Sutures, Needles, and Instruments

Jim McCarthy

Sutures, needles, and instruments are the tools of the surgical team that are necessary to successfully complete a surgical procedure. It is the responsibility of the perioperative nurse to understand these tools and be proficient with their preparation for surgery. Although there are many other aspects of the perioperative registered nurse (RN) role that ensures the expected outcome of a surgical intervention, these items are the basis for surgical procedures. This chapter describes and illustrates a basic knowledge for the perioperative RN, but as the surgical arena continues to evolve, especially technologically, the perioperative RN should be receptive to change and develop proficiencies in new surgical devices and techniques.

Suture Materials

The development of surgical sutures has been closely associated with the development of the art and science of surgery. Medical writings of ancient Egyptian and Assyrian cultures dating back to 2000 BC mention the various materials used, to a limited extent, for suturing and ligating. The concept of suturing and ligating also is recorded in the writings of the father of medicine, Hippocrates, born 460 BC. Gut of sheep intestines was first mentioned as suture material by the ancient Greek physician Galen. The Persian physician and philosopher Rhazes is credited with using surgical gut, or catgut, in AD 900 for suturing abdominal wounds. However, the word catgut is a misnomer, and its use is inappropriate. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it refers to the Dutch word kattedarm, “cat-intestine.” Use of the term catgut was adopted by the English around 1560 to 1600 under obscure conditions, possibly connected humorously with caterwauling.

Suture is a generic term for all materials used to repair and reapproximate incised or torn tissues. The primary goal is to encourage wound healing of the injured tissue to reduce the risk of infection. To suture is to stitch together cut or torn edges of tissue (Mosby's Dictionary, 2012). A ligature is a strand of suture material used to tie off or occlude blood vessels to prevent bleeding, or to isolate a mass of tissue for excision. A variety of suture materials are available for ligating, suturing, and closing the wound. The choice of suture takes into consideration several characteristics, such as the following: absorbable versus nonabsorbable, tensile strength, monofilament or multifilament (braided), ease of knot tying, and the inflammatory response of the tissue. An understanding of the characteristics of suture materials, knowledge of the risk factors of wound healing, and awareness of the interactions between tissues and suture materials for proper wound healing is essential for the perioperative nurse, as well as all members of the surgical team.

Characteristics of Suture Material

Key features used to evaluate the general properties of suture material are (1) physical characteristics, (2) handling characteristics, and (3) tissue-reaction characteristics (Box 7-1).

The ideal suture material is one that causes minimal inflammation and tissue reaction while providing maximal strength during the lag phase of wound healing (see Chapter 9). There is no ideal suture for every application, and even the best application presents risks of individual suture failure. Perioperative nurses should evaluate the characteristics of sutures to determine the ideal choice for surgical patient care and incorporate research findings into their clinical practice.

Physical Characteristics.

Physical characteristics of sutures are defined and described by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), which is the official compendium for suture manufacture. Characteristics can be measured or visually determined and include the following properties:

• Physical configuration: Suture material can be single-strand (monofilament) or multistrand (multifilament), containing numerous fibers rendered into a single thread by twisting or braiding (Figure 7-1).

• Capillarity: The ability to transmit fluid along the strand.

• Diameter (size): Size is measured in millimeters, and expressed in USP sizes with zeros. That is, the smaller the cross-sectional diameter, the more zeros; sizes range from #7, the largest, to 11-0, the smallest. Suture sizes 0 to 4-0 are the most commonly used in general surgery. (The surgeon usually selects the finest suture possible for the tissue being closed. The finer diameter [smaller size] provides better handling qualities and small knots. Improved suturing techniques are possible with sutures of finer diameter.)

• Tensile strength: The amount of weight (breaking load) necessary to break a suture (breaking strength); it varies according to the type of suture material (Table 7-1)

• Knot strength: The force necessary to cause a given type of knot to slip, either partially or completely

• Elasticity: The suture's inherent ability to regain original form and length after having been stretched

• Memory: The capacity of a suture to return to its former shape after being re-formed, as when tied; high memory yields less knot security

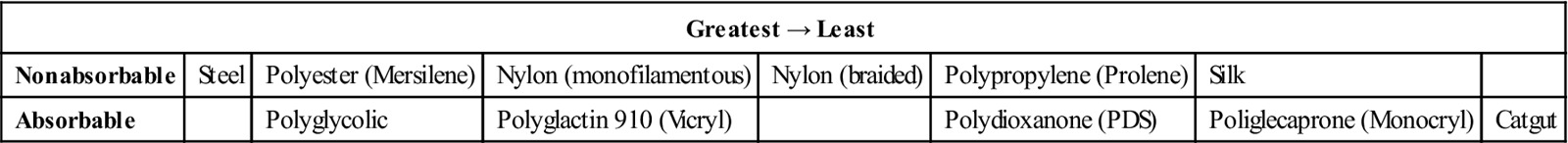

TABLE 7-1

Relative Straight-Pull Tensile Strength of Suture Materials

| Greatest → Least | |||||||

| Nonabsorbable | Steel | Polyester (Mersilene) | Nylon (monofilamentous) | Nylon (braided) | Polypropylene (Prolene) | Silk | |

| Absorbable | Polyglycolic | Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) | Polydioxanone (PDS) | Poliglecaprone (Monocryl) | Catgut | ||

Modified from Ethicon wound closure manual, available at http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/surgery/education/resident_info/supplement/suture_manuals/ethicon_wound_closure_manual.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2013.

Handling Characteristics.

Handling characteristics of suture material are related to pliability (e.g., how easily the material bends) and the coefficient of friction (e.g., how easily the suture slips through tissue and can be tied). A suture with a high friction coefficient tends to drag through tissue. It is more difficult to tie because its knots do not set easily. Some suture materials are coated to reduce their coefficient of friction. This coating not only improves the way they pull through tissue on insertion but also lessens the force needed to remove the suture after the wound is healed. The coefficient of friction should not be too low, however, because then knots will be loosened too easily.

Tissue-Reaction Characteristics.

Because it is a foreign substance, all suture materials cause some tissue reaction. Tissue reaction begins when the suture inflicts injury to the tissue during insertion. In addition, tissue reacts to the suture material itself (Table 7-2). This reaction begins with an infiltration of white blood cells into the area; macrophages and fibroblasts then appear; and by about the seventh day, fibrous tissue with chronic inflammation is present. The reaction persists until the suture is encapsulated (nonabsorbable material) or absorbed (absorbable material) by the body.

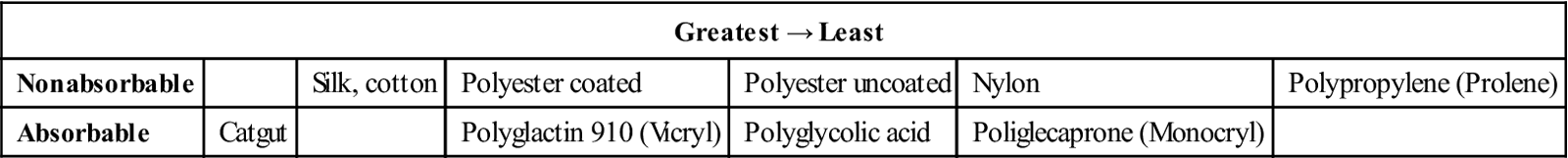

TABLE 7-2

Relative Tissue Reactivity to Sutures

| Greatest → Least | ||||||

| Nonabsorbable | Silk, cotton | Polyester coated | Polyester uncoated | Nylon | Polypropylene (Prolene) | |

| Absorbable | Catgut | Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) | Polyglycolic acid | Poliglecaprone (Monocryl) | ||

Modified from Ethicon wound closure manual, available at http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/surgery/education/resident_info/supplement/suture_manuals/ethicon_wound_closure_manual.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2013.

Types of Suture Material

Suture materials are classified into two main groups: absorbable and nonabsorbable. The suture may then be divided into two subgroups: braided and monofilament. Absorbable sutures have varying lengths of absorption time, which affects healing time and strength of the closure.

Absorbable Sutures.

The USP defines an absorbable surgical suture as “sterile, flexible strand prepared from collagen derived from healthy mammals, or from a synthetic polymer….” It is capable of being absorbed by living mammalian tissue but may be treated to modify its resistance to absorption. It may be modified with respect to body or texture. It may be impregnated with a suitable coating, softening, or antimicrobial agent. It may be colored by a color additive approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Absorbable sutures can be digested (by enzyme activity) or hydrolyzed (broken down by reaction with water in tissue fluids) and assimilated by the tissues during the healing process. Absorbable sutures vary in treatment, color, size, packaging, and resistance to absorption, according to their purpose. Types of absorbable suture include plain or chromic surgical gut, collagen, and glycolic acid polymers (Table 7-3).

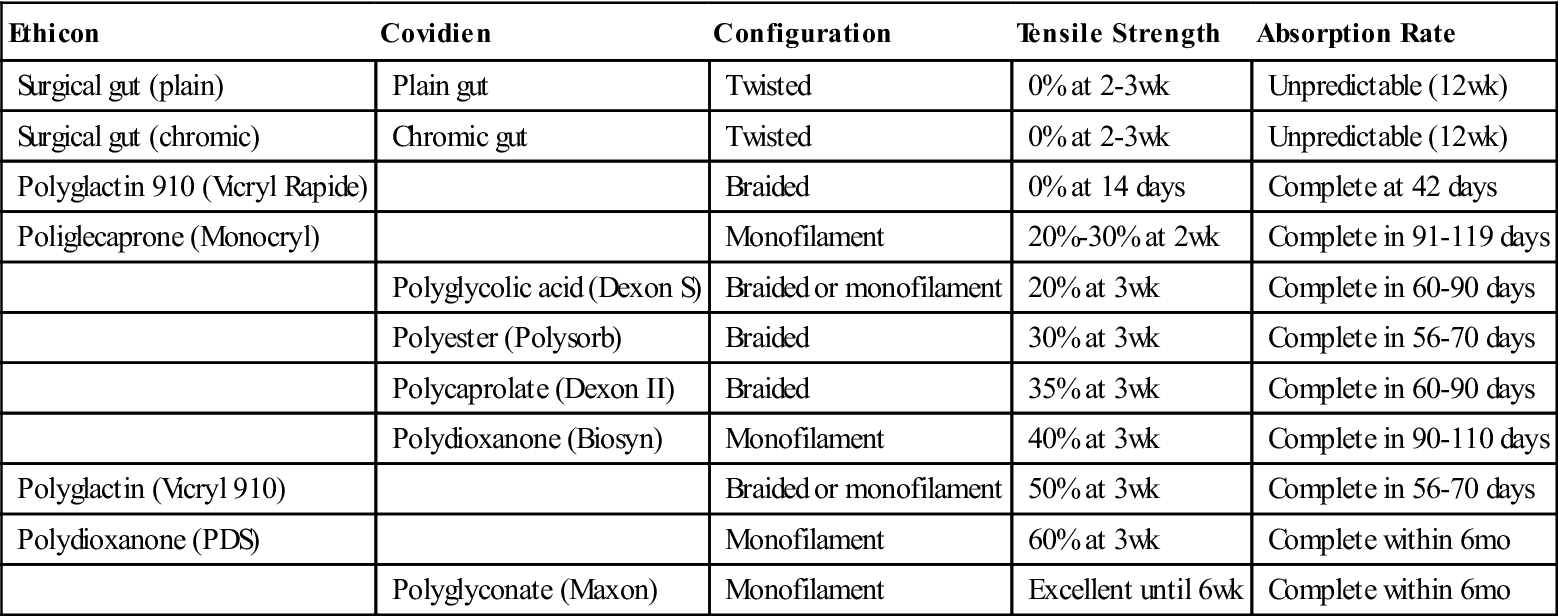

TABLE 7-3

Comparison of Absorbable Sutures

| Ethicon | Covidien | Configuration | Tensile Strength | Absorption Rate |

| Surgical gut (plain) | Plain gut | Twisted | 0% at 2-3 wk | Unpredictable (12 wk) |

| Surgical gut (chromic) | Chromic gut | Twisted | 0% at 2-3 wk | Unpredictable (12 wk) |

| Polyglactin 910 (Vicryl Rapide) | Braided | 0% at 14 days | Complete at 42 days | |

| Poliglecaprone (Monocryl) | Monofilament | 20%-30% at 2 wk | Complete in 91-119 days | |

| Polyglycolic acid (Dexon S) | Braided or monofilament | 20% at 3 wk | Complete in 60-90 days | |

| Polyester (Polysorb) | Braided | 30% at 3 wk | Complete in 56-70 days | |

| Polycaprolate (Dexon II) | Braided | 35% at 3 wk | Complete in 60-90 days | |

| Polydioxanone (Biosyn) | Monofilament | 40% at 3 wk | Complete in 90-110 days | |

| Polyglactin (Vicryl 910) | Braided or monofilament | 50% at 3 wk | Complete in 56-70 days | |

| Polydioxanone (PDS) | Monofilament | 60% at 3 wk | Complete within 6 mo | |

| Polyglyconate (Maxon) | Monofilament | Excellent until 6 wk | Complete within 6 mo |

Modified from Ethicon wound closure manual, available at http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/surgery/education/resident_info/supplement/suture_manuals/ethicon_wound_closure_manual.pdf. Accessed, March 10 2013; Covidien suture catalog, available at www.covidien.com/campaigns/pagebuilder.aspx?topicID=181589&page=SPC:Main. Accessed March 10, 2013.

Surgical Gut.

Surgical gut is obtained from the collagen of the submucosal layer of the small intestine of sheep or the intestinal serosa of cattle or hogs. The processed strands or ribbons of collagen are either untreated (plain, type A) or treated with chromium salts (chromic, type C).

Chromatization delays absorption of the suture in living mammalian tissue. The strength of the chromium salt content and the duration of the chromatizing process are accurately controlled and tested. Proper chromatizing of gut ensures the integrity of the suture and maintenance of its strength during the early stages of wound healing. It enables a wound with slow healing power to heal sufficiently before the suture is entirely absorbed.

The elaborate processes of mechanical and chemical cleaning of the raw gut are followed by sterilization, usually with ionizing radiation, and storage in hermetically sealed packages. Modern manufacturing processes also ensure tensile strength, more controlled absorption, and more predictable results.

Absorption occurs by digestion of the gut by tissue enzymes. The absorption rate of surgical gut is influenced by the type of body tissue it contacts and, to some extent, by the patient's general physical condition. Studies also show that surgical gut is absorbed faster in serous or mucous membranes than in muscular tissues. When fine chromic gut is properly buried in successive layers of the gastrointestinal tract, it retains its strength long enough for primary union to take place.

Surgical gut suture is wet-packaged in an alcohol solution to provide maximal pliability and should be used immediately after removal from the packet. When a gut suture is removed from its packet and is not used at once, the alcohol evaporates, which causes the strand to lose its pliability. If required, the strand's pliability may be restored just before use by immersing it in sterile water or normal saline solution, preferably at body temperature, for only a few seconds. This immersion is recommended only for eye sutures; in other areas, tissue fluids moisten the gut sufficiently as it passes through the tissue when the surgeon sews. Excessive moisture reduces tensile strength.

Collagen Sutures.

Collagen sutures are derived from cattle tendons. They are chemically treated to remove noncollagenous material, purified, and processed into strands that have physical properties superior to those of surgical gut. Collagen suture is used most often as a fine suture material for the eye.

Synthetic Absorbable Sutures.

To produce synthetic absorbable sutures, specific polymers are extruded into suture strands. The base material for synthetic absorbable sutures is a combination of lactic acid and glycolic acid polymers (Vicryl, Dexon, and Polysorb). The molecular structure of these products has a tensile strength sufficient for approximation of tissues for 2 to 3 weeks, followed by rapid absorption.

Other synthetic polymers (PDS, Maxon, and Monocryl) provide wound support for longer periods (3 months). They are used when prolonged support for wound healing is desired, as with fascial closure or for elderly or oncology patients. They combine the desirable qualities of extended wound support and eventual absorbability.

An additional type of synthetic absorbable suture approved by the FDA is MonoMax. Recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) technology is used to produce this poly-4-hydroxybutyrate suture. This suture has a high degree of flexibility and maneuverability, but may have limitations for use in patients who are allergic to the cells or the growth medium used for its production. The suture is not indicated for use in cardiovascular or neurologic tissues or for microsurgery or ophthalmic surgery. It has been used in laparotomy closure (Research Highlight).

Synthetic absorbable sutures are absorbed by slow hydrolysis in the presence of tissue fluids. Hydrolysis is the chemical process whereby the polymer reacts with water to cause an alteration of breakdown of the molecular structure. These sutures are degraded in tissue by this process at a more predictable rate than surgical gut (or collagen) and with less tissue reaction. These sutures are dry-packaged in sizes 10-0 to #3. They should not be dipped in solutions because moisture reduces their tensile strength. Some polymers have additional coatings to reduce drag in tissue.

Nonabsorbable Sutures.

Nonabsorbable sutures are strands of material that effectively resist enzymatic digestion in living animal tissue. The USP classifies nonabsorbable surgical suture as follows:

• Class I suture is composed of silk or synthetic fibers of monofilament, with a twisted or braided construction.

• Class II suture is composed of cotton or linen fibers or coated natural or synthetic fibers, in which the coating significantly affects thickness but does not contribute significantly to strength.

• Class III suture is composed of monofilament or multifilament metal wire.

The strand of suture material may be uncoated or coated with a substance to reduce capillarity and friction when passing through the tissue. Several products are used for coating, including silicone, polytef (Teflon), and various polymers. Fibers may be uncolored, naturally colored, or impregnated with a suitable dye.

Nonabsorbable suture material is encapsulated or walled off by the tissues around it during the process of wound healing. Skin sutures, for which nonabsorbable materials are often the choice, are removed before healing is complete. The most common nonabsorbable suture materials are silk, nylon, polyester fiber, polypropylene, and stainless steel wire (Table 7-4).

TABLE 7-4

Comparison of Nonabsorbable Suture

| Sutures | Materials | Construction |

| Pronova Poly | Polymer blend of poly (vinylidene fluoride) and poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropolypropylene) | Monofilament |

| Ethibond Excel polyester | Polyester/Dacron | Braided |

| Mersilene polyester suture | Polyester/Dacron | Braided |

| Ethilon nylon suture | Nylon 6 | Monofilament |

| Nurolon suture | Nylon 6 | Braided |

| Permahand silk suture | Silk | Braided |

| Prolene polypropylene suture | Polypropylene | Monofilament |

| Surgical stainless steel suture | 316L stainless steel | Monofilament |

| Vascufil | Butylenes terephthalate and polyteramethylene ether glycol | Monofilament |

| TiCron | Polyethylene terephthalate | Braided |

| Monosof Dermalon |

Nylon 6 and nylon 6.6 | Monofilament |

| Surgilon | Nylon 6.6 | Braided |

| Silk | Silk | Braided |

| Surgipro II Surgipro |

Polypropylene | Monofilament |

| Steel | 316L stainless steel | Stainless steel |

Modified from Ethicon product catalog, suture/adhesives, drains, hernia repair, 2009, available at www.akinglobal.com.tr/medikal/tr/dokumanlar/JHONSON&JHONSON/SUTURES.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2013; Covidien suture catalog 2013, available at www.covidien.com/campaigns/pagebuilder.aspx?topicID=181589&page=SPC:Main. Accessed March 10, 2013.

Silk.

Silk is prepared from thread spun by the silkworm larva while making its cocoon. Top-grade raw silk is (1) processed to remove natural waxes and gum, (2) manufactured into threads, and (3) colored with a vegetable dye. The strands of silk are twisted or braided to form the suture, which gives it high tensile strength and better handling qualities. Silk handles well, is soft, and forms secure knots.

Because of the capillarity of untreated silk, body fluid may transmit infection along the length of the suture strand. For this reason surgical silk is treated to eliminate its capillarity properties (able to resist the absorption of body fluids and moisture). It is available in sizes 9-0 to #5, in sterile packets or precut lengths, and with or without attached needles. Silk should be kept dry. Wet silk loses 20% of its original strength. Silk is not a true nonabsorbable material. When buried in tissue, it loses its tensile strength after about 1 year and may disappear after several years.

Cotton.

Surgical cotton sutures are made from individual cotton fibers that are combed, aligned, and twisted to form a finished strand. Because new types of fibers have been introduced, cotton suture is rarely used. Some companies no longer manufacture it.

Umbilical tape, although not used for suturing, is produced by suture manufacturers and packaged in the same way as suture. It consists of long woven ribbons of cotton,  to

to  inch wide, and is used for retraction or suspension of small structures and vessels. (Other soft, pliant products, such as vessel loops, are available and more commonly used for this purpose.)

inch wide, and is used for retraction or suspension of small structures and vessels. (Other soft, pliant products, such as vessel loops, are available and more commonly used for this purpose.)

Nylon.

Surgical nylon (Dermalon, Ethilon, Surgilon, Nurolon, Bralon, Monosof) is a synthetic polyamide material. It is available in two forms: multifilament (braided) and monofilament strands. Multifilament nylon is relatively inert in tissues and has a high tensile strength. It is used in conditions similar to those in which silk and cotton are used. Monofilament nylon is a smooth material that is particularly well suited for closing skin edges and for tension sutures. Because of its poor knot security, the surgeon usually ties three knots in small sutures and a double square knot in large sutures. It is used frequently in ophthalmology and microsurgery because it can be manufactured in fine sizes. Size 11-0 nylon is one of the smallest suture materials available.

Polyester Fiber.

Surgical polyester fiber (polyethylene terephthalate, polyester/Dacron) is available in two forms: an untreated polyester fiber suture and a polyester fiber suture that has been specifically coated or impregnated with a lubricant to allow smooth passage through the tissue. Polyester fiber is available in fine filaments that can be braided into various suture sizes to provide good handling properties.

Polybutester (Novafil) is a special type of polyester suture that possesses many of the advantages of polyester and polypropylene. Because it is a monofilament, it induces little tissue reaction.

Polyester material has many advantages over other braided, nonabsorbable sutures. It has greater tensile strength, minimal tissue reaction, and maximal visibility and does not absorb tissue fluids. It is used frequently as a general-closure fascia suture and in cardiovascular surgery for valve replacements, graft-to-tissue anastomoses, and revascularization procedures.

Polypropylene.

Polypropylene is a clear or pigmented polymer. This monofilament suture material (Prolene, Surgilene, Surgipro, Dermalene) is used for cardiovascular, general, and plastic surgery. Because polypropylene is a monofilament and is extremely inert in tissue, it may be used in the presence of infection. It has high tensile strength and causes minimal tissue reaction. Sizes range from 10-0 to #2.

Stainless Steel.

Surgical stainless steel is formulated to be compatible with stainless steel implants and prostheses. This formula, 316L (L for “low carbon”), ensures absence of toxic elements, optimal strength, flexibility, and uniform size. Monofilament and multifilament surgical stainless steel sutures are known for their strength, inert properties, and low tissue reaction. Stainless steel suturing technique is very exacting, however. Steel can pull or tear out of tissue, and necrosis can result from a suture that is too tight. Barbs on the end of steel can traumatize surrounding tissue or tear gloves. Torn or cut gloves fail to provide an adequate and effective barrier for the patient or the surgeon and assistant and can remain undetected. Kinks in the wire can render it practically useless. For this reason, packaging has played an important part in the development of surgical stainless steel sutures. Surgical stainless steel is available in packets on spools or in packages of straight, precut, sterile lengths, with or without attached needles. This packaging affords protection to the strands and delivery in straight, unkinked lengths.

Before surgical stainless steel was available from suture manufacturers, it was purchased by weight with the Brown and Sharp (B&S) scale for diameter variations. Today the B&S gauge, along with USP size classifications, is used to distinguish diameter ranges. Table 7-5 compares steel suture sizes.

Barbed Suture.

Barbed suture is a lesser known suture type. The suture has many small barbs cut into its monofilament core along its length, and is available in several absorbable and nonabsorbable polymers, including polydioxanone, PGA-PCL, and polypropylene. The barbs ensure that the suture stays in place and approximates the tissue without the need to tie knots, ensuring even distribution wound tension and decreased closure time. It is used extensively in plastic surgery and also has applications in other specialties as well such as orthopedics and general surgery (Lombardi et al, 2011) (Figure 7-2). If the suture breaks during suturing, the surgeon leaves it in place and begins again rather than removing it to prevent tissue damage.

Surgical Needles

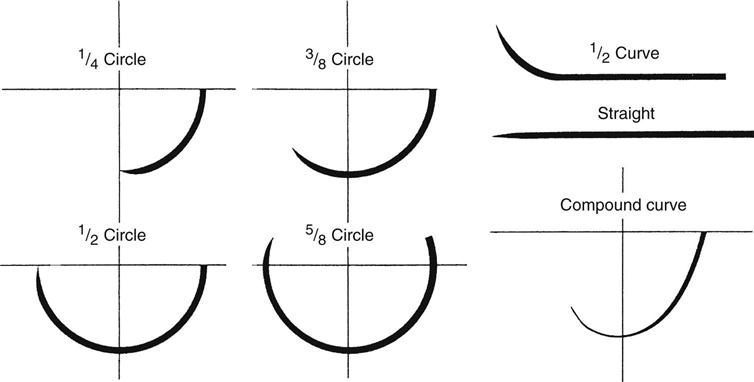

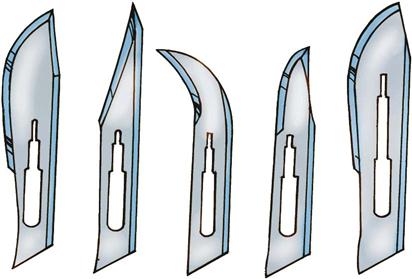

Surgical needles vary in shape, size, point design, and wire diameter (Figure 7-3). Needle selection is determined by the type of tissue, suture material, and action to be performed. Surgical needles are made from stainless steel or carbon steel. Various metal alloys used in manufacturing surgical needles determine their basic characteristics. They must be strong, ductile, and able to withstand the stress imposed by tough tissue. Stainless steel is the most popular, not only because it provides these physical characteristics, but also because it is noncorrosive. The three basic parts of a surgical needle are the eye, the body, and the point or tip.

Eye

The eye of the surgical needle falls into the following three general categories:

1. Eyed needles, in which the needle must be threaded with the suture strand, and two strands of suture must be pulled through the tissue (Figure 7-4, A)

2. Spring, or French, eyed needles, in which the suture is placed or snapped through the spring (see Figure 7-4, B)

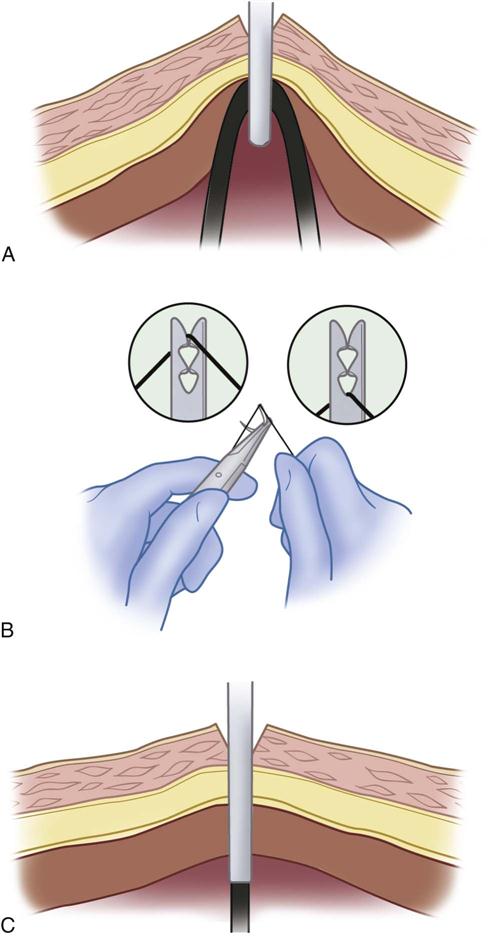

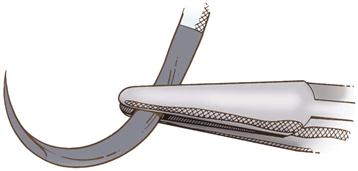

3. Eyeless needles, a needle-suture combination in which a needle is swaged (permanently attached) onto one or both ends of the suture material (see Figure 7-4, C)

The use of eyed needles has all but been eliminated in current surgical practice. The swaged needle is universally available and the preferred method of suture application. The swaged suture is a single strand of suture material that when drawn through the tissue is less traumatic to the tissue than is an eyed needle and suture. The swaged needle may need to be cut off with suture scissors or swaged for controlled release of the suture (semi-swaged), commonly referred to as a “pop off.” With semi-swaged suture, the needle remains attached until the surgeon releases it with a straight tug of the needle holder.

Body

The body, or shaft, of the needle may be round, triangular, or flattened. Surgical needles also may be straight or curved; the curve is described as part of an imaginary circle (see Figure 7-3). As the radius of the imaginary circle increases, the size of the needle also increases. The body of a round needle gradually tapers to a point.

Point

Taper needles, which are round with a point, are the most common needles used and are provided as swaged sutures in many sizes for both absorbable and nonabsorbable materials. Blunt needles are generally indicated for organ biopsy or repair and very delicate tissue that may be torn or injured when penetrated by a sharp needle. The cutting needle, which is round with sharp triangular edges at the objective end of the needle, is most often used for dense or tough tissues such skin closure, thick scar, or bone (Table 7-6).

TABLE 7-6

| Needle Type | Description of Body | Use |

| Taper point | Round shaft, straight or curved, taper point, no cutting edge | Soft tissue closure, such as gastrointestinal, fascial, vascular, and most soft tissues below skin surface |

| Penetrating point | Taper body with finely sharpened point; optimal penetration with less tissue wound | Ligaments, tendons, and calcified, fibrous, and cuticular tissue; mostly used for vascular, thoracic, plastic, obstetrics/gynecology, and orthopedic surgery; excellent penetration through synthetic grafts and scar tissue during repeat surgeries |

| Blunt point | Taper body with rounded point, no cutting edge | Friable tissue, fascia, liver, intestine, kidney, muscle, uterine cervix (note recommendations regarding use of blunt needles, p. 192) |

| Protect-point | Taper body with blunted point, no cutting edge | Primarily in fascia and mass closure to minimize potential of needlesticks |

| Reverse cutting | Triangular point with cutting edge on outer curvature | Skin closure; retention sutures; subcutaneous, ligamentous, or fibrous tissues |

| Cutting taper | Reverse-cutting tip with taper shaft | In microsurgery for excellent penetration through tough tissue, such as vasovasostomy, tuboplasty |

| Hand-honed reverse cutting | Same as reverse cutting but hand-honed for added sharpness | Primarily in plastic surgery for delicate work and where good cosmetic result is priority |

| Spatula side cutting | Two cutting edges in horizontal plane | Ophthalmic surgery for muscle and retinal repair; also for delicate eyelid or plastic surgery; cutting edges “ride” along scleral layers |

| Regular cutting | Triangular point with cutting edge on outer curvature | General skin closure, subcutaneous tissue; sometimes for ophthalmic surgery, plastic, or reconstructive surgery |

| Lancet, inverted lancet | Spatula needle with cutting edge (lancet) or outer (inverted lancet) curvature | Ophthalmic surgery and microsurgery |

Modified from Ethicon product catalog, suture/adhesives, drains, hernia repair, 2009, Available at www.akinglobal.com.tr/medikal/tr/dokumanlar/JHONSON&JHONSON/SUTURES.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2013.

Available blunt protect-point needles have been recommended as an alternative to taper point needles. Interest in blunt needles has evolved because of the risk of bloodborne exposure from percutaneous injuries (PIs).

The use of blunt needles represents a key strategy to reduce risk to the surgical team. Blunt needles are associated with a statistically significant reduction in PIs and can be substituted for conventional curved needles in a variety of surgical procedures.

Triangular needles have cutting edges along three sides. The cutting action may be conventional or reverse. The cutting edge of the conventional cutting needle is directed along the inner curve of the needle, facing the wound edge when suturing is performed.

The reverse cutting needle is preferred for cutaneous suturing. When it transects the skin lateral to the wound, the outside cutting edge is pointed away from the wound edge, and the inside flat edge is parallel to the edge of the wound. This cutting action reduces the tendency for suture to tear through tissue.

For certain types of delicate surgery, needles with exceptionally sharp points and cutting edges are used. Microsurgery, ophthalmic surgery, and plastic surgery require needles of this type; special honing wheels provide needles of precision-point quality for surgery in these specialties. In some instances the application of a microthin layer of plastic to the needle surface provides for easier penetration and reduces drag of the needle through tissue.

Suture Packaging, Storage, and Selection

Types of Packaging

For packaging, the suture material is sealed in a primary inner packet, which may or may not contain fluid; placed inside a dry outer peel-back packet; and sterilized. This method permits easy dispensing onto the sterile field. Various forms of foil, plastic, and special paper are used for the inner and outer packets.

Each primary suture packet is self-contained, and its sterility for each patient is ensured as long as the integrity of the packet is maintained. Some suture packets have expiration dates that relate to stability and sterility. Packages should be stored in moisture-proof and dust-proof containers in units of one size and type.

Suture without needles are packaged as multiple strands and in reels for delivery as free ties. Suture with swaged needles can be packaged as single stitches or as multipacks containing several of the same sutures commonly used for the planned procedure. Multipacks may be permanently swaged needles that require being cut for tying or control-release (pop-off) for easy needle detachment. Some sutures may be double-armed, with a needle at each end of the strand. Double-armed sutures are most commonly used for vascular procedures such as anastomoses and vessel repairs.

Color Codes.

Color-coded packaging based on suture fiber is used by most companies to make identification quicker and easier. Each individual packet is color-coded, as is the dispenser box. Although most color codes are universal across companies, there are some exceptions. Ethibond, a coated polyester, is coded orange, whereas most polyesters are coded in shades of green. Dexon, a glycolic acid polymer, is gold, whereas Vicryl, a comparable polymer, is violet.

Suture Selection

The choice of suture material, size, needle, and type depends on the procedure, the tissue being sutured and type of reapproximation required by the general condition of the patient, and the surgeon's preferences. A surgical services committee or project team may be responsible for establishing standard suture uses for various operations. Current guides published by suture manufacturers should be consulted. These guides list the specific suture materials recommended for various wounds and are based on current clinical practice and research. Although the perioperative nurse is not responsible for choosing the suture material used, he or she must be knowledgeable of the suture properties to ensure the best possible outcome for the surgical patient.

Suturing Techniques/Wound Closures

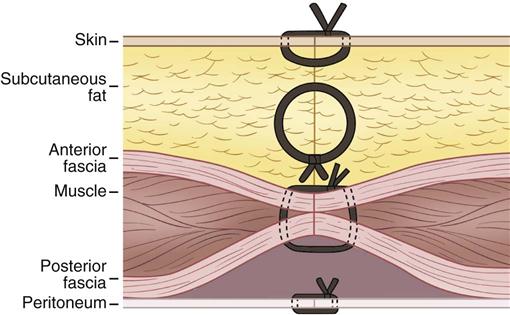

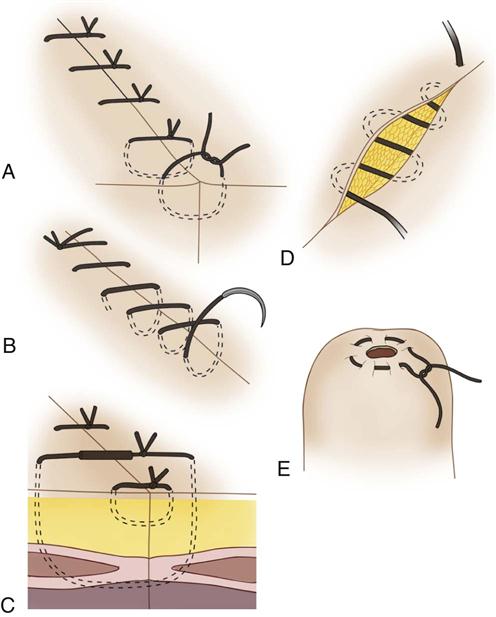

Surgeons may use suture or other devices to accomplish wound closure. The primary suture line refers to sutures that obliterate dead space, prevent serum from accumulating in the wound, and hold the wound edges in approximation until healing takes place (Figure 7-5).

The secondary suture line refers to sutures that supplement the primary suture line. They are placed on each side of the primary suture line, passing through several layers of tissue at once. A secondary suture line helps eliminate tension on the primary sutures and reduces the risk of evisceration or dehiscence. Retention sutures are a type of secondary suture line.

An interrupted suture is inserted into tissues or vessels in such a way that each stitch is placed and tied individually. This type of suture is widely used and generally considered the strongest and most secure (Figure 7-6, A). Although wound closure with interrupted technique is more time consuming, it is intended to distribute stress uniformly along the incision/wound as well as improve strength and encourage better healing. Interrupted closure should be considered when significant preoperative wound healing comorbidities exist, such as COPD, diabetes, infection, and steroid dependence. The interrupted technique is routinely used for bowel and vascular anastomoses and vascular repairs.

A continuous suture consists of a series of stitches, of which only the first and last are tied (see Figure 7-6, B). With this type of suture, a break at any point may mean a disruption of the entire suture line. It is used to close tissue layers where there is little tension but tight closure is required, such as the peritoneum, to prevent the intestinal loops from protruding, or on blood vessels to prevent leakage.

Retention (or stay) sutures are placed at a distance from the primary suture line to provide a secondary suture line (see Figure 7-6, C), relieve undue strain, and help obliterate dead space.

These sutures are placed in such a way that they include most if not all layers of the wound. A simple interrupted or figure-of-eight stitch is used. Usually heavy, nonabsorbable suture materials, such as silk, nylon, polyester fiber, or wire, are used to close long, vertical abdominal wounds and lacerated or infected wounds. To prevent the suture from cutting into the skin surface, a small piece of rubber tubing (bumper, bolster, bootie) or other type of device (bridge, button) is passed over or through the exposed portion of the suture. The bridge device allows the surgeon to adjust tension over the wound postoperatively.

Subcuticular sutures, sometimes referred to as buried, are sutures placed completely under the epidermal layer of the skin (see Figure 7-6 D). This technique is often used to achieve a cosmetic closure.

A purse-string suture is a continuous circular suture placed to surround an opening in a structure and cause it to close (see Figure 7-6, E). This type of suture may be placed around the appendix before its removal, or it may be used in an organ such as the cecum, gallbladder, or urinary bladder before it is opened so that a drainage tube can be inserted; then the purse-string suture is tightened around the tube. It may also be used in plastic surgery for periareolar reduction.

The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) lists suturing as a nursing intervention, defined as “approximating edges of a wound using sterile suture material and a needle” (Bulechek et al, 2013). The NIC was developed to classify nursing interventions so that the work of nursing could be documented and nursing knowledge improved through the evaluation of patient outcomes. In perioperative nursing practice, the act of suturing is considered part of the education and subsequent role of the registered nurse first assistant (AORN, 2012).

General Considerations

In the preparation and use of sutures in surgery, every precaution must be taken to keep the sutures sterile, to prevent prolonged exposure and unnecessary handling, and to avoid waste. Before perioperative personnel prepare any suture materials, they should review the sutures listed on the physician's preference card or in the computerized data/preference sheets. Care should be taken to ensure fiscal responsibility by minimizing the number of sutures on the field when the initial count is performed. The perioperative nurse should have an adequate supply of sutures available for immediate dispensing to the sterile instrument table as needed throughout the procedure.

Customized suture kits that contain a designated number and variety of sutures for particular procedures, surgeons, or both are available for use when suture preferences are consistently the same. These kits may be more economical than individually packaged sutures because of reduced packaging costs, decreased gathering and dispensing times, and less capital outlay for inventory.

Opening Primary Packets

The scrub person tears the foil packet across the notch near the hermetically sealed edge and removes the suture. Some sutures may be packaged for delivery to the field in their inner folders, ready to load, with no foil wrapper.

Handling Suture Materials

To remove suture strands to be used for ties when they are not on a reel or disk, the user pulls the loose end out with one hand while grasping the folder with the other hand. To straighten a long suture, the free end is grasped (using the thumb and forefinger of the free hand) and the kinks, caused by package memory, are removed by gentle pulling with the free ends secured, one in each hand, and then the arms are slowly abducted to straighten the strands (Figure 7-7).

The scrub person should never remove kinks from suture by running gloved fingers over the strand because this action causes fraying. The tensile strength of a gut suture should not be tested before it is handed to the surgeon. Sudden pulls or jerks may damage the suture so that it will break when in use.

To remove a suture-needle combination from the package, the scrub person grasps the needle with a needle holder and gently pulls (Figure 7-8). To straighten the suture in a suture-needle combination, the scrub person grasps the suture 1 to 2 inches distal to the needle and pulls gently on the other end of the strand with the other hand to remove kinks. The jaws of the needle holder grasp the flattened surface of the needle to prevent breakage and bending.

To facilitate suturing, the needle is secured about  inch distal from the tip of the needle holder (Figure 7-9). The holder is placed on the needle about one third of the distance distal from the eye or swaged end.

inch distal from the tip of the needle holder (Figure 7-9). The holder is placed on the needle about one third of the distance distal from the eye or swaged end.

A suture or free ligature should not be too long or too short. A long suture is difficult to handle and increases the possibility of contamination because it may be dragged across the sterile field or fall below it. A short suture makes tying difficult. The depth and distance to the site of tying or suturing guide the scrub person in preparing ties or sutures of the correct length.

For general surgery, a continuous suture swaged on a needle is usually about 24 inches long, and its short end is 3 to 4 inches long (half lengths). An interrupted suture is 12 to 14 inches long, with 2 or 3 inches threaded through the needle (quarter lengths). To ligate a vessel in the epidermal and subcutaneous layers, the ligature may be quarter lengths. Vessels or structures deep in the wound are ligated with a suture or ligature that is 24 to 30 inches long (third lengths to half lengths). Sutures also are provided in 12- to 60-inch precut lengths by the manufacturer. Also supplied are the more commonly used 54-inch lengths on reels or disks and labyrinth packs, where precut strands may be removed one at a time from the package rather than all at once.

Threading Surgical Needles

Free needles, packaged separately, must be threaded by the scrub person. A curved needle is threaded from within its curvature so that the short end falls away from the outside curvature (Figure 7-10). This practice helps to prevent accidental pullout. The scrub person pulls the suture about 4 inches through the eye of the needle to prevent the suture from being pulled out of the eye during suturing.

Knot-Tying Techniques

The successful use of the many varieties of suture materials depends, in final analysis, on the skill with which the surgeon or first assistant ties the knot. The completed knot should be firm to prevent slipping and should be small, with ends cut short, to minimize the bulk of suture material in the wound. The suture may be weakened by inappropriate handling (Research Highlight). Excessive tension, sawing, friction between the strands, and inadvertent crushing with clamps or hemostats should be avoided.

Endoscopic Suturing/Minimally Invasive/Robotic Surgical Knot Tying.

Suturing through an endoscope is a learned skill, not an innate talent. An array of needles and suture materials are available for endoscopic suturing, and research and development of techniques, instruments, needles, and suture materials continue to evolve as the types of procedures done endoscopically, minimally invasive, and robotically assisted increase and methods are perfected. Knot tying is one of the most challenging aspects of endoscopic surgery. Preformed ligature loops are used in ligating the appendix or blood vessels. Extracorporeal knots are tied outside the abdomen and slid into the abdomen using a knot pusher. They can be tied rapidly and securely; the square knot is commonly tied with braided suture and slip, or granny knot, is tied when monofilament suture is used. Intracorporeal knotting is done completely within the abdominal cavity whenever fine sutures are being placed in tissues for reconstruction purposes. When the intracorporeal method is required, the suture is generally precut to a significantly shorter length permitting adequate view and easy access of the suture ends for tying. All suturing and knot-tying techniques performed through the endoscope require excellent hand-eye coordination, practice, and the ability to perform these techniques while the operative site is being viewed on a television monitor. Competency in performing surgical tasks that require the surgeon or surgical assistant perform tasks originating from a three-dimensional (3-D) visual field (extracorporeal) to a two-dimensional (2-D) visual field (intracorporeal via monitor) requires practice, preparation, and focus. Robotic surgical procedures are exceptional examples of these skills. The surgeon performs much of the surgery from a computer console (Figure 7-11) that provides a 3-D visual field, which is possible through the innovation of the bi-ocular telescope. The console also provides the surgeon with control of the robotic instruments and enables him or her to manipulate, dissect, and suture tissue in a similar manner as done in an open surgical procedure. The endoscopic instrumentation is designed to mimic the motion of the human wrist, with 90 degrees of articulation, fingertip control, and intuitive motion. The scrubbed surgical assistant views from a 2-D monitor and performs extracorporeal tasks such as passing suture and implants and using the knot pusher for placing and setting intracorporeal knots.

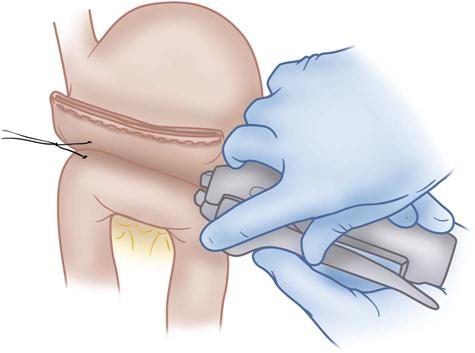

Skin Staples.

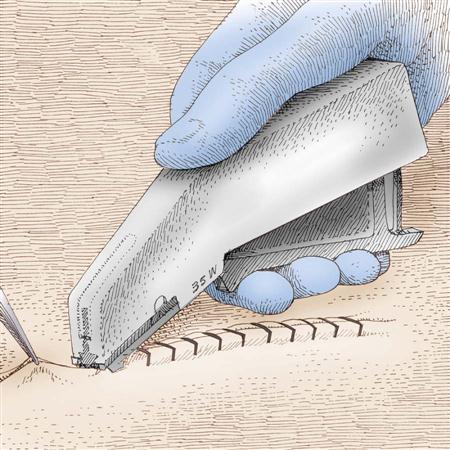

Skin staples are one of the most frequently chosen methods of skin closure and can be used on many types of surgical incisions. The staple appliers are easy to use. They reduce operating time and tissue trauma, allowing uniform tension along the suture line and less distortion from the stress of individual suture points. When properly applied (Figure 7-12), they provide excellent cosmetic results. Some staplers use bioabsorbable staples that are placed under the skin and then absorbed similar to suture. Others use stainless steel staples. With these, the length of time the staples stay in place depends on the part of the body affected; they are usually removed within 5 to 7 days. An extractor is required for their removal.

inch apart.

inch apart.Most staplers use a similar anvil-type mechanism for forming the staple, but the application device varies from company to company. Device choice usually is determined by the weight, handling characteristics, ease of application, and unobstructed view of the site during application. Staplers are packaged in various assortments of numbers and types of staples, depending on the length of the incision and the type of tissue encountered.

Wound Closure Strips.

Wounds that are subjected to minimal static and dynamic tension are easily approximated with skin tape. The selection of surgical tape for skin closure is based on the tape's adhesive ability, tensile strength, and porosity. The tape must provide a firm tape-to-skin bond to keep the wound edges closely adhered. The tensile strength must be sufficient to maintain wound approximation. A tape that is too occlusive limits moisture or vapor transmission; fluid may accumulate under the tape and lead to maceration and bacterial growth. Microporous tapes prevent this problem. The surgeon must apply the tape to dry skin; an adhesive adjunct (e.g., tincture of benzoin or other skin barrier) may be applied in a thin film to the skin at the wound edges before tape application. If an alcohol-based adhesive adjunct is used, care must be taken to prevent inadvertent surgical fires (e.g., electrosurgery unit [ESU] must be shut off before the agent is delivered to the field by the perioperative nurse). Edema at the surgical site may cause taped wound edges to invert; supplemental skin sutures may be used to enhance closure. Tapes may be cut to accommodate smaller incisions. Tapes are applied perpendicularly to the wound edge, first on one side and then the other, so that the edges can be pulled together (Figure 7-13).

Surgical Adhesives.

Tissue adhesives, such as cyanoacrylate, may be used for skin closure by applying on approximated and dry skin edges (Figure 7-14). Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesives combine cyanoacetate and formaldehyde in a heat vacuum along with a base to form a liquid monomer. When the monomer comes into contact with moisture on the skin's surface, it chemically changes into a polymer that binds to the top epithelial layer. Some tissue adhesives include an initiator, which speeds up polymerization.

Topical skin adhesives are best used in areas not subject to high skin tension or across areas in which tension may increase (such as knuckles, elbows, or knees) and can be used to replace subcuticular sutures that are 4-0 or smaller in diameter, as long as the skin edges are tension free and well approximated. They provide a flexible water-resistant protective coating that naturally sloughs off the incision in 7-10 days and may offer equivalent wound cosmesis to sutures.

The surgeon manually and evenly apposes the wound edges, then crushes the vial of adhesive and, depending on the product being used, inverts it or holds it straight up. Next, the adhesive is applied with a gentle brushing motion, while avoiding pressing the applicator tip into the wound. If the adhesive enters the wound it could cause a foreign body reaction and prevent wound healing. The surgeon maintains manual approximation of the wound edges for approximately 60 seconds after applying the adhesive. Multiple layers may be required to be applied based on the product being used. Full polymerization is expected when the adhesive is no longer tacky. No topical liquid or ointments should be applied to the closed wound because they can weaken the polymerized film, causing early peeling and skin separation (Ethicon, 2011).

Hemostasis

Hemostasis is an ongoing process during surgery. In addition to the damaging physiologic effects of blood loss for the patient, bleeding from cut vessels obscures visualization of the operative site for the surgeon and must be controlled. Hemostasis may be accomplished from direct pressure applied with surgical soft goods (e.g., radiopaque sponges or towels) or by the use of suture materials, electrosurgical devices, lasers, and chemical agents. Before wound closure the surgeon carefully checks the operative site to ensure that all active bleeding has been stopped.

Methods of Ligating Vessels

A ligature is a strand of suture material used to encircle and obstruct the lumen of a vessel to affect hemostasis, block a structure, or prevent leakage of materials. Ties may be on a reel (i.e., a spool or disk containing a long length of suture) that the surgeon may use to ligate several superficial vessels, or they may be free ties (i.e., precut lengths of suture) handed to the surgeon one at a time, usually for bleeders in deeper tissues.

Following are several techniques used to secure a ligature in deep tissues:

• A hemostat is placed on the end of the structure; the ligature is then placed around the vessel. The knot is tied and tightened with the surgeon's fingers or with the aid of forceps.

• A slipknot is made, and its loop is placed over the involved structure by means of a forceps or clamp.

• In deeper cavities, ties are often placed on clamps with the long end extending from the tip. These are sometimes called ties on a pass or bow ties. The extending long end is held tightly against the rings by the surgeon (creating the bow), who then passes the tip of the clamp under the vessel or duct to be ligated. The first assistant grasps the extending tie with a forceps, the surgeon releases it, and the tie is pulled under and up to the wound surface and tied.

• A forceps or a clamp is applied to the structure, and transfixion sutures are applied and tied. A suture ligature, stick tie, or transfixion ligature is a strand of suture material threaded or swaged on a needle. This is usually placed through the vessel and around it to prevent the ligature from slipping off the end.

• When two ligatures are used to ligate a large vessel, usually a free ligature is placed on the vessel and a suture ligature is placed distal to the first ligature. To ligate a blood vessel situated in deep tissues, the strand must be of sufficient strength and length to allow the surgeon to tighten the first knot.

Ligating Clips

Ligating clips are small V-shaped staple-like devices that are placed around the lumen of a vessel or structure to close it. They may be made of one of several metals, such as stainless steel, tantalum, or titanium. Stainless steel clips are the most economical to use. Although more expensive, titanium clips are used frequently in specific surgical procedures because the starburst reflection on postoperative radiographs is less with titanium than with other metals. Absorbable clips made of synthetic absorbable suture material also are available.

Ligating clips are available in several sizes. These clips are available in individual sizes that must be loaded by the scrub person or as preloaded, disposable, prepackaged units. (NOTE: The scrub person may be a surgical technologist or RN. He or she is referred to in this chapter as “scrub person.”) Multiple sizes and lengths of clips can be used in both open and endoscopic procedures. Ligating clips afford a rapid and secure method of achieving hemostasis when arteries, veins, nerves, and other small structures are ligated. Since the introduction of minimally invasive endoscopic surgery, the need for ligating clips that can be applied through a trocar has emerged. These clips are changing frequently and no one standard has emerged. Regardless of the type of clip, the surgeon applies them similarly. The surgeon often follows the application of a clip with a request for scissors (Figure 7-15).

Instruments

Historical Perspective

The history of surgical instruments dates back to 2500 BC. The first instruments were sharpened flints and fine animal teeth. Ancient Greek, Egyptian, and Hindu instruments are amazing in their resemblance to contemporary instruments.

To be equipped for the practice of surgery in the late 1700s, the surgeon had to use various skilled artisans, such as coppersmiths; steelworkers; needle grinders; turners of wood, bone, and ivory; and silk and hemp spinners. The surgeon had to explain the mechanisms of the instruments and supervise their manufacture. The resulting instruments were crude, expensive, and time consuming to make. Each artisan used hand labor exclusively and devoted time to making only one type of instrument, thus gaining proficiency in the manufacture of a certain kind of instrument. For example, a cutter would keep a small supply of surgical knives. Thus began physicians' supply houses and surgical instrument making.

In the mid-1800s, physicians' principal tools were their eyes and ears. Official records show that amputation, the trademark of the Civil War, was the end result in three of four operations performed. Surgeons were scarce, and medical instruments were almost nonexistent. Kitchen knives and penknives, carpenter saws, and table forks did the job. After the Civil War the advent of the administration of ether and chloroform brought a demand for new ideas and methods in surgery and instruments. The division of general surgery into specialties occurred in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Delicate instruments were seen as more useful than the force of crude and heavy instruments. So that instruments could withstand repeated sterilization, handles of wood, ivory, and rubber were discontinued.

The development of stainless steel in Germany ensured a better material for surgical instruments and other equipment. Today, surgeons and perioperative nurses assist manufacturers in research, design, and development of new and better instrumentation. Most instrument companies design an instrument to a physician's specifications. Advancement in endoscopic surgery continually requires the development of instrumentation specifically designed for this type of surgery.

Throughout the history of surgery, the tools of the surgeon and the manual aspects of the surgical technique have influenced the evolution of practice. Along with innovative wound closure materials and tools in recent decades, there have been unprecedented developments of new and improved instrumentation. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well documented, especially in surgical procedures that typically required lengthy hospital stays, required long and sometimes difficult postoperative recovery or rehabilitation, and exposed the patient to increased risk of surgical infection.

Composition of Surgical Instruments

Successful management of instrumentation requires a continual partnership between surgeons, perioperative nurses, surgical technologists, and central processing personnel, each of whom shares responsibility for the use, handling, and care of surgical instruments. A basic knowledge of how these instruments are manufactured can help in their selection and maintenance. Surgical instruments are expensive and represent a major investment for every institution.

Instruments used today are made in the United States, Germany, France, and Pakistan. The United States does not have an agency that reviews or sets standards for surgical instruments. The quality is set by the individual manufacturer. A reputable company endorses its product. An instrument that receives proper care should last 10 years or more.

Most instruments are manufactured from stainless steel. Stainless steel is a compound of iron, carbon, and chromium, which means that stainless steel can have varying qualities. These qualities are designated by grading the steel into series by the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI). The 400 series stainless steel has some noncorrosive characteristics and good tensile strength. It resists rust, produces a fine point, and retains a keen edge. Handheld ringed instruments, such as scissors and clamps, should be 400 series stainless steel.

For ringed instruments, the raw steel is converted into instrument blanks by a machinist making an impression of the piece in a stainless steel blank. These blanks are die-forged into specific pieces—male and female halves. The excess metal is trimmed away, and the instrument parts are ready for the final steps.

The two halves are milled to prepare the box lock fittings, jaw serrations, and ratchets, and the jaws and shanks are properly aligned. After this is completed, the halves are assembled by hand. A hole is drilled through the box lock, and a pin or rivet is inserted through the hole. Final grinding and hardening, accomplished by heat-treating, permit the object to attain proper size, weight, spring temper, and balance.

The last part of the process is called passivation. The instruments are submerged into nitric acid to remove any residue of carbon steel. The nitric acid also produces a surface coating of chromium oxide. Chromium oxide is important because it produces a resistance to corrosion in the stainless steel instrument. The instrument is then polished.

There are three types of instrument finishes. The first is the bright, highly polished mirror finish, which tends to reflect light and may interfere with the vision of the surgeon. The second is the satin or dull finish, which tends to eliminate glare and lessen eyestrain for the surgeon. The third finish is ebonized, which produces a black finish. Ebonized instruments are used during laser surgery to prevent deflection of the laser beam.

The final inspection and testing are for hardness, proper jaw closure, and smooth lock-and-ratchet action. The instrument is then ready for sale.

Instrument Categories

Although there is no standard nomenclature for specific instruments, there are four main categories: cutting instruments (also called dissectors), clamps, retractors, and accessory or ancillary instruments.

Cutting Instruments (Dissectors).

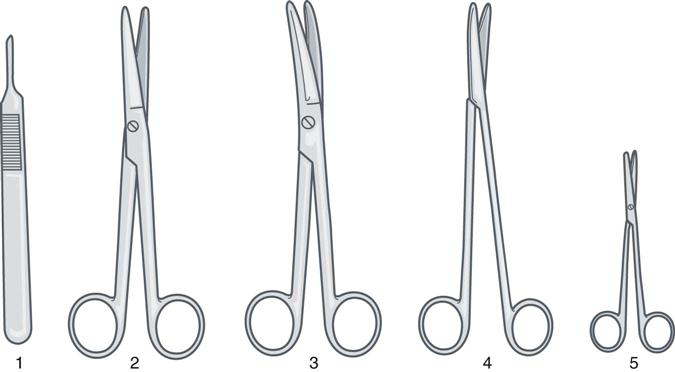

Dissectors, which may be sharp or blunt, are instruments used to cut or separate tissue. The largest categories of sharp dissecting instruments are scalpels and scissors (Figure 7-16). Scalpels are probably the oldest of all surgical instruments. Most scalpels are handles (knife handle) with one end suited to the attachment of disposable blades (Figure 7-17). Safety scalpels have been modified to provide an engineering control in sharps injury prevention strategies. During an operation, the blades may be conveniently changed by the scrub person as often as necessary. The blades are available prepackaged and sterile and are passed onto the sterile field as needed by the perioperative nurse. Careful handling of blades during the procedure and disposal of blades at the end of a procedure are important in the implementation of Standard Precautions.

Scissors are designed in various shapes and sizes for different purposes in cutting body tissues and surgical materials. The basic design consists of two blades, each having a chisel-shaped edge with the bevel consistent with the structure or material it has to cut. Scissor tips may be blunt or sharp, and the blades may be straight or curved. Conventional scissors require two movements in use: one to open and another to close the jaws. Other scissors may have a spring action in the body design that holds the jaws in an open position. A single movement pressing the spring together closes the jaws to cut. Scissors designed for delicate plastic and eye surgery are often of the latter type. A basic instrument set usually includes a curved Mayo scissors for dissection of heavy tissues, a Metzenbaum scissors for dissection of delicate tissues, and a straight scissors for cutting suture. For surgery in deep areas of the body, scissors with long handles and short blades are used for better control and easier use.

Other sharp dissectors include drills, saws, osteotomes, rongeurs, and other instruments such as adenotomes and dermatomes. Some instruments in the dissecting category are produced in sharp or blunt form, such as curettes and periosteal elevators. Instruments or devices used for blunt dissection include gauze dissectors (e.g., peanuts, pushers, kitners), a sponge on a stick, the back of a knife handle, and the surgeon's finger or hand.

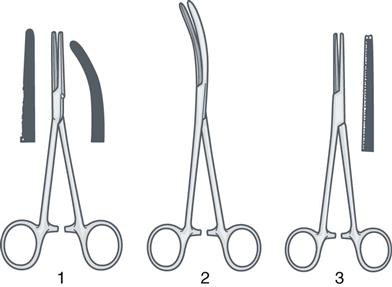

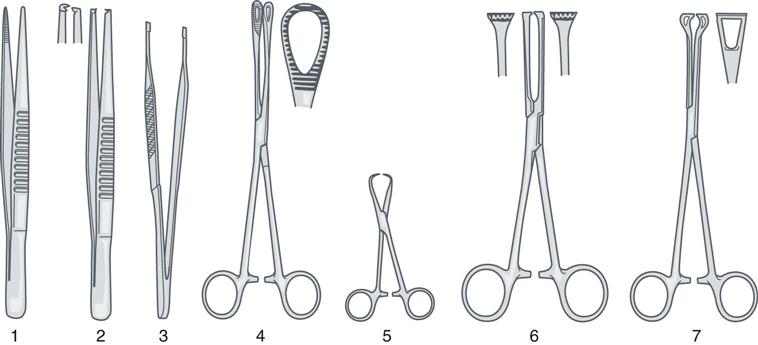

Clamps.

Clamps are instruments specifically designed for holding tissue or other materials, and most have an easily recognizable design (Figure 7-18). They have finger rings, for ease of holding; shanks, whose length is appropriate to the wound depth; ratchets on the shanks near the rings, which allow for the distal tip to be locked on the tissue or object grasped; a joint, which joins the two halves of the instrument and allows opening and closing of the instrument. Instruments made up of two halves have one of three types of joints.

• The most common joint is the box lock, where one arm has been passed through a slot in the other arm and is riveted or pinned. This joint is needed where accurate approximation of the tips is necessary, and it is basic to most ringed instruments.

• The second type is the screw joint. The two halves are aligned and placed on top of each other, connected only by a screw. The joint must be checked and tightened periodically because the screw may become loose. Screw-joint instruments are easy to make and comparatively inexpensive.

• The final and least common type is the semibox, or aseptic, joint. It has the advantage that the two halves can be separated for easy cleaning.

Clamps also have a jaw, which is the working portion of the instrument and defines its use (Figure 7-19). Clamps are divided into the following categories.

Hemostats are used to close the severed ends of a vessel with a minimal amount of tissue damage. They prevent the excessive loss of blood in the course of dissection. The jaws have deep transverse cuts so that the bleeding vessels may be compressed with sufficient force to stop bleeding. The serrations must be cleanly cut and perfectly meshed to prevent the tissue from slipping free from the jaws of the clamp.

Occluding clamps usually have vertical serrations or special jaws that have finely meshed, multiple rows of longitudinally arranged teeth to prevent leakage and to minimize trauma when clamping bowel, vessels, or ducts that are to be reanastomosed.

Graspers and holders are used for tissue retraction and generally have jaws of specific design based on their use. The Kocher (also referred to as an Ochsner) clamp has transverse serrations and large teeth (1 × 2) at its tip to grasp tightly on tough, slippery tissue such as fascia. The Allis clamp has multiple, interdigitating short teeth on the tip, minimizing crushing or damaging tissue. The Babcock clamp has broad, flared ends with smooth tips, and it atraumatically grips or encloses delicate structures, such as bowel, ureters, or fallopian tubes. Other holding forceps have handles like clamps with specialized tips or jaws, which may be triangular, straight, angular, or T-shaped (Figure 7-20).

Non-clamp graspers and holders are known as forceps or pickups because they are used to lift and hold tissue (see Figure 7-20). Often, while the surgeon is cutting with scissors or sewing with a needle, forceps are used in the other hand. Forceps are held like a pencil. The most common kinds are the various two-arm spring forceps. Forceps resemble tweezers, vary in length and thickness, and are available with and without teeth. Non-toothed forceps create minimal damage and hold delicate, thin tissues. Toothed forceps hold thick or slippery tissues that need extra grip. Toothed forceps (“rat tooth”) have interdigitating teeth that hold tissue without slipping; these are used to hold skin or dense tissue. Adson tissue forceps have small, serrated teeth on the edge of the tips; these are designed for light, careful handling of tissue and are commonly used during skin closure.

Grasper and holder clamps may hold objects as well. Sponge-holding forceps with ring-shaped jaws (see Figure 7-20) are available in 7- and 9-inch lengths. They can be used to grasp or handle tissue but are commonly used to hold soft goods. The soft good is folded and placed in the jaws and is used to retract tissue, to absorb blood in the field, and occasionally to perform blunt dissection.

Needle holders (Figure 7-21), because they must grasp metal rather than soft tissues, are subject to greater damage. As a result, needle holders must be repaired and replaced regularly. For maximal usage, needle holders must retain a firm grip on the needle. Many types of jaws have been designed to meet this need. The so-called diamond jaw needle holder has a tungsten carbide insert designed to prevent rotation of the needle. In needle holders of standard design, a longitudinal groove or pit in the jaw releases tension, prevents flattening of the needle, and holds the needle firmly. Needle holders may have a ratchet similar to that of a hemostat, or they may have a spring action that may or may not lock.

Towel clamps also are considered holding instruments. Of the two basic types, one is a nonpenetrating towel clamp used for holding draping materials in place. The other has sharp tips used to penetrate drapes and tissues, and it is damaging to both. The use of sharp towel clamps to secure drapes is highly discouraged because they penetrate the sterile field.

Retractors.

Retractors are used to hold back the wound edges, structures, or tissues to provide exposure of the operative site. A surgeon needs the best exposure possible that inflicts a minimal degree of trauma to the surrounding tissue. Retractors are self-retaining or manually held in place by a member of the surgical team (Figure 7-22). The two types of self-retaining retractors are (1) retractors with frames to which various blades may be attached, and (2) retractors with two blades held apart with a ratchet. An example of the latter is a Weitlaner retractor. Other very large self-retaining retractors, such as the Omni or Bookwalter, are equipped with multiple blades and attachments of varying lengths and sizes. With handheld retractors, the handles may be notched, hook-shaped, or ring-shaped to give the holder a firm grip without tiring. The blade is usually at a right angle to the shaft and may be a smooth blade, rake, or hook. A malleable (ribbon) retractor is a flat metal ribbon that may be shaped at the field.

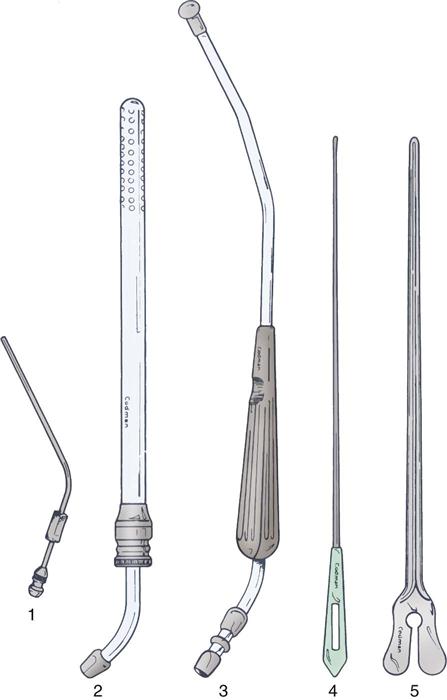

Accessory and Ancillary Instruments.

Accessory and ancillary instruments are designed to enhance the use of basic instrumentation or to facilitate the procedure (Figure 7-23). These include suction tips and tubing; irrigators-aspirators; electrosurgical devices; and special-use devices, such as probes, dilators, mallets, and screwdrivers.

Many miscellaneous instruments or specialty items are particular to a certain specialty but generally fall into one of the categories just mentioned. Microsurgical instruments are delicate and expensive. They are extremely fine and should be handled separately from other instruments. Instruments used in specialty surgery are discussed in each of the chapters under Surgical Interventions.

When perioperative members can analyze the planned surgical procedure and approach and identify each instrument and its specific function, they are able to select instrument sets without omitting necessary items and without including items that will not be used. This intelligent, planned approach ensures economy of time and motion, protects instruments from misuse, and prevents unnecessary handling. During the operation the informed scrub person who anticipates instrument needs becomes a more valuable member of the surgical team.

Endoscopic Instrumentation

Laparoscopy has introduced new equipment and instrumentation to the surgical suite. In addition to insufflation equipment, an optical system, and a documentation system, perioperative personnel must be familiar with the instrumentation used by the surgeon when performing a surgical procedure through the endoscope. Basic instrumentation, which may be disposable or reusable, includes trocars, forceps or graspers, clip appliers, stapling devices, scissors, needle holders, and aspiration-irrigation systems.

Verres needles and trocars provide access to the peritoneal and thoracic cavities. A retractable safety shield protects abdominal structures from being inadvertently punctured during insertion. Forceps or graspers are available in 3-, 5-, and 10-mm sizes. Atraumatic graspers provide appropriate retraction and little risk to tissues. Bipolar coagulation forceps are used to control bleeding. The forceps are available with different tips, including ring, paddle, dolphin nose, claw, spoon, DeBakey, Allis, Pollack, Pennington, Glassman, Maryland, Reddick-Saye, Duval, and Babcock. Some dissectors are available with coagulation capability. Scissors also come with different tips: hook, straight and microtipped, serrated, and curved. Also, several disposable instruments coagulate and cut the tissue.

Needle holders have a hinged-jaw tip to allow easy positioning of the needle before intracorporeal suturing and using the sliding sheath. The sliding sheath holds the needle in a distal notch and inner spring-loading mechanism. To aid with extracorporeal knot tying, the surgeon may use a knot pusher (e.g., a Clarke-Reich) to deliver tied knots into the abdomen. A slide and cinch pusher (Gazayerli) also is used to deliver and secure the preformed knot. Intra-abdominal stapling devices have been modified to fit and function through the endoscope. The development and introduction of robot-assisted surgery has produced a new generation of multiarticulating instruments.

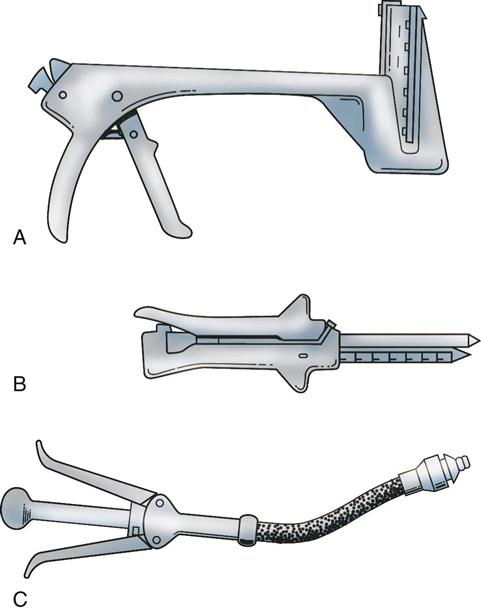

Stapling Instruments

Instrumentation for internal stapling, first introduced in 1908, has been refined and is now widely used (Figure 7-24). Various instruments to suture tissue mechanically are used for ligation and division, resection, anastomoses, and skin and fascia closure. In general, these instruments may be classified as follows (Neumayer and Vargo, 2012):

• Ligating and dividing staplers (LDSs)

• Gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) staplers

• Thoracoabdominal (TA) staplers

• End-to-end anastomosis (EEA) staplers

Used in many surgical specialties, the mechanical application of these instruments reduces tissue manipulation and handling. The edema and inflammation that usually accompany anastomoses are minimized because the noncrushing B shape of the staples allows nutrients to pass through the staple line to the cut edge of the tissue (Figure 7-25).

Mechanical staplers (both nondisposable and disposable) use cartridges of tiny stainless steel staples or absorbable nonmetallic staples that are commercially preloaded, prepackaged, and presterilized. The staples are essentially nonreactive; metal staples remain permanently in the tissue. The staplers may fire individually or lay down multiple rows in a straight or circular pattern. Devices to cut or anastomose bowel and other structures are available for open-wound use or through endoscopic cannulae. The use of staplers significantly decreases operating time and may shorten postoperative stays.

Selecting and Preparing Instruments for Patient Use

Designated OR or central supply personnel arrange the various instruments into trays or sets. The trays are named according to their functions. Tray/set names and instrument composition vary by institution, but three basic OR instrument sets are the minor/plastic, the basic laparotomy, and the dilation and curettage (D&C). A minor (or plastic surgery) set includes instruments needed for simple superficial incision, excision, and suturing. A basic laparotomy set includes instruments to open and close the abdominal cavity and repair any gross defects in the major body musculature. A D&C set, in addition to its use for dilation and curettage, is often used as the basic instrumentation for vaginal surgery.

According to each procedure's needs, more individualized instruments or specialty sets, such as an intestinal set or a vascular set, may be added. In the same way, basic instrument sets may be selected for opening other body cavities, such as the skull, chest, and pelvis.

Instruments are selected according to the size of the patient's body structures and the nature of the organs involved. Proper selection requires a general understanding of surgical procedures and approaches and knowledge of anatomy, possible pathologic conditions, and the design and purpose of instruments.

Basic Table Setups.

In most ORs the instruments are set up on Mayo stands and back tables in a planned, standardized, organized, functional manner to maintain continuity when the original scrub person is replaced by another. Care is taken on all sterile fields to ensure that all solutions, syringes, and medication cups are clearly labeled to guarantee patient and staff safety. Each facility should create tools as a part of a comprehensive orientation process to ensure standardization of setups.

A proficient scrub person must know the instrument inventory of the department; the instruments routinely needed for each type of operation; the individual surgeon's preferences; and the correct use and handling, method of preparation, and postoperative care of the instruments. A file of preference cards or computerized data/preference sheets usually lists the procedures each surgeon performs, the surgeon's glove size, the preferred skin prep solution, specific draping instructions, and instruments required for the procedure.

Before an operative procedure, the scrub person may assist the perioperative nurse in gathering the needed supplies, equipment, and sutures. The scrub person scrubs; dons gown and gloves; and begins to set up the sterile tables with drapes, instruments, supplies, and sutures. Instruments are arranged with those most frequently used on the Mayo stand.

One or two back tables, according to the number of instruments and supplies, also are set up. The scrub person prepares the sutures and ligatures and places the knife blades on the handles. Other supplies needed are suction tubing and tips, electrosurgical cord and tip, drains, basins, gowns, gloves, drapes, sponges, and needles, all of which are sterile and set up on the back table according to standardized institutional policy (Figure 7-26). During the final “time-out” before incision, the scrub person has the responsibility to articulate instrument and equipment readiness to the team to enhance a safe, seamless procedure. When the patient is on the OR bed and is draped, the Mayo stand, set up for instrument use at the immediate operative site, is brought across the lower part of the patient's legs (Figure 7-27).

The scrub person must be attentive to the sterile field to anticipate the surgeon's needs. Instruments should be passed in a positive and decisive manner. Each instrument is placed or slapped firmly into the surgeon's palm in such a manner that it is ready for immediate use with no wasted motion. When a curved instrument is passed to the surgeon, the curve should be pointing in the direction of intended use; there should be no need for readjustment. It is necessary to know if a surgeon or assistant is left-handed or right-handed to pass instruments efficiently and in the correct position.

Often the surgeon or assistant uses hand signals for the type of instrument desired, to eliminate unnecessary talking. Scrub persons should become familiar with the basic signals for knife, scissors, suture, forceps, and clamp.

Care and Handling of Instruments.

An instrument should be used only for the purpose for which it is designed. Proper use and reasonable care prolong its life and protect its quality. Scissors and clamps, which are most frequently misused, can be forced out of alignment, cracked, or broken when used improperly. Tissue scissors should not be used to cut suture or gauze dressings. Hemostatic clamps should not be used as towel clamps or to clamp suction tubing.

Each instrument should be inspected before and after each use to detect imperfections. An instrument should function perfectly to prevent needlessly endangering a patient's safety and increasing operative time because of instrument failure.

Forceps, clamps, and other hinged instruments must be inspected for jaw and teeth alignment. Instrument jaws and teeth should meet perfectly so that blood flow is occluded without damaging the vein or artery. Ratchets should hold firmly yet release easily. Instrument joints should work smoothly.

All instruments should be checked for worn spots, chips, dents, cracks, or sharp edges. Damaged instruments should be set aside and sent for repair or replacement. An instrument repair service should be selected carefully and used for regular maintenance, such as sharpening and realignment.

Instruments must be handled gently. Bouncing, dropping, and setting heavy equipment on top of them must be avoided. During the procedure the scrub person should wipe the used instruments with a damp sponge or place them in a basin of sterile water to prevent blood from drying on the surfaces and in the box locks. Saline solution should never be used on instruments because the salt is corrosive and accelerates rusting or deterioration of the metal. As time allows during the procedure, the scrub person should rinse and dry the used instruments and replace them on the back table to facilitate closing counts.