Chapter 118 Congenital Anomalies

1 At what age of development does the limb bud appear? When are digital rays evident?

Streeter divided human embryonic development into 23 stages. Limb development and differentiation are rapid processes that occur between the third and eighth postovulatory weeks. The limb bud, called Wolff’s crest, is well defined at day 30. It is a ventral swelling mesoderm covered by a thick layer of ectoderm, called the apical ectodermal ridge (AER). By day 41 digital rays are present, and by day 48 joint interzones are evident histologically. Usually by the time the expectant mother is sure that she is pregnant, most of the upper limb differentiation has been completed.

2 What does syndactyly mean? Is it the most common congenital anomaly?

Syndactyly (Greek: syn = together, dactyly = finger) is commonly used to describe webbed digits and is the second most common congenital anomaly. The most common are duplications, particularly preaxial or thumb duplications in the Asian population and postaxial or ulnar duplications in African-American and Native-American populations. The incidence of duplications varies according to the population but overall occurs in 3.8:1000 to 12:1000 live births.

3 What type of correction is best for syndactyly?

No one repair is absolutely best. More than 60 methods have been described in the literature, and most use the same basic surgical principles. The surgeon must be comfortable with a few repairs that she/he learns to do well and not experiment with each case.

4 What are the principles of syndactyly correction?

When operating on young children, it is important to work under general anesthesia and to use a pneumatic tourniquet and absorbable 6-0 or 5-0 chromic suture material.

5 What are the most common problems after syndactyly correction?

Infection, graft or flap maceration, and graft loss are almost always related to the child’s activity and/or inadequate immobilization. Surgeons with children of their own do not hesitate to protect operated limbs in a long arm cast extending well proximal to the elbow flexed at 90°. Single residents without children do not always appreciate the problems that most parents encounter with controlling active young children. Early problems also may occur after children wet their casts or dressings in bathtubs or swimming pools.

Long-term problems include recurrence of the webbing or “web creep,” which is related to scar contracture at the base of the commissure or along the incision lines. Zigzag incisions are intended to reduce this potential contracture. Skin grafts often are hyperpigmented and, if harvested within the hair-bearing escutcheon, may become hirsute during adolescence. Inadequate correction of the first web release may be obtained with tight contractures, which can be widened only with additional soft tissue.

6 What is the most important web space in the hand?

The thumb–index or first web space is unquestionably the most important. Of all techniques described for correction of congenital hand anomalies, release of the first web space is the most significant functionally and aesthetically. In a pure analysis, a “basic hand” has three components: a mobile digit or thumb on the radial side, a first web space, and a post or digit on the opposite side of the hand.

7 What is the best method for surgical release of the first web space?

The surgeon must learn to use one or two methods well. For minimal to moderate contractures, the four-flap Z-plasty provides the greatest release and maintains the best concavity between the thumb and index metaphalangeal (MP) joints. A single Z-plasty and the five-flap Z-plasty, also called the “jumping man,” are good alternatives. Many varieties of dorsal rotational flaps from the thumb or index metacarpal regions have been described with the use of skin grafts. These techniques are not preferred because they leave a conspicuous skin graft in a visible position of the hand. These local flaps are indicated in complex problems such as the Apert hand.

For severe contractures, soft tissue is often needed. Free tissue transfers in infants or young children often are cumbersome and technically difficult. Distally based forearm (radial artery or dorsal interosseous artery) fasciocutaneous flaps have been described for children with arthrogryposis, windblown hands, and hypoplastic thumbs with tight contractures and are advised for use by experienced surgeons.

8 What contributes to thumb–index contracture?

Tight skin is the most obvious etiology, but tight investing fascias of the first dorsal interosseous and adductor pollicis muscles almost always are found and must be excised. Often a tight band is present between the two muscles. Occasionally, a tight thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint may be found; it usually is suspected on physical examination.

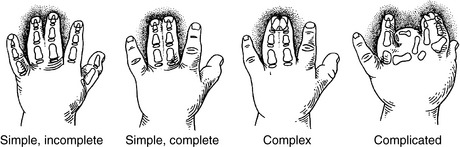

9 How is syndactyly clinically classified?

The level of webbing between digits is complete if it extends to the fingertip and incomplete with a more proximal termination. A simple syndactyly refers to soft tissue connections between adjacent digits, whereas complex refers to bone or cartilaginous unions. Complicated refers to abnormal duplicated skeletal parts within the interdigital space (Fig. 118-1). The most common pattern is bilateral simple, incomplete syndactyly of the long and ring fingers. Many such patients have a simple syndactyly involving toes 2 and 3 on one or both feet.

10 Do children need more surgery after syndactyly repair?

There is always a chance that contractures will require future correction. The literature cites a secondary operation rate of approximately 10%. The incidence is much higher in complex and complicated cases and in cases with postoperative complications. There is a direct relationship between carefully planned and executed surgery and a low complication rate. Children and adults with central complex polysyndactyly invariably need secondary corrections. This variety is the most difficult to treat.

11 Geneticists and pediatricians use the terms malformation, deformation, and disruption. What do they mean?

The dysmorphology approach to congenital anomalies divides defects into one of three sequences, which are defined as problems that lead to a cascade of events:

12 What is the relative incidence of congenital hand duplications? How are they clinically classified?

Duplications are the most common anomalies in all large series. They are classified by their position within the hand as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar). In the United States, duplication is most prevalent among African Americans, who have an extremely dominant inheritance pattern with a frequency of 1:300 live births and a predilection for the postaxial border of the hand. In contrast, Caucasians and Asians primarily have preaxial duplication at a rate of 1:3000 live births (see Question 2).

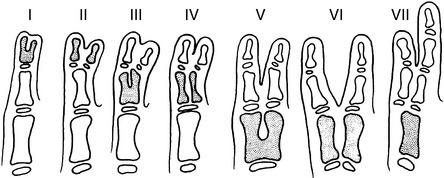

Preaxial thumb duplications are classified into six categories by the level of the duplications. Type II at the interphalangeal (IP) joint and type IV at the MP joint are the most common. The more proximal varieties, type V at the thumb metacarpal level and type VI at the CMC joint level, are uncommon. Additional designations are made if there is an extra phalanx (delta phalanx) or a triphalangeal partner (type VII). Triphalangeal thumbs are unusual and well beyond the experience of most residents (Fig. 118-2).

Figure 118-2 Classification of thumb duplications based on the level of duplication. Type VII describes the triphalangeal thumb.

(From Upton J: Congenital anomalies. In Jurkiewicz M, Krizek TJ, Mathes SJ, Ariyan S [eds]: Plastic Surgery: Principles and Practice. St. Louis, Mosby, 1990, p 573.)

Central duplications are unusual and account for less than 10% of all duplications; they have no systematic clinical classification system. Because central duplications are often associated with webbing, the term synpolydactyly is used.

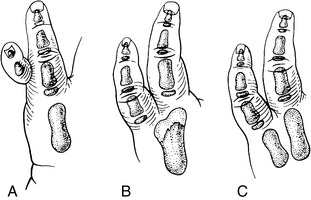

Postaxial duplications of the fifth ray are divided into three categories. Type I is characterized by a soft tissue nubbin with a skin bridge. Skeletal connections are present in type II, and a complete duplication of the entire ray is seen in type III (Fig. 118-3). Most cases are type I.

Figure 118-3 Classification of polydactyly (postaxial) demonstrates digits with no skeletal attachment—type I (A), skeletal connections—type II (B), and complete duplication of the entire ray, including the metacarpal bone—type III (C).

(From Upton J: Congenital anomalies of the hand and forearm. In McCarthy JG, May J, Littler JW [eds]: Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1990, p 5345.)

13 Is any special workup needed in newborns with a duplication?

In most cases, no. Thumb duplications may have a positive inheritance pattern and are common in Caucasian and Asian populations, whereas fifth finger duplications are extremely common in African-American and Native-American populations. When the opposite is seen, a workup is in order. More than 30 syndromes are associated with postaxial duplications, primarily in non–African-American populations. Conversely, an African American with thumb duplication and negative family history may have a syndrome such as fetal alcohol syndrome. Referral to a geneticist is in order.

14 How do you treat a newborn in the nursery with a type I floppy nubbin attached to the fifth finger?

Pediatricians like to “tie them off” with a suture. Type I duplications with large skin bridges often do not fall off. Many such children present to the dermatologist 8 years later with a bump at the site of duplication, which is misdiagnosed as a wart. The “wart” does not respond to application of a triple acid ointment or solution. This lump is a cartilaginous remnant or scar. Simple excision and closure with one or two sutures under local anesthesia in the newborn nursery is a more appropriate option.

15 Which side of a thumb duplication should be preserved?

The correct answer depends on which thumb has the better parts. In most patients the radial of the two partners is the more hypoplastic and is ablated. In some more proximal type V and type VI varieties at the metacarpal level, the distal portion of the ulnar partner is transposed on top of the proximal portion of the radial partner.

17 What do you tell parents after a thumb duplication correction? Will the thumb be normal?

No. Most large series are incomplete and do not include critical long-term outcomes. What you see initially is what you get later. The reconstructed thumbs usually are smaller and less mobile than the normal side. Thenar muscles, especially the abductor pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis brevis, may be weak. Metacarpophalangeal joint instability or stiffness may occur after a collateral ligament reconstruction. A bulge on the radial side of the metacarpal in a type IV thumb represents a bifid metacarpal head that was not excised. The proximal type V and VI thumbs are never normal postoperatively, do not have normal intrinsic muscles, have short metacarpals, and commonly have inadequate extrinsic extensor and flexor tendon excursion.

18 What are the genetics and incidence of the constriction ring syndrome?

There is no positive inheritance in constriction ring syndrome (CRS). The incidence is less than 10% in large reported series of congenital hand malformations. The cause is related to an in utero deformation in which strands of the inner layer of the chorionic sac detach and wrap around parts of the fetus, usually fingers and toes. There are many examples of monozygotic twins with only one partner affected.

19 What anatomic features distinguish CRS from other congenital anomalies of the upper limb?

The anatomy proximal to the level of deformation or in utero injury is completely normal. For this reason, toe transfers for thumb and digital reconstruction are much more predictable. Unfortunately, many severely affected children have no toes to transfer.

20 What other terms have been used to describe CRS?

Many terms have been used to describe the clinical features seen in CRS.

This condition has been around for a long time and has been confused in past and recent literature. The term constriction ring syndrome has been adopted by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) and the International Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand (IFSSH).

21 What is a constriction ring or anular (ring) band?

The constricting ring acts as a tourniquet around the developing digit, toe, or other body part and results in a soft tissue depression beneath the skin. The ring may be superficial or deep, extending into the periosteum. It may extend completely or partially around the circumference of the part. Most digital rings are deep dorsally and extend only partially around the palmar surface. However, this explanation does not account for the frequent association of cleft lip/palate and club feet with CRS. The clefts often are wide lateral clefts that result in a monstrous clinical appearance. It has been postulated that wide bands or aprons of partially separated sac obstruct the fusion of the lateral lip with the prolabial segment.

22 How is CRS treated?

In the past, surgeons performed simple Z-plasties that did nothing more than leave the mark of the infamous cowboy Zorro on operated hands. After excision of the scarred constriction ring, it is necessary to advance flaps of fat and fascial tissue across the depression to correct the contour deformity. Straight-line dorsal incisions are preferred to Z-plasties; they are conveniently placed along the less visible sides of the digit.

23 Why are transverse absences associated with CRS ideal for toe-to-thumb transfers?

CRS is the only congenital anomaly in which the anatomy proximal to the level of complete or partial loss is completely normal. In other conditions, intrinsic and extrinsic muscle and neural and vascular anatomy may be anomalous.

24 What does symphalangism mean? What are the more common clinical presentations?

Symphalangism (Greek: sym = together, phalanx = bone) refers to phalanges that are fused because of a failure of segmentation or incomplete segmentation with cavitation. More than 15 clinical conditions are associated with these stiff, often short and slender digits. The most important clinical sign is the lack of a flexion crease. There are three general categories of symphalangism:

25 How is symphalangism treated?

The stiff fingers will always be stiff. Angulation and especially rotation should be corrected early in life without damage to growth centers.

26 In what position should PIP joints be fused?

Index finger, 10°; middle finger, 25° to 30°; ring finger, 40°; and small finger, 45° to 50°.

27 How can IP joints be reconstructed?

Many methods have been tried, but none is satisfactory. Examples include the following:

All of these reconstructions have advantages and disadvantages. In children, use of autogenous materials is preferable to avoid the secondary disadvantages of incompatible biomaterials. Perichondrial resurfacing at the MP and PIP levels results in fibrocartilage and stiff joints. Early release and continued motion result in floppy digits that ultimately become stiff. Osteointegrated concepts have not yet been used in children but may have promise. Microvascular defects are labor intensive and biologically make the most sense. The balance of the thin intrinsic and extrinsic extensor mechanism is never maintained.

28 What is the difference between clinodactyly and camptodactyly?

Clinodactyly (Greek: clino = deviated, dactylos = digit) refers to a digit or thumb that is deviated in a radioulnar or mediolateral direction. An inward (radial) deviation of the fifth digit is most commonly seen and is so often associated with various other types of congenital hand anomalies that it represents “background noise” and gives no specific indication of one condition over another.

Camptodactyly (Greek: campto = bent, dactylos = digit) refers to a flexion deformity of a digit or thumb in an anteroposterior plane. This deformity also commonly involves the PIP joint of the fifth finger and is seen in two distinct age groups: infants and adolescent girls.

29 What is the main anatomic problem in camptodactyly?

As the digit develops in the fetus or infant or as it continues to grow in the young child and adolescent, the balance of flexion and extension forces at each joint is quite precise. More than 20 abnormal origins and particularly insertions of the intrinsic and extrinsic muscle tendon units within the hand have been described. The most common variations involve abnormal distal insertions of the lumbrical and interosseous muscles within the digits, particularly on the ulnar side of the hand. Tight joint capsules, collateral ligaments, joint contractures, abnormal articulating surfaces, and proliferative fibrous bands (fibrous substrata) within the digit are more likely secondary and are not the primary forces causing camptodactyly.

30 What are the radiologic signs of congenital camptodactyly?

A true lateral radiograph of the digit gives an indication about the duration of congenital camptodactyly. Digits that have been flexed at the PIP joints for longer periods show the following:

The most important determining factor in joint formation is motion. A joint that is not moved early in life will not have a rounded condyle and will demonstrate a flat articular surface.

31 What are the indications for joint release in camptodactyly?

Most joint contractures are treated successfully with stretching and splinting. Few require surgical release. Contractures of 15° to 50° usually have favorable outcomes. Adults and adolescents with longstanding contractures greater than 70° of flexion are best treated with arthrodesis. The results of soft tissue releases are inversely proportional to the severity of the contracture. Often initial tight contractures can be improved with conscientious stretching but may need surgery later in childhood to obtain full correction. Surgery may be difficult and must be followed by a strict stretching and night-splinting regimen.

32 What is the differential diagnosis of bilateral flexion deformities of the thumb?

Trigger thumbs due to flexor tenosynovitis are the most common cause. Newborns and infants may demonstrate congenital absence of the extrinsic extensor (extensor pollicis longus), a condition in which the thumb is adducted into the palm (commonly called “clasped thumb”). Congenital camptodactyly does not involve the thumb but should be considered with any flexion deformity of a digit. More generalized musculoskeletal conditions, such as arthrogryposis and Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, also must be considered.

33 When should a trigger thumb be released surgically?

In children younger than 18 months, spontaneous resolution may be seen within 6 months. After age 2 years, children with persistent locking develop compensatory hyperextension of the MP joint as the palmar plate is stretched. This hyperextension may not correct itself with growth after the trigger is corrected. No additional surgery is indicated unless functional problems are present. Forget about approaching a young child with a needle for a steroid injection in your office. This method will not work. Percutaneous needle releases have been described in older patients but have little place in the treatment of young children in whom surgical division of the A1 pulley is indicated.

34 What is the worst complication of a trigger release?

The radial digital nerve to the thumb is easily severed with blind cutting in a proximal direction.

35 What conditions should be considered in a child born with gross enlargement of a digit?

Macrodactyly (Greek: makros = large, dactylos = digit) and gigantism have been used to describe enlarged digits and thumbs. Gigantism is preferred by some because it encompasses enlargement of both soft tissues and skeletal elements. The clinician should consider the following:

These unusual conditions should be referred to a pediatric hand specialist.

36 What is the workup for macrodactyly?

These conditions are rare. Common sense dictates that the clinician obtain radiographs, complete a thorough physical examination, and then hit the books. NF is suspected on clinical examination and has specific criteria. Biopsies are rarely necessary. Genetic analysis is available. Vascular anomalies are distinguished by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Bone tumors often require biopsy. Hemihypertrophy is the most difficult and often is a diagnosis by exclusion. In this condition there is a high incidence of adrenal masses, which must be detected by ultrasound. No one other than the pediatric hand specialist has a detailed working knowledge of all of these conditions. It is helpful to contact someone locally or nationally with experience in treatment of each particular condition.

37 What is the difference between hemangioma and vascular malformation?

During the past 10 years knowledge has increased exponentially. Mulliken made the most significant contribution with his classification, which makes a clear-cut distinction between the two on biologic grounds. Hemangiomas are vascular birthmarks that appear shortly after birth, undergo a period of rapid growth and proliferation, and spontaneously involute by age 7 to 9 years. The endothelial cells actively proliferate and create new vascular channels during the growth phase. The mechanism for involution is unknown. Vascular malformations are biologically quiescent lesions. They result from defective embryogenesis, are present at birth or are recognized shortly after birth, and do not undergo a biphasic growth cycle like hemangiomas. The endothelial cells do not actively proliferate. Malformations are subgrouped according to cell types into capillary, venous, lymphatic, mixed venous–lymphatic, and arterial malformations. Arterial malformations include arteriovenous fistulas with active shunting between the arterial and venous sides of the circulation.

38 Outline the five types of hypoplastic thumbs

39 What are the possible options for reconstruction of type 3B thumbs?

The options are (1) staged osteoplastic reconstruction and (2) excision of the thumb and index pollicization. The second option is preferred by most pediatric hand specialists. Staged reconstruction involves (1) provision of skeletal continuity with a standard bone graft or a microvascular second toe transfer, (2) creation of an adequate web space, and (3) tendon transfers to provide palmar abduction of the first ray as well as MP and IP flexion and extension.

40 What are the long-term functional limitations of a well-performed pollicization procedure?

Such thumbs are never normal. Grip and pinch maneuvers involving the thumb are always deficient. Results fall into two basic groups: (1) complete or partial radius deficiency and (2) normal radius and preoperative range of motion. The second group has predictably better outcomes because extrinsic flexor and extensor muscles as well as intrinsic muscles to the index ray are normal. A stiff index finger preoperatively will become a very stiff thumb.

41 Describe the hand in patients with Apert syndrome

Apert syndrome (acrocephalosyndactyly) is common only in craniofacial clinics. It occurs in more than 1:45,000 live births. Both hands have enantiomorphic (mirror image) deformities:

Three specific types of hand configurations with varying degrees of severity have been described. Additional skeletal anomalies include carpal coalitions, a ring–fifth metacarpal synostosis, symphalangism between the proximal and middle phalanges, and varying degrees of conjoined nails. The hands are subclassified into three separate groups depending on the severity of skeletal coalition.

42 What is Poland syndrome?

In 1849 Alfred Poland, a student dissector in gross anatomy, described a cadaver with chest wall anomalies associated with a hypoplastic webbed hand. The illustration made by a friend did not include the hand, but the head, neck, and thorax were depicted in detail. A century after this description appeared in the Guy’s Hospital Reports, Clarkson, the hospital hand surgeon, found the hand that had been preserved in the hospital museum, redescribed the condition, and introduced the term Poland syndrome. The hand surgeon’s definition includes (1) absence of the sternal head of the pectoralis major muscle (clavicular head usually is present), (2) hypoplastic hand, and (3) brachysyndactyly (short, webbed fingers). We have further described the hand anomalies as affecting primarily the central three rays of the hand. The four variations of severity range from least affected (hypoplastic but present index, long, and ring digits) to a hand with no digits or thumb.

43 How is the chest wall reconstructed in children with Poland syndrome?

Nothing is usually done in children. In adolescents, conspicuous deformities can be reconstructed with correction of the pectus carinatum (pigeon breast) or pectus excavatum (caved-in chest) deformities, followed by a latissimus dorsi muscle transfer to recreate the missing pectoralis major muscle.

44 What is the most persistent request of girls with Poland syndrome?

Girls request breast reconstruction, which is different from a simple augmentation or reconstruction after mastectomy. Expansion and overexpansion must be completed before final implant placement because the integument, including the areola, often is highly deficient. Subpectoral implants are preferred, but this muscle is either deficient or absent. Latissimus transfer with submuscular implants is then performed. It is wise to wait until adulthood before doing a transverse rectus abdominis muscle or free tissue transfer reconstruction.

45 A child is born with impending gangrene of portions of one or both forearms. What condition does the child have? What type of workup is indicated?

This rare and often catastrophic condition, called cutis aplasia congenita, probably results from mechanical impingement or pressure on the upper limbs. Usually the forearms are caught between the head or trunk and the pelvic brim. The condition is often associated with multiple births. Mothers often give a history of lack of movement for one or more days before delivery. Routine workup, including blood tests and radiographs, is normal. This condition can be viewed as an in utero Volkmann’s contracture.

46 What is Holt-Oram syndrome?

In the late 1950s two pediatricians, working independently in the United States and England, described the association between congenital hand anomalies and congenital heart defects. The cardiac anomalies vary greatly, but the hand malformations consist primarily of some form of radial dysplasia. If a surgeon has the opportunity to examine a large number of infants with congenital heart defects, he/she will find many cases of minimal radial dysplasias, such as hypoplastic thenar intrinsic muscles. Children with radial club hand or thumb hypoplasia or absence are not difficult to diagnose.

47 What single operation is most beneficial for patients with a congenital hand anomaly?

Release of the first (thumb–index) web space. For mild to moderate deficiencies we prefer the four-flap Z-plasty and for tight, constricted web spaces the distally based radial forearm flap or dorsal interosseous flap. Dorsal sliding flaps are not preferred because of the unsightly, hyperpigmented skin grafts in the donor region. However, they are popular in both orthopedic and plastic surgical literature because of the mobility of the dorsal skin and the technical ease of the procedure.

48 Describe the hand in a child with Freeman-Sheldon syndrome

The “whistling face” syndrome presents with characteristic hand and facial anomalies. The hands are often narrow with prominent ulnar drift. Incomplete, simple syndactyly and varying degrees of PIP camptodactyly are often present. The first web space usually is tight. The descriptive term “windblown hand” is often applied. Many other musculoskeletal anomalies, such as scoliosis, hip dysplasia, and radial head dislocation, may be present. These children are not retarded mentally.

49 A child presents with a swollen hand and forearm and an associated neck mass diagnosed as a “cystic hygroma.” What is the underlying pathophysiology?

Cystic hygroma describes a lymphatic malformation in the head and neck region. The upper limb as well as mediastinum also may be involved. In the hand and forearm the interconnecting lymphatic channels may be much smaller. The size of the limb may be quite large, grotesque on occasion. Besides the symptoms related to bulk and increased weight, many children develop high fevers related to episodic beta-streptococcal infections, which usually originate in the cutaneous vesicles often found in lymphatic lesions. Skeletal enlargement may be present but is not a hallmark of these macrodactylies, which are difficult to treat. Staged aggressive debulking is the treatment of choice once conservative measures and compression garments have failed.

50 What is the difference between a typical and atypical cleft hand?

They are completely different. A typical cleft hand has the following characteristics: bilaterality, positive inheritance, foot involvement, V-shaped cleft, and syndactyly (common). A portion or all of the middle ray is commonly missing. It is often called simply a cleft hand. The atypical cleft refers to a unilateral anomaly that is nonfamilial and has a U-shaped cleft with no foot involvement. Small nubbins often represent rudimentary digits. This condition often has been called “lobster claw hand.” After much discussion at various international meetings, the committees for the study of congenital anomalies of the hand recommend that “atypical cleft hand” be officially classified as symbrachydactyly.

51 Describe the upper limb in a child with severe arthrogryposis multiplex congenita

Arthrogryposis, a syndrome of unknown etiology, is always present at birth and manifests with persistent joint contractures. It is classified into myopathic and neurogenic forms. The bottom line is that the muscles do not function. The upper limb appearance is unmistakable. The shoulders are thin and held in adduction and internal rotation. The elbows are extended, and the forearms are usually held in a semiflexed pronated position. Some elbow passive range of motion may be present. In severe cases the wrist is held in flexion and ulnar deviation, and the thumb is tightly adducted into the palm. The digits are flexed and ulnarly deviated at the MP joints. The skin may be atrophied and waxy. Skin dimples dorsally and flexion creases on the palmar surfaces signify mobile joint spaces. The lower extremities are more frequently involved than the upper.

Dobyns J.H., Wood V.E., Bayne L.G., Congenital, 3rd ed, Green D.P., editor, Operative Hand Surgery, Vol 1, 1993, Churchill Livingstone, New York, 251-549.

Flatt A.E. The Care of Congenital Hand Anomalies. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 1994.

Lister G. Congenital. In: Lister G., editor. The Hand. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:459-512.

Mulliken J.B., Young A.E. Vascular Birthmarks. In Hemangiomas and Malformations. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988.

Upton J., Congenital anomalies of the hand and forearm, McCarthy J.G., May J., Littler J.W., editors, Plastic Surgery, Vol 8, 1990, WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 5213-5398.