Critical care nursing

Nature and function of critical care nursing

Nurses are the round-the-clock constant for critically ill patients and their families, providing continuity and acting as the ‘glue’ that holds the service together. Nurses fine-tune, coordinate and communicate the many aspects of treatment and care needed by the patient, with:

• continuous, close monitoring of the patient and attached apparatus

• dynamic analysis and synthesis of complex data

• anticipation of complications

• complex decision making, execution and evaluation of interventions so as to minimise adverse effects

• enhancement of the speed and quality of recovery

• emotional support of the patient and family, including support through the end-of-life.1

Nursing in critical care is influenced by the essential nature of nursing as well as the specific requirements of the speciality. Key concepts for all nurses are said to include an appreciation of holism and the whole range of influences on all areas of life, and the pursuit of health rather than treatment of illness.2

There is inevitably an emphasis on technology in the intensive care unit (ICU): nurses must be technically competent. It is all too easy to neglect the human aspects of care. Expert nurses connect with patients both physically and psychologically,3 but patient-centred care and emotional support can be lost when the nursing resource is reduced.4 One ICU patient described his treatment as ‘rooted in the minute analysis of charts and the balancing of chemicals, not so much in the warmth of human contact’.5 Others reported feelings of helplessness, desertion and powerlessness.6 ICU patients are less heavily sedated and therefore more aware than previously, but can rarely control what happens to them during critical illness, especially in the acute phase. They usually wish to reassert their autonomy as they recover (e.g. during weaning from ventilation or when moving to a lower level of care). Nurses can enable patients to have a say in the management of these processes while still ensuring a safe progression. Essential personal care is invariably undertaken or supervised by nurses; and although important functions such as chest physiotherapy, mobilisation and administration of nutrition may be prescribed by other specialists, they will still be integrated and delivered by nurses.

A systematic approach to care

Nursing the critically ill patient is complex. The clinical review should be structured in order to clarify and prioritise patient needs so that all possible problems are addressed. In acute situations, assessment in turn of the fundamental A–B–C–D–E aspects of care is a useful method:

A airway: with establishment and maintenance of airway patency (using artificial devices when necessary, removal of pulmonary secretions, etc.)

B breathing: ensuring adequacy of oxygenation and ventilation, etc.

C circulation: assessing blood volume and pressures; perfusion of brain, heart, lungs, kidneys, gut and other organs; control of bleeding, haematology, etc.

D disability: checking level of consciousness/reduced consciousness, and the factors that affect it; systemic and localised neurology

E exposure: hands-on, head to toe, front and back examination, and review of everything else; with consideration of wounds and drains; electrolytes and biochemistry, renal function, etc.

Treatment strategies can be prioritised using this schema, which has the additional benefit that it will be familiar to colleagues trained in advanced life support and similar systems.

Further detail may be gained from review of:

F fluid and electrolyte balance, fluid input, urine output

G gastrointestinal function: nutritional needs; elimination

H history and holistic overview of the patient as a person and their socio-cultural context

I infection and infection control; microbiology

N nursing and interdisciplinary teamwork: ensuring resources are sufficient for the patient's severity of illness and the physical demands of care

P psychology: and the plan of care and prognosis in the short, medium and longer term.7

More sophisticated models can be used to frame a wider impression of the patient or to reflect a particular philosophy or approach to care.8 There is a great benefit in developing a shared vision within the department, and in articulating how agreed values will be demonstrated in practice.9 These might include emphasising the primary importance of patient safety and well-being, ensuring that the kindness an individual would want for their own loved ones is always offered, effective teamworking, and having systems in place to achieve continuous improvement.10 Whichever method is used, there must be explicit definitions of the patient's problems and a clear statement of measurable therapeutic goals.

Nursing and patient safety

Many patients suffer iatrogenic harm, but bedside nurses have the opportunity to prevent such incidents by intercepting and mitigating errors made by others.11 No particular system of critical care nursing has been shown to be definitively superior to others,12 but nursing surveillance is key to patient safety.13 Insufficient staffing has been linked to increased adverse events, morbidity and mortality.14 At the minimum, 5.6 nurses need to be employed for each patient requiring 1 : 1 care 24 hours a day.

Evolving roles of critical care nurses

Critical care nurses' range of practice has widened with progress in technology and changes in the working of other professionals, although the benefits of developing new skills must be balanced against ensuring the maintenance of fundamental care. There is great variation in the array of tasks undertaken by nurses in critical care in different institutions, with invasive procedures and drug prescriptions still usually performed by doctors. Since 2006 qualified nurse prescribers in the UK have been enabled – in theory at least – to prescribe licensed medicines for the whole range of medical conditions. As yet, nurse prescribing is not a widespread phenomenon in critical care but is likely to become a routine part of practice in the future.

Critical care nurses have a rapidly developing role in decision making regarding the adjustment, titration and troubleshooting of such key therapies as ventilation, fluid and inotrope administration, and renal replacement therapy. The use of less-invasive techniques (e.g. transoesophageal Doppler ultrasonography for cardiac output estimation) mean it is possible for nurses to institute sophisticated monitoring and administer appropriate treatments. There is evidence that nurses can achieve good outcomes in these areas, especially with the use of clinical guidelines and protocols (e.g. by reducing the time to wean respiratory support15). It is clear that further development of protocols, guidelines and care pathways can be used to enhance the nursing contribution to critical care.

New nursing roles in critical care

Maintaining adequate numbers of staff with the experience and skills to meet the increasing needs of critically ill patients is a challenge. Nurses constitute the largest part of the workforce and represent a significant cost. Changes in training arrangements and the demographics of nurses in general have meant that there are relatively fewer applicants for ICU posts. This has necessitated the development of various new ways of working to deliver both fundamental and more sophisticated aspects of care. New nursing roles include some that substitute for medical roles, as well as those that retain a nursing focus and aim to fill gaps in health care with nursing practice rather than medical care. The UK has designated a number of senior ‘nurse consultant’ posts in all areas of health, but with the largest proportion in critical care, particularly in outreach roles.16 These are advanced practitioners focusing primarily on clinical practice but also required to demonstrate professional leadership and consultancy, development of practical education and training, macro-level practice, and service development, research and evaluation.

Other staff – such as ‘nursing’ or ‘health care assistants’ – are increasingly and successfully employed to deliver what has previously been seen as core nursing care, in order to support trained nurses and free them to concentrate on more advanced practice.17 Reductions in health care funding and shortages of trained staff are likely to make such developments more common, but it is imperative that this is a managed process so as to ensure the best outcomes for patients, with proper arrangements for training, support and systems of work.

Critical care nursing beyond the icu: critical care outreach (see Ch. 2)

Around the world, general ward staff are required to manage an increasing throughput of patients who are, on average, older than before, with more chronic diseases, and more acute and critical illness. A national review of critically ill ward patients showed that the majority experienced substandard care before transfer to the ICU.18 Various factors are implicated, including knowledge deficits and failure to appreciate clinical urgency or seek advice, compounded by poor organisation. It is nurses who record or supervise the recording of vital signs, but there is often poor understanding of the importance of such indicators, ineffective communication with senior staff, and difficulties ensuring that appropriate treatments are prescribed and administered. Nurse-led critical care outreach teams support ward staff caring for at-risk and deteriorating patients, and facilitate transfer to ICU when appropriate.19 They can also support the care of patients on wards after discharge from ICU,20 and after discharge from the hospital too. Potential problems with these approaches include a loss of specialist critical care staff from the ICU, and being sure that outreach teams have the necessary skills to manage high-risk patients in less well-equipped areas, particularly when there are limitations placed on nurses prescribing and administering treatments.

Nursing in the interdisciplinary team

High-quality critical care requires genuine interdisciplinary teamwork, with:

• members who share knowledge, skills, best practice and learning

• systems that enable shared clinical governance, individual and team accountability, risk analysis and management'.21

ICUs where team performance is not so well developed are likely to have less effective processes and worse outcomes. Aspects of team leadership, coordination, communication and decision making can be measured against defined criteria, as can outcome indicators relating to patients and staff.22 Indicators of team performance include:

• adverse events/critical incidents

• staff retention.22

Identified deficiencies in teamworking can then be addressed, although some investment may be needed. A recent study focused on nurses as the main drivers of improvement in the ICU. Units engaged in a structured improvement programme entailing analysis of the prevailing culture in the department, followed by tailored training in teamworking, ways of achieving safer practice, and performance measurement.23 ICUs that completed this programme had significantly better outcomes than those that did not, even though both groups were required to use the same clinical protocols.23

Quality of care

Robust audit is the foundation of quality care. Potential indicators include pressure ulcer prevalence, nosocomial infection rates, errors in drug administration, and patient satisfaction.24 Nurses must measure the quality and take responsibility for the care that they deliver, although it should be appreciated that nursing care cannot be considered entirely separately from other variables that influence patient outcomes. The interdependence of different critical care personnel was illustrated in a multicentre investigation where interaction and communication between team members were more significant predictors of patient mortality than the therapies used or the status of the institution.25 Quality care depends on a collective interdisciplinary commitment to continuous improvement.26

Critical care nursing management

The nurse manager role is crucial to service performance. The most important priority is the challenge of attracting and retaining a flexible, effective and progressive nursing team that works well with other health care professionals in order to meet patient needs, but within a limited budget.

Staffing the critical care unit

The starting point for calculations of staffing requirements is the detailing of patient needs – and of the knowledge and skills that will be required to meet those needs – with an appreciation that there will be unpredictable variations over time (Box 6.1).

Patient need has many components, including:

• the severity and complexity of acute illness and chronic disease

• other physical characteristics (e.g. mobility, body weight, skin integrity, continence)

• mood and emotionality (e.g. anxiety, depression, motivation to engage in rehabilitation)

• the frequency and complexity of observation/monitoring and interventions

The staff resource includes members of the clinical team, the whole range of ancillary staff, and support services. Collectively, these personnel must be adequate to meet patient needs. This requires evaluation of:

• nursing numbers and skill mix

• interdisciplinary team skill mix, with consideration of variations in the availability of team members (e.g. doctors, respiratory/physiotherapists, equipment technicians out of hours).

The context of care is also significant, that is:

Other responsibilities

The manager is also responsible for:

• coordinated operational management of the area

• management of nursing pay and non-pay budgets

• dealing with complaints and investigating adverse incidents.

There are always dynamic political, social and economic forces bearing on the organisational objectives and resources of the hospital and the ICU. The nurse manager needs to understand these factors and how they influence the delivery of patient care and the maintenance of a healthy environment for individual and team development. The manager must be able to communicate the key issues to the whole team in the form of an agreed strategy and a clear, regularly updated operational plan for the department. There needs to be a working system that addresses and integrates the views and needs of all users of the service, including patients and their families. Such a system should enable a shared understanding of exactly what needs to be done in practice, and where each team member fits into the plan.

Externally, the manager represents the service and ensures that other disciplines and the bigger organisation are informed about critical care issues.

Teams perform most effectively when individuals believe that they are working toward some common and worthwhile goals. The principles of shared governance can be usefully applied in this perspective, whereby staff collectively review and learn from their own practices. This has to be in the context of:

Stress management and motivation

The ICU can be extremely stressful, demanding considerable cognitive, affective and psychomotor effort from staff. Supervisory and feedback arrangements should be in place to alleviate such demands, and to enable identification of staff members who are having difficulties at work. Studies of human resource practices in hospitals have found an association between the quantity and quality of staff appraisal and patient mortality, with organisations that emphasise training and teamworking having better outcomes.28 Regular individual performance reviews and formulation of development plans provide positive assurance and encouragement, and can identify specific personal requirements such as educational needs.

Providing staff at all levels with opportunities to feel that they can influence and perhaps modify the working environment tends to decrease stress and increase motivation. Flexibility to work in different ways at different times while still meeting the overall demands of the department is important. It is the manager's job to balance and meet the needs of staff, patients and the organisation. One method is to give staff choice regarding rostering, partly to help with work–life balance, but also so that the nurse can opt to work with particular patients for a period so as to practise certain skills, and to promote continuity of care. This can have real benefits for patients.

Nurse education

There are well-established educational programmes for critical care nurses, although the content and quality vary. There is a role for study of relevant philosophy, nursing theory and research methods, but the fundamental requirement is for learning that focuses on clinical practice and practical problem solving (Box 6.2).

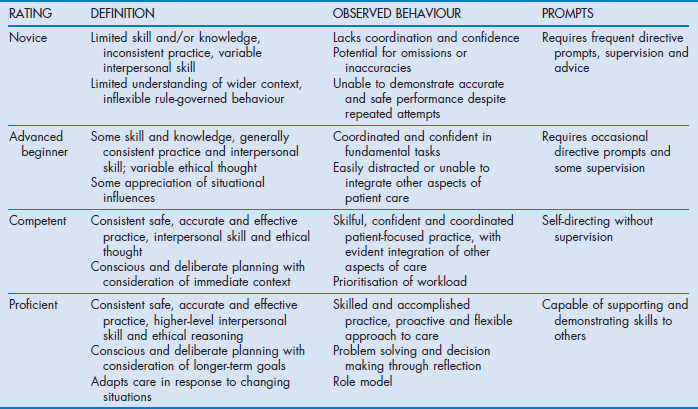

A competency framework can be used to structure descriptors of the skills, knowledge and attitudes needed to achieve specific patient outcomes. There needs to be consideration of both how individual actions are integrated into holistic care, and the role of independent clinical judgement. Developing nurses' critical thinking and decision-making skills are also important. Appraisal of learners' performance requires assessors to observe and question the nurse in practice; although this places significant demands on hard-pressed clinical areas. It may be that high-fidelity simulators can be used to test performance away from the practice setting in future.

Frameworks to identify different levels of performance have been developed – for example, based on Benner's novice-to-expert hierarchy (Table 6.1). UK critical care nursing organisations have described a three-stage version of the model; novice critical care nurses should spend up to 12 months acquiring the core competencies under supervision, then undertake a formal course of training (stage 2), and finally progressing to practice without direct supervision (stage 3).29

Critical care nursing research

Critical care services treat small numbers of patients at high cost. Critical care has great physical and psychological impact, but often uses somewhat untested methods. Patient outcomes are influenced by different organisational approaches, staff characteristics, varied working practices and treatment methods, as well as differences between patients themselves. Therefore, a range of quantitative and qualitative investigative procedures is needed to gain an understanding of the issues. The approach chosen depends on the nature of the research question, and also the objectives of the researcher and the resources available.

Reviewing research

The methods used to appraise research depend partly on the type of work under review. The following questions may help clarification:

• Justification for the research: are the background and rationale of the study clearly established?

• Scientific content: is there a specific question/hypothesis?

• Originality: is it a new idea, or re-examining an old problem differently or better?

• Methodology and study design: are the methods appropriate and are they likely to produce an answer to the question? For example:

– comparisons of different treatments generally require quantitative measurements of particular end-points (e.g. the dose of a drug needed to achieve a target physiological variable)

– understanding how an individual thinks or feels usually involves analysis of qualitative material (e.g. data from interviews with patients and families).

• Is the research method described in a way that can be readily understood, and replicated?

• Are the relevant results shown? Are data given that provide details of the individuals under investigation and details of how representative these might be of a larger population?

• Is the analysis appropriate and is the power of the study adequate? (This is determined by the numbers involved and the size of the difference being examined.)

• Interpretation and discussion: are the conclusions and comments reasonable in the light of the results? Do the conclusions follow from the analysis?

• Are any references to background literature comprehensive and appropriate?

• What can be taken from the study – that is, what value does the study have in terms of supporting or developing clinical practice?

• What is the overall impression of the work? Is it credible? Is the presentation clear and informative?

• If evaluating a paper, has the work undergone proper peer review?

Undertaking a research project

Stage 1: identify and clarify the topic to be examined

Research is most valued when it is relevant to practice. The researcher is more likely to gain support for investigation of high-risk and high-cost processes. Many everyday methods and treatments warrant examination too, particularly when there are significant variations in practice. The researcher should determine how the topic of interest might be described in a measurable way, and formulate the investigation as a question, with consideration of how answers can be obtained.

Stage 2: gather relevant background information

It is important to collect information that enables an understanding of the issues under investigation, and helps justify performing the study. Hospital libraries are useful, not least because there may be staff members who can give advice about the project. Indexes for journals and books are in print- and computer-based formats, with databases and texts also available through the internet. A good starting point is Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.co.uk//). This uses a broad approach to locating articles across many disciplines and sources. Specific medical/nursing websites include:

• PubMed, from the US National Library of Medicine (www.nlm.nih.gov/), with access to the MEDLINE (Medical Literature, Analysis, and Retrieval System Online) biomedical database

• the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) at www.ebscohost.com/biomedical-libraries/the-cinahl-database

• the Cochrane Collaboration of systematic reviews of health care interventions (www.cochrane.org)

• EMBASE (www.embase.com/), which is particularly good for pharmacological information.

The researcher must also evaluate the quality of the information gathered. Different types of research are traditionally held to have different weights (e.g. results obtained from randomised controlled trials are considered to be high-grade evidence, whereas observational studies are deemed less useful). This hierarchy is not always applicable and may devalue some valuable work, but it does emphasise the need to critically examine the credibility of research.

Stage 4: collect the data

This is relatively simple provided that the data items to be collected are clearly defined. A common pitfall is to collect lots of unnecessary data and lose the focus of the original question. Data should be collected in a manageable format/database.

Stage 5: organise the data

By this stage, a large amount of material may have been gathered. It is important that:

Stage 6: present and explain the data

Presentation can take many forms, but it is always necessary to:

• describe the research method so that it is clear what was done

The conclusions should follow from the analysis without inappropriate extrapolations. Any applications to clinical practice should be highlighted. The report must be presented succinctly and in a constructive manner, but with any shortcomings or problems in the study acknowledged. The goal is that the reader can understand the methodology and how the results were interpreted, as well as any limitations of the work. The main point of research is to share what has been learnt.

Stage 7: evaluate the project

The final phase is reflective. Conducting research is a process that can always be improved. Constructive feedback from colleagues should be sought. The researcher should review what has been learnt from the process as well as from the results of the study, and consider how the work might be further developed in the future.

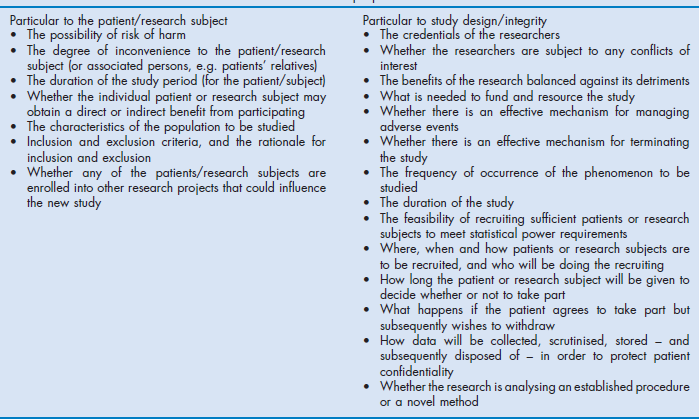

Research ethics

The practitioner must always consider the ethical issues associated with conducting research. It may be necessary to submit an application for approval to an ethics committee. There are local differences in the process of obtaining ethical approval for research on humans, but most systems incorporate the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (see the World Medical Association website at www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html). The ethics committee looks beyond the stated necessity and significance of the proposed research to evaluate a range of matters particular to the patients who may be involved, and to aspects of the study design. Some of these issues are summarised in Box 6.3.

References

1. British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Critical Care Networks National Nurse Leads, Royal College of Nursing Critical Care and In-flight Forum, Standards for nurse staffing in critical care units. British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2009. www. ics. ac. uk/professional/standards_safety_quality/standards_and_guidelines/nurse_staffing_in_critical_care_2009

2. Chinn, PL, Kramer, MK. Integrated Theory and Knowledge Development in Nursing, 8th edn. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2011.

3. Benner, P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice (commemorative edn). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2001.

4. Ball, C, McElligot, M. “Realising the potential of critical care nurses”: an exploratory study of the factors that affect and comprise the nursing contribution to the recovery of critically ill patients. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003; 19(4):226–238.

5. Watt, B. Patient: the True Story of a Rare Illness. London: Viking; 1996.

6. Karlsson, V, Bergbom, I, Forsberg, A. The lived experiences of adult intensive care patients who were conscious during mechanical ventilation: a phenomenological–hermeneutic study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012; 28(1):6–15.

7. Hillman, KM, Bishop, G, Flabouris, A. Patient examination in the intensive care unit. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002:942–950.

8. Shirey, MR. Nursing practice models for acute and critical care: overview of care delivery models. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008; 20(4):365–373.

9. Warfield, C, Manley, K. Developing a new philosophy in the NDU. Nurs Stand. 1990; 4(41):27–30.

10. University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. UCLH vision, values and objectives. Online. Available www. uclh. nhs. uk/aboutus/wwd/Pages/Visionandobjectives. aspx. [(accessed 12 January 2013)].

11. Rothschild, JM, Hurley, AC, Landrigan, CP, et al. Recovery from medical errors: the critical care nursing safety net. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006; 32(2):63–72.

12. Coombs, M, Lattimer, V. Safety, effectiveness and costs of different models of organising care for critically ill patients: literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007; 44(1):115–129.

13. Henneman, EA, Gawlinski, A, Giuliano, KK. Surveillance: A strategy for improving patient safety in acute and critical care units. Crit Care Nurse. 2012; 32(2):e9–e18.

14. Penoyer, DA. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes in critical care: a concise review. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38(7):1521–1528.

15. Blackwood, B, Alderdice, F, Burns, K, et al. Use of weaning protocols for reducing duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill adult patients: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011; 342:c7237.

16. Endacott, R, Boulanger, C, Chamberlain, W, et al. Stability in shifting sands: contemporary leadership roles in critical care. J Nurs Manag. 2008; 16(7):837–845.

17. Allen, K, McAleavy, JM, Wright, S. An evaluation of the role of the Assistant Practitioner in critical care. Nursing in Critical Care. 2013; 18(1):14–22.

18. Cullinane, M, Findlay, G, Hargraves, C, et al. An Acute Problem? A Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. London: National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death; 2005.

19. Watson, W, Mozley, C, Cope, J, et al. Implementing a nurse-led critical care outreach service in an acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2006; 15(1):105–110.

20. Harrison, DA, Gao, H, Welch, CA, et al. The effects of critical care outreach services before and after critical care: a matched-cohort analysis. J Crit Care. 2010; 25(2):196–204.

21. Department of Health-Emergency Care Team. Quality Critical Care: Beyond ‘Comprehensive Critical Care’: A Report by the Critical Care Stakeholder Forum. London: Department of Health-Emergency Care Team; 2005.

22. Reader, TW, Flin, R, Mearns, K, et al. Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37(5):1787–1793.

23. Marsteller, JA, Sexton, JB, Hsu, YJ, et al. A multicenter, phased, cluster-randomized controlled trial to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in intensive care units*. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40(11):2933–2939.

24. Maben, J, Morrow, E, Ball, J, et al. High Quality Care Metrics for Nursing. London: National Nursing Research Unit, King's College London; 2012.

25. Tarnow-Mordi, WO, Hau, C, Warden, A, et al. Hospital mortality in relation to staff workload: a 4-year study in an adult intensive care unit. Lancet. 2000; 356(9225):185–189.

26. Curtis, JR, Cook, DJ, Wall, RJ, et al. Intensive care unit quality improvement: a ‘how-to’ guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34(1):211–218.

27. Bray, K, Wren, I, Baldwin, A, et al. Standards for nurse staffing in critical care units determined by: The British Association of Critical Care Nurses, The Critical Care Networks National Nurse Leads, Royal College of Nursing Critical Care and In-flight Forum. Nurs Crit Care. 2010; 15(3):109–111.

28. West, MA, Guthrie, JP, Dawson, JF. Reducing patient mortality in hospitals: The role of human resource management. J Organiz Behav. 2006; 27(7):983–1002.

29. The National Competency Working Group, National Competency Framework for Critical Care Nurses. Critical Care Networks National Nurse Leads, 2013. www. baccn. org. uk/news/121105. asp