Chapter 131 Thumb Reconstruction

1 When was the first toe-to-thumb transfer performed for thumb reconstruction?

Chung-Wei and associates reported the first successful replantation involving a severed hand in 1963. The first thumb replantation was reported by Komatsu and Tamai of Japan in 1965. The first successful toe-to-thumb transfer in a monkey was performed by Buncke in 1965, and the first toe-to-thumb transfer in a human was reported by Cobbett in 1968.

3 What is adequate thumb length for useful function?

The thumb is important for opposing fingers when grasping and pinching. When placed beside the index finger, the thumb should reach beyond the proximal third of the index proximal phalanx. Significant functional deficits occur when the thumb is shortened beyond the neck of its proximal phalanx.

4 What methods are available for thumb reconstruction?

The available surgical methods are osteoplastic reconstruction, finger pollicization (usually of the index finger), and microsurgical toe transfer. Prosthetic replacement is also a consideration.

5 In the era of microsurgery, why even consider prosthetics?

The patient may not be a surgical candidate. A prosthesis may lengthen and make useful a shortened digital stump. It also may give a more esthetic appearance to the hand. Even after successful reconstruction, patients may request an aesthetic prosthesis.

6 Is the child with a congenitally missing part an “amputee”?

No. It is a mistake to think of a child with congenital hand differences as an amputee. Children with congenital hand anomalies view themselves as normal, and the vast majority function well by using their own techniques. They are disabled only in comparison with others. To imagine what it would be like to have their deformity, we imagine an amputation.

7 Should you fit a prosthesis on a child?

If the child has a functional pinch, no. The prosthesis will be more of an encumbrance. Children with congenitally absent thumbs usually develop a pinch between the index and long finger.

8 How and why does the reconstructive approach differ in congenital and acquired thumb deficiencies?

Congenital thumb deficiencies result from a failure of formation of anatomic structures. As a result, the available recipient nerves, blood vessels, tendons, and muscles for tissue transfer are unpredictable and often unavailable. Therefore microsurgical toe transfer is not considered the most appropriate treatment.

Congenital thumb deficiencies requiring major reconstructive efforts involve the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint, whereas acquired deficiencies range from defects involving the distal phalanx to the base of the metacarpal.

Reconstruction of the congenitally deficient thumb requires consideration of the critical motor development that occurs within the first few years of life as well as future growth.

9 What syndromes are associated with thumb hypoplasia, and what associated systemic disorders must be considered?

Holt-Oram syndrome is associated with cardiovascular malformations. Thrombocytopenia–absent radius (TAR) syndrome is associated with thrombocytopenia. Fanconi’s anemia is associated with pancytopenia (surgery is contraindicated). VATER involves vertebral defects, imperforate anus, tracheoesophageal fistula, and radial and renal dysplasia.

10 What is the timing of reconstruction of the congenitally deficient thumb?

The main reason for early surgical reconstruction is to provide children with a functional hand and allow for cortical development during critical times. Grip and grasp functions develop between 4 and 7 months of age, thumb and index finger function develops at 1 year, and specific functional patterns develop at 2 to 3 years of age. Therefore surgeons have undertaken reconstruction as early as within 1 year of age. However, earlier surgery is made technically more difficult due to the small sizes of involved structures.

11 How are congenital thumb deficiencies classified?

Blauth described five types of hypoplasia of the thumb (Table 131-1).

Table 131-1 Classification of Hypoplasia of the Thumb

| Type I | Minimal shortening or narrowing |

| Type II | |

| Type IIIA | |

| Type IIIB | Same as type IIIA with unstable CMC joint |

| Type IV | |

| Type V | Complete absence of thumb |

CMC, Carpometacarpal.

12 What types of thumb deficiencies should be reconstructed?

Types II and IIIA are candidates for reconstruction. Types IIIB, IV, and V are best served by index finger pollicization.

13 Why not a toe-to-thumb transfer?

Usually absence of a thumb is part of a more significant longitudinal deficiency with lack of recipient structures. Even in cases of hypoplasia, if the child has a functioning pinch between the index and middle fingers, existing function should be enhanced by pollicization rather than by toe transplantation.

14 What techniques can be used for less severe hypoplasia of the thumb?

15 How is the index finger pollicized?

The digit is shortened by removing almost the entire metacarpal, save the metacarpal head, which assumes the function of the trapezium. The finger is dissected as an island flap on the flexor and extensor tendons, the two neurovascular pedicles, and dorsal veins and nerves. The finger is pronated 140° to 160° and fixated into the correct axis of the thumb. Hyperextension of the index MCP joint is prevented by fixing the metacarpal head in palmar rotation.

16 Why is the metacarpal head palmarly rotated?

The MCP joint of the index finger is a condylar joint that can be hyperextended some 45°, whereas the CMC joint of the thumb is a saddle joint that circumducts but resists hyperextension. To allow the transposed index finger to generate the forceful pinch needed, it is fixed with the joint extended to full passive range. The palmar capsule and volar plate then resist further hyperextension.

17 Which muscles of the index finger assume the function of which muscles of the thumb?

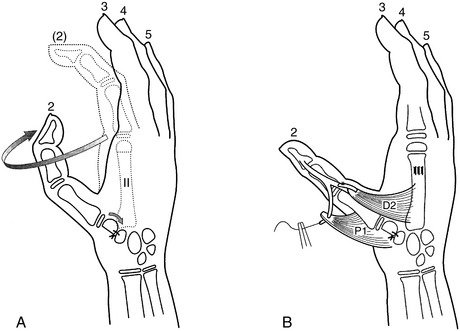

See Table 131-2 and Fig. 131-1.

Table 131-2 Index Finger Muscles that Assume the Function of Thumb Muscles

| Index Finger Muscle | Thumb Muscle |

|---|---|

| First dorsal interosseus | Abductor pollicis brevis |

| First palmar interosseus | Adductor pollicis |

| Extensor digitorum to the index | Abductor pollicis longus |

| Extensor indicis proprius | Extensor pollicis longus |

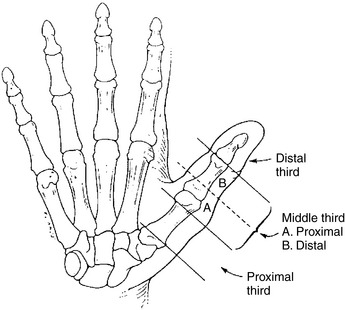

18 What are the options for reconstruction of the distal third of the thumb?

The distal third of the thumb involves everything distal to and including the interphalangeal (IP) joint. Local options for small defects include V-Y advancement flaps, a Moberg palmar advancement flap, and a cross-finger flap. Distant options for larger defects include groin, arm, and submammary flaps. Free tissue options include free toe pulp and composite tissue transfers (Fig. 131-2).

19 What are the options for reconstruction of the middle third of the thumb?

The middle third of the thumb involves the distal third of the metacarpal to the IP joint. Options for defects from midproximal phalanx and distal include first web space deepening (“phalangization”) with a four-flap Z-plasty or a dorsal rotation flap. Options for defects proximal to the midproximal phalanx include a “cocked hat” flap, osteoplastic reconstruction (distant flap coverage of a bone graft to extend the length of the thumb), composite osteofasciocutaneous radial forearm flap, pollicization of an injured digit, and distraction osteogenesis. Toe-to-thumb transfer is an option in both proximal and distal portions of the middle third of the thumb.

20 What are the options for reconstruction of the proximal third of the thumb?

The proximal third of the thumb involves amputations proximal to the distal third of the metacarpal. If adequate metacarpal base remains, a second toe transfer can be used to reconstruct the metacarpal and phalanges. If the metacarpal base is absent or inadequate, a pollicization with either an injured or uninjured digit can be used. In this case the index MCP joint is used to reconstruct the CMC joint.

21 What is osteoplastic reconstruction?

It is a multistage reconstructive technique that uses bone grafting or lengthening osteotomies, covered with skin flaps, on the remaining thumb stump to add length and to provide opposition. No joints are reconstructed. Sensation can be provided in the form of a neurovascular island flap, transferred from a finger (the usual donor is the ulnar side of the middle or ring). Most experts believe that microvascular toe transfer provides a better reconstruction with more similar tissue and joints for partial amputation of the thumb.

22 Does loss of the first toe cause gait disturbance?

Gait studies show shifting of weight distribution away from the first metatarsal head, but if the metatarsal head is preserved, the disturbance in gait is minimal.

23 What is the vascular pedicle of the transferred first toe?

The first dorsal intermetatarsal artery, which arises in most cases from the dorsalis pedis artery but occasionally from the deep planter system. The origin may be determined at the time of operation. If the deep system is dominant, a reversed vein graft extension may be needed. The more important question concerns the recipient blood vessels in the hand. In patients with any degree of injury to the hand, an arteriogram should be obtained to determine the residual vascular anatomy.

24 Can parts of toes be used?

Yes. Neurovascular island flaps can be used to provide innervated pulp to the oppositional surfaces. This technique is especially useful in the multiply traumatized hand, to which traditional neurovascular island flap techniques would add further debility. Transfer of vascularized joints from the foot to the thumb in severe isolated joint trauma has been reported.

25 Describe the different options for toe-to-thumb transfer

Great toe transfer can be used for amputations distal to the metacarpal and provides a strong reconstruction. It is based on the first dorsal metatarsal artery (from the dorsalis pedis) and the deep plantar artery. The great toe plays a major role in normal gait. Donor site morbidity and gait disturbance are major disadvantages. The cosmetic results can be inferior to other options due to the size and bulk of the great toe.

The trimmed toe flap involves trimming the great toe to the dimensions of a normal thumb improving cosmesis, but this makes the operation technically more difficult.

The wraparound flap involves transferring only the soft tissues of the great toe in combination with a bone graft. The great toe is preserved and the donor site is skin grafted to prevent gait disturbances. The advantages include better cosmesis and prevention of donor site morbidity; however, the operation is considerably more complex.

The second toe transfer uses a toe other than the great toe, thereby minimizing donor site morbidity and gait disturbance. The head of the metatarsal may also be harvested to provide an additional joint and length if necessary. The second toe transfer is also based on the first dorsal metatarsal artery. Disadvantages include a small appearance and a potential mallet deformity of the IP joint.

26 When is pollicization preferable to toe transfer for reconstruction of a traumatically amputated thumb? What are the advantages and disadvantages compared with a toe-to-thumb transfer?

When the metacarpal is completely absent a pollicization is required because there is no way to reconstruct an adequate basilar joint with a toe. Compared with a toe-to-thumb transfer, a pollicization provides better sensation and finer motor control. A toe-to-thumb transfer provides a better cosmetic result and greater strength.

CONTROVERSY

28 Which toe is preferred for thumb reconstruction?

Buck-Grancko D. Pollicization. In: Blair W.F., editor. Techniques in Hand Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

Buncke H.J. Great toe transplantation and digital reconstruction by second-toe transplantation. In: Buncke H.J., editor. Microsurgery: Transplantation-Replantation. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1991.

Pillet J., Mackin E.J. Aesthetic hand prosthesis: Its psychological and functional potential. In Hunter I.M., Schneider L.H., Mackin E.J., Callahan A.D., editors: Rehabilitation of the Hand, 3rd ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 1990.

Wei F.C., el-Gammal T.A. Toe-to-hand transfer. Current concepts, techniques and research. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:103-116.