Examining Ethics in Nursing Research

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Identify the historical events influencing the development of ethical codes and regulations for nursing and biomedical research.

2. Describe the ethical principles that are important in conducting research on human subjects.

3. Describe the human rights that require protection in research.

4. Identify the essential elements of the informed consent process in research.

5. Describe the role of a nurse in the institutional review of research in an agency.

6. Examine the benefit-risk ratio of published studies and studies proposed for conduct in clinical agencies.

7. Describe the types of possible scientific misconduct in the conduct, reporting, and publication of healthcare research.

8. Critically appraise the protection of human rights and the informed consent and institutional review processes in published studies.

9. Critically appraise the treatment of animals reported in published studies.

Assent to participate in research, p. 102

Breach of confidentiality, p. 107

Covert data collection, p. 101

Principle of beneficence, p. 98

Principle of respect for person(s), p. 98

Fabrication in research, p. 122

Falsification of research, p. 122

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), p. 99

Individually identifiable health information, p. 105

Institutional review board (IRB), p. 117

Nontherapeutic research, p. 96

Ethical research is essential for generating sound empirical knowledge for evidence-based practice, but what does ethical conduct of research involve? This is a question that researchers, philosophers, lawyers, and politicians have debated for many years. The debate continues, probably because of the complexity of human rights issues, the focus of research in new and challenging arenas of technology and genetics, the complex ethical codes and regulations governing research, and the various interpretations of these codes and regulations. This chapter introduces you to the national and international codes and regulations developed to promote the ethical conduct of research.

You might think that unethical studies that violate subjects’ rights are a thing of the past, but this is not the case. There are still situations in which researchers do not protect the subjects’ privacy adequately or the study participants are treated unfairly or harmed during a study. Another serious ethical problem that has increased over the last 20 years is research misconduct. Research misconduct includes incidences of fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in the process of conducting and reporting research in nursing and other healthcare disciplines (Office of Research Integrity [ORI], 2013).

You need to be able to appraise the ethical aspects of published studies and of research conducted in clinical agencies critically. Most published studies include ethical information about subject selection and treatment during data collection in the methods section of the report. Institutional review boards (IRBs) in universities and clinical agencies have been organized to examine the ethical aspects of studies before they are conducted. Nurses often are members of IRBs and participate in the review of research for conduct in clinical agencies.

To provide you with a background for examining ethical aspects of studies, this chapter describes the ethical codes and regulations that currently guide the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research. The following elements of ethical research are detailed: (1) protecting human rights; (2) understanding informed consent; (3) understanding institutional review of research; and (4) examining the balance of benefits and risks in a study. This chapter also provides critical appraisal guidelines for examining the ethical aspects of studies. The chapter concludes with a discussion of two additional important ethical issues, research misconduct and the use of animals in research.

Historical Events Influencing the Development of Ethical Codes and Regulations

Since the 1940s, four experimental projects have been highly publicized for their unethical treatment of human subjects: the Nazi medical experiments, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the Willowbrook Study, and the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study (Berger, 1990; Levine, 1986). Although these were biomedical studies and the primary investigators were physicians, the evidence suggests that nurses understood the nature of the research, identified potential research subjects, delivered treatments to the subjects, and served as data collectors. These unethical studies demonstrate the importance of ethical conduct for nurses while they are reviewing or participating in nursing or biomedical research (Fry, Veatch, & Taylor, 2011; Havens, 2004). These studies also influenced the formulation of ethical codes and regulations that currently direct the conduct of research.

Nazi Medical Experiments

From 1933 to 1945, the Third Reich in Europe was engaged in atrocious and unethical medical activities. The programs of the Nazi regime included sterilization, euthanasia, and medical experimentation for the purpose of producing a population of “racially pure” Germans who were destined to rule the world. The medical experiments were conducted on prisoners of war and persons considered to be racially valueless, such as Jews, who were confined in concentration camps. The experiments involved exposing subjects to high altitudes, freezing temperatures, malaria, poisons, spotted fever (typhus), or untested drugs and performing surgical procedures, usually without any form of anesthesia for the subjects. Extensive examination of the records from some of these studies indicated that they were poorly conceived and conducted. Therefore this research was not only unethical but also generated little if any useful scientific knowledge (Berger, 1990; Steinfels & Levine, 1976).

The Nazi experiments violated numerous rights of the research subjects. The selection of subjects for these studies was racially based and unfair, and the subjects had no choice—they were prisoners who were forced to participate. As a result of these experiments, subjects frequently were killed or they sustained permanent physical, mental, and social damage (Levine, 1986).

Nuremberg Code

Those involved in the Nazi experiments were brought to trial before the Nuremberg Tribunals, and their unethical research received international attention. The mistreatment of human subjects in these studies led to the development of the Nuremberg Code in 1949. Box 4-1 presents this code. The code includes guidelines that should help you evaluate the consent process, protection of subjects from harm, and balance of benefits and risks in a study (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [U.S. DHHS], Office of Human Research Protection [OHRP], 2013).

Declaration of Helsinki

The Nuremberg Code provided the basis for the development of the Declaration of Helsinki, which was adopted in 1964 and revised most recently in 2008 by the World Medical Association (WMA, 2008). A major focus of the initial document was the differentiation of therapeutic research from nontherapeutic research. Therapeutic research provides patients with an opportunity to receive an experimental treatment that might have beneficial results. Nontherapeutic research is conducted to generate knowledge for a discipline; the results of the study might benefit future patients but probably will not benefit those acting as research participants.

The Declaration of Helsinki includes the following ethical principles: (1) the investigator should protect the life, health, privacy, and dignity of human subjects; (2) the investigator should exercise greater care to protect subjects from harm in nontherapeutic research; and (3) the investigator should conduct research only when the importance of the objective outweighs the inherent risks and burdens to the subjects. The most recent addition to the Declaration of Helsinki is that researchers must use extreme caution in studies in which participants receive a placebo or sham treatment. For example, in studies testing the effectiveness of a drug, the placebo group would receive a pill with no medication and the experimental group would receive a pill with the drug. Researchers must provide the participants in the placebo group with access to proven diagnostic and therapeutic procedures after the study (WMA, 2008). The ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki are available online at http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3. Most institutions in which clinical research is conducted adopted the Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki; however, episodes of unethical research continued to occur in biomedical and behavioral studies.

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

In 1932 the U.S. Public Health Service initiated a study of syphilis in African American men in the small rural town of Tuskegee, Alabama (Rothman, 1982). The study, which continued for 40 years, was conducted to determine the natural course of syphilis in African American men. Many of the subjects who consented to participate in the study were not informed about the purpose and procedures of the research. Some were unaware that they were subjects in a study. By 1936 it was apparent that the men with syphilis had developed more complications than the men in the control group. Ten years later the death rate among those with syphilis was twice as high as it was for the control group. The subjects were examined periodically but were not treated for syphilis, even when penicillin was determined to be an effective treatment for the disease in the 1940s. Information about an effective treatment for syphilis was withheld from the subjects, and deliberate steps were taken to deprive them of treatment (Brandt, 1978).

Published reports of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study started appearing in 1936, and additional papers were published every 4 to 6 years. No effort was made to stop the study; in fact, in 1969 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (then called the Center for Disease Control) decided that the study should continue. In 1972, an account of the study in the Washington Star sparked public outrage; only then did the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) stop the study. The study was investigated and found to be ethically unjustified (Brandt, 1978).

Willowbrook Study

From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, Dr. Saul Krugman conducted research on hepatitis at Willowbrook, an institution for the mentally retarded in Staten Island, New York (Rothman, 1982). The subjects were children who were deliberately infected with the hepatitis virus. During the 20-year study, Willowbrook closed its doors to new inmates because of overcrowded conditions. However, the research ward continued to admit new inmates, and parents had to give permission for their child to be in the study to gain admission to the institution.

From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Krugman’s research team published several articles describing the study protocol and findings. In 1966 Beecher cited the Willowbrook Study in the New England Journal of Medicine as an example of unethical research. The investigators defended injecting the children with the hepatitis virus because they believed that most of the children would acquire the infection on admission to the institution. They also stressed the benefits the subjects received, which were a cleaner environment, better supervision, and a higher nurse-to-patient ratio on the research ward (Rothman, 1982). Despite the controversy, this unethical study continued until the early 1970s.

Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study

Another highly publicized unethical study was conducted at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in New York in the 1960s. The purpose of this study was to determine patients’ rejection responses to live cancer cells. A suspension containing live cancer cells that had been generated from human cancer tissue was injected into 22 patients (Levine, 1986). Because researchers did not inform these patients that they were taking part in a study or that the injections they received were live cancer cells, their rights were not protected. In addition, the study was never presented for review to the research committee of the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital, and the physicians caring for the patients were unaware that the study was being conducted. The physician directing the research was an employee of the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research; there was no indication that this institution had conducted a review of the research project (Hershey & Miller, 1976). This unethical study was conducted without the informed consent of the subjects and without institutional review and had the potential to injure, disable, or cause the death of the human subjects. The study was stopped immediately and steps were taken to ensure proper care for the patients exposed to the cancer cells and to review all future research to be conducted by this agency.

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1973: Regulations for the Protection of Human Research Subjects

The continued conduct of harmful, unethical research from the 1960s to the 1970s made additional controls necessary. In 1973 the DHEW published its first set of regulations for the protection of human research subjects. These regulations also provided protection for persons having limited capacity to consent, such as those who are ill, mentally impaired, or dying (Levine, 1986). According to the DHEW regulations, all research involving human subjects had to undergo full institutional review, which increased the protection of human subjects. However, reviewing all studies without regard for the degree of risk involved greatly increased the time for study approval and reduced the number of studies conducted.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research

Because the DHEW regulations did not resolve the issue of protecting human subjects in research, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was formed in 1978. This commission was established by the National Research Act (Public Law 93-348), which was passed in 1974. The commission identified three ethical principles relevant to the conduct of research involving human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The principle of respect for persons indicates that people should be treated as autonomous agents, with the right to self-determination and the freedom to participate or not participate in research. Those persons with diminished autonomy, such as children, people who are terminally or mentally ill, and prisoners, are entitled to additional protection. The principle of beneficence encourages the researcher to do good and “above all, do no harm.” The principle of justice states that human subjects should be treated fairly in terms of the benefits and the risks of research. Before it was dissolved in 1978, the commission developed ethical research guidelines based on these three principles and made recommendations to the U.S. DHHS in the Belmont Report. (Information on this report and the three ethical principles—respect for persons, beneficence, and justice—are available online at http://or.org/pdf/BelmontReport.pdf). Greaney and colleagues (2012) studied these ethical principles and provided guidelines for applying them in reviewing and conducting nursing research.

Regretfully, violations of human subjects’ rights continue to occur, as evident in letters written by the Office of Human Research Protection (http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/index.html). These violations include omitting required information from informed consent documents, failing to update the consent document when additional information was available about potential risks, and beginning data collection prior to having the study approved by the IRB. In December 2011, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethics Issues released its report, Moral Science: Protecting Participants in Human Subjects Research, which included recommendations for enhancing the protection of human subjects.

Current Federal Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects

In response to the recommendations presented in the Belmont Report, the U.S. DHHS developed a set of federal regulations for the protection of human research subjects in 1981, which have been revised over the years; the most current regulations were approved in 2009. The 2009 regulations are part of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 45, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2009). These regulations provide direction for the (1) protection of human subjects in research, with additional protection for pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, children, and prisoners; (2) documentation of informed consent; and (3) implementation of the IRB process. You can access these regulations online at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf.

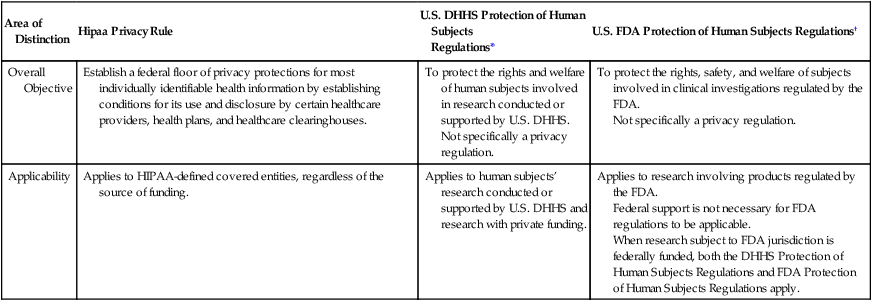

The DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations (U.S. DHHS, 2009) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) govern most of the biomedical and behavioral research conducted in the United States. The FDA, within the DHHS, manages CFR Title 21—Food and Drugs, Part 50, Protection of Human Subjects (FDA, 2012a) and Part 56, Institutional Review Boards (2012b). The FDA has additional human subject protection regulations that apply to clinical investigations involving products regulated by the FDA under the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and research that supports applications for research or marketing permits for these products. These regulations apply to studies of drugs for humans, medical devices for human use, biological products for human use, human dietary supplements, and electronic products (FDA, 2013; http://www.fda.gov). Physician and nurse researchers conducting clinical trials to generate new drugs and refine existing drug treatments must comply with these FDA regulations. Table 4-1 clarifies the focus of the regulations for the protection of human subjects of the DHHS and FDA.

Table 4-1

Clarification of the Focus of Federal Regulations and Impact on Research

| Area of Distinction | Hipaa Privacy Rule | U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations* |

U.S. FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations† |

| Overall Objective |

Establish a federal floor of privacy protections for most individually identifiable health information by establishing conditions for its use and disclosure by certain healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses. | To protect the rights and welfare of human subjects involved in research conducted or supported by U.S. DHHS. Not specifically a privacy regulation. |

To protect the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects involved in clinical investigations regulated by the FDA. Not specifically a privacy regulation. |

| Applicability | Applies to HIPAA-defined covered entities, regardless of the source of funding. | Applies to human subjects’ research conducted or supported by U.S. DHHS and research with private funding. | Applies to research involving products regulated by the FDA. Federal support is not necessary for FDA regulations to be applicable. When research subject to FDA jurisdiction is federally funded, both the DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations and FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations apply. |

*Title 45, CFR Part 46.

†Title 21 CFR, Parts 50 and 56.

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS). (2007b). How do other privacy protections interact with the privacy rule? Retrieved May 29, 2013, from http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_05.asp.

The DHHS and FDA regulations provide guidelines for the protection of subjects in federally and privately funded research to ensure their privacy and the confidentiality of the information obtained through research. With the mechanisms for the electronic access and transfer of individuals’ information, however, the public became concerned about the potential abuses of the health information of persons in all circumstances, including research projects. Therefore a federal regulation—the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA; Public Law 104-191)—was implemented in 2003 to protect people’s private health information (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). Table 4-1 clarifies the focus of HIPAA regulations as compared with the DHHS and FDA regulations (U.S. DHHS, 2007b).

The DHHS developed regulations entitled the Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information; compliance with these regulations is known as the Privacy Rule (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). The HIPAA Privacy Rule established a category known as protected health information (PHI), which allows covered entities, such as health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers that transmit health information, to use or disclose PHI to others only in certain situations. These are discussed later in this chapter.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule has an impact not only on the healthcare environment, but also on the research conducted in this environment. A person must provide his or her signed permission, or authorization, before that person’s PHI can be used or disclosed for research purposes. Researchers must develop their research projects to comply with the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The DHHS has a website, HIPAA Privacy Rule: Information for Researchers, which addresses the impact of this rule on the informed consent and IRB processes in research and answers common questions about HIPAA (http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov; U.S. DHHS, 2007a). The HIPAA Privacy Rule has had a negative effect on researchers’ abilities to conduct studies; the Institute of Medicine and other professional organizations are encouraging lessening the impact or removing research from the HIPAA regulation (Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2009).

Protecting Human Rights

What are human rights? How are these rights protected during research? Human rights are claims and demands that have been justified in the eyes of an individual or by the consensus of a group of people. Nurses who critically appraise published studies, review research for conduct in their agencies, or assist with data collection for a study have an ethical responsibility to determine whether the rights of the research participants are protected. The human rights that require protection in research are the rights to (1) self-determination, (2) privacy, (3) anonymity and confidentiality, (4) fair selection and treatment, and (5) protection from discomfort and harm (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2001; American Psychological Association [APA], 2010; Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Fowler, 2010; Fry et al., 2011). The ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) provides nurses with guidelines for ethical conduct in nursing practice and research. This code focuses on protecting the rights of patients and research participants. Fowler (2010) provides a detailed interpretation and application of the statements in this code.

Right to Self-Determination

The right to self-determination is based on the ethical principle of respect for persons, and it indicates that humans are capable of controlling their own destiny. People should be treated as autonomous agents who have the freedom to conduct their lives as they choose, without external controls. Researchers treat subjects as autonomous agents in a study when they (1) inform them about the study, (2) allow them to choose whether or not to participate, and (3) allow them to withdraw from the study at any time, without penalty (ANA, 2001; Banner & Zimmer, 2012; Greaney et al., 2012).

Violation of the Right to Self-Determination

A subject’s right to self-determination can be violated through the use of coercion, covert data collection, and deception. Coercion occurs when one person intentionally presents an overt threat of harm or an excessive reward to another to obtain compliance. Some subjects are coerced (forced) to participate in research because they fear harm or discomfort if they do not participate. For example, some patients believe that their medical and nursing care will be negatively affected if they do not agree to be research participants. Others are coerced to participate in studies because they believe that they cannot refuse the excessive rewards offered, such as large sums of money, special privileges, or jobs (U.S. DHHS, 2009; Emanuel, 2004; Fry et al., 2011).

With covert data collection, subjects are unaware that research data are being collected (Reynolds, 1979). For example, in the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study, most of the patients and their physicians were unaware of the study. The subjects were informed that they were receiving an injection of cells, but the word cancer was omitted (Beecher, 1966).

The use of deception, the actual misinforming of subjects for research purposes, can also violate a subject’s right to self-determination (Kelman, 1967). A classic example of deception is seen in the Milgram study (1963), in which the subjects thought they were administering electric shocks to another person, but the person was really a professional actor who pretended to feel the shocks. If deception is used in a study, the research report should indicate how the subjects were deceived, provide a rationale for the use of deception, and discuss when the subjects were informed of the actual research activities and the findings (U.S. DHHS, 2009).

Persons with Diminished Autonomy

Persons have diminished autonomy when they are vulnerable and less advantaged because of legal or mental incompetence, terminal illness, or confinement to an institution (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a). They require additional protection of their right to self-determination because of their decreased ability or inability to give informed consent. In addition, they are vulnerable to coercion and deception. The research report should include justification for the use of these subjects, and the need for justification increases as the subjects’ risks and vulnerability increase.

Study participants with legal and mental diminished autonomy

Minors (neonates and children), pregnant women and fetuses, mentally impaired persons, and unconscious patients are legally and/or mentally unable to give informed consent. These individuals have diminished autonomy because they often lack the ability to comprehend information about a study and/or make decisions about participating in or withdrawing from the study. They have a range of vulnerability, from minimal to absolute. The use of persons with diminished autonomy as research subjects is more acceptable if the following are true: (1) the research is therapeutic—that is, the subjects might benefit from the experimental process; (2) researchers are willing to use vulnerable and nonvulnerable people as subjects; (3) the risk is minimized in the study; and (4) the consent process is strictly followed to ensure the rights of the prospective subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2009).

Neonates

A neonate is defined as a newborn and is identified as viable or nonviable on delivery. Viable neonates are able to survive after delivery, if given the benefit of available medical therapy, and can independently maintain a heartbeat and respiration. “A nonviable neonate means that a newborn after delivery, although living, is not viable,” or cannot sustain life (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.202). Neonates are extremely vulnerable and require extra protection to determine whether they should be involved in research. However, viable neonates, neonates of uncertain viability, and nonviable neonates may be involved in research if the following conditions are met: (1) the study is scientifically appropriate and preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted and provide data for assessing the potential risks to the neonates; (2) the study provides important biomedical knowledge, which researchers cannot obtain by other means, and will not add risk to the neonate; (3) the research holds out the prospect of enhancing the probability of survival of the neonate; (4) both parents are fully informed about the research during the consent process; and (5) researchers will have no part in determining the viability of a neonate. In addition, for nonviable neonates, “the vital functions of the neonate should not be artificially maintained and the research should not terminate the heartbeat or respiration of the neonate” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.205).

Children

The laws defining the minor status of a child are statutory and vary from state to state. Often, a child’s competence to give consent depends on his or her age, with incompetence being irrefutable up to age 7 years (Broome, 1999; Thompson, 1987). However, by age 7, children can think in terms of concrete operations and can provide meaningful assent to participation as research subjects. With advancing age and maturity, the child can play a stronger role in the consent process.

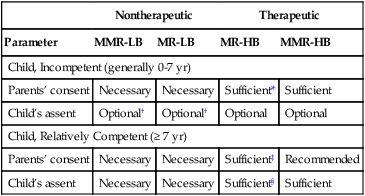

The DHHS regulations require “soliciting the assent of the children (when capable) and the permission of their parents or guardians. Assent to participate in research means a child’s affirmative agreement to participate in research. … Permission to participate in research means the agreement of parent(s) or guardian to the participation of their child or ward in research” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.402). The therapeutic nature of the research and the risks versus benefits also influence the decision about using children as research subjects. Thompson (1987) developed a guide for obtaining informed consent based on the child’s level of competence, therapeutic nature of the research, and risks versus benefits. This guide is presented in Table 4-2 and will assist you in evaluating the ethics of a study that includes children. Box 4-2 presents an example of an assent form for children 6 to 12 years of age developed by Broome (1999).

Table 4-2

Guide to Obtaining Informed Consent*

| Nontherapeutic | Therapeutic | |||

| Parameter | MMR-LB | MR-LB | MR-HB | MMR-HB |

| Child, Incompetent (generally 0-7 yr) | ||||

| Parents’ consent | Necessary | Necessary | Sufficient* | Sufficient |

| Child’s assent | Optional† | Optional† | Optional | Optional |

| Child, Relatively Competent (≥ 7 yr) | ||||

| Parents’ consent | Necessary | Necessary | Sufficient‡ | Recommended |

| Child’s assent | Necessary | Necessary | Sufficient§ | Sufficient |

HB, High benefit; LB, low benefit; MMR, more than minimal risk; MR, minimal risk.

*Based on the relationship between a child’s level of competence, therapeutic nature of the research, and risk versus benefit. A parent’s refusal can be superseded by the principle that a parent has no power to forbid the saving of a child’s life.

†Children making a “deliberate objection” would be precluded from participation by most researchers.

‡In cases not involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.”

§In cases involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.”

There is an increased need for ethical research with children and adolescents as subjects. Researchers are being urged to conduct clinical trials with children to determine the effectiveness of select pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for various age groups (Rosato, 2000). Congress enacted the Pediatric Research Equity Act (FDA, 2003) to promote the inclusion of children and adolescents in clinical research. To achieve this goal, parents must be actively involved with their children in the research process to promote the increased participation of young people in research (Hadley, Smith, Gallo, Angst, & Knafl, 2007). It is better to contact children and their parents directly rather than by phone, e-mail, or mail to increase their participation. Also, the approval process by an IRB is more complex when conducting research on children (Savage & McCarron, 2009). Published studies need to indicate clearly that the child gave assent and the parents or guardians gave permission before data were collected.

Pregnant women and fetuses

Pregnant women require additional protection in research because of the presence of the fetus. Federal regulations define pregnancy as encompassing the period of time from implantation until delivery. “A woman is assumed to be pregnant if she exhibits any of the pertinent presumptive signs of pregnancy, such as missed menses, until the results of a pregnancy test are negative or until delivery” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.202). Research conducted with pregnant women should have the potential to benefit the woman or fetus directly. If the investigation provides a direct benefit just to the fetus, researchers need to obtain the consent of the pregnant woman and father. Studies with “pregnant women should include no inducements to terminate the pregnancy and the researcher should have no part in any decision to terminate a pregnancy” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.204).

Persons with mental illness or cognitive impairment

Certain persons, because of mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a comatose state, are incompetent and incapable of giving informed consent. Persons are said to be incompetent if, in the judgment of a qualified clinician, they have those attributes that ordinarily provide the grounds for designating incompetence. Incompetence can be temporary (e.g., with inebriation), permanent (e.g., with advanced senile dementia), or subjective or transitory (e.g., with behavior or symptoms of psychosis; Beebe & Smith, 2010; Simpson, 2010). If a person is judged incompetent and incapable of giving consent, the researcher must seek approval from the prospective subject and his or her legally authorized representative. A legally authorized representative is a person or another body authorized under applicable law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject to the subject’s participation in the research procedure(s) and must be addressed in the research report (U.S. DHHS, 2009; Rotenberg & Rudnick, 2011).

Terminally ill subjects

Participating in research may carry increased risks, with minimal or no benefits for terminally ill subjects. In addition, the dying subject’s condition potentially may affect the study results, leading researchers to misinterpret the findings. Cancer patients are an example of an overstudied population. It is not unusual for several of the procedures performed on cancer patients to be a result of research protocols that include blood work, bone marrow aspirations, body scans, lumbar punctures, and biopsies. These biomedical research treatments can easily compromise the care of these patients, which poses ethical dilemmas for clinical nurses. Nurses are responsible for ensuring adherence to ethical standards in research as they participate in an institutional review of research and serve as patient advocates in clinical settings (ANA, 2001; U.S. DHHS, 2009; Fowler, 2010).

Persons confined to institutions

Prisoners are people who are confined to institutions and are designated as having diminished autonomy by federal law (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Prison inmates may feel coerced to participate in research because they fear harm or desire the benefits of early release, special treatment, or monetary gain.

Hospitalized patients are also a vulnerable population but are not designated as having diminished autonomy by law. Patients are vulnerable because they are ill and are confined in settings controlled by healthcare personnel. Some hospitalized patients feel obligated to be research participants because they want to assist a particular nurse or physician with his or her research. Others feel coerced to participate because they fear that their care will be adversely affected if they refuse. In their study report, researchers need to document that the rights of patients were protected during the study.

Right to Privacy

Privacy is the freedom people have to determine the time, extent, and general circumstances under which their private information will be shared with or withheld from others. Private information includes a person’s attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, opinions, and records. The research subject’s privacy is protected if the subject is informed, consents to participate in a study, and voluntarily shares private information with a researcher. An invasion of privacy occurs when private information is shared without a person’s knowledge or against his or her will. The invasion of subjects’ right to privacy brought about the Privacy Act of 1974. Because of this act, people now have the right to provide or prevent access of others to their records. A research report often will indicate that the subjects’ privacy was protected and may include the details of how this was accomplished.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule expanded the protection of a person’s privacy—specifically, his or her protected, individually identifiable health information—and described how covered entities can use or disclose this information. Covered entities are healthcare providers, health plans, employers, and healthcare clearinghouses (public or private entities that process or facilitate the processing of health information). Individually identifiable health information (IIHI) means that:

… any information, including demographic information collected from an individual that is created or received by a healthcare provider, health plan, or healthcare clearinghouse; and related to past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual, the provision of health care to an individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual, and identifies the individual; or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the individual.

U.S. DHHS, 2007a, 45 CFR, Section 160.103

According to the HIPAA Privacy Rule, the IIHI is protected health information (PHI) transmitted by electronic media, maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in any other form or medium. The HIPAA privacy regulations affect nursing research in the following areas (U.S. DHHS, 2007a; Olsen, 2003; Stone 2003):

1. Accessing data from a covered entity, such as reviewing a patient’s medical record in clinics or hospitals.

2. Developing health information, such as the data developed when an intervention is implemented in a study to improve a subject’s health.

3. Disclosing data from a study to a colleague in another institution, such as sharing data from a study to facilitate development of an instrument or scale.

The DHHS developed guidelines to assist researchers, healthcare organizations, and healthcare providers in determining when they can use and disclose IIHI. IIHI can be used or disclosed to a researcher in the following situations (U.S. DHHS, 2007a):

• The protected health information (PHI) has been de-identified under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

• The data are part of a limited data set, and a data use agreement with the researcher(s) is in place.

• The person who is a potential subject for a study provides authorization for the researcher to use and disclose his or her PHI.

• A waiver or alteration of the authorization requirement is obtained from an IRB or privacy board.

The first two items are discussed in this section of the text. The section “Understanding Informed Consent” discusses the authorization process, and the section “Understanding Institutional Review” covers the waiver or alteration of authorization requirement.

De-Identifying Protected Health Information under the Privacy Rule

Covered entities, such as healthcare providers and agencies, can allow researchers access to health information if the information has been de-identified. De-identifying health data involves removing the elements that could identify a specific person or that person’s relatives, employer, or household members. You need to be aware of these elements to ensure that a patient’s PHI is kept confidential in the healthcare agencies in which you work or are a student. The elements that require de-identifying are (U.S. DHHS, 2007a):

• All geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, including street address, city, county, precinct, ZIP code, and their equivalent geographic codes, except for the initial three digits of a ZIP code

• All elements of dates (except year) for dates directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission date, discharge date, date of death, and all ages over 89 years and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 90 years or older

• Electronic mail (e-mail) addresses

• Health plan beneficiary numbers

• Certificate and/or license numbers

• Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers

• Device identifiers and serial numbers

• Web universal resource locators (URLs)

• Internet protocol (IP) address numbers

• Biometric identifiers, including fingerprints and voiceprints

• Full-face photographic images and any comparable images

• Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code, unless otherwise permitted by the Privacy Rule for re-identification

A person’s health information also can be de-identified using statistical methods. However, the covered entity and researcher must ensure that the individual subject cannot be identified, or that there is a very small risk that the subject could be identified from the information collected. The statistical method used for de-identification of the health data must be documented, and the study must certify that the elements for identification have been removed or revised to prevent identification of a specific person. This certification information must be kept for a period of 6 years by the researcher.

Limited Data Set and Data Use Agreement

Covered entities—healthcare provider, health plan, and healthcare clearinghouse—may use and disclose a limited data set to a researcher for a study without an individual subject’s authorization or IRB waiver. However, a limited data set is considered PHI, and the covered entity and researcher need to have a data use agreement. The data use agreement limits how the data set may be used and how it will be protected.

Right to Anonymity and Confidentiality

On the basis of the right to privacy, the research subject has the right to anonymity and the right to assume that the data collected will be kept confidential. Complete anonymity exists when the subject’s identity cannot be linked, even by the researcher, with his or her individual responses (Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013). In most studies, researchers know the identity of their subjects, and they promise the subjects that their identity will be kept anonymously from others and that the research data will be kept confidential. Confidentiality is the researcher’s safe management of information or data shared by a subject to ensure that the data are kept private from others. The researcher must refrain from sharing this information without the authorization of the subject. Confidentiality is grounded in the following premises (ANA, 2001; Fowler, 2010):

1. Individuals can share personal information to the extent that they wish and are entitled to have secrets.

2. One can choose with whom to share personal information.

3. Those accepting information in confidence have an obligation to maintain confidentiality.

4. Professionals, such as researchers and nurses, have a duty to maintain confidentiality that goes beyond ordinary loyalty.

A breach of confidentiality can occur when a researcher, by accident or direct action, allows an unauthorized person to gain access to the raw data of a study. Confidentiality also can be breached in reporting or publishing a study if a participant’s identity is accidentally revealed, violating his or her right to anonymity. Breach of confidentiality is of special concern in qualitative studies that have few study participants and involve the reporting of long quotes made by those participants. In addition, qualitative researchers and participants often have relationships in which detailed stories of the participants’ lives are shared, requiring careful management of study data to ensure confidentiality (Eide & Kahn, 2008; Munhall, 2012a). Breaches of confidentiality that can be especially harmful to participants include those regarding religious preferences, sexual practices, income, racial prejudices, drug use, child abuse, and personal attributes, such as intelligence, honesty, and courage. Research reports need to be examined closely for evidence that the participants’ confidentiality was maintained during data collection, analysis, and reporting (Munhall, 2012a; Sandelowski, 1994). In addition, the research findings in a published study should be reported so that a participant or group of participants cannot be identified by their responses.

Right to Fair Selection and Treatment

The right to fair selection and treatment is based on the ethical principle of justice. According to this principle, people must be treated fairly and receive what they are owed or is comparable to other persons in the same situation. The research report needs to indicate that the selection of subjects and their treatment during the study were fair.

Fair Selection and Treatment of Subjects

Injustices in subject selection have resulted from social, cultural, racial, and sexual biases in society. For many years, research was conducted on categories of people who were thought to be especially suitable as research subjects, such as those living in poverty, charity patients, prisoners, slaves, peasants, dying persons, and others who were considered undesirable (Reynolds, 1979). Researchers often treated these subjects carelessly and had little regard for the harm and discomfort they experienced. The Nazi medical experiments, Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Willowbrook Study, and Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study all exemplify unfair subject selection (Levine, 1986).

Another concern with subject selection is that some researchers select subjects because they like them and want them to receive the specific benefits of a study. Other researchers have been swayed by power or money to make certain patients subjects so that these patients can receive potentially beneficial treatments. Random selection of subjects can eliminate some of the researchers’ biases that may influence subject selection and strengthens the design of the study (see Chapter 9).

Each study must include a specific researcher-subject agreement or consent form regarding the researcher’s role and subject’s participation in a study (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a). While conducting the study, the researcher must treat subjects fairly and respect that agreement. For example, the activities or procedures that subjects are to perform should not be changed without the subjects’ and IRB’s consent. The benefits promised to the subjects should be provided. Also, subjects who participate in studies should receive equal benefits regardless of age, race, or socioeconomic level.

The research report needs to indicate that the selection and treatment of the subjects were fair. Subjects must have been selected for reasons directly related to the problem being studied and not for their easy availability, compromised position, manipulability, or friendship with the researcher (Greaney et al., 2012; National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978). In addition, the procedures section of the research report must indicate fair and equal treatment of the subjects during data collection (Fawcett & Garity, 2009).

Right to Protection from Discomfort and Harm

The right to protection from discomfort and harm in a study is based on the ethical principle of beneficence, which states that one should do good and, above all, do no harm. According to this principle, members of society must take an active role in preventing discomfort and harm and promoting good in the world around them (ANA, 2001, APA, 2010). In research, discomfort and harm can be physical, emotional, social, or economic or any combination of these four (Weijer, 2000). Reynolds (1972) identified five categories of studies based on levels of discomfort and harm—no anticipated effects, temporary discomfort, unusual levels of temporary discomfort, risk of permanent damage, and certainty of permanent damage.

No Anticipated Effects

No positive or negative effects are expected for the subjects in some studies. For example, studies that involve reviewing patients’ records, students’ files, pathology reports, or other documents have no anticipated effects on the research subjects. These studies involve no direct interaction between the researchers and subjects. However, there is still a potential risk of invading a subject’s privacy. A subject’s IIHI must be protected during data collection and analysis and in publication of the final report for the study to be compliant with the HIPAA regulations (U.S. DHHS, 2007a, 2009).

Temporary Discomfort

Studies that cause temporary discomfort are described as minimal-risk studies, in which the discomfort is similar to what the subject would encounter in his or her daily life and is temporary, ending with termination of the experiment (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Many nursing studies require the completion of questionnaires or participation in interviews, which usually involve minimal risk or are a mere inconvenience for the subjects. The physical discomfort may include fatigue, headache, or muscle tension. The emotional and social risks may include anxiety or embarrassment associated with answering certain questions. The economic risks may include the time commitment for the study or travel costs to the study site.

Most clinical nursing studies examining the effect of a treatment involve minimal risk. For example, a study may involve examining the effects of exercise on the blood glucose levels of diabetic subjects. For the study, the subjects are asked to test their blood glucose level one extra time per day. Discomfort occurs when the blood is obtained, and there is a potential risk of physical changes that may occur with exercise. The subjects may also feel anxiety and fear associated with the additional blood testing, and the testing may be an added expense. The diabetic subjects in this study will encounter similar discomforts in their daily lives, however, and the discomfort will cease with the termination of the study.

Unusual Levels of Temporary Discomfort

In studies that involve unusual levels of temporary discomfort, subjects frequently have discomfort during the study and after they have completed it. For example, subjects may have prolonged muscle weakness, joint pain, and dizziness after participating in a study that required them to be confined to bed for 7 days to determine the effects of immobility. Studies that require subjects to experience failure, extreme fear, or threats to their identity or to act in unnatural ways involve unusual levels of temporary discomfort. In some qualitative studies, researchers ask participants questions that open old wounds or involve reliving a traumatic event (Eide & Kahn, 2008; Fawcett & Garity, 2009). For example, asking participants to describe their sexual assault experience could precipitate feelings of extreme anger, fear, or sadness or any combination of these emotions. In such studies, the IRB protocol is required to include information on the resources to which researchers can refer subjects who have difficulties. Investigators need to indicate in the research report that they were vigilant in assessing the participants’ discomfort and referred them as necessary for appropriate professional intervention.

Risk of Permanent Damage

In some studies, the possibility exists for subjects to sustain permanent damage; this is more common in biomedical research than in nursing research. For example, new drugs and surgical procedures being tested in medical studies have the potential to cause subjects permanent physical damage. Some topics investigated by nurses have the potential to cause permanent damage to subjects, emotionally and socially. Studies examining sensitive information, such as sexual behavior, child abuse, HIV-AIDS status, or drug use, can be very risky for subjects. These studies have the potential to cause permanent damage to a subject’s personality or reputation. There also are potential economic risks, such as those resulting from a decrease in job performance or loss of employment.

Certainty of Permanent Damage

In some research, such as the Nazi medical experiments and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the subjects have a certainty of experiencing permanent damage. Conducting research that has a certainty of causing permanent damage to study subjects is highly questionable, regardless of the benefits that will be gained. Frequently, the benefits gained from such a study are experienced not by the research participants, but by others in society. Studies causing permanent damage to subjects violate the fifth principle of the Nuremberg Code and probably should not be conducted (see Box 4-1).

Critical Appraisal Guidelines to Examine Protection of Human Rights in Studies

The human rights that require protection in research include the rights to (1) self-determination, (2) privacy, (3) confidentiality, (4) fair selection and treatment, and (5) protection from discomfort and harm. The guidelines that follow will assist you in critically appraising a study to ensure the protection of human rights.

Understanding Informed Consent

What is informed consent? How is informed consent obtained from research subjects and documented in the research report? Informing is the transmission of essential ideas and content from the investigator to the prospective subject. Consent is the prospective subject’s agreement to participate in a study as a subject. Every prospective subject, to the degree that he or she is capable, should have the opportunity to choose whether to participate in research (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a). Informed consent includes four elements: (1) disclosure of essential study information to the study participant; (2) comprehension of this information by the participant; (3) competence of the participant to give consent; and (4) voluntary consent of the participant to take part in the study.

Essential Information for Consent

Informed consent requires the researcher to disclose specific information to all prospective subjects. The following information is essential for obtaining informed consent from research subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a):

1. Introduction of research activities. The initial information presented to prospective subjects clearly indicates that a study is to be conducted and that they are being asked to participate as subjects.

2. Statement of the research purpose. The researcher states the immediate purpose of the research and any long-range goals related to the study.

3. Selection of research subjects. The researcher explains to prospective subjects why they were selected to participate in the study.

4. Explanation of procedures. Prospective subjects receive a complete description of the procedures to be followed and any procedures that are experimental in the study are identified.

5. Description of risks and discomforts. Prospective subjects are informed of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts (physical, emotional, social, and economic) that might result from the study.

6. Description of benefits. The investigator describes any benefits to the subjects or to other people or future patients that may reasonably be expected from the research, including any financial advantages or other rewards for participating in the study.

7. Disclosure of alternatives. The investigator discloses the appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a). For example, the researchers in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study should have informed the subjects with syphilis that penicillin was an effective treatment for the disease.

8. Assurance of anonymity and confidentiality. Prospective subjects should know the extent to which their responses and records will be kept confidential. Subjects are promised that their identity will remain anonymous in presentations and publication of the study.

9. Offering to answer questions. The researcher offers to answer any questions that the prospective subjects may have.

10. Voluntary participation. The consent form includes a statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled.

11. Option to withdraw. Subjects are informed that they may discontinue participation (withdraw from a study) at any time, without penalty or loss of benefits.

12. Consent to incomplete disclosure. In some studies, subjects are not completely informed of the study purpose because that knowledge would alter their actions. However, prospective subjects must be told when certain information is being withheld deliberately.

A consent form is a written document that includes the elements of informed consent required by U.S. DHHS (2009) and FDA (2012a) regulations. In addition, a consent form may include other information required by the institution in which the study is to be conducted or by the agency funding the study. An example of a consent form is presented in Figure 4-1. The boldface terms indicate the essential consent information.

Comprehension of Consent Information

Informed consent implies not only that the researcher has imparted information to the subjects, but also that the prospective subjects have comprehended that information. The researcher must take the time to teach the subjects about the study. The amount of information to be taught depends on the subjects’ knowledge of research and the specific research topic. Researchers need to discuss the benefits and risks of a study in detail, with examples that the potential subjects or participants can understand. Nurses often serve as patient advocates in clinical agencies and need to assess whether patients involved in research understand the purpose and potential risks and benefits of their participation in a study (ANA, 2001; Banner & Zimmer, 2012; Fry et al., 2011).

Competence to Give Consent

Autonomous persons, who are capable of understanding the benefits and risks of a proposed study, are competent to give consent. Persons with diminished autonomy because of legal or mental incompetence or confinement to an institution frequently are not legally competent to consent to participate in research (see earlier, “Right to Self-Determination”). In the research report, investigators need to indicate the competence of the subjects and the process that was used for obtaining informed consent (Banner & Zimmer 2012; U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012a).

Voluntary Consent

Voluntary consent means that the prospective subject has decided to take part in a study of his or her own volition, without coercion or any undue influence (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Researchers obtain voluntary consent after the prospective subject receives the essential information about the study and has demonstrated comprehension of this information. All these elements of informed consent need to be documented in a consent form and discussed in the research report.

Documentation of Informed Consent

The documentation of informed consent depends on (1) the level of risk involved in the study and (2) the discretion of the researcher and those reviewing the study for institutional approval. Most studies require a written consent form that the subject signs, although in some studies, the requirement for written consent is waived. Nurses may be asked to identify subjects for studies, obtain consent forms for studies, collect study data, or participate in an IRB to review the ethics of a study. As a result, you need to be aware of the process for documenting informed consent in research.

Written Signed Consent Waived

The requirements for written signed consent may be waived in research that “presents no more than minimal risk of harm to subjects and involves no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside of the research context” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.117c). For example, researchers using questionnaires to collect relatively harmless data do not require a signed consent form from the subjects. Therefore, the subjects’ completion of the questionnaire online or through the mail may serve as consent. The top of the questionnaire might contain a statement such as, “Your completion of this questionnaire indicates your consent to participate in this study.”

Written signed consent also is waived in a situation in which “the only record linking the subject and the research would be the consent document and the principal risk would be potential harm resulting from a breach of confidentiality. Each subject will be asked whether he or she wants documentation linking them with the research, and the subject’s wishes will govern” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.117c). In this situation, subjects are given the option to sign or not sign a consent form that links them to the research. The four elements of consent—disclosure, comprehension, competency, and voluntariness—are essential in all studies, whether written signed consent is waived or required.

Written Short Form Consent Documents

The short form consent document includes the following statement: “The elements of informed consent required by Section 46.116 (see earlier, “Essential Information for Consent”) have been presented orally to the subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.117a). The researcher must develop a written summary of what is to be said to the subject in the oral presentation, and an IRB must approve the summary. When the researcher makes the oral presentation to the subject or to the subject’s representative, a witness is required. The subject or representative must sign the short form consent document. “The witness shall sign both the short form and a copy of the summary, and the person actually obtaining consent shall sign a copy of the summary” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.117a). Copies of the summary and short form are given to the subject and witness, and the researcher retains the original documents. The researcher must keep these documents for 3 years. The short form written consent documents typically are used in studies that present minimal or moderate risk to the subjects.

Formal Written Consent Document

The formal written consent document includes the elements of informed consent required by U.S. DHHS (2009) and FDA (2012a) regulations (see earlier, “Essential Information for Consent”). The consent form can be read by the subject or read to the subject by the researcher; however, it is also prudent to explain the study to the subject. The form is signed by the subject and witnessed by the investigator or research assistant collecting the data (see example consent form in Figure 4-1). This type of consent can be used for any type of study, from minimal risk to high risk. All persons signing the consent form—including the subject, researcher, and any witnesses—must receive a copy of it. The original consent form is kept by the researcher for a period of 3 years.

Studies that involve subjects with diminished autonomy require a written signed consent form. If these prospective subjects have some comprehension of the study and agree to participate as subjects, they must sign the consent form. However, the subject’s legally authorized representative must sign the form. The representative indicates his or her relationship with the subject under the signature (see Figure 4-1). Sometimes nurses are asked to sign a consent form as a witness for a biomedical study. They must know the study purpose and procedures and the subject’s comprehension of the study before signing the form. To ensure the consistent implementation of the consent process, nurses and others involved in the consent process are educated about the study and consent process. Larson, Cohn, Meyer, and Boden-Albala (2009) identified problems with the lack of standardization of the informed consent process in health-related studies that leads to disparities in those participating in studies. Certain individuals elect not to participate in research because of the way the study is presented to them during the consent process. Larson and co-workers (2009, p. 95) recommended a formal educational program for researchers and those involved in the consent process “to reduce disparities in research participation by improving communication between research staff and potential participants.”

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule: Authorization for Research Uses and Disclosure

The HIPAA Privacy Rule provides people, as research subjects, with the right to authorize covered entities (healthcare provider, health plan, and healthcare clearinghouse) to use or disclose their PHI for research purposes (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). HIPAA regulates this authorization in addition to the informed consent process regulated by the U.S. DHHS (2009) and FDA (2012a). The authorization focuses on the privacy risks and states how, why, and to whom the PHI will be shared. The authorization core elements and a sample authorization form can be found online at http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/authorization.asp (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). The authorization information can be included as part of the consent form or as a separate form.

Critical Appraisal Guidelines to Examine Informed Consent in Studies

All studies require obtaining informed consent from the study participants or subjects. The consent process must meet the U.S. DHHS (2009), FDA (2012a), and HIPAA (U.S. DHHS, 2007a) regulations for the conduct of ethical research with human subjects. Research reports often discuss the consent process and identify some of the essential consent information that was provided to the potential subjects. Some mention of the consent process for that study is required, but the depth of the discussion will vary according to the research purpose and types of participants or subjects included in the study. The consent process is usually presented in the methods section under a discussion of study procedures or data collection process. The following critical appraisal guidelines will assist you in examining the consent process of a published study or for a study to be conducted in your clinical agency.

Understanding Institutional Review

In institutional review, a study is examined for ethical concerns by a committee knowledgeable about research and clinical practice. The first federal policy statement on protection of human subjects by institutional review was issued by the Public Health Service (PHS) in 1966. The statement required that research involving human subjects must be reviewed by a committee of peers or associates to confirm that (1) the rights and welfare of the persons involved were protected, (2) the appropriate methods were used to secure informed consent, and (3) the potential benefits of the investigation were greater than the risks (Levine, 1986).

In 1974, DHEW passed the National Research Act, which required that all research involving human subjects undergo institutional review. The DHHS reviewed and revised these guidelines several times, with the last revision in 2009 (45 CFR, Sections 46.107-46.115). The FDA (2012b, 21 CFR, Part 56) also has very similar guidelines for institutional review of research. The regulations describe the membership, functions, and operations of the body responsible for institutional review. An institutional review board (IRB) is a committee that reviews research to ensure that the investigator is conducting the research ethically. Universities, hospitals, corporations, and many managed care centers have IRBs to promote the conduct of ethical research and protect the rights of prospective subjects at their institutions (Fry et al., 2011; Munhall, 2012b).

Each IRB has at least five members of varying backgrounds (cultural, economic, educational, gender, racial) to promote complete, scholarly, and fair review of research commonly conducted in an institution. If an institution regularly reviews studies with vulnerable subjects, such as children, neonates, pregnant women, prisoners, and the mentally disabled, the IRB must include one or more members with knowledge about and experience in working with these subjects. The members must have sufficient experience and expertise to review a variety of studies, including quantitative, qualitative, and outcomes research studies (Grove et al., 2013; Munhall, 2012b). The IRB members must not have a conflicting interest related to a study conducted in an institution. Any member having a conflict of interest with a research project being reviewed must excuse himself or herself from the review process for that study, except to provide information requested by the IRB. The IRB also must include one member whose primary concern is nonscientific, such as an ethicist, lawyer, or minister. At least one of the IRB members must be someone who is not affiliated with the institution (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012b). IRBs in hospitals often are composed of physicians, nurses, lawyers, scientists, clergy, and community laypersons.

The FDA (2012b) regulations were revised to require all IRBs to register through a system maintained by the DHHS. The registration information includes contact information for IRB members (e.g., addresses, telephone numbers, and e-mail), the number of active protocols involving FDA-regulated products reviewed during the preceding 12 months, and a description of the types of FDA-regulated products involved in the protocols reviewed (FDA, 2012b). The IRB registration requirement was implemented to make it easier for the FDA to inspect IRBs and communicate information to them. IRB registration must be renewed every 3 years and can be done online at http://ohrp.cit.nih.gov/efile.

Levels of Reviews Conducted by Institutional Review Boards

The functions and operations of an IRB involve the review of research at three different levels: (1) exempt from review, (2) expedited review, and (3) complete review. The IRB chairperson and/or committee, not the researcher, decide the level of the review required for each study. Studies usually are exempt from review if they pose no apparent risks for the research subjects. A common type of exempt study is when de-identified data from patient charts are analyzed. Nursing studies that carry no foreseeable risks for subjects often are considered exempt from review by the IRB committee.

Studies that carry some risks, which are viewed as minimal, qualify for an expedited review. Minimal risk means that “the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR, Section 46.102i). Expedited review procedures also can be used to review minor changes in previously approved research. Under expedited review procedures, the review may be carried out by the IRB chairperson or one or more experienced reviewers designated by the chairperson from among members of the IRB. In reviewing the research, the reviewers may exercise all the authority of the IRB, except disapproval of the research. A research activity may be disapproved only after a complete review of the IRB (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012b). Descriptive studies, in which subjects are asked to respond to questionnaires, commonly need only expedited review.

A study that carries greater than minimal risks must receive a complete review by an IRB. To obtain IRB approval, researchers must ensure that (1) risks to subjects are minimized, (2) risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, (3) selection of subjects is equitable, (4) informed consent will be sought from each prospective subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative, (5) informed consent will be appropriately documented, (6) the research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring data collection for subject’s safety, and (7) adequate provisions are made to protect the privacy of subjects and maintain the confidentiality of data (U.S. DHHS, 2009; FDA, 2012b).

Most studies indicate that IRB approval was obtained, but do not indicate whether the study was exempt from review, expedited review, or complete review. If a researcher is affiliated with a university, the study needs to be approved by the IRB of that university before seeking IRB approval from the clinical agency in which the study is to be conducted. In the study conducted by Cerdan and colleagues (2012, p. 132; see earlier), the researchers obtained “IRB approval at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. . . . The participants were chosen from a pediatric pulmonology outpatient clinic located in Las Vegas, Nevada.” The researchers did not identify the IRB approval from the clinic, but it might have been part of the university medical center.

If a study is conducted in more than one clinical agency, researchers must obtain IRB approval from all clinical sites in which the study is to be conducted. A research report needs to identify the IRBs that reviewed and approved a study for implementation clearly. For example, Elshatarat, Stotts, Engler, and Froelicher (2013) conducted a descriptive study of the knowledge and beliefs about smoking and goals of smoking cessation in men hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. “The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco approved this study as did the Directors of Nursing and the Chief Medical Officers of the two hospitals. All subjects provided written informed consent” (p. 127). These researchers documented IRB approval of the university and administrative approval of the two hospitals in which the study was conducted.

Influence of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule on Institutional Review Boards

Under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, an IRB or institutional established privacy board can act on requests for a waiver or an alteration of the authorization requirement for a research project. If an IRB and privacy board both exist in an agency, the approval of only one board is required; it will probably be the IRB for research projects. Researchers can choose to obtain a signed authorization form from potential subjects or can ask for a waiver or alteration of the authorization requirement. An altered authorization requirement is when an IRB approves a request that some, but not all, of the required 18 elements be removed from health information to be used in research. The researcher can also request a partial or complete waiver of the authorization requirement from the IRB. The partial waiver involves the researcher’s obtaining PHI to contact and recruit potential subjects for a study. An IRB can give a researcher a complete waiver of authorization in studies in which the requirement for a written or signed consent form was waived (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). The HIPAA regulations related to IRBs can be found online at http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/irbandprivacyrule.asp. The HIPAA Privacy Rule does not change the IRB membership and functions that are designated under the U.S. DHHS (2009) and FDA (2012b) IRB regulations.

Examining the Benefit-Risk Ratio of a Study

Nurses who serve on an IRB for their agency, serve as patient advocates when research is conducted in their agency, or are asked to collect data for a study should examine the balance of benefits and risks in studies. To determine this balance, or benefit-risk ratio, the benefits and risks associated with the sampling method, consent process, procedures, and potential outcomes of the study are assessed (Figure 4-2). Informed consent must be obtained from subjects, and selection and treatment of subjects during the study must be fair. An important outcome of research is the development and refinement of knowledge. The type of knowledge that might be obtained from the study and who will be influenced by the knowledge also need to be identified.

The type of research conducted—therapeutic or nontherapeutic—affects the potential benefits for subjects. In therapeutic research, subjects might benefit from the study procedures in areas such as skin care, range of motion, touch, and other nursing interventions. The benefits might include improved physical condition, which could facilitate emotional and social benefits. Some researchers have noted that participation in qualitative research has encouraged subjects to process and disclose thoughts regarding life-altering events, and that these actions have been beneficial to the subjects’ health and well-being (Eide & Kahn, 2008, Munhall, 2012a). Nontherapeutic nursing research does not benefit subjects directly, but is important because it generates and refines nursing knowledge for future patients, the nursing profession, and society. Most subjects involved in a study do benefit by having an increased understanding of the research process and knowing the findings from a particular study.

Examining the benefit-risk ratio also involves assessing the type, degree, and number of risks that subjects might encounter while participating in a study. The risks involved depend on the purpose of the study and procedures used to conduct the study. Risks can be physical, emotional, social, or economic and can range from no anticipated risk or mere inconvenience to certain risk of permanent damage (see earlier, “Right to Protection from Discomfort and Harm”; Fry et al., 2011; Reynolds, 1972). If the risks outweigh the benefits, the study probably is unethical and should not be conducted. If the benefits outweigh the risks, the study probably is ethical and has the potential to add to nursing’s knowledge base (see Figure 4-2; Grove et al., 2013).

Critical Appraisal Guidelines for Examining the Ethical Aspects of Studies