Chapter Four Cultural safety: cultural considerations

Over the course of your nursing professional education, you will study the developmental tasks and the principles of health promotion across the life span. You will learn to conduct numerous assessments, such as a complete health history, a psychosocial history, a mental health assessment, a nutritional assessment, a pain assessment, a suicide risk assessment and a physical examination of a patient. There are many factors that influence health; for example, gender, age, social circumstances. However, depending on your reactions to the person there may be wide variations in the information you gather in these assessments and in the findings of the physical examination. It is imperative that you, as a healthcare provider, come to understand how culture influences health and healthcare.

There is considerable variation in how culture is defined and approached and terms such as race, ethnicity, cultural competence, cultural diversity and cultural inclusion add to the complexity and confusion. Further there are two major approaches used in nurse education to address issues of culture and health: transcultural nursing and cultural safety. Madeleine Leininger is generally considered the pioneer of the approach called ‘transcultural nursing’. This approach argues that to offer effective nursing care you need to have knowledge of the cultural heritage, language requirements and culturally based health and illness beliefs and practices of the people for whom you are caring. In this chapter our focus is not on the culture of others as such, as we agree with a comment in an Australian national review of multicultural nurse education in 2001 which reported that Leininger’s work was ‘criticised as being too focussed on the culture of the “other”: presenting cultures as static and deterministic’ (Department of Education, Training & Youth Affairs (DETYA), 2001).

This text uses an alternative approach called ‘cultural safety’ developed by Irihapeti Ramsden in 1990 in New Zealand (Aotearoa1), which is centred on the nurse’s self-awareness. So you will ask: Who am I? Where do I come from? What is my ethnicity and what is my social and cultural background? What are my beliefs and values? What prejudices, stereotypes and attitudes do I hold about those I consider different to myself? How might my cultural identity impact on clients? Have I really listened to how this person experiences pain or have I made assumptions about their behaviour? So cultural safety is not about cultural practices as such and it has an additional element in that it ‘… seeks to recognise the position of certain groups in society and how they are treated rather than how they are different’ (DEST, 2001 [authors’ emphasis]). A focus on the current social crisis in healthcare for groups such as immigrants and Indigenous2 people in political terms is a central feature of providing culturally safe care, so you will also need to become knowledgeable about the history of your country and how it functions socially to impact on the health of those in your care. A comment from an Indigenous student following a unit on cultural safety reveals these concerns:

The best aspect of this unit for me was having a subject that I understand and can relate to being Indigenous. We have come a long way from not being citizens in our own country and all the rest of it to have my people fight for rights and it is a huge thing for me as a Murri to see my people and culture be recognised and educating mainstream Australians about it because it obviously needs to be done.

The purpose of this chapter is to:

1. Introduce the population contexts of Australia and New Zealand

2. Consider the relationship between health and culture in Australian and New Zealand demographic contexts

3. Define culture, race, ethnicity and health

4. Consider ideas of cultural competence and cultural safety

5. Describe the position on Indigenous issues and cultural assessment of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council and the NZ Council of Nursing

6. Discuss the steps to cultural safety and strategies to achieve it

7. Describe methods for cultural considerations in assessment.

AUSTRALIA: COLONISATION AND THE CURRENT POPULATION CONTEXT

Given the history of colonisation in the Australian context, the population is comprised of First Nations peoples, descendants of European settlement and migrants. Before discussing more fully how culture and healthcare interact it is important for nurses planning to work in Australia to understand the context of their work in terms of the populations they will be serving. This is true for both international and domestic nurses. In the author’s experience the former often have little understanding of Australian populations and their histories and the latter have variable levels of historical knowledge and a mix of attitudes towards various population groups. Some people carry entrenched and unexamined attitudes towards Indigenous Australians, mainstream3 Australians or migrants. This may in part be due to their lack of experience and exposure to Indigenous Australians, or to their lack of knowledge about Indigenous history, as reflected in this comment from a student: ‘I was surprised to see the number of students that had never had any interaction with Indigenous Australians or travelled outside their birth city. It was good to see them able to discuss their own culture and learn of the suffering still inflicted on Indigenous persons. I later saw it as a relevant topic to those students.’

Most people, however, are well aware that Australia is now a multicultural society, but what is perhaps less well known is that before the British began the colonisation of Australia in 1788 some 500 Indigenous language groups had lived here for up to 80 000 years (Colbung, 1988; Crisp and Taylor, 2005: 123). Further they were not the aimless wandering nomads so often depicted but lived in ‘well-defined socioeconomic, political, land-owning units’ as Crisp and Taylor note. From the perspective of Indigenous people then, the more than 200 years since colonisation is but a moment in their overall history. This point is important because it explains why it is that Indigenous Australians consider themselves to be First Nations or Status People; that is, they have specific and enduring rights in Australia.

Some people find it difficult to understand why it is that historical issues are so fresh in peoples’ minds because they see colonisation as happening over 200 years ago. However colonisation is an ongoing process rather than a single event and it continues to be played out in government approaches to Indigenous people.4 Unlike the New Zealand situation (see below), the colonisation of Australia was enacted under the legal fiction of terra nullius (empty land), which left the way free for the newcomers to take possession of the land and morally justify the impact on Indigenous peoples. Many Indigenous people lost their lives through massacres, starvation, neglect and introduced diseases.

Further, it was said of the Australian Indigenous cultures and the incoming colonisers that it would be hard to find such differing understandings of the world and humans’ place in it. Country for Indigenous people was and is the source of their identity and the basis of their cosmological understandings of the universe; for the newcomers it was merely a resource to be exploited. The current crisis in Indigenous health that we see today is profoundly related to dispossession and removal from kin and country and related traditions including language and ceremonial (religious) life, which often reduced Indigenous people to the status of fringe dwellers in their own land during the nineteenth century. In addition, many were unable to hunt or gather traditional foods and instead were forced to live on poor quality rations such as white flour and sugar, and substances such as tea, tobacco and alcohol were introduced.

The twentieth century brought complex legislative frameworks in all states and territories that attempted to control every aspect of the lives of Indigenous people, first under the banner of ‘protection’ since the authorities assumed that Aboriginal people would ‘die out’. As in New Zealand, the authorities were concerned about increasing numbers of those they conceived of as ‘mixed-race’5 children and they set about developing policy and practice to remove ‘fair-skinned’ children from their Aboriginal parents and kinship groups: those are now generally known in Australia as ‘the stolen generations’. When the state came to terms with the fact of continued Aboriginal existence the policy changed to assimilation in which the goal was to train the stolen generations, and Indigenous people more generally, to live like whites. In these complex processes families were fragmented by institutionalisation on government or mission reserves and reformatory schools and by marginalisation from the workforce, education and health services (see Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1996, 1997; Kidd, 1997; Reynolds, 1982; Rintoul, 1993). Indeed health services were involved in some of these processes. The result is that since health services are largely run by governments, attending them is often resisted as the experiences are bound up in fear and a lack of trust towards health services (see Cox, 2007; Forsyth, 2007). Historical processes, such as deeming petty misdemeanours a crime under the special laws on missions and reserves, also saw the widespread criminalisation of Indigenous populations that we still see today in the overrepresentation of Indigenous people at all levels of the criminal justice system (Cuneen, 2001).

Although in the late 1970s the special laws in the states and territories for Indigenous Australians began to be changed, the ideal of true self-determination is difficult to achieve without a treaty or proper political representation. Space does not permit us to discuss Native Title and Land Rights here and the ongoing struggles for people to be recognised in these processes, given the many different contexts in which they live. Students are referred to Ritter (2009) for further information on these topics. The federal government finally made a national apology to Indigenous Australians in 2008; however, adequate concrete compensation has never been realised.

It is also important to understand that Aboriginality or Indigenous identity is not about skin colour but is about relationships. Because of the lack of trust between mainstream health services and Indigenous Australians the latter began to set up their own primary healthcare services from the 1970s. These are known as Aboriginal Medical Services and their peak body, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), supports the nationally accepted means of determining Aboriginality. The means of determining has three parts and all are needed for Aboriginality to be recognised: descent (the individual can prove that a parent is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent); self-identification (the individual identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander); and community recognition (the individual is accepted as such by the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community) (NACCHO, 2007).

The estimated resident Indigenous population of Australia as at 30 June 2006 was 517 000 people, or 2.5% of the total Australian population. Like many colonised peoples Australian Indigenous people still experience widespread poverty, have lower life expectancy and poor health and they are more likely to be unemployed, experience housing problems and have poorer educational outcomes than the rest of the population. Of the states and territories, NSW had the largest population of Indigenous Australians (152 700 people), followed by Queensland (144 900 people). The Australian Capital Territory had the smallest population of Indigenous Australians (4300 people), while Indigenous Australians comprised 30% of the population of the Northern Territory (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2006a). An issue that many Indigenous and mainstream Australians have in common is religion, as 73% of Indigenous Australians who answered the question about religion in the census were of a Christian denomination (ABS, 2006c).

Another important factor is that more than one in five Australians were born overseas which means that you, your colleagues and your clients will come from a range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. According to the 2006 Census, the proportion of the population born overseas has not changed since 1996 and is 22% of the total population. The overseas-born population increased in number between 1996 and 2006 by 13%, from around 3.9 million to 4.4 million. The two largest overseas-born groups consisted of those born in England (19% of all overseas born) and New Zealand (9%). China overtook Italy as the third largest birthplace group (each country accounting for around 5% of all overseas born). Around 2.1 million of Australia’s overseas-born population is European. Of particular note for nursing is that a number of Australia’s recent arrivals were born in countries recently affected by war and political unrest. Over 73% (or around 14 000) of Australian residents born in Sudan arrived in 2001 or later. Likewise, a high proportion of the populations born in Zimbabwe (48% or 10 000 people), Afghanistan (45% or 7000), and Iraq (34% or 11 000) arrived in 2001 or later. Since 1996, the groups which increased the most in number were those born in New Zealand (by around 98 000), China (96 000) and India (70 000) (ABS, 2006b).

Since communication is central to nursing care it is important that you understand the diversity in this area too. The ABS reports that there are over 60 languages spoken by Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders and an additional 200 languages other than English spoken in the Australian community. The 2006 census found that 11% of all Indigenous Australians spoke an Indigenous language at home, and in the Northern Territory 54% of Indigenous people spoke an Indigenous language at home. Sixteen per cent of the total Australian population did not speak English at home. There were also important variations in English proficiency amongst those who spoke another language, based on their age and their place of birth. The ABS estimates that 84% of all people younger than 25 years who spoke another language at home spoke English well or very well, compared with 60% of those aged 65 years and over. People born in Australia who spoke a language other than English at home could generally speak English well (ABS, 2008).

AOTEAROA: COLONISATION AND THE CURRENT POPULATION CONTEXT

Most people living in New Zealand know something of the history of the land, in as much as Māori settled Aotearoa from the Pacific over 1000 years before European explorers started arriving. Pre-European contact saw Māori as a people deeply connected to the land and natural world around them (Consedine and Consedine, 2001: 80). Their societal life structures were based on kinship and tribal affiliations, laws were based on custom. When the British began their antipodean colonising they initially opted for the larger continent of Australia and it was the sealers and whalers who set up temporary residence in New Zealand. Eventually settlers arrived and by the early 1800s the population of Europeans was believed to be around 2000. Numbers of Māori at that time were estimated to be around 125 000 (Waitangi Tribunal, 2010).

In 1838 the British sought to annex New Zealand due to numerous unscrupulous purchases of Māori land and the lawlessness that had arisen among the people. On 6 February 1840 a treaty was drafted (the Treaty of Waitangi) and signed by the English and approximately 45 Māori Rangatira (chiefs). In addition, a Māori text of the treaty (Te Tiriti O Waitangi) was taken to northern parts of the country and copies were sent to other areas of the land to obtain additional Māori signatures. In signing the treaty, the chiefs are believed to have yielded their sovereignty to the Queen of England in exchange for the Queen’s protection and the granting to Māori the same citizenship rights, privileges and duties enjoyed by the citizens of England. The treaty also guaranteed Māori possession of their land; however, with a stipulation they could sell their land only to the Crown. The treaty was to recognise New Zealand at that time as one nation but two people: the Indigenous Māori people, and the non-Māori, mainly European settlers and their descendants.

Initial reading of the treaty seemed to promise benefits for both sides, but when more and more settlers arrived they wanted to buy land. If Māori did not wish to sell conflict would eventuate. Many lost their lives in the wars that erupted. But it was not only the wars that eroded the Māori population, it was also the diseases introduced by the Europeans to which Māori had little or no natural immunity. Loss of land also saw many living in poor conditions in makeshift camps with poor sanitation. By 1900, the Māori population had dropped to an estimated 45 000 (Consedine and Consedine, 2001: 99) and Māori were seen by the settlers to be a ‘disappearing race’. Their tikanga (general behaviour guidelines for daily life and interaction in Māori culture, commonly based on experience and learning that has been handed down through generations) was also being eroded. This wearing down of the fabric of Māori life has continued until today.

The intent and provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi were largely ignored until the 1970s, when legislation was introduced requiring statutory bodies and government to undertake their responsibilities in a manner consistent with the founding promises of the treaty. In 1975 the Waitangi Tribunal (see www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz/) was established to consider claims by Māori against the Crown regarding breaches of principles of the treaty and to make recommendations to the government to provide recompense. Since 1985 the tribunal has been able to consider acts and omissions by the Crown dating back to 1840. This has provided Māori with an important means to have their grievances against the actions of past governments investigated. Aside from these actions and grievances, attention and awareness is now also on the aforementioned health and social disparities and there is a focus on improving the health and social status of Māori while recognising and respecting all aspects of cultural being.

The legacy from those early years is a society with ‘major ethnic and cultural disparities in health status and most other markers of Indigenous wellbeing’ (Kearns, Moewaka-Barnes and McCreanor, 2009: 124). Aside from the loss of land Māori experienced loss of their language and their cultural way of being. They are over-represented in nearly all negative social and health statistics; for example, unemployment, poverty, housing, income, education, youth suicide rates and general health and wellbeing. Kearns et al (2009: 124) suggest that the processes of colonisation such as that which Māori experienced resulted in the ‘denigration, marginalisation and alienation’ of the very essence of their culture. Consedine and Consedine (2001: 218) suggest that as a result of this colonisation

… the infrastructure of New Zealand Society is structured to deliver white privilege. Only the exotic features of Māori culture were encouraged, where they benefited the country in areas such as tourism and sport.

While the majority of early settlers were British, since that period people have arrived from Europe as well as Asia. In the second half of last century following the world wars a significant migration of people from the Pacific began (Khawaja, Boddington and Didham, 2007). The population of Pacific peoples grew quite rapidly during the late 1960s and early 1970s and caused a great deal of racial tension at times with both Māori and non-Māori groups. An important aspect of reducing this tension and ultimately accepting Pacific groups was the formation of partnerships with various community groups and activities as well as an increase in intermarriage. By the late 1990s a large proportion of Pacific people were born in New Zealand and increasingly their children were also of Māori and other ethnic descent. The other major population group to appear was Asian. Arrival of Asian groups actually predates the Pacific groups although in much smaller numbers. Many arrived in the late nineteenth century during gold rush days. Later in the twentieth century the number of different Asian groups increased dramatically and at the 2006 census they had exceeded the Pacific groups in population numbers. Much more recently, refugees and other settlers from Africa and the Middle East have arrived.

The diverse generations born and arriving in New Zealand since the first colonial settlers have afforded opportunities for miscegenation (a very old term referring to the process by which children are born to parents who were assumed to be of different ‘races’) of New Zealand’s population groups (Khawaja et al, 2007). As suggested earlier, although colonial thinking was that Māori would eventually disappear or be absorbed into the European population, this assumption has been discredited. However, it is this thinking that firmly influenced the collection of official statistics for much of the twentieth century. Khawaja et al (2007: 5) refer to the routine assignment of ‘ethnic grouping on the basis of ancestry (degree of blood), with little or no regard to lifestyle, culture or beliefs’.

The census of 2006 (Ministry of Social Development, 2009) revealed a population of almost 3 million (77%) European, just over half a million Māori (14%), with the remainder being Asian (9.2%), Pacific (6.9%) and other (0.9%) respectively. The apparent anomaly in these figures is caused by people identifying with more than one ethnic group (Ministry of Social Development, 2009). Because people can identify with more than one ethnicity, the total number of ethnic responses may be greater than the number of people. Consequently understanding ethnicity is important, and having a mutual understanding of this might be even more important. This is, however, not so simple and later in this chapter we explore the ideology of ethnicity.

Suffice to say in summary that Indigenous groups have their own structural, institutional and interpersonal philosophies and practices from which they operate. Nonetheless, colonised societies such as Aotearoa and Australia develop to fit the lifestyle, values, priorities and beliefs of the incoming dominant cultures and so the culture of the colonisers becomes the norm in society’s main institutions such as health, education, welfare, corrections, the media and so on. It is this kind of sometimes hidden but always present cultural dominance and unexamined privilege that the practice of cultural safety, discussed below, seeks to overcome. For example, in Australia the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (NHHRC) (2008: 211) noted that ‘Generally, the health system delivers services in a way that is better suited to the needs of the broader population rather than the particular needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’.

DEFINITIONS OF CULTURE, ETHNICITY, RACE AND HEALTH

Before we can begin to consider cultural assessment issues we need to be clear about what we mean by the various terms used in this context. The common terms used include: culture, ethnicity, race and health. While there are numerous definitions of these terms we have taken a constructivist view, referring to the notion that humans create ideas about culture, ethnicity, race and health. That is, such concepts do not just appear from nature but are constructed by humans to serve certain purposes at certain times.

Culture

Some definitions of culture focus on material culture: art, dress, artifacts and so on, while others focus on the capacity of humans to symbolise their world and experience through, for example, language, religion and kinship. Many definitions discuss cultures as ‘bounded wholes’ where members share systematised/patterned values and beliefs. We particularly like the definition in Kluckhohn and Kelly (1945: 97) as it indicates the importance of history for our cultural identity and it is clear that culture is created and acts as a potential guide to action: ‘By culture we mean all those historically created designs for living, explicit and implicit, rational, irrational, and nonrational, which exist at any given time as potential guides for the behavior of men … culture is constantly being created and lost’. Such definitions can be contrasted with other versions which suggest that cultures are unvarying bounded canons of beliefs and practices that all members of a society embrace to an equal degree.

Our view of culture is grounded in the idea that cultures are dynamic and adapt to new circumstances and that they are learned, that is, one is born into a culture not born with culture. Further we assume that culture is strategic as we emphasise or deemphasise aspects of our culture depending on current needs and circumstances. So we are less interested in Culture (for example high art or classical artistic traditions) and more interested in culture as the everyday meanings and motivations in peoples’ lived experience and how they make sense of life experiences such as illness and explain it to themselves.

Further, for our purposes culture includes but is not just about ethnicity and customs such as food, dress and religion, beliefs and values; it addresses differences in socioeconomic status, age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnic origin, migrant/refugee status, religious belief, values, disability and power relations (Eckermann et al, 2006: 2). It is crucial that you are able to distinguish ethnicity from culture. To do this, think about the culture of nursing or policing, for example, which have nothing to do with ethnicity, food and so on but are about ways of doing things and thinking about things. Does this mean all nurses do things and think the same things? NO! Culture is always learned, dynamic, changing and strategic. It is negotiated and expressed and understood differently by individuals who identify with a particular culture. Culture is about everyday ways of doing things and is often unconscious as people cannot always tell you why they do things a certain way but will say ‘That’s just how it is done’. Part of your challenge is to bring your cultural assumptions to mind, an issue discussed further below.

Ethnicity

As indicated above, ethnicity is distinguished from culture and refers to socially constructed group identification or belonging based on familial descent (kinship) and history and traditions in language, food, dress and so on. In multicultural Australia—with Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders being the only true Indigenous populations—mainstream Australians are still reluctant to speak of ethnicity and ethnic differences in relation to their own identities. They may say things like ‘I don’t have an ethnic identity’ or ‘I’m just Australian’. For example, at the beginning of a unit on cultural safety students were asked to tell the group about their cultural and ethnic identity. Consider this comment by a student in her reflection on this unit of study: ‘Learning about cultural safety, was great! Never actually sat down and thought about my own personal culture before. Very rewarding!’

This way of thinking that culture and ethnicity is only about ‘others’ stems from the fact that mainstream Australians come from generations of people born in Australia, a country with a long tradition of seeing ethnicity and culture as belonging solely to ‘people of colour’ or to ‘the others from elsewhere’ not realising that ethnically speaking this includes them. We only have to reflect for a moment on the term ‘culturally and linguistically diverse background’. Commonly rendered as CALD in government policies in Australia, it is a catch-all phrase to describe immigrants and implies that culture and diversity belongs to immigrants, not to ‘us’. An Australian internet search using CALD will yield many hits that make this point evident. Further, newcomers are expected to assimilate into the mainstream culture, as is particularly evident in the process of becoming an Australian citizen for which it is necessary to sit a citizenship test (see http://www.citizenship.gov.au/).

Early thinking in both Australia and New Zealand around ethnicity was related to biological lineage only. To take the New Zealand example, if your father was ‘full Māori’ and your mother non-Māori you were considered by default ethnically ‘half-Māori’ regardless of your cultural beliefs, upbringing or cultural affiliations. In current usage, the term ethnicity is generally used to refer to the ethnic group or groups a person identifies with or feels they belong to. It is also now recognised that individuals may identify with more than one ethnic group. In addition, many New Zealanders and Australians no longer feel any links to the cultures to which their ancestors may have belonged but do not have a well-established alternative ethnic identity either. An example of this is the term ‘New Zealand European’ often used on data collection sheets; there are now many generations of New Zealanders who feel no linkage to their European ancestors and express a reluctance to note this term in relation to their ethnicity (Statistics New Zealand, 2005).

Race

Race is commonly perceived by many as a way to identify differences not only in skin colour and physical attributes but also in language, nationality and religion. According to Rapport and Overing (2007: 15), the idea of race became strong in the Middle Ages as a result of travel lore from ancient Greece and Rome. As they say, ‘the imagery of the brutish giant—the naked, cannibalistic, Wildman … caught the imagination of medieval Europe’. These images were applied to European lower classes and ‘such “inferiorisation” of excluded others became a constant throughout the development of European thought’ (Rapport and Overing, 2007: 15). In the 1940s scientists began to realise that the ‘racial atlas’ of humans did not match what was being learnt about human genetics (Montagu, 1962). There are no significant genetic variations within the human species to justify some kind of grouping of ‘races’. Although the concept of race insists there is some genetic significance that creates variations in skin colour, we know that race has no scientific merit outside of this sociological classification.

So, just like the concepts of health and culture, race is a social construct and, since there are no distinct evolutionary lineages among humanity, there is no biological basis for race. In fact ‘there is more genetic similarity between Europeans and sub-Saharan Africans and between Europeans and Melanesians than there is between Africans and Melanesians. Yet, sub-Saharan Africans and Melanesians share dark skin, hair texture and cranial-facial features, traits commonly used to classify people into races’ (Templeton 1998; also see Templeton 2002; 2007). Nonetheless race categories are often used as ethnic intensifiers, with the aim of justifying the exploitation of one group by another. Although sometimes referred to as ‘scientific racism’ there is in fact no scientific basis to these ideas, as in evolutionary terms all humans are modern humans and there is only one human race genetically speaking.

In keeping with the above, historically the concept of race was used to support claims by Europeans that they were superior to all other people and that this gave them the right to control other people and to take their land, for example. This assumed superiority of some groups over others is also called ‘social Darwinism’, a theory advanced by Herbert Spencer who applied biological evolutionary theory to social life (see Box 4.1) and linked it to ideas such as the Great Chain of Being (see Box 4.2). Because dominant cultures are so used to thinking in terms of race, it is hard for many to accept that the variation in how humans look can be understood in terms of familial descent, not discrete races of humans.

Historically the concept of ‘race’ was used to say some people were inferior to others

• At first women were considered to be inferior to men then ‘people of colour’ were placed lower than white women and so on

‘Social Darwinism’ is the idea that white races are superior

Some people such as Australian Indigenous people have been distinguished, categorised and subordinated across history because of notions that they were of a certain race. This is racism: treating people not on the basis of their humanity but on the basis of ‘race’. Health inequality is often seen as natural and inevitable based on so-called ‘scientific racism’. In fact, social marginality is the result of specific policies, laws, historical events and cultural contexts. A ‘blame the victim approach’ saying ‘they brought it all on themselves’, as with ideas of race and racism, is used to justify or perpetuate structural inequality. Clearly there are differences between people in terms of culture, ancestry and language. There are also different nationalities depending on where one has full citizenship rights. And, as a social construct, race is reclaimed by many of those who were categorised and inferiorised by the use of the concept. The use of the term race, identifying pride in belonging to a group long subjugated on this basis, is a strategic reversal of inferiorisation, so when someone says that they are from a particular race based on history, nationality and geography, their right to reclaim this social construct and use it is this way must be respected.

Health

Üstün and Jakob (2005: 802) discuss the recency of notions such as ‘health’, demonstrating that concepts we take as givens are constructed by humans. These authors also critique the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health. The WHO defines it as: ‘a complete state of physical, mental and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. Üstün and Jakob note that for anyone to maintain a complete state of wellbeing may not be realistic but, for our purposes, it is important that you understand that health is not just about the absence of disease as it may be defined in western medical terms, but is about the whole person within their life context. This contextual aspect is captured in the following definition which was used by the Australian Government in the development of policy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health policy: (Health) ‘means not just the physical wellbeing of an individual but refers to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole Community in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their Community. It is a whole of life view and includes the cyclical concept of life–death–life’ (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party, 1989).

For Māori ‘health’ is also realised through an understanding of a holistic health model. Te Whare Tapa Wha, the most commonly used (but not the only) model, is known as the ‘four cornerstones of health’. This approach compares health to the four walls of a house in which all four walls are necessary to ensure strength and symmetry (Durie, 1994: 70). It can be applied to any health issue affecting Māori from physical to psychological wellbeing. Looking after all aspects of wellbeing (the four walls) are taha wairua (spiritual), taha hinengaro (mental and emotional), taha tinana (physical) and taha whanau (family) considerations. Together all four are necessary and when in balance, they represent ‘best health’. Accordingly, if any one of these components is deficient this may impact negatively on a person’s health (Durie and Kingi, 1997).

When health is understood as being based on a traditional biological model, the attention is on treating disease and symptoms with drugs and/or surgery. Today nurses are taught to care for people within a holistic model, in which the focus is on finding the underlying cause of the symptoms and making lifestyle changes that are conducive to health. There is a strong emphasis on personal responsibility: the person is encouraged to be an active participant in their healthcare plan. The relationship between the person and the healthcare provider is cooperative and complementary. They work as a team. The person therefore is the authority on their body and becomes the expert in caring for themselves. Mainstream holistic healthcare is similar to the Indigenous models previously discussed in acknowledging that all people have physical, intellectual, psychological, social, emotional and spiritual needs. The neglect of any of these areas may reduce the ability to withstand the effects of stress and ill health.

CULTURAL SAFETY

Early nursing understandings in New Zealand (late nineteenth to early twentieth century) and Australia saw culture as a racialised term (the racialised other), used mostly to refer to the visible difference between the original inhabitants and settlers. Nurses were considered to be the ‘humanitarian bearers of civilised health care’ for the natives who were in need of civilising to the perceived dominant culture (Spence, 2001: 52). As the century went on, nursing interest in culture generally declined although some nurses chose to explore it further in university studies in the social sciences and anthropology.

As indicated in the introduction to this chapter, in the 1970s awareness re-emerged regarding the relationships between nurses and patients and the term culture once again developed meaning (Spence, 2001). A new ideology, ‘transcultural nursing’, authored by Madeleine Leininger, was developed. Nurses were to learn the healthcare needs of specific minority ethnic groups. In transcultural nursing perceived cultural differences are learnt and used as a checklist of things to do and not do. In transcultural nursing the nurse undertakes study to learn the specifics of other cultures (mostly within an ethnic sense) and then is deemed to know what individuals from the culture need. The consequence of such an approach is perhaps best summed up in the following quotation:

No need to hear your voice when I can talk about you better than you can speak about yourself … Only tell me about your pain. I want to know your story. And then I will tell it back to you in a new way. Tell it back to you in such a way that it becomes mine, my own. Re-writing you I write myself anew. I am still author, authority. I am still colonizer, the speaking subject and you are now the center of my talk.

(Hooks, 1994: 343)

The key point in this quote is that the unique experience of the client becomes that of the nurse and the client is expected to behave in a particular way because they belong to a particular group. Because the nurse has studied this group they assume they can determine what the person needs. This model was not fully embraced in New Zealand or Australia, although one of the authors of this text can recall her nursing student days when she was directed to visit various cultural (religious) sites to interview key leaders and ask them what their particular beliefs were around healthcare practices. She then had to write a report describing particular health preferences for these groups. An assumption made then was that they would now know how to nurse a person from that group if they come into hospital. However, we do not accept this argument. In this text we focus on holism: students are taught to assess and respond to the biological, psychological and social needs of clients. The transition to culturally safe nursing from this point seems much simpler.

The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council defines cultural safety as:

‘… a nurse or midwife’s understanding of his or her own personal culture and how these personal cultural values may impact on the provision of care to the person, regardless of race or ethnicity. Cultural safety incorporates cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity and is underpinned by good communication, recognition of the diversity of views nationally and internationally between ethnic groups and the impact of colonisation on Indigenous cultures around the world’.

(ANMC, 2007: 1)

In the model of ‘cultural safety’ we promote the position that efforts to describe the practices, beliefs and values of each culture should not occur, as this promotes an ideology of sameness and an erroneous assumption that culture is a simplistic concept which can be captured in lists of things to remember and do. It is this checklist mentality that is intrinsic to transcultural nursing. If this concept was valid think about yourself being the recipient of nursing care. What do you need the nurse to know about you? Will that be the same as the person next door who may come from the same ethnic group as you? What if there are two Vietnamese people in hospital and one happens to also identify as gay? Are their needs the same because they both identify as Vietnamese? We stress that each person is an individual with many unique ways of being. Therefore the underpinning philosophy of cultural safety is that each person should be nursed ‘regardful of all that makes them unique’, encompassing the cultural, emotional, social, economic and political contexts in which they live (Ramsden, 1993; 2002).

Cultural safety is a term initially unique to New Zealand and nursing education. The pioneer of the concept is Irihapeti Ramsden. The concept of kawa whakaruruhau (cultural safety) arose out of a nursing education leadership hui held in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1989 in response to recruitment and retention issues of Māori nurses. The National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission guidelines were initially written by Ramsden in 1991 and further developed by a council committee and Ramsden. By 1992 the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ) had adopted the following definition of cultural safety:

The effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability

(NCNZ, 2009: 9).

Cultural safety relates to the experience of the recipient of a healthcare service. It provides consumers of heathcare services with the power to comment on practices and contribute to the achievement of positive health outcomes and experiences. By this process the meaning and experience of their illness is validated rather than challenged by biomedical understandings. In doing this they also then have the ability to provide feedback on any negative experiences. The process inherent in cultural safety education includes exploring the culture of nursing, recognising the impact that personal culture has on professional practice and the subsequent power relationship between nurses and the consumers of nursing care (NCNZ, 2005). Cultural safety then ‘… contends that people are so diverse that teaching simple ritual and custom stereotypes and rigidifies ideas of culture and does not allow for human diversity (nurse or patient), nor does it take into account historical effects and socioeconomic status’ (Ramsden, 1996, cited in Ramsden 2002: 110). Ramsden (2002: 109) explained that:

Cultural safety is based in a postmodern, transformed and multilayered meaning of culture as diffuse and individually subjective. It is concerned with power and resources, including information, its distribution in societies and the outcomes of information management. Cultural safety is deeply concerned with the effect of unequal resource distribution on nursing practice and patient wellbeing. Its primary concern is with the notion of the nurse as a bearer of his or her own culture and attitudes, and consciously or unconsciously exercised power.

Ramsden talks here about the nurse as a bearer of culture. She maintains that nurses must understand their own culture in order to fully respond to the culture of others.

Self-reflexivity and self-awareness

Self-reflexivity or self-awareness is the ability to locate oneself in terms of culture of origin and culture of choice. Self-awareness of one’s own culture, biases and beliefs is a necessary step in culturally safe practice. If we learn about others only to become culturally competent we are acting in a self-limiting way and at risk of reinforcing stereotypes. To truly understand how to relate to others, you must first understand yourself; this requires personal self-reflection and self-critique of the various personal, historical and social influences that impact on you. Students often find this process of self-awareness highly rewarding, as is shown in this student’s comment: ‘The personal reflection that was common in this unit opened a side of myself that I had never ventured to, made me really think where I had come from etcetera.’

In Box 4.3 below are some guidelines to help you become self-aware.

Box 4.3 STRATEGIES FOR SELF-AWARENESS

• Think about your own cultural groups.

• What is your way of living within your group/s? (Think about age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability).

• Are there groups within these ranges that you can identify with?

• Think about the agents of socialisation that have impacted on you as you have grown up (family, school, peers, the media).

• What have you learnt from them regarding healthcare practices?

• What are the values you have learnt from your family?

• Do you still hold these values today?

• Do these values guide your decision making and how you see the world?

• Are they something that (may) affects your practice as a nurse?

• Think about the customs you and your family have around events such as birthdays, Christmas, funerals, weddings.

• What about the types of food you eat?

• How many people live in your house? Is it just your immediate family or is it the extended family?

A newly graduated registered nurse in New Zealand reflecting on her cultural safety education said:

I can remember finding the concepts quite confusing initially. I think it was because I had trouble distinguishing them from a more transcultural perspective, as I thought it was concerned with learning about specific cultural differences and applying those in practice to various groups (i.e. Māori, Muslims etc). My understanding of cultural safety now is about knowing my own assumptions and being mindful about how this might impact on interactions. There was an element of learning specific cultural requirements (like Tikanga protocols) and I remember enjoying this very much. On the whole though, cultural safety prevents us taking a one-size-fits-all approach to care.

The misunderstandings

Many individuals when they first come across the term cultural safety immediately think about race and ethnicity. Common statements heard are ‘when I nurse people I don’t see colour; we’re all equal’; and ‘I treat everyone the same’. The problem with this thinking is that treating everyone the same is a denial of inequality. If colour does not matter, then why are there so many disadvantages or even entitlements that go with your skin colour or with your family’s cultural membership? An individual’s culture of origin and colour does matter in a culturally unsafe world as it brings different privileges, assumptions and varying levels of influence over health outcomes. Consider this story by nurse academic Professor Margaret Pharris (2009: 10):

Upon arrival at the ED, I took a report from an excellent White nurse. She and a very fine White physician had both been caring for two young women who happened to arrive to the ED at the same time … both presented with 9 out of 10 flank pain, indicative of kidney stones. After receiving report, I went to assess the patients. The first … a White woman, was lying on a[n] ED bed dressed in a patient gown and wrapped in a warm blanket. She had received a significant amount of morphine … The second … a Black woman, was in a fetal position in the procto room, was still in her street clothes, and had received nothing for pain … it hit me that I might not have noticed this inequality had I not come directly from the dialogue about racism and health care. I wondered how much else I was missing?

The power you have as a nurse in a healthcare relationship is well illustrated here and often is about your proximity to the cultural norms of the country you are in. Reflecting similar problems in Australia the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission reports that: ‘Available data tells us that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people do not systematically receive the levels of care, investigation and follow-up that clinical pathways recommend’ (NHHRC 2008: 211).

Biculturalism is a key element of cultural safety theory and asserts that all encounters are bicultural as they involve the culture of the nurse and the culture of the client. This is in contrast to transcultural approaches that do not recognise the power differences inherent in approaches that always assume the client is the exotic one and that nurses and health systems are somehow free of culture. Furthermore, individuals have different abilities to exert control and influence in situations or relationships. Many power relations exist within our social, economic and political structures and institutions. Power and control are often hidden or unwritten and are usually vested in members of the dominant group.

Culturally safe nursing is the effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. The nurse delivering the nursing service will have undertaken a process of reflection on their own cultural identity and will recognise the impact that their personal culture has on their professional practice. This is about recognising our own values and beliefs and being able to acknowledge that others will have similar or very different values and beliefs to ours. That does not make theirs wrong. It is by acknowledging and respecting the beliefs of others that we minimise the impact of cultural dominance in healthcare.

Unsafe cultural practice is any nursing practice which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and wellbeing of the individual (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2009: 4). Cultural safety is about absence of discrimination and about behaviour that ensures that staff and clients are valued and respected and are being included in decision making. The primary focus needs to be on the bicultural partnership in which each nurse–client encounter is a genuine meeting of two different and unique cultures. Both parties engage in this meeting in the knowledge that they bring their own unique culture to the encounter (Ramsden, 1993).

Cultural safety is underpinned by communication, recognition of the diversity in worldviews (both within and between cultural groups) and the impact of colonisation processes on minority groups. Cultural safety is an outcome of nursing education that enables a safe, appropriate and acceptable service that has been defined by those who receive it. As Ramsden put it: ‘In the future it must be the patient who makes the final statement about the quality of care which they receive. Creating ways in which this commentary may happen is the next step in the cultural safety journey’ (Ramsden 2002).

A new graduate nurse reflecting on her experience of learning about cultural safety as a student describes a clinical situation which helped her make sense of her learning:

Our cultural safety education was awesome; I just went to an in-service session at [hospital] a few weeks ago about cultural competency, and a lot of the stuff we were taught in nursing school was in there. Cultural awareness is a massive aspect of my nursing … the best point I took from it all was to take cues from the patient/service user. If I’m not sure, I ask the service user directly … they know their own culture best. I recently had a patient with a ‘Buddhist outlook on life’; I offered to access some support for him, but he declined stating that he doesn’t practise; he just shares some of the same views. So it would have been inappropriate to access that support for him, however it was appropriate to ask. Another person might have the same view AND want to access spiritual support … I also think the biggest thing to cultural safety is being aware of my own culture. I’m working on this all the time and exploring it during my supervision.

See also Box 4.4.

Box 4.4 THE PROCESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING CULTURAL SAFETY IN NURSING PRACTICE

• Know your own journey and accept that your way of knowing and doing things is not the only way

• Seek relevant cultural knowledge—ask questions

• Engage community accompaniment—find allies, contact cultural advisors

• Always be respectful and collaborative

• Remember that therapeutic nursing practice is grounded in relationships

• Be aware of your timing. Ask yourself ‘Is this the right time to be offering this particular form of service?’

• Focus on family-centred care when possible

• Remember the best solutions are found through collaborative problem solving rather than expert/authority

• Every situation should be reciprocal and mutual

• Be aware that old and new forms of colonialism deplete cultures, communities and roles for families

• Think about informed consent and what you may need to do to ensure it is understood

Cultural safety education

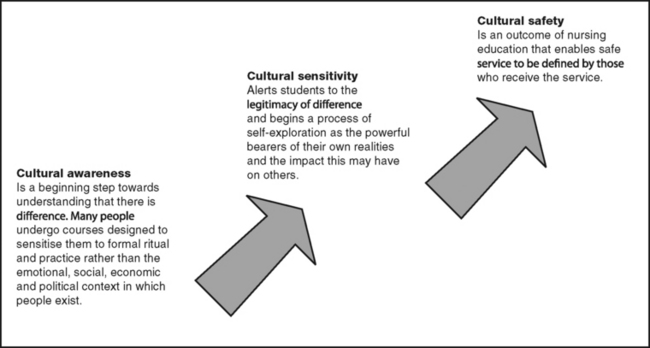

The purpose of cultural safety in nursing education extends beyond the description of practices, beliefs and values of ethnic groups. As we now know, confining learning to rituals, customs and practices of a group can be misleading and does not address the complexity of human behaviours and social realities. The assumption that cultures are simplistic in nature can lead to a checklist approach by service providers, which negates diversity and individual consideration. Cultural safety education is focused on the knowledge and understanding of the individual nurse rather than on attempts to learn accessible aspects of different groups. A nurse who can understand their own culture and the theory of power relations can be culturally safe in any context (Box 4.4 and Fig 4.2).

According to Ramsden, cultural awareness is the beginning step in the process of learning cultural safety, which involves understanding difference, while cultural sensitivity is an intermediate step during which self-exploration by the student begins. Cultural safety is an outcome of learning that enables a safe, appropriate and acceptable service, defined by those who receive it. Cultural safety is underpinned by communication, recognition of the diversity in worldviews (both within and between cultural groups) and the impact of colonisation and ongoing marginalisation on minority groups.

CULTURAL COMPETENCE AND CULTURAL SAFETY

As we indicated at the beginning of this chapter, there are many terms and approaches used to describe what is often called being ‘culturally competent’. There are countless ways by which this can be achieved and here we’ve focused on the approach of cultural safety. In addition, there are many definitions of cultural competence that combine aspects of cultural safety and transcultural nursing, the argument being that nurses need cultural self-awareness and knowledge about the health beliefs and practices of various cultures (for example, see Munoz and Luckmann, 2005: 47–49; Hines-Martin and Pack, 2009: 159–160). The concept of cultural self-awareness fits well with the concept of cultural safety as ‘cultural safety does not ask nurses to discover the cultural dimensions of any culture apart from their own’ (Dowd et al, 2005: 9, cited in Eckermann et al 2006: 166). Likewise, Fitzgerald’s definition (1999, cited in DETYA, 2001) says that cultural competence is ‘the ability to identify and challenge one’s cultural assumptions’.

Many students come to courses on culture expecting to learn all about other cultures. One of the authors recalls a student who, after doing a course on cultural safety, complained, ‘I don’t even know what that headdress that Muslims wear is called!’ This of course brings us to the very crux of the matter: there are as many names for the headdress as there are cultural and linguistic groups who wear it. With so many different cultures and so much variation within culture it is actually quite impossible to expect students to learn about the diverse cultures that they’ll encounter in their work. As Warren (2009) argues, generalising approaches to cultural competence conceptualises cultures as bounded wholes that exist out there to be learned, rather than appreciating culture as a broad, dynamic relational concept as used in cultural safety.

Becoming culturally safe is not a one-lesson program but rather a lifetime journey of study and learning. There are several discrete areas in which you must have knowledge:

1. Your own personal cultural identity

2. The culture of the nursing profession

3. The culture of the healthcare system

4. The cultural identity of the client as they describe it to you.

Nursing students will notice that more and more institutions are mandating that those who practise must take cultural issues into account when providing healthcare and we turn to these requirements in Australia and New Zealand after first considering some crucial aspects of nursing care.

COMMUNICATION

There are many forms of illegal discrimination based on ethnicity, colour or national origin that frequently limit the opportunities of people to gain equal access to healthcare services. It is said that ‘language barriers have a deleterious effect on health care, patients are less likely to have a usual source of health care, and have an increased risk of non adherence to medication regimens’ (Flores, 2006). The Australian and New Zealand healthcare systems assume strong English proficiency in healthcare encounters. However, for people who do not speak English or for whom it is a second or third language, seeking care in healthcare settings such as hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, day care centres and mental health centres, language is a considerable barrier. As we saw in the section on population statistics, for each context there is tremendous diversity in people’s English language proficiency.

Those who are limited in their ability to speak, read, write and understand the English language encounter countless language barriers that can result in limiting their access to critical public health, hospital and other medical and social services to which they are legally entitled. Many health and social service programs provide information about their services in English only. When persons whose first language is not English seek healthcare at hospitals or medical clinics, they are frequently faced with receptionists, nurses and doctors who speak English only. These language barriers severely limit the ability to gain access to these services and to participate in programs. In addition, the language barrier often results in the denial of medical care or social services, delays in the receipt of such care and services or the provision of care and services on the basis of inaccurate or incomplete information. For example, with regard to medication, if a person who has a minimal understanding of English is not given clear understandable instructions regarding their medication, adherence to or incorrect dosage may be a problem. Services denied, delayed or provided under such circumstances could have serious consequences for both clients and providers of healthcare.

Chapter 6 describes in more detail how to communicate with people who do not understand English, how to interact with interpreters and what services are available when no interpreter is available. It is vital that interpreters be present who not only serve to verbally translate the conversation but who are also able to assist you with asking the assessment questions above.

Family means different things to different people and it is very difficult to provide one definition of family. One of the biggest mistakes made in healthcare happens when the concept of family is considered from a mainstream understanding only or from rigid takes on Indigenous traditional kinship structures. In contemporary mainstream society, the concept of a nuclear family (mum, dad and children) remains the most powerful normative preference. There are occasions when clients’ circumstances differ from this ideal, when the people they designate as their family are not regarded as family at all by health services and, at times, are considered deviant.

As Dench et al indicate (2007: 75) it is crucial to think about how a client’s family functions with regard to healthcare decisions and hospital visiting preferences. This is especially important for Indigenous clients who may designate next-of-kin and family relatedness in ways that are unfamiliar to nurses whose knowledge base is grounded in the assumptions made by the cultures of medicine and nursing. These nurses focus their care decisions on individuals and, for them, the idea of bounded nuclear families is entrenched. Consider the following scenario:

A young Indigenous man was admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) following a serious suicide attempt. His mother rang one of the contributors to this text (Cox, a non-Indigenous person) and requested that she go to the ICU to visit him. At the hospital ward, staff insisted that only close family could be allowed in to see the man. The problem was that the man’s close family was several hundred kilometres away. An Indigenous health worker was at the ICU and knew of the author’s long-term relationship with the family and convinced the nurses that she should be allowed to visit. When the young man was moved to a general ward he introduced the author to the doctor as ‘my sister’.

We encourage you to think very differently about family to encompass such circumstances. We know that in Australia and New Zealand families are diverse, so it is important we understand how to ensure family is considered in an individual’s healthcare, according to the context described by that individual. Think about who you include when you talk about your family. You might live with people you regard as family even though they are not blood relatives. Who can correctly say who a client’s next-of-kin is? It might be the birth family or those who raised the person or perhaps the family they have created with a partner. There are numerous possibilities. How will you support homosexual relationships and struggles to have partners accepted as spouses and next-of-kin? How about those situations in which children have two mothers or two fathers? Think about people with longstanding disabilities estranged from their families many years ago when institutionalised. There are times when the person with a disability want staff members contacted because they are their significant others, rather than their birth families.

Making assumptions in this area of nursing care can bring significant distress for your clients. As nurses you must be aware that your cultural assumptions are just that—they are not universal ways of being and you need to be alert for different ways of understanding the world and social institutions such as the family. In sum, the concept of family and who is important and who can make decisions within a family can be decided only by individuals in the context of their particular family or in the face of their inability to do so by members of the family itself.

CULTURAL IDENTITY

Our identities as cultural beings are not only based on being born into a particular cultural milieu but are strongly related to our experiences as we go through life. Just as all members of a single family are not exactly the same and in fact may hold quite different beliefs and values to their parents and siblings, those who identify as belonging to a particular culture do not experience or express that cultural identity in the same way. In line with the broad definition of culture used in cultural safety, aspects of a person’s cultural identity are influenced by their ethnicity, their gender, their ability or disability, their education and their status within society as members of either dominant or minority groups. In addition, many people socialised in cultures in which traditional healthcare resources are used, such as in some Indigenous communities, may prefer to use this type of care even when residing in a mainstream cultural setting with mainstream healthcare resources available. It is therefore not possible to teach you the cultures, religions and ethnicities that shape a person’s world view as this will be unique to each individual. However, it is important that you understand that differences exist and are legitimate.

Spirituality, religion and philosophy

One possible component of a person’s cultural identity is their religion or spirituality but nurses must be mindful that many people hold a secularist philosophy and will not appreciate discussions of religion or spirituality. This point is especially relevant for those nurses who hold strong religious or spiritual beliefs themselves, as at times they may not appreciate how distressing it is to non-religious clients to have these issues raised. Nonetheless spiritual or religious factors are important to many clients, but these dimensions are often overlooked in health assessment. If religion or spirituality is an integral component of a person’s culture, their beliefs may influence their explanation of the cause(s) of illness, perception of its severity and choice of healer(s). In times of crisis, such as serious illness and impending death, religion and spirituality may be a source of consolation for the person and for their family. Religious or spiritual leaders may exert considerable influence on the person’s decision making concerning acceptable medical and surgical treatment, choice of healer(s) and other aspects of the illness.

Religion and spirituality then can play a most significant role in the ways people practise their healthcare. There are countless health-related behaviours promoted by nearly all religions or spiritualities. The following list presents selected examples: ceremonies and rituals, meditating, exercising and maintaining physical fitness, getting enough sleep, being vaccinated, being willing to have the body examined, undertaking a pilgrimage for health reasons, telling the truth about how you feel, maintaining family viability, hoping for recovery, coping with stress, undergoing genetic screening and counselling, being able to live with a handicap and caring for children (Levin, 2001).

Religion and spirituality can give people a frame of reference and a perspective with which to organise information. Their belief vis-à-vis health can help to present a meaningful philosophy and system of practices within a system of social controls having specific values, norms and ethics. These are related to health in that adherence to a religious or spiritual code is conducive to spiritual harmony and health.

Religious and spiritual concerns evolve from and respond to the mysteries of life and death, good and evil and pain and suffering. For example, illness is sometimes seen as punishment for the violation of religious codes and morals.

In healthcare settings, you will frequently encounter people who find themselves searching for a spiritual meaning to help explain their illnesses or disabilities. Some healthcare providers find spiritual assessment difficult because of the abstract and personal nature of the topic, whereas others feel quite comfortable discussing spiritual matters. Comfort with and mindfulness of your own spiritual beliefs is the foundation to effective assessment of spiritual needs in others (Andrews and Boyle, 2003) including the ability to assess whether or not a client requires a discussion of such matters.

Time orientation

Inherent in socialisation is the approach that people take to time. One of the major areas in which cultural conflicts between nursing culture and clients occur is the failure to understand each other’s perception of time. According to FR Kluckhohn (1990), there are three major ways in which people can perceive time.

1. The focus may be on the past, with traditions and ancestors playing an important role in the person’s life. For example, some people hold beliefs about ancestors and tend to value longstanding traditions. In times of crisis, such as illness, a person with a value orientation emphasising the past may consult with ancestors or ask for their guidance or protection during the illness.

2. The focus may be on the present, as in nursing culture, with little attention being paid to the past or the future. Nurses and health systems are especially concerned with tasks and goals focused on ‘now’, and the future is perceived as vague or unpredictable. Some clients will also be focused on now and nurses may have difficulty encouraging preparation for the future—for example, for discharge from the hospital or for future side effects or adverse reactions from the medication. In addition, some people may fail to see the value of childhood immunisations or those aimed at preventing the flu, hepatitis or other conditions afflicting adults.

3. For some people, the focus is on the future, with progress and change being highly valued. The person may express discontent with both the past and the present. In terms of healthcare, they may inquire about the ‘latest treatment’ and most modern equipment available for a particular problem and may express concern with nurses or physicians they perceive as old fashioned.

To take just one example, in the Australian and New Zealand contexts the way different people value time may impact on the way they assess priorities to do with their healthcare. There could be problems with keeping appointments, adhering to medication regimens or differing priorities where family business may take precedence over appointments and the use of resources on personal health. It is important that nurses seek to understand what is happening in people’s lives to limit a sense of frustration and to prevent applying uncritical assumptions and judgments to people’s health and illness behaviours.

CAUSES OF ILLNESS AND DISEASE

Disease causation may be viewed in three major ways: from a biomedical or scientific, a naturalistic or holistic or a magico-religious perspective.

Biomedical

The view that dominates in our health system is called the biomedical or scientific theory of illness causation, and is based on the assumption that all events in life have a cause and effect, that the human body functions more or less mechanically (i.e. the functioning of the human body is analogous to the functioning of a car), that all life can be reduced or divided into smaller parts (e.g. the reduction of the human person into body, mind and spirit) and that all of reality can be observed and measured (e.g. intelligence tests and psychometric measures of behaviour). Among the biomedical explanations for disease is the germ theory, which posits that microscopic organisms such as bacteria and viruses are responsible for specific disease conditions. Most educational programs for physicians, nurses and other healthcare providers embrace the biomedical or scientific theories that explain the causes of both physical and psychological illnesses. When clients come to hospitals they may react to this environment with the various stages of culture shock, that is, a state of disorientation or an inability to respond to the behaviour of a different cultural group (in this case the culture of nurses and doctors) because of its sudden strangeness, unfamiliarity and incompatibility with their perceptions and expectations.

Naturalistic

Another way in which people explain the cause of illness is from the naturalistic or holistic perspective: the belief that human life is only one aspect of nature and is a part of the general order of the cosmos. People with this perspective may believe that the forces of nature must be kept in natural balance or harmony. The naturalistic perspective posits that the laws of nature create imbalances, chaos and disease. People embracing the naturalistic view use metaphors such as the ‘healing power of nature’, and they may call the earth ‘Mother’.

Magico-religious

The third major way in which people explain the causation of illness is from a magico-religious perspective. The basic premise is that the world is seen as an arena in which supernatural forces dominate. The fate of the world and those in it depends on the action of supernatural forces for good or evil.

Healing and culture

When self-treatment is unsuccessful, the person might turn to the lay or folk healing systems, to spiritual or religious healing or to scientific biomedicine. All cultures have their own preferred lay or popular healers, recognised symptoms of ill health, acceptable sick role behaviour and treatments. In addition to seeking help from you as a biomedical/scientific healthcare provider, clients may also seek help from traditional or religious healers. The variety of healing beliefs and practices used by the many populations found in Australia and New Zealand far exceeds the limitations of this chapter. It is important, however, that you are aware of the existence of various practices and recognise that, in addition to folk practices, many other complementary healing practices exist.

Of course, it is possible to have a combination of world views, and many people are likely to offer more than one explanation for the cause of their illness. As a profession, nursing largely embraces the scientific/biomedical world view, but some other aspects are gaining popularity, including techniques for management of chronic pain, such as acupuncture, herbal therapies, hypnosis, therapeutic touch and biofeedback. For cultural safety it is imperative that nurses engage in power sharing and be prepared to both listen to and respect how their clients understand their own illnesses.

CULTURAL EXPRESSION OF ILLNESS

Expression of pain

To illustrate the manner in which symptom expression may reflect the person’s cultural background, let’s use an extensively studied symptom—pain. Pain is a universally recognised phenomenon and it is an important aspect of assessment for people of various ages. Pain is a very private, subjective experience that is greatly influenced by cultural background. Expectations, manifestations and management of pain are all embedded in a cultural context. The definition of pain, like that of health or illness, is culturally informed. The word pain is derived from the Greek word for penalty, which helps explain the long association between pain and punishment in Judeo-Christian thought. The meaning of painful stimuli, the way people define their situation and the impact of personal experience all help determine the experience of pain.

Some cross-cultural research has been done on pain with the acknowledgment that it may be perceived as a multidimensional experience. For example, Fenwick (2006) did work on the experience of pain amongst Central Australian Indigenous people. Pain has been found to be a highly personal experience, depending on cultural learning, the meaning of the situation and other factors unique to the person. Therefore pain should be explored not only in consideration of the physical or psychological experience but also the social, spiritual and cultural perceptions. Silent suffering has been identified as the most valued response to pain by healthcare professionals. The majority of nurses have been socialised to believe that in virtually any situation, self-control is better than open displays of strong feelings.

Disease prevalence

It is well known that diseases are not distributed equally among all segments of the population. For several generations, the mainstream population in Australia and New Zealand has enjoyed improved health status. Despite this fact, as discussed previously, there continues to be major disparity in deaths and illnesses experienced by Indigenous people and minority groups. Poverty, lack of employment opportunities, poor housing, low levels of education and other socially marginalising issues such as scientific, institutional and personal racism play a central role in health disparities. Space does not permit us here to overview the many available health statistics for different population groups but links are provided at the end of this chapter.

AUSTRALIAN NURSING STANDARDS

In 2010 Australia moved to a national registration system under the newly formed Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia under the Australian Health Practitioner Registration Agency (AHPRA). The standards for Registered Nurses set by the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC) in 2008 have been adopted by AHPRA. According to the council’s standards a registered nurse provides evidence-based nursing care to people of all ages and cultural groups including individuals, families and communities (ANMC, 2008: 2). Of particular relevance is the following (ANMC, 2008: 12) in section 9.5 of their standards. A registered nurse:

• facilitates a physical, psychosocial, cultural and spiritual environment that promotes individual/group safety and security

• demonstrates sensitivity, awareness and respect for cultural identity as part of an individual’s/group’s perceptions of security

• demonstrates sensitivity, awareness and respect in regard to an individual’s/group’s spiritual needs

• involves family and others in ensuring that cultural and spiritual needs are met.

For the full 2008 Registered Nurse Competency Standards go to: http://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/en/Codes-and-Guidelines.aspx

In 2003 the ANMC released a position statement for the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health and cultural issues in courses leading to registration or enrolment and these were updated in 2007 (Box 4.5).

Box 4.5 SUMMARY OF THE ANMC’S POSITION STATEMENT ON ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER PEOPLES’ HEALTH