Assessment for Sports Massage and Physical Rehabilitation Application

Outcome Goals and Care or Treatment Plans

Assessment Using Joint Movement

Kinetic Chain Assessment of Posture

Palpation of the Skin and Superficial Connective Tissue

Palpation of Superficial Connective Tissue Only

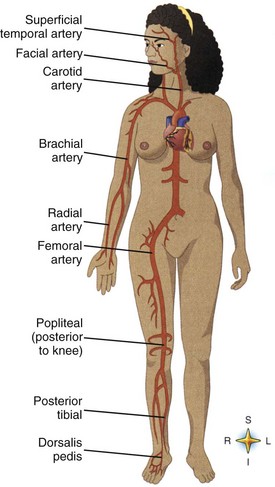

Palpation of Vessels and Lymph Nodes

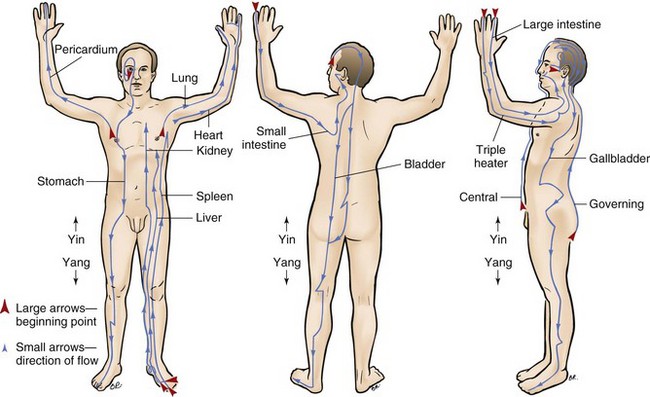

Understanding Assessment Findings

After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following:

1 Describe assessment for the sport and fitness population.

2 Apply a clinical reasoning process to treatment plan development.

3 Develop outcome goals that are quantifiable and qualifiable.

4 Adapt charting methods to the athletic population.

5 Complete a comprehensive history.

6 Complete a comprehensive physical assessment.

7 Perform postural assessment.

8 Perform basic orthopedic tests to assess for joint injury.

9 Analyze movement assessment findings.

10 Perform muscle strength assessment.

11 Describe and assess kinetic chain function.

13 Perform palpation assessment.

14 Integrate clinical reasoning into the treatment plan using assessment findings.

15 Relate assessment data to first-degree, second-degree, and third-degree dysfunction, and categorize the adaptation response to stage 1, 2, or 3 pathology.

16 Integrate ongoing assessment data channeled into appropriate massage treatment strategies.

Assessment

The massage therapist working with athletes, physical rehabilitation, and those involved with fitness has an expanded assessment responsibility. Assessment identifies the structures that need to be worked with, creates a clear intention about treatment goals, provides a baseline of objective information to measure the effectiveness of the treatment, and helps identify conditions that are contraindicated. When working with a client who is striving for optimal performance or who has pain, dysfunction, or disability, the massage therapist needs to gather information about both long-term and short-term treatment goals and relevant data about activities and training activity, as well as about pain or decreased function.

Information from the athletic trainer, coaches, or other professionals is important. The massage therapist must understand and apply assessment information provided by the trainer. If at any time you do not understand, ask clarifying questions. Information gathered by the massage therapist should be shared with the athletic trainer or other appropriate member of the sport and/or medical team in a concise and intelligent manner.

A massage treatment plan based on efficient biomechanical movement should focus on reestablishing or supporting effective movement patterns. Biomechanically efficient movement is smooth, bilaterally symmetric, and coordinated, with easy, effortless use of the body. Functional assessment measures the efficiency of coordinated movement. During assessment, noticeable variations need to be considered.

Once the treatment plan has been determined, the massage therapist needs to develop strategies for achieving the goals pertaining to the therapeutic massage. Teamwork is essential, with cooperation and consensus among the various professionals attending to the client. It is important for the massage therapist to maintain an appropriate scope of practice and not infringe on the professional responsibilities and expertise of others.

Clinical Reasoning Process

As the volume of knowledge pertaining to massage increases, and as soft tissue modalities such as massage are integrated into the areas of sport fitness and physical rehabilitation, it is becoming increasingly important to be able to think or reason through an intervention process and justify its effectiveness. Therapeutic massage practitioners must be able to gather information effectively, analyze that information to make decisions about the type and appropriateness of an intervention, and evaluate and justify the benefits derived from the intervention.

Effective assessment, analysis, and decision making are essential in meeting the needs of each client. Routine or a recipe-type application of therapeutic massage does not work for this population because each person’s set of presenting circumstances and outcome goals is different. An experienced sports massage professional possesses effective clinical reasoning skills targeted to this complex population.

Fact gathering is an initial part of the clinical reasoning process. Each unique client situation needs to be thoroughly researched. This text provides only a portion of the information needed. Additional research is almost always necessary.

Every massage professional who works with athletes needs to have a medical dictionary and comprehensive texts on athletic training, kinesiology, and pathology, as well as resources on the particular sport and references on medication and nutritional supplements. See the resource list in this text for recommendations. The Internet is also a vast resource.

Each sport has its ideal performance requirement and common injuries; however, a sprain in a football player, a soccer player, or a skate boarder is still a sprain. The sprain should be addressed according to the recommendations in this text. Understanding the demands of the sport is important. However, it is not necessary for the massage professional to be an expert in the sport activity. The sport activity is the context that the massage outcomes support.

Subjective and objective assessments are also sources of facts and are the major focus of this chapter. Analysis of factual data in the assessment leads to treatment plan development.

Outcome Goals and Care or Treatment Plans

Outcome goals need to be quantified. This means that they are measured in terms of objective criteria such as time, frequency, 1 to 10 scales, measurable increase or decrease in ability to perform an activity, and/or measurable increase or decrease in sensation, such as relaxation or pain.

Outcome goals also need to be qualified. How will we know when the goal is achieved? What will the client be able to do after the goal has been reached that he or she is not able to do now? For example, How fast will the client be able to run? What performance skills will the client be able to perform?

After the analysis of history and assessment data is complete and problems and goals have been identified, a decision needs to be made about the care or treatment plan. Depending on the situation, the massage treatment plan may need to be approved by appropriate supervising personnel.

Short-term goals typically support a session-by-session process and are dependent on the current status of the client. Long-term goals typically support recovery, performance, or rehabilitation. Long-term goals focus on what is being worked toward. Short-term goals focus on what currently is being worked on, as well as incremental steps toward achieving long-term goals. Short-term goals should not be in conflict with long-term goals.

For example, a golfer is involved in a conditioning program in preparation for going on tour. She has been working with the strength and conditioning coach on core strength and cardiovascular fitness. She has also been working with the golf coach on swing mechanics. Long-term goals for this client are to maintain range of motion (ROM) and manage a chronic tendency for low back pain. During this particular session, the client has indicated that she has a headache and delayed-onset muscle soreness. The focus of the current massage must consider both short-term and long-term goals. Short-term goals are to reduce headache pain and fluid retention as part of the existing long-term treatment plan.

How much time is allocated to each set goal depends on the adaptive capacity of the client. For example, massage targeting connective tissue application as part of the long-term goals plan may be reduced or eliminated in the areas where delayed-onset muscle soreness exists. Muscle energy application may require more effort than the client is willing to expend because of the headache.

It is this ever-changing dynamic of past history, current conditions, and future outcomes that makes any sort of massage routine useless. Each and every session is uniquely developed and applied on the basis of multiple factors. Many influencing factors must be considered when one is treating athletes or those in physical rehabilitation of any type. Assessment is the identification of all of these influences. Clinical reasoning is the sorting and developing of an appropriate treatment session.

Charting

As the treatment plan is implemented, it is recorded sequentially, session by session, in some form of charting process such as SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment [analysis], and plan). The plan is reevaluated and adjusted as necessary. This process should have been learned in entry level massage training.

Various charting methods are used in the sport and fitness realm. Regardless of the particular style, the basic SOAP plan is easily modified to other charting styles. Be very clear with supervisory personnel, usually the trainer, about the type and depth of information included on the client’s chart.

Good record keeping provides the therapist with the information necessary to communicate with health care and other personnel and furnishes accurate details about what treatment goals are specified, the methods of massage used, and the effectiveness of treatment.

Assessment Details

How extensive the assessment is depends on whether you are working under the direction of a doctor, a trainer, or another health care provider or are working independently. It is the responsibility of the primary care provider to take a thorough history, perform a complete examination, and inform the massage therapist regarding the client’s condition and desired outcomes for the massage. If you are working independently, it is your responsibility to perform the appropriate comprehensive assessment, especially to note contraindications and to clarify treatment goals.

This text assumes that the reader already has completed a comprehensive therapeutic massage course of study that included assessment procedures such as history taking, physical assessment, treatment plan development, and charting.1

The following procedures are recommended for targeting this specific population.

History

The history interview provides subjective information pertaining to the client’s health history, the reasons for massage, a history of the current condition, a history of past illness and health, and a history of any family illnesses that may be pertinent. It also contains an account of the client’s current health practices.

Targeting this information to the athlete or person in physical rehabilitation is the focus of this text. In addition to the general history, anyone who is working with an athlete or a person in physical rehabilitation needs to explore the following for each client:

• Surgery or medical procedures

• Therapeutic exercise activities

• Physical therapy intervention

• Training types such as strength and conditioning and agility

• Cognitive load (how much mental training required)

The client’s history may vary depending on whether the problem is the result of sudden trauma or is chronic. The following questions should be addressed if the athlete has an acute injury. Usually it is the doctor or trainer who performs the initial injury assessment:

• Has the client hurt the area before?

• How did the client hurt the area?

• What was heard when the injury occurred—a crack, snap, or pop?

• How bad was the pain and how long did it last?

• Is there any sense of muscle weakness?

• How disabling was the injury?

• Could the client move the area right away?

• Was the client able to bear weight for a period of time?

• Has a similar injury occurred before?

• Was there immediate swelling, or did the swelling occur later (or at all)?

For an athlete with a chronic condition, ask the following:

• What was the nature of the injury (trauma or repetitive use)?

• What is the nature of the pain—hot, pokey, sharp?

• When does the pain occur—when bearing weight or after activity?

• What injuries have occurred in the past?

• What first aid and therapy, if any, were given for these previous injuries?

Additional questions address when the client first noticed this condition to help to identify any previous incident or injury that occurred before the current condition:

Typically, a gradual onset suggests an overuse syndrome, postural stresses, or somatic manifestations of emotional or psychological stresses common in athletes.

Ask the client to point to as well as explain the area of complaint.

It is also important to know whether the client has had massage therapy before, whether it was helpful, and the type of massage application.

If the client has taken pain medication within 4 hours of assessment and treatment, the medication may be giving the client a false sense of comfort during assessment and during massage. Be aware of antiinflammatories, muscle relaxers, and so forth.

Is the client getting better, worse, or is the client in need of a referral?

Gestures

Pay attention to gestures used by the client. The general guidelines for gestures listed here are not written in stone. Professional experience indicates that those listed here are fairly dependable starting points when interpreting an individual’s body language.

It is the professional’s responsibility to understand what a gesture means for a particular individual.

The following are common gestures:

• A finger pointing to a specific area suggests an acupressure or motor point hyperactivity or a joint problem. What the pointing means depends on the area indicated.

• If the finger is pointed to a specific area and then the hand swipes in a certain direction, it may be a trigger point problem.

• If the area is grabbed, pulled, or held and is moved as if being stretched, this often indicates muscle or fascial shortening.

• If movement is needed to show the area of concern, the area may need muscle lengthening combined with muscle energy work to prepare for the stretch and reset of neuromuscular patterns.

• If the client moves into a position and then acts as if stuck, the area may need connective tissue stretching.

• If the client draws lines on his body, this may indicate nerve entrapment in the fascial planes or grooves.

Symptoms

It is important to determine how often the client notices the dysfunction or disability. Is it once a day, 2 or 3 days a week, once a week, or constant? Grade 1 and 2 sprains and strains to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments usually hurt when they are being used, and are relieved with rest. Constant pain may be associated with severe injury or underlying pathology. A client with constant pain should be referred to a physician.

The more serious the condition, the longer it will last.

Typical words used by the client to describe the symptoms are “stiff,” “achy,” “tight,” “stuck,” and “heavy.” These words are associated with muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joint capsules and their associated connective tissue and usually describe simple tension or mild overuse of the soft tissue or edema. If an ache is more than mild, is frequent, and lasts a long time, it is more serious and represents inflammation. A referral is required to rule out a more serious condition.

Typically, tight means an increase in neuromuscular activity. Achy and fat often indicate fluid retention or swelling. Stiff sensations often indicate a connective tissue pliability issue. Heavy sensation of the limbs indicates a firing pattern or gait reflex problem. Stuck sensations often mean a joint problem.

Other terms used to describe symptoms include the following:

Sharp, stabbing, tearing describes a more severe injury to the musculoskeletal system or a nerve root condition. This type of sensation is experienced with muscle or ligament tears, especially when the muscle or ligament is being used. The sensation is usually relieved at rest. A nerve root inflammation can elicit a sharp or stabbing pain, independent of movement.

Tingling, numbing, picky describes a nerve compression near the spine or in the extremities, or a circulation impairment.

Throbbing, hot is associated with acute injury inflammation and swelling, such as an abrasion puncture wound or an acute bursitis. Severe throbbing is a contraindication to massage.

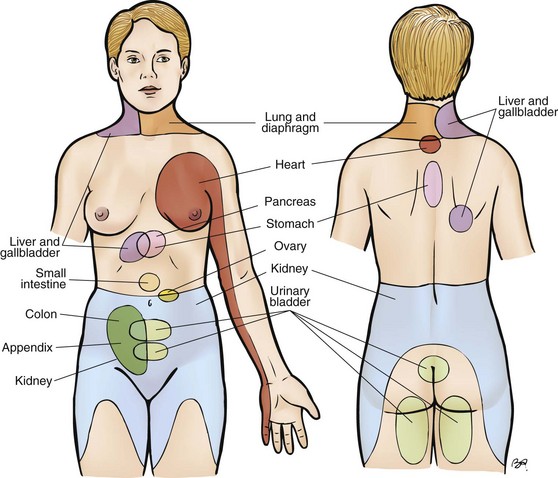

Gripping, cramping is typically used to describe a serious condition, often a nerve root injury or a visceral condition. Gripping and cramping pain is a contraindication to massage and requires referral to a doctor.

The client can choose from the following descriptors:

Irritation or injury to the soft tissue can refer to the extremities, with diffuse pain and aching. Nerve entrapment and trigger point pain can radiate. Sharp well-localized pain in the extremities felt even at rest typically indicates a nerve root problem and requires a referral.

Ask the client to rate his or her pain on a 0 to 10 scale, with 10 being the worst pain ever experienced (incapacitating pain) and 0 being no pain. Moderate pain (5 to 9) interferes with a person’s ability to perform sport-related activities. Mild pain (1 to 4) does not interfere with a person’s activities of daily living but may interfere with sport performance.

The most simple strains and sprains of the musculoskeletal system are irritated by too much movement and are relieved by rest. When a condition hurts more with rest, this indicates either inflammation or pathology.

• What activities make the condition worse—moving, sitting, standing, walking, or resting?

• What sport movement is affected—running, jumping, cutting, swinging, acceleration, or deceleration?

As the soft tissue heals, it feels good to move the injured area. Stretching tight muscles, shortened ligaments, and joint capsules feels good, despite some mild discomfort. Acute injuries involving the soft tissue are painful with large movements and are relieved with rest. Muscle guarding makes stretching painful.

Pain caused by inflammation and tumors is worse at night. Constant, gripping pain that is worse at night requires immediate referral to a doctor. An area that hurts at night but is relieved with movement usually indicates inflammation. Joint pain and stiffness with fascial shortening are usually worse in the morning.

Clarifying assessment questions to ask include the following:

The client should demonstrate for the massage therapist. Trust the client’s impressions. They usually are right. Then translate what the client is saying into a massage application.

The client should draw a picture of his or her condition. When the client draws the picture, give as few directions as possible. Evaluate the drawing for location and intensity of the symptom. Does the client use hard zigzag lines or small or large circles? Then ask the client to explain.

All the history information should be consolidated and considered when treatment plans and session outcomes are documented.

![]() See the Evolve website that accompanies this book for an example of a history taking form.

See the Evolve website that accompanies this book for an example of a history taking form.

Physical Assessment

After the history is complete, the physical assessment is performed. The objective data are obtained during physical assessment.

Accurate assessment is best achieved using a sequence to ensure that all relevant information has been gathered. A major aspect of a massage session is palpation assessment.

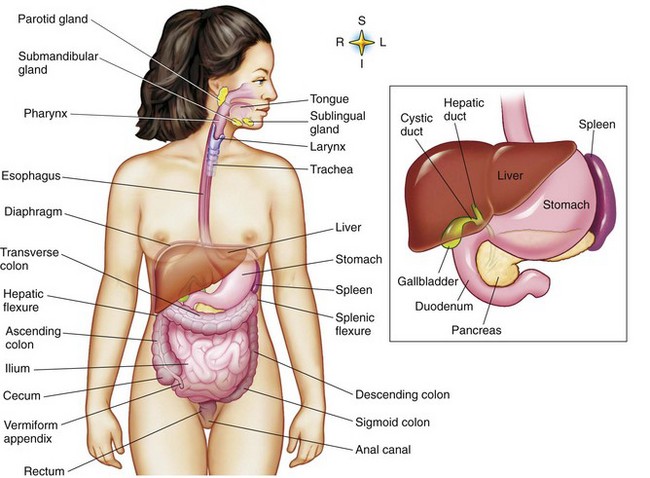

In general, physical assessment includes the following:

Identify any scars or muscle atrophy. Scars may indicate prior surgery or prior injury and reveal that the area is compromised. Ask the client to describe how he or she received the scar.

An area of atrophy may have been deconditioned owing to lack of use, or this may indicate neurologic involvement. Simple atrophy can be a result of immobilization caused by prior fracture or lack of use due to pain.

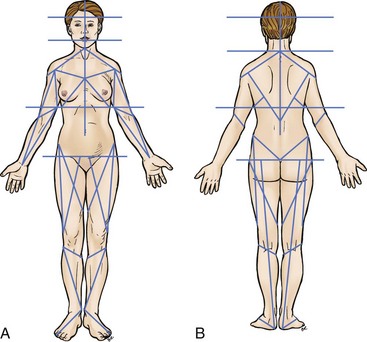

Physical Assessment of Posture

Note the posture of the client in standing and seated positions, as well as the posture or position of the area of complaint. Look for areas of asymmetry. Asymmetry usually results when overly tense muscles or shortened connective tissue pulls the body out of alignment.

Direct trauma pushes joints out of alignment. Weak stabilizing mechanisms, such as overstretched ligaments or inhibited antagonist muscles, contribute to the problem. In these situations, a chiropractor, an osteopath, or another trained medical professional skilled in skeletal manipulation is needed. Often a multidisciplinary approach to client care is necessary.

First, observe the client during general movement as opposed to formal assessment to identify natural function. Then, perform the following structured standing assessment and compare the findings.

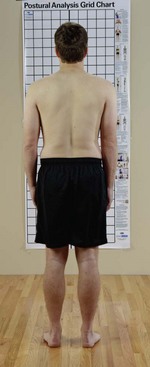

Standard Posture Front View

Standard Posture Back View

• Head: neutral position neither tilted nor rotated

• Shoulders: level, not elevated or depressed

• Scapulae: neutral position, medial borders essentially parallel and approximately 3 to 4 inches apart

• Thoracic and lumbar spines: straight

• Pelvis: level with both posterior superior iliac spines in same transverse plane

• Hip joints: neutral position neither adducted nor abducted or rotated (internal or external)

Standard Posture Side View

• Head: neutral position, not tilted forward or backward

• Cervical spine: normal curve, slightly convex to anterior

• Scapulae: flat against upper back

• Thoracic spine: normal curve, slightly convex to posterior

• Lumbar spine: normal curve, slightly convex to anterior

• Pelvis: neutral position, anterior superior iliac spine in same vertical plane as symphysis pubis

• Hip joints: neutral position, leg vertical at right angle in sole of foot

Note: An imaginary line should run slightly behind the lateral malleolus, through the middle of the femur, the center of the shoulder, and the middle of the ear.

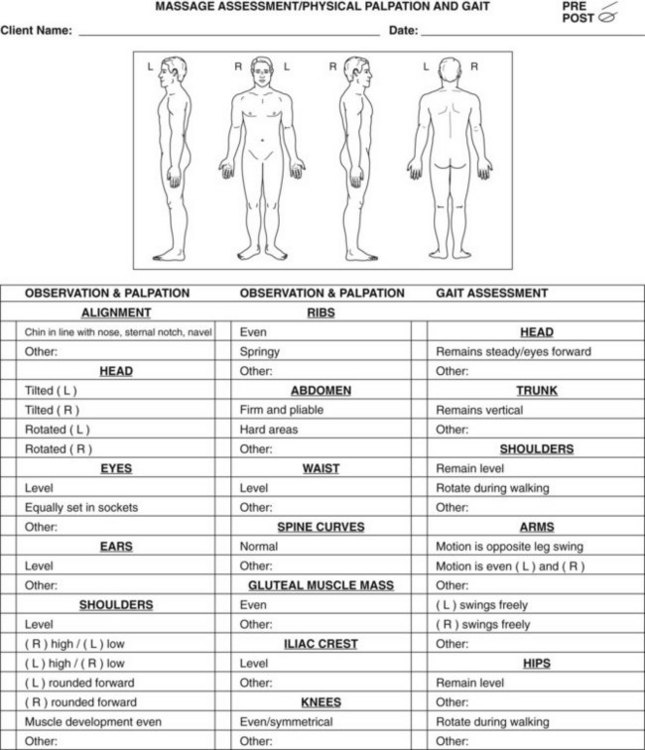

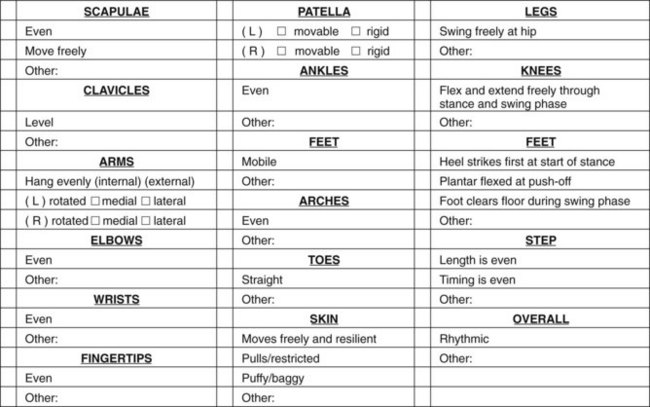

Chart the findings and relate them to the client’s history (Figure 10-1).

FIGURE 10-1 Physical assessment form. (Feel free to copy this form to use as an assessment tool.) (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 5, St Louis, 2013, Mosby.)

For the physical assessment, the main considerations are body balance, efficient function, and basic symmetry (Box 10-1).

The body is not perfectly symmetric, but the right and left halves of the body should be similar in shape, ROM, and ability to function. The greater the discrepancy in symmetry, the greater is the potential for soft tissue dysfunction.

Three major factors influence posture: heredity, disease, and habit. These factors must be considered when evaluating posture. The easiest influence to adjust is habit. By normalizing the soft tissue and teaching balancing exercises, the massage practitioner can play a beneficial role in helping clients overcome habitual postural distortion. Effects may arise from occupational habits (e.g., a shoulder rotation from golf) and recreational habits (e.g., a forward-shoulder position in a bike rider), or they may be sleep-related (long-term use of high pillows).

Clothing, sport equipment, shoes, and furniture affect the way a person uses his or her body. Tight clothing or equipment around the neck restricts breathing and contributes to neck and shoulder problems. Restrictive belts or tight pants also limit breathing and affect the neck, shoulders, and midback. Shoes with high heels and those that do not fit the feet comfortably interfere with postural muscles. Shoes with worn soles imprint the old postural pattern, and the client’s body assumes the dysfunctional pattern if he or she puts them back on after the massage. If postural changes are to be maintained, it is important to wear shoes that do not have worn soles.

Sleep positions can contribute to a wide range of problems. Furniture that does not support the back or that is too high or too low perpetuates muscular tension. Competing athletes travel and therefore change beds often. The seats in airplanes are seldom comfortable for athletes.

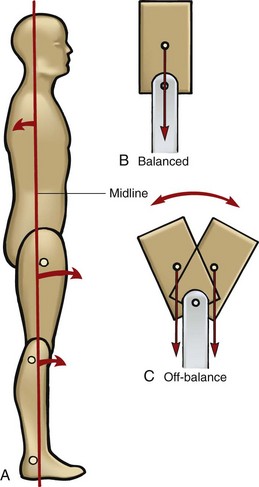

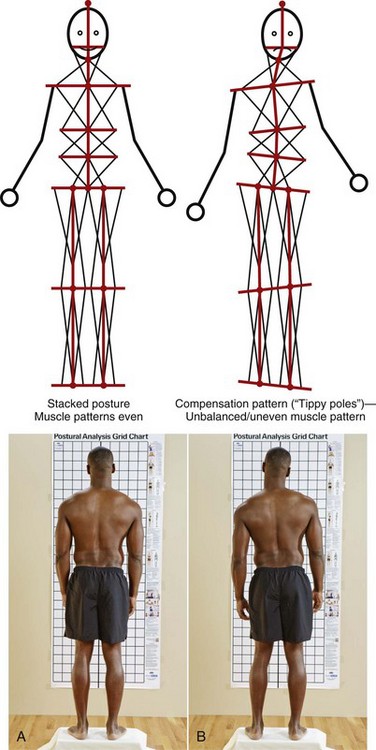

When assessing posture, it is important for the massage therapist to notice the complete postural pattern. Most compensatory patterns occur in response to external forces imposed on the body. However, if the client has had an injury, maintains a certain position for a prolonged period, or overuses a body area, the body may not be able to return to a normal dynamic balance efficiently. The balance of the body against the force of gravity is the fundamental determining factor in a person’s posture or upright position. Even subtle shifts in posture demand a whole body compensatory pattern (Figure 10-2).

FIGURE 10-2 In normal relaxed standing (A), the leg and trunk tend to rotate slightly off the midline of the body but maintain a counterbalance force. Balance is achieved in B, but not in C. Whenever the trunk moves off this midline balance point, the body must compensate. (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 3, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

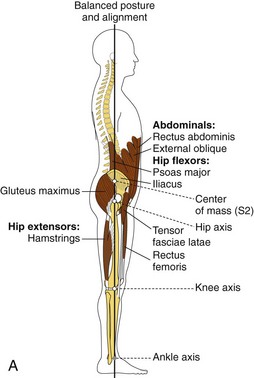

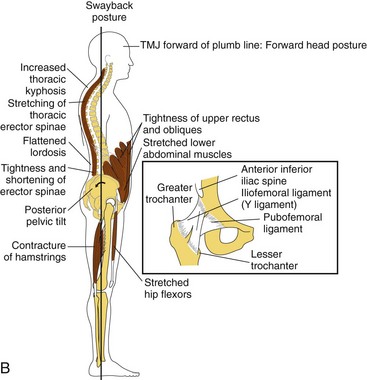

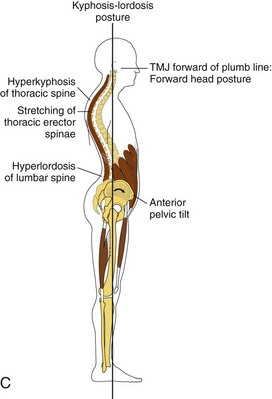

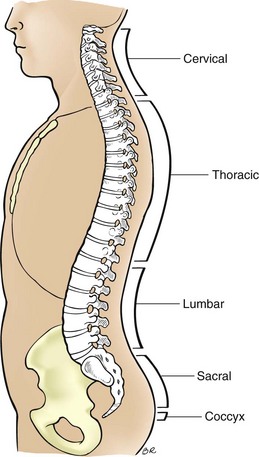

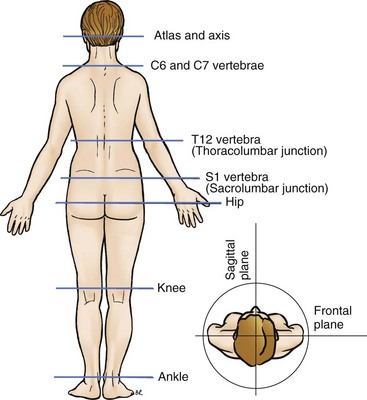

Cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral curves develop because of the need to maintain an upright position against gravity (Figure 10-3).

FIGURE 10-3 Normal spinal curves. (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 5, St Louis, 2013, Mosby.)

Standing posture requires various segments of the body to cooperate mechanically as a whole. Passive tension of ligaments, fascia, and connective tissue elements of the muscles supports the skeleton. Muscle activity plays a small but important role. Postural muscles maintain small amounts of contraction that stabilize the body upright in gravity by continually repositioning the body’s weight over the mechanical balance point.

In relaxed symmetric standing, both the hip and the knee joints assume a position of full extension to provide the most efficient weight-bearing position. The knee joint has an additional stabilizing element in its “screw home” mechanism. The femur rides backward on its medial condyle and rotates medially about its vertical axis to lock the joint for weight bearing. This happens only in the final phase of extension. The hamstrings are the major muscles that resist the force of gravity at the knees.

At the ankle joint, bones and ligaments do little to limit motion. Passive tension of the two-joint gastrocnemius muscle (i.e., the muscle crosses two joints) becomes an important factor. This stabilizing force is diminished if high-heeled shoes are worn. For example, rodeo riders wear cowboy boots. The heel of the shoe puts the gastrocnemius on a slack. If these heels are worn constantly, the muscle and the Achilles tendon shorten.

Posture is primarily determined by hereditary factors, such as bone structure and muscle type, and even by habitual movement patterns. These can create natural imbalances, but alone they do not normally lead to painful conditions until later in life. They can, however, combine with other stresses such as athletic activity, and together can lead to injury. Little can be done to change these hereditary factors, and regular exercise and soft tissue treatment are often the only ways of avoiding such symptoms.

Upright posture is maintained by a series of muscles running down the body. These muscles need to balance each other, in terms of strength and tension, and together must resist the forces of gravity. Any postural change will nearly always be in a downward and forward direction because fatigue or injury reduces the ability of postural muscles to combat gravity. This creates increased curvature in particular sections of the spine, which can be seen by the therapist when observing the client’s standing posture.

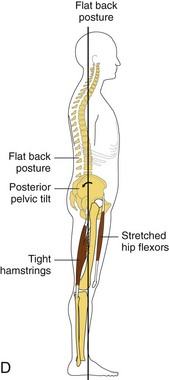

Postural dysfunction occurs in the three planes of movement (sagittal, frontal, and transverse), as well as in supination and pronation (Figures 10-4 and 10-5).

Assessment of Joint and Muscle Function

The more the fascia muscle tissue structure is researched, the more we understand that the concept of individual muscles is flawed. It is necessary to rethink the functional and structural aspect of contractile tissues—muscle tissue—as a continuum of function within spans of connective tissues such as fasciae, ligaments, and tendons. The idea of individual muscles and specific attachments is ingrained and it will take a long time to shift the paradigm. Throughout this text, the functional unit has been emphasized; however, knowledge of individual muscle names and locations remains valuable and will be used. Although the muscular system looks highly complicated, it is important to realize that the actual mechanics involved in movement are simple. A muscle can do only two things: it can contract and shorten, and it can relax and lengthen. The system is a complex pattern of movement composed of many simple levers and pulleys. Movement is created by muscle shortening, which pulls together bones that are connected at the joint.

Many muscles working in functional units provide the widest variety of movements and the ability to do them with stability, control, and efficiency. For example, the knee is basically a hinge joint capable of moving on only one plane, and so, theoretically, it should need only one pulley (muscle) to flex it and one to extend it. However for extension, there are the four quadriceps muscles, each of which pulls across the joint in a slightly different direction. During flexion, three hamstrings accomplish the same thing. This muscle interaction stabilizes the joint and enables it to adapt to variations in movement and to the random direction of forces from the outside environment. The whole of the muscular system works in unison to enable the body to cope with the stresses caused by gravity when movement takes place. It is important to see movement in terms of patterns of activity (movement strategies) taking place within a system rather than as the action of individual muscles. Almost all movement strategies involve the gait (walking) process.

Overuse problems develop in parts of a system that are put under greater stress, or repetitive use, compared with the rest of the system. The running action, for instance, does not involve just the leg muscles. Many muscles work to create a complicated pattern of rotation and spiral movements throughout the entire body. If this did not happen, and if movement is confined to the legs, then all the stress of impact and push-off will be absorbed by the ankle, knee, and hip joints, and the forces on these joints will cause damage. The spiraling movement up the body absorbs the stress and distributes the impact through many joints. Because no individual structure absorbs too much stress, the human body is able to function for many years.

Coordinated movement involves many muscles working together in a pattern to create the power and control needed to accomplish a task. Each muscle has a preferred function within a movement pattern; therefore, a particular movement will involve greater effort from certain individual muscles. For example, kicking a soccer ball involves a strong effort from the quadriceps muscles. Each of the four muscles within the group acts on the joint from a different angle; therefore, depending on the degree of rotation in the lower leg and the angle of force, one muscle may have to keep working slightly more than the rest.

The muscular system develops according to how the body is used. Each individual has unique patterns of muscle function adaptation, many of which are beneficial and are in harmony with the person’s activities and lifestyle, although some will be negative or excessive. Assessment provides information about beneficial or detrimental function.

For example, a midfield soccer player who often has to pass the ball with the inside of the foot will tend to use the vastus medialis, and the adductors may be involved. Therefore, the soccer player would naturally develop increased strength in the vastus medialis and adductors while training. Although this may appear to create an imbalance within the other quadriceps muscles, it could be natural for the individual; therefore, this may not be a situation requiring remedial treatment. The same imbalance found in a distance runner complaining of patellofemoral syndrome or groin pain would be a treatment priority.

Microtrauma

A muscle can suffer acute strain with its fibers being torn, if overused or overloaded. The same can occur on a microscopic level, even if just a few fibers are overused. When this breakdown occurs on a microscopic level, the pathologic changes that take place are the same as with any soft tissue tear: bleeding, swelling, muscle tension, guarding in surrounding tissues, and scar tissue formation. The delayed-onset muscle soreness experienced in muscles after hard exercise is due in part to this type of trauma (microtrauma).

Scar tissue can continue to build up gradually with repetitive activity. Adhesions can form, affecting the elasticity within that particular area of the muscle and making muscles vulnerable to further microtrauma. This process results in fibrotic changes in the muscle.

As function deteriorates in a small part of the muscle, it can create imbalance within a functional muscle unit (a group of muscles working together). As the condition builds up gradually, it may develop unnoticed in the early stages. Increased tension can then put excessive stress on adjoining structures such as the tendons, which can become more vulnerable to acute trauma. Biomechanical alterations develop as natural movement patterns compensate. In the long run, the overuse syndrome can lead to many problems, both locally and in other parts of the body. Several muscle dysfunctions can develop.

Massage is possibly the most effective way of identifying this type of problem. Palpation assessment identifies fibrotic changes in a muscle. This is the most important benefit of general preventive massage.

These areas should be treated in much the same way as any chronic muscle injury. Mechanical force is applied to break down scar tissue to improve flexibility and to realign tangled fibers.

Static positions, such as standing at attention in the military for long periods of time, put stress on specific tissues, causing microtrauma in a way similar to the active type of overuse, but from isometric overload instead of eccentric or concentric function. Lack of movement in the muscles also slows blood and lymph flow through the area, which can increase congestion and add to the problem.

Active Movements

General understanding of biomechanics is especially important for the massage professional who works with athletes. The assessment question “What do you want your body to do?” will result in answers such as “run,” “ride,” “throw,” “catch,” “jump,” “bend,” “rotate,” “lift,” and “press.” The massage professional needs to break down the movements of the activity, assess for soft tissue changes that interfere with these movements, and then identify massage applications that can support these movements. For example, in response to the assessment question, “What do you need to do that you are having problems with?” I will often hear something like “run backward” or “swing.” Then I will ask the athlete to show me, and while I observe the movements, I can begin to target the specific outcomes.

Perhaps the athlete says, “I can’t stand on my left foot with the same balance as my right foot” (which is important for many sport activities). I ask the athlete to stand on the right foot, and I observe and palpate to determine the “normal” activity that he or she can perform. This is a general assessment and treatment principle. The least affected movement pattern or structure becomes “normal” for evaluation and comparison purposes. Regardless of the situation, in practical application this works. I then ask the athlete to stand on the left foot, where the problem exists, and I compare it with the more normal function. Then I assess for the difference between the two—tissue texture and pliability, ROM, and firing patterns. Choices about what treatments to use are based on the assessment information.

The next part of the examination is divided into two sections. In active movement assessment, the massage therapist asks the client to perform movements in specific directions in all planes of movement. The squat assessment is particularly beneficial. In passive movement assessment, the massage therapist moves the client.

Injuries and dysfunctions of the musculoskeletal system are symptomatic when the injured area is actively moved. More complex conditions such as inflammation of the nervous system, systemic conditions such as heart disease, and pathologies such as tumors are not significantly affected by movement. If an area does not hurt at rest, but it does hurt with movement, soft tissue dysfunctions are indicated.

Remember that each individual joint movement pattern is part of an interconnected aspect of the neurologic and fascial coordination pattern of muscle movement called the kinetic chain. The support system involves the tensegric nature of the body’s connective design. Posture and movement dysfunctions identified in an individual joint pattern must be assessed and treated in broader terms of kinetic chain interactions, muscle tension/length relationships, and the effects of stress and strain on the entire system.

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-1: Multiplanar Assessment (Functional Assessment).

Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-1: Multiplanar Assessment (Functional Assessment).

Range of Motion

Remember that each person is unique, and many factors influence available range of motion. Just because a joint does not have the textbook range of motion (ROM) does not mean that what is displayed is abnormal. Abnormality is indicated by nonoptimal function. This can be seen as a limitation or an exaggeration in the “textbook normal” range of motion (Box 10-2).

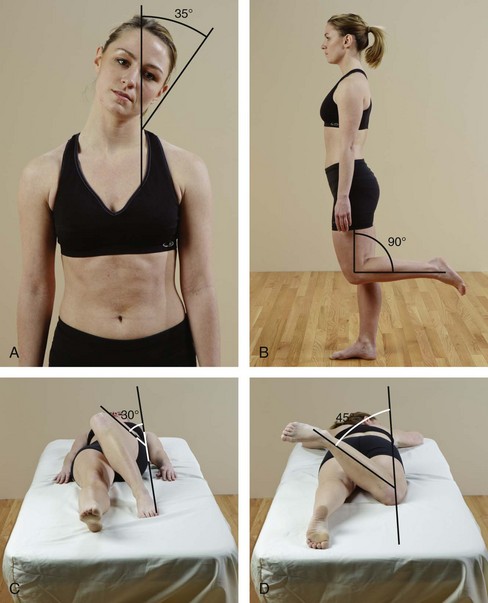

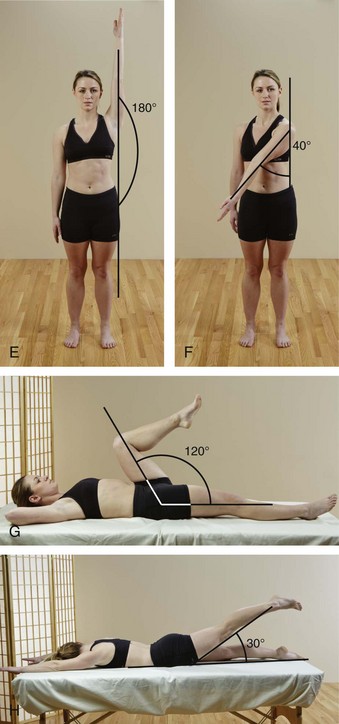

ROM is measured in degrees. Joint movement is measured from the neutral line of anatomic position. Movement of a joint in the sagittal, frontal, or transverse plane is described as the number of degrees of flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and internal and external rotation (Figure 10-6). For example, the elbow has approximately 150 degrees of flexion at the end range and 180 degrees of extension. Anything less than this is hypomobility, and anything more is considered hypermobility. Massage therapists typically estimate degrees of movement, and other professionals use specific equipment to obtain precise information. The normal ROM of joints is found in anatomy texts such as Mosby’s Essential Sciences for Therapeutic Massage.

FIGURE 10-6 Examples of approximate degrees of movement. A, 35 degrees of lateral flexion. B, 90 degrees of knee flexion. C, 30 degrees of internal hip rotation. D, 45 degrees of external hip rotation.

E, 180 degrees of shoulder abduction. F, 40 degrees of horizontal shoulder adduction. G, 120 degrees of hip flexion. H, 30 degrees of hip hyperextension.

Each movement pattern (e.g., flexion and extension of the elbow and knee, circumduction and rotation of the shoulder and hip, movement of the trunk and neck) is assessed in sequential positioning in each area of all available movement patterns, testing for strength, range, and ease of movement. Functional assessment is the combination of all previously described assessments.

Range of motion is assessed through joint movement.

When active joint movement is performed, the client moves the joint through the planes of motion that are normal for that joint. Any pain, crepitus, or limitation that is present during the action should be reported. This assessment identifies what the client is willing or able to do.

Passive joint movement is performed when the massage therapist moves the joint passively through the planes of motion that are normal for the joint. The assessment identifies limited (hypomobility) or excessive movement (hypermobility) of the joint.

Passive joint movement is done carefully and gently to allow the client to fully relax the muscles while the assessment is performed. The client reports the point at which pain or bind, if present, occurs. The massage therapist stops the motion at the point of pain or bind, unless assessing for joint end-feel. Then a tiny increase in resistance is used to assess the quality of movement just past the bind. Passive joint movement assessment provides information about the joint capsule and ligaments and other restricting mechanisms, such as myofascial soft tissue.

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-2: Passive Joint Movement (Range of Motion).

Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-2: Passive Joint Movement (Range of Motion).

Basic Orthopedic Tests

The main reason for orthopedic tests is to assess for bone, joint, ligament, and tendon injury. Orthopedic tests also identify impingement areas. The most common structures impinged are nerves, blood vessels, and tendons, and occasionally muscles. Performing orthopedic tests can determine whether or not a referral is necessary. Even if you do not perform orthopedic assessment as part of the massage assessment process, it is likely that a client will tell you that he or she had a positive result when assessed by another health professional such as an athletic trainer, physical therapist, chiropractic physician, or medical or osteopathic doctor.

Most orthopedic tests assess stress areas to be evaluated in an effort to evaluate pain, joint play, and muscle extensibility. Because of the strain involved during some orthopedic tests, care must be taken to avoid further injury. Before any orthopedic tests are conducted, an area must be free from fracture or neoplasm (an abnormal growth). Furthermore, any client with characteristics such as severe spasm, pain with unknown etiology (cause), or pain that wakes him or her up at night, should not be evaluated with orthopedic tests until a full medical evaluation can be completed to address these unexplained symptoms.

A positive test will reproduce the client’s symptoms. If the client does not want you to perform the test, this is called an apprehension sign. Additional positive signs are change in stability of the joint and changes in pulses.

Assessment Using Joint Movement

The ROM of a joint is measured in degrees. A full circle is 360 degrees. A flat horizontal line is 180 degrees. Two perpendicular lines (as in the shape of a capital “L”) create a 90-degree angle. When the ROM of a joint allows 0 to 90 degrees of flexion, anything less is hypomobile and anything more is hypermobile. A great degree of variability exists among individuals as to actual normal ROM. The degrees provided are general guidelines. ROM is measured from the anatomic position. Anatomic position is considered 0 degrees of motion, regardless of whether the client is standing, supine, or side-lying.

Decreased ROM may result from pain or changes in joint position, or from soft tissue bind. If loss of motion is not a result of pain, more information is needed to determine whether lack of motion is caused by adhesions in the joint capsule, muscle guarding, joint degeneration, or other factors.

Increased ROM that is significantly different from the other side indicates moderate to severe injury to the ligaments, joint capsule, or both. Increased ROM on both sides compared with normal anatomic ROM suggests a generalized hypermobility syndrome and potential instability in the joints.

During actual movement assessment, the following categories are noted by the massage therapist:

Range of motion (ROM). Is the motion normal, decreased, increased? Determining normal ROM is more complex than it might seem. You need to consider the client’s age and sex, sport type, and muscle texture. ROM is lessened as we age. Women typically have greater ROM than men. If the complaint is in the extremities, begin with the noninvolved side, and always compare both sides. The less involved side becomes the “normal side” for comparison.

Limits to joint movement. Joints have various degrees of ROM. Anatomic, physiologic, and pathologic barriers to motion exist. Anatomic barriers are determined by the shape and fit of bones at the joint. The anatomic barrier is seldom reached because the possibility of injury is greatest in this position. Instead the body protects the joint by establishing physiologic barriers.

Physiologic barriers are the result of limits in ROM imposed by protective nerve and sensory function to support optimal function. An adaptation in the physiologic barrier so that the protective function limits instead of supports optimal functioning is called a pathologic barrier. Pathologic barriers often are manifested as stiffness, pain, or a “catch.”

When using joint movement techniques, remain within the physiologic barriers. If a pathologic barrier limits motion, use massage techniques to gently and slowly encourage the joint to increase the limits of ROM to the physiologic barrier.

The stretch on the soft tissues, such as muscles, tendons, fasciae, and ligaments, and the arrangement of the joint surfaces determine the ROM of the joint and therefore the joint’s normal end-feel.

Overpressure is the term used when the massage therapist gradually applies more pressure when the end of the available passive range of joint motion has been reached. The sensation transmitted to the therapist’s hands by tissue resistance at the end of the available range is the end-feel of a joint.

Types of End-Feel

Soft tissue approximation end-feel occurs when the full ROM of the joint is restricted by normal muscle bulk; it is painless and has a feeling of soft compression. Muscular/ tissue stretch end-feel occurs at the extremes of muscle stretch, as in the hamstrings during a straight leg raise; it has a feeling of increasing tension, springiness, or elasticity. Capsular stretch, or leathery, end-feel occurs when the joint capsule is stretched at the end of its normal range, such as with external rotation of the glenohumeral joint; it is painless and has the sensation of stretching a piece of leather. Bony, or hard, end-feel occurs when bone contacts bone at the end of normal range, as in extension of the elbow; it is abrupt and hard.

Abnormal End-Feel

Many types of abnormal end-feel have been identified. Empty end-feel occurs when there is no physical restriction to movement except the pain expressed by the client. Muscle spasm end-feel occurs when passive movement stops abruptly because of pain; there may be a springy rebound from reflexive muscle spasm. Boggy end-feel occurs when edema is present; it has a mushy, soft quality. Springy block, or internal derangement, end-feel is a springy or rebounding sensation in a noncapsular pattern; this indicates loose cartilage or meniscal tissue within the joint. Capsular stretch (leathery) end-feel that occurs before normal range indicates capsular fibrosis with no inflammation. Bony (hard) end-feel that occurs before normal range indicates bony changes or degenerative joint disease or malunion of a joint after a fracture.

An empty end-feel with no bind or stability indicates a seriously damaged joint, and referral is required.

Analysis of Active Movement

If active movement is painful, ask the client to describe its location, quality, and severity. The three stages of healing that elicit pain at different ranges of the movement are as follows:

1. Acute conditions yield pain before the normal ROM.

2. Subacute conditions give pain at the end of the normal range.

3. Chronic conditions may elicit pain with slight overpressure at the end of active or passive motion.

Pain with passive motion at different ranges of the movement indicates a stage of healing that is the same as for active motion.

Active and passive ROM can identify limits of movement. If an empty capsular or hard end-feel is identified, the joint is damaged. Referral is needed for acute conditions. ROM limited by muscle contraction may indicate an underlying problem with joint laxity, and caution is indicated before muscle guarding is reduced. Proceed slowly until a balance between increased ROM and maintenance of joint stability is achieved. If joint stability is reduced, the client usually experiences pain in the joint for a day or two after the massage. Simple edema around a joint is managed with lymphatic drain. Any unexplained edema should be referred for diagnosis.

ROM should improve as the client’s tissues normalize with general massage. Progressive mobilization in ROM is an indication of improved function. Never force an increase in ROM. Instead, allow it to be a natural outcome of effective massage application.

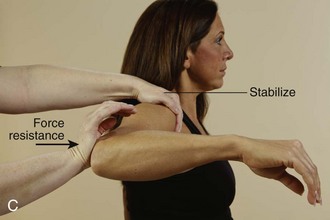

Muscle Strength Assessment

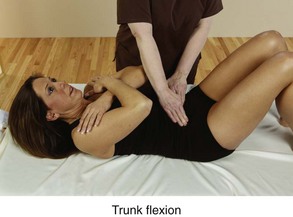

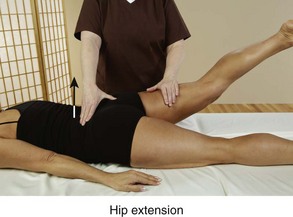

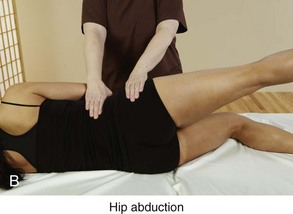

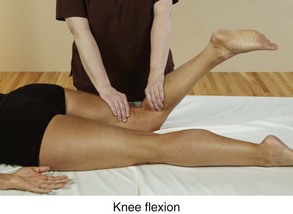

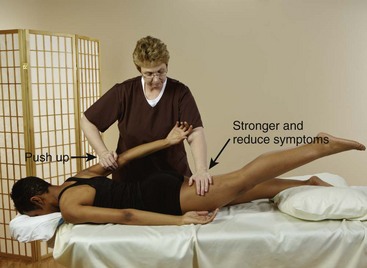

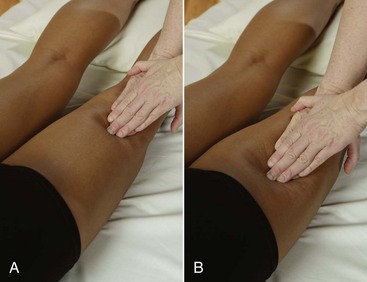

Muscle strength assessment is performed by applying resistance to a specific group of muscles. Resistance (pressure against) applied to the muscles is focused at the end of the lever system (Figure 10-7).

For example, when the function of the shoulder is assessed, resistance is focused at the distal end of the humerus, not at the wrist. When extension of the hip is assessed, resistance is applied at the end of the femur. When flexion of the knee is assessed, resistance is applied at the distal end of the tibia.

Resistance is applied slowly, smoothly, and firmly at an appropriate intensity as determined by the size of the muscle mass. Stabilization is essential to assess movement patterns accurately. Only the area assessed is allowed to move. Movement in any other part of the body must be stabilized. A stabilizing force is usually applied by the massage therapist. As one hand applies resistance, the other provides stabilization. Sometimes the client can provide stabilization by holding onto the massage table. Some methods use straps to provide stabilization. The easiest way to identify the area to be stabilized is to move the area to be assessed through the ROM. At the end of the range, some other part of the body begins to move; this is the area of stabilization. Return the body to a neutral position. Provide appropriate stabilization to the area identified and begin the assessment procedure (Figure 10-8).

During assessments, muscles should be able to hold against appropriate resistance without strain or pain from the pressure, and without recruiting or using other muscles. Appropriate resistance is applied slowly and steadily and with just enough force to induce muscles to respond to the stimulus. Large muscle groups require greater force than small ones. The position should be easy to assume and comfortable to maintain for 10 to 30 seconds. Contraindications to this type of assessment include joint and disk dysfunction, acute pain, recent trauma, and inflammation.

When a movement pattern is evaluated, two types of information are obtained in one functional assessment.

First, when a jointed area moves into flexion and the joint angle is decreased, the prime mover and synergists concentrically contract, the antagonists eccentrically function while lengthening, and the fixators isometrically contract and stabilize. Body-wide stabilization patterns also come into play to assist in allowing the motion. During assessment, resistance can be applied to load the prime mover groups, and synergists to assess for neurologic function of strength and, to a lesser degree, endurance, as the contraction is held for a period of time. At the same time, the antagonist pattern of the tissues that are lengthened during positioning for the functional assessment can be assessed for increased tension patterns or connective tissue shortening. Dysfunction shows itself in limited ROM by restricting the movement pattern. Therefore, when a jointed area is placed into flexion, the extensors are assessed for increased tension or shortening. When the jointed area moves into extension, the opposite becomes the case. The same holds for adduction and abduction, internal and external rotation, plantar flexion and dorsiflexion, and so on.

![]() For a comprehensive strength testing sequence, see the Evolve website.

For a comprehensive strength testing sequence, see the Evolve website.

Interpreting Muscle-Specific Testing Findings

Muscle strength testing determines a muscle’s force of concentric contraction. The preferred method is to isolate the muscle or muscle group by positioning the muscle with its attachment points as close together as possible. The muscle or muscle group being tested should be isolated as specifically as possible.

The client holds or maintains the contracted position of the muscle isolation while the therapist slowly and evenly applies counterpressure to pull or push the muscle out of its isolated position. The massage therapist must use sufficient force to recruit a full response by the muscles being tested but not enough to recruit other muscles in the body. The client should not hold his or her breath during assessment. If strength testing is done this way, there is little chance that the therapist will injure the client. As with all assessment, it is necessary to compare the muscle tested with a similar area—usually the same muscle group on the opposite side.

Another muscle testing method is to compare a muscle group’s strength with its antagonist pattern. The body is designed so that the flexor, internal rotator, and adductor muscles are about 25% to 30% stronger than the extensor, external rotator, and abductor muscles. It is also designed so that flexors and adductors usually work against gravity to move a joint. The main purposes of extensors and abductors are to restrain and control the movement of flexor and adductor muscles and to return the joint to a neutral position. Less strength is required because gravity is assisting the function. A third form is strength testing to assess for facilitator and inhibitor patterns during gait function. ![]()

Strength testing should reveal a difference in the pattern between flexors, internal rotators, and adductors, and between extensors, external rotators, and abductors in an agonist/antagonist pattern. These groups should not be equally strong. Flexors, internal rotators, and adductors should show greater muscle strength than extensors, external rotators, and abductors (Box 10-3).

Muscle strength testing indicates the following possible findings:

• A strong and painless contraction indicates a normal structure.

• A painful but strong contraction indicates an injury or dysfunction in the tested muscle-tendon-periosteal unit.

• A weak and painless contraction may be caused by one or more of the following situations:

• The muscle is inhibited owing to a hypertonic antagonist pattern.

• The muscle is inhibited owing to dysfunction or injury to adjacent joint structures.

• A spinal nerve condition is causing impingement on or irritation of the motor nerve and weakness in the muscles innervated by that nerve.

• The muscle is deconditioned owing to disuse as a result of previous injury or disease.

• The length-tension relationship is long.

Postural and Phasic Muscles

Postural (stabilizer) and phasic (mover) muscles are made up of different kinds of muscle fibers. Postural muscles have a higher percentage of slow-twitch red fibers, which can hold a contraction for a long time before fatiguing. Phasic muscles have a higher percentage of fast-twitch white fibers, which contract quickly but tire easily. These two types of muscle develop different types of dysfunction and are tested differently.

Postural Muscles

Postural (stabilizer) muscles are relatively slow to respond compared with phasic muscles. They do not produce bursts of strength if asked to respond quickly, and they may cramp. They are the deliberate, slow, steady muscles that require time to respond. Using the analogy of the tortoise and the hare, these muscles are the tortoise. Inefficient neurologic patterns, muscle tension, reorganization of connective tissue with fibrotic changes, and trigger points are common in postural muscles.

If posture is not balanced, postural muscles must function more like ligaments and bones. When this happens, additional connective tissue develops in the muscle to provide the ability to stabilize the body in gravity. The problem is that the connective tissue freezes the body in the position because, unlike muscle, which can actively contract and lengthen, connective tissue is static.

Postural muscles tend to shorten and increase in tension when under a strain-tension-length relationship. This information is important when attempting to assess which muscles are tense and short, and therefore in need of lengthening, and which groups of muscle are apt to develop connective tissue changes and require stretching. Connective tissue shortening is dealt with mechanically through forms of stretch. Hypertension of concentric contraction muscles is dealt with through muscle energy methods and reflexive lengthening procedures.

Phasic Muscles

Phasic (mover) muscles jump into action quickly and tire quickly. It is more common to find musculotendinous junction problems in phasic muscles. The four most common problems are microtearing of muscle fibers at the tendon, inflamed tendons (tendonitis), tendons adhering to underlying tissue, and bursitis.

Phasic muscles usually weaken in response to postural muscle shortening. Sometimes the weakened muscles also shorten. This shortening allows the weak muscle to retain the same contraction power on the joint. It is important not to confuse this condition with hypertense muscles. These muscles are inhibited and weak.

Phasic muscles occasionally become overly tense and short. This almost always results from some sort of repetitive behavior and is a common problem in athletes. Phasic muscles also become short in response to a sudden posture change that causes the muscles to assist the postural muscles in maintaining balance. These common, inappropriate muscle patterns often result from an unexpected fall or near-fall, an automobile accident, or some other trauma. Basic massage methods discussed in this text can be used to reset and retrain out-of-sync muscles.

Kinetic Chain Assessment of Posture

Consider the body as a circular form divided into four quadrants: a front, a back, a right side, and a left side, with divisions on the sagittal and frontal planes; the body must be balanced in three dimensions to withstand the forces of gravity.

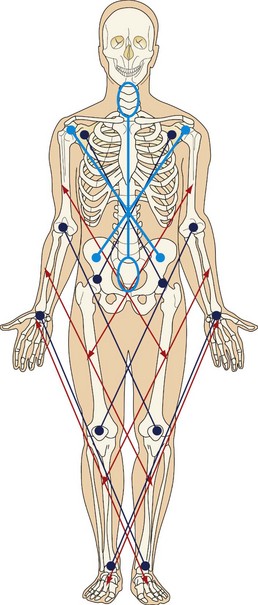

The body moves and is balanced in gravity in the following transverse plane areas that easily allow movement: atlas; C6 and C7 vertebrae; T12 and L1 vertebrae (the thoracolumbar junction); L4, L5, and S1 vertebrae (the sacrolumbar junction); and hips, knees, and ankles (Figure 10-9). If a postural distortion exists in any of the four quadrants or within one of the jointed areas, the entire balance mechanism must be adjusted. This occurs as a pinball-like effect that jumps front to back and side to side in the soft tissue between the movement lines (see Figure 10-9).

FIGURE 10-9 Quadrants and movement segments. (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 3, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

To gain an understanding of postural balance, use a pole of some type (a broom handle without the broom portion will work). Tie a string around the pole. Now, try to balance the pole on its end with the string. Note that you work opposite the pattern when trying to counter the fall pattern of the pole. If the pole tends to fall forward and to the left, you apply a counterforce back and to the right.

This is also what the body does if part of it moves off the balance line. The body is made up of many different poles stacked on top of one another. The poles stack at each of the movement segments. Muscles between the movement segments must be three-dimensionally balanced in all four quadrants to support the pole in that area. Each area needs to be balanced. If one pole area tips a bit to the right, the body compensates by tipping the adjacent pole areas (above and/or below) to the left. If a pole area is tipped forward, adjacent poles are tipped back. A chain reaction occurs, such that when compensating poles tip back, their adjacent areas must counterbalance the action by tipping forward. This is how body-wide compensation patterns occur.

Whether the pole areas sit nicely on top of each other with evenly distributed muscle action or whether they are tipped in various positions and counterbalanced by compensatory muscle actions, the body remains balanced in gravity. However, the “tippy pole” pattern is much more inefficient than the “balanced pole pattern” (Figure 10-10).

FIGURE 10-10 Posture balance and imbalance. Stacked poles (A) versus tippy pole (B) postural influences on the body. (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 3, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

Intervention plans attempt to normalize the balance process by relaxing the tension pattern in overly tight and short areas, strengthening muscles in corresponding taut and long but weak areas, and allowing the poles to straighten out. If a pole is permanently tippy, as with scoliosis or kyphosis, intervention plans attempt to support appropriate compensation patterns and prevent them from increasing beyond what is necessary for postural balance.

Muscle imbalance, discovered by observation, by palpation, and through muscle testing procedures, often indicates how the body is compensating for postural and movement imbalances. Muscle testing also can locate the main muscle problems. When the primary dysfunctional group of muscles is concentrically contracted against resistance, the main compensatory patterns are activated, and the other body compensation patterns are activated and exaggerated. The massage professional must then become a detective, looking for clues to unwind the pattern by concentrating on methods that restore symmetry of function.

A major muscle problem is overly tense muscles. If these muscles can be relaxed, lengthened, and, if necessary, stretched to activate connective tissue changes, the rest of the dysfunctional pattern often resolves.

If the extensors and abductors are stronger than the flexors and adductors, major postural imbalance and postural distortion result. Similarly, if the extensors and abductors are too weak to balance the other movement patterns, the body curls into itself, and nothing works properly.

If gait and kinetic chain patterns are inefficient, more energy is required for movement, and fatigue and pain can result.

Shortened postural (stabilizer) muscles must be lengthened and then stretched. This takes time and uses all the massage practitioner’s technical skills. Because of the fiber configuration of the muscle tissue (slow-twitch red fibers or fast-twitch white fibers), techniques must be sufficiently intense and must be applied long enough to allow the muscle to respond.

Shortened and weak phasic muscles must first be lengthened and stretched. Eventually, strengthening techniques and exercises will be needed. Long and weak muscles need therapeutic exercise. If the hypertense phasic muscle pattern is caused by repetitive use, the muscles can be normalized with muscle energy techniques and then lengthened. Overly tense muscles often increase in size (hypertrophy). Muscle tissue that has undergone hypertrophy begins to return to normal if it is not used for the activity. The client must reduce the activity of that muscle group until balance is restored, which usually takes about 4 weeks. Athletes often display this pattern and very likely will resist complete inactivity. A reduced activity level and a more balanced exercise program, combined with flexibility training, can be beneficial for them. Refer these individuals to appropriate training and coaching professionals, if indicated.

People usually complain of problems in the tight but long eccentrically functioning and inhibited muscle areas. Massage in these areas makes the symptoms worse because massage further lengthens the area. Instead, identify the shortened tissues and apply massage to lengthen and stretch tense areas. Assessment must identify the concentrically contracted shortened areas so that correction can be applied.

Muscle Firing Patterns

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-3: Muscle Activation Sequences (Muscle Firing Patterns).

Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-3: Muscle Activation Sequences (Muscle Firing Patterns).

A muscle firing pattern (or muscle activation sequence) is the sequence of muscle contraction involvement with agonist and synergist that best produces joint motion. Muscles also contract, or fire, in a neurologic sequence to produce coordinated movement. If the muscle firing pattern is disrupted, and if muscles fire out of sequence or do not contract when they are supposed to, labored movement and postural strain result. Firing patterns can be assessed by initiating a particular sequence of joint movements and palpating for muscle activity to determine which muscle is responding to the movement.

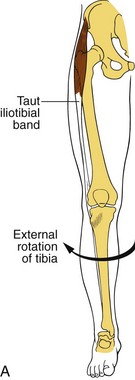

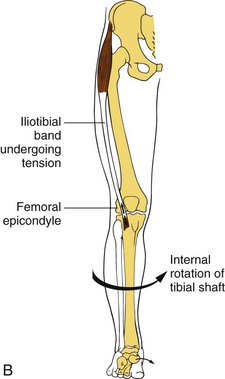

The central nervous system recruits appropriate muscles in specific muscle activation sequences to generate the appropriate muscle function of acceleration, deceleration, or stability. If these firing patterns are abnormal, with the synergist becoming dominant, efficient movement is compromised and the joint position is strained. The general activation sequence is (1) prime mover, (2) stabilizer, and (3) synergist. If the stabilizer has to also move the area (acceleration) or control movement (deceleration), it typically becomes short and tight. If the synergist fires before the prime mover, the movement is awkward and labored.

If one muscle is tight and short, reciprocal inhibition occurs. Reciprocal inhibition exists when a tight muscle decreases nervous stimulation of its functional antagonist, causing it to reduce activity. For example, a tight and short psoas decreases (inhibits) the function of the gluteus maximus. The activation and force production of the prime mover (gluteus maximus) are decreased, leading to compensation and substitution by the synergists (hamstrings) and stabilizers (erector spinae), creating an altered firing pattern.

The most common firing pattern dysfunction is synergistic dominance, in which a synergist compensates for a prime mover to produce the movement. For example, if a client has a weak gluteus medius, then synergists (the tensor fascia lata, adductor complex, and quadratus lumborum) become dominant to compensate for the weakness. This alters normal joint alignment, which further alters the normal length-tension relationships of the muscles around the joint. See Box 10-4 for the most commonly used assessment procedures and interventions for altered firing patterns.

Each jointed area has a movement muscle activation sequence. The movement is a product of the entire mechanism, including the following:

• Bones, joints, and ligaments

• Capsular components and design

• Tendons, muscle shapes, and fiber types

• Interlinked fascial networks, nerve distribution, and myotatic units of prime movers

• Antagonists, synergists, and fixators

• Neurologic kinetic chain interactions

• Body-wide influence of reflexes, including positional and righting reflexes of vision and the inner ear and gait reflex

Assessment of a movement pattern as normal indicates that all parts are functioning in a well-orchestrated manner. When a dysfunction is identified, causal factors can arise from any one or a combination of these elements. Often a multidisciplinary diagnosis is necessary to identify clearly the interconnected nature of the pathologic condition.

Inappropriate firing patterns can be addressed by inhibiting the muscles that are contracting out of sequence and stimulating the appropriate muscles to fire. Compression to the muscle belly effectively inhibits a muscle. Tapotement is a good technique for stimulating muscles. If the problem does not normalize easily, referral to an exercise professional may be indicated.

Gait Assessment

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-4: Gait Assessment.

Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-4: Gait Assessment.

Understanding the basic body movements of walking helps the massage therapist recognize dysfunctional and inefficient gait patterns.

Disruption of gait reflexes creates the potential for many problems. Common gait problems include a functional short leg caused by muscle shortening, tight neck and shoulder muscles, aching feet, and fatigue. The massage therapist must understand biomechanics, including posture, interaction of joint functions, and gait, and must expand that knowledge to the demands of sport performance.

This is especially important in rehabilitation progress in which walking is the goal or part of the program. It is important to observe the client from front, back, and both sides. To begin, the massage practitioner should watch the client walk, noticing the heel-to-toe foot placement. The toes should point directly forward with each step.

Observe the upper body. It should be relaxed and fairly symmetric. The head should face forward with the eyes level with the horizontal plane. There is a natural arm swing that is opposite to the leg swing. The arm swing begins at the shoulder joint. On each step, the left arm moves forward as the right leg moves forward and then vice versa. This pattern provides balance. The rhythm and pace of the arm and leg swing should be similar. Increased walking speed increases the speed of the arm swing. The length of the stride determines the arc of the arm swing.

Observe the client walking, and note his or her general appearance. The optimal walking pattern is as follows:

1. Head and trunk are vertical, with the eyes easily maintaining forward position and level with the horizontal plane; shoulders are level.

2. Arms swing freely opposite the leg swing, allowing the shoulder girdle to rotate opposite the pelvic girdle.

3. Step length and step timing are even.

4. The body oscillates vertically with each step.

5. The entire body moves rhythmically with each step.

6. At the heel strike, the foot is approximately at a right angle to the leg.

7. The knee is extended but not locked.

8. The body weight is shifted forward into the stance phase.

9. At push-off, the foot is strongly plantar-flexed, with defined hyperextension of the metatarsophalangeal joints of the toes.

10. During the leg swing, the foot easily clears the floor with good alignment, and the rhythm of movement remains unchanged.

11. The heel contacts the floor first.

12. The weight then rolls to the outside of the arch.

13. The arch flattens slightly in response to the weight load.

14. The weight then is shifted to the ball of the foot in preparation for the spring-off from the toes and shifting of weight to the other foot.

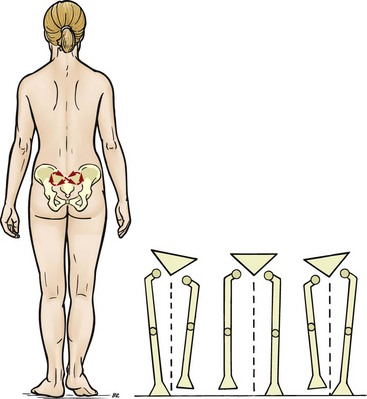

During walking, the pelvis moves slightly in a side-lying figure-eight pattern. Movements that make up this sequence are transverse, medial, and lateral rotation. The stability and mobility of the sacroiliac joints play very important roles in this alternating side figure-eight movement. If these joints are not functioning properly, the entire gait is disrupted. The sacroiliac joint is one of the few joints in the body that is not directly affected by muscles that cross the joint. It is a large joint, and bony contact between sacrum and ilium is broad. It is common for the rocking of this joint to be disrupted (Figure 10-11).

FIGURE 10-11 The mechanism of the slight rocking movement of the sacroiliac joint. (From Fritz S: Mosby’s fundamentals of therapeutic massage, ed 5, St Louis, 2013, Mosby.)

The hips rotate in a slightly oval pattern, beginning with a medial rotation during the leg swing and heel strike, followed by a lateral rotation through the push-off. The knees move in a flexion and extension pattern opposite each other. The extension phase never reaches enough extension to initiate the normal knee lock pattern that is used in standing. The ankles rotate in an arc around the heel at heel strike and around a center in the forefoot at push-off. Maximal dorsiflexion at the end of the stance phase and maximal plantar flexion at the end of push-off are necessary.

When assessing gait, observing for areas of the body that do not move efficiently during walking is a good means of detecting dysfunctional areas. Pain causes the body to tighten and alters the normal relaxed flow of walking. Muscle weakness and shortening interfere with neurologic control of agonist (prime mover) and antagonist muscle action. Hypomobility (limitation of joint movement) and hypermobility (laxity) result in protective muscle contraction.

If the situation becomes chronic, both muscle shortening and muscle weakness result. Changes in the soft tissue, including all connective tissue elements of the tendons, ligaments, and fascial sheaths, restrict the normal action of muscles. Connective tissue usually shortens and becomes less pliable.

Amputation disrupts the body’s normal diagonal balance. Obviously, any amputation of the lower limb disturbs the walking pattern. What is not so obvious is that amputation of any part of the upper limb affects the counterbalance movement of the arm swing during walking. The rest of the body must compensate for the loss. Loss of any of the toes greatly affects the postural information sent to the brain from the feet.

It is possible to have soft tissue dysfunction without joint involvement. Any change in the tissue around a joint has a direct effect on joint function. Changes in joint function eventually cause problems with the joint. Any dysfunction of the joint immediately involves the surrounding muscles and other soft tissue.

Disruption of gait demands that the body compensate by shifting movement patterns and posture. Because of this, all dysfunctional patterns are whole body phenomena. Working only on the symptomatic area is ineffective and offers only limited relief. Therapeutic massage with a whole body focus is extremely valuable in dealing with gait dysfunction. Corrective measures include normalizing muscle firing patterns and gait reflex patterns (see Box 10-4).

![]() The Evolve website provides step-by-step visual instructions for performing gait testing assessments, findings, and intervention suggestions.

The Evolve website provides step-by-step visual instructions for performing gait testing assessments, findings, and intervention suggestions.

Interpreting Gait Assessment Findings

When interpreting the information gathered from gait assessment, the massage practitioner should focus on areas that do not move easily when the client walks and areas that move too much. Areas that do not move are restricted; areas that move too much are compensating for inefficient function. By releasing the restrictions through massage and reeducating the reflexes through neuromuscular work and exercise, the practitioner can help the client improve the gait pattern.

The techniques followed are similar to those for postural corrections. The shortened and restricted areas are softened with massage, and then the neuromuscular mechanism is reset with muscle energy techniques, muscle lengthening, stretching, and normalizing of firing patterns.

The client should be taught slow lengthening and stretching procedures. After stimulating the muscles in weakened areas, the practitioner can refer the client for strengthening exercises. The therapist must be sure that the adaptation methods are built into the context of a complete massage rather than spot work on isolated parts of the body. Suggestions can be made to the client to evaluate factors that may contribute to these adaptations, such as posture, footwear, chairs, tables, beds, clothing, workstations, physical tasks (e.g., shoveling), and repetitive exercise patterns.

Sacroiliac Joint Function

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-5: Correction Methods for Gait Assessment and/or Muscle Firing Patterns.

Log on to your Evolve website to watch Video 10-5: Correction Methods for Gait Assessment and/or Muscle Firing Patterns.

Proper functioning of the sacroiliac (SI) joint is an important factor in walking patterns. Because sacroiliac joint movement has no direct muscular component, it is difficult to use any kind of muscle energy lengthening when working with this joint. The SI joint is embedded deep in supporting ligaments. To keep surrounding ligaments pliable, direct and specific, connective tissue techniques are indicated unless the joint is hypermobile. If that is the case, external bracing combined with rehabilitative movement may be indicated. Sometimes the ligaments restabilize the area. Stabilization of the jointed area should be interspersed with massage and gentle stretching to ensure that the ligaments remain pliable and do not adhere to each other. This process takes time.

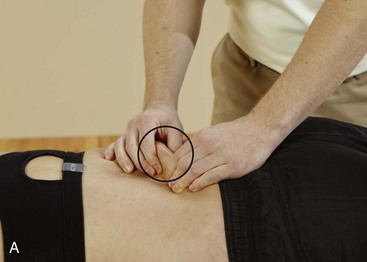

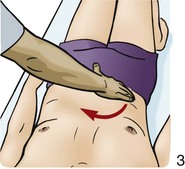

To assess for possible SI joint involvement, apply deep broad-based compression over the joint (Figure 10-12). If symptoms increase, SI joint dysfunction is indicated. Another assessment is to have the client stand on one foot and then extend the trunk. This loads the SI joint and would increase symptoms of SI joint dysfunction. Have the client lie prone and extend the hip. Then apply resistance to the opposite arm and have the client push against the resistance by extending the shoulder and arm (Figure 10-13), and then, while doing this, also extend the contralateral hip. If it is easier to lift and symptoms are relieved, SI joint function can be improved by exercise and massage, because force closure mechanisms are able to be addressed. If no improvement is noted, external bracing may help.

The diagnosis of specific joint problems and fitting for external bracing are outside the scope of practice for therapeutic massage, and the client must be referred to the appropriate professional.

Analysis of Muscle Testing and Gait Patterns