Chapter 69 Chronic illness and complex care

1. Describe the major causes of chronic illnesses.

2. Explain the characteristics of a chronic illness across the life span.

3. Explore complex illnesses and the assessment of comorbidities in adults.

4. Describe self-management and self-care principles relating to chronic illness management.

5. Evaluate the models of care used to manage chronic and complex illnesses.

6. Identify the workforce requirements for health workers in meeting needs for chronic illness management.

Chronic illness

Chronic illnesses differ from acute illnesses because they are of long duration, tend to progress slowly and have a protracted, unpredictable course.1 The most prevalent chronic diseases internationally are heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes mellitus. Together, these five diseases are the leading causes of mortality in the world, representing 60% of all deaths. These diseases, along with depression, are also the most prevalent chronic illnesses in Australia and New Zealand.2,3

Multiple factors are involved in the development of chronic illnesses, such as heredity, lifestyle factors (in particular, societal changes relating to eating and exercise habits) and environmental factors. Although numerous chronic illnesses arise with ageing (discussed in Ch 5), half of those who die from chronic illnesses every year are under 70 years of age.1 Importantly, people with chronic illness tend to develop comorbid conditions, so that they not only have multiple chronic illnesses but also may accumulate more conditions as they age.2,4,5 Additional factors that have contributed to the rapid increase in the prevalence of chronic illnesses are the dramatic improvements that have been made in healthcare and health technology enabling people to survive previously fatal illnesses, meaning that more people are living with chronic illness and developing other chronic illnesses. Indigenous Australians, Māori and Pacific Islanders are strikingly overrepresented in all chronic illness data in Australia and New Zealand, suggesting the presence of multiple risk factors and highlighting potential issues with equity and access to healthcare and concerns about health literacy in Indigenous populations.2,3

This reinforces the need for prevention strategies to occur at both the individual and the population level. A recent 5-year study found that a limited number of cost-effective public health interventions can have a large impact on improving a population’s health status. These interventions include:

• taxing tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy foods

• placing mandatory limits on the amount of salt added during production of three basic food items (bread, cereals and margarine)

• improving the efficiency of blood pressure and cholesterol-lowering drug management by using an absolute risk approach and choosing the most cost-effective generic drugs (or potentially introducing a low-cost polypill that combines three blood-pressure-lowering drugs and one cholesterol-lowering drug in a single pill)

• using gastric banding for severe obesity

• undertaking an intensive campaign highlighting the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin.6

Regardless of the cause, chronic illness results in limitations in physical functioning, work productivity and quality of life for those affected and can profoundly affect the lives and identities of patients, carers and families. Chronic illnesses place substantial demands on the health system too;7 they currently comprise 70% of the current health burden and this is expected to increase to 89% by 2020.5 Financing the healthcare costs and developing the personnel needed for chronic illnesses have been identified as some of the top challenges facing the health systems in New Zealand and Australia.3,8

This chapter addresses generic issues in chronic illness for the individuals affected and for the nurses who care for them. Detailed discussion about specific chronic illnesses, including prevalence in Indigenous populations, is provided in various chapters throughout this book.

The complexity of chronic illness

Chronic illness is often associated with complexity in its causes, effects and consequences. There are three main factors that contribute to this complexity. First, chronic illness is characterised by periods of exacerbation; second, as time passes, a chronic illness and its treatments may generate further issues; and third, the individual with chronic illness may experience unequal access to care and support.

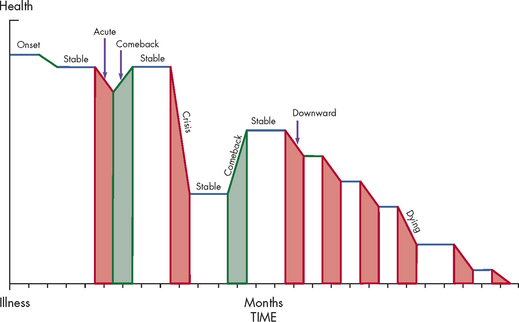

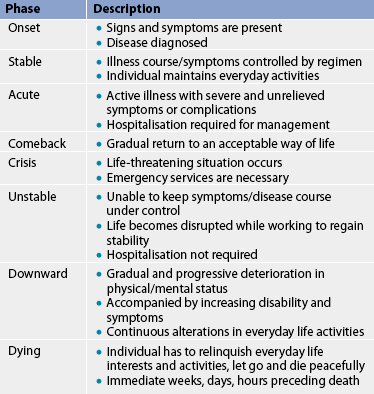

Chronic illnesses often have acute exacerbations in which the individual moves from a level of optimum functioning, with the illness in good control, to a period of instability where the individual may need assistance. Chronic illnesses can be described as following a trajectory (see Fig 69-1) with overlapping phases (see Table 69-1).9 This trajectory characterises the common course of most chronic illnesses. The increasing number of people with multiple chronic illnesses and the changes in levels of acuity in those with chronic disease have led to the need to develop local and regional systems to manage and integrate care for people with chronic illnesses.

Figure 69-1 The chronic illness trajectory is a theoretical model of chronic illness. The trajectory model of chronic illness recognises that chronic illness will have many phases (see Table 69-1).

TABLE 69-1 Chronic illness trajectory

Source: Woog P. The chronic illness trajectory framework: the Corbin and Strauss nursing model. New York: Springer; 1992.

Indigenous Australians and Māori both have poorer health outcomes across a range of chronic illnesses than their non-Indigenous counterparts. In addition, Indigenous Australian men have a life expectancy that is 11.5 years less than men in the general population,10 while Māori life expectancy for men and women is at least 8 years less than for their non-Māori counterparts.3 People from a culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background (i.e. people whose first language is not English) often have poorer rates of health literacy and may be excluded by their language and cultural preferences from attending chronic illness management and rehabilitation services.11

The Australian Institute of Health & Welfare has found that even though age-specific prevalence rates of disability appear relatively stable in Australia, the ageing of the population and the greater longevity of individuals have led to growing numbers of people, especially older people, suffering disabilities and severe or profound limitations in core activities.2 Within New Zealand there is not a lot of research into chronic illnesses (also known locally as ‘long-term conditions’) as a discrete entity, but it is estimated that, in 2008, 2 in every 3 New Zealand adults were diagnosed with at least one chronic condition.12 A recent analysis of Australian data showed that a male’s life expectancy at age 65 increased by 1.5 years between 1988 and 2003 but, of this gain, 67% (1 year) was spent with disability, including 27% spent with profound or severe core activity limitation. Females increased their life expectancy at age 65 by 1.2 years over the same period, and for them more than 90% of the gain was estimated to be spent with disability, including 58% spent with profound or severe limitation.2 Indeed, hospital admissions are a common feature of the years gained. Of the 2.5 million hospital episodes of care completed in Australian hospitals in one year, people aged 65 years and over represented 35% of the total cases admitted.13 Furthermore, the level of disability experienced by older patients increases the likelihood that they will need invasive technologies such as biventricular pacemakers, implantable cardiac defibrillators and specific drugs. These provide patients with a number of complex issues to consider in managing their lifestyle.

Depression frequently accompanies or precipitates chronic illness and has been noted as a very important symptom to manage. Depression is also a chronic illness itself. Therefore, screening for depression has been recommended as part of all chronic illness management programs. A range of chronic illnesses have been associated with depression, including asthma, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, cancer, dementia, chronic pain and Parkinson’s disease. In fact, beyondblue suggests that more than 40% of Australians with a mental disorder have a chronic physical illness and that having a chronic illness puts a person at greater risk of developing depression.14 For people with a chronic illness, depression makes recovery and management more difficult. It can make it harder to find the energy to eat healthily, exercise and take medications regularly, making adherence to, and compliance with, health action plans more difficult.

Patient and family assessment

Care provision for the initial diagnostic and acute exacerbation phases of a chronic illness is often managed in a hospital setting, but the majority of care is usually, and appropriately, provided outside of the acute care setting. This means that usually the individuals affected, and their families, provide the majority of care while they live in their own homes or in assisted-living or residential aged-care facilities, with intermittent support from ambulatory care settings. Thus the patient and family must manage the effects of the chronic illness on their daily functioning. This impact can be diverse and it is important to assess for each individual.15 Functional health assessment for chronic illness should cover activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, eating, toileting and transport, as well as the patient’s level of social support. It is also important to include instrumental ADLs, such as using a telephone, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, doing laundry, arranging transportation, taking medications and handling finances. The assessment should take into account the person’s age and life demands, as well as their capacity to manage multiple comorbidities. The assessment and monitoring of these functions is often used to predict the level of supportive health, personal and domestic care required. An inability to perform any of these activities safely or efficiently can affect the patient’s quality of life and the level of support they need in order to live independently in the community.

Few individuals can manage their chronic illness without the support and care provided by family and friends.15 Carer strain and burden vary with complex chronic illnesses, but usually include stress and worry related to social, financial and physical aspects. These concerns need to be assessed and considered as part of the patient’s health assessment and action planning to manage their chronic illness. The tasks of an informal carer may include: (1) assuming an increased physical burden of work because of the need to add tasks previously undertaken by the chronically ill person; (2) dealing with the changes in the progression of the disease; (3) coping with feelings of being overwhelmed both psychologically and physically; and (4) dealing with changes in social roles and identity for both themselves and the patient because of the illness. The role of the carer in supporting the person with heart failure to provide better self-care has been explored by Gallagher and colleagues,16 and their recommendations for using carer support in improving self-care capacity are summarised in Box 69-1.

BOX 69-1 Social support and self-care recommendations to improve outcomes using carers

• Social support provided by partners of a quality and content that matches heart failure patients’ needs is associated with better self-care, particularly in the key areas of taking medications, managing fluid intake, consulting health professionals for weight gain, having a flu shot and taking regular exercise.

• When assessing heart failure patients’ capacity for self-care, the partner’s relationship with the patient should also be assessed.

• Carers, especially partners, should be considered as integral to the treatment and care of heart failure patients.

• New teaching or counselling strategies are needed to optimise self-care in heart failure patients and their partners.

Source: Gallagher R, Luttik M, Jaarsma T. Social support and self-care in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011; 2.

Carer strain and social support affect care needs and management strategies.17 A review of domestic support needs and carer factors will enable the patient’s case manager to effectively plan interventions that meet the goals and needs of the patient and their family during the different phases of the chronic illness. The case manager, patient and family should work together to establish the most important illness symptoms and management plans to follow, thereby ensuring that the patient understands the priority steps in their health action plan. Managing multiple medical problems simultaneously can be a challenge for both healthcare professionals and the patient, and sometimes makes for a very confusing set of options for patients to navigate.

Management of chronic illness

MODELS OF CHRONIC ILLNESS CARE

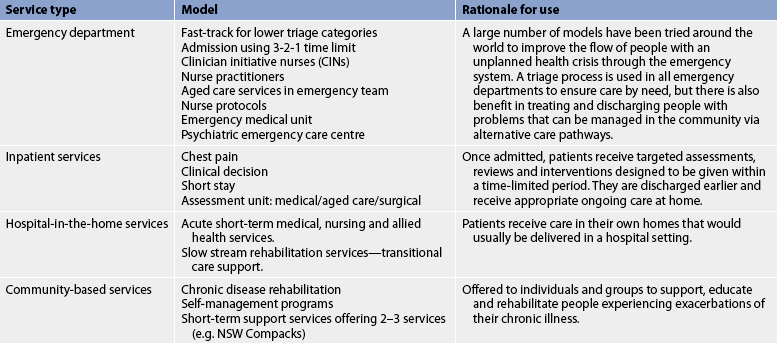

Given the complexity of chronic illnesses there is a corresponding need to provide care that allows for a connection with multiple health professional groups and specialists, while also supporting patients’ efforts at self-management. Health system planning and redesign have led to a number of different standardised service delivery models that can be used to meet the ongoing care needs of people with chronic diseases requiring hospital care.18 By optimising service delivery systems and testing redesigned models of care, local health services are aiming to meet the increased care needs of the community using more flexible service delivery models. Commonly reported models that offer the chance to redesign parts of the existing health system are outlined in Table 69-2. New models of care are being introduced to improve patient and carer outcomes, especially around the crisis points of the chronic care journey, such as unplanned hospital admissions and acute exacerbations of the chronic illness.

A recent systematic review of disease management interventions for patients with chronic heart failure (see Box 69-2) found that there are three intervention models: (1) multidisciplinary interventions (holistic approaches that bridge the gap between hospital admission and discharge, delivered by a team); (2) case management interventions (intense monitoring of patients following discharge, often involving telephone follow-up and home visits); and (3) clinic interventions (follow-up in a chronic heart failure clinic).19 These models are summarised in the Table 69-3. The review found weak evidence that case management interventions are associated with a reduction in readmissions for heart failure, although the authors concluded that it was difficult to identify the effective components of case management interventions. A randomised controlled trial that examined the management of heart failure using multidisciplinary interventions showed reduced heart failure-related readmissions in the short term.20

BOX 69-2 Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the evidence tell us?

Interventions with evidence of a positive effect

Interventions for which further evidence is needed

• Increasing the size of general practice surgeries

• Changing out-of-hours primary care arrangements

• Chronic care management in primary care

• Cost-effectiveness of general practitioners in the emergency department

• Access to social care in the emergency department

Source: Purdy S. Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the research evidence say? The King’s Fund response to the Department of Health’s public consultation on an information revolution. London: King’s Fund; 2010.

TABLE 69-3 A systematic review of disease management interventions for patients with chronic heart failure

| Intervention | Approach | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary interventions | A holistic approach bridging the gap between hospital admission and discharge, delivered by a team | Overall concept embedded in multidisciplinary teams— supports an interprofessional, collaborative approach to health service provision. |

| Case management interventions | Intense monitoring of patients following discharge, often involving telephone follow-up and home visits | Case management in the community and in hospital is not effective in reducing generic admissions. There is limited evidence to suggest that it may be effective for patients with heart failure. Assertive case management is beneficial for patients with mental health problems. |

| Clinic interventions | The general practitioner deals only with chronic diseases for that clinic | Specialised clinics or mini-clinics (where a group delegates a general practitioner to deal with only chronic diseases for that day) were also found to be beneficial. Larger clinics in practices are not necessarily associated with lower levels of emergency admissions. |

Source: Purdy S. Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the research evidence say? The King’s fund response to the Department of Health’s public consultation on an Information revolution. London: King’s fund; 2010.

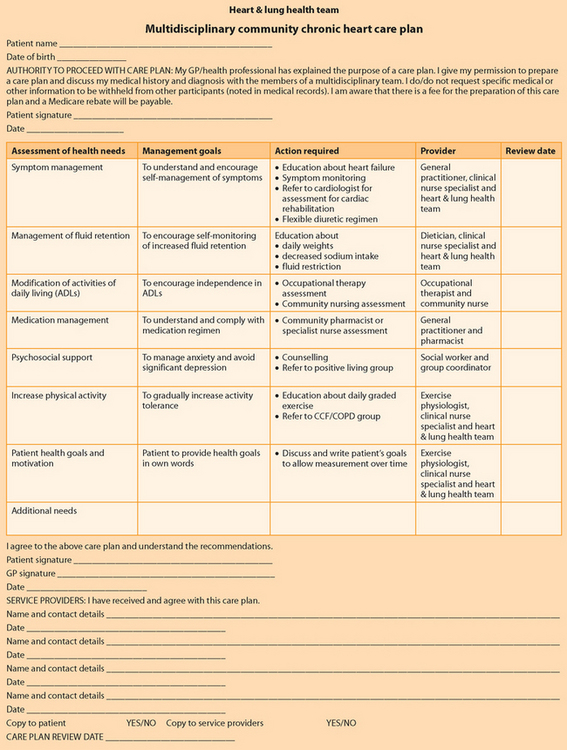

Using strategies that promote self-management may mean that nurses are able to implement care planning that ensures each patient with a chronic illness has a structured plan that drives their care. A care plan should be the cornerstone of chronic disease management and it should receive input from all the healthcare team members who assist the patient in planning their care. A sample care plan is provided in Figure 69-2.

PRINCIPLES OF SELF-MANAGEMENT

While the trajectory of most chronic illnesses includes hospital admissions, the mainstay of healthcare for chronic illnesses is self-management. Self-management is an umbrella term that encompasses not only self-care—that is, the specific tasks that people carry out on a day-to-day basis to manage their condition—but also disease management, which refers specifically to the use of health interventions, such as medications, to treat the illness.21,22 It is estimated that 70–80% of older individuals living with a chronic condition can reduce their disease burden and prevent hospital admissions through the implementation of appropriate self-management strategies.23 People who have participated in self-management programs and learned strategies to manage their condition experience a reduction in symptoms and hospital admissions, as well as increased participation in healthy activities.24–26

The key requirements for individuals to self-manage their chronic illness appropriately include:

• a clear understanding of the illness and the health outcomes sought

• active engagement in their own disease management processes

• a high level of self-efficacy (confidence in one’s own ability to do what is required to reach a goal)

• health literacy.27

It is crucial for successful self-management that individuals see themselves as their own main carers and use health professionals as support. This process of engagement is best explained by social cognitive theory. In this theory three central factors (outcome expectancies, self-efficacy and decision making) contribute to the individual’s level of engagement, or participation, in the learning that is needed and the behavioural changes that are necessary to self-manage their condition.28 In terms of outcome expectancies, the individual must perceive a threat in their illness situation and believe that they have the capacity to somehow reduce this threat. They must consider that they have the skills and confidence necessary to undertake the behaviours required (self-efficacy). They must then weigh up the balance between the effort required and the reduction in risk they may achieve (decision making). Engagement is vital because people with chronic illness must undertake potentially complex behaviours and make unwelcome changes to their lives while at the same time experiencing an array of disabling symptoms.

REQUIREMENTS FOR SELF-MANAGEMENT

The skills required to self-manage a chronic illness may be grouped into those needed to deal with the illness, those needed to continue as normal a life as possible and those needed to deal with emotions.15

Dealing with chronic illness

To deal with the illness the individual needs to understand the disease and the treatments, and the sequelae of both. Monitoring key signs and symptoms of the disease, interpreting changes in these symptoms, initiating treatments and determining when help is needed are essential. So too is taking medications and undertaking treatments to manage the symptoms of the illness and then assessing the relative benefits and costs of these treatments. Learning how to prevent and manage a crisis is also a vital skill to develop, as most chronic illnesses have the potential for acute exacerbations of symptoms that may result in further disability or even death.9

A major task for the patient and family is to learn to prevent and manage a crisis. Preventing a crisis involves understanding what the potential for the crisis is and then learning how to prevent or modify the threat. This often comprises adhering to a prescribed medical regimen. Patients also need to know the signs and symptoms of the onset of a crisis. Depending on the chronic illness, these may occur suddenly (e.g. seizure in a patient with seizure disorder) or slowly (e.g. heart failure in a patient with hypertension). It is equally important for the patient and family to develop a plan to manage the crisis. For example, a person with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) must have some understanding of their disease, the potential for exacerbations, the signs and symptoms of exacerbations, their medications and treatments. They must regularly assess their level of dyspnoea and be alert for the first signs of a respiratory tract infection. When these signs occur, they must begin following their crisis action plan. Finally, they must decide whether their signs and symptoms warrant medical care.

Maintaining a ‘normal’ life

The self-management skills needed to maintain a relatively normal daily life within the boundaries of chronic illness include managing regular aspects of life such as housekeeping, food purchasing and preparation, social roles and relationships.15 It is important that the individual learns about the pattern of disease symptoms such as typical onset, duration and severity so that lifestyle patterns can be changed accordingly.

A key component of maintaining a relatively normal daily life is ensuring good general health, which can be achieved by following a healthy diet and taking exercise. Considerable problem-solving skills may also be required to balance illness management requirements and the symptoms that occur on a daily basis, and to garner resources and support. For example, an individual with COPD may plan their day very carefully to spread out energy-consuming activities in order to avoid intense periods of dyspnoea. They may have to arrange transport with a friend or family member to a social event to minimise walking and to avoid exposure to potential sources of infection on public transport. All of these activities depend on their ability to negotiate and manage their plans with family and friends.

Dealing with emotions

People with chronic illness may attempt to normalise their interactions with others by managing their symptoms and hiding their disability or disfigurement.9 They may try to demonstrate that they can function the same as someone without a disability or chronic illness—a common example of this is the individual with chronic lung disease who stops walking to catch their breath but appears to be inspecting a plant or looking in a shop window. Managing chronic illness requirements and skills is demanding—the more so when compounded by the changing emotions that people experience with chronic disease. These emotions are likely to include sadness, isolation, anger and frustration. An important self-management skill is the ability to counter, and work with, negative emotions. Social isolation is a common consequence of chronic illness, so maintaining social interaction is essential.

SELF-EFFICACY IN SELF-MANAGEMENT

The concept of self-efficacy in social cognitive theory helps to explain how individuals develop the complex self-management skills required to manage their chronic illness, what they are prepared to do to help themselves and their persistence in the face of adversity. To put it simply, self-efficacy is what people think they can do with their knowledge, skills and experience in a variety of circumstances. Self-efficacy is not confidence. It relates to specific domains—for example, a person can be very competent in driving a car but need assistance in driving to the correct location. Thus they need support with developing sequenced skills that lead to independent driving behaviour. With an understanding of self-efficacy, nurses can support the patient’s development of self-management skills with their chronic illness.

There are four ways that individuals develop self-efficacy: (1) by experiencing success; (2) seeing others experience success, especially following failures; (3) being persuaded that they can succeed; (4) and experiencing the physical and emotional feelings that accompany skill development.28 Nurses can help patients with chronic illness to experience success by breaking down the components of self-management into achievable units and by providing positive feedback when achievements occur. Nurses can also provide positive role models through support groups, so that patients can learn by watching the efforts, corrections and successes of others with similar illnesses. People with chronic illness gauge their self-efficacy on how they feel physically and emotionally when they think about or undertake an action. It is the nurse’s role to help guide these interpretations. As an example, the increased dyspnoea that occurs with exercise can be interpreted as a positive indication of effort rather than proof of decline in function.

It is important for nurses to be alert for negative persuaders, because social persuasion can have a powerful negative effect on self-efficacy. In addition, given the important role of interpreting emotion in building resilient self-efficacy, it is vital that depression is detected and managed promptly. Depression leads to more negative interpretations of the development of self-management skills and the impact of these skills on outcomes.28 Depression decreases the motivation to engage and make the effort required both to learn self-management skills and to self-manage.

ENCOURAGING SELF-MANAGEMENT

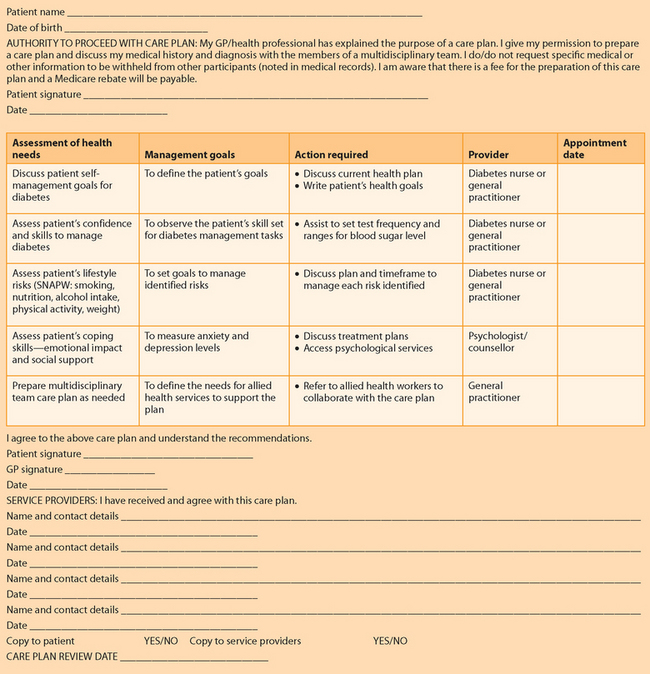

Self-monitoring strategies for patients include developing an early warning system, such as daily weights to detect fluid overload for patients with heart failure. Self-monitoring strategies work when the patient knows the range of the physical attribute they are measuring (e.g. blood sugar level) and has an action plan that assists in interpreting the results and providing appropriate action to manage any variation from the reference range (e.g. a rise in blood sugar level). Figure 69-3 contains an example of a care plan to encourage self-management of blood sugar levels.

A range of patient self-monitoring activities can be reported back to the specialist nurse in either a clinic or a practice setting and may be enhanced by telehealth using computers, telephone or direct feedback from the device to the supervising health practitioner. Self-monitoring activities can be supported alongside health coaching interventions and case management. For chronic illnesses there is now a big emphasis on using telephony-based services. These services can take incoming telephone calls from patients that report problems or seek advice and generate regular outgoing calls to establish a patient’s current health status and to work to prevent any relapses or exacerbations.

Support for patient self-management requires the health organisation to take a standardised and consistent approach, such as the Stanford method championed by Lorig.15 Health staff preparing to teach self-management principles to patients may benefit from using a model or an approach that fits in with their own health beliefs and resources. When choosing a model, the organisation needs to consider the following questions:

• Which model fits our overall aim for chronic disease care?

• What is our training budget? What training can we afford to implement?

• What skills do we have as a team?

• What challenges are we likely to face? How can we overcome them?

Planning the approach allows the organisation to take account of local factors such as resource level, geographical challenges and the availability of enabling factors such as telephones, transport and the support of general practitioners and specialists.

In Australia and New Zealand a range of models are used, the most common being the Flinders University Model for Chronic Condition Self-Management and the Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (known in Australia as the Better Health Self-Management Program) from Stanford University.29–31 In addition, various health behaviour change theories have been developed such as motivational interviewing and health coaching, with various delivery strategies including group-based programs and expert peer leadership.32 These approaches can be offered to patients from a variety of healthcare settings, including general practices, community health centres and local council or leisure centres, often without the need for supervision by health professionals. However, reinforcing the principles of the chosen approach and encouraging self-monitoring to ensure that patients are successful in their self-management may be part of the nurse’s monitoring and surveillance role as a case manager. Nurses who take such roles may also be known as care navigators (professionals who find the right point of care at the right time).

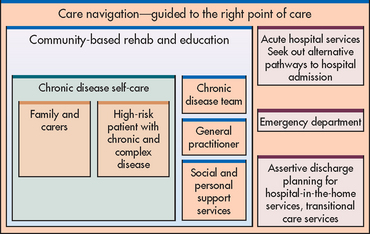

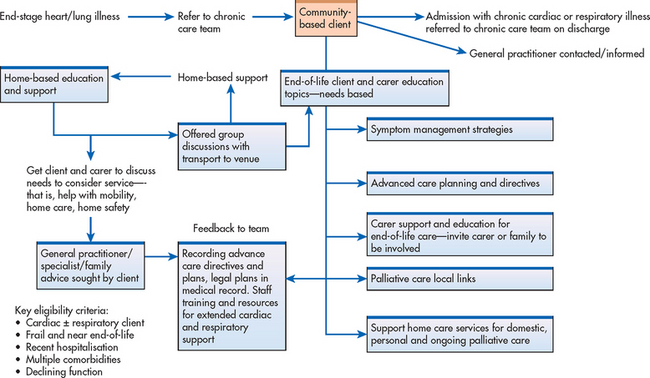

CARE NAVIGATION

Care navigation is a system of care that is designed to improve patient experiences and health outcomes for the most at risk, vulnerable, frail aged and chronic illness sufferers with complex care needs. It is achieved using a system redesign process to improve integration and coordination of care across and between services, both in the hospital and in the community.33 Care navigation programs help steer patients to the most appropriate point of care. They offer ongoing community coordinated care (often through the patient’s general practitioner), which includes support and help to avoid unnecessary visits to the emergency department and inpatient treatment. Patient and carer engagement is a key component of this approach and the model is designed to improve satisfaction with, and use of, agreed healthcare plans. Patients and carers generally welcome their general practitioner’s greater involvement in their healthcare planning and delivery, and report a better healthcare experience when their hospital admissions are guided and monitored by a care navigation system.33 The care navigation process between the community and acute care service sectors is illustrated in Figure 69-4.

Improved outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses are achieved with care navigation that directs those who are frail and vulnerable to the most effective point of care. This active navigation enables patients to be treated appropriately when they have an acute exacerbation. Care may be provided at home, and emergency department or inpatient care may be substituted with a specialist chronic care or hospital-in-the-home service.

CARE COORDINATION

Care coordination is a key attribute of successful case management. Patients with multiple chronic illnesses move through increasingly specialised parts of the health system, which can leave them having to manage conflicting advice for their complex symptoms and needing to choose which health action plan to follow to improve their outcome.34

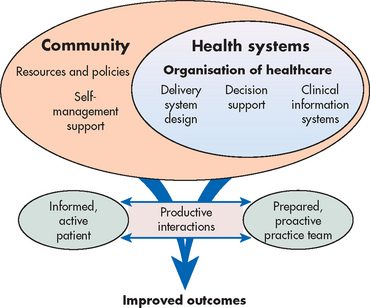

Key deficiencies in care coordination include: (1) rushed practitioners not following established practice guidelines; (2) lack of active follow-up to ensure the best outcomes for patients; and (3) patients being inadequately trained to manage their illnesses.35 Overcoming these deficiencies requires nothing less than the transformation of the healthcare system from one that is essentially reactive, responding mainly when people are sick, to one that is proactive and focused on keeping people as healthy as possible.33 To address these deficiencies, the McColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation has created the chronic care model,36 which summarises the basic elements for improving healthcare at the community, organisation, practice and patient levels (see Fig 69-5). Key elements of the model include the community, the health system, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support and clinical information systems. Evidence-based change concepts under each element, in combination, foster productive interaction between informed patients, who take an active part in their care, and providers with resources and expertise. The model can be applied to a variety of chronic illnesses, healthcare settings and target populations. The bottom line is healthier patients, more satisfied healthcare providers and cost savings.

Figure 69-5 The chronic care model.

Source: The Group Health Research Institute. Available at www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_Chronic_Care_Model&s=2, accessed 14 January 2011.

One of the most important aspects of care coordination is the classification of risk for future emergency readmission. At present, this assessment occurs in three ways: clinical knowledge, threshold modelling and predictive modelling.

• Clinical knowledge is the default position in most health services whereby clinicians identify those they consider to be at risk. Although clinicians may be able to identify those patients currently at high risk, they are less able to identify those who may be at risk in the future.37

• Threshold modelling, which is rules based, identifies those at high risk who meet a set of criteria. Case finding has usually been based on threshold modelling, such as identifying patients with repeated emergency admissions as a marker for high risk of future admissions. An example of this type of model is the Hospital Admission Risk Profile (HARP) calculator shown in Box 69-3.38

• Predictive modelling uses data such as the patient’s age, gender and sociodemographic characteristics in a statistical model to calculate the risk of future admission. Predictive modelling is thought to be the best available technique and good examples include the Patients at Risk of Re-Hospitalisation (PARR) model and the Scottish Patients at Risk of Readmission and Admission (SPARRA) model from the UK.37,39

BOX 69-3 Hospital Admission Risk Profile (HARP) calculator

Part A: clinical assessment

1. Presenting clinical symptoms

Diagnosis of chronic respiratory condition (1)

Diagnosis of chronic cardiac condition (1)

Diagnosis of complex care needs in frail aged, such as dementia, falls or incontinence (1)

Diagnosis of complex care needs in people less than 55 years of age, such as mental health illness (1)

Comorbid diagnosis of diabetes and/or renal failure and/or liver disease (1)

2. Service access profile

Acute admission/presentation (more than once in the last 12 months) (4)

No regular GP follow up (regular medical check-ups 2 times a year) (3)

Reduced ability to self-care (to the extent it impacts on disease management) (3)

3. Risk factors

Overweight (guide BMI 26–35) (1)

Underweight (guide BMI <19) (1)

High cholesterol (total cholesterol >5.5 mmol/L, HDL <1.0 mmol/L, LDL >2.0 mmol/L) (1)

High blood pressure (>140/90 mmHg or on medication for high blood pressure) (1)

Physical inactivity (less than 30 mins/day and 4 days/week) (1)

Polypharmacy (>5 medications with difficulty managing them) (1)

Part B: factors impacting on self-management

5. Psychosocial factors and demographic issues

Mental health (depression, anxiety or psychiatric problems) Y/N

Disability (intellectual, physical, visual, hearing) Y/N

Access to suitable transport to care services Y/N

Financial issues (inability to afford health services and/or medications) Y/N

CALD or Aboriginal health beliefs Y/N

Illiterate and/or limited English Y/N

Unstable living environment Y/N

Rate the impact these combined factors have on the person’s ability to self-manage their condition:

No impact (on ability to self-manage) (0)

Low impact (on ability to self-manage) (7)

6. Readiness to change assessment (choose one only)

No capacity for self-management (cognitive impairment, end-stage disease) (4)

Pre-contemplation (not ready for change) (3)

Contemplation (considering but unlikely to change soon) (3)

Preparation (intending to take action in the immediate future) (2)

Action (actively changing health behaviours but having difficulties maintaining plan) (1)

Maintenance (maintained behaviour for >6 months) (1)

Relapse (a return to the old behaviour) (3)

Total score for self-management impact (B) /19

Source: Taylor S, Bestall J, Cotter S, Falshaw M, Hood S et al. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (2).

Transitions and care coordination in chronic illness care

Traditionally, chronic illness care has been provided by independent health specialist groups targeting individual conditions, with limited collaboration occurring between groups for comorbid conditions. However, many changes are being made to this traditional pattern of care to provide more support for patients as they transition between different phases of their illness and between different specialist groups.40 Care planning and case management now offer patients support in navigating between sectors of the healthcare system. The current health systems in Australia and New Zealand use a range of approaches and models of care that site these services in the acute, community and primary healthcare sectors. The sharing of accurate and current health information between these sectors is vital to quality of care for patients with chronic illness and varies according to the local level of trust, integration and collaboration between health and community partners. During an acute unplanned admission a patient’s health summary needs to be current and available at the point of care—usually the emergency department or assessment unit—or to the outreach acute health staff. The ability to do this while observing privacy and access concerns has limited the use and sharing of electronic tools and plans in Australia. In New Zealand, all general practitioners have electronic clinical notes and all patients have a unique National Health Index (NHI) number. In addition, the New Zealand Privacy Act does not limit the sharing of clinical details between providers who are caring for patients in common. In all health domains the goal should be the greater integration of information technology systems between all sectors; this will mean a more accurate and timely transfer of health information from patient records and care plans.

In Australia, there have been ongoing discussions regarding the use of electronic health records, shared care planning, and telecare and telehealth systems to improve communication about patients with chronic illnesses and their care needs. Current discussions are based on improving the effectiveness of sharing data from assessment tools (such as the Ongoing Needs Identification [ONI] tool) and using the data to inform staff of patient needs for community support services on leaving hospital.41 Effective planning for the transfer of care when patients leave the acute health system is summarised in Box 69-4.

BOX 69-4 Planning for discharge: essential attributes of discharge interventions that can potentially reduce readmissions

• Early and complete assessment of discharge needs and medication reconciliation.

• Enhanced patient (and carer) education and counselling specifically focused on gaining an understanding of the patient’s condition and its self-management.

• Timely and complete communication of management plan between clinicians at discharge when patient care is transferred from hospital staff to primary care teams.

• Early post-acute follow-up within 24–72 h for high-risk patients with either doctor or nurse.

• Early post-discharge nurse (or pharmacist) phone calls or home visits to confirm understanding of management and follow-up plans in high-risk patients.

• Appropriate referral for home care and community support services when needed.

Source: Scott I. Preventing the rebound: improving care transition in hospital discharge processes. Australian Health Review 2010; 34:445–451.

An example of the increased management of the transition between acute and community healthcare in Australia is the Chronic Care for Aboriginal People (CCAP) program, which was developed from a number of established New South Wales Department of Health initiatives in an attempt to address the gaps in healthcare provision and to improve access to, and use of, chronic care services for Aboriginal people in New South Wales.42 The components of the model are presented in Figure 69-6. This model has been used to provide the framework for a 48-hour follow-up after discharge from hospital to enable appropriate ongoing care.

CASE MANAGEMENT: THE NURSE’S ROLE

A key feature of contemporary chronic illness care is case management. Case management assumes that patients with chronic complex and multiple needs require a range of services and that this can be achieved in a seamless manner. Case management is based in service provision arrangements that require different responses from within organisations and across organisational boundaries. Case managers come from a range of health backgrounds, but the underlying philosophy is that service provision is seen as being patient-driven, rather than organisationally-driven. Nurses often have the responsibility for case management during the patient’s transition phase, as they move between hospital and home. Ongoing community-based advocacy is often the domain of community workers who may come from a range of professional backgrounds.19 The case manager is the primary healthcare contact for the patient and family and provides a consistent planning approach to enable the patient’s needs to be met.

To be competent in case management, nurses need the following core skills and competencies:

• advanced level professional practice, including self-directed learning, managing risk, having authority to act on behalf of patients, and having higher level communication and negotiation skills

• care coordination and case management (brokerage and provision) skills

• ability to manage cognitive impairment

• ability to use population and individual information to support decision making

• medicine management (including assessment, review and prescription)

• ability to liaise and work with, between and across agencies and partners

• clinical management of long-term conditions (particularly the interplay between multiple diseases)

• ability to work in home and community settings

• supporting and promoting self-managed care

Nurses working with patients with chronic illnesses work across the acute hospital, community and primary healthcare sectors. Acute hospital services and clinics have been established to manage a range of chronic illnesses, including diabetes mellitus, heart failure, asthma, COPD and cardiovascular disease. The traditional role of the community health nurse has been enhanced to encompass general practice nurses, and rural and remote nurses. The range of primary healthcare nursing roles includes enrolled and registered nurses working as practice nurses, team members and leaders, and nurse practitioners. With greater need for service integration and multiple alternative care pathways, the skills of care navigation and case management are critical for nursing care providers to develop. For example, nurses in residential aged care facilities, such as hostels and nursing homes, are increasingly accepting greater responsibility for the management and care of a range of chronic illnesses. Care pathways ultimately need to include end-of-life and palliative education and the support pathways that are also necessary at the end of the chronic illness journey. The SHALT education and support pathway shown in Figure 69-7 is an example of one pathway that is useful for navigating end-of-life education for patients with end-stage cardiac and respiratory illnesses.34

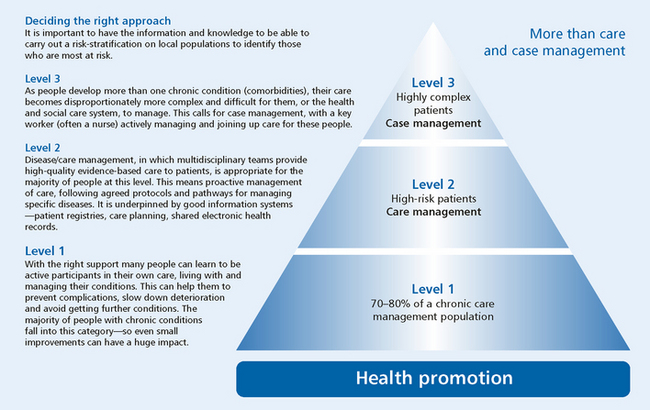

The chronic disease pyramid shown in Figure 69-8 illustrates the nurse’s multiple roles in caring for patients with chronic illness. Nurses need to have the skills and knowledge to offer a range of patient activities from intensive case management, care coordination and self-management support to population-based strategies including primary and secondary disease prevention.35

Developing the health workforce to meet chronic illness needs

The health workforce required to provide for the care needs of those with chronic and complex illnesses needs to be multidisciplinary and coordinated to achieve the best outcomes for patients.43 In Australia, Medicare provides specific remuneration to general practitioners based on their chronic care practices and whether or not care planning includes members of the allied health team, nurses, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists and so on. In New Zealand since 2000 national policy has been directed at improving the population’s health. These policies include the New Zealand Health Strategy, the New Zealand Primary Care Strategy, the development of Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), capitation payments, Care Plus and Services to Improve Access funding.44 Nurses often provide leadership in these specialty chronic disease management programs, which may be offered as outreach or clinic services in the community. Nurses working within the general practice setting in primary healthcare also receive financial rewards and training opportunities to assist in the monitoring, management and recall of patients with a range of chronic illnesses.

Currently, Australia and New Zealand are using case management, multidisciplinary teams and clinics to provide community-based healthcare to support patients in the community.44 Health service planners are examining the best way to prepare staff in the core skills needed for developing patient self-management. Health staff will then be able to introduce self-management approaches into patient education sessions, so that patients are not just provided with healthcare information but also supported to make and sustain long-term behaviour changes.

Workforce training and development are an important part of building system capacity to manage the increasing wave of people with chronic illnesses. The core skills needed by health professionals to enable them to effectively support patients in self-management training have been identified as problem-solving, targeting, goal setting, planning, identifying follow-up needs, reflective listening, asking open-ended questions, identifying a person’s readiness to change, assertiveness skills, depression screening and assessing suicide risk.45

Conclusion

Nurses play a valuable role in assisting patients to manage their chronic illnesses. Patients and their carers require a variety of levels of support, empowerment and education from nurses during the different phases of their chronic illnesses. Patients who require support in learning how to self-manage their condition make up 70–80% of the population with chronic conditions. Nurses can develop their own skills and competencies to enable patients and their carers to take on effective self-management. High-risk patients with complex chronic illnesses who need their condition actively managed to prevent further complications and promote wellbeing may need specialist disease management from multidisciplinary teams.46 Patients with complex and multiple conditions need high-quality, evidence-based case management in which their needs are identified and met by skilled practitioners, often nurses, working within an integrated care system.

The patient with chronic illness

CASE STUDY

Patient background

Mrs Clare Giardini is a 69-year-old woman who has had three presentations in the last several months with shortness of breath. She lives in her own home with her 2 adult children, one of whom is a specialist paediatric nurse. Mrs Giardini has a history of osteoarthritis, non-insulin-dependent diabetes and asthma. A recent echocardiogram showed systolic dysfunction and a poor left ventricular ejection fraction, and Mrs Giardini is noted to have chronic controlled atrial fibrillation.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. What social factors and assessment questions or tools would be useful to use with this patient?

2. Identify the community health and support services that are available in your health district for this patient.

3. What planning and assessments around the transition process from hospital to home would allow this patient to effectively self-manage her conditions at home?

1. Vos and Carter found that a large impact on improving a population’s health can be achieved by:

2. Many factors contribute to chronic disease complexity and these are characterised by:

3. Australian and New Zealand evidence suggests that most of the recent gain in life expectancy for individuals:

4. Depression frequently accompanies or may precipitate chronic illness. Depression makes recovery and management more difficult because it can make it harder for people:

5. Measuring carer strain and completing social care assessments are an important part of assessing the impact of these factors for different phases of the chronic illness journey. This is because:

6. A holistic assessment tool for the patient with chronic illness needs to:

7. Self-management is an umbrella term that encompasses:

8. Preventing and managing a crisis are vital skills to develop and the patient and family are expected to:

9. People with chronic illnesses need to know the signs and symptoms of the onset of a health crisis. Depending on the chronic illness, these signs and symptoms may include:

10. Self-monitoring strategies include the development of an early warning system such as:

1 World Health Organization (WHO). Chronic diseases. Available at www.who.int/topics/chronic_diseases/en/. accessed 28 January 2011.

2 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Australia’s health, 2008. The eleventh biennial health report of the Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. Canberra: AIHW, 2008.

3 New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZMOH). Data and statistics. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/dataandstatistics-subjects. accessed 20 February 2011.

4 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Chronic diseases and associated risk factors in Australia, 2006. Canberra: AIHW, 2006.

5 Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aus. 2008;189:72–77.

6 Vos T, Carter R, Barendregt J, Mihalopoulos C, Veerman JL, et al. Assessing cost-effectiveness in prevention (ACE–Prevention): final report. Brisbane: University of Queensland, 2010.

7 Aspin C, Jowsey T, Glasgow N, Dugdale P, Nolte E, O’Hallahan J, Leeder S. Health policy responses to rising rates of multi-morbid chronic illness in Australia and New Zealand. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2010;34(4):386–393.

8 Armstrong BK, Gillespie JA, Leeder SR, Rubin GL, Russell LM. Challenges in health and health care for Australia. Med J Aus. 2007;187:485–489.

9 Corbin J, Strauss A. A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework. Res Theor Nurs Pract. 1991;5:155–174.

10 New South Wales Department of Health. Chronic care for Aboriginal people, model of care. North Sydney: New South Wales Department of Health, 2010.

11 Malak A. Welcome to diversit-e. Diversit-e 2010; 3.

12 New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZMOH). A portrait of health: key results of the 2006/2007 New Zealand health survey. Wellington: NZMOH; 2008. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/portrait-of-health accessed 28 January 2011.

13 Karmel R. Older Australians in hospital. AIHW bulletin no. 23. Canberra: AIHW; 2007. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10418 accessed 28 January 2011.

14 Beyondblue. Chronic illness and depression and anxiety. Available at www.beyondblue.org.au/index.aspx?link_id=4.1174. accessed 10 February 2011.

15 Lorig K, Holmans H, Sobel D, Laurent D, Gonzalez V, Minor M. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions. Self-management of heart disease, arthritis, diabetes, asthma, bronchitis, emphysema and others, 3rd edn. Boulder: Bull Publishing Co, 2006.

16 Gallagher R, Luttik M, Jaarsma T. Social support and self-care in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011:2.

17 Carers NSW. Caring for the carer. Carers News. Available at www.carersnsw.asn.au, October–November 2008. accessed 28 January 2011.

18 Sugarman J, ed. Clinical and service integration. London: King’s Fund, 2010.

19 Purdy S. Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the research evidence say? King’s Fund response to the Department of Health’s public consultation on an information revolution. London: King’s Fund, 2010.

20 Taylor S, Bestall J, Cotter S, Falshaw M, Hood S, et al. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005.

21 Chang AT, Haines T, et al. Rationale and design of the PRSM study: pulmonary rehabilitation or self-management for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what is the best approach? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(5):796–800.

22 Niesink A, Trappenburg J, et al. Systematic review of the effects of chronic disease management on quality-of-life in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2233–2239.

23 Department of Health. The national health service and social care long-term conditions model. Available at www.dh.gov.nk/en/Policyguidance/Healthandsocialcaretopics/Longtermconditions/DH_4130652. accessed 29 January 2011.

24 Effing T, Monninkhof EM, van der Valk PD, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden CL, et al. Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. CD002990.

25 Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus S. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disorders. 2006;6:43.

26 Foster G, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. CD005108.

27 Boyages S. Chronic and complex illness. Diversit-e 2010.

28 Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman & Co, 1997.

29 Fiandt K. The chronic care model: description and application for practice. Topics in Adv Practice Nurs eJournal. Available at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/549040, 2006.

30 Lorig K. Self-management of chronic illness: a model for the future (self-care and older adults). Generations. 1993;17:11–14.

31 Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definitions, outcomes and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7.

32 Glanz K, Rimer BK, Marcus Lewis F. Health behaviour and health education, 3rd edn. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2002.

33 Australian Resource Centre for Healthcare Innovation (ARCHI). Map: current patient journeys in self-management. Available at www.archi.net.au/e-library/moc/complex/self/implementing/mapjourney. accessed 20 February 2011.

34 Sutherland Heart and Lung Team. Community referral pathways to exercise programs. Available at www.shiregps.org.au/documents/Practice%20Nurse%202010/referral%20pathways.pdf. accessed 20 February 2011.

35 New South Wales Department of Health. Chronic disease: better management of people with chronic disease in HealthOne NSW services. Available at www.health.nsw.gov.au/initiatives/healthonensw/chronic_session.asp. accessed 20 February 2011.

36 The Group Health Research Institute. The chronic care model. Available at www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=The_Chronic_Care_Model&s=2. accessed 14 January 2011.

37 King’s Fund. Predicting and reducing readmission to hospital. Available at www.kingsfund.org.uk/current_projects/predicting_and_reducing_readmission_to_hospital. accessed 20 February 2011.

38 Sager MA, Rudberg MA, Jalaluddin M, Franke T, Inouye SK, et al. Hospital Admission Risk Profile (HARP): identifying older patients at risk for functional decline following acute medical illness and hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(3):251–257.

39 National Health Service, National Services Scotland. Scottish patients at risk of readmission and admission. Available at www.isdscotland.org/isd/servlet/FileBuffer?namedFile=2008_06_16_SPARRA_All_Ages_Report.pdf&pContentDispositionType=inline. accessed 20 February 2011.

40 Armstrong T, Kalenchuk K. Keeping hospitalizations in check. Provider. 2007;33(3):53–55.

41 Queensland Department of Health. Ongoing needs identification tool. Available at www.health.qld.gov.au/hacc/html/oni-tool.asp. accessed 20 February 2011.

42 New South Wales Department of Health. Chronic Care for Aboriginal People model of care. Available at www.health.nsw.gov.au/initiatives/chronic_care/aboriginal/index.asp, 2008. accessed 20 February 2011.

43 Curry N, Ham C. Clinical and service integration: the road to improved outcomes. Available at www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/clinical_and_service.html. accessed 20 February 2011.

44 Rea H, Kenealy T, Wellingham J, Moffitt A, Sinclair G, et al. Chronic care management evolves towards integrated care in counties Manukau, New Zealand. NZ Med J. 2007;120(1252):U2489.

45 Kubina N, Kelly J. Navigating self-management. Available at www.megpn.com.au/Docs/ChronicIllness/GoodLifeClub/NavigatingSelfManagement.pdf. accessed 20 February 2011.

46 Alleviating the burden of chronic conditions in New Zealand (The ABCC NZ Study). Available at http://dhbrf.hrc.govt.nz/media/documents_abcc/Final_Draft_ABCc_Disease_Specific_report_15.10.09.pdf accessed 20 February 2011.

Australian Disease Management Association. www.adma.org.au

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. www.aihw.gov.au

Australian Resource Centre for Hospital Innovations. www.archi.net.au

Australian Vascular Biology Society. www.avbs.org

Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. www.csanz.edu.au

Cardiomyopathy Association of Australia. www.cmaa.org.au

Case Management Society of Australia. www.cmsa.org.au

Chronic Care for Aboriginal People Program. www.health.nsw.gov.au/initiatives/chronic_care/aboriginal/index.asp

Diabetes Australia. www.diabetesaustralia.com.au

Diabetes New Zealand. www.diabetes.org.nz

Heart Support Australia. www.heartnet.org.au

International Disease Management Alliance. www.dmalliance.org

Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. www.jdrf.org.au

Māori Health. www.maorihealth.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexma/home

National Heart Foundation of Australia. www.heartfoundation.com.au

National Heart Foundation of New Zealand. www.heartfoundation.org.nz

New Zealand Guidelines Group. www.nzgg.org.nz

New Zealand Ministry of Health. www.health.govt.nz