Drug Action

Pharmaceutic, Pharmacokinetic, and Pharmacodynamic Phases

Objectives

• Differentiate the three phases of drug action.

• Discuss the two processes that occur before tablets are absorbed into the body.

• Describe the four processes of pharmacokinetics.

• Explain the meaning of pharmacodynamics, dose response, maximal efficacy, receptors, and nonreceptors in drug action.

• Define the terms protein-bound drugs, half-life, therapeutic index, therapeutic drug range, side effects, adverse reaction, and drug toxicity.

• Check drugs for half-life, percentage of protein-binding effect, therapeutic range, and side effects in a drug reference book.

• Describe the nursing implications of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

Key Terms

active absorption, p. 3

adverse reactions, p. 11

agonists, p. 8

antagonists, p. 8

bioavailability, p. 4

creatinine clearance, p. 7

disintegration, p. 3

dissolution, p. 3

distribution, p. 4

duration of action, p. 7

elimination, p. 7

excipients, p. 3

first-pass effect, p. 4

free drugs, p. 5

half-life, p. 6

ligand-binding domain, p. 8

loading dose, p. 10

metabolism, p. 6

nonselective drugs, p. 8

nonspecific drugs, p. 8

onset of action, p. 7

passive absorption, p. 3

peak action, p. 7

peak drug level, p. 10

pharmaceutic phase, p. 3

pharmacodynamics, p. 7

pharmacogenetics, p. 11

pharmacokinetics, p. 3

pinocytosis, p. 4

placebo effect, p. 11

protein-binding effect, p. 4

receptor families, p. 8

side effects, p. 10

tachyphylaxis, p. 11

therapeutic index, p. 9

therapeutic range (therapeutic window), p. 9

time-response curve, p. 7

tolerance, p. 11

toxic effects, p. 11

toxicity, p. 11

trough drug level, p. 10

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Marilyn Herbert-Ashton, who updated this chapter for the eighth edition.

A tablet or capsule taken by mouth goes through three phases—pharmaceutic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic—as drug actions occur. In the pharmaceutic phase, the drug becomes a solution so that it can cross the biologic membrane. When the drug is administered parenterally by subcutaneous (subQ), intramuscular (IM), or intravenous (IV) routes, there is no pharmaceutic phase. The second phase, the pharmacokinetic phase, is composed of four processes: absorption, distribution, metabolism (or biotransformation), and excretion (or elimination). In the pharmacodynamic phase, a biologic or physiologic response results.

Pharmaceutic Phase

Approximately 80% of drugs are taken by mouth. The pharmaceutic phase (dissolution) is the first phase of drug action. In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, drugs need to be in solution so they can be absorbed. A drug in solid form (tablet or capsule) must disintegrate into small particles to dissolve into a liquid, a process known as dissolution. Drugs in liquid form are already in solution. Figure 1-1 displays the pharmaceutic phase of a tablet.

Tablets are not 100% drug. Fillers and inert substances, generally called excipients, are used in drug preparation to allow the drug to take on a particular size and shape and to enhance drug dissolution. Some additives in drugs, such as the ions potassium (K) and sodium (Na) in penicillin potassium and penicillin sodium, increase the absorbability of the drug. Penicillin is poorly absorbed by the GI tract because of gastric acid. However, by making the drug a potassium or sodium salt, penicillin can then be absorbed. Disintegration is the breakdown of a tablet into smaller particles. Dissolution is the dissolving of the smaller particles in the GI fluid before absorption. Rate of dissolution is the time it takes the drug to disintegrate and dissolve to become available for the body to absorb it. Drugs in liquid form are more rapidly available for GI absorption than are solids. Generally, drugs are both disintegrated and absorbed faster in acidic fluids with a pH of 1 or 2 rather than in alkaline fluids. Alkaline drugs would become ionized and have difficulty crossing cell membrane barriers. Both the very young and older adults have less gastric acidity; therefore, drug absorption is generally slower for those drugs absorbed primarily in the stomach.

Enteric-coated drugs resist disintegration in the gastric acid of the stomach, so disintegration does not occur until the drug reaches the alkaline environment of the small intestine. Enteric-coated tablets can remain in the stomach for a long time; therefore, their effect may be delayed in onset. Enteric-coated tablets or capsules and sustained-release (beaded) capsules should not be crushed. Crushing would alter the place and time of absorption of the drug. Food in the GI tract may interfere with the dissolution of certain drugs. Some drugs irritate the gastric mucosa, so fluids or food may be necessary to dilute the drug concentration and to act as protectants.

Pharmacokinetic Phase

Pharmacokinetics is the process of drug movement to achieve drug action. The four processes are absorption, distribution, metabolism (or biotransformation), and excretion (or elimination). The nurse applies knowledge of pharmacokinetics when assessing the patient for possible adverse drug effects. The nurse communicates assessment findings to members of the health care team in a timely manner to promote safe and effective drug therapy for the patient.

Absorption

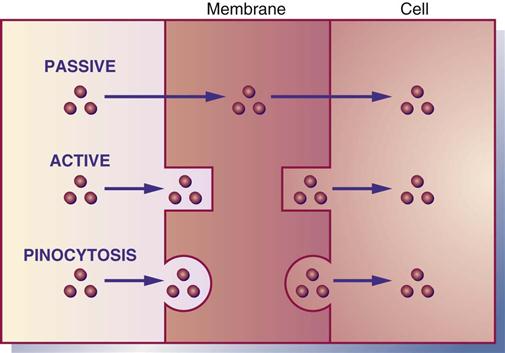

Absorption is the movement of drug particles from the GI tract to body fluids by passive absorption, active absorption, or pinocytosis. Most oral drugs are absorbed into the surface area of the small intestine through the action of the extensive mucosal villi. Absorption is reduced if the villi are decreased in number because of disease, drug effect, or the removal of small intestine. Protein-based drugs such as insulin and growth hormones are destroyed in the small intestine by digestive enzymes. Passive absorption occurs mostly by diffusion (movement from higher concentration to lower concentration). With the process of diffusion, the drug does not require energy to move across the membrane. Active absorption requires a carrier such as an enzyme or protein to move the drug against a concentration gradient. Energy is required for active absorption. Pinocytosis is a process by which cells carry a drug across their membrane by engulfing the drug particles (Figure 1-2).

The GI membrane is composed mostly of lipid (fat) and protein, so drugs that are lipid soluble pass rapidly through the GI membrane. Water-soluble drugs need a carrier, either enzyme or protein, to pass through the membrane. Large particles pass through the cell membrane if they are nonionized (have no positive or negative charge). Weak acid drugs such as aspirin are less ionized in the stomach, and they pass through the stomach lining easily and rapidly. An infant's gastric secretions have a higher pH (alkaline) than those of adults; therefore, infants can absorb more penicillin. Certain drugs such as calcium carbonate and many of the antifungals need an acidic environment to achieve greater drug absorption; thus food can stimulate the production of gastric acid. Hydrochloric acid destroys some drugs such as penicillin G; therefore a large oral dosage of penicillin is needed to offset the partial dose loss. Drugs administered by many routes do not pass through the GI tract or liver. These include parenteral drugs, eyedrops, eardrops, nasal sprays, respiratory inhalants, transdermal drugs, and sublingual drugs. Remember, drugs that are lipid soluble and nonionized are absorbed faster than water-soluble and ionized drugs.

Blood flow, pain, stress, hunger, fasting, food, and pH affect drug absorption. Poor circulation to the stomach as a result of shock, vasoconstrictor drugs, or disease hampers absorption. Pain, stress, and foods that are solid, hot, or high in fat can slow gastric emptying time, so the drug remains in the stomach longer. Exercise can decrease blood flow by causing more blood to flow to the peripheral muscle, thereby decreasing blood circulation to the GI tract.

Drugs given IM are absorbed faster in muscles that have more blood vessels (e.g., deltoids) than in those that have fewer blood vessels (e.g., gluteals). Subcutaneous tissue has fewer blood vessels, so absorption is slower in such tissue.

Some drugs do not go directly into the systemic circulation following oral absorption but pass from the intestinal lumen to the liver via the portal vein. In the liver, some drugs may be metabolized to an inactive form that may then be excreted, thus reducing the amount of active drug. Some drugs do not undergo metabolism at all in the liver, and others may be metabolized to drug metabolite, which may be equally or more active than the original drug. The process in which the drug passes to the liver first is called the first-pass effect, or hepatic first pass.

Most drugs given orally are affected by first-pass metabolism. Lidocaine and some nitroglycerins are not given orally because they have extensive first-pass metabolism and therefore most of the dose would be destroyed.

Bioavailability is a subcategory of absorption. It is the percentage of the administered drug dose that reaches the systemic circulation. For the oral route of drug administration, bioavailability occurs after absorption and first-pass metabolism. The percentage of bioavailability for the oral route is always less than 100%, but for the IV route it is 100%. Oral drugs that have a high first-pass hepatic metabolism may have a bioavailability of only 20% to 40% on entering systemic circulation. To obtain the desired drug effect, the oral dose could be higher than the drug dose for IV use.

Factors that alter bioavailability include (1) the drug form (e.g., tablet, capsule, sustained-release, liquid, transdermal patch, rectal suppository, inhalation), (2) route of administration (e.g., oral, rectal, topical, parenteral), (3) GI mucosa and motility, (4) food and other drugs, and (5) changes in liver metabolism caused by liver dysfunction or inadequate hepatic blood flow. A decrease in liver function or a decrease in hepatic blood flow can increase the bioavailability of a drug, but only if the drug is metabolized by the liver. Less drug is destroyed by hepatic metabolism in the presence of liver disorder.

With some oral drugs, rapid absorption increases the bioavailability of the drug and can cause an increase in drug concentration. Drug toxicity may result. Slow absorption can limit the bioavailability of the drug, thus causing a decrease in drug serum concentration.

Distribution

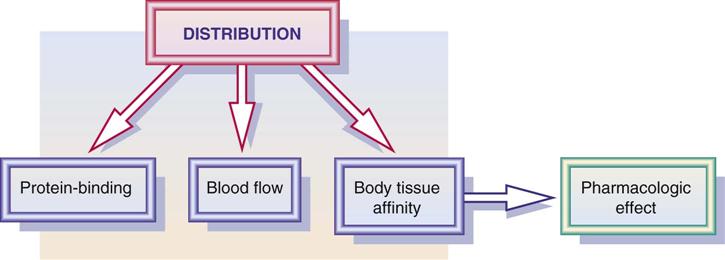

Distribution is the process by which the drug becomes available to body fluids and body tissues. Drug distribution is influenced by blood flow, the drug's affinity to the tissue, and the protein-binding effect (Figure 1-3). In addition, volume of drug distribution (Vd) is dependent on drug dose and its concentration in the body. Drugs with a larger volume of drug distribution have a longer half-life and stay in the body longer. See the section on metabolism, or biotransformation, later in this chapter.

Protein Binding

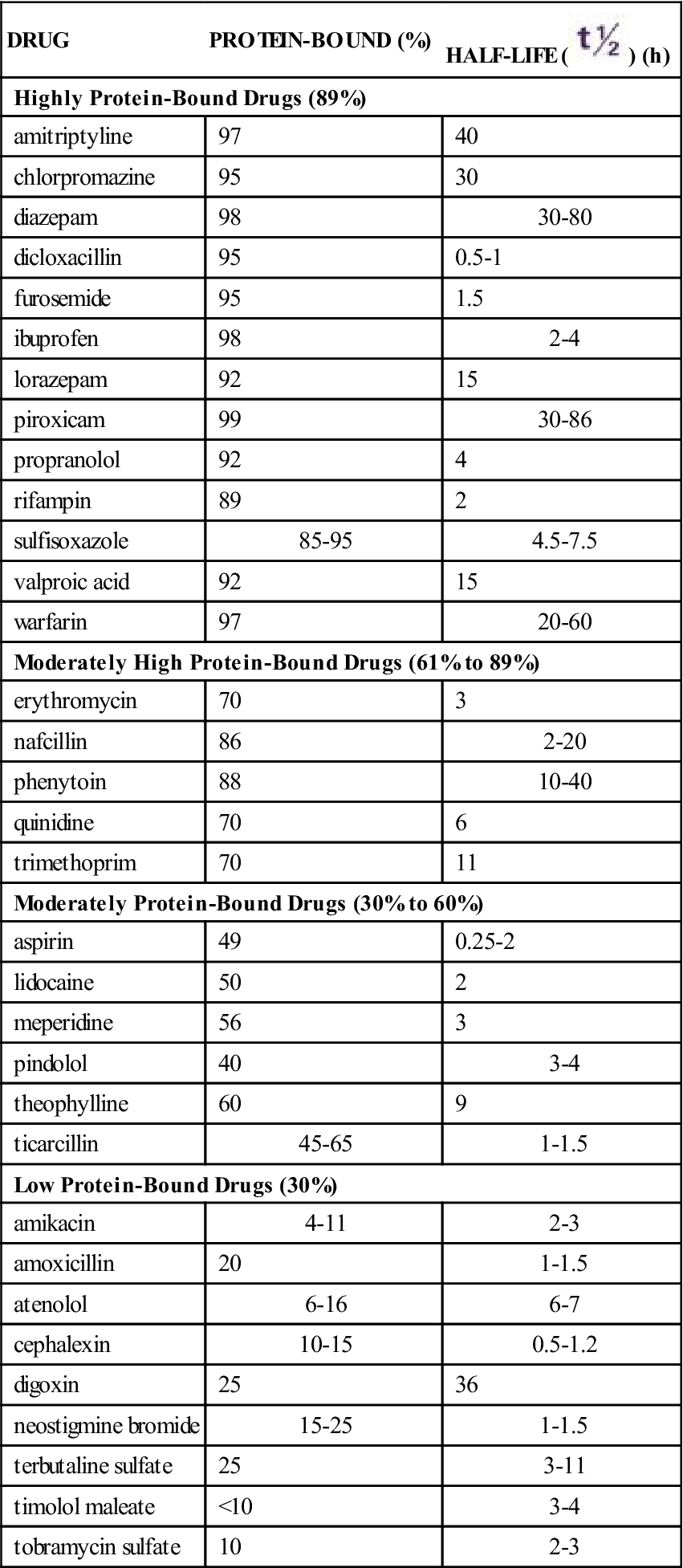

As drugs are distributed in the plasma, many are bound to varying degrees (percentages) with protein (primarily albumin). Drugs that are greater than 89% bound to protein are known as highly protein-bound drugs; drugs that are 61% to 89% bound to protein are moderately highly protein-bound; drugs that are 30% to 60% bound to protein are moderately protein-bound; and drugs that are less than 30% bound to protein are low protein-bound drugs. Table 1-1 lists selected highly protein-bound drugs and moderately highly protein-bound drugs. The portion of the drug that is bound is inactive because it is not available to receptors, and the portion that remains unbound is free, active drug. Only free drugs (drugs not bound to protein) are active and can cause a pharmacologic response. As the free drug in the circulation decreases, more bound drug is released from the protein to maintain the balance of free drug. Drugs bound to proteins cannot leave the systemic circulation to get to the site of action. This is why only free drug is active.

TABLE 1-1

PROTEIN-BINDING AND HALF-LIFE OF DRUGS

| DRUG | PROTEIN-BOUND (%) | HALF-LIFE ( ) (h) ) (h) |

| Highly Protein-Bound Drugs (89%) | ||

| amitriptyline | 97 | 40 |

| chlorpromazine | 95 | 30 |

| diazepam | 98 | 30-80 |

| dicloxacillin | 95 | 0.5-1 |

| furosemide | 95 | 1.5 |

| ibuprofen | 98 | 2-4 |

| lorazepam | 92 | 15 |

| piroxicam | 99 | 30-86 |

| propranolol | 92 | 4 |

| rifampin | 89 | 2 |

| sulfisoxazole | 85-95 | 4.5-7.5 |

| valproic acid | 92 | 15 |

| warfarin | 97 | 20-60 |

| Moderately High Protein-Bound Drugs (61% to 89%) | ||

| erythromycin | 70 | 3 |

| nafcillin | 86 | 2-20 |

| phenytoin | 88 | 10-40 |

| quinidine | 70 | 6 |

| trimethoprim | 70 | 11 |

| Moderately Protein-Bound Drugs (30% to 60%) | ||

| aspirin | 49 | 0.25-2 |

| lidocaine | 50 | 2 |

| meperidine | 56 | 3 |

| pindolol | 40 | 3-4 |

| theophylline | 60 | 9 |

| ticarcillin | 45-65 | 1-1.5 |

| Low Protein-Bound Drugs (30%) | ||

| amikacin | 4-11 | 2-3 |

| amoxicillin | 20 | 1-1.5 |

| atenolol | 6-16 | 6-7 |

| cephalexin | 10-15 | 0.5-1.2 |

| digoxin | 25 | 36 |

| neostigmine bromide | 15-25 | 1-1.5 |

| terbutaline sulfate | 25 | 3-11 |

| timolol maleate | <10 | 3-4 |

| tobramycin sulfate | 10 | 2-3 |

When two highly protein-bound drugs are given concurrently, they compete for protein-binding sites, thus causing more free drug to be released into the circulation. In this situation, drug accumulation and possible drug toxicity can result. Also, a low serum protein level decreases the number of protein-binding sites and can cause an increase in the amount of free drug in the plasma. Drug toxicity may then result. Drug dose is prescribed according to the percentage in which the drug binds to protein.

Patients with liver or kidney disease or those who are malnourished may have an abnormally low serum albumin level. This results in fewer protein-binding sites, which in turn leads to excess free drug and eventually to drug toxicity. Older adults are more likely to have hypoalbuminemia. With some health conditions that result in a low serum protein level, excess free or unbound drug goes to nonspecific tissue binding sites until needed and excess free drug in the circulation does not occur. Consequently, a decreased drug dose is needed as there is not as much protein circulated for the drug to bind to.

Some drugs bind with a specific protein component such as albumin or globulin. Most anticonvulsants bind primarily to albumin. Some basic drugs such as antidysrhythmics (e.g., lidocaine, quinidine) bind mostly to globulins.

To avoid possible drug toxicity, checking the protein-binding percentage of all drugs administered to a patient is important. The nurse should also check the patient's plasma protein and albumin levels, because a decrease in plasma protein (albumin) decreases protein-binding sites, permitting more free drug in the circulation. Depending on the drug, the result could be life-threatening.

Abscesses, exudates, body glands, and tumors hinder drug distribution. Antibiotics do not distribute well at abscess and exudate sites. In addition, some drugs accumulate in particular tissues such as fat, bone, liver, muscle, and eye tissues.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a semipermeable membrane in the central nervous system (CNS) that protects the brain from foreign substances. Highly lipid-soluble drugs are able to cross the BBB. Drugs that are not bound to proteins and are not lipid soluble are not able to cross the BBB, which makes it difficult to distribute the drug (Figure 1-4).

During pregnancy, both lipid-soluble and lipid-insoluble drugs are able to cross the placental barrier, which can affect the fetus and the mother. The risk-benefit ratio should be considered before drugs are given during pregnancy (Figure 1-5; see also Chapter 53). During lactation, drugs can be secreted into breast milk, which could affect the nursing infant. The nurse needs to check which drugs may cross into breast milk before administering to a lactating patient.

Metabolism, or Biotransformation

Metabolism is the process by which the body inactivates or biotransforms drugs. Drugs can be metabolized in several organs; however, the liver is the primary site of metabolism. Most drugs are inactivated by liver enzymes and are then converted or transformed by hepatic enzymes to inactive metabolites or water-soluble substances for excretion. A large percentage of drugs are lipid soluble; thus the liver metabolizes the lipid-soluble drug substance to a water-soluble substance for renal excretion. However, some drugs are transformed into active metabolites, causing an increased pharmacologic response. Liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatitis alter drug metabolism by inhibiting the drug-metabolizing enzymes in the liver. When the drug metabolism rate is decreased, excess drug accumulation can occur and lead to toxicity.

The half-life ( ) of a drug is the time it takes for one half of the drug concentration to be eliminated. Metabolism and elimination affect the half-life of a drug. For example, with liver or kidney dysfunction, the half-life of the drug is prolonged and less drug is metabolized and eliminated. When a drug is taken continually, drug accumulation may occur. Table 1-1 shows the half-life of selected drugs.

) of a drug is the time it takes for one half of the drug concentration to be eliminated. Metabolism and elimination affect the half-life of a drug. For example, with liver or kidney dysfunction, the half-life of the drug is prolonged and less drug is metabolized and eliminated. When a drug is taken continually, drug accumulation may occur. Table 1-1 shows the half-life of selected drugs.

A drug goes through several half-lives before more than 90% of the drug is eliminated. If the patient takes 650 mg of aspirin and the half-life is 3 hours, it takes 3 hours for the first half-life to eliminate 325 mg, 6 hours for the second half-life to eliminate an additional 162 mg, and so on until the sixth half-life (or 18 hours), when 10 mg of aspirin is left in the body (Table 1-2). A short half-life is considered to be 4 to 8 hours, and a long one is 24 hours or longer. If the drug has a long half-life (such as digoxin at 36 hours), it takes several days for the body to completely eliminate the drug.

TABLE 1-2

HALF-LIFE OF 650 mg OF ASPIRIN

NUMBER ( ) ) |

TIME OF ELIMINATION (h) | DOSAGE REMAINING (mg) | PERCENTAGE LEFT |

| 1 | 3 | 325 | 50 |

| 2 | 6 | 162 | 25 |

| 3 | 9 | 81 | 12.5 |

| 4 | 12 | 40 | 6.25 |

| 5 | 15 | 20 | 3.1 |

| 6 | 18 | 10 | 1.55 |

By knowing the half-life, the time it takes for a drug to reach a steady state of serum concentration can be computed. Administration of the drug for three to five half-lives saturates the biologic system to the extent that the intake of drug equals the amount metabolized and excreted. An example is digoxin, which has a half-life of 36 hours with normal renal function. It would take approximately 5 days to 1 week (three to five half-lives) to reach a steady state for digoxin concentration.

Excretion, or Elimination

The main route of drug elimination is through the kidneys (urine). Other routes include bile, feces, lungs, saliva, sweat, and breast milk. The kidneys filter free unbound drugs, water-soluble drugs, and drugs that are unchanged. The lungs eliminate volatile drug substances and products metabolized to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O).

The urine pH influences drug excretion. Urine pH varies from 4.5 to 8. Acidic urine promotes elimination of weak base drugs, and alkaline urine promotes elimination of weak acid drugs. Aspirin, a weak acid, is excreted rapidly in alkaline urine. If a person takes an overdose of aspirin, sodium bicarbonate may be given to change the urine pH to alkaline to promote excretion of the drug. Large quantities of cranberry juice can decrease urine pH, causing acidic urine and thus inhibiting the elimination of aspirin.

With a kidney disease that results in decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or decreased renal tubular secretion, drug excretion is slowed or impaired. Drug accumulation with possible severe adverse drug reactions can result. A decrease in blood flow to the kidneys can also alter drug excretion.

Common tests used to determine renal function are creatinine clearance (CLcr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Creatinine is a metabolic by-product of muscle that is excreted by the kidneys. The creatinine clearance test compares the level of creatinine in the urine with the level of creatinine in the blood. Creatinine clearance varies with age and gender. Lower values are expected in older adult and female patients because of their decreased muscle mass. GFR may be the best test, but it is expensive and not so commonly used. A decrease in GFR results in an increase in serum creatinine level and a decrease in urine creatinine clearance.

With renal dysfunction either in older adults or as a result of kidney disorders, drug dosage usually needs to be decreased. In these cases, the creatinine clearance needs to be determined to establish appropriate drug dosage. When the creatinine clearance is decreased, drug dosage likewise may need to be decreased. Continuous drug dosing according to a prescribed dosing regimen without evaluating creatinine clearance could result in drug toxicity.

Pharmacodynamic Phase

Pharmacodynamics is the study of the way drugs affect the body. Drug response can cause a primary or secondary physiologic effect or both. The primary effect is desirable, and the secondary effect may be desirable or undesirable. An example of a drug with a primary and secondary effect is diphenhydramine (Benadryl), an antihistamine. The primary effect of diphenhydramine is to treat the symptoms of allergy, and the secondary effect is a central nervous system depression that causes drowsiness. The secondary effect is undesirable when the patient drives a car, but at bedtime it could be desirable because it causes mild sedation.

Dose Response and Maximal Efficacy

Dose response is the relationship between the minimal versus the maximal amount of drug dose needed to produce the desired drug response. Some patients respond to a lower drug dose, whereas others need a high drug dose to elicit the desired response. The drug dose is usually adjusted to achieve the desired drug response.

All drugs have a maximum drug effect (maximal efficacy). For example, morphine and tramadol hydrochloride (Ultram) are prescribed to relieve pain. The maximum efficacy of morphine is greater than tramadol hydrochloride, regardless of how much tramadol hydrochloride is given. The pain relief with the use of tramadol hydrochloride is not as great as it is with morphine.

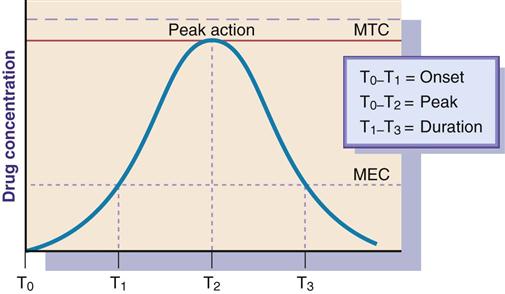

Onset, Peak, and Duration of Action

One important aspect of pharmacodynamics is knowing the drug's onset, peak, and duration of action. Onset of action is the time it takes to reach the minimum effective concentration (MEC) after a drug is administered. Peak action occurs when the drug reaches its highest blood or plasma concentration. Duration of action is the length of time the drug has a pharmacologic effect. Figure 1-6 illustrates the areas in which onset, peak, and duration of action occur.

Some drugs produce effects in minutes, but others may take hours or days. A time-response curve evaluates three parameters of drug action: the onset of drug action, peak action, and duration of action. Figure 1-6 indicates these parameters by using T (time) with subscripts (e.g., T0, T1, T2, T3).

It is necessary to understand the time response in relationship to drug administration. If the drug plasma or serum level decreases below threshold or MEC, adequate drug dosing is not achieved; too high a drug level above the minimum toxic concentration (MTC) can result in toxicity.

Receptor Theory

Drugs act through receptors by binding to the receptor to produce (initiate) a response or to block (prevent) a response. The activity of many drugs is determined by the ability of the drug to bind to a specific receptor. The better the drug fits at the receptor site, the more biologically active the drug is. It is similar to the fit of the right key in a lock. Figure 1-7 illustrates a drug binding to a receptor.

Most receptors, which are protein in nature, are found in cell membranes. Drug-binding sites are primarily on proteins, glycoproteins, proteolipids, and enzymes. There are four receptor families: (1) kinase-linked receptors, (2) ligand-gated ion channels, (3) G protein–coupled receptor systems, and (4) nuclear receptors. The ligand-binding domain is the site on the receptor at which drugs bind.

• Kinase-linked receptors. The ligand-binding domain for drug binding is on the cell surface. The drug activates the enzyme (inside the cell), and a response is initiated.

• Ligand-gated ion channels. The channel spans the cell membrane and, with this type of receptor, the channel opens, allowing for the flow of ions into and out of the cells. The ions are primarily sodium and calcium.

• G protein–coupled receptor systems. There are three components to this receptor response: (1) the receptor, (2) the G protein that binds with guanosine triphosphate (GTP), and (3) the effector that is either an enzyme or an ion channel. The system works as follows:

• Nuclear receptors. Found in the cell nucleus (not on the surface) of the cell membrane. Activation of receptors through the transcription factors is prolonged. With the first three receptor groups, activation of the receptors is rapid.

Agonists and Antagonists

Drugs that produce a response are called agonists, and drugs that block a response are called antagonists. Epinephrine (Adrenalin) stimulates beta1 and beta2 receptors, so it is an agonist. Atropine, an antagonist, blocks the histamine (H2) receptor, thus preventing excessive gastric acid secretion. The effects of an antagonist can be determined by the inhibitory (I) action of the drug concentration on the receptor site. IC50 is the antagonist drug concentration required to inhibit 50% of the maximum biological response.

Nonspecific and Nonselective Drug Effects

Many agonists and antagonists lack specific and selective effects. A receptor produces a variety of physiologic responses, depending on where in the body the receptor is located. Cholinergic receptors are located in the bladder, heart, blood vessels, stomach, bronchi, and eyes. A drug that stimulates or blocks the cholinergic receptors affects all anatomic sites of location. Drugs that affect various sites are nonspecific drugs and have properties of nonspecificity. Bethanechol (Urecholine) may be prescribed for postoperative urinary retention to increase bladder contraction. This drug stimulates the cholinergic receptor located in the bladder, and urination occurs by strengthening bladder contraction. Because bethanechol affects the cholinergic receptor, other cholinergic sites are also affected. The heart rate decreases, blood pressure decreases, gastric acid secretion increases, the bronchioles constrict, and the pupils of the eye constrict (Figure 1-8). These other effects may be either desirable or harmful. Drugs that evoke a variety of responses throughout the body have a nonspecific response.

Drugs may act at different receptors. Drugs that affect various receptors are nonselective drugs or have properties of nonselectivity. Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) acts on the norepinephrine, dopamine, acetylcholine, and histamine receptors, and a variety of responses result from action at these receptor sites. Epinephrine acts on the alpha1, beta1, and beta2 receptors (Figure 1-9). Drugs that produce a response but do not act on a receptor may act by stimulating or inhibiting enzyme activity or hormone production.

Categories of Drug Action

The four categories of drug action include (1) stimulation or depression, (2) replacement, (3) inhibition or killing of organisms, and (4) irritation. In drug action that stimulates, the rate of cell activity or the secretion from a gland increases. In drug action that depresses, cell activity and function of a specific organ are reduced. Replacement drugs such as insulin replace essential body compounds. Drugs that inhibit or kill organisms interfere with bacterial cell growth (e.g., penicillin exerts its bactericidal effects by blocking the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall). Drugs also can act by the mechanism of irritation (e.g., laxatives irritate the inner wall of the colon, thus increasing peristalsis and defecation).

Therapeutic Index and Therapeutic Range (Therapeutic Window)

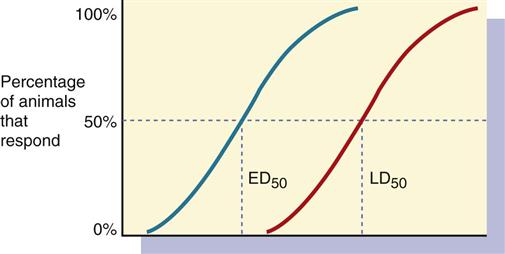

The safety of drugs is a major concern. The therapeutic index (TI) estimates the margin of safety of a drug through the use of a ratio that measures the effective (therapeutic) dose (ED) in 50% of people (ED50) and the lethal dose (LD) in 50% of people (LD50) (Figure 1-10). The closer the ratio is to 1, the greater the danger of toxicity.

In some cases, the ED may be 25% (ED25) or 75% (ED75).

Drugs with a low therapeutic index have a narrow margin of safety (Figure 1-11, A). Drug dosage might need adjustment, and plasma (serum) drug levels need to be monitored because of the small safety range between the ED and LD. Drugs with a high therapeutic index have a wide margin of safety and less danger of producing toxic effects (Figure 1-11, B). Plasma (serum) drug levels do not need to be monitored routinely for drugs with a high TI.

The therapeutic range (therapeutic window) of a drug concentration in plasma is the level of drug between the minimum effective concentration in the plasma for obtaining desired drug action and the minimum toxic concentration (the toxic effect). When the therapeutic range is given, it includes both protein-bound and unbound portions of the drug. If the therapeutic range is narrow, such as for digoxin (0.5 to 1 ng/mL), the plasma drug level should be monitored periodically to avoid drug toxicity. Monitoring the therapeutic range is not necessary if the drug is not considered highly toxic. When the therapeutic range is given, it includes both protein-bound and unbound portions of the drug. Table 1-3 lists the therapeutic ranges and toxic levels for anticonvulsants.

Peak and Trough Drug Levels

Peak drug levels indicate the rate of absorption of the drug, and trough drug levels indicate the rate of elimination of the drug. Peak and trough levels are requested for drugs that have a narrow therapeutic index and are considered toxic, such as the aminoglycoside antibiotics (Table 1-4). If either the peak or trough level is too high, toxicity can occur. If the peak is too low, no therapeutic effect is achieved. Peak drug level is the highest plasma concentration of drug at a specific time. Peak drug levels indicate the rate of absorption. If the drug is given orally, the peak time might be 1 to 3 hours after drug administration. If the drug is given IV, the peak time might occur in 10 minutes. If a peak drug level is ordered, a blood sample should be drawn at the proposed peak time, according to the route of administration.

TABLE 1-4

AMINOGLYCOSIDE ANTIBIOTICS: PEAK AND TROUGH LEVELS

| DRUG | PEAK (mcg/mL) | TROUGH (mcg/mL) | TOXIC PEAK LEVEL (mcg/mL) | TOXIC TROUGH LEVEL (mcg/mL) |

| amikacin | 15-30 | 5-10 | >35 | >10 |

| gentamicin | 5-10 | <2 | >12 | >2 |

| tobramycin | 5-10 | <2 | >12 | >2 |

The trough drug level is the lowest plasma concentration of a drug, and it measures the rate at which the drug is eliminated. Trough levels are drawn immediately before the next dose of drug is given, regardless of route of administration.

Loading Dose

When immediate drug response is desired, a large initial dose, known as the loading dose, of drug is given to achieve a rapid minimum effective concentration in the plasma. After a large initial dose, a prescribed dosage per day is ordered. Digoxin (Digitek, Lanoxicaps, Lanoxin), a digitalis preparation, requires a loading dose when first prescribed. Digitalization is the process by which the minimum effective concentration level for digoxin is achieved in the plasma within a short time.

Side Effects, Adverse Reactions, and Toxic Effects

Side effects are physiologic effects not related to desired drug effects. All drugs have desirable or undesirable side effects. Even with a correct drug dosage, side effects occur and are predicted. Side effects result mostly from drugs that lack specificity, such as bethanechol (Urecholine). In some health problems, side effects may be desirable (e.g., the use of diphenhydramine HCl [Benadryl] at bedtime when its side effect of drowsiness is beneficial). At times, however, side effects are called adverse reactions. The terms side effects and adverse reactions are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature and in speaking, but they are different. Some side effects are expected as part of drug therapy. The occurrence of these expected but undesirable side effects is not a reason to discontinue therapy. The nurse's role includes teaching patients to report any side effects. Many can be managed with dosage adjustments, changing to a different drug in the same class of drugs, or implementing other interventions. It is important to know that the occurrence of side effects is one of the primary reasons patients stop taking the prescribed medication. Adverse reactions are more severe than side effects. They are a range of untoward effects (unintended and occurring at normal doses) of drugs that cause mild to severe side effects, including anaphylaxis (cardiovascular collapse). Adverse reactions are always undesirable. Adverse effects must always be reported and documented because they represent variances from planned therapy.

Toxic effects, or toxicity, of a drug can be identified by monitoring the plasma (serum) therapeutic range of the drug. However, for drugs that have a wide therapeutic index, the therapeutic ranges are seldom given. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics and anticonvulsants, the therapeutic ranges are closely monitored. When the drug level exceeds the therapeutic range, toxic effects are likely to occur from overdosing or drug accumulation.

Pharmacogenetics

Pharmacogenetics is the scientific discipline studying how the effect of a drug action varies from a predicted drug response because of genetic factors or hereditary influence. Because people have different genetic makeup, they do not always respond identically to a drug dosage or planned drug therapy. Genetic factors can alter the metabolism of the drug in converting its chemical form to an inert metabolite; thus, the drug action can be enhanced or diminished. Some persons are less or more sensitive to drugs and their drug actions because of genetic factors. For example, African Americans do not respond as well as Caucasians to some classes of antihypertensive medications such as ACE inhibitors. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of pharmacogenetics.)

Tolerance and Tachyphylaxis

Tolerance refers to a decreased responsiveness over the course of therapy. In contrast, tachyphylaxis refers to a rapid decrease in response to the drug. In essence, tachyphylaxis is an “acute tolerance.” Drug categories that can cause tachyphylaxis include narcotics, barbiturates, laxatives, and psychotropic agents. For example, drug tolerance to narcotics can result in decreased pain relief for the patient. If the nurse does not recognize the development of drug tolerance, the patient's request for more pain medication might be interpreted as drug-seeking behavior associated with addiction. Prevention of tachyphylaxis should always be part of the therapeutic regimen (see Chapter 42).

Placebo Effect

A placebo effect is a psychological benefit from a compound that may not have the chemical structure of a drug effect. The placebo is effective in approximately one third of persons who take a placebo compound. Many clinical drug studies involve a group of subjects who receive a placebo. The nurse can increase the therapeutic effect of the drug (e.g., narcotics for pain management) but violate the truth-telling ethical principle if a nontherapeutic drug is presented as a therapeutic agent. Hence, it is required that participants in drug trials be told from the start that they might receive a placebo.

To review, the phases of drug action are pharmaceutic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic. Figure 1-12 illustrates these three phases for drugs given orally, but drugs given by injection are involved only in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phases. Nurses should be aware that tablets must disintegrate and go into solution (the pharmaceutic phase) to be absorbed.

To avoid toxic effects, the nurse must know the half-life, protein-binding percentage, normal side effects, and therapeutic ranges of the drug. This information can be obtained from drug reference books.

Key Websites

American Pharmaceutical Association: www.aphanet.org

Drug Topics: www.drugtopics.com

Pharm Web: www.pharmweb.net

Critical Thinking Case Study

The nurse is caring for JM, a patient who was admitted to the hospital with new onset of seizures. JM has been taking warfarin (Coumadin), a highly protein-bound drug that decreases blood clotting. The neurologist has ordered valproic acid (Depakote), an antiseizure medication. Valproic acid is also highly protein bound.

, half-life.

, half-life.