the data, the richer the findings and the more stark the issues.

Reflections on using the contextual scanning process

One of the most enlightening aspects of this process is the recognition by participants of the varying interpretations and perceptions of what appears to be the same system or service. As they are assured that there are no right or wrong descriptions, they come to appreciate the value of seeing things differently. This also encourages clearer articulation of thoughts and meanings. In my experience, this philosophical underpinning seems to make the environment of the meeting room safe for disclosure. In some circumstances participants have come to this process believing that either their views are not valued by others, or that the views of others are not valued. In my experience contextual scanning has defused potentially difficult situations because at the outset, multiple realities are valued and identified as essential in contributing richness to the scanning process.

Throughout the development of this exercise with postgraduate midwifery students, the process produced some startling results. For example:

Box 6 provides some examples of shared strategies that have been achieved following these workshops.

Box 6 Shared strategies following Contextual Scanning workshops

These sessions also produced some interesting benchmarking material, including:

Impact of the contextual scanning process for participants

Those who have taken part in this process felt it enabled them to put their frustrations in perspective and start to look at the more fundamental causes of service delivery problems they experienced within their areas of practice. The systematic scanning process seemed to enable them to depersonalise problems and see the value in working together on solutions.

The predominance of a desire for woman-centred care and a commitment to maximise continuity of midwifery care seemed to galvanise the groups and leave them with a sense of camaraderie. This was particularly notable among hospital staff and midwives providing continuity of care from the same locality. Following the contextual scanning process meant the participants seemed to be able to view the services from the others’ perspective. The midwives seemed to feel re-energised and better informed about the problems they faced.

The contextual scanning process seems to work on two levels. Clearly the process gives the informant or participant a different perspective on their practice setting and, for some, on the nature of their practice. Also when the individual perceptions are amalgamated, it provides a multi-dimensional view of the midwifery and maternity services within their context. The process can form a useful starting place for planning and strategy development.

Reflections on the role of the facilitator–planner

The amount of information accumulated through this process can be overwhelming. Initially the participants are tempted to provide too much detail. Scans are not intended to be very detailed, but brief, providing a topographical overview (Boehm & Litwin 1999, Beal 2000). The role of the facilitator is important in ensuring that the group moves through the questions and does not get bogged down in the detail.

The allocation of timeframes to each phase is important. This also assists the collective decision-making process, with the achievement of consensus pressured by time. Natural leaders (potential change agents) often develop within the group to keep colleagues on track. However, the facilitator needs to ensure that these people do not dominate the decision making. It is also advisable not to have these people as the scribes in order to reduce the risk of gaining an incomplete or skewed version of the group responses. The written responses are expected to be in brief statements or bullet point form under each heading of the scan questions.

As this is a group process, the group can become particularly effective at encouraging participation from all members and can make it more difficult for individuals to sabotage the process. The facilitator also encourages these attitudes. Non-participation is an option for a group member, but it has been my experience that those who have come to the process begrudgingly have found it difficult to hold back from expressing their views in the end. All groups and scan experiences are different. Participants who have been involved in numerous attempts to make ‘change’ happen are the most difficult to involve and can feel quite flat to start with. They need to understand the rationale for the scan and be assured that action will follow.

Application of contextual scanning in preparation for change

I have used the principles of contextual scanning in a variety of settings over the past 6 years. The following case is an amalgamation of a number of service reviews I have undertaken. I have constructed this ‘case study’ to illustrate the use of the scanning process.

Development of a district-wide strategic plan: an example

I was asked by the funding division of a regional Hospital Board to ‘review’ their maternity services because of growing public concern over the recent closure of one of their rural maternity hospitals. The rural hospital was situated in a small town about 30 minutes from the city-based, obstetric referral unit. The Board were clear that they wanted services in the whole district reviewed, not just the service that had been closed.

As part of the district wide process, I established an advisory group with representatives from consumers, midwives, doctors, maternity service providers and community representatives. I did not live in this part of the country and knew very little about it. In preparation for the scan process, I gathered as much recent data on the community, health and maternity services as I could locate. Using these data I constructed a power point presentation that systematically worked through the phases of the scan process at the first advisory group meeting. To start each phase of the scan, I presented relevant data to inform the process and then used the group to fill in the gaps and give the background information and history behind specific features of interest. Due to time constraints we did not break into small groups, and I think this worked best in the long term as it did not create or allow any ‘cliques’ to develop.

By the end of the process we managed to map out the entire geographic region and demonstrate trends in population, health workforce, health service access and utilisation across the area. This enabled the group to form a shared understanding of where the service currently was, where information gaps were, and what specific factors seemed to influence the service in particular ways.

Of special interest was the community where the maternity hospital had been closed. The contextual scan revealed an interesting picture, which had not previously been put together. The process had not been helped by conflicting views of the motives behind the closure, with the Hospital Board being accused of placing cost cutting ahead of community needs.

As part of the data gathering I had sought data for the previous five years from a number of local and national sources covering:

The following picture emerged:

A public meeting was held in the town one month following the contextual scan. A profile of the community (a summary of the scan) was presented at the start of the meeting. The media were present and at least 40 vocal community representatives. The first question I asked was ‘who in the room has used the service over the previous 5 years?’ Only one hand rose. A number had been born in the hospital, but they had not used it for their own births.

This process provided an opportunity to explain the maternity service funding system, which enables self-employed doctors and midwives (LMC) to set up their own practice and access public funding for these services paid on a ‘per case’ basis. I used the example of the closure of their local hospital to illustrate how the midwifery workforce (as with any health workforce) is reliant on numbers of patients using their service and birthing in the local hospital to maintain a viable practice. If local women chose to use the city midwives and give birth in town, the hospital midwives become under-utilised and there will be no incentive for self-employed midwives to set up a practice. This information generated a great deal of discussion among women at the meeting, who decided that they needed to refocus their campaign to maintain maternity services in their town.

Not long after this meeting I was contacted by a small group of women who were intent on attracting midwives back into the area. Twelve months later this group had set up a maternity resource centre in a house close to the old closed maternity hospital. They managed to get a small amount of funding from both the community and the Health Board who had commissioned the maternity review. Over the next 18 months three continuity of care midwives moved into the town. Between them, these midwives attended the births of 94 local women in the past 12 months (some at home). The midwives did have to travel to the city to attend the women who wanted a hospital birth, but these women did have local midwives visit them at home following the birth. They also knew that when they are pregnant again, they could visit the local maternity resource centre to access a continuity of care midwife. It is just possible that they may build up enough local interest in the service to re-establish a local birthing unit.

The above example illustrates the usefulness of the contextual scanning process in depersonalising the ‘causes’ of service failure, allowing useful information to guide the process towards achieving the level of service required by women.

Using the scanning process to review a midwifery practice

I have also used the scanning process to work with a midwifery group practice. The following constructed example illustrates adaptation of the tool for work with a small group of community-based midwives.

I was contacted by a practice of eight midwives who had been together for about 5 years, but felt they were drifting apart and losing focus as a group. Some were thinking of leaving the practice because they felt others were not ‘pulling their weight’. These midwives did not feel they had the time to take part in a 4-hour workshop, so I constructed a questionnaire based on the four phases of the scan. I adapted the questions to focus more on the practice and their immediate community (Box 7). The questionnaire was distributed to the individuals who completed them separately and returned them to me two weeks before my planned visit to the practice (a 60-minute flight away).

Box 7 Contextual scan: overview of the questionnaire content

Following receipt of the questionnaires, I constructed a summary table of the findings and coded the midwives names. Distinct patterns emerged of:

I then developed a presentation summarising the collective findings. The most interesting finding was that all the midwives identified a lack of coordination of the group as the most important key issue. It was here that I was able to focus the group on working towards a process of redesigning their practice to minimise the frustrations that had caused the group to approach me.

Following the initial meeting with me, the practice went on to make some fruitful changes and worked on these in subsequent practice meetings.

Application of this scanning process to other countries

The scanning process can be used for a number of purposes ranging from a total review of maternity services to use as a reflective process for midwives working within a practice or hospital-based service. However a number of factors will influence the usefulness of the process.

I have coined the term ‘consultation inertia’ to describe a mood among staff who have had a procession of ‘experts’ meet with them, hold workshops, interview them and produce ‘reports’ that never seem to go anywhere. I advocate that any process that actively involves staff taking part in a service development, adaptation and/or change should have a timeline for action with named people accountable for achieving the milestones.

Conclusion

This contextual scanning process has evolved over time and has proved to be useful as a means of obtaining a more constructive and inclusive view of maternity services. Because of the interrelationships and interlinkages between maternity services and the community in which they are based, the introduction of change is a complex process and may have unforeseen consequences. Contextual scanning is designed to provide a tool for collectively mapping the territory, identifying and prioritising issues that need to be addressed, and using collective wisdom to plan a path for change.

The principles of contextual scanning as a four-phased process can be applied to various levels of a service. As a district-wide process, representatives or stakeholders from both within the service and the community can work collectively through the process as a strategic planning exercise. Midwives from a variety of communities can also work collectively through the process to plan strategies to support the continuation and further development of midwifery in their community. A midwifery group practice can use this tool to assess their practice context and plan actions to strengthen their service. In all cases, application of the scanning process at an agreed time following the change provides a useful benchmark for progress.

One of the essential elements of any contextual scanning process will be the collaboration between all the key players. Chapter 5 explores collaboration in maternity care in detail, in particular the collaboration between midwives and doctors that is needed to establish and sustain midwifery continuity of care. Chapter 4 explores the key components and some useful practical strategies for implementing the model that best suits your community and context.

Beal R. Competing effectively: environmental scanning, competitive strategy and organisational performance in small manufacturing firms. Journal of Small Business Management. 2000;38(1):27-47.

Boehm A, Litwin H. Measuring rational and organisational–political planning activities of community organisation workers. Journal of Community Practice. 1999;6(4):17-35.

Choo C. Environmental scanning as information seeking and organizational learning. Information Research.2001;7(1). Online. Available: http://InformationR.net/ir/7-1/paper112.html, 13 Nov 2007.

Duttweiler M. Environmental scanning principles and processes. Online. Available: http://staff.ccc.cornell.edu/administration/program/documents/scanintr.htm 14 Feb 2008, 2004.

Hatch T, Pearson T. Using environmental scans in educational needs assessment. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 1998;18(3):179-184.

Health Funding Authority. Notice issued pursuant to Section 51 of the Health & Disability Act 1993 concerning the provision of maternity services. New Zealand: Wellington, 1996.

Hendry C. Midwifery in New Zealand 1990–2003: the complexities of service provision. PhD thesis. Sydney, Australia: University of Technology; 2003. Online. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/2100/256, 13 Nov 2007.

Morrison J. Environmental scanning. Online. Available: February 2002 from http://www.horizon.unc.edu/courses/papers/environscan/, 2000. 13 Nov 2007