Chapter Nineteen Breasts and regional lymphatics

ANATOMY

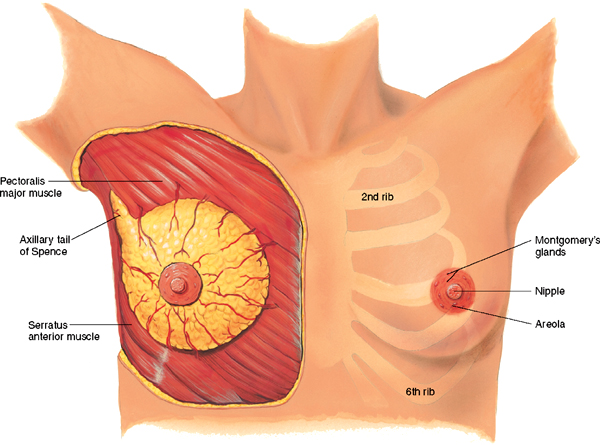

The breasts lie anterior to the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles, between the second and sixth ribs. The upper outer corner of breast tissue, called the axillary tail of Spence, projects up and laterally into the axilla.

Externally, the nipple is just below the centre of the breast. It is rough, round and usually protuberant; its surface looks wrinkled and indented with tiny milk duct openings. The areola surrounds the nipple for a 1 to 2 cm radius. In the areola are small elevated sebaceous glands, called Montgomery’s glands. These secrete a protective lipid material during lactation. The areola also has smooth muscle fibres that cause nipple erection when stimulated (Fig 19.1).

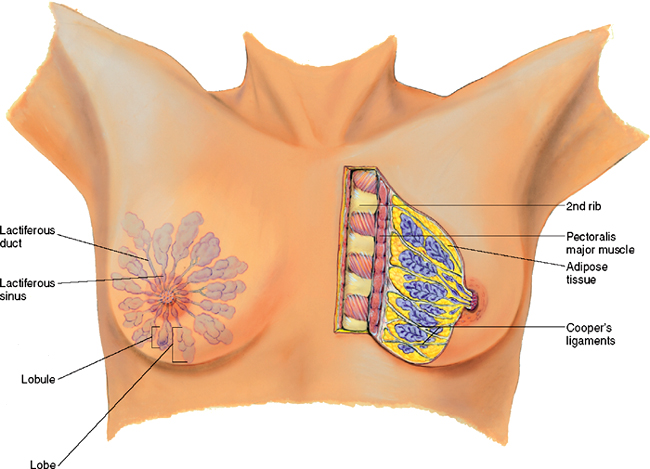

The male breast is a rudimentary structure consisting of a thin disk of undeveloped tissue underlying the nipple. The female breast is composed of (1) glandular tissue, containing 15 to 20 lobes radiating from the nipple, which are composed of lobules (clusters of alveoli that produce milk), which empty into a lactiferous ducts converging toward the nipple; (2) the suspensory ligaments, or Cooper’s ligaments, are fibrous bands extending vertically from the surface to the chest wall muscles supporting the breast and (3) the adipose, or fatty tissue which provides most of the bulk of the breast (Fig 19.2). The relative proportion of glandular, fibrous and fatty tissue varies depending on age, menstrual cycle, pregnancy, lactation and general nutritional state.

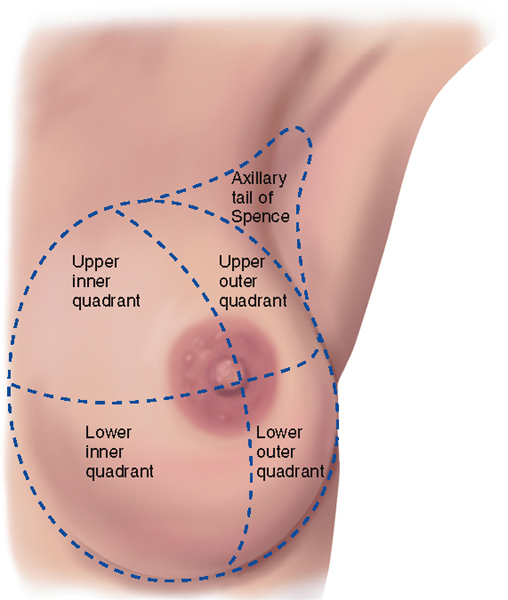

The breast may be divided into four quadrants by imaginary horizontal and vertical lines intersecting at the nipple. This makes a convenient map to describe clinical findings: upper outer, lower outer, lower inner and upper inner quadrants (Fig 19.3).

LYMPHATICS

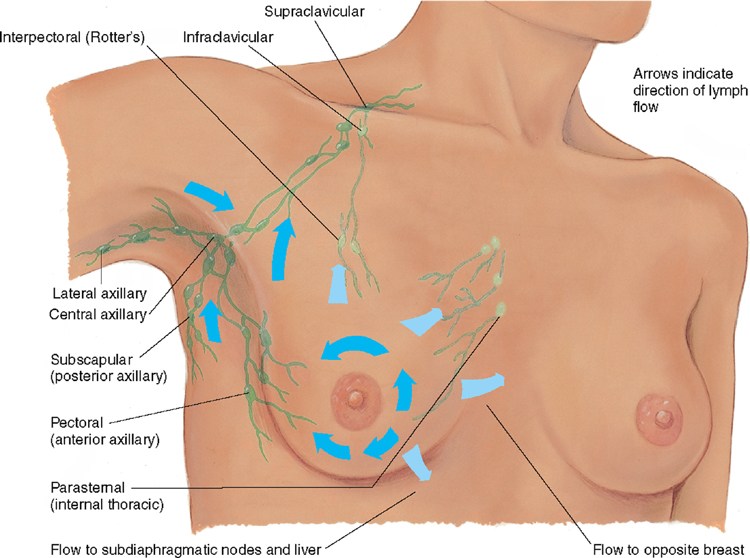

The breast has an extensive lymphatic drainage system comprised of: (1) central axillary nodes high up in the middle of the axillae that receive lymph from the three other groups of axillary nodes; (2) pectoral nodes along the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle; (3) subscapular nodes along the lateral edge of the scapula and (4) lateral nodes along the humerus, inside the upper arm. From the central axillary nodes, drainage flows up to the infraclavicular and supraclavicular nodes (Fig 19.4).

DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

The adolescent

During adolescence, it is common for the male’s breast tissue to temporarily enlarge, producing gynaecomastia. This condition is usually unilateral and temporary. Reassurance is necessary for the adolescent male, whose attention is riveted on his body image.

At puberty the oestrogen hormones stimulate breast changes in the female. The breasts enlarge, mostly as a result of extensive fat deposition. The duct system also grows and branches and masses of small, solid cells develop at the duct endings. These are potential alveoli.

Ethnicity and genetic correlates of race appear to be important factors affecting the onset of puberty (Butts and Seifer, 2010). Occasionally, one breast may grow faster than the other, producing a temporary asymmetry. This may cause some distress; reassurance is necessary. Tenderness is also common due the influence of reproductive hormones, particularly oestrogen.

The pregnant female

During pregnancy, breast changes start during the second month. Pregnancy stimulates the expansion of the ductal system and supporting fatty tissue as well as development of the true secretory alveoli. Thus the breasts enlarge and feel more nodular. The nipples are larger, darker and more erectile. The areolae become larger and grow a darker brown as pregnancy progresses. After the fourth month, colostrum may be expressed. This thick yellow fluid is the precursor for milk. The breasts produce colostrum for the first few days after delivery. It is rich with antibodies that protect the newborn against infection. Milk production (lactation) begins 1 to 3 days postpartum.

Late adulthood (65+ years)

Gynaecomastia may reappear in the male over 65 years and may be due to testosterone deficiency.

After menopause, the female’s ovarian secretion of oestrogen and progesterone decreases, which causes the breast glandular tissue to atrophy. This is replaced with fibrous connective tissue. These changes decrease breast size and elasticity so the breasts droop and sag. The decreased breast size makes inner structures more prominent. A breast lump may have been present for years but is suddenly palpable.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Breast cancer is the most common cancer that occurs in Australian and New Zealand women. The risk of developing breast cancer to age 85 years is 1 in 9 for Australian women and 1 in 767 Australian men (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008). There are similar rates of breast cancer in New Zealand (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2009).

The incidence of breast cancer varies with different cultural groups. Although the incidence of breast cancer is significantly lower in Indigenous Australian women than in non-Indigenous Australian women; Indigenous Australian women have significantly lower 5-year crude survival rates (65% and 82% crude survival, respectively) (AIHW and National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre (NBOCC*), 2009). In New Zealand, although breast cancer occurs with equal frequency in Māori and non-Māori women, Māori women are nearly twice as likely to die from the disease as non-Māori women, mainly because they tend to present with late stage breast cancer at the time of diagnosis (Cancer Control Council of NZ, 2008).

Breast checks

Breast checks are about women taking the time to get to know the normal look and feel of their breasts. Technique of checking is not important. Knowing what is normal will help detect any changes for investigation. Women can be educated to undertake breast checks during routine daily activities such as showering, dressing, putting on body lotion or simply looking in the mirror. Nine out of 10 breast changes are not due to cancer, but should be investigated. (See http://www.nbocc.org.au/breast-cancer/awareness/).

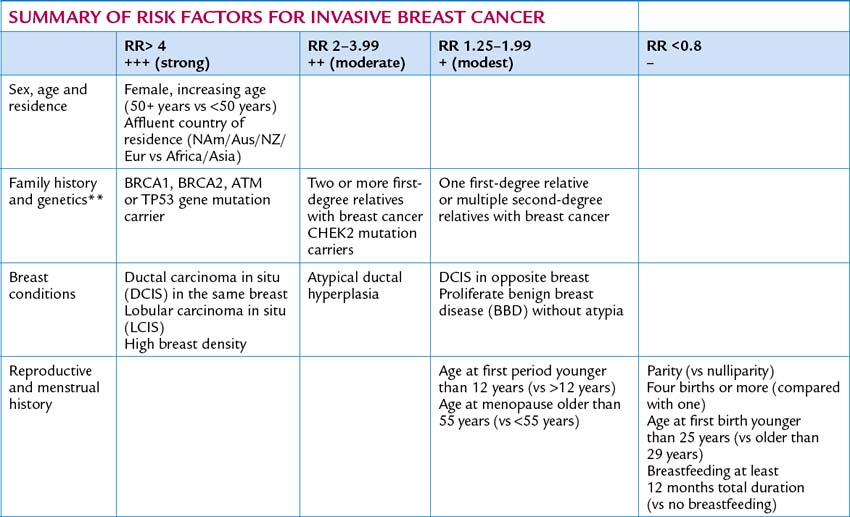

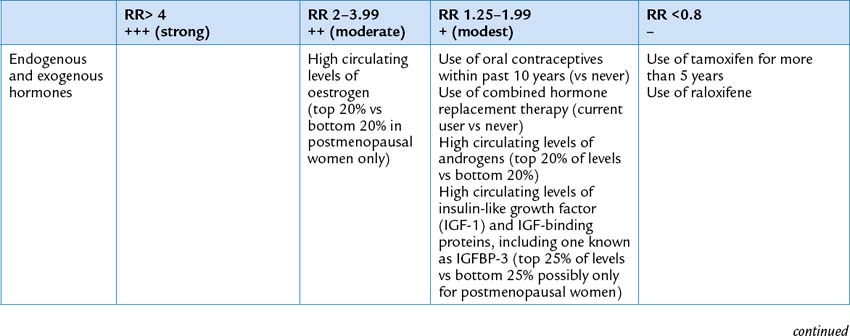

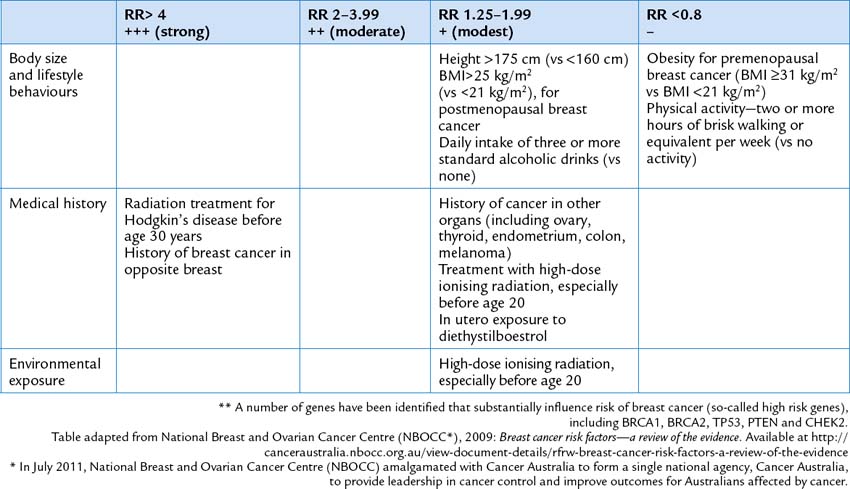

Cancer Australia’s guide about risk factors for breast cancer provides a review of epidemiological studies about risk factors for breast cancer. The risk factors are graded according to their relative risk (RR). Modest RR factors are graded between 1.25 and 1.99. Moderate RR are graded as 2.00–3.99. Strong RR is graded as 4+ and factors which are potentially protective as RR<0.8 (NBOCC*, 2009).

SUBJECTIVE DATA

Because of the physiological relationship between the breasts and lymph glands, any assessment of a woman’s breast must include an assessment of the axillary lymph glands.

OBJECTIVE DATA

| Preparation | Equipment needed |

|---|---|

| The woman is sitting up, facing you. Maintain privacy by only exposing the breasts, axilla and arm upper. During palpation, the woman is supine with her arm positioned above her head; cover one breast with the gown while examining the other. Your examination of the male breast can be much more abbreviated, but do not omit. |