Chapter 11 Rural and remote area nursing

1. Describe how the demography of remote and rural areas influences health and healthcare.

2. Identify the difference in health and healthcare status between remote and rural areas.

3. Describe Indigenous definitions of health.

4. Outline the key concepts of cultural safety.

5. Describe the characteristics of rural and remote area nursing.

6. Describe the rewards of nursing in a rural or remote area.

Introduction

New Zealand and Australia differ significantly in size and population. In Australia, 66% of the country’s 22.16 million people live in metropolitan regions, with 31% residing in regional and rural areas, and only 3% living in remote or very remote areas.1–3 On the other hand, 86% of New Zealand’s 4.3 million people live in metropolitan areas, 12.4% live in rural areas with varying degrees of urban influence and only 1.6% live in highly rural remote areas.4 The category of ‘highly rural remote’ is used by Statistics New Zealand to classify areas in which there is very little influence on employment from urban areas or in which there is a very small population in employment.4 Australia has a population density of 2.6 persons per square kilometre living mostly in coastal areas, with 0.1 person per square kilometre in the Northern Territory.5 New Zealand has a slightly lower population density of 1.5 persons per square kilometre across the whole country.4

Indigenous health is a major issue in both New Zealand and Australia, where a higher percentage of the Indigenous population lives in rural and remote areas. Although 32% of Indigenous Australians live in metropolitan areas, proportionally their numbers increase with remoteness, with 43% living in regional areas and a further 25% living in remote or very remote areas (compared with 3% for non-Indigenous Australians).1,2 In New Zealand, rural areas with less than 10,000 people average 20% of the Māori population. However, there are high concentrations of Māori in the far north and east of the North Island.6 In the North Island, 17.3% of the Māori population live in highly rural remote areas in comparison to 7.3% of Māori in the South Island.4 The population in many remote and rural areas in both countries is highly mobile, with some towns and communities accommodating large influxes in population at certain times due to seasonal work, sporting and cultural events, and tourism.

These factors combine to present nurses working in these areas with conditions and challenges unique to the profession. Both remote area nursing and rural nursing share common characteristics, but there are also distinct differences.

Definitions of rural and remote areas

There are many different ways of defining ‘rural’ and ‘remote’. In Australia, people often refer to ‘the country’, ‘out bush’, ‘the bush’ or ‘the outback’. Isolation and limited accessibility to services are synonymous with the term ‘remote’. There is a blurring of boundaries between rural and remote areas. In Australia, each state and territory arranges its health services differently, but recent national reforms, particularly in primary healthcare, are heralded to bring some consistency in funding and policy with local or regional innovation and delivery.7 Lack of uniformity and services distinguish the two areas, with external influences, such as commodity prices, international markets and epidemics, affecting the economic and civic robustness of the town. A common distinction between rural health services and remote area health services usually involves the presence (rural) or absence (remote) of a medical officer, although this is changing, with funding increasingly becoming available for doctors in remote areas. The other main factor that distinguishes rural and remote areas is that rural communities commonly have a 24-hour healthcare facility with inpatient capabilities, whereas most remote areas rely on health centres that are open during office hours and an on-call service after hours.

Many towns that would describe themselves as rural have a healthcare service that better fits the definition of remote in its characteristics. These characteristics include healthcare services that are integrated within one facility, where healthcare professionals provide multidisciplinary care across the life span for acute, chronic, aged care, preventative and public health. Volunteer and community services, such as The Red Cross, the Country Women’s Association (CWA) or St Vincent de Paul, are only likely to be found in towns with larger populations.

Rural and remote areas pose particular challenges to the provision of healthcare services. In Australia, these challenges include: vast distances; extreme climates; hostile environments as a result of bushfires, cyclones or floods; sparse, dispersed populations; little public transport; fractured regional infrastructure; cultural diversity; poverty; poor health status; and a widening gap in health status.8 To a lesser extent these challenges are also apparent in rural areas of New Zealand. Large distances, geographical obstructions, small remote populations, deprivation, high concentrations of Māori and seasonal fluctuations due to tourism are all features influencing the need for and provision of healthcare services.6

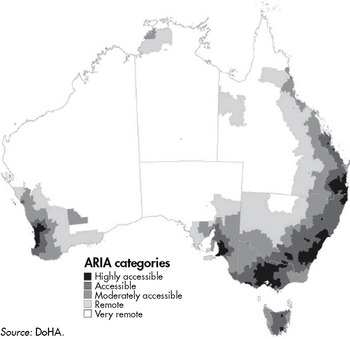

Several classifications are used in Australia to define ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ and these are often used to allocate both services and resources. The most commonly used systems are either the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA or ARIA+) classification9 or the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Remoteness Areas classification. The ASGC represents residents’ access to goods and services, and is based on the road distance to the service centres, thus distinguishing major cities, regional centres close to major cities (inner regional areas), regional centres some distance from other large service centres (outer regional areas), and remote and very remote areas.10 These classification systems employ a geographical approach to defining remoteness and do not take into account socioeconomic status, population size or cultural factors.9 Figure 11-1 shows the ARIA classification system for Australia. It demonstrates very clearly the density of the population in the coastal regions, particularly in eastern and south-eastern Australia, resulting in the majority of the continent being classified as rural and remote communities.

Figure 11-1 Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA) categories in Australia.

Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Rural, regional and remote health: a guide to remoteness classifications. Canberra: AIWH; 2004.

In New Zealand, there is no index to define communities according to degree of remoteness so resources cannot be allocated in this way.6 However, the Statistics New Zealand Urban Rural profile classifications are now being used in reports such as the National Advisory Committee Report on Rural Health.11 The major funding is directed through Primary Health Organisations (PHOs). These organisations, under the umbrella of District Health Boards, are responsible for funding healthcare services for their enrolled population.12 Some targeted funding for rural health is available through PHOs.12 However, most PHO funding subsidises services based on enrolled population factors such as age, deprivation, gender, ethnicity and high health user needs.12 The deprivation index is worked out on a scale of 1–10, with areas with a score of 10 being rated as most deprived, both materially and socially. Variables used in assessing deprivation include income level, unemployment, access to telephone and private transport, single parent families and those on means-tested benefits, qualifications, home ownership and living space.13 In New Zealand, the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (partnership, participation and protection) are major influences on the provision of healthcare services in rural communities.6

Regardless of how rural and remote areas are classified, the people residing in rural and remote areas require healthcare service delivery.

Remote area and rural nursing

The reality of nursing in rural and remote areas is vastly different from the urban setting. Nurses working in these areas usually work at a level of both advanced and extended generalist practice, often with limited or no medical support on site or even in the community.

REMOTE AREA NURSING

Nurses in remote areas are required to manage medical emergencies and trauma, usually with the only medical assistance via telephone several hundred kilometres away. However, emergency care is only a small part of their work. They provide age appropriate ‘wellness’ check-ups (e.g. well women’s, men’s and children’s checks) and healthcare, acute and less urgent care across the life span; detect and monitor chronic disease; and provide end-of-life care. Their skills include the ability to examine, diagnose, prescribe (in Australia only) and dispense medications as part of routine practice. They also undertake community development and health promotion activities following a Primary Health Care approach and conduct public health programs, including screening and surveillance, early intervention and prevention of illness advice. Often this all occurs in a cross-cultural environment that operates with different languages, knowledge and cultural systems from that of the healthcare providers.

Nurses who work in remote areas in Australia are called remote area nurses or, more commonly, RANs. A remote area nurse can be defined as a Registered Nurse who is a specialist generalist and who works as an advanced practitioner in remote or isolated practice. The remote area nurse’s scope of practice encompasses many aspects of Primary Health Care, including continuous, comprehensive and coordinated healthcare of individuals and their families across the life span within the context of their family and community.

RURAL NURSING

Unlike remote area nursing, there is no one Australian, New Zealand or international definition of rural nursing. Instead, rural nursing is defined ‘by default’.14 In other words, it is the lack of other healthcare professionals that determines the scope of practice of the rural nurse.14,15 The number of non-nursing healthcare professionals differs considerably between rural communities, as does the model under which they may be employed. For example, many rural towns have at least one general practitioner; however, few have full-time medical specialist services. Additionally, most rural towns cannot economically support full-time allied healthcare services (such as physiotherapists) and some towns may not be able to attract a pharmacist. While there are some visiting services to some towns, the majority of rural people have to travel to a larger centre to seek specialist or allied healthcare services.

Rural nursing is regarded as a speciality within nursing.16 However, this specialist role is that of the generalist. Like remote area nurses, rural nurses usually work in an extended or advanced practice role. In the larger rural centres, nurses may have a narrower specialist role; for example, a nurse may work in an operating theatre or be a continence nurse advisor within community health. Many other nurses in smaller centres are specialist generalists but may also have a particular area of increased expertise; for example, oncology nursing. In Australia, New Zealand and internationally, rural nurses have a more generalist role as the population declines and nurses have to work with remotely located allied healthcare and medical practitioners. Generally, the larger the centre, the less generalist the role. Thus, like remote area nurses, rural nurses need a broad range of knowledge and skills.17–19

History of remote area healthcare services in Australia

To gain a better understanding of ‘where we are now’ it is advantageous to examine the history of the development of healthcare services in rural and remote areas. Today, there are six main types of healthcare services connected to remote areas: state-based healthcare services; church and charitable organisation services; industry-based healthcare services, such as clinics at mines and railways, or in pastoral, tourism or fishing towns; prison and detention centre services; service agreement healthcare services; and community-controlled healthcare services. The latter two are predominantly Indigenous health services. One further category, aeromedical or retrieval services, supports all of these; it fits into the service agreement category but stands beside it in that it has some unique features.

The operational aspects of these healthcare services are influenced by the social, economic, political and philosophical changes throughout the last 150 years. In remote Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, healthcare services were generally run by missions and charitable organisations staffed mainly by remote area nurses. This established a pattern that remains today. The presence of remote area nurses remains a key feature in most remote healthcare services and the expectations from employers and the community of remote healthcare professionals in many areas often still reflect a ‘missionary’ or ‘caretaking’ attitude.

Throughout the evolution of healthcare services there have been two main target groups: non-Indigenous people and the Indigenous population. Although interconnected, the services have evolved in two streams, at times following the same path and at other times being quite separate.

NON-INDIGENOUS HEALTH SERVICES

In the early days of settlement of remote and rural Australia, services were established for non-Indigenous people and were generally run by Christian and charitable organisations. Examples include the Australian Inland Mission and community groups such as the Victorian Bush Nursing Association and Silver Chain. In the post–World War II period, the CWA led the establishment of maternal and child healthcare centres.

The Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS), which provides a ‘mantle of safety’, has been an important development in providing access and support to healthcare services in remote Australia. Although state and federal governments have taken an increasing role in funding healthcare services in remote Australia, there is no single model of healthcare service or service agreement. The RFDS remains a private, non-government organisation that is reliant on state, territory and community support for funding. The RFDS now services most regions across remote Australia. However, it was originally established for non-Indigenous people on stations and remote towns, who have historically maintained a sense of ownership and a commitment to its ongoing support. With changing attitudes and demands, the RFDS has gradually increased its involvement in Indigenous health, responding to urgent and emerging healthcare needs. Remote area nurses consider the RFDS a lifeline in their practice.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Background

Sarah is a 27-year-old nurse who has been working in a remote Aboriginal community for 8 months. She and an Aboriginal health worker, Marita, spend Wednesday afternoons at the Women’s Centre, where the women meet for basket weaving. Over the past 8 months, with support from Marita, Sarah has been getting to know the women and has become more involved in their conversations and stories. Over the months the women have been discussing the problems of young girls not listening to the older women and having babies early but not looking after them properly.

Working with rural Indigenous women

One Wednesday Sarah asked the women how they thought they could help re-establish cultural tradition where older women played an important role in educating young women about culture, birth and parenting. One old lady, Margaret, suggested that they need to engage the women early, before they have the babies. The conversation soon became a lot more lively as different suggestions were put forward. After a while the women had all agreed that perhaps a good place to start was at the school. Marita and some of the senior women would approach the school and suggest that they have a regular time to visit the teenage girls and talk about culture and childbirth. Sarah thought she could also assist with education about sexual health but realised it was important for the women to keep control of the situation.

Over the next few months Marita and some senior community women visited the school every Thursday morning. Sarah was sometimes invited along if there was a particular health issue that had been identified. Within 6 months Sarah noticed that some young pregnant girls were coming to the clinic earlier in their pregnancy than before. She was unsure if this was related to the Thursday morning education sessions at the school and asked Marita, who thought it could be related as they often talked about pregnancy and the need for early check-ups.

INDIGENOUS HEALTH SERVICES

Health services for Indigenous people in remote Australia today are predominantly directly, or indirectly, state- or territory-run or Aboriginal community–controlled healthcare services, with few being church and charitable organisations. The major historical influences on Indigenous health services included the prevailing attitudes of the dominant colonial culture towards Indigenous people and the resultant policies of successive governments. As the negative impact of colonisation on Indigenous peoples continued in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was thought by many in Australia that Indigenous peoples were dying out. The first major political actions towards Indigenous peoples were those of ‘smoothing the dying pillow’, and a period of protection and segregation was introduced. Healthcare services were mainly run by Christian or charity organisations with some government involvement. Indigenous people were removed to missions or reserves, with varying healthcare services provided. In some cases these were non-existent.19 The healthcare policies at the time were designed more to protect the wider Australian community from infection than to promote the health of Indigenous people. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that there were any consistently meaningful strategies to address the health status of Indigenous people.

Community-controlled health services were established in the early 1970s in response to Indigenous people’s struggle to access healthcare services and to address high mortality and dissatisfaction with existing services. The major philosophies underpinning these services were self-determination and Primary Health Care. The Alma-Ata declaration on Primary Health Care has provided a foundation that has been very useful in developing healthcare services for remote Indigenous communities. However, it must be noted that many of these services had a strong commitment to self-determination that pre-dated the signing of the declaration.

Community-controlled health services have had an impact far beyond their own organisations. They have played an advocacy role in relation to Indigenous issues, attempting to ensure that Indigenous conditions and concerns were noted and addressed by appropriate bodies, particularly in the area of health. This has impacted on other healthcare services, such as those provided by state and federal governments.

Service agreements or grant-in-aid health services are services that are managed by the local town or community but are funded by the state. These services are usually administered by the community council or an organisation within the community. Agreements between the state or territory health department and the council/organisation define the budget and the level of service. There is some debate as to how much control communities actually do have under these agreements, particularly when they are inadequately funded.

A more recent model of health financing has been the Coordinated Care Trials and the development of Primary Health Care Access Programs. These programs have provided additional funding by pooling monies traditionally only available to urban and regional areas where medical practitioners resided, and include the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Medicare. With the proposal that the Commonwealth assume 100% responsibility of PHC funding and policy, funding arrangements for these services should become more streamlined into the future.

Indigenous health in New Zealand

Similarly, in New Zealand, Māori were also adversely affected by the impact of colonisation; however, the Treaty of Waitangi, signed between the Crown and the Indigenous people of New Zealand in 1840, appears to have had a mediating influence. The Treaty takes the requirement of equality and non-discrimination for Indigenous peoples to a more self-empowered position of partnership and racial equity for Māori.20 The New Zealand Māori population fell to an all-time low in 1908 but recovered following initiatives to promote Māori health outcomes.21 One example of this was the introduction by Māori of the Māori Health Nursing Scheme, which was eventually replaced by the Native Health Nursing Scheme in 1911 and then absorbed by the District Health Nursing Service in 1930.22 Today, the inequity of health outcomes between Māori and non-Māori is slowly lessening. The Treaty of Waitangi continues to influence this trend. The Treaty began to feature strongly in the healthcare system in 1985 and began to be recognised in all legislation relating to health.21 The outcome of the increasing focus on the Treaty was a move towards self-determination for Māori and a separate funding stream for Māori health providers.21 These providers, in combination with mainstream providers, work in rural areas to meet the needs of local populations.

Higher proportions of Indigenous peoples live in rural and remote areas in both Australia and New Zealand; this clearly impacts on the type of healthcare and other services that are provided in these areas. The poor health of Indigenous peoples in both Australia and New Zealand is well documented.1,23–25 Nurses who work with Indigenous populations should be aware of factors that influence the health and wellbeing of these groups, including historical, environmental, social and cultural factors.

The Māori scholar Te Ahukaramu Charles Royal offers a useful way to understand the worldview of Indigenous peoples when he writes:

… in the Judeo-Christian tradition, God tends to be located outside of the world in a place called ‘heaven’. Hence, this world, the one we inhabit, was ‘created’ by God … In the Eastern worldview, on the other hand, great emphasis is placed upon the inward path, the finding of the divine within. Hence, the proliferation of meditative practices in the east, the disciplines of the ashram and so on. The indigenous worldview sees God in the world, particularly in the natural world of the forest, the desert, the sea and so on. Human identity is explainable by reference to the natural phenomena of the world … Hence, indigenous worldviews give rise to a unique set of values and behaviours which seek to foster this sense of oneness and unity with the world.26

Health definitions and determinants

THE ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER DEFINITION OF HEALTH

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are diverse and hold a range of beliefs and opinions, and the peak organisations representing their health interests that came together for the signing of the ‘Close the Gap’ statement have used the definition of health developed during the development of the National Aboriginal Health Strategy in 1989. This definition not only relates to physical health but also encompasses a holistic approach, including the social, emotional, spiritual and cultural wellbeing of the individual, together with community capacity and governance.27 Thus, healthcare programs must address all of these issues if they are to provide a service that is appropriate to Indigenous Australian peoples. Comprehensive Primary Health Care has been identified as the most appropriate model of care for Indigenous Australians.27 Primary Health Care includes (culturally) appropriate accessible healthcare with community participation in the planning, organisation, operation and control of the healthcare service.28

THE MĀORI DEFINITION OF HEALTH

The Māori definition of health also encompasses a holistic approach. One of the most common models used to represent this is that of Te Whare Tapu Whā, which is a concept of health that encompasses spiritual health, psychological health, physical health and family health. This approach uses a symbolic representation of the whare, or house, to explain the four cornerstones of Māori health. If one side of the whare is weak, the others will fall. The four sides refer to Taha Wairua (spirit), Taha Hinengaro (thought and feelings), Taha Tinana (body) and Taha Whānau (family/community).21

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF INDIGENOUS HEALTH

There is strong evidence that a person’s social and economic circumstances will strongly affect their health, with those from lower socioeconomic groups experiencing higher rates of serious illness and premature death.29 Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have significantly lower incomes, home ownership and employment rates than non-Indigenous Australians, and have national imprisonment rates 15 times higher than non-Indigenous imprisonment rates (24% of the total prisoner population).30 Indigenous levels of education are much lower than those of the non-Indigenous population, with the Northern Territory having the lowest number of Aboriginal students reaching the Year 7 reading benchmark (62% in provincial schools, 45% in remote schools and 15% in very remote areas compared to non-Indigenous rates of 89%).31

In New Zealand, Māori are also overrepresented in lower socioeconomic groups, with higher levels of unemployment, poverty and lack of education qualifications.32 It is also known that social and psychological circumstances that cause stress, and a lack of control over one’s circumstances in life, are detrimental to health.29,33 In fact, it has been argued that unfavourable social conditions and ineffective self-management are greater determinants of health in disadvantaged populations than is a lack of access to medical care.34 These concepts are not new to the Indigenous peoples of Australia and New Zealand, who have always seen health in a broader context than that which is solely related to disease, as is reflected in their definitions of health.

CULTURAL SAFETY

Inadequate understanding of and respect for the Indigenous (or any alternative) worldview and cultural knowledge base, together with communication difficulties, are suggested to be central features of the inability of service providers to offer effective cross-cultural communication and healthcare services.19,27 This miscommunication has at times been due to racism, but can also be due to a ‘complex mix of genuine goodwill and gross misunderstanding’.35

The 2006 Australian Census reported that 12% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples spoke languages other than English when at home and the proportion increased with remoteness to a total of 56% in the very remote regions.36 Bilingual education is highly valued in Indigenous communities, not only because it helps children maintain Indigenous languages, but also because it helps preserve Indigenous languages and supports the role of Indigenous teachers. In 2008 the Northern Territory was widely criticised for closing the bilingual education program across the Territory’s schools.37

Cultural safety is a phrase originally coined by Māori nurses; it means that there should be no assault on a person’s identity. Irihapeti Ramsden, who spearheaded the original cultural safety movement in New Zealand, believed that it is not enough to focus on the ‘exotic’ aspects of an individual’s or group’s culture.38 Cultural safety involves recognition of power balances and historical, political, social and economic structures. Culturally safe practice requires, first and foremost, a respect for the differences that exist between people, individually and collectively. It is an important challenge for healthcare professionals in the remote context to provide professional care and services that respect the safety of both the individual client and the community to which they provide those services. Cultural safety is discussed in Chapter 2.

Cultural safety in Primary Health Care

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Background

Raiha is a 68-year-old Māori woman who has type 2 diabetes mellitus and congestive heart failure. She lives alone in a remote rural area in a small ‘bach’ on her own land. Raiha loves her humble home but has struggled without running water and has an outside toilet. As she has no transport, Raiha is especially pleased that a Māori health provider (MHP) service is available in the nearby town because it offers home visits and nurse-led and doctor’s health clinics in her area. Raiha is collected weekly by a community health worker, where she joins other Māori elders at the MHP whare (building) for Māori art and crafts, singing, prayer, talk and laughter. Health services are also available at the site during this time.

Meeting client needs

One weekend Raiha developed a cold and severe productive cough. Without transport, she waited for Monday to contact the MHP. By then she had developed a fever, had not eaten or taken much fluids and was short of breath. The MHP well-family nurse was concerned about her shortness of breath, raised blood sugar level, fever and deteriorating malaise. She was transported to hospital and admitted for treatment and eventually returned home. While in recovery at home Raiha was visited by the MHP mobile nursing team twice weekly. In addition to addressing her medical and environmental needs, prayer and songs from the nurse and community health worker were part of her care during this time. She shared that this was uplifting and healing for her spiritual, emotional and physical being. Her family arrived from the city and provided the dimension of whanaungatanga (extended family connectedness). As she became stronger she was able to join her friends in a wheelchair at the MHP whare for fellowship. Her prognosis was not great but her quality of life was maximised by the ‘cultural embrace’ she received.

Cultural safety in this Primary Health Care setting is essential for this Māori woman to interact in New Zealand society. She described her experience to be about life choices rather than lifestyles. MHP staff provide a service to her that maintains her mana (status/power), which therefore assists in the healing process. Raiha proudly shared with her peers what it meant to be able to access a health service that acknowledged and provided her Māori cultural needs as defined by her, as well as her physical health needs.

The Treaty of Waitangi, the Nursing Council of New Zealand and the New Zealand government, through the principles of ‘protection, participation and partnership’, direct MHPs to ensure that culturally safe practice is delivered to all people who access their services. Raiha’s experience is from a Māori perspective.

(Special thanks to Lou Te Hinepouri Jurlina for this case study)

The concept of culture has different connotations in New Zealand because of the Treaty of Waitangi and the emphasis on biculturalism rather than transculturalism.39 This is a key influence on the practice of rural nurses when working with Māori. The Nursing Council of New Zealand provides guidelines for this practice.39

Primary Health Care approach

Primary Health Care has been the foundation of remote area nursing, and remote area nurses have been the leaders in implementing its principles.40 Primary Health Care is an approach or philosophy that permeates the whole healthcare system. It is a way of doing healthcare—not so much in what is done, but rather how it is done. Box 11-1 outlines the ‘how’ principles of Primary Health Care.

BOX 11-1 Principles of Primary Health Care

Source: ANF, AARN & CRANA. Action on nursing in rural and remote areas, 2002–2003. Recommendations and action plan. Canberra: National Rural Health Alliance; 2002.

The national strategic framework of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce addresses actions and specific strategies that are aimed to produce a competent health workforce servicing the needs of this population.41 The overarching principles are similar to those of Primary Health Care and include:

Characteristics of remote area and rural nursing

Remote area and rural nursing in Australia and New Zealand are stimulating and challenging and can be characterised by features not experienced in other nursing contexts. Box 11-2 outlines these important characteristics.

BOX 11-2 Characteristics of remote area and rural nursing

• Providing care to small, dispersed and highly mobile populations

• Providing care to populations with high morbidity and mortality

• Working in the context of a lack of social and human services infrastructure

• Working in isolation, which is geographical, social, professional and cultural

• Absence of remote health standards, credentialling or remote service accreditation

• A strongly multidisciplinary approach with flexible professional boundaries, often with a horizontal style of management

• Advanced and collaborative practice

• Lack of boundaries between home and work

• Dependence on remote technologies

• High levels of traumatic events

• Frequently lacking formal preparation for the advanced and extended practice role

PROVIDING CARE TO SMALL, DISPERSED AND HIGHLY MOBILE POPULATIONS

Australia is a large continent with the vast majority of the population choosing to live along the fertile coastal eastern edge. The further inland one travels, the more dispersed the population. Some remote communities service even smaller ‘outstations’ that may consist of one or two family groups with no shop, school or healthcare service and only one pay telephone for communication. Most rural and remote populations also have very poor access to public transport, limiting their access to healthcare and other services. Compounding this issue is the high cost of fuel and transport in rural and remote areas. This increased cost of fuel often means that trips to healthcare professionals are delayed.

New Zealand does not have the large land mass found in Australia, although in some areas it does have the climate extremes; however, large distances, geographical barriers (see Fig 11-2), lack of public transport or reliable private transport and severe weather conditions negatively influence access to services.6

CLIMATIC EXTREMES

Most of the remote areas of Australia are in the north, in the desert areas of the country or the numerous islands that surround Australia, with a smaller and less visible number in the southern states. The northern climate is often hot, with temperatures reaching 45–50°C. There is high humidity in the north (the ‘Top End’), and it is often dry and dusty in the desert regions. Accessibility is particularly limited across the Top End during the wet season (December to April), when rivers rise, making the roads impassable for several months of the year (see Fig 11-3). These factors impact on the ability of nurses to offer services, as well as the ability of healthcare services to attract staff.

Figure 11-3 River crossings become necessary in the wet season in northern Australia.

Used with permission. Bev Mackay.

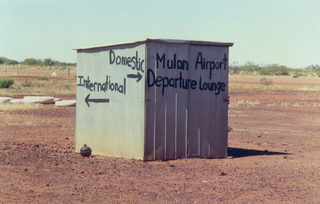

During these months the small airstrips, which are usable only in daylight hours, may also be too wet to use and people may move closer to services, usually relying on family members to accommodate them. This can result in up to 30 people living in a three-bedroom house for several months every year. A combination of aeroplane, car and boat may be needed to provide outreach medical care to outstations or remote farming properties. Evacuation services such as the RFDS must also negotiate these conditions, with some airstrips being non-serviceable for days or weeks at a time (see Fig 11-4).

Figure 11-4 An airport used by remote area nurses in the Kimberley region of the Northern Territory.

Used with permission. Bev Mackay.

Southern Australian and New Zealand communities experience extremes of cold and often are isolated by snow or ice. Remote communities in the south are less visible and have less organised services than northern Australia. For example, some states do not have organised telephone consultation services or outreach specialist and allied health services. This is challenging for nurses working here. Poverty and changing economies have also magnified the isolation of some small populations.

HIGH POPULATION MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

People living in rural and remote areas have higher rates of morbidity and mortality than those living in major cities. They are more likely to: be smokers; drink alcohol in hazardous quantities; be overweight or obese; be physically inactive; have lower levels of education; and have poorer access to work, particularly skilled work. Many rural occupations are also more physically risky. In addition, they have less access to specialist medical services and a range of other healthcare services.42 Reduced access to services, lack of control over aspects of one’s life, reduced transport options, a shortage of healthcare providers and greater exposure to injury and accidents are all contributors to the health divide.1,29,42

LACK OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SERVICES INFRASTRUCTURE

As remoteness increases, the supply of healthcare service providers, in particular medical specialists, decreases, with remote areas having less than half the ratio of general practitioners than that in major cities.43 In both Australia and New Zealand there are concerns about the rural workforce. Retention and heavy workloads are key issues.43 The workforce is supported by Indigenous (Māori and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander) healthcare workers and demand for these workers is high and continues to grow. There are also increasing opportunities for rural nurses to expand their scope of practice to meet opportunities arising as a result of the heavy workload and shortage of medical practitioners.44 Remote area nurses have traditionally been supported to undertake an expanded scope of practice due to the lack of resident medical practitioners.

GEOGRAPHICAL, SOCIAL, PROFESSIONAL AND CULTURAL ISOLATION

The large distances that characterise remote Australia result in a lack of access to many services and resources. Information technology is also often absent or poorly supported and this has been identified as a priority for improving recruitment and retention of healthcare practitioners.44 Professional isolation is commonly cited as a barrier to recruitment and retention of health practitioners. For new graduates or those new to the discipline of remote area or rural health, it may be difficult to access the ongoing supervision and mentoring that is necessary for advanced practice development and adjustment to a new role. Remote area nurses are often members of a small team or are sole practitioners without immediate access to colleagues with whom to consult or discuss clinical, professional and other issues. This can increase the stress associated with many clinical, professional and social situations.

Some remote area and rural practitioners may feel isolated within their own professional groups. Remote area and rural nurses are minority groups within the wider nursing profession. Urban practitioners have different professional demands, agendas and issues of concern. A sense of professional isolation can be reduced by joining and participating in professional bodies that contain other remote area practitioners, networking with other rural or remote area nurses, subscribing to professional journals and email groups, and undertaking professional development and remote practice education. In New Zealand, the New Zealand Rural General Practice Network provides support for rural nurses. In Australia, CRANAplus is the professional association for remote and rural health practitioners, and the Faculty of Rural and Remote Nursing of the Royal College of Nursing Australia provides professional support to rural and remote area nurses in Australia.

Remote area nurses are often recruited from metropolitan or regional areas, so whether they are working in an Indigenous community, mining, fishing or pastoral town, they usually experience cultural isolation as a result of living in a community whose values and belief systems are different, however subtle.

A major difference between rural and remote area nursing is that rural nurses are often linked to the rural town. For example, many rural nurses may work part-time as they are also, say, business partners in the family agricultural enterprise. Thus, rural nurses are more likely to have been employed within the healthcare service for a longer period of time, and are more likely to work part-time than remote area nurses.45 A national survey on rural nurses in New Zealand found that they had established roots in their communities too and that almost 50% worked part-time.46

Additionally, rural nurses tend to form network groups (e.g. an oncology nurses network group) to share their experiences of providing care outside a major capital city. However, data from a recent study of nurses in Australia suggests that remote area nurses are more likely to have access to and use information technology than rural nurses.47 Importantly, the technical support for both software and hardware packages is less likely to be available to rural and remote area nurses than nurses employed in major cities.

LACK OF BOUNDARIES BETWEEN HOME AND WORK

In urban and regional areas, there are distinct boundaries between work and home, friends, family and clients. These boundaries are blurred in remote and small rural areas. Remote area nurses are required to provide a 24-hour service, so they are on-call routinely and, like some rural nurses, may socialise with or be related to community members they also have a professional relationship with. This can result in gaining a deeper understanding of the client’s social and emotional wellbeing and a more effective professional relationship. However, it may also cause challenges for the nurse or the clients, who may struggle with the different expectations of the small community, as well as privacy issues.48

FREQUENTLY ON CALL

The smaller the team of remote area or rural nursing staff, the higher the requirements for nurses to participate in on-call commitments. Most remote healthcare centres and small rural facilities provide a 24-hour service. Single or dual nurse posts often provide continual on-call services, 7 days a week, as either the primary person on call or the secondary back-up staff member. They then have to provide the routine services the next day. In remote areas, this can result in reduced staff availability during usual opening hours or nurses working without sufficient breaks between being called out and usual business. It is critical that nurses receive adequate rest to rejuvenate from the demanding schedule of disrupted sleep and high-pressure events. In rural areas, there are usually sufficient staff to allow nurses who have worked on call to have an appropriate break. However, in times of workforce shortages where there are insufficient staff, many rural nurses are also required to work without adequate breaks between shifts.

HIGH LEVELS OF TRAUMATIC EVENTS

The high levels of morbidity commonly found in some rural and many remote areas can expose the remote area nurse to significant illness and trauma not witnessed by other nurses working outside the emergency or intensive care setting. High rates of violence and family abuse require nurses to be highly competent at managing multiple traumas, diagnosing fractures without the assistance of radiology equipment, stabilising shock, and suturing and dressing complicated wounds. Self-harm is also seen at higher rates in many Indigenous communities. These presentations are often confronting and personally difficult for the nurse to deal with and may have a considerable impact on the nurse’s own wellbeing.44

AUTONOMY AND FLEXIBILITY

A positive aspect of rural and remote area nursing is the level of autonomy and flexibility. Remote area nurses and nurses employed in small rural health facilities are highly autonomous practitioners who work within the flexible service arrangements that range from acute and chronic medical services to Primary Health Care activities and community development exercises. A typical day for a remote area nurse may involve seeing numerous sick children, undertaking growth assessments and immunisation on well children, delivering chronic disease care and visiting older residents in their home to administer medication and consult with family, consulting with colleagues and managing acute presentations to the clinic. This variety in the work and the context of the remote environment ensures that nurses are extremely flexible and able to draw on a broad range of skills and knowledge in the provision of services. This work in rural nursing has often been called ‘womb to tomb care’.48

CROSS-CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT

Most healthcare workers in remote areas, and many nurses in rural areas, live and work in cross-cultural situations. Approximately three-quarters of the remote area workforce are employed in Indigenous communities, where the predominant culture may be very different from that of the healthcare professional. The remaining quarter work in small remote towns, mining camps or towns and tourist resorts, which are also different cultural environments. In rural areas in Australia it is not unusual for nurses to work in towns with cultures other than the predominant Anglo-Saxon Australian culture. For example, in Queensland, the city of Toowoomba has a large Sudanese population and Stanthorpe has a large Italian population. Additionally, increasing numbers of migrants and refugees are being settled in rural and remote areas and these newly migrating groups can bring new cultures to rural communities.49 Consequently, migrant and refugee heath issues can be challenging for rural nurses, who usually work with more than one cultural group.

Advanced practice

A common denominator across the healthcare professions in the discipline of remote area and rural health is the experience of working at an advanced level (see Fig 11-5) compared to urban counterparts and the collaborative nature of this practice. As noted previously, the need for remote area and rural nurses to work at an advanced practice level increases as the size of the healthcare service decreases. Many remote communities are serviced by one or two practitioners who rely heavily on the extended ‘team’ to provide continuous comprehensive care in the remote context.

Because of the breadth of the role, the professional agility required to work across the life span in urgent, emergency, chronic and preventative care, and the lack of immediate access to other healthcare professionals in rural and remote areas, all remote area nurses and many rural nurses work in an advanced and extended practice role. This role can be challenging, as undergraduate nursing education and experience do not adequately prepare nurses for practice in remote and rural areas.5,17 As part of their routine practice, remote area nurses and nurses employed in small rural healthcare facilities diagnose, prescribe, treat, monitor and follow-up within a best practice framework of standard treatment guidelines (see Box 11-3 and the Clinical practice box). Remote area healthcare centres and small rural healthcare facilities carry a standardised wide range of pharmaceutical products necessary to cater for medical conditions across the life span, as well as emergency and retrieval equipment to respond to and stabilise trauma and medical emergencies. Australian guidelines, such as the Central Australian Rural Practitioners’ (CARPA) Standard Treatment Manual50 and the Primary Clinical Care Manual,51 have been developed in response to a population health approach need and are utilised by all remote area healthcare professionals, not just nurses. Similar New Zealand Rural Health Care Standard Treatment Guidelines have also been developed in collaboration with CARPA, forging new relationships across the Tasman.52

BOX 11-3 Examples of remote area nursing activities

• Assessment, diagnosis and treatment of acute conditions

• Early detection and co-management of chronic disease

• Child health, and growth and development monitoring of 0–5-year-olds

• Health promotion activities, such as school, adolescent health screening, well women’s and well men’s adult health checks

• Public health activities (such as immunisation programs, outbreak control and sexually transmitted infection control), environmental health, food security surveys and nutrition programs

A child with otitis media in a rural hospital

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Patient profile

Lara is a 5-year-old Caucasian girl who presented with her mother, Rachael, at 7.15 pm. Rachael explained that Lara had come home from preschool that afternoon complaining of an earache and headache. Lara had gone to bed to rest and when Rachael awoke her at 6 pm for her evening meal, Lara was hot to touch and crying from pain in her ear. Her mother gave her paracetamol and a tepid bath prior to presenting her to the hospital. Lara said it was her right ear that hurt, and when asked where her head hurt she gave a generalised gesture that indicated her whole head.

Lara appeared unwell and, given the presenting complaints of fever and pain in her right ear, the nurse’s immediate impression prior to examination was that she may have otitis media, or possibly otitis externa or even mastoiditis. Given Lara’s complaint of headache and Rachael’s account of Lara being sleepy for the past few hours, meningitis was also considered.

It was important for the nurse to establish rapport with both Lara and her mother. The nurse asked Lara about herself in a non-threatening way of interacting (while not focusing directly on her being unwell) and to gather some relevant history and some basic assessment of her neurological and respiratory status. Information gathered from Lara and her mother included: the nature of the presenting problem; the onset and duration of this; Lara’s past medical history; and, with regard to this illness, her behaviour and activity, appetite and fluid intake and output, and medications given; as well as her family and social history, any current medications, allergies and immunisations.

Subjective data

• Lara was flushed (cheeks), was sitting quietly by her mother holding her ear and not irritable but more sleepy than normal

• Alert and easily roused from sleep

• Able to place her chin to her chest with no pain/stiffness to her neck and no increase in headache

• Weight: 17 kg; height 114 cm

Objective data

Physical examination

• Per axilla temperature: 38.4°C

• Pulse: 101 beats/min with regular rhythm

• 99% oxygen saturation on room air

No evidence of cellulitis bilaterally to the pinna or surrounding tissue. No pain, swelling or tenderness noted over the mastoid area of either ear. No complaints of dizziness or ringing in the right ear. Complained of not being able to hear ‘very well’ in the right ear. The left ear was normal. The right ear showed a red and bulging intact tympanic membrane with fluid noted behind the eardrum. There was thick green discharge from the nose; primarily breathing through the mouth. The throat was slightly red and painful, and green post-nasal drip was noted. All other system examination was normal.

Diagnosis and treatment

A diagnosis of acute otitis media was made. Treatment was initiated that involved: reduction of temperature and pain (paracetamol and tepid sponge). Her temperature reduced to 37.7°C within 1 hour. Lara was commenced on amoxycillin 7 mL three times per day as she was not allergic to penicillin. This dose was calculated as Lara’s weight of 17 kg with a child dose of 10 mg/kg three times a day (rounded to the nearest measurable quantity) with a duration of 7 days. This equals 17 kg × 10 mg/kg = 170 mg per dose. The strength required was 170 mg divided by the strength in stock (125 mg) multiplied by the volume of 5 mL = 6.8 mL (or 7 mL) three times a day. This was given as a suspension as the dose was less than that available in capsules.

The paracetamol dose was calculated by Lara’s weight of 17 kg × 15 mg/kg = 255 mg. The strength required was 255 mg divided by the strength in stock (120 mg) multiplied by the volume of 5 mL = 10.6 mL, which was rounded to 10 mL. The dose is up to a maximum of 60 mg/kg per day.

Rachael was also advised to increase oral fluids to Lara. Lara was encouraged to blow her nose, and the application of a warm pack on the ear for additional analgesic relief was suggested to her mother. Rachael was advised to look for ear discharge, an increase in the severity of the headache (associated with rashes) and any increase in drowsiness, particularly if Lara was hard to rouse from sleep.

As the nurse was endorsed for Queensland rural and isolated practice (RIN), there was no need for a medical order for the antibiotics. The nurse was able to administer and supply a full course of amoxycillin under the Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996 as the drug was listed on the Drug Therapy Protocol for use in otitis media. Similarly in Queensland, under the Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996, Registered Nurses in rural areas are allowed to administer and supply paracetamol without a medical order. There is no requirement for the doctor to write a prescription or to see the child. However, the doctor (at his request) reviewed Lara 2 days later. The ear settled without any complications.

(Thanks to Anne Ryan for allowing adaptation of her case study)

Collaborative practice

Despite the paucity of resident medical and allied healthcare workers in many remote and rural areas, remote area and rural nurses work in close collaboration within multidisciplinary teams. Historically, remote area nurses have developed their practice in response to local needs and the resources available, including the lack of resident doctors and allied healthcare professionals. They have been early adapters to remote technologies, such as high-frequency radio, telephone, fax and now email, to coordinate and facilitate care. This does not mean that remote area nurses see themselves as ‘mini’ doctors or specialists, but rather as ‘maxi’ nurses who specialise in bridging services, using remote technologies to provide, lead and coordinate care collaboratively. These flexible professional boundaries occur in close association between remote area nurses, doctors, Indigenous and allied healthcare workers within an environment of serious respect for ability and experience. These strong collaborative and respectful relationships lead to better care and significantly less tension between team members. In small rural hospitals, the role is similar. As the healthcare service grows, the level of collaborative practice will vary and becomes dependent on the personal characteristics of the nurse and medical practitioner.

In remote areas, while on-site staff usually consist of remote area nurses and Indigenous health workers and some doctors, the extended team includes visiting doctors, community welfare workers and allied, pharmacy, dental and other professional groups, as well as administrative, management and environmental health staff. Team members need to have their own specific areas of expertise, as well as advanced generalist skills and the capacity to support and complement each another and utilise a range of technologies effectively. Teamwork includes working across services, borders and professions.

Arguably the most important member of the health team for the remote area and rural nurse in a cross-cultural setting is the Indigenous health worker. In Australia, this includes the Aboriginal health worker and the Torres Strait Islander health worker, and in New Zealand it is the Māori community health worker. The relationship between the nurse and the Indigenous health worker is crucial to the effectiveness of the service within the community. Not only do these health workers share some of the clinical workload, they also offer an invaluable role in health programs and in educating nurses to the specific needs of the community. One of the most important roles of the Indigenous health worker is to act as the cultural broker and interpreter. However, these tasks add to an otherwise full workload and can be very frustrating and tiring for Indigenous health workers due to the high turnover of nursing staff.

In New Zealand, Māori community health workers are important members of rural health teams regardless of whether they work for Māori healthcare providers or for mainstream Primary Health Care services. In Māori organisations, Māori health workers, or kaiawhina, are employed to support Māori philosophies (kaupapa) and customs and traditions (tikanga).6 Kaupapa Māori is a philosophical framework that promotes Māori culture, knowledge and values, thus fostering empowerment, self-determination and justice for Māori. It underpins the concept of ‘by Māori, for Māori’,53 or tino rangatiratanga (self-determination for Māori),54 and promotes accessibility and acceptability of services for Māori.

Unlike the vertical, discipline-specific structures more commonly found in urban services, where there is a hierarchical line of authority descending from the person in charge to the most junior team member, nurses in rural and remote health teams generally have a more horizontal structure, with most or all of the team members at a similar level of responsibility and authority.55 A participatory management approach and a more horizontal structure facilitate community participation.56

Professional support for rural and remote area nurses

In Australia, CRANAplus is the professional organisation representing health professionals of all disciplines who work in rural and remote areas, and the Rural Nursing and Midwifery Faculty of the Royal College of Nursing Australia provides professional support for rural nurses. Additionally, the National Rural Health Alliance is the peak multidisciplinary body for rural and remote health, and the Bush Support Services provide psychological support for rural and remote health practitioners (see the Health promotion box). In New Zealand, the Rural General Practice Network supports rural health professionals. The websites for these organisations are listed in the Resources (see p 222).

Remote area nurse model of consultation

A large proportion of the everyday work of a remote area nurse involves consultations with clients. This has traditionally been a skill of general practitioners and has not been something nurses have been formally taught. However, it is a vital skill for remote area nurses. People presenting for consultations often have significant co-morbidities and age- or place-related risks for other life course conditions. It is critical that remote area nurses have the skills to manage these consultations effectively from both the client’s and the practitioner’s perspective. A model of consultation was developed by Knight and Lenthall involving the following steps to guide remote area nurses:

• open the consultation, establish a connection and rapport, and check appropriate past history

• take a history of the presenting complaint and discuss ongoing health problems, social/environmental factors, general wellbeing and risk behaviours

• undertake a comprehensive clinical examination and investigations

• discuss the findings and health promotion

• negotiate the management plan, including seeking further advice or referral and further investigation

• close the consultation, covering contingencies.56

HEALTH PROMOTION

The CRANAplus Bush Support Services is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing and is run by a team of psychologists with rural and remote experience. This award-winning service aims to contribute to the retention and wellbeing of multidisciplinary healthcare practitioners by supporting them and their families to successfully manage the stress associated with remote area and rural practice.

• toll-free 24-hour support line (phone 1800 805 391)

• stress inoculation and other workshops

• publications, including self-care booklets

• informational products to increase awareness of Bush Support Services

• best-practice guidelines to support practitioners following job-related trauma.

Further information is available at http://bss.crana.org.au/, accessed 13 February 2011.

BE RESPONSIVE AND COMPREHENSIVE

The consultation should be both responsive and comprehensive. It is important to deal with the client’s issue at the same time as considering ongoing health problems, comorbidities and the potential interaction between them. The comprehensive history of the presenting complaint, together with relevant past history, social and environmental factors and general wellbeing, form the basis of this. Most clients are known to the service, if not to the remote area nurse, so a review of the client’s record will provide most of the background information. Remote area nurses need to undertake both a comprehensive history and an examination; they should be guided by the clinical rule of age/place risk and always examine the systems above and below those of the presenting complaint.

MINIMISE RISK

Early onset of chronic disease, aggressive infections and high levels of morbidity and mortality must be taken seriously. The adage of the remote area nurse of ‘What can’t I afford to miss?’ underpins clinical decision making and requires high-level public health knowledge of the population and region. Discussing the findings of the consultation with the client allows clarification of issues and opportunity for health promotion or brief intervention. Remote area nurses must be mindful of their own individual professional limits and refer to or seek advice from colleagues and medical officers appropriately. Respectful collegial relationships and reliable and effective communication are essential for this.

BUILD CONFIDENCE AND SELF-RELIANCE

The quality of the interaction between the nurse and the client will determine the client’s confidence, trust and willingness to continue with the partnership of care. An effective strategy for this is the negotiation of the management plan. This allows the nurse and the client to explore the options for care, the pharmacological and supportive therapy options, the limitations and the logistical challenges. This process contributes to improvement in compliance, the therapeutic relationship and overall health literacy. Each encounter aims to build the client’s understanding of the illness and their confidence to make and articulate decisions about their care. With chronic disease the client becomes the expert and the remote area nurse the facilitator of new or emerging information and coordination of care.

Rewards of working in rural and remote area nursing

Most nurses who work in remote or rural areas do so because they enjoy it and have an interest in the provision of good healthcare. Not only do they live and work in some of the wildest and most spectacular parts of the country, but they also enjoy being a member of a small team and community. Daily travel time to work is usually minutes away, although many rural nurses live on working farms and commute considerable distances or live in towns and commute between them. Although there are many challenges to some aspects of the work, it is also very satisfying to have relationships develop that extend beyond the short-term contact that most urban-based hospital nurses have. Developing relationships with community members facilitates more effective care, as nurses follow individuals and families through months or years of their lifetime.

Working closely with Indigenous people is an honour and a privilege that most nurses working in remote or rural areas recognise. These communities must tolerate many new people working in their healthcare services and often it is the first cultural experience for these nurses. Indigenous healthcare workers and community residents usually patiently tolerate any cultural faux pas and gently educate and inform the visitors of their ways.

Education pathways for remote and rural nurses

In New Zealand, graduate nurse entry to practice expansion programs and postgraduate education is available to support nurses to move into rural nursing and towards advanced roles, including the nurse practitioner role. Postgraduate education and clinical career pathways are supported through Nursing Professional Development and Recognition Programmes.

In Australia, a number of undergraduate and postgraduate programs are available to prepare nurses for rural and remote area practice. Many universities now provide their undergraduate student nurses with a rural or remote area nursing placement to ensure that they have an opportunity to experience this type of practice during their pre-registration undergraduate program. Transition from Registered Nurse to remote area nurse can be undertaken within an employed model education pathway. CRANAplus has developed a suite of postgraduate programs with the Centre for Remote Health designed to provide preparatory and ongoing education for the discipline of remote practice. Many health services support and use this model. CRANAplus also provides targeted short courses such as Remote Emergency Care (REC) and Maternal Emergency Care (MEC) to support upskilling of the remote workforce in these emergency areas. Several states have accreditation requirements, such as Queensland remote area nurses must have completed the Remote and Isolated Practice Endorsed Nurse program (RIPEN) and in Western Australia remote area nurses are required to complete the Pharmacotherapeutics for Remote Area Nurses program. Nurse practitioner education is evolving for rural and remote area nurses across Australia, and national registration and accreditation of education programs are now in place.

Future of remote area and rural nursing

The rapidly developing health needs and the continuing undersupply of healthcare professionals to rural and remote area practice signify an important continuing and developing role for remote area and rural nurses in the delivery of healthcare. The challenges of remote area practice will require the profession to benchmark and credential remote area nurses, from the nurse new to remote area practice through to the experienced remote advanced practice nurse and nurse practitioner. Credentialling will provide the professional framework for the provision of safe, high-quality healthcare that remote area nurses aspire to and communities require.

In rural areas there has been some recognition of the need for a more advanced role. For example, in Queensland, the Rural and Isolated Practice Endorsement has meant that nurses who complete an approved program (through the regulatory authority) can administer and supply medications without a medical practitioner order. These nurses work from protocols (e.g. the Primary Clinical Care Manual) rather than taking on a direct advanced practice role. They differ from nurse practitioners as they are not authorised to prescribe (just administer and supply). This model is now being adopted (with some modifications) in other Australian states. In New Zealand, ‘standing orders’—namely, written instructions normally issued by a medical practitioner regarding administration of specific medicines under precise circumstances—have become widely recognised as normal practice in healthcare, including rural nursing practice. Amendments were made to the Medicines Act 1981 (NZ) to enable the legal use of standing orders, and guidelines are available to manage the process.57,58

A model recently developed is the rural or remote area nurse practitioner. The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia has set national registration standards for endorsement as a nurse practitioner, and in 2010 a Masters program specifically designed for remote area nurse practitioners, the Master of Remote Health (Nurse Practitioner), was accredited by the Northern Territory Health Professions Board. The nurse practitioner model will enable suitably prepared and experienced remote area and rural nurses to be authorised to practise as a nurse practitioner. These nurses play a vital role in complex care, development and utilisation of best practice and quality improvement through research and leadership in remote area and rural nursing into the future. However, it is likely that there will be several models of rural and remote area nursing in Australia: the beginning practitioner (without a postgraduate qualification); the endorsed advanced practice nurse; and the nurse practitioner. It is unlikely that all nurses in rural and remote areas would be nurse practitioners. In New Zealand, the nurse practitioner is a Registered Nurse who practises at an advanced level in a specific scope of practice, has a Master’s qualification and has been recognised and approved by the Nursing Council of New Zealand as a nurse practitioner.59 Further information on nurse practitioners is available on the New Zealand Ministry of Health website (see the Resources on p 222).

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Patient profile

Jacinta presents with her 7-month old son Tyler at 7 pm with a history of 4 days of diarrhoea. He has been breastfeeding regularly and has no history of vomiting or fever. He has had no other signs. His mother reports the diarrhoea as frequent and very watery with no blood or mucus. It is difficult for Jacinta to estimate his urine loss as his nappies are wet with the diarrhoea fluid. His development has been age appropriate and he has been following his own growth curve well. Immunisations are up to date. Past history includes a normal birth, one episode of pneumonia at 5 months and a recent episode of diarrhoea 3 weeks ago with weight loss. Jacinta had a normal pregnancy with one urinary tract infection recorded. There are no others in the house with diarrhoea and no environmental hazards, such as broken drains, in the yard.

Subjective and objective data

The remote area nurse observes that Tyler is lying lethargically in his mother’s arms grizzling. His respiratory rate is slightly raised, the work of breathing normal, with no in-drawing or nasal flaring. On examination his neck flexion, nose, eyes, throat and both ears are normal with drums intact and no nodes palpated; his chest is clear with no wheeze or crepitus, and heart sounds are normal. His abdomen is soft and his skin is clear. His genitals are carefully washed and dried and a paediatric urine bag is attached as described in the CRANAplus clinical procedures manual.

His temperature per axilla is 37°C, pulse is 152 beats/min and respiratory rate is 42 breaths/min. The haemoglobin level is 110 g/L. Tyler has poor skin turgor, a depressed fontanelle and sunken eyes. His weight is 7.760 kg. Two weeks ago when Jacinta presented Tyler for his 6-month immunisations his weight was recorded as 8.375 kg. The nurse calculates that Tyler is 7% dehydrated based on the formula located in the CRANAplus clinical procedures manual for remote and rural practice and notes that this concurs with her clinical examination:

Treatment and management

The nurse discusses this with Jacinta and shows her the table of signs of dehydration. They both agree that Tyler has many of the signs of moderate dehydration and will need rehydration with both breast milk and oral rehydration salts (ORS). The nurse makes up a container of ORS solution supplied in sachets and kept in the pharmacy. She checks the CARPA manual to calculate how much to give him hourly: 600 mL over 4 hours/14 mL every 5 minutes. She gives Jacinta a 20-mL syringe, marks off 14 and asks her to try to give Tyler small amounts of the fluid while she rings the doctor to discuss the case. She explains to Jacinta that the doctor might suggest going to hospital and asks if that would be okay. Jacinta says yes.

The nurse then contacts the remote medical practitioner (RMO) on call at the regional centre 380 km away. She relates the pertinent history, examination and assessment to the doctor. The RMO agrees that Tyler sounds about 7% dehydrated and asks the nurse if she thinks that Tyler should be evacuated to the hospital. The nurse agrees, as he has had a recent episode and is at higher risk because of this. They discuss that if Tyler is unable to take the ORS or starts vomiting, she will insert a nasogastric tube. The RMP informs the nurse that the aeromedical plane is currently on the ground in the next regional centre and will be dispatched to collect Tyler and Jacinta that afternoon, and to monitor Tyler in the clinic for any change.

The nurse returns to Jacinta and Tyler to find that Tyler is too unwell to accept the fluid orally. The nurse explains the conversation with the doctor to Jacinta and reconfirms the agreement to be transferred to the hospital. She inserts a nasogastric tube and shows Jacinta how to give 140 mL per hour of ORS for the next 4 hours and then, if the aeroplane is delayed, 77 mL/h based on the 10 mL/kg (10 × 7.760 = 77) documented in the procedures manual.

Jacinta sends for relatives, who bring her a small overnight bag. The aeroplane arrives after 4 hours, by which stage Tyler has had a further three bowel actions of yellow watery diarrhoea. He appears to be tolerating the ORS and his observations have improved to record a pulse of 126 beats/min and a respiratory rate of 28 breaths/min—signs of improvement. Tyler requires 4 days in hospital to correct his electrolyte imbalance and recover, and comes home on the bush bus.

In addition, in New Zealand, the Primary Health Care Strategy highlighted the need for the development and support of Primary Health Care nursing roles, including those in rural areas.60 The generic title ‘Primary Health Care nurse’ has been adopted, with an appropriate definition, to cover a wide variety of roles of nurses working in community settings.61 Workforce priorities include a focus on developing primary health care and rural nursing.62–64 Funding will be prioritised through Health Workforce New Zealand (HWNZ).

Another future way that remote area and rural nurses will link with their metropolitan (or distant) colleagues is by the use of videoconferencing, tele-health and other forms of information technology. For example, videoconferencing has been used extensively for rural and remote area nurses to link into meetings and for the provision of education and training programs. Similarly, there has been an increase in the use of information technology by rural and remote area nurses to document patient attendances, make referrals, check on pathology results and send radiography results to experts in larger centres. Tele-health, or tele-medicine, refers to the use of videoconferencing, or other forms of technology, to link distant clients to clinical specialists who are located in provincial or capital cities. The early use of this technology (called tele-psychiatry) linked clients requiring psychiatric consultations with specialists in metropolitan centres. As it continues to be more expensive to move specialists to distant clients and vice versa, tele-health will be used increasingly as a way to provide services to rural and remote communities.

The type of nursing practice experienced in remote and rural areas is on a continuum from large regional centres, with significant infrastructure and support, to small single or dual nursing posts in very remote areas. Regardless of where nurses work within this continuum, a nursing career ‘out bush’ is an exciting, challenging and rewarding career option.

1. In both Australia and New Zealand:

2. In Australia, people living in rural and remote areas:

3. Indigenous definitions of health:

4. Characteristics of rural and remote areas do not include:

5. The remote area nurse model of consultation does not include:

6. The rewards of nursing in a remote or rural area do not include:

1 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Rural, regional and remote health: a study on mortality (report profile). Rural Health Series no. 7. Canberra: AIHW; 2006. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publications/phe/rrrh-som-2/rrrh-som-2-profile.pdf accessed 13 February 2011.

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian social trends: using statistics to paint a picture of Australian society. ABS cat. no. 4102.0. Canberra: ABS, 2010.

3 Department of Communications Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA). Information technology training and information technology support: discussion paper. Canberra: DCITA, 2003.

4 Statistics New Zealand. New Zealand: an urban/rural profile. Available at www.stats.govt.nz. accessed 13 February 2011.

5 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Yearbook Australia. No. 89. Canberra: ABS, 2007.

6 Rural Expert Advisory Group. Implementing the Primary Health Care Strategy in rural New Zealand. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/1751?Open. accessed 13 February 2011.

7 National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Final report: a healthier future for all Australians. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009.

8 Knight S. Dancing in the dust. Conference proceedings. World Organisation of Family Doctors, Melbourne, 2002.

9 Department of Health and Aged Care. Measuring remoteness: accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA). Rev edn. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2001. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/7B1A5FA525DD0D39CA25748200048131/$File/ocpanew14.pdf Occasional Papers, New Series no. 14. accessed 13 February 2011.

10 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Rural, regional and remote health: a guide to remoteness classifications. Canberra: AIHW, 2004.

11 National Health Committee. Rural health: challenges of distance, opportunities for innovation. Available at www.nhc.health.govt.nz. accessed 13 February 2011.