Chapter 1 The nursing role

In this chapter, the content is organized to address two broad areas of nursing performance related to laboratory tests and diagnostic procedures. The first area pertains to the testing procedures and the nursing role in the process of testing in an accurate and timely manner. The second area concerns the nursing interactions with the patient who must undergo a diagnostic test or procedure. The nursing process is used to organize patient care and meet the patient’s needs.

In some instances, diagnostic work is an interdisciplinary function that involves coordination and communication among the nurse, several physicians, and technicians of the laboratory, radiology department, or diagnostic specialty units. The nurse’s role is often pivotal in the transmission of information to and from the testing center. Particularly for diagnostic procedures, pertinent needs or problems of the patient are explained to the testing center personnel, such as limited mobility, weakness, or mental status of the patient. The nurse also explains the pretest laboratory or diagnostic requirements to the patient, such as dietary restrictions and other specific pretest preparations. The goal for all participants is to accomplish the diagnostic work accurately, safely, and in a timely manner.

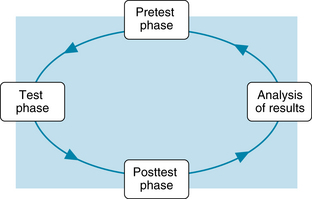

The process of laboratory or diagnostic testing can be conceptualized as a cycle that has four phases of operation: (1) the pretest phase, (2) the test phase, (3) the posttest phase, and (4) analysis of the results (Figure 1). Appropriate nursing roles and responsibilities for the test or procedure are pertinent in each phase.

Figure 1. The cycle of laboratory testing. Both the nurse and the patient are involved in each phase of the cycle. After analysis of the test results, the cycle may be restarted for additional testing as needed.

Procedural role and nursing responsibilities

Pretest phase

Scheduling of a diagnostic test

This involves communication among the individual who prescribes the test, the patient, and the individual who performs the test. When diagnostic testing involves different departments, the nurse or unit coordinator may be involved with coordination of the scheduling of the tests so that the work is done in a timely way.

When multiple tests in various departments are prescribed, it is sometimes necessary to prioritize the test schedule because the method of conducting one test can interfere with the results of another. For example, x-ray studies that use contrast medium are performed before x-ray studies that use barium contrast material. Residual barium remains in the intestine for several days, and its opacity would obscure the view of the other tissues, such as the biliary tract and abdominal vasculature. Likewise, blood tests that use a radioimmunoassay method of analysis must be performed before or 7 days after a nuclear scan because the radioisotopes of the scan would interfere with the radioimmunoassay method of analysis of the blood and alter the test results. When these interfering factors involve tests performed by a single department, such as the laboratory, the priorities are routinely sorted out by the laboratory personnel.

Some priorities in scheduling are determined by the acuity of the patient. Particular test results may be needed rapidly for the assessment of the patient’s status, for correct medical diagnosis and treatment, or for evaluation of the patient’s response to treatment. Blood tests may be prescribed serially, for example, every hour for 4 hours; daily; or immediately (Stat). The nurse monitors to ensure that the tests are completed, as requested. The results are reported to the physician, as needed, and are posted manually or electronically in the patient’s record. When a test is needed urgently, the laboratory or diagnostic unit is notified, the scheduling arrangements are confirmed, and the test or procedure is completed immediately.

Some tests can be performed at the bedside with immediate results provided by point-of-care testing. Other tests, such as a culture, require time to obtain results and the results may not be available for several days or more. Nonroutine or special tests must be scheduled in advance. For example, positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear scan using a radioisotope that is made by splitting atoms in a cyclotron. This special and costly radioisotope is created on the day of the test, but has a short half-life of only 7.5 hours. When the person lives at home and is scheduled to come to the nuclear medicine department for the PET scan, it is essential that the scan starts on time. Prior to the day of the test, the radiology nurse phones the patient to review pretest instructions, answer any questions, and remind the person of the appointment.

Requisition forms

The laboratory requisition form is the major way to request the needed tests for the patient. The physician or health care provider who orders the test is also responsible to complete the requisition form. This simplified method avoids potential transcription errors that can occur when someone else completes the written request (McPherson & Pincus, 2007). Usually, the requisition is sent to the laboratory electronically, but it may be written manually.

The form must contain the same patient’s identifying information that is on the patient’s identification wristband and all hospital records. The information includes the patient’s name, identification number, birth date, gender, age, social security number (if possible), and physician’s name. Additional identifying data may be included, based on the institution’s preferences.

The needed tests are selected by the physician or health care provider. Specific information may be included, such as pertinent medical history, suspected diagnosis, date of last menstrual period, or pregnancy status. This additional information is used to help with diagnosis and to establish the correct reference values based on age, gender, or other biologic variables.

Once the data of the requisition form is entered into the laboratory information system, an individual bar code is created. This bar code is automatically printed on the labels for the collected specimens, along with the identifying patient information. The bar code is used to identify the specimen as it moves through laboratory analysis and also is a tracking device that ensures that all specimens are identified, analyzed, and the results are entered in the patient’s record.

Test phase

The procedural responsibilities of the nurse vary considerably with different tests, and they vary somewhat among different institutions or units within the institution. When the specimen collection is performed by the physician or other health care provider, the nurse may have only indirect responsibility for ensuring that the test is performed, the specimen is labeled properly, and sent to the laboratory. Laboratory technicians, phlebotomists, or radiology technicians are supervised by personnel in their respective departments. The nurse has no official role in their work, unless patient safety becomes an issue.

If the hospitalized patient must go to the radiology department or to a special diagnostic unit, the nurse ensures that patient care is completed and that the patient is prepared for transport to the unit. Equipment, such as an intravenous line or a urine drainage system, must be functional and secured properly.

In some cases, the nurse is directly involved in the collection of specimens. This may include the collection of blood, urine, stool, and culture specimens, as well as assisting with the collection of a sample of tissue or body fluids. In these processes, the nurse shares in the responsibility for maintenance of quality controls, proper performance of the equipment, accurate identification of the patient, and correct labeling of the specimen. Along with the patient identification data and bar code on the label, the nurse includes the date and time of the collection procedure and identification of the tissue or fluid that was obtained.

Identification procedures

It is essential to perform a correct identification before collecting the specimen or starting a diagnostic procedure, such as bone marrow or other biopsy, culture, or any other specimen. The Joint Commission (2010) requires that the person who collects the specimen must obtain the patient’s identification from two different sources. One source is the name on the patient’s wristband and it is the same name as that on the requisition. The second source is that the patient states his or her full name. The patient’s room number or physical location cannot be used for identification purposes.

If the patient cannot respond, the staff nurse or a relative of the patient verifies the identity. There must be an exact match of identification among the two name identifications and the requisition information. The label also contains the same identifying information and after the specimen is obtained, the label is applied directly to the specimen container before leaving the patient.

Infection control: standard precautions

Standard precautions must be used when obtaining or handling a blood or body fluid specimen. Gloves must be worn during the collection procedure. If splashing or contact with a mucous membrane is anticipated, the nurse wears a mask, protective eyewear, and a gown or protective clothing in addition to the gloves.

All specimens of blood or body fluids are placed in the correct containers with tightly fitted lids to prevent leakage during transport of the specimen to the laboratory. After the completion of the procedure, the gloves and disposable clothing are removed and discarded. Hands are washed with soap and water.

Precautions are taken to prevent the puncture or cutting of one’s own skin with a contaminated needle, scalpel blade, or sharp instrument. To prevent needlestick injury, the needle-and-syringe unit is disposed of in a puncture-resistant container. The needle is not recapped, broken, bent, or removed from the syringe because of the risk of accidentally puncturing the hand.

Special reusable needles, such as those for a spinal tap or aspiration of a joint, are placed in puncture-resistant containers for transport to the area where they are cleansed and sterilized. Reusable instruments and diagnostic equipment are also cleansed and sterilized or disinfected according to established protocol.

The use of standard precautions is based on the premise that all patients are potentially infectious and that there is a risk of transmission of infection after exposure to blood or other body fluids. The precautions are used to protect all health care workers against blood-borne pathogens, including HIV.

Point-of-care testing

Point-of-care (POC) testing refers to methods of testing and analysis that bring the laboratory services nearer to the patient. This type of testing also is known as bedside testing, near-patient testing, or a rapid test. Satellite laboratories may be established near operating rooms, intensive care units, and emergency departments. Desktop analyzers may be used in these sites as well and in a clinic, an ambulatory care setting, a physician’s office, and long-term care facility. There is rapid turn-around time between obtaining the specimen and receiving the test results. Medical diagnosis and treatment is based on real-time values and will be more accurate, avoiding a long delay before the central laboratory results could be available. There has been a dramatic expansion of these rapid tests during the past decade and this trend is likely to continue in the future (Lewandrowski, 2009a; Nichols, 2007). A partial list of the point-of-care tests is presented in Box 1.

Box 1 Partial List of Tests Available With Point-of-Care Testing

From Lewandrowski, K. (2009). Point of care testing: An overview and a look to the future (circa 2009, United States). Clinics in Laboratory Medicine, 29(3), 427.

When electronic charting is used, the laboratory results are transferred electronically from the point-of-care analyzer to a central computer system and entered automatically in the patient’s record. If manual entry is used, the nurse must ensure that all the test results are charted in the correct order and time sequence.

With point-of-care methodology, reference values are different from the values of the same tests analyzed in the central laboratory. Different reagents, test equipment, and method of analysis create the differences in the reference values. The nurse refers to the point-of-care reference values provided by the central laboratory or the manufacturer of the point-of-care equipment for correct interpretation of the data.

Another category of point-of-care testing refers to the testing that is performed with small handheld instruments that analyze the patient’s blood in a few minutes. The specimen is obtained and the blood analyzed wherever the patient is located, including the home or the workplace. The patient is usually the person who performs the test as part of self-care responsibilities. Blood testing monitors are used for timely measurement of glucose levels in diabetics and more recently for monitoring the prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (INR) in those who are maintained on anticoagulant medication.

Expanded nursing role

Point-of-care testing involves an expanded role for nurses that overlaps with that of laboratory technicians. The nurse may collect the blood sample, perform the analysis, and produce the test results. When the patient monitors his or her own glucose levels or prothrombin-INR levels, patient teaching is an essential component of nursing care. The teaching begins in the hospital and continues by appointment in the specific clinic or office, until the patient can use the monitor, recalibrate the equipment accurately, interpret the results, and based on the results, adjust the medication according to the physician’s guidelines. Repetition of the teaching-learning activities continue until the patient can perform these functions with consistent accuracy.

The laboratory is responsible for point-of-care testing, policies, procedures, and maintenance of the equipment. Nurses, as the providers of direct patient care, may use the automated analyzers. Alternatively, multitasked nursing assistants may perform the point-of-care testing. As part of laboratory accreditation requirements, the person who uses this equipment must have formal training for each test, certification that the training has been completed satisfactorily, and an annual reevaluation of performance (Ehrmeyer & Laessig, 2009). Without the training there is a high incidence of inconsistent performance and inaccurate test results.

Posttest phase

Transport of the specimen

The specimen is generally transported to the laboratory as quickly as possible. Some laboratory or pathology specimens become unstable shortly after they are collected. Specific factors, such as exposure to sunlight, warming, refrigeration, and exposure to air, can cause alteration or deterioration of particular specimens. For many blood tests, the unprocessed specimen will begin to deteriorate within a few hours. The phlebotomist and laboratory technician have responsibility for their own specimens. When needed, messengers may be used to deliver other specimens promptly, as from the operating room, emergency department, or patient care units.

When a fresh tissue sample must be analyzed for cytologic features, the specimen cannot be placed in fixative or preservative. Because the specimen will dry out after some exposure to the air, it may be delivered directly into the hands of the pathologist as soon as it is obtained. This coordination of activity provides immediate transport and tissue preparation so that the quality of the specimen is maintained.

Rejection criteria

When an unsatisfactory specimen is delivered to the laboratory, rejection criteria are applied. The causes of rejection are presented in Box 2. When the specimen is rejected, the test must be repeated. The nurse or staff member who performs the specimen collection can help ensure acceptance of the specimen by collecting a sufficient quantity, by complying with the written protocol of the test, and by labeling the specimen container accurately.

Analysis of the results

Reference values

The outdated term, once called “normal values,” is now more correctly called reference values. The values are usually in a range from the lower to the upper limits of normal. The reference values are used to interpret the results of the test, assist in making an accurate diagnosis, and to evaluate the patient’s response to treatment.

The reference values for a specific test will vary with the different methods of chemical laboratory analysis and with different sources of specimen. For example, the reference value of chloride in a specimen of blood or plasma is different from the reference value of chloride in a sample of cerebrospinal fluid. The reference values usually vary with age of the patient, and sometimes vary with gender and race. The numeric values are different when reported in conventional reference values or international reference units. The nurse can use the reference values in this text as a general guide, but the reference values provided by the laboratory that performed the test are the most appropriate values for interpreting the findings in the clinical setting.

For some tests, the particular substance should not be present at all, such as cocaine or mercury. When it is not present, the result is described as negative. When it is present, the result is abnormal and the finding may be described as “present” or “positive,” or it may be measured with a numeric value that quantifies the amount of substance found.

SI units refers to the International System of Units (Système International d’Unites), a system that reports laboratory data in terms of standardized international measurements. This system of measurement is currently used in a number of countries, with the eventual goal of worldwide use. Throughout this text, the reference values are presented in conventional units and their SI equivalents.

False negatives and false positives

A false-negative result means that the test result is negative, but the patient actually is positive and that the problem was not detected. The possible consequences of a false negative are that the patient and physician do not investigate further, treatment is delayed, and that the patient’s symptoms continue unabated until additional tests identify the correct result and its cause.

A false-positive result means that the test result is positive, but the patient actually has no disease or problem. The possible consequences of a false positive can mean that additional tests will be done to investigate a problem that does not exist. Occasionally, treatment is started when there is no need to do so. When additional testing verifies that there is no problem, the patient is relieved, but sometimes becomes annoyed or angry because of needless worry about a nonexistent problem.

Sensitivity and specificity

In laboratory terms, sensitivity means the probability that the person having the disease will be correctly identified by a positive result. Specificity means that the person who does not have the disease will be correctly identified by a negative result. In a perfect world, the perfect test has a proven performance of 100% sensitivity and specificity. However, no laboratory test is perfect and tests have lower than 100% sensitivity and specificity percentages (Jackson, 2008). The test with lower than desired sensitivity or specificity scores will have a higher rate of error because of false-positive or false-negative findings. Physicians generally order several tests or follow-up tests to verify the findings and eliminate errors.

Critical values

The phrase “critical value” refers to a laboratory or diagnostic test result that is very abnormal and may indicate a life-threatening situation. The critical value may be a markedly elevated or decreased test result or it may identify a serious pathogen. Identification of critical values helps the nurse, physician, and nurse practitioner to differentiate between abnormal results and the extremes that indicate a possible crisis. Medical diagnosis and treatment are needed to correct the problem quickly before the patient’s acute condition worsens.

The Joint Commission (2010) requires that all hospitals have an established critical values list, with the individual hospital’s determination of which tests and diagnostic procedures demonstrate life-threatening results and the numerical values or diagnostic procedure findings that indicate the severity. Thus there is some variation among institutions as to the selection of laboratory tests, the numerical values, and diagnostic test findings that indicate a critical condition. Each hospital has its own written protocol of the laboratory’s rapid notification. The policy must identify the reporting process “by whom” and “to whom” a critical result is reported. Generally, the physician in the laboratory reports by phone to the patient’s physician. If the physician cannot be located, the nurse has the responsibility to receive the phone report from the laboratory, locate the physician as quickly as possible, and provide the needed information.

Verbal reports

When a laboratory test result is in the critical value range or when the laboratory test or diagnostic procedure was ordered on a stat basis (to be done immediately), the laboratory or diagnostic unit physician will phone the patient’s physician or the nurse to report the results immediately. With a verbal report, there is risk of error because of a potential misunderstanding of what was heard. The procedure the nurse follows is to write down the name of the test and the results and then to read back the information to the caller. The “read-back” process provides for confirmation of the accuracy of the received message or opportunity to correct a misunderstanding. The nurse must then contact the physician without delay and report the information. The physician uses the same read-back process.

Patient-nurse interactions

Dimensions of nursing care

The range of interactions between the patient and the nurse varies considerably with the complexity of the test or procedure. Laboratory tests that use specimens of blood, urine, or feces require some nursing intervention to ensure adequate patient preparation and accuracy in the collection of the specimen. Diagnostic procedures, however, require increased interaction with the patient, particularly when the procedures are invasive. Nursing responsibilities involve physical and psychosocial dimensions of patient care, with particular concern for the patient’s safety.

Patient-nurse interactions involve direct or indirect care in the pretest, test, and posttest phases of the diagnostic procedure. The nursing process is applicable as a guide to the identification of the patient’s needs and the development of the appropriate nursing interventions that lead to a positive outcome (Figure 2).

Changes in health care delivery

These changes have resulted in shorter hospital stays for patients. Shorter periods of hospitalization limit the time for direct care during the acute phase of illness. For the acutely ill hospitalized patient, numerous diagnostic tests or procedures are often scheduled during a concentrated period. In addition to the routine pretest and posttest assessments of the patient, the nurse assesses for actual or potential complications related to the invasive diagnostic procedures.

Changes in health care delivery have resulted in many diagnostic tests being performed on an outpatient basis. The patient has been given greater self-care responsibility for pretest preparation and posttest recovery. When outpatient testing occurs, the direct nursing interactions with the patient are often limited, unless the nurse works in radiology or the unit where invasive diagnostic testing is done.

When a diagnostic procedure is performed in the outpatient setting, the patient receives pretest planning information and instructions regarding special requirements necessary before and after the procedure. The clearly stated instructions are given to the patient or the family member who assists with the patient’s care. If the instructions are complex, they should be given in writing so that the patient can refer to them as needed. Also, the patient needs the address and location of the laboratory or diagnostic unit, as well as the time and date for which the test is scheduled.

In procedures requiring sedation or light anesthesia, the patient is instructed in advance that a responsible individual will be required to provide transportation home at the end of the test. When a delayed complication in the posttest period is possible, the patient receives instruction so that he or she will recognize abnormal symptoms and notify the physician if they occur. All these measures are designed to provide continuity of care, even when the patient is some distance from the health care provider.

Pediatric patients

Modifications in communication and safety measures are required for pediatric patients. These measures should be compatible with the age and behavior of the child. When explanations can be understood, time should be taken to prepare the young child for the test or procedure. Honest, friendly explanations help the child cope with the test. The child may fear pain, injections, the large equipment of the radiology department, or even the strangers who perform the test. Explanations are given simply and briefly. In some cases, the parents help prepare the child and provide calming reassurance.

Infants or active small children usually require restraints to protect them from harm and to maintain immobility during the test or procedure. The choice of restraint is based on the particular need and is used for tests of short duration. The choices include a sheet restraint, a mummy-style restraint, or a commercial restraint that holds the patient in a particular position.

When the procedure requires a prolonged period of immobility, sedation is often used for infants and small children. Because of their young age, children cannot be expected to remain still for a long time. The procedures that use sedation in children include nuclear medicine scans, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography, echocardiography, and some ultrasound procedures.

Geriatric patients

Older adult individuals may have certain needs that are age related or caused by a specific disease process. For the confused or depressed patient, instructions may need to be given slowly or repeated several times. The patient may have a hearing deficit or difficulty understanding speech or language. When indicated, alternative communication measures may include written pretest and posttest instructions, inclusion of a family member in the communications, or providing an interpreter to help the patient.

The elderly patient may take a wide range of medications, and some of them can interfere with particular laboratory tests. The physician is consulted regarding any alteration in the medication schedule, such as withholding the medication for a specified period.

Frail, elderly patients are at risk for injury from a fall. The common underlying problems include visual impairment, stiffness, weakness, mental confusion, dizziness, and the effects of medication. Care is taken to prevent accidental injury or a fall by assisting the patient out of the wheelchair and onto or off a gurney, examining table, radiography table, or toilet.

The elderly individual is often uncomfortable when lying on an x-ray table for a long time. The table is hard and the patient’s joints are often stiff with arthritis. The room is usually cool, and some older patients complain that they feel cold. It may not be possible to change the patient’s position during x-ray studies or other diagnostic procedures because of the requirements of the test; however, warm blankets are usually provided so that at least the discomfort of chilling is removed.

Pretest phase

Nursing assessment

This assessment consists of the appraisal of the patient’s physical and psychosocial status in relation to the requirements of the test. Pertinent findings in the psychosocial and physical history include any problems with the patient’s vision, hearing, mobility, and comprehension of instructions. Current medications are listed. When contrast medium is used in a radiologic study, the nurse assesses for any history of a sensitivity reaction, particularly a reaction to contrast medium during a previous radiology test. Allergies to foods and medications are also documented. If a female of childbearing age needs an x-ray study, she is questioned to determine whether there is any possibility of pregnancy. A rapid urinary pregnancy test may be done for verification before the radiologic procedure is done.

Vital signs are taken to establish baseline values, particularly for an invasive procedure or when contrast medium, sedation, or anesthesia is used. The infant’s or child’s weight is recorded when the dose of medication or contrast medium must be calculated according to body weight. In radiology imaging, contrast medium is often used. Because contrast medium is excreted in the urine, pretest, rapid urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine testing is often done, using point-of-care technology. Normal results ensure that renal function is normal and the healthy kidneys will be able to eliminate the contrast.

The nurse assesses the patient for signs of anxiety or fear. The cause can be apprehension about the test or procedure or fear of abnormal test results. If signs of distress are noted, the nurse asks the patient about the cause or source of the anxiety and provides reassurance, as appropriate.

The nurse also reviews the laboratory and other diagnostic test results and ensures that they are in the patient’s record. Tests, such as prothrombin time, complete blood cell count, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, BUN, and creatinine verify a health clearance before some of the more invasive diagnostic tests are undertaken.

Nursing diagnoses

Once the nursing assessment is completed, the nurse formulates nursing diagnoses that are appropriate to the patient who will undergo a procedure. The pretest-phase nursing diagnoses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Pretest-Phase Nursing Diagnoses

| Nursing Diagnosis | Defining Characteristics |

| Risk for injury | Presence of risk factors such as developmental age, psychological factors, or physical factors such as sensory or motor deficit |

| Risk for infection or allergic reaction | Presence of risk factors, such as altered immune function, history of chronic illness, impaired oxygenation of tissues; external factors, such as allergens or infectious agents |

| Protection, ineffective | Presence of risk factors, such as altered clotting factors, immunosuppression, myelosuppression, altered cardiovascular or renal status, or disorientation |

| Impaired verbal communication | Unable to speak dominant language, speaks with difficulty, difficulty in comprehension, altered mental status |

| Anxiety | Presence of increased tension, uncertainty, fear of unspecific consequences, cardiovascular excitation, facial tension, insomnia, confusion |

Nursing Diagnoses - Definitions and Classification 2009-2011. Copyright © 2009, 2007, 2005, 2003, 2001, 1998, 1996, 1994 by NANDA International. Used by arrangement with Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, a company of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Expected outcomes

During the pretest period, the expected outcomes include the following:

Nursing intervention

The nurse notifies the physician of abnormal pretest results that indicate infection, clotting abnormality, abnormal renal function, fever, or irregularity in the vital signs. The diagnostic procedure may have to be postponed until the abnormality is corrected.

If the patient has allergies to food, medication, or contrast medium, the nurse posts an allergy warning in the patient’s record. Other various types of allergy warning are determined by hospital policy, such as use of an allergy wristband.

Before the day of the test, the nurse provides or implements pretest instructions that can be understood by the patient. Pretest instructions often include the discontinuation of food and fluids for a specified period. They may also involve modification of activity or the temporary stoppage of one or more medications for a specified period. Some abdominal or intestinal tests require a cleansing of the bowel by enema or cathartic, or both.

When indicated, the nurse witnesses the patient’s signature of consent for the test or procedure. The patient should have received the physician’s explanation of the procedure, the method of performing the test, and the potential risks involved. If the patient cannot give consent because of age or physical or mental impairment, the nurse obtains the signature of the person who is legally responsible for the patient’s health care decisions. Once the consent form is signed and witnessed, the nurse enters it into the patient’s record.

The nurse provides reassurance or information, as needed, to help reduce the patient’s anxiety. This is best done by communication with and assistance to the patient in an attentive and caring manner.

Test phase

Nursing assessment

The nursing assessment during the test phase begins with the correct identification of the patient and the verification of the procedure and the area to be tested (such as right or left leg, arm, breast, or lung).

Monitoring of the physiologic status of the patient is carried out by a variety of measurements, depending on the complexity of the procedure and the use of conscious sedation or light anesthesia. Ongoing assessment of the patient may be performed through observation of the level of consciousness, repeated monitoring of vital signs, pulse oximetry, cardiac monitoring, or, in pregnant patients, fetal monitoring.

The skin is assessed for signs of infection or trauma, particularly at the site of intended venipuncture. The patient’s chart is also reviewed for the most recent laboratory findings and the pretest vital signs.

The nurse observes the patient for signs of discomfort, including shivering, trembling, pain, and tension. To encourage communication of any problems or concerns, the patient is asked how he or she feels.

Nursing diagnoses

Once the nursing assessment is completed, the nurse formulates nursing diagnoses that are appropriate to the patient who undergoes the procedure. The test-phase nursing diagnoses are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Test-Phase Nursing Diagnoses

| Nursing Diagnosis | Defining Characteristics |

| Risk for impaired skin integrity | Disruption of the skin surface |

| Presence of internal or external risk factors, including skin compression, immobility, or altered circulation | |

| Decreased cardiac output | Variations in blood pressure readings, arrhythmias, color changes of the skin, decreased peripheral pulses, dyspnea, increased heart rate |

| Impaired gas exchange | Cyanosis, restlessness, dyspnea, hypoxemia |

| Risk factors: administration of sedative analgesic medications, contrast medium, and potential sensitivity reaction | |

| Risk for infection | Presence of risk factors such as inadequate primary defenses and performance of invasive procedures |

| Pain | Verbal report or expressive behavior, such as moaning, crying |

| Observed evidence, such as guarding behavior or grimacing | |

| Anxiety | Verbalization of feelings about the test or its potential findings, changes in cardiovascular and respiratory rates |

Nursing Diagnoses-Definitions and Classification 2009-2011. Copyright © 2009, 2007, 2005, 2003, 2001, 1998, 1996, 1994 by NANDA International. Used by arrangement with Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, a company of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Expected outcomes

During the test period, the patient’s outcomes include the following:

Nursing intervention

The nurse positions the patient correctly for the procedure. Use padding, supportive devices, or restraints to promote safety and protect the patient’s tissue against injury.

The patient’s cardiopulmonary status is monitored continuously, including assessment of skin color and integrity, vital signs, breathing status, and level of consciousness.

The nurse keeps the emergency cart in a nearby location.

The nurse ensures that all invasive equipment is sterile or has been properly cleaned and disinfected. Before the skin is punctured or opened, ensure that the skin is appropriately cleansed. Draping the area with sterile towels may also be indicated.

Verbal or physical support is offered to the patient by the nurse, particularly when the patient appears distressed by the procedure.

The nurse administers prescribed pain medication as indicated.

Posttest phase

Nursing assessment

The assessment after the test is completed is focused on the patient’s physiologic, emotional, and mental status. Physiologic assessment is essential after an invasive procedure, conscious sedation, or anesthesia. The nurse assesses the expected alterations that occur because of the procedure or medications and the potential complications that may occur.

When cardiac monitoring, fetal monitoring, and pulse oximetry are used during procedures, they are usually continued into the posttest period until the results are stable and remain in a normal range. Alternatively, vital signs are taken manually to ensure that the hemodynamic status remains stable.

A risk of complications from a sensitivity response to the contrast medium in radiology imaging exists. Vital signs also are monitored frequently to identify any untoward changes in cardiorespiratory status. In addition, a risk of an embolus exists when invasive neurologic, cerebrovascular, or peripheral arterial imaging is performed. Neurovascular assessments are performed to assess the integrity of the distal arterial blood flow and the responses of the neurologic tissues that are supplied by that blood flow. The nurse also uses observation to perform many assessments. When the diagnostic procedure is invasive, the nurse examines the site of the incision, penetration of the needle, or insertion of the instrument. The dressing should be clean, dry, and intact. The tissue is examined for signs of swelling, discharge, bleeding, or discoloration. Some pain or soreness may be present because of the incision or the manipulation of internal tissue. The nurse asks the patient to describe and locate the pain or tenderness.

The assessment of mental status is appropriate when the patient has received conscious sedation or anesthesia or after a cerebrovascular invasive test. The nurse assesses the level of consciousness as well as clarity of thinking and speech. During the initial recovery from conscious sedation or anesthesia, the patient may be somewhat confused or drowsy, with diminished affect. As the medications are metabolized and excreted, increasing responsiveness and clarity of thinking are noted.

Before discharge, the patient who has had an invasive procedure is assessed for knowledge about continued requirements for care at home until healing is complete. The patient may be able to perform self-care, or there may be a need for family assistance for the remainder of the day. Assessment for infection or inflammation continues for several days, because the symptoms take time to develop. The patient or family member is taught to continue this assessment at home.

Nursing diagnoses

Once the nursing assessment has been completed, the nurse formulates nursing diagnoses that are appropriate to the patient during the posttest phase of care. The posttest-phase nursing diagnoses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Posttest-Phase Nursing Diagnoses

| Nursing Diagnosis | Defining Characteristics |

| Altered tissue perfusion: cerebral, cardiopulmonary, peripheral | Changes in skin temperature, blood pressure changes, arrhythmias, dyspnea, decreased peripheral pulses, altered mental status |

| Pain | Verbal report about pain or discomfort |

| Alteration in muscle tone, movement, or facial expression | |

| Expressive behavior, such as moaning, grimacing, and crying | |

| Risk for injury | Presence of risk factors such as immobility, developmental age, or sensory-motor deficit |

| Risk for infection | Presence of risk factors such as exposure to pathogens, immunosuppression, or broken skin |

| Knowledge deficit regarding care after procedure | Verbalization of the problem, inaccurate follow-through on instructions |

| Anxiety | Expressed concerns or uncertainty about the findings of the test or procedure, sleep disturbance, increased tension, worry |

Nursing Diagnoses-Definitions and Classification 2009-2011. Copyright © 2009, 2007, 2005, 2003, 2001, 1998, 1996, 1994 by NANDA International. Used by arrangement with Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, a company of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Nursing intervention

After the completion of a diagnostic procedure in which conscious sedation or a light anesthesia was used, position the patient on his or her side to maintain a patent airway.

Oxygen may be administered, and the intravenous fluid replacement continues until the patient is able to drink fluids.

Administer the prescribed pain medication as needed. To help relieve discomfort, encourage the patient to change positions. Provide support with pillows.

Maintain sterile technique in the assessment of the wound or in changing the dressing.

Inform the patient that the physician will discuss the diagnostic results as soon as the information is available. The patient with sutures is instructed to make an appointment with the physician for the evaluation of the incision and removal of the sutures.

Before discharge, instruct the patient about any recommended restrictions, such as instructions regarding activity, bathing, resumption of medication, the intake of fluids, or care of the incision.

Nursing evaluation

The posttest phase is completed when the following have been accomplished.

Analysis of the results and the significance in nursing practice

The nurse who cares for the patient reads the laboratory results and reports of the diagnostic procedures that provide additional objective assessment information. The information helps confirm the patient’s medical diagnosis and severity of the pathophysiologic changes. When repeat testing is done, the results are compared with previous results to monitor the patient’s response to treatment.

In the diagnostic workup, the physician or health care provider uses the tests to confirm the medical diagnosis and estimate the severity of the condition. Often several tests are needed to identify the specific illness and exclude other possible conditions. Also, many illnesses cause alterations of more than one organ or body system. When repeat tests are used to monitor the patient’s response to treatment, the nurse monitors the changes that indicate an improving condition.

The nurse also can use his or her knowledge of the significance of test findings to help patients. The patient may be apprehensive about the possibility of abnormal findings or in need of counseling, clarification, or reassurance regarding abnormal test results that are now known. The nurse can help the patient with emotional support by listening and providing calm and caring responses. The nurse also can try to determine what the patient understands about the meaning of the test results. Finally, the nurse also provides hope by encouraging the patient to consider treatment options and plan for follow-up care.