Chapter 75 Blepharoplasty*

1 What is blepharoplasty?

Blepharoplasty comes from two Greek words: blepharon, meaning eyelid, and plastikos, meaning fit for molding. Blepharoplasty is any procedure that is performed to shape or modify the appearance of the eyelids. It may be performed purely to remove bagginess, fatty protrusions, and lax hanging skin around the eyes or to correct a “lazy” or blepharoptotic eyelid. This last procedure is more often referred to as blepharoptosis, or more simply a “ptosis” repair. Blepharoplasty also refers to the creation of lid creases on eyelids that have little or no visible infolding and a similar operation on eyelids with ill-defined or asymmetric folds.

Traditionally, blepharoplasty denotes the removal of skin and perhaps a sliver of muscle from the upper lids, together with protruding or excessive orbital fat. On the lower lid, blepharoplasty suggests an elevation of skin or skin-muscle flaps and removal of skin, muscle, and/or fat, or more recently the removal of a sliver of skin without raising a flap.

2 What is the difference between blepharochalasis and blepharodermatochalasis (dermatochalasis)? Between steatoblepharon and blepharoptosis?

True blepharochalasis, a rare inherited disorder that appears in childhood, is characterized by repetitive episodes of eyelid edema that eventually lead to attenuation and/or dehiscence of the levator aponeurosis with resultant ptosis. The periorbital tissues stretch out, and dehiscence of the canthal tendons sometimes occurs. More often blepharochalasis refers to the stretching of the skin of the eyelids associated with aging. A more accurate term for involutional loosening of the eyelid skin is dermatochalasis. The puffiness of fat that is either excessive or protruding through a lax septum is steatoblepharon. Blepharoptosis is drooping of the upper eyelid. When the eyebrow is ptotic, juxta brow skin, lid fat, together with the eyelid skin, hangs over the margin and may cause the illusion of ptosis when the eyelid occupies a normal position. The proper term for this condition is pseudoblepharoptosis.

3 Is blepharoplasty the procedure of choice for brightening and refreshing the eye region?

Since its inception, traditional blepharoplasty has been touted as the procedure to brighten and refresh the eye region. Commonly it fails miserably in this quest. Failure comes from five sources:

Only in unusual adults with superb lower lid tonicity is lower lid blepharoplasty indicated without an accompanying effective canthopexy and/or lid shortening procedure. In all other patients the effect of lower blepharoplasty is to create vertical dystopia, drop lid posture, increase scleral show, and sadden the patient’s appearance. Unfortunately, patients requesting blepharoplasty who satisfy these criteria of superb lid tonicity are few and far between.

4 What is compensated brow ptosis?

In considering the upper face, understanding the concept of compensated brow ptosis is absolutely essential. Most people presenting for blepharoplasty have a resting position of the eyebrow that is far too low for effective and/or comfortable forward and lateral vision. It is also too low for optimal aesthetics. People remedy this situation by constant contraction of the frontalis muscle whenever the eyes are open. This muscle activation is continuous for 16 to 18 hours per day. Removal and/or invagination of overhanging eyelid tissues from the upper lids partially or totally relaxes the brow-elevating musculature, depending on how much vision-obstructing tissue was removed or displaced. Frontalis muscle activation checks the descent of the eyebrow and lid skin at a point just short of visual interference or weighty discomfort of the lids. Upper blepharoplasty (tissue excision and/or lid invagination in people with compensated brow ptosis) allows the eyebrow to position itself lower in the resting eye-open posture after surgery without visual interference or weighty discomfort, compared with the preoperative position. The usual result is an operated lid with precisely the same amount of overhang as before surgery, leading to a second or even a third redo, with yet more upper lid tissue excision. The result is a postoperative patient who looks older, more tired, and angry as well.

Only in people with an adequately high resting position of the brow in the eye closed–forehead relaxed position and little to no compensated brow ptosis is isolated upper blepharoplasty a procedure of choice for brightening and refreshing the eye region. Blepharoplasty without brow lifting can also be of benefit in people with so much overhang that they can’t raise their brows enough to clear their vision. In all other situations the brow lift is either the preferred operation or an essential companion to blepharoplasty.

5 If blepharoplasty is not the procedure of choice, what is?

Coronocanthopexy is the basic foundation for aesthetic repair around the orbital region without deforming the lids, the periorbital aesthetics, or the aperture shape. This is a forehead lift with accompanying canthopexy, at the minimum securing the tendon and associated retinacular tissues into the orbital rim periosteum but preferably into the bone, with a second layer of orbicularis support. This is secured to the bone and temporalis fascia more laterally. Such an operation maintains normal healthy eyelids without sacrificing any of the precious and irreplaceable eyelid tissue. Dropped posture of the lower lids, due to attenuation of the canthal tendon and reduced lid tonicity, is commonly responsible for what appears to be excessive lower lid skin. Canthopexy restores position, tone, and the youthful upward tilt to the eye, whereas blepharoplasty (including transconjunctival fat removal) adds downward cicatricial traction to an already weakened eyelid. This lowers the lid posture and imparts a saddened appearance along with a shortened aperture length. When a secure canthopexy with long-lasting tone restoration accompanies blepharoplasty, whatever tissue is truly excessive can be removed without adversely altering the shape of the eye. Elevation and tightening of the lid also tighten the orbital septum and add restraint to bulging fat. The canthopexy can be extended into a midcheek lift with yet further improvement in outcome.

The key effect of a frontal lift is to check the brow against precipitous descent after blepharoplasty, which makes the eye look older, more tired, and angry (due to the relaxed frontalis ceasing its pull against the corrugator activity). When the eyebrow is properly positioned, the eye appearance morphs into a youthful version of the same patient. Coronocanthopexy often eliminates the need to resect lid skin. If redundant or excessive skin remains when the brow is examined preoperatively (positioning it at its estimated post browlift posture), a simple excision of skin (with or without a tiny sliver of orbicularis) just above the supratarsal crease suffices to create the desired correction. With the lateral brow properly positioned, extending the lid excisions beyond the edge of the orbital rim rarely is necessary. If excessive upper lid skin is obvious with the brow manually raised to its estimated postoperative position, such a conservative excision can then accompany the forehead lift.

6 What is the youngest age at which a patient should consider blepharoplasty?

A functional blepharoplasty is indicated sometimes within the first few weeks of life if the upper eyelids block the infant’s vision, as in severe cases of congenital blepharoptosis. If one or both eyelids block the child’s vision, normal visual pathways may not develop, leading to irreversible visual loss in one or both eyes. This phenomenon is called amblyopia. In epiblepharon, an anomaly common in young Asian children, the lower lid eyelashes are in contact with the cornea. Surgery may be required to correct this deformity. Cosmetic blepharoplasty also may be considered in children and young teenagers of Asian ancestry with heavily pseudoblepharoptotic lids, where lid folds need to be created. In general, it is preferable to wait until a person is old enough to cooperate under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation.

7 Is the preaponeurotic fat continuous with the deeper orbital fat?

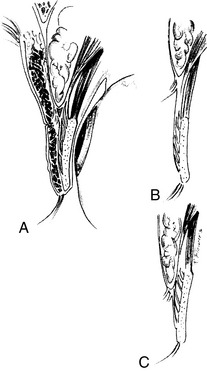

Yes. The preaponeurotic fat is an important landmark during blepharoplasty and blepharoptosis surgery. It is often the first fat encountered in making an incision through the orbicularis muscle and orbital septum, but beware. In some people, especially those with sunken-in upper lids, the sling, composed of septum connecting caudally with the aponeurosis, fuses higher than expected. In these people no fat buffer zone will be encountered to help identify the vulnerable lid opening structures. Often excessive bits of this preaponeurotic fat beg for removal during upper blepharoplasty. In the upper lid it is the lateral fat that is contained within this septo-aponeurotic sling. The white or medial fat compartment is medial to this upwardly directed sling. It is because the aponeurosis of the levator muscle is located immediately posterior to this orbital fat that it is called preaponeurotic fat. All of it is in continuity with the deeper orbital fat (Fig. 75-1).

Figure 75-1 Upper eyelid anatomy. A, Note fusion of the levator aponeurosis and orbital septum to form the septoaponeurotic vehicle that serves as a ball-bearing mechanism for eyelid opening and closure. Sympathetically innervated Müller’s muscle inserts into the superior tarsus. B, C, The septum and aponeurosis may fuse at variable levels in the eyelid. In Caucasians the attachment usually is higher, whereas in Asians it usually is more inferior.

8 Is it important to remove most of the fat from the lateral or central-lateral upper eyelid during blepharoplasty?

No. The contrary is true. The central-lateral fat, together with its sheath, provides a “ball-bearing” mechanism for the septoaponeurotic vehicle, which serves an important function during eyelid opening and closure. Excessive or aggressive removal of central fat may produce scarring capable of interfering with lid opening and result in blepharoptosis or lagophthalmos. Most people have a deep, hollowed-out area between the medial and lateral (central-lateral) compartments in the upper orbit. Loss of fat worsens this deformity and creates excessively deep-set upper lids or a superior sulcus deformity.

9 What structure is often mistaken for fat in the upper eyelid?

The lacrimal gland. Look for its grayish coloration and texture differences. Its lobular character is more compact than fat. Be careful when removing fat from the lateral portion of the upper lid. Injury to the lacrimal gland may result in dryness of the eyes and the possible need for permanent use of artificial tears and lubricating ointments. If the gland is abnormally large, it is far better to tuck the gland beneath the orbital rim with one or more sutures, anchoring its capsule to the deep periosteum, than to resect the gland itself. Know that the septoaponeurotic sling descends lower laterally, making it easier to enter at this location. However, many Caucasians and some Asians have high fusion points of the septum and aponeurosis, allowing an unwary surgeon’s dissection to transect the aponeurosis and enter into Müller’s muscle and conjunctiva without first encountering lateral fat.

10 Does removal of the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland have any deleterious consequences? What about the orbital lobe?

Removal of either the palpebral or orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland may adversely affect tear secretion. The lacrimal gland is divided into the palpebral and orbital portions by the lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis. The ducts for secretion of tears travel from the orbital lobe through portions of the palpebral lobe to reach the superior lateral fornix. Therefore cutting into or removing the palpebral lobe may decrease tearing by severing ducts and interrupting the passage of tears. Injury or removal of the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland may adversely affect the secretion of tears by eliminating secretomotor innervation to both the orbital and palpebral lobes. Resist the temptation to resect parts of the gland.

11 What is a retrobulbar hemorrhage? What are the common causes and possible consequences?

A retrobulbar hemorrhage is bleeding that occurs posterior to the orbital septum or globe in sufficient quantity to exert pressure on the globe. It may result from trauma, orbital surgery, and especially the removal of fat during blepharoplasty. It also occurs as a result of injection of anesthetic in the retroseptal space and of frontal (brow) lifting with violation of the orbital septum during dissection, allowing scalp bleeding to enter the orbit. Orbital hemorrhage is much more common in hypertensive patients, in normotensive patients with intraoperative elevation of blood pressure, and in patients who use aspirin or other medications with anticoagulant properties. The risk of retrobulbar hemorrhage can be minimized by controlling pain and blood pressure preoperatively and intraoperatively, by precisely cauterizing all fat “mesentery” and vessels before transecting them (preferably by forceps coagulation rather than Colorado needle coagulation), and by using blunt-tip needles for deep orbital anesthesia. Except in severe exophthalmos, all significant retrobulbar hemorrhage usually causes visible protrusion of the globe.

Too much pressure on the globe may lead to irreversible loss of vision. The intraocular pressure at first remains within the normal range but may increase rapidly if the cause goes untreated. Normal intraocular pressure is 10 to 22 mm Hg. Pressures of 30 to 40 mm Hg should sound an alarm and motivate the surgical team to control contributing factors immediately. Intraocular pressure greater than 40 mm Hg represents real risk of visual compromise and demands immediate treatment. Intraocular pressures approaching diastolic levels put the eye in imminent danger of vein occlusion or retinal or nerve infarction, causing severe or total loss of vision. We strongly recommend that surgeons performing blepharoplasty and other orbital surgery have tonometry devices available during surgery.

12 How is a retrobulbar hemorrhage treated?

Treatment requires prompt recognition followed by measures to decrease pressure on the globe. Prompt control of pain and blood pressure elevation are often the most pressing needs, with application of light intermittent pressure on the orbit until these factors are controlled. A blunt instrument placed into the orbit through an existing incision may allow some blood to drain. Maximal exposure and illumination are essential in attempting to identify and cauterize the offending vessel, which often cannot be located. Lateral cantholysis may be necessary to allow the orbital tissues and eyelids to bulge forward to decrease the orbital pressure transmitted to the globe. Some physicians recommend the immediate use of mannitol or acetazolamide (Diamox) to lower the intraocular pressure.

Immediately after recognizing the condition, during or after a blepharoplasty or blepharoptosis surgery, reopen the incision and orbital septum, and drain the orbit with a blunt instrument. Monitor progress by taking tonometry readings. Another technique involves using a hemostat to create an opening in the orbital floor to decompress the orbit emergently. This technique is rarely indicated unless all other maneuvers fail. Anterior chamber decompression is not indicated.

13 What are the advantages and disadvantages of a transconjunctival blepharoplasty?

Transconjunctival incisions are useful lower eyelid surgical approaches when only fat (steatoblepharon) removal or orbital septum tightening with little or no removal of skin (minimal dermatochalasis) is required. Resultant scarring still exerts downward traction on the lower lid, although typically less than with skin or skin-muscle flap approaches. The incisions are within the lower conjunctival sac, going through the lower lid retractors to gain access to the lower eyelid fat. One clear advantage is the absence of visible external incisions, but conjunctival hemorrhage is commonly greater and hinders cosmetic concealment. Disadvantages include occasional difficulty in locating the proper tissue planes to identify the fat in respective compartments; inability to reduce lower eyelid skin; inability to tighten lower eyelid laxity, which usually is present; increased risk of injury to the inferior oblique muscle by inexperienced probing; and postoperative downward lid traction that can be both profound and surprising. Also, when the fatty bulge is eliminated, excessive skin will cause visible redundancy.

14 What effect does blepharoplasty or tissue removal from the upper eyelid have on the position of the eyebrows?

Most people requesting upper eyelid surgery have significant compensated eyebrow ptosis, that is, they must contract the frontalis muscle to effect comfortable, unobstructed forward and lateral vision. A clue to this condition may be transverse forehead creasing or corrugation, but young people and other individuals with lots of subcutaneous padding may telescope the skin when the frontalis muscle contracts and show no transverse wrinkling. In all people with compensated brow ptosis, the brow posture drops after upper blepharoplasty. Patients themselves often fail to see it because they automatically and subconsciously raise their brows and tilt their head backward when looking in a mirror, when facing a camera, or when under careful scrutiny. Therefore, all patients require a careful preoperative evaluation that compares the eye-closed, head vertical, and nontilted brow in a relaxed resting (uncompensated) position with the corresponding eye-open compensated elevated brow position. Full relaxation of the brow usually is best achieved with the eyes closed. The position of the eyebrows with the eyes closed and the forehead relaxed is the position toward which the eyebrows will drop after an upper lid blepharoplasty when no concurrent procedure is performed to secure proper eyebrow position, thereby preventing significant brow descensus.

15 Does lower lid skin or skin-muscle resection change the shape of the eye? If so, how?

Resection of even a small or conservative amount of lower eyelid skin in the presence of a lax lower lid will result in aesthetically unpleasing results. Skin resection in the setting of lower eyelid laxity results in a rounded lower eyelid with increased scleral show (especially laterally), directly mirroring the triangular section of skin typically removed. This altered shape of the lower eyelid gives the patient a sadder and more tired appearance. Significant corneal and conjunctival exposure with characteristic symptoms typically accompanies lower eyelid retraction with vertical dystopia. True ectropion may occur if laxity of the lower eyelids is not addressed before or during lower eyelid blepharoplasty by some meaningful canthopexy procedure. The best approach is a secure two-layer canthopexy, even better when combined with a midcheek lift (referred to as optimaplasty or Mag 5). Good canthopexies allow more lower lid tissue resection, especially when combined with midcheek lifting, but remember that few periosteal canthopexies have long-lasting results. Significantly undercorrect skin excess when canthopexy support is limited to the periosteum.

16 What are the most common causes of postoperative eyelid ptosis?

The most common cause of postoperative ptosis is undiagnosed preoperative ptosis. Ptosis (blepharoptosis) describes a drooping of the upper eyelid. In a patient undergoing cosmetic or functional blepharoplasty, the type of ptosis most commonly encountered is due to brow ptosis, usually asymmetrically. The weight of the brow on the lower side results in ptosis, or a greater ptosis than on the less ptotic brow side. The more blepharoptotic upper eyelid usually is on the same side as the lower eyebrow. Half of these ptotic lids correct with effective brow elevation. This can be demonstrated manually preoperatively. After traditional blepharoplasty the preexisting ptosis usually is exaggerated during the first 4 to 8 weeks postoperatively. This is because edema adds weight to the lid, which exaggerates the ptosis. The next most commonly encountered ptosis is due to dehiscence of the levator aponeurosis. Another common, but operative, cause of ptosis is accidental separation of the levator aponeurosis when the orbicularis is lifted and resected. Other causes include cicatricial restriction of lid opening and closing, usually as a result of previous surgeries; excessive tissue dissection via an upper lid incision, such as corrugator muscle removal; excessive tissue removal (especially fat); hemorrhage within the surgical field; and/or inflammation.

17 How is blepharoptosis categorized?

Congenital ptosis is present at the time of birth, whereas acquired ptosis occurs after birth. These broad categories can be divided into additional types based on the specific etiology. Various terms describing both congenital and acquired varieties include dysmyogenic, myogenic, neurogenic, involutional (or senile), aponeurotic, traumatic, cicatricial, mechanical, and structural. Many of these descriptive classifications overlap; a disease process may fit under more than one category.

Myogenic (dysmyogenic) blepharoptosis, the most common congenital type, results from dysgenesis or faulty development of the levator muscle. Much of the striated muscle is replaced with fibrous tissue and sometimes fat, resulting in limited contractile ability and capacity to relax. A child with congenital myogenic ptosis may have unilateral or bilateral involvement with decreased ability to open and close the eyes. Examples of acquired myogenic ptosis include muscular diseases, such as muscular dystrophy, oculopharyngeal dystrophy, or chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO), and orbital trauma with muscle injury.

Neurogenic blepharoptosis results from faulty innervation of the upper lid retractors. Ptosis is profound with complete interruption of innervation to the levator muscle (through the superior division of the oculomotor nerve) and subtle with interruption of the sympathetic innervation to the superior tarsal (Müller’s) muscle. One example of congenital or acquired neurogenic ptosis is Horner’s syndrome with sympathetic disruption, resulting in miosis, anhidrosis of the skin, and mild blepharoptosis.

Mechanical or traumatic blepharoptosis may result from any condition that interferes with the levator muscle or its innervation.

18 What is the treatment of postsurgical lagophthalmos?

Postsurgical lagophthalmos (inability to close the eyelids completely or to cover the globe adequately on caudal gaze) is common. It often is temporary but may be permanent. Far too much skin is commonly resected with upper blepharoplasty; as a result, the patient may have skin deficiency with a temporary or permanent lagophthalmos. Usually inherent mechanisms protect against it by dropping the brow dramatically. Brow elevation surgery rarely, if ever, results in skin deficiency unless the patient had previous (typically excessive) lid skin resection(s). Local anesthesia and swelling contribute to ptosis in the immediate postoperative period by blocking the orbicularis oculi more than the levator muscle. Postoperative edema of the upper lids during the first weeks after surgery commonly interferes with normal eyelid excursion as well as with blinking and may aggravate drying of the eye. We prefer to give all patients artificial tears and/or lubricating eye ointment for routine surgical aftercare. In general, 30 mm of upper lid skin is required for a normally functioning lid with a normally positioned brow; less than this amount often requires life-long use of artificial tears, lubricants, and other measures to prevent drying. (Measure from bottom of midbrow hair to eyelash margin with the eyelid under gentle stretch.)

19 What forms the supratarsal fold?

The upper eyelid supratarsal fold is also referred to as the upper eyelid or supratarsal crease. Supratarsal implies that the fold or crease is above the superior border of the tarsus, but this is not always the case, particularly in Asians. The crease is formed by insertions of fibrous extensions of the levator aponeurosis into the muscle and/or skin. It is beneficial to reestablish or preserve these connections during blepharoplasty so that the incision is appropriately hidden within the lid crease. It is pertinent, and of interest, that the lid always creases at a line marking the caudal extent of where the sling created by the aponeurosis and septum descends into the lid. Even with no fibrous connections into the skin, a lid fold would be created by the rotary motion of this sling, which surrounds the ball-bearing–like orbital fat. If the crease is not being recreated, you should always preserve the existing supratarsal crease, even when it seems exceptionally indistinct. Make the caudal margin of any skin excision approximately 1 mm above the supratarsal crease.

20 What is the double eyelid operation often requested by Asians or people of Asian ancestry?

Most people of East Asian ancestry, including those from China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, have a visible crease on the eyelid, at least during the first 2 or 3 decades of life. In many people they are quite well formed. In others the lid folds begin to be visible only on the central to lateral part of the eyelid. Because this fold (or crease) divides the lid into two sections (i.e., the part above and the part below the crease), the eyelids are referred to as double. An eyelid with no visible crease is referred to as single. These terms are uniformly used by most persons of East Asian ancestry. Often one eyelid is double and the other is single, or one lid fold is simply much more clearly defined than the other. Most people have an understandable desire for symmetry. The many different methods of lid fold creation fall into two groups: the closed or suture technique and the open technique. The senior author (R.S. Flowers) has often used a combination of the two when a conservative lid fold was desired with minimal postoperative swelling and morbidity.

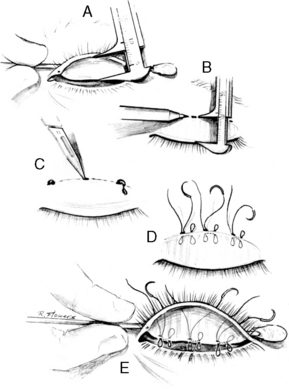

In the closed technique, three or four tiny incisions are made at the desired level of fold creation on the external lid to allow the knot of suture to disappear into the substance of the lid, with a suture closing the skin overlying it. There are many variations to this technique. The sutures secure the lid skin to the aponeurosis (Fig. 75-2).

Figure 75-2 Upper eyelid crease fixation using the closed or suture technique. A, The vertical height of the tarsus is measured. B, The superior edge of the tarsus is marked on the skin. C, Several small incisions are made along the marked line. D, E, Full-thickness nonabsorbable sutures are passed through the eyelid to create eyelid crease fixation at the superior edge of the tarsus.

(From Flowers RS: Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination: Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 20:193–207, 1993, with permission.)

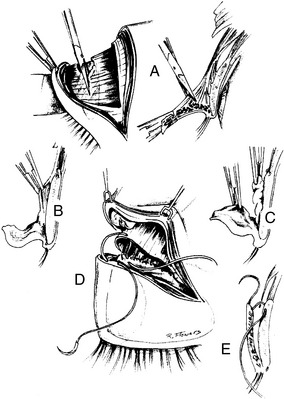

In the open technique, an incision is made across the lid. Skin and/or muscle is excised, after which the pretarsal skin flap is attached to the tarsus, the aponeurosis, or both. If the pretarsal skin height is made small, it can be attached to the conjoint tendon or the pretarsal extension of the aponeurosis. Clearing off the tarsus and tarsal attachment makes it more secure (Fig. 75-3).

Figure 75-3 Open technique of upper eyelid crease fixation. A, The orbital septum is opened, and the pretarsal extension of the aponeurosis is dissected free from the pretarsal orbicularis. B, C, Pretarsal portions of the eyelid are debulked if needed. D, E, The inferior cut edge of the aponeurosis is secured to the edge of the pretarsal skin and the superior anterior tarsus using absorbable buried sutures.

(From Flowers RS: Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination: Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 20:193–207, 1993, with permission.)

In the combination technique, skin, with or without a sliver of muscle, is removed just above the level of suture creation of the lid fold. The lid sutures are placed through the open portion of the lid, and no additional small incisions are necessary on the lid. The sutures pull the pretarsal tissue to the tarsus and secure it there.

A conservative medial epicanthoplasty is helpful in achieving a long aperture and avoiding the appearance of esotropia and/or telecanthus. It also assists in creating a lid crease that originates outside or just above the remaining small epicanthus and looks maximally normal.

21 Where is the peripheral arterial arcade of the eyelid located?

The peripheral arterial arcade is located superior to the tarsus between the levator aponeurosis and Müller’s muscle. Many of these little arteries are within the substance of Müller’s muscle where it inserts into the tarsus. Great care must be taken when placing sutures into the cephalad margins of the tarsus to avoid these vessels. Puncture leads to hemorrhage into Müller’s muscle, which occasionally causes lid ptosis that may persist for 2 or 3 months after surgery.

An arcade is also located in the lower eyelid between the inferior tarsal muscle and lower eyelid retractors. These peripheral arcades anastomose with the marginal arcades, which are located near the lid margins of both upper and lower eyelids. The marginal and peripheral arterial arcades serve as points of anastomosis between the internal and external carotid systems. These arcades receive contributions from the angular artery, which is a branch of the facial artery from the external carotid system, and from the terminal portions of the orbital artery, which arises from the internal carotid system.

22 When is a coronal lift contraindicated?

23 When is it appropriate to resect frontalis muscle?

Rarely, if ever. Sometimes a combination of both blepharoplasty and frontal lift is required to eliminate transverse forehead wrinkling, especially when brow ptosis is profound and dermatochalasis or pseudoblepharoptosis of the eyelid is advanced. Often, blepharoplasty (upper) alone or coronal lift alone (or endoscopic) causes the transverse creases to disappear.

24 Why does the medial brow commonly drop after blepharoplasty and/or elevation of the lateral brow?

The frontalis muscle inserts more effectively and consistently into the medial brow than into the lateral brow. When most people raise their eyebrows, the medial end elevates more than the lateral brow does. The need to clear up the residual lateral tissue overhang drives the frontalis contraction, causing overcorrection of the medial brow to adequately clear the lateral upper lid and/or juxtabrow tissue overhang. When lateral overhang is cleared by either blepharoplasty or lateral brow elevation (via direct excision or frontal lift), the medial brow will always drop. The cause is frontalis muscle relaxation, and it is almost always beneficial to the brow component of facial aesthetics. A negative aspect is that frontalis relaxation eliminates antagonistic pull against the corrugator, resulting in corrugator frown exaggeration.

25 How do you plan a medial epicanthoplasty?

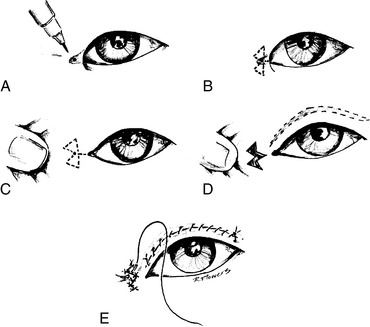

Prominent epicanthal folds are common in many people, particularly Asians. These little canopies covering the medial apertures are best corrected with a small W-shaped incision, with the wide part of the W facing laterally and the small part facing medially. The middle point of the W should be level with and point directly to the medial canthus. Placing the central point of the W 0.5 mm lateral to the desired medial extent of the aperture. After completion of the design, excision of small skin triangles from the wings of the W follows, often joined centrally by a 1- to 2-mm connecting bridge. Closure is with interrupted 6–0 monofilament sutures on a tapered needle rather than a cutting one. This is an excellent technique for removing small or large epicanthal folds, which are common to all races. We believe that the most effective approach to epicanthal folds is the Flowers modification of the Uchida “split V-W” epicanthoplasty (Fig. 75-4).

Figure 75-4 Medial epicanthoplasty. Flowers’ modification of the Uchida epicanthoplasty, which often accompanies the anchor procedure in patients of Asian ancestry. A, The central point of the W is marked 0.5 to 1 mm lateral to the desired medial exposure of the inner canthus. B, The W is drawn, varying in size with the prominence of the epicanthal fold. C, The two triangles are excised, often with a 1- to 3-mm skin bridge between them. D, The V is split down toward the medial canthus. E, The angles formed are sutured into the wing of the W with seven tiny sutures. Note that the upper arm of the W stays well above the medial extension of the lid fold incision to avoid a deforming band of contracture and a medial lid fold that is too high. Sometimes muscle and fibrous tissues contribute to the epicanthal fold and require transection before closure. The triangular flaps sometimes must be further shortened.

(From Flowers RS: Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination: Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 20:193–207, 1993, with permission.)

26 How do you avoid lash or lid eversion and areas of lid retraction associated with invagination or “double eyelid” blepharoplasty?

First of all, understand that a prominent globe predisposes toward lash eversion and lid retraction. In performing an invagination blepharoplasty, the surgeon must take care not to attach the pretarsal skin segment under excessive tension when anchoring it to the tarsus and/or aponeurosis. Tension on the pretarsal skin causes the eyelashes to evert or turn upward, giving an abnormal “surprised” appearance whether the procedure is done in Asians or Caucasians. Tension on the pretarsal skin can be adjusted by changing the level at which the skin is anchored on the tarsus (the tarsal attachment of the pretarsal skin “checks” against lash eversion). Careful measurements of the height of the tarsus and the amount of skin for resection during blepharoplasty should be part of the preoperative assessment. To avoid retraction, make sure that the septum is opened with scissors angled slightly cephalad, leaving a small tuft of septum attached to the aponeurosis to lengthen it if necessary. Another way to lengthen the aponeurosis is by making diagonal fingers in the aponeurosis, rotating them downward. This can lengthen the aponeurosis up to 4 mm. In most normal adults a minimum of 30 mm of skin between the eyebrow and eyelashes should remain to allow attractive lid contour and normal function. With the brow in its relaxed position, the amount of excessive skin overhang obscuring the pretarsal lid multiplied by two gives an approximation of how much skin needs to be removed. From 1.5 to 2 mm should be added to that pretarsal measurement to allow for the tightly stretched skin and its “U turn” heading back up to the attachment point of invagination.

27 Are wedge resections and tarsal strip canthopexies recommended procedures for tightening the lower lid?

Various techniques are available for tightening the lower lid. Traditional wedge resections shorten the aperture but fail to correct the downward migration of muscle requiring tightening for gaping ectropions, and markedly lax and elongated lower lids. Always combine wedge resections with a well-done canthopexy to restore canthal position. The tarsal strip procedure, if done properly on carefully selected patients in these groups, can prove extremely helpful. Our preferred technique for tightening the lower lid in the vast majority of patients is a canthopexy anchoring the tendon–lateral retinacular complex of the lower eyelid into the bone, just inside the lateral orbital rim. Anchoring the retinaculum into bone results in a highly effective tightening and lateral canthal lift and positional restoration. It provides permanent and secure lateral canthopexy with superb results, which still are intact and competent 20 or more years later. Wedge resections fail to correct the commonly dropped tilt of the intercanthal axis lid while shortening the lid aperture. They also commonly result in small and “beady” eyes that are difficult, if not impossible, to correct.

28 What are the pros and cons of the endoscopic forehead lift?

The main advantage of the endoscopic forehead lift is less total scar length on the scalp, which may be of particular benefit for men or even women with various balding patterns. Another advantage is a potential for less bleeding because fewer scalp vessels are cut in the process. Usually only three to five incisions measuring 1.5 to 2.0 cm are made within the hairline for endoscopic techniques.

The disadvantages of the endoscopic forehead lift are numerous. Maximal removal of the corrugator muscles, one of the most important aspects of forehead lifting, is difficult and exceptionally time-consuming endoscopically. Because of the difficulty in identifying tissue planes, the risk of injury to important motor and sensory nerves increases. The major drawback is the repertoire of important tasks that are extremely difficult, if not impossible, endoscopically. The list includes canthopexies, especially those into the bone with its commonly accompanying second layer muscle canthopexy, as well as orbital rim, root of the nose, and glabellar ostectomies. Periosteal flaps and other anchoring devices that help secure the eyebrow into its most optimal position (especially with asymmetrically ptotic brows) generally require open approaches. The endoscopic approach also does not enjoy the advantage of the coronal incision’s easy access for inserting and/or straightening nasal dorsum grafts or implants. Finally, the blind subperiosteal dissection of the endoscopic approach often leads to transection of aberrant or anomalous supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves and encourages central brow elevation and overcorrection.

An open technique allows thorough visualization of the corrugator, depressor supercilii, and procerus muscles for their modification. It also allows access to the periosteum and supraorbital cranium above the orbital rim for a whole host of other surgical possibilities, including orbital expansion, and the most secure and long-lasting canthopexy possible.

29 Are transblepharoplasty methods of corrugator muscle resection and brow elevation effective for eliminating deformity? How do they compare with other techniques?

Transblepharoplasty approaches may improve the deformity but do not compare with the effectiveness of a direct maximal excision, especially with the aid of good surgical loupes. When removal of the corrugator muscle is incomplete, other methods can be used to decrease the corrugator frown, such as repeated injections with botulinum toxin, injections of various “fillers,” cutting the motor nerve to the corrugator, or placement of alloplastic implants. However, these methods compensate for an operation that failed to achieve its goal. The route to the corrugator muscles through a blepharoplasty incision not only is lengthy and somewhat tedious, but it also predisposes to deep scarring and lid deformity, such as cicatricial ptosis and/or lagophthalmos, in a significant number of patients. Precise transblepharoplasty corrugator removal is extremely difficult without causing injury to important nerves. Accurate identification of the supratrochlear nerve and its isolation from the corrugator muscle before muscle excision become quite difficult, as does the delicate removal of corrugator fibers as they weave their way anterior to the supraorbital nerve branches. Such a maneuver is easy through the open approaches.

Transblepharoplasty approaches to the orbital rim and frontal area for brow suspension offer some help but prove inadequate for the quality of repair needed. In our opinion, they are poor substitutes for open and complete removal of the corrugator muscle.

30 When is a direct excision of lower eyelid skin indicated?

Direct excision of lower eyelid skin is indicated for patients who have true excess rather than merely a dropped lid posture with pseudoexcess. Extreme care must be taken so that skin removal does not result in a pulling down or rounding of the lower eyelids. This problem always occurs unless an effective lid support procedure or canthopexy (canthal tightening) is also performed. Counsel all patients about the impossibility of completely removing the wrinkles of the lower eyelid, especially during smiling. Sometimes a type of resurfacing, with either laser modalities or chemical peel, may be a preferred treatment, but these too are lid skin shortening procedures, just as are skin excisions. These “resurfacing” procedures as well as most all skin excisions must be accompanied by some effective form of canthopexy if deformity is to be prevented. An advantage of resurfacing is the uniform skin shortening, which contrasts with the almost inevitable triangular-shaped surgical excision. Skin can be removed independently or as a portion of a skin-muscle flap, depending on the surgical procedure. Our preference is a short skin flap leaving a small amount of pretarsal orbicularis beneath the subciliary incision. Below that increase the flap thickness to include orbicularis. If there is no arcus marginalis and subperiosteal midcheek release, then proceed with a generous orbicularis muscle elevation in the lateral, malar, and subcanthal area. Then perform a two-layer canthal support and tightening of tendon, followed by orbicularis. Our preference is to leave the orbicularis and septum attached to each other, going deeper in the lid (deep to the orbital septum) and releasing the arcus marginalis at the orbital rim, continuing the dissection subperiosteally, and doing a generous malar release that divides the periosteum distally and facilitates a superb midcheek lift. A two-layer canthal tightening procedure (tendon and retinacular tissue as one layer and orbicularis as the other) follows. We usually attach the malar tuft to a small drill hole in the orbital rim with an absorbable 3–0 Vicryl suture. The orbicularis support is enhanced and broadened by several laterally placed Vicryl sutures attaching lateral orbicularis to deep temporal fascia. This has an amazing effect of eliminating the crease at the lid–cheek crease junction and diminishing the prominence of tear trough deformities. With limited undermining there usually is no need to remove more than several millimeters of lower eyelid skin.

31 What is the best method to rid a patient of the deep grooves commonly present near the junction of the eyelid and cheek skin?

Deep grooves near the junction of the eyelid and cheek are either tear trough deformities or nasojugal grooves. With tear trough deformity, the problem is primarily a bone defect. The nasojugal groove represents the muscular deficiency between the orbicularis oculi muscle and the angular head of the levator labii superioris (levator labii superioris alaeque nasi). Another contributing factor is the often tight adherence of muscle and orbital septum to the orbital rim and the arcus marginalis.

Different techniques have been used through the years. Loeb, Flowers, Hamra, and others have described techniques in which pedicles of orbital fat are mobilized into these areas. Free fat can be transplanted (or injected) as another method. The use of tissue fillers is yet another approach. The Flowers tear trough implant is the best option when a palpating finger clearly discerns and defines a suborbital malar bony defect. In such instances, an eyelet cut within the implant accommodates passage of the infraorbital nerve. The implant fits nicely into the defect, allowing a nasal attachment to the inferior orbital rim periosteum. Small holes throughout the implant allow tissue ingrowth and fixation. Implants can be inserted through subciliary, transconjunctival, intraoral, or direct incisions. The transconjunctival incision is best reserved for patients without prominent supraorbital ridges. Free grafts commonly leave irregularities, and fat injections leave palpable and often unacceptable visible protuberances. The same is the case for a host of other tissue fillers, most of which are temporary. Among this myriad of possibilities, our preference is injectable calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse), built up in rows of filler “cylinders” around the infraorbital nerve.

32 How do you permanently secure the brow into its desired (elevated) position?

Many techniques have been used. Surgeons involved in endoscopic brow lifting sometimes use screws, plates, or permanent sutures to anchor the brow until adequate healing and fibrosis are able to secure the brow in its new position. Similar techniques can be used with open large flap procedures, but fixation hardware is less frequently required. With the open procedures, markedly improved fixation is produced by removing the superficial temporal fascia (subgaleal tissue) in the parietotemporal area. This method allows better adhesion of the forehead flap to the skull. Remember that it is easy to overcorrect the medial brow and difficult to adequately correct the lateral brow. For these reasons, periosteal flaps occasionally are used with developmentally low, and especially asymmetrically low, eyebrows. In patients with asymmetry, the flap usually is restricted to the lower side (which usually is the right). This secures the brow into the desired elevated position. The superiorly based periosteal flaps are inserted into a beveled incision, made within the eyebrow hairs at the junction of the medial and lateral thirds of the eyebrows. The 2-mm-wide flap is taken just at the border of the temporalis fascia. This technique limits the caudal descent of the lateral brow, but the brow still can be raised by frontalis animation. This technique is far better than methods that fix the brow in place without allowing movement.

33 What is Whitnall’s ligament?

It is a condensation of the sheath overlying the anterior superior part of the levator muscle. Medially, it arises from connective tissue of the frontal bone posterior to the trochlea. Laterally, it attaches to the capsule of the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland and to the frontal bone portion of the lateral orbital wall approximately 10 mm above the lateral orbital tubercle. This structure is the point at which the direction of pull of the levator muscle changes from a horizontal to a vertical direction. It serves to limit the elevation of the eyelid with check ligaments. During blepharoptosis procedures, do not suture Whitnall’s ligament to the tarsus or other eyelid structures because this may result in a permanent lagophthalmos or inability to close the eyes. The superior transverse ligament was first described by Whitnall in 1910.

34 What is Lockwood’s ligament?

It is a hammock-like system with contributions from the inner muscular septae, retinaculum, Tenon’s capsule, and lower eyelid retractors. Posteriorly, Lockwood’s ligament arises from fibrous attachments from the inferior side of the inferior rectus muscle and continues anteriorly as the capsular palpebral fascia and lower eyelid retractors. This suspensory system has medial and lateral horns that extend into the retinacula. The medial retinaculum, in turn, attaches to the posterior lacrimal crest, and the lateral retinaculum attaches to the lateral orbital tubercle of Whitnall. The suspensory system of the globe was initially described by Lockwood in 1886. This suspensory system is tightened, the sagging globe is lifted, and the upper orbital hollowness is reduced by two-layer canthopexies secured into bone.

35 In patients with eyeliner and eyebrow tattoos, where should the blepharoplasty incisions be placed?

If a person wants the eyeliner tattoos on the lower lid removed or reduced, a subciliary incision superior to, or within, the tattoos allows their eradication, or reduction, provided the tattoos are not within the eyelash “line,” sufficient lower lid skin is present, and the lid is properly supported with canthopexies. Do not forget these supporting maneuvers. Tattoos on the gray line or surrounding the lashes cannot be removed without sacrificing eyelashes. If a person wants to preserve the tattoos, make the lid incision at the caudal margin of the tattooed eyeliner or just within it (to “spiff up” the “bleed” of pigment into surrounding areas.) The scar helps prevent the eventual, or continued, “bleed” into adjacent tissues.

Often, eyebrows have been tattooed to make up for deficient, nonexistent, or excessively caudal positioning. Rarely is it desirable to excise skin cephalad to these tattoos, nor is it feasible to perform other types of frontal lifts because they all will further elevate the tattooed brow. When there is excessive skin on the upper lid of the sort that normally would be corrected by a brow positioning procedure, the optimal solution often is a direct excision of brow tissue bordering the tattooed eyebrow. In this way the illusion of the brow remains in the optimal position, and special irreplaceable, thin eyelid skin that functions far better on the eyelid than thick, unwieldy brow or juxtabrow skin remains.

36 Which cranial nerve innervates the lacrimal pump that drains the tears?

The seventh cranial nerve innervates the orbicularis oculi muscle. The deep heads of the medial pretarsal and preseptal orbicularis contract and exert traction on the fascia immediately lateral to the lacrimal sac, known as the lacrimal diaphragm. This traction during contraction of the orbicularis creates a relatively negative pressure within the lacrimal sac that draws tears through the puncta and canaliculi into the lacrimal sac. Relaxation of the orbicularis oculi allows the lacrimal sac to collapse, and the tears traverse the nasolacrimal duct to the nose.

37 What is the difference in the terms “canthopexy” and “canthoplasty” as applied to tightening procedures on the lower eyelids?

For most patients the goal is not to alter so much as to recapture the shape and contour of the eyes they had in their youth. For others with natural or developmental transverse or reversed (antimongoloid) intercanthal axis tilts, the goal is indeed to raise the canthal insertion. One operation achieves the desired end result for both conditions, whether degenerative or congenital. The same operation also offers superb correction of iatrogenic and posttraumatic deformities. One name can efficiently describe that flexible procedure and eliminate the confusion between –pexy and –plasty, which hinges on a positional change of 1 to several millimeters in drill hole and/or suture position. Whether in actuality or illusion, because the eye appears lifted (with restoration of youthfulness and pleasing aesthetics), the choice and most logical descriptive term seems to be canthopexy!

38 During blepharoplasty, where is the “white” fat?

The medial or nasal upper eyelid fat usually has a color that is paler (white or yellow-white) than other fat of the eyelids and orbit. The lateral fat of the upper eyelid has a deeper yellow color. The medial fat pad of the upper lid may move anteriorly more prominently than do the other fat pads, resulting in a large bulge of the upper medial eyelid just inferior to the trochlea of the upper medial orbit. Often there is a hollowed-out defect in the area between the white medial fat compartment and the lateral “yellow” fat compartment, where the nasal portion of the septoaponeurotic sling housing the fat migrates superiorly. The medial lower eyelid fat is likewise pale in color.

Flowers R. Asian blepharoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:558-568.

Flowers R.S. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:351-365.

Flowers R. Correcting suborbital malar hypoplasia and related boney deficiencies. Aesthet Surg J. 2006:341-355.

Flowers R.S. Cosmetic blepharoplastyState of the art. Adv Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:31-67.

Flowers R.S. Optimal procedure in secondary blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:225-237.

Flowers R.S. Periorbital aesthetic surgery for men. Clin Plast Surg. 1991;18:689-729.

Flowers R.S. Tear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:403-415.

Flowers R.S. The biomechanics of brow and frontalis function and its effect on blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:225-268.

Flowers R.S. Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination: Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:193-207.

Flowers R., DuVal C. Blepharoplasty and aesthetic periorbital surgery. In: Aston S., Beasley R., Thorne C., editors. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:627-650.

Flowers R., Nassif J. Aesthetic periorbital surgery. In: Mathes S., editor. Plastic Surgery. 2nd. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2006:II:77-126.

Smith E.M., Dryden R.M. Eyelids: Anatomy, ectropion, entropion, blepharoptosis, blepharoplasty and abnormalities. In: Chern K.C., Wright K.W., editors. Review of Ophthalmology: A Question and Answer Book. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997:199-204.