Physical facilities

After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to:

• Identify specific areas within the surgical suite wherein attire and behaviors affect the manner of care delivery.

• Discuss how environmental layout contributes to aseptic technique.

• Describe methods of environmental controls that contribute to an aseptic environment.

• Describe the specialty rooms used for endoscopy, minimally invasive procedures, and urology.

The birth of a baby via an abdominal incision.

Surgical procedures that use natural body orifices or percutaneous techniques with fiberoptic lighting to employ cameras and long specialized instruments during tissue manipulation and invasive intervention (e.g., colonoscopy, bronchoscopy).

Interventional radiographic procedure

A specialized surgical procedure that permits the use of radiologic imaging during tissue manipulation and invasive intervention through small incisional portals.

A unidirectional flow of clean air from a higher plane to lower exhaust grilles. The uninterrupted flow permits higher air changes per hour (ACH) for a cleaner environment around the sterile field.1

Minimally invasive surgical (MIS) procedure

Surgical procedures that use small incisions and fiberoptic lighting to employ cameras and long specialized instruments during tissue manipulation and invasive intervention (i.e., laparoscopy or mediastinoscopy).

A specialized room where the actual surgery takes place. This room is one part of the restricted area of the surgical suite.

A special room within the suite where sterile supplies are stored for ease of use. This room is one part of the restricted area of the surgical suite.

A room with a double sink that is separated from the OR by a door and where select clean and contaminated activities take place during the process of the surgical procedure. Some substerile rooms have warming cabinets for solutions or blankets and a steam autoclave. A disposal sink for contaminated fluids might be in here (e.g., hopper).

A collection of rooms that are used interactively during a surgical procedure wherein each room has a specific purpose (e.g., OR, substerile room, scrub sink room, and sterile storage core).

An invisible layer of heat emanating from the equipment, team members, and the patient that can change the airflow and particulate distribution in the presence of laminar air diffusers.3,4

Physical layout of the surgical suite

Efficient use of the physical facilities is important. The design of the surgical suite offers a challenge to the planning team to optimize efficiency by creating realistic traffic and workflow patterns for patients, visitors, personnel, and supplies. The design also should allow for flexibility and future expansion. Architects consult surgeons, perioperative nurses, and surgical services administrative personnel before designating functional space within the surgical suite.10

Type of physical plant design

Most surgical suites are constructed according to a variation of one or more of four basic designs:

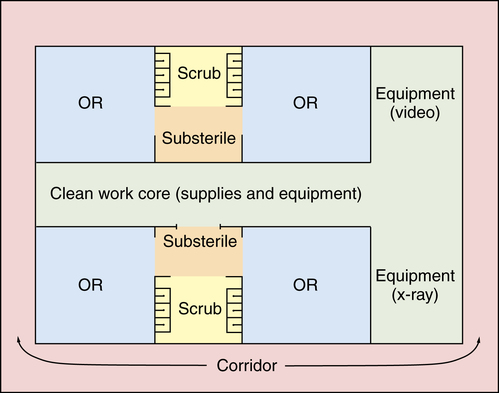

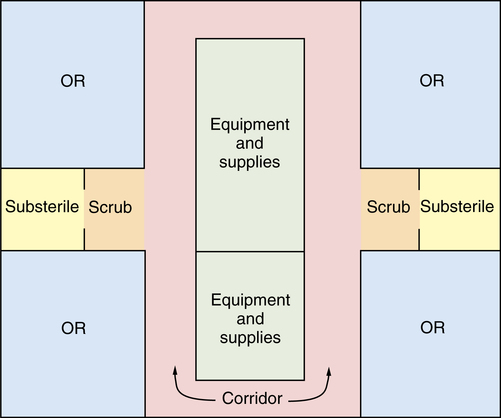

1. Central corridor, or hotel plan (Fig. 10-1).

2. Central core, or clean core plan with peripheral corridor (Fig. 10-2).

3. Combination central core and peripheral corridor, or racetrack plan (Fig. 10-3).

4. Grouping, or cluster plan with peripheral and central corridor (Fig. 10-4).

Each design has its advantages and disadvantages.8,9 Efficiency is affected if corridor distances are too long in proportion to other space, if illogical relationships exist between space and function, and if inadequate consideration was given to storage space, material handling, and personnel areas.

Location

The surgical suite is usually located in an area accessible to the critical care surgical patient areas and the supporting service departments, the central service or sterile processing department, the pathology department, and the radiology department. The size of the hospital is a determining factor because locating every desirable unit or department immediately adjacent to the surgical suite is impossible.

A terminal location is necessary to prevent unrelated traffic from passing through the suite. A location on a top floor is not necessary for microbial control because all air is specially filtered to control dust. Traffic noises may be less evident above the ground floor. Artificial lighting is controllable, so the need for daylight is not a factor; in fact, daylight may be a distraction during the use of video equipment and other procedures that require a darkened environment. Most surgical suites have solid walls without windows. However, some ambulatory surgery rooms have windows to create an ambiance of openness in the suite.

Space allocation and traffic patterns

Space is allocated within the surgical suite to provide for the work to be done, with consideration given to the efficiency with which it can be accomplished. The surgical suite should be large enough to allow for correct technique yet small enough to minimize the movement of patients, personnel, and supplies.

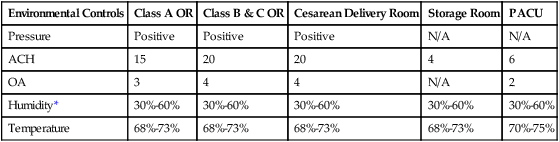

Provision must be made for traffic control. The type of design predetermines traffic patterns. Everyone—staff, patients, and visitors—should follow the delineated patterns in appropriate attire. Signs should be posted that clearly indicate the attire and environmental controls required (Table 10-1). The surgical suite is divided into three areas that are designated by the physical activities performed in each area.

TABLE 10-1

Environmental Controls in the Surgical Suite

| Environmental Controls | Class A OR | Class B & C OR | Cesarean Delivery Room | Storage Room | PACU |

| Pressure | Positive | Positive | Positive | N/A | N/A |

| ACH | 15 | 20 | 20 | 4 | 6 |

| OA | 3 | 4 | 4 | N/A | 2 |

| Humidity* | 30%-60% | 30%-60% | 30%-60% | 30%-60% | 30%-60% |

| Temperature | 68%-73% | 68%-73% | 68%-73% | 68%-73% | 70%-75% |

*Note: Humidity is expected to decrease as low as 20% by the 2012 edition of the AIA Guidelines. The rationale is that the old 30% to 60% is based on the use of flammable anesthetics and the risk of fire by static spark, which is not a consideration in modern times.

Modified from the Facility Guidelines Institute: Guidelines for design and construction of health care facilities, Chicago, 2010, ASHE (American Society for Healthcare Engineering), available at www.fgiguidelines.org/2010guidelines.html.

Unrestricted area

Street clothes are permitted. A corridor on the periphery accommodates traffic from outside, including patients. This area is isolated by doors from the main hospital corridor and elevators and from other areas of the surgical suite. It serves as an outside-to-inside access area (i.e., a transition zone). Traffic, although not limited, is monitored at a central location.

Semirestricted area

Traffic is limited to properly attired, authorized personnel. Scrub suits and head coverings are required attire. This area includes peripheral support areas, central processing, and access corridors to the ORs. The patient’s hair is also covered. Bald heads are covered to prevent distribution of dead skin cells and dander.

Restricted area

Masks are required to supplement OR attire where open sterile supplies and scrubbed personnel are located. Sterile procedures are carried out in the OR. There are also scrub sink areas and substerile rooms or clean core areas where unwrapped supplies are sterilized. Personnel entering this area for short periods, such as laboratory technicians, may wear clean surgical cover gowns or jumpsuits to cover street clothes. Hair covering is worn, and masks are donned as appropriate.

Transition zones

Both patients and personnel enter the semirestricted and restricted areas of the surgical suite through a transition zone. This transition zone, inside the entrance to the surgical suite, separates the OR corridors from the rest of the facility. Masks, caps, shoe covers, and cover gowns (or jumpsuits) may be located on a cart near transition zones adjacent to restricted areas. Nonsurgical personnel who need to enter the restricted zone can don a cover gown or jumpsuit, cap, shoe covers, and mask before proceeding to the designated OR.

Preoperative admission and holding unit

A designated unit in the unrestricted zone should be available for preoperative patients to change from street clothes into a gown and wait with their families before their surgical procedure. The decor should create a feeling of warmth and security. Lockers should be provided for safeguarding patient clothing. The location of the area should shield the patient and family from potentially distressing sights and sounds. Lavatory facilities and handwashing stations must be available. Alcohol-based hand-rub dispensers should be conveniently located in each patient care cubicle.

The area must ensure privacy and offer 80 ft2 per patient of space to accommodate a transport cart.a It may be compartmentalized with individual cubicles or be an open area with curtains. Curtains do not deflect sound and offer little privacy when the nurse is performing assessment and having conversations with the patient. Curtains also accumulate dust and particles and should be laundered on a regular basis.

Insertion of intravenous (IV) lines may be done here. In some cases, nerve blockades for pain management may be done in the holding area as ambulatory procedures. These procedures require good lighting. Each cubicle is equipped with oxygen, suction, and devices for monitoring blood pressure. A crash cart should be easily accessible for emergencies.

A nurses’ station within the area provides close patient observation and dispensers for medication storage. Computer access to patient electronic medical records (EMRs), such as laboratory reports, and to patient care documentation facilitates documentation in patient records. Care is taken not to have loud conversations at the nurses’ station. Private information may be overheard by patients and families.

Assignment and scheduling boards should not be within the view of the patients to avoid breaching privacy standards. When wipe-off boards are used for daily scheduling, care is taken not to use patient names. Coordination of the holding room staff and the personnel managing the surgical schedule is essential to prevent delays. More information about preoperative patient care areas is available in Chapter 21.

Some preoperative holding units serve as ambulatory care areas after the surgical procedure. Patients who are admitted in the morning are brought back to the holding unit to recover. They can go home a few hours after the surgical procedure.

Induction room

Some surgical departments have an induction room within the restricted area adjacent to each OR, or pair of ORs, where the patient is prepared physiologically for anesthesia administration preoperatively and before actual induction of general anesthesia and airway management. Families of patients are not permitted in this area. Appropriate surgical attire is required, including a mask.

Peripheral IV lines, central lines, and invasive arterial monitoring lines are placed and regional anesthesia (i.e., epidural catheter for postoperative pain management) may be induced in this area. Performing these procedures in an induction room saves actual OR time, which is more costly to provide. Induction rooms are more common in larger facilities, where procedures, such as open heart surgery or transplantation, are performed.

In some induction rooms (not all), patients are premedicated and stabilized on the same OR bed that will be used for the procedure. The OR bed is used as the transport vehicle to the OR, where it is connected and locked to a base unit permanently mounted in the floor. This minimizes the number of times critically ill patients are moved from one surface to another.

Postanesthesia care unit

The postanesthesia care unit (PACU) may be outside the surgical suite, or it may be adjacent to the suite so that it may be incorporated into the unrestricted area with access from both the semirestricted area and an outside corridor. In the latter design, the PACU becomes a transition zone for the departure of patients.

Hospitals and ambulatory care facilities accommodate patients and their families during the perioperative waiting period. A designated waiting area is provided for families of surgical patients. This is most conveniently located outside the surgical suite adjacent to the recovery area. More information about the PACU can be found in Chapter 30.

Peripheral support areas

Adequate space must be allocated to accommodate the needs of OR personnel and support services. The need for equipment, supply, and utility rooms and housekeeping determines support space requirements. Equipment and supply rooms should be decentralized and placed near the appropriate ORs.

Central control desk

From a central control point, traffic in and out of the surgical suite may be observed. This area usually is within the unrestricted area but adjacent to the semirestricted corridor. The clerk-receptionist is located at the control desk to coordinate communications. A pass-through window may be used to stop unauthorized people, to schedule surgical procedures with surgeons, and to receive drugs, blood, and various small supplies. A computerized pneumatic tube system within the hospital can speed the delivery of small items and paperwork, thus eliminating some courier services, such as from the pharmacy to the control desk. Tissue specimens and blood samples also can be sent to the laboratory through some tube systems. The tubes used to send items should be periodically cleaned with an approved disinfectant solution.

Computers and printers may be located in the control area. Information systems and computers assist in financial management, statistical recording and analysis, scheduling of patients and personnel, materials management, and other functions that evaluate the use of facilities. An integrated system interfaces with other hospital departments. It may have a hard-wired modem or wireless Internet that allows surgeons to schedule surgical procedures directly from their offices.

Retrieval for review of patient records gives the perioperative nurse manager the opportunity to evaluate the patient care given and documented by nurses. Personnel records can be maintained. Other essential records can be stored in and retrieved from computer databases on a password-controlled basis. The central processing unit for the OR computer system usually is located in or near the central administrative control area. A fax machine may be available for the electronic transfer of documents, records, and patient care orders between the OR and surgeons’ offices.

Security systems usually can be monitored from the central administrative control area. Alarms are incorporated into electrical and piped-in systems to alert personnel to the location of a system failure. A centralized emergency call system facilitates summoning help. Some facilities have a panic button to summon the security department. Narcotics are kept in locked cabinets and can be signed out only by appropriate personnel.

Access to exchange areas, offices, and storage areas may be limited during evening and night hours and on weekends. Doors may be locked. Some hospitals use alarm systems, video surveillance in hallways and ORs, and electronic metal detection devices to control intruders and to prevent theft or vandalism. Computers and records must be secured to protect patient confidentiality.

Offices

Offices for the administrative patient care personnel and the anesthesia department should be located with access to both unrestricted and semirestricted areas. The staff members frequently need to confer with outside people and need to be kept informed of activities within all areas of the suite.

Locker rooms and lounges

Dressing rooms with secure lockers are provided for both male and female personnel to change from street clothes into OR attire before entering the semirestricted area, and vice versa. The area should be secure from unauthorized personnel. Doors separate this area from lavatory facilities and adjacent lounges.

Walls in the lounge areas should have an aesthetically pleasing color or combination of colors to foster a calming atmosphere. A window view of the outdoors is psychologically desirable because many staff members arrive for the day shift when it is still dark outside. Affect is enhanced by natural sunlight. Some personnel bring a meal, so a refrigerator designated only for food should be located in this room. A routine refrigerator cleaning schedule should be established. Antiseptic hand-rub dispensers should be conveniently located at the entrance and near all food storage areas.

Dictating equipment, computers, and telephones should be available for surgeons in the physicians’ lounge or in an adjacent semirestricted area.

Conference room/classroom

Ideally, a conference room or a classroom is located within the semirestricted area with entrance/exit doors to unrestricted areas. This room is used for patient care staff inservice educational programs and is used by the surgical staff for teaching. Closed-circuit television and video equipment may also be available for self-study. The departmental reference library may be housed here. Tables and chairs for staff should be sturdy and easily cleanable. Shoe covers and masks should not be worn in this room. Antiseptic hand-rub dispensers should be conveniently located at the entrance.

Some facilities permit covered beverages and small snacks during meetings. Departmental holiday parties or special event celebrations may be set up in here.

Support services

The size of the health care facility and the types of services provided determine whether laboratory and radiology equipment is needed within the surgical suite.

Laboratory

A small laboratory where the pathologist can examine tissue specimens and perform frozen sections expedites the decisions that the surgeon must make during a surgical procedure when a diagnosis is questionable. A designated refrigerator for storing blood for transfusions also may be located in this room. Tissue specimens may be tested here by frozen section before they are delivered to the pathology department for permanent section.

Radiology services

Special procedure rooms may be outfitted with x-ray and other imaging equipment for diagnostic and invasive radiologic procedures or insertion of catheters, pacemakers, and other devices. The walls of these rooms contain lead shields to confine radiation. A darkroom for processing x-ray films usually is available within the surgical suite for immediate processing of scout films or contrast dye studies of organ systems.

Work and storage areas

Clean and sterile supplies and equipment are separated from soiled items and trash. If the surgical suite has a clean core area, only clean or sterile items are stored there. The air handlers are set to positive pressure as in the restricted area, so the doors should always remain closed when traffic is not entering or leaving.

Soiled items are taken to the decontamination area for processing before being stored, or they are taken to the disposal area. The air handlers in the contaminated areas are set to negative pressure as in the corridors, so the doors should remain closed when personnel are not entering or leaving. Work and storage areas are provided for handling all types of supplies and equipment, whether clean or contaminated.

Anesthesia work and storage areas

Space must be provided for storing anesthesia equipment and supplies. Gas tanks are stored in a well-ventilated, negative-pressure area separated from other supplies. Care is taken not to allow tanks or cylinders to be knocked over or damaged. They should stand upright in a secure stable base for safety. Nondisposable items must be thoroughly decontaminated and cleaned after use in an area separate from sterile supplies. A separate workroom usually is provided for care and processing of anesthesia equipment. Dirty and clean supplies must be kept separated.

The storage area includes a secured space for anesthetic drugs and agents. Some facilities have drug-dispensing machines that require positive identification to obtain medications for patient use. Larger facilities have a pharmaceutical station where a pharmacist dispenses drugs on a per-case basis. Signatures are required for controlled substances. Unused drugs are returned to the pharmacist for accountability.

Housekeeping storage areas

Cleaning supplies and equipment need to be stored; the equipment used within the restricted area is kept separate from that used to clean the other areas. Therefore, more than one storage area may be provided for housekeeping purposes, depending on the design and size of the surgical suite. Sinks are provided, as are shelves for supplies. Trash and soiled laundry receptacles should not be allowed to accumulate in the same room where clean supplies are kept; separate areas should be provided for these. Conveyors or designated elevators may be provided for prompt removal of bags of soiled laundry and trash from the suite.

Central processing area

Conveyors, dumbwaiters, or elevators connect the surgical suite with a central processing area on another floor of the hospital. If efficient material flow can be accomplished, support functions can be removed from the surgical suite. Effective communications and a reliable transportation system must be established. Some ORs send all of the instruments and supplies to the sterile processing department for cleaning, packaging, sterilizing, and storing. This system eliminates the need for some work and storage areas within the surgical suite, but exchange areas must be provided for carts. The movement of clean and sterile supplies must be kept separate from that of contaminated items and waste by means of space and traffic patterns.

Utility room

Some hospitals use a closed-cart system and take contaminated instruments to a central area outside the surgical suite for cleanup. Some perform cleanup procedures in the substerile room. Many, by virtue of the limitations of the physical facilities, bring the instruments to a utility room. This room contains a washer-sterilizer, sinks, cabinets, and all necessary aids for cleaning. If the washer-sterilizer is a pass-through unit, it opens also into the general workroom, which eliminates the task of physically moving instruments from one room to another.

General workroom

The general work area should be as centrally located in the surgical suite as possible to keep contamination to a minimum. The work area may be divided into a cleaning area and a preparation area. If instruments and equipment from the utility room are received from the pass-through washer-sterilizer into this room, an ultrasonic cleaner should be available here for cleaning instruments that the washer-sterilizer has not adequately cleaned. Otherwise, the ultrasonic cleaner may be in the utility room.

Instrument sets, basin sets, trays, and other supplies are wrapped for sterilization here. The preparation and sterilization of instrument trays and sets in a central room ensures control. This room also contains the stock supply of other items that are packaged for sterilization. The sterilizers that are used in this room may open also into the next room, the sterile supply room. This arrangement helps to eliminate the possibility of mixing sterile and nonsterile items.

Storage

Technology nearly tripled the need for storage space in the twenty-first century. Many older surgical suites have inadequate facilities for storage of sterile supplies, instruments, and bulky equipment. Those responsible for calculating adequate storage space for instruments, sterile and unsterile supplies, and mobile equipment, such as special OR beds, specialty carts, and equipment, should consider the size of the entire surgical suite. American Institute of Architects (AIA) 2010 Guidelines state that a minimum of 150 ft2 or 50 ft2 per OR, whichever is greater, should be dedicated to equipment storage to prevent accumulation of machines and supplies in hallways. Blocked hallways prevent rapid transfer of crash carts and emergency equipment.

The OR storage space does not include additional storage space needed for postanesthesia equipment. Anesthesia storage should be considered separately. Use of a case cart system may slightly decrease the amount of instrument space needed. Plans should include accommodation for the size of each type of case cart used and the numbers that will be in the suite at a given point in the daily surgical schedule.

Sterile supply room

Most hospitals keep a supply of sterile drapes, sponges, gloves, gowns, and other sterile items ready for use in a sterile supply room within the surgical suite. As many shelves as possible should be freestanding from the walls, which permits supplies to be put into one side and removed from the other; thus, older packages are always used first. However, small items must be contained in boxes or bins to prevent them from falling to the floor. Inventory levels should be large enough to prevent running out of supplies, yet overstocking of sterile supplies should be avoided. Storage should be arranged to facilitate stock rotation.

The sterile storage should be as close as possible to the sterile processing area and should be under positive pressure. Access to the sterile storage area should be limited; it should be separated from high-traffic areas, and the doors should be closed. Humidity and temperature should be controlled. Humidity in excess of 70% causes concern for condensation within sterile packages and may permit microorganism transfer by capillary action.

Instrument room

Most hospitals have a separate room or a section of the general workroom designated for storing nonsterile instruments. The instrument room contains cupboards in which all clean and decontaminated instruments are stored when not in use. Instruments usually are segregated on shelves according to surgical specialty services.

Sets of basic instruments are usually cleaned, assembled, and sterilized after each use. Special instruments such as intestinal clamps, kidney forceps, and bone instruments may be stored after cleaning and decontamination. Sets are then made up according to each specialty as needed.

Scrub room

An enclosed area for preoperative cleansing of hands and arms should be provided adjacent to each OR. Water spills on the floor are particularly hazardous if the scrub area is in a traffic corridor. An enclosed scrub room is a restricted area within the surgical suite. Paper towel dispensers and mirrors should be located in this area. Trash receptacles, limited to only those items used within this room, should be emptied several times per day. Some facilities have boxes of additional caps, masks, shoe covers, and eye protection in the event of biologic contamination requiring a change of these items during a procedure. The contaminated item should be discarded in the biohazard trash bin in the OR after changing.

Operating room

Each OR, regardless of size, is a restricted area because of the need to maintain a controlled environment for sterile and aseptic techniques (Fig. 10-5).

Categories of operating rooms

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) defines three categories or classes of surgical facilities based on the types of procedures performed therein. The AIA Guidelines in cooperation with the ACS use specific criteria when determining safe environmental factors for surgical facilities and include provision for all types of surgical interventions. The criteria include minimal floor space, types of anesthetics used, and circumferential clearance around the OR bed. The classes of ORs with minimal floor space are as follows:

• Class A: 150 ft2 floor area with 12 ft minimum clear dimensions at the head, sides, and foot of the operating bed.

• Class B: 250 ft2 floor area with 15 ft minimum clear dimensions at the head, sides, and foot of the operating bed.

• Class C: 400 ft2 floor area with 18 ft minimum clear dimensions at the head, sides, and foot of the operating bed.

Other ORs not designated by class range in size from 600 to 650 ft2 with a 24- to 25-foot width and accommodate multiple ceiling-mounted booms, monitors, and high-technology equipment such as robotics and controlling consoles.

Size determinations

The size of individual ORs varies according to use. Class A ORs are commonly used for smaller procedures performed with topical, local, or limited regional blocks that have minimal equipment needs. Many ambulatory centers have procedure rooms that fit this usage.

Class B rooms are better suited for procedures in which the patient may be sedated and physiologically supported with IV medication. General anesthesia and spinal or epidural blocks can be used. Intermediate to complex procedures are performed in these rooms. Additional space is appropriate where the potential for larger equipment and longer procedures is possible.

It is desirable to have the ORs in a hospital setting the same size so that they can be used interchangeably to accommodate elective and emergency surgical procedures. Class C ORs provide adequate space for typical multipurpose procedure rooms with at least 400 ft2 of clear floor space. Approximately 20 ft2 of space should be planned between fixed cabinets and shelves on two opposing walls if possible. A specialized room, such as one equipped for cardiopulmonary bypass or trauma, may require as much as 600 ft2 of useful space.

A room may be designed for a specialty service if use by that service will be high. The room must accommodate equipment, such as lasers, microscopes, or video equipment, either fixed (permanently installed) or portable (movable). Portable equipment requires more floor space.

Some rooms are designated for special procedures, such as gastrointestinal endoscopy, interventional radiologic studies, or the application of casts. Other rooms have adjacent areas used for specific purposes, such as visitor viewing galleries, or for installing special equipment, such as monitors or x-ray devices for imaging.

Operating room humidity

An air-conditioning system controls humidity. High relative humidity (weight of water vapor present) should be maintained between 30% and 60%. Moisture provides a conductive medium and allows a static charge to flow to ground as fast as a spark is generated.

The humidity gradient standard in current use is based on previous decades when the use of flammable anesthetics posed the risk of explosion after a spark. The AIA is planning to lower the requirements in the 2012 Guidelines because flammable anesthetics are no longer used.

Operating room temperature

OR temperature is maintained within a range of 68° F to 73° F (20° C to 23° C). A thermostat to control room temperature can be advantageous to meet patient needs; for example, the temperature can be increased to prevent hypothermia in pediatric, geriatric, and burn patients. Overmanipulation of controls can result in calibration problems. Controls should not be adjusted solely for the comfort of team members; patient normothermia is a strong consideration. Only the maintenance department can regulate temperature in some surgical suites; this department should be called early enough to reset the temperature for patients at risk for hypothermia.

Substerile room

A group of two, three, or four ORs may be clustered around a central scrub area, work area, and a small substerile room. Only if the last-mentioned room is immediately adjacent to the OR and separated from the scrub area is it considered the substerile room throughout this text.

A substerile room adjacent to the OR contains enclosed storage cupboards, a sink, steam sterilizer, STERIS 1E™, and a warming cabinet. Although cleaning and sterilizing facilities are centralized, either inside or outside of the surgical suite, a substerile room with this equipment offers the following advantages:

• It saves time and steps. The circulating nurse can do emergency cleaning and sterilization of small items here, which reduces waiting time for the surgeon, reduces anesthesia time for the patient, and saves steps for the circulating nurse. The circulating nurse, or scrub person if necessary, can lift sterile articles directly from the sterilizer onto the sterile instrument table without transporting them through a corridor or another area.

• It reduces the need for other personnel to obtain sterile instruments and allows the circulating nurse to stay within the room.

• It allows for better care of instruments and equipment that require special handling. Certain delicate or sensitive instruments or perhaps a surgeon’s personally owned set usually are not sent out of the surgical suite. Only the personnel directly responsible for their use and care handle them; the circulating nurse and scrub person can clean them within the confines of the OR and this adjacent room.

Rooms adjacent to orthopedic or cast rooms should have a sink with a plaster trap for disposal of casting solutions.

The substerile room also usually contains a combination blanket and solution warmer, cabinets for storage, and perhaps a refrigerator for blood and medications. Empty sterile specimen containers and labels may be conveniently stored in this room. Slips for charges or other records may be kept here. Individual hospitals may find it convenient to keep other items in this room to allow the circulating nurse to remain in or immediately adjacent to the OR during the surgical procedure.

Doors

Doors should be 4 ft wide for ease in moving patients on carts and in beds. Ideally, sliding doors should be used exclusively in the OR for the main corridor. They eliminate the air currents caused by swinging doors. Microorganisms that have previously settled in the room are disturbed with each swing of the door. The microbial count is usually at its peak at the time of the skin incision because this follows disturbance of air from gowning, draping, movement of personnel, and opening and closing of doors.

Sliding doors should not recede into the wall like pocket styles but should be of the surface-sliding type. Fire regulations mandate that sliding doors for ORs be of the type that can be swung open if necessary. Doors do not remain open either during or between surgical procedures. The room air-handlers generate higher pressure than in the halls to minimize the amount of dust and debris pulled in toward the sterile field. Closed doors decrease the mixing of air within the OR with that in the corridors, which may contain higher microbial counts. Air pressure in the room also is disrupted if the doors remain open.

When construction or renovation is in process, always keeping the doors closed when not transporting patients is important because the ORs are ventilated with positive pressure. The air-handling systems are under a strain because of the disrupted processes and are further compromised when the airflow is allowed to equalize. This causes unstable temperature and humidity control. The desired temperature should be between 68° F and 73° F, with a relative humidity of 30% to 60%.

The door to the substerile area is usually a swinging style door with a small window. These doors are not used for moving patients in and out of the OR and should remain closed. During the surgical procedure, the microbial count rises every time doors swing open from either direction. Also, swinging doors may touch a sterile table or person. The risk of catching hands, equipment cords, or other supplies is increased. Always look through the window before opening this door to prevent contamination or injury.

Ventilation

The OR ventilation system must ensure a controlled supply of filtered air under positive pressure. The primary concerns for flow of ventilation include how the air is distributed, filtered, and exhausted.6,7 ACH are important concerns based on the size of the individual OR. Heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) manufacturers continually study the best ways to ventilate ORs and provide ventilation systems compatible with the needs of the sterile team for aseptic air quality.5

Air changes and circulation provide fresh air and prevent accumulation of anesthetic gases in the room. Concentration of gases depends solely on the proportion of pure air entering the air system to the air being recirculated through the system. Fifteen ACH with three exchanges of outside air (OA) are recommended for class A ORs. Class B and C ORs and cesarean delivery suites require 20 ACH with four OA exchanges according to the 2010 AIA Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities.b

A gas scavenger system is used to prevent the buildup of waste anesthetic gases where general inhalation anesthesia is used. The scavenger attaches directly to the outflow of the anesthesia machine.

Various types of scavengers, vacuum systems, and smoke evacuators are used throughout the OR to minimize air pollutants that are health risks for patients and perioperative team members. The American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) sets the standard for safe ventilation.

If new air ducts are installed, they should be thoroughly cleaned before activation to prevent the dispersal of particulate material into the air. The risk for airborne contaminants is significantly increased.

Laminar airflow

Ultraclean laminar airflow is installed in some ORs to combat airborne particulate contamination by providing 70 to 160 ACH.2 Laminar airflow is a high-pressure, unidirectional air-moving diffuser housed in a cluster in a wall or ceiling enclosure. It is designed to flow uninterrupted from the cleanest area to the less clean area into air return grilles in the lower sidewalls. Cool air from the laminar diffuser travels more quickly than isothermic air.2,7

The airflow is divided into tiny linear columns of cool clean air that generates little velocity and blowing as it courses toward the sterile field. Objects that emit thermal plume, such as spotlights, persons, or equipment, cause the air currents to move in a different direction. Horizontal airflow passes from the wall diffuser to an opposite lower return grille.7 Objects in the air pathway shed particulate into the clean airstream (Fig. 10-6). Vertical airflow styles have fewer obstacles to the line of direction of the air. Vertical downward airflow is designed to flow from the top of the room, over the patient, lights, and equipment, and continue downward toward the lower corners of the room where the air return grilles are located.1,4 In contemporary ORs that use laminar airflow, three styles of vertical downward-directed airflow originate in the ceiling directly clustered over the field with slightly different effects.11

1. Standard vertical laminar flow provides a narrow boundary of operating space that begins at the ceiling and interfaces with the field, personnel, and ambient room air before it is exhausted through air return grilles (Fig. 10-7).

2. Air curtained vertical flow uses a peripheral secondary airflow at a higher velocity to widen and frame the primary laminar flow from the ceiling to the lower pressure air return grilles in the base of the walls (Figs. 10-8 and 10-9).

3. Physical curtained vertical flow uses air foils hanging from the ceiling on four sides to maintain the downward direction of airflow. The air funnels down toward the field, flowing around and behind the team (Fig. 10-10).

Obstacles to laminar airflow effectiveness

Objects that pass between the flow of clean air and the sterile field around the patient shed particles that can contaminate the surgical site. Heat emanating and rising from the team members, the patient, and equipment referred to as thermal plume changes the course of the laminar flow (Fig. 10-11). Several physical barriers that interrupt airflow and return include the following:

• Ceiling booms with surgical machinery and equipment

• Mayo stands over the patient

Laminar airflow was first trialed during hip replacement surgery by Sir John Charnley in Great Britain in the 1950s. Charnley believed that if particulate could be removed from the air, the 7% infection rate could drop. His studies showed that the infection rate did fall to less than 2%. Although the laminar system contributes to removing particulates, the improvements in sterile technique overall may have a larger effect on infection rate.

Other types of filtered air-delivery systems that have a high rate of airflow are as effective in controlling airborne contamination. Filtration through high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters can be 99.7% efficient in removing particles that are larger than 0.3 mm. These microbial filters in ducts filter the air, practically eliminating all dust particles. The ventilating system in the surgical suite is separate from the hospital’s general system and is to be cleaned, inspected, and maintained on a preventive maintenance (PM) schedule.

Positive air pressure in each OR is greater than that in corridors, scrub areas, storage, and substerile rooms. Positive pressure forces air from the room. The air enters at the ceiling and leaves through the grilles at floor level. Microorganisms and particulate in the air can enter the room unless positive pressure is maintained. Closed doors maintain this environment and prevent equalization of air pressure. The recommended parameters include a dual filtration system with two filters in succession. The first filter should be at least 30% efficient, and the second filter should be at least 90%. Filter changes and duct cleaning should be on a PM schedule with OR maintenance.

Floors

In the past, floors were conductive enough to dissipate static from equipment and personnel but not enough to endanger personnel from shock or cause explosions from flammable anesthetic gases. Conductivity is not a prime concern in contemporary OR design because explosive anesthetic gases, such as cyclopropane, are no longer used.

The most common flooring used today is seamless polyvinyl chloride that is continued up the sides of the wall for 5 or 6 inches and welded into place. These materials should not degrade or stain with age and cleaning. Metal oxides can be incorporated to decrease the slipperiness of the surface when wet.

A variety of hard plastic, seamless materials are used for minor procedure room floors. The surface of all floors should not be porous but suitably hard for cleaning with the flooding, wet-vacuuming technique. Personnel fatigue may be related to the type of flooring, which can be too hard or too soft. Cushioned flooring is available. The floor should be slip-proof when wet because surgical hand cleansing causes splashes and spills around the scrub sink and into the OR, where the hands are dried.

Most of the glues and adhesives used in the installation of the flooring are malodorous and potentially toxic. During construction or renovation, care is taken to vent these fumes from the area. A minimum of 2 weeks may be needed to fully rid the area of the smell before it can be safely used for patient care.

Floors in older buildings may need reinforcement to support larger and more sophisticated equipment. Some of the wiring may be run in conduits under the floor.

Walls and ceiling

Finishes of all surface materials should be hard, nonporous, fire-resistant, waterproof, stainproof, seamless, nonreflective, and easy to clean. The ceiling should be a minimum of 10 ft high and have seamless construction. The height of the ceiling depends on the amount and types of ceiling-mounted equipment.9 The ceiling color should be white to reflect at least 90% of the light in even dispersion.

Walls should be a pastel color, with paneling made of hard vinyl material that is easy to clean and maintain. Seams should be sealed with a silicone sealant. Laminated polyester or smooth painted plaster provides a seamless wall; epoxy paint has a tendency to flake or chip. Dust and microorganisms can collect between tiles because the mortar between them is not smooth. Most grout lines, including those made of latex, are porous enough to harbor microorganisms even after cleaning. Tiles can also crack and break. A material that is able to withstand considerable impact also may have some value in noise control. Stainless steel cuffs at collision corners help prevent damage.

Walls and ceilings often are used to mount devices, utilities, and equipment in an effort to reduce clutter on the floor. The ceilings should be reinforced with steel beams to support the load. In addition to the overhead operating light, the ceiling may be used for mounting an anesthesia service boom, operating microscope, x-ray image intensifier, electronic monitor, and a variety of hooks, poles, and tubes. Demands for ceiling-mounted equipment are diversified.

Suspended track mounts are not recommended because they engender fallout of dust-carrying microorganisms each time they are moved. If movable or track ceiling devices are installed, they should not be mounted directly over the operating bed but away from the center of the room and preferably recessed into the ceiling to minimize the possibility of dust accumulation and fallout.

Piped-in gases, computer lines, and electrical systems

Vacuum for suction, anesthetic gas evacuation, compressed air, oxygen, and nitrous oxide may be piped into the OR. The outlets may be located on the wall or suspended from the ceiling in either a fixed rotating boom or a retractable column. The anesthesia provider needs at least two outlets for oxygen and suction and one for nitrous oxide. To protect other rooms, the supply of oxygen and nitrous oxide to any room can be shut off at control panels in the corridor should trouble occur in a particular line. A panel light comes on, and a buzzer sounds in the room and in the maintenance department. The buzzer can be turned off, but the panel light stays on until the problem is corrected. The buzzer should be tested on a routine schedule.

Computer lines for monitors or personal computers (PCs) are commonly located adjacent to the anesthesia machine and the circulating nurse’s writing desk. Additional lines may be attached to computers used in specialties such as neurosurgery, which uses immediate computed tomography (CT) scanning images during the intraoperative care period. Care is taken not to use the keyboard with soiled hands or soiled examination gloves. The keyboard should be of a design that permits adequate cleaning between patients. Seamless touch keypads or keyboard covers are easiest to maintain and clean.

Electrical outlets are grounded and must meet the requirements of the equipment that will be used. Some machines require 220-V power lines; others operate on 110 V. Permanently mounted fixtures, such as a clock and x-ray view boxes, can be recessed into walls and wired in rather than plugged into outlets. Electrical cords that extend down the wall or across the floor are hazardous. Ceiling-mounted booms are strategically placed for bringing piped-in gases, vacuum lines, and electrical outlets close to the operating bed. They eliminate the hazard of tripping over cords.

Multiple electrical outlets should be available from separate circuits. This minimizes the possibility of a blown fuse or a faulty circuit shutting off all electricity at a critical moment. All personnel must be aware that the use of electricity introduces the hazards of electric shock, power failure, and fire. Faulty electrical equipment may cause a short circuit or the electrocution of patients or personnel. These hazards can be prevented by taking the following precautions:

1. Use only electrical equipment designed and approved for use in the OR. Equipment must have cords of adequate length and adequate current-carrying capacity to avoid overloading.

2. Test portable equipment immediately before use.

3. Discontinue use immediately if any malfunction takes place, and report any faulty electrical equipment.

4. If a ground fault buzzer sounds, unplug the last device engaged and remove it from service.

Fire safety systems are installed throughout the hospital. All personnel must know the fire rules. They must be familiar with the location of the alarm box and the use of fire extinguishers. Additional information concerning OR fires can be found in Chapter 13.

Lighting

General illumination is furnished with static ceiling lights and mobile spotlights. Most room lights are white fluorescent, but they may be incandescent. Lighting should be evenly distributed throughout the room without harsh shadows, especially in the working area of the field. The anesthesia provider must have sufficient light, at least 200 foot-candles, to adequately evaluate the patient’s color. Intraoperatively, the lighting should not cause the organs to appear discolored.

For minimized eye fatigue, the ratio of intensity of general room lighting to that at the surgical site should not exceed 1:5, preferably 1:3. This contrast should be maintained in corridors and scrub areas, and in the room itself, so that the surgeon becomes accustomed to the light before entering the sterile field. Color and hue of the lights also should be consistent.

Illumination of the surgical site depends on the quality of light from an overhead spotlight source and the reflection from the drapes and tissues. Drapes should be blue, green, or gray to avoid eye fatigue. White glistening tissues need less light than dull dark tissues. Light must be of such quality that the pathologic conditions are recognizable. Some lighting systems have video cameras installed that can be connected to monitors for observation by nonsterile personnel outside the field. The view is close to the same field of vision of the surgeon and first assistant.

The overhead operating light must:

• Make an intense light, within a range of 2500 to 12,500 foot-candles (27,000 to 127,000 lux), into the incision without glare on the surface. It must give contrast to the depth and relationship of all anatomic structures. The light may be equipped with an intensity control with a minimum of four brightness levels. The surgeon asks for more light when needed. A reserve light should be available.

Lighting needs differ when endoscopic equipment with video monitors is used. Lower light power is beneficial to the team for decreased eye fatigue.

• Provide a light pattern that has a diameter and focus appropriate for the size of the incision. An optical prism system has a fixed diameter and focus. Other types have adjustable controls mounted on the fixture.

Most fixtures provide focused depth by refracting light to illuminate both the body cavity and the general operating field. The focal point is where illumination is greatest. It should not create a dark center at the surgical site. A 10-inch to 12-inch (25-cm to 30-cm) depth of focus allows the intensity to be relatively equal at both the surface and the depth of the incision.

To avoid glare, a circular field of 20 inches (50 cm) in diameter provides a 2-inch (5-cm) zone of maximum intensity in the center of the field with 20% intensity at the periphery.

• Be shadowless. Multiple light sources and reflectors decrease shadows. In some units, the relationship is fixed; other units have separately maneuverable sources to direct light beams from converging angles. Some manufacturers have incorporated sensors in the spotlight to detect when the first assistant or surgeon’s head is in the beam and threatening to cast a shadow. The lights sense the obstruction and decrease the beam, preventing a shadow over the surgical site.

• Produce the blue-white color of daylight. Color quality of normal or diseased tissues is maintained within a spectral energy range of 3500° K to 6700° K. Most surgeons prefer a color temperature of about 5000° K, which approximates the white light of a cloudless sky at noon.

• Be freely adjustable to any position or angle with either a vertical or a horizontal range of motion. Most overhead operating lights are ceiling-mounted on mobile fixtures. Some have dual lights or dual tracks with sources on each track. These are designed for both lights to be used simultaneously to provide adequate intensity and minimize shadows in a single incision. Many fixtures are adapted so that the surgeon can direct the beam by manipulating sterile handles attached to the lamp or by remote control at the sterile field. Automatic positioning facilitates adjustment, and braking mechanisms prevent drift (i.e., a movement away from the desired position).

Fixtures should be manipulated as little as possible to minimize dispersion of dust over the sterile field. For the best illumination in the shortest time, the first spotlight should be positioned at the surgical site, followed by the second. Ideally, the light can be maneuvered in a 360-degree rotation as needed, quickly and without effort. Smaller lights commonly are restricted because of wiring bundles.

• Produce a minimum of heat to prevent injuring and drying exposed tissues. Most overhead lights dissipate heat into the room, where it is cooled by the air-conditioning system. Halogen bulbs generate more light and heat than do other types but do not last as long. The average halogen bulb lasts 1000 hours. The risk of fire from a halogen bulb is significant, and the hot bulb should not be permitted to come in contact with any flammable material or a person’s skin.

Lamps should produce less than 25,000 mW/cm2 of radiant energy. If multiple light sources are used, collectively they must not exceed this limit at a single site. Beyond this range, the radiant energy produced by infrared rays changes to heat at or near the surface of exposed tissues. A filter globe absorbs some infrared and heat waves over the light bulb or with an infrared cylindric absorption filter of a prism optical system. Nonfiltered lights, particularly halogen, can burn tissue from a distance.

• Be easily cleaned and maintained. Tracks recessed within the ceiling virtually eliminate dust accumulation. Suspension-mounted tracks or a centrally mounted fixture must have smooth surfaces that are easily accessible for cleaning. Light bulbs should have a reasonably long life. Light-emitting diode (LED) lights are semiconductors. LED lights last longer than halogen bulbs and do not generate heat.9 The average LED light lasts 20,000 hours, and more advanced LED lights last 40,000 hours.

Changing the bulb should not require additional tools because time may be an issue in a critical part of a surgical procedure. The bulb is usually too hot to touch with the bare hand. Many styles are available that contain several bulbs that provide backup light when one bulb burns out.

A supplemental surgical task light may be needed for a secondary surgical site, such as for the legs or arms during conduit procurement for cardiovascular procedures. Some hospitals have portable explosion-proof lights. These lights should have a wide base and should be tip-proof. Others have satellite units that are part of the overhead lighting fixture. These should be used only for secondary sites unless the manufacturer states that the additional intensity is within safe radiant energy levels when used in conjunction with the main light source. The use of multiple teams in complex multidisciplinary procedures requires adequate lighting for each operating surgeon.

A source of light from a circuit separate from the usual supply must be available for use in case of power failure. This may require a separate emergency spotlight. It is best if the operating light is equipped so that an automatic switch can be made to the emergency source of lighting when the usual power fails. Flashlights with fresh batteries should always be immediately available.

Some surgeons prefer to work in a darkened room with only indirect illumination off the surgical site during minimally invasive procedures. This is particularly true of surgeons working with endoscopic instruments and the operating microscope. If the room has windows to the hall or substerile room, lightproof shades may be drawn to darken the room when this equipment is in use. Because of the hazard of dust fallout from shades, the windows may have blinds contained between two panes of glass with a handle to open or close the louvers in rooms where this equipment is routinely used.

Although the surgeon may prefer the room darkened, the circulating nurse or anesthesia provider must be able to see adequately to observe the patient’s color and to monitor the patient’s condition. One spotlight can be aimed away from the field in the direction of the anesthesia provider. In some circumstances, the x-ray view box can be turned on for additional illumination.

Some surgeons wear an adjustable headlight designed to focus a light beam on a specific area, usually in a recessed body cavity such as the nasopharynx. Fiberoptic headlights produce a cool light and reduce shadows. Both the surgeon and first assistant may wear a headlight. Alternatively, a light source that is an integral part of a sterile instrument, such as a lighted retractor or fiberoptic cable, may be used to illuminate deep cavities or tissues difficult to see with only the overhead operating light. Fiberoptic cables should not be permitted to become detached from the instrument and shine directly on the drape for a prolonged period because a fire may ignite.

Monitoring screens

Monitors and computers are designed to keep the OR team aware of the physiologic functions of the patient throughout the surgical procedure and to record patient data. The anesthesia provider or a perioperative nurse uses monitoring devices as an added means to ensure safety for the patient during the surgical procedure.

The screens may be built into portable carts or attached to articulated arms or ceiling booms. They may be plasma or liquid crystal display (LCD) and measure 20 to 22 inches, and in some facilities up to 42 inches, in size. Plasma screens are heavier and do not last as long as LCD versions. Newer screens with surface-conduction electron emitter displays (SEDs) will likely replace LCD and plasma screens in the future.9

More commonly, video monitors serve a number of useful purposes for the surgeon within the OR. They are widely used for teaching surgical techniques. This minimizes the number of visitors in the OR, which, in the interest of sterile technique, is advantageous. In addition, monitors provide a better view for more people to see the surgical procedure from a remote area or through a microscope or endoscope. They can also be used for record keeping and documentation for legal purposes for the surgeon. Video recording is possible for this purpose. If video recording is done while patients are in the rooms, each patient should have the opportunity to sign a permission form.

As an aid to diagnosis, an audiovisual hookup between the OR and the radiology department permits x-rays to be viewed on the television screen in the OR without having to be transported into the OR and mounted on view boxes. With such a hookup, the surgeon gains the advantage of remote interpretive consultation when it is desired.

A two-way audiovisual system between the pathology laboratory and the OR enables the surgeon to examine the microscopic slide by video in consultation with the pathologist without leaving the operating bed. The pathologist can view the site of the pathologic lesion without entering the OR.

Radiograph screens or view boxes

Many facilities have changed from plain film viewing to digital computer monitors. The monitors may be on articulated arms that extend from the wall or ceiling. In this circumstance, lighted view boxes are still useful in the event old films are brought from the archives for comparison with the patient’s new digital images. The view boxes can also be used as indirect lighting during low-light procedures.

X-ray view boxes can be recessed into the wall. The viewing surface should accommodate a minimum of four standard-size films. The best location is in the line of vision of the surgeon standing at the operating bed. An additional view box should be located near the anesthesia provider for review of chest films. It can also provide indirect illumination of the anesthesia machine or instrument table during procedures that require a darkened room. Lights for view boxes should be of high intensity. A film-holding basket should be planned within reach of each view box station.

Clocks

Two clocks should be in each OR. A standard clock, analog or digital, for basic time observation should be visible from the field. A time-elapsed clock, which incorporates a warning signal, is useful for indicating that one or more predetermined periods of time have passed. This may be used during surgical procedures for total arterial occlusion, with use of perfusion techniques or a pneumatic tourniquet, or during cardiac arrest. Start, stop, and reset buttons should be within reach of the anesthesia provider and the circulating nurse.

Cabinets or carts

Each OR may be supplied with closed-in stationary cabinetry unless a cart system or pass-through entry is used. Supplies for the types of surgical procedures done in that room are stocked, or every OR may be stocked with a standard number and type of supplies. Having these basic supplies saves steps for the circulating nurse and helps eliminate traffic in and out of the OR. Glass shelves and sliding doors provide ease in finding and removing items.

Many cabinets are made of stainless steel or hard plastic. Wire shelving minimizes dust accumulation. Cabinets should be easy to clean. One cabinet in the room may have a pegboard at the back to hang items, such as table appliances. Gloves used in patient care should be removed when opening the cabinet and removing supplies.

Pass-through cabinets that circulate clean air through them while maintaining positive air room pressure allow transfer of supplies from outside the OR to inside it. They help ensure the rotation of supplies in storage or can be used only for passing supplies as needed from a clean center core. Some pass-through cabinets between the OR and a corridor accommodate supply carts directly from the sterile core, which are easily removable for restocking.

In lieu of or as an adjunct to cabinets, some hospitals stock carts with special sutures, instruments, drugs, and other items for some or all of the surgical specialties. The appropriate cart is brought to the room for a specific surgical procedure.

Furniture and other equipment

Stainless steel furniture is plain, durable, and easily cleaned. Each OR is equipped with the following basic items:

• Operating bed with a mattress covered with an impervious surface, foam or gel construction, attachments for positioning the patient, and armboards.

• Instrument tables. These are commonly called back tables, although they are actually at the side of the scrub person during the surgical procedure. Some rooms use over-bed tables such as Phalen or Mayfield style.

• Mayo stand. The Mayo stand is a frame with a removable rectangular stainless steel tray. The footplate of the frame slides under the operating bed and the support that holds the tray positions over the sterile field. The Mayo tray is supplied with immediate need instruments and supplies. The height is adjustable.

• Small tables for gowns and gloves and the patient’s skin preparation equipment and catheterization supplies.

• Ring stand for basins. This is optional because most ORs do not use splash basins.

• Anesthesia machine and table for anesthesia provider’s equipment.

• Sitting stools and standing platforms that safely stack to give additional height to the user.

• IV poles for IV solution bags. The anesthesia provider may clip the upper drapes to the IV poles.

• Suction canisters, preferably portable on a wheeled base.

• Kick buckets in wheeled bases. Commonly called sponge buckets.

• Wastebasket near the circulating nurse’s writing surface, biohazard red trash bins, and clean trash bins.

• Writing surface. This may be a wall-mounted stainless steel desk or an area built into a cabinet for the circulating nurse to document in the records.

• Computer station. This may be permanently affixed to a hardwired station or mobile wireless. The keyboard should be positioned so the circulating nurse can observe the sterile field. A scanning device may be incorporated for bar-coded drugs and supplies.

Communication systems

A communication system is a vital link to summon routine or emergency assistance or to relay information to and from the OR team. Many surgical suites are equipped with telephones, intercoms, call lights, video equipment, and computers. These communication systems may connect the OR with the clerk-receptionist’s desk, the nurse manager’s office, the holding area, the family waiting room, the PACU, the pathology and radiology departments, the blood bank, and the sterile processing department. These systems make instantaneous consultation possible through direct communication.

Voice intercommunication system

Telephone and intercom systems are useful for the OR team to communicate with the control desk. Sounds are distorted to the patient in early stages of general anesthesia. Incoming calls over an intercom should not be permitted to disturb the patient at this time. Also, an awake patient should not overhear information about a pathologic diagnosis (e.g., from a voice coming through an intercom speaker box after a biopsy has been performed). Installation of any type of intercom equipment either in the adjacent substerile room or scrub area rather than in the OR helps eliminate sounds that could disturb both the patient and the surgeon.

Call-light system

This system is used to summon assistance from the anesthesia staff, pathologist, patient care staff, and housekeeping personnel. It is activated in the OR with a hand-operated switch; a light alerts personnel at a central point in the suite or displays at several receiving points simultaneously.

Closed-circuit television

Television surveillance is an easy way for the nurse manager to keep abreast of activities in each OR. By means of a video camera with a wide-angle lens mounted high in the corner of each OR, managers may make rounds simply by switching from one room to another by pushing buttons at their desk and viewing a monitor in the office. Signs should be posted to indicate that video surveillance is in process. The patient should be made aware that video surveillance is in process.

Computers

A computer in each OR affords access to EMR information and allows data input by the circulating nurse. The types of hardware and software programs available dictate the capabilities of the automated information system. A keyboard, light pen, or bar-code scanner may be used for input. The computer processes and stores information for retrieval on the viewing monitor and by printout from a central processing unit.

The computer system should be wireless for fast transmission of data and should require a password for each user in the system for security. The staff should be encouraged to logon and logoff, but the system has idle time parameters so, if inactive for a period of time, the system automatically logs off the user. Failed password attempts lock out the user for a designated period of time or may require the system administrator to assign a new password.

The computer database and electronic health record (EHR) help the circulating nurse obtain and enter information that may include the following:

• Schedule, including the patient’s name, surgeon, procedure, special or unusual equipment requirements, wound classification, and whether procedure is elective, urgent, or emergency

• Patient EHR, preoperative patient assessment data, nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes, and plan of care

• Results of laboratory and diagnostic tests

• Surgeon’s preference card with capability to update

• Inventory of supplies and equipment provided and used

• Charges for direct patient billing

• Intraoperative nursing interventions

• Timing parameters, including anesthesia, procedure, and room turnover

The computer terminal may be mounted on the wall or placed on a shelf or a portable table or cart. The computer keyboard should be wireless so it can be moved and the circulating nurse can see the patient and the activities of the OR team while electronically documenting intraoperative information into the record. The computerized patient information that is generated in the OR may interface with the hospital-wide computer system.

Caution: The printer should not be located in direct patient care areas. Printers use toner powder that can become airborne in the OR and cause contamination. According to the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for printer toner the primary routes of entry of toner powder are via direct contact and inhalation.c Chronic lung exposure can cause irritation and lung fibrosis. Toner is combustible, and the powder has explosive qualities. It should be kept away from heat and flame. Protective goggles, gloves, and mask should be worn if toner spills. A HEPA filter should be used if vacuuming the material. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has not set permissible exposure limits (PEL) at this time.

Special procedure rooms

Certain procedures or outpatient treatments may indicate the need for rooms designed for a specific purpose, such as interventional radiology, endoscopy, or cystoscopy. These rooms are designed with equipment for performing the specific interventional procedures, including specialized radiologic and monitoring devices. An interventional radiologist, cardiologist, and several endoscopists should be consulted when planning these types of facilities.

Interventional radiography room

Endovascular stenting, balloon angioplasty, cardiac catheterization, and other interventions that require fluoroscopy can be performed in a room with fixed x-ray equipment and specialized radiographic beds (Fig. 10-12). The endovascular instrument table may be double the average length because the aortic guidewires and deployment devices are extremely long. Proximity to the OR is important in case of an emergency that necessitates an open procedure. Many interventional rooms have doors that open into the semirestricted area of the surgical services department. Some interventional rooms double as minimally invasive rooms.

Cardiac catheterization (angioplasty and stenting) may be performed within the surgical suite in a room equipped for fluoroscopy. Imaging screens are located near the head of the operating bed or on articulated arms directly across the OR bed to allow the surgeon and the team to visualize the coronary arteries during the procedure. Monitors, suction, oxygen, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation equipment are available in this room for each cardiac catheterization procedure. The team must be alert for emergency situations, such as a perforated coronary artery, and be prepared for an emergency thoracotomy or transfer to an OR for an open procedure.

Minimally invasive surgery room

Some rooms are equipped specifically for laparoscopic procedures, with ceiling booms in four quadrants of the room for endoscopic light sources, camera boxes, insufflators, electrosurgical generators, and video monitors. A dedicated MIS room has all the equipment for puncture and nonpuncture endoscopy located on a large cart or a ceiling-mounted boom. The use of booms in these rooms helps minimize the amount of equipment spread around the room.

Several video monitors are located around the room on articulated arms or on the booms for ergonomic viewing of the surgical field by the surgical team. These rooms should have the capability of immediately converting to an open procedure in the event of an untoward event such as arterial or organ puncture.

Endoscopy room

Many surgical suites have a designated class A size room in which nonpuncture flexible or rigid endoscopic procedures, such as bronchoscopy, gastroscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy, are performed. Most are equipped for the use of lasers and electrosurgery. Some endoscopy rooms have x-ray and video capabilities. Equipment for nonpuncture endoscopy is usually affixed to mobile carts so they can easily be transported to a regular OR for intraoperative bronchoscopy, gastroscopy, or colonoscopy added to a major surgical procedure.

Cystoscopy room

A cystoscopy room (cysto room) may be available for a urologic examination or procedure. Ideally, the room should be a class A or class B size located in the restricted area of the OR. Waste fluids are collected in special canisters and are disposed of like other biologically contaminated fluids. Older cystoscopy rooms may be equipped with special floor drains for the disposal of fluids during the procedure. The drain cover must be removable for cleaning. Modern styles have eliminated this drain for infection control reasons.

A cysto room is also equipped with x-ray and fluoroscopy machines because many procedures require the use of intravenous or ureteral contrast media to visualize the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. Radiographic digital screens should be adjacent to the OR bed, and view boxes should accommodate a minimum of four still films simultaneously. Imaging screens are located in the room, either free-standing or mounted on articulated arms, to allow the urologist to visualize the urologic structures during fluoroscopy. Some urologists use ultrasonic equipment, lasers, and electrosurgery to perform minimally invasive procedures.

A portable cysto cart should be available for dispatch from the cysto room when a procedure in the main OR requires placement of ureteral catheters, stents, or a cystoscopic examination. The cart should be equipped with a light source, sterile camera, video monitor, sterile cystoscopes (0 and 30 degrees) and light cord, bridges and sheaths, an assortment of ureteral catheters in pairs, Foley catheters, urinary drainage bags, and lubricant.

Cesarean delivery room

Most facilities that have obstetric departments have a self-contained OR within the delivery suite (Fig. 10-13). This room is a restricted room with an attached substerile room and scrub sink area. The purpose of this room is to provide equipment and supplies in support of a surgical birth of the baby through the mother’s abdomen (cesarean section) instead of a vaginal birth.

A few differences of the cesarean delivery room include resuscitation supplies and equipment for the newborn and a specialized warming bed that can be used to transport the baby to the special care nursery.

Construction or renovation of the surgical suite

Considerations for planning and design

The planning and design of the new perioperative environment generally entails both renovation and new construction.5,6,9,10 Most facilities cannot shut down for the construction process and must continue with patient care services. Adequate planning and projection of needs during the process take some of the stress out of running the department around construction obstacles.

The AIA Guidelines require a preconstruction risk analysis in a consultative format. The Infection Control Risk Assessment (ICRA) is determined with all parties offering multidisciplinary input about features such as water temperature between 105° F and 120° F, electric safety, ventilation air changes, and containing potential contamination. Box 10-1 describes additional preconstruction assessment factors to consider.

Goals to strive for include: (1) timing of construction phases; (2) precision of work done; and (3) staying within the budget. Generating a concurrent plan for maintaining patient flow and expanding/renovating the department requires a multidisciplinary team, which may include the following members5,6,10:

• Department director, nurse manager, and senior perioperative nursing personnel

• Physicians (surgeon, anesthesiologist, pathologist)

• Infection control, risk management, and environmental services personnel

• Maintenance and biomedical personnel

• Project manager (may be in-house personnel or a consultant), architect, equipment vendor, and purchasing personnel; a collaboration between the architect and equipment vendor can generate three-dimensional drawings that can offer a preview of the area

• Communications and information technology personnel (e.g., computers, telephone, intercom, emergency call)

• Support services (e.g., laboratory, radiology, pharmacy) personnel

No one particular construction or renovation plan suits all hospitals or surgical centers; each plan is individually designed to meet projected specific future needs. Visiting other hospitals where building and reconstruction have taken place is beneficial. Ask about the good and bad points.

The number of ORs, storage areas, and immediate perioperative patient care areas required depends on the following:

• Number, type, and length of the surgical procedures to be performed. This determines the class of OR size to build.

• Type and distribution by specialties of the surgical staff and equipment for each. Some specialties may use the same room most of the time and use mounted equipment such as booms, microscopes, imaging equipment, and endoscopy.

• Proportion of elective inpatient and emergency surgical procedures to ambulatory patient and minimally invasive procedures.

• Scheduling policies related to the number of hours per day and days per week the suite will be in use and staffing needs.

• Systems and procedures established for the efficient flow of patients, personnel, and supplies.

• Consideration of volume changes and need for future expansion capabilities.

• Technology to be implemented and plans for potential technology to be developed.

• Safety of staff, patients, and other personnel during construction or renovation.

Principles in construction or renovation planning