Influences of the Mind and Body

After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following:

2 Identify qualified sport psychologists.

3 Explain how massage supports the sport psychologist.

4 List ways in which massage supports the zone experiences—mental toughness, ideal performance state, and peak performance.

5 Explain the importance of sport psychology during injury rehabilitation.

6 Identify the signs of mental and emotional strain requiring referral to the medical team or sport psychologist.

7 List the five stages of response to injury.

8 Define stress and explain stress coping strategies.

Sport psychology is the study of psychological and mental factors that influence, and are influenced by, participation and performance in sport, exercise, and physical activity, and application of knowledge gained through this study to everyday settings.

Sport psychology professionals are interested in how participation in sport, exercise, and physical activity may enhance personal development and well-being throughout the life span.

Sport psychology involves several different components: mental training, performance enhancement, social interactions, learning, motivation, leadership, anxiety and stress management, cognitive rehearsal techniques (including hypnosis), intentional control training, injury treatment, cognitive intervention strategies, aggression management, and cohesion/congruency.

Sport psychology professionals may be trained primarily in the sport sciences, with additional training in counseling or clinical psychology, or they may be trained primarily in psychology, with supplemental training in the sport sciences.

The activities of a particular sport psychology professional will vary based on the practitioner’s specific interests and training. Some may primarily conduct research and educate others about sport psychology. These individuals teach at colleges and universities and, in some cases, also work with athletes, coaches, or athletic administrators. They provide education and develop and implement programs designed to maximize the overall well-being of sport, exercise, and physical activity participants.

Other professionals may focus primarily on applying sport psychology knowledge. These individuals are more interested in enhancement of sport, exercise, and physical activity performance or enjoyment. They may consult with a broader range of clients and may serve in an educational or counseling role.

Only those individuals with specialized training and, with certain limited exceptions, only those with appropriate certification and/or licensure may call themselves sport psychologists. A sport psychologist should be a member of a professional organization such as the Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology (AAASP) and/or the American Psychological Association (APA). A growing number of sport psychology professionals are certified by the AAASP. These professionals—who earn the designation Certified Consultant, AAASP (or CC, AAASP)—have met a minimum standard of education and training in the sport sciences and in psychology. They have also undergone an extensive review process. The AAASP certification process encourages sport psychology professionals who complete it to maintain high standards of professional conduct.

Some sport psychology professionals may be listed on the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) Sport Psychology Registry, meaning that they are approved to work with Olympic athletes and national teams. To be on the Registry, a professional must be a CC, AAASP and a member of the APA.

Why Sport Psychology?

During the past two decades, sport psychology has received significant and increasing attention from athletes, coaches, parents, and the media. A growing number of elite, amateur, and professional athletes acknowledge working with sport psychology professionals.

Exercise specialists, athletic trainers, youth sport directors, corporations, and psychologists are using knowledge and techniques developed by sport psychology professionals to assist with improving exercise compliance, conducting rehabilitation programs, educating coaches, building self-esteem, teaching group dynamics, and increasing performance effectiveness.

Almost all sports are based on competition. Striving to reach peak performance is appropriate until athletes push themselves beyond their capacity. Exercise is very helpful in alleviating stress, releasing tensions, and producing a relaxing kind of fatigue. However, some people go far beyond this normal response and become overly dependent on daily exercise.

One of the by-products of exercise is the production of naturally occurring brain chemicals that influence mood. Endorphins are morphine-like substances that produce a sense of well-being and relaxation and are responsible for the “runner’s high.” Some people become addicted to daily exercise through production of these chemicals. If they don’t exercise, they become depressed and irritable, and they may actually have withdrawal symptoms. If they become injured, they will make life miserable for everyone around them until they can get back to exercising daily. Many athletes refuse to take time off because of their drive to keep pushing themselves. It can be difficult to get the message across that an injury, like a hamstring pull, may take 3 or more months to heal. This mental outlook often interferes with even the best treatment because the athlete will try to play before he or she is ready.

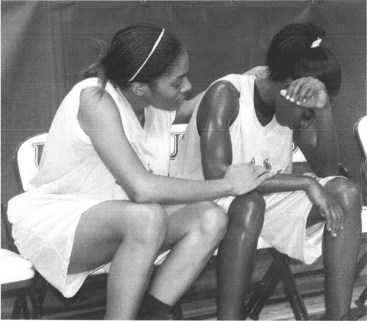

Muscles may be held in sustained tension owing to overuse, poor posture, and/or psychological or emotional stress. States of anxiety and anger, for example, can create sustained muscular hypertonicity. Emotional stress, such as depression, can also cause decreased muscular tone and loss of sensory motor communication (Figure 8-1).

FIGURE 8-1 Sport performance is a roller coaster of physical and emotional ups and downs. (From Cuppett M, Walsh K: General medical conditions in the athlete, St Louis, 2012, Mosby.)

Appropriate massage can support the work of the sport psychologist by calming anxiety, reducing increased motor tone of muscles, and, to a lesser extent, addressing mild depression. Massage affects the same mood-altering neurochemicals as exercise.

What is the Zone?

4. List ways in which massage supports the zone experiences—mental toughness, ideal performance state, and peak performance.

Studies of athletes, artists, and others have shown that being “in the zone” generally means being in a state in which mind and body are working in harmony. When in the zone, an individual is calm yet energized, challenged yet confident, focused yet instinctive. Different parts of the brain are working together smoothly to automate the movement or skill. This is comparable with the massage practitioner’s being “centered.”

Training the mind is an important step toward getting in the zone. Aspects of mental training for some sports and positions include increasing concentration and focus, controlling emotions, feeling relaxed but energized, being calm and positive, and aiming to feel challenged and confident. A person who is in the zone is free of worries and is confident and relaxed, so that the best performance occurs automatically.

Getting in the zone combines physical and mental training. When the body is conditioned, skills are well practiced, or habituated, and mental conditioning is congruent; a zone experience is then possible.

The implications for massage supporting “zone” functions are vast. Physical sensations of relaxation can help relieve anxiety and tension and improve concentration and focus. Various progressive relaxation methods that involve contracting and releasing the tension in large muscles are used. Massage can induce deep relaxation and support zone functions.

Guided imagery can help reduce anxiety and increase concentration and confidence, and can serve as mental practice or rehearsal. Imagery techniques work well in conjunction with relaxation techniques such as massage because relaxation can help the client better imagine performing the skill required. During massage or other induced relaxation states, the athlete can mentally picture himself or herself performing a specific sport or activity. He or she can visualize being dressed, getting ready to perform, hearing the sounds and smells—feeling the muscles and emotions and envisioning doing the activity, practicing skills, running the race—whatever it might be.

Negative thoughts can get in the way of concentration and confidence. The massage therapist must not be negative during the massage and must support positive and productive thought processes.

Although training the mind and body can lead to more skillful and enjoyable play, it is important to understand that the athlete might not get in the zone all the time. The zone experience does not happen nearly as often as people like to think it does. Do not overfocus on the zone experience during the massage.

Several names may be used for states of being similar to the zone. Each is slightly different, but the basic concepts are the same.

Mental toughness is the ability to perform near the athlete’s best no matter what the competitive circumstance—to maintain calmness of thought, thinking positively, being realistic, and remaining focused.

Ideal performance state is the level of physical and mental excitement that is ideal for performing at the top. Key elements include being confident, relaxed yet energized, positive, challenged, focused, and automatic.

Peak performance describes one’s very best performance, although a person need not necessarily be in the zone while achieving it. Key elements include being focused, relaxed, confident, and energized.

Injury and Sport Psychology

5. Explain the importance of sport psychology during injury rehabilitation.

6. Identify the signs of mental and emotional strain requiring referral to the medical team or sport psychologist.

Whether the athlete is a competitive or a recreational exerciser, recovering from an injury can present a challenge. How the athlete understands and responds to pain and limitation is a very individual experience based on many factors. However, certain responses and psychological skills can help most people take an active role in their own recovery.

People often initially feel overwhelmed by an injury. The ability to cope will greatly improve if the athlete works closely with the doctor and other health care providers to develop a clear plan for recovery.

Successful rehabilitation begins with becoming informed about the injury. It’s important to know the extent of the injury and anticipated recovery time, and to understand the rehabilitation plan required to recover safely and effectively.

It is important that the injured person considers himself or herself as an active participant in rehabilitation planning and treatment. An individual may not understand the scientific aspects of recovery, but he or she is the expert on his or her own experience—a reality that may help or hinder rehabilitation.

How the athlete responds to the injury is also very important. Although certain sports or activities present greater risk for injury than others, an injury usually is not expected or planned for. Athletes are rarely prepared for the emotional response to an injury.

Injuries have very different meaning for different people. For some, an injury might be life-threatening or career-ending. For others, an injury might take them away from a team or social structure that gives them a sense of identity and community. An injury can also interfere with a job or responsibilities at home. It’s important, therefore, that the athlete acquire the coping skills required to help him or her through the loss—with professional help if necessary.

Athletes should try to maintain a sense of identity and importance through activities that help them feel good. They should express their needs and concerns to the health care team. It is helpful to identify any negative mental responses to injury, then to reframe them to promote a positive approach to healing: be aware of the current level of function and of what function is lost, and then move beyond those limitations to envision the future level of function.

The athlete needs to ask for and receive help and to be surrounded by emotionally and physically supportive people. Interaction with those who hinder the healing process should be eliminated or minimized.

Athletes in today’s society have many problems to deal with, including multiple personal and professional demands, increased stress, and injury. Some athletes know how to successfully deal with injury, and others have a hard time coping with it. The athlete may need professional help to get through the injury healing process, and the massage therapist needs to be supportive.

Injury can negatively impact the mind, emotions, and body. Rehabilitation is often a time of emotional distress.

Injury rehabilitation affects a person in many ways, including the following:

• Change in status relative to peers

• The need for discipline and compliance with rehabilitation programs

• Decreased independence and control

Signs that an athlete is having some problems include these:

When these issues are recognized by the massage therapist, a referral is necessary. Avoid the tendency to try to fix them. Ultimately, therapeutic massage is secondary to, although supportive of, the medical team, including the sport psychologist. Respect for professional boundaries and honoring scope of practice are essential. However, because of the time that massage therapists spend with athletes and the compassionate quality of the professional interaction, we may be the first to notice difficulties. Athletes may share information with massage professionals that was not provided to others working with them.

As massage professionals interested in the sports massage career specialty, we want to understand and help an athlete through an injury. We need to understand the demands placed on the whole person while addressing the injury.

Sport psychology interventions can minimize negative experiences and maximize recovery from injury. Mental training enhances performance in rehabilitation and sport, improving the ability to return to play. Outcome of an injury, degree of pain, and expected performance are important factors in determining how fast rehabilitation should occur.

When coaches or trainers adopt an attitude that injured athletes are worthless, they create an environment in which athletes will continue to participate while hiding their injury, increasing the likelihood of further injury. Similarly, coaches who emphasize a strong will to compete and win, no matter what the athlete’s physical status, promote the idea of sacrificing one’s body for the team, which can cause players to take unhealthy risks and become injured.

All athletes should understand that the nature of participation in sports dictates that at some time, pain and injury are very likely to occur. However, instead of stressing the inherent risks associated with sport, the focus should be on doing those things that can minimize the chances of injury, such as making certain that the athlete is fit, is practicing safe sport techniques, and is learning to recognize when his or her body is saying that something is wrong. If athletes are confident that they have done as much as they can to reduce the likelihood of injury, perhaps their risk of injury will indeed be minimized. Teaching athletes how to distinguish between the “normal” pain and discomfort associated with training and “injury” pain is of vital importance. Athletes who do not learn to make this distinction often become seriously injured because they do not recognize the onset of minor injuries and do not modify their training regimens accordingly.

The individual’s current medical status must also be addressed. Conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and high blood pressure, as well as orthopedic concerns, must be factored into the exercise prescription for rehabilitation or fitness-based programs for performance.

Learning stress management skills is important for athletes—both for enhancing performance and for reducing injury risk. Psychological stress has been shown to predict increases in injury. Stress is thought to increase the risk of injury because of the unwanted disruption in concentration or attention and the increased muscle tension associated with heightened stress. Athletes especially prone to injury seem to be those who experience considerable life stress. They have little social support from others, possess few psychological coping skills, and are apprehensive, detached, and overly sensitive.

Sport massage therapists should learn to treat the whole athlete, not just the injury. They must communicate effectively and factually without instilling fear or unrealistic expectations and with concern for the athlete’s feelings.

No one can work closely with human beings without becoming involved with their emotions and, at times, their personal problems. The sport massage therapist is placed in numerous daily situations in which close interpersonal relationships are important. Understanding an athlete’s fears, frustrations, and daily crises is essential, along with knowing when to refer individuals with emotional problems to the proper professionals. Injury prevention includes dealing with both psychological and physiologic attributes of the athlete. The athlete who competes while angry, frustrated, or discouraged, or while suffering from some other emotional disturbance, is more prone to injury than one who is better adjusted emotionally. Because of the emotional intensity surrounding competing athletes, the massage therapist working with this population needs to attend to his or her own mental health.

Massage Application

Generally speaking, injured athletes can experience feelings of vulnerability, isolation, and low self-worth. Denial of the reality of the injury also comes into play. All of these feelings can adversely affect the athlete and his rehabilitation. The injured athlete may experience a number of personal reactions besides a sense of loss. These may include physical, emotional, and social reactions. A fairly predictable response to injury often occurs in five sequential stages: (1) denial, (2) anger, (3) grief, (4) depression, and (5) reintegration. Athletes who fail to move through these five stages may suffer adverse psychological effects related to the injury. Such adverse effects are more likely to occur if the injury is season-ending or career-ending.

Some degree of psychological distress and discomfort accompanies most major athletic injuries. However, more serious problems of poor psychological adjustment to injury are often preceded by the following warning signs:

• Feelings of anger and confusion

• An obsession with the question of returning to play

• Exaggerated bragging about accomplishments

• Guilt about letting one’s team down

When these warning signs are detected, the athlete should be referred to a sport psychologist or another mental health professional.

Certain factors are commonly seen among athletes going through adjustment to injury and rehabilitation. Severity of injury usually determines length of rehabilitation. Regardless of length of rehabilitation, the injured athlete has to deal with three reactive phases of the injury and rehabilitation process:

Other factors that influence reactions to injury and rehabilitation include the athlete’s coping skills, past history of injury, social support, and personality traits. All athletes do not necessarily have all of these reactions, nor do all reactions fall into the suggested sequence.

Athletes who deal with their feelings and focus on the future rather than the past have a tendency to advance through rehabilitation at an accelerated rate. Those who have a high degree of hardiness, a well-developed self-concept, and good coping strategies and mental skills are more likely to recover rapidly and fully from injury than athletes who lack these qualities.

Athletes who lack motivation and are depressed or in denial have difficulty with the rehabilitation process.

After injury, particularly one that requires long-term rehabilitation, the athlete may have problems adjusting socially and may feel alienated from the rest of the team. The athlete may believe that there has been little support from coaches and teammates. The athletic trainer is responsible for rehabilitation and becomes the primary source of social support. The massage therapist can play an important part in this support process only if the professionals work together. Conflict among professionals can adversely affect this process.

One of the outcomes of an injury may be secondary gain. This can be a beneficial “time-out” (time to rest and refocus) with a decrease in pressures and expectations. Secondary gain can both support and interfere with the healing process.

Psychological strategies and communicative skills used by the sport psychologist help the athlete move successfully through the rehabilitation process. Care needs to be taken to maintain appropriate boundaries during this vulnerable time for the athlete.

The following strategies are used by the massage therapist to support the medical staff:

Coping skills: The massage professional has a limited role in this area. Teaching self-help is appropriate as long as it does not conflict with other treatment being provided.

Education about the injury: When sharing information, make sure that it is correct and does not conflict with information provided by other professionals.

Coping with nonparticipant status and other changes: These changes include separation from family, friends, and teammates. The massage therapist is supportive but defers to the medical and coaching staff.

Managing emotional reactions to injury and regaining sense of control: The massage therapist can target the massage to address the physical effects of emotional turmoil and refers to the sport psychologist for additional mental support.

Pain management: The massage therapist can play an active role in helping the athlete to cope with pain related to injury, surgery, and rehabilitation after returning to play.

During injury rehabilitation, management of the emotional demands of treatment and rehabilitation consists of the following:

• Adhering to physical therapy

• Maintaining motivation for rehabilitation

• Goal setting and achievement

• Consultation with medical and rehabilitation staff as needed

• Coping with issues associated with returning to sport activity such as fear of reinjury, intrusive or disruptive thinking regarding the injury, and loss of confidence

The massage therapist plays an important supportive role during this phase of rehabilitation and reinforces awareness of physical healing to support rehabilitation.

Stress

Stress is often associated with situations or events that are difficult to handle. How a person views things also affects the level of stress. Unrealistic or high expectations increase the stress response.

Stress may be linked to external factors, such as

Stress can also come from internal factors, such as

It is one thing to be aware of stress in daily life, but it is another to know how to change it. Stress is not just in the mind. It is a physical response to an undesirable situation, and it has the potential to control one’s life. Stress has many sources. Mild stress can result from being caught in a traffic jam, standing in line at a store, or getting a parking ticket. Stress also can be severe and cause major health problems. Divorce, family problems, and the death of a loved one can be devastating.

Stress can be short-term (acute) or long-term (chronic). Acute stress is a reaction to an immediate or perceived threat. Everyday life sometimes poses situations that are not short-lived, such as relationship problems, loneliness, and financial or health worries. The pressures may seem unrelenting and can cause chronic stress.

When a person’s coping behavior is ineffective, a physical stress response occurs to meet the energy demands of the situation. First, the stress hormone adrenaline is released. Then, the heart beats faster, breathing quickens, and blood pressure rises. The liver increases its output of blood sugar, and blood flow is diverted to the brain and large muscles. The massage therapist should recognize signs and symptoms of nonproductive sympathetic dominance.

After the threat or anger passes, the body relaxes again. One may be able to handle an occasional stressful event, but when it happens repeatedly, such as with chronic stress, the effects multiply and are compounded over time.

For example, a football player endures week after week of hits in a season, or a source of pain, and may reach a point of not being able to handle it anymore.

It is evident that there is too much stress for a person to cope with when the following telltale signs appear:

• Sleep problems (sleeps all the time or can’t sleep at all)

• Loss of appetite or can’t stop eating

• Trouble with relationships (e.g., no longer gets along with friends and family members)

Signs of chronic stress, which can damage overall health, include the following:

Coping with Stress

The following measures can help in coping with stress.

Sleep well. Sleep is very important and can provide the athlete with the energy needed to face each day. Going to sleep and awakening at a consistent time may help the person sleep more soundly. Restorative sleep should be a major goal of massage.

Eat a balanced diet that includes a variety of foods and provides the right mix of nutrients to keep the body systems working well. When healthy, the athlete will be better able to control stress and pain.

Change the pace of your daily routine.

Be positive. It helps to spend time with people who have a positive outlook and a sense of humor. Laughter actually helps ease pain because it releases the chemicals in the brain that give a sense of well-being.

Relaxation methods trigger the body’s relaxation response. The relaxation response is a group of physiologic changes that cause decreased activity of the sympathetic nervous system and support parasympathetic function. Relaxation methods are helpful in reducing the physical sensations of the stress response and help to manage stress by

Massage is a major relaxation modality. It supports physical relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, word repetition, and guided imagery.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

This technique involves relaxing a series of muscles, one at a time. First, raise the tension level in a group of muscles, such as those in a leg or an arm, by tightening the muscles and then relaxing them. Concentrate on letting the tension go out of each muscle. Then, move on to the next muscle group. Do not tense muscles near pain sites. Massage supports the practice of progressive muscle relaxation.

Word Repetition

Choose a word or phrase that is a cue for relaxing, and then repeat it. While repeating the word or phrase, breathe deeply and slowly, and think of something that gives pleasant sensations of warmth and heaviness.

Guided Imagery

Also known as visualization, this technique involves lying quietly and picturing yourself in a pleasant and peaceful setting. Try to experience the setting with all of the senses, as if you are actually there. For instance, imagine lying on the beach. Picture the beautiful blue sky, smell the salt water, hear the waves, and feel the warm breeze on your skin. The messages your brain receives as you experience these sensations help you to relax (Box 8-1).

Restorative Sleep

Restorative sleep is extremely important for anyone who is an athlete or in rehabilitation. Almost everyone has occasional sleepless nights, perhaps owing to stress, heartburn, or drinking too much caffeine or alcohol. How much sleep is enough varies for different individuals. Although  hours of sleep is about average, some people feel fine on only 5 or 6 hours of sleep, and others need 9 or 10 hours a night.

hours of sleep is about average, some people feel fine on only 5 or 6 hours of sleep, and others need 9 or 10 hours a night.

Lack of restorative sleep can affect energy levels, and restorative sleep helps bolster the immune system, fighting off viruses and bacteria.

Insomnia is the most common of all sleep disorders. Insomnia includes difficulty going to sleep, staying asleep, or going back to sleep when awakened early. It may be temporary or chronic. About one out of three people have insomnia at some point in their lives. Simple changes in one’s daily routine, lifestyle, and habits may result in better sleep (Box 8-2).

Insomnia becomes more prevalent with age. As a person gets older, the following changes often occur that may affect sleep.

Between the ages of 50 and 70, more time is spent in stages 1 and 2 of non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and less time in stages 3 and 4. Stage 1 is transitional sleep, stage 2 is light sleep, and stages 3 and 4 are deep (delta) sleep—the most restful kind. Because one is sleeping lighter in stages 1 and 2, one is more likely to wake up. With age, the internal clock often speeds up, and a person may get tired earlier in the evening and consequently wake up earlier in the morning.

A change in daily activity can disrupt sleep patterns regardless of whether the client is less or more physically or socially active. Consistent activity as part of daily activities helps promote a good night’s sleep. The retired client may have more free time and because of that may drink more caffeine or alcohol or take a daily nap. These things can interfere with sleep at night.

A change in health can affect sleep patterns. Chronic pain associated with conditions such as arthritis and back problems, as well as depression, anxiety, and stress, can interfere with sleep. Older men often develop noncancerous enlargement of the prostate gland (benign prostatic hyperplasia), which can cause the need to urinate frequently, interrupting sleep. In women, hot flashes and urinary urgency that accompany menopause can be equally disruptive. Other sleep-related disorders, such as sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome, become more common with age. Sleep apnea causes one to stop breathing periodically throughout the night and awaken. Restless legs syndrome causes an unpleasant sensation in the legs and an uncontrollable desire to move them, which may awaken one or prevent one from falling asleep. Nutritional depletions may be the reason for restless legs syndrome; therefore, nutritional supplements may help. A nutritionist or a physician can help by making recommendations.

The following strategies promote restorative sleep:

Stick to a schedule. Keep bedtime and wake time routines on as constant a schedule as possible.

Limit time in bed. Too much time in bed can promote shallow, unrestful sleep. Try to get up at the same time each morning, regardless of when you go to bed.

Avoid “trying” to sleep. The harder a person tries, the more awake the person becomes. Reading or listening to music until drowsy helps one to fall asleep naturally.

Avoid or limit caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine. Caffeine and nicotine can keep a person from falling asleep. Alcohol can cause unrestful sleep and frequent awakenings.

Reset the body’s clock. If falling asleep too early, use light to push back the internal clock. In the evenings, if it is still light, go outside in the sun or sit near a bright light.

Check medications. If medications are taken regularly, check with the doctor to see if the medications may be contributing to sleep disturbances. Also check the labels of over-the-counter products to see if they contain caffeine or other stimulants such as pseudoephedrine.

Don’t put up with pain. Make sure that any pain reliever being taken is effective enough to control pain while sleeping.

Find ways to relax. A warm bath or a light snack before bedtime may help prepare for sleep. Massage also may help promote relaxation.

Limit naps. Naps can make it harder to fall asleep at night.

Minimize sleep interruptions. Close the bedroom door or create a subtle background noise, such as running a fan, to help drown out other noises. Sleep in a different room if the bed partner snores.

Adjust bedroom temperatures. The room should be comfortably cool.

Limit nighttime use of the bathroom by drinking less toward evening.

The training and competing athlete needs an appropriate amount of restorative sleep. This is typically 8 to 9 hours at night and a 1-hour nap. Playing schedules and travel to different time zones disrupt an athlete’s sleep patterns. Sleeping in a different bed when traveling can be a problem.

Summary

This chapter briefly describes the mental and emotional world of the athlete. The role of the sport psychologist is becoming increasingly important. More people are seeking professional assistance with coping and performance, especially in managing stress. Stress is both mental and physical. It is in this area that massage is most beneficial.

The massage therapist must not take on the role of psychologist. Instead, the massage professional provides a skilled and compassionate touch, a nonjudgmental and no-advice-giving presence, and a supportive and quiet experience.

Visit the Evolve website to download and complete the following exercises.

1. How does sport psychology influence physical performance?

2. If a client was asking questions about mental performance to support physical performance, how would you refer him or her to a qualified sport psychologist?

3. Based on physiologic outcomes, what methods of relaxation and meditation would create similar effects as massage?

4. A client indicates that she feels “in the zone” after massage. She also expresses concern that during skating she has a hard time finding “the zone.” How might the massage therapist help her understand the zone experience?

5. A client has experienced a serious knee injury requiring surgical repair and a long, involved rehabilitation program. How and when would you approach a referral to a sport physiologist?

6. Write a case study (fictional or real) about the circumstances that would indicate that a client needs a referral to help with mental and emotional coping.

Example: A 29-year-old golfer has played in eight tournaments and he hasn’t made the cut (got into the final money-making rounds). He is not sleeping and has been experiencing headaches and an “upset stomach.”

7. Provide an example of a behavior that might be displayed for each of the five stages of response to injury.

Example: Denial—Client continues to run daily even though his repeatedly sprained ankle is painful and he is limping

8. Using the case study you wrote about in Question 6 and the approach used by sport psychologists, identify at least three methods that would be appropriate for helping this client.

9. A client indicates during the massage that even though he is sleeping 7 hours at night and taking a short nap in the afternoon, he is still tired. What questions would you ask the client to obtain more specific information?

10. Develop a self-help handout to give clients to support restorative sleep.

11. Again, using the case study from Question 6, develop a massage treatment plan that would complement the treatment of a sport psychologist.