Morality and Ethics

What They Are and Why They Matter

Objectives

The reader should be able to:

• Define morality and ethics and distinguish between the two.

• Describe the relationship of personal, group, and societal moralities that health professionals must integrate into their role and everyday practice.

• Delineate values of an interprofessional care team that are consistent with professional morality.

• Describe the functions of a health professions code of ethics.

• List three ways in which ethics is useful in everyday professional practice.

• Compare the basic functions of law and ethics in professional practice.

• Identify some laws and policies that protect the personal moral convictions of health professionals while upholding the ethical gold standard of respecting human dignity.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

plateaus

morality

moral development

moral judgment

values

moral values

moral duty

moral character or virtue

personal morality

moral integrity

societal morality

group morality

moral community

professional morality

interprofessional care team

code of ethics

Hippocratic Oath

ethics

ethicists

ethics committees

constitutional law

statutory law

administrative law

licensing laws

common law

state interests

moral repugnance

Introduction

Your adventure into the world of healthcare ethics begins with a story. In this story, and throughout this textbook, you will meet patients, health professionals, families, and others who face challenges posed by their situations and the healthcare environment. Their stories illustrate the types of ethical issues you yourself may face as a caregiver, a member of an interprofessional healthcare team, a patient, or a family member. This book emphasizes basic ethical themes woven through the stories, which allows you to examine them for their unique or interesting characteristics and to assess the role each plays in the overall scheme of professional practice.

The following story introduces you to the Harvey family and the healthcare system into which they are catapulted after the tragic events of a beautiful late spring day.

Professionals who work with patients like Drew know that his care team faces a critical and delicate situation. The rate of “progress” overall is not always constant. It may be marked by periods of rapid improvement interspersed with other periods of almost no perceptible change (plateaus). Moreover, different team members may see varying degrees of improvement because each continues to see the patient through the lens of progress in his or her area of expertise. Yet many insurance plans or other methods of payment for services make little or no allowance for these plateau periods, and treatment is generally discontinued when gains cannot be shown at a consistent rate. In this case, a patient must have a symptom that becomes acute again before treatment can be reinstituted. In summary, although progress eventually does end, the failure to allow for a plateau period often results in the patient’s premature discontinuation from treatment altogether. This is precisely the problem that faces the home care team who is treating Drew Harvey.

Responses to these challenges are not found in the textbooks that deal with the technical skills of your chosen field. You are beginning to use your understanding of morality and how ethics figure into your professional life if you are concerned with one or more of the following questions:

• What is right or wrong conduct for you in this situation and why?

• What are your duties to everyone involved and what are your (and everyone else’s) rights?

• What issues arise because you individually and the team are accountable for the decisions made?

• What are the character traits you want to preserve?

• What constitutes fairness for all patients in similar situations?

To simplify, what is involved in showing Drew and his family that you care? These considerations may even make you think about what type of society you want to help build in your professional career. In all of these areas of your professional life, you are dealing with morality and moral values.

Morality and Moral Values

When morality is mentioned, you may think of what you were told to do or not to do as a child. You are right. That is a part of morality. But morality is a much richer set of ideas than that. From the earliest societies onward, people have established guidelines designed to preserve the very fabric of their society. The guidelines become a natural language and behavior that describe the way things ought to be and what types of things we should value. Most members of society accept these guidelines, allowing the assumptions on which morality is based to prescribe decisions about many aspects of daily life.

Morality is not simply an intellectual exercise. Individuals and groups act out of strong convictions about what is right or wrong and good or bad. We shape our lives and reputations around our beliefs. A part of human development called moral development has been studied to show that adults instill these assumptions into children at a deep emotional level so that acting on the guidelines becomes not only habitual but also provides confidence that the right decision was taken. Viewed collectively, these guidelines constitute a society’s morality.

Morality is relational. It is concerned with relationships between people and how, ultimately, they can best live in peace and harmony. The goal of morality is to protect a high quality of life for an individual, group, or the community as a whole. Ethicists Beauchamp, Walters, and colleagues summarize it this way: “Certain things ought or ought not to be done because of their deep social importance in the ways they affect the interests of other people.”1

Morality is also context dependent. A moral judgment is needed when the particulars of a specific situation arise. When the members of the home care team were faced with being advocates for Drew, they were forced into thinking of him in very specific terms as a unique human in relationship to his family, to social groups such as his university classmates, and to society.

Morality includes values, duty, and character. No matter what the specific circumstances are, you always need to consider three distinct areas of morality.

• Values are the language that has evolved to identify intrinsic things a person, group, or society holds dear. Not all values are moral values of course. For instance, some things are cherished for the beauty, novelty, or efficiency they bring to our lives. Things that uphold our ideas of what is needed for morality to survive and thrive are viewed as moral values. Many moral values describe qualities that support individuals in their desire to live full lives and that allow them to pursue their own basic interests and provide help for others to do so. Others reflect qualities of groups within society that highlight our need for cooperation. We ascribe moral value to character traits of persons, groups, and societies, too, making moral judgments of their praiseworthy or blameworthy traits. A compassionate person is judged as praiseworthy, and a cruel group, such as a gang, as blameworthy; a just society is judged as praiseworthy, and one that holds its citizens in a grip of terror as blameworthy.

• Moral duty is a language that has evolved to describe actions. Not all duty is moral duty, just as not all we value is of moral value. Moral duty describes certain actions required of an individual, group, or society if each is to play a part in preventing harm and building a human foundation that can thrive.

• Moral character or virtue is a language used to describe traits and dispositions or attitudes that set the groundwork for us to trust each other and to provide for human flourishing in times of stress. Common examples are compassion, courage, honesty, faithfulness, respectfulness, and humility. These traits taken together and exercised regularly make up what we mean when we say a person is “of high moral character.” As a child, you acquired parts of your morality from family and friends, reading, television, films, the Internet, religious teaching, and experiences in school.

Personal, Societal, and Group Morality

As a member of the health professions, you must reckon with at least three subgroups of morality: your personal morality, societal morality, and the group morality of the health professions, including the additional considerations that arise in team-delivered care. Fortunately, large areas of overlap are found.

Personal Morality

Personal morality is a collage of values, duties regarding conduct, and character traits each person adopts as relevant for his or her life. It is “who you are” as a unique moral being among others. Becoming intimately familiar with your own moral identity will serve you well. In other words, take care to “know thyself” as counseled by the ancient sage Plutarch in 650 bc. Doing so enhances the self-understanding needed to take on the responsibilities and tasks of your professional role. Your personal morality is also the foundation stone from which you can try to understand and respect the personal morality of patients, colleagues, and others with whom you come into professional contact. To illustrate, the interprofessional team treating Drew Harvey will not be successful if all members are not aware of their own moral values and beliefs as the individuals and team encounter the moral values and beliefs of the Harvey family. Without this deep self-awareness, it is impossible to discern why you respond to another with the feelings, emotions, and judgments that arise in the course of your communications and decisions.

Personal Morality and Moral Integrity

One of the most essential resources in your professional life is your own moral integrity. You experience a sense of integrity when you act in accordance with the values that make up your personal morality. Everyone has an idea of a good life, and integrity is the key to choosing values and actions that support the ideals of that life. The term integrity comes from the Latin integritas, which means unimpaired condition, sound, whole, undivided. It is easy to understand how living by the guidance of your personal morality helps you to maintain a clear sense of “who you really are” when challenges arise. The reward is that you can maintain a sense of unified purpose, direction, and action in different kinds of situations. Edmund Pellegrino summarizes it well:

Classically, personal integrity has been understood as a person’s commitment to live a moral life. The woman or man of integrity is honest, reliable, and without hypocrisy. He will admit mistakes, be remorseful, and accept the guilt that follows wrongdoing. The person of integrity fulfills the obligations of his private and his professional life, which are consistent with each other. He or she follows his conscience reliably and predictably. This pursuit is intrinsic to the person’s identity. To violate it is to violate that person’s humanity.2

Put simply, moral integrity is the awareness and reward of doing the morally right thing. You can be sure that the members of Drew’s team are thinking about their own integrity as each weighs what to do. Sometimes a breach of integrity by you or others is necessary to understand the empowering function it plays in cheating you out of the feeling that all is well. For instance, experiencing the effects of a friend who lies to you to cover a mistake helps you to understand why you do not want to take the same course.

Societal Morality

Large components of personal morality are drawn from a morality that is shared with others in society. Societal morality contains values and ideas of duty or character that spring from deep cultural beliefs about humans and their relationship with God (or the gods in some cultures), with each other, and with the natural world. Societal morality becomes codified in laws, customs, and policies. In the United States, the founding fathers and mothers who risked crossing oceans and leaving behind almost every security tried to capture the common denominator of their societal morality in the statement “all are created equal” and therefore everyone should have an equal chance at “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Almost always, some tensions exist between personal and societal morality. These tensions are played out in societal debates, with individuals and groups taking sides to try to influence laws and policies. Two current healthcare-related debates deal with the morality of abortion and assisted suicide. Others focus on the appropriate limits of the use of the natural environment for human purposes; the moral rights of embryos, undocumented immigrants, prisoners, or others; and the use of taxes for the purpose of providing basic human services to poor people. Can you name some others? A free society always generates lively debate, and your personal values serve as one source of engaging meaningfully.

Group Morality: The Health Professions and Interprofessional Teams

Every member of society, except perhaps the most isolated recluse, joins or is swept into one or more subgroups of society by virtue of being a member of a religious group, a workplace culture, a club, a service organization, an ethnic cluster, or other deep group affiliation. The moral guidelines adopted by a subgroup constitute its group morality. A good way to capture the essence of group morality is to think of it as a moral community within the larger society. One such community is the health professions.3 Thinkers from various fields of study have noted that professionalism involves specific moral and other assumptions, a subset of group morality that the authors of this text suggest can be summarized as professional morality. Professional morality embraces moral values, duty, and character traits that do not apply equally or at all to others in society, although it goes beyond a strictly personal morality to a public statement. For instance, citizens in general are not morally required to offer help to another in need of medical attention. You are. Citizens are not morally required to keep in confidence information they hear about another. You are. Citizens are not morally required to be nonjudgmental about another’s character. You are. Your fiduciary duty as a health professional is discussed in other parts of this book, notably in Chapters 2 and 11.

As you saw in Drew Harvey’s process of recovery, a segment of the professional moral community is the interprofessional care team. Almost every care plan involves a team of professionals working together. Team rules embody, but at times may conflict with, one or more general moral guidelines that make up one’s personal or individual professional morality. Remember that effective teams are grounded in a shared purpose to support the common good in healthcare,4 which is not about what is best for a singular practitioner, but rather about what is best for the patient. Because of this value on common goals, assumptions of cooperation and good team membership, such as loyalty to and honesty with each other, are core to the interprofessional healthcare team’s functioning. Professionals must communicate, collaborate, and negotiate across professional boundaries to ensure the delivery of quality care.5 Understanding the strengths and challenges of this form of healthcare delivery and the group morality aspects of it is so important that a whole chapter is devoted to the interprofessional care team (see Chapter 7).

One significant resource that describes the details of professional group morality as it applies specifically to your chosen field is the code of ethics of your profession.

Professional Codes of Ethics

Your profession’s code of ethics today has emerged from a historical understanding that professionals are in a position to have a powerful positive or harmful influence on others. The code is a visible acknowledgment that, as a group, professionals are granted societal privileges; however, with these privileges comes the responsibility to conduct themselves in ways that are acceptable not only to other members of the group but also to the larger society. The ancient oaths, such as the familiar Hippocratic Oath (Box 1-1), were statements that swore their group intent to the gods to practice in specific ways that reflected a commitment to human well-being. Although codes do not require the actual swearing in of the ancient oaths, the oaths often are recited during ceremonies marking the student’s progress toward becoming a professional.

Most codes are produced by the profession’s national association and reflect the collective wisdom about how members should conduct themselves as professionals, which gives the items in the code an authoritative collective voice for that profession. A shortcoming of the current approach to codes of ethics is that almost all focus primarily or solely on the moral guidelines of a single profession, leaving as secondary or absent the fact that care is almost always delivered by interprofessional care teams.

Be that as it may, why is knowledge of your code important?

• Your code is your profession’s most succinct statement of its professional (group) morality. It is literally a codified shorthand of your larger moral role in society as a member of a special moral community.

• Your code is a protector of your own best interests as a professional committed to a patient’s well-being. Patients or families, policymakers, or others may ask you to do things that you judge are not in accordance with your professional moral judgment. The code likely provides support for your position if your deliberations fall within the common denominator of the moral guidelines detailed in your code.

• Your code also provides a measuring rod for you to engage in continual self-improvement in practice. In a complex situation, you can refer to it to ask “How do I measure up against the moral standards and specific directives outlined in my code?” and “How am I doing?”

Institutional Policies

The group morality of the health professions should be embedded in the policies, customs, and practices of healthcare institutions. The world would be perfect if members of the professions could rely completely on these policies; fortunately, they are reliable guides for most decisions you will have to make. The idea of a professional embodies a moral conviction that each and every patient will get the type and amount of care that is needed. The identified patient is the sole focus of an interprofessional healthcare team’s interventions.6 But what about other patients with similar clinical conditions? Policies function to try to create a just environment for all like- situated patients; this in turn may mean that, because of scarce resources, limits are set, which result in practices that do not seem to place the individual patient’s well-being at the front and center of operations. The first instinct for many professionals is to see institutional policy as so far removed from the real purpose of healthcare that they believe the interest of patients have been unnecessarily compromised for other goals of the institution, such as efficiency, financial solvency, or competing priorities not related to patient care. Exemption from having to abide by an institutional policy that a person or group believes is morally questionable may not be assured. The predicament in which the health professionals find themselves regarding Drew Harvey’s care presents a traditional professional morality challenge because we can safely assume that most of them find it personally wrong to fudge details about his immediate rate of improved function. At the same time, their duty of due care for him means that some of them probably blame institutional policies governing home healthcare as being unfair policy.

These situations are by no means limited to the health professions. People of strong moral grounding through the ages have had to come to grips with institutional policies that grate against their personal or group moral values and duty. A historical example comes from another professional group, the clergy.

The Christian Reformation in 1500s Europe took place when the morality of some religious leaders came into conflict with the policies and patterns of moral conduct in their religious institution. The famous statement, “Here I stand. I can do no other,” exemplifies the moral breaking point persons or groups sometimes reach. The phrase is attributed to reformist priest Martin Luther, as he nailed 95 objections to the official church policy regarding the practice of indulgences to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany.

The good news is that overall, the policies of healthcare and other institutions almost always help prevent you from having to participate in processes, procedures, or other activities that run counter to your personal and professional moral integrity. Before accepting a position in an institution, it is always a good idea to become well informed of the job expectations outlined in its policies.

From the Moral to the Ethical

You have learned that morality provides a basis for moving successfully through many daily actions: I will stop at this stop sign; our team will not cheat on this play. However, occasionally the naturalness comes to a gradual or screeching halt. Should I trust my feelings about what I am seeing in the treatment of this patient? Does our past experience on the team count here? The authors have heard several metaphors that characterize this situation. “I was strolling along and stubbed my toe, which made me stop and pay attention.” “I thought I saw the solution clearly, but the edges went blurry and grey.” “I call it my ‘oops!’ moment!” “Suddenly I felt like I was up a creek without a paddle.”

These “Stop—Look—Listen!” reactions are a means of protecting ourselves against straying from the morality that we have learned to rely on habitually as we go about our daily lives. The reactions signal that something does not “fit right” in the situation. Take them as healthy alerts that something potentially harmful is threatening your moral sensitivity and practices. Fortunately, these push-back reactions also can function in societies, as the subsequent example illustrates for your reflection.

Ethics is the discipline that waits in the wings as a health-restoring resource when moral policies and practices fail to do the job alone.7 Ethics takes moral assumptions that are operative at the personal, group, or societal level and provides a language, some methods, and tools for evaluating them to create a better path for yourself and others.

Ethics: Study and Reflection on Morality

Ethics is a systematic study of and reflection on morality: “systematic study of” because it is a discipline that uses special methods and approaches to examine moral situations, and “reflection on” because it consciously calls assumptions about our morality into question. The goal is to highlight what does and does not fit in a particular situation. Ethics is a process that sees “what is” and asks “what really ought to be?”

Without this level of questioning and reflection, individuals, groups, and whole societies have no way to create more viable habits or customs as situations change. Originally, approaches to moral analysis were developed as areas of philosophy and theology. Today, the social sciences and other disciplines have added to the number and types of approaches. You will have an opportunity to learn more about them in Chapter 4.

The study of ethics takes the following question as its unchangeable gold standard.

Starting from this standard, the following questions arise in respect to specific situations:

• Do our present moral values, conduct, and character traits pass the test of further examination when measured against the gold standard?

• When conflicts arise, which moral guidelines are helpful in this situation, and why?

• When a new situation presents uncertainty, what new thinking is needed and why?

• Overall, what aspects of present moralities most reliably guide individuals, groups, and societies on a new path consistent with honoring the gold standard?

You were introduced to codes of ethics previously in this chapter. How do they fit into the larger picture of ethics as we are now describing it? Fundamentally, they are a combination of moral, practical, and, in some areas, legal starting points for ethical deliberation. Take the case of the decision that faces the team members treating Drew Harvey in his home setting. Your code or even the combined codes of all of your team members does not do the full work of ethics for you and your teammates. In additional to the guidelines in the code, you must add your own critical thinking and attention to morally complex problems with the help of ethical theory and methods.

The websites and professional literature of many health professions associations now offer ethics case examples or opinion pieces that apply to your profession. Fortunately, many now also feature situations that place you as a member of an interprofessional care team. Such adjuncts to ethical codes are superb learning opportunities for you.

Ethicists and Ethics Committees

Ethicists have as their primary career activity the work and teaching of ethics. Medical ethicists or healthcare ethicists specialize in healthcare issues. At the level of clinical practice, they consult with care teams and families to help them recognize and analyze problems that arise, which helps to clarify the moral values, duties, and other aspects of morality in a specific situation. The goal of such consultation is to help resolve difficult moral problems if possible. Ethicists can often encourage individuals and teams not to be driven solely by time or other external pressures so that more thoughtful conclusions can be reached in complex moral situations (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 Copyright ScienceCartoonsPlus.com.

Ethicists also work as consultants in the design of ethical policies and institutional practices.

In many institutions today, ethics committees serve the same purpose as an individual ethics consultant and usually include ethicists, other professionals, and laypeople. In this regard, they function as another type of care team. But ethics is not the work of ethic consultants or ethics committees only. Ethics is the work of everybody.

The Moral and Ethical Thing to Do

You commonly hear someone say, “That is the moral and ethical thing to do.” The terms moral and ethical are used interchangeably. We suggest you use them more purposefully, however, because after what you have just learned, that phrase should have more meaning for you. The “moral thing to do” means that the traditions, customs, laws, and other markers that an individual, group, and society call on for habitual moral guidance allow you to proceed with confidence in your course of action. The “ethical thing to do” means that the course of action that would be taken in the everyday moral walk of life has been reflected on and your moral judgment has dictated that it still seems the right thing to do (or refrain from doing). Fortunately, most situations allow you to act both morally and ethically.

Use of Ethics in Practical Situations That Involve Morality

The scholarly discipline of ethics has always been interesting from the point of view that its subject matter has immediate relevance for everyday life. Aristotle and others in the classical Greek era called ethics “practical philosophy.” This interest has led to the development of ethicists and ethics committees discussed previously. We now turn to your own ethical formation as a health professional. In this chapter, you have read that ethics is about studying and reflecting on moral situations, such as the ones the interprofessional care team treating Drew Harvey face. In subsequent chapters, you will be introduced in detail to four aspects of ethical competence that prepare you to think and act in a manner consistent with the gold standard of human respect for all. We give you a glimpse of them now: Recognize, Analyze, Seek Resolution, and Act.

Recognition

Recognition of an ethical problem is the first step to becoming competent in this area of practice. Learning the terms and concepts of ethics is analogous to mastering any area of professional expertise, such as pharmacology or physiology. This book is designed to give you the knowledge base you need. You will also learn that to recognize you are in “ethics territory” in a situation in which you must apply ethical reasoning. Chapter 4 details how ethical reasoning is related to but distinct from other types of clinical reasoning needed for professional competence.

Analysis

Analysis of moral challenges in a situation is the reward of mastering a knowledge base and learning to apply ethical reasoning. One type of analysis is the process you engage in when two parts of your own morality collide: “I shouldn’t lie to my spouse, but the truth will be bitter and I shouldn’t hurt her either.” Analysis also requires you to pay attention to the deeply human aspects of the specific situation you are facing.

Answers to these questions require that your own analysis about his situation include a consideration of the facts available to you and your reasoning about right and wrong, the conflicting priorities he faced, the psychological dynamics he had to navigate, his professional obligations, and the practical consequences of his alternatives. Analysis uncovers relevant details to help inform possible directions toward resolution and purposive action. Although Galen’s situation was extreme, the process of analysis you used to engage his conflict is the same process you probably used to think about which direction Drew Harvey’s care team ought to take.

Seek Resolution

The point of ethical reasoning is to work toward resolution of a complex moral situation. Obviously, this is what Drew Harvey’s healthcare team needs to do. One approach to finding resolution is to try to build consensus among the various concerned parties (e.g., team members, the patient, his family, the institution). Some ethics approaches focus on how to resolve issues when no consensus is reached or when consensus does not seem to fully address the moral conflicts embedded in the situation.8 In many healthcare institutions, the ethics consultant or ethics committee can be called upon to add insight and counsel in the most challenging instances.

Action

Purposive action stems from analysis and thoughtful work toward resolution. The health professionals involved with Drew Harvey’s potential discharge from their care are looking for direction to act purposefully and preserve the moral integrity of the whole community.

Legal Protections for Your Ethical Decisions

Legal protections come in the form of case law (constitutional law) as a result of court decisions from the lowest courts to the supreme or high courts of the land that set legal precedence for future similar situations; legislation (statutory law or statutes) passed through Congress or parliament; and legally binding regulations (administrative law) promoted through a state’s or national government’s regulatory bodies, such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

How Does Law Factor into Professional Morality?

National and state or provincial laws are a big help for the most part. They embody and codify moral values and types of duty that should govern individual and institutional conduct related to the health professions and provide legal interpretations of key professional issues. For example, laws outline the conditions under which health professionals have the license or privilege to practice in a state, province, or territory. Laws provide clarification about informed consent, confidentiality, and conditions related to a health professional’s competence, among many other issues. Each of these is based on moral values relevant to the health professional and patient relationship, on an understanding of professional duty, and on societal expectations of the type of moral character professionals cultivate and exhibit. Many health professions programs today wisely include a course on healthcare law governing their profession; if you do not have one in your program of study, web and other resources also are available for you to learn about the legal dimensions of your practice.

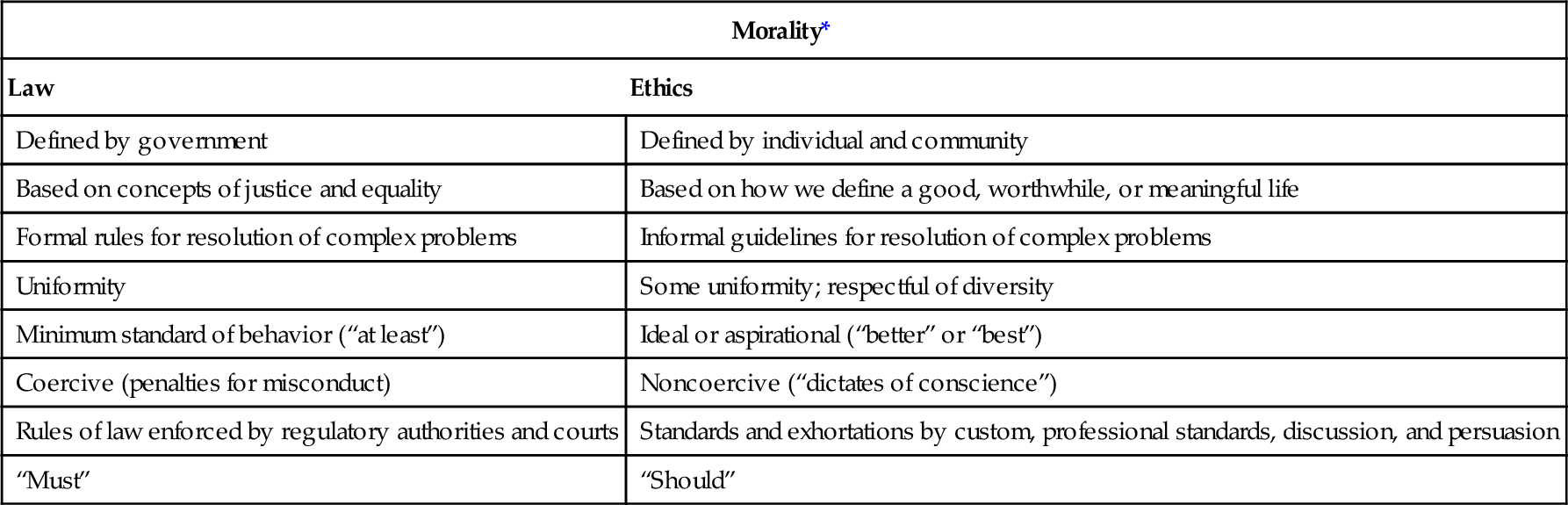

As a general rule, laws and moral standards of a society seem to support each other. But you should not expect the same guidance from laws or policies that you receive from ethical codes and vice versa. Each has its special function. For a succinct summary of major distinctions between law and ethics, the subsequent chart from the work of Jennifer Horner is helpful.

| Morality* | |

| Law | Ethics |

| Defined by government | Defined by individual and community |

| Based on concepts of justice and equality | Based on how we define a good, worthwhile, or meaningful life |

| Formal rules for resolution of complex problems | Informal guidelines for resolution of complex problems |

| Uniformity | Some uniformity; respectful of diversity |

| Minimum standard of behavior (“at least”) | Ideal or aspirational (“better” or “best”) |

| Coercive (penalties for misconduct) | Noncoercive (“dictates of conscience”) |

| Rules of law enforced by regulatory authorities and courts | Standards and exhortations by custom, professional standards, discussion, and persuasion |

| “Must” | “Should” |

From Horner J: Morality, ethics and law: introductory concepts. Semin Speech Language 24(4):269–273, 2003.

* Widely held societal values (universal, ultimate, impartial, other-regarding).

Protections

As you think about living within the dictates of your conscience and professional morality in seriously contended moral issues, keep in mind the following general resources available to professionals through laws and policies.

Licensing Laws

Professionals become certified, registered, or licensed to practice nationally and within a particular state or jurisdiction after the completion of all formal professional preparation requirements. Written into the licensing laws that govern professional practice are both responsibilities and protections or rights. Among the rights is your right to practice within the dictates of your practice guidelines and own convictions. This right is weighed against the reasonable expectations of patients or clients who come to you for professional help.

State Interests

Common law (i.e., law that comes into practice over time through the lived life of a community) dictates that there are state interests, that is, a responsibility to intervene on behalf of persons under four extreme circumstances: (1) to save their life, (2) to prevent their suicide, (3) to protect them from harm as an innocent third party, and (4) to protect them as a bearer of the “integrity of the professions.” This final cause for legal intervention obviously applies to professionals only. It has evolved because of circumstances in which health and other professionals have been faced with requests by patients or clients or have been dictated to by policies to act in ways that are believed by a court to be contrary to the true moral and legal social role of a professional. This protection must be appealed to on a case-by-case basis.

Moral Repugnance

Moral repugnance came into the health professions literature with the U.S. Supreme Court decision Roe v Wade, which made abortion a legal right. A conscience clause allows individuals who believe that participation in abortion procedures is morally wrong to be exempt from having to do so. An important aspect of this provision is that the procedure itself is key to whether this exemption is upheld. It is not a protection against, for example, your refusal to treat patients whose lifestyles are morally unacceptable to you. Therefore, it is a limited but important protection. Many have argued that a request to assist in the lethal procedures that cause death in capital punishment fall under the protection of this notion. The same is true should medically administered euthanasia become legally permissible in the United States as it is in the Netherlands or Belgium. This conscience clause operates as a conscientious objection analogous to conscientious objection in situations of war.

Limits of Protection

In summary, society and many institutions that deliver high-quality healthcare are aware of the need for your personal protection so that in your professional role you can perform acts that the lay person cannot, and you are provided a recourse in those hopefully rare circumstances in which you feel morally compromised by something you are expected to do in that role. Some legal cases involve the whole interprofessional care team, but more often, laws are still designed with an individual legal agent in mind. In either situation, the final burden of proof rests on why you or the team refuses on moral grounds to participate in an action or take a position contrary to the norm. You may be able to find support in one of the previously mentioned legal mechanisms that have been developed. The best recourse is to know your own moral values and reasons for your decisions and have good justifications to support them. In team situations, there is strength in engaging the range of moral values and understanding of what morality requires of each individual. Fortunately, most health professionals seldom experience the deep, troubling tension of being in a situation they believe compromises their personal and professional moral convictions.

Summary

This chapter is but one step in your lifelong journey in professional ethics. You have chosen a career path that requires complex moral judgments regarding patient care, health policy, and other aspects of professional life. Many of these judgments are made within the context of an interprofessional care team. This chapter has introduced you to some basic ways of thinking about the sources of morality on which you can draw, the general relevance of ethics to your everyday professional life, and some legal protections you can expect. As you study the subsequent chapters, you will be better able to appreciate the contribution of these considerations.

Questions for Thought and Discussion

1. Search your local or other national news source for a story about healthcare that involves moral values or duties.

a. What is the basic point of the piece? What is the reporter saying?

b. What does the writer or reporter suggest are the main moral issues raised in this situation? Do you agree? Why or why not?

2. You learned in this chapter about personal, group, and societal moralities. Identify a value in your own personal morality and describe that value’s relationship with the morality of a group or society in which you currently live. Use the following box to compare the moralities.