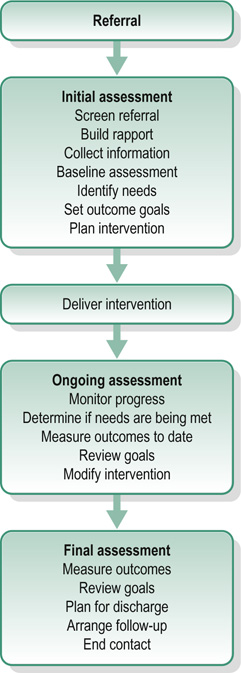

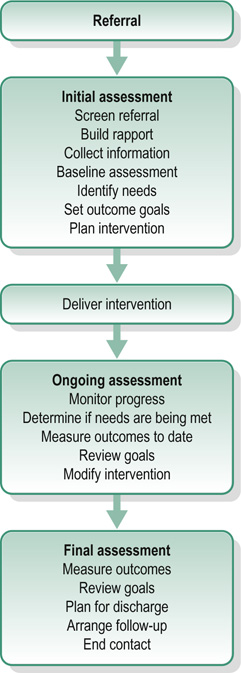

FIGURE 5-1 The assessment and outcome measurement process.

CHAPTER CONTENTS

ASSESSMENT AND OUTCOME MEASUREMENT PROCESS

Stage 2: Ongoing Assessment and Evaluation

Stage 3: Final Assessment (and Outcome Review)

Abilities, Strengths and Interests

Individualized Outcome Measures

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs)

Clinician-Reported/Rated Outcome Measures (CLOMs also ClinROs)

Assessment and outcome measurement are integral parts of the occupational therapy process and commence at the point of referral. (It may be helpful to read this chapter in tandem with the description of the occupational therapy process in Ch. 4.) The occupational therapy process begins with the end in mind (Covey 1989), by thinking about the outcome at the beginning of the process. This means it is clear from the outset what the end-point of therapy is. It also makes it possible to make a judgement about whether the outcome has been achieved and to identify if there has been a change in the person’s situation. Assessment is measurement of the quality or degree of the various factors in a situation or condition. For occupational therapists in clinical practice, assessment is used to measure the strengths and needs of the person that relate to their referral for occupational therapy.

Outcome measurement involves comparing a person’s level of function after intervention with what they were able to do before. Outcomes are the expected or intended results of intervention. The desired outcome is the goal that the individual and therapist want to achieve in their work together. The actual outcome is the measurable result of the intervention. Outcome measurement is the evaluation of the extent to which an outcome goal has been reached (Creek 2003), consequently outcome measures are measures of change over time, therefore before beginning intervention, it is necessary to establish the individual’s current level of functioning. This chapter will discuss the part that assessment and outcome measurement play in the occupational therapy process including the importance of reliability and validity. It will also consider what is assessed, methods of assessment and different approaches to measuring outcomes.

The assessment and outcome measurement process, as shown in Figure 5-1, is an integral part of the occupational therapy process. Assessment and outcome measurement is not something that is ‘done to’ a person. Outcomes are identified collaboratively by the individual and the therapist. Together, they are actively involved in providing information and in interpreting it; they are involved in determining the goals to be attained and expressing them in such a way that they are measurable. During the process of assessment, the therapist’s focus of attention shifts between different aspects of the person’s performance; skills, tasks, activities and occupations (Creek 2003). There may be long-term outcomes or shorter term, i.e. specific, measurable and realistically achievable steps towards meeting an agreed longer-term goal. These steps should be in a form that is readily understood by the individual involved, the therapist and any others involved. The emphasis is on strengths, promoting engagement and goal achievement. Assessment and outcome measurement takes place in three stages; initial assessment; ongoing assessment and evaluation; and final assessment

FIGURE 5-1 The assessment and outcome measurement process.

Initial assessment takes place at the start of the occupational therapy process and can be described as a way of defining the problem to be tackled or identifying the goal to be achieved. It involves collecting and organizing information about the person from a variety of sources in order to identify the challenges they are experiencing, set goals for the outcome and plan interventions effectively. The steps of the initial assessment process described here may not be carried out in the same sequence with every person. The assessment process is shaped by the individual needs and wishes, the context of the intervention, and other constraints. Initial assessments can also be useful for judging whether or not the person will benefit from occupational therapy intervention and rapport building. This is an example of the art and skill of occupational therapy. An occupational therapist may be administering a test but the manner in which they do it will convey their values (respect, empathy, trustworthiness and partnership working) to the person they are working with. This not only supports the assessment process but provides a solid foundation for intervention. No one part of the occupational therapy process is unrelated from the other.

Occupational therapy intervention can only begin when assessment clearly indicates the need for it. The outcome of an initial assessment may be a decision not to provide an occupational therapy intervention. An example of this would be a person whose alcohol use is directly affecting their occupational performance who needs to acknowledge the problem to benefit from intervention. Recording the results of investigations is the starting point for interpretation and, as such, is part of intervention planning. The process of organizing information, which should be carried out as far as possible with the active cooperation of the person concerned to produce a list of problems and strengths, agree on goals of intervention and suggest strategies and methods of intervention. These last two aspects of the occupational therapy process are discussed in detail in Ch. 6, which focuses on planning and implementing interventions.

To monitor change and progress, assessment and evaluation are ongoing. This enables the therapist, working collaboratively to determine if person’s needs are being met, obtain further specific information, modify interventions or review planned outcomes. The frequency of these assessments will depend on the type of service and expected length of the intervention. Reviews can include:

■ A brief ‘sense check’ of intervention and progress towards goals. This should take place at every session to ensure that therapy is proceeding effectively as planned

■ Once an intervention has been implemented, the therapist again assesses an individual’s skills, the effect on tasks and activities and, finally, whether this means that the individual is now better able to perform their usual range of occupations (or desired occupations)

■ Ongoing review, which may involve activities such as: observation and discussion; regular completion of tools such as diaries or Likert scales; and repetition of previous standardized or non-standardized assessments.

This takes place at the end of the intervention. It can be used to:

■ measure against the individual’s life demands to demonstrate whether outcome goals have been reached

■ provide a picture of residual problems

■ plan for appropriate discharge and follow-up

■ identify reasons why no further progress can be made at this time.

It is not possible, or necessary, to learn everything there is to know about a person. An occupational therapist collects and organizes information about the person, working within the context of the referral, the nature of the service offered and the frame of reference being used by the therapist. This section will focus on the occupational therapist’s domains of concern; namely occupations, routines and habits, abilities, strengths and interests, roles, volition and motivation, aspirations and expectations, areas of dysfunction, external factors and risk.

It is useful to take an occupational history. This is to assess whether the individual’s roles and occupations have been disrupted or whether they have developed supportive and helpful habits and routines. Occupations are enacted through activities; for example, the occupation of mothering is expressed through such activities as bathing her child, feeding her child, playing with her child, reading to her child and answering her child’s questions. The therapist will seek to discover what activities the individual normally performs and whether or not these activities support a healthy range of occupations, and equally whether they are supportive of roles that enable the person to feel like they fit or belong in the wider context/world around them.

Occupations exist in a balance that changes throughout the life cycle. A healthy balance is one that allows most of the individual’s needs to be satisfied in ways that promote social inclusion and integration. This balance can be disrupted by illness or disability but, equally, an inability to participate in a range of chosen occupations can have a negative impact on health (Creek 2003). The therapist assesses how a person uses their time over the course of days and weeks, whether there are empty times or times when there is too much to do. It is also helpful to find out if the person’s time use has changed recently, perhaps with the loss of a major occupation or with the introduction of new demands?

Daily activities are organized into routines that support an individual’s sense of self and, if performed regularly, become habitual; for example, driving involves a sequence of actions that becomes habitual so that one does not have to think carefully about every stage of the operation. Routines and habits enable the individual to perform everyday tasks without having to remember consciously how to go about them. They are developed to suit the individual’s needs at any one period of life; new habits are learned and old ones discarded as circumstances change. The therapist assesses how people organize their time; that is, whether they have useful habits or have to expend a lot of time and energy deciding what to do and working out ways of performing.

Abilities, strengths and interests also influence the range of occupations a person adopts and the way these occupations are performed. Ability is the measure of the level of competence with which a skill is performed. In order to function effectively in a desired range of actions, a person must have a variety of skills and be able to perform them competently. When assessing individuals, it should be taken into account that competence is not an absolute concept; norms for competence vary with age and are to some extent socially defined (Mocellin 1988). Competence exists on a continuum and when assessing competence in completion of skills, it is important for the therapist to acknowledge their own bias and thresholds for acceptability and to question these in the context of the individual they are working with.

Strengths are the personal factors that enable a person to function effectively. They include skills, other personal attributes and social networks. The therapist assesses an individual’s strengths, so that interventions can be designed to support and build on them as an enabler of change. Interest is the expectation of pleasure in an activity which is aroused by a combination of experience and some degree of novelty. Experience tells us that we have enjoyed something similar in the past and novelty arouses in us the urge to try a new experience. It is important to know what an individual’s interests are so that interventions can be designed that are appropriate and support an individual’s sense of self. Gaining understanding of an individual’s occupational choices and whether these are externally or internally influenced helps to ascertain whether interests are genuine or presumed. For example a person may spend a lot of time watching shopping programmes on television, but it would be wrong to presume this is due to interest; it may be due to an inability to sleep.

Roles are patterns of activity associated with social position. A role contributes to the individual’s sense of social and personal identity and also influences the way in which occupations are performed. A properly integrated role, supported by the skills and habits necessary for its performance, satisfies both society’s expectations and the individual’s needs. Roles are defined by society and assigned to individuals on the basis of such attributes as age, gender, relationships, possessions, education, job, income and appearance. For example, a person’s roles vary in different places: their role at work; being a consumer when shopping and being a parent at home. Each role carries expectations of occupational performance, which the individual who accepts the role attempts to carry out. Therefore, an occupational therapist should consider roles as part of assessment. The range of roles and occupations the person has engaged in over time should be explored, as well as the level of satisfaction these have provided for them, and what barriers or restrictions to role participation the person has previously experienced.

People have a basic urge to be active, known as volition. They test their own potential and seek to have an impact on their surroundings. The extent to which they act on that urge is known as motivation. The actions they choose are influenced by life experiences. Fidler and Fidler (1978) stated that each person learns their own capacities through doing. Assessment should include exploration of an individual’s occupational behaviour and their ability to choose what to do and initiate it. Decisions about what to do may be influenced by the person’s internal beliefs, values and interests, but also by their level of competence and external environments and relationships. Developing an understanding of these during the assessment will help the therapist influence change during the intervention phase.

Achievement through participation is influenced by an individual’s aspirations and expectations. A person who has experienced persistent failure, due to a lack of skill or lack of opportunity to do, may feel incompetent, lacking in control and have little expectation of success or hope for the future. This will influence how a person engages and what in. Successful doing leads to a sense of satisfaction and a sense of competence and therefore builds confidence and aspirations. It is important that interventions match the person’s aspirations and expectations, offering a ‘just right challenge’. However, the capacity to make realistic plans for the future can be affected by fear of failure or by illness. The assessment process is designed to elicit both what the person would like to achieve and how realistic those aspirations are.

Function and dysfunction are not opposites but exist on a continuum. Spencer (1988, p. 437) pointed out that:

Temporary or permanent disability takes on a unique meaning for each individual. Age, developmental stage, previous ability, achievements, life-style, family status, self-concept, interests and general responsibilities affect attitudes such as understanding, acceptance, motivation and emotional response …. An accurate analysis of the bio psychosocial context by the therapist is essential to determine the functional implications of the patient’s condition.

During assessment, it is important to take a temporal perspective, considering an individual’s past level of functioning and expected future occupations as well as present capabilities, in order to find out whether they have lost skills or never developed competence in certain areas. The ways in which function and dysfunction are conceptualized are determined by the frame of reference the occupational therapist is using. For example, using the adaptive skills model (Reed and Sanderson 1992), dysfunction is seen in terms of lack of mastery of the adaptive skills appropriate to the individual’s age and stage of development. Within a cognitive behavioural frame of reference, dysfunction is seen in terms of faulty information processing, irrational thinking and distorted perceptions.

Change will also be influenced by external factors such as the physical environment, the goals of the family or carers, social support networks and social expectations. All these factors must be assessed and taken into account when setting or modifying goals and planning what those involved would like the outcome of intervention to be.

The environment includes both physical factors, such as poor housing or inadequate public transport, and social factors, such as poverty or working in an unsatisfying job. The physical environment is likely to include the person’s place of residence, workplace and local or wider community and community locations. Areas to consider in assessment of home environment include: the type and quality of housing; whether it is temporary or permanent accommodation; access to the home; any problems, such as damp or infestation; facilities such as space, heating and garden; privacy; furnishings and organization of household goods; comfort; where the home is situated; whether it is convenient for transport, shops, libraries and open spaces; distance from the workplace and the character of the neighbourhood. For a work environment, they may include: location in relation to home; transport; access; space, including characteristics of the working space and the total area of the workplace; facilities, such as canteen and health care; noise levels; heating and air conditioning; any hazards, and tools or equipment. Community environments vary considerably, for example rural communities and city communities. Assessment should consider factors such as: the type of neighbourhood; community resources such as shops and leisure facilities; public transport infrastructure; access to healthcare, including GP, dentist and optician; and open spaces. Such assessment will also include consideration of which aspects of the physical environment could be adapted, altered or influenced to encourage an individual’s occupational participation, and which are fixed.

The social environment consists of the people who make up the individual’s social world, at home, at work and in other areas of life. This includes: neighbours; family; friends; work colleagues; casual contacts, such as shopkeepers and dog walkers; social groups, such as club members, e.g. working men’s clubs, and parent toddler groups; and internet contacts (including the person’s own avatars and virtual friends and acquaintances). All these people influence and shape how a person feels about themselves through the roles that are assigned to them and the expectations that go with those roles. Alongside this are the relationships that people have with their pets that can also influence how a person perceives themselves and influence meaningful role fulfilment.

An element of personal, physical or environmental risk is involved during any occupational engagement to a greater or lesser degree. When assessing each of the areas above, the level of risk should be considered as part of assessment, with the understanding that risk is an integral part of doing and being in daily life. It cannot be eliminated while maintaining healthy occupational participation. Particular risks related to occupational performance can be identified during assessment, for example the risk of someone self-harming if they fail to perform adequately a task or activity that they expected to be competent in or the risk of being knocked over when crossing the road. However, in order to develop or maintain skills or competencies, it is often necessary to withstand and work through risk issues or minimize them through changing/adapting the environment or an individual’s thoughts and behaviour. Individual perceptions of risk and tolerance for risk-taking can be a barrier to occupational engagement. Their roles and occupational opportunities may be affected by risky behaviour choices. Others, with professional or personal accountability or responsibility for the person, may have different perceptions of risk or tolerance for risk-taking, which will also create barriers to occupation. Therapeutic risk-taking is a regular component of working with individuals to promote change, and for many people taking the step to engage with services in order to change their lives, is a major risk in itself. (Risk is also discussed in Chs 7, 11, 12, 23, 24 and 25.)

Occupational therapists use a wide range of assessment methods and tools, from interviews to assessment batteries. Some are assessment methods widely used by the different professionals in a multi-disciplinary team: review of records, interviews, observations, proxy reports, and home (environmental) visits (see Table 5-1). Methods more specific to occupational therapy are those that focus on function and involve activity or occupation, such as:

■ activity checklists

■ performance scales

■ occupation- or activity-focused questionnaires

■ projective methods (see Table 5-2).

There are two main methods of assessment: standardized assessments and non-standardized assessments (see Glossary). Both of these methods can also be used to measure the outcomes of interventions.

A standardized assessment is a reliable and valid tool which is standardized for a population. This involves establishing the performance of a similar group of people for comparison. The process is called standardization of results, or ‘norm referencing’. Norm-referenced data are collected through a lengthy procedure that involves administering a reliable and valid assessment procedure to a large number of people who are matched for such factors as gender, age, cultural background and possibly disability. The results are presented as a numerical scale, representing the normal range of performance for that group. These can be compared with these typical, or normative, data. There is usually a clear, uniform procedure for using the test. This is called standardization of administration and is usually described in the test’s manual; often training is required to learn how to administer the test. The Assessment of Motor Process Skills is a widely used standardized assessment in occupational therapy (Fisher and Bray Jones 2012), which requires occupational therapists to complete a training course before they can use it in their practice.

A non-standardized assessment is a tool that has not been norm referenced and does not required standardized administration. It may or may not have been tested for reliability and validity.

Whether using standardized or non-standardized assessments, the two most important considerations in ensuring accuracy of an assessment results are the assessment’s reliability and validity.

Reliability refers to consistency; if a tool is reliable its results will not be affected by when it is administered or who administers it. When using assessments or outcome measures occupational therapists want to be sure that the measure has one or more of the following:

1. Test–retest reliability involves checking that the same results will be achieved each time the tool is used. An occupational therapist will want to check that this procedure was conducted during a test’s development so they can be sure the results of the tool reflect the person’s performance and not some other factor, such as the time of day when the tool was conducted.

2. Intra-rater reliability involves checking that the same results will be achieved every time the same person uses it. This is important to an occupational therapist because they want to be sure their administration of the tool does not impact on the results, which should indicate the performance of the person being assessed and not their ability to administer the tool.

3. Inter-rater reliability involves checking that the same results will be achieved regardless of who administers the tool. This is important because an occupational therapist will want to be sure any results of a tool administered reflect the performance of the person being assessed and not the person administering the tool.

An occupational therapist can find out whether a test or procedure has reliability from its manual and/or from research articles, which have studied the test or procedure.

Validity refers to whether an assessment measures what it is intended to measure. Validation involves checking this: if we want to know whether a person is able to cook a meal on a gas cooker, there is no point in assessing the person’s performance on an electric cooker. There are three main types of validity.

1. Content or face validity involves scanning the tool’s content to see if it purports to measure what it is supposed to. It is a weak form of validity but a useful technique to use in clinical practice to make a quick judgement about whether a tool is likely to be useful or not.

2. Criterion-related or concurrent validity is a process of checking how the tool performs against other assessments (sometimes called gold standard assessments) or other accepted criterion. If research studies show a tool performs well this confirms it is an appropriate means of assessing people.

3. Construct validity involves examining, during the development of the tool, how far the assessment truly reflects the theories or hypotheses it is based upon. Again, if a tool has construct validity, it reassures the occupational therapist they are using an appropriate assessment.

If an occupational therapist wants to use an assessment as an outcome measurement as well it should at least be reliable and valid, if not standardized.

Utility indicates how practical a tool is for use in practice. It is another key issue to be considered alongside reliability and validity when selecting an outcome measure to use to assess a service user. This is because if the tool is cumbersome or time-consuming, for example, it will be difficult to integrate into everyday practice (Bannigan and Watson 2009).

Outcome measurement involves the ‘evaluation of the nature and degree of change brought about by intervention, or the extent to which a goal has been reached or an outcome has been achieved’ (Creek 2003, p. 56). Change is measured by comparing assessment results before and after intervention; the difference between the two results is the amount of change that has taken place. An outcome measure therefore detects and measures change over time. This may include measuring against the planned or desired outcomes of intervention, but also involves ascertaining the actual outcomes of intervention. Changes measured may be specific, for example being able to make and maintain appropriate eye contact, or broader, for example, gaining employment.

Outcome measurement is tied into the development of a credible evidence base for interventions and their effectiveness. The overall aims of occupational therapy intervention include occupational participation, engagement, competence, satisfaction and balance. The measures occupational therapists choose and use should therefore reflect these aims, whether at a specific skill level or more broadly. The benefits of outcome measurement include:

■ evaluation of the effects of occupational therapy intervention

■ demonstration of progress

■ modification of intervention plans for greater meaning

■ elimination of wasteful or ineffective strategies

■ planning future service developments

■ predicting effects of intervention for the future

■ providing evidence to support practice (Clarke et al. 2001).

Fuller (2011) has highlighted the lack of clinically based studies with evidence for the reliability and validity of outcome measures of occupational performance, such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM); Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS); the Occupational Therapy Task Observation Scale (OTTOS) and the Assessment of Communication and Interaction Skills (ACIS). More research is required in this area (see Ch. 9 for a discussion of research and evidence-based practice).

Occupational therapists need to be aware of the different approaches to measuring outcomes: individualized; standardized; patient-reported; patient-reported experience; and clinician-reported or -rated outcome measures.

Individualized outcome measures compare a person’s performance after intervention with how they performed before intervention, rather than judging performance against a norm. These measures are sensitive to small changes and to those which may be important to the person (Spreadbury and Cook 1995). For example, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (Law et al. 1994) is designed to detect changes in the individual’s own perception of their occupational performance over time and can be used with a wide range of people. Individualized outcome measures used by occupational therapists, include the Binary Individualized Outcome Measure (Spreadbury and Cook 1995); Goal Attainment Scaling (Ottenbacher and Cusick 1993) and the COPM (Law et al. 1994). Some individualized outcome measurement tools, such as the COPM, are scaled; that is, they produce a score on a numerical scale. However, the scale does not represent a normal distribution and cannot be used to compare one person’s performance with another’s; the person measures themselves against their own previously set goals, aspirations and expectations. The process of using an individualized outcome measure has four stages: goal setting, baseline assessment, intervention and reassessment. This process can be carried out as many times as is needed for an individual to reach all their important goals.

Standardized outcome measures have been tested for reliability and validity with large groupings of particular populations. Scores for the population are published so that the results achieved from any assessment can be compared with the normal range for that population. For example, the Barthel Index is a standardized assessment of functional independence in personal care and mobility for older people (McDowell and Newell 1996). Standardized outcome measures used by occupational therapists include the Allen Cognitive Level Screen (Allen 1985) and the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (Fisher and Bray Jones 2012). It is important that standardized assessments are used with the population for whom they are designed and that they are administered following the exact standardized procedures. Some tools require that a therapist is trained and certified before using them, to ensure correct use. If a standardized assessment is modified, used with people other than those it was designed for or administered in a way that deviates from the standardized procedure, the results will be invalid. When using standardized outcome measures, occupational therapists need to ensure they comply with the copyright conditions.

This type of measurement is important in measuring the effectiveness of care from the individual’s perspective. Often a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) consists of a questionnaire related to the expected or planned goals of intervention. Alternatively, a PROM is a rating scale related to how the person feels at the time about the activities they need and want to do in daily life. PROMS are particularly useful for measuring progress related to subjective, personal change indicated by feelings and emotions, or quality of life. A positive PROM can simply be indicated by a person confirming that an aspect of their occupational performance has improved since participating in an occupational therapy intervention. An example of a specific occupational therapy patient-reported outcome is the Occupational Self-Assessment (OSA) (Baron et al. 2006).

The OSA is a two-part questionnaire used to help people identify their own occupational competence and how meaningful and important competence in particular performance areas is for them. It constitutes a list of 21 occupational performance items and 10 environment items, each of which an individual rates, according to how they perceive their abilities and how valued these activities are to them. Completion of the competency scoring initially allows the person to gain an understanding of the range of items covered in the assessment, before identifying the level of importance of these in relation to each other. The final step is for an individual to identify priorities for change, with or without assistance from the therapist, in order to then set collaborative goals/identify desired outcomes. Repetition of the scale gives an outcome measure of how an individual feels their competence has improved in each of the areas, and whether the individual perception of importance has altered (possibly due to a change in perceived competence over time).

This type of measure focuses on the person’s experience of the care or service they have received, and again consists of personal opinion, often reported via questionnaires and comparison scales (verbal or written). Rather than measuring the change or improvement in symptoms, function or overall health and quality of life, measurement in this case tends to relate to elements such as the helpfulness of staff, choice, cleanliness, dignity and quality of food. As such, occupational therapists are unlikely to use generic measures that are used across services and professions, because unless the person is clearly focused on their experience of the occupational therapy service they received specifically, experience outcomes can be blurred and shared across services. Photographs of staff may be useful in tying ratings of experience to specific staff members and the service they delivered (and therefore to occupational therapy, if this is what they were delivering). Some services have begun working on incorporating PROMs and PREMs as a single measure (Gibbons and Fitzpatrick 2012). However these are more likely to be valid in measuring overall outcome and experience, providing broad information for service development, rather than on person-specific change targeted at the smaller personal barriers each individual is experiencing.

In occupational therapy, these are measures that are rated and reported by the occupational therapist or those supporting occupational therapy. Some standardized assessments in occupational therapy are clinician-reported, e.g. the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) (Fisher and Bray Jones 2012) and the Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST) (Parkinson et al. 2006). Non-standardized clinician-reported outcome measures can be problematic, as they have not been adequately tested for reliability and validity. They are subjective, being influenced by the values and beliefs of the person scoring.

AMPS involves observation of specific standardized tasks in areas of personal or instrumental activities of daily living, identified as meaningful by the person being assessed. It allows a measure of overall performance of chosen tasks, but also the quality of an individual’s motor and process skills, for example do they demonstrate increased clumsiness, decreased efficiency, need for assistance, increased physical effort or safety concerns/risk. In total, 16 motor and 20 process performance skills are scored and used to influence occupation-focused goal-setting and intervention planning.

The use of outcome measures relates to the measurable element of goal-setting (see Chs 4 and 6 for further discussion on goal-setting), but the choice of measure is dependent on what the individual and their therapist wish to measure. Some outcome measures are simple, in that if, for example, a person has a goal of returning to full-time employment within 6 months, this can be measured by whether they have or have not done so. However the process of achieving something, such as returning to work, is far more complex. Smaller elements may be monitored and measured to indicate progress towards the broader goal.

The process of selecting an outcome measure starts with the initial screening, where the individual and the occupational therapist decide whether occupational therapy is indicated. As the occupational therapy process continues, the therapist should carefully consider the assessments they are using: to identify barriers to occupational performance at the level of skill, task, activity or occupation that are compromising the person’s ability to meet their goals. The use of an outcome measure as part of assessment provides the baseline against which to measure later in the occupational therapy process.

A chef, who has been in an accident which has affected his occupational performance across all domains, might identify his occupational goal as ‘to return to work in a restaurant’. He may be aware that there are areas for improvement which need to be worked on prior to that being possible. The occupational therapist helps identify barriers to achieving that goal, e.g. reduced confidence and increased anxiety around others; perceptual disturbance; motor coordination difficulties; reduced motivation to get out of bed; reduced ability to cut vegetables; difficulty monitoring timespans for activity completion; problems turning up at expected times; difficulty keeping a uniform clean and remembering to bring it to work. The chef and occupational therapist collaboratively plan interventions to achieve the chef’s occupational goal through achievement of smaller goals. These address the identified barriers through interventions which may include; confidence-building, skills training, perceptual adaptations, memory strategies and other interventions. Priority areas to be worked on first are identified collaboratively.

Different measures may be required to assess, monitor and review these smaller, interim goals. Outcome measures in this example may therefore relate to getting out of bed every day by a certain time, or may perhaps take the form of measuring improvement of skills. For the former, basic checklists and charts may be most useful, and for the latter, a standardized observational outcome measure such as AMPS. Occupational therapists need to be clear in their identification of occupational barriers through assessment. This is because, unless planned interventions target the areas which require change, there is little to be achieved from either continuing or trying to measure the change.

The use of multiple outcomes measures may be necessary when more than one goal is set, or when one goal is set but there are several occupational barriers to meeting that goal and interventions are required at different levels to achieve this, for example skill (or body function), task, activity and occupation. The therapist formulates problems at different levels, as: occupational imbalance; occupational performance deficits; activity limitation; task performance problems; or skills deficits.

Measures across all these areas may be used and can be used individually or simultaneously as required, as during the occupational therapy process the therapist shifts the focus of attention from occupation, to activity, to task, to skill and back again. This shift of perspective happens many times during an intervention (Creek 2003). Just as the use of one type of intervention does not have to come before the other in a linear fashion, different measures can be used alongside each other, as long as they are valid, i.e. truly measure what is expected to change. It is not effective to measure range of movement related to dressing, when the main barrier is an ability to make choices.

Having agreed on the areas of function that the individual wants to or needs to improve and the priorities for intervention, the therapist works with the individual to set goals for meeting the identified needs (see Ch. 6). It is important that the desired outcome of the intervention is clearly formulated and recorded in the goals set. They may need to be expressed on different levels, from developing skills, through performing tasks and engaging in activities, to performing occupations and enabling social participation. The relationship between goals and outcomes is described in Chapter 3 and the process of goal-setting is outlined in Chapter 6.

This chapter has explored the assessment and outcome measurement stages of the occupational therapy process. Assessment is an integral part of skilled intervention, not a series of separate stages, and outcome measurement allows the changes made as a result of this intervention to be made explicit and demonstrable. Consideration of outcome measurement begins during assessment and continues throughout intervention planning and delivery. This should be borne in mind when reading Chapter 6, which is focused on planning and implementing interventions.

Allen CK. Occupational Therapy for Psychiatric Diseases: Measurement and Management of Cognitive Disabilities. Boston: Little Brown; 1985.

Azima FJC. The Azima battery: an overview. In: Hemphill BJ, ed. The Evaluative Process in Psychiatric Occupational Therapy. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1982.

Bannigan K, Watson R. Reliability and validity in a nutshell. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009;18(23):3237–3243.

Baron K, Kielhofner G, Lyenger A, et al. The Occupational Self Assessment (OSA) (version 2.2). IL: Model of Human Occupation Clearinghouse, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Chicago; 2006.

Clarke C, Sealey-Lapes C, Kotsch L. Outcome Measures. London: The College of Occupational Therapists; 2001.

Covey SR. The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. London: Simon and Schuster; 1989.

Creek J. Occupational Therapy Defined as a Complex Intervention. London: College of Occupational Therapists; 2003.

Fidler GS, Fidler JW. Doing and becoming: purposeful action and self-actualization. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1978;32(5):305–310.

Fisher AG, Bray Jones K. Assessment of Motor and Process Skills, vol. 1: Development, Standardisation, and Administration Manual. seventh ed CO: Three Star Press Inc; 2012.

Fuller K. The effectiveness of occupational performance outcome measures within mental health practice. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2011;74(8):399–405.

Gibbons E, Fitzpatrick R. Patient Reported Outcome Measures: Their Role in Measuring and Improving Patient Experience. Available at: http://patientexperienceportal.org/ article/patient-reported-outcome-measures-their-role-in-measuring-and-improving-patient-experience. 2012.

Hemphill BJ, ed. The Evaluative Process in Psychiatric Occupational Therapy. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1982.

Katz N. Routine Task Inventory – Expanded. Assessment Manual. 2006. Available at: http://www.allen-cognitive-network.org/index.php/allen-model/routine-task-inventory-expanded-rti-e.

Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. second ed. Toronto: CAOT Publications ACE; 1994.

Matsutsuyu JS. The interest checklist. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1969;23(4):323–328.

Mayers CA. An evaluation of the use of Mayers’ lifestyle questionnaire. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1998;61(9):393–398.

Mayers CA. The Mayers’ Lifestyle Questionnaire (2). York: School of Professional Health Studies, York, St John College; 2004.

McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. second ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Mocellin G. A perspective on the principles and practice of occupational therapy. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1988;51(1):4–7.

Mosey AC. Meeting health needs. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1973;27(1):14–17.

Mosey AC. Psychosocial components of occupational therapy. New York: Raven Press; 1986.

Ottenbacher KJ, Cusick A. Discriminative versus evaluative assessment: some observations on goal attainment scaling. Alternative strategies for functional assessment. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1993;47(4):349–354.

Parkinson S, Forsyth K, Keilhofner G. The Model of Human Occupation Screening Tool (MOHOST) v. 2.0. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois; 2006.

Reed KL, Sanderson SN. Concepts of Occupational Therapy. third ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1992.

Smith NR, Kielhofner G, Watts JH. The relationships between volition, activity pattern, and life satisfaction in the elderly. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1986;40(4):278–283.

Spencer EA. Functional restoration: preliminary concepts and planning. In: Hopkins HL, Smith HD, eds. Willard and Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: J B Lippincott; 1988.

Spreadbury P, Cook S. Measuring the Outcomes of Individualised Care: The Binary Individualised Outcome Measure. Nottingham: Trent Regional Health Authority; 1995.

University of Bradford. The Bradford Well-Being Profile. Bradford: University of Bradford; 2008.

Unsworth CA. The concept of function. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1993;56(8):287–292.