Disorder of Speech and Language

Summary

Speech is the aspect of language that corresponds to the mechanical and articulatory functions that allow language to be vocalized, whereas language is itself a complex system based on a number of elements including phonemes, syntactic structure, semantics, prosody and pragmatics, all designed to aid communication and to encode facts in memory. Abnormalities of speech are common in neurology but rare in psychiatry. Language and thinking disorders are intricately affected in psychiatric disorders, particularly in schizophrenia. The actual relationship between thinking and language is yet to be fully elucidated.

To speak is not only to utter words, it is to propositionize. A proposition is such a relation of words that it makes one new meaning.

J. Hughlings Jackson (1932)

It is very obvious that the functions of thinking and speaking overlap and cannot be readily separated from each other; at the same time, they are clearly different. The contents of this chapter cannot be considered in isolation from its predecessor, although this one considers speech and language from a different perspective.

Maher (1972) proposed a model that attempted to demonstrate the link between thinking and the behaviour of speech in language:

conceptualizing the relationship between language and thought. The model might be likened to a typist copying from a script before her. Her copy may appear to be distorted because the script is distorted although the communication channel of the typist's eye and hand are functioning correctly. Alternatively, the original script may be perfect, but the typist may be unskilled, making typing errors in the copy and thus distorting it. Finally, it is possible for an inefficient typist to add errors to an already incoherent script. Unfortunately, the psychopathologist can observe only the copy (language utterances): he cannot examine the script (the thought). In general most theorists concerned with schizophrenic language have accepted the first of the three alternatives, namely that a good typist is transcribing a deviant script. The patient is correctly reporting a set of disordered thoughts. As Critchley put it: ‘Any considerable aberration of thought or personality will be mirrored in the various levels of articulate speech – phonetic, phonemic, semantic, syntactic and pragmatic’. The language is a mirror of the thought.

(p. 3)

The script is likened to thought and the typist to language. Most clinicians have taken the view that language closely mirrors thought and see the primary abnormality as the thinking disorder (Beveridge, 1985). Disordered language is then seen as merely a reflection of this underlying disturbance, with diagnosis of thought disorder only possible on the basis of what the patient says. Some of the more recent linguistic theories used for the analysis of schizophrenic speech contradict the primacy of thinking.

The assumption that language directly mirrors thought can be challenged (Newby, 1995). There is a tradition that argues that language itself structures thinking and concepts, and determines how the world is understood. This view derives from the works of Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941). In essence, the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis says that language influences cognition. There is very limited empirical support for this view, and Pinker (1994) concludes that ‘the representations underlying thinking, on the one hand, and the sentences in a language, on the other, are in many ways at cross-purposes. … People do not think in English or Chinese or Apache; they think in a language of thought. This language of thought probably looks a bit like all these languages; presumably it has symbols for concepts, and arrangements of symbols that correspond to who did what to whom’. This radical view contradicts the point-to-point relationship between language and thought implicit in Maher's proposition (see above) and the linguistic determinism of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis.

The relationship between thinking and language is as complicated for organic disorders as it is for schizophrenia: there can be quite marked disturbance in the use of language with no apparent thought disorder. This is revealed in the rare isolated abnormalities of specific function of language described in this chapter. An understanding of how the healthy person expresses thoughts in language can be achieved only by study of the normal development of language. This is outside the scope of this book but is discussed in relation to perception in Carterette and Friedman (1976).

Language is built up of a number of elements. Phonemes are the most basic sounds that are available for use in language, and any particular language, such as English, uses only a limited repertoire of phonemes. The repertoire used in English may share only a limited overlap with that used, for example, in Yoruba. Morphemes are produced from phonemes and are the smallest meaningful unit of a word, and combinations of morphemes make up words. A morpheme may be a word such as ‘do’ or ‘un’. Syntax (grammar) is the allowable combination of words in phrases and sentences and includes the rules that determine word order. Semantics are the meanings that correspond to the words and include the meaning of all possible sentences. Prosody refers to the modulation of vocal intonation that influences accents, and also the literal and emotional meanings of words and sentences. The pragmatics of language are the ways that language is used in practice. This is a relatively new area of study. It refers to the multiple potential meanings of any utterance, which requires knowledge of context and of the speakers for full interpretation. For example, the sentence ‘this room is cold’ can have any of several meanings depending on the identity of the speaker, the context of the utterance and who is being addressed, that is the social or relative distance of the addressee. It is perhaps important to distinguish between language and speech for our purpose. Speech is the aspect of language that corresponds to the mechanical and articulatory functions that allow language to be vocalized. Thus, for language to become speech the vocal cords, the palate, the lips and the tongue need to perform a complex and synchronized dance of intricate steps. The dissociation between poorly articulated speech and intact language indicates that these two functions are separate.

Chomsky's theory of language is the most influential (Chomsky, 1986). Essentially, Chomsky argued that language is like an instinct, and furthermore that ‘every sentence that a person utters or understands is a brand new combination of words, appearing for the first time in the history of the universe. Therefore a language cannot be a repertoire of responses; the brain must contain a recipe or programme that can build an unlimited set of sentences out of a finite list of words. The programme may be called a mental grammar’ (Pinker, 1994). In addition to this, children rapidly develop these complex grammars without formal instruction. This suggests that they must be innately endowed with a plan common to the grammars of all languages, a universal grammar. How language develops, how word meaning is learned and the neuropsychology of language are all areas of increasing study.

Speech Disturbances

This subject is dealt with in textbooks of neurology and has been reviewed by Critchley (1995); it is only summarized here. Many abnormalities, such as paraphasia, have both organic and psychogenic causes (see above); diagnosis will require full medical and psychiatric history and neurological and mental state examination.

Aphonia and Dysphonia

Aphonia is the loss of the ability to vocalize; the patient talks only in a whisper. Dysphonia denotes impairment with hoarseness but without complete loss of function. It occurs with paralysis of the ninth cranial nerve or with disease of the vocal cords.

Aphonia may also occur without organic disease in dissociative aphonia, not uncommon as a presentation among ear, nose and throat outpatients. Such a patient may speak in a ‘stage whisper’; phonation may fluctuate according to the response of those the person is addressing.

Dysarthria

Disorders of articulation may be caused by lesions of the brainstem such as bulbar and pseudobulbar palsy. It may also occur with structural or muscular disorders of the mouth, pharynx, larynx and thorax. Idiosyncratic disorders of articulation are sometimes seen in schizophrenia and also, perhaps, with personality disorders consciously produced.

Stuttering and Stammering

These have in the past been enquired about in the psychiatric history under neurotic disturbances of childhood, along with such behaviour as nail biting. However, psychogenic aetiology has certainly now been proved, and any association with neuroticism may well be secondary to the barriers in communication that stuttering causes.

Logoclonia

This describes the spastic repetition of syllables that occurs with parkinsonism (Scharfetter, 1980). The patient may get stuck using a particular word.

Echolalia

The patient repeats words or parts of sentences that are spoken to him or in his presence. There is usually no understanding of the meaning of the words. It is most often demonstrated in excited schizophrenic states, with mental retardation and with organic states such as dementia, especially if dysphasia is also present.

Changes in the Volume and Intonation of Speech

Many depressed patients speak very quietly with a monotonous voice. Manic patients often speak loudly and excitably with much variation in pitch. Excited patients with schizophrenia may also speak loudly; intonation and stresses on words may be idiosyncratic and inappropriate. None of these modes of behaviour has diagnostic significance. The speed and flow of talk mirrors that of thought and has been dealt with in Chapter 9.

Unintelligible Speech

Speech may be unintelligible for several reasons, and most of the abnormalities described here, if taken to extremes, will result in incomprehensibility.

▪ Dysphasia may be so profound that, although syllables are produced, speech is unintelligible.

▪ Paragrammatism (disorder of grammatical construction) and incoherence of syntax may occur in several disorders. Recognizable words may be so deranged in their sentences as to be meaningless – word salad, as occurs in schizophrenia. In mania, the speed of association may be so rapid as to disrupt sentence structure completely and render it meaningless, while in depression retardation may so inhibit speech that only unintelligible syllables, often of a moaning nature, are produced.

▪ Private meaning may occur in schizophrenia with the use of (a) new words with an idiosyncratic, personal meaning – neologisms; (b) stock words and phrases in which existing words are used with special individual symbolic meaning; or (c) a private language that may be spoken (cryptolalia), or written (cryptographia).

Organic Disorders of Language

Dysphasic symptoms are probably more useful clinically than any other cognitive defect in indicating the approximate site of brain pathology (David et al, 2007). However, the auditory, visual and motor mechanisms of speech are spread through several different parts of the brain; often, several functions are affected and lesions are usually diffuse, and thus precise brain localization is not often possible. Ninety per cent of right-handed people without any brain damage have speech located in the left hemisphere, and 10 per cent have right hemisphere speech. Among those who are left-handed or ambidextrous, 64 per cent have left hemisphere speech, 20 per cent right hemisphere and 16 per cent bilateral speech representation.

Sensory Dysphasia

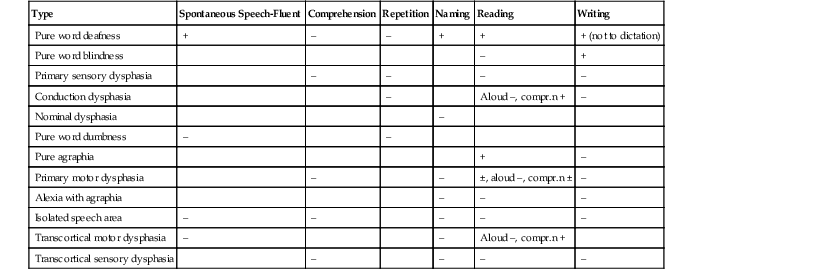

The terms aphasia and dysphasia are often used interchangeably. However, aphasia implies the loss of language altogether, and dysphasia impairment of, or difficulty with, language. Dysphasia is conventionally divided for classification purposes into sensory (receptive) and motor (expressive) types. Very frequently, there is a global impairment of language with evidence of impairment of both elements. Table 10.1 summarizes some of the abnormalities that occur with the different aspects of language that are impaired.

TABLE 10.1

Impairment of language function with different types of dysphasia

| Type | Spontaneous Speech-Fluent | Comprehension | Repetition | Naming | Reading | Writing |

| Pure word deafness | + | – | – | + | + | + (not to dictation) |

| Pure word blindness | – | + | ||||

| Primary sensory dysphasia | – | – | – | – | ||

| Conduction dysphasia | – | Aloud –, compr.n + | – | |||

| Nominal dysphasia | – | |||||

| Pure word dumbness | – | – | ||||

| Pure agraphia | + | – | ||||

| Primary motor dysphasia | – | – | ±, aloud –, compr.n ± | – | ||

| Alexia with agraphia | – | – | – | |||

| Isolated speech area | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Transcortical motor dysphasia | – | – | Aloud –, compr.n + | |||

| Transcortical sensory dysphasia | – | – | – | – |

Compr.n, comprehension.

(After Lishman, 1997, with permission of Blackwell Scientific.)

Pure Word Deafness (Subcortical Auditory Dysphasia)

In pure word deafness, the patient can speak, read and write fluently, correctly and with comprehension. He cannot understand speech, even though hearing is unimpaired for other sounds; he hears words as sounds but cannot recognize the meaning even though he knows that they are words. This is therefore a form of agnosia (lack of recognition) for the spoken word.

Pure Word Blindness (Subcortical Visual Aphasia)

The patient with pure word blindness can speak normally and understand the spoken word; he can write spontaneously and to dictation but cannot read with understanding (alexia). The condition is therefore agnosic alexia without dysgraphia. He may have more difficulty with printed than hand written script. Such a patient will also suffer a right homonymous hemianopia (loss of the right half of the field of vision in both eyes) and an inability to name colours even though they can be perceived.

Primary Sensory Dysphasia (Receptive Dysphasia)

Patients with primary sensory dysphasia are unable to understand spoken speech, with loss of comprehension of the meaning of words and of the significance of grammar. Hearing otherwise is not impaired. Consequent on this deficit in the auditory association cortex (Wernicke's area), there is also impairment of speech, writing and reading. Speech is fluent, with no appreciation of the many errors in the use of words, syntax and grammar.

Conduction dysphasia could be considered to be a type of sensory dysphasia in which sensory reception of speech and writing are impaired, in that the patient cannot repeat the message although he can speak and write. If he is questioned on the message, he is able to give ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers correctly, thus demonstrating comprehension. There are marked errors of grammar and syntax (syntactical dysphasia).

Nominal Dysphasia

The patient with nominal dysphasia is unable to produce names and sounds at will. He may be able to describe the object and its function and to recognize the name when presented: a patient described a watch as a ‘clock vessel’. Typically, ‘empty’ nouns such as ‘thing’ and ‘object’ are used frequently while ‘distinguishing’ nouns rarely. Speech is flat, the structure of sentences generally correct and understanding unimpaired.

Jargon Dysphasia

In jargon dysphasia speech is fluent, but there is such gross disturbance to words and syntax that it is unintelligible. The intonation and rhythm of speech are retained. This is considered a severe type of sensory dysphasia; there is failure to evaluate the patients' own speech, in that patients are not emotionally disturbed when listening to recordings of their own grossly impaired speech.

Motor Aphasia

Pure Word Dumbness

The patient with pure word dumbness understands spoken speech and writing and can respond to comments. Writing is preserved but speech is indistinct and cannot be produced at will. There is no local disturbance of muscles required in speaking, and the disability is an apraxia limited to movements required for speech.

Pure Agraphia

Pure agraphia is an isolated inability to write which may also occur with unimpaired speech (agraphia without alexia); there is normal understanding of written and spoken material. This is the equivalent for writing of pure word dumbness in speech.

Primary Motor Dysphasia

In primary motor dysphasia there is disturbance to the processes of selecting words, constructing sentences and expressing them. Speech and writing are both affected, and there is difficulty in carrying out complex instructions, even though understanding for both speech and writing may be preserved. The patient finds it difficult to choose and pronounce words, and speech is hesitant and slow; he recognizes his errors, tries to correct them and is clearly upset. Gesture may be used to replace verbal communication. Speech is attempted and recognized as spoken words, but words are omitted, sentences shortened and perseveration occurs.

Alexia with Agraphia

Visual aspects of language are construed as being more complex than auditory, in that visual schemata are required – ‘seeing the written word inside his head’, in addition to auditory – ‘hearing the words in one’s head’. In alexia with agraphia, the patient is unable to read or write, but speaking and understanding speech are preserved. Alexia in this condition is similar to that of pure word blindness: the patient cannot understand words that are spelt out aloud, showing that he is effectively illiterate because of disturbance of the visual symbolism of language.

Isolated Speech Area

Impaired comprehension may occur with slow, hesitant speech in an abnormality in which it is assumed that the anatomical Wernicke's and Broca's areas and the connections between them are intact but connections from other parts of the cortex with this language system are disturbed. Two types, expressive and receptive, are described: transcortical motor dysphasia and transcortical sensory dysphasia.

Most frequently, of course, with dysphasia, there is a mixture of expressive and receptive elements and the clear syndromes cannot be demonstrated, but their significance is partly theoretical in demonstrating the range of anatomical lesions and the specificity of resultant symptoms. This description has been exclusively concerned with the symptoms; precise description of the anatomical lesions and of associated neurological symptoms is outside our scope. It is important to distinguish the phenomena of dysphasia, perhaps with neologisms and defects of syntax, from the word salad of schizophrenia with superficially similar defects of language. Verbigeration describes the repetition of words or syllables that expressive aphasic patients may use while desperately searching for the correct word.

Mutism

Mutism, refraining from speech during consciousness, is an important sign in psychiatric illness with an extensive differential diagnosis. Eliciting the history and mental state becomes impossible in a mute patient. All the major categories of psychiatric disorder may manifest mutism: learning disability, organic brain disease (sometimes drug-related), functional psychosis and neurosis and personality disorder. Some more specific causes include depressive illness, catatonic schizophrenia and dissociative disorder. Mutism occurs as an essential element of stupor (Chapter 3), and it is necessary to assess the level of consciousness as part of a full neurological examination for all patients with this sign. If there is no lowering of consciousness, as in functional psychoses and neuroses, it is likely that the mute patient understands everything that is said around him. As well as specific brain disorders, the causes of stupor include general metabolic disorders that also affect the brain, such as hepatic failure, uraemia, hypothyroidism and hypoglycaemia.

Schizophrenic Language Disorder

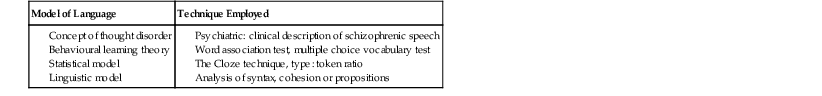

Defective communication in language is the defining characteristic of schizophrenia according to Crow (1997), and it is associated with genetic variation at the time language was acquired by Homo sapiens. The use of language by people with schizophrenia can differ from that in normal people, and this difference can be subtle and unrelated to positive symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. There is good reason to believe that the abnormalities of language use are associated with thought disorder. The precise nature of the language abnormality has so far defied clarification, and this account is provisional; it describes the way some of the phenomena have been viewed and conceptualized. There is no single explanatory theory that unifies the disparate abnormalities that have been observed and described. Investigation into language disorder may be ascribed to one of the four models shown in Table 10.2.

TABLE 10.2

Models for investigating language disorder in schizophrenia

| Model of Language | Technique Employed |

(After Beveridge, 1985, with permission.)

Clinical Description and Thought Disorder

The only unequivocal demonstration of disorder of thinking can be through language. Thought disorder may be revealed in the flow of talk (as in Chapter 9), disturbed content and use of words and grammar, and in the inability to conceptualize appropriately. Critchley (1964) considered that the ‘causation of schizophrenic speech affection lies in an underlying thought disorder, rather than in a linguistic inaccessibility’. Some of the ways in which clinicians have categorized schizophrenic thought disorder manifesting in speech are linked in Table 10.3.

TABLE 10.3

Categorization of thought disorder in speech

| Clinician | Categorization |

| Kraepelin | Akataphasia |

| Bleuler | Loosening of associations |

| Gardner | Form of regression |

| Cameron | Asyndesis |

| Goldstein | Concrete thinking |

| Von Domarus | Defect of deductive reasoning |

| Schneider | Derailment, substitution, omission, fusion and drivelling |

The German psychopathological literature on schizophrenic language and speech disorders was concerned with the rules of language dysfunction; it consistently reported the patient's uncertainty in choosing the correct metaphorical level in communication (Mundt, 1995). Kraepelin (1919) defined akataphasia as a disorder in the expression of thought in speech. Loss of the continuity of associations, which implied incompleteness in the development of ideas, was the first of the functions included among the fundamental symptoms of schizophrenia by Bleuler (1911).

Gardner (1931) considered thought disorder to be a form of regression. Cameron (1944), in describing asyndesis, considered there to be an inability to preserve conceptual boundaries and a marked paucity of genuinely causal links. He gave the example of a patient who, given these alternatives, completed the sentence ‘I get warm when I run because …’ with all the words: ‘quickness, blood, heart of deer, length, driven power, motorized cylinder, strength’. The patient was prone to use imprecise expressions – metonyms, for example a patient said he was alive;

Because you really live physically, because you have menu three times a day; that's the physical [What else is there beside the physical?] Then you are alive mostly to serve a work from the standpoint of methodical business

and over-inclusive thinking in which a loose association of concepts that were related in some way to the dominant theme became interwoven into responses, for example;

[The wind blows] Due to velocity. [Question repeated] Due to loss of air, evaporation of water. [What gives the velocity?] the contact of trees, of air in the trees

Concrete thinking, a term denoting an inability to think abstractly was proposed by Goldstein (1944), but the validity of this has been challenged by Payne et al. (1959). Allen (1984) considers that speech-disordered patients with schizophrenia produce evidence of concrete thinking, thinking without inferring and restricted to what is explicitly stated, while non-speech-disordered patients with schizophrenia do not. When the thematic organization of speech was analyzed for patients with positive speech disorder (incoherence of speech) or negative speech disorder (poverty of speech), there was no difference found: speech-disordered patients, positive as well as negative, showed cognitive restriction and produced fewer inferences than non-speech-disordered patients.

A deficiency in the logic of deductive reasoning in schizophrenia was suggested by Von Domarus (1944). Some of the abnormalities of thinking expressed in speech observed by Schneider have been discussed in Chapter 9.

An attempt has been made by Andreasen (1979) to classify the description of patients' cognitive and linguistic behaviour on the phenomena demonstrated without making inferences about concepts of ‘global’ thought disorder; these abnormalities occur in both mania and schizophrenia. Some types of thought disorder, such as neologism and blocking, occurred too infrequently to have diagnostic significance. However, she found high reliability between raters with many types of thought disorder and also discrimination between different psychotic illnesses. Derailment, loss of goal, poverty of content of speech, tangentiality and illogicality were particularly characteristic of schizophrenia. Derailment implies loosening of association so that ideas slip on to either an obliquely related, or totally unrelated, theme. Loss of goal is the failure to follow a chain of thought through to its natural conclusion. Poverty of content of speech includes poverty of thought, empty speech, alogia, verbigeration and negative formal thought disorder; patients' statements convey little information and tend to be vague, over-abstract, over-concrete, repetitive and stereotyped. Tangentiality means replying to a question in an oblique or even irrelevant manner. Illogicality implies drawing conclusions from a premise by inference that cannot be seen as logical.

Misuse of Words and Phrases

The patient with schizophrenia sometimes shows misuse of words in that he has, in the terminology of Kleist (1914), a defect of word storage. He has a restricted vocabulary and so uses words idiosyncratically to cover a greater range of meaning than they usually encompass. These are called stock words or phrases, and their use will sometimes become obvious in a longer conversation in which an unusual word or expression may be used several times. For example, a patient used ‘dispassionate’ as a stock word, and used it frequently with a bizarre and idiosyncratic meaning in the course of a few minutes' speech. A woman who was delusionally concerned that the police were intruding into her private affairs interspersed her conversation, often bizarrely, with the expression ‘confidentially speaking’.

This abnormality appears partly to reflect a poverty of words and syntax and also an active tendency for words or syllables by association to intrude into thoughts, and therefore speech, soon after utterance. In the sample of speech in Chapter 9, the following words could be seen as stimuli and responses, by intrusion: ‘means’ – ‘ways’, ‘opens’ – ‘closed’, ‘holding back the truth’ – ‘by no means will I speak’, ‘written questions’ – ‘by means of writing’, ‘miracle’ – ‘Holyland’. They also appear to be stock words or phrases in that they are used with greater frequency and with a greater range of meaning than is normal and correct.

Words carry a semantic halo, that is, their constellation of associations is greater than just the dictionary meaning of the word. A boy aged 16 steals an apple. If I call him ‘a trespasser’, it has biblical associations; ‘a criminal’ suggests a greater degree of viciousness than the action merits; ‘a delinquent’ is readily associated with his youthfulness because of the phrase ‘juvenile delinquent’. The constellations of associations in patients are disordered in that they often make apparently irrelevant associations. These may be explained by misperception of auditory stimuli with specific inattention; the actual mediation of associations in patients with schizophrenia may be similar to that in healthy people. This comes some way to explaining why the associations seem appropriate subjectively to the patient himself, as he does not realize that he has misperceived the cue: it seems reasonable to him but is quite irrelevant to the interviewer. To quote Maher, ‘What seems to be bizarre is not the nature of the associations that intrude into the utterance, but the fact that they intrude at all’ (Maher 1972, p. 9).

Among the disorders of words, neologism is well recognized. A patient believed that his thoughts were influenced from outside himself by a process of ‘telegony’. Although such a word does actually exist, the patient had no notion of this nor what it meant. He created the word to describe a unique experience of his for which no adequate word existed. A 47-year-old male patient with schizophrenia and expansive mood described himself thus: ‘I am the triplicate actimetric kilophilic telepathic multibillion million genius’ – which does suggest a certain grandiosity!

The unintentional puns of schizophrenia have been explained by Chapman et al. (1964). If a word has more than one meaning, it is likely that one usage is dominant. For example, the majority of people, in most contexts, would be more likely to use the word ‘bay’ to refer to an inlet of the sea than to a tree, the noise a hound makes, the colour of a horse, an opening in a wall, the second branch of a stag's horn, an uncomfortable place at which to stand or even, phonetically, a Turkish governor! There is a marked tendency in schizophrenia to show intrusion of the dominant meaning when the context demands the use of a less common meaning. Chapman et al. (1964) used a sentence such as ‘the tennis player left the court because he was tired’ and asked patients with schizophrenia to interpret its meaning with one of three different explanations: one referring to a tennis court, one to a court of law and one altogether irrelevant. An analysis of responses shows that dominant meanings, here a court of law, intrude into the responses quite frequently, but intrusion of minor meanings is less frequent.

Maher has described disorder of language in schizophrenia in which intrusion occurs through clang associations with the initial syllable of a previous word: ‘the subterfuge and the mistaken planned substitutions’ (Maher 1972, p. 13). This is unlike the clang associations that occur normally in poetry and in humour and also in manic speech, in which the clang occurs in terminal syllables. The repetitiveness of speech disorder is also thought to be associated with the intrusion of associations: the normal process of eliminating irrelevant associations does not take place, so that a word in a clause will provoke associations by pun, clang and ideational similarity. When that clause is completed, a syntactically correct clause may then be inserted, disrupting meaning but demonstrably associated with that previous word or idea.

Maher considers that an inability to maintain attention may account for the language disturbances seen in some patients. Disturbed attention allows irrelevant associations to intrude into speech, similarly to the disturbance affecting the filtering of sensory input. In this theory, normal coherent speech is seen as the progressive and instantaneous inhibition of irrelevant associations to each utterance, and so the determining tendency proceeds with the active elimination of those associations that are not goal-directed. This is but one of many potential explanations for the observed abnormalities.

Destruction of Words and Grammar

Alogia is a term used to describe negative thought disorder, or poverty of thoughts as expressed in words. Correspondingly, paralogia is used to describe positive thought disorder, or the intrusion of irrelevant or bizarre thought. Paraphasia is a destruction of words with interpolation of more or less garbled sounds. Although the patient is only able to produce this non-verbal sound, it clearly has significance or meaning to him. Literal paraphasia is gross misuse of the meaning of words to such an extent that statements no longer make any sense. Verbal paraphasia describes the loss of the appropriate word but the statements are still meaningful, for example a patient described a chair as ‘a four-legged sit-up’.

Disturbances in the words and their meanings are much more common in schizophrenia than disturbance of grammar and syntax. However, grammar is also sometimes altered; the loss of parts of speech is described as agrammatism. Adverbs are occasionally lost, resulting in coarsening and poverty of sentences, a form of telegramese. For example, ‘rich table is worn; the woman is rich to write; son is also lamentation’. This, as well as showing stock words (rich – lamentation), shows loss of parts of speech, for example the indefinite article. The meaning is more disjointed than the grammar. Paragrammatism occurs when there is a mass of complicated clauses that make no sense in achieving the goal of thought. However, the individual phrases are, in themselves, quite comprehensible.

It seems probable that the rules of syntax are preserved in schizophrenia long after a marked disturbance in the use of words, so that, if in the preceding clause an intrusive association were to replace the word ‘rules’, the word used would probably, correctly, be a noun. For instance, the patient above might have said in this context ‘the lamentations of syntax are …’

In addition to the observed abnormalities described above there are suggestions that patients with schizophrenia demonstrate lack of use of cohesive ties in discourse (see McKenna and Oh, 2005 for a full discussion). Cohesive ties in discourse are devices that are utilized to link sentences together, so that speech is not merely a collection of unrelated sentences. There are four main types of cohesive ties: reference, conjunction, lexical cohesion and ellipsis. References in English are personal pronouns such as ‘he’, ‘she’, ‘they’, ‘it’; demonstratives are such words as ‘this’ and ‘that’; and comparatives such terms as ‘smaller than’, ‘equal to’, etc. In the following sentences ‘I met Peter yesterday. He was wearing a dark suit’. ‘He’ is a reference tie. In the sentence ‘She went to the High Street this morning and bought some cakes from the supermarket’. ‘And’ is a conjunction tie. A lack of use of cohesive ties means that the listener in dialogue with a patient with schizophrenia can have difficulty following the speech of the patient.

Psychogenic Abnormalities

Andreasen (1979) showed that the abnormalities of language present in schizophrenia were also present in mania. Furthermore, McKenna and Oh (2005) make the case that there is a continuum of language or thought disturbance from schizophrenia through mood disorder to organic disorders such as epilepsy and fronto-temporal dementia. The point that McKenna and Oh want to emphasize is that language abnormalities in schizophrenia have a neurological substrate, linking the observed disturbances to aphasia, a return to the ideas that originated with Kleist in the 20th century.

Manic speech has been analyzed, and the speech and number of associations demonstrated in flight of ideas and pressure of talk is seen in the greater number of cohesive links occurring in manic speech. The content of depressive speech is, of course, influenced by the mood state, and so also is the choice of words. Sentences tend to be short and have fewer and simpler associations, with retardation.

Hysterical mutism may occur as an abnormal reaction to stress. A man aged 35 had been unable to tolerate the continual nagging from his wife and her two sisters who lived with them. One day, after heavy drinking the previous evening, he smashed his wife's furniture at home and then became mute for 24 hours. He was eventually referred from the accident and emergency department to the psychiatric ward, and speech returned gradually over the next two to three days without other treatment.

With the phenomenon of approximate answers (Chapter 5), the patient gives an incorrect answer to a simple question: ‘How many legs has a sheep?’ – ‘Five’. This is, according to Anderson and Mallinson (1941), ‘a false response to the examiner’s question where the answer, although wrong, indicates that the question had been grasped’. This symptom may occur in a number of conditions, including schizophrenia in which it is often associated with fatuous mood; dissociative disorder, previously designated hysterical pseudodementia (before making such a diagnosis, the wise psychiatrist thoroughly excludes an organic cause); Ganser's syndrome; and other organic conditions.

Eccentric and pedantic use of words may sometimes be seen in those with anankastic personality; obsessionality obtrudes into the choice of words and construction of sentences.

Statistical Model of Language

The Cloze procedure involves deleting words from the transcripts of speech and assessing whether the omitted word can be predicted. Maher considered that, in schizophrenia, the greater the severity of the illness, the greater is the degree of unpredictability of the utterance of language. In normal speech, a large part of every sentence could be omitted without losing the meaning. For example, if the words ‘a … part … could be … the’ were omitted from the last sentence, the meaning would still be obvious; if letters were omitted from words, for instance nrml spech, the meaning is still clear. Predictability is the ability to predict the missing words accurately; in this sense, schizophrenics are unpredictable in their speech. They are likely to use unexpected words and phrases. In the perception of language, the schizophrenic patient is less able to gain information from the redundancies, both semantic and syntactic, in everyday speech.

A sophistication of the Cloze procedure has been investigated by Newby (1998). This involves the following.

▪ The modified Cloze procedure, in which the nature of the inserted word is noted, such as its part of speech.

▪ In the reverse Cloze procedure, thought-disordered patients were asked to make sense of a script that had been mutilated by instituting the Cloze procedure, for example by deleting every fourth or fifth word. Patients with schizophrenia performed significantly worse than a control group of orthopaedic patients, with manic-depressive patients intermediate on both modified and reverse Cloze procedures.

Schizophrenic speech is considered less predictable than normal speech, and lack of predictability is more marked with clinically manifest thought disorder (Manschreck et al., 1979). An experiment was carried out using the Cloze procedure, in which raters were asked to assess passages of schizophrenic or normal speech with the fourth or fifth word deleted. With fifth word deletion, thought-disordered schizophrenic speech was significantly less predictable than normal or non-thought-disordered schizophrenic speech; this latter was no less predictable than normal speech.

Whether schizophrenic speech is really less redundant than normal has been questioned by Rutter (1979), who was able to demonstrate no difference. The view that schizophrenic language can be reduced to such simple mathematical rules has been rejected by Mandelbrot (1965). But studies using this technique continue, even if sporadically, and demonstrate that the speech and language of patients with psychosis may be less predictable than that of controls (Adewuya and Adewuya, 2006).

The type : token ratio is a measure of the number of different words as compared with the total number of words (Zipf, 1935). Maher concluded that the type:token ratio of schizophrenics was lower than for normal subjects. The tendency of schizophrenic patients to repeat certain words and use them in an idiosyncratic way is referred to as the use of stock words.

Linguistic Approaches to Schizophrenia

Various linguistic theories have been applied to schizophrenia (for a full discussion see McKenna and Oh, 2005). These methods of analysis of schizophrenic language are tentative and do not yet cover the range of abnormalities occurring in the condition. Chomsky (1959) proposed that humans are able to use strings and combinations of words they have never heard before through use of a limited set of integrative processes and generalized patterns. However, Moore and Carling (1982) have labelled Chomskyan linguistics a container view of language, separated from the real way users of language apply it to their own meanings and contexts. Individual case studies have used tape-recorded interviews with patients with schizophrenia to demonstrate distinctive abnormalities. However, on closer analysis such abnormalities are often found to occur in the speech of normal people, although less frequently. A further study of bilingual patients showed psychotic symptoms to be present in their native language but absent in their second language. The problem of individual studies is, of course, the extent to which they can be generalized to all patients with schizophrenia.

Syntactical Analysis

In studies of speech analyzed for syntax, compared with manic and normal controls, patients with schizophrenia showed less complex speech, fewer well-formed sentences, more semantic and syntactic errors and less fluency. There were also marked use of paraphrasias, agrammatisms, anomia, pronoun word problems, circumlocutions, etc. These problems seemed to be associated with a general intellectual impairment (McKenna and Oh, 2005). Such studies do not, of course, justify the conclusion that differences are due directly to the disease or to thought disorder, nor does it take into account the social context or emotional aspects. However, marked differences are of interest when one considers that the majority of patients with schizophrenia do not show overt disorder of language.

Propositional Analysis

This is a form of textual analysis in which the text is broken down into its component propositions, and these are then represented diagrammatically to show the ‘mental geometry’ (Hoffman et al., 1982). Normal speech is considered to proceed as in a single tree diagram with all branches leading from a single key proposition, but psychotic speech more often breaks the ‘rules’ of propositional relationships.

Observers, listening to the speech of schizophrenic patients, are often struck with its oddity and deviance. It has been considered by Chaika (1995) that this is not purely a deficit of syntax but more a phenomenon like severe and repeated slips of the tongue, in which the error is a lapse of executive control, a lapse of volition. It has been shown by Morice (1995) that with increasing complexity of syntax there is an increase in the number of errors in the speech of schizophrenic patients; speakers expressing very simple sentences made relatively few errors. One of his patients expressed this: ‘and communicating ordinarily I can get lost in the chaos of the language’.

This finding was confirmed by Thomas and Leudar (1995) using the Hunt test, a written test in which subjects produce syntactically complex sentences from simple input phrases. Communication-disordered schizophrenic patients made more errors than non-communication-disordered schizophrenic patients or normal controls, and these errors were more likely to occur with more complex syntactic structures. The patients were therefore thought to have a discrete failure of language processing that was distinct from the more general cognitive disorders of the condition.

Although these methods are still experimental, the patient's use of language and syntax does enable a quantitative method of evaluating the mental state and subjective experience to be developed. Study of language disorder should be an area in which descriptive psychopathology can contribute to psychiatric research.