Integrative Health Practices

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Rachael Larner

Energy Therapies History and Background

An accurate presentation of the history of medicine in the United States needs to include influences from the botanic cultural traditions of Asia, India, Europe, and the First Nations. Our current medical system, referred to as biomedicine, began to dominate sometime in the mid-1800s with the discovery that microorganisms were responsible for disease and pathologic damage and that antitoxins and vaccines could improve the body's ability to oppose the effects of pathogens. Armed with this knowledge, scientists and clinicians were able to refine surgical procedures and treat previously serious and fatal infections.

As biomedicine dominated the healthcare system, it became the mainstream or “conventional” approach, establishing the standards for diagnosis and treatment of illness. By the 1990s, however, consumer faith and trust in this system began to falter, and many Americans sought complementary or alternative treatments for their healthcare. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), known currently as “integrative health practices,” has grown to constitute a significant percentage of American healthcare dollars and visits. This growth is sustained by patients who desire to be more empowered healthcare consumers and the availability of media information about the many alternatives to mainstream, conventional Western biomedical approaches to healthcare.

Myths and misconceptions initially prevented investigation and development of promising therapies outside the biomedical regimen. In response to growing consumer pressure, anecdotal evidence, and a small body of published scientific results, the U.S. Congress established the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) within the office of the director, National Institutes of Health (NIH), in 1992. This office was given responsibility for: (1) facilitating fair, scientific evaluation of alternative therapies that showed promise in health promotion, and (2) reducing barriers to the acceptance and utilization of those alternative therapies that showed promise.

In 1998 the OAM became the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, 2012a). This expansion into a center allowed more substantial funding for and initiation of research projects, providing more sound information about integrative health practices. The annual budget for NCCAM has grown significantly, as has the sophistication of research designs of studies being funded by the center. The NCCAM adheres to guidelines set forth in public policy.

Many integrative health practices and therapies stem from a philosophy of wholeness, with intent to treat the entire person (body-mind-spirit) (Evidence for Practice). This is in contrast to the current gold standard of randomized, controlled clinical trials, which may not be the best, or indeed appropriate, way to measure the effectiveness of many integrative health practices and therapies. Conventional scientists and physicians and the proponents of integrative health practices and CAM often debate the appropriate forms of research to determine efficacy and safety of alternative therapies. A reason for this disparity stems from divergent theoretic models. The comprehensive approach takes into account multidimensional factors that may not easily or appropriately be studied independently. The comprehensive approach is more congruent with the philosophic underpinnings of most integrative health practices and CAM. The biomedical approach, on the other hand, is concerned with a disease orientation, suggesting that a specific agent or variable is responsible for a specific disorder or illness.

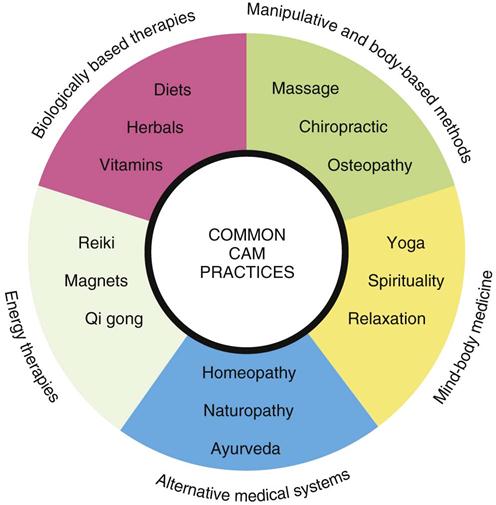

The NCCAM has categorized the many integrative health practice modalities into five major domains: alternative medical systems, mind-body medicine, biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based methods, and energy therapies (Figure 30-1). Numerous treatments and systems are within each category. The remainder of this chapter discusses the major domains and provides examples of each.

Major Categories of Integrative Health Practices and Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Alternative Medical Systems

An estimated 10% to 30% of human healthcare is delivered by practitioners such as surgeons and nurses who have been trained in the mainstream, conventional Western biomedical model. The remaining 70% to 90% involves care given in a healthcare system that is based on alternative traditions—self-care based in folk practice or practices that range somewhere between alternative and traditional healthcare. Many of these integrative health therapies are culturally, ethnically, spiritually, or religiously derived. Among the diverse values, beliefs, and practices found in the many cultural groups in the United States are those relating to health, illness, professional healthcare, and folk healthcare (Box 30-1). They include well-known and respected Asian systems of medicine. Many Asian medicine techniques or systems are widely known in the United States. The most well-known and popular of these include herbal medicines, massage, energy therapy, acupressure, acupuncture, and qi gong (Figure 30-2). This integrative, alternative medicine system has a wide range of applications from health promotion to the treatment of illness. A significant aspect of Asian medicine is an emphasis on diagnosing and treating disturbances of qi (pronounced “chee”), or vital energy, and restoring its proper balance (Micozzi, 2010).

Ayurveda is a traditional system from India that strives to restore the innate harmony of the individual while placing equal emphasis on body, mind, and spirit. Ayurvedic practitioners use many products and techniques to cleanse the body and restore balance. Key foundations are universal connectedness (e.g., that all living and nonliving things are joined together, health will be good if one's mind and body are in harmony, disease arises when a person is out of harmony with the universe), the body's constitution or prakriti (e.g., the person's unique physical and psychologic characteristics and how the person functions to maintain health), and life forces, or doshas. Each person has a combination of three doshas; each dosha has a particular relationship with a bodily function and can be upset for a variety of reasons. Treatment is tailored to each person's constitution and predominant dosha. Practitioners expect patients to be active participants because many ayurvedic treatments require changes in diet, lifestyle, and habits (NCCAM, 2012b).

Native American, Middle Eastern, Tibetan, Central and South American, and African cultures have developed other traditional medical systems (Micozzi, 2010). Additional examples of complete integrative health practice and alternative medicine systems are naturopathic and homeopathic medicine systems. Homeopathic medicine is based on the principle that “like cures like” (i.e., a substance that in large doses produces the symptoms of a disease will, in a very diluted dose, cure the patient). Small doses of plant extracts and minerals specially prepared are given to stimulate the body's defense mechanisms and encourage healing processes. Careful evaluation of symptoms enables the practitioner to determine a patient's specific sensitivity and to select the appropriate remedy.

Naturopathic medicine is one of the most recent alternative approaches to have developed as a health system across North America. In practice, modern naturopathic is eclectic, drawing on different systems and models (e.g., Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and manual therapies) to fit the patient profile and clinical problem with the appropriate techniques (Micozzi, 2010). Naturopathic medicine emphasizes health restoration as well as disease treatment based on the belief that disease is a manifestation of alterations in the body's natural healing processes. Naturopathic physicians use multiple modalities, including clinical nutrition and diet; acupuncture; herbal medicine; homeopathy; spinal and soft tissue manipulation; physical therapies involving ultrasound, light, and electric currents; therapeutic counseling; and pharmacology (Pizzorno and Snider, 2010).

Mind-Body Interventions

A growing scientific movement has explored the mind's ability to affect the body. The clinical application of this relationship is categorized as mind-body medicine. Some mind-body interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy), formerly categorized as CAM therapies, have been assimilated into conventional mainstream medicine. Progressive relaxation techniques, biofeedback, meditation, and cognitive-behavioral approaches have a well-documented theoretic basis with supporting scientific evidence. Other mind-body interventions still considered “alternative” by some include hypnosis, music, dance, art therapy, prayer, and mental healing.

Biologically Based Therapies

The integrative health practices category of biologically based therapies includes biologically based and natural-based practices, products, and interventions, some of which overlap with mainstream medicine's use of dietary supplements. Herbal, orthomolecular, individual biologic therapies and special dietary treatments are encompassed in biologically based therapies.

Herbs are plants or parts of plants that contain and produce chemical substances that act on the body. Some diet therapies are believed to promote health and prevent or control health. Proponents of diet therapies include religious factions such as Seventh-Day Adventist, or Jewish Kosher. Veganism, vegetarianism, raw food diets, and diets promoted by Drs. Atkins, Pritikin, and Weil are other examples of therapeutic nutrition. Orthomolecular therapies use differing concentrations of chemicals or megadoses of vitamins aimed at treating disease. Many biologic therapies are available but not currently accepted by mainstream medicine, such as the use of cartilage products from cattle, sheep, or sharks for treatment of cancer and arthritis or the use of bee pollen to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Manipulative and Body-Based Methods

Methods that are based on the movement or manipulation of the body include chiropractic, osteopathy, and massage. Touch and manipulations with the hands have been used in healing and medical practice since the beginning of the history of medicine. At one time, the physician's hands were considered the most important diagnostic and therapeutic tool. This remains true today, despite sophisticated diagnostic equipment and modalities (Box 30-2). Manual healing methods are based on the principle that dysfunction of a part of the body often affects secondarily the function of other discrete, possibly indirectly connected body parts. Theories have developed for correction of these secondary dysfunctions by realigning body parts or manipulating soft tissues. Chiropractic science is concerned primarily with the relationship between structure (spine primarily) and function (nervous system primarily) of the human body to preserve and restore health. Osteopathic medicine incorporates an extensive body of work that supports the use of osteopathic techniques for both musculoskeletal and nonmusculoskeletal problems. Massage therapy is one of the oldest methods known in the practice of healthcare. One experimental pilot showed that using massage with music therapy during the perioperative period reduced postoperative prolactin levels and anxiety (Selimen and Andsoy, 2011). Many different massage techniques are aimed at helping the body heal itself through the use of manipulation of the soft body tissues.

Energy Therapies

Energy therapies have been categorized into two groups: biofield therapies (those that focus on fields believed to originate within the body) and electromagnetic fields (those that originate from other sources). The existence of energy fields that originate within and around the body has not yet been definitively proven. However, many studies have examined the experiences of recipient or practitioner and the outcomes of this type of energy therapy. Examples of therapies with a biofield basis include acupuncture, reiki, qi gong, therapeutic touch (TT), and healing touch. Therapies that involve electromagnetic fields use unconventional pulsed fields, magnetic fields, alternating current fields, or direct current fields. These therapies have been clinically applied with patients who have arthritis, cancer, and pain (Kolthan, 2009).

Integrative Health Practices Use and Surgery

Energy Therapies

Patients have choices in how to manage their healthcare. However, surgery is the most invasive of all options. As healthcare consumers become more knowledgeable about their health they often seek complementary modalities to augment traditional Western medical therapies. Using the term alternative is actually misleading, which is why the field formerly known as CAM is more appropriately termed integrative health practices. Many progressive medical facilities embrace a holistic patient focus, exploring and integrating nontraditional healing modalities to support an individualized surgical experience. Biofield therapies represent a nonpharmacologic anxiolytic for surgical patients that may be integrated with an allopathic treatment plan.

Many ancient cultures refer to a human biofield or “life force.” Sometimes referred to as “energy work,” biofield therapeutics are a range of interventions sharing common beliefs. First is the existence of a “universal force” or “healing energy” arising from God (as the person understands this being), the cosmos, the earth, or another supernatural source. Second, the human biofield, as part of the “universal field,” is dynamic, open, complex, and pandimensional. Human biofields are constantly changing and interacting with each other, the environment, and the universal force field. Third, the ability to use one's biofield for healing is considered to be universal, although few people are aware of it without specific training. Last, practitioners intend to positively affect the patient's biofield, either by direct contact or by using the hands in proximity, similar to the ancient practice of laying on of hands (Jackson and Keegan, 2008) (Table 30-1).

TABLE 30-1

Comparisons of Selected Biofield Therapies

| Therapy | Practice Initiated | Developers | Hand Placement | Theoretic Basis and Intent |

| Healing Touch | 1981 | American Holistic Nurses Association | Both on and off the body | Uses elements of healing science and therapeutic touch in conjunction with crystal and dowsing to treat whole person and specific disorders |

| Qi gong | Traditional | Chinese | At meridian points or short distance from the body | Qi follows meridians and body patterns to heal biologic disorders. |

| Reiki | Traditional | Buddhist | A few standardized hand placements on the physical body | Spiritual energy from universe is channeled by “masters” to heal the spiritual body, which in turn heals the physical body |

| 1800s | Japan—Hawayo Takata | |||

| 1936 | United States—Mikao Usui | |||

| Therapeutic touch | 1972 | Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz | Primarily off the body 2-4 inches | Aligning Kunz's Human Energy Field model with Martha Rogers's Science of Unitary Human Beings, the centered practitioner assesses, directs, and modulates biofield energy to achieve relaxation response for healing of whole person |

| Reflexology | Traditional | Ancient method of treatment for ailments dating back to Egyptians and beyond | Application of pressure to sites on foot, hands, ears, and so on that correspond with organs and nerves to cause a reflex arc of stimulation to area in need | Promotes balance and wellness through nerve stimulation |

Modified from Engebretson J, Wardell D: Energy-based modalities, Nurs Clin North Am 42:243–259, 2007; National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Energy medicine: an overview, available at http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam. Accessed October 7, 2012.

Therapeutic Touch.

Therapeutic touch (TT) is the contemporary interpretation of several ancient healing modalities. Dolores Krieger and Dora Kunz developed TT in the early 1970s. The practice, like others that form part of the body of CAM, consists of learned skills for the conscious manipulation of human energies. In practice it is not necessary for the practitioner (healer) to actually touch the recipient (healee), because the energy field can be “felt” several inches away from the physical body. TT helps to aid in relaxation, reduces pain, promotes deeper and easier breathing, improves circulation of blood and movement of lymph fluids, reduces blood pressure, and strengthens the immune system.

To work within biofields, the practitioner uses a model or map to focus the healing energy. Chakras, or energy centers, described by the Upanishads in the Vedas, the oldest literature of the East Indian people, are often used as a reference point. Although the most detailed descriptions are in the Upanishads, the attributes are found in the teachings of other cultures as widely geographic as the Sufis of the Middle East to the First Nations, particularly from the North American Southwest (Figure 30-3).

TT practice lends itself well to the fast-paced surgical environment. The skills learned through study of TT provide a trained practitioner with the ability to center quickly and use intention to calm both himself or herself and others nearby in stressful situations. Research design, methods, techniques, and sample sizes are considerations for future studies into how biofield therapeutics may benefit surgical patients. Replicating past studies, as well as new research based on physiologic data and quantitative studies, is necessary (Research Highlight). It has become evident that the concepts involved in energy therapies need consistent definitions. If the concepts do not have preestablished definitions, they cannot be quantified or measured in meaningful ways. However, interest is high and research continues in an effort to better understand a phenomenon that seems to provide meaningful relief to the patient.

Perioperative Medical Hypnotherapy

Use of medical hypnotherapy in hospitals and clinics for perioperative care is not uncommon. Patients are seeking an active role in their treatment and are better informed regarding surgical options. Participating in perioperative medical hypnotherapy allows patients to take shared responsibility for their healing process, giving them a measure of control, because all hypnosis is self-hypnosis. Meaningful and active participation empowers a patient to enter into anesthesia and surgery with confidence.

Surgery is a life-changing event, and each perioperative medical hypnotherapy patient is unique. The initial assessment serves to determine goals and explore questions relative to emotional as well as physical concerns. The hypnotherapist, working within the patient's belief system, helps acknowledge areas of the patient's concern as a multidisciplinary partnership of healing is forged in a patient-centered manner.

As the hypnotherapist guides the patient into relaxation and induces hypnosis, both therapist and patient journey into the body, together addressing predetermined issues. Fear of the unknown, preprocedure anxiety, changes in body image, anticipated pain or nausea, loss of organs, and transplantation of new organs are some examples of issues that may be addressed in the perioperative setting (Gurgevich, 2012).

Hypnosis compassionately allows a patient to explore emotions without judgment or expectation of those feelings. The practice of emotional awareness, of being present with feelings, and of holding those feelings sacred can bring a sense of peace and healing insights during a time of profound stress, such as that experienced by many surgical patients. Predetermined suggestions or affirmations may increase confidence in the healthcare team, increase compliance with the treatment plan, decrease blood loss, maintain intraoperative homeostasis, reduce the need for sedation or pain medication, decrease postoperative nausea or vomiting, and increase patient satisfaction. In a study done on patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery, it was found that preoperative relaxation techniques helped with postoperative pain and increased healing time (Topcu and Findik, 2012).

Postoperative hypnotherapy sessions reinforce continued participation of patients in their healing process. This may take the form of establishing metabolic gauges in the “control room” or show a symbolic shield of protection, holding or sending color, light, or a certain feeling of safety to a specific part of the body. It may be expressing gratitude to and confidence in the medical and nursing community. Follow-up sessions allow both patient and hypnotherapist to evaluate attainment of preoperative goals, consider postoperative outcomes, and explore issues relevant to the ongoing healing process.

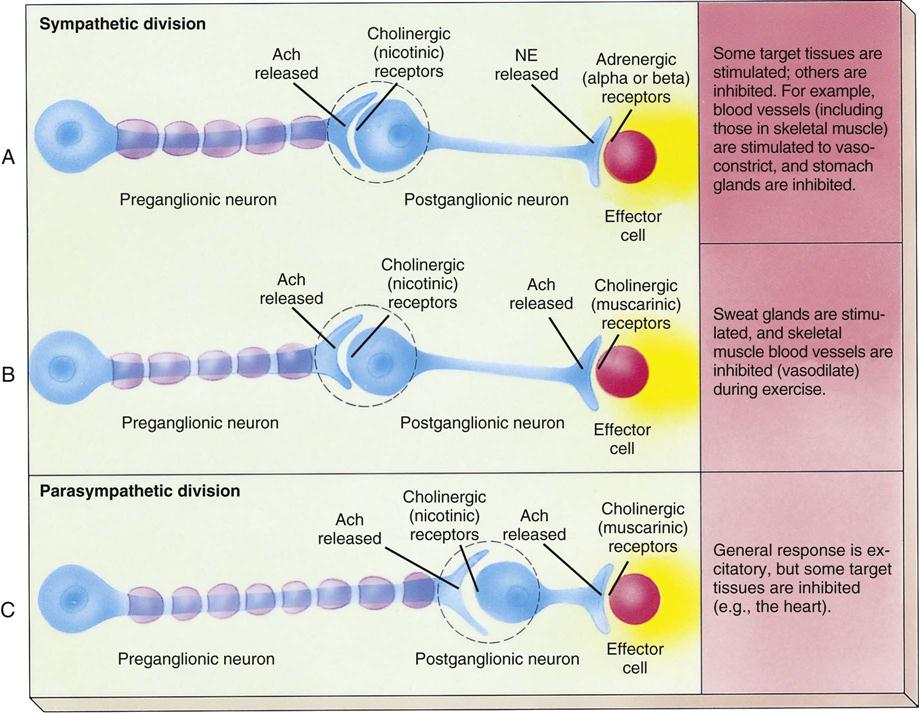

Guided Imagery

Another therapy closely related to hypnosis is guided imagery. Imagery, or thinking in pictures, is the natural language of the unconscious mind and is used by the autonomic nervous system as a primary mode of communication. The autonomic nervous system controls unconscious body functions such as heart rate, immune function, digestion, blood flow, smooth muscle tension, and pain perception (Figure 30-4). Guided imagery for surgical patients may be in the form of pre-scripted tapes that lead the patient through relaxation exercises and provide healing suggestions. In other instances the perioperative nurse may assist the patient with guided imagery through the use of a calming, monotone voice; a smooth speaking delivery; and the use of relaxing images, such as a place in nature. The perioperative nurse coaches the patient to see, feel, smell, sense, and hear the imagined scene. Imagery may help patients build a “tool” to help in the postoperative period and lead to quicker recovery. According to Selimen and Andsoy (2011), benefits of guided imagery for surgery patients may include:

Aromatherapy in Perioperative Services

Aromatherapy involves the therapeutic use of fragrance (e.g., aromatic plant extracts and essential oils) applied to the patient's body through inhalation or topical methods, or rarely ingestion. Long before Western medicine, use of aromatherapy and herbs was part of physicians' practice and prescriptive use and was taught in all of the original Nightingale schools (Radzyminski, 2007). Clinical aromatherapy is gaining acceptance with consent and participation of patients. It is practiced by certified clinical aromatherapy practitioners (CCAPs), knowledgeable about the specific properties of essential oils and how they interact with patients and the therapeutic environment. CCAPs use clinical-grade essential oils in a controlled way for specific, measurable outcomes. These may affect the patient on a psychologic, physiologic, or cellular level. The choice of essential oil is based on the chemistry of that essential oil and its proven effects (Table 30-2).

TABLE 30-2

Essential Oils and Their Properties

| Property | Essential Oils |

| Antiemetic | Chamomile, lavender, lemon, peppermint, ginger |

| Antiseptic | Bergamot, clove, eucalyptus, lavender, juniper, thyme, tea tree |

| Anxiolytic | Benzoin, bergamot, chamomile, jasmine, lavender, neroli, rose, sandalwood, verbena, ylang-ylang |

| Analgesic | Lavender, West Indian lemongrass, peppermint, Turkish oregano, Brazilian mint |

| Sedating | Bergamot, chamomile, jasmine, lavender, neroli, rose, ylang-ylang |

| Stimulating | Basil, black pepper, eucalyptus, peppermint, rosemary |

| Antiinflammatory | German chamomile, rosemary, black pepper, helichrysum |

Modified from Mantle F, Tiran D: A-Z of complementary and alternative medicine, London, 2009, Churchill Livingstone; Steflitsch W, Steflitsch M: Clinical aromatherapy, J Men Health 5(1):74–85, 2008.

As pharmacology combines medications to potentiate effect, aromatherapy may act synergistically with traditional treatment, or it may be offered in concert with other complementary modalities to relieve discomfort, thereby reducing dosages of analgesics or sedatives. Using specific scents postoperatively, such as peppermint, has decreased nausea and vomiting (Lane et al, 2012).

The nursing process of aromatherapy begins with obtaining consent for use of aromatics and collecting pertinent information. Assessment of the patient, the physical environment, and the team of caregivers defines the healing environment. Along with review of the medical and nursing histories, allergies, vital signs, and laboratory values, subjective data are relevant, such as how to offer treatment. The plan of therapy may include direct inhalation (on a cotton ball or through a diffuser), compresses, topical application, or massage. As with all nursing interventions, postprocedure follow-up with the patient is imperative to assess efficacy of this intervention (Research Highlight).

Additional well-designed research is required to provide data substantiating the value of clinical aromatherapy as another component of holistic perioperative nursing practice.

Music and Surgery

The therapeutic and healing properties of music have been recognized throughout history. Music has been shown to reduce stress and can block out unwanted noises around the patient during all perioperative phases, which makes the environment more enjoyable for the patient. Music can be used to stimulate the left and right side of the brain simultaneously and therefore can stimulate and organize muscle response, which can be a large benefit to patients with neuromuscular disorders. Patients who listen to music 30 minutes before a surgery or within 1 hour following surgery have lower pain and anxiety levels, which provides a more therapeutic environment for the patient (Selimen and Andsoy, 2011).

Music has been shown to increase metabolism; increase or decrease muscular energy, breathing rate, blood volume, pulse rate, and blood pressure; and lower sensory stimuli thresholds. Music can touch patients deeply and thus transform their anxiety and discomfort into relaxation and healing.

Anxiety and pain are common perioperative nursing diagnoses identified in the sample plans of care in Unit 2 in this book. Because anxiety and pain lead to increased stress and stress may cause detrimental physiologic reactions, many nursing interventions are undertaken to reduce patients' anxiety. Music is a nursing intervention that is easy to administer, relatively inexpensive, and noninvasive.

Music is therapeutic if used in a manner that enables its elements and their influences to aid in integration of the body, mind, and spirit of the patient during the treatment of an illness or disability. When selecting music to invoke physiologic and psychologic changes, it is important to note the attributes of music. Factors that need to be considered are the various elements of music (e.g., tempo, mode, pitch, rhythm, harmony, melody); listener characteristics (e.g., age, language, culture, education, musical preferences); and the mode of delivery (e.g., headphones, speakers). Slow, quiet music without lyrics tends to lower the physiologic responses associated with stress and anxiety. Fast tempos tend to increase tension, and slow tempos can cause suspense. A tempo of 60 to 72 beats per minute appears to promote relaxation and decrease anxiety, as theorized by matching the normal heart rate of humans. Research also demonstrates the importance of patient-selected music that is familiar, desirable, and meaningful, which often leads to positive responses from patients. The use of headphones blocks unpleasant environmental sounds, a common occurrence in busy preoperative holding areas and operating room (OR) suites. Compact disks or MP3 players provide consistent, uninterrupted music, which is critical to the success of the ongoing therapeutic reactions that music affords. Best of all, music therapy can be used preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively.

Anticipation of surgery commonly produces anxiety. The preoperative waiting period may be more stressful and anxiety-provoking for some patients than the anticipated surgical intervention. High levels of anxiety cause negative physiologic manifestations, such as elevated blood pressure, that can lead to postoperative complications, such as increased cardiac workload. High levels of preoperative anxiety may result in postoperative complications such as depression, fear, and anger, and the use of music during the preoperative phase can decrease anxiety and significantly lessen complications in the postoperative phase of recovery. Emotions are altered, apprehension and tension are reduced, and sympathetic stimulation and adrenocortical activation are more controlled. Therefore, changes in vital signs, such as elevated blood pressure and increased heart rate, are minimal. Studies have shown that patients listening to music have a decrease in anxiety and pain during the perioperative stay (Wakim et al, 2010).

Patients undergoing surgery in which local or regional anesthetics are administered have an acute awareness of the environment found within the OR. The OR may appear threatening, with unfamiliar machines, equipment, noises, and smells. Physical positioning and exposure of body parts intensify anxiety. Unfamiliar sounds, bright lights, and technical language add to the stressors of the surgical experience. During surgery, patient-selected music reduces anxiety by providing the patient some autonomy through self-selected musical choices, while distracting the patient from what is happening within the environment. The music not only blocks the various sounds in the room but also provides an escape through imaginative thought. Researchers support the idea that musical vibrations have an effect on the subconscious mind. Older patients have reported comfort and strength by listening to hymns and other music of spiritual or psychologic support. Daydreaming, imagery, escape, and fantasizing are common to listeners. This creates a release of tension and is a way of focusing attention away from threats. Intraoperative music may decrease the patient's anxiety and consequently minimize the need for patient-controlled conscious sedation and analgesia. Music can have a positive effect during general anesthesia when delivered through headphones or earpieces, as long as care is exerted to prevent pressure points and volume increases.

Pain is a common problem in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Pain results in negative respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, neuroendocrine, and autonomic nervous system consequences for patients. The traditional means to providing pain relief in the PACU has been through medication administration. Because the effects of medication differs from person to person, using nonpharmacologic interventions along with traditional medications may serve to lower a patient's anxiety and pain throughout all perioperative phases (Schultz et al, 2012).

Noise levels contribute to the patients' discomfort (Nightingale, 1859). The level of noise typically encountered during the surgical experience is potentially harmful to patients because of the undesirable effects of a release of stress hormones on the cardiovascular system, including increased vasoconstriction, heart rate, and blood pressure. Noise also increases psychologic stress and discomfort, and patients' ability to cope is reduced. Soothing music delivered through a headset can block out external noises and can serve as a distraction from the noise of the PACU.

When using music as a nursing intervention to promote physiologic and psychologic well-being, the nurse prepares both the patient and the environment. The nurse should inform the patient of the purpose of the music experience and interview the patient about musical preferences, allowing the patient to listen to portions of selected music to ensure the music will afford the therapeutic purpose. The use of music therapy is documented in the medical record. A library of different types of music selections should be available. When compiling these collections, it is important that attention is given to the tempo, rhythm, melody, and harmony of the music (as noted earlier). In addition to implementing the music intervention, nurses monitor patients' responses to ensure that intended outcomes are achieved, making adjustments as necessary.

Psychoneuroimmunology

Psychoneuroimmunology studies the relationship between the brain and immune function. Thus perioperative nursing interventions that seek to reduce stress influences have the potential to improve immune system function. This involves how perioperative nurses communicate with patients as well as their behaviors, the attitudes they convey, the language they use, and their being “present” and totally engaged with their patients (Table 30-3) (Patient-Centered Care).

TABLE 30-3

Languaging for Nurses: Enhancing Patient-Centered Communication

| Positive, Therapeutic Language | Negative, Toxic Language |

| We're giving you the medication that will let you gently go to sleep. | We're going to put you to sleep now. |

| We are well trained in how to take care of you. | Don't be afraid. |

| I'll be with you the entire time to make sure you stay asleep and comfortable. | Don't worry; you won't wake up during surgery. |

| Focus your energy on healing. | Don't give up. |

| You might feel pressure; some people don't feel anything. | This isn't going to hurt. Just a little bee sting. |

Modified from Eslinger MR: The power of suggestion, languaging for nurses, AHNA beginnings, Am Holist Nurs Assoc 29(2):22–23, 2009.

Early animal conditioning studies showed links on a molecular level (immune regulators: neurotransmitters and hormones) that act to stimulate nerves or trigger physiologic changes. Further, the perception of stress is known to lead to a reduced ability to fight infection. Because measurement of immune function is a complicated process, much remains to be learned about the precise mechanism of how psychosocial or emotional factors affect susceptibility to disease.

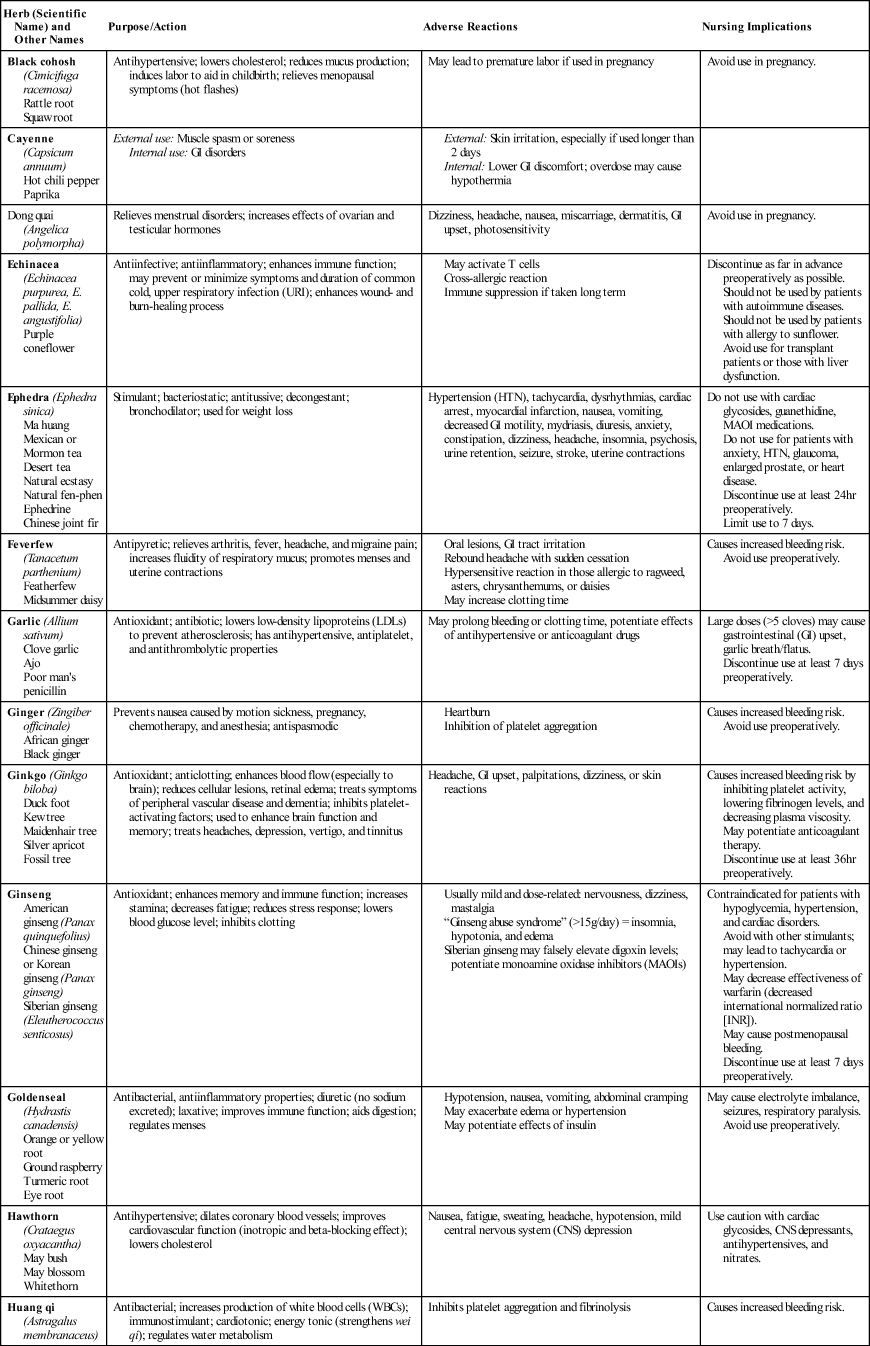

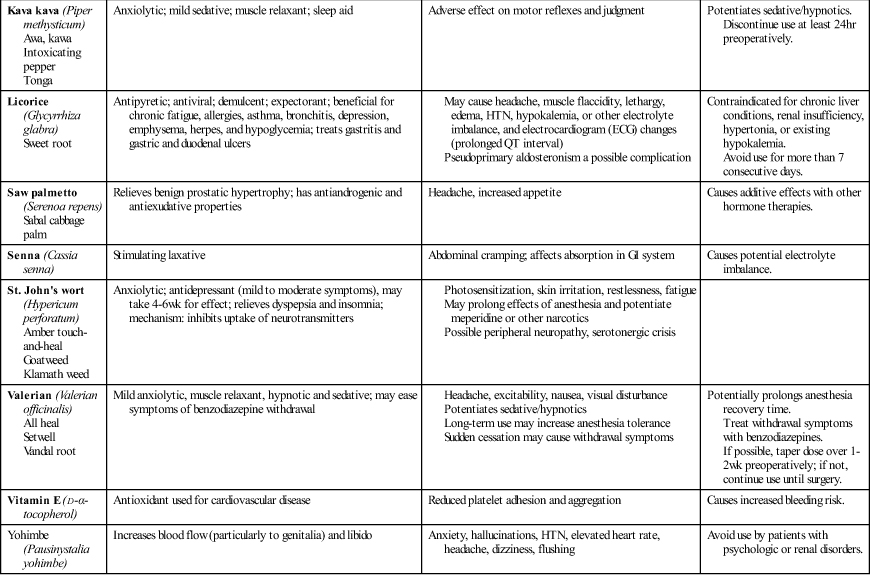

Herbs and Surgery

The use of herbal and botanic products is common. Patient surveys have shown 12% of Americans use herbal medications (Wong and Townley, 2011). However, many patients do not communicate this information to their conventional medical physicians or nurse caregivers, because they are unsure of the reaction of conventional caregivers to their use of alternative substances.

Botanicals are marketed as food supplements in the United States. Manufacturers are not allowed to make claims about health benefits for these products because they are not FDA-approved. Since 1994, when the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) was passed, the definition of dietary supplements has broadened. A product that contains a vitamin, mineral, herb, amino acid, or other botanic or dietary substance used to supplement the diet is considered a dietary supplement; this includes concentrates, metabolites, constituents, extracts, and combinations of listed ingredients. These supplements are no longer subject to premarket safety evaluations by the FDA. Once a supplement is marketed, under the DSHEA, the FDA can restrict its use only if it can be shown that the product is unsafe.

There are no regulations establishing criteria for purity, manufacturing procedures, or identification of ingredients for these supplements. Therefore, the potential exists for high variability in the potency of different batches of the same botanic product. In addition, impurities and unknown substances may also be present in these products. Because herbal products are so readily available and have such widespread media attention, many people think that they can safely self-medicate (Patient and Family Education). Another mistaken assumption is that dietary supplements are safer than prescribed or over-the-counter drugs.

Botanicals may initiate a pharmacologic response within the body and therefore should be considered as medications from a medical or nursing perspective. Many herbal products have actions that could be dangerous during surgery. Some herbal supplements may accentuate the toxicity of anesthetics or interfere with drug metabolism or clearance (Surgical Pharmacology). Herbal supplements may also have a role in the perioperative setting and are an important consideration for nurses.

Surgical Pharmacology

Herbs: Effects and Precautions/Recommendations

| The use of herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) has become increasingly popular as people become more educated consumers and take a more active interest in their health. Because herbal supplements and other nutriceuticals are available without prescription, patients may not reveal their use of these therapies unless specifically questioned. The perioperative nurse must always consider the possibility that the patient is taking supplements, and assess for their use. As with other medications the patient may be taking, the nurse is responsible to know the potential for interaction with medications used in the perioperative period. The information that follows offers a source for broadening the perioperative nurse's knowledge of commonly used herbal supplements. |

Modified from Skidmore-Roth L: Mosby's handbook of herbs & natural supplements, ed 4, St Louis, 2010, Mosby; Tsai HH et al: Evaluation of documented drug interactions and contraindications associated with herbs and dietary supplements—a systematic literature review, Int J Clin Pract 66(11):1056–1078, 2012.

Coagulation Interactions.

Anesthesia providers are concerned about the potential increased risk of instability intraoperatively resulting from inhibition of coagulation with the use of ginger, ginseng, feverfew, ginkgo, and garlic (Skidmore-Roth, 2010). One difficulty with analyzing case reports is the lack of laboratory analysis of the purported botanicals. In some reported cases in which prolonged or excessive bleeding occurred, the patient had been taking multiple herb supplements and drugs. Many plants contain anticoagulant components, including ginger, ginseng, feverfew, and others (Box 30-3); however, it is unknown if the danger posed is clinically significant.

Sedative Interactions.

Some botanicals have significant sedative actions. Anesthesia providers are concerned about the potential for valerian and St. John's wort to prolong or potentiate the sedative effect of anesthetic agents. Valerian has been associated with central nervous system (CNS) depression and muscle relaxant effects in animals; large doses of valerian may contribute to delirium and high-output cardiac failure on emergence from general anesthesia. Although St. John's wort has been found to inhibit the binding of naloxone, to date no cases have been reported of excessive sedation when combined with narcotics. In addition, there is concern about the monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) activity of St. John's wort, although no cases of MAOI effects in humans have been reported (Skidmore-Roth, 2010).

Cardiovascular Interactions.

Hypertension and cardiac dysrhythmias are potential adverse events that may result from the sympathetic stimulation that occurs during intubation and surgery. Ephedra has been associated with cardiovascular effects, including hypertension, palpitations, tachycardia, stroke, and seizures. The long-term use of licorice may cause hypertension, dysrhythmias, or hypokalemia, which can potentiate muscle relaxants and cause adverse cardiovascular effects (Skidmore-Roth, 2010).

Because the use of botanic supplements may increase the risk of adverse herb-drug interactions, patients should be counseled to discontinue herbs preoperatively. Generally anesthesiologists recommend that patients stop taking any herbal supplement at least 2 weeks preoperatively (Wong and Townley, 2011). Most patients, however, do not see an anesthesia provider until the day of surgery or a few days before surgery, so the implementation of this recommendation is challenging. Clinical research is insufficient to quantify the actual dangers of these herbal supplements. Nonetheless, because individuals vary in their absorption, distribution, and clearance of the drugs administered during anesthesia, adding unknown chemicals into an already complex and fast-acting mix of drugs is likely an unnecessary risk.

Integrative Health Practices and Perioperative Patient Care

A variety of factors influence the perioperative patient's experience. Well-informed healthcare consumers increasingly choose a blend of traditional and nontraditional healing modalities with sensitivity to cultural, spiritual, and health education needs. Public involvement and legislative policy decisions are just beginning to equalize emphasis between the traditional biomedical model of care and a holistic comprehensive focus. Integrating health and wholeness incorporates elements of self-responsibility for wellness and self-awareness to inner changes on the part of the patient.

A collaborative partnership of professionals involved in an individual's care optimizes resources that promote comprehensive, effective, less-invasive, and nonpharmacologic adjuncts to allopathic medical treatment (Patient Safety). Perioperative nurses using available resources on interactions among prescriptions, dietary supplements, and herbals ensure preoperative medication safety. Seeking out and participating in appropriate research methodologies are essential for grounding the diverse components of our practice in evidence-based knowledge.

Documenting integrative health practices may involve noting herbals or the dietary supplement regimen the patient followed preoperatively. The nurse should also note whether these were discontinued and, if so, when. Nurse energy work practitioners who comply with a patient's request for energy treatment may refer to the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA International) diagnosis Disturbed Energy Field when comfort measures such as TT, healing touch, or reiki are provided by the perioperative nurse.

Integrative health practices and therapies have a place in each perioperative nurse's practice (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations). Nursing history demonstrates a philosophic attitude of altruism and compassion, founded in creating an environment of healing. Awareness of how vital self-care practices are to sustaining a caregiver role may ultimately benefit our practice. Self-care learning and meditative experiences may come full circle by enhancing the caregiver's therapeutic use of self through presence, compassion, and holistic assessment skills.

Key Points

• The comprehensive approach takes into account multidimensional factors that may not easily or appropriately be studied independently. The comprehensive approach is more congruent with the philosophic underpinnings of most integrative health practices.

• The biomedical approach is concerned with a disease orientation, suggesting that a specific agent or variable is responsible for a specific disorder or illness.

• The NCCAM has categorized the many integrative (CAM) modalities into five major domains: alternative medical systems, mind-body interventions, biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based methods, and energy therapies.

• Naturopathic medicine emphasizes health restoration as well as disease treatment based on the belief that disease is a manifestation of alterations in the body's natural healing processes.

• Touch and manipulations with the hands have been used in healing and medical practice since the beginning of the history of medicine.

• To use the term alternative is actually misleading. Many progressive medical facilities embrace a holistic patient focus, exploring and integrating nontraditional healing modalities to support an individualized surgical experience.

• As pharmacology combines medications to potentiate effect, aromatherapy may act synergistically with traditional treatment; or it may be offered in concert with other complementary modalities to relieve discomfort, thereby reducing dosages of analgesics or sedatives.

• Because the use of botanic supplements may increase the risk of adverse herb-drug interactions, patients should be counseled to discontinue herbs preoperatively. Generally anesthesia providers recommend that patients stop taking any herbal supplement at least 2 weeks preoperatively.

• Well-informed healthcare consumers increasingly choose a blend of traditional and nontraditional healing modalities with sensitivity to cultural, spiritual, and health education needs.

• Documenting integrated care may involve noting herbals or the dietary supplement regimen the patient followed preoperatively. The nurse should also note whether these were discontinued and, if so, when.

Critical Thinking Question

While assessing your preoperative patient undergoing thyroid surgery, you notice she is visibly upset and worried about the operation. She is particularly upset about waking up during surgery, postoperative pain, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Otherwise she is oriented, alert, and educated on what her surgery entails. What holistic nursing interventions would you consider in your plan of care? How would you communicate with this patient to help to decrease her anxiety prior to surgery?

![]() The answers to the Critical Thinking Question can be found at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rothrock/Alexander.

The answers to the Critical Thinking Question can be found at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Rothrock/Alexander.