Clarifying Quantitative Research Designs

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Identify the nonexperimental designs (descriptive and correlational) and experimental designs (quasi-experimental and experimental) commonly used in nursing studies.

2. Critically appraise descriptive and correlational designs in published studies.

3. Describe the concepts important to examining causality—multicausality, probability, bias, control, and manipulation.

4. Examine study designs for strengths and threats to statistical conclusion, and to internal, construct, and external validity.

5. Describe the elements of designs that examine causality.

6. Critically appraise the interventions implemented in studies.

7. Critically appraise the quasi-experimental and experimental designs in published studies.

8. Examine the quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in nursing.

9. Discuss the implementation of mixed-methods approaches in nursing studies.

Comparative descriptive design, p. 216

Control or comparison group, p. 230

Cross-sectional design, p. 212

Descriptive correlational design, p. 218

Experimental or treatment group, p. 230

Experimenter expectancy, p. 228

Mixed-methods approaches, p. 243

Nonexperimental designs, p. 212

Predictive correlational design, p. 220

Quasi-experimental design, p. 232

Randomized controlled trial (RCT), p. 241

A research design is a blueprint for conducting a study. Over the years, several quantitative designs have been developed for conducting descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental studies. Descriptive and correlational designs are focused on describing and examining relationships of variables in natural settings. Quasi-experimental and experimental designs were developed to examine causality, or the cause and effect relationships between interventions and outcomes. The designs focused on causality were developed to maximize control over factors that could interfere with or threaten the validity of the study design. The strengths of the design validity increase the probability that the study findings are an accurate reflection of reality. Well-designed studies, especially those focused on testing the effects of nursing interventions, are essential for generating sound research evidence for practice (Brown, 2014; Craig & Smyth, 2012).

Being able to identify the study design and evaluate design flaws that might threaten the validity of the findings is an important part of critically appraising studies. Therefore this chapter introduces you to the different types of quantitative study designs and provides an algorithm for determining whether a study design is descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, or experimental. Algorithms are also provided so that you can identify specific types of designs in published studies. A background is provided for understanding causality in research by defining the concepts of multicausality, probability, bias, control, and manipulation. The different types of validity—statistical conclusion validity, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity—are described. Guidelines are provided for critically appraising descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental designs in published studies. In addition, a flow diagram is provided to examine the quality of randomized controlled trials conducted in nursing. The chapter concludes with an introduction to mixed-method approaches, which include elements of quantitative designs and qualitative procedures in a study.

Identifying Designs Used in Nursing Studies

A variety of study designs are used in nursing research; the four most commonly used types are descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental. These designs are categorized in different ways in textbooks (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Hoe & Hoare, 2012; Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). Sometimes, descriptive and correlational designs are referred to as nonexperimental designs because the focus is on examining variables as they naturally occur in environments and not on the implementation of a treatment by the researcher. Some of these nonexperimental designs include a time element. Designs with a cross-sectional element involve data collection at one point in time. Cross-sectional design involves examining a group of subjects simultaneously in various stages of development, levels of education, severity of illness, or stages of recovery to describe changes in a phenomenon across stages. The assumption is that the stages are part of a process that will progress over time. Selecting subjects at various points in the process provides important information about the totality of the process, even though the same subjects are not monitored throughout the entire process (Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013). Longitudinal design involves collecting data from the same subjects at different points in time and might also be referred to as repeated measures. Repeated measures might be included in descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, or experimental study designs.

Quasi-experimental and experimental studies are designed to examine causality or the cause and effect relationship between a researcher-implemented treatment and selected study outcome. The designs for these studies are sometime referred to as experimental because the focus is on examining the differences in dependent variables thought to be caused by independent variables or treatments. For example, the researcher-implemented treatment might be a home monitoring program for patients initially diagnosed with hypertension, and the dependent or outcome variable could be blood pressure measured at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months. This chapter introduces you to selected experimental designs and provides examples of these designs from published nursing studies. Details on other study designs can be found in a variety of methodology sources (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Creswell, 2014; Grove et al., 2013; Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002).

The algorithm shown in Figure 8-1 may be used to determine the type of design (descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental) used in a published study. This algorithm includes a series of yes or no responses to specific questions about the design. The algorithm starts with the question, “Is there a treatment?” The answer leads to the next question, with the four types of designs being identified in the algorithm. Sometimes, researchers combine elements of different designs to accomplish their study purpose. For example, researchers might conduct a cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational study to examine the relationship of body mass index (BMI) to blood lipid levels in early adolescence (ages 13 to 16 years) and late adolescence (ages 17 to 19 years). It is important that researchers clearly identify the specific design they are using in their research report.

Descriptive Designs

Descriptive studies are designed to gain more information about characteristics in a particular field of study. The purpose of these studies is to provide a picture of a situation as it naturally happens. A descriptive design may be used to develop theories, identify problems with current practice, make judgments about practice, or identify trends of illnesses, illness prevention, and health promotion in selected groups. No manipulation of variables is involved in a descriptive design. Protection against bias in a descriptive design is achieved through (1) conceptual and operational definitions of variables, (2) sample selection and size, (3) valid and reliable instruments, and (4) data collection procedures that might partially control the environment. Descriptive studies differ in level of complexity. Some contain only two variables; others may include multiple variables that are studied over time. You can use the algorithm shown in Figure 8-2 to determine the type of descriptive design used in a published study. Typical descriptive and comparative descriptive designs are discussed in this chapter. Grove and colleagues (2013) have provided details about additional descriptive designs.

Typical Descriptive Design

A typical descriptive design is used to examine variables in a single sample (Figure 8-3). This descriptive design includes identifying the variables within a phenomenon of interest, measuring these variables, and describing them. The description of the variables leads to an interpretation of the theoretical meaning of the findings and the development of possible relationships or hypotheses that might guide future correlational or quasi-experimental studies.

Comparative Descriptive Design

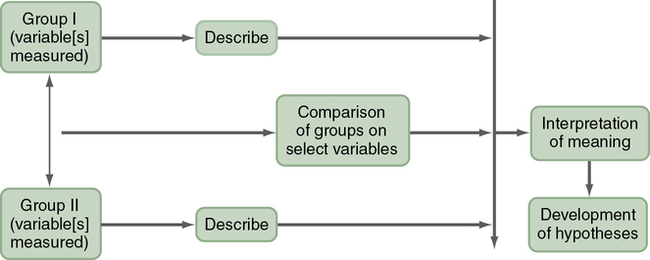

A comparative descriptive design is used to describe variables and examine differences in variables in two or more groups that occur naturally in a setting. A comparative descriptive design compares descriptive data obtained from different groups, which might have been formed using gender, age, educational level, medical diagnosis, or severity of illness. Figure 8-4 provides a diagram of this design’s structure.

Correlational Designs

The purpose of a correlational design is to examine relationships between or among two or more variables in a single group in a study. This examination can occur at any of several levels— descriptive correlational, in which the researcher can seek to describe a relationship, predictive correlational, in which the researcher can predict relationships among variables, or the model testing design, in which all the relationships proposed by a theory are tested simultaneously.

In correlational designs, a large range in the variable scores is necessary to determine the existence of a relationship. Therefore the sample should reflect the full range of scores possible on the variables being measured. Some subjects should have very high scores and others very low scores, and the scores of the rest should be distributed throughout the possible range. Because of the need for a wide variation on scores, correlational studies generally require large sample sizes. Subjects are not divided into groups, because group differences are not examined. To determine the type of correlational design used in a published study, use the algorithm shown in Figure 8-5. More details on correlational designs referred to in this algorithm are available from other sources (Grove et al., 2013; Kerlinger & Lee, 2000).

Descriptive Correlational Design

The purpose of a descriptive correlational design is to describe variables and examine relationships among these variables. Using this design facilitates the identification of many interrelationships in a situation (Figure 8-6). The study may examine variables in a situation that has already occurred or is currently occurring. Researchers make no attempt to control or manipulate the situation. As with descriptive studies, variables must be clearly identified and defined conceptually and operationally (see Chapter 5).

Predictive Correlational Design

The purpose of a predictive correlational design is to predict the value of one variable based on the values obtained for another variable or variables. Prediction is one approach to examining causal relationships between variables. Because causal phenomena are being examined, the terms dependent and independent are used to describe the variables. The variable to be predicted is classified as the dependent variable, and all other variables are independent or predictor variables. A predictive correlational design study attempts to predict the level of a dependent variable from the measured values of the independent variables. For example, the dependent variable of medication adherence could be predicted using the independent variables of age, number of medications, and medication knowledge of patients with congestive heart failure. The independent variables that are most effective in prediction are highly correlated with the dependent variable but are not highly correlated with other independent variables used in the study. The predictive correlational design structure is presented in Figure 8-7. Predictive correlational designs require the development of a theory-based mathematical hypothesis proposing variables expected to predict the dependent variable effectively. Researchers then use regression analysis to test the hypothesis (see Chapter 11).

Model Testing Design

Some studies are designed specifically to test the accuracy of a hypothesized causal model (see Chapter 7 for content on middle range theory). The model testing design requires that all concepts relevant to the model be measured and the relationships among these concepts examined. A large heterogeneous sample is required. Correlational analyses are conducted to determine the relationships among the model concepts, and the results are presented in the framework model for the study. This type of design is very complex; this text provides only an introduction to a model testing design implemented by Battistelli, Portoghese, Galletta, and Pohl (2013).

Understanding Concepts Important to Causality in Designs

Quasi-experimental and experimental designs were developed to examine causality or the effect of an intervention on selected outcomes. Causality basically says that things have causes, and causes lead to effects. In a critical appraisal, you need to determine whether the purpose of the study is to examine causality, examine relationships among variables (correlational designs), or describe variables (descriptive designs). You may be able to determine whether the purpose of a study is to examine causality by reading the purpose statement and propositions within the framework (see Chapter 7). For example, the purpose of a causal study may be to examine the effect of a specific, preoperative, early ambulation educational program on length of hospital stay. The proposition may state that preoperative teaching results in shorter hospitalizations. However, the preoperative early ambulation educational program is not the only factor affecting length of hospital stay. Other important factors include the diagnosis, type of surgery, patient’s age, physical condition of the patient prior to surgery, and complications that occurred after surgery. Researchers usually design quasi-experimental and experimental studies to examine causality or the effect of an intervention (independent variable) on a selected outcome (dependent variable), using a design that controls extraneous variables. Critically appraising studies designed to examine causality requires an understanding of such concepts as multicausality, probability, bias, control, and manipulation.

Multicausality

Very few phenomena in nursing can be clearly linked to a single cause and a single effect. A number of interrelating variables can be involved in producing a particular effect. Therefore studies developed from a multicausal perspective will include more variables than those using a strict causal orientation. The presence of multiple causes for an effect is referred to as multicausality. For example, patient diagnosis, age, presurgical condition, and complications after surgery will be involved in causing the length of hospital stay. Because of the complexity of causal relationships, a theory is unlikely to identify every element involved in causing a particular outcome. However, the greater the proportion of causal factors that can be identified and examined or controlled in a single study, the clearer the understanding will be of the overall phenomenon. This greater understanding is expected to increase the ability to predict and control the effects of study interventions.

Probability

Probability addresses relative rather than absolute causality. A cause may not produce a specific effect each time that a particular cause occurs, and researchers recognize that a particular cause probably will result in a specific effect. Using a probability orientation, researchers design studies to examine the probability that a given effect will occur under a defined set of circumstances. The circumstances may be variations in multiple variables. For example, while assessing the effect of multiple variables on length of hospital stay, researchers may choose to examine the probability of a given length of hospital stay under a variety of specific sets of circumstances. One specific set of circumstances may be that the patients in the study received the preoperative early ambulation educational program, underwent a specific type of surgery, had a particular level of health before surgery, and experienced no complications after surgery. Sampling criteria could be developed to control most of these factors. The probability of a given length of hospital stay could be expected to vary as the set of circumstances are varied or controlled in the design of the study.

Bias

The term bias means a slant or deviation from the true or expected. Bias in a study distorts the findings from what the results would have been without the bias. Because studies are conducted to determine the real and the true, researchers place great value on identifying and removing sources of bias in their study or controlling their effects on the study findings. Quasi-experimental and experimental designs were developed to reduce the possibility and effects of bias. Any component of a study that deviates or causes a deviation from a true measurement of the study variables contributes to distorted findings. Many factors related to research can be biased; these include attitudes or motivations of the researcher (conscious or unconscious), components of the environment in which the study is conducted, selection of the individual subjects, composition of the sample, groups formed, measurement methods, data collection process, data, and statistical analyses. For example, some of the subjects for the study might be taken from a unit of the hospital in which the patients are participating in another study involving high-quality nursing care or one nurse, selecting patients for the study, might assign the patients who are most interested in the study to the experimental group. Each of these situations introduces bias to the study.

An important focus in critically appraising a study is to identify possible sources of bias. This requires careful examination of the methods section in the research report, including strategies for obtaining subjects, implementing a study treatment, and performing measurements. However, not all biases can be identified from the published report of a study. The article may not provide sufficient detail about the methods of the study to detect some of the biases.

Control

One method of reducing bias is to increase the amount of control in the design of a study. Control means having the power to direct or manipulate factors to achieve a desired outcome. For example, in a study of preoperative early ambulation educational program, subjects may be randomly selected and then randomly assigned to the experimental group or control group. The researcher may control the duration of the educational program or intervention, content taught, method of teaching, and teacher. The time that the teaching occurred in relation to surgery also may be controlled, as well as the environment in which it occurred. Measurement of the length of hospital stay may be controlled by ensuring that the number of days, hours, and minutes of the hospital stay is calculated exactly the same way for each subject. Limiting the characteristics of subjects, such as diagnosis, age, type of surgery, and incidence of complications, is also a form of control. The greater the researcher’s control over the study situation, the more credible (or valid) the study findings.

Manipulation

Manipulation is a form of control generally used in quasi-experimental and experimental studies. Controlling the treatment or intervention is the most commonly used manipulation in these studies. In descriptive and correlational studies, little or no effort is made to manipulate factors in the circumstances of the study. Instead, the purpose is to examine the situation as it exists in a natural environment or setting. However, when quasi-experimental and experimental designs are implemented, researchers must manipulate the intervention under study. Researchers need to develop quality interventions that are implemented in consistent ways by trained individuals. This controlled manipulation of a study’s intervention decreases the potential for bias and increases the validity of the study findings. Examining the quality of interventions in studies is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Examining the Validity of Studies

Determining the validity of a study’s design and its findings is essential to the critical appraisal process. Study validity is a measure of the truth or accuracy of the findings obtained from a study. The validity of a study’s design is central to obtaining quality results and findings from a study. Critical appraisal of studies requires that you think through the threats to validity or the possible problems in a study’s design. You need to make judgments about how serious are these threats and how they might affect the quality of the study’s findings. Strengths and threats to a study’s validity provide a major basis for making decisions about which findings are accurate and might be ready for use in practice (Brown, 2014). Shadish and associates (2002) have described four types of validity—statistical conclusion validity, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity. Table 8-1 describes these four types of validity and summarizes the threats common to each. Understanding these types of validity and their possible threats are important in critically appraising quasi-experimental and experimental studies.

Table 8-1

Types of Validity Critically Appraised in Studies

| Types of Validity | Description | Threats to Validity |

| Statistical conclusion validity | Validity is concerned with whether the conclusions about relationships or differences drawn from statistical analysis are an accurate reflection of the real world. | Low statistical power: Concluding that there are no differences between samples when one exists (type II error), which is usually caused by small sample size. Unreliable measurement methods: Scales or physiological measures used in a study are not consistently measuring study variables. Unreliable intervention implementation: The intervention in a study is not consistently implemented because of lack of study protocol or training of individuals implementing the intervention. Extraneous variances in study setting: Extraneous variables in the study setting influence the scores on the dependent variables, making it difficult to detect group differences. |

| Internal validity | Validity is focused on determining if study findings are accurate or are the result of extraneous variables. | Subject selection and assignment to group concerns: The subjects are selected by nonrandom sampling methods and are not randomly assigned to groups. Subject attrition: The percentage of subjects withdrawing from the study is high or more than 25%. History: An event not related to the planned study occurs during the study and could have an impact on the findings. Maturation: Changes in subjects, such as growing wiser, more experienced, or tired, which might affect study results. |

| Construct validity | Validity is concerned with the fit between the conceptual and operational definitions of variables and that the instrument measures what it is supposed to in the study. | Inadequate definitions of constructs: Constructs examined in a study lack adequate conceptual or operational definitions, so the measurement method is not accurately capturing what it is supposed to in a study. Mono-operation bias: Only one measurement method is used to measure the study variable. Experimenter expectancies (Rosenthal effect): Researchers’ expectations or bias might influence study outcomes, which could be controlled by blinding researchers and data collectors to the group receiving the study intervention. |

| External validity | Validity is concerned with the extent to which study findings can be generalized beyond the sample used in the study. | Interaction of selection and treatment: The subjects participating in the study might be different than those who decline participation. If the refusal to participate is high, this might alter the effects of the study intervention. Interaction of setting and treatment: Bias exists in study settings and organizations that might influence implementation of a study intervention. For example, some settings are more supportive and assist with a study, and others are less supportive and might encourage patients not to participate in a study. Interaction of history and treatment: An event, such as closing a hospital unit, changing leadership, or high nursing staff attrition, might affect the implementation of the intervention and measurement of study outcomes, which would decrease generalization of findings. |

Statistical Conclusion Validity

The first step in inferring cause is to determine whether the independent and dependent variables are related. You can determine this relationship through statistical analysis. Statistical conclusion validity is concerned with whether the conclusions about relationships or differences drawn from statistical analysis are an accurate reflection of the real world. The second step is to identify differences between groups. There are reasons why false conclusions can be drawn about the presence or absence of a relationship or difference. The reasons for the false conclusions are called threats to statistical conclusion validity (see Table 8-1). This text discusses some of the more common threats to statistical conclusion validity that you might identify in studies, such as low statistical power, unreliable measurement methods, unreliable intervention implementation, and extraneous variances in study setting. Shadish et al. –([2002)- provide a more detailed discussion of statistical conclusion validity.

Low Statistical Power

Low statistical power increases the probability of concluding that there is no significant difference between samples when actually there is a difference (type II error). A type II error is most likely to occur when the sample size is small or when the power of the statistical test to determine differences is low (Cohen, 1988). You need to ensure that the study has adequate sample size and power to detect relationships and differences. The concepts of sample size, statistical power, and type II error are discussed in detail in Chapters 9 and 11.

Reliability or Precision of Measurement Methods

The technique of measuring variables must be reliable to reveal true differences. A measure is reliable if it gives the same result each time the same situation or factor is measured. If a scale used to measure depression is reliable, it should give similar scores when depression is repeatedly measured over a short time period (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2010). Physiological measures that consistently measure physiological variables are considered precise. For example, a thermometer would be precise if it showed the same reading when tested repeatedly on the same patient within a limited time (see Chapter 10). You need to examine the measurement methods in a study and determine if they are reliable.

Reliability of Intervention Implementation

Intervention reliability ensures that the research treatment or intervention is standardized and applied consistently each time it is implemented in a study. In some studies, the consistent implementation of the treatment is referred to as intervention fidelity (see later). If the method of administering a research intervention varies from one person to another, the chance of detecting a true difference decreases. The inconsistent or unreliable implementation of a study intervention creates a threat to statistical conclusion validity.

Extraneous Variances in the Study Setting

Extraneous variables in complex settings (e.g., clinical units) can influence scores on the dependent variable. These variables increase the difficulty of detecting differences between the experimental and control groups. Consider the activities that occur on a nursing unit. The numbers and variety of staff, patients, health crises, and work patterns merge into a complex arena for the implementation of a study. Any of the dynamics of the unit can influence manipulation of the independent variable or measurement of the dependent variable. You might review the methods section of the study and determine how extraneous variables were controlled in the study setting.

Internal Validity

Internal validity is the extent to which the effects detected in the study are a true reflection of reality rather than the result of extraneous variables. Although internal validity should be a concern in all studies, it is usually addressed in relation to studies examining causality than in other studies. When examining causality, the researcher must determine whether the dependent variables may have been influenced by a third, often unmeasured, variable (an extraneous variable). The possibility of an alternative explanation of cause is sometimes referred to as a rival hypothesis (Shadish et al., 2002). Any study can contain threats to internal design validity, and these validity threats can lead to false-positive or false-negative conclusions (see Table 8-1). The researcher must ask, “Is there another reasonable (valid) explanation (rival hypothesis) for the finding other than the one I have proposed?” Some of the common threats to internal validity, such as subject selection and assignment to groups, subject attrition, history, and maturation, are discussed in this section.

Subject Selection and Assignment to Groups

Selection addresses the process whereby subjects are chosen to take part in a study and how subjects are grouped within a study. A selection threat is more likely to occur in studies in which randomization is not possible (Grove et al., 2013; Shadish et al., 2002). In some studies, people selected for the study may differ in some important way from people not selected for the study. In other studies, the threat is a result of the differences in subjects selected for study groups. For example, people assigned to the control group could be different in some important way from people assigned to the experimental group. This difference in selection could cause the two groups to react differently to the treatment or intervention; in this case, the intervention would not have caused the differences in group outcomes. Random selection of subjects in nursing studies is often not possible, and the number of subjects available for studies is limited. The random assignment of subjects to groups decreases the possibility of subject selection being a threat to internal validity.

Subject Attrition

Subject attrition involves participants dropping out of a study before it is completed. Subject attrition becomes a threat when (1) those who drop out of a study are a different type of person from those who remain in the study or (2) there is a difference between the types of people who drop out of the experimental group and the people who drop out of the control or comparison group (see Chapter 9).

History

History is an event that is not related to the planned study but that occurs during the time of the study. History could influence a subject's response to the treatment and alter the outcome of the study. For example, if you are studying the effect of an emotional support intervention on subjects’ completion of their cardiac rehabilitation program, and several nurses quit their job at the center during your study, this historical event would create a threat to the study's internal design validity.

Construct Validity

Construct validity examines the fit between the conceptual and operational definitions of variables. Theoretical constructs or concepts are defined within the study framework (conceptual definitions). These conceptual definitions provide the basis for the operational definitions of the variables. Operational definitions (methods of measurement) must validly reflect the theoretical constructs. (Theoretical constructs were discussed in Chapter 7; conceptual and; operational definitions of variables and concepts are discussed in Chapter 5.) The process of developing construct validity for an instrument often requires years of scientific work, and researchers need to discuss the construct validity of the instruments that they used in their study (Shadish et al., 2002; Waltz et al., 2010). (Instrument construct validity is discussed in Chapter 10.) The threats to construct validity are related to previous instrument development and to the development of measurement techniques as part of the methodology of a particular study. Threats to construct validity are described here and summarized in Table 8-1.

Inadequate Definitions of Constructs

Measurement of a construct stems logically from a concept analysis of the construct by the theorist who developed the construct or by the researcher. The conceptual definition should emerge from the concept analysis, and the method of measurement (operational definition) should clearly reflect both. A deficiency in the conceptual or operational definition leads to low construct validity (see Chapter 5).

Mono-operation Bias

Mono-operation bias occurs when only one method of measurement is used to assess a construct. When only one method of measurement is used, fewer dimensions of the construct are measured. Construct validity greatly improves if the researcher uses more than one instrument (Waltz et al., 2010). For example, if pain were a dependent variable, more than one measure of pain could be used, such as a pain rating scale, verbal reports of pain, and observations of behaviors that reflect pain (crying, grimacing, and pulling away). It is sometimes possible to apply more than one measurement of the dependent variable with little increase in time, effort, or cost.

Experimenter Expectancies (Rosenthal Effect)

The expectancies of the researcher can bias the data. For example, experimenter expectancy occurs if a researcher expects a particular intervention to relieve pain. The data that he or she collects may be biased to reflect this expectation. If another researcher who does not believe the intervention would be effective had collected the data, results could have been different. The extent to which this effect actually influences studies is not known. Because of their concern about experimenter expectancy, some researchers are not involved in the data collection process. In other studies, data collectors do not know which subjects are assigned to treatment and control groups, which means that they were blinded to group assignment.

External Validity

External validity is concerned with the extent to which study findings can be generalized beyond the sample used in the study (Shadish et al., 2002). With the most serious threat, the findings would be meaningful only for the group studied. To some extent, the significance of the study depends on the number of types of people and situations to which the findings can be applied. Sometimes, the factors influencing external validity are subtle and may not be reported in research reports; however, the researcher must be responsible for these factors. Generalization is usually narrower for a single study than for multiple replications of a study using different samples, perhaps from different populations in different settings. Some of the threats to the ability to generalize the findings (external validity) in terms of study design are described here and summarized in Table 8-1.

Interaction of Selection and Treatment

Seeking subjects who are willing to participate in a study can be difficult, particularly if the study requires extensive amounts of time or some other investment by subjects. If a large number of persons approached to participate in a study decline to participate, the sample actually selected will be limited in ways that might not be evident at first glance. Only the researcher knows the subjects well. Subjects might be volunteers, “do-gooders”, or those with nothing better to do. In this case, generalizing the findings to all members of a population, such as all nurses, all hospitalized patients, or all persons experiencing diabetes, is not easy to justify.

The study must be planned to limit the investment demands on subjects and thereby improve participation. For example, the researchers would select instruments that are valid and reliable but have fewer items to decrease subject burden. The researcher must report the number of persons who were approached and refused to participate in the study (refusal rate) so that those who examine the study can judge any threats to external validity. As the percentage of those who decline to participate increases, external design validity decreases. Sufficient data need to be collected on the subjects to allow the researcher to be familiar with the characteristics of subjects and, to the greatest extent possible, the characteristics of those who decline to participate (see Chapter 9).

Interaction of Setting and Treatment

Bias exists in regard to the types of settings and organizations that agree to participate in studies. This bias has been particularly evident in nursing studies. For example, some hospitals welcome nursing studies and encourage employed nurses to conduct studies. Others are resistant to the conduct of nursing research. These two types of hospitals may be different in important ways; thus there might be an interaction of setting and treatment that limits the generalizability of the findings. Researchers must consider this factor when making statements about the population to which their findings can be generalized.

Interaction of History and Treatment

The circumstances occurring when a study is conducted might influence the treatment, which could affect the generalization of the findings. Logically, one can never generalize to the future; however, replicating the study during various time periods strengthens the usefulness of findings over time. In critically appraising studies, you need to consider the effects of nursing practice and societal events that occur during the period of the reported findings.

Elements of Designs Examining Causality

Quasi-experimental and experimental designs are implemented in studies to obtain an accurate representation of cause and effect by the most efficient means. That is, the design should provide the greatest amount of control, with the least error possible. The effects of some extraneous variables are controlled in a study by using specific sampling criteria, a structured independent variable or intervention, and a highly controlled setting. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are also designed to examine causality and are considered by some sources to be one of the strongest designs to examine cause and effect (Hoare & Hoe, 2013; Schulz, Altman, & Moher, 2010). RCTs are discussed later in this chapter. The essential elements of research to examine causality are:

• Random assignment of subjects to groups

• Precisely defined independent variable or intervention

• Researcher-controlled manipulation of the intervention

• Researcher control of the experimental situation and setting

• Inclusion of a control or comparison group in the study

• Clearly identified sampling criteria (see Chapter 9)

• Carefully measured dependent or outcome variables (see Chapter 10)

Examining Interventions in Nursing Studies

In studies examining causality, investigators develop an intervention that is expected to result in differences in post-test measures between the treatment and control or comparison groups. An intervention might also be called a treatment or an independent variable in a study. Interventions may be physiological, psychosocial, educational, or a combination of these. The therapeutic nursing intervention implemented in a nursing study needs to be carefully designed, clearly described, and appropriately linked to the outcomes (dependent variables) to be measured in the study. The intervention needs to be provided consistently to all subjects. A published study needs to document intervention fidelity, which includes a detailed description of the essential elements of the intervention and the consistent implementation of the intervention during the study (Morrison et al., 2009; Santacroce, Maccarelli & Grey, 2004). Sometimes, researchers provide a table of the intervention content and/or the protocol used to implement the intervention to each subject consistently. A research report also needs to indicate who implemented the intervention and what training was conducted to ensure consistent intervention implementation. Some studies document the monitoring of intervention fidelity (completeness and consistency of the intervention implementation) during the conduct of the study (Carpenter et al., 2013).

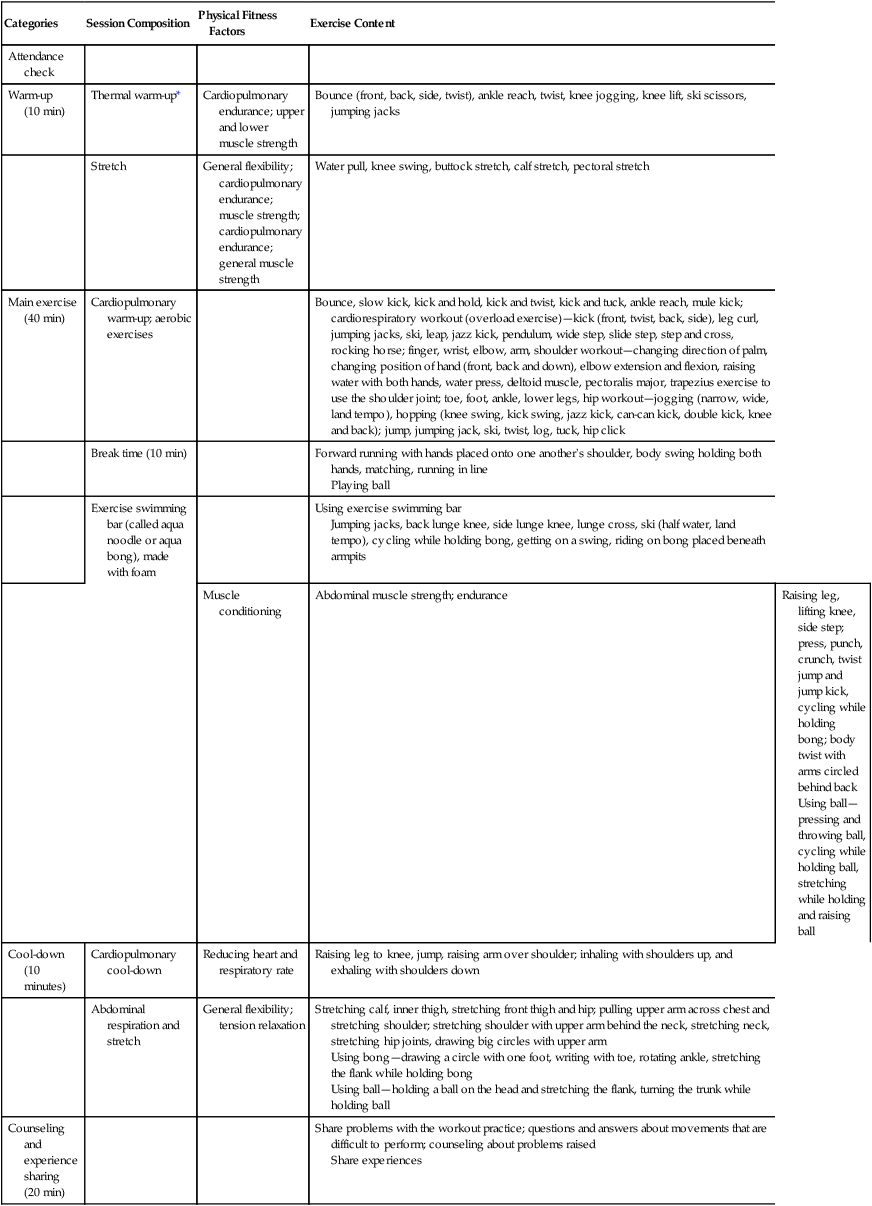

Kim, Chung, Park, and Kang (2012) implemented an aquarobic exercise program to determine its effects on the self-efficacy, pain, body weight, blood lipid levels, and depression of patients with osteoarthritis. These researchers detailed the components of their aquarobic exercise program (intervention) in a table in their published study. Table 8-2 identifies the categories, session composition, physical fitness factors, and exercise content for the exercise program to promote the consistent and complete implementation of the intervention to each of the study subjects. Kim and colleagues (2012, p. 183) indicated that “the aquarobic exercise program consisted of both patient education and aquarobic exercise. A professor of exercise physiology, medical specialist of sports medicine, professor of mental health nursing, professor of adult nursing, professor of senior nursing, and public-health nurse assessed the validity of the aquarobic exercise program.” The osteoarthritis patients were educated in the exercise program and led in the exercises by a trained instructor to promote intervention fidelity in this study. The details of the design of this quasi-experimental study are presented in the next section.

Table 8-2

Content of the Aquarobic Exercise Program

| Categories | Session Composition | Physical Fitness Factors | Exercise Content |

| Attendance check | |||

| Warm-up (10 min) | Thermal warm-up* | Cardiopulmonary endurance; upper and lower muscle strength | Bounce (front, back, side, twist), ankle reach, twist, knee jogging, knee lift, ski scissors, jumping jacks |

| Stretch | General flexibility; cardiopulmonary endurance; muscle strength; cardiopulmonary endurance; general muscle strength | Water pull, knee swing, buttock stretch, calf stretch, pectoral stretch | |

| Main exercise (40 min) | Cardiopulmonary warm-up; aerobic exercises | Bounce, slow kick, kick and hold, kick and twist, kick and tuck, ankle reach, mule kick; cardiorespiratory workout (overload exercise)—kick (front, twist, back, side), leg curl, jumping jacks, ski, leap, jazz kick, pendulum, wide step, slide step, step and cross, rocking horse; finger, wrist, elbow, arm, shoulder workout—changing direction of palm, changing position of hand (front, back and down), elbow extension and flexion, raising water with both hands, water press, deltoid muscle, pectoralis major, trapezius exercise to use the shoulder joint; toe, foot, ankle, lower legs, hip workout—jogging (narrow, wide, land tempo), hopping (knee swing, kick swing, jazz kick, can-can kick, double kick, knee and back); jump, jumping jack, ski, twist, log, tuck, hip click | |

| Break time (10 min) | Forward running with hands placed onto one another's shoulder, body swing holding both hands, matching, running in line Playing ball |

||

| Exercise swimming bar (called aqua noodle or aqua bong), made with foam |

Using exercise swimming bar Jumping jacks, back lunge knee, side lunge knee, lunge cross, ski (half water, land tempo), cycling while holding bong, getting on a swing, riding on bong placed beneath armpits |

||

| Muscle conditioning | Abdominal muscle strength; endurance | Raising leg, lifting knee, side step; press, punch, crunch, twist jump and jump kick, cycling while holding bong; body twist with arms circled behind back Using ball—pressing and throwing ball, cycling while holding ball, stretching while holding and raising ball |

|

| Cool-down (10 minutes) | Cardiopulmonary cool-down | Reducing heart and respiratory rate | Raising leg to knee, jump, raising arm over shoulder; inhaling with shoulders up, and exhaling with shoulders down |

| Abdominal respiration and stretch | General flexibility; tension relaxation |

Stretching calf, inner thigh, stretching front thigh and hip; pulling upper arm across chest and stretching shoulder; stretching shoulder with upper arm behind the neck, stretching neck, stretching hip joints, drawing big circles with upper arm Using bong—drawing a circle with one foot, writing with toe, rotating ankle, stretching the flank while holding bong Using ball—holding a ball on the head and stretching the flank, turning the trunk while holding ball |

|

| Counseling and experience sharing (20 min) | Share problems with the workout practice; questions and answers about movements that are difficult to perform; counseling about problems raised Share experiences |

*Thermal warm-up is an exercise designed to elevate the body temperature and provide muscles with more oxygen to facilitate the release of synovial fluid in the joints.

From Kim, I., Chung, S., Park, Y., & Kang, H. (2012). The effectiveness of an aquarobic exercise program for patients with osteoarthritis. Applied Nursing Research, 25(3), p. 184.

Experimental and Control or Comparison Groups

The group of subjects who received the study intervention is referred to as the experimental or treatment group. The group that is not exposed to the intervention is referred to as the control or comparison group. Although control and comparison groups traditionally have received no intervention, adherence to this expectation is not possible in many nursing studies. For example, it would be unethical not to provide preoperative teaching to a patient. Furthermore, in many studies, it is possible that just spending time with a patient or having a patient participate in activities that he or she considers beneficial may in itself cause an effect. Therefore the study often includes a comparison group nursing action.

This nursing action is usually the standard care that the patient would receive if a study were not being conducted. The researcher must describe in detail the standard care that the control or comparison group receives so that the study can be adequately appraised. Because the quality of this standard care is likely to vary considerably among subjects, variance in the control or comparison group is likely to be high and needs to be considered in the discussion of findings. Some researchers provide the experimental group with both the intervention and standard care to control the effect of standard care in the study.

Quasi-Experimental Designs

Use of a quasi-experimental design facilitates the search for knowledge and examination of causality in situations in which complete control is not possible. This type of design was developed to control as many threats to validity (see Table 8-1) as possible in a situation in which some of the components of true experimental design are lacking. Most studies with quasi-experimental designs have samples that were not selected randomly and there is less control of the study intervention, extraneous variables, and setting. Most quasi-experimental studies include a sample of convenience, in which the subjects are included in the study because they are at the right place at the right time (see Chapter 9). The subjects selected are then randomly assigned to receive the experimental treatment or standard care. The group who receives standard care is usually referred to as a comparison group versus a control group, who would receive no treatment or standard care (Shadish et al., 2002). However, the terms control group and comparison group are frequently used interchangeably in nursing studies.

In many studies, subjects from the original sample are randomly assigned to the experimental or comparison group, which is an internal design validity strength. Occasionally, comparison and treatment groups may evolve naturally. For example, groups may include subjects who choose a treatment as the experimental group and subjects who choose not to receive a treatment as the comparison group. These groups cannot be considered equivalent, because the subjects who select to be in the comparison group probably differ in important ways from those who select to be in the treatment group. For example, if researchers were implementing an intervention of an exercise program to promote weight loss, the subjects should not be allowed to select whether they are in the experimental group receiving the exercise program or the comparison group not receiving an exercise program. Subjects’ self-selecting to be in the experimental or comparison group is a threat to the internal design validity of a study.

Pretest and Post-test Designs with Comparison Group

Quasi-experimental study designs vary widely. The most frequently used design in social science research is the untreated comparison group design, with pretest and post-test (Figure 8-9). With this design, the researcher has a group of subjects who receive the experimental treatment (or intervention) and a comparison group of subjects who receive standard care.

Another commonly used design is the post-test–only design with a comparison group, shown in Figure 8-10. This design is used in situations in which a pretest is not possible. For example, if the researcher is examining differences in the amount of pain a subject feels during a painful procedure, and a nursing intervention is used to reduce pain for subjects in the experimental group, it might not be possible (or meaningful) to pretest the amount of pain before the procedure. This design incorporates a number of threats to validity because of the lack of a pretest. You can use the algorithm shown in Figure 8-11 to determine the type of quasi-experimental study design used in a published study. More details about specific designs identified in this algorithm are available from other sources (Grove et al., 2013; Shadish et al., 2002).

Experimental Designs

A variety of experimental designs, some relatively simple and others very complex, have been developed for studies focused on examining causality. In some cases, researchers may combine characteristics of more than one design to meet the needs of their study. Names of designs vary from one text to another. When reading and critically appraising a published study, determine the author’s name for the design (some authors do not name the design used) and/or read the description of the design to determine the type of design used in the study. Use the algorithm shown in Figure 8-12 to determine the type of experimental design used in a published study. More details about the specific designs identified in Figure 8-12 are available in other texts (Grove et al., 2013; Shadish et al., 2002).

Classic Experimental Pretest and Post-test Designs with Experimental and Control Groups

A common experimental design used in healthcare studies is the pretest–post-test design with experimental and control groups (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Shadish et al., 2002). This design is shown in Figure 8-13; it is similar to the quasi-experimental design in Figure 8-9, except that the experimental study is more tightly controlled in the areas of intervention, setting, measurement, and/or extraneous variables, resulting in fewer threats to design validity. The experimental design is stronger if the initial sample is randomly selected; however, most studies in nursing do not include a random sample but do randomly assign subjects to the experimental and control groups. Most studies in nursing use the quasi-experimental design shown in Figure 8-9 because of the inability to control selected extraneous and environmental variables.

Multiple groups (both experimental and control) can be used to great advantage in experimental designs. For example, one control group might receive no treatment, another control group might receive standard care, and another control group might receive a placebo or intervention with no effect like a sugar pill in a drug study. Each one of multiple experimental groups can receive a variation of the treatment, such as a different frequency, intensity, or duration of nursing care measures. For example, different frequency, intensity, or duration of massage treatments might be implemented in a study to determine their effect(s) on patients’ muscle pain. These additions greatly increase the generalizability of study findings when the sample is representative of the target population and the sample size is strong.

Post-test–Only with Control Group Design

The experimental post-test–only control group design is also frequently used in healthcare studies when a pretest is not possible or appropriate. This design is similar to the design in Figure 8-13, with the pretest omitted. The characteristics of the experimental and control groups are usually examined at the start of the study to ensure that the groups are similar. The lack of a pretest does, however, increase the potential for error that might affect the findings. Additional research is recommended before generalization of findings. Ryu, Park, and Park (2012) conducted an experimental study with post-test–only control group design that is presented here as an example.

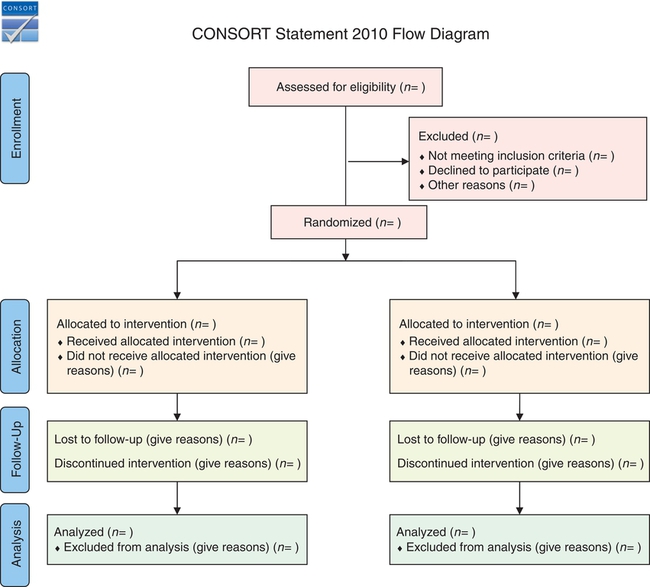

Randomized Controlled Trials

Currently, in medicine and nursing, the randomized controlled trial (RCT) is noted to be the strongest methodology for testing the effectiveness of a treatment because of the elements of the design that limit the potential for bias. Subjects are randomized to the treatment and control groups to reduce selection bias (Carpenter et al., 2013; Hoare & Hoe, 2013; Schulz et al., 2010). In addition, blinding or withholding of study information from data collectors, participants, and their healthcare providers can reduce the potential for bias. RCTs, when appropriately conducted, are considered the gold standard for determining the effectiveness of healthcare interventions. RCTs may be carried out in a single setting or in multiple geographic locations to increase sample size and obtain a more representative sample.

The initial RCTs conducted in medicine demonstrated inconsistencies and biases. Consequently, a panel of experts—clinical trial researchers, medical journal editors, epidemiologists, and methodologists—developed guidelines to assess the quality of RCTs reports. This group initiated the Standardized Reporting of Trials (SORT) statement that was revised and became the CONsolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT). This current guideline includes a checklist and flow diagram that might be used to develop, report, and critically appraise published RCTs (CONSORT, 2012). Nurse researchers need to follow the CONSORT 2010 statement recommendations in the conduct of RCTs and in their reporting (Schulz et al., 2010). You might use the flow diagram in Figure 8-14 to critically appraise the RCTs reported in nursing journals. An RCT needs to include the following elements:

1. The study was designed to be a definitive test of the hypothesis that the intervention caused the defined dependent variables or outcomes.

2. The intervention is clearly described and its implementation is consistent to ensure intervention fidelity (CONSORT, 2012; Santacroce et al., 2004; Schulz et al., 2010; Yamada, Stevens, Sidani, Watt-Watson, & De Silva, 2010).

3. The study is conducted in a clinical setting, not in a laboratory.

4. The design meets the criteria of an experimental study (Schulz et al., 2010).

5. Subjects are drawn from a reference population through the use of clearly defined criteria. Baseline states are comparable in all groups included in the study. Selected subjects are then randomly assigned to treatment and comparison groups (see Figure 8-14)—thus, the term randomized controlled trial (CONSORT, 2012; Schulz et al., 2010).

6. The study has high internal validity. The design is rigorous and involves a high level of control of potential sources of bias that will rule out possible alternative causes of the effect (Shadish et al., 2002). The design may include blinding to accomplish this purpose. With blinding the patient, those providing care to the patient, and/or the data collectors are unaware of whether the patient is in the experimental group or in the control group.

7. Dependent variables or outcomes are measured consistently with quality measurement methods (Waltz et al., 2010).

8. The intervention is defined in sufficient detail so that clinical application can be achieved (Schulz et al., 2010).

9. The subjects lost to follow-up are identified with their rationale for not continuing the study. The attrition from the experimental and control groups needs to be addressed, as well as the overall sample attrition.

10. The study has received external funding sufficient to allow a rigorous design with a sample size adequate to provide a definitive test of the intervention.

Introduction to Mixed-Methods Approaches

There is controversy among nurse researchers about the relative validity of various approaches or designs needed to generate knowledge for nursing practice. Designing quantitative experimental studies with rigorous controls may provide strong external validity but sometimes have limited internal validity. Qualitative studies may have strong internal validity but questionable external validity. A single approach to measuring a concept may be inadequate to justify the claim that it is a valid measure of a theoretical concept. Testing a single theory may leave the results open to the challenge of rival hypotheses from other theories (Creswell, 2014).

As research methodologies continue to evolve, mixed-methods approaches offer investigators the ability to use the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research designs. Mixed-methods research is characterized as research that contains elements of both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Creswell, 2014; Grove et al., 2013; Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Morse, 1991; Myers & Haase, 1989).

There has been debate about the philosophical underpinnings of mixed-methods research and which paradigm best fits this method. It is recognized that all researchers bring assumptions to their research, consciously or unconsciously, and investigators decide whether they are going to view their study from a postpositivist (quantitative) or constructivist (qualitative) perspective (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Munhall, 2012).

Over the last few years, many researchers have departed from the idea that one paradigm or one research strategy is right and have taken the perspective that the search for truth requires the use of all available strategies. To capitalize on the representativeness and generalizability of quantitative research and the in-depth, contextual nature of qualitative research, mixed methods are combined in a single research study (Creswell, 2014). Because phenomena are complex, researchers are more likely to capture the essence of the phenomenon by combining qualitative and quantitative methods.

The idea of using mixed-methods approaches to conduct studies has a long history. More than 50 years ago, quantitative researchers Campbell and Fiske (1959) recommended mixed methods to measure a psychological trait more accurately. This mixed methodology was later expanded into what Denzin (1989) identified as “triangulation.” Denzin believed that combining multiple theories, methods, observers, and data sources can assist researchers in overcoming the intrinsic bias that comes from single-theory, single-method, and single-observer studies. Triangulation evolved to include using multiple data collection and analysis methods, multiple data sources, multiple analyses, and multiple theories or perspectives. Today, the studies including both quantitative and qualitative design strategies are identified as mixed-methods designs or approaches (Creswell, 2014). More studies with mixed-methods designs have been appearing in nursing journals. You need to recognize studies with mixed-methods designs and be able to appraise the quantitative and qualitative aspects of these designs critically.

Key Concepts

• A research design is a blueprint for conducting a quantitative study that maximizes control over factors that could interfere with the validity of the findings.

• Four common types of quantitative designs are used in nursing—descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental.

• Descriptive and correlational designs are conducted to describe and examine relationships among variables. These types of designs are also called nonexperimental designs.

• Cross-sectional design involves examining a group of subjects simultaneously in various stages of development, levels of educational, severity of illness, or stages of recovery to describe changes in a phenomenon across stages.

• Longitudinal design involves collecting data from the same subjects at different points in time and might also be referred to as repeated measures.

• Correlational designs are of three different types: (1) descriptive correlational, in which the researcher can seek to describe a relationship; (2) predictive correlational, in which the researcher can predict relationships among variables; and (3) the model testing design, in which all the relationships proposed by a theory are tested simultaneously.

• Elements central to the study design include the presence or absence of a treatment, number of groups in the sample, number and timing of measurements to be performed, method of sampling, time frame for data collection, planned comparisons, and control of extraneous variables.

• The concepts important to examining causality include multicausality, probability, bias, control, and manipulation.

• Study validity is a measure of the truth or accuracy of the findings obtained from a study. Four types of validity are covered in this text—statistical conclusion validity, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity.

• The essential elements of experimental research are (1) the random assignment of subjects to groups; (2) the researcher’s manipulation of the independent variable; and (3) the researcher’s control of the experimental situation and setting, including a control or comparison group.

• Interventions or treatments are implemented in quasi-experimental and experimental studies to determine their effect on selected dependent variables. Interventions may be physiological, psychosocial, education, or a combination of these.

• Critically appraising a design involves examining the study setting, sample, intervention or treatment, measurement of dependent variables, and data collection procedures.

• Randomized controlled trial (RCT) design is noted to be the strongest methodology for testing the effectiveness of an intervention because of the elements of the design that limit the potential for bias.

• As research methodologies continue to evolve in nursing, mixed-methods approaches are being conducted to use the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative research designs.