Testing of Infants, Toddlers, and Preschool Children*

Manual muscle testing of infants and children traditionally has posed problems to pediatric practitioners because of validity issues. These problems stem from the child’s inability to understand the evaluator’s instructions as well as potential confounding of the results via evaluator handling. Trends in early intervention and pediatric rehabilitation focus on evaluating and treating infants and children in their natural environments (e.g., home, classroom, playground, preschool).1,2 Services in natural environments are consistent with motor learning principles: the need to consider the characteristics of the person, the nature of the task, and the structure of the environment.3 Performance is defined as what a person “does do” in the usual circumstances of his or her everyday life, and capability is defined as what a person “can do” in a defined situation apart from real life.4,5 Assessing motor function in a controlled clinical setting provides information regarding what the child is capable of doing but does not account for environmental factors that may influence the performance of the skill.4 In addition, standardized tests that are administered in a controlled environment may measure what a child can do in that particular setting but may have limited correlation to everyday performance.6 The person-environment interaction is a dynamic process that needs to be understood when evaluating, setting treatment goals, and interpreting outcomes for infants and children.5,7 The clinician, therefore, must determine what is to be assessed—capability or performance. Although it is recommended that both performance and capability be measured, it may not be practical for a clinician to evaluate infants and children in their natural setting.4 Parents’ reports have been shown to provide qualitative, reliable, and valid information regarding the usual performance of their children within their natural environment.8 The use of a natural environment supports the clinician in providing family-centered care by recognizing that family members and care providers are the primary influences in their infant or child’s growth and development.

This focus on the natural environment also encourages therapists to rely on their observation skills and their ability to engage infants and children in age-appropriate behaviors, thereby refraining from excessive handling of the infant or toddler during the evaluation process.9

It requires that therapists possess a mature understanding of developmental milestones, as these milestones provide a framework for understanding the behaviors of infants and children. This chapter was designed to provide clinicians with a means to analyze muscle function associated with the classic gross and fine motor developmental milestones observed during infancy and early childhood. In using this approach, physical therapists will be able to provide other members of pediatric care teams with functionally relevant data. These data will form the basis for establishing developmental treatment goals and outcomes desired by clinicians and educators alike.

This chapter is designed to be compatible with developmental assessments commonly used in a wide range of pediatric clinics (Alberta Infant Motor Scale9; Revised Gessell and Amatruda Developmental Neurological Examination10; Bayley Scales of Infant Development II11; Peabody Developmental Motor Scales12). Chapter contents will assist physical therapists who work with children to analyze their clients’ muscle function in the context of those clients’ developmental assessment. It provides clinicians with a checklist of the major muscle groups associated with each particular posture or movement. These movements are complex, and the analysis of muscle function associated with each posture or movement is not exhaustive. By using the information provided, however, clinicians will be able to detect when aberrant muscle function is a contributory factor to the infant or child’s atypical posture or movement, and may be altering an appropriate developmental progression.

Each posture or movement analyzed in the chapter is observed commonly in the pediatric population. The age range presented for each posture and movement is based on chronological age (age since the individual’s birth date). Therapists are reminded to calculate a corrected age when evaluating an infant or toddler born prematurely. Infants born before 37 weeks of gestation are considered premature.13 A corrected age is calculated by subtracting the number of weeks of gestation from 40 and then subtracting this number from the chronological age. We recommend calculating a corrected age until the chronological age of 24 months. The age range presented with each posture or movement in the infant section was adapted from Piper and Darrah.9 With each movement, a normal muscle activity pattern is listed. An analysis of functional activities associated with each movement is provided to relate both evaluation and interventions to functional outcomes. Also provided is a brief discourse on the spectrum of muscle activity associated with each posture and movement to address the transitional processes that infants and children may use in progressing to the next milestone. These last two sections were included to help in establishing goals and treatment planning.

We recognize that the approach taken in this chapter is not the traditional one used in evaluating strength in children. Therefore we have provided three case studies as examples using the information presented in this chapter. These cases exemplify a physical therapy evaluation occurring in a natural setting for each child. In each case, a grading scale has been used to measure the child’s functional performance on particular milestones. The grading system is used to illustrate that while aberrant muscle function may be present, functional participation in the child’s natural environment is possible. It also must be noted that while a child may be able to perform all developmental milestones up to his or her highest ability level, it is not necessary to facilitate or observe each milestone. Many muscle synergies are demonstrated at several levels of performance. The child or the child-parent dyad must determine the direction of the assessment with appropriate suggestions and minimal manual facilitation by the therapist to determine the child’s highest performance level. During assessment of the child, the therapist should note the movements being observed and document the presence or absence of individual muscle activity. We do not suggest providing resistance until later in childhood, when traditional manual muscle testing can be employed. For example, if a child more than 5 years of age is acutely ill and muscle function data are needed, then the clinician should use the same types of muscle tests as those described for the adult population. After observing the child in a number of developmentally appropriate movements, the therapist will analyze the results of muscle activity and determine a pattern of muscle strengths and weaknesses that can be used to develop specific interventions.

This chapter is designed to produce material that is useful to experienced and novice pediatric physical therapists, and to students interested in working with infants and children. We hope it helps physical therapists become more proficient in analyzing muscle activity patterns of infants and children, and that by using this type of muscle assessment, physical therapists can make valuable contributions to pediatric teams caring for children with disabilities.

The necessity to write reports in a client’s chart and to compare results over different periods of time has led to the grading scale described below.

| Description | Grade1,2,9–13 |

| Functional (F) | Normal for age or only slight impairment or delay |

| Weak functional (WF) | Moderate impairment or delay that affects activity pattern, base of support, or control against gravity, or decreases functional exploration |

| Nonfunctional (NF) | Severe impairment or delay; activity pattern has only elements of correct muscular activity |

| No function (0) | Cannot do activity |

INFANTS: 0-12 MONTHS

Activity: “Swimming” (19-32 weeks)

Functional Activity: Elevation of visual perspective. Preparation for higher levels of antigravity mobility.

Spectrum of Muscle Function: In this position the child is using all extensor musculature against gravity. The head and upper chest are elevated; scapulae are retracted (Figure 6-1). Elevating the lower extremities may activate the gluteal muscles. The child may rock back and forth, but there is no forward motion.

FIGURE 6-1

Activity: Rolling Prone to Supine with Rotation (28-36 weeks)

Active rotation against gravity of head, shoulder, or pelvis

Concentric contraction of neck rotators

Concentric contraction of ipsilateral rhomboids (those participating in initiating the rolling activity)

Concentric contraction of ipsilateral obliques (those participating in initiating the rolling activity)

Concentric contraction of hip flexors and abductors (those participating in initiating the rolling activity)

In Figure 6-2 the child is rolling to the left; therefore a concentric contraction of the left rhomboids, obliques, hip flexors, and abductors would be observed.

Activity: Reciprocal Crawling (30-37 weeks)

Base of Support: Elbow, forearm, and opposite leg. Fingers extended, palms on the ground. Abdomen resting on the ground (Figure 6-3).

FIGURE 6-3

Activity: Modified Four-Point Kneeling (34-46 weeks)

Base of Support: Weight bearing on hands, one foot, and opposite knee (Figure 6-4). Base of support is widened from quadruped.

FIGURE 6-4

Head neutral or concentric contraction of neck extensors for increased upward gaze

Shoulders flexed, scapulae protracted

Hip flexed at or past 90° with concordant knee flexion

Opposite hip flexed at or past 90° with external rotation, 90° or less of knee flexion, foot on the floor. Foot may be slightly plantar-flexed for greater stability

Functional Activity: Modified quadruped position affords the child increased opportunities for exploration via a widened base of support to obtain or manipulate objects. Figure 6-4 demonstrates three-point kneeling in which the child has weight-shifted laterally and posteriorly to obtain a toy. This is an example of increased ability to manage the center of gravity, against the force of gravity, over the base of support while in an elevated position.

Activity: Reciprocal Creeping (34-44 weeks)

Base of Support: Alternating weight bearing of opposite hand and knee. Abdomen is raised from the surface.

Functional Activity: Increased mobility in the quadruped position. Affords the child the ability to obtain an object with increased speed and efficiency versus crawling.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Mature representation of creeping is presented with a neutral spine and limb placement directly underneath the respective girdles, narrowing the base of support. Child’s management of body mass against gravity is much improved. Immature presentation shows increased lumbar lordosis and abduction of the limbs, lowering the center of gravity and widening the base of support (Figure 6-5).

FIGURE 6-5

POSITION: SUPINE

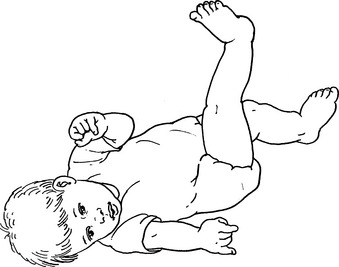

Activity: Hands to Feet (18-24 weeks)

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, child may only approximate feet and hands. With increased strength, the child may bring the feet to the mouth with either muscular contraction of the hip flexors against gravity or use of hands (Figure 6-6). The pelvis may tilt posteriorly, indicating increased abdominal strength. The head also may be raised toward the feet.

FIGURE 6-6

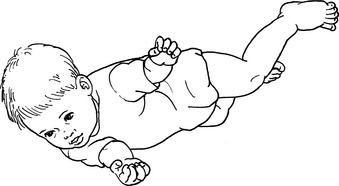

Activity: Rolling Supine to Prone with Rotation (25-36 weeks)

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Selective muscle control as seen with dissociation of the trunk and hips. The child may lead with head, arm, and shoulder, or with leg and pelvis (see Figure 6-7, B).

FIGURE 6-7, B

POSITION: SITTING

Activity: Sitting with Propped Arms (10-25 weeks)

Functional Activity: This posture allows for perception of the environment at an elevated perspective, object acquisition, and play.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Spine generally kyphotic, indicating lack of general back extensor strength. Hips flexed and externally rotated to widen base of support. Knees flexed with the feet between buttocks and hands for additional support (Figure 6-9). As muscular strength increases, the child is able to maintain spine erect against gravity, with the assistance of upper extremities, and he or she may move outside of base of support to reach for objects.

FIGURE 6-9

Activity: Sitting without Arm Support-Unsustained (21-27 weeks)

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, the child will make adjustments as he or she tries to maintain the center of gravity over the base of support. This results because the child has yet to achieve mature muscle control patterns. Legs are abducted and externally rotated for widened base of support. Increased maturity is seen via decreased kyphosis of the spine, by the child’s willingness to move arms within the base of support, and also by the child decreasing the width of the base of support (Figure 6-10).

FIGURE 6-10

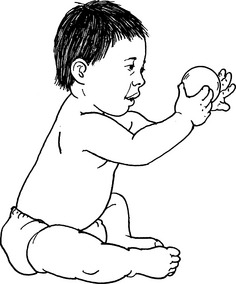

Activity: Dynamic Sitting without Arm Support—Sustained (25-32 weeks)

Functional Activity: Erect sitting with balance and stability to obtain and manipulate objects. Attention to the task of sitting is decreased, affording the child the ability to give increased attention to the environment outside of his or her immediate surroundings.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Increased maturity is seen via (a) decreased base of support as one or both legs may be extended with continued maintenance of erect posture against gravity; (b) increased movement of the arms and legs both inside and outside the base of support; and (c) rotation of the trunk while reaching. The child is able to lean forward outside the base of support and manage the center of gravity as the arms are lifted to obtain a toy (Figure 6-11).

FIGURE 6-11

POSITION: STANDING

Activity: Supported Standing (18-30 weeks)

Functional Activity: This is a preindependent standing activity that develops strength and balance and provides the child with the experience of standing.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, the child will require support at chest level while bearing weight (Figure 6-12). The child may bounce up and down with active control and flexion/extension of the trunk. As the child becomes more experienced, he or she will be able to use a support surface while maintaining a standing position.

FIGURE 6-12

Activity: Pulls to Stand, Stands with Support (32-40 weeks)

Base of Support: Weight bearing through feet. Balance and stability with hands on the support surface or adult assistance (Figure 6-13 A).

FIGURE 6-13, A

Concentric contraction of shoulder flexors (reaching for support surface)

Concentric contraction of shoulder extensors (pulling to stand)

Shoulder stabilization while moving to stand

Concentric contraction of transition limb hip flexor

Isometric contraction of contralateral hip abductor

Concentric contraction of bilateral quadriceps as full stand is achieved

Functional Activity: This skill allows for the acquisition of objects and environmental exploration higher than floor level. This provides the initial experience of transitioning from floor to stand.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, the child may require assistance when moving to the standing position. The adult is able to control the child’s inability to manage the increased number of degrees of freedom during the transition to stand. As the child matures, he or she is able to control the center of gravity over the base of support, against gravity, and use the support surface to move to stand. Once stance is acquired, the base of support is generally widened with the legs externally rotated (Figure 6-13 B).

FIGURE 6-13, B

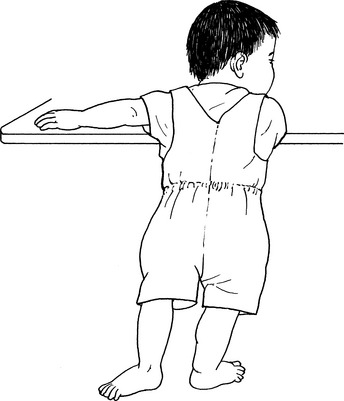

Activity: Side-Step Cruising (36-56 weeks)

Base of Support: Weight bearing through alternating double- and single-limb support with weight shifting. Some weight bearing is seen through the arms on the support surface (Figure 6-14).

FIGURE 6-14

Isometric contraction of shoulder extensors during single-limb support

Trunk co-contraction and stabilization

Concentric contraction of swing limb abductors

Eccentric contraction of stance limb adductors

Isometric co-contraction of weight-bearing limb flexors and extensors

Concentric contraction of plantar flexors of the foot for stability as weight is transferred

Activity: Controlled Lowering with Support (36-45 weeks)

Functional Activity: Use of a support surface affords the child the ability to transition from an upright position to the floor safely. This also provides the opportunity for the child to reach and acquire objects on the floor for manipulation or to transfer them to the surface of the support at which he or she is standing.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: As the child moves downward, he or she may move to a half-kneel position for increased stability as he or she addresses or manipulates objects that are on the floor (Figure 6-15). This transition is the first in which the child must manage his or her entire mass in the direction of gravity with eccentric control.

FIGURE 6-15

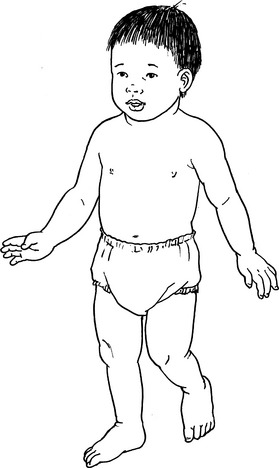

Activity: Stands without Support (42-56 weeks)

Base of Support: Weight bearing on feet. Hips are abducted and externally rotated for increased base of support.

Functional Activity: Preparation for independent walking. Support surface not required; thus the environment has a decreased impact on the child’s mobility.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Child initially is generally hyperlordotic; arms may be at high or medium guard during initial stages. As the child becomes more stable, arms and hands will lower and may be used to manipulate objects; base of support narrows; legs become less externally rotated (Figure 6-16).

FIGURE 6-16

Activity: Stands from Modified Squat (46-60 weeks)

Functional Activity: Child has the ability to reach for objects on the ground and transfer them to an alternative location without using a support surface; thus environmental restrictions have less impact (Figure 6-17).

FIGURE 6-17

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, the child may present with increased lumbar lordosis; the base of support is widened with external rotation of the hips. As the child moves to a standing position, the increased lumbar lordosis may result in plantar flexion in an attempt to manage the center of gravity over the base of support.

Activity: Walks Alone (46-57 weeks)

Functional Activity: Independent physical access to the environment increases the child’s ability to explore and obtain objects from the surrounding environment.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity: Initially, the child has a widened base of support. External rotation at the hip. Arms at high guard for increased balance and protective readiness. As the child becomes more efficient, the base of support will narrow; external rotation of the legs will decrease; the arms will move down from high guard, affording the child the ability to acquire objects in the environment (Figure 6-18).

FIGURE 6-18

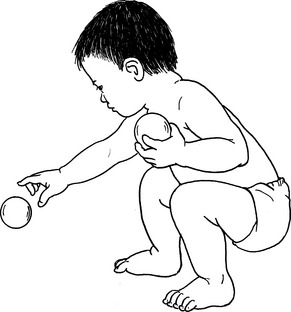

Activity: Squatting (52-59 weeks)

Functional Activity: The child is able to move easily from a standing position to obtain objects from the floor and stand again without using a support surface (Figure 6-19).

FIGURE 6-19

TODDLERS AND PRESCHOOL CHILDREN: 1-5 YEARS

Activity: Low Kneel to High Kneel (15 months-2 years)

Base of Support

Dorsal aspect of both feet (Figure 6-20, A). Anterior aspect of lower legs (Figure 6-20, B).

FIGURE 6-20, A

FIGURE 6-20, B

Functional Activity

Reaching for an object from floor to alternative level. Preparation to move to a standing position.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Child may initially use a support surface or place hands on the floor to stabilize trunk and compensate for inadequate strength of gluteals and quadriceps. In the low-kneel position the child’s legs may initially be abducted and internally rotated with the feet lateral to the knees. With growth and increased strength, the child is able to move the body mass against gravity and maintain position without a surface support and then can transition through the spectrum from low kneel to high kneel and finally to half-kneel.

Activity: High Kneel to Half-Kneel (18-27 months)

Functional Activity

Preparation for moving to a standing position from the floor. Head is maintained in the frontal plane.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

The child may initially lean to the contralateral side of the moving limb and place a hand on the floor for support, or may reach for a support surface as the moving leg is brought into position. The moving limb may also be abducted and the medial surface of the foot may remain in contact with the floor as it is moved (Figure 6-20, C). Mature representation reflects maintenance of a level pelvis in the transverse plane. The moving limb is maintained in a fairly consistent sagittal plane.

FIGURE 6-20, C

Children move through the spectrum from low kneel to high kneel to half-kneel as they mature.

Activity: Side Step (18-30 months)

Weight bearing on both feet with intermittent bouts of single-limb support. Center of gravity maintenance over base of support in the frontal plane (Figure 6-21).

FIGURE 6-21

Muscle Activity Pattern

Co-contraction of back extensors and abdominals for maintenance of erect trunk

Co-contraction of stance limb hip flexors and extensors

Isometric contraction of gluteals

Isometric contraction of stance limb abductors to maintain level pelvis

Concentric contraction of swing limb abductors

Eccentric contraction of stance limb adductors

Weight shift and weight acceptance onto swing limb

Isometric contraction of abductors of new stance limb

Functional Activity

Increases child’s maneuverability around and through obstacles in the environment. Increased single-limb stance period.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

As the child becomes more proficient, side-step length will increase and will progress from frontal plane movement to associated diagonal planes. Figure 6-21 depicts a child demonstrating a mature representation of a side step.

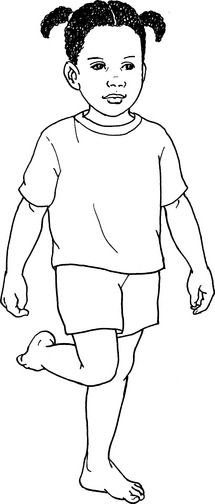

Activity: Standing on One Foot (2½-3½ years)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Co-contraction of back extensors and abdominals for maintenance of erect trunk

Isometric contraction of quadriceps to maintain locked knee

Isometric contraction of stance limb abductors

To account for anterior-posterior sway, transitions between concentric and isometric co-contractions of anterior and posterior compartment muscles are observed

To account for sagittal sway, transitions between concentric and isometric co-contractions of the foot invertors and evertors are observed

Concentric contraction of hamstrings in non–weight-bearing limb to lift foot

To maintain posture, a transition between concentric and isometric contractions of non–weight-bearing limb abductors is observed

Functional Activity

Development and increase of static and dynamic balance skills for higher-level play activities.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

As seen in Figure 6-22, A, a toddler may initiate brief periods of single-limb stance. Initially, the child may wrap the non–weight-bearing limb around the stance limb. The arms may be held out from the body for balance. The pelvis may tilt to the non–weight-bearing side secondary to decreased strength of abductors and movement of the center of gravity closer to the support limb. The toddler will present with increased sway. As the child becomes older and more proficient, arms will be maintained at sides of the body and pelvis symmetry is maintained (Figure 6-22, B).

FIGURE 6-22, A

FIGURE 6-22, B

Activity: Jumping from Two Feet (3-4 years)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Preparation Phase (Figure 6-23, A)

FIGURE 6-23, A

Concentric hip and knee flexion

Eccentric contraction of hip extensors and ankle plantar flexors

Action Phase (Figure 6-23, B)

FIGURE 6-23, B

Concentric gluteal contraction

Functional Activity

This activity allows for a rehearsal of a higher level of gross motor play skills and an increased management of center of gravity.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

As the child becomes more proficient, greater hip and knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion are observed secondary to a desire for increased force production. As the child matures, an increased proficiency at managing the center of gravity over the base of support facilitates an increase in force production.

Activity: Jumping off a Step (3-4 years)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Action Phase (Figure 6-24, A)

FIGURE 6-24, A

Concentric hip and knee extension

Concentric contraction of back extensors

Landing Phase (Figure 6-24, B)

FIGURE 6-24, B

Eccentric contraction of hip extensors

Functional Activity

This allows for a rehearsal of a higher level of gross motor play skills and an increased management of center of gravity.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

As the child becomes more proficient, greater hip and knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion are observed secondary to desire for increased force production (see Figure 6-24, B).

Activity: Toe-Walking (3-4 years)

Functional Activity

This allows for a rehearsal of a higher level of gross motor play skills and an increased management of center of gravity.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Initially, the child may hold arms out to sides for balance. There also may be a drop in the heel as weight is accepted. As the child’s strength develops, the center of gravity is maintained over the metatarsophalangeal joints, step length may increase, and the medial and lateral muscles of the lower limb will play an increasing role in stabilization.

Activity: Heel-Walking (4-5 years)

Functional Activity

This allows for a rehearsal of a higher level of gross motor play skills and an increased management of center of gravity.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Initially, the toes may be raised only slightly from the floor; the base of support will be wide with increased trunk flexion and use of arms as balance. As the child’s strength increases, toes are lifted and maintained a maximal distance from the floor (Figure 6-26).

FIGURE 6-26

Activity: Tandem-Walking (5+ years)

Functional Activity

This allows for a rehearsal of a higher level of gross motor play skills and an increased management of center of gravity.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

The child may initially place the swing foot slightly in front of the stance foot (Figure 6-27), moving it posteriorly into the appropriate position only after stance has been initiated. Increased trunk sway for balance maintenance is seen, as well as arms positioned away from body.

FIGURE 6-27

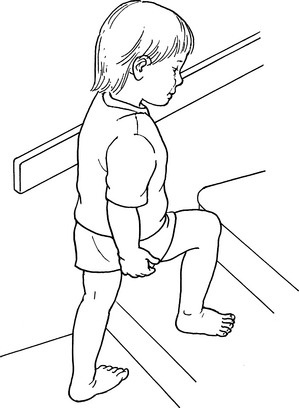

Activity: Stair-Walking-Upstairs (24-29 months)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Concentric contraction of abdominals

Isometric stabilization of back extensors

Concentric contraction of swing limb hip flexors

Concentric contraction of swing foot dorsiflexors

Isometric stabilization of stance limb abductors

Isometric contraction of stance limb gluteals

Concentric contraction of swing limb quadriceps as weight is accepted

Concentric contraction of stance limb ankle plantar flexors

Concentric contraction of swing limb gluteals as increased weight is transferred

Functional Activity

Transitioning between ground and higher levels: for use in homes, apartments, and schools, and with playground equipment.

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Initially, the child may use the rail or adult support. As the leg is brought to the upper step, a lateral trunk lean to the opposite side may be seen. As the child matures, weight will be maintained over the stance limb with forward trunk lean as ascension begins (Figure 6-28).

FIGURE 6-28

Activity: Stair-Walking-Downstairs (36-41 months)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Isometric contraction of gluteals

Concentric contraction of swing limb hip flexors

Concentric contraction of swing limb abductors

Eccentric contraction of stance limb quadriceps

Isometric contraction of stance limb abductors

Eccentric contraction of swing limb plantar flexors as weight is accepted

Concentric contraction of swing limb abductors as full weight is accepted

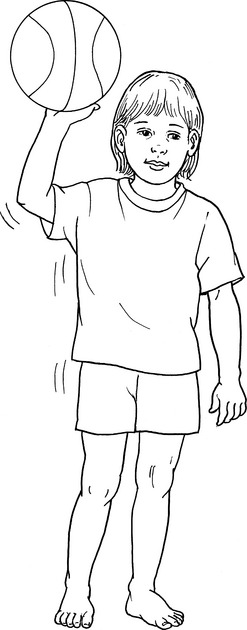

Activity: Ball Throwing-Overhead (2-4 years)

Muscle Activity Pattern

Bilateral concentric shoulder flexion

Isometric shoulder horizontal adduction

Bilateral concentric elbow flexion

Isometric co-contraction of abdominals and back extensors

Bilateral concentric shoulder extension

Bilateral concentric elbow extension

Transfer of weight from heels to balls of the feet as ball passes over the head

Concentric abdominal contraction

Bilateral concentric contractions of wrist flexors that result in ulnar deviation

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Feet may be side by side, staggered, or increased weight bearing on the dominant foot (Figure 6-29, A). As the child becomes more proficient, movement can be more forceful and ballistic and you may begin to see ulnar deviation (Figure 6-29, B).

FIGURE 6-29, A

FIGURE 6-29, B

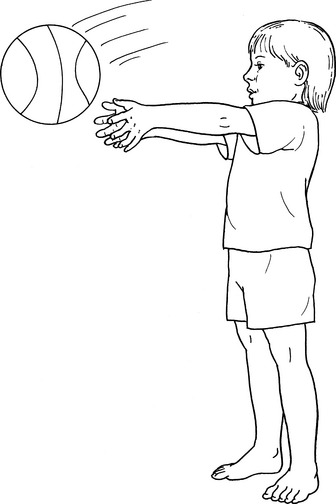

Activity: Ball Throwing-One-Handed (43-53 months)

Plantar aspects of feet bilaterally. Foot on throwing side slightly posterior. Weight is transferred from posterior foot to anterior foot with follow-through (Figure 6-30).

FIGURE 6-30

Muscle Activity Pattern

Concentric contraction of hand intrinsics for gripping ball

Isometric contraction of rotator cuff musculature for shoulder stabilization

Concentric contraction of biceps

Concentric contraction of shoulder flexors

Posterior trunk rotation toward throwing arm

Spectrum of Muscle Activity

Initially, the child stands with feet side by side; the base of support is widened. There is little or no trunk rotation. At toddler age, the arm is drawn upward with little or no elbow flexion. During the action phase, the arm remains extended, with no wrist flexion. Trunk flexion may be seen as the ball is thrown. As the child’s proficiency increases with age, weight is borne on the throwing side limb and then transferred to the contralateral limb as the ball is thrown forward.

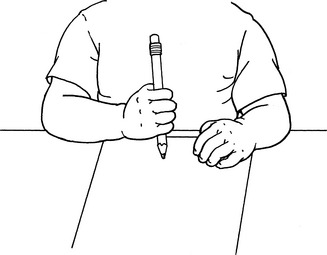

Activity: Prehension—Palmar Supinate (12-18 months)

Writing implement is held in a fisted hand; the wrist is slightly flexed and the forearm is supinated from midposition (Figure 6-31).

FIGURE 6-31

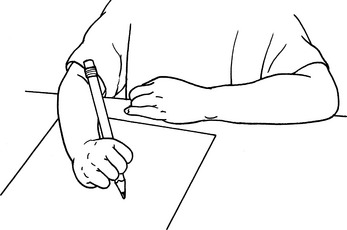

Activity: Prehension—Digital Pronate (2-3 years)

Writing implement is held with fingers. Wrist is ulnarly deviated and slightly extended; forearm is slightly pronated (Figure 6-32).

FIGURE 6-32

Activity: Static Tripod (3½-4 years)

Activity: Dynamic Tripod (4½-6 years)

The writing implement is held distally with precise opposition of distal phalanges of thumb and index and middle fingers. Ring and little fingers are flexed fully to form a stable support structure (Figure 6-33). The wrist is slightly extended. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are stabilized during fine, localized movement of the proximal interphalangeal joints.

FIGURE 6-33

REFERENCES

1. Neisworth, JT, Bagnato, SJ. Assessment in early childhood special education. A typology of dependent measures. In: Odom SL, Karnes MB, eds. Early Intervention for Infants and Children with Handicaps: An Empirical Base. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes, 1988.

2. Hanft, BE, Pilkington, KO. Therapy in natural environments: The means of end goal for early intervention. Infants Young Child. 2000;12:1–13.

3. Shumway-Cook, A, Woollacott, MH. Motor Control. Theory and Practical Applications, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

4. Young, NL, Williams, JI, Yoshida, KK, Bombardier, C, Wright, JG. The context of measuring disability: Does it matter whether capability or performance is measured? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1097–1101.

5. Haley, SM, Coster, WJ, Binda-Sundberg, K. Measuring physical disablement: The contextual challenge. Phys Ther. 1994;74:443–451.

6. Tieman, BL, Palisano, RJ, Gracely, EJ, Rosenbaum, PL. Gross motor capability and performance of mobility in children with cerebral palsy: A comparison across home, school, and outdoors/community settings. Phys Ther. 2004;84:419–429.

7. Palisano, RJ, Tieman, BL, Walter, SD, Bartlett, DJ, Rosenbaum, PL, Russell, D, Hanna, SE. Effect of environmental setting on mobility methods of children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:113–120.

8. Wilson, BN, Kaplan, BJ, Crawford, SG, Campbell, A, Dewey, D. Reliability and validity of a parent questionnaire on childhood motor skills. Am J Occup Ther. 2000;54:484–493.

9. Piper, MC, Darrah, J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994.

10. Knobloch H, Pasamanick B. Revised Gesell and Amatruda Developmental Neurological Examination, 1974.

11. Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace, 1993.

12. Folio, M, Fewell, R. Peabody Developmental Scales. Allen, Tex: DLM Teaching Resources, 1983.

13. Evans, HE, Glass, L. Perinatal Medicine. Hagerstown, Md: Harper & Row, 1976.