Cardiac Surgery

Patricia C. Seifert

Cardiac surgery is increasingly moving toward interventional procedures that use minimally invasive approaches and percutaneous access routes. The introduction of coronary angioplasty in the 1970s accelerated interventional technology and stimulated perioperative clinicians to expand both traditional and innovative treatment options. These changes have also encouraged individuals to refine anastomotic techniques, investigate new routes to achieve cardiopulmonary bypass and vascular repair, design more tissue-friendly instrumentation, and create operative arenas that embrace aspects of both the typical operating room (OR) and the newer interventional suites. These newer, “hybrid” ORs have stimulated cardiac clinicians to expand their skill sets, develop closer working relationships with colleagues in the cardiac catheterization and electrophysiology laboratories, and reassess how these changing technologies can strengthen the delivery of patient-focused care (Weisse, 2011). Other advances have included the growth of precise, three-dimensional diagnostic images; improved monitoring of neurologic and renal function; effective blood conservation strategies; refined anesthetic and cardiac drugs; and an overall greater understanding of the causes and treatment of glucose abnormalities, antibiotic-resistant infections, and other abnormalities that affect patient outcomes (Hatton et al, 2011; Nalla et al, 2012; Nussmeier et al, 2009; Teirstein and Lytle, 2012).

Other trends that have significantly affected cardiac surgery include heightened emphases on safety, education, quality outcomes, staff competence, and cost-effectiveness (Speir et al, 2009). The use of a simple checklist to ensure correct identification of the patient or that performance of a central line insertion is in a manner that eliminates or minimizes the risk of a catheter-based infection (Lipitz-Snyderman, 2011) are among the many safety initiatives that produce better patient outcomes.

This chapter describes both traditional and newer, innovative treatment options for coronary artery disease (CAD), valvular dysfunction, thoracic aneurysms, conduction disturbances, heart failure, and end-stage cardiac disease. Therapeutic interventions may use laser, radiofrequency, or cryothermal energies. Stem cell therapy, used to induce cardiac neorevascularization at the cellular level (Jeevanantham et al, 2012), and “destination” mechanical assist devices (which remain implanted)—or devices that can result in the “recovery” of the ventricle—are among the newer areas of investigation showing great promise (Acker and Jessup, 2012).

Surgical Anatomy

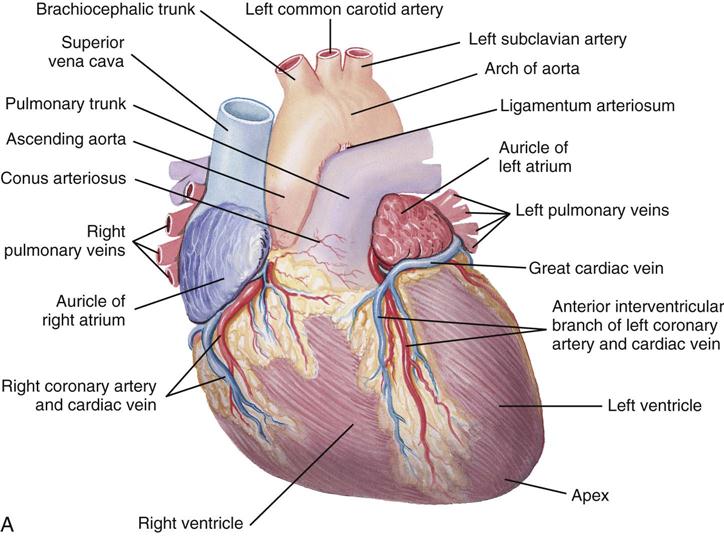

The heart (Figure 25-1) is a four-chamber muscular pump that propels blood into the systemic and pulmonary circulatory systems. It sits within a pericardial sac within the mediastinum, which lies between the lungs, posterior to the sternum, and anterior to the vertebrae, esophagus, and descending portion of the aorta. The location of the diaphragm is below the heart (Figure 25-2). The heart bears attachments at the aorta, pulmonary artery, superior and inferior venae cavae, and the pulmonary veins; the ventricles are relatively mobile, enabling the surgeon to rotate the walls of the ventricles and the apex of the left ventricle in order to assess (and graft) coronary arteries to the lateral and posterior aspects of the myocardium.

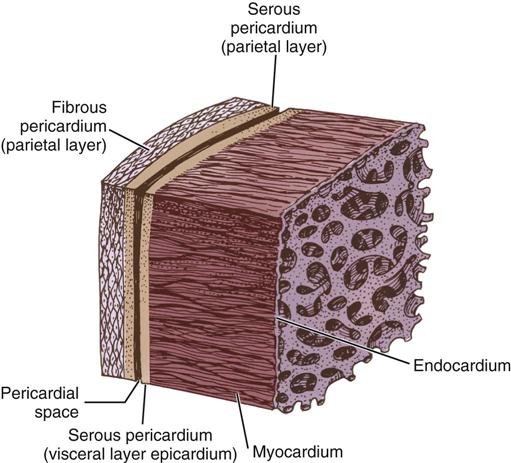

The cardiac wall consists of three layers: the epicardium or outer lining; the myocardium or muscular layer, an important functional layer; and the endocardium or inner lining (Figure 25-3). The left ventricular muscle layer has the most depth (i.e., thickness) of the four chambers and can generate the greatest pressure, required to pump blood into the circulatory system.

Two thirds of the heart are to the left of the midline, and the remaining one third is to the right. Although functionally divided into right and left halves, the heart sits rotated to the left, with the right side anterior and the left side relatively posterior. Injury to the anterior chest (e.g., from blunt force or stab wounds) is likely to damage the right ventricle. This may prove significant for myocardial repair because the right ventricle has lower pressures than the left, thus allowing additional time for repair before exsanguination.

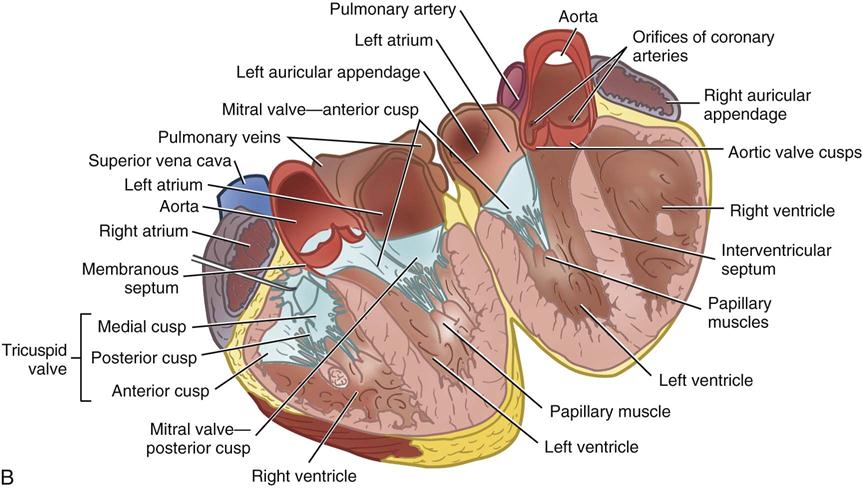

Each half of the heart contains an upper and a lower communicating chamber—the atrium and ventricle, respectively. The right atrium (RA) receives desaturated blood from the inferior and superior venae cavae and from coronary circulation via the coronary sinus. The left atrium (LA) receives oxygenated blood from the lungs by way of the pulmonary veins. From both atria, blood then flows through the atrioventricular (AV) valves into the ventricles.

The left ventricle (LV) pumps oxygenated blood into the major vessels of the systemic circulatory system by way of the aorta and its main branches to the head, upper extremities, abdominal organs, and lower extremities. The right and left internal mammary arteries (IMAs) (thoracic), used as grafts during coronary bypass surgery, branch off the subclavian arteries and course behind and parallel to the edges of the sternum. The arteries of the circulatory system subdivide into arterioles and eventually into capillaries and the individual cells, where internal respiration and metabolic exchange occur. From the cells and capillary beds, desaturated blood flows into the venules and veins and finally returns to the RA.

In the pulmonary circulatory system, blood pumps from the right ventricle (RV) through the pulmonary valve into the main pulmonary artery (PA). The PA divides into the right and left pulmonary arteries, which further subdivide into the arterioles and capillaries of the lungs. External respiration occurs in the capillary beds and the alveoli, wherein carbon dioxide exchanges for oxygen. Freshly oxygenated blood from the lungs then flows through the pulmonary veins into the LA.

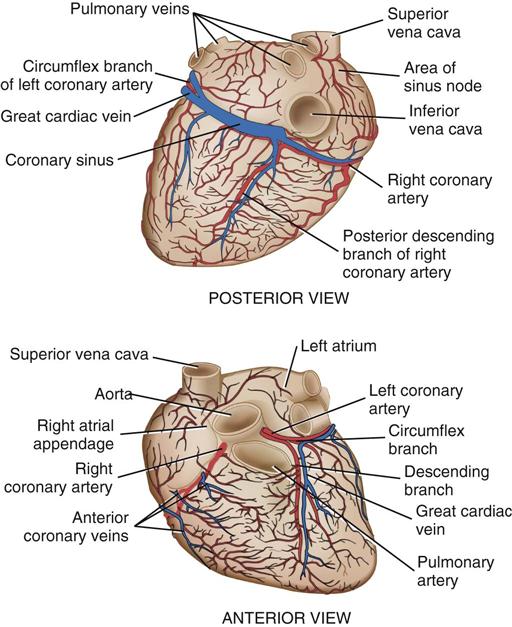

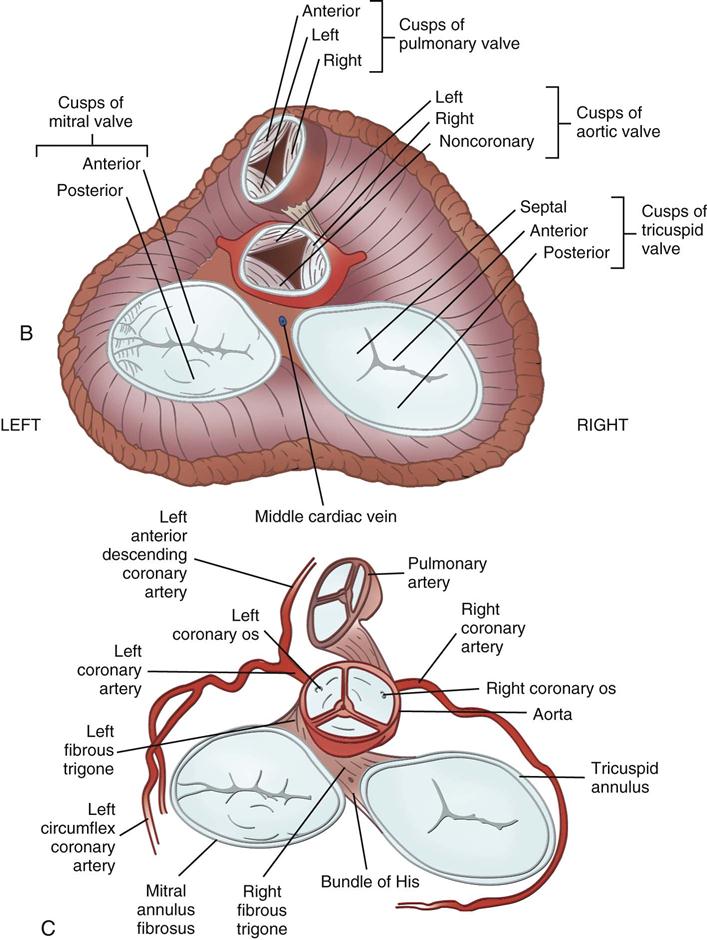

Coronary circulation (Figure 25-4) supplies oxygen and nutrients to, and removes metabolic waste from, the myocardium; internal respiration occurs in the myocytes. The heart receives its blood supply from the left and right coronary arteries, which originate in the corresponding left and right sinuses of Valsalva behind the cusps of the aortic valve in the ascending aorta. The left main coronary artery divides into the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery and the circumflex coronary artery; with the right coronary artery (RCA), these arteries are the three main vessels of the coronary arterial system.

In coronary arteries affected by CAD, focal or diffuse atherosclerotic plaques develop and progressively enlarge, diminishing myocardial blood flow and oxygenation, which produces ischemic pain in many, but not all, cases. Occlusion of a coronary artery by expanding atherosclerotic lesions causes myocardial infarction (MI) and irreversible damage to the region of the myocardium perfused by the obstructed artery. Coronary artery bypass procedures increase blood flow to the affected ischemic areas by attaching a bypass graft conduit to the artery distal to the narrowed portion of the artery. A totally occluded (infarcted) artery does not benefit from bypass surgery because the myocardial injury is irreversible if not treated (e.g., via revascularization) within 6 hours (Jneid et al, 2012). The main coronary arteries sit in the epicardium, which facilitates accessibility during coronary bypass procedures. From these arteries arise the septal perforators and other branches that penetrate the entire myocardium. The cardiac veins empty into the RA by way of the coronary sinus; the thebesian veins, prominent in the walls of the RA and the RV, open directly into these chambers.

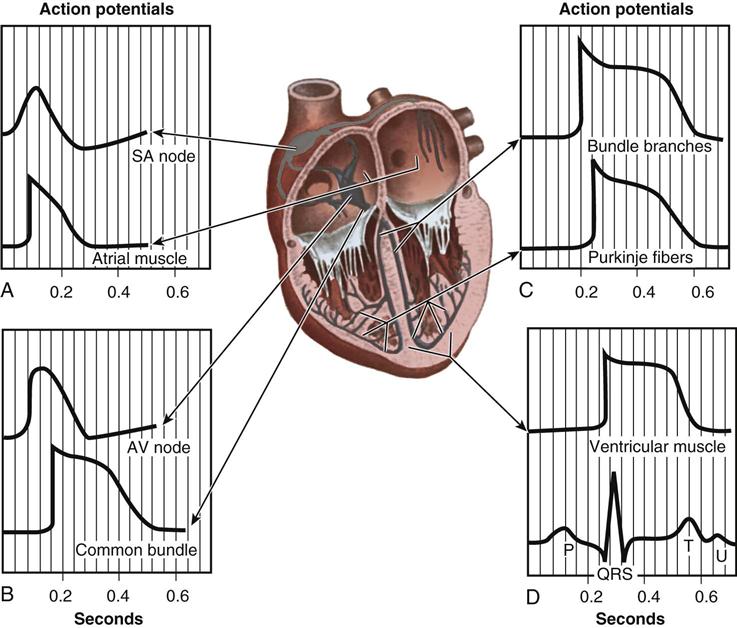

From the medulla oblongata, nerve impulses to the heart travel along the middle cervical nerve, composed of sympathetic fibers, and the vagus nerve, composed of parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic fibers increase the force and rate of contraction, whereas parasympathetic fibers control heart rate. Running vertically along the right and left sides of the pericardium are major branches of the phrenic nerve, which innervate the diaphragm and stimulate it to contract. In order to protect the diaphragm, identifying the phrenic nerve is important in procedures that involve incision or excision of the lateral pericardium. Within the myocardium itself, certain areas of tissue undergo natural modification to form a conduction system (Figure 25-5). The process of excitation and contraction originates in the sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the area where the superior vena cava (SVC) meets the RA. The impulse spreads to the atria through internodal pathways and travels to the AV junction (which contains the AV node) located medial to the entrance of the coronary sinus in the RA, close to the tricuspid valve. From the AV junction, the impulse spreads to the bundle of His, which extends down the right side of the interventricular septum. The bundle of His divides into the right and left bundle branches, which terminate in a network of fibers called the Purkinje system. Purkinje fibers are spread throughout the inner surface of both ventricles and the papillary muscles, which when stimulated produce contraction of the heart muscle. Thus the location of conduction tissue is clinically significant during surgical repair of atrial or ventricular septal defects.

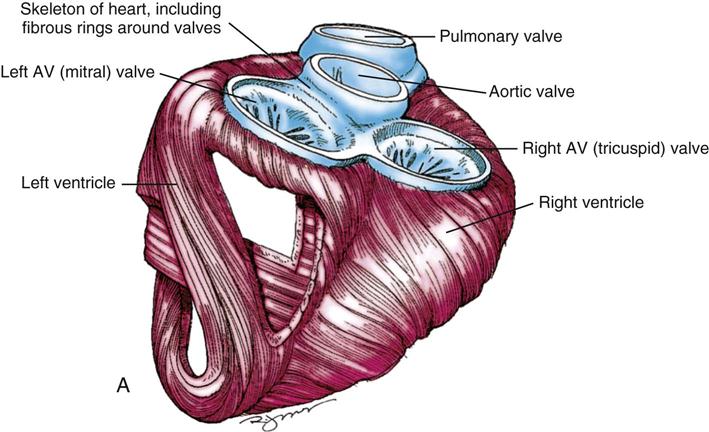

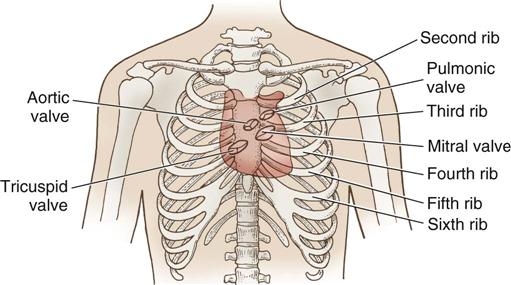

During myocardial contraction and relaxation, spiral fibers of the heart contract and relax (Figure 25-6, A). To prevent regurgitation of blood, the four cardiac valves (see Figure 25-6, B and C, and Figure 25-7) open and close to maintain unidirectional blood flow. The AV valves are between the atria and the ventricles. The right AV valve is called the tricuspid valve and contains three leaflets (or cusps). The left AV valve, called the mitral valve, consists of two leaflets (see Figure 25-6). Each AV valve is a complex system consisting of a fibrous annulus surrounding the valve orifice, the valve leaflets, the chordae tendineae, the atrium, and the papillary muscles, which anchor the valve to the inner ventricular wall (see Figure 25-1). The mitral valve annulus is a dynamic structure with a three-dimensional “saddle” shape, which has stimulated the design of newer prosthetic annuloplasty rings (Silbiger, 2012). When the ventricle contracts, these muscles and the chordae tendineae, connected to the valve leaflets, prevent the leaflets from everting into the atrium. All parts of the system must function for the valve to work properly. If the shape of the ventricle has been changed by dilation or hypertrophy, for example, the altered geometry of the ventricle impairs ventricular function. Conditions such as hypertension, myocardial injury, and aortic stenosis promote a pathologic remodeling of the heart that can lead not only to valvular dysfunction but also heart failure and malignant dysrhythmias (Gopaldas, 2012).

The semilunar valves are at the outlets of the LV and RV. These valves are known as the aortic and pulmonic valves, respectively. They have fewer components than the AV valves, and they open and close passively with cyclic fluctuations in blood pressure and volume that occur during systole and diastole.

Abnormalities such as stenosis, insufficiency, or a combination of both impair the mechanical function of the valves. Stenosed valves have leaflets that are fibrous and stiff, with uneven and adherent margins. Regurgitant, insufficient, or incompetent valves, such as those with leaflet degeneration or perforations, dilated annuli, or ruptured chordae tendineae, produce regurgitation of blood into the originating chamber. These conditions, or a combination of stenosis and insufficiency, strain the myocardium by increasing intracardiac pressure, volume, and workload. The sound of blood flowing through a narrowed or incompetent valve produces an abnormal sound called a murmur.

Any of the four valves may be deformed congenitally. Acquired valvular heart disease most commonly affects the mitral and aortic valves and appears to worsen with increased stress associated with the higher pressures within the left chambers of the heart. Although rare, primary tumors of the heart may impair valve function by partially occluding a valve orifice, causing incomplete closure of the leaflets. Portions of the tumor may break off and embolize. Most tumors are benign; the most common is the cardiac myxoma. Diagnostic imaging can identify many of these lesions, but the lesion may not cause symptoms to motivate a person to seek medical treatment (McManus, 2012).

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

Specialized nursing considerations that apply to thoracic surgery (see Chapter 23) and to vascular surgery (see Chapter 24) often also apply to cardiac surgery. Pediatric cardiac procedures appear in Chapter 26.

Assessment

As the severity of pathologic changes varies among patients throughout the life span, knowledge of physical status, psychosocial concerns, and functional health patterns enables the perioperative nurse to plan and manage patient care. The perioperative nursing data set should include the patient's biopsychosocial history, the physical examination, and results from laboratory and diagnostic imaging tests.

History.

The history includes information about the patient's health status as well as the response to the disease and the recommended intervention or interventions. Patients with cardiac disease may display such symptoms as ischemic chest pain (angina pectoris), fatigue, dyspnea, and syncope. Depending on their severity, these subjective symptoms affect the patient's functional status and ability to engage in activities of daily living; the New York Heart Association's Functional Classification System (Box 25-1) is often used to assess functional ability. Updates to the classification system also include objective measurements such as x-rays and echocardiograms (American Heart Association [AHA], 2012 a,b).

Atypical ischemic chest pain is more likely in women than in men, and angina may arise from vasospastic angina, mitral valve prolapse, or psychologic factors. CAD is unusual in premenopausal women; after menses ends, however, the risk is similar to that of men (AHA, 2013; Caboral, 2013; Mosca et al, 2011; Roger et al, 2012; Wenger, 2012). Controversy exists regarding menopausal hormone therapy. Estrogen hormone replacement therapy is not recommended in postmenopausal women, according to the Evidence-Based Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Women: 2011 Update (Mosca et al, 2011) (Evidence for Practice). Greater emphasis is being placed on effectiveness of interventions as well as on the evidence supporting those interventions; effective control of blood pressure, diabetes management, and maintenance of optimal lipid levels are significant risk reduction interventions for women (Caboral, 2013).

Women undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) also have some unique challenges and experiences. According to Banner and colleagues (2011), some women may minimize any public display of illness in an attempt to preserve the appearance of normalcy; they even may hesitate to tell significant others about impending surgery until the day before admission. Postoperatively they may wish to return home early in order to resume regular activities. Once home, some women were unprepared for the limitations that they faced, both physical and social; the authors recommend focused advice, support, and education (Banner et al, 2011).

A cardiovascular disease risk factor profile (Box 25-2) is helpful to plan care for hospitalization and discharge by focusing on areas that might require further patient education. For example, diabetes is a risk factor because it affects the vascular system, may retard healing, and may predispose the patient to infection. Of special concern is the epidemic growth of type 2 diabetes in particular and the role of hyperglycemia in general. Although type 2 diabetes formerly was considered an adult-onset disease, children are increasingly vulnerable because of a greater incidence of increased body weight, sedentary lifestyle, and accelerated insulin resistance (Roger et al, 2012). Altered glucose metabolism (absent diagnosed diabetes mellitus) has shown a significant correlation to atherosclerosis; control of hyperglycemia during coronary bypass surgery is an important strategy to reduce the risk of adverse clinical outcomes (Hillis et al, 2011; Nussmeier et al, 2009).

In addition to elevated lipid or cholesterol levels, inflammation increasingly has been implicated in the development of CAD. In particular, elevated homocysteine levels (which increase platelet aggregation) and high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels have been implicated (CRP is a biologic marker for inflammation and is associated with increased risk for CAD) (Horak et al, 2011). Additional recognized risk factors include metabolic syndrome (central obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia) and obesity (Hillis et al, 2011; Roger et al, 2012). Hypertension and obesity increase the workload of the heart; obesity may also increase the risk for postoperative infection because adipose tissue vascularizes poorly. Additionally, a growing percentage of the population is aging. Age, in and of itself, rarely contraindicates intervention, but comorbidities often associated with older individuals constitute additional risk factors and areas—for example, cognitive impairment, depression, and decision-making capacity—that may require investigation (Chow et al, 2012).

Among the newer biomarkers denoting cardiovascular diseases are the natriuretic peptides—cardiac hormones synthesized and secreted by the atrium (atrial natriuretic peptide [ANP]) and the ventricle (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP]). Discovered in 1981, natriuretic peptides have a regulatory effect that causes myocardial relaxation in response to acute increases in ventricular volume. Measurement of circulating peptides is increasingly used to identify heart failure and sudden cardiac death. Another biomarker under intensive study as a risk factor is lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]), which has been identified from genetic studies as a causal link to MI; niacin has been shown to reduce the level of Lp(a) in some individuals (Hall, 2010).

Genetic risk factors for CAD and other cardiac disorders have been identified and are undergoing extensive study (Judge, 2012). Genetic studies have created a burgeoning body of knowledge about genetic mutations associated with risk factors such as CRP and possible pathways linking inflammatory processes with CAD (Kim et al, 2011; Roberts and Stewart, 2012a). Genetic risk variants mediate their risk in multiple ways; researchers have discovered that there are more unknown mechanisms than known mechanisms such as those associated with hypertension or lipids (Roberts and Stewart, 2012b). Soon an integral component of the preoperative assessment likely will include a genetic profile.

The risk for complications and major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) after cardiac surgery also appears to vary somewhat depending on gender (Hillis et al 2011; Newby and Douglas, 2012; Wenger, 2012). Investigations of risk factors in men and women for sternal wound infection have identified three significant risk factors that occur at significantly different rates in men and women: smoking, use of a single IMA, and age more than 70 years. Smoking and the use of a single IMA for bypass grafting are more common risk factors in men compared with women; women tend to be older than men at the time of surgery (Newby and Douglas, 2012). Fewer MACEs arose in women undergoing coronary bypass surgery without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB)—“off-pump” procedures—compared with surgery with CPB; however, malignant ventricular dysrhythmias (e.g., ventricular tachycardia), a calcified aorta, and preoperative renal failure are poor prognostic signs in women (Newby and Douglas, 2012). These findings should be incorporated into patient and family teaching plans with recommendations for lifestyle changes as indicated.

In addition to health status and risk factors, the perioperative nurse reviews patient medication history with particular attention to vasoactive drugs, anticoagulants, and other medications that can affect surgery. Nurses should note that patients taking aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs (such as 2b/IIIa inhibitors) may require intraoperative replacement of platelets. Lipid-lowering drugs (statins) have shown cardiovascular benefits, but in high doses (i.e., 80 mg, compared to moderate doses of 40 mg), they have been associated with new onset diabetes mellitus (Preiss et al, 2011). Patients taking herbal medicines may be at risk for increased bleeding, hypoglycemia, or other complications, depending on the specific side effects of some herbal drugs (see Chapter 30).

Patient knowledge and understanding of cardiovascular disease and related risk factors and their effect on functional, physiologic, and psychologic status should also be part of the perioperative nursing assessment. The patient's personal strengths, external resources, and coping strategies are important subjects to consider. The perioperative nurse also notes any cultural, ethnic, spiritual, or religious beliefs that appear relevant to perioperative patient care.

Physical Examination.

Physical assessment provides the perioperative nurse with baseline information about potential problems that might require intervention. Normal, age-specific changes in very young and elderly populations must be differentiated from pathologic conditions. Chapters 26 and 27 provide extensive age-related considerations.

In addition to age-specific changes, a growing number of adults with acquired heart disease underwent surgery in childhood to repair congenital cardiac lesions (Webb et al, 2012). For example, patients with a previous Blalock-Taussig shunt for tetralogy of Fallot (see Chapter 26) may have altered pulmonary and subclavian artery anatomy. Likewise, patients with a mechanical closure device inserted for an atrial septal defect may be at risk for endocardial injury if the heart is retracted or otherwise manipulated too forcefully. The nurse must be aware that anatomic anomalies associated with the original congenital defect, or its subsequent repair, may mandate alteration of the current surgical plan. Consultation with the surgeon can alert the cardiac team to anticipate different anatomy (and surgical landmarks), special supplies and prosthetic materials, and potential complications.

Before beginning a review of systems, it is helpful to assess the patient's functional capacity. How are activities of daily living accomplished? What are the barriers that make independent living difficult? How are activities performed when there are disabilities? What support systems are available? What educational resources are available? These and other questions will alert the clinician to the need for referrals and other resources to help the patient achieve optimal outcomes.

A systems review often starts with the skin. The appearance of the skin offers clues to cardiovascular status. Dryness, coolness, diaphoresis, paleness, edema, poor capillary refill, bruising, and petechiae may reflect impaired cardiovascular function. Visual problems and headaches may relate to inadequate cardiac output, atherosclerotic disease, peripheral vascular disease, aortic valve stenosis, or medications such as digitalis. The presence of chronic or local infection must be identified; if untreated, these are potential sources of postoperative infection. Nutritional status assessment (including metabolic syndrome) helps to determine increased risk for infection, skin breakdown, impaired wound healing, and other complications.

The patient's level of consciousness, memory, comprehension, and emotional status require assessment. Confusion, restlessness, slurred speech, numbness, and paralysis may signal impaired perfusion. The perioperative nurse should note their presence preoperatively and communicate this to nurses receiving the patient postoperatively.

During respiratory assessment the perioperative nurse should note the use of accessory muscles or nostril flaring and should auscultate breath sounds. Adventitious sounds such as crackles and wheezes may point to pulmonary edema. Orthopnea, shortness of breath, or dyspnea may require elevation of the head of the stretcher and assistance during transfer onto the OR bed. If the patient is receiving oxygen, the flow rate and method of administration should be observed.

Alleviating pain is a prime consideration in the care of the cardiovascular patient because pain is a myocardial stressor. A patient with angina may arrive in the OR after nitroglycerin tablets have been administered or transdermal patches applied. Cold also increases the workload of the heart because the shivering that accompanies chilling elevates the metabolic rate; the patient should be kept warm.

Heart sounds, murmurs, and friction rubs provide clues to congenital, ischemic, valvular heart disease, or pericarditis. The patient may experience palpitations. Apical, radial, and femoral pulses also reflect cardiac function, and their rate, rhythm, and quality should be determined. The presence of cyanosis or peripheral edema should be noted.

Blood pressure is an important assessment consideration. The hypertensive patient may have left ventricular hypertrophy, and the hypotensive patient may display changes in neurologic, gastrointestinal, and renal function. Blood pressures should be checked bilaterally. Unequal pressures in the arms may be a contraindication for the use of the IMA as a bypass graft on the side of the lower blood pressure, where perfusion may not be optimal. Radial and ulnar artery pulses should be checked bilaterally when the radial artery is to be used as a bypass graft. Patients with dissections or aneurysms may have unequal carotid, femoral, brachial, or radial artery blood pressures when the lesion occludes one or more of these vascular branches.

Cardiac function affects all the body's organ systems; therefore, assessment of the patient should be comprehensive whenever possible. A thorough assessment also alerts the physician and perioperative nurse to the need for special diagnostic tests and laboratory procedures.

Diagnostic Studies.

Most patients referred for surgery have had clinical evaluations, including invasive and noninvasive studies (Box 25-3). After the history and physical assessment, a resting electrocardiogram (ECG) follows. An exercise ECG (stress test) is often undertaken because ST-segment changes indicating myocardial ischemia may be apparent only during or after exercise. In patients with intractable dysrhythmias, electrophysiology (EP) studies may help locate irritable atrial or ventricular foci that can be surgically ablated, excised, or controlled with pharmacologic therapy. EP studies also may determine the need for internal defibrillators or antitachycardia devices. Bradycardia may indicate the need for pacemaker insertion.

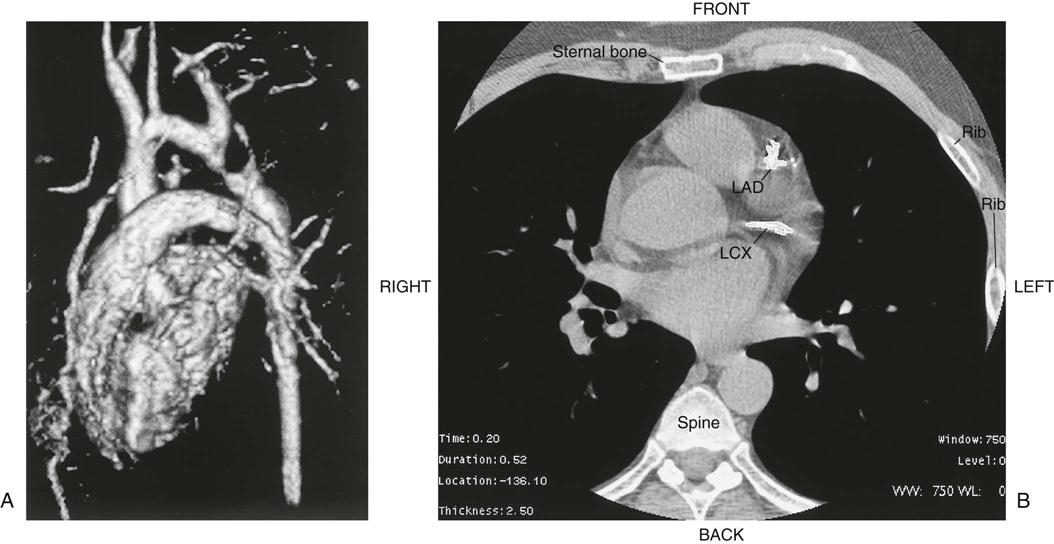

Chest radiography provides information about the size of the cardiac chambers, thoracic aorta, and pulmonary vasculature as well as the presence of calcium in valves, pericardium, coronary arteries, and aorta (Figure 25-8). Lateral chest radiographs of patients with prior sternal surgery show the chest wires and extent of pericardial adhesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enables assessment of myocardial viability and also can image vascular structures with MRI angiograms that provide great clarity (Figure 25-9, A). In patients with suspected aortic or other vascular abnormalities, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with intravenous injection of a contrast medium creates x-ray serial “slices” of the body area under study (see Figure 25-9, B). CT angiography is especially useful to image the aorta and the great vessels. CT images of the coronary arteries are used increasingly to identify areas of coronary calcification (shown in Figure 25-9, B), a recognized CV risk factor. One study demonstrated the value of coronary artery calcium scoring to identify patients who may be asymptomatic for CAD, but are at risk for increased mortality (Tota-Maharaj et al, 2012).

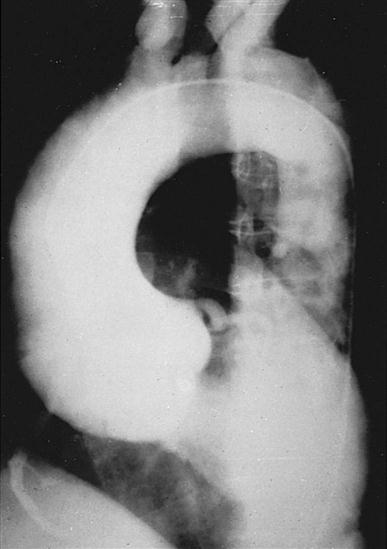

CT scans may be contraindicated in very unstable patients because their position in the tubelike scanner makes patient access difficult. Less frequently performed is arteriography with radiographic contrast dye to determine the size and location of the lesion and the site of the intimal tear in aortic dissections (Figure 25-10); digital subtraction angiography (DSA) provides clear images and requires less contrast material.

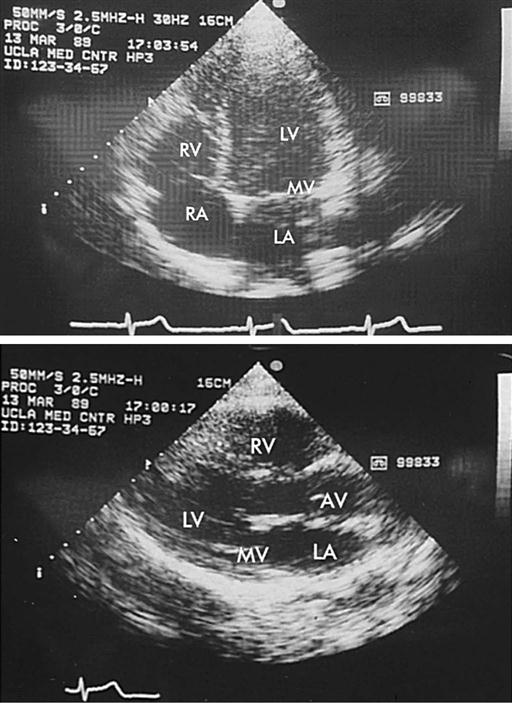

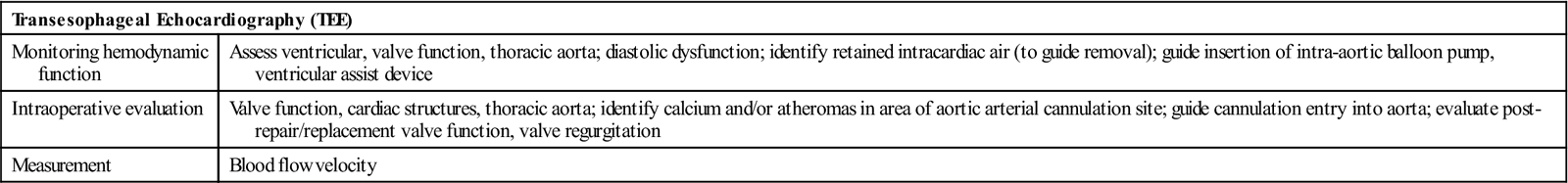

Echocardiography is a noninvasive test that evaluates both the structure and the function of the heart by transmitting sound waves to the heart and measuring those sound waves reflected back to the transducer (Figure 25-11). Sound waves undergo processing by the transducer, which creates visual images of the structure's movements. This test enables assessment of ventricular and valvular function before, during, and after surgery, and determination of the degree of valvular stenosis or regurgitation. It can also demonstrate a tumor, thrombus, or air in the ventricular or atrial cavities. Two-dimensional and color-flow Doppler techniques have greatly enhanced functional assessment of valvular performance and carotid artery stenoses. Echocardiography is the gold standard to diagnose mitral stenosis, and its use to assess other valvular disorders and congenital heart disease is widespread. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) also allows evaluation of the effectiveness of valve repairs and other surgical procedures (Table 25-1).

TABLE 25-1

| Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) | |

| Monitoring hemodynamic function | Assess ventricular, valve function, thoracic aorta; diastolic dysfunction; identify retained intracardiac air (to guide removal); guide insertion of intra-aortic balloon pump, ventricular assist device |

| Intraoperative evaluation | Valve function, cardiac structures, thoracic aorta; identify calcium and/or atheromas in area of aortic arterial cannulation site; guide cannulation entry into aorta; evaluate post-repair/replacement valve function, valve regurgitation |

| Measurement | Blood flow velocity |

Modified from Bonow RO et al, editors: Braunwald's heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders; Nussmeier NA et al: Anesthesia for cardiac surgical procedures. In Miller RD et al, editors: Miller's anesthesia, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2009, Churchill Livingstone.

Radionuclide imaging illustrates wall motion and blood flow through the heart and quantifies cardiac function. Patients generally tolerate these noninvasive techniques well, especially when they may be too unstable to withstand a cardiac catheterization. These techniques may also serve as a complement to catheterization.

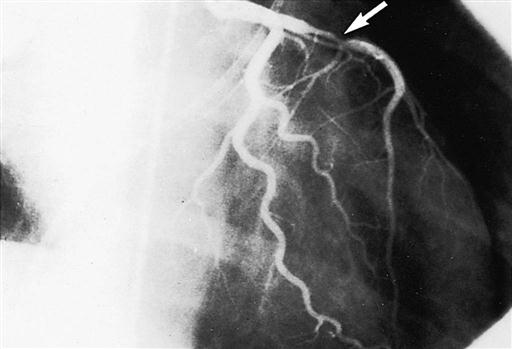

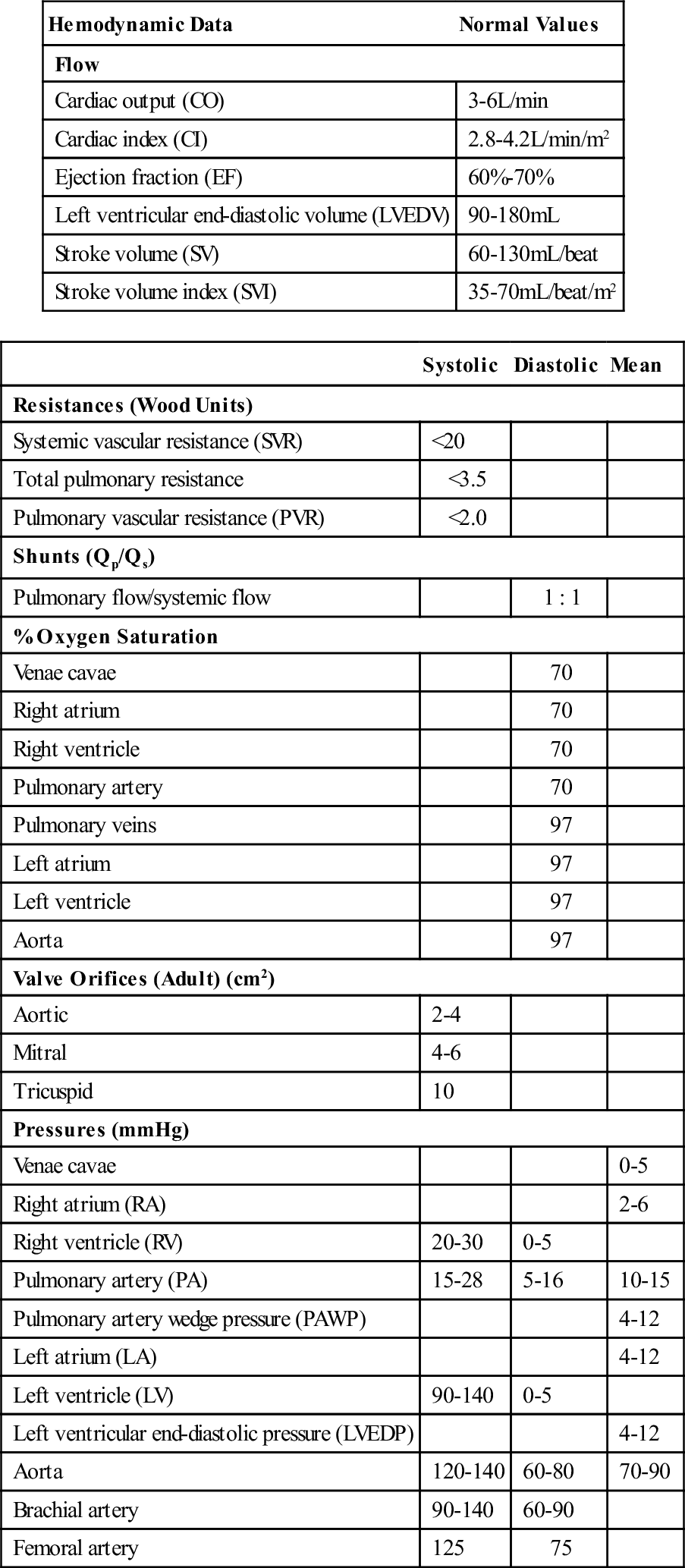

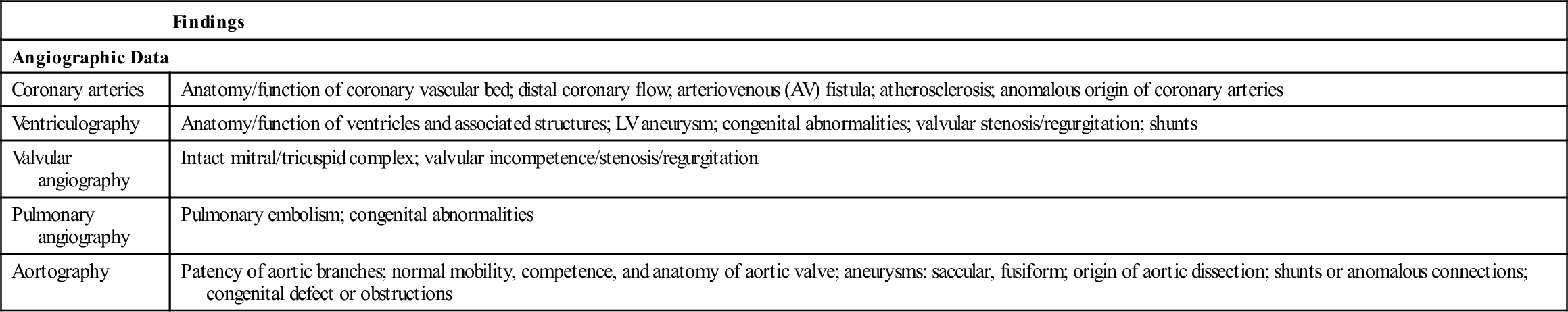

Cardiac catheterization provides definitive information about the extent and location of ischemic heart disease, acting as an adjunct to echocardiography to diagnose valvular heart disease (Kern, 2011). A radiopaque plastic catheter is inserted retrograde through the aortic valve into the left side of the heart by a percutaneous puncture or a cutdown to the vessels of the brachial artery (Sones technique) or the femoral artery (Judkins technique). The right side of the heart is approached percutaneously by the superior or inferior vena caval route. To perform coronary angiography that demonstrates intracoronary anatomy, a contrast medium is injected into the coronary ostia. Obstructions (Figure 25-12), flow, and distal perfusion are assessable. Ventriculography illustrates contractile weaknesses of the ventricles as well as shunting and regurgitation of blood. These studies enable assessment of the degree of myocardial dysfunction and planning for interventions such as CABG, valve repair or replacement, repair of congenital anomalies, and cardiac transplantation. The cardiologist can compute the orifice of a stenosed valve or determine the degree of regurgitation of an incompetent valve.

Ventricular, atrial, and pulmonary pressures are recorded, and cardiac output and ejection fraction estimated (Box 25-4 and Table 25-2). Oxygen saturation of cardiac chambers and the ratio of pulmonary to systemic blood flow (Qp/Qs) are calculated for patients with shunts and congenital or acquired defects. Cinearteriograms record the movement of the heart, and cut films or digitized versions of the cines may be displayed during surgery.

TABLE 25-2

| Hemodynamic Data | Normal Values |

| Flow | |

| Cardiac output (CO) | 3-6 L/min |

| Cardiac index (CI) | 2.8-4.2 L/min/m2 |

| Ejection fraction (EF) | 60%-70% |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) | 90-180 mL |

| Stroke volume (SV) | 60-130 mL/beat |

| Stroke volume index (SVI) | 35-70 mL/beat/m2 |

| Systolic | Diastolic | Mean | |

| Resistances (Wood Units) | |||

| Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) | <20 | ||

| Total pulmonary resistance | <3.5 | ||

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) | <2.0 | ||

| Shunts (Qp/Qs) | |||

| Pulmonary flow/systemic flow | 1 : 1 | ||

| % Oxygen Saturation | |||

| Venae cavae | 70 | ||

| Right atrium | 70 | ||

| Right ventricle | 70 | ||

| Pulmonary artery | 70 | ||

| Pulmonary veins | 97 | ||

| Left atrium | 97 | ||

| Left ventricle | 97 | ||

| Aorta | 97 | ||

| Valve Orifices (Adult) (cm2) | |||

| Aortic | 2-4 | ||

| Mitral | 4-6 | ||

| Tricuspid | 10 | ||

| Pressures (mm Hg) | |||

| Venae cavae | 0-5 | ||

| Right atrium (RA) | 2-6 | ||

| Right ventricle (RV) | 20-30 | 0-5 | |

| Pulmonary artery (PA) | 15-28 | 5-16 | 10-15 |

| Pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) | 4-12 | ||

| Left atrium (LA) | 4-12 | ||

| Left ventricle (LV) | 90-140 | 0-5 | |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) | 4-12 | ||

| Aorta | 120-140 | 60-80 | 70-90 |

| Brachial artery | 90-140 | 60-90 | |

| Femoral artery | 125 | 75 | |

| Findings | |

| Angiographic Data | |

| Coronary arteries | Anatomy/function of coronary vascular bed; distal coronary flow; arteriovenous (AV) fistula; atherosclerosis; anomalous origin of coronary arteries |

| Ventriculography | Anatomy/function of ventricles and associated structures; LV aneurysm; congenital abnormalities; valvular stenosis/regurgitation; shunts |

| Valvular angiography | Intact mitral/tricuspid complex; valvular incompetence/stenosis/regurgitation |

| Pulmonary angiography | Pulmonary embolism; congenital abnormalities |

| Aortography | Patency of aortic branches; normal mobility, competence, and anatomy of aortic valve; aneurysms: saccular, fusiform; origin of aortic dissection; shunts or anomalous connections; congenital defect or obstructions |

Modified from Pagana KD, Pagana TJ: Mosby's diagnostic and laboratory test reference, ed 11, St Louis, 2012, Mosby; Bonow RO et al, editors: Braunwald's heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders; Kern MJ: Cardiac catheterization handbook, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders; Nussmeier NA et al: Anesthesia for cardiac surgical procedures. In Miller RD et al, editors: Miller's anesthesia, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2009, Churchill Livingstone.

The cardiac catheterization laboratory also performs percutaneous coronary interventional (PCI) therapies for evolving and acute MIs (Morrow and Boden, 2012). Coronary thrombolysis with fibrinolytic drugs can dissolve fresh blood clots and reopen (i.e., recanalize) the artery; prescription of antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, dipyridamole, and clopidogrel often can block platelet aggregation that otherwise can lead to restenosis. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) followed by insertion of intracoronary (bare metal or drug-eluting) stents is often performed to dilate and maintain the patency of the recanalized artery. In many instances these interventions may obviate the need for surgical bypass grafting, although the progressive nature of CAD may eventually lead to patients requiring surgical revascularization.

EP studies enable diagnosis of conduction disturbances and allow therapeutic interventions, such as radiofrequency or cryologic ablation of foci producing atrial fibrillation or accessory pathways seen in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Insertion of a pacemaker for bradydysrhythmias or an internal cardioverter defibrillator for ventricular tachydysrhythmias commonly occurs in EP laboratories. Insertion of these devices, however, may require an OR when percutaneous access is unfeasible or when concomitant cardiac surgery is performed.

Laboratory Tests.

Preoperative laboratory tests enable assessment of physiologic function (see Appendix A). Hematologic tests include a detailed coagulation profile to uncover hemorrhagic disorders. In patients who have been taking aspirin or dipyridamole, platelet activity is decreased; this alerts the perioperative nurse to anticipate prolonged bleeding, which will require replacement. After determination of the patient's blood type, an appropriate order to the blood bank follows. The blood undergoes testing for viral contamination and for cold antibodies that could produce agglutination of the patient's blood during surgery and after patient cooling to hypothermic temperatures. A monitored blood refrigerator stores blood brought to the OR suite before surgery. Although autotransfusion techniques have reduced the use of blood bank products, the occasional, emergent need for blood requires immediate availability of blood bank packed red blood cells.

Liver and kidney function test results may be abnormal in patients with chronic heart failure, possibly because congestion related to right heart failure in the former and reduced blood flows in the latter occur with some frequency. Progressive improvement in hepatic and renal function often follows successful operative intervention. The use of statins and other cholesterol-reducing drugs that can adversely impair hepatic function also alerts the nurse to review liver function laboratory results (Pagana and Pagana, 2012). Blood glucose levels require testing, monitoring, and control, especially in patients with impaired glucose metabolism and both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Additional perioperative laboratory examinations may include arterial blood gases and enzyme biomarkers of myocardial damage (e.g., troponin I and troponin T; creatine kinase MB isoenzyme, known as MB bands), particularly with persistent angina (Canty, 2012). Troponin levels are the focus of a revised definition of MI. This new definition incorporates specific troponin levels and at least one of the following criteria: symptoms of ischemia, new ST-/T-wave changes or left bundle branch block on the ECG, pathologic Q waves on ECG, evidence of loss of viable myocardium or regional wall motion on diagnostic images, and documentation of an intracoronary thrombus (Thygesen et al, 2012). This new definition differentiates between infarction and injury. The distinction is important to plan treatment; it also may affect the ability to obtain insurance and participate in secondary prevention (Mitka, 2012).

Pulmonary function tests may help determine baseline data and plan postoperative care. The use of extracorporeal circulation and associated inflammatory responses, as well as the stasis of lung secretions that accompany prolonged surgery, may impair postoperative respiratory function.

Nursing Diagnosis

After a comprehensive review of individual patient data, the perioperative nurse identifies relevant nursing diagnoses, from which the perioperative plan for patient care derives (Sample Plan of Care on pages 944-945).

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of patients undergoing cardiac surgery might include the following (Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN], 2013; Petersen, 2011; Seifert, 2008, 2013):

• Decreased Cardiac Output related to emotional (fear), sensory (pain), or physiologic (electrical, mechanical, or structural) factors

• Risk for Infection related to surgical incision(s), catheters and intravascular lines, and altered cardiac function

• Risk for Perioperative Positioning Injury related to, for example, preexisting musculoskeletal malformation, insecure attachment to OR bed

• Risk for Contamination related to break in aseptic technique, preexisting infection, self-contamination (e.g., contamination by patient's own groin material)

• Risk for Bleeding related to surgical incision(s), tissue dissection, altered coagulation function, and inadvertent hypothermia

• Deficient Knowledge related to physiologic effects of the cardiac disorder, proposed surgical procedures, and immediate perioperative events

• Risk for Impaired Tissue Integrity (myocardial, peripheral, renal, and cerebral) related to surgery, hypothermia, CPB, or surgical particulate or air emboli

Outcome Identification

Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses could include:

• The patient's cardiac function will be consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively as evidenced by hemodynamic indicators (blood pressure, oxygenation, ECG) within expected range; warm, dry skin; and urine output more than 30 mL/hr.

• The patient will be free from signs and symptoms of infection at the surgical or other incisional sites as evidenced by absence of redness, edema, purulent incisional drainage, or untoward postoperative temperature elevation.

• The patient will be free from signs and symptoms of injury related to surgical position as evidenced by the absence of acquired neuromuscular impairment and tissue necrosis.

• The patient will be free from signs and symptoms of contamination as evidenced by maintenance of aseptic technique, timely treatment for preexisting infection, separation of “clean” and “dirty” areas of the field, and confirmation of integrity of implants (e.g., prosthetic heart valves, vascular grafts).

• The patient will be free from excessive bleeding as evidenced by chest tube drainage less than 100 mL/hr, dressings dry and intact, normal coagulation function studies (or undergoing replacement treatment for deficient clotting factors), and normal body temperature.

• The patient will demonstrate knowledge of the physiologic responses to the cardiac disorder (at his or her level of understanding), the proposed surgical treatment, and the immediate perioperative events as evidenced by verbalization of disease state, purpose of surgery, sequence of events, anticipated outcomes, and recovery process.

• The patient's myocardial, peripheral, renal, and cerebral tissue integrity will be adequate or improved as evidenced by absence of new electrocardiograph manifestations of infarction, the presence of palpable peripheral pulses, adequate urine output, and a clear or improving sensorium postoperatively.

Additional nursing diagnoses based on individual patient assessment should have a corresponding outcome statement. The outcome should be measurable, with criteria by which to evaluate achievement. For example, for the outcome “The patient's cardiac function will be consistent with or improved from baseline levels established preoperatively as evidenced by blood pressure within expected range; warm, dry skin; and urine output more than 30 to 50 mL per hour,” the perioperative nurse might identify criteria such as vital signs and hemodynamic status consistent with or better than preoperative parameters; fluid and electrolyte balance consistent with preoperative levels; adequate urine output; normal temperature and pink mucosa; absence of rate, rhythm, or conduction disturbances; absence of iatrogenic injury to the heart; and normal levels of clotting parameters. Each criterion evidences achievement of the outcome. Outcome evaluations should be documented in the perioperative record. Some outcome achievements will occur after the surgical procedure; others will require ongoing evaluation in the postoperative period for adequate measurement. The evaluation section affirmatively mandates ongoing goal measurement by the use of the word “will” rather than stating the outcome as “having been” achieved.

The nursing interventions in the Sample Plan of Care incorporate data elements from AORN's Perioperative Nursing Data Set (PNDS) (Petersen, 2011). With increasing emphasis on correlating patient outcomes with clinical interventions, the PNDS is a valuable resource by which to demonstrate the nurse's ability to influence positive patient outcomes.

Planning

After establishing the diagnoses and outcomes, the perioperative nurse devises a plan of care (see Sample Plan of Care) to achieve the goals set. Patient and family needs, elicited from interviews when possible, are integrated into the planning. The perioperative nurse should then identify criteria specific to the patient for each of the stated outcomes in the Sample Plan of Care.

Implementation

Additional considerations may prove useful to implement the perioperative plan of care for patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Safety Considerations.

The safety of the perioperative patient is a primary responsibility of the nurse. Among important National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs) is compliance with “briefing,” “debriefing,” and other components of The Joint Commission's (TJC) Universal Protocol (TJC, 2013). The protocol consists of a checklist that addresses critical components (i.e., patient identification, confirmation of surgical procedure, availability of anticipated devices such as heart valves) that form the basis of a safe operation. Of special importance is promotion of a work culture that encourages asking questions and sharing information.

Equipment must function properly and undergo routine testing by the biomedical engineering department. Supplies should be used according to manufacturers' instructions, and instruments should be regularly scrutinized to ensure that there are no burrs that could injure tissue, that the jaws of vascular and other clamps align properly, and that small items are accounted for at the end of surgery. Toxic material, such as the glutaraldehyde storage solution of bioprosthetic valves, should be thoroughly rinsed before implantation. Monitoring aseptic practices of team members as well as visitors is important to safety.

Staff safety is also important. Protective personal equipment should be worn consistently and properly. Gloves should be used by personnel whenever contact may occur with blood or other body fluids. Injury from inadvertent effects of electrical, chemical, and other potentially hazardous materials within the OR can be minimized by reinforcing safe practices.

Special Facilities.

The OR must be large enough to accommodate bulky, highly specialized equipment while maintaining aseptic technique. Multiple electrical outlets, auxiliary lighting, and additional suction outlets should be available. Ceiling-mounted, mobile booms for housing electrosurgical units (ESUs), headlight sources, suction, medical gases, electrical outlets, and other items can reduce floor clutter and enhance the safety of the environment for patients and staff.

A growing number of hybrid suites have been designed that combine the traditional surgical controlled environment and the fluoroscopic imaging capabilities of interventional cardiology laboratories. A typical hybrid procedure may consist of a surgical coronary anastomosis under direct vision or with a robot, combined with percutaneously inserted coronary artery stents under fluoroscopy. Endovascular aneurysm (of the thoracic and abdominal aorta) and percutaneous aortic valve insertion via fluoroscopic imaging are among other procedures performed in hybrid ORs (Kpodonu, 2012).

Instrumentation and Equipment.

The basic setup described for thoracic procedures (see Chapter 23) is used, along with specialized cardiovascular instruments and equipment.

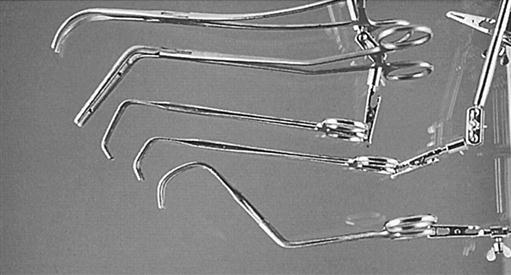

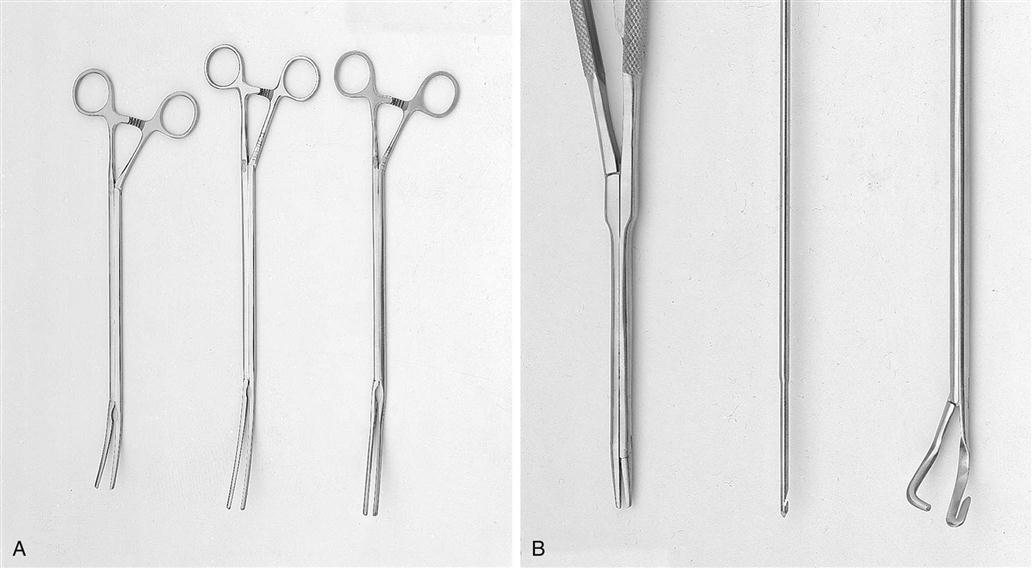

Vascular clamps, designed to occlude blood flow partially or completely, must be maintained in good condition if they are to prevent fracture of the delicate tunica intima of the blood vessels and still retain their specific holding qualities. There are many variations in construction of vascular instruments. Jaws may consist of single or double rows of fine, sharp, or blunt teeth or special crosshatching or longitudinal serrations. The working angles of the clamps also vary. All clamps are designed to hold vessels securely, without causing trauma (Figure 25-13).

Minimally invasive procedures require special instrumentation to access the heart through smaller incisions in the anterior and lateral aspects of the chest wall (Figure 25-14). Retractors, dissecting instruments, suturing devices, coronary artery stabilizers, and vascular clamps are available.

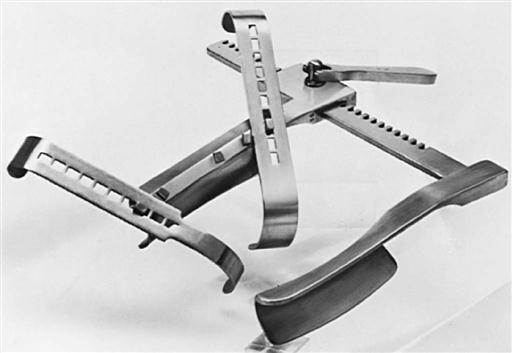

Sternal and rib retractors are available to meet specific needs. IMA retractors expose the retrosternal artery bed by elevating the sternal border (Figure 25-15). Some sternal retractors have attachments to provide improved exposure of the LA during mitral valve replacement (MVR) (Figure 25-16). Handheld retractors can also expose the left or RA or the aortic root. Special rib spreaders provide exposure for mini-thoracotomy procedures. Coronary artery stabilizer systems with left ventricular apical suction retractors are widely used for beating heart coronary bypass surgery (described later).

Other equipment commonly used (or available) for cardiac surgery may include the following:

• Irrigation fluid cooling/warming machine

• Autotransfusion/cell saver system

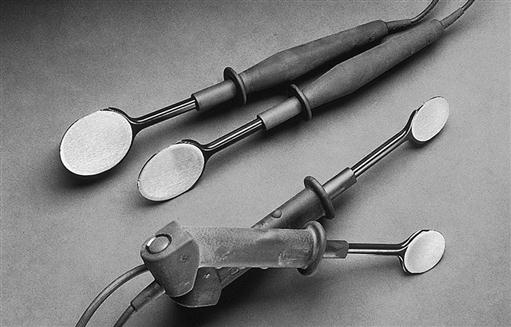

• Direct current (DC) defibrillator with internal paddles (Figure 25-17) and adhesive external pads

• Thermia unit (mattress or forced-air warming)

• External and internal pulse pacemaker generator (single and dual chamber)

• Epicardial pacemaker leads (temporary)

• Fiberoptic headlight and light source

• Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)

• Mechanical ventricular assist devices (VADs)

• Cryothermal energy ablation source (for atrial fibrillation surgery)

• Radiofrequency energy ablation source (for atrial fibrillation surgery)

• Ultrasonic cutting/coagulation device (Harmonic scalpel)

Lasers (for transmyocardial laser revascularization) and robots (for valve repair) may also be found in a cardiac OR.

Suture Materials.

A variety of nonabsorbable cardiovascular sutures with atraumatic needles are available from most suture manufacturers. Synthetic sutures of Teflon, Dacron, polyester, or polypropylene are usually selected for insertion of prostheses and for vascular anastomoses. Most sutures are double armed with a needle on each end. Given the numerous stitches required for prosthetic valve repair and replacement, alternately colored suture and slotted, numbered suture holders may help avoid confusion. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sutures can be used for replacement of mitral valve chordae. Vessel loops and umbilical tapes are commonly used to identify and to retract blood vessels and other structures. Wire (monofilament or twisted cable) commonly is used to approximate the sternum (Figure 25-18), with plastic, metal, or nylon bands occasionally added to reinforce fragile bone. Skin staplers may be used to close skin incisions; a staple remover must accompany the patient to the postanesthesia area if staples have been used to close the chest.

Supplies.

The following supplies are used in most cardiac procedures. Depending on the surgeon's preference, other items may be added or substituted.

• Rubber shods (placed on the tips of hemostats to protect suture clamped by the hemostat)

• Pill sponges (small gauze dissectors; also called peanuts, pushers, kitners)

• Various-sized Silastic or polyvinyl chloride tubing

• Foot-controlled and hand-controlled ESU pencils, ultrasonic scalpel

• Adapters, connectors, stopcocks

• Extra syringes and needles for injections, infusions, and blood samples

• Sterile marking pen to identify anastomotic sites and mark grafts

• Cotton gloves (worn by assistant to retract heart and expose target coronary artery); some surgeons prefer a sling to pull up the heart to expose the coronary arteries

• Suture organizer (to keep valve sutures in correct order)

• Disposable vascular (bulldog) clamps

• Coronary occluders and stabilizers

• Chest tubes, chest drainage system

• Femoral arterial blood pressure supplies (hypodermic needle, guidewire, stopcocks, pressure tubing)

• IABP insertion supplies (hypodermic needle, guidewire, vascular dilators, stopcocks, pressure tubing, IABP catheter)

• CPB and myocardial protection cannulae, tubing, connectors, stopcocks

Prosthetic Material.

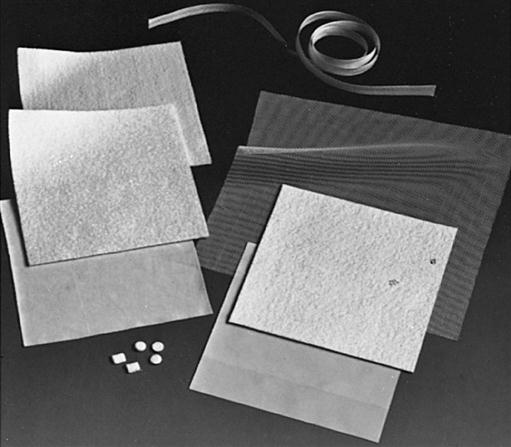

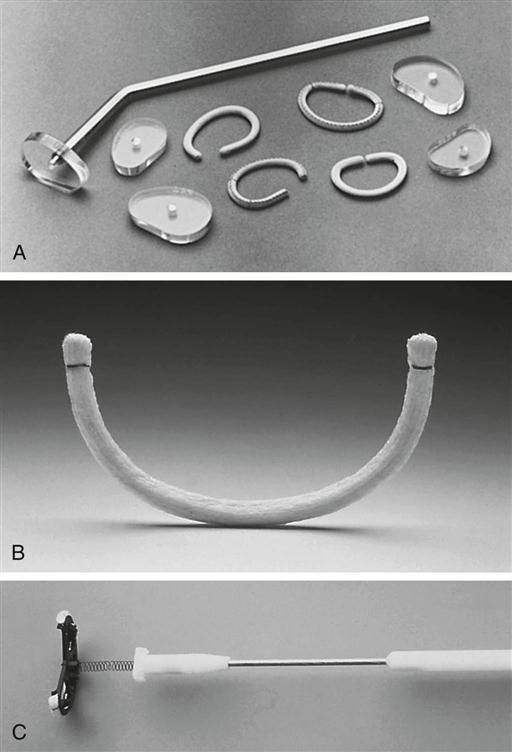

In addition to these general supplies, special supplies are needed to repair or replace cardiovascular structures. Intracardiac patches, heart valves, and synthetic grafts should be handled with care to prevent damage or the introduction of foreign materials. Teflon, a fluorocarbon fiber, and Dacron, a polyester fiber, come in a variety of meshes, fabrics, felts, tapes, and sutures, and it is possible to combine them with other materials in prosthetic heart valves (Figure 25-19).

Teflon patches are made in a variety of forms for intracardiac and outflow tract use. Varying degrees of firmness, thickness, and porosity are available for specific uses. Low reactivity, strength retention, and tissue acceptance are important considerations when selecting such patches.

Use of Dacron arterial tube grafts is common in cardiac surgery, although reinforced expanded PTFE grafts are also available. There are two types of Dacron grafts: knitted and woven. Woven prosthetic grafts are usually used when the patient has been fully heparinized because the interstices of woven grafts are tighter than those in knitted grafts and bleeding is usually less. Compared with woven grafts, the advantages of knitted grafts are that they do not fray as readily, they are easier to handle, and they reendothelialize more quickly. Grafts come in a variety of sizes and may be straight or bifurcated (Figure 25-20). Knitted and woven grafts impregnated with collagen to reduce interstitial bleeding are useful in the thoracic aorta and do not have to be preclotted, even when the patient is fully heparinized for cardiopulmonary bypass. Graft sizers are available to determine correct size.

Specially designed tube grafts for the aortic arch incorporate prosthetic branches for the head vessels (bracheocephalic, left common carotid, and subclavian arteries); and tube grafts for replacement of the aortic root and ascending aorta are available with preformed sinuses of Valsalva incorporated into the prosthesis (David, 2009).

Endovascular, expandable stented tube grafts are available for both the abdominal aorta and the descending portion of the thoracic aorta (Figure 25-21). The endovascular graft is inserted percutaneously into the femoral artery and advanced to the desired position in the abdominal or descending thoracic aorta, where the prosthesis is opened, implanted, and secured (Thompson and Bertling, 2009; Tinkham, 2009).

Valve Prostheses.

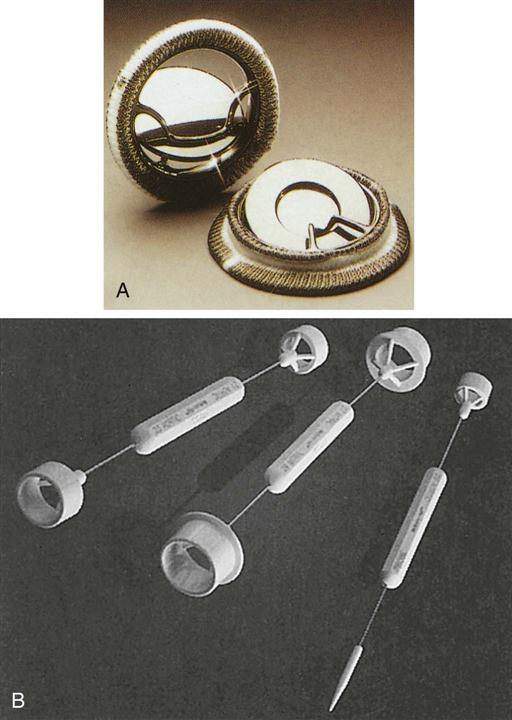

Valve prosthesis selection depends on multiple factors: hemodynamics, thromboresistance, durability, ease of insertion, anatomic suitability, and patient acceptability; cost, patient outcome, and value are also important (Manji et al, 2012; Rahimtoola, 2010, 2011). Most mechanical prostheses use a tilting disk design. The ball-and-cage prosthesis was the first mechanical valve implanted in the anatomic position but is no longer available. Prosthetic valves allow complete closure with slight regurgitation to prevent stasis of blood (Figures 25-22 to 25-24). Prosthetic valves are manufactured with an attached annular sewing ring (often made of Dacron). The surgeon places sutures into the native valve annulus and then into the prosthesis sewing ring. The sewing ring occupies space within the valvular orifice and may affect the amount of flow through the valve orifice. This is especially significant in the small aortic root (the location of the valve annulus). Aortic prostheses, especially in the smaller sizes (e.g., 21 mm), tend to have minimal sewing ring material to avoid taking up space so as to minimize cardiac reduction of cardiac output that can flow through the prosthetic orifice. When blood flow through the prosthetic valve fails to meet metabolic demands, a prosthesis-patient mismatch is said to exist (Daneshvar and Rahimtoola, 2012; Head et al, 2012; Rahimtoola, 2011). The deleterious effect of such a mismatch eventually produces deterioration of cardiac function. Surgeons, increasingly aware of the problem, select the prosthesis with the best hemodynamics for the patient. If a suitable prosthesis is unavailable, the surgeon may opt to perform a procedure to enlarge the aortic root in order to insert a larger, more hemodynamically suitable valve.

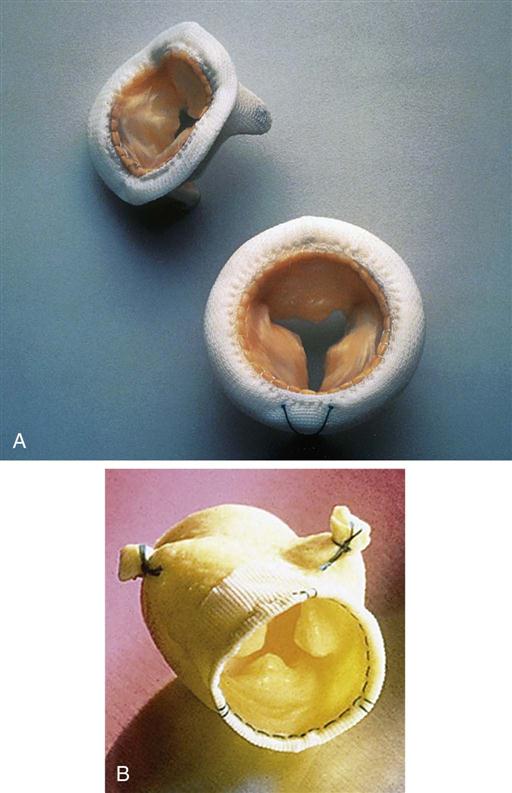

Bioprostheses derive from porcine, bovine, or equine tissue (Figures 25-25 to 25-27). Porcine valves consist of an aortic valve from a pig that can be sutured to a Dacron-covered stent (Figure 25-25, A); alternatively, the porcine aortic valve may be “stentless” (without a sewing ring) to enhance the hemodynamics, especially in patients with a small aortic root (see Figure 25-25, B). The bovine (calf) (see Figure 25-26) pericardial bioprosthesis is created by cutting leaflet-shaped pieces from the pericardium and sewing them onto a Dacron ring; more recently, a newer bovine pericardial prosthesis (Kocher et al, 2013) can be rapidly deployed by sliding the valve into position in the aortic annulus and inflating the frame to sit firmly in place (three commissural stitches also help to anchor the prosthesis). The equine (horse) (see Figure 25-27, A) pericardial prosthesis is created by cutting pieces of the pericardium, shaping the pieces into a tube, and attaching the prosthesis to a ring of Dacron material. The advantage of these biologic valves is that administration of long-term anticoagulants is not necessary in most patients. Obturators to size prosthetic valves as well as valve holders are specific to the prostheses (see Figures 25-24, B, and 25-27, B). Tables 25-3 and 25-4 compare mechanical and biologic prosthetic heart valves. Tissue-engineered heart valves may offer a future potential cure for valvular heart disease (Rahimtoola, 2011).

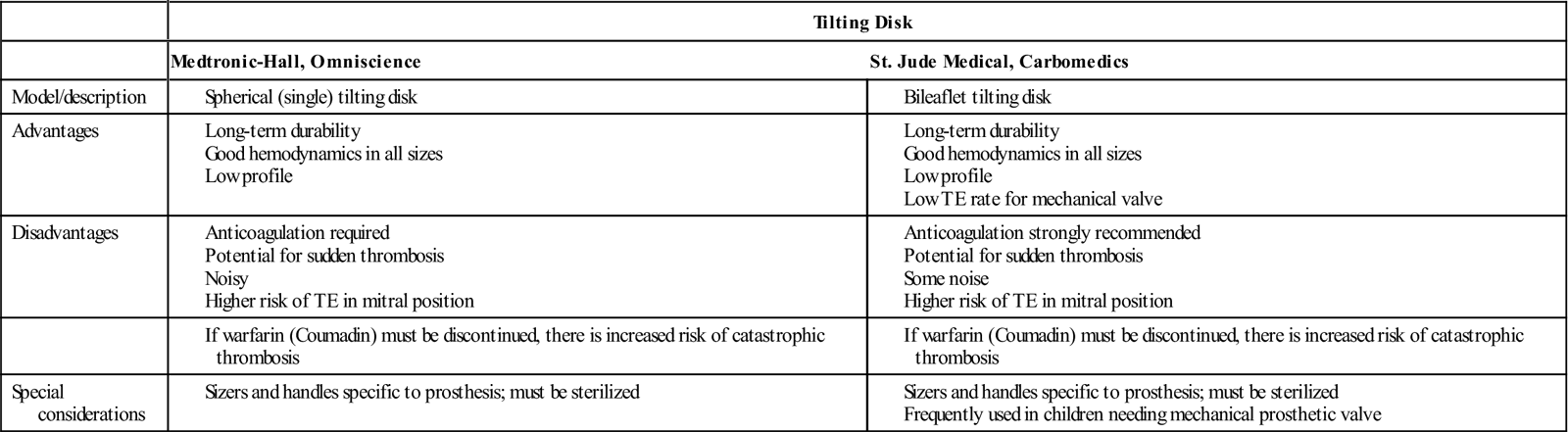

TABLE 25-3

Mechanical Valve Prostheses*

| Tilting Disk | ||

| Medtronic-Hall, Omniscience | St. Jude Medical, Carbomedics | |

| Model/description | ||

| Advantages | ||

| Disadvantages | ||

| Special considerations | ||

*All prostheses should be stored in a cool, dry, contamination-free area. Resterilization is no longer recommended. The Starr-Edwards ball-and-cage valve is no longer available; clinicians occasionally still may encounter a patient with a ball-and-cage valve.

Modified from Otto CM, Bonow RO: Valvular heart disease. In Bonow RO et al, editors: Braunwald's heart disease—a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders; Rahimtoola SH: Choice of prosthetic heart valve in adults: an update, J Am Coll Cardiol 55(22):2413–2426, 2010; Rahimtoola SH: The year in valvular heart disease, J Am Coll Cardiol 58(12):1197–1207, 2011.

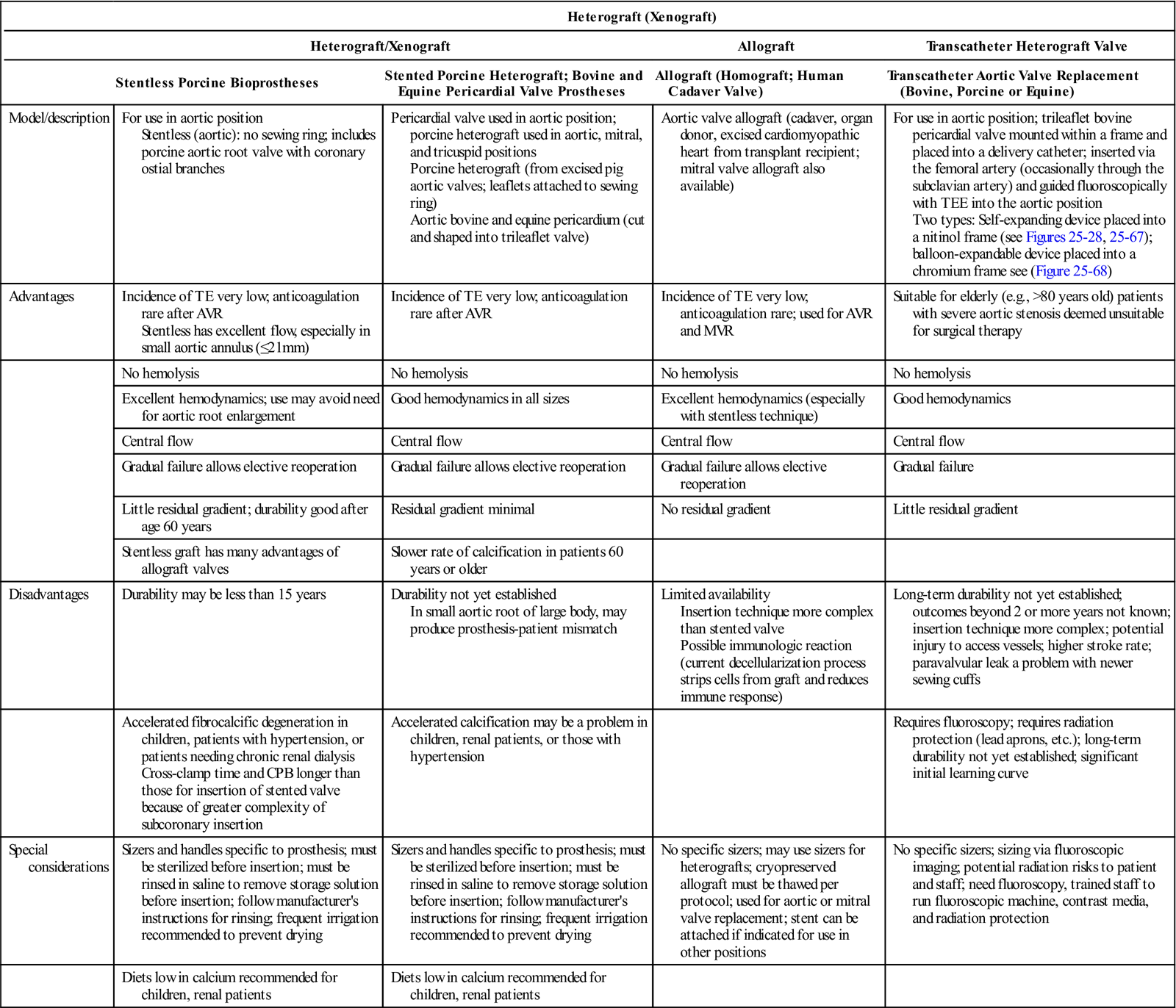

TABLE 25-4

| Heterograft (Xenograft) | ||||

| Heterograft/Xenograft | Allograft | Transcatheter Heterograft Valve | ||

| Stentless Porcine Bioprostheses | Stented Porcine Heterograft; Bovine and Equine Pericardial Valve Prostheses | Allograft (Homograft; Human Cadaver Valve) | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (Bovine, Porcine or Equine) | |

| Model/description | For use in aortic position Stentless (aortic): no sewing ring; includes porcine aortic root valve with coronary ostial branches |

Pericardial valve used in aortic position; porcine heterograft used in aortic, mitral, and tricuspid positions Porcine heterograft (from excised pig aortic valves; leaflets attached to sewing ring) Aortic bovine and equine pericardium (cut and shaped into trileaflet valve) |

Aortic valve allograft (cadaver, organ donor, excised cardiomyopathic heart from transplant recipient; mitral valve allograft also available) | For use in aortic position; trileaflet bovine pericardial valve mounted within a frame and placed into a delivery catheter; inserted via the femoral artery (occasionally through the subclavian artery) and guided fluoroscopically with TEE into the aortic position Two types: Self-expanding device placed into a nitinol frame (see Figures 25-28, 25-67); balloon-expandable device placed into a chromium frame see (Figure 25-68) |

| Advantages | Incidence of TE very low; anticoagulation rare after AVR Stentless has excellent flow, especially in small aortic annulus (≤21 mm) |

Incidence of TE very low; anticoagulation rare after AVR | Incidence of TE very low; anticoagulation rare; used for AVR and MVR | Suitable for elderly (e.g., >80 years old) patients with severe aortic stenosis deemed unsuitable for surgical therapy |

| No hemolysis | No hemolysis | No hemolysis | No hemolysis | |

| Excellent hemodynamics; use may avoid need for aortic root enlargement | Good hemodynamics in all sizes | Excellent hemodynamics (especially with stentless technique) | Good hemodynamics | |

| Central flow | Central flow | Central flow | Central flow | |

| Gradual failure allows elective reoperation | Gradual failure allows elective reoperation | Gradual failure allows elective reoperation | Gradual failure | |

| Little residual gradient; durability good after age 60 years | Residual gradient minimal | No residual gradient | Little residual gradient | |

| Stentless graft has many advantages of allograft valves | Slower rate of calcification in patients 60 years or older | |||

| Disadvantages | Durability may be less than 15 years | Durability not yet established In small aortic root of large body, may produce prosthesis-patient mismatch |

Limited availability Insertion technique more complex than stented valve Possible immunologic reaction (current decellularization process strips cells from graft and reduces immune response) |

Long-term durability not yet established; outcomes beyond 2 or more years not known; insertion technique more complex; potential injury to access vessels; higher stroke rate; paravalvular leak a problem with newer sewing cuffs |

| Accelerated fibrocalcific degeneration in children, patients with hypertension, or patients needing chronic renal dialysis Cross-clamp time and CPB longer than those for insertion of stented valve because of greater complexity of subcoronary insertion |

Accelerated calcification may be a problem in children, renal patients, or those with hypertension | Requires fluoroscopy; requires radiation protection (lead aprons, etc.); long-term durability not yet established; significant initial learning curve | ||

| Special considerations | Sizers and handles specific to prosthesis; must be sterilized before insertion; must be rinsed in saline to remove storage solution before insertion; follow manufacturer's instructions for rinsing; frequent irrigation recommended to prevent drying | Sizers and handles specific to prosthesis; must be sterilized before insertion; must be rinsed in saline to remove storage solution before insertion; follow manufacturer's instructions for rinsing; frequent irrigation recommended to prevent drying | No specific sizers; may use sizers for heterografts; cryopreserved allograft must be thawed per protocol; used for aortic or mitral valve replacement; stent can be attached if indicated for use in other positions | No specific sizers; sizing via fluoroscopic imaging; potential radiation risks to patient and staff; need fluoroscopy, trained staff to run fluoroscopic machine, contrast media, and radiation protection |

| Diets low in calcium recommended for children, renal patients | Diets low in calcium recommended for children, renal patients | |||

AVR, Aortic valve replacement; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MVR, mitral valve replacement; TE, thromboembolism; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography.

Modified from Gilard M et al: Registry of transcatheter aortic-valve implantation in high-risk patients, N Engl J Med 366(18):1705–1715, 2012; Kodali SK et al: Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement, N Engl J Med 366(18):1686–1695, 2012; Otto CM, Bonow RO: Valvular heart disease. In Bonow RO et al, editors: Braunwald's heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia. 2012, Saunders; Rahimtoola SH: Choice of prosthetic heart valve in adults: an update, J Am Coll Cardiol 55(22):2413–2426, 2010; Rahimtoola SH: The year in valvular heart disease, J Am Coll Cardiol 58(12):1197–1207, 2011.

Transcatheter, percutaneously inserted aortc valves come from bovine pericardium (Figure 25-28). These may be inserted in a hybrid OR with fluoroscopy.

Aortic valve allografts (homografts) pose little or no risk of thromboembolism, offer optimal hemodynamic function, require no anticoagulation drugs, and raise virtually no risk of sudden catastrophic failure. Moreover, they demonstrate a lower incidence of infective endocarditis than that found in mechanical or biologic valves, and their long-term durability is comparable with that of bioprostheses. Allograft root replacement is also a valuable technique in the context of prosthetic valve endocarditis. The entire ascending aorta and valve (Figure 25-29) or the valve alone (Figure 25-30) may be inserted. Allografts are cryopreserved and must be thawed in saline according to the vendor's protocol before implantation. Because stentless aortic valves (see Figure 25-25, B) are more easily available than allografts, they are increasingly preferred for aortic root replacement.

Conduits consisting of mechanical or biologic aortic valves attached to a tube graft (Figure 25-31) are used in procedures such as repair of aortic dissections requiring replacement of the aortic valve and ascending aorta. If vein grafts must be inserted into the conduit or if a direct coronary ostial anastomosis is required, the surgeon uses an electrocoagulator to make the opening into the graft and at the same time heat-seals the cut edges of the prosthesis. Conduits with biologic valves interposed between tube graft materials may be used when patients are at increased risk for bleeding complications associated with the need for chronic anticoagulation therapy. Allograft conduits may be used for these procedures as well.

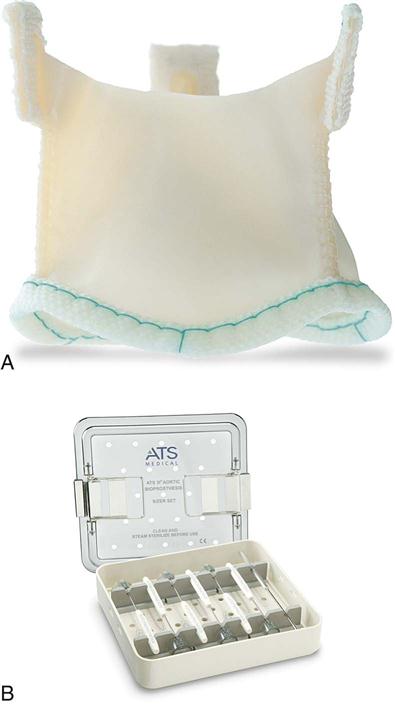

Although allografts and stentless bioprostheses may minimize prosthesis-patient mismatch and avoid the complications associated with prosthetic mechanical valve replacement, valve repair rather than replacement is preferred, particularly for mitral and tricuspid valve lesions. Numerous mitral valve rings and bands are available for both surgical and interventional percutaneous reparative procedures. Consult with the surgeon about the intended prosthesis as well as alternative devices should another prosthesis be required (Otto and Bonow, 2012). When repairing the native valve with an annuloplasty ring, obturators specific to various kinds of annuloplasty rings are used to size the annulus (Figure 25-32, A, B, C). Ensure that the sizers appropriate for the desired prosthesis are available.

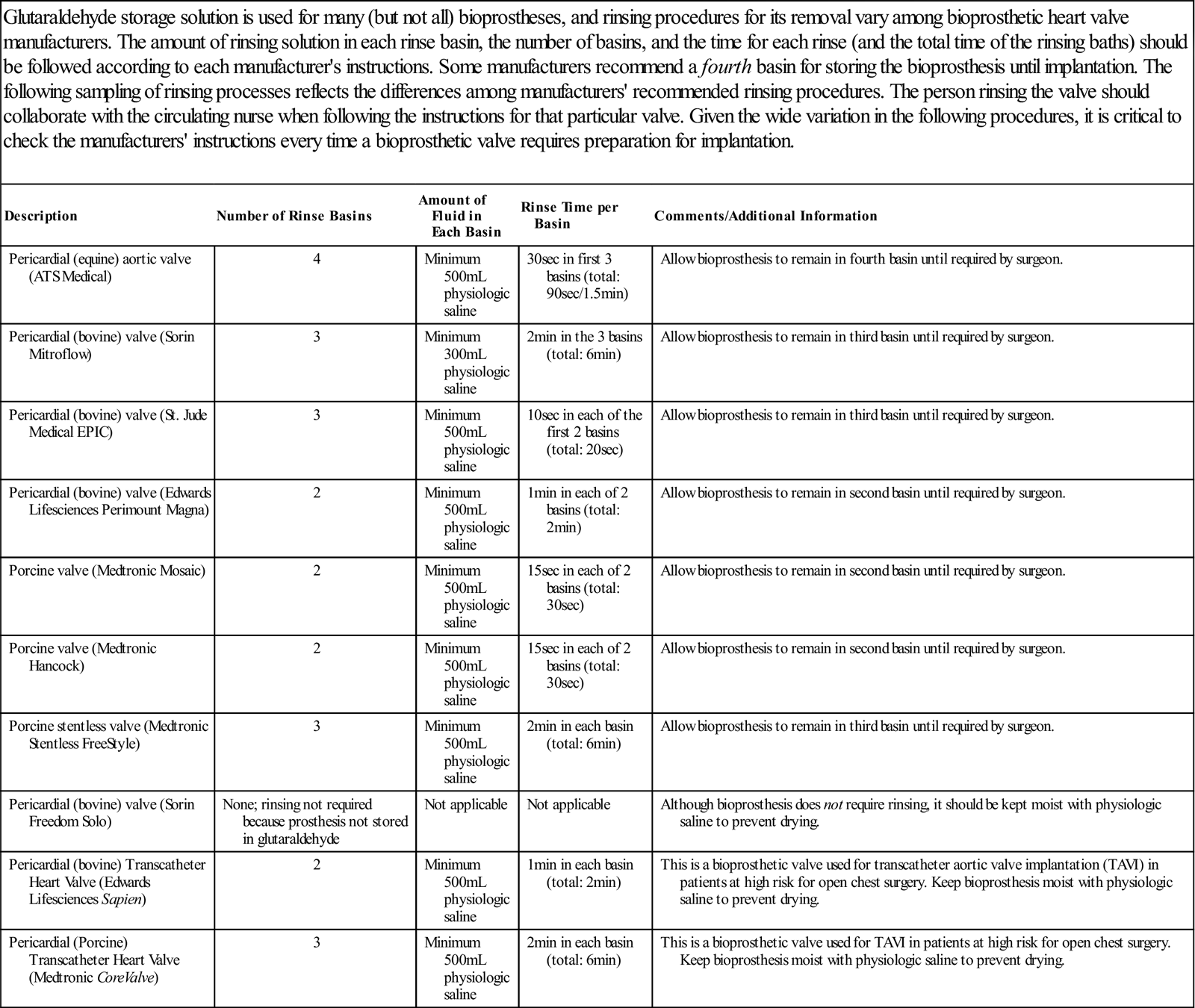

Additional safety considerations include storing prosthetic materials in a clean, protected environment and using them according to manufacturers' instructions. Before implantation, biologic valves (including the biologic valves within transcatheter aortic valve implantation [TAVI] systems) must be rinsed in three saline baths to remove the glutaraldehyde (or other) storage solution. The prescribed number of baths, the amount of physiologic fluid in each rinsing bath, and the recommended rinsing time for each bath vary among bioprosthetic manufacturers (Table 25-5). Adhere to the specific manufacturer's instructions for each prosthesis. Some bioprostheses do not require rinsing because their storage is in a physiologically neutral solution (i.e., not glutaraldehyde). However, before and during insertion, all bioprostheses should be kept moist with saline. Mechanical valves should be protected from scratching and other injury as well.

TABLE 25-5

Valve-Rinsing Procedures for Biologic Heart Valves

| Glutaraldehyde storage solution is used for many (but not all) bioprostheses, and rinsing procedures for its removal vary among bioprosthetic heart valve manufacturers. The amount of rinsing solution in each rinse basin, the number of basins, and the time for each rinse (and the total time of the rinsing baths) should be followed according to each manufacturer's instructions. Some manufacturers recommend a fourth basin for storing the bioprosthesis until implantation. The following sampling of rinsing processes reflects the differences among manufacturers' recommended rinsing procedures. The person rinsing the valve should collaborate with the circulating nurse when following the instructions for that particular valve. Given the wide variation in the following procedures, it is critical to check the manufacturers' instructions every time a bioprosthetic valve requires preparation for implantation. |

| Description | Number of Rinse Basins | Amount of Fluid in Each Basin | Rinse Time per Basin | Comments/Additional Information |

| Pericardial (equine) aortic valve (ATS Medical) | 4 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 30 sec in first 3 basins (total: 90 sec/1.5 min) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in fourth basin until required by surgeon. |

| Pericardial (bovine) valve (Sorin Mitroflow) | 3 | Minimum 300 mL physiologic saline | 2 min in the 3 basins (total: 6 min) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in third basin until required by surgeon. |

| Pericardial (bovine) valve (St. Jude Medical EPIC) | 3 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 10 sec in each of the first 2 basins (total: 20 sec) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in third basin until required by surgeon. |

| Pericardial (bovine) valve (Edwards Lifesciences Perimount Magna) | 2 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 1 min in each of 2 basins (total: 2 min) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in second basin until required by surgeon. |

| Porcine valve (Medtronic Mosaic) | 2 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 15 sec in each of 2 basins (total: 30 sec) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in second basin until required by surgeon. |

| Porcine valve (Medtronic Hancock) | 2 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 15 sec in each of 2 basins (total: 30 sec) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in second basin until required by surgeon. |

| Porcine stentless valve (Medtronic Stentless FreeStyle) | 3 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 2 min in each basin (total: 6 min) | Allow bioprosthesis to remain in third basin until required by surgeon. |

| Pericardial (bovine) valve (Sorin Freedom Solo) | None; rinsing not required because prosthesis not stored in glutaraldehyde | Not applicable | Not applicable | Although bioprosthesis does not require rinsing, it should be kept moist with physiologic saline to prevent drying. |

| Pericardial (bovine) Transcatheter Heart Valve (Edwards Lifesciences Sapien) | 2 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 1 min in each basin (total: 2 min) | This is a bioprosthetic valve used for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in patients at high risk for open chest surgery. Keep bioprosthesis moist with physiologic saline to prevent drying. |

| Pericardial (Porcine) Transcatheter Heart Valve (Medtronic CoreValve) | 3 | Minimum 500 mL physiologic saline | 2 min in each basin (total: 6 min) | This is a bioprosthetic valve used for TAVI in patients at high risk for open chest surgery. Keep bioprosthesis moist with physiologic saline to prevent drying. |

Preinduction Care.

After patient transfer to the OR suite, a focused preoperative assessment commences, and the perioperative nurse reviews the chart for a duly signed and witnessed informed consent form, advance directives, laboratory results, diagnostic data, and other pertinent information. The nurse also confirms the identity of the patient and the intended operation, including identification and confirmation of site and side, and required position, all as applicable. Verification of which leg (i.e., right or left) will serve for vein harvest in bypass patients may not be necessary if this decision depends on the surgeon's preference, rather than on a specific clinical indication. Some institutions, however, may require site marking of bypass harvesting sites, and the nurse should comply with institutional policy.

Preoperatively, cardiac surgical patients may exhibit more stress and anxiety than other surgical patients. Perioperative nurses should anticipate and prepare for this because stress and anxiety increase myocardial oxygen consumption. Efforts to reduce the family's stress and anxiety level are also important and may result in less communication of stress and anxiety to the patient. Often patients and family members ask questions about the surgery and the immediate postoperative appearance of the patient. It is helpful to prepare the family for some of the physical changes (e.g., edema, multiple tubes and lines) they can expect to see in their loved one postoperatively, and to encourage talking and touching the patient—even if the patient seems unable to respond (Patient-Centered Care).

In addition to communication with the patient, members of the team prepare the patient by ensuring vascular access for pressure monitoring and medication infusion. They insert a peripheral arterial pressure line and venous infusion lines. They may use a local anesthetic at insertion sites and may inject an IV sedative. Occasionally a patient's response to sedation results in impaired respiration, as evidenced by shallow respirations, decreased oxygen saturation, and a reduced respiratory rate (e.g., eight breaths per minute or less) (Nussmeier et al, 2009; Reich et al, 2011). The nurse noticing these respiratory changes can call a rapid response team (RRT) to assess the patient and initiate treatment before the patient develops more serious reactions, such as cardiopulmonary arrest. In this situation the RRT may consist of the anesthesia providers and staff in the immediate preoperative area rather than a specific hospital-wide RRT. For patients awaiting transfer from the preoperative area to the OR for cardiac surgery, the concept of a clinician acting promptly on changes in a patient's status and initiating a “rapid response” is an important aspect of enhancing a culture of patient safety.

Admission to the OR.

Depending on the patient's response to sedative medications received preoperatively, the patient may require assistance onto the OR bed. Warm blankets should be provided for comfort and to reduce shivering; the nurse should ensure that the blanket temperature does not produce thermal injury.

After application of the ECG leads and the pulse oximeter finger cot, padding of the hands, elbows, and feet follows. The perioperative nurse confirms that the peripheral arterial pressure line functions properly, may reposition the arm as necessary in collaboration with the anesthesia provider, and confirms that pulse oximetry functions properly. Additional monitoring devices appear in Table 25-6. A time-out commences to comply with TJC's Universal Protocol (see Chapter 2).