Complications of Labor and Birth

Objectives

2. Discuss four factors associated with preterm labor.

3. Describe two major nursing assessments of a woman in preterm labor.

4. Explain why tocolytic agents are used in preterm labor.

5. Interpret the term premature rupture of membranes.

6. Identify two complications of premature rupture of membranes.

7. Differentiate between hypotonic and hypertonic uterine dysfunction.

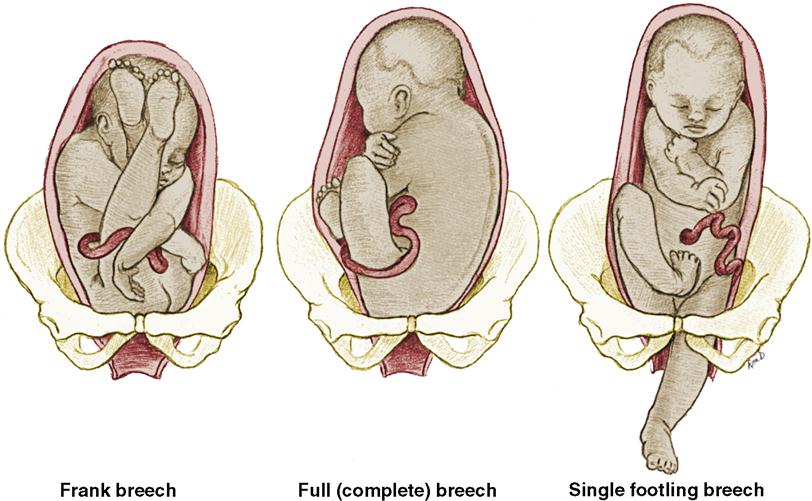

8. Name and describe the three different types of breech presentation.

9. List two potential complications of a breech birth.

10. Explain the term cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD), and discuss the nursing management of CPD.

11. Define and identify three common methods used to induce labor.

12. Explain why an episiotomy is performed, and name two basic types of episiotomies.

13. Describe three types of lacerations that can occur during the birth process.

14. List two indications for using forceps to deliver the fetus.

15. Describe vacuum extraction.

16. Define precipitate labor, and describe two nursing actions that should be taken to safeguard the baby.

17. Review the most common cause of rupture of the uterus during labor.

18. Describe umbilical cord prolapse, and state two associated potential complications.

19. List three potential complications of multifetal pregnancy.

20. Discuss five indications for a cesarean birth.

21. Describe the preoperative and postoperative care of a woman who is undergoing a cesarean birth.

22. Discuss the rationale for vaginal birth after a prior cesarean birth.

Key Terms

amnioinfusion (ăm-nē-ō-ĭn-FŪ-zhăn, p. 294)

amniotomy (ăm-nē-ŎT-ŏ-mē, p. 290)

augmentation of labor (ăwg-mĕn-TĀ-shŭn, p. 289)

caput chignon (kap´ət´shën´yän, p. 293)

cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) (sĕf-ă-lō-PĔL-vĭc dĭs-prō-PŎR-shŭn, p. 286)

cesarean birth (sĕ-ZĀR-ē-ăn, p. 295)

chorioamnionitis (kō-rē-ō-ăm-nē-ō-NĪ-tĭs, p. 284)

dystocia (dĭs-TŌ-sē-ă, p. 284)

episiotomy (ĕ-pēz-ē-ŎT-ō-mē, p. 291)

hydramnios (hī-DRĂM-nē-ŏs, p. 293)

hypertonic uterine dysfunction (hī-pĕr-TŎN-ĭk Ū-tĕr-ĭn, p. 285)

hypotonic uterine dysfunction (hī-pō-TŎN-ĭk, p. 285)

multifetal pregnancy (mŭl-tē-FĒ-tăl, p. 294)

Nitrazine paper test (NĪ-tră-zēn, p. 284)

oxytocin (ŏks-ē-TŌ-sĭn, p. 290)

precipitate labor (prē-SĬP-ĭ-tāt, p. 293)

prolapsed umbilical cord (PRŌ-lăpst ŭm-BĬL-ĭ-kăl, p. 294)

prostaglandin (PGE2) gel (p. 290)

tocolytic agents (tō-kō-LĬT-ĭk, p. 283)

trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) (p. 300)

vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) (p. 300)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Leifer/maternity

Labor and birth usually progress with few problems. However, when complications occur during labor, they can have devastating effects on the maternal-fetal outcome. Health care providers must quickly and accurately identify the nature of the problems and intervene to reduce or limit detrimental effects on the mother and newborn. This chapter discusses high-risk intrapartum care. Nursing care is incorporated throughout the chapter.

Preterm Labor

Preterm labor is defined as the onset of labor between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation. It occurs in approximately 12% of pregnancies and accounts for most perinatal deaths not resulting from congenital anomalies. Preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes are the two most common factors that lead to preterm birth. Preterm birth has great significance for society because of the high rate of perinatal deaths and the excessive financial cost of caring for the preterm newborns. One of the Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) goals is for 90% of all pregnant women to have prenatal care starting in the first trimester and to reduce preterm labor and delivery. Early prenatal care makes it possible for the woman to reduce or eliminate some risk factors that contribute to preterm labor.

The criteria for diagnosing preterm labor include:

• Gestation between 20 and 37 weeks is considered preterm

• Late preterm is between 34 and 36 completed weeks of gestation

• Documented uterine contractions every 5 to 10 minutes lasting for at least 30 seconds and persisting for more than 1 hour

Associated Factors

The exact cause of preterm labor is unclear; however, several risk factors are known. Because epidemiologic data have shown some risk factors to be avoidable, there are some promising avenues for both prevention and treatment. Increased risk factors include poor prenatal care; infections, including periodontal (dental) infections; nutritional status; and sociodemographics (socioeconomic status, race, and lifestyle). Preterm labor, followed by preterm birth, has been associated with maternal anemia; urinary tract infection; cigarette smoking; and use of alcohol, cocaine, and other substances, all of which are potentially avoidable risk factors. In addition, alterations in maternal vaginal flora by pathogenic organisms (e.g., Chlamydia or Trichomonas organisms, bacterial vaginosis) are associated with preterm labor. The risk of spontaneous preterm birth increases as the length of the cervix decreases. The length of the cervix can be measured by transvaginal ultrasound.

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical manifestations of preterm labor are more subtle than for term labor. Health care providers and pregnant women need to know the warning signs of preterm labor. The health care provider should be notified of the following signs or symptoms:

Assessment and Management

Early prenatal care and education about prevention and the warning signs of preterm labor are extremely important to prevent preterm birth. The nurse should review the signs and symptoms that place a woman at risk for preterm labor and emphasize the importance of reporting the signs for prompt care in order to delay the newborn’s birth until the fetal lungs are mature enough for extrauterine life. Open communication between the woman, nurse, and other health team members is essential for collaborative care and successful prevention of preterm births. Once the woman has been identified as at high risk for preterm labor, the use of various strategies and more intense surveillance allows earlier identification and intervention for preterm labor.

When amniotic membrane integrity is lost, a protein in the amniotic fluid, called fibronectin, will be found in vaginal secretions. A vaginal swab for fetal fibronectin can help the physician decide which women should be treated most aggressively to stop preterm labor (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007).

Infection is associated with preterm births. Identification and eradication of offending microorganisms that cause inflammation in the lower reproductive tract lessen the inflammatory response and provide a healthier cervix, thereby decreasing the incidence of preterm labor. Antibiotics may be prescribed prophylactically for women at risk for preterm labor, with premature rupture of the membranes, or with group B streptococcal cervical cultures.

The physician may order uterine activity monitoring at home for women at risk for preterm labor. The monitor assesses contractions only; it does not assess fetal heart rate. In the delivery unit, the pediatrician should be present to assist in assessment and resuscitation of the preterm newborn, and equipment and a working incubator for transportation to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) should also be available.

Stopping Preterm Labor

Once the woman is admitted to the hospital and the diagnosis of preterm labor is made, management focuses on stopping the uterine activity (contractions) before the cervix dilates beyond 3 cm, or “the point of no return.” The initial measures to stop preterm labor include identifying and treating any infection, restricting activity, ensuring hydration, and using tocolytic drugs (Table 14-1). The woman is placed on modified bed rest with bathroom privileges and is encouraged to maintain a lateral position. Assessment of uterine activity by palpation provides valuable information. The nurse communicates with the woman to help reduce her anxiety and concerns about fetal well-being and birth. Anxiety produces high levels of circulating catecholamines, which may induce further uterine activity. Explaining the planned care and procedures can reduce the patient’s fear of the unknown. Some drugs used as tocolytics may have an effect on carbohydrate metabolism and are used with caution in the diabetic patient.

Table 14-1

Drugs Used to Stop Preterm Labor (Tocolytics)

| Tocolytic Drug | Adverse Effects | Comments |

| Ritodrine (Yutopar) (β-adrenergic agonist) | Cardiovascular: maternal and fetal tachycardia Pulmonary: shortness of breath, chest pain, pulmonary edema, tachypnea Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ileus Central nervous system: tremors, jitteriness, restlessness, apprehension Metabolic alterations: hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia |

Approved by FDA but not in popular use. Side effects are dose related and more prominent during increases in the infusion rate than during maintenance therapy. ECG clearance suggested; hypertension and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus are contraindications. |

| Magnesium sulfate | Depression of deep tendon reflexes, respiratory depression, cardiac arrest (usually at serum magnesium levels >12 mg/dL) Less serious side effects: lethargy, weakness, visual blurring, headache, sensation of heat, nausea, vomiting, constipation, oliguria Fetal-neonatal effects: reduced heart rate variability, hypotonia |

Adverse effects are dose related, occurring at higher serum levels. FHR and maternal vital signs must be monitored during labor and postpartum. |

| Indomethacin (prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor) | Epigastric pain, gastrointestinal bleeding; increased risk for bleeding; dizziness. Fetal effects: may have constriction of ductus arteriosus and decreased urinary output; decreased urinary output is associated with oligohydramnios, which may result in cord compression Respiratory distress syndrome |

Not used after 32 weeks’ gestation or for more than 48-72 hours. Observe for maternal bleeding and adverse FHR patterns. |

| Nifedipine (Procardia) (calcium channel blocker) | Maternal flushing, transient tachycardia, hypotension; use with magnesium sulfate can cause serious hypotension and low calcium levels | Monitor for hypotension and increased serum glucose levels in those with diabetes. |

| Terbutaline (Brethine) (β-adrenergic agonist) | Tachycardia; monitor vital signs Shortness of breath; may cause hyperglycemia |

Approved for investigational use and is widely used. Must not be used longer than 48 to 72 hours (FDA 2011) |

| Corticosteroids | Increased blood sugar | Given to accelerate production of surfactant, increase fetal lung maturity, and prevent neonatal intracranial hemorrhage |

| Betamethasone, dexamethasone | Monitor mother and newborn closely: mother for pulmonary edema and hyperglycemia, and newborn for heart rate changes | Given to mother 24-48 hours before birth of preterm newborn (<34 weeks of gestation) because it can hasten lung maturity |

Data from Clayton, B.D., Stock, Y.N., & Cooper, S.E. (2010). Basic pharmacology for nurses (15th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby; Creasy, R., Resnik, R., Iams, J., Lockwood, C., & Moore, T. (2008). Creasy & Resnik’s maternal-fetal medicine (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders; London, M., Ladewig, P., Ball, J., & Bindler, R. (2006). Maternal & child nursing (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2003). Management of preterm labor. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 101, 1039–1047.

Tocolytics should not be used in women who are hemorrhaging because vasodilation may increase bleeding. If signs of fetal distress are noted, tocolytics may not be used if adequate survival therapy is available in the NICU. Tocolytics are usually not effective in a cervical dilation of 5 cm or more.

The woman should be asked to report any vaginal discharge (color, consistency, and odor). Baseline maternal vital signs are important and may provide clues of infection. Tachycardia and elevation of temperature can be early signs of amniotic fluid infection.

Fetal surveillance includes external fetal monitoring; fetal tachycardia of more than 160 beats/minute may indicate infection or distress. Fetal movement and biophysical profile assessment with the nonstress test (NST) provide information about fetal well-being. Special fetal assessment tests can be performed, such as measuring lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio to determine fetal lung maturity.

Resting in the lateral position increases blood flow to the uterus and may decrease uterine activity. Strict bed rest may have some adverse side effects, which include muscle atrophy, bone loss, changes in cardiac output, decreased gastric motility, and gastric reflux. In addition, bed rest may result in depression and anxiety in the woman.

Hydration is encouraged, and intravenous fluids are often administered to increase vascular volume and prevent dehydration. The pituitary gland responds to dehydration by secreting antidiuretic hormone and oxytocin. Therefore, preventing dehydration will prevent oxytocin from being released. A baseline admission complete blood count is useful for determining whether there has been a decrease in the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

Use of tocolytic agents is an additional measure undertaken to stop uterine activity. The goal of tocolytic therapy is to delay delivery until steroids can hasten lung maturity of the fetus. Several drugs can be used, but none is without side effects. The nurse must know the adverse effects of the drug given and monitor the woman for their possible appearance. β-Adrenergic-agonist drugs such as terbutaline (Brethine) are often used as tocolytics. Terbutaline should not be used for longer than 48-72 hours and should not be used for home or maintenance therapy to prevent preterm labor. Terbutaline therapy may result in adverse effects to both the mother and fetus (FDA, 2011). Propranolol should be available to reverse adverse effects. Magnesium sulfate is also an effective tocolytic, and calcium gluconate 10% should be available to aid in reversing any toxic effects. Nursing responsibilities with this drug include hourly monitoring of maternal vital signs and oxygen saturation. Indocin (indomethacin) is a prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor that can be used as a tocolytic drug. Indocin can prolong maternal bleeding time, and the woman should be observed for unusual bruising. Fetal monitoring is essential when Indocin is used because it may have adverse effects on the fetus if used for more than 48 hours. Calcium antagonists, such as nifedipine (Procardia), reduce smooth muscle contractions of the uterus, and the woman must be monitored for hypotension (Iams, Romero, & Creasy, 2009).

Chapter 13 discusses the nurse’s role regarding assessment for magnesium sulfate toxicity. Intervention for magnesium sulfate administration is the same as when given to prevent seizures in gestational hypertension.

Promotion of Fetal Lung Maturity

Promotion of fetal lung maturity is a goal in management because respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is a common problem in preterm newborns. Respiratory distress can be reduced if steroids, such as betamethasone or dexamethasone, are given to the mother at least 24 to 48 hours before the birth of a newborn who is less than 34 weeks’ gestation. After birth, preterm newborns are commonly treated prophylactically with surfactant therapy to reduce the risk of RDS.

Nursing Care Related to Pharmacologic Therapy

All tocolytic therapies have maternal risks; therefore, continuous assessment for effects of the drugs is indicated during administration. Intravenous tocolytics are given according to the institution’s protocol. Accurate intake and output, bilateral breath sounds, changes in vital signs, and mental status are closely monitored to identify early signs of fluid overload and pulmonary edema. If the woman is receiving β-adrenergic-agonist drugs such as Terbutaline, a heart rate of 120 beats/minute or greater, or a decrease in blood pressure to less than 90/40 mm Hg, should be immediately reported to the health care provider. These findings may indicate profound hemodynamic changes, including decreased ventricular filling time, decreased cardiac output, and myocardial infarction may occur if the drug is not discontinued. A pulse oximeter and arterial blood gas results may be used to determine maternal oxygenation and acid-base balance. The woman may be placed in the Fowler’s position and given oxygen as needed. Tocolytic therapy is discontinued if the woman has chest pain or shortness of breath. When corticosteroids are given, the nurse must observe for fluid retention and pulmonary edema. Indomethacin can constrict the ductus arteriosus in the fetus and reduces amniotic fluid by reducing fetal kidney function. Careful fetal monitoring is essential. Side effects of magnesium sulfate include a feeling of warmth, headache, nausea, and lethargy. Nifedipine and magnesium sulfate cannot be used together because low maternal calcium levels may occur. Progesterone therapy is under study for use as a tocolytic (ACOG, 2003).

Home Care Management

If the woman meets appropriate criteria, the primary health care provider may consider home care (see Chapter 18). There is evidence that using the home uterine activity monitor (HUAM) is effective in decreasing preterm births in a select group of women. Detecting contractions or contraction frequency before cervical changes occur makes HUAM worthwhile.

Premature Rupture of Membranes

Spontaneous rupture of the amniotic sac more than 1 hour before onset of true labor is referred to as premature rupture of membranes (PROMs). Rupture of the membranes before 37 weeks’ gestation is known as preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROMs). The exact cause is unknown, but there are several risk factors.

Infection for both the mother and the fetus is the major risk; when membranes are ruptured, microorganisms from the vagina can ascend into the amniotic sac. Compression of the umbilical cord can occur as a result of the loss of amniotic fluid. Prolapse of the cord can also occur, which results in fetal distress. Because amniotic fluid is slightly alkaline, confirmation that the vaginal fluid is amniotic fluid can be obtained by a Nitrazine paper test, which it will turn blue-green on contact with amniotic fluid (Skill 14-1). Examination of the fluid under a microscope (fern test) will also show a ferning pattern as the fluid dries.

Management

Treatment depends on the duration of gestation and whether evidence of infection or fetal or maternal compromise is present. For many women near term, PROM signifies the imminent onset of true labor. If pregnancy is at or near term and the cervix is soft and with some dilation and effacement, then augmentation of labor may be started a few hours after rupture. If the woman is not at term, the risk of infection or preterm birth is weighed against the risks of an induction by oxytocin or a cesarean birth (Nursing Care Plan 14-1 on p. 300).

Infection of the amniotic sac, called chorioamnionitis, may be caused by prematurely ruptured membranes because the barrier to the uterine cavity is broken. The risk of infection increases if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 18 hours.

Management will likely consist of bed rest with bathroom privileges and observation for infection, NST, and daily assessment for fetal compromise. Antibiotics are given to reduce infection and steroids to hasten fetal lung development (Table 14-2).

Table 14-2

Management of Women with Premature Rupture of the Membranes (PROM)

| Women with PROM | Preterm Fetus | Term Fetus |

| Bed rest Hydration Sedation Antibiotics, if needed Reassurance |

Determination of PROM Assessment for prolapsed cord Observation for infection Administration of corticosteroids, with or without delivery in 24-48 hours Delivery when the infant has the best chance for survival (i.e., avoid fetal distress) Have emergency resuscitation equipment available |

Induction of labor if spontaneous labor has not begun by approximately 12 hours after PROM Potential for cesarean birth Expectant management of maternal-fetal infection Increased chance of asphyxia and respiratory distress in newborn after birth |

The woman may remain in the hospital until birth; however, if there is no sign of infection or fetal compromise, she may return home and self-monitor. Preparation for nursing management includes:

• Documenting vital signs daily and reporting any temperature greater than 38° C (100.4° F)

• Providing sterile equipment for vaginal examinations

• Reporting uterine contractions

• Reporting any vaginal discharge or bleeding

• Having the woman remain on bed rest in a lateral position (with bathroom privileges)

• Instructing the woman to document fetal activity (daily kick counts) and report fewer than 10 kicks in a 12-hour period

• Explaining activity restrictions

• Explaining the need to abstain from sexual intercourse and orgasm

• Telling the woman to avoid breast stimulation, which can cause release of oxytocin and initiate uterine contraction

Dystocia

Dystocia, also known as dysfunctional labor, is a difficult or abnormal labor. It primarily results from one of the following problems (Table 14-3):

Powers: abnormal uterine activity (ineffective uterine contractions)

Passageway: abnormal pelvic size or shape and other conditions that interfere with descent of the presenting part (such as tumors or soft tissue resistance)

Passenger: abnormal fetal size or presentation (excessive size or less than optimum position)

Psyche: past experiences, culture, preparation, and support system

Table 14-3

Causes of Dystocia (Dysfunctional Labor)

| Cause | Examples |

| Difficulty with powers | Uterine dysfunction or abnormalities |

| Difficulty with passageway | Pelvic size and shape, tumors |

| Difficulty with passenger | Fetal abnormality Excessive size Malpresentation Malposition |

| Psyche | Maternal anxiety, fatigue |

Dystocia is suspected when the rate of cervical dilation or fetal descent is not progressing normally or uterine contractions are ineffective. A prolonged labor, with potential injury to the fetus, may result. Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) is used to assess uterine contractions and fetal well-being. Nursing assessment of the intensity, frequency, and duration of contractions is important.

Dystocia can be associated with problems such as maternal dehydration, exhaustion, increased risk of infection, and fetal distress. Change in maternal vital signs, such as elevation of temperature or rise in pulse rate, should be reported. Comfort measures should be implemented by nursing personnel, and the woman and significant other should be kept informed about the progress of labor.

Powers

Abnormal Uterine Contractions

Dysfunctional labor can result from abnormal uterine contractions that prevent normal progress of cervical dilation, effacement, and descent of the presenting part. It can be further described as being primary (hypertonic dysfunction) or secondary (hypotonic dysfunction).

Hypotonic Dysfunction

Hypotonic uterine dysfunction (secondary uterine inertia) occurs with abnormally slow progress after the labor has been established (Table 14-4). The uterine contractions become weak and inefficient and may even stop. The contractions are fewer than two or three in a 10-minute period and usually are not strong enough to cause the cervix to dilate beyond 4 cm, and the fundus does not feel firm at the height (or acme) of the contraction. Consequently, labor fails to progress. A prolonged labor can occur, which can increase the risk of intrauterine infection, placing both the mother and newborn at risk.

Table 14-4

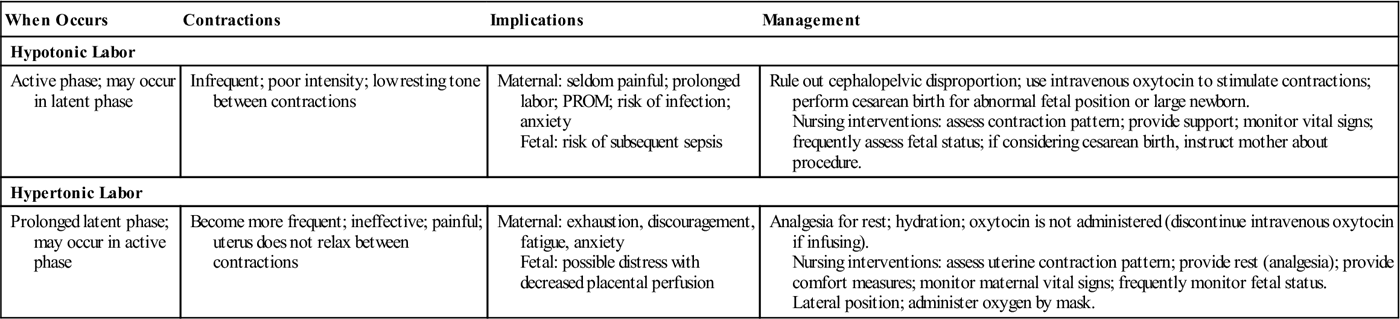

Comparison of Hypotonic and Hypertonic Labor

| When Occurs | Contractions | Implications | Management |

| Hypotonic Labor | |||

| Active phase; may occur in latent phase | Infrequent; poor intensity; low resting tone between contractions | Maternal: seldom painful; prolonged labor; PROM; risk of infection; anxiety Fetal: risk of subsequent sepsis |

Rule out cephalopelvic disproportion; use intravenous oxytocin to stimulate contractions; perform cesarean birth for abnormal fetal position or large newborn. Nursing interventions: assess contraction pattern; provide support; monitor vital signs; frequently assess fetal status; if considering cesarean birth, instruct mother about procedure. |

| Hypertonic Labor | |||

| Prolonged latent phase; may occur in active phase | Become more frequent; ineffective; painful; uterus does not relax between contractions | Maternal: exhaustion, discouragement, fatigue, anxiety Fetal: possible distress with decreased placental perfusion |

Analgesia for rest; hydration; oxytocin is not administered (discontinue intravenous oxytocin if infusing). Nursing interventions: assess uterine contraction pattern; provide rest (analgesia); provide comfort measures; monitor maternal vital signs; frequently monitor fetal status. Lateral position; administer oxygen by mask. |

Hypotonic contractions occur as a result of fetopelvic disproportion, fetal malposition, overstretching of the uterus caused by a large newborn, multifetal gestation, or excessive maternal anxiety. The woman with hypotonic contractions can become exhausted and dehydrated. Medical management includes ruling out cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) by ultrasound. If CPD is not the problem, augmentation by oxytocin is often started. The use of epidural analgesia and other regional anesthesia may reduce the effectiveness of the woman’s voluntary pushing efforts. Encouraging position changes and coaching can be helpful.

Hypertonic Uterine Dysfunction

Hypertonic uterine dysfunction refers to a labor with uterine contractions of poor quality that are painful, are out of proportion to their intensity, do not cause cervical dilation or effacement, and are usually uncoordinated and frequent (see Table 14-4). This is more common with a first pregnancy or an anxious woman who has intense pain and lack of labor progression. The latent period of labor is prolonged, which increases her exhaustion and anxiety. Often there is not adequate relaxation of muscle tone between contractions, which causes the woman to complain of constant cramps and results in ischemia or reduced blood flow to the fetus.

Management of hypertonic uterine dysfunction is rest, which is achieved by analgesia to reduce pain and encourage sleep. An intravenous infusion is frequently administered to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance. Often women awaken with normal contractions.

Passageway

Abnormal Pelvis Size or Shape

Contractures of the pelvic diameters reduce the capacity of the bony pelvis, including the inlet, midpelvis, outlet, or any combination of these planes. Pelvic contractures may be caused by congenital malformations, rickets, maternal malnutrition, tumors, and previous pelvic fractures.

Inlet contractures occur when the diagonal conjugate is shortened (less than 11.5 cm [4.5 inches]). Abnormal presentations, such as face and shoulder presentations, increase this problem. Midplane contractures are the most common cause of pelvic dystocia. Fetal descent is arrested (stops), and a cesarean birth is commonly done. Outlet contracture exists when the pubic arch is narrow. If uterine contractions continue when the passageway is obstructed, uterine rupture can occur, placing both the mother and fetus at risk. A common minor obstruction of the passageway is a distended bladder. Catheterization may be needed if the woman cannot void.

Scar tissue on the cervix from previous infections or surgery may not readily yield to labor forces to efface and dilate. A cesarean birth may be indicated when an abnormality of the passageway prolongs or impedes the progress of labor.

Passenger

Cephalopelvic Disproportion

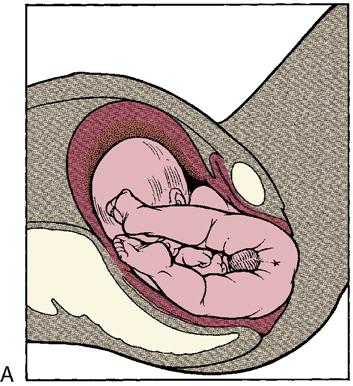

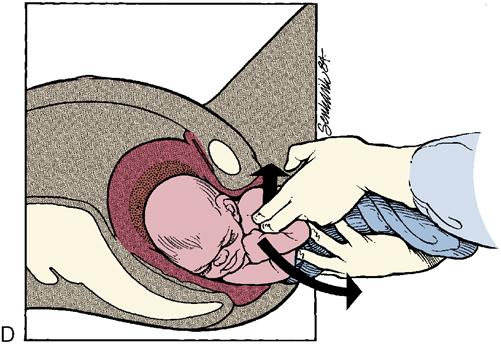

Cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) is a condition in which the presenting part of the fetus (usually the head) is too large to pass through the woman’s pelvis. Because of the disproportion, it becomes physically impossible for the fetus to be delivered vaginally, and cesarean birth is necessary. CPD is suspected when the newborn’s head does not continue to descend even though the woman is having strong uterine contractions. Excessive fetal size may be associated with diabetes mellitus, multiparity, and genetics (one or both parents of large size). A large newborn (macrosomia) can cause difficulty in birth of the shoulders (shoulder dystocia). A modified position can aid in delivery  (Figure 14-1). Maternal complications that can occur are exhaustion, hemorrhage, and infection. Birth trauma and anoxia are complications for the fetus.

(Figure 14-1). Maternal complications that can occur are exhaustion, hemorrhage, and infection. Birth trauma and anoxia are complications for the fetus.

Abnormal Fetal Presentation

A malpresentation refers to any presentation of the fetus other than the vertex presentation, in which the top of the head emerges first. Malpresentation may prolong labor and make it more uncomfortable for the woman.

Breech Presentation

Breech Presentation

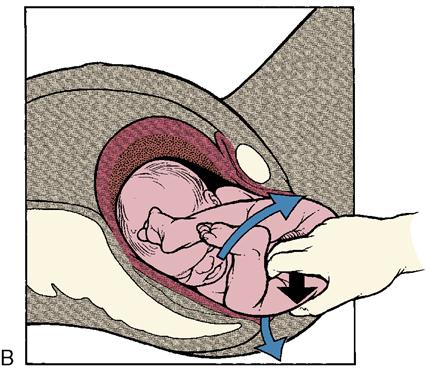

Breech presentations are often associated with preterm birth, multiple gestation, congenital anomalies, placenta previa, and multiparity. Breech is the most common example of malpresentation. It occurs in approximately 3% to 4% of all births. During labor, the fetal descent is slow because the breech is a less effective dilating wedge than the fetal head. The buttocks, legs, and feet are softer than the head and therefore exert less pressure on the cervix. Cord prolapse occurs more often during breech birth and increases the risk of birth trauma because the buttocks (presenting part) are smaller than the head and do not fit as tightly into the pelvis. The risk of postpartum hemorrhage is also increased. The three basic types of breech presentation are shown in Figure 14-2. Alternatives to vaginal birth of the fetus in breech presentation are external cephalic version (ECV) or a cesarean birth, in which the fetus is delivered abdominally. The woman should be fully informed of her options and the risks involved in each.

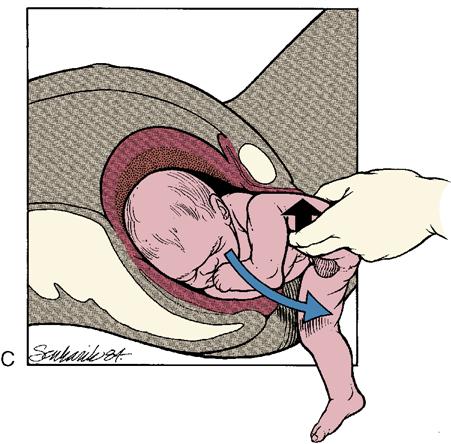

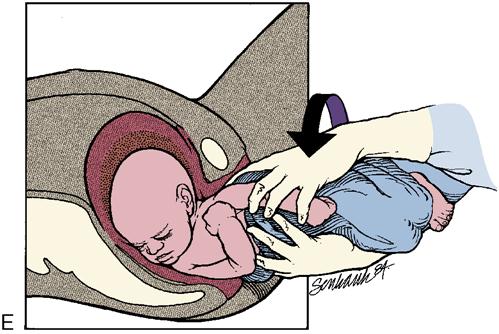

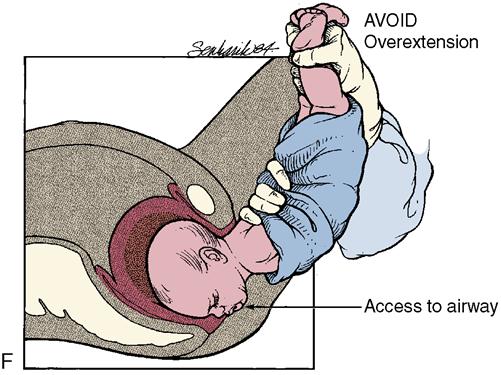

The presence of meconium in the amniotic fluid in breech presentations is not necessarily a sign of fetal distress but results from pressure on the fetal abdominal wall and buttocks. Fetal heart tones are best heard at or above the maternal umbilicus. Forceps are sometimes used to deliver the after-coming fetal head. In a breech delivery, when the lower body is born, the umbilical cord extends above the fetal head and is at risk of compression as the head passes through the bony vaginal canal. Birth of the head must occur quickly to avoid hypoxia. The mechanism of labor in a breech presentation is shown in Figure 14-3.

Face and Brow Presentation

In a face or brow presentation, the diameter of the presenting part is larger than in a vertex or occiput presentation. It is a less effective dilating wedge than the top of the fetal head. The safest means of delivery of the baby in the posterior face position is a cesarean birth. A forceps delivery may be done, but fetal hypoxia and injury are always risks.

Persistent Occiput Posterior Position

Persistent occiput posterior positions occur when the back of the fetal head (the occiput) enters the maternal pelvis and is directed toward the back (posterior) of the maternal pelvis instead of toward the front (anterior). When this position occurs, labor is usually prolonged because, in the process of internal rotation, the head must rotate further. A maternal hands-and-knees position may help the fetus rotate from a posterior to an anterior position (Figure 14-4). A squatting position helps straighten the pelvic curve and aids in rotation. Sometimes the woman is asked to push while lying on her side, which may help the fetus rotate to an anterior position. If the occiput remains posterior, the baby is born with the face upward. The woman usually has a great deal of back discomfort because the baby’s head presses against her sacrum during rotation. Sacral counter pressure and back rubs are appreciated by the woman during labor.

External Version

External version is changing the fetal presentation after 37 weeks’ gestation, usually from breech or transverse lie to cephalic presentation. Successful external version can reduce a woman’s chance of having a cesarean birth. The risks of an external version are a prolapsed umbilical cord and abruptio placentae. Contraindications are uterine malformations, previous cesarean birth, disproportion between fetal size and maternal pelvic size, placenta previa, multifetal gestation, and uteroplacental insufficiency.

Ultrasound guides fetal manipulations during the external version. Most physicians give the woman a tocolytic drug to relax the uterus. After the uterus is relaxed, the physician presses on the abdomen to gently push the breech out of the pelvis and toward the mother’s side. The fetal head is pushed downward and to the opposite side. The tocolytic drug is stopped after the version is completed. Fetal heart rate and contractions are monitored, and the woman is taught to report signs of labor that may occur.

Maternal version is usually an emergency procedure that occurs in the delivery room. Most commonly, it is performed during the vaginal birth of twins to change the fetal presentation of the second twin.

CAM Therapy

Complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies may play a role in versions. In traditional Chinese medicine, the herb mugwort is used in a therapy, called moxibustion. Incense cones of the prepared herb are placed in the outer corner of the fifth toenail (a median point of the body) and allowed to burn near the skin. The heat and odor are believed to increase fetal activity that promotes a breech version (Neri, Airola, Contu, et al., 2004). See Chapter 21 for further discussion of CAM therapies.

Psyche

Psychological factors have a strong effect on the progress of labor. The woman’s perceived fears of pain, lack of support, embarrassment, or violation of religious rituals can cause the body to respond to the stress in ways that inhibit the progress of labor. Secretions of epinephrine as a response to stress inhibit contractions and divert blood away from the uterus to the skeletal muscle. Tense muscles result in less effective uterine contractions and a higher perception of pain. Glucose used in the stress response reduces the energy supply available to the labor process. The nursing goal is to help the woman relax by adjusting the environment for maximum comfort and cleanliness, establishing a trusting relationship with the mother and family, guiding the support person, and using pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic methods of pain management.

Induction of Labor and Augmentation

Induction of labor refers to measures to initiate uterine contractions before they spontaneously begin. Labor is usually induced because the benefits of terminating the pregnancy outweigh the benefits of continuing the pregnancy for mother or fetus. Augmentation of labor is the use of an oxytocic drug after spontaneous but ineffective labor has begun. The woman and partner should be fully informed of risks and benefits of these procedures.

Reasons for Induction

Induction of labor is often performed because the delay of delivery would place the woman or fetus at significant risk. Maternal indications for induction include infection (chorioamnionitis), PROM, and worsening medical disorders (e.g., gestational hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 1, or chronic hypertension). Fetal indications include intrauterine growth restriction, postterm newborn, and fetal demise. Elective induction for convenience in planning child care, transportation, and birth attendants is a growing trend. Induction of labor is contraindicated if the mother has active genital herpes, CPD, umbilical cord prolapse, placenta previa, or vertical incision of the uterus from a previous cesarean birth.

Methods of Induction

CAM Therapy

CAM therapies (see Chapter 21) for inducing labor have become popular, and admission interviews should include asking the woman whether any practices have been used. Midwives sometimes recommend the use of evening primrose oil (which converts to a prostaglandin compound), black haw, black cohosh, blue cohosh, or red raspberry leaves to induce labor (Tournaire & Theau-Yonneau, 2007). Their value in aiding cervical ripening or enhancing safe labor induction is still under investigation. Castor oil, hot baths, and enemas are not recommended and have no proven value in labor induction. Sexual intercourse is commonly recommended to induce term labor in many cultures. The belief involves the release of oxytocin resulting from breast stimulation, the release of natural prostaglandin from the semen, and the stimulation of uterine contractions that result from female orgasm all contributing to labor induction. Acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may stimulate release of natural prostaglandins and oxytocin, but their effectiveness as labor induction techniques is not supported by research data.

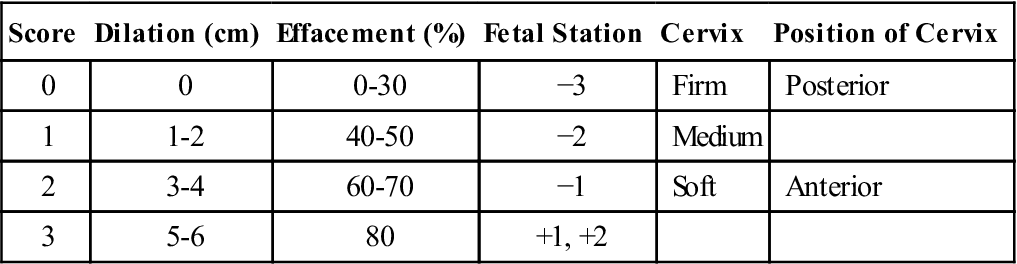

Cervical Ripening

Induction of labor will be more successful if the cervix is “ripe,” reducing the need for an emergency cesarean birth. Cervical ripening, or maturation, describes a series of biochemical events that result in a soft, pliable cervix. The cervical ripening is evaluated by the Bishop scale (Table 14-5). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has recommended that a Bishop score of 6 or more is necessary to predict a successful outcome of labor induction (ACOG, 2007). Techniques of cervical ripening include nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods.

Table 14-5

| Score | Dilation (cm) | Effacement (%) | Fetal Station | Cervix | Position of Cervix |

| 0 | 0 | 0-30 | −3 | Firm | Posterior |

| 1 | 1-2 | 40-50 | −2 | Medium | |

| 2 | 3-4 | 60-70 | −1 | Soft | Anterior |

| 3 | 5-6 | 80 | +1, +2 |

A point may be added to the score for preeclampsia and each prior vaginal delivery. A point may be deducted from the score for a postterm pregnancy, nulliparity, or prolonged ruptured membranes. A high score (8 or 9) is predictive of a successful labor induction because the cervix has ripened, or softened, in preparation for labor. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a score of 6 or above before induction of labor.

From Bishop, E.H. (1964). Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 24, 266–268. Modification by Brennand, J.E., & Calder, A.A. (1991). Labor and normal delivery: Induction of labor. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 3, 764.

Nonpharmacologic Methods

Nonpharmacologic methods of cervical ripening include:

Stripping of membranes: The digital separation of the amniotic membranes from the lower uterine segment. The cervix must be dilated enough to allow penetration to reach the membranes. Endogenous prostaglandins are released that stimulate oxytocin production.

Amniotomy: The artificial rupture of the membranes (AROM). Membranes are ruptured by piercing with an amniotic hook. The vertex must be engaged before this procedure is performed to prevent cord prolapse. The fetal heart rate should be monitored after an amniotomy, and the character, odor, and color of the amniotic fluid should be documented.

Mechanical dilators: Dilators can be inserted into the cervix to progressively dilate the cervix and release endogenous prostaglandins. This process is uncomfortable for the woman and has been replaced by hygroscopic dilators.

Hygroscopic dilators: Laminaria species, a type of desiccated seaweed; Lamicel, a synthetic dilator containing magnesium sulfate in polyvinyl alcohol; or Dilapan (polyacrylonitrile) is inserted into the cervix, absorbs fluid from surrounding tissues, and then expands to cause cervical dilation (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007). The dilator is usually left in place for 6 to 12 hours; the Bishop score is then reevaluated. Nursing responsibilities include documenting the number of dilators inserted, assessing urinary retention, and monitoring fetal heart patterns and uterine contractions.

Pharmacologic Methods

Prostaglandin (PGE2) gel is applied to the cervix before induction to soften and thin (ripen) the cervix. PGE2 gel may be administered through a catheter into the cervical canal or applied to a diaphragm that is placed next to the cervix. Oxytocin induction usually is not started for several hours to avoid uterine hyperstimulation. Side effects of PGE2, which include vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and hyperstimulation of the uterus, are not common but can occur with gel application. The woman may be placed flat or in a modified Trendelenburg position for 30 minutes to 1 hour after gel insertion to prevent leakage. Prostaglandin preparations include dinoprostone (Prepidil, Cervidil) and misoprostol (Cytotec). Misoprostol is a prostaglandin (PGE1) analog approved for use in gastric ulcers and is considered an “off label use” for cervical ripening because it is not FDA approved for this purpose. However, it continues to be used often with special guidelines but is contraindicated for use in women who have had a previous cesarean section due to high risk of uterine hyperstimulation (ACOG, 2006). Uterine contractions and fetal heart rate are monitored for at least 30 minutes after insertion. Women who have asthma, glaucoma, or renal or liver disease may not be candidates for this treatment. Cervical ripening procedures usually reduce the dose of oxytocin needed for induction of labor. Use of these preparations should be in a setting where facilities for emergency cesarean section are immediately available (ACOG, 2007).

Oxytocin Induction and Augmentation

Oxytocin, a hormone normally produced by the posterior pituitary gland, stimulates uterine contractions. Oxytocin (Pitocin) is used to induce the labor process or to augment labor that is progressing slowly because of ineffective uterine contractions.

Before oxytocin administration is started, a vaginal examination is performed to assess cervical dilation and effacement, fetal presentation and position, and fetal descent. The woman’s vital signs are assessed and recorded, and fetal well-being is evaluated. Continuous EFM is started before and is continued during the oxytocin infusion.

Oxytocin has an antidiuretic effect that can decrease urinary output and cause water retention. Maternal water intoxication and fetal hyperbilirubinemia have been associated with prolonged oxytocin infusions. The nurse should be alert for signs of water intoxication, including headache, nausea and vomiting, decreased urinary output, hypertension, tachycardia, and cardiac dysrhythmias. The most common adverse effects of oxytocin administration are uterine hyperstimulation and reduced fetal oxygenation. Hyperstimulation may lead to uteroplacental insufficiency, fetal compromise, uterine rupture, and a very rapid labor with potential uterine or cervical lacerations.

Oxytocin (diluted in an intravenous solution) is administered by a controlled infusion pump. During the oxytocin intravenous infusion, the nurse should report any contractions lasting longer than 90 seconds, intervals between contractions less than 60 seconds, and nonreassuring fetal heart rates. Oxytocin should not be administered without a physician readily available who is capable of performing an emergency cesarean birth. The nursing goals include assessing uterine activity, cervical dilation, and maternal-fetal response. The nurse assesses intake and output to prevent water intoxication. Oxytocin is discontinued immediately and the primary health care provider notified if uterine hyperstimulation or nonreassuring fetal heart rate occurs.

The health care provider explains the procedure to the woman and advises her that frequent evaluations will be necessary. Nursing care includes frequent perineal cleansing and linen changes to reduce the introduction of organisms and thus decrease the risk of infection and promote comfort. The side-lying position is recommended to increase placental perfusion. The woman’s vital signs should be taken and the external fetal monitor evaluated frequently.

Nipple stimulation may be used to aid stimulation of labor (Chapter 5). Terbutaline should be available to stop labor induction if hyperstimulation of the uterus or adverse fetal responses occur. Oxygen is administered by mask during induction, and the woman is closely monitored. Failure to dilate more than 2 cm in a 4-hour period during active labor may be an indication for cesarean birth.

Episiotomy

Although episiotomies are used when indicated, every effort is made to retain an intact perineum and reduce perineal trauma. An episiotomy is a surgical incision made into the perineum to permit easier passage of the fetus. It is indicated when lacerations of the perineum, vagina, or cervix might occur. It is performed to shorten the second stage of labor, relieve compression on the fetal head, and facilitate breech and forceps births. Episiotomy is not routinely performed but should not be routinely avoided. Two types of episiotomies are (1) the median (midline) episiotomy, which extends from the posterior fourchette of the vagina downward but not to the rectal sphincter; and (2) the mediolateral episiotomy, which is an incision made on an angle to the woman’s right or left side (Figure 14-5). An episiotomy is thought to heal more satisfactorily than a laceration. A median episiotomy is considered to be less uncomfortable and heals better than a mediolateral incision. However, a median incision can extend into the rectum. A regional or local block is given before the episiotomy is performed. Ideally, the episiotomy is performed when the fetal head is crowning, just before the birth of the fetus, to reduce the blood loss.

If lacerations of the perineum occur, they are classified in one of four degrees: A first-degree laceration extends through the skin and into the mucous membrane. A second-degree laceration extends farther, reaching the muscles of the perineal body. In a third-degree laceration, the anal sphincter muscles and muscles of the perineum are torn. A fourth-degree laceration reaches into the anal sphincter muscles and anterior wall of the rectum.

Measures used (especially by midwives) to enhance perineal stretching are the application of warm compresses, warm oil, and perineal massage. The warm compresses and perineal massage are thought to soften and stretch perineal muscles and may reduce the need for an episiotomy.

Often, after episiotomy repair, an ice bag is applied to the incision to reduce swelling. Other nursing measures used for an episiotomy are discussed in Chapter 12. Kegel exercises are encouraged after healing to regain muscle tone (see Chapter 12).

Assisted Vaginal Delivery

Forceps-Assisted Birth

Forceps are curved metal instruments used by the physician to provide traction to deliver the baby’s head, assist the rotation of the head, or both (Figure 14-6). These instruments may be used to deliver preterm newborns to prevent undue pressure from being placed on the fragile fetal skull by continued contractions. They are also used to shorten the second stage of labor when the mother is exhausted and cannot effectively bear down. Sometimes regional or general anesthesia has affected the motor innervation and the mother cannot push effectively. Forceps are also used to assist the descent of the baby as soon as possible when fetal distress occurs. The cervix must be completely dilated and the fetus’s head low or visible on the perineum (low forceps delivery) (Box 14-1). Forceps should be applied by a skilled physician only. A Foley catheter is inserted before forceps delivery to prevent bladder injury. The obstetric forceps has a cephalic curve to fit over the fetal head and conforms to the curve of the maternal pelvis. Piper forceps are used for the head in a breech delivery after the body is born. Forceps delivery is no longer in popular use, being replaced by vacuum extraction and elective cesarean section.

Maternal complications of a forceps delivery include lacerations of the birth canal and perineum with increased blood loss. The newborn can have bruising and edema of the scalp, potential cephalhematoma, and intracranial hemorrhage. In a difficult forceps application, temporary or even permanent paralysis of a facial nerve may occur.

The nurse explains the procedure to the woman and helps the woman use breathing techniques to avoid pushing during application of forceps. The health care provider applies traction during a contraction as the woman pushes. After birth, the newborn is assessed for bruising, edema, and other trauma. Bruising and edema in the newborn, called forceps marks, resolve without treatment (Figure 14-7). The mother is observed for bleeding, which will be a brighter red than lochia rubra. Cold application to the perineum for the first 12 hours reduces edema and lessens pain. Heat compresses after 12 hours aid in the absorption of edema and hematoma.

Vacuum Extraction

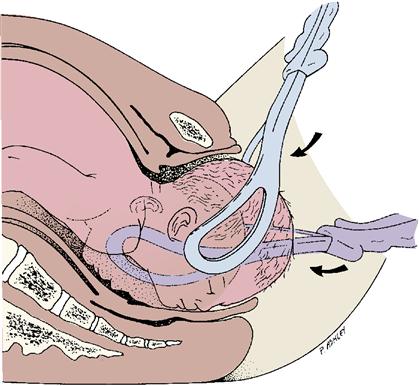

Vacuum extraction is used as an alternative to forceps application. Vacuum extraction involves applying a cup, called a vacuum extractor, to the fetal head and withdrawing air from the cup. This creates a vacuum within the cup, which secures it to the fetal head. Traction applied during the uterine contractions assists with the descent of the fetus, and the fetal head is delivered (Figure 14-8). The indications for vacuum extraction are the same as for forceps deliveries.

Side effects of vacuum extraction include edema and bruising to the fetal scalp. Risks to the fetus include cephalhematomas, scalp lacerations, and subdural hematoma. Maternal complications are uncommon. The woman should be informed about the medical procedure. The fetal heart rate should be monitored. Parents need to be advised that the caput chignon (edema of the fetal scalp) will disappear in approximately 2 or 3 days. Assessment of the newborn includes continued observation for cerebral hemorrhage and injury.

Postterm Labor and Birth

Postterm Labor and Birth

Postterm birth is the birth of a newborn beyond 42 weeks’ gestation. The primary maternal risk related to postterm birth is a large newborn, which places the woman at risk for a dysfunctional labor, forceps-assisted birth, lacerations in the vaginal canal, and a potential cesarean delivery. Fetal risks include the possibility of birth trauma, CPD, and hypoxia caused by an aging placenta that begins to deteriorate after 42 weeks’ gestation. When placental insufficiency is present, the risk of fetal hypoxia increases.

The management of postterm labor is controversial. Induction of labor is suggested at 42 weeks’ gestation. Tests for fetal well-being are performed, including an NST and biophysical profile with ultrasound scanning to assess fetal movements, fetal breathing, and amniotic fluid volume. Amniocentesis may be performed to detect meconium in the amniotic fluid (see Chapter 5). A postmature newborn has a long lean body, long fingernails, and dry, peeling skin (see Chapter 15).

Precipitate Labor

Precipitate labor is a labor completed in less than 3 hours from the time of the first true labor contraction to the birth of the baby. Because the labor is rapid, maternal and fetal complications can occur. If the uterus has little relaxation between contractions, the intervillous blood flow may be impaired enough to cause fetal hypoxia (lack of oxygen). Also, rapid passage of the fetal head through the birth canal may result in fetal intracranial hemorrhage. The woman may also have cervical, vaginal, or perineal lacerations. Ideally, a physician will be available in the facility to assess the woman and newborn and record the findings. The emergency delivery of the newborn by a nurse is discussed in Chapter 7.

Uterine Rupture

Uterine rupture is rare; however, it represents an emergency condition because it causes severe maternal bleeding and shock. It occurs most often during labor and delivery. When uterine rupture is associated with a previous cesarean birth, the rupture occurs at the site of the previous surgical scar. Aggressive or poorly supervised induction of labor may be responsible for a rupture of the uterus. A prolonged labor with fetopelvic disproportion is another cause.

A clue to a pending rupture is persistent uterine contractions without periods of relaxation. The nurse must report uterine contractions lasting more than 90 seconds. A relaxation period is necessary to maintain fetal oxygenation. Careful EFM monitoring can identify women at risk for rupture. As labor progresses, the woman might have a sharp pain in the suprapubic area. With severe bleeding, symptoms of shock occur. The major complications are maternal hemorrhage and fetal death. Treatment usually consists of an immediate uterine surgery and possible hysterectomy. Blood transfusions may be needed.

Hydramnios

Hydramnios (also called polyhydramnios) is an excessive amount of amniotic fluid, greater than 2 L. When hydramnios is present, congenital anomalies often exist, particularly those of the fetal gastrointestinal tract. It is associated with fetal malformations that affect fetal swallowing and voiding. During pregnancy, the fetus voids in and swallows the amniotic fluid. Any fetal anomaly that upsets this exchange can result in an excessive amount of amniotic fluid. When hydramnios develops, the uterus overdistends. This may cause preterm labor and place the woman at a greater risk for postpartum hemorrhage. Hydramnios can be diagnosed by ultrasound (an amniotic fluid index [AFI] greater than 20) (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007). Removal of excess amniotic fluid may cause abruptio placentae, as the uterine size is decreased, or the prolapse of the umbilical cord. Psychological support for the mother is an important nursing responsibility. Amniocentesis may be done to avoid a preterm labor caused by an overdistended uterus.

Oligohydramnios

Oligohydramnios is a decreased amount of amniotic fluid (an AFI less than 5) (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007). It is associated with fetal renal anomalies and intrauterine growth restriction. Oligohydramnios places the fetus at risk for impaired musculoskeletal development because of the inability to move freely in the uterus and tangling of the long cord around an extremity, or cord compression from twisting or kinking, resulting in fetal distress. Oligohydramnios can be detected by ultrasound, which detects less than 1 cm of fluid in a predetermined pocket or quadrant of the uterus (AFI). During labor, an amnioinfusion (a transcervical instillation of warm sterile saline or lactated Ringer’s solution into the uterus) may be done if membranes have ruptured to prevent cord compression and relieve the severity of variable decelerations. Fetal monitoring and maintaining a clean, dry bed for the mother are important nursing responsibilities.

Prolapsed Umbilical Cord

Prolapsed Umbilical Cord

Prolapsed umbilical cord occurs when the umbilical cord precedes the fetal presenting part. This condition is more likely to occur when there is a loose fit between the fetal presenting part and the maternal pelvis when the membranes have ruptured. This circumstance leaves room for the cord to slip down (prolapse) (Figure 14-9). The cord can be alongside or ahead of the presenting part. It may be occult (not palpable on vaginal examination), be inside the vagina, or even extend below the vulva. Because compression of the cord between the presenting part and the bony pelvis greatly decreases the flow of oxygen to the fetus, prolapse of the cord can interfere with fetal oxygenation.

Factors that contribute to cord prolapse are (1) rupture of membranes before the fetal head is engaged, carrying a loop of the umbilical cord into the pelvis or vagina; (2) a small fetus; (3) breech presentation; (4) transverse lie; (5) hydramnios; (6) an unusually long cord; and (7) multifetal pregnancy. Signs include prolonged variable decelerations evidenced on the fetal monitor, along with a baseline fetal bradycardia.

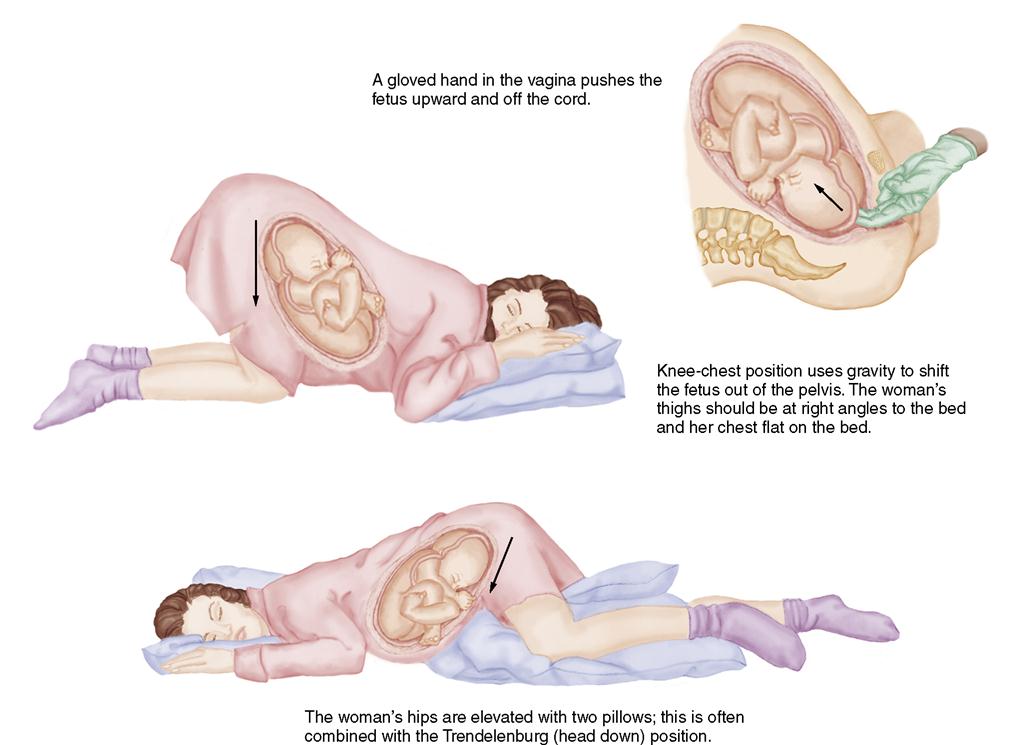

Prompt actions must be taken to relieve cord compression and increase fetal oxygenation until help arrives. Nursing interventions include:

• Placing the woman’s hips higher than her head by (1) knee-chest position (Figure 14-10), (2) Trendelenburg position, or (3) side-lying position with hips elevated on pillows

• With sterile gloved hand, pushing fetal presenting part away from the cord

• Starting oxygen 8 to 10 L/minute by mask

If the cord protrudes, the nurse should apply sterile saline-soaked towels to prevent drying of the cord and to maintain blood flow until the infant is delivered.

Amnioinfusion

Amnioinfusion is a procedure during which normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution is instilled into the amniotic cavity through a catheter introduced transcervically into the uterus during labor. It is performed to correct oligohydramnios or reduce thickly stained meconium in the amniotic fluid and to minimize cord compression. An infusion pump should be used so that flow rate is controlled and the amount of infused fluid can be accurately documented. The uterus should be monitored for overdistention and elevated resting tone, which can cause changes in the fetal heart rate. Because the fluid infused will constantly leak out, nursing measures to maintain comfort and dryness should be used. Amnioinfusions with hypertonic solutions are used as a technique of inducing abortions before 20 weeks’ gestation (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007).

Multifetal Pregnancy

Multifetal pregnancy is the term for two or more fetuses in utero. Types of multifetal pregnancies are discussed in Chapter 3. A positive diagnosis of more than one fetus is made by ultrasound. Preterm labor is common because of an overdistention of the uterus. There is an increased frequency of anemia, hypertension, and hemorrhage. The woman is more likely to hemorrhage because of an overdistention of the uterus; therefore, a multifetal pregnancy poses greater risk than a single fetus.

Twins may be in various positions; one may be breech and the other vertex. The labor may be normal or prolonged. During the birth, the nurse should be prepared to identify each baby at the time it is born. A cesarean birth may be necessary if the cord has prolapsed, if one baby is malpresenting, or if more than two fetuses are present. The nursing care of the woman after the babies are born is the same as for other women, except the nurse is aware of the greater risk for postpartum hemorrhage.

The incidence of multifetal pregnancies has increased because of the popularity of fertility treatments (assisted reproductive technology [ART]) such as in vitro fertilization. Some complications can occur with multifetal pregnancies such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, in which one twin transfuses its blood through a shunt to the other twin. This results in one twin with intrauterine growth restriction and anemia, whereas the other twin can be larger or have heart failure because of circulatory overload. Another complication involves the death of one twin in utero while the other twin survives. Reabsorption of the tissues of the dead twin can predispose the mother to develop disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007).

Multifetal pregnancy reduction may be necessary when ART results in four or more fetuses, and the survival of all is at risk unless some are selectively aborted. The remaining twins or triplets have a good chance of survival (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007). Vaginal delivery is advocated for vertex presentation of a twin, but a cesarean is indicated if presentation is not vertex or more than two fetuses are present.

Cesarean Birth

Cesarean Birth

Cesarean birth is a surgical procedure in which the birth is accomplished through an abdominal and uterine incision. The basic purpose of a cesarean birth is to preserve the life or health of the mother and her fetus. The incidence of cesarean births has increased dramatically in the past several years. In 2007, one third (32%) of all births in the United States were cesarean sections (Menacker & Hamilton, 2010), and vaginal birth after a cesarean birth (VBAC) was at an all-time low of 16.5%. Some reasons cited for the increase include the increased detection of fetal problems from the use of EFM, an increase in the number of pregnancies at an older age, and the high incidence of repeat cesarean births. Complication rates of newborns were higher with cesarean delivery than with VBAC (Kamath, Todd, Glazner, et al., 2009). A national goal of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce the rate of cesarean births to 15%. ACOG recommends VBAC in a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) with facilities available for cesarean if needed (ACOG, 2010). The risks and benefits of TOLAC as compared to a repeat cesarean section should be discussed and decisions made on an individual basis.

Cesarean birth is a surgical procedure in which the birth is accomplished through an abdominal and uterine incision. The basic purpose of a cesarean birth is to preserve the life or health of the mother and her fetus. The incidence of cesarean births has increased dramatically in the past several years. In 2007, one third (32%) of all births in the United States were cesarean sections (Menacker & Hamilton, 2010), and vaginal birth after a cesarean birth (VBAC) was at an all-time low of 16.5%. Some reasons cited for the increase include the increased detection of fetal problems from the use of EFM, an increase in the number of pregnancies at an older age, and the high incidence of repeat cesarean births. Complication rates of newborns were higher with cesarean delivery than with VBAC (Kamath, Todd, Glazner, et al., 2009). A national goal of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce the rate of cesarean births to 15%. ACOG recommends VBAC in a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) with facilities available for cesarean if needed (ACOG, 2010). The risks and benefits of TOLAC as compared to a repeat cesarean section should be discussed and decisions made on an individual basis.

Cesarean Birth on Demand

Part of the increase in the rate of cesarean birth is thought to be due to maternal request for cesarean delivery rather than medical indication for delivery (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2006). The NIH states that elective cesarean births are not recommended for women who desire several children because the risk of placenta previa or placenta accreta rises with each successive pregnancy after a cesarean birth. Placenta previa may result because the placenta generally cannot attach at the site of a scar and so may attach in a lower segment of the uterus (see Chapter 13). If the placenta does attach at the scar site, it may not release from the site after delivery, resulting in placenta accreta. A goal of Healthy People 2020 is to reduce cesarean birth on demand and increase normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries that have fewer complications for both mother and infant.

Indications

Four categories are responsible for 75% to 90% indications for cesarean births: dystocia, repeat cesarean, breech, and fetal distress. Other indications for a cesarean birth are active herpes viral infection; prolapsed umbilical cord; medical complications, such as gestational hypertension; placental abnormalities, such as placenta previa and abruptio placentae; and cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) or fetal anomalies, such as hydrocephaly (Box 14-2).

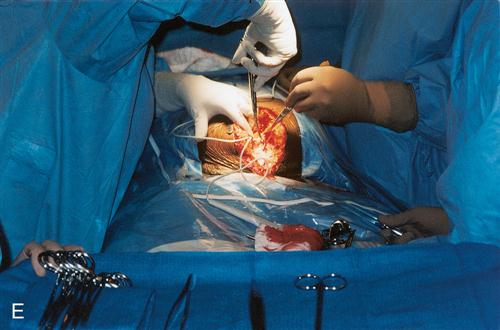

Surgical Techniques

The skin incisions for a cesarean birth are either transverse (Pfannenstiel’s) or vertical; these are not indicative of the type of incision made into the uterus. The transverse incision is made across the lowest part of the abdomen. Because the incision is made just below the pubic hair line, it becomes almost invisible after healing. The major limitation of this incision is that it does not allow extension of the incision if needed. The vertical incision is made between the navel and the symphysis pubis. This type of an incision is quicker and is preferred in cases of fetal distress. Uterine incisions are either in the lower segment or in the upper segment of the uterus. The choice of incision affects the woman’s opportunity for a subsequent vaginal birth and her risks of a ruptured scar with a subsequent pregnancy. An incision in the body (classic, or upper part) of the uterus is problematic because of potential rupture during a future labor; therefore, a future vaginal birth would be contraindicated. The lower uterine segment incision most commonly used is a transverse incision, although a low vertical incision may be used (Figure 14-11).

Complications and Risks

Cesarean births are not without risks for both mother and fetus. Maternal complications include aspiration, pulmonary embolism, hemorrhage, urinary tract infection, injuries to the bladder or bowel, wound infections, thrombophlebitis, and complications related to anesthesia. Risks to the fetus include preterm birth (if gestational age was not assessed properly), fetal injuries, and respiratory problems resulting from delayed absorption of lung fluids.

Preparation for Cesarean Birth

Because cesarean birth is common, this method should be an integral part of childbirth education classes. Couples need to discuss their specific needs and desires with their physician or nurse-midwife.

Women and their partners have time for psychological preparation when they know that they are going to have a cesarean birth. These women appear to cope with the recovery from surgery better than those who have an unplanned cesarean birth. Women having emergency or unplanned cesarean births have abrupt changes in the expectations for birth, post-birth care, and the care of the newborn at home. The woman may approach surgery exhausted and discouraged with her labor. Time for explanations about the procedures for the surgery is often limited. Because procedures for the surgery must be performed quickly, both the woman and her family may have high anxiety levels. These women need adequate psychological support. It is important to explain what is being done and for the nurse to verify that informed consent was obtained.

Nursing Care

Preoperative Care

The preoperative nursing care includes all of the usual procedures for preparing a patient for surgery. The woman receives nothing by mouth to reduce the risk of aspiration. An intravenous infusion through a wide-bore catheter is started. The hair on the skin of the abdomen is considered sterile (Gabbe, Niebyl, & Simpson, 2007). Removal (clipping or shaving) of abdominal hair is only indicated when the hair will interfere with closing and suturing the wound. Routine skin shaving has been shown to predispose the woman to postoperative wound infection. An indwelling Foley catheter is inserted to keep the bladder empty during surgery, which reduces the risk of injury to the bladder when the incisions are made. An antacid is administered intravenously to decrease stomach acids, which could cause pneumonia if the woman should vomit and aspirate during surgery. Laboratory reports are reviewed, including blood type and cross-match, Rh, complete blood cell count, and urinalysis. Although property and valuables are secured, often the mother wears her eyeglasses to the operating room because she will be awake, and seeing clearly will aid in bonding with her infant (Figure 14-12).

The fetal heart rate is recorded with electronic monitoring until the infant is delivered. Routine preoperative teaching, including coughing, deep breathing, and ambulating postoperatively, is done if time permits (Box 14-3). The use of spinal anesthesia reduces the need for vigorous newborn resuscitation that might be necessary with general anesthesia, which crosses the placental barrier. An infant warmer and resuscitation equipment should be on hand and the pediatrician notified. Preparing the woman for postoperative care expectations is a nursing responsibility. The positive aspects of a cesarean birth should be emphasized and family support offered.

Newborn Care

A nurse from the newborn nursery and a pediatrician are typically present in the operating room to assist in the care of the newborn when delivered. A heated crib and resuscitation equipment are readily available. In most hospitals, the father or partner can be with the mother during the cesarean birth.

After the baby is born, the Apgar score and identification are recorded, the newborn is moved to a radiant warmer to prevent chilling, and the skin temperature probe is applied. The mother and partner are given an opportunity to see, touch, and, depending on the condition of the newborn, hold the newborn.

Postoperative Care

After surgery, the woman is taken to the recovery room. Recovery room care includes observing the firmness of the uterus and the amount of bleeding from the vagina and assessing the abdominal incision. Vital signs are taken every 15 minutes for 1 to 2 hours or until the woman is stable. In addition, the woman receives the usual postoperative care. The woman is given oxytocin intravenously to stimulate the uterus to contract and reduce the blood loss. She is given analgesic medications to promote comfort.

The newborn is brought to the parents as soon as possible to facilitate bonding and attachment. Breastfeeding can be initiated. The woman may be transferred to the postpartum unit after 1 to 2 hours or when her condition is stable. Providing emotional support to the mother and partner after a cesarean birth is essential. Feelings of anxiety, guilt, and inadequacy may prevail. Therapeutic communication helps clear up fears and misunderstandings, and the woman should be encouraged to verbalize her fears and express her anxieties. Special effort to reduce postoperative pain and promote bonding with the newborn is important.

Early ambulation is encouraged to reduce respiratory and circulatory complications. As a rule, the woman with a cesarean birth has less lochial flow, most likely because of the removal of some of the uterine decidua during the surgical procedure. The intravenous infusion may be maintained until the woman is afebrile, has resumption of bowel sounds, and is tolerating fluids. The intravenous infusion often contains oxytocin to keep the uterus well contracted. The indwelling urinary catheter is normally maintained until the intravenous fluids are discontinued. Wound dressings may be removed after the first day.

Analgesic measures for pain at the incision site may be given every 3 to 4 hours, or patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) or epidural narcotics may be prescribed by the physician. Other comfort measures, such as position change and splinting the incision with pillows, are demonstrated. Deep breathing and coughing at frequent intervals are encouraged.

Discharge teaching includes information about wound care, personal hygiene, breast care if breastfeeding, bathing, diet, exercise and activity restrictions, sexual activity, contraception, medications, signs of complications, and newborn care. The Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act of 1996 ensures a minimum hospital stay of 96 hours for cesarean births. Aftercare can be enhanced by referral to home care resources. The nurse assesses the need for continued support or counseling and provides a telephone number to call the hospital if needed.

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean

A trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) and a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) are recommended by the ACOG for women who have had a previous cesarean birth by low transverse incision (ACOG, 2010). Labor and vaginal birth is not recommended if a previous fundal scar (classic cesarean incision) or evidence of CPD is present. Consent for VBAC should be discussed with the health care provider and the couple based on accepted risk factors. Dystocia, increased maternal age, gestational age over 40 weeks, maternal obesity, preeclampsia and macrosomia may be contraindications for TOLAC.

The labor should occur in a health care facility that is equipped and staffed to conduct a cesarean birth if necessary. Intrapartum care of the woman is essentially the same as for any woman in labor. Close observation of fetal status and uterine contractions is maintained throughout the labor process. The use of cervical ripening with misoprostol (Cytotec) is not recommended, but augmentation with oxytocin can be done with close monitoring. The 2020 ACOG guidelines for VBAC include:

• Previous cesarean birth with transverse uterine incision or low vertical scar

• Documented adequacy of the pelvis

• Availability of the facilities to perform a cesarean birth within 30 minutes

Women who have spontaneous labor have a much lower incidence of uterine rupture than women who undergo labor induction. Women who have successful VBACs have lower incidence of infection, less blood loss, and reduced health care costs compared with women who have repeat cesareans.

Skill 14-1

Skill 14-1

Nursing Care Plan 14-1

Nursing Care Plan 14-1

Go to your Study Guide on

Go to your Study Guide on  Online Resources

Online Resources