Chapter 144 Anatomy of the Wrist

1 What is the normal blood supply pattern of the scaphoid? The capitate? The lunate? The hamate?

The scaphoid receives its blood supply through small branches, primarily from the radial artery, that enter the bone through two channels. The distal pole is supplied by the palmar scaphoid branch, which enters the scaphoid through the palmar cortex. The dorsal scaphoid branch enters the scaphoid along the dorsal ridge of the scaphoid near the waist region. No consistent nutrient vessels enter the scaphoid proximally, and internally the nutrient vessels do not anastomose. Because the proximal pole is supplied solely by vessels entering distally and coursing proximally, the proximal pole is at particularly high risk for avascular necrosis with fractures proximal to the waist of the scaphoid.

The capitate is supplied by multiple nutrient vessels entering the palmar and dorsal cortices of the body of the capitate. Because there are no soft tissue attachments proximal to the neck, the head of the capitate depends on retrograde flow from the more distal nutrient vessels and is vulnerable to avascular necrosis in the case of a fracture through the neck.

The lunate has consistent nutrient vessels entering through the palmar and dorsal cortices, although there may be some dominance of the palmar nutrient vessels. The intraosseous anastomosis patterns have been described as forming X, Y, and I patterns.

The hamate has three general areas of nutrient vessel penetration: dorsal cortex, palmar cortex, and hamulus. The dorsal and palmar vessels have been shown to anastomose in approximately 50% of specimens. The pole of the hamate is without direct soft tissue attachments and therefore relies on retrograde flow from the more distal palmar and dorsal nutrient vessels. Thus the pole is at risk for avascular necrosis (although it is rare) in the event of a fracture. The hamulus typically has a rich blood supply but rarely anastomoses with the vessels entering the body of the hamate. This pattern may contribute to the nonunion rate in fractures of the hamulus.

2 What is the normal percentage of force or load transmission through the ulnocarpal joint?

Under normal conditions, approximately 20% of the entire longitudinal force or load is transmitted through the ulnocarpal articulation; the remaining 80% is transmitted through the radiocarpal articulation. Factors that increase ulnocarpal load transmission include wrist ulnar deviation, positive ulnar variance, and pronation of the forearm.

3 Describe the ligaments that interconnect the bones of the proximal carpal row

The ligaments that connect the bones of the proximal carpal row are the scapholunate and lunotriquetral interosseous. They are similar to each other in that both are C-shaped, connecting the palmar, proximal, and dorsal regions but leaving the distal surfaces of the joints without direct ligamentous connections. This pattern explains why in a normal midcarpal arthrogram contrast material passes proximally into the clefts of the scapholunate and lunotriquetral joints. A normal radiocarpal arthrogram shows no passage of contrast material into the scapholunate and lunotriquetral joint clefts because of the intact scapholunate and lunotriquetral interosseous ligaments. In both ligaments, the palmar and dorsal regions are composed of true ligaments with collagen fascicles, blood vessels, and nerves, whereas the proximal regions are composed of fibrocartilage without blood vessels, nerves, or distinct collagen fascicle orientations. The differences between the two ligaments are limited primarily to the relative thickness of the dorsal and palmar regions and to the merging of the radioscapholunate ligament with the scapholunate interosseous ligament between the palmar and proximal regions. The dorsal region of the scapholunate ligament and the palmar region of the lunotriquetral ligament are the thickest, whereas the palmar region of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and the dorsal region of the lunotriquetral ligament are the thinnest.

4 How much of the proximal surface of the lunate normally articulates with the distal articular surface of the radius in the neutral wrist position?

Under normal circumstances, in a frontal radiographic projection at least 50% of the proximal articular surface of the lunate articulates with the lunate fossa; the average is 60%. If less than 50% of the proximal articular surface of the lunate articulates with the lunate fossa of the radius, ulnar translocation of the lunate is diagnosed. Generally, this translocation results from substantial disruption of the long and short radiolunate ligaments. In posteroanterior (PA) radiographs, substantial information can be gained about the position and orientation of the lunate simply by identifying the shape of the lunate. If the outline of the lunate is quadrangular, the lunate is dorsiflexed; if triangular in shape, the lunate is palmarflexed.

5 What are the normal radiolunate and scapholunate angles as measured on a lateral radiograph?

Before attempting to determine intercarpal or radiocarpal angles, it is imperative to ensure that a standardized quality lateral radiograph of the wrist is obtained. The ulnar margin of the wrist is placed on the x-ray cassette with the shoulder adducted to the side, the elbow flexed 90°, and the forearm positioned in neutral rotation. The wrist is positioned in neutral extension, whereby the axis of the third metacarpal is within 10° of the axis of the diaphysis of the radius. Confirmation of a true lateral radiograph of the wrist can be made by identifying the palmar cortices of the scaphoid tubercle, the body of the capitate, and the pisiform. If the palmar cortex of the pisiform falls between the palmar cortices of the scaphoid tubercle and the body of the capitate, the wrist has been positioned within 5° of a true lateral projection and is within acceptable limits. If the palmar cortex of the pisiform is seen palmar to the scaphoid tubercle, the forearm is in supination; conversely, if the palmar cortex of the pisiform is dorsal to the palmar cortex of the capitate body, the forearm is pronated.

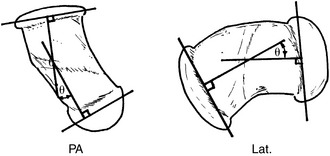

The axis of the radius is defined by bisecting the diaphysis in two locations and connecting the bisection points. The axis of the scaphoid can be determined in several manners. First, the midpoint of the proximal and distal articular surfaces can be estimated, and a line can be drawn between the two points. Second, a tangent to the palmar cortex of the waist of the scaphoid can be drawn. The axis of the lunate is best determined by drawing a cord between the distalmost tips of the palmar and dorsal horns of the lunate. A perpendicular line to this cord defines the axis of the lunate.

Under normal circumstances, the radiolunate angle should measure ±10° (Fig. 144-1). A positive angle indicates dorsiflexion of the lunate, and any value greater than +10° is labeled as dorsiflexion intercalated segment instability (DISI). A negative angle indicates palmarflexion of the lunate, and any value less than −10° is labeled as volarflexion intercalated segment instability (VISI). The normal scapholunate angle is 46°, but it has a rather wide range of variance from 30° to 60°. A scapholunate angle greater than 70° indicates carpal instability. A study of intraobserver and interobserver variability in making such measurements determined that the overall estimated error of measurement averaged 7.4°.

6 How does the relative length of the radius and ulna, termed ulnar variance, change with forearm rotation?

The axis of rotation of the forearm passes through the radial head proximally and the ulnar head distally. The obliquity of orientation of this axis changes the orientation of the radius and ulna during pronation and supination, whereby the two bones are relatively parallel in supination and essentially crossed in pronation. This “crossing” generates a relative change in the distal projections of the two bones, whereby the radius projects less distally in forearm pronation. This change has implications in determining ulnar variance, which is a radiographic measurement of the relative lengths of the radius and ulna. This determination must be made with a PA radiograph taken with the forearm in neutral rotation. A pronated forearm may give the impression of positive ulnar variance (ulna projecting more distally than the radius), and supination may give the impression of a negative ulnar variance (ulna projecting less distally than the radius). Neutral forearm rotation is best ensured by taking the radiograph with the hand and wrist placed flat on the x-ray cassette with no wrist deviation, the shoulder in 90° abduction, and the elbow in 90° flexion.

7 The proximal carpal row moves in what general motion during wrist radial and ulnar deviation? During wrist flexion and extension?

Although there are measurable motions among the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum, the proximal row bones move, in general, in the same overall direction as the wrist. During wrist flexion and extension the proximal row bones also move synchronously with the distal row bones in flexion and extension, respectively. During wrist radial deviation the proximal row bones move primarily in flexion, whereas during wrist ulnar deviation the proximal row bones move primarily in extension. A simplified method for remembering these motion patterns is to realize that the proximal row bones move in the same flexion direction during wrist flexion and radial deviation and in the same extension direction during wrist extension and ulnar deviation.

8 Why is the radioscapholunate ligament no longer believed to be a significant mechanical stabilizer of the scaphoid and lunate?

The radioscapholunate ligament was postulated early to behave as an important stabilizer of the scaphoid and lunate, based largely on its position and orientation. It is located between the long and short radiolunate ligaments and appears to pierce the palmar radiocarpal joint capsule. It is grossly oriented vertically and appears to attach to the proximal surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate. There have even been isolated reports of disruption of this ligament associated with scapholunate dissociation.

However, studies have defined the histology of the radioscapholunate ligament and have shown that it is highly atypical, composed of a large number of blood vessels and nerve fibers, with a minimal content of poorly organized collagen that is covered by a thick layer of synovial tissue. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the radioscapholunate ligament is a termination of an anastomosis of the anterior interosseous artery and palmar radial arch of the radial artery and branches from the anterior interosseous nerve. Material property studies have shown that the radioscapholunate ligament fails at significantly lower load levels and has a much higher strain level than do contiguous ligaments. Therefore, the radioscapholunate ligament behaves more as a mesocapsule than a ligament and should not be considered a stabilizing structure of the wrist.

9 What are the normal anteroposterior and lateral intrascaphoid angles?

The normal PA intrascaphoid angle is less than 35°, and the normal lateral intrascaphoid angle is less than 35°. Patients with scaphoid malunions or nonunions with an intrascaphoid angle greater than 45° are considered at statistically increased risk for development of degenerative changes and show radiographic signs of carpal collapse. It has been found that either trispiral tomograms or computed axial tomograms may enhance the ability to measure these angles. The method used for determining the intrascaphoid angle in either plane measures the angle of intersection of perpendiculars drawn from the cords of the proximal and distal articular surface curves (Fig. 144-2).

10 Describe the normal arterial blood supply of the distal radius

Recent descriptions of the arterial blood supply of the radius have prompted the use of vascularized pedicled bone grafts in the treatment of scaphoid nonunions, avascular necrosis of the scaphoid proximal pole, and Kienböck disease. The nutrient blood vessels entering the distal radius have a consistent pattern that makes identification and isolation relatively easy.

The longitudinally oriented vessels arise from the radial artery, ulnar artery, or posterior division of the anterior interosseous artery. Three major transverse arches interconnect the longitudinal vessels and are named from proximal to distal: dorsal supraretinacular arch (found on the extensor retinaculum), dorsal radiocarpal arch, and dorsal intercarpal arch (both found in the joint capsule proper).

The two distinct types of nutrient vessels are the supraretinacular (SRA; between the extensor compartments) and compartmental (ECA; within the extensor compartments). The SRAs are numbered to reflect the compartments between which they are found. The ECAs are numbered according to the compartment within which they are found.

The identified nutrient vessels are, beginning radially, 1,2 SRA; 2,3 SRA; and 4 ECA. A consistent vessel found within the fifth extensor compartment is called the 5 ECA, but it has no direct penetration into the radius; rather, it is useful as a retrograde conduit to extend the length of a 4 ECA graft pedicled to the dorsal radiocarpal or intercarpal arches, through the proximal anastomosis of the 4 ECA, 5 ECA, and posterior division of the anterior interosseous artery (Fig. 144-3).

Figure 144-3 Dorsal view of carpal region illustrating the arterial blood supply. The supraretinacular arteries are found between the first and second extensor compartments (1,2SRA) and between the second and third extensor compartments (2,3SRA). Arteries are consistently found within the fourth (4ECA) and fifth (5ECA) extensor compartments. C, Capitate; DICA, dorsal intercarpal arch; DRCA, dorsal radiocarpal arch; DSRA, dorsal supraretinacular arch; IA, posterior division of anterior interosseous artery; L, lunate; R, radius; RA, radial artery; S, scaphoid; U, ulna.

11 Name the four principal ligaments of the first carpometacarpal joint

On the palmar surface of the joint is the anterior oblique ligament, also called the “beak ligament.” Near the ulnar extreme of the joint is the ulnar collateral ligament. Dorsally, the ulnar half of the joint is covered by the posterior oblique ligament, whereas the radial half is covered by the dorsoradial ligament. There are no true ligament fibers near the radial extent of the joint, deep to the abductor pollicis longus tendon. The base of the first metacarpal is stabilized to the base of the second metacarpal by the intermetacarpal ligament, which is extracapsular and is not considered a proper carpometacarpal joint ligament.

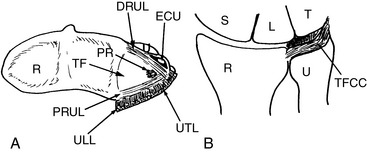

12 Describe the anatomy of the triangular fibrocartilage complex

The triangular fibrocartilage complex is based around the triangle-shaped articular disc, which is interposed between the ulnar head and carpal bones. This articular disc is composed of fibrocartilage; its base is attached to the radius along the distal edge of the sigmoid notch. Along the dorsal margin of the articular disc is the dorsal radioulnar ligament, which connects the dorsal aspect of the sigmoid notch of the radius to the styloid process of the ulna. Extending from the dorsal radioulnar ligament in a distal direction are fibers called the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon subsheath, which variably extends to the base of the fifth metacarpal. Along the palmar edge of the articular disc is the palmar radioulnar ligament, which connects the palmar edge of the sigmoid notch to the area at the base of the ulnar styloid process, called the fovea. Emanating from the palmar radioulnar ligament are the ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments. Near the ulnar apex of the articular disc is a depression called the prestyloid recess, which is generally filled with synovial villi and variably communicates with the tip of the ulnar styloid process. Between the ulnar attachments of the dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments is a region of small blood vessels called the ligamentum subcruentum. The meniscus homologue is the edge of the articular disc distal to the prestyloid recess, which in selected coronal sections resembles the profile of a knee meniscus (Fig. 144-4).

Figure 144-4 Transverse (A) and dorsal (B) views of the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). DRUL, Dorsal radioulnar ligament; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris tendon subsheath; L, lunate; PR, prestyloid recess; PRUL, palmar radioulnar ligament; R, radius; S, scaphoid; T, triquetrum; TF, triangular fibrocartilage; U, ulna; ULL, ulnolunate ligament; UTL, ulnotriquetral ligament.

13 Where is the center of rotation of the wrist?

The center of rotation of the wrist is somewhat controversial because of the complex compound motion of all of the carpal bones. If taken as a unit, wrist movements have been labeled as dorsiflexion (extension), palmarflexion (flexion), radial deviation (abduction), ulnar deviation (adduction), axial rotation (pronation/supination), and circumduction. Any combination of these motions is possible, but the classic axes of rotation of the wrist have been identified as the flexion–extension axis and radial–ulnar deviation axis. Kinematic studies have identified the head of the capitate as the anatomic location at which these axes intersect the wrist. A functional axis, called the “dart-throw” axis, also passes through the capitate but represents the motion created by throwing a dart from wrist extension and radial deviation to flexion and ulnar deviation. It is important to recognize that the axes of rotation are mere approximations, and that each individual carpal bone is considered a rigid body, displaying its own kinematics, which, when summed with the remaining carpal bones, creates the overall motion that we perceive as wrist motion.

14 The midcarpal joint normally communicates with which carpometacarpal joints?

The midcarpal joint is in direct communication with the second, third, fourth, and fifth carpometacarpal joints. Only the first carpometacarpal joint is isolated from the midcarpal joint.

15 Is it normal for the radiocarpal joint to communicate with the pisotriquetral joint? With the distal radioulnar joint?

It is estimated that in 90% of normal adults the radiocarpal joint communicates with the pisotriquetral joint, as evidenced by arthrography. It is considered abnormal for the radiocarpal joint to communicate with the distal radioulnar joint, although such communications do not necessarily imply mechanical instability. Such communications, usually identified with arthrography, imply a defect in the triangular fibrocartilage complex, particularly the articular disc, which normally isolates the two joints from communication. Degenerative changes may occur in the central aspect of the articular disc as early as the third decade and increase in incidence with age thereafter.

16 Are there any normal direct tendinous insertions to any of the carpal bones?

Under normal circumstances only the pisiform has a tendinous attachment, which serves as the insertion of the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon. Anomalous insertions of the abductor pollicis longus and flexor carpi radialis tendons into the trapezium have been reported. The abductor and flexor pollicis brevis originate from the trapezium, whereas the abductor and flexor digiti minimi originate from the pisiform. The origin of the opponens digiti minimi from the hook of the hamate is variable.

17 Is there normally substantial motion between the bones of the distal carpal row?

Kinematic studies, which define motions without reference to force, have demonstrated negligible motion between the bones of the distal row because of the heavy investment of interconnecting ligaments. Between each bone are strong, transversely oriented palmar and dorsal interosseous ligaments. In addition, deep interosseous ligaments connect the trapezoid to the capitate and the capitate to the hamate. Disruptions of these ligaments result from high-energy trauma, typically with substantial additional soft tissue disruption, and are termed axial instabilities.

18 Is it normally possible for the lunate to articulate with the hamate?

Viegas demonstrated two broad categories of architecture of the distal surface of the lunate. The type I lunate, which occurs in two-thirds of normal wrists, has no appreciable articulation with the hamate. Rather, the distal surface of the lunate articulates solely with the head of the capitate. The type II lunate, which occurs in the remaining one-third of normal wrists, has a distinct sagittal ridge with an ulnar-sided fossa for articulation with the proximal surface of the hamate. Type II lunates have a distinct predilection to develop degenerative changes in the hamate fossa as well as to accompany degenerative changes on the proximal surface of the hamate.

19 Describe the dorsal capsular ligaments of the wrist

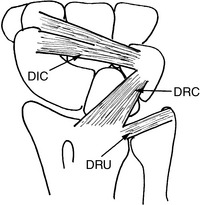

The dorsal capsule of the wrist is reinforced with two major ligaments, the dorsal radiocarpal (DRC) and the dorsal intercarpal (DIC; Fig. 144-5). In the regions between the two ligaments, the joint capsule is devoid of ligament tissue. The DIC ligament connects the trapezoid and scaphoid with the triquetrum, whereas the DRC ligament connects the radius, lunate, and triquetrum. The DIC and DRC ligaments share an insertion on the dorsal cortex of the triquetrum. Proximally, the dorsal radioulnar (DRU) ligament originates adjacent to the radial attachment of the DRC but is not considered a wrist ligament per se. The anatomic arrangement of the dorsal ligaments has been put to use by introducing a fiber-splitting capsulotomy, based on their orientation. This concept promises several advantages, including minimizing scar and stiffness, enhancing visualization and accuracy in orientation, and maintaining stability when entering the wrist from the dorsal side is necessary. The DIC and DRC ligaments can be safely bisected, creating a radially based flap that can be extended even further by dividing the radiocarpal joint capsule from the radius to the level of the radial styloid process. This exposes the radial two thirds of the radiocarpal joint and virtually the entire midcarpal joint. To expose the ulnar third of the ulnocarpal joint, the DRC ligament can be bisected and connected to a capsular incision paralleling the fifth extensor compartment creating a proximally based flap.

20 What is carpal height ratio? How is it determined?

Carpal height refers to the longitudinal length of the carpus from the distal articular surface of the radius to the distal articular surface of the capitate. It is a useful concept clinically because malrotation of the proximal carpal row bones, from problems such as rheumatoid arthritis, scapholunate dissociation, and scaphoid nonunions, may result in shortening of the carpal height. Detection of such shortening helps to classify the severity of the wrist abnormality. The problem with carpal height as a dimensional measure lies in the variability of wrist sizes, which presumably are proportionate to the size of the individual. In an attempt to bypass this variability, the concept of carpal height ratio nondimensionalizes the carpal height. In the classic method, the length of the carpus is defined along the projected axis of the third metacarpal, measured from the base of the third metacarpal to the point at which the projected third metacarpal axis intersects the distal surface of the radius. This measurement is divided by the length of the third metacarpal, also defined along the axis of the third metacarpal. The normal values for the carpal height ratio are 0.054 ± 0.03. This measurement must be made from a standard PA radiograph with the wrist in a neutral position and the entire length of the third metacarpal visible.

Because the third metacarpal is not consistently imaged on standard wrist radiographs, an alternative method for determining the carpal height ratio was developed. The denominator is the greatest length of the capitate, as determined from a standard PA radiograph. The carpal height measurement is made in the same manner as the standard carpal height ratio. Using the alternative method, the normal range of the revised carpal height ratio is 1.57 ± 0.05.

Amadio P.C., Berquist T.H., Smith D.K., et al. Scaphoid malunion. J Hand Surg. 1989;14A:679-687.

Berger R.A., Crowninshield R.D., Flatt A.E. The three-dimensional rotational behaviors of the carpal bones. Clin Orthop. 1982;167:303-310.

Berger R.A., Kauer J.M.G., Landsmeer J.M.F. The radioscapholunate ligament: A gross anatomic and histologic study of fetal and adult wrists. J Hand Surg. 1991;16A:350-355.

Berger R.A. The anatomy of the ligaments of the wrist and distal radioulnar joints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;383:32-40.

Berger R.A. The gross and histologic anatomy of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg. 1996;21A:170-178.

Berger R.A., Bishop A.T., Bettinger P.C. A new dorsal capsulotomy for the surgical exposure of the wrist. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35:54-59.

Cooney W.P., Linscheid R.L., Dobyns J.H., editors. The Wrist: Diagnosis and Operative Treatment. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

Garcia-Elias M. Anatomy of the wrist. In: Watson H.K., Weinzweig J., editors. The Wrist. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:7-20.

Gelberman R.H., Bauman T.D., Menon J. The vascularity of the lunate bone and Kienböck’s disease. J Hand Surg. 1980;5:272-278.

Gelberman R.H., Menon J. The vascularity of the scaphoid bone. J Hand Surg. 1980;5:508-513.

Jiranek W.A., Ruby L.K., Millender L.B., et al. Long-term results after Russe bone-grafting: The effect of malunion of the scaphoid. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:1217-1228.

Linscheid R.L., Dobyns J.H., Beabout J.W., Bryan R.S. Traumatic instability of the wrist: Diagnosis, classification and pathomechanics. J Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A:1612-1632.

Nattrass G.R., King G.J., McMurtry R.Y., Brant R.F. An alternative method for determination of the carpal height ratio. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:88-94.

Palmer A.K., Werner F.W. The triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist: Anatomy and function. J Hand Surg. 1981;6:153-161.

Palmer A.K., Werner F.W. Biomechanics of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop. 1984;187:26-34.

Panagis J.S., Gelberman R.H., Taleisnik J., Baumgaertner M. The arterial anatomy of the human carpus. Part II: The intraosseous vascularity. J Hand Surg. 1983;8:375-382.

Sheetz K.K., Bishop A.T., Berger R.A. The arterial blood supply of the distal radius and ulna and its potential use in vascularized pedicled bone grafts. J Hand Surg. 1995;20A:902-914.

Tountas C.P., Bergman R.A. Anatomic Variations of the Upper Extremity. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1993.

Viegas S.F., Wagner K., Patterson R.M., Patterson R. Medial (hamate) facet of the lunate. J Hand Surg. 1990;15A:564-571.

Youm Y., McMurtry R.Y., Flatt A.E., Gillespie T.E. Kinematics of the wrist. I: An experimental study of radio-ulnar deviation and flexion-extension. J Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60A:423-431.