Evidence-Based Practice

1. Differentiate between research utilization and evidence-based practice.

2. Review the nurse’s role in the implementation of evidence-based practice.

3. Identify the hierarchy of evidence.

4. Discuss the critical appraisal process in evaluating evidence.

Effects of an intervention are examined by comparing the treatment group with the nontreatment group; patients are placed in treatment or nontreatment group through random sampling

Same as a randomized clinical trial but patient placement in treatment or nontreatment group depends on study variables, with not every individual having an opportunity for selection

MEDICAL MYTHS AND TRUTHS

Two sentinel publications by the Institute of Medicine—To Err Is Human and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2000; IOM, 2001)—drew attention to quality issues in U.S. health care (see Chapter 10). A major theme of both reports was that although the technology of health care had advanced at lightning speed, the delivery system had not advanced, causing potentially lethal situations in health care. One of the most common situations seen was the increased rate of hospital-acquired infections, and one of the proposed solutions to the improvement of care was the use of evidence-based decision making in health care.

Evidence-based practice requires a shift from the traditional paradigm of clinical practice grounded in pathophysiology and clinical experience to one of the integration of best practice and scientific evidence. This paradigm shift allows for the continuous improvement of practice and a creation of environments that stimulate innovation.

As a new nurse, there will be many times that you ask yourself, “Why do we do it this way?” Or “There must be a better way to do this.” For answers to these questions, you must look to the evidence. What does the evidence tell you? What is the best practice, or what is the best way to do this? Some of our standard practices are “sacred cows,” meaning they represent “the way it has always been done.” For instance, does every patient admitted to your unit need their temperature taken at 7 am? Perhaps not, but that is just the “way that we do it” or perhaps that was the “best practice” when the policy was implemented. But what does the evidence (scientific data) tell us today? As nurses, it is important that you remain current within your practice area, because the evidence is always changing and growing. Estabrooks (1998) and Pravikoff et al. (2005) found that knowledge sources most frequently used by nurses were school experiences and colleague experience. Assuming that this is the case, a nurse with 15 years of experience may be using “evidence” that is 15 years out of date, and this experienced nurse who is mentoring new nurses may be fostering practice in the new nurse that is 15 years out of date. A colleague of this author once said that “health care was a long history of tradition unimpeded by progress”—the move to evidence-based practice is changing this.

EXAMPLES OF SOME MEDICAL MYTHS

Myth: Patients with musculoskeletal back pain respond best to bed rest followed by a specialized back exercise program (myths from Flaherty, 2007).

• Bed rest is not an effective treatment for acute low back pain and may delay recovery. Current advice is to stay active and to continue ordinary activities, which results in a faster return to work, less chronic disability, and fewer recurrent problems (Waddell, 1997).

• Among patients with acute low back pain, continuing ordinary activities within the limits permitted by the pain leads to more rapid recovery than either bed rest or back-mobilizing exercises (Malmivaara, 1995).

Myth: “Figure-of-eight” dressings or similar appliances are the preferred treatment for clavicle fractures.

• No statistical difference was found in the speed of recovery when clavicle fractures were treated by either a figure-of-eight bandage or a broad arm sling (Stanley & Norris, 1988).

• Treatment with a simple sling caused less discomfort and perhaps fewer complications than with the figure-of-eight bandage. The functional and cosmetic results of the two methods of treatment were identical and alignment of the healed fractures was unchanged from the initial displacement (Andersen et al., 1987).

Myth: Bed rest is a useful adjunctive therapy.

Truth: A meta-analysis of 39 studies of the use of bed rest versus early mobilization for prevention and treatment of a variety of medical conditions showed bed rest to be at best not beneficial and at worst harmful (Allen, 1999).

Myth: Rectal temperature can be accurately estimated by adding 1° C to the temperature measured at the axilla.

Truth: In children and young adults, temperature measured at the axilla does not agree sufficiently with temperature measured at the rectum to be relied on in clinical situations where accurate measurement is important (Craig, 2000).

DECISION-MAKING MODEL

Evidence-based practice is a decision-making model based on the “conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best practice in making decisions about the care of individual or groups of patients” (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). “This practice requires the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research, available resources, and our patient’s unique values and circumstances” (Sackett et al., 1996). This definition requires nurses to carefully and thoroughly integrate evidence into their practice. But how do they do this?

This new paradigm of evidence-based practice requires the development of a clinical inquiry approach. Nurses must ask themselves the following questions and not blindly accept standard practice (Salmon, 2007):

RESEARCH UTILIZATION

Evidence-based practice differs from research utilization. Research utilization is the process of using research-generated knowledge to make an impact on or a change in existing practices (Burns and Grove, 2007). Evidence-based practice requires synthesizing research study findings to determine best research evidence. Research evidence is a synthesis of high-quality, relevant studies to form a body of empirical knowledge for the selected area of practice. The best research evidence is then integrated with clinical expertise and patient values and needs to deliver quality, cost-effective care (Sackett et al., 2000).

QUESTION FORMULATION

The first thing that you will need to do is to formulate the question. As nurses, we make numerous decisions when caring for our patients. As we make these decisions, we are influenced by a number of factors (Craig & Smyth, 2002):

Up-to-date, valid evidence needs to be integrated with these factors to maximize the likelihood of what we want to happen (the outcome). The more explicit the question, the easier it is to run searches through the multiple electronic databases available to nurses (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library). For example, you are interested in determining best practice for change-of-shift reports. If you enter “end-of-shift report” into the search line, you will receive 56 references. If you narrow the search to within the past 5 years, the number of references is cut to 32. A focused question makes your “search strategy” much easier. It is very helpful for any nurse working in a hospital to develop a good relationship with the hospital librarian; he or she will assist you in the gathering of research evidence.

RELIABLE EVIDENCE

Once you have focused your question, you need to select the best evidence. Just because something has been published, albeit in print or on the Internet, does not mean that it is a valid source of evidence. You must first determine the reliability of the source. Your librarian will assist you in this. A research study on urinary catheters funded by the company that makes urinary catheters may not be the most reliable source of evidence; a study supporting their catheter is in the company’s best interest. The first question in your critical appraisal of the evidence is whether this study is good enough to use the findings. You will be attempting to determine if the quality of the study that you are reading is good enough for you to use the results in the design of a nursing protocol. You would need to look at the research design, the sample, and the sample size. Obviously, results from a study directed at children may not be appropriate in the design of a protocol addressed at adults. Also, a study with a sample size of 4 will not carry as much strength as will a study with a sample size of 1000. Some research designs are more powerful than others. The fact that some studies are more powerful than others has given rise to the hierarchy of evidence (Peto, 1993). The hierarchy of evidence for questions about effectiveness of an intervention follows (Polit & Beck, 2008, p. 31):

CRITICAL APPRAISAL

The next question to ask in your critical appraisal is whether the findings are applicable to your setting. The patients used in a study will never be identical to yours but there may be similarities. The following questions can be asked to determine applicability of the study to your practice area:

• Is it clear what the study is about?

• Is the sample/context adequately described?

• Are my patients/contexts so different that the results will not apply?

• Is the intervention available, or is the change possible in my setting?

• Do the benefits of the change for my patient/context outweigh the costs?

• Are the patients’ values and preferences satisfied by change?

Part of this question will be to ask what these results mean for your patients.

POPULATION, INTERVENTION, COMPARISON INTERVENTION, OUTCOME (PICO)

A framework for formulating evidence-based questions is PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison Intervention, Outcome). Box 4-1 describes the focus of the PICO question.

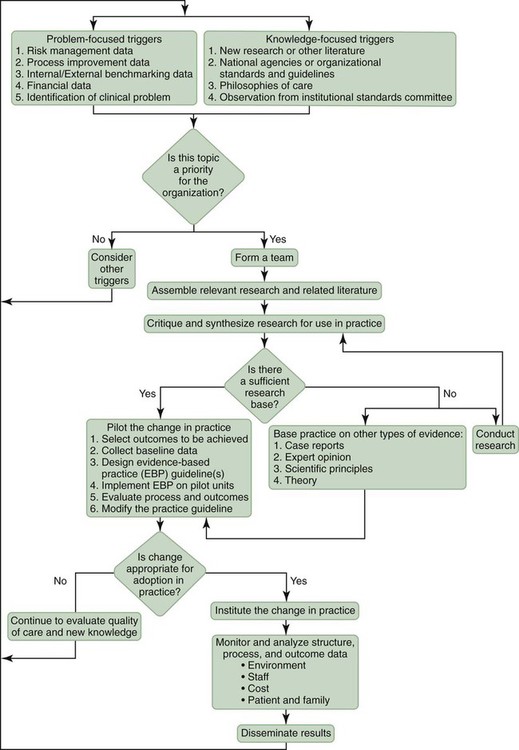

In health care organizations, there may be many triggers that initiate the need for change. They can be data driven, resulting from performance review data, risk management data, benchmarking data, and financial data. Or they can be knowledge driven, resulting from new research findings, change in regulatory guidelines and standards, or questions from practitioners.

As a nurse manager, your role will be in the promotion and implementation of evidence-based practice in your organization. The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice provides direction for the development of evidence-based practice in a clinical facility (Figure 4-1).

This model of evidence-based practice can be used as a guide for implementing a research-based protocol. The steps in this model are to:

SUMMARY

As a new nurse entering the profession, it is imperative that you maintain currency within your profession. Here are some strategies for using research evidence in your own practice:

• Read widely and critically—professionally accountable nurses keep abreast of their practice by reading journals relating to their practice.

• Join a professional organization related to your specialty—many innovations in practice and best practices are shared through professional organizations.

• Attend professional conferences and continuing education seminars.