Assessment tools

B.1 community-as-partner model

The community-as-partner model was developed to illustrate public health nursing as a synthesis of public health and nursing. The model, originally titled the community-as-client model, has evolved to incorporate the philosophy that nurses work with communities as partners. This is congruent with what was learned about how communities (and people, for that matter) change and grow best—that is, by full involvement and self-empowerment, not by imposed programs and structures.

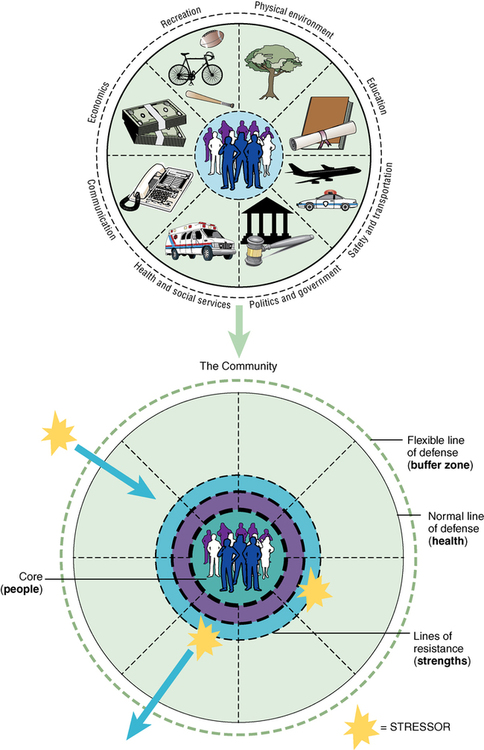

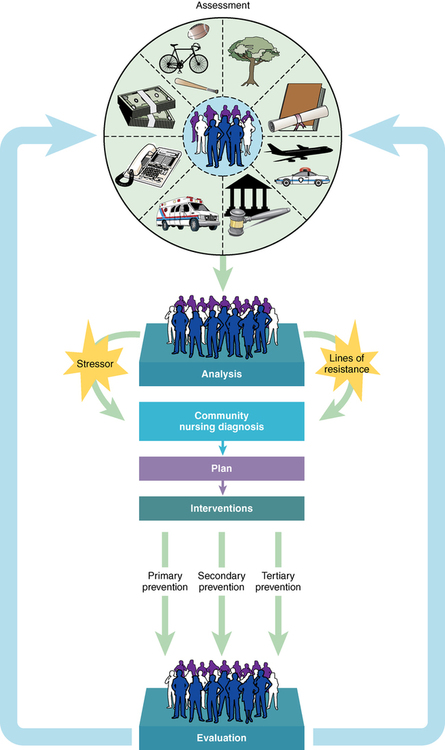

The community-as-partner model illustrates two key factors (Figure B-1). First, the focus is on the community, as shown by the community assessment wheel at the top of the model. Second, the nursing process is applied to the community as a whole.

The model’s “heart” is the assessment wheel (Figure B-2), which shows that the people actually are the community—the core elements. Without people there is no community, and it is the people (their demographics, values, beliefs, and history) that are of interest to the public health nurse. Surrounding the people, and integral with them, are the identified eight subsystems of a community. These subsystems (i.e., physical environment, education, safety and transportation, politics and government, health and social services, communication, economics, recreation) both affect and are affected by the people. To understand this interaction, it is necessary to understand each subsystem; therefore, it is necessary to incorporate its assessment into the assessment of the people.

The “wheel” (actually the entire community, including the people and subsystems) is shown with broken lines between each subsystem to show that these are not discrete, but that all subsystems affect each other. Within the community are lines of resistance, those “strengths” that defend against stressors (e.g., a school-based program to prevent teen violence); identifying strengths in the community is as important as identifying “problems.” Surrounding the community are lines of defense, depicted in the model as “flexible” and “normal” to indicate that there are two types of defense: one is the usual (normal) “health” of a community and the other is more dynamic (flexible) and changes more rapidly. Two illustrations may assist in clarifying these lines. The flexible line of defense may be a temporary response to a stressor. For instance, an environmental stressor such as flash flooding or a major fire may call into play resources from within the community and from surrounding areas; these resources are considered the flexible lines of defense. The normal line of defense is the usual level of health a community has reached over time. Examples of normal lines of defense include the immunization rate, adequate housing, or access to Meals-on-Wheels for shut-ins; all of these contribute to the health of the community.

Stressors affect the community and may be from the community or from outside the community. Either way, the community’s response to stressors is mitigated by its overall health state—that is, by the strength of its lines of resistance and defense. Knowing these strengths is one purpose of the community assessment. In the analysis phase of the nursing process, the nurse will weigh the stressor and the degree of reaction it causes, to describe a community nursing diagnosis that, in turn, will give direction to goals and interventions. One method for stating the community nursing diagnosis is to state the “problem” as the degree of reaction (from which the goal is derived) and to state the “as related to” as stressors (“causes” that help define needed interventions). Using this method, an example of a community nursing diagnosis might be as follows: High rate of tuberculosis (the problem, the degree of reaction) related to poor hygiene and sanitation, crowded living conditions, poverty, and consumption of raw milk (stressors), as manifested by open garbage and poor ventilation, an average of 5.6 persons per household, and sale of raw milk for income (the “data” collected in your assessment).

Think for a moment how each subsystem contributes to the health of the community. The nurse can see how an inadequate infrastructure, such as lack of modern sewage treatment or unemployment, can affect the health of all of the citizens.

Many models exist to provide a framework for assessing a community. This systems model gives one other way to describe a community. Working with the community is a vital and challenging task for nurses. Using a model in which the community is viewed as a partner will help formulate community-focused interventions and promote the health of the entire community.

Data from Anderson ET, McFarlane J: Community As Partner theory and practice in nursing, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

B.2 Friedman family assessment model (short form)

Before using the following guidelines in completing family assessments, two words of caution are in order. First, not all areas included below will be germane for each of the families visited. The guidelines are comprehensive and allow depth when probing is necessary. The student should not feel that every subarea needs to be covered when the broad area of inquiry poses no problems to the family or concern to the health worker. Second, by virtue of the interdependence of the family system, one will find unavoidable redundancy. For the sake of efficiency, the assessor should try not to repeat data, but to refer the reader back to sections where this information has already been described.

Family structure

Extent of functional and dysfunctional communication (types of recurring patterns)

Extent of emotional (affective) messages and how expressed

Characteristics of communication within family subsystems

Extent of congruent and incongruent messages

Types of dysfunctional communication processes seen in family

Compare the family to American or family’s reference group values and/or identify important family values and their importance (priority) in family

Congruence between the family’s values and the family’s reference group or wider community

Congruence between the family’s values and family member’s values

Variables influencing family values

Values consciously or unconsciously held

Presence of value conflicts in family

Effect of the above values and value conflicts on health status of family

Family functions

Family child-rearing practices

Adaptability of child-rearing practices for family form and family’s situation

Who is (are) socializing agent(s) for child(ren)?

Cultural beliefs that influence family’s child-rearing patterns

Social class influence on child-rearing patterns

Estimation about whether family is at risk for child-rearing problems and, if so, indication of high-risk factors

Family’s health beliefs, values, and behavior

Family’s definitions of health-illness and their level of knowledge

Family’s perceived health status and illness susceptibility

Adequacy of family diet (recommended 24-hour food history record)

Function of mealtimes and attitudes toward food and mealtimes

Shopping (and its planning) practices

Person(s) responsible for planning, shopping, and preparation of meals

Physical activity and recreation practices (not covered earlier)

Family’s role in self-care practices

Medically based preventive measures (physicals, eye and hearing tests, and immunizations)

Family health history (both general and specific diseases—environmentally and genetically related)

Feelings and perceptions regarding health services

Family stress and coping

25. Short- and long-term familial stressors and strengths

26. Extent of family’s ability to respond, based on objective appraisal of stress-producing situations

27. Coping strategies utilized (present/past)

28. Dysfunctional adaptive strategies utilized (present/past; extent of usage)

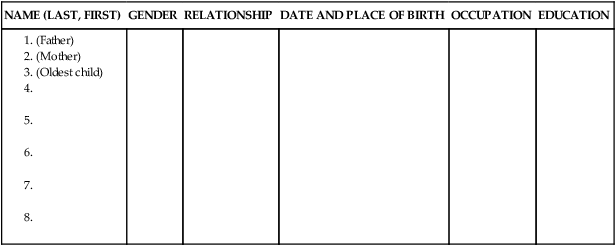

| NAME (LAST, FIRST) | GENDER | RELATIONSHIP | DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH | OCCUPATION | EDUCATION |

From Friedman MM, Bowden VR, Jones EG: Family nursing: research, theory, and practice, ed 5, 2003. Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

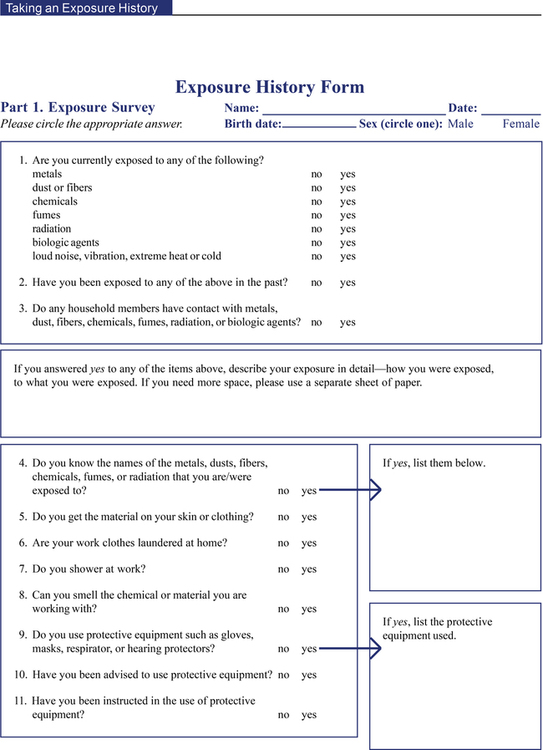

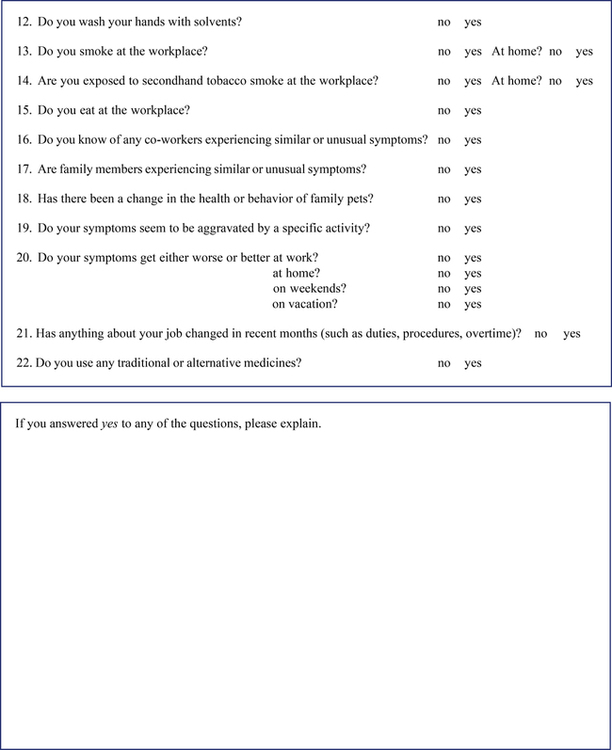

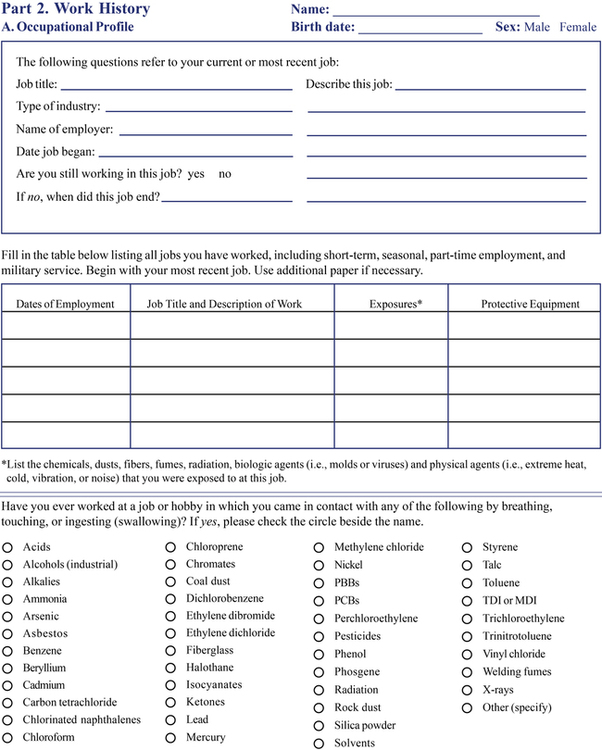

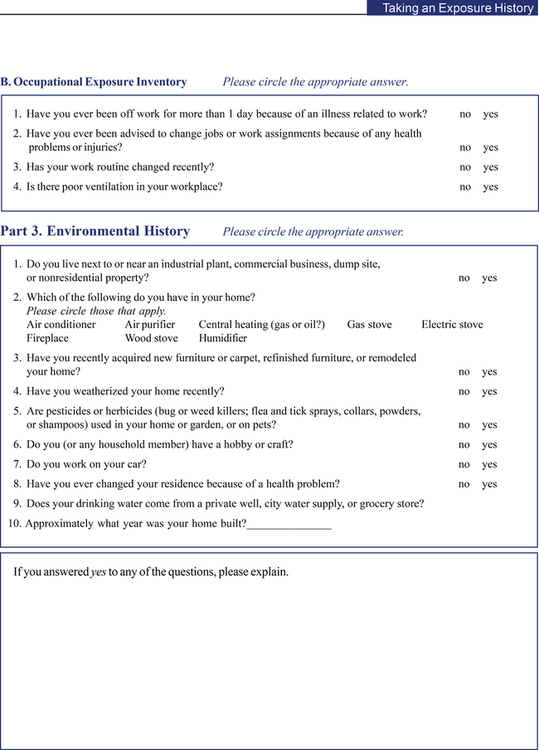

B.3 Comprehensive occupational and enviromental exposure history

From the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Toxicology and Environmental Medicine ATSDR Publication No. ATSDR-HE-CS-2001-0002. Developed by ATSDR in cooperation with NIOSH, 1992.

Targets of the Omaha system intervention scheme

• community outreach worker services

• interpreter/translator services

• medication action/side effects

• medication coordination/ordering

• relaxation/breathing techniques

• signs/symptoms—mental/emotional

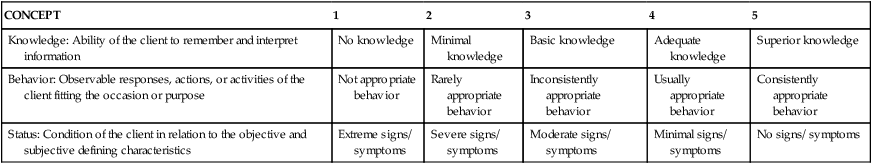

OMAHA SYSTEM PROBLEM RATING SCALE FOR OUTCOMES

| CONCEPT | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Knowledge: Ability of the client to remember and interpret information | No knowledge | Minimal knowledge | Basic knowledge | Adequate knowledge | Superior knowledge |

| Behavior: Observable responses, actions, or activities of the client fitting the occasion or purpose | Not appropriate behavior | Rarely appropriate behavior | Inconsistently appropriate behavior | Usually appropriate behavior | Consistently appropriate behavior |

| Status: Condition of the client in relation to the objective and subjective defining characteristics | Extreme signs/ symptoms | Severe signs/ symptoms | Moderate signs/ symptoms | Minimal signs/ symptoms | No signs/ symptoms |

Case study martha p.: Older woman Living in a deteriorating home

Information obtained during the first visit/encounter

Martha P. was a 93-year-old woman who lived by herself in a deteriorating house. She had kyphosis and arthritis that contributed to her unsteady gait. Martha rarely used her cane in her house, but steadied herself by holding on to furniture.

When a student nurse arrived, Martha was shivering under a thin blanket. Boxes filled with old papers were stacked along the walls. The student nurse asked Martha if she had wood for the stove that heated the house. She replied that she ran out of wood yesterday. “I don’t know what I’m going to do, but I’m not leaving this house.” She reported that people from a church had brought the last load of wood. The student asked permission to contact Concerned Neighbors, a volunteer organization that could provide firewood. Martha was pleased. The student expressed concern that the boxes of paper, especially those near the stove, were a fire hazard. “Those boxes have been there for years, and I use them to light the stove.” When the student asked if she could help Martha move the four boxes near the stove to the other wall, she grudgingly agreed.

The student nurse noted that Martha was wearing a “Lifeline necklace,” a fall alert system, and asked about her history of falls. Martha described how she moved around her home and fell in the bathroom last week when she was trying to take a sponge bath. She pushed the button, and “two nice gentlemen from the fire department came to pick me up.” The student and Martha walked around her house. They talked about where she fell in the past, how fortunate she was not to have injuries, and ways to decrease her risk of falling in the future. Martha was willing to have a personal care assistant visit weekly to help her with a bath and shampoo as long there was no charge. Before leaving, the student took Martha’s vital signs and blood pressure and noted that they were within normal limits. The student called Concerned Neighbors and arranged for firewood to be delivered that day; the student also telephoned a local health assistance organization to schedule a home health aide to provide personal care for the next week. Although Martha sounded grumpy, she asked the student to return.

Application of the Omaha system

Domain: Environmental

Problem: Residence (High Priority)

Unsafe storage of dangerous objects/substances

Safety (moved boxes away from stove; Martha unwilling to dispose of papers)

Other community resource (referred to Concerned Neighbors; arranged delivery of firewood)

Domain: Physiological

Problem: Neuromusculoskeletal Function (High Priority)

Mobility/transfers (ways to decrease risk of falling, absence of injuries, continue wearing “ Lifeline necklace”)

Mobility/transfers (how, when falls occurred)

Signs/symptoms—physical (falls/injuries; vital signs, blood pressure)

Domain: Health-related behaviors

Problem: Personal Care (High Priority)

Difficulty shampooing/combing hair

Personal hygiene (needed help with bathing, shampoo)

Paraprofessional/aide care (referred to health assistance organization for home health aide)

This case illustrates use of the Omaha System with a client in the home. Talk with your classmates and other colleagues about how this form of documenting care would help guide your practice as a home care nurse, ensuring the highest quality possible and client safety.

From Martin KS: The Omaha System: a key to practice, documentation, and information management, reprinted, ed 2, Omaha, Neb, 2005, Health Connections Press.

B.5 Cultural assessment guide

There must be an awareness of your own ethnocultural heritage, both as a person and as a nurse. In addition, an awareness and sensitivity must be developed to the health beliefs and practices of a client’s heritage. This awareness and sensitivity can be developed through careful assessment of a client’s heritage and cultural beliefs. The factors that must be explored during a multicultural nursing assessment are as follows: